Chapter 6 Nursing assessment and diagnosis

Mastery of content will enable you to:

• Discuss the purpose of nursing assessment.

• Explain the relationships among data collection, data analysis and critical thinking.

• Explain the difference between a comprehensive and a problem-oriented health assessment.

• Explain why client expectations are important to include in assessment.

• Differentiate between subjective and objective data.

• Identify different sources and methods of data collection for a nursing assessment.

• State the purpose of a health history and physical examination.

• Perform and document a nursing health assessment.

• Understand the process of data analysis to identify client strengths and health problems.

A critical thinking approach to assessment

Professional practice standards require the nurse to solve problems accurately, thoroughly and quickly. The nurse reviews information from a variety of sources to make critical judgments. During a nursing assessment, the nurse systematically collects, verifies, analyses and communicates data about a client. This is done to gather the information needed to make an accurate clinical judgment about the client’s current status in order to plan care. This phase of the nursing process has two steps:

1. collection and verification of information from a primary source (the client) and secondary sources (family, healthcare professionals)

2. the clustering and analysis of that information to determine the client’s strengths and health problems (Magnan and Maklebust, 2009).

The purpose of the assessment is to establish a database about the client’s perceived needs, health problems and responses to these problems, related experiences, health practices, goals, values, lifestyle and expectations of the healthcare system. The information contained in the database is the foundation for formulating nursing diagnoses or diagnostic statements which enable the nurse to plan individualised care. This plan can be evaluated and adjusted throughout the time the nurse cares for the client.

Knowledge from the physical, biological and social sciences enables the nurse to ask relevant questions and collect accurate and relevant physical assessment data related to the client’s expectation of care or underlying healthcare needs. As a student nurse, validation of abnormal assessment findings and observation of assessments by skilled professionals will enable you to gain competency in the assessment process.

What is most important is for you to learn to think critically about what to assess (Gordon, 2007). When a nurse first encounters a client, there is a chance for a quick overview. This overview is usually based on the nurse’s specialty or the practice context. For example, an emergency department nurse may use the ABCDE (airway, breathing, circulation, disability, exposure) approach, whereas a mental health nurse may conduct a focused mental status examination. It is possible that other important cues may be missed during this initial assessment. However, the nurse notices and interprets cues from the client to know how in-depth an assessment should be (Tanner, 2006). Assessment should allow the nurse to freely explore relevant problems as they appear.

The initial overview of the client’s situation allows the nurse to use key assessment data to respond to priorities, such as difficulty with breathing or the onset of pain. It is important for the nurse to recognise that the client’s situation can change at any time during assessment and that data collection must be accurate, relevant and appropriate for the client’s situation.

Gordon (2007) describes two approaches to collecting comprehensive data. One is a structured comprehensive database format (see Box 6-1), and the other is a problem-oriented approach focusing on the client’s presenting situation.

BOX 6-1 TYPOLOGY OF 11 FUNCTIONAL HEALTH PATTERNS

Health perception–health management pattern

Self-perception–self-concept pattern

Sexuality–reproductive pattern

Data from Gordon M 2007 Manual of nursing diagnosis, ed 11. St Louis, Mosby.

The comprehensive approach moves from general to specific. Data are collected in all 11 functional health patterns and then reviewed to see if patterns of problems are revealed. For each of the 11 patterns, the nurse assesses clients by organising patterns of behaviour and physiological responses that pertain to a functional health category. The nurse then compares assessment data with the client’s baseline (e.g. usual blood pressure, weight and nutritional intake) and established norms based on age, gender, cultural, social or other norms, such as religious practices, ethnic dietary guidelines and healthcare practices. The assessment of each of the 11 patterns represents the interaction of the client and the environment, which Gordon calls biopsychosocial integration. No one health pattern can be understood without knowledge of the other patterns. Description and evaluation of health patterns help the nurse identify functional patterns (client strengths) and dysfunctional patterns (nursing diagnoses), which help develop the nursing care plan.

The second method of assessment is the problem-focused approach. The assessment begins with problematic areas (such as shortness of breath) and broadens to relevant areas of the client’s life. For example, assessment might begin with a focused respiratory assessment and then broaden to categories such as how this health problem influences the client’s lifestyle, family relationships and work habits. Once that is completed, the presenting problem of shortness of breath will be thoroughly analysed so that a comprehensive approach can be used to plan interventions directed towards relief.

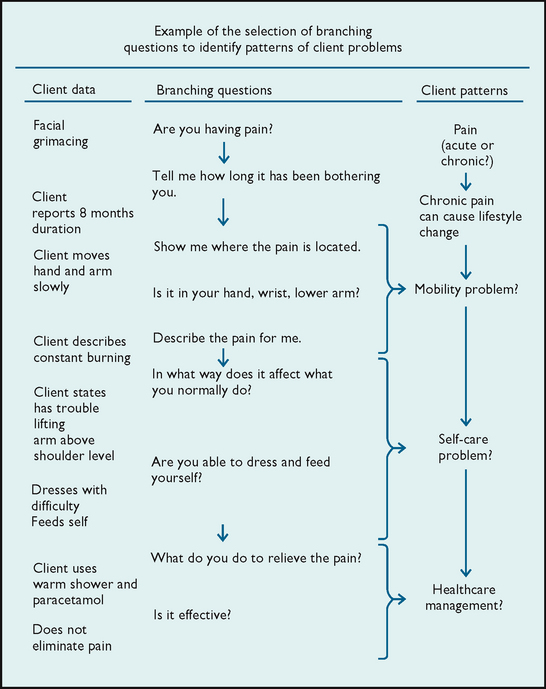

Whatever approach is used, the nurse identifies emerging patterns and potential problems. To do this well, a nurse anticipates; that is, tries to stay a step ahead of the assessment. The nurse’s clinical problem solving is sometimes stepped, sometimes branching, when data from new problems are recognised, and always cyclical, when the nurse must reassess and validate information (see Figure 6-1).

Once a question has been asked of a client or an observation has been made, the information often branches to an additional series of questions or observations. Knowing how to frame questions is a skill refined over time. For example, simply asking a client if they have pain may elicit a yes or no answer, but not enough information to effectively plan interventions. If the nurse framed the question differently, for example ‘How would you describe the pain in your chest?’, the client may give a fuller description of the onset, severity and type of pain experienced. These examples describe the difference between open-ended and closed-ended questions. The nurse decides which questions are relevant to the situation while at the same time making sure the assessment is complete. The nurse’s thoughts about the client proceed from something given, a cue or data, to a conclusion. It is important to remember that the extent of a nurse’s ability to grasp the meaning of the data being collected and analysed is based on the nurse’s knowledge and experience.

Organisation of data gathering

As a nurse conducts an assessment, there are considerable interactions (verbal and non-verbal) between the nurse and the client. In addition, the client presents physiological responses (such as work of breathing) that immediately relay information to the nurse. The nurse uses all senses to accurately assess client behaviour. For example, when a nurse observes a client with shortness of breath, sense impressions are formed that the client is in trouble. These sense impressions are sources of knowledge and are often reliable cues that lead the nurse to a more deliberate assessment. The skills of physical examination enable the nurse to explore physical findings accurately and in detail, such as respiratory rate and lung sounds. When making clinical judgments, the nurse connects sense experiences to nursing knowledge to ensure accurate reasoning.

Data collection

The nurse collects data that are descriptive, concise and complete. Assessment does not include inferences or interpretative statements that are unsupported by data. Descriptive data originate in the client’s perception of a symptom, the perceptions and observations of the family, the nurse’s observations, or reports from other members of the healthcare team. It is important to encourage clients to tell their story about their healthcare problem/s. For example, a client may describe pain as a ‘sharp, throbbing pain in the abdomen’. The nurse’s observation may be ‘the client lies on the right side holding the abdomen; facial grimacing present’. The nurse conducts a focused examination and records only observations, avoiding interpreting behaviour (e.g. ‘the client tolerates pain poorly’).

The information is summarised using appropriate clinical language and terminology (see Chapter 14; e.g. ‘Client describes a “constant, sharp, throbbing pain” in the right upper quadrant of the abdomen. Pain began 48 hours before hospitalisation, 2 hours after a high-fat meal. Not relieved by antacids.’). Complete data collection results from obtaining all information relevant to the actual or potential health problem.

The collection of inaccurate, incomplete or inappropriate data may lead to incorrect identification of the client’s healthcare needs, and subsequent inaccurate, incomplete or inappropriate nursing diagnoses. Inaccurate data result if the nurse fails to collect information relevant to a specific area or if the nurse is disorganised or unskilled in assessment techniques. Data may be incomplete if the nurse jumps to conclusions about a potential problem, stops asking questions prematurely or makes assumptions without validation.

Types of data

During assessment, the nurse obtains two types of data: subjective and objective.

Subjective data are clients’ perceptions about their health problems. Only clients can provide information about a symptom’s frequency, duration, location and intensity. Subjective data may include feelings of anxiety, physical discomfort or mental stress. Although only clients can provide subjective data relevant to these feelings, the nurse remains aware that these problems can result in physiological and behavioural changes, which are identified through objective data collection.

Objective data are observations or measurements made by the nurse. Assessment of a client’s wound and identification of the size of a localised body rash are examples of observed objective data. The measurement of objective data is based on an accepted standard, such as the Celsius measure on a thermometer or centimetres on a measuring tape. Bodyweight and height are examples of measured objective data.

Sources of data

Subjective data are obtained from the client, family, significant others, healthcare team members and health records. Objective data are obtained through physical examination, results of diagnostic and laboratory tests and pertinent nursing and health literature. The nurse’s own past experience with similar types of clients is an additional source of data. Each source provides information about the client’s level of wellness, anticipated prognosis, risk factors, health practices and goals and patterns of health and illness, as well as information relevant to the client’s healthcare needs. The client who is oriented and answers questions appropriately can provide the most accurate information about his or her healthcare needs, lifestyle patterns, present and past illnesses, perception of symptoms and changes in activities of daily living.

Family and significant others

Families and significant others can be interviewed as primary sources of information about infants or children and critically ill, cognitively impaired, disoriented or unconscious clients. In emergency situations, paramedics, police officers and other emergency workers may be the primary source of information about the nature of a client’s problem. In severe illness, families may be the only available sources of data about a client’s health–illness patterns, current medications, allergies, onset of illness and other vital information.

The family and significant others are also important secondary sources of information. Often partners or close friends will sit in during an assessment and provide their view of the client’s health problems or needs. Not only can they supply information about the client’s current health status, but also they may be able to indicate when changes in the client’s status occurred and how the client’s functioning was affected. For example, the partner of an elderly woman with symptoms of memory loss may be able to recall the onset of the symptom and any related factors.

Healthcare team members

The healthcare team consists of nursing, medical, allied health professionals and other employees working in a healthcare setting. Because assessment is an ongoing process, the nurse must communicate with other healthcare team members whenever possible to gather information about the way the client interacts within the healthcare environment, the client’s reaction to information about diagnostic tests and, in acute and restorative care settings, how the client responds to visitors. Clients will frequently discuss their feelings and perceptions with other staff on the unit who can be a valuable source of feedback to the nurse.

Healthcare records

The present and past healthcare records of the client can verify information about past health patterns and treatments or can provide new information. By reviewing these records, the nurse can identify patterns of illness, previous responses to treatment and past methods of coping.

Other records such as educational, military and employment records may contain pertinent healthcare information (e.g. immunisations, previous illnesses). Any information obtained is confidential and is treated as part of the client’s legal healthcare record. Magnan and Maklebust (2009) acknowledge that assessment serves a single purpose—that is, to plan effective care. A nurse’s expertise develops after testing and refining propositions, questions and principle-based expectations. For example, after a nurse has cared for a client with abdominal pain, the nurse will recognise more quickly the behaviour the client showed while in acute pain. The nurse will have noted the extent to which positioning techniques helped the client to relax and have less discomfort; the principle of administering a pain medication regularly rather than when the client requests it, to achieve better pain control, will have been tested. Reviewing professional literature may also help the nurse to complete the database. A review increases the nurse’s currency of knowledge about the symptoms and related aetiology. The nurse may also seek validation of their findings by an expert colleague such as a nurse practitioner. For example, a client who is being cared for in an orthopaedic unit following the application of traction for lower leg trauma may also present a history of type 1 diabetes, which requires careful management due to a change in diet and immobilisation. The expertise of a diabetes nurse educator may assist the nurse to plan care for the client’s hospital stay as well as prepare the client for eventual discharge home.

Methods of data collection

The nurse uses the client interview, the nursing health history, physical examination and results of laboratory and diagnostic tests to establish the database. Each method allows the nurse to collect complete information about the client’s past and present level of wellness.

Interview

The interview is a pattern of communication initiated for a specific purpose and focused on a specific content area. In nursing, the major purposes of the interview are to obtain from the client a health history, identify health needs and risk factors and determine specific changes in level of wellness and pattern of living. Most importantly, the interview should help clients relate their own interpretation and understanding of their condition. This means the nurse and client must be partners during the interview rather than the nurse controlling the interview. Unless an interview allows a client to express needs, the interaction may be unsuccessful.

An interview may be focused, as in the case of a client admitted to the emergency department, or it can be comprehensive, as in the case of a new client for whom a complete health history is required. The interviewer obtains information about the client’s health, lifestyle, support systems, patterns of illness, patterns of adaptation, strengths and limitations, and resources. As the nurse listens to and considers the information given, the client may be directed to give more detail or discuss a topic that seems to reveal a possible problem. Since the client’s report will include subjective information, the nurse later uses objective methods to validate data from the interview. For example, if the client reports difficulty in walking, the nurse will later assess the client’s gait and muscle strength.

When conducting the interview, the nurse uses specific communication skills to focus attention on the client’s level of wellness. The nurse also helps the client understand the change that is occurring or will occur once healthcare begins. This chapter briefly describes communication skills and the interview, whereas Chapter 12 discusses communication for nursing practice in more depth.

First, the nurse–client relationship is initiated. A nurse–client relationship is the association between the nurse and the client that has a mutual concern—the client’s wellbeing. This relationship encourages the sharing of information, ideas and emotions, and enables the nurse to express a level of caring for the client. The clinical example below shows how the nurse establishes a beginning rapport with a newly admitted client.

The RN is preparing an admission history on Mr Brown, a 60-year-old man hospitalised for the first time.

Nurse: Good afternoon, Mr Brown. I’m Wendy Thomas, and I’m the registered nurse who will be managing your care during your hospital stay and through discharge to your home.

Mr Brown: Hello, Wendy. Please call me Bill. What do you mean by managing my care?

Nurse: That means I’m responsible for coordinating your nursing care with the rest of the nurses while you’re hospitalised. I will work with them to plan for your discharge back to your home. Although other nurses will sometimes take care of you when I’m off, I’m the nurse who plans your care. Once you’re discharged, I’ll call you at home to see how you are doing and if you have any questions.

Mr Brown: I guess that’s a lot like being a coach. You may not play the game, but you’re responsible for winning or losing.

Nurse: I suppose that’s one way of looking at it. To better plan your care I will be asking some questions about your health. We call this a health interview. Any information you give me is confidential. The total interview should take about 20 to 30 minutes. Is it okay if I begin the interview in a few minutes?

Mr Brown: Can you give me half an hour? My wife is about to leave. She needs to pick up the grandchildren at day care. That way we can have some time together. I’ll be ready after that.

Nurse: That’s fine. Since you’re in a private room, I will do the health interview here. (Mr Brown nods.)

Thirty minutes later, Wendy returns to the room.

Nurse: Okay. Before I get started, do you have any questions for me?

Mr Brown: Yes. Why is there an outlet for oxygen on the wall above my bed? Does that mean that I’m really sick—did they put me in a special room?

Nurse: No, that’s not it. Every bed in this hospital has an oxygen outlet located on the wall above the head of the bed. The reason is that this hospital has a central oxygen delivery system, and when a patient needs oxygen, we’re able to supply it quickly, easily and safely.

Mr Brown: Okay. I wasn’t actually worried. I was basically just curious. That was the only piece of equipment I couldn’t explain.

Nurse: (pause) Bill, you mentioned that you and your wife have grandchildren in day care. Tell me a bit about your family.

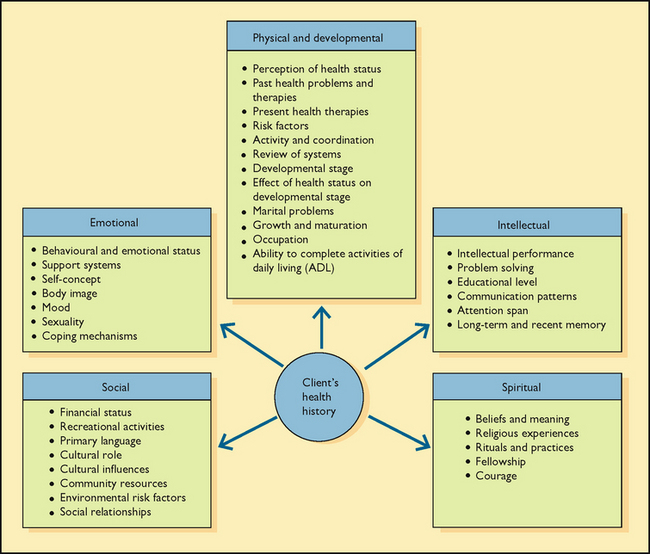

During the interview the nurse obtains information about a client’s physical, developmental and psychosocial dimensions. Physical and developmental information reflects normal functioning and the pathological changes in a person’s pattern of living induced by illness, trauma or developmental crisis. Emotional information includes the behavioural responses to changes in health and pattern of living. Relevant emotional information includes mood, perceptions, body image, self-concept and attitudes about sexuality. Intellectual information includes intellectual performance, problem-solving ability, educational level, communication patterns and attention span. Social information involves environmental, cultural, ethnic or social patterns that can affect the present or future level of wellness. The nurse also collects information about values, beliefs and religious practices, which are part of the spiritual dimension.

The interview also provides the nurse with the opportunity to observe the client. The nurse observes interactions between the client and family and between the client and the healthcare environment, such as eye contact, non-verbal communication and other body language. While observing this behaviour, appearance and interaction with the environment, the nurse determines whether the data obtained by observation are consistent with those obtained by verbal communication. For example, if the client does not disclose concern about an upcoming diagnostic test but appears anxious and irritable, the data are in conflict. Observations during an interview lead the nurse to gather additional objective information to form accurate conclusions.

The interview is a mechanism by which the client can obtain information as well. If a positive nurse–client relationship has been established, the client will feel comfortable asking the nurse questions about the healthcare environment, treatments, diagnostic testing and available resources. The client needs this information to participate in decision making regarding goals and the plan of care. It is important for the nurse to ask clients about their expectations of healthcare providers. In addition, the interview is a first step towards establishing a therapeutic relationship between the nurse and client so that health interventions such as education or counselling can occur.

Nursing health history

The nursing health history is data collected at interview about the client’s level of wellness (present and past), family history, changes in life patterns, sociocultural history and psychosocial responses to illness. The objective is to identify patterns of health and illness, risk factors for physical and behavioural health problems, deviations from normal, and available resources for adaptation. Although many health history forms are structured, the nurse learns to use the questions as starting points.

Biographical information

Biographical information is factual demographic data about the client. The client’s age, address, occupation and working status, and marital status should be included.

Reason for seeking healthcare

The nurse asks why the client sought healthcare, because the information contained on the initial admission form may differ greatly from the client’s subjective reason. Clarification of the client’s perception identifies potential areas for education, counselling or community resources required throughout all phases of diagnosis and recovery. When recorded, the statement is enclosed in quotation marks to indicate that these words came directly from the client.

Client expectations

The assessment of client expectations is not the same as the reason for seeking healthcare, although they are often related. It is becoming more important for nurses to acknowledge what is important to the client who is seeking healthcare. Failure to identify a client’s expectations of healthcare providers and a healthcare institution can result in poor client satisfaction. Client satisfaction is becoming a standard measure of quality for almost every major healthcare institution throughout the country.

Clients typically have expectations in the following areas:

• information needed to care for their health problems independently

• caring and compassion expressed by care providers

The initial interview can establish the client’s expectations when entering the healthcare setting. The nurse determines whether clients expect to be ‘cured’, ‘free of pain’ or ‘able to care for themselves’. This information helps establish the goals of nursing care, as well as determines whether clients’ expectations of themselves and the healthcare providers are realistic. In addition, such expectations provide information on client perceptions about patterns of illness or changes in lifestyle.

Present illness

If an illness is present, nurses gather essential and relevant data about the onset of symptoms: when the symptoms began, whether they began suddenly or gradually, and whether they are always present or come and go. The nurse asks about the duration of symptoms. In the section on the history of present illness, the nurse records specific information such as location, intensity and quality of a symptom. The development and use of a symptom assessment mnemonic such as PQRST is cited in the literature (Lacasse and Beck, 2007; Scott and MacInnes, 2006) as a useful tool to assist the nurse to evaluate each symptom by describing provoking or palliating factors (P), quality or quantity (Q), severity or intensity of the system (S), region (R) and timing (T) (see Box 6-2). Examples of in-depth symptom assessment for symptoms can be found in the clinical chapters of this text.

BOX 6-2 PQRST MNEMONIC FOR SYMPTOM ANALYSIS

| FACTORS | THE CLIENT IS ASKED TO DESCRIBE |

|---|---|

| P— Provoking or palliative | What brings on the symptom; what makes it worse or better? |

| Q— Quality or quantity | How does the symptom feel, look sound or smell like? |

| R— Region and radiation | Where does the symptom occur; does it spread to other areas? |

| S—Severity | |

| T—Timing |

Past health history

The information collected about past history provides data on the client’s healthcare experiences and includes many dimensions (Figure 6-3). The nurse assesses whether the client has experienced a serious illness, been hospitalised or undergone surgery. Also essential in planning nursing care are descriptions of allergies, including allergic reactions to food, latex, drugs or pollutants. If an allergy is present, the specific reaction and treatment are noted on the assessment form.

The nurse also identifies habits and lifestyle patterns. Use of alcohol, tobacco, caffeine, over-the-counter drugs, illicit drugs or routinely taken medications can place the client at risk of diseases involving the liver, lungs, heart, nervous system or thought processes. Noting the type of dependence, as well as the frequency and duration of use, provides essential data.

Assessing patterns of sleep, exercise and nutrition is important when planning nursing care. The plan of care within a healthcare setting should match a client’s lifestyle patterns as much as possible. Often, variations in sleep, activity and nutritional patterns can be accommodated.

Family history

The purpose of the family history is to obtain data about immediate and blood relatives. The objectives are to determine whether the client is at risk of illnesses of a genetic or familial nature and to identify areas of health promotion and illness prevention. The family history also provides information about family structure, interaction and function that may be useful in planning care. For example, a cohesive, supportive family can be a resource in helping a client adjust to an illness or disability and should be incorporated into the plan of care. If the client’s family is not supportive, it may be better not to involve them in care.

Environmental history

The environmental history provides data about the client’s home environments and any support systems that they or family members might need. Information pertaining to the home environment may include function of utilities, layout of rooms in the house and the presence of any barriers or risks to client safety. In addition, the environmental history identifies exposure to pollutants that can affect health, existence of high crime that prevents clients from walking around their neighbourhoods and available resources that can help clients return to the community.

Psychosocial history

A complete psychosocial history will reveal the client’s support system, which may include spouse/partner, children, other family members and close friends. The psychosocial history includes information about ways the client and family typically cope with stress (see Chapter 42). The same behaviour, such as taking a walk, reading or talking with a friend, can be used as a nursing intervention if the client experiences stress while receiving healthcare. The nurse also learns whether the client has experienced any recent losses that create a sense of grief.

Review of systems

The review of systems (ROS) is a systematic method for collecting data on all body systems (Jarvis, 2007). The systems that are assessed depend on the client’s condition and the urgency in initiating care. During the ROS, the nurse asks the client about the normal functioning of each system and any noted changes. Such changes are usually subjective data because they are described as perceived by the client.

Physical examination

The physical examination and collection of diagnostic and laboratory data involve the gathering of objective, observable information (see Chapter 27). The physical examination is the taking of vital signs and other measurements and the examination of all body parts using the techniques of inspection, palpation, percussion, auscultation and olfaction. The nurse looks for abnormalities that may yield information about past, present and future health problems. The physical examination is conducted after the nursing health history so that historical data can be verified. In addition, new data (e.g. appearance of the client’s skin and muscle strength) are obtained during the examination.

Throughout the examination, data are measured against a standard, which is an established rule or basis of comparison in measuring or judging capacity, quantity, content and value of objects in the same category. Selected standards are reliable and relevant for the category being compared. For example, the nurse will know the established standards for ideal height and weight that are used to determine whether an individual is overweight or underweight; there are standards for blood pressure ranges for clients of particular age groups. The nurse conducts the physical examination to verify information and collect further data, which are compared with the standards to determine whether the findings are normal or abnormal.

Diagnostic and laboratory data

The final source of assessment data is the results of diagnostic and laboratory tests. The tests are ordered by medical or nurse practitioners. It is important for the nurse to review the results to verify alterations identified in the nursing health history and physical examination. Laboratory data are compared with the established norms for a particular test, age group and sex. In addition, laboratory data can be used to evaluate the success or failure of nursing and medical interventions. Specific laboratory tests and the nursing responsibilities associated with them are detailed in Parts 6 and 7 of the text.