Chapter 5 Critical thinking and nursing judgment

LEARNING OUTCOMES

Mastery of content will enable you to:

• Discuss the nurse’s responsibility in making clinical decisions.

• Describe the components of a critical thinking model for clinical decision making.

• Discuss critical thinking skills used in nursing practice.

• Explain the relationship between clinical experience and critical thinking.

• Discuss the influence of critical thinking attitudes on clinical decision making.

• Discuss how reflection in action and reflection on action can improve nursing practice.

• Explain how professional standards influence a nurse’s clinical decisions.

• Discuss the relationship between ethical nursing practice and critical thinking.

• Discuss the relationship of critical thinking to the nursing process.

Introduction

Although the responsibility of making clinical decisions may seem frightening to a new student, it is a major aspect of nursing that makes it a rewarding and challenging profession. Nurses in clinical practice face an endless variety of situations involving clients, family members, healthcare staff and peers. Each situation poses new experiences with new challenges involving client care, different approaches to resolving problems, and different perspectives on the best way to proceed. In clinical situations, it is important for the nurse to think critically so that the client ultimately receives the very best nursing care. Critical thinking is not a simple step-by-step linear process that can be learned overnight and applied to address repeated problems. It is a cyclical process that can be acquired only through practice, commitment and a desire to learn. It is a skill that students have begun to develop in early life at home and at school. Now, as nursing students, many of the principles can be applied in your classroom and laboratory learning, using case studies and role-playing, through simulation of client situations and in real clinical settings. Confidence in your ability to make clinical judgments and decisions using critical thinking and logical thought processes is founded on the gradual build-up of professional knowledge and experience about your practice, through reflection and careful communication of each decision made (Castledine, 2010).

This unit introduces the reader to the nursing process which provides a systematic framework for the use of logical thought processes or critical thinking to collect, analyse and synthesise client data crucial to clinical decision making in the best interests of the client.

Critical thinking defined

Although critical thinking has many definitions, Riddell (2007) argues that the process of critical thinking requires an explanation rather than a definition. She highlights common factors identified in the literature on critical thinking processes, all of which result in a change in belief or course of action:

• reflection

• identification and appraisal of assumptions

• inquiry, interpretation and analysis, and reasoning and judgment

• consideration of context.

A critical thinker identifies and challenges assumptions, considers what is important in a situation, imagines and explores alternatives, applies reason and logic, and thus makes informed decisions (Alfaro-LeFevre, 2010).

For a nursing student, critical thinking begins when the student seriously questions and tries to answer, again and again: ‘What do I really know about this nursing care situation, how do I know it, and what else do I need to know?’ Critical thinking presupposes a certain basic level of intellectual humility (i.e. acknowledging one’s own ignorance), an understanding of one’s values and possible biases, and a commitment to think clearly, precisely and accurately and to act on the basis of a well-argued position. When the nurse directs critical thinking towards understanding and helping clients to find solutions to their health problems, the process is purposeful and goal oriented.

Today’s nursing environment is continually changing. Healthcare in the 21st century is more complex and demanding due to more emphasis on patient information, patients’ rights and best evidence for practice. It is important that the nurse participates in shared decision making with other professional colleagues. Working together involves asking questions and challenging differing perspectives (Castledine, 2010). Through critical thinking, a person confronts problems, considers choices and chooses an appropriate course of action. It is clear that critical thinking requires not only cognitive skills but also an ability to ask questions, to remain well informed, to be honest in facing personal biases and always to be willing to reconsider and think clearly about issues. The American Philosophical Association (APA) has identified core critical thinking skills (Table 5-1). Box 5-1 shows examples of how these could be applied to nursing, and demonstrates the complex nature of clinical decision making.

TABLE 5-1 CRITICAL THINKING SKILLS PROPOSED BY THE AMERICAN PHILOSOPHICAL ASSOCIATION

| SKILL |

SUB-SKILL |

| Interpretation |

Categorisation

Decoding sentences

Clarifying meaning

|

| Analysis |

Examining ideas

Identifying arguments

Analysing arguments

|

| Evaluation |

Assessing claims

Assessing arguments

|

| Inference |

Examining evidence

Speculating or conjecturing alternatives

Making conclusions

|

| Explanation |

Stating results

Justifying procedures

Presenting arguments

|

| Self-regulation |

Self-examination

Self-correction

|

From Facione PA (project director) 1990 Executive summary of critical thinking: a statement of expert consensus for purposes of educational assessment and instruction (the APA Delphi report). Newark, DE, American Philosophical Association. ERIC Doc No. ED 315–423, Table 3, p. 6.

BOX 5-1 EXAMPLES OF CRITICAL THINKING SKILLS REQUIRED IN NURSING

INTERPRETATION

• Be systematic in data collection.

• Look for patterns to categorise data.

• Clarify any data you are uncertain about.

• Recognise any biases you may have.

ANALYSIS

• Be open-minded as you look at information about a client.

• Do not make careless assumptions. Do the data reveal what you believe is true, or are there other options?

EVALUATION

• Look at all situations from an objective view to determine results of any actions or interactions. Reflect on your own feelings and behaviour.

• Look at the meaning and significance of findings. Are there relationships between findings? Do the data about the client help you see that a problem may exist?

INFERENCE

• Support your findings and conclusions.

• Justify the strategies you use in the care of clients.

SELF-REGULATION

• Reflect on your experiences.

• Identify how you can improve your own performance. What will make you feel that you have been successful?

Reflection

Reflection can be defined as the careful consideration and examination of issues of concern related to an experience to discover the meaning and purpose of that experience (Kuiper and Pesut, 2004). The process of reflection helps the nurse to seek and understand the relationships between concepts learned in the classroom and clinical practice. Reflection in action is the nurse’s ability to ‘read’ the patient, to notice and recognise, to measure progress and to make changes to care. For the expert nurse this is often tacit knowledge based on experience. Reflection on action, the careful, systematic and analytical review of nursing action and subsequent learning, contributes to ongoing clinical development and application to future situations (Tanner, 2006).

Using a reflective process can also help you judge personal performance and make judgments about standards of practice (Freegard, 2007). It is a process that helps make sense out of an experience and facilitates the incorporation of the experience into one’s view of self as a professional.

Becoming a critically reflective practitioner takes practice. Nurses who reflect on a clinical experience in discussion with colleagues need to be open to new information and to be able to consider multiple perspectives and potential explanations. One common approach to reflection is keeping a journal or diary of clinical experiences and interactions with colleagues. Writing a journal can help you develop the habit of critical reflection, and becomes a rich resource for you to review important experiences and gain insight into the thoughts and actions that make up clinical judgment and nursing practice (see Research highlight).

Research focus

Professional nursing practice requires critical thinking skills and problem solving abilities. Nurse regulatory authorities worldwide require these skills to be demonstrated by nursing graduates prior to registration or licensure. The acquisition of these skills is a cyclical process which benefits from initial theoretical and practical education and ongoing clinical experience.

Research abstract

The purpose of this descriptive qualitative study was to describe ethical reasoning in 70 baccalaureate nursing students undertaking a nursing ethics unit of study. These students were exposed to unique elements of maternal/child health nursing and were asked to write about their experiences during practice. They were asked to incorporate into their reflective writing: ethical principles, informal fallacies in thinking and theories of ethics to frame their clinical experiences. The ‘what’, ‘so what’ and ‘what now’ format was used for journal entries.

The reflective clinical journals were analysed using a model developed to evaluate the level of reflection engaged in by the student. Levels of reflection included: reflectivity (describes), affective (emotionally aware), discriminates (critically assesses), judgmental (evaluates), conceptual (identifies need for additional learning) and theoretical (demonstrates the need for change).

The students’ reflective writing focused on such topics as end-of-life decision making and care, maternal/fetal conflict, healthcare errors, pain management, professional behaviour, linguistic barriers to informed consent, application of technology in futile circumstances and observations of healthcare teams working through decisions. The overwhelming emergent theme was in the process of becoming. Themes related to this included: practising as a professional, lacking confidence as a student, advocating for patients, being just in care delivery, identifying spiritual dimensions of care, making a commitment to practice with integrity and caring enough to care. The study focused on exploring reasoning in nursing practice as a process, with student nurses experiencing becoming, professionalising, institutionalising and working in a team as they deal with dilemmas.

Evidence-based practice

• Nurses must maintain the motivation to inquire into underlying assumptions about practice.

• Reflective journalling as a student or a graduate nurse is useful in gaining personal insight and professional growth.

• The acquisition of new knowledge is constant and is woven into current skills and experience. A critical approach enhances this cycle of professional development.

Reference

Callister L, Luthy K, Thompson P, Memmott R. Ethical reasoning in baccalaureate nursing students. Nurs Ethics. 2009;16(4):500–510.

The process of reflection requires you to consider the underlying or implicit assumptions, beliefs, values and cultural norms influencing your practice, to make them explicit and then consider them in light of the available evidence or literature. Critical reflection should prompt you to ask questions such as:

• What underlying assumptions, beliefs, values or cultural norms influencing practice were uncovered here?

• What structural or contextual (e.g. sociopolitical, economic, organisational) factors influenced my choices and behaviours, and whose interests are being served by these norms and influences?

• Are they consistent with professional nursing practice?

• What new understandings were gained from this process?

As part of this process, you need to engage with the literature for validation of explanations and meaning. Nursing educators will often use critical questioning to cause you to reflect deeply on how and why you make certain assumptions and also lead you to a more professional process of critical thinking with the goal that you will develop your own habits of critical reflection (Riddell, 2007).

Intuition

Expert nurses sometimes report experiencing feelings about clients in their care that they are unable to explain. The noticing of subtle changes or deterioration is sometimes referred to as intuition. For example, an experienced nurse may enter the room of a postoperative client and know immediately that the client’s condition has deteriorated. This is known intuitively, without objective data such as vital signs. Similarly, a community nurse may know by looking at a client’s expression and a quick check of the surroundings that the client is not coping with in-home care. At a moment’s notice, these nurses appear to have knowledge available to them without having to exercise conscious reasoning.

It is important to remember that high-quality nursing practice does not rely on intuition. Indeed, many experienced and expert nurses say that this intuitive reaction is the trigger for a more systematic assessment of the client and that it is a function of experience in similar situations (Traynor and others, 2010). Each clinical situation demands careful thought. Even if a nurse believes intuitively that a client is experiencing a change, it is important to confirm that finding through appropriate clinical assessment.

Learning to become a critical thinker is a requirement for graduates of all nursing undergraduate programs and for entry to practice as a beginning registered nurse (RN). Critical thinking as expressed through clinical judgment and decision making is assessed continuously throughout your nursing program in order that you will be able to accurately identify client problems, safely manage these problems and justify the actions you take with relevant rationales or logic.

• CRITICAL THINKING

Think of an incident that has occurred while you were on clinical placement. Potential incidents might include:

• ethical situations/dilemmas encountered

• a confrontation with another member of staff

• being involved in or witnessing discriminatory/biased nursing care

• dealing with death for the first time.

Attempt to analyse the incident using a reflective process:

1. Describe, as thoroughly as you can, what you did.

2. Analyse the steps you used in your decision-making processes.

3. What underlying assumptions, beliefs, values or cultural norms influenced your actions?

4. What structural or contextual (e.g. sociopolitical, economic, organisational) factors influenced your choices and behaviours, and whose interests are being served by these norms and influences?

5. What explanations of the experience might be posed?

6. Are the proposed explanations supported by the literature?

7. What did you learn from the experience, and how would it inform your future practice in this situation?

Clinical decisions in nursing practice

Alfaro-LeFevre (2009:99) explains the concept of clinical judgment well:

Developing clinical judgement—clinical reasoning skills—is one of the most important and challenging aspects of becoming a nurse. It’s important because people’s lives depend on it. It’s challenging because thinking in the clinical setting is often fraught with more anxiety and risks than any other situation … [it] entails things like knowing what to look for, how to recognise when a patient’s status is changing, and what to do about it. For beginners, this is particularly taxing because it requires an ability to recall facts, put them together into a meaningful whole, and apply the information to a current clinical situation (a situation which is often fluid and changing).

Nurses have the important responsibility of making accurate and appropriate clinical decisions. Many clients have problems for which there are no clear textbook solutions. Their clinical signs and symptoms, the information clients share about themselves, and the situation in which the nurse meets them do not automatically present the nurse with a clear picture of a client’s needs and what actions should be taken to meet those needs. The development of the critical thinking skills of challenging assumptions, reflecting on experience and questioning one’s usual way of thinking while promoting patient safety through the process of clinical judgment and decision making is crucial to the delivery of high-quality patient care (Ashcraft, 2010).

Knowledge base

An essential component of critical thinking and clinical decision making is the nurse’s specific knowledge base. This varies according to the nurse’s educational experience, including initial nursing education, continuing clinical education courses and additional degrees that the nurse may pursue. A nurse’s knowledge base includes information and theory from the basic sciences, humanities and nursing, consistently updated by subscribing to current journals and library access. The broad knowledge base gives the nurse a holistic view of clients and their healthcare needs. The depth and extent of knowledge influence the nurse’s ability to think critically about nursing problems.

Nurses need to know how to make sense of what is learned about a client by first ‘having a sound theoretical knowledge and the ability to notice clinical signs, interpret observations, respond appropriately and reflect on actions taken’ (Tanner, 2005:48). Nurses reflect on new knowledge and experiences as they come along, listening to other caregivers’ views, identifying the nature of the client’s problems, and selecting the best solutions for improving the client’s health. Over time, the nurse gains the expertise to test and refine nursing approaches, to learn from successes and failures and to appropriately apply the findings of nursing research. The ability to think critically through the application of knowledge and experience, problem solving and decision making is central to professional nursing practice.

Clients present to healthcare settings with various experiences, behaviours, social perspectives and values, as well as signs and symptoms of health alterations. To add to the complexity of clinical decision making, many of the variables can change while caring for a given client. In the presence of such variation, the nurse observes the client closely, explores ideas and inferences about client problems, considers scientific principles relating to the problems, recognises the problems and develops an approach to care. The nurse thinks creatively, seeks new knowledge as necessary, acts quickly when events change and makes sound decisions that promote the client’s wellbeing.

THE OVERLOOKED SYMPTOM

I came to work that morning and had two patients in our transplant intensive care unit. One was a 22-year-old man who had received a liver transplant about 48 hours earlier. When I was doing my morning head-to-toe check, I found that he was very sleepy, his eyes were closed, he was jaundiced and he wouldn’t respond when I talked to him. When he did try to talk to me, he mumbled incomprehensibly.

I knew these symptoms were a problem. As an experienced transplant nurse, I knew that when you give somebody a liver and it works, they’re not jaundiced and they’re alert. They’re perky, eating, talking and even walking the halls.

This young man was doing none of that. So I checked all his vital signs, his blood pressure, pulse, temperature. Everything was where it should have been at that point in time, two days post transplant. Although his urine output was okay, the urine was a dark amber colour—which was a concern. I did his morning lab work, and everything was fine. But I was still worried. As the shift progressed, he became more lethargic and sleepy. I did another set of blood work on him, and it started to document that life in his liver was deteriorating. His urine output was now a very thick sludge that was brown-coloured and basically unmeasurable as a liquid.

I paged the resident, who blew me off with some comment like, ‘I’m the doctor,’ and so I shouldn’t worry. I told him bluntly that I was worried and that I was going to talk to the chief resident, and he said, ‘No, don’t call the chief resident. I think it’s all right, but I’m going to keep an eye on him.’ To which I replied, ‘I am, too.’

A few hours later, when I became more concerned because the patient was even more unresponsive, I paged the resident again and got the same response.

‘Look,’ I told him, ‘I’m sorry, I’m going to call the chief or the surgeon because this is not good; we’re wasting time,’ and I hung up.

Just as I got off the phone with the resident, the surgeon walked in. ‘Lou,’ I said, ‘look, this young guy’s in liver failure. His liver has failed.’

I presented all the data supporting this conclusion. I explained that he was going into a hepatic coma, becoming encephalopathic. He was filling up with poisons that his new transplanted liver was not able to detoxify. Because I had been a transplant nurse for over eight years, I determined this even without doing any neurological testing.

I was right. Indeed, his new blood work reflected a failed liver. The other critical liver lab values also reflected that fact. So did his urine. The brown dark sludge in his urine was bile that the liver was not utilising properly (usually you excrete your bile in your stool, which is why your stool is brown). The fact that his labs were normal in the morning was meaningless because they had rapidly changed over the course of the shift.

‘We have to put him back on the list to get a new liver,’ I told the surgeon. ‘We’re wasting time by not being proactive.’

The surgeon gave the patient a once-over and agreed that I was spot-on. We immediately relisted the young man. He got a transplant, not that night but the next. Forty-eight hours later, he was sitting up in bed, eating and chatting. Six days later, he went home with his parents and younger brother.

From: Stecher J 2010 The overlooked symptom. In: S. Gordon, editor, When chicken soup isn’t enough: stories of nurses standing for themselves, their patients, and their profession. New York, Cornell University Press, pp. 66–7.

• CRITICAL THINKING

The expert RN in the situation described in the clinical example draws on her knowledge, skills and experience to make a sound clinical judgment and intervenes to save the patient’s life.

1. Because nurses’ assessment and clinical decision-making skills are often invisible to others, many people often mistakenly attribute this important work to others in the healthcare team, such as the doctor. Take a moment to think about the critical role nurses play in making decisions about patient care.

2. What might have happened to the patient in the above scenario without knowledgeable and skilled nursing care?

Development of critical thinking skills in nursing

As a nurse gains new knowledge and develops into a competent professional, the ability to think critically to make a sound clinical judgment expands. Clinical judgments require many types of knowledge: knowledge which is abstract, generalisable and applicable in many circumstances; that which grows with experience and is filled out with practice which aids instant recognition of clinical states; and that which is very localised and individualised by knowing an individual client and having a shared understanding of that client’s needs (Tanner, 2006).

Unless a nurse has the opportunity to practise and make decisions about client care, critical thinking in clinical decision making will not develop. A nurse learns from observing, sensing, talking with the client or a number of clients in similar situations and then reflecting on the experience. Clinical experience is the laboratory for testing nursing knowledge. The nurse learns that textbook approaches lay important groundwork for practice, but adaptations or revisions in approaches may need to be considered to accommodate the setting, the unique qualities of the client, and the experience the nurse has gained from using the approaches for previous clients. Differing clinical practice outcomes between clients and settings can provide grounds for the initiation of nursing research, and contribute to new knowledge. Perhaps the best lesson to be learned by a new nursing student is to value all client experiences, which become stepping stones for building new knowledge and stimulating innovative thinking.

A learner trusts that experts have the right answers for every problem. Thinking is concrete and based on a set of rules or principles. For example, a beginning nurse generally uses an institution’s procedures manual to confirm how to insert a urinary catheter. The nursing student follows the procedure step by step without adjusting the procedure to meet a client’s unique needs (i.e. the level of explanation given is educationally appropriate). For beginning problem solvers, answers to complex problems are either right or wrong, and one right answer usually exists for each problem. This is an early step in the development of reasoning ability, revealing that the individual has had limited experience in critical thinking.

At a more complex level of problem solving, a person begins to detach from authorities and to use a range of logical thought processes to analyse and examine alternatives more independently. The person’s thinking abilities and initiative begin to change. Through increasing knowledge and the use of reflection, the nurse realises that alternative, perhaps conflicting, solutions do exist. Consider, for example, a 60-year-old woman who has undergone abdominal surgery. She is refusing to take prescribed analgesic medication prior to ambulation and is at risk of delaying her recovery and return home. The nurse discovers that the patient is afraid she may become dependent on the medication; she discusses other forms of pain control which may be acceptable to the patient to either replace or minimise the use of the prescribed medication. The nurse has become more creative and there is a willingness to deviate from standard procedures.

Eventually, the nurse anticipates the need to make choices without assistance from others and then assumes accountability for them. At this level, the nurse does more than just consider the complex alternatives a problem poses: the nurse chooses an action or belief based on the alternatives available and stands by it. Sometimes an action may be no action, or the nurse may choose to delay an action until a later time—but does so as a result of experience and knowledge. Because the nurse assumes accountability for the decision, attention is given to the results of the decision and a determination of whether it was appropriate. Committed critical thinkers act in support of the client and of the professional values that underlie the discipline of nursing with regard to legal and ethical issues.

Critical thinking processes

General critical thinking processes are not unique to nursing, and are used in other disciplines and in non-clinical situations. Specific critical thinking competencies in clinical situations include diagnostic reasoning, clinical inferences and clinical decision making. Nurses, social workers, doctors and other healthcare professionals use these competencies when deciding about the clinical care and support of clients. The specific critical thinking competency in nursing is the nursing process.

Problem solving

Problem solving involves obtaining and using information to reach acceptable solutions when there is a gap between what is occurring and what should be occurring. When a person starts to water the lawn and finds that water is not flowing from the hose nozzle, a quick problem-solving approach involves looking for kinks or leaks in the hose. An example of problem solving in a clinical situation might involve a nurse entering a client’s room and finding the client lying almost flat. The nurse knows that the client underwent upper abdominal surgery and should maintain an upright sitting position to aid lung expansion and encourage deep breathing to facilitate oxygenation. The nurse suspects the client is having pain, but instead learns quickly through questioning that he is uncomfortably cold and this is why he is attempting to withdraw under the bedding. The nurse repositions the client and provides an additional blanket for warmth around the upper body. Returning to the client’s room 30 minutes later, the nurse finds the client asleep but maintaining the correct position. The nurse obtained information that clarified the client’s source of discomfort and tested a solution that was successful.

Effective problem solving also involves the nurse evaluating a solution over time to be sure that it is still effective. It may become necessary to try different options if a problem recurs. Solving a problem in one situation allows the nurse make a decision which applies knowledge learned to future client situations.

Decision making

In decision making, a person is faced with a problem or situation where a choice determines a course of action. Decision making is an endpoint of critical thinking that leads to problem resolution. To make a decision, an individual must recognise and define the problem or situation, assess all options, weigh each option against a set of criteria, test possible options, consider the consequences of the decision and then make a final decision. Although the set of criteria seem to follow a sequence of steps, decision making involves moving back and forth in considering all criteria. Using such a process leads to a conclusion that is informed and supported by evidence and reasons.

Evidence-based practice requires that decisions about client care are made based on the best available evidence (refer to Chapter 7). An example could involve a nurse deciding on a choice of dressings for a client with a surgical wound. Several criteria are usually considered when selecting a dressing: location and size of the wound, presence and type of drainage and whether an infection is present. As well, the client’s nutritional status, skin integrity and degree of mobility are factors to be considered. The nurse will carry out a full assessment of the client’s health status, followed by a more focused assessment of the client’s wound, which may include consultation with a senior colleague or expert wound care nurse practitioner. The nurse will then review the types of dressing materials available and the current research evidence as to their suitability for the individual client. Use of all of this information increases the likelihood of safe practice.

When making clinical decisions and judgments, the nurse first asks why a decision is necessary. For example, Mrs Pasha is an 80-year-old client who lives with her married daughter and her family. Her daughter Siva, Mrs Pasha’s primary caregiver, has three school aged-children and a husband who works full-time; she also works outside the home part-time. During a recent clinic visit, the RN observes a bruised area of the skin over Mrs Pasha’s right hip. Mrs Pasha describes it as a scrape that she received when she slipped and hit the edge of her bath. Knowing the client’s age and the physiological changes that occur with ageing, the RN knows a decision is needed about whether her client is living in a safe environment. The RN must also make decisions about what actions are needed to promote healing and prevent further injury. Before a decision can be made, the RN needs to consider the client’s home environment and whether repeated injuries have been part of the client’s history, to think critically about the client and her family context, to question assumptions she may be making based on her current knowledge and experience and seek other professional assistance should she need it. A framework for decision-making criteria should be established so that appropriate choices can be made. Criteria should include the following:

• What needs to be achieved? (Healing of the skin, a safe home environment)

• What needs to be preserved? (Mobility, nutrition, and comfort and safety)

• What needs to be avoided? (Further tissue injury or infection and further falls)

Diagnostic reasoning and inferences begin whenever a nurse receives or perceives information about a client in a particular clinical situation. It is a process of determining a client’s health status. For example, a client may present symptoms that are indicative of a neurological dysfunction. The nurse needs to retrieve knowledge regarding symptoms and then reason in a direct and precise way to determine the nature of the client’s problem. Diagnostic reasoning enables the nurse to assign meaning to the behaviours, physical signs and reported client symptoms. The process involves a series of clinical judgments made during and after data collection, resulting in an informal judgment or formal diagnosis. Formulating a nursing diagnosis (see Chapter 7) is an example of diagnostic reasoning requiring a high degree of accuracy (NANDA, 2007). Another example of diagnostic reasoning involves the nurse who makes ongoing clinical assessments on the basis of a client’s known medical problem. This process helps in making clinical inferences or judgments about a client’s progress. When certain symptoms present themselves, the nurse considers all variables influencing the client in addition to the medical diagnosis, and then infers if the client is doing better or worse.

After considering each of the criteria, the nurse sets priorities as they relate to the client’s situation (see Chapter 7). Because different clients bring different variables to a situation, an activity may be more of a priority in one situation than another. After determining the order of priority, the nurse chooses the nursing interventions most likely to relieve each problem. This could include nurse-administered interventions and/or client self-care strategies. The nurse collaborates with the client and then chooses, implements and evaluates each approach. The nurse tries to anticipate what might go wrong and considers alternative approaches to minimise or prevent problems. For example, the RN will talk with Mrs Pasha’s daughter, Siva, about having someone check the condition of the bathroom to see if there are any obstacles creating a risk of falls. A complete home-safety assessment would be most helpful. Based on the findings, the RN makes recommendations to Mrs Pasha and Siva on ways to minimise any hazards or obstacles so that further injury is less likely.

Nurses make decisions about individual clients and groups of clients. A nurse who works in a busy hospital unit is likely to care for several clients. The nurse uses criteria such as the clinical condition of the clients, risks involved in treatment delays and the clients’ expectations of care to determine which clients have the greatest priorities for care. For example, a client who is experiencing a sudden drop in blood pressure along with a change in consciousness requires the nurse’s attention immediately, as opposed to the client who needs to be helped to walk down the hallway. The nurse visits the client who has no visitors and has recently been diagnosed with cancer before checking on the recovering surgical client whose family has just arrived. For nurses to be able to manage the wide variety of problems associated with groups of clients, skilful, prioritised decision making is critical (see Box 5-2).

BOX 5-2 CLINICAL DECISION MAKING FOR GROUPS OF CLIENTS

• Identify the problems of each client.

• Compare clients and determine which problems are most urgent on the basis of basic needs, the client’s changing or unstable status and problem complexity.

• Anticipate the time it will take to attend to priority problems.

• Decide how to combine activities to resolve more than one problem at a time.

• Consider how to involve the client as a decision maker and participant in care.

• CRITICAL THINKING

Mrs Popopulous, aged 65, is visiting the clinic 1 month after discharge from the hospital following recovery from a hip replacement. Her husband, Spiro, expresses concern about her refusal to maintain her prescribed exercise regimen and her unwillingness to leave the house for the usual family get-togethers. Mrs Popopulous suggests that to go to family gatherings would put a strain on her relatives as she is not well enough to cook for the communal table and would be a burden.

How would you explore this further with Mrs Popopulous and use a problem-solving approach to help her adhere to the prescribed exercise regimen?

Clinical judgment model

Many nurse researchers have explored the concepts and processes used by nurses when making clinical judgments. The process of making sound clinical judgments is a skill critical to the delivery of individualised client care when nurses are faced with increasingly complex clinical contexts that include competing priorities. Critical thinking and decision making is complex, and a model can help to explain the factors involved in making clinical judgments.

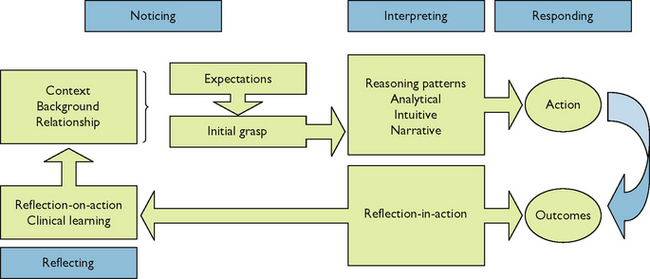

One of the best models that explain how experienced nurses make clinical judgments in practice was developed by Tanner (2006). The overall process of clinical judgment includes four key aspects (see Figure 5-1):

• A perceptual grasp of the situation at hand, termed noticing. The experienced RN immediately recognises abnormal data and possible problems based on their expectations of each clinical encounter, which stem from their knowledge of the particular patient and his or her patterns of responses, their clinical or practical knowledge of similar patients, drawn from experience, and their textbook knowledge.

• Developing a sufficient understanding of the situation to respond, termed interpreting. Noticing triggers reasoning patterns that allow the nurse to interpret the situation and respond with interventions. For example, in order to confirm or refute their initial grasp of the situation, the experienced RN is able to quickly focus their assessment and gather additional data.

• Deciding on a course of action deemed appropriate for the situation, which may include no immediate action, termed responding.

• Attending to the patient’s responses to intervention, and reviewing the outcomes of the action, focusing on the appropriateness of all of the preceding aspects (i.e. what was noticed, how it was interpreted, and how the nurse responded), termed reflecting. Thus, reflection completes the cycle, contributing to the RN’s ongoing clinical knowledge development and their capacity for clinical judgment in future situations.

The model emphasises the role of the nurse’s background in terms of knowledge and skills brought to the situation, the context of a particular situation in which a judgment is to be made, and the importance of the quality of the relationship that the nurse has with the client. Tanner asserts that ‘nurses use a variety of reasoning patterns alone or in combination and reflection on practice is often triggered by a breakdown in clinical judgement and is critical for the development of clinical knowledge and improvement in clinical reasoning’ (Tanner, 2006:204). The model emphasises these concepts as ‘central to what nurses notice and how they interpret findings, respond, and reflect on their response’ (p. 204).

Standards for critical thinking

Critical thinking includes intellectual and professional standards. These standards are the criteria for determining the soundness, justness and appropriateness of critical decisions and judgments. The use of intellectual standards involves a rigorous approach to clinical practice and demonstrates that critical thinking cannot be done haphazardly. When a nurse considers a client problem, it is important to apply standards such as preciseness, accuracy and consistency to ensure that clinical decisions are sound or valid. For example, a RN is caring for a client who has developed a large ulcerated wound on her leg following a spider bite. At each daily assessment the RN carefully inspects the wound for colour and warmth and signs of infection; he measures the size of the wound and inspects for signs of healing. He questions the client about her fluid and food intake and her ability to be mobile and to manage self-care. All of this information is accurately recorded in order to make a comparison and a judgment about progress at the next inspection. The use of the universal standards of clarity, accuracy, precision and relevance means that the nurse has a command of these standards (Huckaby, 2009).

Professional standards for critical thinking refer to ethical criteria for nursing judgments, criteria to be used for evaluation and criteria for professional responsibility. Application of professional legal and ethical standards requires that nurses use critical thinking for the good of individuals or groups (Freegard, 2007). Standards also ensure that the highest level of nursing care is promoted.

Client care requires more than just the application of scientific knowledge. Being able to focus on a client’s values and beliefs helps a nurse to make clinical decisions that are just, faithful to the client’s choices and beneficial to the client’s wellbeing. Critical thinking also requires the use of evidence-based criteria for evaluation when clinical judgments are made. These criteria may be based on standards of nursing care recognised in the professional literature or developed by clinical agencies or professional organisations. The evaluation criteria set the minimum requirements necessary to ensure quality of care. For example, clinical pathways used in managing the care of clients with designated medical diagnoses include recommended interventions and outcomes that are used for evaluating the client’s clinical progress. The outcomes provide evaluation criteria with which clinical staff can make sound and consistent judgments. Evaluation criteria also include norms established through research in nursing practice to be used when determining the clinical status of a client.

The standards of professional responsibility that a nurse strives to achieve are those standards cited in nursing practice acts, national regulatory and treatment guidelines, institutional practice guidelines and professional organisations’ standards of practice. In Australia the Nurses Board of Australia has developed and published National Competency Standards and the Code of Professional Conduct for Nurses in Australia (www.nursingmidwiferyboard.gov.au). The Nursing Council of New Zealand, Te Kaunihera Tapuhi o Aotearoa, has similarly developed and provided standards for the measurement of competence and professional practice (www.nursingcouncil.org.nz).

Critical thinking synthesis

Paul and Elder (2005) have described critical thinking as a process of reasoning and judgment which individuals use to assess goals and purposes, questions and problems, information and data, conclusions and interpretations, concepts and theoretical constructs, assumptions, implications and consequences, points of view and differing frames of reference. As described earlier, critical thinking is non-linear. In other words, it is not simply a prescribed series of ordered steps that one follows to make a decision. Critical thinking is ongoing, with information being analysed from many sources.

The nursing process is the traditional critical-thinking competency that allows nurses to make clinical judgments and take actions based on reason. A process is a series of steps or components leading to achievement of a goal. The nursing process includes five steps: assessment, diagnosis, planning, implementation and evaluation. A nurse will assess a client’s condition, determine nursing or collaborative problems, plan care based on the identified problems, implement the plan and evaluate the results of care. This suggests that the nursing process is linear, but it is often necessary to reassess the client for changes in the original problem or the occurrence of new problems. The process is a systematic approach used by nurses to gather client data, critically examine and analyse the data, identify the client’s response to a health problem, design expected outcomes, take appropriate action and then evaluate whether the action is effective. The process incorporates general and specific critical thinking competencies in a manner that focuses on a particular client’s unique needs. The format for the nursing process is not unique to the discipline of nursing but provides a common language and process for nurses to ‘think through’ clients’ clinical problems. The nursing process is a systematic and comprehensive approach for nursing care.

Nursing practice is always changing. As new knowledge becomes available, professional nurses need to challenge traditional ways of doing things and discover those interventions that are most effective, have scientific relevance and result in better client outcomes. Consider how you will manage the rapid evolution of scientific discovery and knowledge in nursing in relation to your own practice. How may you incorporate new research findings into your patient care? The nurse’s ability to think critically demonstrates a commitment to learning and enhances the ability to positively influence nursing practice.

As the nurse engages in the nursing process for the care of a specific client, the nurse is also synthesising critical thinking knowledge, experience, standards and attitudes simultaneously. The nurse who is assessing a client’s pain does not focus only on what the client reports about the pain and what the nurse is able to observe and measure. The nurse also reflects on previous experience with clients who have had similar pain, so as to compare and contrast this new client’s response. The nurse refers to the information scientific texts have to offer about how the pain might be relieved. The nurse also displays the proper intellectual standards in being sure the pain assessment is accurate and objective. Finally, the nurse exercises the attitudes necessary for the client to be cared for fairly and responsibly. The clinical chapters in this book unite the nursing process and critical thinking model into one approach for the comprehensive care of clients.

Nursing process overview

The nursing process is used as a common framework for developing clinical practice decisions in nursing about diagnosis and treatment of human responses to health and illness (Alfaro-Lefevre, 2010). The five steps of the process are dynamic but inclusive of the clinical decision-making activities and clinical skills nurses use to help clients meet agreed-on outcomes for better health. Creativity is a characteristic of the nursing process because the process is continually changing in response to a client’s needs. For example, after a nurse has evaluated the results of nursing care and finds that the client has not improved, the nurse can reassess the client’s condition to update data, redefine problems and select new interventions. The nursing process is a blueprint for care. Critical thinking is the cognitive process the nurse uses when developing and implementing the nursing process.

The nursing process provides a creative, organised structure and framework for the delivery of nursing care, yet it is flexible enough to be used in all settings. When nurses use the nursing process, they are able to identify a client’s healthcare needs, determine priorities, establish goals and expected outcomes of care, establish and communicate a client-centred plan of care, provide appropriate nursing interventions and evaluate the effectiveness of nursing care. At any time in the care of a client, a nurse may move back and forth from one step of the process to another should new data emerge (see Chapters 6 and 7.

KEY CONCEPTS

• Critical thinking is purposeful and goal-oriented. It involves the identification and challenging of assumptions, consideration of priorities in a situation, the exploration of alternatives and application of reason and logic in making informed decisions.

• A critical thinker faces problems without forming a quick, single solution, and focuses on the options for what to accept and act on.

• Reflection is a systematic, rigorous, disciplined way of thinking, with its roots in scientific inquiry.

• Each clinical experience is a lesson for the next one, with a nursing student building a knowledge base that can be confidently applied in daily practice.

• The nursing process enables a critical thinking approach to clinical nursing care.

ONLINE RESOURCES

Council of Deans of Nursing and Midwifery (Australia and New Zealand); policy and position statements, www.cdnm.edu.au

Nursing and Midwifery Board of Australia, www.nursingmidwiferyboard.gov.au

2008 Code of professional conduct for nurses in Australia

2008 National competency standards for the registered nurse.

Nursing Council of New Zealand

Royal College of Nursing Australia; policy, position statements and guidelines, www.rcna.org.au

REFERENCES

Alfaro-Lefevre R. Applying nursing process: a tool for critical thinking, ed 7. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins, 2010.

Ashcraft T. Solving the critical thinking puzzle. Nurs Management. 2010;41(1):8–10.

Castledine G. Critical thinking is crucial. Bri J Nurs. 2010;19(4):271.

Freegard H. Ethical practice for health professionals. Melbourne: Thompson, 2007.

Huckaby L. Clinical reasoned judgement and the nursing process. Nurs Forum. 2009;44(2):72–78.

Kuiper RA, Pesut DJ. Promoting cognitive and metacognitive reflective reasoning skills in nursing practice: self regulated nursing theory. J Adv Nurs. 2004;45(4):381.

NANDA. 2012–14 Nursing diagnosis: definitions and classification. Philadelphia: NANDA, 2007.

Paul R, Elder L. Critical thinking: tools for taking charge of your professional and personal life. New Jersey: Prentice Hall, 2005.

Riddell T. Critical assumptions: thinking critically about critical thinking. Nurs Ed. 2007;46(3):121–126.

Tanner CA. What have we learned about critical thinking in nursing? Nurs Ed. 2005;44(2):47–48.

Tanner CA. Thinking like a nurse: a research based model of clinical judgement in nursing. J Nurs Ed. 2006;45(6):201–211.

Traynor M, Boland M, Buus N. Autonomy, evidence and intuition: nurses and decision-making. J Adv Nurs. 2010;66(7):1584–1591.