Chapter 14 NURSING MANAGEMENT: infection and human immunodeficiency virus infection

1. Evaluate the impact of emerging and re-emerging infections on healthcare.

2. Outline the ways that nurses can decrease the development of resistance to antibiotics.

3. Explain the ways that human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is transmitted and the factors that affect transmission.

4. Describe the pathophysiology of HIV infection.

5. Depict HIV disease progression in the spectrum of untreated infection.

6. Identify the diagnostic criteria for acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS).

7. Explain methods of testing for HIV infection.

8. Discuss the collaborative management of HIV infection.

9. Summarise the characteristics of opportunistic diseases associated with AIDS.

10. Describe the long-term consequences of HIV infection and/or treatment of HIV infection.

11. Compare and contrast the methods of HIV prevention that eliminate risk and those that decrease risk.

12. Describe the nursing management of HIV-infected patients and HIV-at-risk patients.

acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS)

human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)

Infections

Infection occurs when a pathogen (a microorganism that causes disease) invades the body, begins to multiply and produces disease, usually causing harm to the host. The signs and symptoms of infection are a result of the pathogen, as well as inflammation. Infections can be divided into localised, disseminated and systemic disease. A localised infection is limited to a small area. A disseminated infection has spread to areas of the body beyond the initial site of infection. Systemic infections have spread extensively throughout the body, often via the blood.

CAUSES OF INFECTIONS

Many microorganisms can cause infections. The most common are bacteria, viruses, fungi and protozoa. Bacteria are one-celled organisms that are common throughout nature. Many bacteria are normal flora; they live harmoniously in or on the human body without causing disease under normal circumstances. Normal flora protects the human body by preventing the overgrowth of other microorganisms. Escherichia coli, for example, are bacteria that are part of the normal flora in the large intestine.1

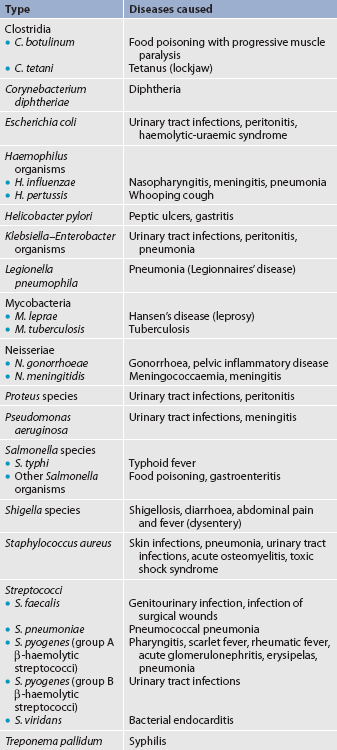

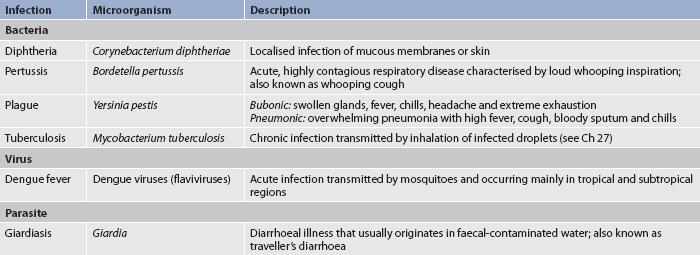

Bacteria cause disease in two ways: they can enter the body and grow inside human cells (e.g. tuberculosis [TB]) or they can secrete toxins that damage cells (e.g. Staphylococcus aureus). Bacteria are divided into categories based on the shape of their cells. Cocci such as streptococci and staphylococci are round. Bacilli are rod-shaped and include tetanus and TB. Curved rods include Vibrio species, one of which causes cholera. Spirochetes are spiral-shaped and include the organisms that cause leprosy and syphilis. Table 14-1 lists common bacteria and the diseases that they cause.1,2

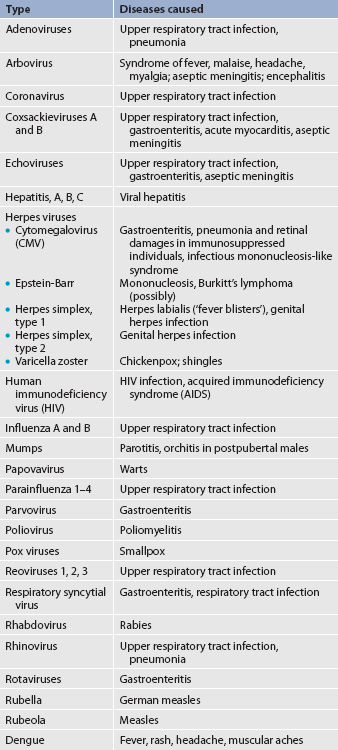

Viruses, unlike bacteria, do not have a cellular structure. They are simple infectious particles that consist of a small amount of genetic material (either ribonucleic acid [RNA] or deoxyribonucleic acid [DNA]) and a protein envelope. Viruses are parasites and can reproduce only after releasing their genetic material into the cell of another living organism. Examples of diseases caused by viruses are presented in Table 14-2.

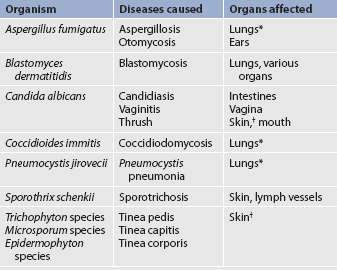

Fungi are organisms similar to plants, but they lack chlorophyll. Mycosis is any disease caused by a fungus. Pathogenic fungi cause infections that are usually localised, but can become disseminated in an immunocompromised person. Athlete’s foot and ringworm are two common mycotic infections. Some fungi are normal flora in the body, but when overgrowth occurs, disease can result. Overgrowth of Candida albicans, for example, can cause candidiasis in the mouth (thrush), oesophagus, intestines and vagina.1 Other fungi and their respective mycotic infections are listed in Table 14-3.

Protozoa are single-cell, animal-like microorganisms. Protozoa normally live in soil and bodies of water. When introduced into the human body, infection can result. Amoebic dysentery and giardiasis are caused by protozoal parasites. Malaria is caused by a sporozoa called Plasmodium malariae.1,2

Prions are infectious particles that contain abnormally shaped proteins. Not all prions cause disease, but those that do typically affect the nervous system. They can cause a group of illnesses called transmissible spongiform encephalopathies (TSEs). Some of the more common TSEs include Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease and bovine spongiform encephalopathy in cattle (also known as mad cow disease).3,4

EMERGING INFECTIONS

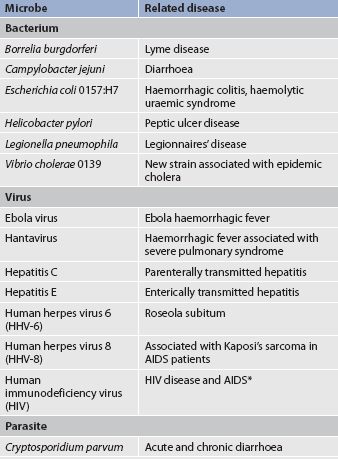

An emerging infection is an infectious disease whose incidence has increased in the past 20 years or threatens to increase in the immediate future. Examples of emerging infections are described in Table 14-4. Emerging infectious diseases can originate from unknown sources, contact with animals, changes in known diseases or even biological warfare. For example, severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and avian flu come from animal sources, whereas others (e.g. Staphylococcus aureus) emerged when a previously treatable organism developed resistance to antibiotics. The battle against infection is an age-old problem. However, modern technologies have changed the rules of the game. Global travel, population density, encroachment into new environments, misused antibiotics and even bioterrorism have increased the risk for widespread distribution of emerging infections.5

Not too long ago many believed that science had conquered infectious diseases. Unfortunately, infections remain a leading killer of Australians and New Zealanders and the leading cause of death worldwide. For example, infectious diseases accounted for 1.3% of deaths in Australia in 2008.6 More than 30 newly recognised infectious diseases have emerged in the last three decades, including human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), Lyme disease, hepatitis C, SARS, Ebola virus and novel influenza A (H1N1) virus. Some diseases that were once thought to be under control, such as TB and drug-resistant strains of other bacteria, have re-emerged.5,7

Studies in zoonosis (the science of transmission of diseases from animals to humans) indicate that many known infectious diseases come from animal and insect vectors. The SARS outbreak in China in 2003, for example, was linked to the civet cat, a small carnivorous mammal found throughout much of Asia and Africa. Animal-borne infections are difficult to predict and to prevent.

Dengue is a viral infection transmitted by the day-feeding Aedes mosquito. The disease is a global problem but Australian outbreaks are typically confined to northern parts of Queensland.8 During 2009, there were 1398 notifications of dengue influenza A viruses that had typically spread from birds to pigs to humans. Two variants of influenza A viruses show how viruses are transmitted across species. The novel influenza A virus, H1N1, is a virus with a genetic structure similar to the influenza viruses seen in pigs, birds and humans. Scientists call H1N1 a quadruple reassortment virus because it contains components of four different influenza strains (two types of porcine viruses, one avian and one human).9 The first cases of H1N1 were documented in Mexico in 2009. Within months of its identification, H1N1 was reported in more than 70 countries around the globe. The course of infection is usually self-limited, but some individuals, especially those with other chronic conditions, young children and pregnant women, are at greater risk for complications or death from this infection.9–11 In an avian flu (H5N1) outbreak, the virus spreads directly from chickens to humans. This was first demonstrated in Hong Kong in 1997 and again in the Netherlands in 2003. Infected people generally suffer from conjunctivitis or mild influenza-like symptoms, but more than 230 deaths related to avian flu have occurred.12

The Ebola virus is an emerging disease that presents an ongoing challenge to public health since it was first seen in 1976. Ebola virus causes a severe haemorrhagic fever and is usually lethal. Therapeutic and preventative measures are extremely limited. The natural reservoir and path of transmission of the virus are unknown, which makes it impossible to effectively combat the disease.13

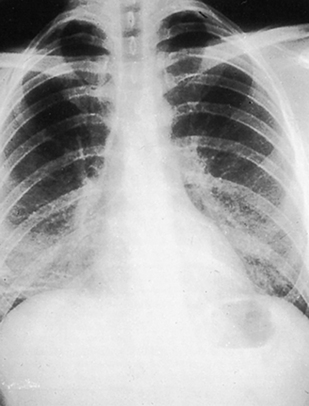

RE-EMERGING INFECTIONS

Vaccines and proper medications have led to the near eradication of some infections (such as smallpox). However, infective agents can always re-emerge if the conditions are right. Table 14-5 presents some diseases that have shown resurgence in recent decades. For example, although the incidence of TB had begun to steadily decrease by the mid-1950s, in 1984 there was a slight increase in TB cases. The growing HIV epidemic in the 1970s and 1980s contributed to the increase in TB as people with depressed immune systems contracted new cases of TB or reactivated dormant TB infections. The development of multidrug-resistant forms of TB (MDR-TB) also contributed to the increase. Local and federal governments responded to the problem and, as a result, the rates of TB are now slowly declining again.14 (TB is discussed in Ch 27.)

International travel creates a new dilemma for the local eradication of diseases. Measles, for instance, is no longer considered endemic in Australia or New Zealand but it remains a leading cause of morbidity in developing countries. Some measles cases in developed countries have been found in people who have recently travelled to measles-endemic countries.15

ANTIBIOTIC-RESISTANT ORGANISMS

Resistance occurs when pathological organisms change in ways that decrease the ability of a drug (or a family of drugs) to treat disease. Microorganisms can become resistant to classic (e.g. penicillin) as well as newer antibiotic and antiviral agents. Microorganisms are highly adaptable. They have evolved genetic and biochemical mechanisms to defend against antimicrobial actions. Genetic mechanisms include mutation and acquisition of new DNA or RNA. Biochemically, bacteria can resist antibiotics by producing enzymes that destroy or inactivate the drugs. Drug target sites are then altered so that the antibiotic cannot bind to or enter the bacteria. If the drug cannot enter the cell, it cannot kill the bacteria.16 Table 14-6 describes the most common antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

TABLE 14-6 common antibiotic-resistant organisms and treatment

| Bacteria | Resistant to: | Preferred treatment |

|---|---|---|

| Staphylococcus aureus | Methicillin | Vancomycin |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis | Methicillin | Vancomycin |

| Enterococcus faecalis | Vancomycin, streptomycin, gentamicin | Penicillin g or ampicillin |

| Enterococcus faecium | Vancomycin, streptomycin, gentamicin | Penicillin g or ampicillin |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | Penicillin g | Ceftriaxone, cefotaxime |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | Third-generation cephalosporins (e.g. Ceftazidime) | Imipenem-cilastatin, meropenem |

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE) and multi-resistant Gram-negative bacteria (MRGN) are some of the most troublesome resistant bacteria currently causing problems in Australia and New Zealand. MRSA can be acquired in a hospital setting as well as in the community. Healthcare workers exposed to MRSA can become infected and spread the infection to other healthcare workers and patients. The organism can remain viable for days on environmental surfaces and clothing. Hospital patients most at risk include those who are immunosuppressed (e.g. receiving chemotherapy), have invasive devices (e.g. indwelling catheters) or have breaks in the skin barrier (e.g. a surgical wound). VRE is hardier than MRSA and can remain viable on environmental surfaces for weeks. An antiseptic soap such as chlorhexidine is needed to kill these bacteria.17

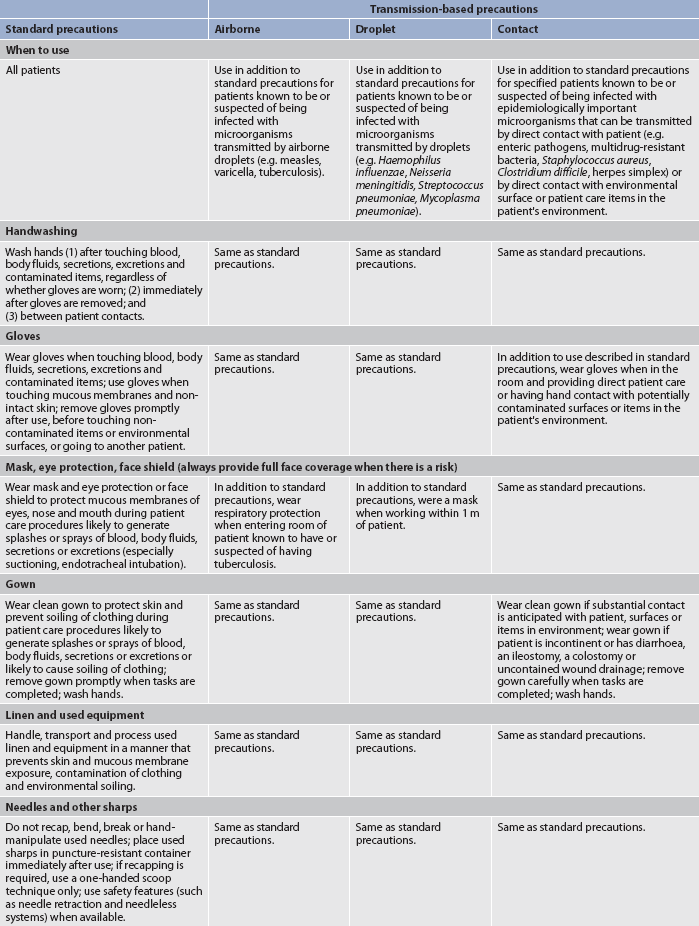

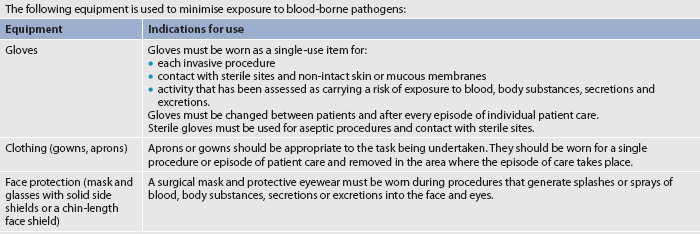

The infection control guidelines published by the National Health and Medical Research Council in Australia recommend the use of standard precautions as the primary strategy for minimising the transmission of healthcare-acquired infections (HAIs). Transmission-based precautions are used in addition to standard precautions, where the suspected or confirmed presence of infectious agents represents an increased risk of transmission.18 To prevent HAIs, it is important to understand how infections occur in healthcare settings and then institute ways to prevent them. Successful approaches for preventing and reducing harm arising from HAIs involve applying a risk-management framework to manage ‘human’ and ‘system’ factors associated with the transmission of infectious agents (see Table 14-7).18 In New Zealand, all health and disability services are required to comply with similar standards for infection control as published by Standards New Zealand19 and guidelines for the control of multidrug-resistant organisms in New Zealand.20

TABLE 14-7 Requirements for personal protective equipment

Note: selection of protective equipment must be based on assessment of the risk of transmission of infectious agents to the patient or carer, and the risk of contamination of the clothing or skin of healthcare workers or other staff by patients’ blood, body substances, secretions or excretions. All PPE must meet relevant Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) criteria for listing on the Australian Register of Therapeutic Goods (ARTG) or equivalent and should be used in accordance with manufacturer’s recommendations

Source: www.nhmrc.gov.au/australian-guidelines-prevention-and-control-infection-healthcare, accessed 12 april 2011.

Certain Gram-negative bacteria have developed the ability to produce β-lactamase, an enzyme that makes them resistant to third-generation cephalosporins (e.g. ceftriaxone). Infections caused by these bacteria manifest with signs and symptoms similar to those produced by non-resistant strains but require different antibiotics to be treated effectively. Culture specimens should be taken to determine whether the bacteria are β-lactamase producing and whether the organism is sensitive to the antibiotic selected for treatment.21

Healthcare providers may contribute to the development of drug-resistant organisms by: (1) administering antibiotics for viral infections; (2) succumbing to pressures from patients to prescribe unnecessary antibiotic therapy; (3) using inadequate drug regimens to treat infections; or (4) using broad-spectrum or combination agents for infections that should be treated with first-line medications. Patients who miss doses or do not take antibiotics for the full duration of the prescribed therapy also contribute to the development of resistance. In addition, limited resources and/or access to medications make it difficult for some patients to get adequate treatment for infections. Patients and their families should be taught that the proper use of antibiotics (see Box 14-1) is crucial to treatment success and prevention of drug-resistant pathogens.

BOX 14-1 Decrease risk of antibiotic-resistant infection

PATIENT & FAMILY TEACHING GUIDE

Include the following instructions when teaching patients and/or their carers how to decrease the risk for antibiotic-resistant infection.

1. Do not take antibiotics to prevent illness.

Doing this increases your risk of developing resistant infection. Exceptions include taking antibiotics before certain surgeries and taking antibiotics before dental work if you have a heart valve disorder.

2. Wash your hands frequently.

Hand-washing is the single most important thing you can do to prevent an infection.

Not taking your antibiotic as prescribed or skipping doses can allow antibiotic-resistant bacteria to develop.

4. Do not request an antibiotic for the flu or colds.

If your healthcare provider says that you do not need an antibiotic, chances are that you do not. Antibiotics are effective against bacterial infections but not viruses, which cause colds and flus.

Do not stop taking your antibiotic when you feel better. If you stop taking your antibiotic early, you allow the hardiest bacteria to survive and multiply. Eventually, you could develop an infection resistant to many antibiotics. You should never have leftover antibiotics.

6. Do not take leftover antibiotics.

Do not save unfinished antibiotics for later use or borrow leftover drugs from family or friends. This is dangerous because: (1) the leftover antibiotic may not be appropriate for you; (2) your illness may not be a bacterial infection; (3) old antibiotics can lose their effectiveness and in some cases can even be fatal; and (4) there will not be enough doses in a leftover bottle to allow a full therapeutic dose.

HEALTHCARE-ACQUIRED INFECTIONS

HAIs (formerly referred to as nosocomial infections) are infections that are acquired as a result of exposure to a microorganism in a healthcare setting. There are around 200,000 HAIs in Australian acute healthcare facilities each year. This makes HAIs the most common complication affecting patients in hospital.18 Surgical and immunocompromised patients are at highest risk of developing HAIs. Some bacteria that do not normally cause disease can cause infections in high-risk patients as a result of illness or treatment of illness. Any organism can cause HAIs, but certain bacteria, including Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus, Enterobacter aerogenes and various types of streptococci, are the more common culprits.22

Approximately one-third of HAIs are preventable. HAIs are often transmitted from patient to patient through direct contact by healthcare workers. Hand-washing (or using an alcohol-based hand sanitiser) between patients and procedures, as well as appropriate use of protective equipment such as gloves, remains the first line of defence in preventing the spread of HAIs. Isolated infections can be caused when bacteria that are normally present in one area of the body are introduced into another area. Therefore, care must be taken to change gloves and wash hands when moving from one task to another, even when working with one patient.18,22

How can nurses obtain accurate blood cultures?

EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICE

Clinical question

For patients with suspected catheter-related bloodstream infections (CRBSIs) (P), what are the best practices (I) to obtain accurate blood cultures (O)?

Conclusions

• Collect blood culture samples before beginning antibiotic therapy.

• Where available, a phlebotomy team should draw the samples.

• Percutaneously drawn samples need skin preparation with adequate skin contact and drying time using alcohol or tincture of iodine or alcoholic chlorhexidine (10.5%) rather than povidone-iodine.

Implications for nursing practice

• Rapid diagnosis and treatment are needed to reduce CRBSI morbidity and mortality rates.

• Notify the phlebotomy team to draw blood cultures immediately so that antibiotic therapy is not delayed.

• Start ordered antibiotic immediately after cultures are drawn.

• When the sample has been drawn through a vascular catheter, clean the catheter hub with a recommended product and allowing adequate drying time to avoid culture contamination.

P, patient population of interest; I, intervention; O, outcome(s) of interest

Gerontological considerations: infection in older adults

For older adult patients, the rate of HAIs is two to three times higher than for younger patients. Individuals in long-term care facilities have a greater incidence of illness and are at special risk for HAIs. Age-related changes (e.g. impaired immune function, comorbidities such as diabetes, physical disabilities) can contribute to higher infection rates.23

Infections common in older adults include pneumonia, urinary tract infections, skin infections and TB. Urinary tract infections are the most common HAIs in older adults residing in long-term care facilities. Patients with indwelling catheters are at particular risk. Infections in older adults often have atypical presentations, sometimes showing cognitive and behavioural changes before alterations occur in laboratory values.23 Suspicion of disease should typically begin when changes in ability to perform daily activities or in cognitive function occur. Fever should not be relied upon to indicate infection in older adults because many have lower core body temperatures and decreased immune responses. In addition, underlying diseases, increased frequency of drug reactions and institutionalisation can all complicate the management of the older adult with infection.

INFECTION PREVENTION AND CONTROL

Infection control guidelines

The infection control guidelines published by the National Health and Medical Research Council in Australia18 and the standards for infection control published by Standards New Zealand19,20 mandate that any employer whose employees are potentially exposed to infectious agents and blood from needles and other sharps must implement procedures to minimise or eliminate exposure to such materials in the workplace. Employees at risk need to be provided with appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE). Nurses need to minimise or eliminate their exposure to infectious materials and, when that is not possible, select appropriate PPE. This includes gloves, clothing and facial protection (see Table 14-7). Appropriate PPE will vary depending on the situation and nurses need to use sound judgement when deciding when and how to use protective equipment.

Infection precautions

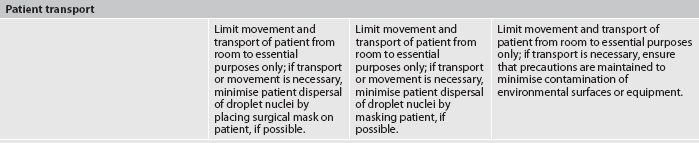

If a patient develops an infection that is considered a risk to others, infection precautions may be needed. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in the US has developed guidelines that contain two levels of precautions: (1) standard precautions, designed for the care of all patients in hospitals and healthcare facilities regardless of their diagnosis or presumed infection status; and (2) transmission-based precautions, designed for specific diseases. These guidelines for isolation precautions are shown in Table 14-8. The purpose of these precautions is to prevent the transmission of organisms from patients to healthcare providers, from healthcare providers to patients, from patients to other patients, and from providers and patients to people outside of the hospital. These are similar to the guidelines published by the National Health and Medical Research Council in Australia.18

The standard precautions system applies to: (1) blood; (2) all body fluids, secretions and excretions; (3) non-intact skin; and (4) mucous membranes. Standard precautions are designed to reduce the risk of transmission of microorganisms from both recognised and unrecognised sources of infection in hospitals. Standard precautions should be applied to all patients regardless of diagnosis or infection status. Standard precautions incorporate all requirements of the blood-borne pathogens standard outlined in the guidelines by the relevant authorities in Australia and New Zealand.

Transmission-based precautions are designed for patients known to be or suspected of being infected with highly transmissible or epidemiologically important pathogens for which additional precautions are needed to interrupt transmission and prevent infection. The three types of transmission-based precautions are airborne precautions, droplet precautions and contact precautions. They may be combined together for diseases that have multiple routes of transmission. When used either by themselves or in combination these precautions are used in addition to standard precautions.

Human immunodeficiency virus infection

Although HIV obviously had been present prior to 1981, it was not until that year that US public health officials documented the presence of a new disease that would become known as the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). By 1985 the causative agent, HIV, had been identified, and AIDS was determined to be an advanced stage of chronic HIV infection.24 Important advances have been made since then, including the development of laboratory tests to assess the number of HIV particles in the plasma (viral load), the production of new drugs, the use of combination drug therapy, the ability to test for antiretroviral drug resistance and the development of treatments to decrease the risk of transmission from mother to baby.24,25 In developed countries, the result has been decreases in the number of HIV-related deaths, improved quality of life and fewer children being born with HIV.25,26

Great progress has been made, but the epidemic is not over and around the globe continues to expand.26–29 Nursing care for patients with HIV infection continues to be a critical need that will evolve as advances in prevention and care emerge.

SIGNIFICANCE OF THE PROBLEM

By the end of 2009 in Australia, more than 10,446 cases of AIDS had been diagnosed and over 6776 AIDS-related deaths had been reported. The number of HIV diagnoses by this date was 29,395 and, as at the end of 2009, there were an estimated 20,171 people living with HIV infection in Australia. Following a substantial decline in the annual number of new HIV diagnoses during the 1990s, the numbers have steadily increased again from the lowest annual count of 718 in 1999 to 1050 in 2009. Transmission continues to be mainly through sexual contact between men. The rate of HIV diagnosis in the Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations differs little, but higher proportions of cases are attributed to heterosexual contact and injecting drug use in the Indigenous population. There is also a higher proportion of HIV infections among Indigenous women (19.1%) than non-Indigenous (7.8%).30

In New Zealand by the end of 2010, a total of 3474 people had been diagnosed with HIV, with 149 new diagnoses in 2010. As in Australia, transmission occurs predominantly through sexual contact between men. In 2010, around 50% of those diagnosed with HIV were of a European background, with 8% being Māori and 1% Pacific Islander.31 In both Australia and New Zealand, treatment has provided major advances in the ability to keep HIV-infected people healthy for longer periods of time and the death rate has fallen drastically.30

Globally, however, HIV has been devastating. Since the beginning of the pandemic it has killed more than 25 million people.25,26 Over 33 million people are living with HIV and on a yearly basis an estimated 2.7 million people become newly infected with HIV and 2 million die of HIV-related causes.32

The burden of HIV is not evenly distributed. Since the beginning of the epidemic, sub-Saharan Africa has been the most devastated, but the Caribbean, Asia, Eastern Europe and South America also have growing epidemics. In developing countries, the major route of transmission is heterosexual sex, and women and children bear a large part of the burden of illness. Industrialised countries have fared better, but have not managed to eliminate the infection or to provide appropriate care to all HIV-infected individuals. For the most part, HIV remains a disease of marginalised individuals who are disenfranchised by virtue of gender, race, sexual orientation, poverty, drug use or lack of access to healthcare.28,32,33

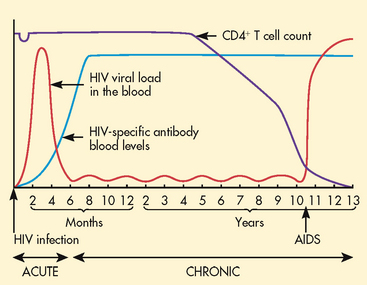

TRANSMISSION OF HIV

HIV is a fragile virus. It can be transmitted only under specific conditions that allow contact with infected semen, vaginal secretions, blood or breast milk. Transmission of HIV occurs through sexual intercourse with an infected partner, exposure to HIV-infected blood or blood products, or perinatal transmission during pregnancy, at the time of delivery or through breastfeeding.33,34 HIV-infected individuals can transmit HIV to others within a few days of becoming infected. After that, the ability to transmit HIV continues for life. Transmission of HIV is subject to the same requirements as other microorganisms (i.e. a large enough amount of the virus must enter the body of a susceptible host). The duration and frequency of contact, the volume of fluid, the virulence and concentration of the organism, and host immune status all affect whether infection is established after an exposure. The viral load is an important variable. Large amounts of HIV can be found in the blood, and to a lesser extent in the semen, during the first 6 months of infection and again during the late stages of the disease (see Fig 14-1). Unprotected sexual or blood exposure to an infected individual is more risky during these periods, although HIV can be transmitted during all phases of the disease.33–36

Figure 14-1 Viral load in the blood and CD4+ T cell counts over the spectrum of untreated human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection.

HIV is not spread casually. The virus cannot be transmitted through hugging, dry kissing, hand shaking, shared eating utensils, toilet seats, tears, saliva, urine, emesis, sputum, faeces, sweat, respiratory droplets, enteric routes or casual encounters in any setting. Healthcare workers have a low risk of acquiring HIV at work, even after a needle-stick injury.33–36

Sexual transmission

Unprotected sexual contact with an HIV-infected partner is the most common mode of HIV transmission. Sexual activity involves contact with semen, vaginal secretions and/or blood, all of which have lymphocytes that may contain HIV.

Although men who have sex with men still account for most cases of HIV transmission in Australia and New Zealand, heterosexual transmission has become more prevalent and is now the most common method of infection for women.30,31 During any form of sexual intercourse (anal, vaginal or oral), the risk of transmission is greater for the partner who receives the semen, although infection can also be transmitted to an inserting partner. This occurs because the receiver has prolonged contact with infected fluids, and helps explain why women are more easily infected than men during heterosexual intercourse. Sexual activities that cause trauma to local tissues can increase the risk of transmission. In addition, the presence of genital lesions caused by other sexually transmitted infections (STIs) (e.g. herpes, syphilis) significantly increases the likelihood of infection.37

Contact with blood and blood products

HIV can be transmitted during exposure to blood through drug-using equipment. Used equipment may be contaminated with HIV and other blood-borne organisms, and sharing that equipment can result in disease transmission.38,39

In Australia and New Zealand, transfusion of infected blood and blood products has caused few cases since routine screening of blood donors to identify at-risk individuals and testing of donated blood for the presence of HIV were implemented, thereby improving the safety of the blood supply. In countries that routinely test donated blood, HIV infection as a result of blood transfusions or haemophilia clotting factors is now unlikely.39

Puncture wounds are the most common means of work-related transmission. The risk of infection after a needle-stick exposure to HIV-infected blood is 0.3–0.4% (or 3–4 out of 1000). The risk is higher if the exposure is caused by blood from a patient with a high viral load, a deep puncture wound, a needle with a hollow bore and visible blood, a device used for venous or arterial access, or a patient who dies within 60 days. Splash exposures of blood on skin with an open lesion present some risk, but this is much lower than from a puncture wound.40

Perinatal transmission

Perinatal transmission is the most common route of infection for children. Transmission from an HIV-infected mother to her infant can occur during pregnancy, delivery or breastfeeding. On average, 25% of infants born to untreated HIV-infected women will be born with HIV. Fortunately, with the use of antiretroviral therapy (ART) during pregnancy, the risk of transmission can be reduced to less than 2%.41

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

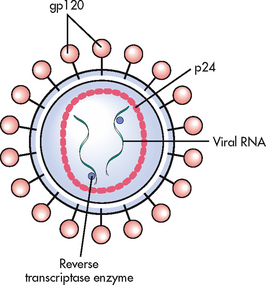

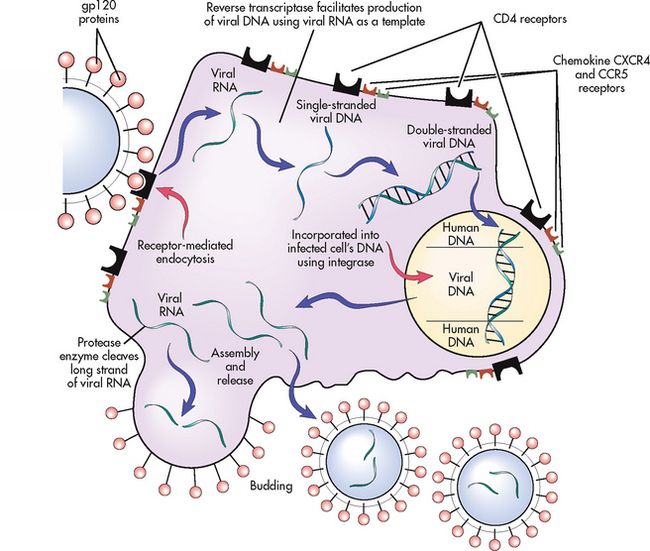

HIV is an RNA virus.24 RNA viruses are called retroviruses because they replicate in a ‘backward’ manner (going from RNA to DNA). Like all viruses, HIV cannot replicate unless it is inside a living cell. HIV can enter a cell when the gp120 ‘knobs’ (see Fig 14-2) on the viral envelope bind to specific CD4 and chemokine receptor sites on the cell’s surface (fusion; see Fig 14-3). Chemokine receptors are proteins normally found in cell membranes that respond to chemokines outside the cell to trigger a response inside the cell. HIV uses either chemokine receptor CXCR4 or CCR5 as a coreceptor (CD4 being the main receptor) to make binding and entry into the CD4+ T cells possible.

Figure 14-2 HIV is surrounded by an envelope made up of proteins (including gp120) and contains a core of viral RNA and proteins (including p24).

Figure 14-3 HIV has gp120 proteins that attach to CD4 and chemokine CXCR4 and CCR5 receptors on the surface of CD4+ T cells. Viral RNA then enters the cell, produces viral DNA in the presence of reverse transcriptase and incorporates itself into the cellular genome in the presence of integrase, causing permanent cellular infection and the production of new virions. New viral RNA develops initially in long strands that are cut in the presence of protease and leave the cell through a budding process that ultimately contributes to cellular destruction.

Once bound, viral RNA enters the cell, where it is transcribed into a single strand of viral DNA with the assistance of reverse transcriptase, an enzyme made by retroviruses. This strand copies itself, becoming double-stranded viral DNA, which then enters the cell’s nucleus and, using another enzyme called integrase, splices itself into the genome, becoming a permanent part of the cell’s genetic structure. There are two consequences of this action: (1) because all genetic material is replicated during cell division, all daughter cells will also be infected; and (2) viral DNA in the genome will direct the cell to make new HIV. HIV production in the cell starts with long strands of HIV RNA. These are cut into appropriate lengths in the presence of the enzyme protease during the budding sequence.42–44

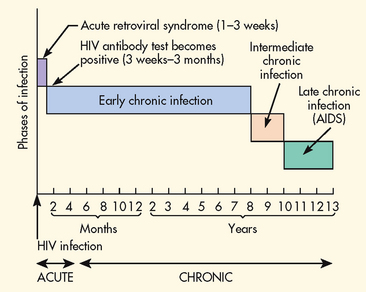

Initial infection with HIV results in viraemia (large amounts of virus in the blood). This is followed within a few weeks by a prolonged period in which HIV levels in the blood remain low even without treatment (see Fig 14-1). During this time, which may last for 10–12 years, clinical symptoms can be limited. Even without symptoms, however, HIV replication occurs at a rapid and constant rate in the blood and lymphoid tissues. A steady-state viral load can be maintained in the body of infected individuals for many years. To do this, 108–109 new viruses are produced each day. A major consequence of rapid replication is that copy errors can occur, causing mutations that contribute to treatment difficulties.42–44

In a normal immune response, foreign antigens interact with B cells and T cells. In the initial stages of HIV infection these cells respond and function normally. B cells make HIV-specific antibodies that are effective in reducing viral loads in the blood, and activated T cells mount a cellular immune response to viruses trapped in the lymph nodes.43

HIV infects human cells with CD4 receptors on their surfaces. These include lymphocytes, monocytes/macrophages, astrocytes and oligodendrocytes. Immune dysfunction in HIV disease is caused predominantly by damage to and destruction of CD4+ T cells (also known as T helper cells or CD4+ T lymphocytes). These cells are targeted because they have more CD4 receptors on their surfaces than other CD4 receptor-bearing cells. CD4+ T cells play a key role in the ability of the immune system to recognise and defend against pathogens. Adults normally have 800–1200 CD4+ T cells per microlitre (μL) of blood. The normal life span of a CD4+ T cell is about 100 days but HIV-infected CD4+ T cells will die after an average of only 2 days.43–44

HIV destroys about 1 billion CD4+ T cells every day. The body is able to produce enough new CD4+ T cells to replace the destroyed cells for many years. Eventually, however, the ability of HIV to destroy CD4+ T cells exceeds the body’s ability to replace the cells. The decline in the CD4+ T cell count impairs immune function. Generally, the immune system will remain healthy with more than 500 CD4+ T cells/μL. Immune problems start to occur when the count drops below 500 CD4+ T cells/μL and severe problems develop below 200 CD4+ T cells/μL. With HIV, a point is eventually reached where so many CD4+ T cells have been destroyed that not enough remain to regulate immune responses (see Fig 14-1). This allows opportunistic diseases (infections and cancers that occur in immunosuppressed patients and that can lead to disability, disease and death) to develop. Opportunistic diseases are the main cause of disease, disability and death in HIV infection.45

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS AND COMPLICATIONS

The typical course of untreated HIV infection follows the pattern shown in Figure 14-4. However, it is important to remember that disease progression is highly individualised and that treatment can significantly alter this pattern. The information depicted in Figure 14-4 represents data from large groups of people and should not be used to predict an individual’s prognosis.

Figure 14-4 Timeline for the spectrum of untreated HIV infection. The timeline represents the course of untreated illness from the time of infection to clinical manifestations of disease.

Acute HIV infection

Seroconversion (when HIV-specific antibodies develop) is often accompanied by a mononucleosis-like syndrome of fever, swollen lymph glands, sore throat, headache, malaise, nausea, muscle and joint pain, diarrhoea and/or a diffuse rash. Some people develop neurological complications, such as aseptic meningitis, peripheral neuropathy, facial palsy or Guillain-Barré syndrome. These symptoms, called acute HIV infection, generally occur 2–4 weeks after the initial infection and last for 1–2 weeks, although some symptoms may persist for several months. During this time a high viral load is noted and CD4+ T cell counts fall temporarily but quickly return to baseline (see Fig 14-1). Many people, including healthcare providers, mistake acute symptoms for a bad case of the flu.46

Chronic HIV infection

Early chronic infection

The median interval between untreated HIV infection and a diagnosis of AIDS is about 11 years. During this time CD4+ T cell counts remain above 500 cells/μL (normal or slightly decreased) and the viral load in the blood will be low. This phase has been referred to as asymptomatic disease, although fatigue, headache, low-grade fever, night sweats, persistent generalised lymphadenopathy (PGL) and other symptoms often occur.47

Since most of the symptoms during early infection are vague and non-specific for HIV, people may not be aware that they are infected. During this time, infected people continue their usual activities, which may include high-risk sexual and drug-using behaviours. This is a public health problem because infected people can transmit HIV to others even if they have no symptoms. Personal health is also affected because people who do not know that they are infected have little reason to seek treatment and are less likely to make behaviour changes that could improve the quality and quantity of their lives.48

Intermediate chronic infection

As the CD4+ T cell count drops to 200–500 cells/μL and the viral load increases, HIV advances to a more active stage. Symptoms seen in earlier phases tend to become worse at this point, causing persistent fever, frequent drenching night sweats, chronic diarrhoea, recurrent headaches and fatigue severe enough to interrupt normal routines. Other problems that may occur at this time include localised infections, lymphadenopathy and nervous system manifestations.47

The most common infection associated with this phase of HIV disease is oropharyngeal candidiasis or thrush (see Fig 14-5). Candida rarely causes problems in healthy adults but will eventually occur in most HIV-infected people. Other infections that can occur at this time include shingles (caused by the varicella zoster virus), persistent vaginal Candida infections, outbreaks of oral or genital herpes, bacterial infections and Kaposi’s sarcoma, caused by human herpes virus 8 (see Fig 14-6). Oral hairy leucoplakia, an Epstein-Barr virus infection that causes painless, white, raised lesions on the lateral aspect of the tongue, can also occur (see Fig 14-7). Oral hairy leucoplakia is an indicator of disease progression.45

Late chronic infection or AIDS

A diagnosis of AIDS cannot be made until the HIV-infected patient meets the criteria established by the CDC.49 These criteria (see Box 14-2) are more likely to occur when the immune system becomes severely compromised. As the viral load increases, decreases in the absolute number of lymphocytes, as well as the percentage of lymphocytes, may also occur, and the risk of developing one or more of the opportunistic diseases that contribute to disability and death increases.42,43

BOX 14-2 Diagnostic criteria for AIDS

AIDS is diagnosed when an individual with HIV develops at least one of these conditions:

1. CD4+ T cell count drops below 200 cells/μL.

2. One of the following opportunistic infections:

3. Development of one of the following opportunistic cancers: invasive cervical cancer, Kaposi’s sarcoma, Burkitt’s lymphoma, immunoblastic lymphoma or primary lymphoma of the brain.

4. Wasting syndrome: wasting is defined as a loss of 10% or more of ideal body mass.

Source: Modified from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC): 2008 Revised surveillance case definitions for HIV infection among adults, adolescents and children Aged <18 months and for HIV infection and AIDS among children aged 18 months to <13 years. 2008. Available at www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr5710a1.htm?s_cid=rr5710a1_e.

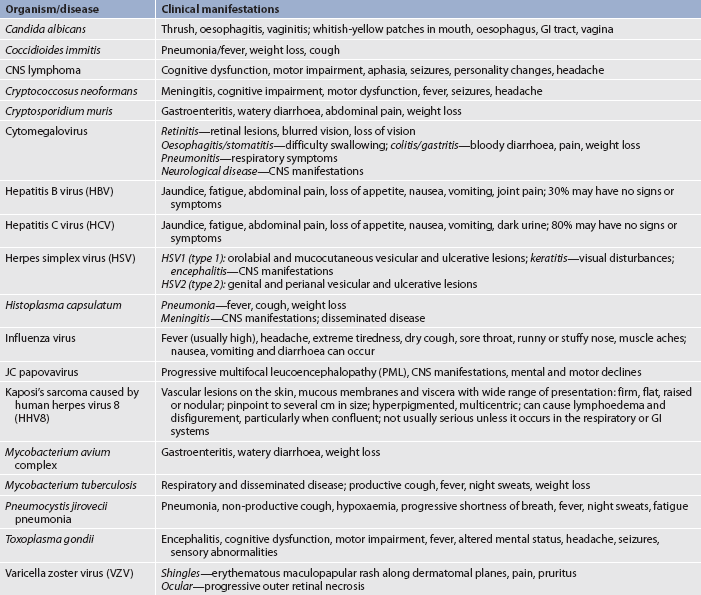

Opportunistic diseases generally do not occur in the presence of a functioning immune system. Many infections, a variety of malignancies, wasting and dementia can result from HIV-related immune impairment (see Table 14-9). Organisms that do not usually cause disease in people with functioning immune systems can cause severe, debilitating, disseminated and life-threatening infections during this stage. Several opportunistic diseases may occur at the same time, further compounding the difficulties of diagnosis and treatment. Advances in HIV treatment have led to significant decreases in opportunistic diseases because successful treatment helps maintain a functioning immune system.45

DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Diagnosis of HIV infection

The most useful screening tests for HIV are those that detect HIV-specific antibodies. The major problem with these tests is that there is a median delay of 2 months after infection before antibodies can be detected (see Fig 14-1). This creates a window period during which an infected individual may not test HIV-antibody positive. HIV screening is generally done in the sequence shown in Box 14-3. This process produces highly accurate results.45 Rapid HIV-antibody tests provide results in 20 minutes and are recommended by the CDC in the US.50 A major benefit of rapid testing is that it provides immediate feedback to patients, who can then be counselled about treatment and prevention. This is an important advantage because many people do not return to get their test results when other tests are used.50–52 Currently, rapid HIV tests are not approved by the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) in Australia for use in HIV screening, except in very limited urgent situations or specific settings—for example, in remote settings where laboratory resources are limited.53 The recently released national HIV strategy gives priority to assessing rapid HIV testing.54 In New Zealand, rapid HIV testing has been offered by the New Zealand AIDS Foundation and other community sexual health clinics since 2006.55

BOX 14-3 HIV antibody screening tests

Standard tests

• Used by laboratories performing diagnostic or screening testing to identify the HIV-negative antibody status of samples using screening or standard assays.

• Any test may be used for screening purposes provided it is evaluated to the appropriate level and shown to be appropriately sensitive and specific.

• Those samples yielding non-reactive results do not need to be further tested unless clinical considerations demand it.

• Reactive samples must be subjected to supplemental testing to distinguish true reactivity from false reactivity.

• The reference testing must confirm the presence of specific antibody or virus before the result is accepted as a true positive.

Reference tests

• Reference tests are used by laboratories to conduct confirmatory or additional special testing.

• This testing is conducted to confirm true positive status by distinguishing true from false reactivity.

• Usually this testing is conducted within a diagnostic strategy and a western blot is used; however, other reference testing situations occur (e.g. in a setting of possible seroconversion illness) when the first-used reference tests may include nucleic acid tests for proviral DNA.

• Laboratories may also use rapid tests for reference testing in appropriate settings.

• Other reference tests may be used once the HIV status is confirmed to quantify viral load, characterise the virus or identify the sensitivity of the virus to antiretroviral drugs.

• These tests may be conducted outside reference laboratories as long as any conditions of the TGA for the test kit registration are met.

Key points for short-incubation (rapid) tests for HIV

• The published sensitivities and specificities of the short-incubation tests now approach those of the standard enzyme immunoassays in positive and negative samples.

• The negative predictive value of short-incubation tests is such that infection can be confidently excluded if the test is negative. However, these tests are more likely to miss seroconversion because they are less able to detect low levels of antibody.

• Confirmatory testing, to distinguish false from true positive results, must be performed on each reactive sample.

• The limitations in the uses of short-incubation tests deserve consideration within the Australian context.

• The use of short-incubation tests should be limited to situations where:

• The availability and use of short-incubation tests in clinical settings is supported:

DNA, deoxyribonucleic acid; NATA, National Association of Testing Authorities; RCPA, Royal College of Pathologists of Australasia; TGA, Therapeutic Goods Administration.

Source: Department of Health and Ageing. National HIV testing policy, 2006. Available at www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/ohp-bbvs-hiv-testing-policy.

Laboratory studies in HIV infection

The progression of HIV infection is monitored by two important laboratory assessments: CD4+ T cell counts and viral load. CD4+ T cell counts provide a marker for immune function. As the disease progresses, there is usually a decrease in the number of CD4+ T cells (see Fig 14-1). CD4+ counts of 800–1200 cells/μL are generally considered normal. Laboratory tests that measure viral activity provide an assessment of disease progression: the lower the viral load, the less active the disease. In HIV, viral loads are reported as real numbers (i.e. 1260 copies/μL) or as undetectable. ‘Undetectable’ indicates that the viral load is lower than the test is able to report; ‘undetectable’ does not mean that the virus has been eliminated from the body or that the individual can no longer transmit HIV to others. The combination of these tests provides information that helps determine when to initiate therapy, the efficacy of therapy and whether clinical goals are being met.47

Abnormal blood tests are common in HIV infection and may be caused by HIV, opportunistic diseases or complications of therapy. Decreased white blood cell (WBC) counts, especially low neutrophil counts (neutropenia), are often seen; low platelet counts (thrombocytopenia) may be caused by HIV, antiplatelet antibodies or drug therapy; and anaemia is associated with the chronic disease process as well as with adverse effects of some ART. Altered liver function, caused by HIV disease, drug therapy or co-infection with a hepatitis virus, is common. Early identification of co-infection with hepatitis B virus (HBV) and/or hepatitis C virus (HCV) is extremely important because these infections have a more serious course in patients with HIV, may ultimately limit options for ART and can cause liver-related morbidity and mortality.47,52

Two types of resistance tests can determine whether a patient’s HIV is resistant to drugs used in ART. The genotype assay detects drug-resistant viral mutations that are present in reverse transcriptase and protease genes. The phenotype assay measures the growth of the virus in various concentrations of antiretroviral drugs (much like bacteria–antibiotic sensitivity tests). These assays are especially useful in making decisions about new drug combinations in patients who do not respond to therapy.47

MULTIDISCIPLINARY CARE

Collaborative management of the HIV-infected patient focuses on: (1) monitoring HIV disease progression and immune function; (2) initiating and monitoring ART; (3) preventing the development of opportunistic diseases; (4) detecting and treating opportunistic diseases; (5) managing symptoms; (6) preventing or decreasing complications of treatment; and (7) preventing further transmission of HIV. Ongoing assessment, clinician–patient interactions, and patient education and support are required to accomplish these objectives.45,47,48,52 The initial visit provides an opportunity to gather baseline data and to start establishing rapport. A complete history and physical examination, including an immunisation history and psychosocial and dietary evaluations, should be conducted. Findings from the history, assessment and laboratory tests help determine patient needs. Patient education about the spectrum of HIV disease, treatment, preventing transmission to others, improving health and family planning can be initiated at this meeting. Patient input should be used to develop a plan of care, and necessary referrals can be made. Remember that a newly diagnosed patient may be in a state of shock or denial and unable to retain or understand information. The nurse should be prepared to repeat and clarify information over the course of several months.52

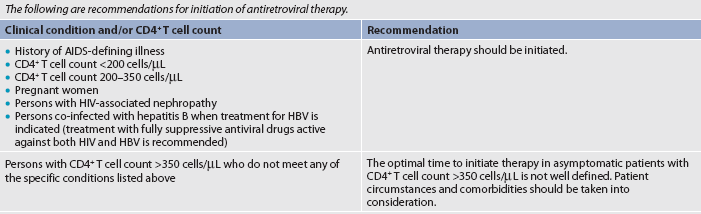

Drug therapy for HIV infection

The goals of drug therapy in HIV infection are to: (1) decrease the viral load; (2) maintain or raise CD4+ T cell counts; and (3) delay the development of HIV-related symptoms and opportunistic diseases. Recommendations for starting therapy in the chronically infected patient are summarised in Table 14-10.

TABLE 14-10 Antiretroviral therapy for chronically infected HIV patients DRUG THERAPY

HBV, hepatitis B viral infection.

Source: Adapted from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in HIV-1-infected adults and adolescents, 2011. Available at http://aidsinfo.nih.gov/Guidelines/GuidelineDetail.aspx?GuidelineiD=7.

Treatment guidelines incorporate the use of the following principles:

1. Treatment decisions should be individualised by risk of disease progression as indicated by higher viral loads and lower CD4+ T cell counts and by the patient’s desires for therapy.

2. Combination ART suppresses HIV replication and limits the potential for antiretroviral resistance, which is the major factor limiting treatment effect. The most effective means to suppress HIV replication is simultaneous initiation of at least three effective antiretroviral drugs from at least two different drug classes used in optimum schedules and full dosages.

3. Women should receive optimal ART regardless of pregnancy status.

4. Despite evidence that the risk of HIV transmission decreases with lower viral loads,48 all HIV-infected persons are potentially infectious regardless of viral load level and should avoid behaviours associated with the transmission of HIV and other infections.47

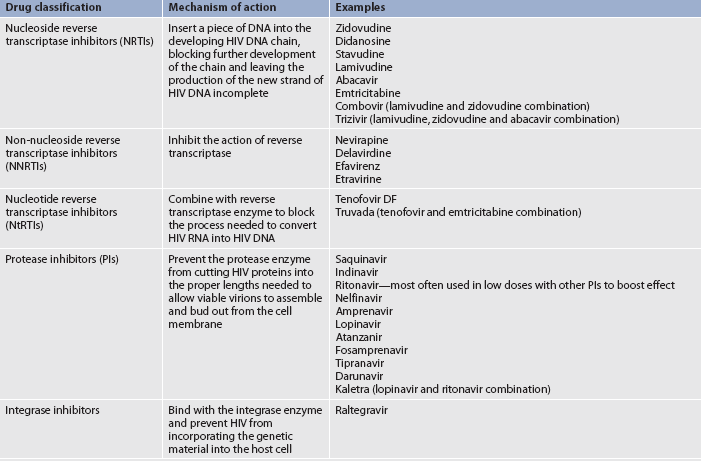

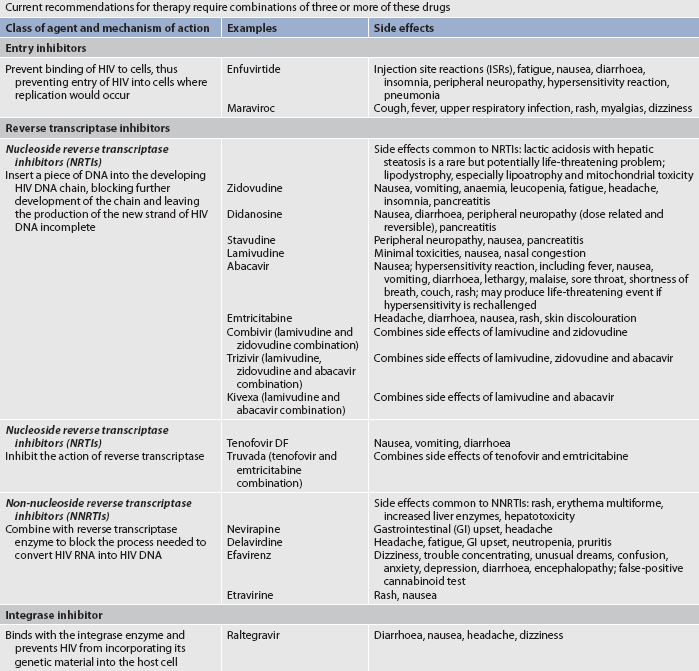

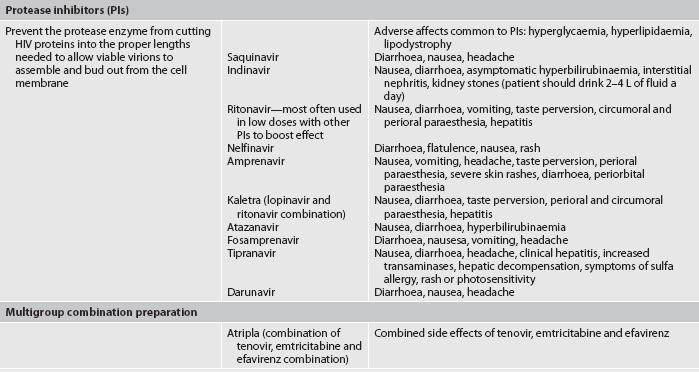

HIV cannot be cured, but ART can decrease viral replication and delay progression of the disease in most patients. When taken consistently and correctly, ART can reduce viral loads by 90–99%, which makes adherence to treatment regimens extremely important.47,56 Drugs used to treat HIV work at various points in the HIV replication cycle (see Table 14-11). The major advantage of using drugs from different drug groups is that combination therapy can attack viral replication in several different ways, making it more difficult for the virus to recover and decreasing the likelihood of drug resistance. An additional advantage is that alternatives exist for those patients who do not (or who no longer) respond to a specific drug regimen.47,56 A major problem with most drugs used in ART is that resistance develops rapidly when they are used alone (monotherapy) or taken in inadequate doses. For this reason, combinations of three or more antiretroviral drugs, prescribed at full strength, should be used. Many antiretroviral drugs can cause dangerous and potentially lethal interactions with other commonly used drugs, including over-the-counter drugs and herbal therapies.47,56 For example, St John’s wort, commonly used to alleviate depression, can interfere with ART.57 In fact, all herbal products should be used with caution by people with HIV infection.58

Drug therapy for opportunistic diseases

Management of HIV is complicated by the many opportunistic diseases that can develop as the immune system deteriorates (see Table 14-9). A preferred approach to opportunistic diseases is to prevent their occurrence. A number of opportunistic diseases associated with HIV can be delayed or prevented through the use of adequate ART, vaccines (including HBV, influenza and pneumococcal) and disease-specific prevention measures. Although it is not usually possible to eradicate opportunistic diseases once they occur, treatments that can control them are available. Advances in the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of opportunistic diseases have contributed significantly to increased life expectancy.45 Drug therapy for opportunistic infections is presented in Table 14-12.

TABLE 14-12 Drug therapy side effects of antiretroviral agents used in HIV infection*

* Many of these drugs cause serious and potentially fatal interactions when used in combination with other commonly used drugs, some of which are available over the counter.

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in HIV-1-infected adults and adolescents, 2008. Available at aidsinfo.nih.gov. Wolbach J, Davis, A, Johnson SC et al. A pharmacist’s guide to antiretroviral medications for HIV-infected adults and adolescents. Denver, Co: Mountain Plains AIDs Education and Training Center; 2009. Available at www.mpaetc.org.

Biochemical disease prevention strategies

Despite considerable research, biochemical means of preventing HIV are still not available. Research on methods such as vaginal or rectal microbicides, pre-exposure prophylaxis and a vaccine are ongoing.59–62 The problems that impede HIV vaccine development are numerous. HIV lives inside cells, where it can ‘hide’ from circulating immune factors. HIV also mutates rapidly, so that infected individuals develop HIV variants that may not all respond to a simple vaccine. In addition, two strains of HIV (HIV-1 and HIV-2) cause AIDS and at least nine clades (subtypes) of HIV-1 exist around the world. An effective biochemical method to prevent clade B (the predominant group in Western countries) may not be effective in developing countries, where the need is even greater.59–62

There are also social, ethical and economic issues related to vaccination and microbicide development. Efficacy will eventually have to be established in human testing. How will volunteers be recruited? How will true protection be determined? Will volunteers be exposed to HIV after use of a new biochemical method, thus risking infection? Because HIV is a global problem, with developing countries bearing the brunt of the epidemic, there is also concern about developing a vaccine or microbicide that can be widely distributed in a short amount of time at an acceptable cost. Will vaccines or microbicides, once developed, be accepted? Will they be available to those who need them?60 Despite the difficult nature of these issues, considerable research is in progress. Effective biochemical prevention measures would be extremely helpful in controlling the epidemic but would not replace current prevention methods because no biochemical method is likely to be 100% effective.62

NURSING MANAGEMENT: HIV INFECTION

NURSING MANAGEMENT: HIV INFECTION

Nursing assessment

Nursing assessment

Nursing assessment for individuals not known to be infected with HIV should focus on behaviours that could put the person at risk of HIV infection and other STIs and blood-borne diseases. All patients should be assessed for risky behaviours on a regular basis. The assumption should not be made that someone is without risk because he is too old or too young or because she is married or sings in the church choir. Nurses can help individuals assess risks by asking four basic questions:

1. Have you ever had a blood transfusion or used clotting factors? If so, was it before 1985?

2. Have you ever shared drug-using equipment with another person?

3. Have you ever had a sexual experience in which your penis, vagina, rectum or mouth came into contact with another person’s penis, vagina, rectum or mouth?

These questions provide the minimum data needed to initiate a risk assessment. A positive response to any of these questions requires an in-depth exploration of issues related to the identified risk.63,64

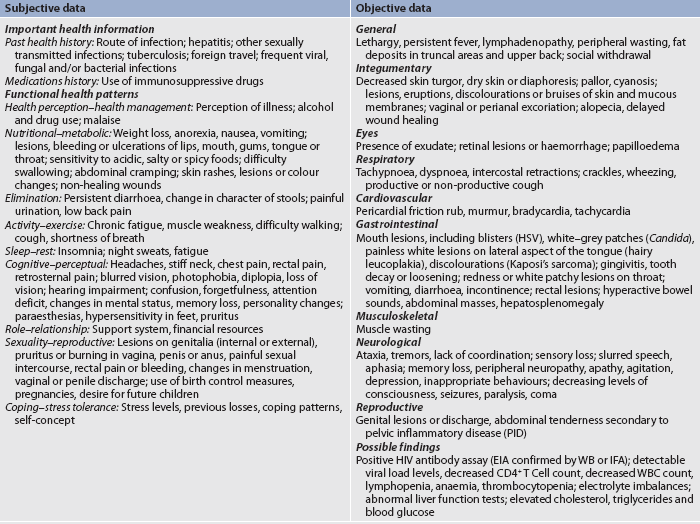

Specific assessments are needed when an individual has been diagnosed with HIV infection. Subjective and objective data that should be obtained are presented in Table 14-13. Repeated nursing assessments over time are essential because people’s circumstances change. Early recognition and treatment of problems can decrease the progression of HIV infection and prevent new infections. A complete history and thorough systems review can help the nurse to identify and address problems in a timely manner.

Nursing diagnoses

Nursing diagnoses

Nursing diagnoses related to HIV infection are dictated by several variables: the stage (e.g. uninfected, newly diagnosed, chronically infected); the presence of specific aetiological problems (e.g. respiratory distress, depression, pain); and psychosocial factors (e.g. issues related to self-esteem, sexuality, family interactions, finances). Because HIV infection is a complex and individually experienced disease, a broad spectrum of nursing diagnoses may include, but are not limited to, those presented in Box 14-4.

Planning

Planning

Prevention of HIV infection presents a number of challenges for the patient, many of which are related to the difficulties of behaviour change. Nurses can be instrumental in this process. Nursing interventions to prevent disease transmission depend on assessment of the patient’s individual risk behaviours, knowledge and skills. Nursing interventions based on these assessments can encourage the patient to adopt safer, healthier and less risky behaviours.48

Individual versus public health protection

CLINICAL PRACTICE

Situation

A nurse in a community clinic was having a follow-up visit with Virginia, a 38-year-old woman who tested positive for HIV during a health check-up 2 weeks ago. During the visit, Virginia disclosed that she has been verbally and physically abused by her partner. She also indicated that she had not told her partner about her positive HIV test because she is afraid that he will hurt her. She has not used any protection during sex with him since she learned of her test results because she suspects he infected her.

Important points for consideration

• A conflict exists for the nurse between preventing further harm to Virginia (possible increase in intimate partner violence), providing care to her partner (his need for an HIV test, diagnosis and treatment) and protecting public health (potential spread of HIV infection to her partner). Patient teaching and support are paramount because the nurse’s primary obligation is to the patient.

• HIV is a reportable communicable disease. Reporting should have been done when the test came back positive. The nurse needs to determine whether this was explained to Virginia, and whether Virginia provided her partner’s name and contact information to the reporting individual.

• If she did disclose his name and contact information, Virginia’s partner will have been contacted according to the relevant principles and legislation within the particular jurisdiction. While Virginia’s name would not be used in this communication, he may be able to guess that she has HIV.

Critical thinking questions

1. Within the parameters of legal requirements for reportable conditions, how can the nurse protect the patient’s confidentiality to prevent further intimate partner violence?

2. Since it is unclear whether Virginia acquired the HIV infection from her partner, how can the nurse protect the partner from possible infection while also attempting to protect Virginia from further violence?

3. How can the nurse address the issues of intimate partner violence? What resources would Virginia have in your community?

4. Discuss the benefits of universal, voluntary testing in the light of Virginia’s case.

Infection with HIV affects the entire range of a person’s life from physical health to social, emotional, economic and spiritual wellbeing. Once infection has occurred, no known treatment can eliminate HIV from the body. Therefore, the overriding goals of therapy are to keep the viral load as low as possible for as long as possible, maintain or restore a functioning immune system, improve the patient’s quality of life, prevent opportunistic disease, reduce HIV-related disability and death and prevent new infections.

Nursing interventions can assist the patient to:

2. promote a healthy lifestyle that includes avoiding exposure to additional STIs and blood-borne diseases

4. maintain or develop healthy and supportive relationships

5. maintain activities and productivity

7. come to terms with issues related to disease, disability and death

8. cope with the frequent symptoms caused by HIV and its treatments.60,65–70

Care plans are individualised and change as new treatment protocols develop and/or as HIV disease progresses.

Prevention and early detection of HIV

HEALTH PROMOTION

• Increase safe sexual practices, including condom use.

• Decrease equipment sharing among intravenous drug users.

• Increase clinician skills to assess for risk factors of HIV infection, to recommend HIV testing and to provide counselling for behaviour change.

• Make voluntary HIV testing a routine part of healthcare.

• Increase access to HIV testing facilities in traditional healthcare settings as well as in alternative sites, such as drug and alcohol treatment facilities and community-based organisations.

• Increase access to new HIV testing technologies, especially rapid testing.

• Increase risk assessment and individualised behaviour change messages to people with HIV to prevent new infections.

• Further decrease perinatal HIV infection by including voluntary HIV testing as a part of routine prenatal care and discussion of appropriate HIV therapy for those found to be infected.

Nursing implementation

Nursing implementation

The complexity of HIV disease is related to its chronic nature. As with most chronic and infectious diseases, primary prevention and health promotion are the most effective healthcare strategies. When prevention fails, disease results. HIV has no cure, continues for life, causes increasing physical disability, contributes to impaired health and ultimately leads to death.

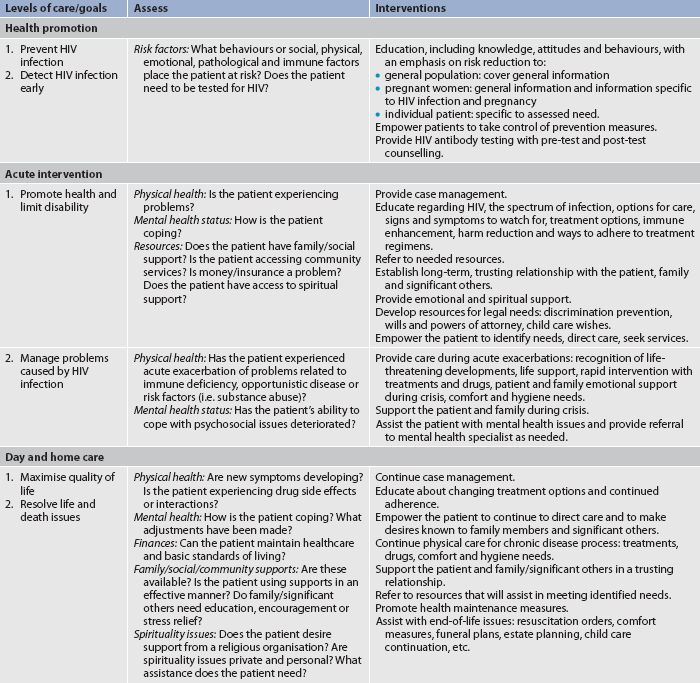

Nursing interventions at every stage of HIV disease can be instrumental in improving the quality and quantity of the patient’s life. Nurses who emphasise a holistic and individualised approach to care are well suited to provide optimal care to these patients. Table 14-14 presents a synopsis of nursing goals, assessments and interventions at each stage of HIV infection.

Health promotion

Health promotion

A major goal of health promotion is to prevent disease. Even with recent successes in the treatment of HIV, prevention is crucial for control of the epidemic. In addition, health promotion encourages early detection of disease so that, if primary prevention has failed, early intervention can be implemented.48,50

Prevention of HIV infection

Prevention of HIV infection

HIV infection is preventable. Avoiding and/or modifying risky behaviours are the most effective prevention tools. All patients should be provided with education and behaviour change counselling that is specific to each patient’s need and is culturally sensitive, language appropriate and age specific. Nurses are excellent resources for this type of education, but they must be comfortable with and know how to talk about sensitive topics such as sexuality and drug use.63

Remember that a range of activities can reduce the risk of HIV infection and that individuals will choose methods that best fit their life circumstances. The goal is for the person to develop safer, healthier and less risky behaviours. These techniques can be divided into safe activities (those that eliminate risk) and risk-reducing activities (those that decrease risk but do not eliminate it). The more consistently and correctly that prevention methods are used, the more effective they are in preventing HIV infection.60

Decreasing risks related to sexual intercourse

Decreasing risks related to sexual intercourse

Safe sexual activities eliminate the risk of exposure to HIV in semen and vaginal secretions. Abstaining from all sexual activity is the most effective way to accomplish this goal, but there are safe options for those who cannot or do not wish to abstain. Limiting sexual activities so that the mouth, penis, vagina or rectum does not contact a partner’s mouth, penis, vagina or rectum is safe because there is no contact with blood, semen or vaginal secretions. Safe activities include massage, masturbation, mutual masturbation (‘hand job’) and other activities that meet the ‘no contact’ requirements. Insertive sex between partners who are not infected or not at risk of becoming infected with HIV is also considered safe.

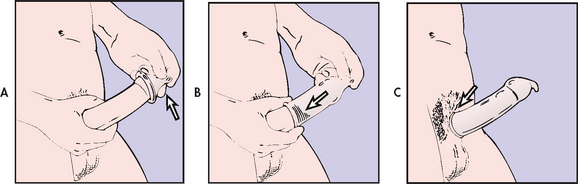

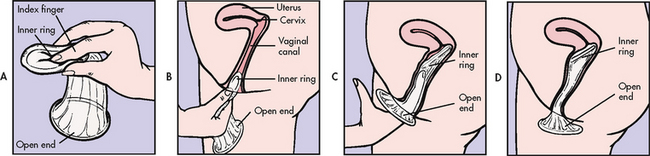

Risk-reducing sexual activities decrease the risk of contact with HIV through the use of barriers. Barriers should be used when engaging in insertive sexual activity (oral, vaginal or anal) with a partner whose HIV status is not known or with a partner who is known to have HIV. The most commonly used barrier is the male condom. The efficacy (protection provided under ideal circumstances) of male condoms is essentially 100%; their effectiveness (protection provided in actual or ‘real-life’ circumstances) is 80–90%. Correct use of male condoms increases effectiveness. The proper use and placement of the male condom is presented in Box 14-5. Female condoms provide an excellent alternative to male condoms. Female condom efficacy is also close to 100% and effectiveness is 94–97% against HIV and STI transmission. Use can be complicated, so careful instruction and practice are required. The proper use and placement of the female condom is presented in Box 14-6. In addition, squares of latex (known as dental dams) or plastic food wrap can be used to cover the external female genitalia during oral sexual activity.

BOX 14-5 Proper use and placement of male condom

PATIENT & FAMILY TEACHING GUIDE

Include the following instructions when teaching a patient about the use of a male condom.

1. Use only condoms that are made with latex or polyurethane. ‘Natural skin’ condoms have pores that HIV can penetrate.

2. Store condoms in a cool, dry place and protect them from trauma. The friction caused by carrying them in a back pocket, for instance, can damage the latex.

3. Do not use a condom if the expiration date has passed or the package looks worn or punctured.

4. Lubricants used in conjunction with condoms must be water soluble. Oil-based lubricants can weaken latex and increase the risk of tearing or breaking.

5. Non-lubricated, flavoured or unflavoured condoms can provide protection during oral intercourse.

6. The condom must be placed on the erect penis before any contact is made with the partner’s mouth, vagina or rectum to prevent exposure to pre-ejaculatory secretions that may contain HIV.

7. See the figure below for proper steps in male condom placement.

Proper placement of the male condom. A, The condom is placed over the glans of the erect penis, being careful to squeeze air out of the reservoir (tip). B and C, The condom is then rolled down the shaft of the penis to the hairline.

8. Remove the penis and condom from the partner’s body immediately after ejaculation and before the erection is lost to keep semen from leaking around the condom as the penis becomes flaccid. Hold the condom at the base of the penis and remove both from the partner’s body at the same time.

9. Wrap used condoms in tissue and discard. Do not dispose in the toilet, since this can cause plumbing problems.

10. Condoms are not reusable! A new condom must be used for every act of intercourse.

BOX 14-6 Proper use and placement of female condom

PATIENT & FAMILY TEACHING GUIDE

Include the following instructions when teaching a patient about the use of a female condom.

1. Female condoms consist of a polyurethane sheath with two spring-form rings.

2. Use only water-soluble lubricants with female condoms.

3. Some men have reported that the female condom feels better than the male condom. Other men like male condoms better. The only way to find out which type of condom works best is to try them both.

4. Practise inserting the female condom. The steps for proper insertion are shown in the figure below. Lubrication makes the condom slippery, but do not get discouraged—just keep trying.

Proper placement of the female condom. A, Inner ring is squeezed for insertion. B, Sheath is inserted similarly to a diaphragm. C, Inner ring is pushed up as far as it can go with the index finger. D, Proper placement of female condom.

5. During sexual intercourse, ensure that the penis is inserted into the female condom through the outer ring. It is possible for the penis to miss the opening, thus making contact with the vaginal or rectal mucosa and defeating the purpose of the condom.

6. Do not use a male condom at the same time as a female condom.

7. After intercourse, remove the condom before standing up. Twist the outer ring to keep the semen inside, gently pull the condom out of the vagina or rectum and discard.

8. Do not dispose in the toilet, since this can cause plumbing problems.

Decreasing risks related to drug use

Decreasing risks related to drug use

Drug use, including alcohol, is harmful. It can cause immune suppression and malnutrition, as well as a host of psychosocial problems. However, drug use in and of itself does not cause HIV infection. The major risk of HIV infection is related to sharing equipment and/or having unsafe sexual experiences while under the influence of drugs. Basic risk reduction rules are: (1) do not use drugs; (2) if you use drugs, do not share equipment; and (3) do not have sexual intercourse when under the influence of any drug (including alcohol) that impairs decision-making ability.33,38

The safest mechanism is to abstain from drugs. Although this is the best option for those who do not currently use drugs, it may not be a viable option for users who are not prepared to quit or for those who have no access to drug treatment services. The risk of HIV for these individuals can be eliminated if they do not share equipment. Injecting equipment (works) includes needles, syringes, cookers (spoons or bottle caps used to mix the drug), cotton and rinse water. Equipment used to snort (straws) or smoke (pipes) drugs can also be contaminated with blood. None of this equipment should be shared. Access to sterile equipment is an important risk elimination tactic. Some communities have needle and syringe exchange programs that provide sterile equipment to users in exchange for used equipment. Opposition to these programs is supported by the fear that ready access to injecting supplies will increase drug use. However, studies have shown that in communities where exchange programs have been established, drug use does not increase, rates of HIV and other blood-borne infections are controlled and an overall cost-benefit results.71 Cleaning equipment before use is a risk-reducing activity. It decreases the risk for those who share equipment, but cleaning requires equipment, takes time and may be difficult for a person in drug withdrawal. The proper use of drug equipment is presented in Box 14-7.

BOX 14-7 Proper use of drug-using equipment

PATIENT & FAMILY TEACHING GUIDE

Include the following instructions when teaching a patient to safely use drug-using equipment.

1. When injecting drugs, it is always preferable to use new, sterile syringes, needles, cookers and cotton (works). When snorting or smoking drugs, it is important to use clean pipes and straws.

2. Find out whether there is a needle and syringe exchange program in your community. If there is, take used equipment in and you will be provided with new works.

3. In many areas, sterile equipment can be purchased without a prescription.

4. Reusing your own equipment is acceptable. Just ensure that no one else uses your equipment and be sure it is clean to decrease the risk of abscesses.

5. If you must share injecting equipment, it is very important to clean the works thoroughly before use.

6. If you must share pipes or straws, it is very important to clean them thoroughly before use. Soak in bleach and rinse with water.

Decreasing risks of perinatal transmission

Decreasing risks of perinatal transmission

The best way to prevent HIV infection in infants is to prevent HIV infection in women. Women who are already infected with HIV should be asked about their reproductive desires. Those who choose not to have children need to have family planning methods discussed in detail. Should they become pregnant, abortion may be desired and should be discussed in conjunction with other options.41

If HIV-infected pregnant women are appropriately treated during pregnancy, the rate of perinatal transmission can be decreased from 25% to less than 2%. ART has significantly decreased the risk for infants born to HIV-infected women and more of these women are now considering becoming mothers. The current standard of care is that all women who are pregnant or contemplating pregnancy should be counselled about HIV infection, informed of their choices, routinely offered access to voluntary HIV antibody testing and, if infected, offered optimal ART.41,48,50,72

Decreasing risks at work

Decreasing risks at work

The risk of infection from occupational exposure to HIV is small but real. The National Health and Medical Research Council in Australia and Standards New Zealand have published guidelines to protect workers from exposure to blood and other potentially infectious materials.18,20 Precautions and safety devices decrease the risk of direct contact with blood and body fluids. Should exposure to HIV-infected fluids occur, postexposure prophylaxis (PEP) with combination ART, based on the type of exposure, the volume of the exposure and the status of the source patient, can significantly decrease the risk of infection. The possibility of treatment makes reporting of all blood exposures even more critical.40

HIV testing and pre-test and post-test discussion

HIV testing and pre-test and post-test discussion

People living with HIV who are not aware that they are infected are at greater risk of transmitting the infection to others. Because testing is the only sure way to determine if a person has HIV, any individual who is at risk of HIV should be encouraged to be tested. When negative, testing can relieve anxieties about past behaviours and provide opportunities for prevention education. When positive, testing provides the needed impetus to seek treatment and to protect sexual and drug-using partners. HIV testing should be accompanied by pre-test and post-test discussions. The goal is to normalise the test, decrease stigma related to HIV testing, find hidden cases, get infected individuals into care and prevent new cases of infection.50

Acute intervention

Acute intervention

Early intervention

Early intervention

Early intervention after detection of HIV infection can promote health and limit disability. Because the course of HIV is variable, assessment is very important. Nursing interventions are based on and tailored to patient needs that are noted during assessment. The nursing assessment in HIV disease should focus on early detection of symptoms, opportunistic diseases and psychosocial problems (see Tables 14-13 and 14-14).

Initial response to diagnosis of HIV

Initial response to diagnosis of HIV

Reactions to a positive HIV-antibody test are similar to the reactions of people who are diagnosed with any life-threatening, debilitating or chronic illness. They include anxiety, panic, fear, depression, denial, hopelessness, anger and guilt.50 Unfortunately, all of these emotions are overlaid with the stigma and discrimination that continue to pervade social reactions to HIV.73 Many of these reactions are also seen in the patient’s family members, friends and carers.74 As time passes, patients and their loved ones must confront common issues associated with any life-threatening illness. These include complex treatment decisions; feelings of loss, anger, powerlessness, depression and grief; social isolation imposed by self or others; altered concepts of the physical, social, emotional and creative self; thoughts of suicide; and the possibility of death.

Antiretroviral therapy

Antiretroviral therapy