Chapter 23 NURSING MANAGEMENT: integumentary problems

1. Outline health promotion practices related to the integumentary system.

2. Explain the aetiology, clinical manifestations, and nursing and multidisciplinary care of common acute dermatological problems.

3. Outline the psychological and pathophysiological effects of chronic dermatological conditions.

4. Explain the aetiology, clinical manifestations and multidisciplinary care of malignant dermatological disorders.

5. Explain the aetiology, clinical manifestations and multidisciplinary care of bacterial, viral and fungal infections of the integument.

6. Explain the aetiology, clinical manifestations and multidisciplinary care of infestations and insect bites.

7. Explain the aetiology, clinical manifestations and multidisciplinary care of dermatological disorders related to allergies.

8. Explain the aetiology, clinical manifestations and multidisciplinary care related to benign dermatological disorders.

9. Describe the dermatological manifestations of common systemic diseases.

10. Outline the nursing management related to plastic surgery and skin grafts.

Health promotion

Health promotion practices related to the skin often parallel practices appropriate for general good health. The skin reflects both physical and psychological wellbeing. Specific health promotion activities appropriate to good skin health include avoiding environmental hazards, ensuring adequate rest and exercise, following proper hygiene and nutrition, and cautious use of self-treatment preparations.

ENVIRONMENTAL HAZARDS

Sun exposure

Many people are unaware that the effects of years of exposure to the sun are cumulative and damaging. The ultraviolet (UV) rays of the sun cause degenerative changes in the dermis, resulting in premature ageing (i.e. loss of elasticity, thinning, wrinkling, drying of the skin). Prolonged and repeated sun exposure is a major factor in precancerous and cancerous lesions.1 Australia has one of the highest incidences of skin cancer in the world.2 Actinic keratoses, basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma and malignant melanoma are dermatological problems associated directly or indirectly with sun exposure. These skin disorders are discussed in this chapter.

Nurses should be strong advocates of safe sun practices. Specific wavelengths of the sun (see Table 23-1) have different effects on the skin. Ultraviolet B (UVB) appears to be the major factor in the development of skin cancer, and ultraviolet A (UVA) augments the carcinogenic effects of UVB. Tanning is the skin’s response to injury by the sun and is caused by increased production of melanin. When sun exposure is excessive, the turnover time of the skin is shortened and results in peeling. Fair-skinned persons should be especially cautious about excessive sun exposure because they have smaller amounts of the natural protection afforded by melanin.

TABLE 23-1 Wavelengths of the sun and effects on skin

| Wavelength | Effect |

|---|---|

| Short (UvC) | Does not reach earth; blocked by the atmosphere |

| Middle (UvB) | Causes sunburn and cumulative effect of sun damage; major factor in the development of skin cancer |

| Long (Uva) | Can produce elastic tissue damage and actinic skin damage; contributes to the formation of skin cancer |

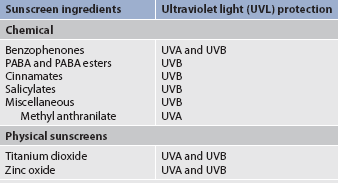

Sunscreens can filter UVA and UVB wavelengths. There are two types of topical sunscreen: chemical and physical. Chemical sunscreens are light creams or lotions designed to absorb or filter UV light, resulting in diminished UV light penetration into the epidermis. Physical sunscreens are thick, opaque, heavy creams that reflect UV radiation. They block UVA and UVB radiation, as well as all visible light.

Standards Australia has set standards for labelling sunscreen products according to their sun protection factor (SPF).3 This is a method of measuring the effectiveness of a sunscreen in filtering or reflecting UV radiation. Patients should be taught to look for the term ‘broad spectrum’ on packaging, indicating a wide range of absorbency, particularly for UVB wavelengths.

Consumers need to select the sunscreen that is most appropriate for their needs. Para-aminobenzoic acid (PABA) and PABA esters, cinnamates, salicylates and methyl anthranilate block UVB rays. PABA has been removed from many sunscreen products because it stains clothing and can cause allergic reactions, including contact dermatitis.4 The benzophenones block both UVA and UVB rays (see Table 23-2). Waterproof sunscreens should be used by swimmers and those who perspire profusely. Directions accompanying specific products should be followed because application time before exposure varies according to the product.

HEALTH DISPARITIES

• Indigenous Australians and Māori have lower incidences of skin cancer than non-Indigenous and non-Māori populations.

• Caucasians, especially those living in sunny climates, have a high incidence of skin cancer.

• Skin assessment may be difficult in individuals with darker skin. The oral mucous membranes and conjuctiva are areas where pallor, cyanosis and jaundice are more readily detected. The palms of the hands and soles of the feet can also be used for skin assessment in darker people.

• When darker skin heals following injury or inflammation, it tends to be hypopigmented or hyperpigmented.

The general recommendation is that everyone should use natural protection (clothing, hats, seeking shade) as a first approach to primary prevention of skin cancer. Sunscreens block out only a proportion of the wavelengths within the UV spectrum and have been recommended as an adjunct to natural protection.5 Sunscreens with an SPF of 30+ or more that comply with the current Australian and New Zealand standards are recommended when skin is exposed to the sunlight.

Nurses can also inform patients about other means of protection from the damaging effects of the sun, such as wearing a wide-brimmed hat, sunglasses and clothing with a UV protection factor above 40 or carrying an umbrella. Not all fabric blocks the harmful effects of the sun, particularly when the fabric is wet. Standards Australia/New Zealand have established labelling standards for clothing with an ultraviolet protective factor (UPF) from very low to high protection.6 Patients need to know that the sun’s rays are most dangerous between 10 am and 3 pm standard time or 11 am and 4 pm daylight saving time, regardless of the latitude. Even on overcast days, serious sunburn can occur because up to 80% of UV rays can penetrate through the clouds. Other factors that increase the possibility of sunburn include being at high altitudes, being in snow, which reflects 85% of the sun’s rays, or being in or near water. People should be warned of the dangers of tanning booths and sun lamps, which use predominantly UVA rays.7 No presently available sunscreen blocks all UVA.

Certain topical and systemic medications potentiate the effect of the sun, even with brief exposure. Categories of drug therapy that may contain common photosensitising medications are listed in Table 23-3. Nurses should be aware that many drugs are included in these categories and the photosensitivity of each individual drug should be examined. The chemicals in these medications absorb light and release energy that harms cells and tissues. The clinical manifestations of drug-induced photosensitivity are similar to those of exaggerated sunburn, with swelling, erythema, papular plaque-like lesions and vesicles. Skin that is at risk of photosensitivity reactions can be protected by the use of natural protection and sunscreen products. Nurses have a role in educating patients who are taking these drugs about their photosensitising effect.

Categories of drugs that may cause photosensitivity

| Categories | Examples |

|---|---|

| Anticancer drugs | Methotrexate, vinorelbine |

| Antidepressants | Amitriptyline, clomipramine, doxepin |

| Antiarrhythmics | Quinidine, amiodarone |

| Antihistamines | Diphenhydramine, chlorpheniramine |

| Antibacterials | Tetracycline, sulfamethoxazole, azithromycin, ciprofloxacin |

| Antifungals | Griseofulvin, ketoconazole |

| Antipsychotics | Chlorpromazine, haloperidol |

| Diuretics | Frusemide, hydrochlorothiazide |

| Hypoglycaemics | Glipizide |

| Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs | Diclofenac, piroxicam, sulindac |

Irritants and allergens

Patients may seek treatment for two types of contact dermatitis: irritant and allergic. Irritant contact dermatitis is produced by direct chemical injury to the skin, whereas allergic contact dermatitis is an agent-specific, type IV delayed hypersensitivity response. This response requires sensitisation and occurs only in individuals who are predisposed to react to a particular antigen (see Ch 13).

The nurse should counsel patients to avoid known irritants (e.g. ammonia, harsh detergents). Skin patch testing (application of allergens) is necessary to determine the most likely sensitising agent. Usually the nurse is the first healthcare provider to detect a contact allergy to various tapes, gloves (latex) and adhesives. The nurse must also be aware that prescribed and over-the-counter topical and systemic drugs used to treat a variety of conditions may cause dermatological reactions.8

Radiation

Although most radiology departments are extremely cautious in protecting both their staff and their patients from the effects of excessive radiation, the nurse should help the patient to make decisions about undergoing radiological procedures. X-rays can be invaluable in both diagnosis and therapy but indiscriminate use can cause serious side effects to the skin as well as other body processes. For example, 30 years ago cystic acne was treated with radiation. This information is important because patients who have been treated in the past by this method have an increased incidence of basal cell carcinoma.9 Skin reactions to radiation therapy are discussed in Chapter 15.

REST AND SLEEP

Rest and sleep are important health promotion practices in relation to the skin. Although the exact effects of sleep are not known, it is thought to be restorative. Rest increases the threshold of itching and so reduces the potential skin damage from the resultant scratching.

EXERCISE

Exercise increases circulation and dilates the blood vessels. In addition to the healthy glow produced by exercise, the psychological effects can also improve a person’s appearance and mental outlook. However, heat and perspiration caused by exercise may irritate skin conditions and increase itchiness. Caution must be used to avoid or protect the exerciser from overexposure to heat, cold and sun during outdoor exercise.

HYGIENE

Hygiene practices should match the skin type, lifestyle and culture of the patient. The person with oily skin should cleanse the skin with a drying agent more often than the person with dry skin. Dry skin might benefit from superfatted soaps and measures to increase moisture, such as the application of moisturisers to the skin.

The normal acidity of the skin (pH 4.2–5.6) and perspiration protect against bacterial overgrowth. Most soaps are alkaline and cause a neutralisation of the skin surface and loss of protection. The use of more neutral soaps, as well as avoiding hot water and vigorous rubbing, can noticeably decrease local irritation and inflammation.

In general, the skin and hair should be washed often enough to remove excess oil and excretions and to prevent odour. Older people should avoid the use of harsh soaps and shampoos because of the increasing dryness of their skin and scalp. Moisturisers should be used after bath or shower while the skin is still damp to seal in this moisture.

NUTRITION

A well-balanced diet adequate in all food groups can produce healthy skin, hair and nails. Certain elements are particularly essential to good skin health. These elements include the following:

1. Vitamin A—essential for the maintenance of normal cell structure, specifically epithelial cells. It is necessary for normal wound healing. The absence of vitamin A causes dryness of the conjunctiva and poor wound healing.

2. Vitamin B complex—essential for complex metabolic functions. Deficiencies of niacin and pyridoxine (B6) manifest as dermatological symptoms such as erythema, bullae and seborrhoea-like lesions.

3. Vitamin C (ascorbic acid)—essential for connective tissue formation and normal wound healing. Absence of vitamin C causes symptoms of scurvy, including petechiae, bleeding gums and purpura.

4. Vitamin K—deficiency interferes with normal prothrombin synthesis in the liver and can lead to bruising.

5. Protein—necessary in amounts adequate for cell growth and maintenance. It is also necessary for normal wound healing.

6. Unsaturated fatty acids—necessary to maintain the function and integrity of cellular and subcellular membranes in tissue metabolism, especially linoleic and arachidonic acids.

Obesity has an adverse effect on the skin. The increase in subcutaneous fat can lead to stretching and overheating. Overheating secondary to the greater insulation provided by fat causes an increase in sweating, which has an adverse effect on inflamed skin. Obesity also has an influence on the development of type 2 diabetes mellitus with its concomitant skin complications (see Ch 48).

SELF-TREATMENT

The nurse needs to increase patients’ awareness of the dangers of self-diagnosis and treatment. The wide variety of over-the-counter skin preparations can confuse consumers. General instructions that the nurse can discuss with patients should stress the duration of treatment and the need to follow package directions closely. Skin problems are generally slow to produce symptoms and slow to resolve. If the package insert of an over-the-counter drug says usage should not exceed 7 days, this warning should be heeded. If the directions say to apply twice daily, the urge to increase the dose and hasten the cure must be avoided. If any systemic signs of inflammation or extension of the skin problem (e.g. an increased number of lesions or increased erythema or swelling) develop, self-care should be stopped and the help of a professional should be enlisted.

MALIGNANT SKIN NEOPLASMS

Cancer of the skin is the most common cancer. Malignant neoplasms of the skin exhibit similar characteristics to other malignant conditions (see Ch 15). However, skin malignancies generally grow slowly. The presence of a persistent lesion that does not heal is highly suggestive of a malignancy and should be biopsied. Adequate and early treatment can often lead to a highly favourable prognosis.9 The fact that skin lesions are so visible increases the likelihood of early detection and diagnosis. Patients should be taught to self-examine their skin regularly.

Risk factors

Risk factors for skin malignancies include having a fair skin type (blonde or red hair and blue or green eyes), a history of sunburn and pattern of sun exposure, a family history of skin cancer and exposure to sun in childhood.5 Environmental factors that increase the risk of skin malignancies include living near the equator, working outdoors and frequent outdoor recreational activities. Dark-skinned people are less susceptible to skin cancer because of their naturally higher levels of melanin, an effective sunscreen. However, although having dark skin lowers the risk of melanoma, people with dark skin do develop melanoma.

Non-melanoma skin cancers

Non-melanoma skin cancers, either basal cell carcinoma (BCC) or squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), are the most common form of skin cancer.10 Globally, there are more than 1 million new cases every year.11 In Australia, about 434,000 cases of non-melanoma skin cancer (the most frequently occurring cancer in Australia, but the least life-threatening) are diagnosed each year.2 Non-melanoma skin cancers do not develop from melanocytes, the skin cells that make melanin, as melanoma skin cancers do. Instead, they are a neoplasm of the epidermis. The most common sites for the development of non-melanoma skin cancers are in sun-exposed areas and include the face, head, neck, back of the hands and arms.

Although the number of deaths attributable to non-melanoma skin cancers is small, the tumours have an inherent potential for severe local destruction, permanent disfigurement and disability. The most common aetiological factor, chronic sun exposure, should be consciously avoided through the use of protective clothing and sunscreens.12

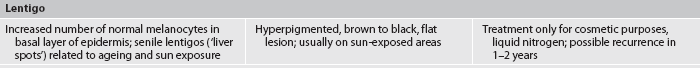

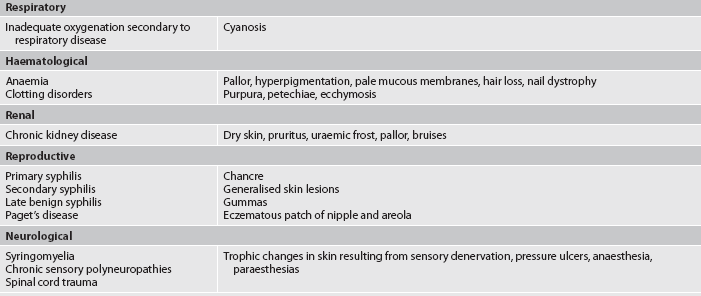

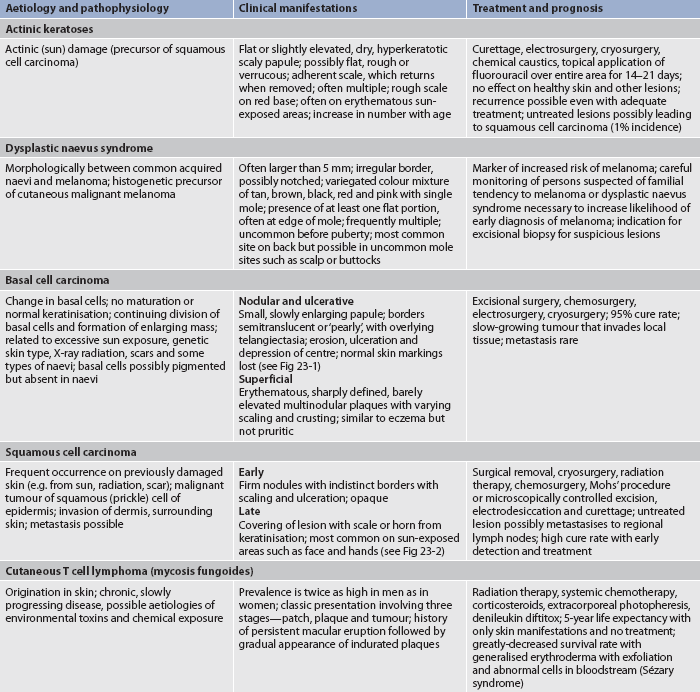

ACTINIC KERATOSIS

Actinic keratosis, also known as solar keratosis, consists of hyperkeratotic papules and plaques occurring on sun-exposed areas. Actinic keratosis is a premalignant form of squamous cell carcinoma that affects nearly all of the older Caucasian population. It is the most common of all precancerous skin lesions. The clinical appearance of actinic keratosis can be highly varied. The typical lesion is an irregularly shaped, flat, slightly erythematous macule or papule with indistinct borders and an overlying hard keratotic scale or horn (see Table 23-4). Many forms of treatment are used, including cryosurgery, fluorouracil, surgical removal, tretinoin and chemical peeling agents. Any lesion that persists should be evaluated for possible biopsy.

TABLE 23-4 Premalignant and malignant conditions of the skin

HIV, human immunodeficiency virus.

* Refer to Chapter 14 for more information.

BASAL CELL CARCINOMA

Basal cell carcinoma is a locally invasive malignancy arising from epidermal basal cells. It is the most common type of skin cancer and also the least deadly. BCC usually occurs in middle-aged to older adults. The clinical manifestations are described in Table 23-4. The cancerous cells of BCC almost never spread beyond the skin (see Fig 23-1). However, if left untreated, massive tissue destruction may result. Some BCCs are pigmented with curled borders and an opaque appearance and may be misinterpreted as melanomas. Therefore, a tissue biopsy is needed to confirm the diagnosis.

Multiple treatment modalities are used depending on the tumour location and histological type, history of recurrence and patient characteristics. Treatment modalities include electrodesiccation and curettage, excision, cryosurgery, radiation therapy, Mohs’ micrographic surgery, topical chemotherapy and intralesional α-interferon. (These treatments are discussed later in this chapter.) Electrodesiccation, curettage, cryosurgery and scalpel incision all have a cure rate of greater than 90% when used correctly on primary lesions.

SQUAMOUS CELL CARCINOMA

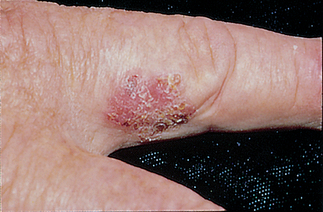

Squamous cell carcinoma is a malignant neoplasm of keratinising epidermal cells (see Fig 23-2). It frequently occurs on sun-exposed skin. SCC is less common than BCC, can be very aggressive, has the potential to metastasise and may lead to death if not treated early and correctly. Pipe, cigar and cigarette smoking contribute to the formation of SCC. Therefore, lesions are commonly seen on the mouth and lips.

The clinical manifestations of SCC are described in Table 23-4. A biopsy should always be performed when a lesion is suspected to be SCC. Treatment consists of electrodesiccation and curettage, excision, radiation therapy, intralesional injection of fluorouracil or methotrexate and Mohs’ surgery. There is a high cure rate with early detection and treatment.

Malignant melanoma

Malignant melanoma is a tumour arising in cells producing melanin, usually the melanocytes of the skin. Melanoma has the ability to metastasise to any organ, including the brain and heart. This is the most deadly skin cancer and its incidence is increasing faster than that of any other cancer. Currently it accounts for 11% of all skin cancers.11

About 1430 Australians10 die each year from melanoma. Melanoma is the fourth most common cancer diagnosed in New Zealand.13 The precise cause of melanoma is unknown but risk factors include: UV radiation; skin sensitivity; genetic, hormonal and immunological factors; and recreational lifestyle changes that lead to greater sun exposure. Genetic factors such as a prior diagnosis of melanoma and having a first-degree relative diagnosed with melanoma increase a person’s risk. A mutated gene has been identified in some families who have a high familial incidence of melanoma.14

TYPES OF MELANOMA

The four types of cutaneous melanoma are superficial spreading melanoma (SSM), lentigo maligna melanoma (LMM), acral-lentiginous melanoma (ALM) and nodular melanoma (NM).

• SSM is the most common type and the most curable, and often occurs on chronically sun-exposed areas, such as the legs and upper back. It frequently arises from a pre-existing mole.

• LMM is commonly located on the head and neck and is often found in older patients. Lesions appear as flat, brown, irregular patches. These patches increase in size for many years before the development of cancer occurs.

• ALM appears on the soles, palms, mucous membranes and terminal phalanges. ALM is more common in Asian people and people with dark skin.

• NM occurs more often in men and can be located anywhere on the body. It is the most frequently misdiagnosed melanoma because it resembles a blood blister or polyp. It is believed to be a more aggressive type of melanoma that can develop and invade rapidly.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

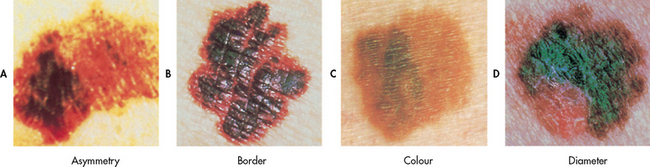

About one-third of melanomas occur in existing naevi or moles. Melanomas frequently occur on the lower legs in women and on the trunk, head and neck in men. Because most melanoma cells continue to produce melanin, melanoma tumours are often brown or black. Individuals should consult their healthcare provider immediately if their moles or lesions show any of the clinical signs (ABCDs) of melanoma (see Fig 23-3). Any sudden or progressive increase in the size, colour or shape of a mole should be checked. When melanoma begins in the skin it is called cutaneous melanoma. Melanoma can also occur in the eyes, meninges, lymph nodes, digestive tract and anywhere else in the body where melanocytes are found.

Figure 23-3 The ABCDs of melanoma. A, Asymmetry: one half unlike the other half. B, Border: irregular, scalloped or poorly circumscribed border. C, Colour: varied from one area to another; shades of tan and brown; black; sometimes white, red or blue; change in shape, size or colour of mole. D, Diameter: larger than 6 mm as a rule (diameter of a pencil).

MULTIDISCIPLINARY CARE

Treatment depends on the site of the original tumour, the stage of the cancer and the patient’s age and general health. The initial treatment of malignant melanoma is surgery. Melanoma that has spread to the lymph nodes or nearby sites usually requires additional therapy, such as chemotherapy, biological therapy (e.g. α-interferon, interleukin-2) and/or radiation therapy. The type of therapy depends on the stage of the disease. Examples of chemotherapy agents that are used include dacarbazine, temozolomide, procarbazine, carmustine and lomustine. Gene and vaccine therapies are currently being examined as additional treatment options.15 (See Ch 15 for a discussion of these therapies.) Topical immune therapy is being investigated in the treatment of LMM. Any pigmented lesions believed to be melanoma should never be shave-biopsied, shave-excised or electrocauterised.

The staging of melanoma (stages 0–IV) is based on tumour size, nodal involvement and the presence of metastasis. In stage 0, the melanoma is confined to one place (in situ) in the epidermis. Melanoma is nearly 100% curable by excision if diagnosed at stage 0. The 5-year survival rate (86–95%) in stage I can vary depending on sentinel node biopsy results, which indicate whether metastasis has occured.16 If spread to regional lymph nodes has occurred (stage III), the patient has a 45% chance of 5-year survival. If metastasis to other organs occurs (stage IV), treatment then becomes mostly palliative.

DYSPLASTIC NAEVUS SYNDROME

An abnormal mole pattern called dysplastic naevus syndrome (DNS) places a person at increased risk of melanoma. Approximately 2–8% of the white population have moles classified as dysplastic naevi. Dysplastic naevi (DN), or atypical moles, are moles that are larger than usual (>5 mm across) with irregular borders and various shades of colour. These naevi may have the same ABCD characteristics as melanoma, but they are less pronounced. The earliest clinically detectable abnormality associated with this syndrome is an increase in the number of morphologically normal-looking naevi at about age 2–6 years. Another proliferation occurs around adolescence and new naevi appear throughout life. Individuals with DN may have more than 110 normal-appearing naevi. Obtaining a detailed family history related to melanoma and DNS is an important responsibility of the healthcare provider. The risk of developing melanoma doubles with the presence of one dysplastic naevus, and having 10 or more increases the chance 12-fold.

Skin infections and infestations

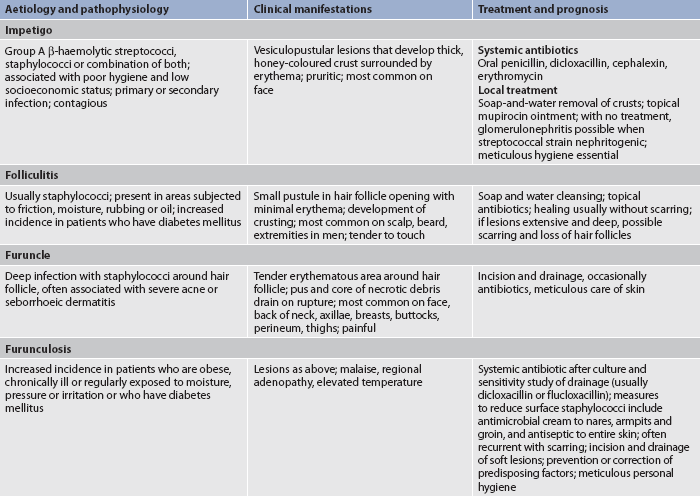

BACTERIAL INFECTIONS

The skin is covered with numerous microorganisms, especially bacteria. Staphylococcus epidermidis and mixed coliforms are the most common bacteria present on the skin. Staphylococcus aureus and group A β-haemolytic streptococci are the major types of bacteria responsible for primary and secondary skin infections. The skin provides an ideal environment for bacterial growth with an abundant supply of warmth, nutrients and water.

Bacterial infection occurs when the balance between the host and the microorganisms is altered. This can occur as a primary infection following a break in the skin. It can also occur as a secondary infection to already damaged skin or as a sign of a systemic disease (see Table 23-5). Healthy people can develop bacterial skin infections. Predisposing factors such as moisture, obesity, skin disease, use of systemic corticosteroids and antibiotics, chronic disease and diabetes mellitus all increase the likelihood of infection. Good hygiene practices and general good health inhibit bacterial infections. If an infection is present, the resulting drainage is infectious. Meticulous skin hygiene and infection control practices are necessary to prevent spread of the infection.

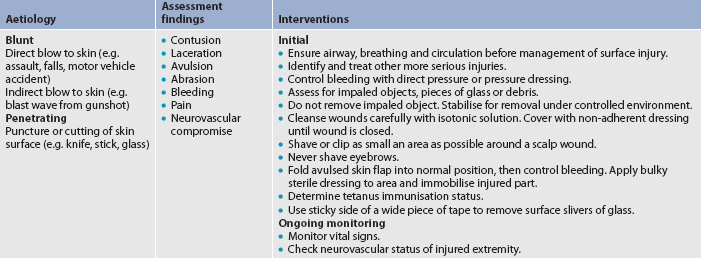

Trauma is a common predisposing factor to skin infection. Table 23-6 outlines the emergency care of a patient with a surface skin wound.

VIRAL INFECTIONS

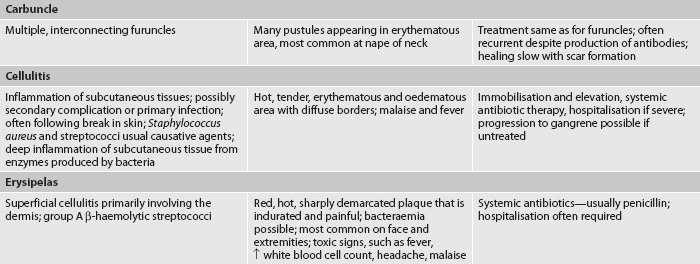

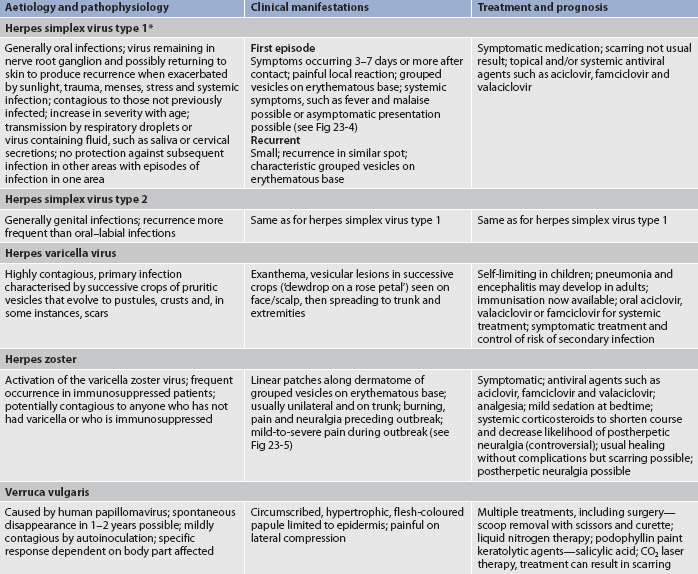

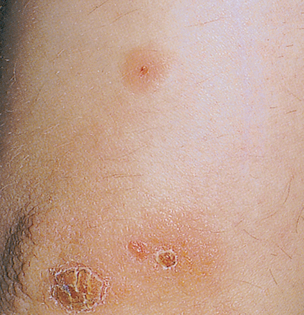

Viral infections of the skin are as difficult to treat as viral infections anywhere in the body. When a cell is infected by a virus, a lesion can result (see Fig 23-4). Lesions can also result from an inflammatory response to the viral infection. Herpes simplex, herpes zoster (see Fig 23-5) and warts are the most common viral infections affecting the skin (see Table 23-7).

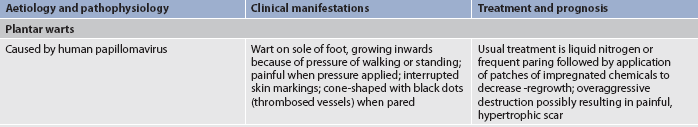

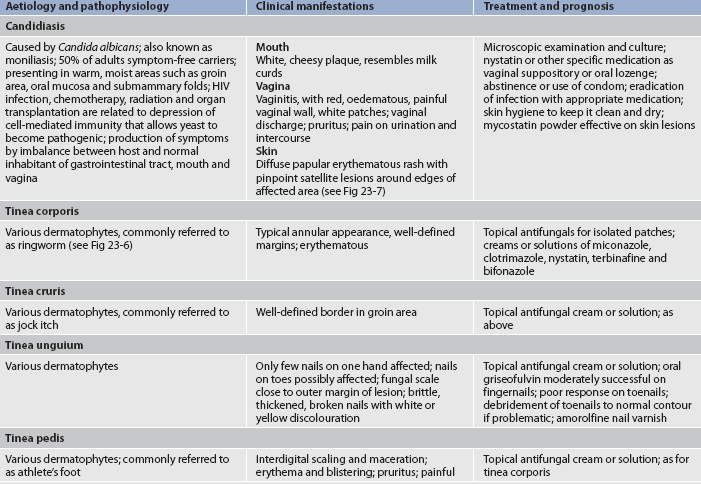

FUNGAL INFECTIONS

Because of the large number of identified fungi, it is almost impossible to avoid exposure to some pathological varieties. However, some fungi can cause serious infections, including tinea corporis and candidiasis (see Figs 23-6 and 23-7). Common fungal infections of the skin are presented in Table 23-8.

Figure 23-6 Tinea corporis (ringworm). Typical presentation with an advancing red scaly border. Designation of ‘ringworm’ is obvious.

Microscopic examination of the scraping of suspicious skin lesions in 10–20% potassium hydroxide is an easy, inexpensive diagnostic measure to determine the presence of fungus. The appearance of hyphae (thread-like structures) is indicative of a fungal infection.

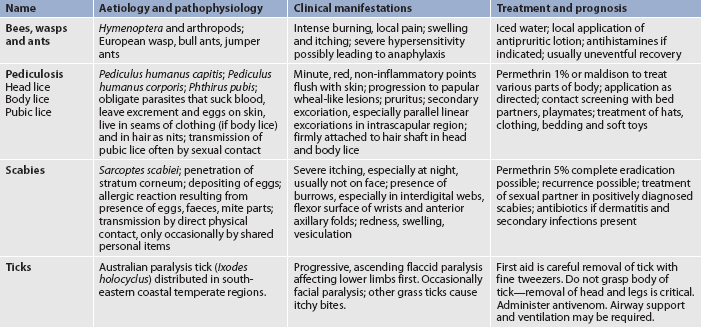

INFESTATIONS AND INSECT BITES

The possibilities for exposure to insect bites and infestations are numerous. In many instances, an allergy to the venom plays a major role in the reaction (see Fig 23-8). In other cases, the clinical manifestations are a reaction to the eggs, faeces or body parts of the invading organism. Certain persons react with a severe hypersensitivity (anaphylaxis), which can be life-threatening. (Anaphylaxis is discussed in Ch 13.). Prevention of insect bites by avoidance or by the use of repellents is somewhat effective.

In recent times there has been an increase in pediculosis (lice) and scabies. Meticulous hygiene related to personal articles, clothing and bedding, and examination and care of pets, as well as careful selection of sexual partners, can reduce the incidence of infestations. Routine inspection is necessary where there is a risk of tick bites (see Table 23-9).

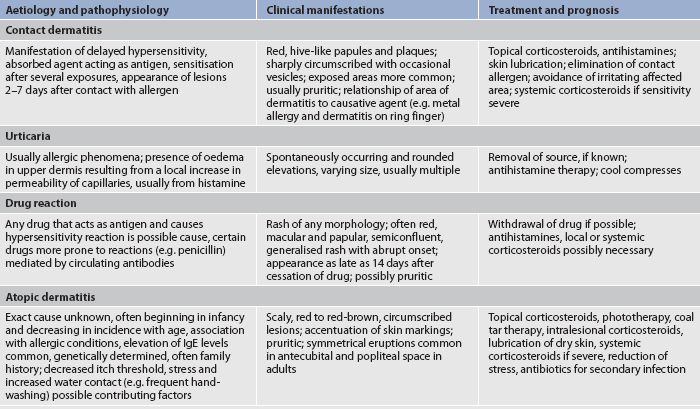

Allergic dermatological problems

Dermatological problems associated with allergies and hypersensitivity reactions may present a challenge to the clinician (see Table 23-10). The pathophysiology related to allergic and contact dermatitis is discussed in Chapter 13. A careful family history and discussion of exposure to possible offending agents provide valuable data. Patch testing involves the application of allergens to the patient’s skin (usually on the back) for 48 hours, after which the test sites are examined for erythema, papules, vesicles or all of these. Patch testing is used to determine possible causative agents. The best treatment of allergic dermatitis is avoidance of the causative agent. The extreme pruritus of contact dermatitis and its potential for chronicity make it a frustrating problem for the patient, nurse and dermatologist.

Can postherpetic neuralgia be prevented with oral aciclovir?

EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICE

Clinical question

In patients with herpes zoster (P), is oral aciclovir effective (I) versus placebo (C) in preventing postherpetic neuralgia (O) at 6 months after initial infection (T)?

Critical appraisal and synthesis of evidence

• Five RCTs evaluated oral aciclovir and one RCT evaluated oral famciclovir (n = 1211).

• Patients had varying degrees of herpes zoster severity. Antiviral agents were given within 72 hours after onset of herpes zoster rash.

• Presence of postherpetic neuralgia at site of shingles rash measured for 6 months.

• No significant difference between antiviral (either aciclovir or famciclovir) or placebo in preventing postherpetic neuralgia after rash onset.

Implications for nursing practice

• Assess the patient for several years after herpes zoster onset for continuing discomfort.

• Postherpetic neuralgia treatments may not be effective for many patients.

• Burning, incapacitating pain of acute herpes zoster and continuing postherpetic neuralgia may lead to altered mood, fatigue, insomnia and social isolation.

• Provide supportive counselling and referral for chronic neuralgia pain.

P, patient population of interest; I, intervention or area of interest; C, comparison of interest or comparison group; O, outcome(s) of interest; T, timing.

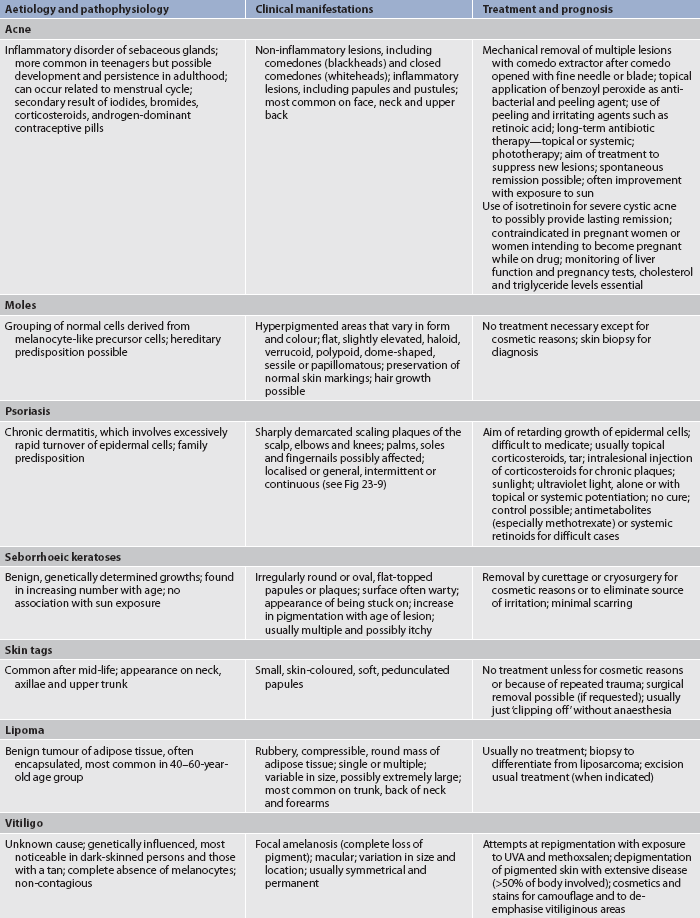

Benign dermatological problems

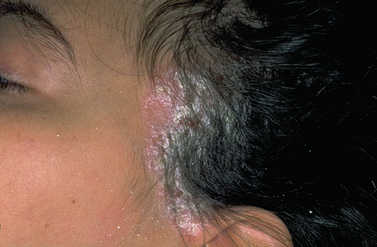

Although the list of benign dermatoses is extensive, some of the most commonly seen and distressing problems are summarised in Table 23-11. Psoriasis is one common benign disorder that may occur with skin irritation or injury (see Fig 23-9). The chronicity of psoriasis can be severe and disabling as people withdraw from social contact due to visible lesions.

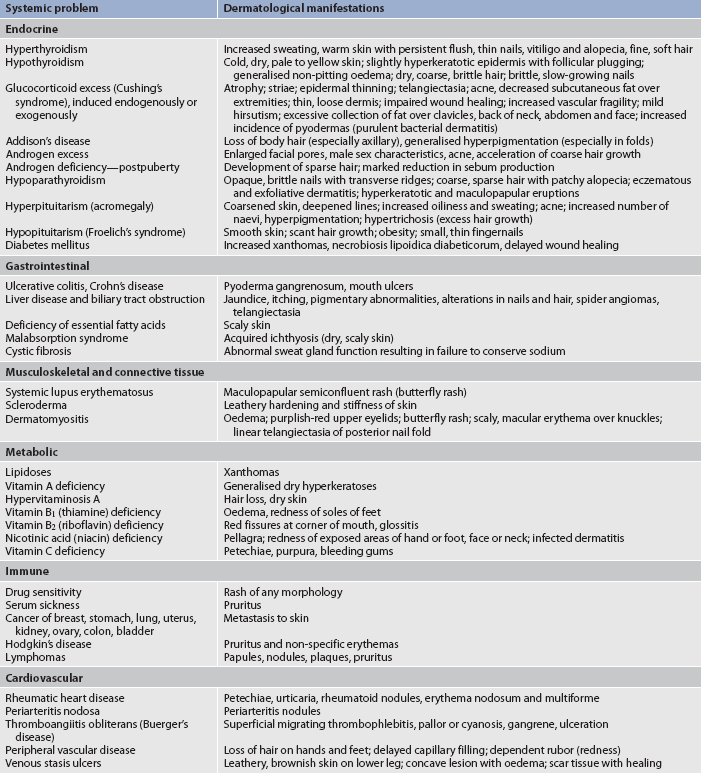

Diseases with dermatological manifestations

Dermatological manifestations of various diseases are listed in Table 23-12. The healthcare provider should always consider the possibility that a particular dermatosis is a clue to an internal, less obvious problem.

Certain life changes have recognised associated dermatoses. At puberty, male- or female-pattern hair growth will be evident as a secondary sex characteristic. Increased apocrine gland activity can lead to body odour. The increased sebaceous gland activity stimulated by androgens can result in seborrhoea and acne.

MULTIDISCIPLINARY CARE: DERMATOLOGICAL PROBLEMS

DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

A careful history is of prime importance in the diagnosis of skin problems. The nurse must be skilled at detecting any evidence that could lead to the cause of the extraordinary number of skin problems. After a careful history and physical examination, individual lesions are inspected. On the basis of the history, physical examination and appropriate diagnostic tests, either medical or surgical or combination therapy is planned.

COLLABORATIVE THERAPY

Many different treatment methods are used in dermatology. Advances in this field have brought relief to many previously chronic, untreatable conditions. Many of the specific therapeutic treatments require specialised equipment and are usually reserved for use by the dermatologist. Drug therapy is prescribed by many clinicians. The effectiveness of this therapy can often be related to the base (or vehicle) in which the medication is prepared. Table 23-13 summarises the common agents used as bases for topical preparations and their therapeutic considerations.

TABLE 23-13 Common bases for topical medications

| Agent | Therapeutic considerations |

|---|---|

| Powder | Promotion of dryness, increase in evaporation, absorption of moisture possible, common base for antifungal preparations |

| Lotion | Suspension of insoluble powders in water; cooling and drying, with residual powder film after evaporation of water |

| Cream | Emulsion of oil and water, most common base for topical medications, lubrication and protection |

| Ointment | Oil with differing amounts of water added in suspension, lubrication and prevention of dehydration, petrolatum most common |

| Paste | Mixture of powder and ointment, used when drying effect necessary because moisture is absorbed |

Phototherapy

Two types of UV light, or a combination of the two types (UVA, UVB), are used to treat many dermatological conditions. UV wavelengths cause erythema, desquamation and pigmentation, and may cause a temporary suppression of basal cell mitosis followed by a rebound increase in cell turnover.

Methoxsalen plus UVA light (PUVA) is a form of phototherapy. The photosensitising drug methoxsalen is given to patients before exposure to UVA to enhance the effect of UV light in the UVA spectrum. Usually a moisturising agent or a tar preparation is applied to the affected area in a thin layer before exposure to UVB. Conditions that are responsive to effective wavelengths with or without drugs include atopic dermatitis, cutaneous T cell lymphoma, pruritus, psoriasis and vitiligo.

UV light in specific wavelengths can be produced artificially. Therapeutic doses of UVA and UVB can be measured and used to treat spectrum-specific diseases (see Fig 23-10). Frequent skin assessments must be performed on all patients receiving phototherapy. Inappropriate exposure to UV light can result in BCC or SCC, as well as severe erythema or burns to the skin. Patients should be cautioned about the potential hazards of using photosensitising chemicals and further exposure to UV rays from sunlight or artificial UV light during the course of phototherapy. Protective eyewear that blocks 100% of UV light is prescribed for patients receiving PUVA because methoxsalen is absorbed by the lens of the eye. The eyewear is used to prevent cataract formation. Patients are instructed to use the eyewear for 24 hours after taking the medication when outdoors or near a bright window because UVA penetrates glass. The immunosuppressive effects related to the use of PUVA require careful ongoing monitoring of these patients.

Radiation therapy

The use of radiation for the treatment of cutaneous malignancies varies greatly according to local practice and availability. Even if radiation therapy is planned, a biopsy must first be performed to obtain a pathological diagnosis.

Radiation to malignant cutaneous lesions is a painless treatment that is similar in cost to surgery. It produces minimal damage to surrounding tissue. It is a particularly effective treatment for older adults or debilitated patients who cannot tolerate even a minor surgical procedure and for such areas as the nose, eyelids and canthal areas, where preservation of the surrounding tissue is of prime consideration. Careful shielding is necessary to prevent ocular lens damage if the irradiated area is around the eyes.

Radiation therapy usually requires multiple visits to a radiology department. It is most effective on lesions above the neck. However, it produces permanent hair loss (alopecia) of the irradiated areas. Other adverse effects include telangiectasia, atrophy, hyperpigmentation, depigmentation, ulceration, chronic radiodermatitis, BCC and SCC. (Radiation therapy is discussed in Ch 15.)

Total-body skin irradiation (whereby the body is bombarded with high-energy electrons) may be the treatment of choice or adjunctive therapy for cutaneous T cell lymphoma. Treatment follows a lengthy course. Patients experience varying degrees of hair loss and radiation dermatitis with transient loss of sweat gland function. This treatment causes premature ageing of the skin.

Laser technology

Laser treatment is expanding rapidly as an efficient surgical tool for many types of dermatological problems (see Box 23-1). Lasers are able to produce measurable, repeatable, consistent zones of tissue damage. They can cut, coagulate and vaporise tissue to some degree. The wavelength determines the type of delivery system used and the intensity of the energy delivered.

The surgical use of laser energy requires a focusing device to produce a small, high-density spot of energy that can be carefully focused on the surgical site and controllably directed to the operative site. Written policies and procedures should cover laser safety and be reviewed by all personnel working with laser equipment.17 Laser light does not accumulate in body cells and cannot cause cumulative cellular changes or damage.

Several types of lasers are available in most clinics and hospitals. The carbon dioxide laser is the most common treatment. This laser has numerous applications as a vaporising and cutting tool for most tissues. The argon laser emits light that is primarily absorbed by haemoglobin and helps in the treatment of vascular and other pigmented lesions. Other, less common lasers include the use of copper and gold vapours, tunable dye and neodymium:yttrium-aluminium-garnet (Nd:YAG). Dermatological uses of the various lasers include coagulation of vascular lesions, skin resurfacing, removal of birthmarks and tattoos, and the treatment of BCC, condylomas, plantar warts and keloids.

Drug therapy

Antibiotics

Antibiotics are used both topically and systemically to treat dermatological problems and they are often used in combination. If topical antibiotics are used, they should be applied lightly to clean skin. Mupirocin and bacitracin are common topical antibiotics used for dermatological conditions. Specific topical antibiotics include mupirocin (used for Staphylococcus), gentamicin (used for Staphylococcus and most Gram-negative organisms) and erythromycin (used for Gram-positive cocci [staphylococci and streptococci] and Gram-negative cocci and bacilli). Topical erythromycin and clindamycin (solutions or gels) are used in the treatment of acne vulgaris.18 In certain circumstances, topical antibiotics are used prophylactically; however, because of the emergence of resistance organisms, the use needs to be carefully considered.

If there are signs of systemic infection, a systemic antibiotic should be used. Systemic antibiotics are useful in the treatment of bacterial infections and acne vulgaris. The most frequently used are synthetic penicillin, erythromycin and tetracycline. These drugs are particularly useful for erysipelas, cellulitis, carbuncles and severe, infected eczema. Culture and sensitivity of the lesion can guide the choice of antibiotic. Patients require drug-specific instructions on the proper technique of taking or applying antibiotics. For instance, oral tetracycline must be taken on an empty stomach and should never be taken with a dairy product, which would interfere with absorption.

Corticosteroids

Corticosteroids are particularly effective in treating a wide variety of dermatological conditions and can be used topically, intralesionally or systemically. Topical corticosteroids are used for their local anti-inflammatory action, as well as for their antipruritic effects.18 Attempts to diagnose a lesion should be made before a corticosteroid preparation is applied because corticosteroids will mask the clinical manifestations. Once a sufficient amount of medication is dispensed, limits should be set on the duration and frequency of application. The potency of a particular preparation is related to the concentration of active drug in the preparation. With prolonged use, the more potent corticosteroid formulations can cause adrenal suppression, especially if occlusive dressings are used. High-potency corticosteroids may produce side effects when their use is prolonged, including atrophy of the skin resulting from impaired cell mitosis and capillary fragility and susceptibility to bruising. In general, dermal and epidermal atrophy does not occur until a corticosteroid has been used for 2–3 weeks. If drug use is discontinued at the first sign of atrophy, recovery usually occurs in several weeks. Rosacea eruptions, severe exacerbations of acne vulgaris and dermatophyte infections may also occur. Rebound dermatitis is not uncommon when therapy is stopped and this can be reduced by tapering the use of high-potency topical corticosteroids from the time patient improvement is noted.

Low-potency corticosteroids, such as hydrocortisone, act more slowly but can be used for a longer period of time without producing serious side effects. Low-potency corticosteroids are safe to use on the face and intertriginous (opposing skin surfaces) areas, such as the axillae. The potency of a particular preparation is related to the concentration of active drug in the preparation. The ointment form represents the most efficient delivery system for dry skin conditions. Creams and ointments should be applied in thin layers and slowly massaged into the site one to three times a day as prescribed. Accurate and adequate topical therapy is often the key to a successful outcome.

Intralesional corticosteroids are injected directly into or just beneath the lesion. This method provides a reservoir of medication with an effect lasting several weeks to months. Intralesional injection is commonly used in the treatment of psoriasis, alopecia areata (patchy hair loss), cystic acne, hypertrophic scars and keloids.

Systemic corticosteroids can have remarkable results in the treatment of dermatological conditions. However, they often have undesirable systemic effects (see Ch 49). Corticosteroids can be administered as short-term therapy for acute conditions such as contact dermatitis. Long-term corticosteroid therapy for dermatological conditions is reserved for chronic bullous diseases, for severe systemic effects of collagen and immunological responses, and as a last resort when other therapies have failed.

Antihistamines

Oral antihistamines are used to treat conditions that exhibit urticaria, angio-oedema and pruritus. Dermatological problems, such as atopic dermatitis, psoriasis and contact dermatitis, and other allergic cutaneous reactions can be mediated with the use of histamine blockers. Antihistamines compete with histamine for the receptor site, thus preventing its effect. Antihistamines may have anticholinergic and/or sedative effects. Several different antihistamines may have to be tried before the satisfactory therapeutic effect is achieved. Sedating antihistamines are often preferred because the tranquillising and sedative effects offer symptom relief. The patient should be warned about sedative effects, a particular problem when driving or operating heavy machinery. A newer generation of antihistamines, such as loratidine and fexofenadine, bind to peripheral histamine receptors, providing antihistamine action without sedation. These non-sedating antihistamines are not generally effective for controlling pruritus. Antihistamines should be used with particular caution in older adults because of their long half-lives and their anticholinergic effects.

Topical fluorouracil

Fluorouracil is a topical cytotoxic agent with selective toxicity for sun-damaged cells. Fluorouracil (5% and 1%) is used for the treatment of premalignant skin disease, especially actinic keratosis. Because systemic absorption of the drug is minimal, systemic side effects are virtually non-existent. When a diagnosis of skin cancer has been established, fluorouracil is generally not used.

Patient compliance is the major problem with the use of fluorouracil. The medication produces painful, eroded areas over the damaged skin within 4 days. Treatment must continue with applications one to two times a day for 2–4 weeks. Healing may take up to 3 weeks after medication is stopped. Because fluorouracil is a photosensitising drug, the patient must be instructed to avoid sunlight during treatment. Patients should be educated about the effect of the medication and should be warned that they will look worse before they look better. After effective treatment, treated skin is smooth and free of actinic keratoses, although sometimes a second course is necessary due to recurrence.

Immunomodulators

Topical immunomodulators, such as tacrolimus, are newer non-steroidal medications used to treat atopic dermatitis. They work by suppressing an overreactive immune system. The side effects are minimal and may include a transient burning or feeling of heat at the application site. An increased risk of skin cancer and precancerous lesions may be associated with these drugs.

Another topical immunomodulator, imiquimod, acts to stimulate the production of α-interferon and other cytokines to enhance cell-mediated immunity. It boosts the immune response only where applied and is safe for transplant patients. This medication is currently being used for external genital warts, actinic keratoses and superficial BCCs. Most patients using this cream experience skin reactions, including redness, swelling, sore or blister, peeling, itching and burning.

DIAGNOSTIC AND SURGICAL THERAPY

Skin scraping

Scraping is done with a scalpel blade to obtain a sample of surface cells for microscopic inspection and diagnosis.

Electrodesiccation and electrocoagulation

Electrical energy can be converted to heat by the tip of an electrode. This results in tissue being destroyed by burning. The major uses of this type of therapy are point coagulation of bleeding vessels to obtain haemostasis and destruction of small telangiectasias. Electrodesiccation usually involves more superficial destruction and a monopolar electrode is used. Electrocoagulation has a deeper effect, with better haemostasis and an increased possibility of scarring. A dipolar electrode is used for electrocoagulation.

Curettage

Curettage is the removal of tissue using an instrument with a circular cutting edge attached to a handle (see Fig 23-11). The tissue is scooped away. Although the curette is not usually strong enough to cut normal skin, it is useful for removing many types of small skin tumours, such as warts, seborrhoeic keratoses and small BCCs and SCCs. The area to be curetted is anaesthetised before the procedure. Haemostasis is obtained by use of one of several methods: electrocoagulation, chemical haemostasis (aluminium chloride), gelatine foam or a gauze pressure dressing. A small scar may form. The specimen may be sent for biopsy.

Punch biopsy

Punch biopsy is a common dermatological procedure used to obtain a tissue sample for histological study or to remove small lesions (see Fig 23-12). Its use is generally reserved for lesions smaller than 0.5 cm. Before local anaesthesia is used, the biopsy area is outlined so that landmarks will not be obscured by the anaesthetising agent. The biopsy punch cores out a small cylinder of skin when its sharp edge is twirled between the fingers. The core of skin is snipped from the subcutaneous fat and appropriately preserved for examination. Haemostasis is achieved by using methods as with curettage, but sites of 4 mm or larger are often closed with sutures. Other types of biopsies are discussed in Table 22-9.

Cryosurgery

Cryosurgery is the use of subfreezing temperatures to perform surgery. Cryosurgery is a useful treatment for common and genital warts, cutaneous tags, seborrhoeic keratoses, actinic keratoses and many other less common skin conditions. Topical liquid nitrogen (−196°C) is the agent most commonly used for cryosurgery. The mechanism of injury involves direct cellular freezing as well as vascular stasis (stoppage or slowdown in the flow of blood), which develops after thawing. Intracellular ice formation causes the cell to rupture during thawing, leading to cell death and necrosis of the treated tissue.

Liquid nitrogen can be applied topically (directly onto the benign or precancerous lesion) with a cottonwool swab or with the appropriate container for several freeze-and-thaw cycles. Patients are informed that they will feel a cold and/or stinging sensation. The lesion will first become swollen and red, and it may blister. Next, a scab will form and fall off in 1–3 weeks. The skin lesion will be sloughed along with the scab. Growth of new skin follows.

Cryosurgery is inexpensive, rapid and leaves minimal scarring; however, a small area of hypopigmentation may occur. The major disadvantages of this treatment are lack of a tissue specimen and potential for destruction of adjacent healthy tissue.

Excision

Excision should be considered if the lesion involves the dermis. Complete closure of the excised area usually results in a good cosmetic result.

A specific type of excision is Mohs’ micrographic surgery, which is the microscopically controlled removal of a cutaneous malignancy. This procedure sections the surgical specimen horizontally, so that 100% of the surgical margin can be examined. Tissue is removed in thin layers and all margins of the specimen are mapped to determine whether tumour remains. Any residual tumour not removed by the first surgical excision can be removed in serial excisions performed the same day. The benefit of this treatment is preservation of normal tissue, producing the smallest possible wound. The procedure is done on an outpatient basis with the patient receiving a local anaesthetic.

NURSING MANAGEMENT: DERMATOLOGICAL PROBLEMS

NURSING MANAGEMENT: DERMATOLOGICAL PROBLEMS

Ambulatory and home care

Ambulatory and home care

Dermatological conditions are not common reasons for hospitalisation. Although it may not be the primary reason for hospitalisation, many hospitalised patients will exhibit concurrent skin problems that warrant nursing intervention and patient education.

If the patient is in an acute care setting, the nurse will both administer and teach the appropriate treatments. If the patient is in an outpatient setting, the nursing focus is on patient teaching, with opportunities provided for demonstration and repeated demonstration. Subsequent visits provide the opportunity to evaluate patient understanding and treatment effectiveness.

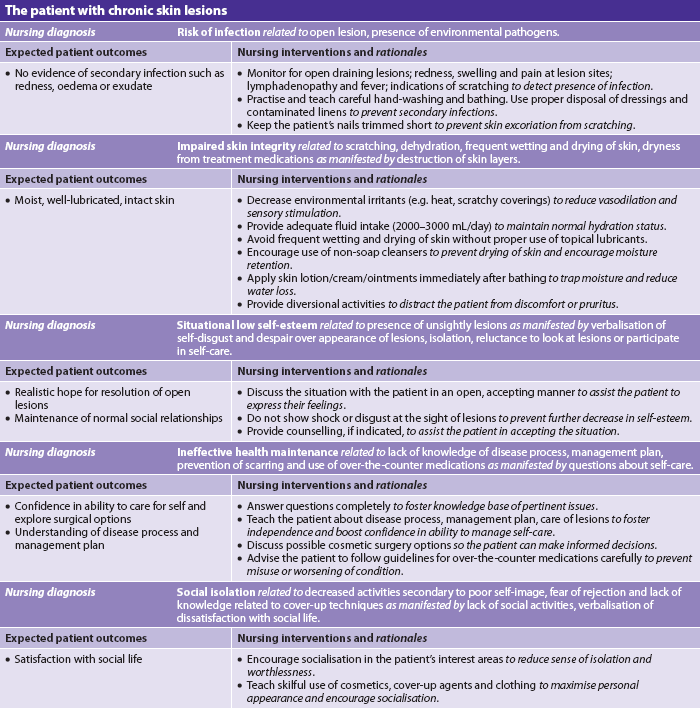

Nursing interventions related to dermatological conditions fall into broad categories. They are applicable to many skin problems in both inpatient and outpatient settings. The nursing care for a patient with chronic skin lesions is presented in NCP 23-1.

Wet dressings

Wet dressings

Wet dressings are commonly used when the skin is itchy, dry and/or inflamed. In addition, wet dressings increase penetration of topical medications, promote sleep by relieving discomfort, protect against scratching and enhance removal of scales, crusts and exudate. Materials such as thin sheeting, gauze sponges and tubular retention bandages can be used for dressings. Ingenuity is sometimes required when odd-shaped parts of the body must be covered.

The prescribed dressing is put into fresh solution, squeezed until it is no longer dripping and then applied to the affected area, avoiding normal skin tissue where possible. The dressing should be left in place for an hour or longer as tolerated. This treatment is generally done once or twice a day. If the skin appears macerated (softened), the dressings should be discontinued for 2–3 hours. The patient should be protected from discomfort and chilling by using linens and bedclothes with pads or plastic.

Wet dressings do not need to be sterile. They should be cool when an anti-inflammatory effect is desired and tepid when the purpose is to debride an infected, crusted lesion. These treatments are excellent ways to remove the scabs left by the collection of debris at a wound site.

Tap water at room temperature is the most common solution where water quality is adequate. Filtered or sterile water may be indicated in some locations.

Baths

Baths

Baths are appropriate when large body areas need to be treated. They also have sedative and antipruritic effects. Some medications, such as colloidal oatmeal, water-soluble oils, pine tar and sodium bicarbonate, can be added directly to the bath water. Patients need to follow the instructions on the product label for quantities to add to bath water. Many of these products can also be used in the shower. The bathtub should be full enough to cover affected areas. Both the bath water and the prescribed solution should be at a temperature that is comfortable for the patient. The patient can soak for 15–20 minutes three to four times a day, depending on the severity of the dermatitis and the patient’s discomfort. It is important to stress to the patient that the skin should not be rubbed dry with a towel but gently patted to prevent increasing irritation and inflammation. The addition of oils makes the bathtub or shower extremely slippery and should be used carefully. If oils are used in the bath, the utmost caution must be used in transferring patients to prevent accidents. To sustain the hydrating effect, sealing moisturisers or medications should be applied to the skin directly after the bath. This helps retain the moisture in the hydrated cells.

Topical medications

Topical medications

A thin layer of ointment, cream or lotion should be applied to clean skin and spread evenly in a downward motion. An alternative method is to apply the medication directly onto the dressings. Pastes are designed to protect the affected area. They should be applied thickly with a tongue blade or a gloved hand. Draining lesions and lesions with greasy medication can be covered with a light dressing to prevent soiling of clothes. Patients need specific directions on proper application techniques of prescribed topical medications.

Control of pruritus

Control of pruritus

Pruritus (itching) can be caused by almost any physical or chemical stimulus to the skin, such as drugs, insect bites and dry skin. The itch sensation is carried by the same non-myelinated nerve fibres as pain. If the epidermis is damaged or absent, the sensation will be felt as pain rather than an itch.

The itch–scratch cycle must be broken to prevent excoriation. Control of pruritus is also important because it is difficult to diagnose a lesion that is excoriated and inflamed. Certain circumstances make itching worse. Anything that causes vasodilatation, such as heat or rubbing, should be avoided. Dryness of the skin lowers the itch threshold and increases the itch sensation. The nurse can use or teach the patient various methods to break the itch–scratch cycle. A cool environment may cause vasoconstriction and decrease itching. Topically applied menthol, camphor or phenol can be used to numb the itch receptors. Systemic antihistamines can be used if necessary to provide relief to a patient while the underlying cause of the pruritus is diagnosed and treated. The principal side effect of most antihistamines is sedation. This may be desirable because pruritus is often worse at night and can interfere with sleep.

Lichenification is a thickening of skin as a result of the proliferation of keratinocytes with accentuation of the normal markings of the skin. Lichenification is caused by scratching or rubbing of the skin and is often associated with atopic dermatoses and pruritic conditions. Although any area of the body may be affected, the hands and forearms are common sites. Treatment of the cause of the itching is the key to prevention of lichenification. Excoriations are often evident in the thickened skin as a result of the pruritus.

There are many over-the-counter medications available to treat minor pruritic skin conditions, such as prickly heat, but patients should be urged to seek medical treatment if itching continues.

Prevention of spread

Prevention of spread

Although most skin problems are not contagious, infection precautions indicate the need for gloves with open or bleeding wounds. Procedures should be explained to the patient in order to avoid demoralising an already sensitive patient. However, if in doubt, the nurse should wear gloves until a definite diagnosis has been established. The most common contagious lesions that the nurse should be cautious about include impetigo, Staphylococcus, pyoderma, primary chancre and secondary syphilis lesions, scabies and pediculosis. Careful hand-washing and safe disposal of soiled dressings are the best means of preventing spread of skin problems.

Prevention of secondary infections

Prevention of secondary infections

Open lesions on the skin are susceptible to invasion by other viral, bacterial or fungal organisms. Meticulous hygiene, hand-washing and dressing changes are important to prevent secondary infections. Also, the patient should be warned about scratching lesions, which can cause excoriations and create a portal of entry for pathogens. The patient’s nails should be trimmed short to minimise trauma from scratching.

Specific skin care

Specific skin care

Nurses are often in a position to advise patients regarding care of the skin following simple dermatological surgical procedures, such as skin biopsy, excision and cryosurgery. Patient follow-up should be individualised. In general, instructions include dressing changes, use of topical antibiotics, and the signs and symptoms of infection. After a dermatological procedure any oozing wound should be regularly cleansed with a saline solution and a dressing that is both absorbent and non-adherent applied.

Wounds that are kept moist and covered heal more rapidly and with less scarring. Initially, a scab should be left alone to be a protective coating for the damaged skin beneath it. Scabs can be covered during the day for cosmetic purposes and should be protected at night from premature removal through rubbing against sheets. Scabs will separate naturally from healed epidermis.

A wound that requires sutures can be covered with a variety of different dressings. Sutures are generally removed within 4–10 days. Sometimes every other stitch is removed after the third day. Incision lines may require daily cleansing, usually with plain tap water. If necessary, a topical antibiotic can be applied and the wound either covered with a dry sterile dressing or left open to air. The patient may experience some swelling and discomfort in the first 24 hours. Mild analgesics such as paracetamol should control the discomfort. The patient needs to know the manifestations of inflammation, such as redness, fever or increased pain or swelling, and signs of infection, such as purulent drainage. If these manifestations occur, they should be reported to the healthcare provider.

Psychological effects of chronic dermatological problems

Psychological effects of chronic dermatological problems

Emotional stress can occur for persons who suffer from chronic skin problems, such as psoriasis, atopic dermatitis or severe acne. The sequelae of chronic skin problems could result in employment problems with subsequent financial implications, a poor self-image, problems with sexuality, and increasing and progressive frustration. The usual lack of systemic overt illness coupled with the visibility of the skin lesions often presents a real problem to the patient.

The nurse must continue to be optimistic and help the patient to comply with the prescribed regimen. The patient must be allowed to verbalise the ‘Why me?’ question, even though there is no ready answer. Reinforcement of the prescribed hygiene and treatment measures is an important part of the nursing management. Dermatology patient support groups are listed with the Australasian College of Dermatologists (see Resources on p 542). These groups are extremely useful for accurate patient support and education materials.

Many lesions can be camouflaged with the skilful use of cosmetics. Individual sensitivity to product ingredients must always be considered in the selection of a cosmetic product. Oil-free, hypoallergenic cosmetics are available and could be beneficial to allergic patients. Rehabilitative cosmetics are available to help camouflage and de-emphasise lesions such as vitiligo (loss of pigmentation), melasma (tan to brown patches on the face) or healed postoperative wound sites. These commercially available products are opaque, smudge resistant and water resistant.

In addition to specific skin conditions that tend to chronicity, other factors affecting the outcome of long-term dermatological problems include skin type, a history of previous exacerbations, family history, complications, intolerance to therapy, environmental factors, lack of adherence to the prescribed regimen, endocrine factors and psychological factors. Lesions that follow a chronic pattern often are associated with lichenification and scarring.

Pathophysiological effects of chronic dermatological problems

Pathophysiological effects of chronic dermatological problems

Scarring and lichenification are the result of chronic dermatological problems. Scars occur when ulceration takes place and reflect the pattern of healing in the area. Scars are pink and vascular at first. As they age they become avascular and white with increasing strength. Different parts of the body scar differently; for example, the face and neck heal fairly well because of a good blood supply. Scar formation is described in Chapter 12.

The location of the scar is the determining factor with respect to its cosmetic implications. Facial scars are the most damaging psychologically because they are so visible. Creative use of cosmetics can do much to mask the scarring of chronic skin conditions. The best treatment is prevention of scarring by control of the problem in the acute phase.

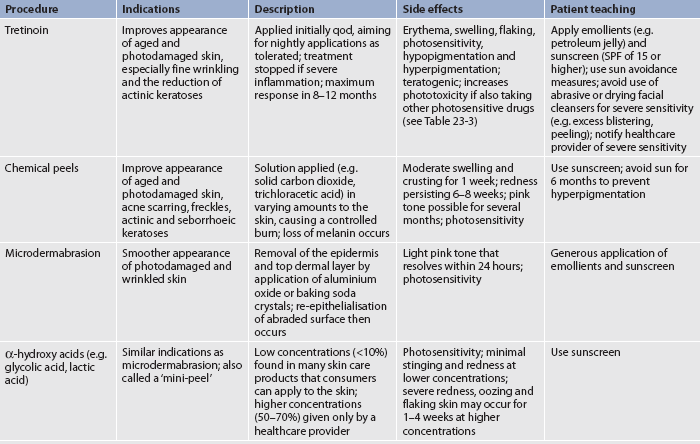

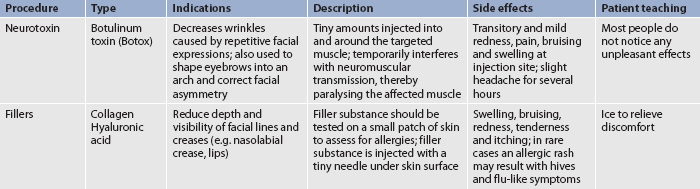

Cosmetic procedures

The vast array of cosmetic procedures is almost limitless. Cosmetic procedures can include chemical peels, toxin injections, collagen fillers, laser surgery, breast enlargement and reduction (see Ch 51), laser surgery, facelift, eyelid lift and liposuction. Common cosmetic procedures are presented in Tables 23-14 and 23-15.

The reasons for undergoing these procedures are as varied as the techniques. The most common reason that people suffer the discomfort and financial expense (most are not covered by insurance) of a cosmetic procedure is to improve their body image. People project their personal image of themselves. If they feel better about themselves after having cosmetic surgery, they will often act in a more confident and self-assured manner. Often social position and economic considerations are part of the decision. Increased longevity provides a larger population to whom cosmetic procedures are especially appealing.

Regardless of the reasons, the nurse should maintain a supportive, non-judgemental attitude about cosmetic procedures. If the patient wishes to change or enhance a body feature perceived as unattractive, it is a personal decision and the nurse should support this decision.

ELECTIVE SURGERY

Laser surgery

When a laser beam enters the skin, the light can affect skin structures by scattering, absorbing or passing through different layers. The spectrum of clinical application for each laser depends on the depth of the wavelength emitted and the operator technique. Alterations in technique, such as pulse duration and the number of passes over the skin, vary the result.19 New hand-piece technology with multiple spot size and cooling device additions have also generated new flexibility in laser technology.

Lasers can reduce fine wrinkles around the lips or eyes and remove facial lesions (see Box 23-1). Compared to other cosmetic procedures, bleeding and scarring do not occur. Swelling, redness and bruising are common after treatment. The treated areas usually are kept moist with ointment or occlusive dressings (surgical bandages) for the first few days. The treated skin must be protected from the sun.

Facelift

A facelift (rhytidoplasty) is the lifting and repositioning of the lower two-thirds of the face and neck to improve appearance (see Fig 23-13). Indications for this procedure include the following:

1. redundant soft tissue resulting from disease (e.g. acne scarring)

2. asymmetrical redundancy of soft tissues (e.g. facial palsy)

3. redundant soft tissue resulting from trauma

5. redundant soft tissues resulting from solar elastosis (sagging of the skin as a result of sun damage), changes in body weight and the effects of gravity

The surgical approach and lines of incisions vary according to the nature of the deformity and the position of the hairline. Eyelid lifts (blepharoplasty) with similar indications are performed to remove redundant tissue and possibly improve the field of vision. Prevention of haematoma formation is the most important postoperative consideration. Application of ice packs is usually used in the first 24–48 hours to reduce the possibility of haematoma formation. Complications can occur if the person smokes or is involved in vigorous exercise. Usually there is little pain. The sutures are removed some time from the fifth to the tenth postoperative day. Antibiotics are used at the discretion of the surgeon. Infection is not a common problem.

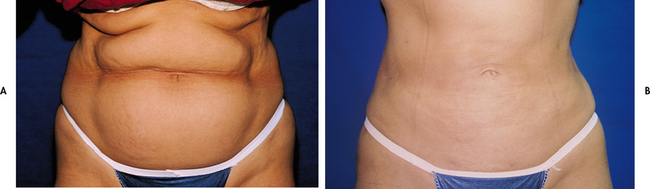

Liposuction

Liposuction is a technique for removing subcutaneous fat to improve facial and body contours. Although not a substitute for diet and exercise, it can be successful in removing areas of fat from virtually any body area that is resistant to other techniques (see Fig 23-14).

Although relatively free of complications, possible contraindications for the procedure include use of anticoagulants, uncontrolled hypertension, diabetes mellitus and poor cardiovascular status. Persons under 40 years of age with good skin elasticity are the best candidates. However, patients ranging in age from 16 to 70 years can be treated successfully.

The procedure may be performed on an outpatient basis with the aid of local anaesthesia or as a day surgery procedure. One or more sessions may be necessary depending on the size of the area to be treated. A blunt-tipped cannula is inserted through a 10 mm incision and pushed into the fat to break it loose from the fibrous stroma. Multiple repeated thrusts disrupt the fat and create tunnels. The loosened fat is removed with a powerful suction. The area is taped because firm bandaging helps contour the skin and reduce the chance of postoperative bleeding and fluid accumulation. It may take several months for the final results to be evident.

NURSING MANAGEMENT: COSMETIC SURGERY

NURSING MANAGEMENT: COSMETIC SURGERY

Many cosmetic surgical procedures are performed in well-equipped day surgery units or in plastic surgeons’ offices. Several nursing interventions are appropriate for the patient, regardless of where the cosmetic surgery was done.

Preoperative management

Preoperative management

A major consideration relates to informed consent and realistic expectations of what cosmetic surgery can accomplish. Although this information is usually provided by the surgeon, the nurse can and should reinforce this information and answer questions and concerns. For instance, a facelift has little or no effect on deep wrinkling of the forehead and temples, deep nasolabial grooves or vertical lip wrinkles. Before and after treatment photographs of similar cases are often useful in helping the patient to set realistic expectations.

The patient also needs to understand the time frame for healing. Complete results may not be evident until a year after the procedure. The oozing, crusting stage of the abrasive procedure must be explained so the patient can plan time off from work if this seems necessary. The final results of the cosmetic procedure are affected by the patient’s age, general state of health and skin type. If a health problem is present, efforts should be made to correct or control the problem before the procedure is performed.

Postoperative management

Postoperative management

Most cosmetic procedures are not extremely painful. Usually mild analgesics are sufficient to keep the patient comfortable. Although infection is not a common problem after cosmetic surgery, the nurse should assess the surgical sites for signs of infection. The patient should be aware of signs of infection and told to report any such signs and symptoms immediately so that appropriate antibiotic intervention can be started.

If the surgery involved alteration in the circulation to the skin, such as the undermining done in a facelift, a careful monitoring of adequate circulation is necessary. Warm, pink skin that blanches on pressure indicates that adequate circulation is present in the surgical area. Supportive, compressive dressings and ice packs may be necessary early in the postoperative period.

Skin grafts

USES

Skin grafts may be necessary to provide protection to underlying structures or to reconstruct areas for cosmetic or functional purposes. Ideally, wounds heal by primary intention. However, large, surgically created wounds, trauma and chronic wounds can cause extensive tissue destruction, making primary intention healing impossible. In these cases, skin grafting may be necessary to close the defect. Improved surgical techniques make it possible to graft skin, bone, cartilage, fat, fascia, muscles and nerves. For cosmetically pleasing results, the colour, thickness, texture and hair-growing nature of skin used for grafting must be chosen to match the recipient site. (Skin grafting is discussed in Ch 24.)

TYPES

The two types of skin grafts are free grafts and skin flaps. Free grafts are further classified according to the method of providing a blood supply to the grafted skin. One method is to transfer the graft (epidermis and part or all of the dermis) to the recipient site from the donor site. If the graft is an autograft (from the patient’s own body) or an isograft (from an identical twin), it will revascularise and become fixed to the new site. Chapter 24 discusses full and split skin grafts in detail. Another method of free skin grafting is by reconstructive microsurgery. With the use of an operating microscope, circulation is immediately established in the free flap by anastomosis of the blood vessels from the skin flap to the vessels in the recipient site.

Skin flaps involve moving a section of skin and subcutaneous tissue from one part of the body to another without terminating the vascular attachment. The vascular attachment is called a pedicle. Skin flaps are used to cover wounds that have a poor vascular bed, when padding is needed, and to cover wounds over cartilage and bone. There may be a need for intermediate flap placement if the recipient site is far removed from the donor site. For instance, a skin flap from the thigh to the head would require an intermediate graft. The flap is advanced to the recipient site when circulation is well established at the intermediate site. The type of flap and the route of transfer are determined according to the needs of the patient and the nature of the defect to be repaired.

Soft-tissue expansion is a technique for providing skin for resurfacing a defect, such as a burn scar, for removing a disfiguring mark, such as a tattoo, or as a preliminary step in breast reconstruction. A subcutaneous tissue expander of an appropriate size and shape is placed under the skin, usually as an outpatient procedure. Weekly expansion with saline solution can be undertaken in a healthcare setting or by the patient at home. This expansion procedure is repeated until the skin reaches the size needed for the repair. This may take from several weeks to 3–4 months. Once sufficient skin is available, the old incision is opened, the expander is removed and the soft tissue is ready to be used as an advancement flap. The tissue expander next to a defect retains the primary tissue characteristics, such as colour and texture.

Malignant melanoma and dysplastic naevi

CASE STUDY

Patient profile

Michael Patrick, 37, is a Caucasian, fair-skinned, blue-eyed park ranger who enjoys fishing and boating. He comes to the clinic for evaluation of a changing mole.

CRITICAL THINKING QUESTIONS

1. What risk factors for malignant melanoma does this patient have?

2. What are the usual manifestations associated with malignant melanoma?

3. What is the prognosis for a patient with this stage of malignant melanoma?

4. What treatment options are available for this patient?

5. How would you address this patient regarding his anxiety over the treatment outcomes?

6. What is the priority of care for this patient?

7. How would you address future sun exposure for this patient in a patient teaching plan?

8. Based on the assessment data presented, write one or more appropriate nursing diagnoses. Are there any collaborative problems?

1. The nurse advises a patient with photosensitivity to use a sunscreen that contains:

2. In teaching a patient who is using topical corticosteroids to treat an acute dermatitis, the nurse should tell the patient that:

3. A patient with psoriasis tells the nurse that she has left her job as a receptionist because she feels her appearance is disgusting to customers. The nursing diagnosis that best describes this patient response is:

4. In teaching a patient with malignant melanoma about this disorder, the nurse recognises that the prognosis of the patient is most dependent on:

5. The nurse identifies that a patient with a diagnosis of which of the following disorders is most at risk of spreading the disease?

6. A mother and her two children have been diagnosed with pediculosis corporis at a health centre. An appropriate measure in treating this condition is:

7. A common site for the lesions associated with atopic dermatitis is the:

8. During assessment of a patient the nurse notes an area of red, sharply defined plaques covered with silvery scales that are mildly itchy on the patient’s knee and elbow. The nurse recognises this finding as:

9. The dermatological manifestations of Cushing’s disease would include:

10. Important patient teaching after a chemical peel includes:

1 Berger T. Skin, hair, and nails. In Tierney L, et al, eds.: Current medical diagnosis and treatment, 47th edn., New York: McGraw-Hill, 2008.

2 The Cancer Council Australia. Skin cancer facts and figures. Available at www.cancer.org.au/cancersmartlifestyle/SunSmart/Skincancerfactsandfigures.htm. accessed 25 February 2011.

3 Standards Australia. Sunscreen products—evaluation and classification. 5th edn. AS/NZS2604:1998. Sydney: Standards Australia, 1998.

4 Mackie BS, Mackie LE. The PABA story. Australas J Dermatol. 1999;40:51–53.

5 National Health and Medical Research Council. Clinical practice guidelines. Non-melanoma skin cancer: guidelines for treatment and management in Australia. Available at www.nhmrc.gov.au/publications/synopses/cp87syn.htm, 2002. accessed 25 February 2011.

6 Georgouras KE, Stanford DG, Pailthorpe MI. Sun protective clothing in Australia and the Australian/New Zealand standard: an overview. Australas J Dermatol. 1997;38:S79–S82.

7 Hill MJ. Dermatology nursing essentials: a core curriculum, 2nd edn. New Jersey: Dermatology Nurses Association, 2003.

8 Jarvis C. Physical examination and health assessment, 6th edn. St Louis: Elsevier, 2011.

9 Rigel DS. Cancer of the skin. Philadelphia: Elsevier, 2005.

10 The Cancer Council Australia. About skin cancer. Available at www.cancer.org.au//cancersmartlifestyle/SunSmart/Aboutskincancer.htm. accessed 25 February 2011.

11 American Cancer Society (ACS). Cancer facts and figures, 2005. Atlanta: ACS, 2005.

12 Berwick M, Erdei E, Hay J. Melanoma epidemiology and public health. Dermatol Clin. 2009;27:205.

13 Ministry of Health New Zealand. Melanoma. Available at www.moh.govt.nz/moh.nsf/pagesmh/8691/$File/melanoma-guideline-brochure-nov08.pdf. accessed 25 February 2011.

14 Hansson J. Familial melanoma. Surg Clin North Am. 2008;88:897.

15 Rubin K. Management of metastatic melanoma: nursing challenges today and tomorrow. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2009;13:81.

16 American Cancer Society. Melanoma skin cancer. Available at www.cancer.org/cancer/skincancer-melanoma/detailedguide/melanoma-skin-cancer-survival-rates. accessed 25 February 2011.

17 Andersen K. Safe use of lasers in the operating room: what perioperative nurses should know. AORN J. 2004;79:171–188.

18 Bryant B, Knights K, Salerno E. Pharmacology for health professionals. Sydney: Elsevier, 2007.

19 Friedman S, Lippitz J. Chemical peels, dermabrasion and laser therapy. Disease-a-Month. 2009;55:223.

Australasian College of Dermatologists. www.dermcoll.asn.au

Australian Dermatology Nurses Association. www.adna.org.au

Australian Wound Management Association Inc. www.awma.com.au

Cancer Council Australia. www.cancer.org.au

Cancer Society of New Zealand. www.cancernz.org.nz

DermNet New Zealand. www.dermnetnz.org

Eczema Association of Australia Inc. www.eczema.org.au

Ego Pharmaceuticals Pty Ltd. www.egopharm.com.au

Health Insite: skin diseases (Australia). www.healthinsite.gov.au/topics/Skin_Diseases

Melanoma Foundation. http://sydney.edu.au/medicine/melanoma-foundation/

National Psoriasis Organisation. www.psoriasis.org/NetCommunity/Page.aspx?pid=1336

New South Wales Poisons Information Centre. www.chw.edu.au/poisons/

Queensland Poisons Information Centre. www.health.qld.gov.au/poisonsinformationcentre/

Therapeutic Guidelines: dermatology. www.tg.com.au/?sectionid=43