Adjuvant Analgesics for Malignant Bowel Obstruction

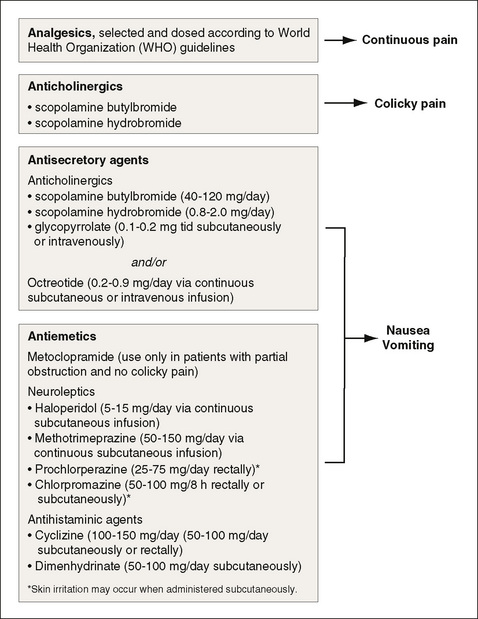

BOWEL obstruction can occur in any patient with cancer but is most common in those with ovarian or GI cancers (Davis, Hinshaw, 2006). This complication occurs most frequently in the advanced stages of the illness (Mercadante, Casuccio, Mangione, 2007). Malignant bowel obstruction (MBO) is caused usually by external compression of the bowel lumen by an adjacent tumor or masses of the mesentery or omentum, or by abdominal or pelvic adhesions. Surgical correction of MBO is usually not an option for patients with advanced cancer (Mercadante, Casuccio, Mangione, 2007). If surgical decompression or endoscopic interventions such as stent placement for upper and lower bowel obstructions are not feasible, then the need to control pain and other obstructive symptoms, including distension, nausea, and vomiting, becomes paramount (Davis, Hinshaw, 2006; Davis, Nouneh, 2001; Lussier, Portenoy, 2004). Various analgesics, anticholinergics, antisecretory agents, and antiemetics play important roles (Figure 30-1).

Figure 30-1 Pharmacologic management of malignant bowel obstruction. From Ripamonti, C., & Mercadante, S. (2004). How to use octreotide for malignant bowel obstruction. J Support Oncol, 2(4), 357-364.

The management of symptoms associated with MBO can be extremely challenging, and there is surprisingly very little well-designed research to guide treatment decisions (Mercadante, Casuccio, Mangione, 2007). International experts have begun to address this issue by reaching a consensus on two research protocols based on location of bowel obstruction, with the hope that well-designed studies will provide better direction for clinical treatment in the future (Anthony, Baron, Mercadante, 2007).

Opioid administration is appropriate to treat abdominal pain, even in the context of suspected bowel obstruction. Opioids will not hinder diagnosis and may facilitate physical examination (Davis, Hinshaw, 2006). If initial examination suggests that mechanical obstruction is not likely, treatment may include efforts to reduce drugs that can adversely influence bowel motility, including opioids. Adding nonopioids, such as ketorolac, during the acute phase may help to reduce the opioid dose; the lowest effective opioid dose should be given.

If constipation is contributing to the MBO, this must be addressed as part of the approach to symptom management. The first step is to exclude or treat fecal impaction. Unless obstruction is complete, treatment with laxatives should be initiated, and consideration should be given to treatment with an opioid antagonist with limited or no penetration into the CNS (Davis, Hinshaw, 2006). In the United States, methylnaltrexone (Relistor) is now approved for refractory opioid-induced constipation. Oral naloxone or another nonabsorbable opioid antagonist, such as alvimopan (Entereg), also can be considered for this purpose. (See Chapter 19 for more on these drugs for constipation and ileus.)

Other drugs are used to treat both the lower and upper GI symptoms associated with MBO. Metoclopramide (Reglan), for example, may be given to increase GI activity if there is no colic and the bowel is partially obstructed; however, metoclopramide should not be given if obstruction is complete as it can increase colic under those circumstances (Davis, Hinshaw, 2006; Mercadante, Ferrera, Villari, et al., 2004).

Clinical reviews and case series suggest that anticholinergic drugs, the somatostatin analogue octreotide (Sandostatin), and corticosteroids may be useful as adjuvant analgesics for palliative management of MBO (Mercadante, Casuccio, Mangione, 2007; Mercadante, Ferrera, Villari, et al., 2004; Ripamonti, Easson, Gerdes, et al., 2008; Weber, Zulian, 2009). The use of these drugs may also ameliorate nonpainful symptoms and minimize the need for chronic drainage using nasogastric or percutaneous catheters (Mercadante, Casuccio, Mangione, 2007). Following is a discussion of the adjuvant analgesics used to treat MBO.

Anticholinergic Drugs

Anticholinergics are used as antisecretory drugs (reduce water and salt secretion from the bowel lumen) in combination with analgesics and antiemetics to treat MBO (Mercadante, Casuccio, Mangione, 2007). In a small case series evaluating aggressive multimodal pharmacotherapy for MBO, 15 patients were consecutively treated with a combination of metoclopramide, octreotide, dexamethasone (Decadron and others), and an initial oral bolus of amidotrizoic acid, a hyperosmolar solution that promotes shifting of fluid into the bowel lumen, a goal of treatment (Mercadante, Ferrera, Villari, et al., 2004). Intestinal transit was improved between day 1 and day 5 of therapy, and this fast bowel recovery was attributed to the combination of propulsive and antisecretory agents that can act synergistically.

Scopolamine is a commonly used anticholinergic drug (Ripamonti, Mercadante, Groff, 2000) and is available as a transdermal patch, which is a convenient route of delivery in this setting (see Chapter 19 for more on the scopolamine patch). Problematic adverse effects include somnolence or drowsiness, confusion, loss of balance, headache, and dry mouth. These effects typically subside as patients adjust to the medication, but caution is recommended when the drug is used in older individuals who may be more sensitive to some of the effects. Adverse effects usually subside with patch removal. If CNS toxicity is problematic, a trial of an anticholinergic that is relatively less likely to pass through the blood-brain barrier, such as glycopyrrolate (Robinul), is reasonable. Along with antisecretory medications, parenteral hydration over 500 mL/day can help to reduce nausea and drowsiness (Ripamonti, Mercadante, Groff, 2000).

Octreotide

The somatostatin analog octreotide (Sandostatin) is desirable for rapid, aggressive management of MBO. It is a potent antisecretagogue that controls endogenous fluid losses and reduces gastric and intestinal secretion and bile flow (Mercadante, Casuccio, Mangione, 2007; Mercadante, Ferrera, Villari, et al., 2004). Octreotide has also been used to manage severe diarrhea caused by enterocolic fistula, high output jejunostomies or ileostomies, or secretory tumors of the GI tract. In a prospective randomized clinical trial, 17 patients with inoperable MBO and decompression nasogastric tube were randomized to receive octreotide 0.3 mg/day or scopolamine butylbromide 60 mg/day for 3 days through a continuous subcutaneous infusion (Ripamonti, Mercadante, Groff, et al., 2000). Pain relief was achieved in all patients, and there was no difference in the common adverse effect of dry mouth between groups.

Octreotide has a good safety profile but can be expensive. In some settings, however, the cost may be balanced by an excellent clinical response or avoidance of the costs associated with a GI drainage procedure. See Box 30-1 for an algorithm to guide the use of octreotide for bowel obstruction.

Corticosteroids

Corticosteroids have long been used to reduce inflammatory intestinal edema and promote intestinal transit, which can have immediate effects of reducing obstruction and promoting relief (Mercadante, Casuccio, Mangione, 2007). They act as antisecretory agents and are inexpensive and well-tolerated. The mode of action is unclear, and the most effective drug, dose, and dosing regimen have not been established. A broad range of doses have been described anecdotally. A systematic review demonstrated a trend toward IV dexamethasone doses of 6 to 16 mg/day for MBO (Feuer, Broadley, 1999). The previously discussed multimodal approach to aggressive treatment of MBO administered 12 mg/day of dexamethasone as an IV infusion (Mercadante, Ferrera, Villari, et al., 2004). Methylprednisolone (Depo-Medrol and others) has been administered in a dose range of 30 to 50 mg/day (Farr, 1990). In a small case series of 4 patients, subcutaneous dexamethasone doses of 4 to 40 mg/day or oral prednisone 50 mg/day along with analgesics and antiemetics were effective in managing symptoms associated with MBO (Weber, Zulian, 2009). The potential for complications during long-term therapy, including an increased risk of bowel perforation, may limit this approach to patients with life expectancies that are likely to be short (see Chapter 22 for more on corticosteroids and their adverse effects).

Conclusion

Bowel obstruction can occur in any patient with cancer, particularly in the advanced stages of the illness, and is considered a major complication. If surgical decompression or endoscopic interventions are not feasible, then the need to control pain and other obstructive symptoms is critical. Various analgesics, anticholinergics, antisecretory agents, and antiemetics play important roles in the treatment of this serious condition.