The Maitland Concept

Assessment, examination and treatment of movement impairments by passive movement

This chapter is a reprint from Twomey LT, Taylor JR (1987) Physical Therapy of the Low Back. Churchill Livingstone, New York. With permission from Elsevier.

It would be difficult for me as an individual who has been involved in the practice of manipulative physical therapy in Australia for the past three decades to objectively assess my particular contribution to the discipline. I therefore begin this chapter, by way of explanation and justification, with a relevant and pertinent quotation from Lance Twomey:

In my view, the Maitland approach to treatment differs from others, not in the mechanics of the technique, but rather in its approach to the patient and his particular problem. Your attention to detail in examination, treatment and response is unique in Physical Therapy, and I believe is worth spelling out in some detail:

• The development of your concepts of assessment and treatment

• Your insistence on sound foundations of basic biological knowledge

• The necessity for high levels of skill

• The evolution of the concepts. It did not ‘come’ to you fully developed, but is a living thing, developing and extending

• The necessity for detailed examination and for the examination/treatment/re-examination approach.

This area is well worth very considerable attention because, to me, it is the essence of ‘Maitland’.

Although the text of this chapter deals with ‘passive movement,’ it must be very clearly understood that the author does not believe that passive movement is the only form of treatment that will alleviate musculoskeletal disorders. What the chapter does set out to do is to provide a conceptual framework for treatment, which is considered by many to be unique. Thus, for want of a better expression, the particular approach to assessment, examination and treatment outlined in this chapter is described as ‘the Maitland Concept,’ and referred to hereafter as ‘the Concept.’

To portray all aspects of ‘the Concept’ by the written word alone is difficult since so much of it depends upon a particular clinical pattern of reasoning. The approach is not only methodical, but also involved and therefore difficult to describe adequately without clinical demonstration. The Maitland Concept requires open-mindedness, mental agility, and mental discipline linked with a logical and methodical process of assessing cause and effect. The central theme demands a positive personal commitment (empathy) to understand what the person (patient) is enduring. The key issues of ‘the Concept’ that require explanation are personal commitment, mode of thinking, techniques, examination, and assessment.

A personal commitment to the patient

All clinicians would claim that they have a high level of personal commitment to every patient. True as that may be, many areas of physical therapy require that a deeper commitment to certain therapeutic concepts be developed than is usual. Thus, the therapist must have a personal commitment to care, reassure, communicate, listen and inspire confidence.

All therapists must make a conscious effort (particularly during the first consultation) to gain the patient's confidence, trust and relaxed comfort in what may be at first an anxious experience. The achievement of this trusting relationship requires many skills, but it is essential if proper care is to be provided.

Within the first few minutes, the clinician must make the patient believe that he wants to know what the patient feels; not what his doctor or anyone else feels, but what the patient himself feels is the main issue. This approach immediately puts the patient at ease by showing that we are concerned about his symptoms and the effect they are having.

We must use the patient's terminology in our discussions: we must adapt our language (and jargon) to fit his; we must make our concern for his symptoms show in a way that matches the patient's feelings about the symptoms. In other words, we should adapt our approach to match the patient's mode of expression, not make or expect the patient to adapt to our personality and our knowledge. The patient also needs to be reassured of the belief and understanding of the therapist.

Communication is another skill that clinicians must learn to use effectively and appropriately. As far as personal commitment is concerned, this involves understanding the non-verbal as well as the verbal aspects of communication so that use can be made of it to further enhance the relationship between patient and clinician. Some people find that this is a very difficult skill to acquire, but however much effort is required to learn it, it must be learned and used.

Listening to the patient must be done in an open-minded and non-judgmental manner.

It is most important to accept the story the patient weaves, while at the same time being prepared to question him closely about it. Accepting and listening are very demanding skills, requiring a high level of objectivity.

It is a very sad thing to hear patients say that their doctor or physical therapist does not listen to them carefully enough or with enough sympathy, sensitivity, or attention to detail. The following quotation from The Age (1982), an Australian daily newspaper, sets out the demands of ‘listening’ very clearly:

Listening is itself, of course, an art: that is where it differs from merely hearing. Hearing is passive; listening is active. Hearing is involuntary; listening demands attention. Hearing is natural; listening is an acquired discipline.

Acceptance of the patient and his story is essential if trust between patient and clinician is to be established. We must accept and note the subtleties of his comments about his disorder even if they may sound peculiar. Expressed in another way, he and his symptoms are ‘innocent until proven guilty’ (that is, his report is true and reliable until found to be unreliable, biased or false). In this context, he needs to be guided to understand that his body can tell him things about his disorder and its behaviour that we (the clinicians) cannot know unless he expresses them. This relationship should inspire confidence and build trust between both parties.

This central core of the concept of total commitment must begin at the outset of the first consultation and carry through to the end of the total treatment period.

Other important aspects of communication will be discussed later under Examination and Assessment (and Chapter 3).

A mode of thinking: the primacy of clinical evidence

As qualified physical therapists, we have absorbed much scientific information and gained a great deal of clinical experience, both of which are essential for providing effective treatment. The ‘science’ of our discipline enables us to make diagnoses and apply the appropriate ‘art’ of our physical skill. However, the accepted theoretical basis of our profession is continually developing and changing. The gospel of yesterday becomes the heresay of tomorrow. It is essential that we remain open to new knowledge and open-minded in areas of uncertainty, so that inflexibility and tunnel vision do not result in a misapplication of our ‘art.’ Even with properly attested science applied in its right context, with precise information concerning the patient's symptoms and signs, a correct diagnosis is often difficult. Matching of the clinical findings to particular theories of anatomic, biomechanical, and pathologic knowledge, so as to attach a particular ‘label’ to the patient's condition, may not always be appropriate. Therapists must remain open-minded so that as treatment progresses, the patient is reassessed in relation to the evolution of the condition and the responses to treatment.

In summary, the scientific basis underlying the current range of diagnoses of disorders of the spine is incompletely understood. It is also changing rapidly with advances in knowledge and will continue to do so. In this context, the therapist may be sure of the clinical evidence from the patient's history and clinical signs, but should beware of the temptation to ‘fit the diagnosis’ to the inflexible and incomplete list of options currently available. The physical therapist must remain open-minded, not only at the initial consultation, but also as noting the changing responses of the patient during assessment and treatment. When the therapist is working in a relatively ‘uncharted area’ like human spinal disorders, one should not be influenced too much by the unreliable mass of inadequately understood biomechanics, symptomatology and pathology.

As a consequence of the above, a list of practical steps to follow has been drawn up. In the early era of its evolution, ‘the Maitland Concept’ had as its basis the following stages within a treatment:

1. Having assessed the effect of a patient's disorder, to perform a single treatment technique

2. To take careful note of what happens during the performance of the technique

3. Having completed the technique, to assess the effect of the technique on the patient's symptoms including movements

4. Having assessed steps 2 and 3, and taken into account the available theoretical knowledge, to plan the next treatment approach and repeat the cycle from step 1.

It becomes obvious that this sequence can only be useful and informative if both the clinical history taking and physical examinations have been accurate.

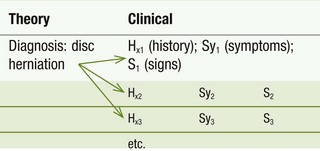

The actual pattern of the concept requires us to keep our thoughts in two separate but interdependent compartments: the theoretical framework; and the clinical assessment. An example may help to clarify these concepts. We know that a lumbar intervertebral disc can herniate and cause pain, which can be referred into the leg. However, there are many presentations that can result from such a herniation (Table 1.1).

The reverse is also true – a patient may have one set of symptoms for which more than one diagnostic title can be applied (MacNab 1971; Table 1.2).

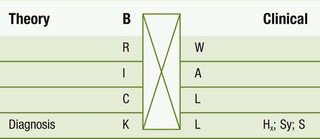

Because of the circumstances shown in Tables 1.1 and 1.2, it is obvious that it is not always possible to have a precise (biomedical) diagnosis for every patient treated. The more accurate and complete our theoretical framework, the more appropriate will be our treatment. If the theoretical framework is faulty or deficient (as most are admitted to be), a full and accurate understanding of the patient's disorder may be impossible. The therapist's humility and open-mindedness are therefore essential, and inappropriate diagnostic labels must not be attached to a patient prematurely. The theoretical and clinical components must, however, influence one another. With this in mind, I have developed an approach separating theoretical knowledge from clinical information by what I have called the symbolic, permeable brick wall (Table 1.3). This serves to separate theory and practice, and to allow each to occupy (although not exclusively) its own compartment. That is, information from one side is able to filter through to the other side. In this way, theoretical concepts influence examination and treatment, while examination and treatment lead one back to a reconsideration of theoretical premises.

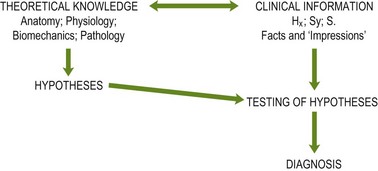

Using this mode of thinking, the brick-wall concept frees the clinician's mind from prejudice, allowing the therapist to ponder the possible reasons for a patient's disorder; to speculate, consider a hypothesis and discuss with others the possibilities regarding other diagnoses without anyone really knowing all the answers, yet all having a clear understanding of the patient's symptoms and related signs (Fig. 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Flowchart demonstrating relationships and contexts for theoretical and clinical knowledge with related hypotheses. (Hx = history; Sy = symptoms; S = signs.) Reproduced from Twomey LT, Taylor JR, eds (1988) Physical therapy of the low back, p. 140, Churchill Livingstone with permission from Elsevier.

This mode of thinking requires the use of accurate language, whereas inaccurate use of words betrays faulty logic. The way in which an individual makes a statement provides the listener with an idea both of the way that person is thinking and of the frame of reference for the statement.

A simple example may help to make this point clear. Imagine a clinician presenting a patient at a clinical seminar, and on request the patient demonstrates his area of pain. During the ensuing discussion, the clinician may refer to the patient's pain as ‘sacroiliac pain.’ This is a wrong choice of words. To be true to ‘the Concept’ we have outlined, of keeping clinical information and theoretical interpretations separate, one should describe the pain simply as a ‘pain in the sacroiliac area.’ It would be an unjustified assumption to suggest that pathology in the sacroiliac joint was the source of pain, but the former description above could be interpreted in this way. On the other hand, describing the pain as ‘in the sacroiliac area’ indicates that we are considering other possible sites of origin for the pain besides the sacroiliac joints, thereby keeping our diagnostic options open until we have more evidence. This is an essential element to ‘the Concept.’ Some readers may believe that attention to this kind of detail is unnecessary and pedantic. Quite the opposite is true. The correct and careful choice of words indicates a discipline of mind and an absence of prejudice, which influence all our diagnostic procedures including the whole process of examination, treatment and interpretation of the patient's response.

A clinician's written record of a patient's examination and treatment findings also show clearly whether the therapist's thinking processes are right or wrong. A genuine scientific approach involves logical thinking, vertical and lateral thinking, and inductive and deductive reasoning. It requires a mind that is uncluttered by confused and unproven theory, which is at the same time able to use proven facts, and has the critical ability to distinguish between well-attested facts and unsubstantiated opinions. It requires a mind that is honest, methodical, and self-critical. It also requires a mind that has the widest possible scope in the areas of improvisation and innovation.

Techniques

Many physical therapy clinicians are continually seeking new techniques of joint mobilization. When they hear a new name or when a new author has written a book on manipulation, they attempt to acquire the ‘new’ technical skills, and immediately apply them. In reality, the techniques are of secondary importance. Of course, if they are poorly performed or misapplied, treatment may fail and the therapist may lose confidence in the techniques. However, in my view there are many acceptable techniques each of which can be modified to suit a patient's disorder and the clinician's style and physique. Accordingly, I consider that there is no absolute set of techniques that can belong or be attributed to any one person. There should be no limit to the selection of technique: the biomechanically based techniques of Kaltenborn; the ‘shift’ techniques of McKenzie; the combined-movements technique of Edwards; the osteopathic and chiropractic technique; the Cyriax techniques; the Stoddard technique; the bonesetters' techniques; the Maigne techniques; and the Mennell techniques. All of these techniques are of the present era. Every experienced practitioner must feel totally free to make use of any of them. The most important consideration is that the technique chosen be appropriate to the particular patient or situation and that its effect should be carefully and continually assessed.

Techniques of management

Within the broad concept of this chapter, there are certain techniques of management that are continually used, but are not described by other authors. These techniques are as follows.

When treating very painful disorders passive-treatment movements can be used in an oscillatory fashion (‘surface stirring’ as described by Maitland 1985) but with two important provisos:

1. The oscillatory movement is performed without the patient experiencing any pain whatsoever, nor even any discomfort

2. The movement is performed only in that part of the range of movement where there is no resistance, i.e. where there is no stiffness or muscle spasm restricting the oscillations.

One may question how a pain-free oscillatory movement, which avoids every attempt to stretch structures, can produce any improvement in a patient's symptoms. A scientific answer to this question has been suggested (Maitland 1985) but there is a far more important clinical conclusion. It has been repeatedly shown clinically that such a technique does consistently produce a measurable improvement in range of movement with reduction in pain and disability and no demonstrable harmful effects. This demonstrates that the treatment is clinically and therefore ‘scientifically,’ correct even though an adequate theoretical explanation for its effectiveness may not yet be available. Reliable and repeated demonstration of effectiveness must validate a treatment method. To know how the method achieves the result is a theoretical problem for science to solve. The ‘scientific’ examination must match the primary clinical observation, the latter being the aspect of which we can be sure.

This example demonstrates once more how this mode of thinking so essential to ‘the Concept’ is so necessary for the further development of treatment methods. Without this mode of thinking we would never have found that passive-movement treatment procedures can successfully promote union in non-uniting fractures (McNair & Maitland 1983, McNair 1985).

Oscillatory movements as an important component of passive movement are referred to above in relation to the treatment of pain. There is another treatment procedure that requires oscillatory movement to be effective. This is related to the intermittent stretching of ligamentous and capsular structures. There are clearly defined areas of application for this treatment, which are described elsewhere (Maitland 1985).

There are occasions when a passive treatment movement needs to be performed with the opposing joint surfaces compressed together (Maitland 1980).Without the compression component, the technique would fail to produce any improvement in the patient's symptoms.

Utilizing the movements and positions by which a patient is able to reproduce his symptoms as an initial mandatory test is essential to ‘the Concept.’ This tactic, like the formalized examination of combined movements (the original contribution in cooperation with Edwards 1979) is very special to ‘the Concept.’

Although it is frequently recognized that straight-leg raising can be used as a treatment technique for low lumbar disorders, it is not widely appreciated that the technique may be made more effective by using straight-leg raising in the ‘Slump test’ position (Maitland 1979). In the same slumped position, the neck flexion component of the position may be effectively utilized when such movement reproduces a patient's low back pain.

‘Accessory’ movements produced by applying alternating pressure on palpable parts of the vertebrae are also very important in terms of techniques and ‘the Maitland Concept.’ Any treatment concept that does not include such techniques is missing a critical link essential to a full understanding of the effects of manipulation on patients with low lumbar disorders.

It is important to remember that there is no dogma or clear set of rules that can be applied to the selection and use of passive-movement techniques; the choice is open ended. A technique is the brainchild of ingenuity. ‘The achievements are limited to the extent of one’s lateral and logical thinking’ (Hunkin 1985).

Examination

The care, precision and scope of examination required by those using this ‘concept’ are greater and more demanding than other clinical methods I have observed. ‘The Concept’s’ demands differ from those of other methods in many respects.

The history taking and examination demand a total commitment to understanding what the patient is suffering and the effects of the pain and disability on the patient. Naturally, one is also continually attempting to understand the cause of the disorder (the theoretical compartment of ‘the Concept’).

Examination must include a sensitive elucidation of the person's symptoms in relation to:

1. Precise area(s) indicated on the surface of the body

2. The depth at which symptoms are experienced

3. Whether there is more than one site of pain, or whether multiple sites overlap or are separate

4. Changes in the symptoms in response to movements or differences in joint positions in different regions of the body.

The next important and unique part of the examination is for the patient to reenact the movement that best reveals his disorder or, if applicable, to reenact the movement that produced the injury. The function or movement is then analyzed by breaking it into components in order to make clinical sense of particular joint-movement pain responses, which are applicable to his complaint.

The routine examination of physiologic movements performed with a degree of precision rarely utilized by other practitioners. If the person's disorder is an ‘end-of-range’ type of problem, the details of the movement examination required are:

1. At what point in the range are the symptoms first experienced; how do they vary with continuation of the movement; and in what manner do the symptoms behave during the symptomatic range?

2. In the same way and with the same degree of precision, how does muscle spasm or resistance vary during the symptomatic range?

3. Finally, what is the relationship of the symptoms (a) to the resistance or spasm (motor responses); and (b) during that same movement? There may be no relationship whatsoever, in which case, for example, the stiffness is relatively unimportant. However, if the behaviour of the symptoms matches the behaviour of the stiffness, both should improve in parallel during treatment.

An effective method of recording the findings of all components of a movement disorder is to depict them in a ‘movement diagram.’ These also are an innovative part of ‘the Concept.’ The use of movement diagrams facilitates demonstration of changes in the patient's condition in a more precise and objective manner. They are discussed at length in the Appendix 4.

If the patient's disorder is a ‘pain through range’ type of problem, the details of the movement examination required are:

1. At what point in the range does discomfort or pain first increase?

2. How do the symptoms behave if movement is taken a short distance beyond the onset of discomfort? Does intensity markedly increase or is the area of referred pain extended?

3. Is the movement a normal physiological movement in the available range or is it protected by muscle spasm or stiffness? Opposing the abnormal movement and noting any change in the symptomatic response compared with entry 2 is performed to assess its relevance to the course of treatment.

Palpatory techniques

The accessory movements are tested by palpation techniques and seek the same amount and type of information as described above. They are tested in a variety of different joint positions. The three main positions are:

1. The neutral mid-range position for each available movement i.e. midway between flexion/extension, rotation left and right, lateral flexion left and right and distraction/compression

2. The joint is in a ‘loose-packed position’ (MacConaill & Basmajian 1969) at the particular position where the person's symptoms begin, or begin to increase

These palpatory techniques of examination and treatment have been peculiar to this ‘concept’ from its beginnings. As well as seeking symptomatic responses to the movement as described above, the palpation is also used to assess positional anomalies and soft-tissue abnormalities, which are at least as critical to ‘the Concept’ as the movement tests.

The testing of physiologic and accessory movement can be combined in a variety of ways in an endeavour to find the comparable movement sign most closely related to the person's disorder. Edwards (1983) originally described a formal method of investigating symptomatic responses and treating appropriate patients using ‘combined movement’ techniques. In addition, joint surfaces may be compressed, both as a prolonged, sustained firm pressure and as an adjunct to physiologic and accessory movement. These are two further examples of examination developed as part of ‘the Maitland Concept.’

Differentiation tests are perfect examples of physical examination procedures that demonstrate the mode of thinking so basic to ‘the Maitland Concept.’ When any group of movements reproduces symptoms, ‘the Concept’ requires a logical and thoughtful analysis to establish which movement of which joint is affected. The simplest example of this is passive supination of the hand and forearm, which when held in a stretched position reproduces the patient's symptoms. The stages of this test are as follows:

1. Hold the fully supinated hand/forearm in the position that is known to reproduce the pain

2. Hold the hand stationary and pronate the distal radio-ulnar joint 2° or 3°

3. If the pain arises from the wrist, the pain will increase because in pronating the distal radio-ulnar joint, added supination stress is applied at the radiocarpal and midcarpal joints

4. While in the position listed in entry 1, again hold the hand stationary, but this time increase supination of the distal radio-ulnar joint. This decreases the supination stretch at the wrist joints and will reduce any pain arising from the wrist. However, if the distal radio-ulnar joint is the source of pain, the increased supination stretch will cause the pain to increase.

All types of differentiation tests require the same logically ordered procedure. These functional tests follow the same logic as the subjective modes of assessment described at the beginning of this chapter and provide additional evidence leading to accurate diagnosis.

Assessment

In the last few years it would appear that physical therapists have discovered a new ‘skill,’ with the lofty title of ‘problem solving.’ This is, and always should be, the key part of all physical therapy treatment. Being able to solve the diagnostic and therapeutic problems and thus relieve the patient of his complaint is just what physical therapists are trained to do. For many years, manipulative physical therapy has been rightly classed as empirical treatment. However, since manipulative physical therapists began to be more strongly involved in problem-solving skills, treatment has become less empirical and more logical. On the basis that the pathology remains unknown in the majority of cases and the effects of the treatment on the tissues (as opposed to symptoms) are unknown, the treatment remains empirical in form. This is true with almost all of the medical science. Nevertheless, the approach to the patient and to physical treatment has become more logical and scientific within ‘the Maitland Concept.’

Minds existed before computers were developed and manipulative therapists are trained to sort out and access ‘input’ so that appropriate and logical ‘output’ can be produced. Appropriate problem-solving logic will relate clinical findings to pathology and mechanical disorders. This process of ‘sorting out’ we have called assessment and assessment is the key to successful, appropriate, manipulative treatment, which, because of the reliability of its careful and logical approach, should lead to better and better treatment for our patients.

Assessment is used in six different situations:

1. Analytical assessment at a first consultation

3. Reassessment during every treatment session proving the efficacy of a technique at a particular stage of treatment

Analytical assessment

A first consultation requires skills in many areas, but the goals require decisions and judgments from the following five areas:

3. The degree of stability of the disorder at the time of treatment

Without communication and an atmosphere of trust, the answers to the different assessment procedures (1–5) cannot be reliably determined. By using one's own frame of reference and endeavouring to understand the patient's frame of reference, the characteristics of the patient can be judged. By making use of non-verbal skills, picking out key words or phrases, knowing what type of information to listen for and recognizing and using ‘immediate-automatic-response’ questions (all described later), accurate information can be gained at this first consultation. The physical examination is discussed under the heading, Examination.

Pretreatment assessment

Each treatment session begins with a specific kind of assessment of the effect of the previous session on the patient's disorder (its symptoms and changes in movement). Since the first consultation includes both examination and treatment of movements, the assessment at the second treatment session will not be as useful for therapy as it will be at the following treatment sessions.

When the patient attends subsequent treatment sessions, it is necessary to make both subjective and physical assessments, i.e. subjective in terms of how they feel; objective in terms of what changes can be found in quality and range of movement and in related pain response. When dealing with the subjective side of assessment, it is important to seek spontaneous comments. It is wrong to ask, ‘How did it feel this morning when you got out of bed, compared with how it used to feel?’ The start should be ‘How have you been?’ or some such general question, allowing the patient to provide some information that seems most important to him. This information may be more valuable because of its spontaneous nature.

Another important aspect of the subjective assessment is that statements of fact made by a patient must always be converted to comparisons to previous statements. Having made the subjective assessment, the comparative statement should be the first item recorded on the patient's case notes. And it must be recorded as a comparison-quotation of his opinion of the effect of treatment. (The second record in the case notes is the comparative changes determined by the objective movement tests.) To attain this subjective assessment, communication skills are of paramount importance. There are many components that make up the skill, but two are of particular importance:

1. Key words or key phrases. Having asked the question, ‘How has it been?’ a patient may respond in a very general and uninformative way. However, during his statements he may include, for example, the word ‘Monday.’ Latch on to Monday, because Monday meant something to him. Find out what it was and use it. ‘What is it that happened on Monday? Why did you say Monday?’

2. A patient frequently says things that demand an immediate-automatic-response question. As a response to the opening question given above, the patient may respond by saying, ‘I'm feeling better.' The immediate-automatic-response to that statement, even before he has had a chance to take breath and say anything else, is, ‘better than what?’ or ‘better than when?’ It may be that after treatment he was worse and that he is better than he was then, but that he is not better than he was before the treatment.

One aspect of the previous treatment is that it (often intentionally) provokes a degree of discomfort. This will produce soreness, but if the patient says he has more pain, the clinician needs to determine if it is treatment-soreness or disorder-soreness. For example, a patient may have pain radiating across his lower back and treatment involves pushing on his lumbar spine. He is asked to stand up and is asked, ‘How do you feel now compared with before I was pushing on your back?’ He may say, ‘it feels pretty sore.’ He is then asked, ‘Where does it feel sore?’ If he answers, ‘It’s sore in the center’, the clinician may consider that it is likely to be treatment pain. But if he answers, ‘It’s sore across my back’ then the clinician may conclude that it is disorder pain. If it were treatment soreness it would only be felt where the pressure had been applied. If the soreness spreads across his back, the treatment technique must have disturbed the disorder.

In making subjective assessments, a process is included of educating the patient in how to reflect. If a patient is a very good witness, the answers to questions are very clear, but if the patient is not a good witness, then subjective assessment becomes difficult. Patients should learn to understand what the clinician needs to know. At the end of the first consultation, patients need to be instructed in how important it is for them to take notice of any changes in their symptoms. They should report all changes; even ones they believe are trivial. The clinician should explain, ‘Nothing is too trivial. You can’t tell me too much; if you leave out observations, which you believe to be unimportant, this may cause me to make wrong treatment judgments.’ People need to be reassured that they are not complaining, they are informing. Under circumstances when a patient will not be seen for some days or if full and apparently trivial detail is needed, they should be asked to write down the details. There has been criticism that asking patients to write things down makes them become hypochondriacs. This is a wrong assessment in my experience, as the exercise provides information that might otherwise never be obtained.

There are four specific times when changes in the patient's symptoms can indicate the effect of treatment. They are as follows:

1. Immediately after treatment. The question can be asked, ‘How did you feel when you walked out of here last time compared with when you walked in?’ A patient can feel much improved immediately after treatment yet experience exacerbation of symptoms one or two hours later. Any improvement that does not last longer than one hour indicates that the effect of the treatment was only palliative. Improvement that lasts more than four hours indicates a change related to treatment.

2. Four hours after treatment. The time interval of four hours is an arbitrary time and could be any time from three to six hours. It is a ‘threshold’ time interval beyond which any improvement or examination can be taken to indicate the success or failure of the treatment. Similarly, if a patient's syndrome is exacerbated by treatment, the patient will be aware of it at about this time.

3. The evening of the treatment. The evening of the day of treatment provides information in regard to how well any improvement from treatment has been sustained. Similarly, an exacerbation immediately following treatment may have further increased by evening. This is unfavourable. Conversely, if the exacerbation has decreased, it is then necessary to know whether it decreased to its pretreatment level or decreased to a level that was better than before that day's treatment. This would be a very favourable response, clearly showing that the treatment had alleviated the original disorder.

4. On rising the next morning. This is probably the most informative time of all for signalling a general improvement. A patient may have no noticeable change in his symptoms on the day or night of the treatment session, but may notice that on getting out of bed the next morning his usual lower back stiffness and pain are less, or that they may pass off more quickly than usual. Even at this time span, any changes can be attributed to treatment. However, changes that are noticed during the day after treatment, or on getting out of bed the second morning after treatment, are far less likely to be as a result of treatment. Nevertheless, the patient should be questioned in depth to ascertain what reasons exist, other than treatment, to which the changes might be attributed.

Because accurate assessment is so vitally and closely related to treatment response, each treatment session must be organized in such a way that the assessments are not confused by changes in the treatment. For example, if a patient has a disorder that is proving very difficult to help and at the eighth treatment session he reports that he feels there may have been some slight favourable change from the last treatment, the clinician has no alternative in planning the eighth treatment session. In the eighth treatment, that which was done at the seventh must be repeated in exactly the same manner in every respect. To do otherwise could render the assessment at the ninth treatment confusing. If the seventh treatment is repeated at the eighth session, there is nothing that the patient can say or demonstrate that can confuse the effect attributable to that treatment. If there was an improvement between the seventh and the eighth treatment (and the eighth treatment was an identical repetition of the seventh treatment), yet no improvement between the eighth treatment and the ninth treatment time, the improvement between treatments seven and eight could not have been due to treatment.

There is another instance when the clinician must recognize that there can be no choice as to what the eighth treatment must be. If there had been no improvement with the first six treatments and at the seventh treatment session a totally new technique was used, the patient may report at the eighth session that there had been a surprisingly marked improvement in symptoms. It may be that this unexpected improvement was due to treatment or it may have been due to some other unknown reason. There is only one way that the answer can be found – the treatment session should consist of no treatment techniques at all. Objective assessment may be made but no treatment techniques should be performed. At the ninth session, if the patient's symptoms have worsened considerably, the treatment cannot be implicated in the cause because none had been administered. The clinician can then repeat the seventh treatment and see if the dramatic improvement is achieved again. If it is, then the improvement is highly likely to have been due to that treatment.

Whatever is done at one treatment session is done in such a way that when the patient comes back the next time, the assessment cannot be confusing.

Another example of a different kind is that a patient may say at each treatment session that he is ‘the same,’ yet assessment of his movement signs indicates that they are improving in a satisfactory manner and therefore that one would expect an improvement in his symptoms. To clarify this discrepancy, specific questions must be asked. It may be that he considers he is ‘the same’ because his back is still just as stiff and painful on first getting out of bed in the morning as it was at the outset of treatment. The specific questioning may divulge that he now has no problems with sitting and that he can now walk up and down the stairs at work without pain. Although his sitting, climbing and descending stairs have improved, his symptoms on getting out of bed are the same and this explains his statement of being ‘the same.’ The objective movement tests will have improved in parallel with his sitting and stair-climbing improvements.

Assessment during every treatment session

Proving the value or failure of a technique applied through a treatment session is imperative. Assessment (problem solving) should be part of all aspects of physical therapy. In this chapter it is related to passive movement. There are four kinds of assessment and probably the one that most people think of first is the one in which the clinician is trying to prove the value of a technique that is being performed on a patient.

Proving the value of a technique

Before even choosing which technique to use, it is necessary to know what symptoms the patient has and how his movements are affected in terms of both range and the pain response during the movement. Selection of a treatment technique depends partly on knowing what that technique should achieve while it is being performed. In other words, is it the aim to provoke discomfort and, if so, how much ‘hurt’ is permissible? It is also necessary to have an expectation of what the technique should achieve after it has been performed.

With these considerations in mind, it is necessary to keep modifying the treatment technique until it achieves the expected goal during its performance. Assuming that this is achieved and that the technique has been performed for the necessary length of time, the patient is then asked to stand, during which time he is watched to see if there are any nuances that may provide a clue as to how his back is feeling. The first thing is to then ask him is, ‘How do you feel now compared with when you were standing there before the technique?’ It is then necessary to clarify any doubts concerning the interpretation of what he says he is feeling. It is important to understand what the patient means to say if the subjective effect of the technique is to be determined usefully.

Having subjectively assessed the effect of the technique, it is then necessary to reexamine the major movements that were faulty, to compare them with their state before the technique. An important aspect of checking and rechecking the movements is that there may be more than one component to the patient's problem. For example, a man may have back pain, hip pain and vertebral-canal pain. Each of these may contribute to the symptoms in his lower leg. On reassessing him after a technique, it is necessary to assess at least one separate movement for each of the components, so it can be determined what the technique has achieved for each component. It is still necessary to check all of the components even if it is expected that a change will only be effected in one of the components. Having completed all of these comparison assessments, the effect of that technique at that particular stage of the disorder is now recorded in detail.

Progressive assessment

At each treatment session the symptoms and signs are assessed for changes for their relation to the previous treatment session and to ‘extracurricular’ activities. At about each fourth treatment session a subjective assessment is made, comparing how the patient feels today with how he felt four treatments previously. The purpose of this progressive assessment is to clarify and confirm the treatment by assessment of the treatment response. One is often surprised by the patient's reply to a question, ‘How do you feel now compared with 10 days (i.e. four treatments) ago?’ The goal is to keep the treatment-by-treatments assessment in the right perspective in relation to the patient's original disorder.

Retrospective assessment

The first kind of retrospective assessment is that made routinely at each group of three or four treatment sessions when the patient's symptoms and signs are compared with before treatment began, as described above.

A second kind of retrospective assessment is made toward the end of treatment when the considerations relate to a final assessment. This means that the clinician is determining:

1. Whether treatment should be continued

2. Whether spontaneous recovery is occurring

3. Whether other medical treatments or investigations are required

4. Whether medical components of the disorder are preventing full recovery

5. What the patient's future in terms of prognosis is likely to be?

A third kind of retrospective assessment is made when the patient's disorder has not continued to improve over the last few treatment sessions. Under these circumstances, it is the subjective assessment that requires the greatest skill and its findings are far more important than the assessment of the objective-movement tests. The clinician needs to know what specific information to look for. This is not a facetious remark, since it is the most common area where mistakes are made, thereby ruining any value in the assessment. The kinds of question the clinician should ask are as follows:

‘During the whole time of treatment, is there anything I have done that has made you worse?’

‘Of the things I have done to you, is there any one particular thing (or more) that you feel has helped you?’

‘Does your body tell you anything about what it would like to have done to it to make it start improving?’

‘Does your body tell you anything about what it would like to have done to it to make it start improving the treatment’s effect?’

‘Do your symptoms tell you that it might be a good plan to stop treatment for, say, two weeks after which a further assessment and decision could be made?’

And so the probing interrogation continues until two or three positive answers emerge, which will guide the further measures that should be taken. The questions are the kind that involve the patient in making decisions and that guide the clinician in making a final decision regarding treatment.

There is a fourth kind of retrospective assessment. If treatment is still producing improvement but its rate is less than anticipated, a good plan is to stop treatment for two weeks and to then reassess the situation. If the patient has improved over the two-week period, it is necessary to know whether the improvement has been a day-by-day affair thus indicating a degree of spontaneous improvement. If the improvement only occurred for the first two days after the last treatment, then it would seem that the last treatment session was of value and that a further three or four treatments should be given followed by another 2-week break and reassessment.

Final analytical assessment

When treatment has achieved all it can, the clinician needs to make an assessment in relation to the possibility of recurrence, the effectiveness of any prophylactic measures, the suggestion of any medical measures that can be carried out and, finally, an assessment of the percentage of remaining disability. The answers to these matters are to be found by analyzing all the information derived from:

2. The behaviour of the disorder throughout treatment

3. The details derived from retrospective assessments

4. The state of affairs at the end of treatment, taking into account the subjective and objective changes.

This final analytical assessment is made easier as each year a clinician's work builds up experience. It is necessary for this experience to be based on a self-critical approach and on analysis of the results, with the reasons for these results.

Conclusion

The question has often been asked, ‘How did this method of treatment evolve?’ The attributes necessary to succeed in this treatment method are an analytical, self-critical mind and a talent for improvisation.

With this as a basis, the next step is to learn to understand how a patient's disorder affects him. Coupled with this is the need to have sound reasons for trying a particular technique and then the patience to assess its effect. In ‘the Maitland Concept,’ over the years this has developed into a complex interrelated series of assessments as described in the body of this text.

References

Edwards, BC. Combined movements of the lumbar spine: examination and clinical significance. Aust J Physiother. 1979;25:147.

Edwards, BC, Movement patterns. 1983.

Hunkin K: 1985. Unpublished publication.

MacConaill, MA, Basmajian, SV. Muscles and movements. Baltimore: Waverley Press; 1969.

MacNab, I. Negative disc exploration: an analysis of the causes of nerve root involvement in 68 patients. J Bone Joint Surg. 1971;53A:891.

McNair, JFS, Maitland, GD, The role of passive mobilization in the treatment of a non-uniting fracture site – a case study. 1983.

McNair, JFS, Non-uniting fractures management by manual passive mobilization. 1985.

Maitland, GD. Negative disc exploration: positive canal signs. Aust J Physiother. 1979;25:6.

Maitland, GD. The hypothesis of adding compression when examining and treating synovial joints. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1980;2:7.

Maitland, GD. Passive movement techniques for intra-articular and periarticular disorders. Aust J Physiother. 1985;31:3.