Communication and the therapeutic relationship

Introduction

As described in former editions of Maitland's work (Maitland 1986, 1991), well-developed communication skills are essential elements of the physiotherapy process. They serve several purposes:

• To aid the process of information-gathering with regard to physiotherapy diagnosis, treatment planning and reassessment of results

• To possibly help develop a deeper understanding of the patient's thoughts, beliefs and feelings with regard to the problem. This information assists in the assessment of psychosocial aspects which may hinder or enhance full recovery of movement functions

• Empathic communication with the above-mentioned objectives also enhances the development of a therapeutic relationship.

Therapeutic relationship

Based on changing insights on pain as a multidimensional experience, the therapeutic relationship is considered to have increasing relevance in physiotherapy literature. It is debated that interpersonal communication, next to academic knowledge and technical expertise, constitutes one of the cornerstones of the art of health professions (Gartland 1984a). Furthermore, it is considered that the physiotherapy process depends strongly on the interaction between the physiotherapist and the patient, in which the relationship may be therapeutic in itself (Stone 1991). The World Confederation of Physical Therapy (WCPT 1999) describes the interaction between patient and physiotherapist as an integral part of physiotherapy, which aims to achieve a mutual understanding. Interaction is seen as a ‘pre-requisite for a positive change in body awareness and movement behaviours that may promote health and wellbeing’ (WCPT 1999, p. 9). The physiotherapist may be seen as a treatment modality next to the physical agents applied (Charmann 1989), in which all the physiotherapist's mental, social, emotional, spiritual and physical resources need to be used to establish the best possible helping relationship (Pratt 1989). It is recommended that every health professional establishes a therapeutic relationship with a client-centred approach, with empathy, unconditional regard and genuineness (Rogers 1980). In particular, empathy and forms of self-disclosure by the therapist are seen as important elements of a healing environment (Schwartzberg 1992) in which markedly empathic understanding may support patients to disclose their feelings and thoughts regarding the problem for which they are seeking the help of a clinician (Merry & Lusty 1993).

The physiotherapist's role in the therapeutic relationship

It is recognized that within the therapeutic process a physiotherapist may take on a number of different roles:

In relation to counselling it is argued that physiotherapists may often be involved in counselling situations, without being fully aware of it (Lawler 1988). The use of counselling skills may be considered as distinct from acting as a counsellor, the latter being a function of psychologists, social workers or psychiatrists (Burnard 1994). However, it is recommended that every clinician learns to use counselling skills within their framework of clinical practice (Horton & Bayne 1998).

It appears that over the years of clinical experience physiotherapists view their roles with regard to patients differently. As junior physiotherapists they may consider themselves more in an expert, curative role, providing treatment from the perspective of their professional expertise, while more senior physiotherapists seem to endeavour to meet patients' preferences of therapy (Mead 2000) and engage more in social interactions with the patients (Jensen et al. 1990), thus considering themselves more in the role of a guide or counsellor.

The positive effects of a therapeutic relationship are seen in:

• Actively integrating a patient in the rehabilitation process (Mattingly & Gillette 1991)

• Patient empowerment (Klaber Moffet & Richardson 1997)

• Compliance with advice, instructions and exercises (Sluys et al. 1993)

• Outcomes of treatment, such as increased self-efficacy beliefs (Klaber Moffet & Richardson 1997)

• Building up trust to reveal information which the patient may consider as discrediting (French 1988)

• Trust to try certain fearful activities again or re-establishing self-confidence and wellbeing (Gartland 1984b).

Notwithstanding this, the therapeutic relationship is often seen as a non-specific effect of treatment, meeting prejudice in research and being labelled as a placebo effect, which needs to be avoided (Van der Linden 1998). However, it is argued that each form of treatment in medicine knows placebo responses, which need to be investigated more deeply and used positively in therapeutic settings (Wall 1994). These placebo effects seem to be determined more by characteristics of the clinician than by features of the patients, such as friendliness, reassurance, trustworthiness, showing concern, demonstrating expertise and the ability to establish a therapeutic relationship (Grant 1994).

Research and the therapeutic relationship

In spite of an increasing number of publications, relatively few physiotherapy texts seem to deal explicitly with the therapeutic relationship when compared with occupational therapy or nursing literature. A CINAHL database search over the period 1989–2012 under the key words ‘patient–therapist relationship AND physical therapy’ and ‘therapeutic relationship AND physical therapy’ was performed: 14 entries (from a total of 1021 entries dealing with ‘patient–therapist relationship’), and seven entries (compared with 150 entries under the heading ‘therapeutic relationship’) respectively, were published in physiotherapy-related journals. This notion is confirmed by Roberts and Bucksey (2007). In an observational study they investigated the content and prevalence of communication between therapists and patients with back pain. They identified verbal and non-verbal behaviours as observable tools for observation and video analysis, but they conclude that communication is an extremely important element of the therapeutic relationship, but underexplored in scientific research. Nevertheless, the World Confederation of Physical Therapy in the Description of Physical Therapy (1999) declared the interaction with the patient as an integral part of physiotherapy practice, and the Chartered Society of Physiotherapy in Great Britain, in the third edition of its Standards of Physiotherapy Practice, emphasizes the relevance of a therapeutic relationship and communication as key components of the therapeutic process (Mead 2000). These viewpoints seem to be shared by the majority of physiotherapists in Sweden. In a study with primary qualitative research and consequently a questionnaire with Likert-type answers, it was concluded that the majority of physiotherapists attributed many effects of the treatment to the therapeutic relationship and the patient's own resources rather than to the effects of treatment techniques alone (Stenmar & Nordholm 1997).

It is recommended that within a therapeutic relationship patients need to be treated as equals and experts in their own right, and that their reports on pain need to be believed and acted upon. Opportunities need to be provided to communicate, to talk with and listen to the patients about their problems, needs and experiences. In addition, independence needs to be encouraged in choosing personal treatment goals and interventions within a process of setting goals with rather than for a patient (Mead 2000).

Various studies have been undertaken with elements of the therapeutic relationship among patients and physiotherapists. In various surveys of patients it was concluded that patients appreciated positive regard and willingness to give information next to professional skills and expertise (Kerssens et al. 1995), communication skills and explanations on their level of thinking about their problem, and treatment goals and effects as well as confidentiality with the information given (de Haan et al. 1995). In a qualitative study on elements of quality of physiotherapy practice, patient groups regarded the ability to motivate people and educational capacities as essential aspects (Sim 1996).

Besley et al. (2011) identified in a literature study key features of a therapeutic relationship, which included: patient expectations with regard to the therapeutic process and outcomes; personalized therapy regarding acceptance in spite of cultural differences and holistic practice; partnership, relating to trust, mutual respect, knowledge exchange, power balance and active involvement of the patient; physiotherapist roles and responsibilities, including the activation of patients' own resources, being a motivator and educator and the professional manner of the therapist; congruence between the therapist and patient, relating to goals, problem identification and treatment; communication, in particular non-verbal communication, active listening and visual aids; relationship/relational aspects, encompassing friendliness, empathy, caring, warmth and faith that the therapist believes the patient; and influencing factors, as waiting time, quick access to the therapist, having enough time allocated to the sessions, knowledge and skills of therapist.

Hall et al. (2010), in another review on the influence of the therapeutic relationship on treatment outcomes, concluded that particularly beneficial effects could be found in treatment compliance, depressive symptoms, treatment satisfaction and physical function.

The therapeutic relationship and physiotherapy education and practice

Indications exist that various dimensions of the therapeutic relationship are neglected in physiotherapy education and practice. In a qualitative study in Great Britain among eight physiotherapists offering low back pain education it was concluded that only one participant followed a patient-centred approach, with active listening to the needs of the patients, while the remaining physiotherapists followed a therapist-centred approach (Trede 2000). In a survey among physiotherapists in The Netherlands it was concluded that almost all physiotherapists felt that insufficient communication skills training had been given during their undergraduate education (Chin et al. 1993). Furthermore, in a qualitative study the participants felt that aspects of dealing with intimacy during daily clinical encounters between patients and physiotherapists have been neglected (Wiegant 1993). In a qualitative study among clinical instructors of undergraduate physiotherapy students it was noted that the clinical supervisors preferred to give feedback to the students on technical skills rather than on social skills (Hayes et al. 1999). This may have the consequence that some students will never learn about the relevance of the therapeutic relationship in the physiotherapy process and later will not make the elements of this relationship explicit in their clinical reasoning processes.

Often physiotherapists consider communication as a by-product in therapy and don't consider this as ‘work’ (Hengeveld 2000); for example, ‘every time the patient attended she had so many questions that it cost 10 minutes of my treatment time and I could not start working with her’.

A study with interviews of 34 recipients of physiotherapy treatment showed that patients not only appreciate the outcomes of care but also the process in which therapy has been delivered. The following elements were identified as key dimensions that contribute to patient satisfaction with physiotherapeutic treatment:

• Professional and personal manner of the therapist (friendly, sympathetic, listening, respectful, skilled, thorough, inspiring confidence)

• Explaining and teaching during each treatment (identifying the problem, guidance to self-management, process of treatment, prognosis)

• How the treatment was consultative (patient involvement in the treatment process, responses to questions, responsiveness to self-help needs)

• The structure and time with the therapist (e.g. short waiting time, open access and enough time)

• The outcome (treatment effectiveness and gaining self-help strategies).

It is concluded that it is essential to establish expectations, values and beliefs with regard to physiotherapy treatment in order to optimize patient satisfaction with the delivered treatment (May 2001).

In order to develop a fruitful therapeutic relationship, well-developed communication skills and an awareness of some critical phases of the therapeutic process are essential.

Communication and interaction

Most people consider that communication between two people who speak the same language is simple, routine, automatic and uncomplicated. However, even in normal day-to-day communications there are many instances in which misunderstandings occur. Even if the same words are being used, they may have different meanings to the individuals involved in the communication.

Communication may be seen as a process of sending messages, which have to be decoded by the receiver of these messages. A message may contain various aspects: the content of the message, an appeal, an indication of the relationship to the person to whom the message is addressed, and revealing something about the sender of the message (Schulz von Thun 1981). This follows some of the axioms on communication as defined by Watzlawick in which it is discussed that ‘non-communication does not exist’ – in other words, communication always takes place, whether the participants are aware of it or not. Every communication bears aspects of content and relationship, and human communication follows digital and analogue modalities, the latter referring to verbal and non-verbal communication, which ideally should occur congruently (Watzlawick et al. 1969).

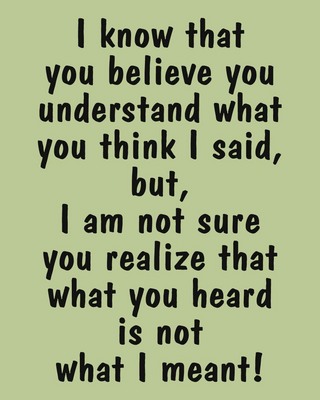

Many errors in communication occur as a result of different understanding and interpretation as well as to the selection of words. The cartoon depicted in Figure 3.1 highlights some of the difficulties which may occur during verbal communication. The last three lines in the cartoon bear greatest significance. This could be saying, ‘What I said was so badly worded that it did not express the thought that was in my mind’, or it is possible that the receiver tuned in, or listened closely only to those parts of the message that fitted their own way of thinking, and ignored other parts that did not. It is also possible that the receiver's expectations or frame of mind altered their perception.

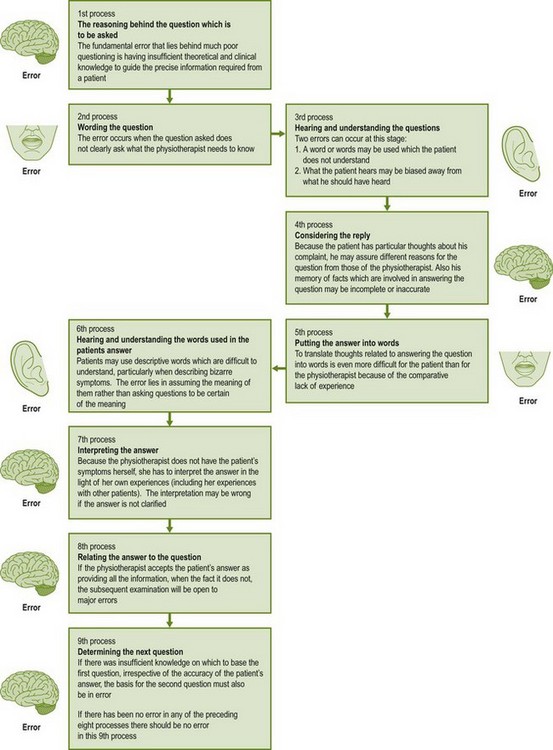

The feedback loop of Figure 3.2 indicates some of the coding errors which may occur during a communication between a ‘sender’ and a ‘receiver’ of a message.

Communication, as any other skill in clinical work, is an ability which can be learned and refined by continuous practice. Attention to one level of communication (e.g. content and meaning of words) can be practised step by step, until a high level of skill in uncovering meanings is developed. A good way of discovering more about an individual style of interviewing and communication is to record it on video or audiotape. Play it back to yourself and to constructive peers and supervisors.

The skill must be developed to a high level if a patient's problem is to be understood without any detail being missed. The learning of this skill requires patience, humility, clarity and constructive self-criticism. Words, phrases and intonation need to be chosen carefully when asking questions to avoid being misunderstood, and patients must be listened to carefully so that the meanings of the words they use are not misinterpreted (Maitland 1986). Attention needs to be given not only to what is said, but also to how it is said (Main 2004), including a careful observation of the body language of the patient.

The physiotherapist should not be critical of the way a patient presents. The very presentation itself is a message, needing to be decoded in the same way as the many other findings that the subjective and physical examinations reveal. Various elements may lead to misinterpretation of the severity of the patient's symptoms and/or disability.

The various ways that a person may experience pain or limitation of activities may lead to different expressions of pain behaviour. Some may seem stoic and do not appear to experience much distress, while others seem to suffer strongly and have high anxiety levels. The way people express pain, distress or suffering may be due to learning factors, including the family and the culture in which the person has been brought up. If patients are not fluent in the language of the examiner, their non-verbal expression to explain what is being experienced may be more exaggerated from the perspective of the examiner. Some patients will comment only on the symptoms that remain and do not comment on other aspects of the symptoms or activity levels that may have improved. The skilled physiotherapist can seek the positive side of the symptomatic changes rather than accepting the more negative approach of the patient. Overall, it is essential for the physiotherapist to develop an attitude of unconditional regard towards the patient and the situation, as suggested by Rogers (1980), even if the physiotherapist does not fully understand the patient's behaviour and manners with regard to pain and disability.

Aspects of communication

Communication consists of various components:

It is important that the physiotherapist creates a setting in which a free flow of communication is possible, allowing an uncomplicated exchange of information. Attention to the physical distance to the patient, not too far and not too close, often enhances the process of information gathering. At times a gentle touch will allow a quicker exchange of information, for example when the physiotherapist would like to know which areas of the body are free of symptoms. The physiotherapist may gently touch, for example, the knee of a patient in order to interrupt their somewhat garrulous dialogue, so they can highlight an important aspect of the information given or seek further clarification.

Congruence of verbal and non-verbal communication is essential. Eye contact is important, as is a safe environment in which not too many outside disturbances hinder the establishing of an atmosphere in which patients can develop trust to disclose information which they think might be compromising.

It is important that the physiotherapist pays attention not only to what is said, but also to how it is said. Often the body posture or the intonation of the voice or certain key words and phrases give indications of the individual illness experience, especially if certain words are used which may have a more emotional content (e.g. ‘it is all very terrible’). These may be clues to the patient's world of thoughts, feelings and emotions, which may be contributing factors to ongoing disability due to pain (Kendall et al. 1997). Attention to these aspects often allows the physiotherapist to perform a psychosocial assessment as an integral part of the overall physiotherapy-specific assessment.

As pointed out in various chapters of this edition and in Hengeveld & Banks (2014), many details are asked in order to be able to make a diagnosis of the movement disorder and its impact on the patient's life. Critics may say that the patient will not be able to provide all this information. However, it has long been a principle of the Maitland Concept that the ‘body has the capacity to inform’. If the physiotherapist carefully shapes the interview, pays attention to details such as selection of words and body language and explains regularly why certain questions or interventions are necessary, the patient will learn what information is of special relevance to the physiotherapist and pay attention to this.

Shaping of interactions

During the overall series of treatment, as well as in each session, it is important that the physiotherapist shapes the interaction deliberately, if a conscious nurturing of the therapeutic relationship seems necessary.

As in other counselling situations, each series of therapy, as well as each treatment session, knows three phases of interaction (Brioschi 1998):

• Initial phase – a ‘joining’ between physiotherapist and patient takes place on a more personal level in order to establish a first contact; personal expectations are established; the patient's questions may be addressed; the specific objectives of physiotherapy or of the session are explained; the specific setting is clarified (e.g. number of sessions, treatment in an open or closed room). The first subjective and physical examinations or the subjective reassessment takes place. It is essential that in this phase the (ongoing) process of collaborative goal setting has started.

• Middle phase – working on the treatment objectives and using interventions in a collaborative way; regular reassessment to confirm the positive effects of the selected treatment interventions. It is important that all aspects of goal setting, selection of interventions and reassessment parameters are defined in a collaborative problem-solving process between the physiotherapist and the patient.

• End phase of the session or of the treatment series – summary; attention to the patient's questions; recommendations, instructions or self-management strategies including reassessment; addressing of organizational aspects. Often it is very useful to ask the patient to reflect on what has been particularly useful in the current treatment session or series and what has been learned so far.

Often both the information and the end phase (including the final analytical assessment in the last sessions of the treatment series) seem to be neglected, mostly due to lack of time. However, once the more explicit procedures of the session are finished, towards the end of the session the patient often reveals information on the individual illness experience which may be highly essential for the therapy. The following example highlights this aspect.

A 72-year-old lady presents to the physiotherapist with a hip problem. Joint mobilizations in lying and muscle recruitment exercises in sitting and standing are performed. At the end of the session, when saying goodbye, the lady tells the physiotherapist that she was going to visit her daughter in another town. However, she was not confident in getting on a bus, as the steps were so high and the drivers would move off too quickly before she was even seated. On the levels of disability and activity resources, as defined by the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (WHO 2001), it was more relevant to redefine goals of treatment on activity and participation levels and for the patient to practise actually walking to and finding trust on entering the bus, rather than working solely on the functional impairments in the physiotherapy practice. This information was not given in the initial examination session, in spite of deliberate questioning by the physiotherapist.

Shaping of a therapeutic climate: listening and communication

In order to stimulate a safe environment in which a free flow of information can take place, the development of listening skills is essential. Therapists may well hear what they expect to hear rather than listening to the words the patient uses. The following quotation may serve to underline this principle:

Listening is itself, of course, an art: that is where it differs from merely hearing. Hearing is passive; listening is active. Hearing is voluntary, listening demands attention. Hearing is natural, listening is an acquired discipline.

It is essential to develop the skills of active and passive listening:

• Passive listening means showing that the therapist is listening, with body posture directed towards the patient, maintaining eye contact, and allowing the patient to finish speaking.

• Active listening encourages patients to tell their story and allows the therapist to seek further clarification.

Active listening may include clarifying questions such as ‘Could you tell me more about this?’, repetition and summary of relevant information such as ‘If I have understood you correctly, you would like to be able to play tennis again and find more trust in riding your bicycle?’, or asking questions with regard to the personal illness experience, for example, ‘How do you feel about your back hurting for so long?’

With active and passive listening skills the therapist can show that they have understood the patient.

In order to shape a therapeutic climate of unconditional regard (Rogers 1980), it is essential that the responses and reactions of the therapist are non-judgemental and neutral. Irony, playing the experience of the patient down, talking too much of oneself, giving maxims, threatening (‘if you won’t do this then your back will never recuperate’) or just lack of time may jeopardize the development of the therapeutic relationship (Keel 1996, cited in Brioschi 1998).

If patients reveal personal information, it is essential that they are given the freedom to talk as much about it as they feel necessary. At all times the physiotherapist should avoid forcing patients to reveal personal information which they would rather have kept to themselves. This may happen if the physiotherapist asks exploratory questions too aggressively. Some excellent publications with regard to ‘sensitive practice’ have been published, and are recommended for further exploration of this issue (Schachter et al. 1999).

Giving advice too quickly, offering a single solution, talking someone into a decision or even commanding may hinder the process of activating the patient's own resources in the problem-solving process. If possible, it is better to guide people by asking questions rather than telling them what to do. This is particularly essential in the process of collaborative goal setting in which the patient is actively integrated in defining treatment objectives. In this process it is important to define treatment objectives on activity and participation levels (WHO 2001) which are meaningful to the patient. Too frequently it seems that the physiotherapist is directive in the definition of treatment goals and in the selection of interventions (Trede 2000). Ideally the therapist may offer various interventions from the perspective of professional expertise to reach the agreed goals of treatment, and the decision is left to the patient to decide which solution may be best for the problem.

Communication techniques

Communication is both a skill and an art. Various communication techniques may be employed to enhance the flow of information and the development of the therapeutic relationship.

Open questions (e.g. ‘What is the reason for your visit?’)

Open questions (e.g. ‘What is the reason for your visit?’)

Questions with aim (e.g. ‘Could you describe your dizziness more?’, ‘What do you mean by pinched nerves?’)

Questions with aim (e.g. ‘Could you describe your dizziness more?’, ‘What do you mean by pinched nerves?’)

Half-open questions – as suggested in the subjective examination. The questions are posed with an aim, but they leave the patient the freedom to answer spontaneously. These questions often start with how, when, what, where (e.g. ‘How did it start?’, ‘When do you feel it most?’, ‘What impact does it have on your daily life?’, ‘Where do you feel it at night?’)

Half-open questions – as suggested in the subjective examination. The questions are posed with an aim, but they leave the patient the freedom to answer spontaneously. These questions often start with how, when, what, where (e.g. ‘How did it start?’, ‘When do you feel it most?’, ‘What impact does it have on your daily life?’, ‘Where do you feel it at night?’)

Alternative questions – leave the patient a limited choice of responses (e.g. ‘Is the pain only in your back or does it also radiate to your leg?’)

Alternative questions – leave the patient a limited choice of responses (e.g. ‘Is the pain only in your back or does it also radiate to your leg?’)

Closed questions – can only be answered with yes or no (e.g. ‘Has the pain got any better?’)

Closed questions – can only be answered with yes or no (e.g. ‘Has the pain got any better?’)

Suggestive questions – leave the patient little possibility for self-expression (e.g. ‘But you are better, aren’t you?’)

Suggestive questions – leave the patient little possibility for self-expression (e.g. ‘But you are better, aren’t you?’)

It may be necessary to employ a mixture of question styles in the process of gathering information. Half-open questions and questions with aim may provide information concerning biomedical and physiotherapy diagnosis; frequently, however, they are too restricting if the physiotherapist wants to get an understanding of the patient's thoughts, feelings and beliefs with regard to the individual illness experience and psychosocial assessment. Such questions may provoke answers of social desirability or the patient may not reveal what is actually being experienced:

• Modulation of the voice and body language – as described before

• Summarizing of information – in the initial phase this technique is often useful during the subjective examination in various stages: after the completion of the main problem and ‘body chart’, after the establishment of the behaviour of symptoms, after completion of the history and as a summary of the subjective and physical examinations

• Mirroring – in which the physiotherapist neutrally reports what is observed or heard from the patient

• (Short) pauses before asking a question or giving an answer

Probably the first requirement during interviews with patients is that the physiotherapist should retain control of the interview. Even if the physiotherapist decides to employ forms of ‘narrative clinical reasoning’ rather than procedural clinical reasoning (Chapter 2), it is necessary that the physiotherapist keeps an overview of the individual story of the patient and the given information which is particularly relevant to establish a diagnosis of a movement disorder and its contributing factors.

It is essential to use the patient's language whenever possible, as this makes things that are said or asked much clearer and easier to understand.

A versatile physiotherapist can develop various ways to stop or interrupt a more garrulous patient, by making statements such as ‘I was interested to hear about X, could you tell me more?’ Another possibility may be gently touching the patient's knee before stating, ‘I would like to know more about this’. Interposing a question at a volume slightly higher than the patient's or with the use of non-verbal techniques such as raising a hand, making a note, or touching a knee, tends to interrupt the chain of thought and this may be employed if the spontaneous information does not seem to be forthcoming. More reticent patients need to be told kindly that it seems they find it hard to talk about their complaints but that it is necessary for them to do so. They should be reassured that they are not complaining, but informing.

The following strategies are important to keep in mind during the interview:

• Use the patient's language and wording, if possible

• Ask only one question at a time

• Pose the questions in such a manner that as much as possible spontaneous information can be given (see above).

Paralleling

When a patient is talking about an aspect of their problem, their mind is running along a specific line of thought. It is likely that the patient could have more than one point they wish to express. To interrupt the patient may make them lose their place in their story. Therefore, unless the physiotherapist is in danger of getting confused, the patient should not be stopped if at all possible while the therapist follows the patient's line of thought. However, a novice in the field may rather first practice the basic procedures of interviewing, as paralleling is a skill which is learned by experience. Paralleling may be a time-consuming procedure if the patient starts off with a long history of, for example, 20 years. It may then be useful to interrupt and ask the patient what the problem is now and why help is being sought from the physiotherapist now – and from then on the physiotherapist may use the technique of paralleling.

Paralleling means that, from the procedural point of view the physiotherapist would like to get information (e.g. about the localization of symptoms), whereas the patient is talking about the behaviour of the symptoms. However, using ‘paralleling’ techniques does not mean that the physiotherapist should let the patient talk on without seeking clarification or using the above-mentioned communication techniques.

Immediate-response questions

At times the employment of immediate-response questions is essential. If during the first consultation a patient gives important information with regard to the planning of physical examination and treatment, immediate-response questions may be needed. Example:

Follow the patient's answer with: ‘In what direction?’, or: ‘Are you able to show me that quick movement now?’ The information on the area of the movement and the direction of the movement may be decisive in the selection of treatment techniques.

During subsequent treatments in the reassessment phases, the physiotherapist is in a process with the patient of comparing changes in the symptoms and signs. Frequently, however, the patient may give information which is a ‘statement of fact’. The patient may say, ‘I had pain in my back while watching football on television’. This is a statement of fact and is of no value as an assessment, unless it is known what would have happened during ‘watching television’ before starting treatment. This statement demands an immediate-response question: ‘How would you compare this with, for example, 3 weeks ago, when we first started treatment?’ The patient may respond that in fact 3 weeks ago he was not able to watch television at all, as the pain in his back was too limiting. Using immediate-response questions during this phase of reassessment prevents time being wasted and valuable information being lost. If the physiotherapist employs this technique kindly but consistently in the first few treatment sessions, the patient may learn to compare changes in his condition rather than to express statements of fact. At reassessment, convert statements of fact into comparisons!

Furthermore, immediate-response questions may be needed with non-verbal responses. There are many examples in which the examiner must recognize a non-verbal response either to a question or to an examination movement. The physiotherapist must qualify such expressions. For example, in response to a question the patient may respond simply by a wrinkle of the nose. The immediate-response question, in combination with a mirroring technique may be: ‘I see that you wrinkled your nose – that doesn’t look too good. Do you mean that it has been worse?’ etc.

Key words and phrases

During patients' discourses they will frequently make a statement or use words that could have great significance – the patient may not realize it, but the therapist must latch onto it while the patient's thoughts are moving along the chosen path. The physiotherapist could use it either immediately by interjecting or by waiting until the patient has finished. For example, the therapist might say:

By instantly making use of the patient's train of thought (paralleling) the development of the progressive history of the patient's shoulder pain is easier to determine for both the therapist and the patient, because, in fact, the patient's mind is clearly back at the birthday party.

As another example, having asked the question at subjective reassessment procedures, ‘How have you been?’, the patient may respond in a general and rather uninformative way. However, during subsequent statements the patient may include, for example, the word ‘Monday’. This may mean something to the patient and therefore it is often effective to use it and ask, ‘What was it about Monday?’, or ‘What happened on Monday?’

Bias

It is relatively easy to fall into the trap of asking a question in such a way that the patient is influenced to answer in a particular way. For example, the therapist may wish to know whether the last two sessions have caused any change in the patient's symptoms or activity levels. The question can be asked in various ways:

1. ‘Do you feel that the last two treatments have helped you?’

2. ‘Has there been any change in your symptoms as a result of the last two treatments?’

3. ‘Have the last two treatments made you any worse in any way?’

The first and third questions are posed with aim, nevertheless they are suggestive. The first question, however, is biased in such a way that it may push the patient towards replying with ‘yes’. The second and third questions are acceptable, as the second question has no specific bias and the third question biases the patient away from a favourable answer. Both questions allow the patient to give any spontaneous answer, even if the therapist is hoping that there has been some favourable change.

Purpose of the questions and assuming

In efficient information gathering it is essential for the physiotherapist to be aware of the purpose of the questions – no question should be asked without an understanding of the basic information that can be gained (see Chapters 1 and 2 of this volume, and Chapters 1 and 2 of the Peripheral Manipulation volume). For beginners in the field it is essential to know which questions may support the generation of which specific hypotheses.

Before asking a question it is vital for the physiotherapist to be clear about several things:

1. What information is required and why?

2. What is the best possible way to word the question?

3. Which different answers might be forthcoming?

4. How the possible reply to this question might influence planning ahead for the next question.

A mistake that often occurs with trainee manipulative physiotherapists is the accepting of an answer as being adequate when in fact it is only vaguely informative, incomplete or of insufficient depth. The reason for accepting an inadequate answer is usually that trainee physiotherapists do not clearly understand why they are asking the question and therefore do not know the number of separate answers they must hear to meet the requirements of the question. The same reason can lead to another error: allowing a line of thought to be diverted by the patient, usually without realizing it.

Assuming

If a patient says that pain is ‘constant’, it is wrong to assume that this means constant throughout the day and night. The patient may mean that, when the pain is present, it is constant, but not all day long. It is important to check the more exact meaning: is it ‘steady’ or ‘unchanging in degree’, ‘constant in location’ or ‘constant in time’?

Assuming may lead to one of the major errors in clinical reasoning processes: misinterpretation of information, leading to overemphasis or blinding out of certain information. Therefore it is well worth remembering: never assume anything!

Pain and activity levels

Sometimes the Maitland Concept is criticized for putting too much focus on the pain experience and some may state that ‘talking about pain causes some people to develop more pain’.

If in examination and reassessment procedures the physiotherapist focuses solely on the pain sensation and omits to seek information on the level of activities, bias towards the pain sensation may occur and some patients may be influenced to focus mainly on their pain experience. It may then seem that they develop an increased bodily awareness and become more protective towards movements which may be painful. It is therefore essential that the physiotherapist establishes a balanced image of the pain including the concomitant activity limitations and resources. Sometimes the pain experience does not seem to improve and leaves the patient and physiotherapist with the impression that ‘nothing helps’. However, if the level of activity normalizes and the patient may successfully employ some self-management strategies once the pain is experienced again, both the patient and physiotherapist may become aware of positive changes, if they look for them.

Some physiotherapists prefer, with some patients, not to talk about pain and to focus only on the level of activity and may even make a verbal contract with the patient to no longer talk about pain and only about function (Hengeveld 2000). However, often this is not of much help, as it denies one of the major complaints for which the patient is seeking therapy, and in fact it denies the most important personal experience of the patient. Nevertheless, in such cases it may be useful to use metaphors for the pain experience, wellbeing and activity levels. For example, rather than asking, ‘How is your pain?’, the therapist may ask, ‘What does your body tell you now in comparison with before?’ or, ‘If the pain is like a high wave on the ocean in a storm, how is the wave now in comparison with before?’

On the other hand, some patients prefer to focus on their activities rather than on the pain sensation alone. The following statement was once overheard in a clinical situation:

Patient to physiotherapist: ‘You always talk about the pain. However it is like having a filling of a tooth – if I give it attention, I will notice it. However I still am able to eat normally with it.

thus indicating that, to the patient, it is important to be able to function fully and that he will accept some degree of discomfort.

The process of collaborative goal setting

As stated earlier, it is recommended that within a therapeutic relationship patients need to be treated as equals and experts in their own right. Within this practice following a process of collaborative goal setting is recommended (Mead 2000).

There are indications that compliance with the recommendations, instructions and exercises may increase if treatment objectives are defined in a collaborative rather than a directive way (Riolo 1993, Sluys et al. 1993, Bassett & Petrie 1997).

It is essential to consider collaborative goal setting as a process throughout all treatment sessions rather than a single moment at the beginning of the treatment series. In fact, ongoing information and goal setting may be considered essential elements of the process of informed consent.

Various agreements between the physiotherapist and patient may be made in the process of collaborative goal setting:

• Initially the physiotherapist and patient need to define treatment objectives collaboratively

• Additionally, the parameters to monitor treatment results may be defined in a collaborative way

• The physiotherapist and patient need to collaborate on the selection of interventions to achieve the desired outcomes

• In situations where ‘sensitive practice’ seems especially relevant, some patients may need to be given the choice of a male or a female physiotherapist or may express their preference regarding a more open or an enclosed treatment room (Schachter et al. 1999).

Frequently, physiotherapists may ask a patient at the end of the subjective examination what would be the goal of treatment. Often the response will be that the patient would like to have less pain and no further clarification of this objective takes place. In some cases this approach may be too superficial, especially if the prognosis is that diminution of pain intensity and frequency may not be easily achieved. This may be the case in certain chronic pain states or where secondary prevention of chronic disability seems necessary. Patients commonly state that their goal of treatment is ‘having less pain’; however, after being asked some clarifying questions it often transpires that they wish to find more control over their wellbeing with regard to pain, in order to be able to perform certain activities again.

In the initial session during subjective examination, various stages occur in which collaborative goal setting may take place by the communication technique of summarizing:

• After the establishment of the main problem and the areas in which the patient may feel the symptoms

• After the establishment of the 24-hour behaviour of symptoms, activity levels and coping strategies

• After establishment of the history

• After completion of the physical examination (at this stage it is essential to establish treatment objectives collaboratively, not only in the reduction of pain, but also to define clear goals on the levels of activity which need to be improved and in which circumstances the patient may need self-management strategies to increase control over wellbeing and pain).

The relatively detailed process of collaborative goal setting needs to be continued during each session in its initial phase. It is essential to clarify if the earlier agreed goals are still to be followed up. If possible, it is useful to explain to the patient the diverse treatment options on how the goals may be achieved and then let the patient make the choice of the interventions.

Another phase of collaborative goal setting takes place in later stages during retrospective assessment procedures. In this phase a reconsideration of treatment objectives is often necessary. Initially the physiotherapist and patient may have agreed to work on improvement of pain, pain control with self-management strategies, educational strategies with regard to pain and movement, and to treat impairments of local functions, such as pain-free joint movement and muscular recruitment. In later stages it is essential to establish goals with regard to activities which are meaningful for the patient. If a patient is able to return to work after a certain period of sick leave, it is important to know about those activities which the patient seems most concerned about and where the patient expects to develop symptoms again. For example, an electrician who needs to kneel down in order to perform a task close to the floor may be afraid that in this case his back may start to hurt again. It may be necessary to include this activity in the training programme in combination with simple self-management strategies which can be employed immediately in the work-place.

This phase of retrospective assessment, including a prospective assessment with redefinition of treatment objectives on activity and participation levels, is considered one of the most important phases of the rehabilitation of patients with movement disorders (Maitland 1986).

To summarize, the process of collaborative goal setting should include the following aspects (Brioschi 1998):

• The reason for referral to physiotherapy

• The patient's definition of the problem, including goals and expectations

• Clarification of questions with regard to setting, frequency and duration of treatment

• Hypotheses and summary of findings of the physiotherapist, and clarification of the possibilities and limitations of the physiotherapist, resulting in agreements, collaborative goal definitions and a verbal or sometimes written treatment contract.

Critical phases of the therapeutic process

In order to shape the therapeutic process optimally, special consideration needs to be given to the information which is given to the patient and sought by the physiotherapist in specific phases of the therapeutic process. In fact, the educational task of the physiotherapist may start at the beginning of the first session in which the expectations of the patient towards physiotherapy need to be clarified.

If some of these critical phases are skipped it is possible that the process of actively integrating the patient into the therapeutic process is impeded. Attention to these phases supports the development of mutual trust and understanding, enhances the therapeutic relationship and aids in the development of a treatment plan. In these various stages regular interventions of collaborative goal setting should take place, clarifying step-by-step:

It is essential that the physiotherapist not only points out the possibilities of treatment, but also indicates, carefully and diplomatically, the possible limitations with regard to achievable goals. This is particularly essential in those cases where the patient seems to have almost unrealistic expectations of the physiotherapist, which it may not be possible to fulfil. Particularly with patients with chronic disability due to pain, it is frequently necessary to point out that the physiotherapy interventions may not necessarily be able to reduce the pain, but that the physiotherapist can work with them to find ways to establish more control over their wellbeing and to normalize the level of activities which are meaningful to them.

In general it is useful to pay attention to these critical phases in order to ‘keep the patient on board’. It is stated that novices in the field tend to be more mechanical in their interactions with patients in which their own procedures seem to prevail above the direct interactions with the patient (Jensen et al. 1990, 1992, Thomson et al. 1997). However, it is essential that the patient understands the scope and limitations of physiotherapy as a movement science as well as the reason for certain questions and test procedures. At times it can be observed in supervision or examination situations that physiotherapists appear to be preoccupied with their procedures of examination, treatment, recording and reassessment and seem to forget to explain to patients what they are doing and why. It may happen in such cases that the patient is not able to distinguish between a reassessment and a treatment procedure. Furthermore, by paying attention to the information of some critical phases, the physiotherapist may address some ‘yellow flags’, which may hinder the full recovery of movement function. Secondary prevention of chronic disability may start with the welcoming and initial assessment of the patient's problem.

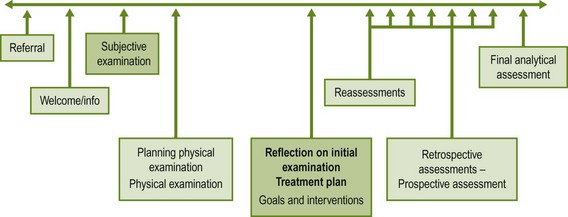

The critical phases of the therapeutic process (Fig. 3.3) need specific consideration with regard to providing and gathering of information.

Figure 3.3 Critical phases in the therapeutic process in which specific consideration is given to the information process.

Welcoming and information phase

After some ‘joining’ remarks to help the patient feel at ease as a first step towards development of a therapeutic relationship, it is important to inform the patient in this phase about the specific movement paradigm of the physiotherapy profession – the ‘clinical side’ of the brick wall analogy of the Maitland Concept. The patient may have different beliefs or paradigms from the physiotherapist as to the causes of the problem and the optimum treatment strategies, which may create an implicit conflict situation if not clarified in time. The physiotherapist may explain this to the patient in the following way:

I am aware that your doctor has seen you and diagnosed your problem as osteoarthritis of the hip and I have this diagnosis in the back of my head. However, my specific task as a physiotherapist is to examine and treat your movement functions. Maybe you have certain habits in your daily life, or you may have stiff joints or muscles which react too late. I need to ask some questions about this and I would like to look in more detail at your movements. Often when these movements improve, the pain of the osteoarthritis may also normalize. Is this what you yourself expected as a treatment for your problem?

Starting a session in this manner often prevents the patient from feeling irritation that the physiotherapist is starting off with an examination, when this may have already been done by the referring doctor. Furthermore, the patient may learn immediately that the physiotherapist follows a somewhat different perspective to problem-solving processes than a medical doctor. Too often patients do not understand that each member in an interdisciplinary team follows a unique frame of reference which is specific to their profession (Kleinmann 1988).

Some questions with regard to yellow flags may also be addressed with this information (Kendall et al. 1997, Main 2004):

• Is the patient expecting physiotherapy to help?

• Which beliefs does the patient have with regard to movement if something hurts?

• Does the patient feel that the problem has not been examined enough?

It is essential to be aware of certain key remarks indicating these points, for example, ‘Well, the doctor did not even bother to make an X-ray…’. If these points are addressed early enough in the treatment series, some patients may start to develop trust and carefully embark on a treatment, which they initially may have approached sceptically, especially if they have already had various encounters with many different health-care practitioners (Main & Spanswick 2000).

Subjective examination

The subjective examination serves several purposes as described in the chapters on assessment and examination (see Chapters 1 and 2 of this volume, and Chapters 1 and 2 of the Peripheral Manipulation volume).

It is essential to pay attention not only to what is said but also to how things are said by the patient. Key words, gestures and phrases may open a window to the world of the individual illness experience, which may be decisive in treatment planning.

Furthermore, the physiotherapist needs to ensure that the patient understands the purpose of the questions – be they a baseline for comparison of treatment results in later reassessment procedures or indicative of the physiotherapy diagnosis, including precautions and contraindications.

Most essential are the various steps in collaborative goal setting, which preferably take place throughout the overall process of subjective examination. With information on the main problem and the ‘body chart’, the physiotherapist may develop a first general idea of the treatment objectives; with increasing information throughout the whole examination, this image of the various treatment goals should become more and more refined.

Planning of the physical examination

The planning phase between the subjective and the physical examination is crucial from various perspectives. The main objective of this phase is the planning of the physical examination in its sequence and dosage of the examination procedures. However, it is important to summarize the relevant points of the subjective examination first and then to describe the preliminary treatment objectives on which the patient and the physiotherapist have agreed so far. Furthermore, it is essential to explain to the patient the purpose of the physical examination.

Physical examination

In order to integrate the patient actively in this phase of examination, it is recommended that the physiotherapist explains why certain test procedures are performed and teaches the patient to become aware of the various parameters which are relevant from the physiotherapist's perspective – for example, it may be important during active test movements to educate the patient that the physiotherapist is interested not only in any symptom the patient may feel, but also in the range of motion, the quality of the movement and the trust of the patient in the particular movement test. During palpation sessions and the examination of accessory movements, the patient should be encouraged not only to describe any pain but also any sensations of stiffness at one level in the spine in comparison with an adjacent level. This is a procedure which requires highly developed communication skills; however, it can be an important phase in the training of the perception of the patient.

Furthermore, it is recommended that physiotherapists inform patients not only about those tests which serve as a reassessment parameter, but also about the test movements that have been judged to be normal. Frequently it appears that physiotherapists are more likely to be deficit oriented in their examinations; however, to many patients it is a relief to hear from the therapist which movements and tests are considered to be normal.

Sometimes patients may indicate their anxiousness with certain test procedures (e.g. SLR) based on earlier experiences. In such cases it is essential to negotiate directly with the patient how far the physiotherapist will be allowed to move the limb. In fact, ‘trust to move’ may become an important measurable and achievable parameter, which may indicate the first beneficial changes in the condition of the patient.

Ending a session

Sufficient time needs to be planned for the ending of a session. On the one hand the physiotherapist may instruct the patient about how to observe and compare the possible changes in symptoms and activity levels. Furthermore, the therapist may need to warn the patient of a possible exacerbation of symptoms in certain circumstances. A repetition of the first instructions, recommendations or self-management strategies may be necessary in order to enhance short-term compliance (Hengeveld 2003). As described in ‘Shaping of interactions’ above, attention needs to be given to unexpected key remarks of the patient as these may be indicative of the individual illness experience and relevant treatment objectives.

Evaluation and reflection of the first session, including treatment planning

This phase includes summarizing relevant subjective and physical examination findings, making hypotheses explicit, outlining the next step in the process of collaborative goal setting for treatment and, if possible, collaboratively defining the subjective and physical reassessment parameters. If the physiotherapist is confronted with a recognizable clinical presentation, this phase may have occurred partially already during the examination process (‘reflection in action’). However, in more complicated presentations or in new situations the physiotherapist may need more time to reflect on this phase after the first session (‘reflection on action’) before explaining the physiotherapy viewpoints to the patient and suggesting a treatment plan (Schön 1983). In particular, trainees and novices in the field need to be given sufficient time to reflect before entering the next treatment session in order to develop comprehensive reflective skills (Alsop & Ryan 1996). The completion of a clinical reasoning form may aid the learning process of the students in the various phases of the therapeutic process.

Reassessments

As stated earlier, it is essential that patients are able to recognize reassessment procedures as such and do not confuse them with a whole set of procedures in which they may not be able to distinguish between treatment and evaluation. Education of patients may be required to observe possible changes in terms of comparisons, rather than statements of fact. Cognitive reinforcement at the end of a reassessment procedure may be helpful to support the learning processes of both the patient and the physiotherapist. If the physiotherapist employs educational strategies it may be necessary to perform a reassessment on this cognitive goal as well. Often it is useful to integrate questions with regard to self-management strategies in the opening phase of each session during the subjective reassessments. However, from a cognitive–behavioural perspective, the way a patient is asked if they are capable of doing their exercises and to evaluate the effects of these can be decisive in the development of understanding and compliance.

Retrospective assessment

In an earlier edition of Maitland's work it was stated that retrospective assessments are crucial aspects of the Concept. In retrospective assessment in particular, the physiotherapist evaluates patients' awareness of changes to their symptoms as one of the most important elements of evaluation. The only way to get this information is with skills in communication and awareness of possible changes in symptoms, signs, activity levels and illness behaviour. The physiotherapist evaluates the results of the treatment so far, including the effects of self-management strategies. In this phase it is essential to (re)define collaboratively with the patient the treatment objectives for the next phase of treatment, preferably on levels of activity and participation (WHO 2001) (‘prospective assessment’) and leading to an optimum state of wellbeing with regard to movement functions.

Final analytical assessment

This phase includes the reflection of the overall therapeutic process, when assessment is made of which interventions have led to which results. Often it is useful to reflect with the patient what has been learned so far. In order to enhance long-term compliance, the physiotherapist may anticipate collaboratively with the patient on possible future difficulties in activities or work and which self-management interventions may be useful if there is any recurrence (Sluys et al. 1993).

Verbatim examples

Although communication with a patient is a two-way affair, the main responsibility for its effectiveness lies with the therapist rather than with the patient. The therapist should be thinking of three things (Maitland 1991):

1. I should make every effort to be as sure as is possible that I understand what the patient is trying to tell me

2. I should be ready to recognize any gaps in the patient's communication, which I should endeavour to fill by asking appropriate questions

3. I should make use of every possible opportunity to utilize my own non-verbal expressions to show my understanding and concern for the patient and his plight.

The following verbatim examples in this text are used to provide some guidelines which will, it is hoped, help the physiotherapist to achieve the depth, accuracy and refinement required for good assessment and treatment.

The guidelines should not be interpreted as preaching to the ignorant – they are given to underline the essence of careful and precise communication as an integral part of overall physiotherapy practice.

Welcoming and information phase

As described above, the welcoming and information phase may be an essential stage to ‘get a patient on board’ in the physiotherapy process. This phase needs an explanation on the paradigms in physiotherapy, which can be understood easily by the patient. It is essential to find out if the patient can be motivated to physiotherapy and to develop trust in what is lying ahead in the therapy sessions.

In this phase it is also important to find out if a patient has already consulted a number of different specialists in the medical field for the problem. Often the patient may have received various opinions and viewpoints and is left confused, especially if they seem to have a more externalized locus of control with regard to their state of health (Rotter 1966, Härkäpää et al. 1989, Keogh & Cochrane 2002, Roberts et al. 2002). A patient may indicate by certain key phrases the expectation of a single cure according to the biomedical model, whereas the physiotherapist expects to treat the patient according to a movement paradigm in which self-management strategies may play an important role: ‘I have seen so many specialists – everybody says something different. Why don’t they find out what is wrong with me and then do something about it?’

There are many ways to respond to such a statement but it is crucial that such a key remark is not ignored. The physiotherapist may respond in various ways, for example:

Initial assessment: subjective examination

As stated above, in this phase it is vital to concentrate on both the patient's actual words and how they are delivered. Furthermore, during the overall process of subjective examination the process of collaborative goal setting should take place, in which treatment objectives are defined in a balanced approach to symptom control and normalization of activities, thereby enhancing overall wellbeing.

‘First question’ – establishing main problem

When the physiotherapist starts off the subjective examination, the first thing to be determined is the main problem in the patient's own terms. It is important that patients be given every opportunity to express their reasons for seeking treatment, for example with the first question being: ‘As far as you are concerned … [Pause…] (the pause helps the patient to realize that the therapist is specifically interested in the patient’s own opinion) … what do you feel … [Pause…] is your main problem at this stage?’

The patient may start off by answering, ‘The doctor said I've got tennis-elbow', or, ‘Well, I've had this problem for 15 years'.

In this case the physiotherapist may gently interrupt with an ‘immediate-response’ question such as:

After this answer the physiotherapist may determine the perceived level of disability. At this stage it is also essential to pay attention not only to what is said, but also to how it is said. The use of more emotionally laden words (‘it’s all very terrible and annoying, I can’t do anything anymore’), the non-verbal behaviour of expressing the main problem (e.g. looking away from the area of the symptoms while indicating this, a deep sigh before answering) or a seeming discrepancy between the level of disability and the expected impairments or areas of symptoms may guide the physiotherapist to the development of hypotheses with regard to ‘yellow flags’, which may facilitate or hinder full recovery of function.

In the determination of the localization of symptoms, at times it is important to ensure that certain areas are free of symptoms, in a sense if ‘not even half of 1%’ exists. In this case ‘immediate-response’ questions need to be asked:

The response to the examiner's first question with regard to the patient's main problem will guide the next question in one of two directions:

Behaviour of the symptoms

Without experience in the choice of words or phrasing of questions, an enormous amount of time can be taken up in determining the behaviour of a patient's symptoms. Unfortunately, it needs time if the skill is to be learned, for nothing teaches as well as experience. The information required relative to the behaviour of a patient's symptoms is:

• The relationship that the symptoms bear to rest, activities and positions

• The constancy, frequency and duration of the intermittent pain and remission, and any fluctuations of intensity (‘irritability’)

• The ability of the patient to control these symptoms and promote wellbeing (coping strategies)

• The level of activity in spite of the symptoms

• Definition of first treatment objectives on activity and participation levels, as well as further coping strategies.

The following is one example that provides a guide as to the choice of words and phrases that will save time and help the therapist avoid making mistaken interpretations and incorrect assumptions. The conversation that follows is with a man who has had 3 weeks of buttock pain. The text relates only to the behaviour of the buttock pain (adapted from Maitland 1986):

Some readers may consider the above answers are too good to be true. However, as the physiotherapist learns to ask key questions to elicit spontaneous answers, the responses become more informative and helpful in understanding both the person and his problem, hence the development of a therapeutic relationship and a differentiated baseline for later reassessment procedures.

The behaviour of the patient's symptom of stiffness may also be significant when there is some pathology involved. For example, during the early part of the examination the physiotherapist may develop the hypothesis that ankylosing spondylitis may be the background of the patient's movement disorder. The conversation and thoughts may be something like this:

History of the problem

History taking is discussed in numerous chapters of this book. The discussion here relates to communication guidelines. Especially in those patients in whom the disorder is of a spontaneous onset, many probing questions are needed to determine the predisposing factors involved in the onset. The following text is but one example of the probing necessary in the history taking of this group of patients:

There are many ways the questions can be tackled, and the answer to each will take about the same length of time.

After a delay, while he ponders the question, the answer comes:

Now I would like to know, as his train of thought is still ‘3 weeks ago’, if he considered doing any self-management interventions during the day he was lifting so much.

As already mentioned, when interviewing more garrulous patients, trying to keep control of the interview is challenging. During history taking these patients tend to go off at tangents and give a lot of detailed information. This may need to be skillfully interposed by gently increasing the volume of your voice and simultaneously touching the patient gently. However, the important thing is that the examiner can retain control of the interview without insulting or upsetting the patient. Nevertheless, every effort should be made to make patients feel that they are not complaining, rather they should be told that they are informing – ‘What you don’t tell me, I don’t know.’

For example the opening question and answer might be as follows:

This is often a difficult situation – is this the patient's train of thought, which may provide the therapist eventually with valuable spontaneous information, or is it better to interrupt? Some intervening questions to keep control of the interview may be as follows:

Initial assessment: physical examination

After a summary of the main findings of the subjective examination and agreed treatment objectives, it is essential that the patient is informed about the purpose of the test movements to allow the patient an active role in the procedures. This may be worded as follows:

We have agreed that we would try to work on activities like bending over and standing. I've understood that it is important to you that you feel capable of jogging again soon and inviting people to your home. Am I correct? (patient agrees). Now I would like to look more specifically at your movements of your shoulder and neck, in order to see if they all meet the basic requirements to fulfil such tasks.

While performing the test procedures, the purpose of active test movements, as well as the parameters relevant for reassessment procedures can be explained:

The patient is asked to bend his head forward and then return to the upright position.

Patient does this and makes a grimace.

This example demonstrates how much close attention the pain responses to the movement deserve. The physiotherapist usually simultaneously observes the quality and range of movement. However, often it is necessary to guide the patient to this observation in order to teach him all the essential parameters of a test procedure. Furthermore, it is important for the patient to understand that the physiotherapist wants to use these movements in later reassessment procedures to observe if any beneficial changes have occurred. To many patients this is a strange procedure, as they often naturally would want to avoid the painful movements. To omit precision in this area would be a grave mistake. Once the behaviour of the pain is established and the patient understands the purpose of these test procedures, the treatment techniques can be suitably modified and the appropriate care given to treatment and reassessment.

The intonation of the patient's speech can also express much to the physiotherapist. During the consultation every possible advantage should be taken of all avenues of both verbal and non-verbal communication. The more patients one sees, the quicker and more accurate the assessment becomes.

And so the examination continues. The examples given should show how it is possible to determine very precise, accurate information about the responses to movement without great expenditure of time. Obviously it is not always as straightforward as the example given, but it is nearly always possible to achieve the precision.

Some patients become quickly irritated in subsequent treatment sessions by being asked the same questions in the same detail. The physiotherapist who is tuned into the patient's non-verbal communication will quickly get this message. One way around this, without losing precision, is to vary the question:

‘Upper arm again?’ or, ‘Only upper arm?’, or, ‘Same?’

Palpation

During palpation sequences and examination of accessory movements it is important to actively integrate the patient in the examination as well. Often the patient will be asked to comment only on any pain. However, if the patient is guided towards giving information on his perception of the tissue quality and comparing the movements of various levels of the spine, he learns that many more subtle parameters may be relevant to reassessment procedures and hence to his wellbeing.

While performing, for example, accessory movement of the cervicothoracic junction the following verbal interactions may take place.

Physiotherapist performs accessory movements of the C5–7 segments:

With this method of questioning the patient may learn several things: first, that the physiotherapist is truly interested not only in finding the painful segments of the spine, but also that the therapist does not want to hurt him unnecessarily. Second, the patient may develop trust in the physiotherapist.

The physiotherapist now examines T1–4, which are not painful but have a very limited range of motion.

Summarizing the first session: collaborative treatment planning and goal setting

At the completion of the first session, after a subjective and a physical examination as well as a first probationary treatment, including reassessment, it is essential to summarize the main points. This is relevant to train the clinical reasoning processes of the physiotherapist and to inform the patient about the viewpoints of the therapist, to clarify the goals of treatment once more and to define the interventions to achieve these objectives. Furthermore, the parameters which indicate any beneficial treatment effects need to be defined collaboratively with the patient.

The process of collaborative goal setting requires skill in communication as well as in negotiation. At times a patient may simply expect to have ‘less pain’, although it may seem in the prognosis that reduction in pain intensity and frequency will not be easily achieved. It may even be more challenging if the patient states that ‘first the pain has to disappear and then I will think of work and activities’. It is almost always relevant to define goals with control of pain and wellbeing, including normalization of activities, as fear avoidance behaviour has been described as one of the major contributing factors to ongoing disability due to pain (Klenermann et al. 1995, Vlaeyen & Linton 2000). However, not only the avoidance of activities but also the avoidance of social contacts and interesting stimuli, e.g. going to the theatre, are important contributing factors (Philips 1987). Furthermore, a lack of relaxation or a lack of bodily awareness during the activities of normal daily life may be relevant contributing factors and may need to be included in the collaborative goal-setting process.

The following interaction could take place:

Initially in this interaction it seems that the patient only seeks ‘freedom from pain’ in its intensity; however, after a few probing questions it becomes clear that the woman is more probably looking for a sense of control over her pain and developing trust in activities that she has avoided so far. The use of a metaphor for the pain (as in this example ‘a wave on the ocean’) frequently shows that in fact the patient is seeking control rather than simply reduction of pain and improvement in wellbeing. Often it is useful to take the time for this process of clarifying treatment goals as unrealistic expectations may be identified and the patient sometimes learns that there are other worthwhile goals to be achieved in therapy as well. Furthermore, it aids reassessment purposes as both the physiotherapist and patient learn to pay attention to activities which serve as parameters – for example, the trust to move and control over pain rather than sensory aspects of pain alone (e.g. pain intensity, pain localization and so on).

At times physiotherapists think they are involved in a collaborative goal-setting process; however, they may be more directive than they are aware (Chin et al. 1993). In order to enhance compliance with the agreed goals, ideally it is better to guide people by asking questions rather than telling them what to do. The following example may highlight this principle:

The patient is a 34-year-old mother of three young children who takes care of the household and garden, nurses her sick mother-in-law and helps her husband in the bookkeeping of his construction business. She is complaining of shoulder and arm pain. The physiotherapist is treating her successfully with passive movements in the glenohumeral joint. However, the pain is recurrent and the physiotherapist's hypothesis is that lack of relaxation and lack of awareness of tension development in the body and during movements may be very important contributing factors. The physiotherapist would like to begin relaxation strategies which could easily integrate with the patient's daily life and subsequently would like to start work on bodily awareness of relaxed movement during normal daily activities (see also the example of collaborative goal setting discussed below).

Directive interaction

This directive way may develop an agreed goal of treatment; however, the patient is not provided with any tools on how to achieve this goal. This may impede short-term compliance (Sluys & Hermans 1990). Furthermore, it has been shown that compliance with suggestions and exercises may increase if goals are defined in a more collaborative way (Bassett & Petrie 1997).

Beginning of a follow up session: subjective reassessment