Recording

Some remarks with regards to recording

Recording of subjective examination findings

Recording of physical examination findings

Recording of treatment interventions

Information, instructions, exercises, warning at the end of a session

Recording of follow-up sessions

Introduction

Assessment and treatment require an in-depth written record of the findings and results at each session. Ideally, documentation which is systematic, consequent and easy to (re-)read in a short time provides the physiotherapist with a framework that should lead the therapist throughout the overall therapeutic process. Systematic records serve as a mnemonic and a means of communication to other professionals. They support the physiotherapist in various ways:

• To reflect upon the decisions made

• To control the actions taken

• If necessary, to quickly adapt the therapy to a changing situation.

Hence, written records are essential in the process of ongoing quality management.

It is argued that many physiotherapists consider documentation of sessions as a necessary evil. As a consequence many records frequently seem superficial and incomplete (Cohen 1997). Although probably recording will not be encountered with a lot of positive expectations in learning the ‘art of physiotherapy’, there are various reasons why physiotherapists should consider the recording of the sessions they shape:

• Records serve as a mnemonic for the physiotherapist of what has been done, thought and planned

• Systematic recording serves clinical reasoning and learning processes: committing thoughts to paper forces therapists to think more precisely and accurately and to become aware of their own reasoning processes. It enhances reflection and monitoring decisions made and actions taken

• Committing the essence of examination and treatment findings to paper is a valuable learning experience in itself. It forces one to identify the things that are essential, and record them, and leave out the less important information

• Committing thoughts to paper, with systematic recording, helps to clear the mind as the information and impressions gained throughout are organized

• Recording of patient information, actions and planning steps support the development of clinical patterns in memory. Therefore recording may be an essential process in the development of experiential knowledge (Higgs & Titchen 1995, Nonaka & Takeuchi 1995)

• Ideally, the records should document the trail along which assessment and treatment are moving

• Comprehensive, systematic patient records may serve as a basis for clinical case studies

• Records may be a mnemonic for the patient as well. In some cases, the patient may have forgotten how the disorder has been improved immediately following a treatment. If for other reasons a few days later the symptoms recur, the patient may easily interpret the condition as unchanged. Examination of the record made immediately following the treatment may guide the physiotherapist as well as the patient in the reassessment of the patient's condition over the whole period directly after the last session until the moment that symptoms increased again

• Records aid communication in team collaboration. If a colleague is absent from work, the physiotherapist may be able to continue with the initialized course of treatment, provided the records are such that they are understandable

• Recording for legal reasons – in many countries physiotherapists are enforced by law to store their patient records for a certain period of time. Furthermore, physiotherapy records may be used in litigation

• An increasing number of professional associations declare documentation as an integral part of the physiotherapy process (ÖPV 1998, WCPT 1999, Heerkens et al. 2003).

SOAP notes

Recording of therapy sessions must include detailed information, yet must be brief and provide a simple overview. Within this concept use has been made of the so-called ‘SOAP’ notes (Weed 1964, Kirk 1988). The acronym SOAP refers to the various parts of the assessment process:

It is not mandatory to follow the guidelines and abbreviations as set out in this book; however, some method must be determined to suit the patient's comments and the therapist's pattern of thinking. The basic elements of the SOAP mnemonic may serve as a useful format to follow all the steps of the therapeutic process in a brief and comprehensive way.

It has been argued that the term ‘objective’ in the SOAP notes is somewhat awkward, due to the fact that the physiotherapist values the subjective experience of the patient while performing the test movements. Furthermore, it is argued that the physiotherapist as the ‘measuring instrument’ will give attention to those aspects of a test which seem most relevant at the time, and thus true objectivity in test procedures may not exist (Grieve 1988). It has therefore been decided to replace the term ‘objective examination’ with ‘physical examination’ (P/E).

There has been criticism that SOAP notes within problem oriented medical records (POMR) would confine the physiotherapist to focusing merely on biomedical data (French 1991); however, if the physiotherapist pays attention to key words and specific key phrases of the patient which are indicative of the individual illness experience, they may be recorded in parentheses and integrated in the documentation, thereby incorporating elements of the individual illness experience into the records.

At all times patient records should include the findings as well as the steps in planning –a trail is laid of what is done and what is thought. Recording encompasses ideally:

Asterisks

During the subjective examination the patient may state certain facts related to the disability which may prove to be valuable parameters for reassessment procedures. These should be highlighted in the records immediately, and an ‘asterisk’ sign may be used.

Although the use of asterisks is not mandatory, it may speed up the whole process. They are time savers, reminders and indicators of highly important facts for the particular person. Identifying these main assessment markers with a large, obvious asterisk not only enforces a commitment but also makes reassessment procedures quicker, easier, more complete and therefore more valuable.

Using asterisks is just as valuable for the physical examination parameters as it is for the subjective examination. Similarly, making use of the asterisks progressively during the physical examination rather than after is recommended. The same applies to each subsequent session.

At times it seems that the term ‘asterisk’ has become jargon; however, it is not meant in such a way. People teaching and working with this concept may frequently use the term ‘subjective and physical examination asterisks’. Mostly this refers to information of subjective and physical examination parameters which will be reassessed at regular intervals over the whole therapeutic process in order to monitor progress in rehabilitation and the effects of treatment (Box A4.1).

Conditions

Some people may prefer other ways of recording. However, regardless the method of recording, some conditions need to be fulfilled. Patient records need to be:

Some remarks with regards to recording

It is important to record related information even when the findings indicate normality. By their having been recorded, reference at a later date shows that the particular questions have been asked or physical examination tests have been carried out.

Recording normal findings on a ‘record sheet’ is a quick and simple procedure. For example, if a patient has pain in the shoulder area and the therapist has examined the acromioclavicular joint comprehensively and found it to have normal painless movements, all that might be recorded is:

The point is, it must be recorded.

There is much more to be recorded from an initial consultation than for subsequent sessions. However, the same detail is required and so the same details and abbreviations can be used. People have likes and dislikes about these symbols – this does not matter, provided the criteria for comprehensive recording are met.

Questionnaires as well as ‘cheat sheets’ as they are often termed, have advantages and disadvantages. The primary considerations are that they should not be regimented and they should not be detailed. A cheat sheet that has a list of questions requiring ticks and crosses, should not be used. They are inflexible and destroy independent thinking on the part of the examiner, and they completely obliterate any chance of following the patient's line of thought or the pursuit of hypotheses in greater detail.

Recording of subjective examination findings

With each patient there are many questions and answers that need to be entered in the recording, even if it is only to show that the question, which was important, has in fact been posed and answered.

It is a safe procedure to utilize the patient's words during the recording of subjective examination findings. For example, if a patient complains of a pulling in the arm while lifting the arm above the head, this needs to be recorded as the patient said it, rather than the physiotherapist's language of ‘symptoms or pain with flexion’, as this may immediately narrow down the physiotherapist's thinking.

Key words and phrases indicative of the personal illness experience may be put in quotation marks. It has been emphasized that such key words and phrases may be essential information to the shaping of the therapeutic process, hence they have to be recorded accordingly.

Organization of the information in the main categories of the subjective examination is essential to keep an overview over the process of subjective examination. While asking questions regarding the ‘main problem’, it is possible that the patient gives information on history mingled with, for example, bits of symptomatic behaviour. In such cases it is relevant to leave sufficient space on the paper to organize and record the information under sections ‘history’ or ‘behaviour’ rather than writing down every bit of information in a chronological manner. This will help the physiotherapist to keep an overview over the whole process of subjective examination, even if the communication technique of ‘paralleling’ has been chosen (Chapter 3).

Body chart

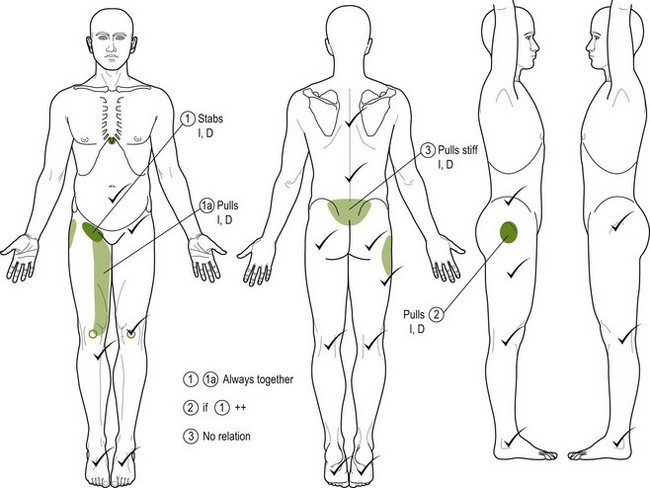

• Frequently, after establishment of the patient's main problem and receiving a more general statement about the perceived disability, the area, depth and nature, behaviour and chronology of the symptoms are clarified and recorded on a ‘body chart’ (Fig. A4.1).

• Reference to such a body chart provides a quick and clear reminder of the patient's symptoms and main problem.

• A well-drawn body chart helps to generate hypotheses on the sources of the movement dysfunction or symptoms as well as on the neurophysiological pain mechanisms. Additionally, first hypotheses with regard to precautions and contraindications may be made.

• In principle, the body chart is drawn by the physiotherapist to facilitate recording and memory.

• Occasionally, in patients with chronic pain states, the body chart may be drawn by the patient. If different colours are used, as a metaphor for the pain experience they may become a guide in reassessment procedures.

• If the information on a body chart is recorded consistently at the same place all the time, self-monitoring mechanisms are more easily activated. If the physiotherapist forgets to ask certain questions, this may be noticed more easily when re-reading the information.

• The use of Arabic numerals in circles for the different symptom areas simplifies later recording: if there is a need to refer to the symptom areas, the numerals can be used rather than lengthy descriptions of the symptom areas.

Clinical tip

Always record the same information on the same spot of the body chart. This enhances self-monitoring – on re-reading the information it will be easier to discern if certain details are missing.

Behaviour of symptoms and activities

The information on the ‘behaviour of symptoms’ is essential to the expression of many hypotheses. Furthermore, the information usually serves in reassessment procedures of subsequent sessions. Therefore the information needs to be recorded in sufficient detail.

If activities or positions are found which aggravate the patient's symptoms, this has to be recorded meticulously. However, any easing factors also need to be written down straight away, on the same line as the activity which provokes the symptoms. This may sound pedantic to some; however, it will give the physiotherapist an immediate overview as to which activities and positions the patient has developed as useful coping strategies and with which ones the patient may need some help.

History

At times it may be difficult to keep an overview of all the information regarding the history of a patient's problem and to monitor if all the relevant data have been obtained. This may happen particularly in those circumstances where there have been more episodes and the problem has been recurrent for many years.A4.

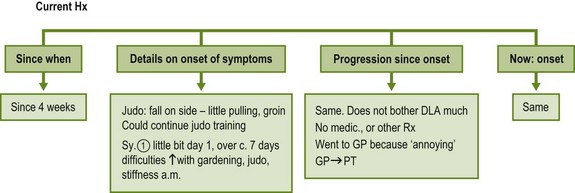

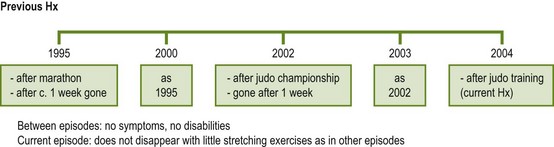

Although not mandatory, the physiotherapist may draw a line indicative of the course of time to keep an overview of both the current and previous history (Figs A4.2, A4.3).

Recording of physical examination findings

Physical examination findings need to be recorded in sufficient detail and systematically in order to allow for quick referencing during subsequent reassessment procedures.

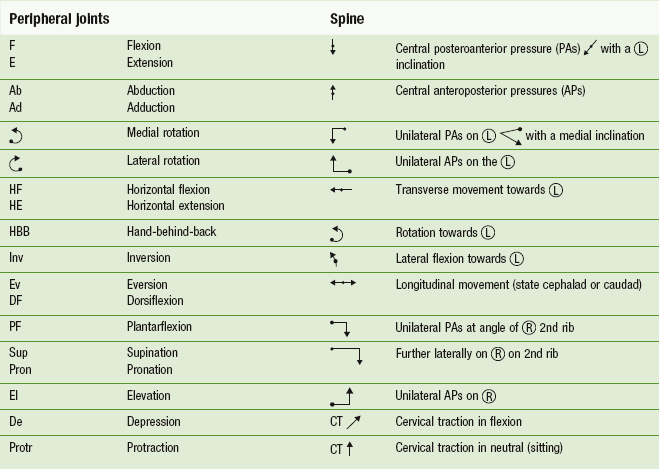

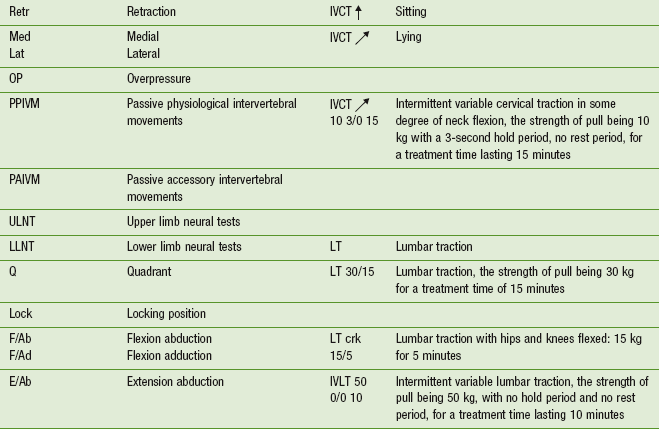

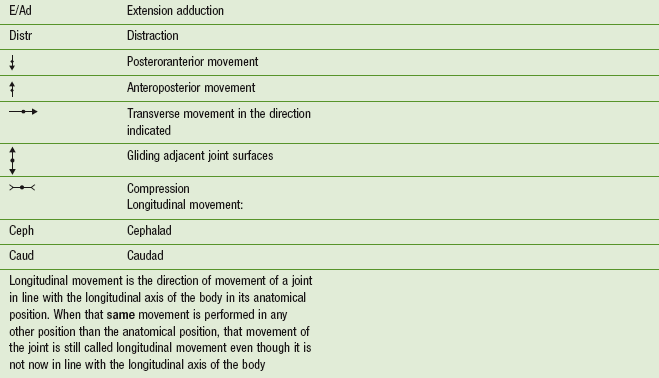

Making use of symbols helps speed up the process and enhances quick referencing (Table A4.1).

Active movements

When recording the range and quality of movement and the symptomatic response to that movement, one should develop a pattern of recording and stick to it. By doing so, more facts can be remembered, while at the same time leaving the therapist's mental processes more time to take in other details. Active movement findings can be recorded as follows:

This example means supination (sup) has a normal range and quality of movement (the first tick, √) and has no abnormal pain response when overpressure is applied (the second tick, √).

It is suggested relating the first tick (√) to movement responses such as range and quality of movement and the second tick (√) to symptom responses which occur during the test movement. It may be indicated with a grading of IV−, IV or IV+ how firm the overpressure has been. This is particularly relevant in those cases where the physiotherapist wants to test the movements with a certain amount of overpressure; however, factors in the ‘nature of the disorder’ may limit the physiotherapist in applying maximum overpressure.

A movement cannot be classed (or recorded) as normal unless the range is pain free both actively and passively. Further overpressure applied at the limit of the available range should not cause pain other than normal responses.

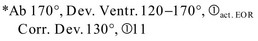

Abnormal findings may be recorded as follows:

This indicates that the range of abduction has been 170°, with a deviation of the movement between 120° and 170° of abduction; symptom reproduction occurred at the active end of range without application of overpressure. With correction of the deviation in the movement, the range decreased until 130° of abduction and the pain was clearly increased.

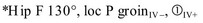

This example shows that the overall range of hip flexion was 130°, without any deviations in the quality of the movement; local symptoms were produced with a light overpressure (‘IV−’), symptom reproduction occurred with stronger overpressure (‘IV+’).

Passive movements

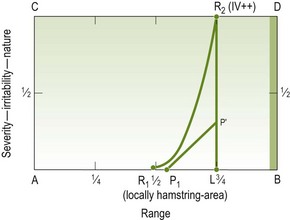

With passive movement the behaviour of pain, resistance and motor responses (spasm) is monitored. The physiotherapist is particularly interested in how these components behave and relate to each other. This is a very detailed examination procedure and may be considered as a part of the ‘art of manipulative physiotherapy’. Most simply, but not mandatory, would be the drawing of a movement diagram, as delineated in Appendices 1–3. Otherwise abnormal findings regarding the behaviour of P1 and P', R1 and R2, including their relationship, may be recorded verbally.

If certain passive movements are classed as normal, the same method (√), √)) as with active movements may be used. However, if relevant abnormal findings are present, this method is not sufficiently comprehensive.

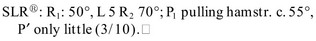

This example indicates that the physiotherapist first felt an increase in resistance with c. 50° of SLR, the movement was limited by resistance at c. 70° of SLR, only a little pulling sensation was provoked in the hamstrings area. Figure A4.4 illustrates the associated movement diagram.

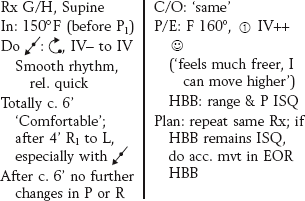

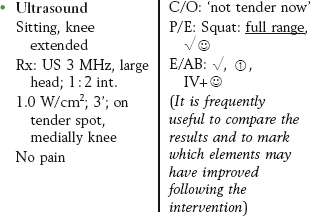

Recording of treatment interventions

Before performing a treatment technique, the planning and the reasoning for its selection should be recorded. Next, the treatment and its effect should be written down. This needs to include sufficient details in order to be able to refer back at later stages when making retrospective assessments.

The treatment record for a passive mobilization technique should contain:

• selected treatment technique(s), including inclinations of the movements

• rhythm in which the technique was performed

• duration (in number of repetitions or time units)

• symptomatic responses and the patient's reactions while the intervention is being performed (‘assessment during treatment’ – see Chapter 6)

• reassessment immediately following the technique (it is usually helpful to make comparisons or statements as to which parameters have improved and which ones have stayed unchanged).

It is essential not only to record the treatment by passive movement in detail but also active procedures, exercises or physical applications (e.g. ultrasound requires the same depth of recording).

Treatment is followed by a reassessment in which patients are asked to make a comparison of any changes of symptoms or in their sense of wellbeing resulting from the technique. This is then followed by a reassessment of the affected physical examination tests. Ideally, the records of the physical examination findings include a brief appraisal of the results in comparison with the assessment just before the application of the treatment technique.

Finally, at the end of a treatment session, the clinician should commit to paper thoughts on how treatment needs to be modified at the next session. Such an analysis not only forces the clinician to reflect on clinical reasoning processes, but also stimulates memory of the last treatment session.

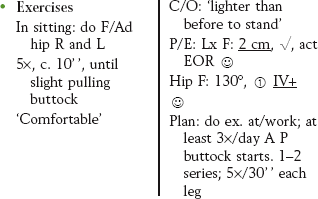

Information, instructions, exercises, warning at the end of a session

Any information or instruction given during the treatment, any exercise that the patient should perform as a self-management strategy needs to be recorded as well.

At the beginning of a treatment series it is often important to warn the patient diplomatically for possible exacerbations. This also needs to be recorded.

Example

• Warned about possible increase; however, if spot gets smaller, may be a good sign.

– mornings getting out of bed – changes in stiffness?

– working in garden – anything different from before?

• Instruction (e.g. remembers anything particular about fall during judo?).

Recording of follow-up sessions

When recording follow-up sessions, the first words must include a quotation of the patient's opinion of the effect of the previous treatment. This quotation must be worded in such a way that it is a ‘comparison’ rather than just a ‘statement of fact’. The subjective reassessment is then completed in which the physiotherapist clarifies those activities that serve as parameters and have been highlighted with an asterisk in the records of previous sessions.

Following the subjective reassessment the record includes the physical examination tests which are being reassessed. These too are recorded as comparisons with the previous findings.

Changes in the physical examination findings will hopefully agree with the findings of the subjective assessment, so reinforcing each other. This will then make the total assessment more reliable.

Also during reassessment of physical examination tests it may be necessary to record key words and phrases; in the rehabilitation of, for example, shoulder problems it may be a good sign if the patient makes the spontaneous remark: ‘the arm is mine again’.

The following pattern may be used in recording follow-up sessions:

• Date, time of the day, R× 3, D8 (indicating third session on eighth day since the initial consultation)

• C/O spontaneous information: ‘better’, ‘felt lighter than before’

• C/O follow-up of subjective parameter: putting on socks today cf. yesterday: no pain (5 unusual! First time in 3 weeks!)

• P/E: reassessment of physical examination parameter (including statements of comparison with after/before the previous treatment)

• P/E: additional tests as planned

Retrospective assessment

The record of retrospective assessment has to stand out from other parts of the treatment so that the information can be easily traced on reviewing progress in later sessions. This is particularly important when a patient has an extensive disorder and considerable treatment. To be practical, time must be a consideration, but not at the expense of detail and accuracy.

Especially within retrospective assessment, in the written record three requirements should be respected:

1. To stand out from other data (to be highlighted so that it is readily seen on checking back through the record).

2. To state with what time frame the comparison is made (e.g. R× 5 cf. R× 1).

Retrospective assessments should include the following information and comparisons:

• General wellbeing compared with, for example, four sessions ago

• Symptoms compared with, for example, four sessions ago (know indicators of change – see Chapter 5)

• Level of activities compared

• Effect of interventions so far (P/E and passive movements)

• Effect of instructions, recommendations and exercises so far

• What has the patient learned so far – what was particularly relevant to the patient?

• Comparison of all the relevant physical examination parameters compared with, for example, four sessions ago

• Which interventions brought which results? (certain physical examination findings may improve more with some interventions than with others)

• Goals for the following phases of treatment (process of collaborative goal setting: redefinition or confirmation of agreed goals to treatment, interventions and the parameters to measure if the objectives are being achieved).

Written records by the patient

There are times when it is necessary for a patient to write a running commentary of the behaviour of the symptoms. For example, a patient may be a poor historian in which case he may be asked to write down how he feels immediately following treatment, how he feels that night and how he feels on first getting out of bed the next morning. Some people may feel this is encouraging a patient to become overly focussed on his symptoms. However, if the patient is asked not only to record how he feels, but also the level of activities, medication intake and possible self-management interventions, such a record may become a highly valuable teaching instrument which aids both the patient and the physiotherapist.

There are many different types of pre-printed form that can be used. However, it is essential that the forms leave space for information regarding:

• activities before and during the increase of symptoms

• activities throughout the day/week

• employment of self-management strategies to influence wellbeing, including the effects of the interventions.

When a written record by the patient is used, it should be handled by the manipulative physiotherapist in a particular sequence:

1. On receiving it from the patient, it should be laid down.

2. The patient should be asked to give a general impression of the effect of the last treatment.

3. The subjective assessment of the effect of the last treatment should be taken through to its conclusion.

4. The written record can then be assessed and any discrepancies clarified.

Conclusion

Although recording of examination findings, treatment interventions and results, and regular planning, may not be the most interesting part of learning, it is an essential element of the quality of the overall therapeutic process. It monitors the physiotherapist throughout the process and allows quick adaptation of interventions, if needed. When recording is accurate and succinct, and can be correctly interpreted by another person reading it, it is an invaluable self-teacher and may support physiotherapists on their path to expertise and maintaining this.

References

Cohen, L. Documentation. In: Wittink H, Hoskins Michel T, eds. Chronic Pain Management for Physical Therapists. Boston: Butterworth-Heinemann, 1997.

French, S. Setting a record straight. Therapy Weekly. 1991;1:11.

Grieve, GP. Critical examination and the SOAP mnemonic. Physiotherapy. 1988;74:97.

Heerkens, YF, Lakerveld-Hey, K, Verhoeven, ALJ, et al. KNGF – Richtlijn Fysiotherapeutische Verslaglegging. Amersfoort: KNGF; 2003.

Higgs, J, Titchen, A. The nature, generation and verification of knowledge. Physiotherapy. 1995;81:521–530.

Kirk, D. Problem Orientated Medical Records: Guidelines for Therapists. London: Kings Fund Centre; 1988.

Nonaka, I, Takeuchi, H. The Knowledge-Creating Company. New York: Oxford University Press; 1995.

ÖPV. Broschüre Berufsbild Physiotherapeut. Vienna: Österreichischer PhysiotherapieVerband; 1998.

WCPT. Description of Physical Therapy. London: World Confederation of Physical Therapy; 1999.

Weed, L. Medical records, medical education and patient care. Ir J Med Sci. 1964;6:271–282.

↑ Gardening, pulling weeds, in squat position; after 10' P1

↑ Gardening, pulling weeds, in squat position; after 10' P1  , after 20'

, after 20'

↓ 100% immed. May continue gardening.

↓ 100% immed. May continue gardening. ↑ Putting on socks, in standing – activity possible as usual

↑ Putting on socks, in standing – activity possible as usual ↓ 100% immed. as soon as leg is put down.

↓ 100% immed. as soon as leg is put down. ↑ Lying in bed – prone, right leg pulled up. Wakes up c. 03:00

↑ Lying in bed – prone, right leg pulled up. Wakes up c. 03:00

‘acceptable’

‘acceptable’