Management of sacroiliac and pelvic disorders

Introduction

Low back and leg pain may have various causes and contributing factors. These include biomedical elements as pathobiological processes as well as movement impairments of the lumbopelvic–hip complex.

Over the past two decades numerous research efforts have contributed to the knowledge of the role of the pelvic girdle in movement disorders leading to pelvic, low back and leg pain.

PGP has been defined as follows:

Pelvic girdle pain generally arises in relation to pregnancy, trauma, arthritis and osteoarthritis. Pain is experienced between the posterior iliac crest and the gluteal fold, particularly in the vicinity of the SIJ. The pain may radiate in the posterior thigh and can also occur in conjunction with/or separately in the symphysis.

The endurance capacity for standing, walking and sitting is diminished.

The diagnosis of PGP can be reached after exclusion of lumbar causes. The pain or functional disturbances in relation to PGP must be reproducible by specific clinical tests.

(Vleeming et al. 2008, p. 797)

It is proposed that the definition for pelvic musculoskeletal pain should be under the title ‘pelvic girdle pain’ in order to exclude gynaecological and/urological disorders (Vleeming et al. 2008).

Symptoms associated with the sacroiliac joints (SIJ) represent a subgroup of pelvic girdle disorders (O'Sullivan & Beales 2007a, 2007b). Based on a study including joint-infiltrations, Maigne et al. (1996) conclude that the prevalence of sacroiliac disorders may be approximately 18.5% in a general population. Vleeming et al. (2008), after a review of four prospective studies, conclude that there is strong evidence of a point prevalence of close to 20% of women during pregnancy. These results show that it is necessary for clinicians to routinely consider the pelvic girdle and particularly the SIJ as a possible cause or contributing factor to a patient's low back and leg pain.

Numerous studies have been undertaken to test the validity and reliability of clinical sacroiliac tests with inconclusive results particularly with regards to mobility testing. However, there does appear to be agreement that pain provocation tests are supportive in clinical decision making regarding the role of the SIJ if composite tests of pain provocation procedures reproduce the patient's symptoms consistently (van der Wurff et al. 2000, Laslett et al. 2005, Vleeming et al. 2008).

With regards to treatment, the European Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of PGP recommend specific individualized motor control exercise programs for pregnant women and individualized multimodal treatment for other patients (Vleeming et al. 2008).

The choice of the best treatment for each patient is based on a thorough subjective and physical physiotherapy assessment; an essential feature of the Maitland Concept. The primary focus of the examination of lumbopelvic and leg symptoms frequently needs to be placed on the reproduction of the patient's symptoms. The signs and symptoms found on assessment then need to be related to the functional limitations of the patient. The treatment objectives are first defined and then priorities are set.

Although musculoskeletal manual physiotherapists adhere increasingly to the concept of evidence based practice, it is essential to bear in mind that:

… external clinical evidence can inform, but can never replace individual expertise, and it is this expertise that decides whether the external evidence applies to the patient at all, and if so, how it should be integrated into a clinical solution.

(Sackett et al. 1998, p. 3)

Physiotherapists should therefore constantly reflect upon their clinical reasoning in decision-making throughout the process of assessment and treatment.

When symptoms are suspected to be of pelvic girdle origin, physiotherapists need to incorporate in their assessment, the examinations of the sacroiliac joints and when indicated that of the symphysis pubis and coccyx. Furthermore the assessment of motor control patterns needs to be included.

Applied theory and evidence supporting practice

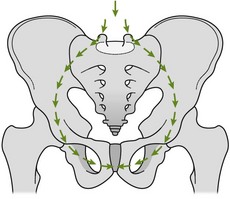

The pelvic girdle is a very stable structure, which as a unit supports the abdomen and the organs of the lower pelvis. Furthermore it provides a dynamic link between the spine and the lower extremities (Fig. 7.1).

Figure 7.1 Transference of forces between the trunk, pelvis and femur. Reproduced from Palastanga et al. (1994) with kind permission from Elsevier.

Form closure, force closure, mobility

The pelvic girdle receives its stability from the interconnection between the symphysis pubis and the sacroiliac joints, a strong ligamentous system and the wedge shape of the sacrum, fitting vertically between the innominates. These elements build a self-locking system (Kapandji 2008) and contribute to the form closure of the pelvic girdle (Vleeming et al. 1997).

Furthermore, various muscle groups and fasciae cross over the pelvic girdle. Their function adds to the dynamic stability of the system, which relates to the dynamic force closure.

The wedge-shaped sacrum is suspended between the innominates and contributes to the stability in the transverse plane because of its irregular semilunar joint formation and the connection to the (short) dorsal sacroiliac and sacrotuberous ligaments (Kapandji 2008, Vleeming et al. 1997). Furthermore, the symphysis pubis contributes to the stability of the pelvic girdle (Kapandji 2008). In this self-locking mechanism, nutation of the sacrum plays an essential role, as it winds up most of the sacroiliac ligaments (Vleeming et al. 1997).

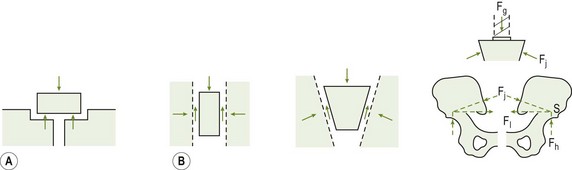

However, if the sacrum were to fit perfectly between the innominates, practically no movement would be possible. Some degree of movement in the sacroiliac joints has been described and up to 1.6 mm of translation and about 4° of rotation has been measured in radiostereometric analysis of the sacroiliac movements (Sturesson et al. 2000b). In order to withstand vertical loads, such as in standing positions, and to prevent shear forces, a lateral force and friction are needed to maintain stability. This occurs by the nutation movement of the sacrum in relation to the innominates and by compression generated by the myofascial structures (force closure; see Fig. 7.2).

Figure 7.2 A combination of form closure A and force closure B allow for the strong stability of the pelvic girdle. Reproduced with permission from Vleeming et al. (1997).

Numerous studies demonstrate poor inter-examiner reliability values with regard to the mobility of the sacroiliac joints (van Deursen et al. 1990, Laslett et al. 2005, van der Wurff et al. 2000). A reason for this phenomenon is offered by Sturesson et al. (2000a) who observed, in radiostereometric analyses of the movements of the sacroiliac joints during weight bearing positions, a further decrease in the already small mobility, which adds to the difficulty to detecting movement during manual examination procedures.

In symptomatic patients, the mobility may be marginally increased (Kissling & Jacob 1997), which may also be a challenge to detect with manual testing.

Local and global stabilizing muscle system

Based on widespread publications regarding lumbopelvic stabilization, the following aspects need to be taken into consideration:

• Panjabi (1992) discussed that effective load transfer and stability is achieved when passive, active and neural control systems work together in harmony. As part of the passive sub-system, form closure with its osteoarticular and ligamentous structures plays a central role. The structures making up the passive system give feedback and have a direct link to the neural control system. In the active system, force closure with its myofascial elements are just as important, give feedback and are influenced by the neural control system.

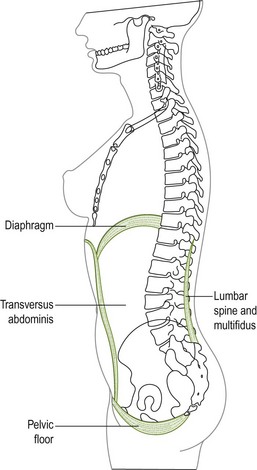

See Figure 7.3 for a diagrammatic representation of the abdominal-pelvic cavity surrounded by muscles contributing to lumbopelvic stability, intra-abdominal pressure and continence.

Figure 7.3 Diagrammatic representation of the abdominal-pelvic cavity surrounded by muscles contributing to lumbopelvic stability, intra-abdominal pressure and continence. From Sapsford (2001a).

TA has been shown to impact stiffness of the pelvis through its direct attachment to the innominate, to the middle layer and to the deep lamina of the posterior layer of the thoracolumbar fascia (TLF). The pelvic floor muscles should be given sufficient attention as their importance is not negligible (next to the function of transverse abdominal and multifidi) in enhancing increased stiffness of the pelvic ring and proper load transfer in the lumbopelvic region, particularly in the treatment of PGP in women (Pool-Goudzwaard et al. 2004). Based on a study with needle EMG, Sapsford and colleagues (Sapsford 2001, 2004, Sapsford & Hodges 2001) conclude that the abdominal muscles contract in response to pelvic floor contraction and vice versa: the pelvic floor muscles contract in response to both a ‘hollowing’ and ‘bracing’ visualization exercise of the lower abdominal wall. Richardson et al. (2002) have reported that co-contraction of TA and MF increases the stiffness of the SIJ. Pel et al. (2008) showed that shear forces through the SIJ could be significantly reduced by simulated activity of TA and PF muscles. It is therefore obvious that local muscles work in synergy and tend to co-contract to stabilize the pelvic girdle.

The timing of contraction of local muscles appears to be important for force closure of the pelvis. Intramuscular EMG analysis suggests that TA exhibits contraction prior to perturbation of the trunk and before rapid limb movements are initiated (Hodges & Richardson 1998). Hungerford et al. (2003) have also found that during one leg standing (OLS), the onset of TA and internal oblique (IO) precede a weight shift in healthy individuals.

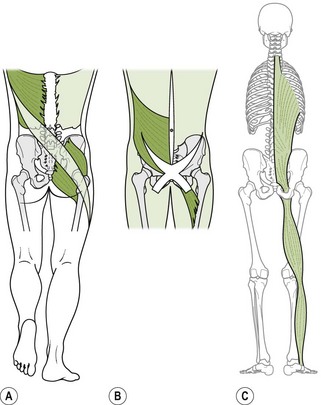

The global (stabilizing) muscle system is made up of four slings of muscles groups which have been described as stabilizing the pelvis regionally (Fig. 7.4; Lee 2004):

Figure 7.4 Posterior, anterior and longitudinal slings of the global stabilizing muscle system. (A from Vleeming et al. 1995; B and C from Lee 2004, with permission.)

• Posterior oblique sling, containing connections between the latissimus dorsi and the contralateral gluteus maximus through the thoracodorsal fascia (Vleeming et al. 1995)

• Anterior oblique sling, containing connections between the external oblique muscles, the anterior abdominal fascia, contralateral internal oblique muscles and the adductors of the hip

• Longitudinal sling, connecting the peroneal muscles, biceps femoris, sacrotuberous ligament, the deep layer of the thoracodorsal fascia and the erector spinae

• Lateral sling, containing the primary stabilizers of the hip – gluteus medius, minimus, tensor fascia latae, contralateral adductors and the lateral stabilizers of the thoracopelvic region.

These four global muscle slings do not function in isolation, but they interconnect, partially overlap and function together (Lee 2004). Although the global muscle slings may not directly control intervertebral motion, as does the local stabilizing system, the global muscles can generate tension in the thoracolumbar fascia which can produce compression on the posterior pelvis, which assists in the control of shear and rotation forces to which the lumbopelvic region is submitted (Vleeming et al. 1995, Hodges 2004, Barker et al. 2004). The slings are assumed to play a role in the capacity to use our legs and trunk for energizing the body (Vleeming & Stoeckart 2007).

The posterior oblique sling

• The posterior oblique sling has been shown to affect the force closure at the SIJ.

• Gluteus maximus (GM) has the greatest capacity for force closure via the posterior layer of the TLF and has been noted to transmit tension directly behind the SIJ as low as S3 (Barker et al. 2004, Barker 2005).

• van Wingerden et al. (2004) report that GM contraction causes an increase in stiffness at the SIJ ×2–3 that noted with contraction of latissimus dorsi during gait.

• Rotation against resistance has been found to activate the posterior oblique sling (Vleeming & Stoeckart 2007).

• GM creates a muscle link between the tensor fascia lata and the TLF. Contraction of the GM increases stiffness in both fascia that span the lumbar spine, SIJ and hips.

• Hungerford et al. (2003) have found that the onset of contraction of gluteus maximus is altered with SIJ dysfunction.

The deep longitudinal sling

• ES and MF are part of the deep longitudinal sling that simultaneously contribute to compression of the lumbar segments and provide a dynamic restraint to A/P shear stresses in the lumbar spine.

• The muscles making up this sling increase tension in the TLF and compress the SIJ.

• Biceps femoris can influence sacral nutation through its connection to the sacrotuberous ligament and plays a role in the intrinsic and extrinsic stability of the pelvis in relation to the leg (Vleeming et al. 1997).

The anterior oblique sling

Muscles of the anterior sling with the anterior abdominal fascia create compression across the pubic symphysis (Snijders et al. 1993).

Optimal strategy in motor control will vary between individuals and for different tasks. Multiple strategies are needed to ensure stability during both static and dynamic tasks. Optimal force closure is just the right amount of force being applied at just the right time. Situations of high load and low predictability will require a stiffening strategy whereas many other low load tasks of high predictability, such as walking, will require a dynamic strategy through phasic muscle activity (Hodges et al. 2003).

Patients with failed load transfer present with inappropriate force closure in that certain muscles become overactive while others, known to stabilize the pelvis (such as IO, MF and GM) remain inactive, delayed or asymmetric in their recruitment (Richardson et al. 2002, Hungerford et al. 2003, 2004). Maladaptive motor control strategies can minimize the function of muscles such as the IO and TA and thereby impede the bracing mechanism of the pelvic joints (Beales et al. 2009). Changes in motor control can occur in situations when pain is anticipated but not present and when there is a real or a perceived risk of injury or pain (Hodges & Cholewicki 2007).

Some common maladaptive compensation strategies around the pelvis:

• Women with stress incontinence may have increased EO activity which may overcome the activity of the PF muscles and lead to incontinence

• Deficits in respiration and continence may lead to compromised spinal control (Hodges & Cholewicki 2007)

• Hyperactivity of global muscles such as the obliques, erector spinae and external rotators of the hip can lead to chest gripping (hyperactivity of obliques), back gripping (overactivity of erector spinae), butt gripping (hyperactivity of hip external rotators – piriformis and obturator internus). These strategies are often seen in patients who lack segmental spinal, intrapelvic and/or hip motion control (Lee 2004). If any of these strategies are noted, releasing the hypertonic muscles should be addressed prior to assessing and training the local muscles.

Healthy integrated neuromyofascial system ensures that loads are effectively transferred through the joints while mobility is maintained, continence preserved and respiration supported (Lee & Vleeming 2007). According to Lee & Lee (2010), it is not enough to know which muscles have the capacity of increasing force closure; there is also a need to understand how the CNS controls and directs synergistic activity in function. Emotional states, influenced by past experiences, beliefs, fears and attitudes should be taken into account as they can impact motor control and affect strategies in function (Lee & Vleeming 2007).

Classification model

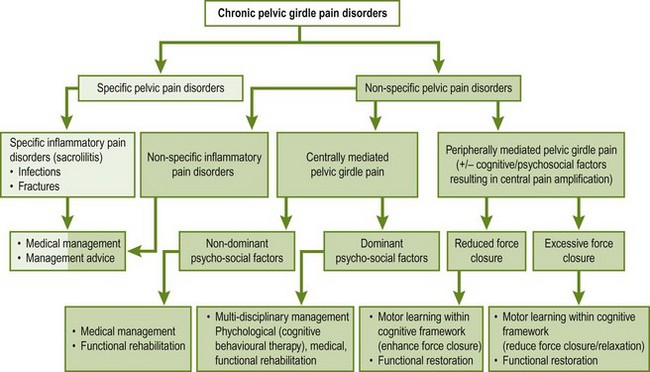

O'Sullivan and Beales (2007a) propose a broad classification model for the management of chronic PGP disorders, in which, among others, the following issues need to be taken into consideration to direct appropriate management of a patient's problem:

• Considering chronic PGP within a bio-psychosocial framework, in which attention needs to be given to potential physical, patho-anatomical, psychosocial, hormonal and neurophysiological factors

• Questioning if the PGP disorder is related to a specific or a non-specific pain disorder (see Fig. 7.5)

Figure 7.5 Mechanism based classification of chronic pelvic pain disorders. (From O'Sullivan & Beales (2007a) with permission.)

• In cases of non-specific pain disorders, with nociceptive pain mechanisms, reflecting on the cause of the disorder whether it is associated with an excessive force closure due to muscle hyperactivity of the pelvic muscles or to a reduced force closure due to a motor control deficit.

Treatment

Based on the best available current evidence, the European Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Pelvic Girdle Pain (Vleeming et al. 2008) provide various recommendations for treatment.

The aims of treatment are to relieve pain, improve functional stability and prevent recurrences and chronic disability due to pain.

Recommendations for specific treatment interventions are described in Table 7.1.

Table 7.1

Recommendations of the European Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of PGP

| Information, reassurance | Although there is no evidence to recommend information as a single treatment, information as part of a multimodal treatment should reduce fear and encourage patients to take an active part in their rehabilitation |

| Stabilizing exercises | … the use of an individualized treatment programme focusing on specific stabilizing exercises as part of a multimodal treatment. (Vleeming et al. 2008, p. 808), in which individualized treatments have been demonstrated to be more effective than general group training or no treatment. The stabilizing exercises should focus on normalization of control and stability of force closure |

| Joint mobilization, manipulation | Joint mobilization and manipulation may be used to test for symptomatic relief, but should only be applied for a few treatments |

| Pelvic belt | A pelvic belt may be fitted to test for symptomatic relief, but should only be applied for short periods |

| Pain medication | May be given, if necessary, for pain relief. First choice: paracetamol; second choice: NSAIDs |

| Intra-articular injections | May be recommended for ankylosing spondylitis (under imaging guidance) |

(adapted from Vleeming et al. 2008)

There is evidence that passive mobilization and manipulation can be effective for the relief of pain and restoration of mobility in the short term (Koes et al. 1996, AAMPGG 2003). However, in order to maintain long-term results, motor control, education and self-management strategies are essential (O'Sullivan et al. 1997, Richardson et al. 1999, AAMPGG 2003). Manipulation has also been suggested for treatment of both acute and chronic low back pain patients (van Tulder & Koes 2010). This could be extended to the SIJ in cases where there is excessive force closure, as long as it is only part of a multimodal approach to treatment.

Consideration of other factors leading to PGP

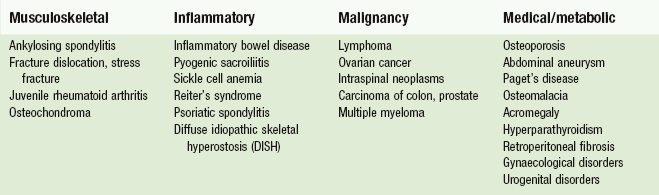

In the presentation of non-mechanical or unclear symptoms, which do not respond to adequate treatment, clinicians need to bear in mind that different pathobiological processes may cause or contribute to PGP, which may require medical attention (Table 7.2).

Table 7.2

Pathobiological conditions leading to PGP

(adapted from Hansen & Helm 2003; Huijbregts 2004)

Clinical reasoning

As stated before, it is essential that physiotherapists are aware of all decisions they make during the whole therapeutic process. The clinical reasoning processes are complex. Hence, in order to guide clinical practice, it is essential to make the hypotheses that have been generated during assessment and treatment explicit at regular intervals during treatment sessions and to reflect upon them.

To optimize efficiency, categorization of the hypotheses is recommended (Jones 1995, Thomas-Edding 1987). The possible hypotheses are listed in Table 7.3.

Table 7.3

Hypotheses categories which guide the decisions in the overall clinical process

| Hypotheses category | Remarks | |

| Pathobiological processes Tissue pathology |

It is essential to ask screening questions related to different bodily systems, indicative of possible contraindications, which need the attention of a medical practitioner | This is guided by the question: ‘is there any pathobiological process on the background of this movement disorder?’ If they are no contraindications, they determine a precaution to treatment or may guide the selection of treatment techniques |

| Neurophysiological symptom mechanisms | Nociceptive mechanisms Peripheral neurogenic mechanisms Central nervous system Modulation Autonomic nervous system processes |

Nociceptive mechanisms, as well as certain peripheral neurogenic mechanisms may be considered part of ‘end-organ dysfunction’ (Apkarian & Robinson 2010) in which the patient feels pain because of nociceptive processes in the spine, SIJ etc. Normally the pain occurs in a ‘stimulus-response relationship’ and appears in relation to the history of the problem: over time the pain reduces and the levels of activity are normalizing again. In cases of larger peripheral neurogenic lesions, central nervous system modulation and ongoing autonomic nervous system processes, altered nervous system processes appear to be occurring. Pain and activity intolerance do not occur in a stimulus response relationship and seem to last longer than could be expected if normal healing/recuperative processes occur |

| Sources of nociceptive processes and movement dysfunction | Possible sources of symptoms and movement dysfunction in relation to PGP: Sacroiliac joint Symphysis pubis Coccyx Lumbar spine Hip Thoracic spine Neurodynamic system Muscles, e.g. trigger points in m.piriformis Soft tissues |

This relates to movement impairments and structures, which may be responsible for the (nociceptive and/or peripheral neurogenic) pain It is possible that different sources are simultaneously responsible for the pain (e.g. SIJ and lumbar spine) which need to be addressed in treatment. In cases of non-mechanical presentation or insufficient reaction to adequate treatment, other causes as for example visceral dysfunctions need to be considered |

| Contributing factors | This may include any physical, biomechanical, emotional, cognitive and behavioural factors which may contribute to or maintain the problem | Motor control patterns frequently play an essential role in the maintenance and recurrence of PGP symptoms (Hodges 2004, Lee 2004, O'Sullivan & Beales 2007a, 2007b) |

| Individual illness experience | This may be influenced by earlier experiences, thoughts, feelings, beliefs, values and social environment. The individual illness experience has a core influence on the illness behaviour, incl. the employment of coping strategies of a patient From a phenomenological perspective physiotherapists guide patients towards an individual sense of health and health promoting behaviour with regards to movements functions (Hengeveld 2000) |

Patient with PGP may have been told that their pelvis is ‘displaced’ or ‘unstable’ leading to beliefs that no active control can be achieved, thus becoming dependent on someone to fix their problem Educational and motivational strategies may be needed to explain contemporary viewpoints on the role of muscular recruitment and rehabilitation. |

| Precautions and contraindications | Defined by the severity and irritability of the nociceptive processes, stability of the disorder, as well as by underlying pathobiological processes, stages of tissue healing, other pathologies and the patient's confidence to move | |

| Management | Determined by the activities and participation restrictions as described in the subjective examinations, by the movement impairments found in physical examinations and the contributing factors as well as the individual illness experience | In cases of nociceptive pain, first priorities may be put on pain reduction with passive mobilization and automobilization techniques. Motor control exercises need to be incorporated in an early phase of treatment In cases of ongoing pain and disability, possible pathobiological processes need to be ruled out. Furthermore neuropathic processes need to be considered as well as ‘yellow flags’, for example, beliefs regarding treatment, lack of sense-of-control over the pain, fear, habitual movement patterns and non-helpful thoughts as contributing factors to the problem |

| Prognosis | Which results may be expected from treatment on a short term basis, after e.g. four sessions? Which results may be expected as an end-result of treatment? Which results may not be achieved? If after four sessions the results do not mirror the short term prognosis, the physiotherapist has to reconsider all hypotheses and check if certain aspects of treatment need to be followed up more |

The following factors may determine a favourable prognosis (Banks & Hengeveld, 2010): Strong relationship of patient's symptoms and movement Recognizable syndrome (clinical pattern) Predominantly primary hyperalgesia and tissue-based pain mechanisms Model of patient: helpful thoughts and behaviours (‘I can still do some things’, ‘I have found ways to get relief’) Familiar symptoms, which the patient recognize as tissue based (‘It feels like a bruise’) No or minimal barriers to recovery or predictors of chronicity (‘yellow flags’) Severity, irritability and nature of the patient's symptoms correspond to the history of the disorder/to injury or strain to the structures of the movement system Previous, favourable experiences with manipulative physiotherapy Patients are touch tolerant Internalized locus-of-control with regards to health and well-being Realistic expectations of the patient towards recovery which correspond to the natural history of the disorder Patients resume appropriate activity and exercise at relevant stages of recovery |

Clinical reasoning and assessment procedures

Assessment procedures and clinical reasoning are inseparable elements in the therapeutic process. Ongoing assessment takes place at the beginning of each treatment session, during treatment and after the application of therapeutic techniques. Hypotheses are continuously being confirmed, discarded or modified.

At times it may be challenging to determine if the SIJ is contributing to the movement disorder of the patient. It is possible that only one (highly sensitive) sacroiliac test, for example the Posterior Pelvic Pain Provocation Test (P4-test), consistently reproduces the patient's symptoms. If this test is the most comparable sign in the examination, the SIJ should then be treated first.

The therapists can then use the principle of ‘differentiation by treatment’, another feature of the Maitland Concept to validate their decision.

Evidence based practice

Evidence based practice is defined by Sackett et al. (1998, pp. 2 & 3) as:

The conscientious, explicit and judicious use of current best evidence in making decisions about the care of individual patients. The practice of evidence-based medicine means integrating individual clinical expertise with the best available external clinical evidence from systematic research.

Although compliance with evidence based practice is highly recommended, physiotherapists may face dilemmas in making decisions with regards to the choice of best management, including communication, educational strategies and selection of treatments. It is well known that there is not enough research evidence for every clinical situation so clinicians need to be informed of what is known and make their own clinical decisions accordingly (Lee & Lee 2010). Physiotherapists need a balanced and pragmatic approach towards clinical and evidence-based-practice. Not only will physiotherapists need a ‘mastery of patient interviewing and physical examination skills’ (Sackett et al. 1998, p. IX), they will also need ‘a proficiency in the application of various treatments, including communication abilities and clinical reasoning skills’ (Hengeveld & Banks 2005, p. 81).

Subjective examination

An important feature of the Maitland Concept is a detailed interview of the patient, which includes the patient's perspective on the pain, concomitant disability, coping strategies and beliefs regarding pain, causes of the problem and necessary treatment strategies.

Various forms of clinical reasoning may be employed during the process of subjective examination. Within the diagnostic process and the determination of treatment procedural reasoning with hypotheses generation and pattern recognition frequently plays a central role (Payton 1987). The other forms of clinical reasoning frequently used include interactive, conditional and narrative clinical reasoning (Edwards 2000, Jones & Rivett 2004). It is considered that the various strategies of clinical reasoning are in an intrinsic relation in clinical practice, in which the physiotherapist moves between the various forms of clinical reasoning to shape an optimum examination and treatment process collaboratively with the patient (Edwards et al. 2004). Procedural reasoning aids the diagnostic process and treatment planning. Forms of narrative and interactive clinical reasoning are frequently employed to develop a deeper understanding of the patient's individual experience regarding pain and disability, including beliefs, thoughts, feelings and sociocultural influences.

It may be concluded that well-developed communication skills are essential elements of the physiotherapy process. They serve several purposes (Hengeveld & Banks 2005):

• They aid in the process of information gathering with regard to physiotherapy diagnosis, treatment planning and reassessment of results

• They may serve to develop a deeper understanding of the patient's thoughts, beliefs and feelings with regard to the problem. This information assists in the assessment of psychosocial aspects which may hinder or enhance full recovery of movement functions

• Empathic communication also enhances the development of a therapeutic relationship

• They serve in the process of collaborative goal formulation, in which in cooperation with the patient therapeutic objectives, parameter for reassessment procedures and selection of therapeutic interventions are being determined.

Detailed information on communication and the therapeutic relationship is included in Chapter 3.

Specific objectives of subjective examination

The overall process of examination aims to determine the physiotherapy diagnosis, precautions and contraindications to treatment procedures, the development of a treatment plan and the definition of parameters to monitor the results of treatment and to initiate treatment.

Additionally, subjective examination follows several specific objectives to support decisions regarding physical examination and initial treatment:

• Determination of the problem from the patient's perspective. This includes assessment of pain or other symptoms as well as the assessment of movement and movement control (dys)functions. Furthermore, the beliefs of the patient regarding causes and best treatment procedures, as well his sense of control on pain including chosen coping strategies, should be established.

• Defining subjective parameters which serve reassessment procedures. These parameters include information regarding pain sensation, activity limitations and participation restrictions, behavioural aspects such as coping strategies, use of medication and indication of psychosocial factors, which may hinder a recovery to full function.

• Determination of precautions and contraindications to physical examination and treatment procedures. The pain experience and the concomitant disability are indicative of specific precautions to examination procedures. Frequently this will be described within the constructs of irritability and severity.

• Generation of multiple hypotheses, to be tested during physical examination procedures and treatment interventions. The hypotheses categories have been listed in Table 7.3.

Information phase

In this phase the patient is informed about the scope of physiotherapy, as a specialty in the analysis and treatment of movement disorders, about the course of the first sessions, including the role of the assessment procedures employed. In this phase it is investigated if the patient is expecting physiotherapy as the treatment of his choice for his problem, if the patient understands the movement perspective of physiotherapists in problem solving processes and if certain reservations may exist regarding the therapy and the treatment setting, or if there is a lack of confidence about the treatment.

Subjective examination

The physiotherapist may decide to follow a more procedural approach to the interview, and/or to follow the line of thought of the patient (‘parallelling’) on the one hand or, on the other hand, to follow a more narrative approach to the interview, in which the patient is encouraged to tell the story of his illness from his perspective. Regardless of the style of interviewing, it is essential that the therapist keeps an overview of the information and organizes these accordingly into five groups as listed below.

1: Main problem It is vital to establish the current main problem from the perspective of the patient, expressed in the patient's words. In the case of a sacroiliac disorder the patient may complain about pain, a sense of tiredness in the leg, particularly during weight bearing activities.

As the pain may be of a sudden, sharp quality, some patients feel strongly restricted in their daily life activities. However, many patients complain of a pain that may not interfere strongly with the tasks of daily living as they are able to make compensatory movements.

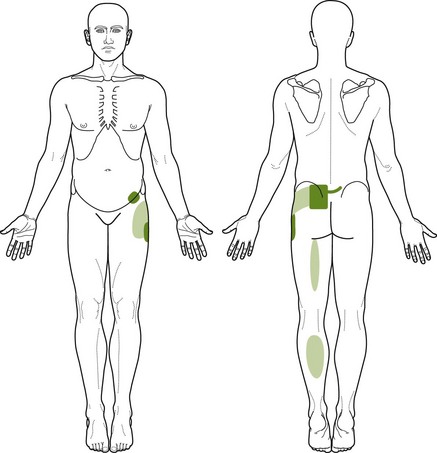

2: Area of symptoms A precise drawing of the areas of symptoms, as indicated by the patient, helps in the hypotheses-generation of the possible sources of symptoms and, at times, of the precautions and contraindications and neurophysiological pain mechanisms.

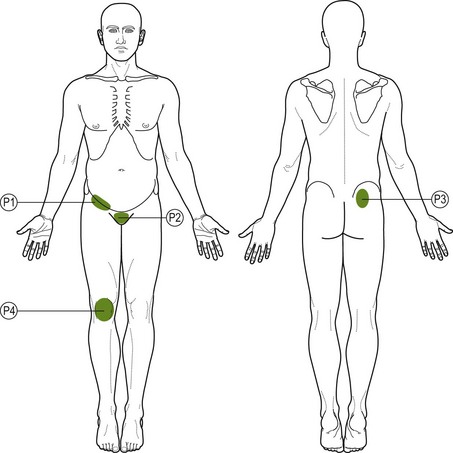

Symptoms arising from the SIJ are unlikely to cross the midline. The most frequently reported symptoms overlay the posterior aspect of the SIJ; symptoms may be referred into the buttock, groin, posterior thigh and even in the calf and foot (Fortin et al. 1994, Schwartzer et al. 1995, Mens et al. 1996). Figure 7.6 illustrates typical areas of symptoms.

Figure 7.6 Typical areas of symptoms related to the sacroiliac joint. Note the overlap with symptoms that may be referred from the lumbar spine.

It is well known that lumbar structures as well as hip tissues may produce similar pain and symptom distribution as the SIJ. Therefore the area of symptoms should never be relied on solely for diagnosis.

3: Behaviour of symptoms and activity-levels This phase of the subjective examination needs to be followed up with great care, as it is essential for the definition of precautions of physical examination and monitoring of treatment results in subsequent sessions. The following aspects need to be determined:

• Which activities are restricted due to the pain? These activities serve as parameter to monitor changes in the patient's complaint over the course of therapy. Furthermore it provides the therapist with information on deficits and resources of activities and participation in daily life.

• Often it is useful to know how the pain behaves over a course of 24 hours or even during a 7-day period. The patient and the therapist have an opportunity to learn if and how the symptoms are directly related to certain activities of the patient in the previous days before the symptoms occur.

• The most common aggravating factors for patients with PGP are related to unilateral weight bearing such as walking, climbing stairs, stepping off a curb, standing on one leg while dressing, as well as sitting, bending forward, lifting, turning in bed, lying supine with extended legs and getting up from a chair. This observation has been confirmed in a study of 394 women with peripartum pain (Mens et al. 1996; see Table 7.4).

Table 7.4

Activity restriction due to pain arising from the SIJ (Mens et al. 1996)

| ADL | % of patients |

| Standing for 30 min | 90 |

| Carrying a full shopping bag | 86 |

| Standing on one leg | 81 |

| Walking for 30 min | 81 |

| Climbing stairs | 79 |

| Turning over in bed | 74 |

| Having sexual intercourse | 68 |

| Riding a bicycle for 30 min | 63 |

| Bending forward | 62 |

| Getting into and out of bed | 62 |

| Driving a car for 30 min | 52 |

| Swimming | 51 |

| Sitting on a favourite chair for 30 min | 49 |

| Travelling by public transport | 46 |

| Lying in bed for 30 min | 8 |

• How does the patient cope with the pain? Is the patient taking an active or a more passive role in managing his symptoms? Even if patients seem to take a more passive role, they may intuitively choose useful strategies to diminish the symptoms. Often, even when patients state that they cannot influence the pain, they may instinctively choose certain positions, rub or hold certain areas or move the structure concerned in a certain way. Careful observation of the patient during the subjective and physical examination may demonstrate these unconscious behavioural patterns. They may become decisive in selecting directions of passive mobilization techniques and enhance self-management strategies.

Typically for sacroiliac disorders, patients may brace the pelvis by crossing their legs in sitting, by shifting the weight to the other buttock in sitting, by gently pushing the knees together in standing, by holding the pelvis with one or two hands while pressing the innominate anteriorly.

• It is essential to collect information in such detail that the therapist can almost visualize the way the patient moves once the pain occurs and what he or she does to reduce to pain.

• Furthermore, this phase of subjective examination may be useful to establish the general levels of activity of the patient during the day and during the week.

4: History (Hx) As the symptom distribution and the activities related to the pain may be provoked by structures other than the SIJ, the history can be most useful in indicating whether or not a sacroiliac disorder is a dominant contributing factor to the patient's pain and disability.

PGP is most commonly associated with pregnancy, trauma or inflammatory disorders (Vleeming et al. 2008):

• Questions regarding onset of the symptoms are essential. Symptoms related to pregnancy, the first few months post-delivery or increased symptoms with the second of third pregnancy strongly indicate the presence of a PGP disorder, possibly due to a lack of motor control mechanisms and, possibly, increased mobility of the SIJ.

• Details about a traumatic incident may give indications of the structures that may possibly be involved in the disorder. Trauma can include macro-trauma such as a car accident, a fracture of the pelvis or a fall on the buttocks. Microtrauma may occur with repeated strains or overuse, often associated with faulty postures, faulty movements and/or motor control impairments within the lumbopelvic –hip complex.

Restricted hip or lumbar spine movements may contribute to excessive strain and compensation of the sacroiliac joints. Repeated strains to the adductor muscle groups or hamstrings can also influence the pelvis and may lead to added strain on the symphysis pubis or sacroiliac joints.

Long standing morning stiffness (lasting longer than 2–3 hours) may be indicative of an inflammatory disorder.

5: Special questions (SQ) Special questions need to include information regarding general health status of the patient, unexpected weight loss, use of medication, results from possible laboratory findings and imaging findings as for example X-ray, MRI or CT-scans.

A medical history of family members may be useful, especially when suspecting arthritic/inflammatory disorders (e.g. rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis).

Specific screening questions regarding possible dysfunctions of the gastrointestinal, urogenital, cardiovascular, pulmonary, endocrine and nervous systems need to be incorporated in to the interview, particularly in cases of direct referral of the patient to the physiotherapist (Boissonault 2011, Goodman & Snyder 2007). Particularly fever, unexplained weight change, general fatigue, nausea/vomiting, bowel dysfunction, numbness, weakness, syncope, dizziness, night pain, dyspnea, dysuria, urinary frequency changes and sexual dysfunction may need further medical investigation (Boissonault 2011).

Questions regarding urinary incontinence should not be neglected as there is indication that incontinence is associated with increased risk of low back and PGP (Smith et al. 2006). Urinary incontinence may occur for various reasons. If the changes develop over a relatively short period of time, they may be indicative of a cauda equina lesion. If they develop over a longer period of time, gynaecological or urological investigations may be necessary. Stress incontinence is most often associated to insufficient control of the muscles of the pelvic floor.

Planning of the physical examination (‘structured reflection’)

Before embarking in the physical examination, a process of ‘structured reflection’ needs to take place to allow for a comprehensive examination. The following steps need to be considered and, preferably, recorded:

• Summary of the subjective examination:

have sufficient parameters to guide reassessment procedures been collected?

have sufficient parameters to guide reassessment procedures been collected?

is there enough information to make clear statements regarding contraindications and/or precautions to examination and treatment procedures?

is there enough information to make clear statements regarding contraindications and/or precautions to examination and treatment procedures?

• Have hypotheses regarding sources, contributing factors, pathobiological processes, precautions and contraindications been made explicit to help guide the dosage of examination procedures (which symptoms should be reproduced/avoided during physical examination; extent of test procedures – only until the onset of pain/testing into pain provocation; making use of only a few tests to prevent exacerbation/using complete examination procedures or even specific test combinations) and the exact course of the steps of examination procedures?

Physical examination

Refer to Box 7.1 for an overview of the physical examination.

Although the lumbopelvic–hip complex works as a functional unit and the pelvis cannot be studied in isolation during active/functional movements, the lumbar spine, hip and pelvis should be assessed individually with passive movements to correlate findings.

A thorough physical assessment helps identify the various impairments in the lumbopelvic–hip complex and the functional restrictions presented by a patient. Differentiation between lumbar pain and PGP is important in order to plan treatment accordingly.

Hypotheses should be generated based on the results of multiple tests as to what region/joint may be the source of pain and what the causes of the symptoms may be.

Observation

Analyzing gait can give valuable information about how the patient is transferring load through his pelvis and lower extremities. Here are some key elements to note:

• Minimal deviations of the head and body vertically and laterally (about 5 cm)

• No sign of Trendelenburg or compensated Trendelenburg

• Maintenance of good motor control and joint alignment of the lumbar spine, pelvis, hip, knee and foot

Common manifestations of poor motor control are:

Posture

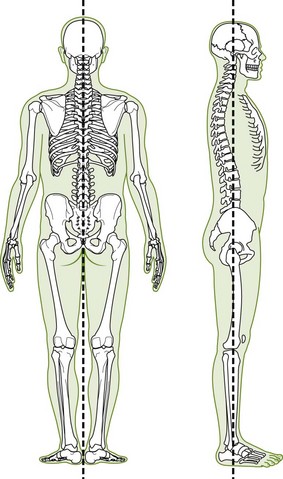

Observation of the pelvic girdle should include:

• Orientation of the sacrum about the horizontal and sagittal axes, and the sacrum's relationship to the lumbar lordosis in both standing and sitting

• Bony landmarks such as iliac crests, anterior and posterior superior iliac spines, greater trochanters and prominence of the femoral heads in the groin

• Position of the innominates relative to each other – no rotation should be observed (intrapelvic torsion)

• Position of the sacrum – should be slightly nutated (sacral base anterior) and should not be rotated (in both sitting and standing)

• Femoral heads should be centered in the acetabulum and should be symmetrical in standing and sitting

• Alignment of the femur, tibia and ankle/foot

• Differences in muscle bulk in the trunk, buttock and lower extremities

• Position of the thorax relative to the pelvis is also assessed for neutral spine position. The manubriosternal junction should be in the same coronal plane as the pubic symphysis and the anterior superior iliac spine of the innominates (Lee & Lee 2010). Postural alignment is illustrated in Figure 7.7.

Positional faults, on their own, are not necessarily related to the patient's symptoms and no conclusion can be drawn from these findings alone. The effect of correcting a positional fault may be more informative as to its link to the patient's symptoms. If, on correction, the patient's symptoms are reproduced, the posture can be considered to be antalgic, adaptive to the patient's condition. If, on correction, symptoms are improved then the posture may be maladaptive and attempts will be made to change it.

It is common for patients to adopt passive postures such as a sway-back position in standing (maximum nutation of sacrum), where the symphysis pubis sits anterior to the manubriosternal junction, and a slumped sitting position (counter-nutation of sacrum). Adopting these extreme postures for any length of time can lead to tissue overload and can cause symptoms. These patients will have to be shown and trained to adopt more neutral spine positions as these faulty postures may be a factor in perpetuating their symptoms.

Active movements of the trunk

Functional movements of the trunk will incorporate movement of the lumbar spine, hip as well as the pelvic girdle. The patient is first asked to demonstrate a movement or position that aggravates or reproduces his symptoms. The therapist then analyzes the strategies used by the patient when performing his specific movement.

Special attention should be given to the quality of movements and the apex of the curves as it is common to observe excessive range of motion (ROM) at one lumbar segment in the presence of a stiff hip or poor motor control and compensation of the pelvic girdle due to stiffness of the lumbar spine.

Forward bending: During forward bending, hip flexion should occur concurrently with lumbar flexion. The ilia should anteriorly tilt symmetrically over the hips with no relative rotation between them. The sacrum should remain in a nutated position throughout the range so relatively, both innominates should stay posteriorly rotated (Lee & Lee 2010). If failed load transfer occurs, where there is loss of optimal alignment/movement/control of one of the innominates, that innominate has been shown to anteriorly rotate relative to that side of the sacrum (Hungerford et al. 2004, 2007). The erector spinae muscle should be symmetrically active in the first part of the range and should relax in the latter part as more strain is taken up by the inert structures (Fig. 7.8).

Backward bending: During backward bending, there should be reversal of the thoracic kyphosis, controlled segmental extension of the lumbar spine (no hinges) and the innominates should posteriorly rotate symmetrically over the hips causing the hips to extend (Lee & Lee 2010). The sacrum should remain nutated and the innominates should stay posteriorly rotated. Again, if there is failed load transfer, the innominate on the affected side is often seen to anteriorly rotate relative to the sacrum (Fig. 7.9).

Side-bending: During side-bending of the trunk, the body should stay in the frontal plane. A small amount of movement of both innominates is expected as a physiological intrapelvic torsion occurs during side-bending. On side-bending to the left, the left innominate will anteriorly rotate slightly as the right innominate will posteriorly rotate. The sacrum will rotate to the right as it moves congruently with the lumbar spine which side-bends to the left and rotates to the right. The lumbar spine should show a smooth curve with no kinking (Fig. 7.10).

Rotation: During rotation of the trunk to the right, the sacrum should follow the lumbar spine and rotate to the right as the left innominate rotates anteriorly and the right innominate rotates posteriorly. The left leg should internally rotate in space and the left foot should pronate while the right leg should externally rotate in space and the right foot should supinate.

Movements from below upwards: As mentioned in Chapter 6, movements of the pelvis and lower lumbar spine can be assessed in standing by asking the patient to initiate movement through the pelvis first (from below upwards). The patient is asked to perform a posterior tilt, anterior tilt, lateral tilt (hip drop Fig. 7.11) and rotation of the pelvis relative to the lumbar spine. Some restrictions may be more obvious when the movements are tested this way and the pain response elicited may also be different.

Active movements of the hip

Quick screening tests involving the hip can be done in weight bearing to evaluate the presence of any restriction or reproduction of symptoms.

• Squatting can be done with the heels off and on the ground. This will assess full hip flexion in weight bearing. Note the amount of flexion in the lumbar spine as there might be excessive lumbar flexion if one hip has a flexion restriction.

• Lunging with one foot on the edge of a chair or low plinth will test for hip flexion and extension. Note for any compensation in the spine or innominate.

• Weight bearing tests on one leg are more functional tests and may be more useful in determining restrictions or reproduction of symptoms at the hip.

Patient starting position: standing on the affected leg, holding the physiotherapist's shoulder to maintain balance (Fig. 7.12).

Therapist starting position: standing in front of the patient.

Localization of forces: physiotherapist holds onto both innominates of the patient's pelvis

Application of forces: therapist guides the patient's pelvis in F/E direction, Ad/Ad direction and MR/LR direction.

• Active/passive movements in non-weight-bearing should also be assessed (refer to Chapter 7 in Hengeveld & Banks 2014 for more detailed information).

Functional tests of load transfer

These tests have evolved from the increased understanding of the role of the pelvis in load transfer and poor reliability and validity of many SIJ mobility tests. The stork test and the active straight leg raise test (ASLR) will be described here as they have both shown acceptable inter-tester reliability. Other tests for load transfer have also been described in the literature. O'Sullivan and Beales (2007a, 2007b) use the prone leg lift test and Lee and Lee (2010) also look at the squat test, stepping forward/backward, prone knee bend and prone hip extension. Lee and Lee (2010) also assess lateral tilts of the pelvis in both supine and standing to test load transfer through the symphysis pubis.

This test has also been described as the modified Trendelenburg test (Albert et al. 2000), a provocative test for the symphysis pubis. The test is positive when the pain is experienced in the area of the symphysis pubis.

Patient starting position: standing

Therapist starting position: kneeling behind the patient

Localization of forces: one hand on the innominate on the side of weight bearing with the thumb inferior to the posterior superior iliac spine (PSIS); the thumb of the other hand palpates the sacrum at either S2 or the ipsilateral inferior lateral angle (ILA) of the sacrum (Figs 7.13 and 7.14).

Figure 7.13 Position of the thumbs during the Stork test – left thumb inferior to the right inferior lateral angle (ILA) of the sacrum, right thumb inferior to the right PSIS.

Movement: the patient is asked to stand on one leg and to flex the contralateral hip and knee towards the waist. This test is done on both sides and the ability and effort required to do the test is observed. The transfer of weight should be done smoothly and the pelvis should remain in its original position.

Hungerford et al. (2007) noted that the pattern of intrapelvic motion is altered during the single-leg support in subjects with PGP. No relative movement should occur within the pelvis during load transfer whereas anterior rotation of the innominate relative to the sacrum occurs during weight bearing in the presence of PGP. These authors noted that the test showed good inter-tester reliability. They also suggest that the test is repeated ×3 to make sure the same pattern is observed each time.

Variations: The ability of the non-bearing innominate to rotate posteriorly relative to the ipsilateral sacrum can also be assessed by this test (Fig. 7.15; Hungerford et al. 2004). Lee & Lee (2010) suggest to assess the pattern of motion between the innominate and sacrum and to look for symmetry between both sides. Positioning for this test is done in exactly the same way as described above except the palpation is done on the non-weight bearing side. This test assesses active movement of the innominate relative to the sacrum and the results of this test must be correlated to the passive mobility tests.

Active straight leg raise test:

Patient starting position: supine, legs extended

Therapist starting position: standing next to the patient to observe the strategy that the patient will use to perform the test and to be in a good position to add compression to various parts of the pelvis

Movement: the patient is asked to lift one leg 20 cm from the bed and to note the degree of effort difference between each leg. The effort can be scored on a scale from 0 to 5 (Mens et al. 1999). The leg should raise effortlessly from the table and the pelvis should not move in any direction relative to the thorax or lower extremity. To be able to perform this test effortlessly, proper recruitment of both local and global muscles is necessary (Fig. 7.16).

Application of compression to the pelvis (bringing the two innominates together anteriorly) has been shown to reduce the effort necessary to lift the leg for peripartum patients (Mens et al. 1999). Varying the compression can assist the therapist to determine where more compression is needed functionally to help load transfer through the pelvic girdle (Lee & Lee 2010). Lee & Lee (2010) hypothesize that compression of different parts of the pelvis (ex. anterior compression, Figs 7.17 and 7.18, posterior compression, Fig. 7.19, or anterior compression on one side and posterior compression on the other side, Fig. 7.20) can simulate the work of various local muscles. The compression that is noted to be most helpful for the patient during the ASLR test should be kept in mind when planning treatment. On the other hand, the pelvic girdle is sometimes under too much compression and the patient will not do well or may find the task of lifting the leg even more difficult with increased pelvic compression.

Pain provocation tests

Several studies have looked at the interexaminer reliability of pain provocation, position and mobility tests for the pelvic girdle. Only pain provocation tests have shown reliability individually and particularly when clustered (Laslett et al. 1994, van der Wurff et al. 2000, Laslett et al. 2005, Robinson et al. 2007).

Laslett et al. (2005) have found that when any two of the four non-specific provocation tests (distraction, compression, thigh thrust, sacral thrust) are positive, the SIJ may be considered to be the source of pain. When all tests are negative, symptomatic SIJ pathology can be ruled out (Laslett 2007).

Numerous provocation tests have been described in the literature. Laslett et al. (2003) suggested the use of the following tests:

Albert et al. (2000) suggested:

Vleeming et al. (1996) and Ostgaard (2007) also suggested:

The posterior pelvic pain provocation test (P4 test; Ostgaard 2007): This test has been shown to have the highest sensitivity (Laslett et al. 2005). See Figure 7.21.

Figure 7.21 The posterior pelvic pain provocation test (P4 test), stabilizing the contralateral innominate.

Patient starting position: supine, hip at 90° flexion, knee flexed.

Therapist starting position: standing on the side to be tested, holding on to the patient's knee, stabilizing through the contralateral innominate by pressing down on the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS; Fig. 7.21) or stabilizing the sacrum posteriorly with the other hand (Fig. 7.22; Laslett 2008).

Figure 7.22 The posterior pelvic pain provocation test (P4 test), stabilizing the sacrum posteriorly.

Application of forces: a posterior force is applied through the femur.

This test is interpreted as being positive when pain is provoked in the SIJ area on the ipsilateral side.

Distraction test (anterior distraction and posterior compression test): This test has been shown to be most specific (Fig. 7.23; Laslett et al. 2005).

Patient starting position: supine, a small pillow under the knees to keep the lumbar spine more neutral.

Therapist starting position: standing at the level of the patient's thighs, facing the patient's head; heel of the hands on the medial aspect of the ASIS with hands crossed, forearms parallel.

Application of forces: a slow, steady, posterolateral force is applied through the ASIS thus distracting the anterior part of the SIJ and compressing the posterior part. The force should be maintained as the patient is asked about reproduction and localization of pain. It is important to apply enough force during this test.

Compression test (anterior compression and posterior distraction; Fig. 7.24):

Patient starting position: sidelying, hips and knees flexed.

Therapist starting position: standing behind the patient at the level of the patient's pelvis, both hands over the anterolateral iliac crest.

Application of forces: a slow, steady, medial force is applied through the innominate thus compressing the anterior part of the SIJ and distracting the posterior part. The force should be maintained as the patient is asked about reproduction and localization of pain. The test should be done on both sides. It is also important to apply enough force when doing this test.

Variations: this test can also be done in supine as per the distraction test. The therapist places her hands on the lateral aspect of both iliac crests and a medial force is applied to both innominates.

Gaenslen's test (Fig. 7.25):

Patient starting position: supine, near the edge of the bed, flexion of the hip and knee on the side to be tested.

Therapist starting position: standing on the side where the hip is extended.

Application of forces: the patient's hip is fully flexed onto their abdomen and held there by the patient as the therapist adds overpressure while the opposite thigh is slowly hyperextended by the examiner over the edge of the bed with overpressure over the knee.

This test is positive when it reproduces pain on the tested side (the flexed side).

Sacral thrust test (Fig. 7.26):

Patient starting position: prone.

Therapist starting position: standing, both hands over the dorsal aspect of the sacrum.

Application of forces: a pure posteroanterior pressure is applied to the sacrum. The force should be maintained as the patient is asked about reproduction and localization of pain.

Patrick's Faber test (Fig. 7.27):

Patient starting position: supine.

Therapist starting position: standing on the side of the pelvis to be tested, stabilizes the opposite ASIS.

Application of forces: the heel of the patient's leg is placed on top of their opposite knee so the hip is flexed, abducted and externally rotated (f/ab/er) and gentle overpressure is applied to the knee.

The test is positive when it reproduces pain either in the SIJ or the symphysis pubis as stress is placed on both joints during this test.

Long dorsal SI ligament test (Fig. 7.28; Vleeming et al. 1996, 2002):

Patient starting position: prone (sidelying in pregnancy).

Therapist starting position: standing.

Application of forces: the long dorsal SI ligaments are palpated directly under the caudal part of the PSIS.

The test is positive when pain or tenderness is reproduced on palpation.

Variations: Lee & Lee (2010) have suggested palpation of the ligament as a counter-nutation force is applied to the sacrum (P/A movement on the apex of the sacrum) as this increases the stress put on the long dorsal SI ligament.

Palpation of the symphysis pubis (Fig. 7.29):

Passive tests

According to Albert et al. (2000), the low reliability of the mobility tests may be related to the skills of the examiners and the lack of standardization of the tests. Hopefully some of these tests will eventually become more refined and more reliable. In the meantime, the therapist must continue to use these passive tests and reason through the findings of multiple tests before drawing any conclusion from the examination as no single test should be interpreted in isolation.

Positional tests

Positional analysis of the pelvic girdle should be evaluated prior to assessing joint mobility as a difference in mobility may just be a reflection of a different bony starting position. The pelvis is subjected to multiple force vectors from the muscles that attach to it and these can impact on its position. Positional tests should be done in supine and prone. It is suggested by Lee & Lee (2010) that the entire hand is used to more accurately assess the position of the innominates rather than only visualizing one point of the bone. Again it is important to note that positional faults on their own are not necessarily related to the patient's symptoms and that no conclusion can be drawn from these findings alone.

Position of the innominates in supine (Figs 7.30 and 7.31):

Patient starting position: supine, legs extended.

Therapist starting position: standing, palpates the anterior aspect of both innominates with the heels of the hands, the rest of the hand resting on the lateral aspect of the innominates. Note any difference in positioning of the innominates, any torsion or shear of one innominate relative to the other. The position can be confirmed by placing the thumbs on the inferior aspect of the ASIS.

Position of the pubic tubercles:

Patient starting position: supine, legs extended.

Therapist starting position: standing, the heel of one hand is used to palpate the cranial aspect of the left and right superior pubic rami, noting any difference in the height of one pubic ramus relative to the other, in either a craniocaudal or an anteroposterior direction. The position can be confirmed by placing the thumbs above each pubic ramus.

Position of the innominates in prone (Fig. 7.32):

Patient starting position: prone, legs extended

Therapist starting position: standing, palpates the posterior aspect of both innominates with the heels of the hands on the inferior aspect of the PSIS and the rest of the hand on the back of the innominates. Note any difference in positioning. The position can be confirmed by placing the thumbs on the inferior aspect of the PSIS.

The ischial tuberosities can also be used to confirm any vertical shear of one innominate relative to the other. The most inferior aspect of the ischial tuberosities is palpated bilaterally with the thumbs.

Position of the sacrum in prone (Figs 7.33 and 7.34):

Patient starting position: prone, legs extended.

Therapist starting position: standing, palpates the dorsal aspect of the inferior lateral angles of the sacrum (lateral edge of the sacrum at the level of S5) with the thumbs to assess for any rotation of the sacrum. According to Lee and Lee (2010), this bony point appears to be more reliable for assessing the position of the sacrum as the sacral base depth can be influenced by the size and tone of the sacral multifidus.

Passive mobility tests

Passive physiological movements of the innominate:

A: Posterior rotation of the innominate (Fig. 7.35):

Patient starting position: sidelying, the bottom leg is extended (to keep the lumbar spine more neutral) and the top leg is flexed.

Therapist starting position: standing in front of the patient's hips, supports the bent leg, one hand is placed on the posterior surface of the ischeal tuberosity and the heel of the other hand is placed over the anterior iliac spine.

Application of forces: by using both arms simultaneously, the posterior rotation of the innominate is assessed by pushing the anterior iliac spine posteriorly and superiorly as the ischeal tuberosity is pulled down and forward.

The quality of the movement, the resistance through range, the end-feel as well as any pain provocation are noted and compared to the same movement on the other side.

B: Anterior rotation of the innominate (Fig. 7.36):

Patient starting position: sidelying, the bottom leg is flexed to 90° (to keep the lumbar spine more neutral) and the top leg is only slightly flexed, closer to extension.

Therapist starting position: standing behind the patient, one hand is placed on the anterolateral margin of the iliac crest and ASIS of the top leg, and the heel of the other hand is placed under the PSIS and buttocks of the same leg.

Application of forces: by using both arms simultaneously, the anterior rotation of the innominate is assessed by pushing the PSIS superiorly and posteriorly as the anterolateral margin of the iliac crest and ASIS is pulled forward and down.

The quality of the movement, the resistance through range, the end-feel as well as any pain provocation are noted and compared to the same movement on the other side.

Passive accessory movement tests

When testing movement, Maitland (1986) always emphasized the importance of relating range with the symptom response and vice versa. On testing accessory movement, emphasis is placed on picking up R1 (1st barrier of resistance) at the end of the neutral zone (Panjabi 1992), and the resistance through range from R1 to R2, the elastic zone. The behaviour of the resistance and where the resistance starts in the range will be compared for each SIJ. Buyruk et al. (1995a, 1995b) and Damen et al. (2002) used Doppler imaging of vibration (DIV) to measure stiffness of the SIJ and noted that the joint stiffness is variable and therefore the ROM between individuals is likely to be variable. They found that the stiffness values were symmetrical in healthy subjects but not in those with PGP.

A: Oscillatory movements on the innominate and sacrum:

Patient starting position: prone or supine, legs straight.

Therapist starting position: hands on different parts of the sacrum or innominate.

central oscillatory P/A movement over the sacrum at S1 (base), S3 (middle), S5 (apex) (Fig. 7.37)

central oscillatory P/A movement over the sacrum at S1 (base), S3 (middle), S5 (apex) (Fig. 7.37)

unilateral oscillatory P/A movement over the base of the sacrum at S1 on each side (Fig. 7.38)

unilateral oscillatory P/A movement over the base of the sacrum at S1 on each side (Fig. 7.38)

unilateral oscillatory P/A movement over the inferior lateral angles (level of S5) on each side (Fig. 7.39)

unilateral oscillatory P/A movement over the inferior lateral angles (level of S5) on each side (Fig. 7.39)

P/A movements can also be applied to the PSIS (Fig. 7.40)

P/A movements can also be applied to the PSIS (Fig. 7.40)

lateral movement of the PSIS (Fig. 7.41).

lateral movement of the PSIS (Fig. 7.41).

• P/A, A/P and lateral movements of the coccyx

• craniocaudal movement innominate relative to sacrum – one hand on the base of the sacrum and the other on the ischeal tuberosity; one hand on the iliac crest and on the apex of the sacrum

• unilateral A/P movement on the pubic ramus adjacent to the symphysis pubis (Figs 7.42 and 7.43)

• Craniocaudal movement of one pubic ramus adjacent to the symphysis pubis (Fig. 7.44).

For all of the above, varying angles of the accessory movements can also be assessed. The quality of the resistance as well as any pain provocation are noted and compared with the same movement on the other side.

B: Passive mobility/stability of the SIJ in the anteroposterior plane (Fig. 7.45; Hungerford et al. 2004, Lee & Lee 2010):

Patient starting position: crook lying, legs supported (in this position, the sacrum is in counter-nutation so the joint is in a loose-packed position), arms by the side to decrease the influence of myofascial tensions and to ensure maximum relaxation of the superficial muscles which can influence joint play motion.

Therapist starting position: the tips of the fingers of one hand are placed posteriorly in the sacral sulcus just above and medial to the PSIS; the heel of the other hand is placed over the ipsilateral ASIS (Fig. 7.46).

Localization of forces: the therapist must first find the plane of the joint as this is very variable between individuals; a gentle oscillatory force is applied to the ASIS in an A/P direction with slight medial/lateral inclinations until the plane of least resistance is found.

Application of the forces: Once the plane is found, a gentle A/P translation force (a parallel movement) is applied to the innominate relative to the sacrum and attention is paid to when R1 starts, to determine the neutral zone. The quality of the resistance from R1 to R2, the elastic zone, is then assessed as well as the end-feel to the movement. The symmetry of the quantity and quality of the movement is compared between both sides. It is important to apply a gentle pressure when doing this test in order to pick up R1 and to feel the resistance through range. If the movement is done too hard, only R2 will be felt and no comparison of the symmetry of the resistance through range will be possible.

Variations: The muscular system can increase compression across the SIJ (Richardson et al. 2002, van Wingerden et al. 2004). Lee and Lee (2010) suggest that hypertonicity of certain muscles can compress parts of the SIJ and prevent a parallel glide only at that part of the joint. On testing the A/P translation at the SIJ, they divide their movement into superior, middle and inferior to test the movement at different parts of the joint. According to these authors, the superior part of the SIJ can be compressed by hypertonicity of the superficial fibres of multifidus; the inferior part can be compressed by ischiococcygeus and piriformis can compress all three parts of the joint. Specific palpation of those muscles will help in confirming clinical hypotheses as to why there may be asymmetry when testing movement in this plane.

Interpretation of findings:

Stiff/fibrotic SIJ: very little neutral zone may be felt as R1 will be felt early. The resistance between R1 and R2 will increase rapidly so the elastic zone will be decreased and the end-feel will be quite firm.

Lax/loose SIJ: R1 will start later than expected (increased neutral zone), the distance between R1–R2 will be increased and possibly a softer end-feel will be felt. This may imply that there is lack of form or force closure of the joint. Panjabi (1992) describes that the neutral zone may be increased due to injury, articular degeneration and/or weakness of the stabilizing musculature. He also states that this is a more sensitive indicator than angular ROM for detecting instability.

C: Passive mobility/stability of the SIJ in the craniocaudal plane (Fig. 7.47; Hungerford et al. 2004, Lee & Lee 2010):

Patient starting position: crook lying, leg supported by the therapist.

Therapist starting position: the tips of the fingers of one hand are placed posteriorly in the sacral sulcus just above and medial to the PSIS, the other hand is placed on the patient's ipsilateral knee.

Localization of forces: the therapist must first find the plane of the joint as stipulated in the previous technique; a gentle oscillatory force is applied to the patient's knee in a cranial direction with slight medial/lateral inclinations of the leg until the plane of least resistance is found.

Application of the forces: Once the plane is found, a gentle cranial translation force is applied to the innominate relative to the sacrum via the knee. Attention is paid to when R1 starts, to determine the neutral zone, and to the quality of the resistance from R1 to R2, the elastic zone. The symmetry of the quantity and quality of the movement is compared between both sides. It is important to apply a gentle pressure when doing this test in order to pick up R1 and to feel the resistance through range. If the movement is done too hard, only R2 will be felt and no comparison of the symmetry of the resistance through range will be possible.

Interpretation of findings:

Stiff/fibrotic SIJ: very little neutral zone may be felt as R1 will be felt early. The resistance between R1 and R2 will increase rapidly so the elastic zone will be decreased and the end-feel will be quite firm.

Lax/loose SIJ: R1 will start later than expected (increased neutral zone), the distance between R1–R2 will be increased and possibly a softer end-feel will be felt. This may imply that there is lack of form or force closure of the joint. Panjabi (1992) describes that the neutral zone may be increased due to injury, articular degeneration and/or weakness of the stabilizing musculature. He also states that this is a more sensitive indicator than angular ROM for detecting instability.

The above two tests have yet to be evaluated for validity, sensitivity and specificity for impaired function of the lumbopelvic complex (Lee & Vleeming 2007) but are very useful clinically and help in clinical reasoning when directing treatment.

Form closure/force closure testing

Form closure of the joint (bones, joints, capsules, ligaments) is also assessed when testing passive mobility at the SIJ. Lee & Lee (2010) suggest that if the SIJ is felt to have an excessive neutral zone, the joint can be closed-packed by gently pushing the sacrum into full nutation by applying an anterior force with the fingers of the hand on the sacrum while simultaneously rotating the innominate posteriorly. The A/P translation is then reassessed and no movement should occur when the articular system restraints are intact. If there is increased laxity in neutral but stability in the closed-pack position, a motor control impairment may be present. Force closure (the myofascial system) should then be assessed by asking the patient to co-contract the local muscles of the trunk and the translation is retested.

If there is still increased laxity in the closed-pack position of the SIJ (full nutation), this indicates that form closure is not intact. Force closure can then be assessed as stated above. If there is increased stiffness of the joint with co-contraction of the local muscles, emphasis of treatment will be placed on motor control and the patient may also benefit from wearing a SI belt until his stability has improved. If there is no change in the joint stiffness with muscle activation, this means that there is loss of integrity of the articular restraints and the deep muscles cannot compensate and control motion in the neutral zone. In this case, the prognosis is not as good, the patient will have to be referred for a medical consult as he could possibly benefit from prolotherapy (Cusi et al. 2010, Dorman 1997).

Palpation: The objectives of palpation are to assess for:

• Changes in temperature or evidence of sweating

• Any soft tissue changes (superficial to deep; general to localized)

• Any movement anomalies on passive accessory movements (relating them to the findings on passive physiological movement testing)

• Any painful response to soft tissue palpation and passive accessory movements.

Palpation should include:

• Skin temperature, sweating, skin rolling

• The different layers of muscles for soft tissue changes such as thickening, hypotonicity and hypertonicity

• Posterior muscles such as the glutei, piriformis, ischiococcygeus, external rotators of the hip, hamstrings, erector spine, and multifidi

• Anterior muscles such as adductors, rectus abdominis, internal oblique, external oblique, rectus femoris, tensor fascia lata, psoas

• The sacrotuberous ligament, the long dorsal SI ligament, the sacrococcygeal area, the symphysis pubis and groin

• The neural structures such as the sciatic nerve, the femoral nerve, and the lateral cutaneous nerve of the thigh

• The linea alba for its integrity and tension – especially in postpartum women who present with PGP and/or urinary incontinence.

All areas of increased tenderness should be noted and correlated with other examination findings. These can also be used in re-assessment.

Motor control (force closure)

In many low back and pelvic problems, a lack of motor control can play a major role in the maintenance of symptoms.

Bergmark (1989) classified muscles as being either local or global muscles. The local muscles are deep, segmental, are suited to apply compression across joints and are referred to as stabilizers. The global muscles span many segments or regions of the body and have a dual function of being movers and general stabilizers.

Dysfunction of the local muscle system can present as:

Dysfunction of the global muscle system:

• Hypertonicity, co-contraction, dominance

• Non-recruitment, delayed activation, weakness

Patient starting position: supine, hips and knees bent.