Management of lumbar spine disorders

Introduction

Low back pain is characterized by pain and discomfort localized below the costal margin and above the inferior gluteal fold, with or without leg pain (Burton et al. 2009). Low back pain is a part of everyday life in Western industrialized countries and will affect 80% of all adults in their lifetime (Nachemson & Jonsonn 2000). Acute low back pain normally settles within 4–6 weeks, but the majority of people often will experience recurrence at some time or other (Burton et al. 2009). In a small percentage of cases pain becomes persistent and impacts significantly on healthy living and health care costs (Burton et al. 2009).

Although the latter may seem a relatively small percentage, the prevalence of chronic disability due to (non-specific) low back pain (NSLBP) increased significantly in Western industrialized countries in the last two decades of the 20th century. This has led to a discussion on the basic assumptions and paradigms regarding causes of the pain and disability, treatment and research involved (Borkan et al.1998, Waddell 2004) and to the development of programmes to the secondary prevention of chronic disability due to low back pain.

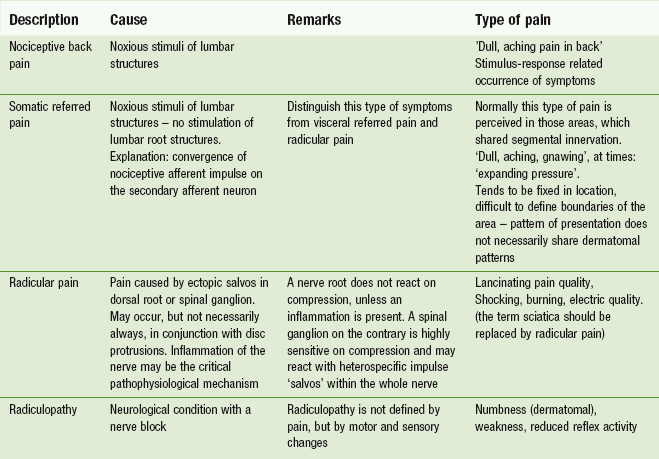

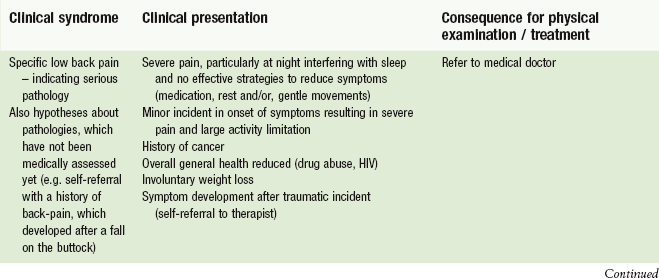

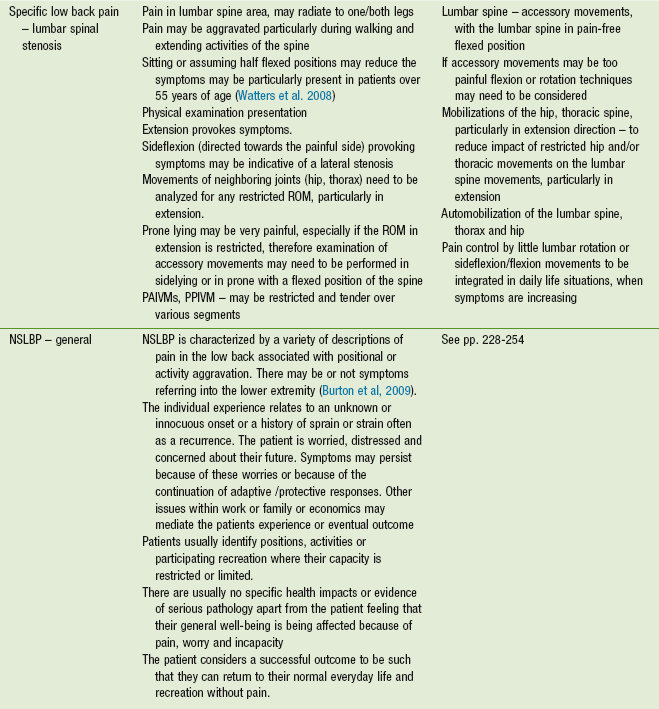

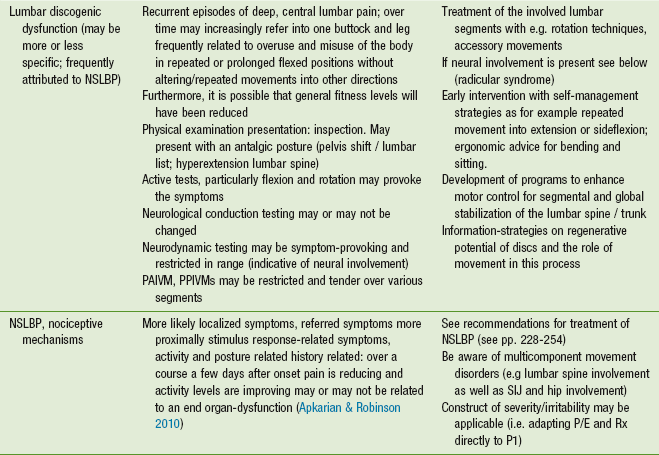

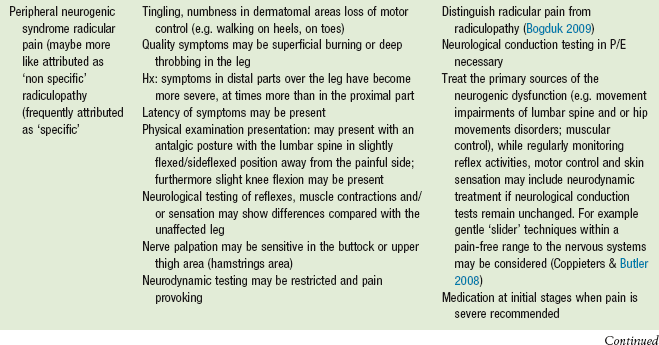

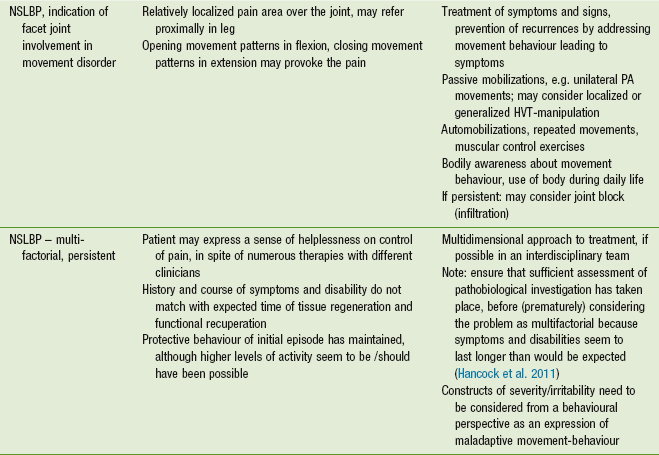

If serious pathologies, such as cancer, fractures, visceral pathologies, systemic inflammation, infection or severe neurological deficits can be ruled out as a source of the pain, it has been suggested NSLBP should be de-medicalized and patients' complaints should be grouped according to symptoms into four categories (see Table 6.1; International Paris Task Force on Back Pain: Abenhaim et al. 2000).

Table 6.1

Abenhaim et al. (2000) defined four categories of non-specific low back pain based on patients' complaints. Recommendations have been given for the treatment of the different categories

Several guidelines have been developed over the years (Airaksinen et al. 2004, Van Tulder et al. 2006, Vleeming et al. 2008), in which it has been recommended to stay as active as possible and to reduce rest or bed rest to a minimum (Abenhaim et al. 2000). The role of physiotherapeutic care has been discussed in relatively broad terms, but without detailed description and recommendation of the kind of passive movements and exercises in acute, subacute and chronic phases of NLSBP. Nevertheless, the Paris Task Force on Low Back Pain suggests in subacute intermittent and recurrent low back pain to encourage patients to follow an active exercise programme, as well as in chronic low back pain to perform physical, therapeutic or recreational exercises (Abenhaim et al. 2000). Furthermore, the Paris Task Force concludes that scientific evidence exists in favour of strength training, stretching and fitness, which must be based on a medical assessment by a competent professional and on the patient's compliance to the prescribed course of action (Abenhaim et al. 2000, p.3S).

Demedicalization and conceptualization of NSLBP

Sheehan (2010), among others, recognized the need to de-medicalize low back pain and emphasized the need for such a condition to be managed in the community rather than hospitals. Waddell (2004) recognized the inadequacies of a back pain revolution driven by the biomedical model of diagnosis and treatment. Waddell also made the medical communities aware of the consequences of medicalization of low back pain and its psycho-socioeconomic impact on Western industrialized populations. He suggested following a bio-psychosocial paradigm in the management of low back pain disorders (Waddell 1987). Chronic NSLBP is associated with a combination of physical, cognitive, social, behavioural, life style and neurophysiological factors. The latter with changes in processes of the peripheral and central nervous system. Taken these factors together, they have the potential to maladaptive cognitive behaviours (as fear avoidance, catastrophizing, unfavourable beliefs), pain behaviours (as communication and avoidance), and movement behaviours, leading to a vicious circle of ongoing pain sensitization and disability (O'Sullivan 2011).

Burton et al. (2009) recommended that the focus of prevention and management of NSLBP is directed towards physical activity and education. National strategies on prevention and management of low back pain have also placed conservative measures at the forefront of policy (Briggs & Buchbinder 2009, NICE 2009). Briggs & Buchbinder (2009) also recognized that the most important aspect of low back pain lays in its consequences rather than in the mere the fact that it exists. NICE (2009) highlights the need for individualized, patient-centred, needs-based management of NSLBP.

Policy makers therefore need to re-think what de-medicalization means to health care professions, to individual people, to populations, particularly in Western industrialized countries and to societies as a whole. Furthermore, it seems necessary to analyze those factors contributing to NSLBP and disability and conceptualize them in subgroups for treatment and better-aimed research efforts (Kent et al. 2009a).

One may learn from history how to approach such a dilemma in relation to health care, healthy living, promotion of healthy life expectancy as well as the financial and governmental consequences of low back pain in society. Low back pain was formally known as ‘lumbago’ or ‘muscular rheumatism’ (Gowers 1904). In the modern era lumbago is being used as a partner term for low back pain on many health care web pages. The term lumbago is a term which may suit de-medicalization well. It is non-threatening and places the condition in its true context of non-specificity. Compare this with terms like ‘slipped disc’, ‘degenerating vertebrae’, ‘trapped nerve’ etc., which are all terms used specifically for a non-specific condition. The consequences of the term lumbago are also less impacting on the individual. Moseley (2004) demonstrates a strong association between a sense of threat (e.g. knowledge that you have been told you have a crumbling disc) and pain perceptions. The road to de-medicalization is, therefore, in the terminology used. Lumbago seems to be fashionable again as a means of explaining pain experienced between the costal margins and the inferior gluteal folds.

The best way to treat low back pain, as reported by the HEN (Health Evidence Network) associated with WHO/Europe (2000), is:

… by staying active, returning to work, and exercising at an appropriate and increasing intensity. Anti-inflammatory and muscle relaxant drugs offer effective pain relief.

(WHO/Europe 2000, p. 1)

Back pain and its consequences are not isolated physical problems, but are associated with social, psychological, and workplace-related factors such as stress, worry, and anxiety; effective prevention and treatment must take these into account. Dealing with this situation can play a decisive role in preventing the development of chronic back pain.

(WHO/Europe 2000, p. 1)

A shift in culture about low back pain therefore needs to continue to evolve. This shift should move away from a reductionist, biomedical model, in which numerous interventionist pathways as medications, radiological examinations, injections and surgical interventions, may heighten patients' expectations and demands, ultimately leading to a dependency upon all different interventions. The alternative model should be based upon the viewpoint that low back pain is a problem of painful movements and movement-sensitivity, even though structural changes and some pathology may be present. In this model it is essential to consider the following aspects:

• Support recovery from injury or strain

• Gradually expose or reintroduce the structures and the patient to loading

• Condition the lumbar spine and associated structures

• Gradually condition to recover capacity and performance

• Use movement as a painkiller-evidence

• Use passive movement to support tissue and cellular function, as well as to introduce sensomotor learning processes towards active movement

• Creating independency and self-advocacy rather that creating dependency.

Policy makers also need to recognize which health care professions are best placed to lead on design of individual exercises and activity programmes and the delivery of non-threatening, de-medicalized information about lumbago and its potential consequences. As stated in an Australia based study, it seems that professions linked to manual therapy more likely connect subgroups of NSLBP to different treatment needs than primary care medical practitioners (Kent et al. 2009b). Health care professions such as physiotherapy are now mature enough to lead on policy supported by medical needs such as prescription medication and diagnostic imaging (rather than the other way round). Physiotherapists are best placed to ensure that individuals who experience lumbago move quickly from health care support back into healthy living. In effect, lumbago has become a public health issue rather than a medical issue.

The route to de-medicalization of NSLBP, therefore, is:

• Health care led supported by medical practitioners, who are skilled in guiding patients towards an active life style

• Early transition from health care needs to healthy living

• An emphasis on management to restore physical capacity and performance with less emphasis on biomedical diagnosis, medication and diagnostic imaging

• Embed the management of low back pain within the public health domain rather than the domain of health services

• Non-specific classification as, for example, using the term lumbago as well as the development of research classifications related to movement capacity and performance to guide research endeavours.

Conceptualization

As discussed in the previous paragraph, it seems necessary to define de-medicalization of NSLBP in greater depth. As a consequence, the conceptualization of the factors contributing to the development and maintenance of NSLBP, including its clinical assessment and treatment, should be investigated. This should be discussed in systematic studies and clinical practice. Also it appears that decisions on a political level are necessary whereby health care professions should play a pivotal role in the prevention and treatment of NSLBP and associated disability.

Some studies have been designed around the question of how clinicians perceive the nature of NSLBP.

Kent et al. (2009a) concluded, based on questionnaire information from 544 attendees at major conferences on low back pain in Europe and Australia, that consensus between different groups of clinicians existed on the following points:

• NSLBP is more likely to be an expression of numerous conditions rather than one single condition. This has implications for systematic studies. Currently many studies include heterogeneous cohorts of persons with NSLBP. Therefore, external validity of the studies suffer and will lead to only limited generalizability to clinical practice.

• Most respondents preferred to sub group NSLBP on the basis of a cluster of symptoms and signs rather than based on patho-anatomic changes.

• Pain, physical impairment (range of movement [ROM], muscle strength), activity (ability to perform activities of daily living e.g. sitting, walking standing, lifting), participation (abilities to perform social roles such as in work, family, hobbies, social contacts) and psychosocial function (e.g. depression, anxiety, coping, fear avoidance beliefs) were considered essential aspects of clinical assessment of the patients concerned and needing different, individualized approaches to treatment.

Furthermore in another Australia based study, it appears that primary clinicians such as manual therapists, chiropractors and osteopaths often link the subgroups to different treatment needs more than to medical practitioners (Kent et al. 2004).

Clinical assessment

The clinical assessment of persons with low back and/or leg pain should encompass various aspects of clinical analysis regarding pathobiological processes, movement analysis and contributing psychosocial factors. Furthermore, the clinician needs to incorporate different paradigms or perspectives in their clinical reasoning processes in order to be able to develop a comprehensive, meaningful, individualized treatment programme for the patient.

If a person presents with low back and/or leg pain, the clinician should consider all of the following points:

• The presenting dysfunction, referring to nociceptive pain mechanisms, which are in direct relationship to patho-anatomical and pathophysiological dysfunctions in bodily tissues (‘endorgan-dysfunction’, Apkarian & Robinson 2010).

• Within this perspective, the clinician is evaluating whether serious pathologies such as cancer, fractures, visceral pathologies, systemic inflammation, infection or severe neurological deficits may be present, which require specialized medical care. If serious pathologies can be ruled out, possible tissue processes may need to be considered as a precaution to (physiotherapeutic) treatment. Additionally, in the absence of contra-indications and precautions to physiotherapeutic treatment, the physiotherapist may have certain structures in mind, which may be contributing to the clinical pattern of the movement disorder of the patient, while considering treatment options (e.g. it may be possible in the treatment of a movement disorder of a person, that physiotherapists select, next to other techniques, rotation of the lumbar spine as a first treatment technique, because of the recognition of a movement disorder based on a discogenic dysfunction).

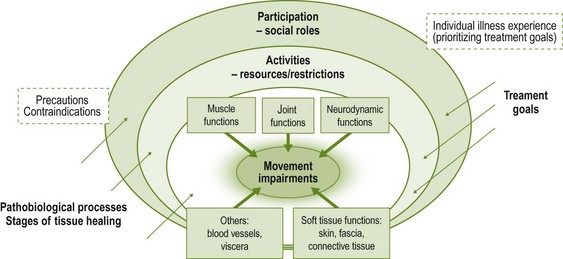

• If serious pathologies can be ruled out, the central core of clinical assessment should be the analysis of the movement disorder, the movement capacity and the movement potential of the patient (Cott et al. 1995; see also Chapters 1 and 2 of volume 2).

• The movement diagnosis may be expressed in the terms of levels of functioning as described in the International Classification of Functioning, Disabilities and Health (ICF; WHO 2001). Information on the movement capacity and restrictions may be found mainly during the subjective examination and observation of these, while the more specific physical examination procedures will inform the NMS-physiotherapist about the level of local movement (dys)functions (impairments).

• Information regarding movement capacities on the levels of function, activity and participation serves as a basis for the collaborative definition of treatment goals with the patient. Pathobiological processes may define precautions to the therapeutic objectives, while psychosocial aspects of the individual illness experience may be decisive in the treatment priorities and the integration of other therapeutic measures as for example patient education and the development of coping strategies as a means of patient-empowerment (Fig. 6.1).

Figure 6.1 The analysis of movement dysfunctions should incorporate the current movement capacities of a person on function, activity and participation levels as described in the International Classification of Functioning, Disabilities and Health (ICF, WHO 2001). Adapted from Hengeveld (1999) with permission.

• Although numerous practice guidelines recommend the assessment of functional activity levels and psychosocial contributing factors, it appears that between various primary care professions considerable difference is present in the utilization of assessment tools and in the focus on activity levels. In a study between physiotherapists, manipulative physiotherapists, osteopaths, chiropractors, general medicine and musculoskeletal medicine it was shown that the assessment of pain and physical impairment, as for example ROM, was a more common denominator between professional disciplines, while activity limitations and psychosocial function were less commonly assessed, with marked differences between groups. It has been recommended to standardize procedures, including the assessment of activity levels and psychosocial factors, as this information may be prognostically important and useful for outcome assessment. Furthermore the information from activity levels and psychosocial factors should aid in the identification of subgroups, requiring different treatment (Kent et al. 2009b)

• In order to enhance standardization in assessment, the International Paris Task Force on Back Pain summarized criteria to assess and decide upon meaningful therapeutic goals regarding optimal mobility and optimal performance of activities of daily living. They are based on selected functional and quality of life indexes, such as The Nottingham Health profile, Health Assessment Questionnaire, Sickness Impact Profile, SF-36, Roland Morris Questionnaire, Oswestry, Quebec Back Pain Disability scale (Quebec Task Force on Spinal Disorders, 1987), Dallas Pain Questionnaire (Abenhaim et al. 2000).

• Criteria for optimal mobility:

able to walk for several hours or several kilometres

able to walk for several hours or several kilometres

capable of remaining seated for several hours; however, within a lifestyle where sitting is interrupted regularly and preferably where sitting does not occur for the majority of the day

capable of remaining seated for several hours; however, within a lifestyle where sitting is interrupted regularly and preferably where sitting does not occur for the majority of the day

able to remain standing for more than 1 hour

able to remain standing for more than 1 hour

not having to go to bed or lie down to rest; not having to get out of, or turn over in, bed because of pain

not having to go to bed or lie down to rest; not having to get out of, or turn over in, bed because of pain

capable of climbing several flights of stairs

capable of climbing several flights of stairs

able to go down stairs frequently

able to go down stairs frequently

able to travel for over 2 hours; able to open a car door; get in and out of cars.

able to travel for over 2 hours; able to open a car door; get in and out of cars.

• The criteria of optimal performance of activities of daily living are listed as follows (Abenhaim et al. 2000):

lean forward without difficulty; lean over a sink for 10 minutes

lean forward without difficulty; lean over a sink for 10 minutes

bend over, kneel and crouch without difficulty; pick up objects from the ground without support

bend over, kneel and crouch without difficulty; pick up objects from the ground without support

get dressed and undressed, putting on socks/stockings and shoes without difficulty

get dressed and undressed, putting on socks/stockings and shoes without difficulty

wash oneself completely without difficulty, wash one's hair, brush one's teeth, get in and out of the bath tub

wash oneself completely without difficulty, wash one's hair, brush one's teeth, get in and out of the bath tub

run errands without difficulty; pick up bags weighing at least 2 kg without difficulty

run errands without difficulty; pick up bags weighing at least 2 kg without difficulty

do housework without difficulty or resting, do the laundry, vacuum, move tables, make the bed, bend over to clean the bathtub, not avoiding heavy housework

do housework without difficulty or resting, do the laundry, vacuum, move tables, make the bed, bend over to clean the bathtub, not avoiding heavy housework

stretch out one's arm to lift heavy or light objects located on the ground or above one's head; reaching a high shelf; carrying a large valise.

stretch out one's arm to lift heavy or light objects located on the ground or above one's head; reaching a high shelf; carrying a large valise.

Individualized assessment of persons with low back pain may encompass more activities than the ones listed above; however, it seems appropriate to include questions and observations about these activities in clinical examination procedures.

• Contributing psychosocial factors. Numerous psychosocial factors (‘yellow flags’) that hinder or enhance complete recovery to full function have been described over the past few decades (Kendall et al. 1997, Watson & Kendall 2000, Waddell 2004). Those hindering recovery have been described in an acronym ‘ABCDEFW’, which does not indicate a ranking in relative importance (Kendall et al. 1997). This list of yellow flags is quite extensive, but in relation to the physiotherapeutic treatment of movement disorders and pain the following psychosocial factors may be conclusive:

‘beliefs and expectations’ with regard to the causes of the problem, as well as the possible treatment options

‘beliefs and expectations’ with regard to the causes of the problem, as well as the possible treatment options

confidence in own capabilities to control pain and/or well-being

confidence in own capabilities to control pain and/or well-being

sense-of-control over own well-being

sense-of-control over own well-being

movement behaviour during daily life activities, when the pain occurs

movement behaviour during daily life activities, when the pain occurs

level of activities and participation

level of activities and participation

reactions of social environment (boss, spouse, colleagues, friends).

reactions of social environment (boss, spouse, colleagues, friends).

A detailed description of these contributing psychosocial factors can be found in Chapter 8.

The assessment of psychosocial risk factors and resources should be an integral part of the assessment of persons with low back pain as they are mostly expressions of normal human illness experiences and may have a considerable effect on short-term and long-term treatment outcomes. Contrary to some guidelines, they should be taken into consideration within the first encounter with the patient. Particularly a sense of helplessness needs to be addressed early in treatment. An individualized programme of self-management strategies, in which the patient experiences a sense of control over the pain and/or well-being, needs to be incorporated in the initial therapeutic sessions.

Treatment/advice to the patient

The Paris Task Force on Low Back Pain suggested that patients' complaints of NSLBP are categorized into four groups (Table 6.1) and should be differentiated into acute, sub-acute or chronic pain (Abenhaim et al. 2000). They recommend the following approach with regards to bed rest, activity and exercises:

• Acute phase of pain (lasting less than 7 days). Bed rest is contraindicated for the groups 1–3. For group 4, bed rest should only be authorized if the pain indicates it. If bed rest is authorized, it should be intermittent rather than continuous. After 3 days of bed rest the patient should be strongly encouraged to resume their activities.

• In sub-acute phases (lasting between 4 and 12 weeks) and in chronic phases, bed rest is not only contraindicated, but should be stopped in patients still resting in bed at this stage.

The task force did not recommend any exercises or functional restoration for the acute phases of NSLBP in the first 7 days, but for sub-acute and chronic phases they found sufficient scientific evidence to recommend patients to follow an active exercise programme.

However, the recommendations to the kind of exercises and movement approaches have been kept in general terms, such as strength training, stretching and fitness, in which no movement concept was found to be more superior to another.

Furthermore no distinction seems to be made if the acute pain is of a recurrent nature or occurring for the first time. Recurrences of acute NSLBP and disability need to be prevented (Burton et al. 2009) and the clinician should evaluate in which circumstances recurrences develop, in order to be able to define an adequate individualized (behavioural-) movement therapy programme aimed at the prevention of such episodes.

It is suggested that low back pain should be treated in the primary care setting, with a focus on a concept of reduced activity, rather than resting, recommending patients to stay as active as possible and to take NSAIDs if necessary for a period of 7–10 days, provided that no special ‘red flags’ indicative of more serious pathology are present (CSAG 1994). In addition, Waddell (2004) suggested examining a patient within 48 hours, treating patients with medication or manipulative therapy and, further, to follow the guidelines of the Clinical Standards Advisory Group (CSAG 1994). However, in a study with audiotaped interviews and questionnaires with 1-month follow-up, Turner et al. (1998) conclude that providers typically addressed medical issues, but did not (or only inconsistently) assess functional limitations related to pain and did not discuss how to resume normal activities, although this was a highly rated goal for most patients. Physicians often did not adequately reassure patients that serious conditions were ruled out, nor did they consistently address worries by the patient. In fact, at times patients felt more insecure about the (self-)management of their problem than before the consultation.

It appears that deliberate measures should be taken by the primary care clinician to provide the patient with a sense of control over the pain. This probably is best obtained within a single session with a specialist of movement rehabilitation and pain management, as for example a physiotherapist specialized in musculoskeletal (MSK) rehabilitation (manipulative physiotherapist).

Referral of patients with acute low back pain

If the pain and disability do not settle as quickly as desired, a second opinion in the primary care setting should be considered. This opinion could be provided by a family doctor with special interest and expertise in back pain or by a physiotherapist, chiropractor or osteopath (Waddell 2004).

If patients, in whom specific pathologies have been ruled out, do not improve and remain off work after 3–6 weeks, they should be referred to rehabilitation services, in which physiotherapy has a key role to play. However, rehabilitation is often only considered after medical treatment is complete or has failed (Waddell 2004). The restoration of movement functions appears to be considered an automatic process, in which patients are expected to resume their normal level of activities and assume their participatory roles in society on their own. Although quite a number of persons with back pain may do so, it is essential to recognize those individuals, who do not resume their normal levels of activity within the expected time of recuperation and to refer them to a physiotherapist.

Only if patients should be investigated and treated for specific pathology should they be referred to specialist services (CSAG 1994). However, Waddell (2004) argues that they should be referred with a clear and explicit goal in mind, being the exclusion of more serious problems, pain control or rehabilitation. The choice of specialist, the facilities they provide and the outcome measures should reflect these goals. As Waddell states: ‘there is no point referring a patient to a surgeon and judging success in surgical terms if what the patient really needs is rehabilitation’ (p. 444).

The Clinical Guidelines for the Management of Acute Low Back Pain (RCGP 1999) summarize the process of diagnostic triage and referral recommendations, as described in Box 6.1.

Scope of practice of physiotherapists regarding NSLBP

With the conceptualization of NSLBP, physiotherapists may need to (re-)consider their scope of practice, both in the emphasis of clinical work and in the development of subgroups of patient classifications needing different approaches of movement therapy.

Pillars of physiotherapy practice

It is essential that physiotherapists remain aware of the overall scope of their profession and the possibilities it offers in treating patients suffering from pain, and to not reduce their work to active exercises aimed at muscle strengthening, stretching or general fitness, just because many reviews have qualified studies of these aspects of human movement therapies as acceptable evidence.

In the UK the scope of practice of physiotherapists is defined by four pillars of practice and the fostering and development of such being massage, exercise and movement, electrotherapy and kindred methods of treatment (Chartered Society of Physiotherapy 2008). As stated in numerous places in this book, there is ample evidence for passive movement, therapeutic touch and physical applications being equivalent to active therapies, and in certain cases it even may be better to start with these treatment forms before embarking on an active movement programme. In relation to low back pain, evidence suggests that the following should be included in the current best practice for the management of NSLBP:

• Staying active and work productive

• Engaging in physical activity and exercise

• Being informed and educated about low back pain in a non-threatening way

• Simple analgesic and NSAID support

• Timely manipulation and acupuncture (NICE 2009).

All these recommendations (apart from prescribing, which is an extended scope practice) fall within the four pillars of practice.

Paradigms

Furthermore, it is important to note that every intervention aimed at anatomical structures or to enhance movement will also influence emotional or other aspects of a person.

In a discussion on paradigms, Coaz (1993) argues that physiotherapists may implicitly be working within a bio-psychosocial paradigm, although their explicit viewpoint may be a biomedical one. He states that the perspective of the average physiotherapist and especially of manual therapists is focused on bones, muscles, connective tissue and sometimes on circulatory problems in which emotional dimensions hardly reach the awareness of the physiotherapist. However, Coaz (1993) argues that physiotherapists:

… have an access to and influence emotional aspects, even when this does not reach the consciousness of the physiotherapist – and neither the consciousness of the patient. (p. 4)

It seems that since this statement numerous studies have dealt with the bio-psychosocial viewpoints on the physiotherapeutic work. However, it is possible, in spite of the increasing number of studies, that physiotherapists still work more implicitly than explicitly within a bio-psychosocial paradigm (Hengeveld 2001). When the bio-psychosocial effects are being reflected and conceptualized, they can be deliberately integrated in treatment rather than being an implicit, intuitive aspect. In fact, it is recommended that physiotherapists develop a phenomenological viewpoint to their work, in which they guide patients from individual illness experience and illness-behaviour towards an individual sense-of-health and health promoting behaviours with regards to movement functions and general well-being (Hengeveld 2001).

International Federation of Orthopaedic Manipulative Physiotherapists' competencies and scope of practice

Physiotherapists also need to be clear therefore about where their role in the management of low back pain begins and ends. Best practice management of low back pain demands that physiotherapists acquire, foster and develop a broad and deep knowledge and skills clinical framework supported by professional, analytical and reflective attributes (IFOMPT 2008).

The physiotherapists' scope of practice for low back pain should encompass the dimensions and competencies detailed by the International Federation of Orthopaedic Physical Therapists (IFOMPT 2008; see Box 6.2). This should be viewed within the specific context of manipulative and movement therapies related to neuromusculoskeletal low back pain.

Treatment objectives

In the development of treatment, the physiotherapist, in collaboration with the patient, should define short-term and long-term treatment goals, which ideally should lead to optimum movement functions, overall well-being and purposeful actions in daily life, in order to allow the patient to participate in their chosen activities of life (in their roles as spouse, family member, friend; in sports, leisure activities and work).

Sense of control: A core objective of treatment should be at all times to support patients to develop a sense of control over their pain, or, if this seemingly cannot be achieved easily, as in chronic pain, a sense-of well-being in spite of the pain. The process of developing a sense-of control, and with this working on the self-efficacy and internalizing of locus of control with regards to pain, may be well expressed in the following quote:

One of the main goals of the infant is to try to gain some control over his or her environment. The attempt to reduce uncertainty and establish control seems to be one of the most fundamental human drives. One of the key aspects of personality is the strength of this drive and the balance between our personal needs for control and the needs of others. These beliefs are probably not innate, but more likely a product of learning and social conditioning …] In rearing children every parent has to find the right balance between affection and nurturing on the one hand, and the imposition of control on the other.[…] Our self-confidence is related in part to the extent to which we have established sufficient control over our environments to meet our needs[…] As a result of this life experience, we all form beliefs about the extent to which we are able to get control of our lives […].

[…] Gaining control over back pain means actually mastering the pain and associated disability. The ability to do this is largely dependent upon the individual's own judgement of their capabilities.

Waddell 1998, p. 196

If patients learn self-management strategies, which they can apply easily in daily life, at initial stages of treatment, the confidence to take on activities that they might have believed to be harmful may be enhanced. Therefore self-management strategies play a central role in the secondary prevention of chronic disability due to low back pain. As this relates to changing movement behaviour, altering movement patterns and thought patterns regarding movement and pain, a cognitive behavioural approach to treatment is essential, in which every action such as communication, education, information and touch are applied in a reflected manner. In this context, Fordyce (1982, 1995) suggests focusing on the question why people develop certain kinds of behaviour, rather than primarily asking which nociceptive processes cause the behaviour. A cognitive behavioural attitude, in which it is acknowledged that behaviour does not change overnight, is important in this process. In the development of these self-management strategies, patients may go through different phases of change (Prochaska & DiClemente 1994) before a desired behaviour may be fully integrated in habitual daily life activities.

It is essential that the strategies are simple enough, that they can be applied or adapted directly to daily life situations and that the patient is guided towards a sense of success

Furthermore, to enhance compliance and a sense of success, it is often useful, to provide patients with the possibilities of (telephone) contact, if any queries or insecurities about the self-management strategies would come up, particularly in those cases of an acute phase of (nociceptive) NSLBP, in which a patient is only seen a single time (see also Chapter 8).

Physiotherapists with their specific professional expertise have numerous possibilities to guide patients towards a sense-of-control over their pain or well-being, as for example:

• Repeated movements, often in contrasting direction to the habitual movement patterns (McKenzie 1981)

• Automobilizations, stretching exercises

• Muscle recruitment exercises

• Pacing strategies in which active and relaxing cycles in daily life follow each other

• Body awareness, including the awareness of thoughts, emotions and behaviours on bodily reactions and pain

Optimizing movement capacity: Another important goal of treatment is the optimization of the movement capacity of a person. In order to motivate patients towards the normalization and optimization of movement functions and activity, a process of collaborative goal-setting is essential (see Chapter 3). Within this process it is important to recognize the possible barriers to the restoration of full function and to address them in treatment by implementing self-management strategies, educational interventions about neurophysiological pain mechanisms, the role of movement in pain or stress-physiology in an early phase of treatment. Furthermore, also in this phase of treatment, a cognitive-behavioural approach to physiotherapeutic treatment is essential to enhance continuous and profound changes with the patients concerned.

In order to provide a meaningful rehabilitation towards full activity, the subjective and examination procedures should be directed towards questions about restrictions and possibilities of activities and to the establishment of the conditions required to achieve optimum activity levels. The core sets of ICF (Box 6.3; WHO 2001) may be more comprehensive than the activities as outlined by the Paris Task Force on Low Back Pain (Abenhaim et al. 2000). They may aid in the definition of collaborative outcomes and the fostering and development of a public health framework within the physiotherapist's scope of practice.

Psychosocial aspects in treatment: As stated before, treatment will always have psychosocial effects, in one form or another. They may be a part of the implicit, intuitive process; however, there are clinical situations in which a deliberate multidimensional approach to treatment should be taken. In this approach, goals on cognitive, affective and behavioural levels should be defined explicitly next to objectives on the enhancement of movement behaviour and movement capacity. It seems that these factors are first considered when a pain problem has become chronic. However, it may be of use to consider these factors immediately in a first consultation of acute NSLBP, or when a patient is seen for a second session after approximately 7–10 days.

Vlaeyen & Crombez (1999) postulated that a pain experience may change over time. Within 2–4 weeks after an acute nociceptive situation cognitive and affective factors, for example anxiety, helplessness, different cognitions about causes of the problem, and treatment options for the pain, may become important contributing factors in the maintenance of pain, disability and distress. Therefore any concerns a person has because of the pain need to be addressed in the first consultation and creating a climate in which the patient feels they can ask questions or seek advice, even between treatment sessions, may become central in the process of secondary prevention of chronic pain.

It has been recognized that physiotherapists are aware of the need for a more multidimensional approach to treatment – at the latest in the fourth treatment session, once they notice that the patient's reduction of pain and improvement of activity levels have not improved as expected in the prognosis at the first consultation. In fact, discrepancies between pain, disability and the expected time of functional restoration with regard to physiological tissue regeneration appear to be core factors in the determination of a need for a more multidimensional approach to treatment (Hengeveld 2001).

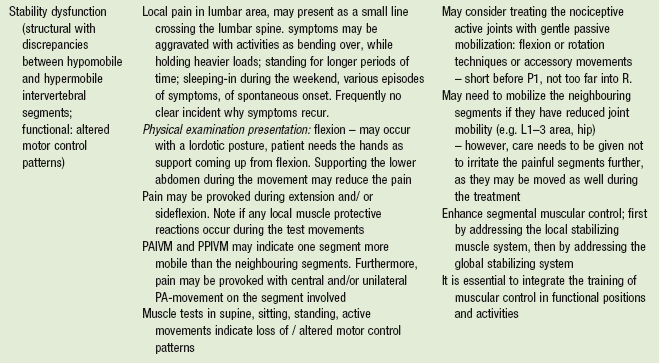

Phases of NSLBP and physiotherapeutic treatment: Maher et al. (1999) suggested physiotherapeutic treatment objectives, which are described in Table 6.2. However, it needs to be noted that defining sub-acute and chronic phases only based on the course of time may be problematic. It is important to know which kind of treatment the patient has received so far. Pain may be persisting because of interventions, which have not been thoroughly reassessed, hence they have not been perceived by the patient as being effective. Some patients may not have had any treatment at all for their problem. Also, generalized exercises, without specific self-management strategies to control pain, may be not effective enough. Furthermore, in some neurogenic pain states, severe pain may last much longer than a more simple nociceptive process. History taking, including exact information on the treatment so far, their immediate effects and a detailed analysis of the self-management strategies (which ones? when are they performed? can they be integrated in daily life? and what are the immediate effects on the pain/well-being?) should be the basis of every physiotherapeutic treatment programme, regardless of the phase in time of the symptoms and signs.

Table 6.2

Physiotherapeutic activities recommended for the different phases of NSLBP based on an extensive literature review (Maher et al.1999)

*Additional note from the authors of this chapter.

Classifications, subgroups and models: Current best evidence confirms the beneficial effects of movement in the treatment of NSLBP; however, several studies show that no active therapy seems more superior than another. It would be oversimplified to conclude that ‘it would not matter what is done’; it appears more likely that different treatment approaches, as for example motor control exercises and graded activity, have similar effects (Macedo et al. 2012). It seems that the quality of, and the therapeutic climate in which, the exercises are implemented is important and that better results are being observed in individualized, supervised exercise programmes (Hayden et al. 2005, O'Sullivan 2011).

In spite of results in favour of individualized, supervised exercises in which therapists may follow their personal preferences, numerous questions should be answered in studies in which a better subgrouping of patients out of the heterogeneous group of NSLBP is undertaken.

Questions that may need to be pursued deeper in systematic study with well-defined subgrouping of the included subjects are:

• Which kind of patients react better to individualized, supervised treatment in contrast to group treatment?

• Is it possible that patients with a clear motor deficit respond better to motor control programmes, while persons with higher fear avoidance behaviour and lower fitness levels may react better to a graded activity approach? (Macedo et al. 2012)

• Which group of patients reacts better to spinal manipulative therapy in combination with a certain kind of exercises, or which groups need an approach with repeated movement and which groups would respond more to general bodily awareness and relaxation?

• Which groups of patients may need to be considered more from a perspective of changes in the brain, based on cortical reorganization and degeneration rather than singled out in subgroups of bio-psychosocial diagnosis and treatment (Wand & O'Connell 2008). Additionally, with a more complex question into clinicians' attitudes and models: which groups would respond best to an approach in which clinicians apply treatments as usual, but from the perspective of supraspinal (re)learning and reorganization?

Primary research and evaluation of best practice informs physiotherapists about the meaningfulness of their manual examination and intervention methods for low back pain (O'Sullivan 2005, Kamper et al. 2010, Flynn et al. 2002, Smart et al. 2012, Schafer et al. 2011, Slater et al. 2012).Therefore, if treatment based sub-groups could be reliably identified, it would represent an important advance in low back pain treatment and the pursuit of this goal has been identified as a priority for low back pain researchers (Kamper et al. 2010).

The necessity to define subgroups for scientific inquiry and decision-making regarding treatment of low back pain has been increasingly acknowledged in the past two decades. However, Billis et al. (2007) described in a cross-country review in nine countries, that most studies were classified according to patho-anatomic and/or clinical features. Only a few studies utilized a psychosocial and bio-psychosocial approach. They concluded that no internationally established, effective, reliable and valid classification system is available, which incorporates the different subgroups for the definition of valid inclusion-criteria and statistical analysis. McCarthy et al. (2004), based on a literature review with 32 studies, suggest developing an integrated system, which allows for the assessment of NSLBP from biomedical, psychological and social constructs. This viewpoint is shared by Ford and Hahne (2012), who argue that researchers in low back pain need to incorporate both pathobiological and psychosocial perspectives, without emphasizing one model and neglecting the other. Furthermore, they recommend researchers to follow the clinical reasoning of clinician physiotherapists and to develop subgroups, which reflect daily clinical decision-making processes.

Also, various physiotherapists have suggested the development of subgroups based on movement-preferences of patients, with consequences for the selection of active movement therapies based on repeated movements (McKenzie 1981) and motor control exercises (Maluf et al. 2000).

In spite of missing international uniformity, numerous studies have been performed in which different subgroups have been established and which demonstrate the effectiveness of different physiotherapeutic approaches:

In particular, research has investigated sub-groups of patients who are more likely to respond to manual therapy or neural mobilization. The role of motor control strategies based on well developed knowledge have also been shown to influence back pain in many groups of patients (Hodges 2011, Dankaerts & O'Sullivan 2011, Hides et al. 2010, Macedo et al. 2009).

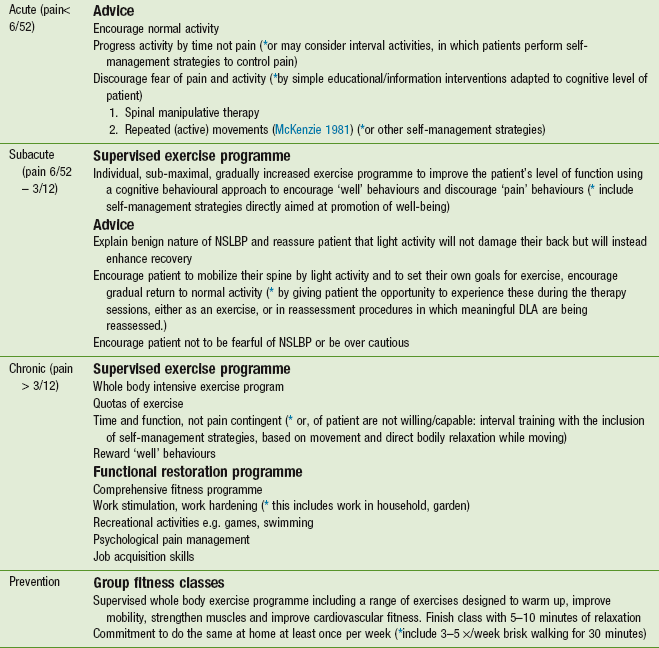

O'Sullivan (2005) has proposed a sub-classification of chronic NSLBP which identifies dysfunction at an impairment level. O'Sullivan is of the opinion that a range of models (Table 6.3), which identify the reasons for chronic low back pain, are needed within a bio-psychosocial framework; however, physiotherapists need to be aware of classifications which link directly to their domain of practice, that is, movement therapies.

Table 6.3

Models of low back pain classification

| Classification model | Clinical application |

| Patho-anatomical model | Conditions such as protruded intervertebral (IV) disc, spondlolysthesis, stenosis |

| Neurophysiological model | Cortical disorganization and the pain experience |

| (Bio)-psychosocial model | The impact of back pain on the individual and in society |

| Signs and symptoms model | Pain provoked by movement and motion testing |

| Mechanical loading model | Occupational/postural stresses and ergonomics |

| Motor control model | Failure in segmental and global motor control |

| Peripheral pain generator model | Pain generated by the IV disc, facet, sacroiliac joint |

| Disability model | Movement disorders: impairment, activity andparticipation levels |

Classifying chronic low back pain at an impairment level, O'Sullivan (2005) proposes that particular direction specific provocative spinal postures and movement patterns indicate the presence of either movement (restriction) or control impairments. The former being characteristic of restricted movement associated with fear avoidance, anxiety and both peripheral and central neurophysiological sensitization and responding well to manual techniques and active strategies which restore ideal movement and enhance movement conditioning. The latter being characterized by impairment of the motor system such that tissue strain in specific movement directions is not restricted but poorly controlled and responds well to motor control and muscle balance strategies to enhance pain relief and improved function.

In follow-up to these proposals, Dankaerts & O'Sullivan (2011) reviewed randomized control trials evaluating the validity of the motor control impairment sub-classification and note that it is good practice to utilize not only functional activation of the motor system but also cognitive-behaviour strategies to enhance motor control and reduce maladaptive movement.

Slater et al. (2012) carried out a systematic review to investigate the effectiveness of sub-group specific manual therapy for low back pain. Seven studies were identified for their methodological standard, although graded low in quality. The review suggested that there were significant treatment effects when heterogenous sub-groups were identified for intervention using manual therapy compared with pain treatments and activity.

Flynn (2002) provided the clinical prediction rule (CPR; Box 6.4) in the better quality studies (PEDro www.pedro.org.au/) and therefore the basis of the subgroup of patients with low back pain for which manual therapy provides a significant treatment effect.

Schafer et al. (2011) carried out an experimental design cohort study on sub-groups of patients with low back pain and leg pain to find out whether pain and disability outcomes differed between these sub-groups following neural mobilization techniques.

Seventy-seven recruited patients were sub-classified following interview and examination by experienced manual therapists. Patients' sub-groups were those classified as:

• Neuropathic sensitization (predominance of parasthesia and dysaesthesia with pin-prick hypo/hyperalgesia)

• Denervation (nerve conduction loss/ neurological deficit)

• Peripheral nerve sensitivity (nerve trunk mechanosensitivity with positive straight leg raise (SLR), PKB and positive nerve palpation)

All recruits received seven neural mobilization interventions twice per week that incorporated two passive mobilization techniques. The techniques were a foraminal opening technique (lateral flexion in sidelying), and a neural sliding technique (hip and knee flexion and extension in sidelying).

Outcome measures consisted of a numerical pain rating scale, the Roland Morris disability questionnaire and a global perceived changes scale from 1– ‘completely recovered’ to 7– ‘worse than ever’. Results indicate that patients classified as peripheral nerve sensitivity showed the best outcome scores and a more favourable prognosis.

This study suggests that it is important for physiotherapists to consider the type of presenting neural symptoms in order to apply specific neural mobilization techniques to the most appropriate subgroup of patient for best effect.

Smart et al. (2012), in a cross-sectional trial between subjects, investigated the discriminant validity of a mechanisms-based classification of patients with low back pain (with or without leg pain) by analyzing data on the self-reporting of pain, quality of life, disability and anxiety/depression.

One aim of the study was to improve clinical outcomes by using mechanism-based classifications to help physiotherapists apply appropriate clinical practice approaches. Using interview and examination, patients in the study (N=464) were classified into mechanism-based subgroups:

• Nociceptive pain (peripheral receptor terminal activity-tissue based)

• Peripheral neurogenic pain (lesions or dysfunction in peripheral nerves)

• Central sensitization pain (abberent processing and sensitivity within the central nervous system pain neuromatrix).

On analysis of the self-reporting in each subgroup it became clear that patients with nociceptive pain report less severe pain, have fewer quality of life and disability issues and suffer less anxiety and depression. In contrast, patient in the subclass central sensitization pain reported higher scores in each of the areas. Peripheral neurogenic pain classified patients reporting was in between the other two.

The suggestion here is that if physiotherapists can recognize patients in each of these mechanism subgroups they can be confident that, in general, patients with nociceptive pain will respond to tissue based interventions (manual therapy, active strategies) without cognitive behaviour barriers. Patients with peripheral neurogenic pain will respond to neural mobilization with some need to address cognitive behavioural issues. Whereas patient with central sensitization pain will need more interventions directed towards the maladaptive central nervous system processing (i.e. cognitive behavioural strategies) in conjunction with the application of tissue based approaches.

May & Aina (2012) investigated the centralization of symptoms and preference in movement directions in a literature review. It was found that the centralization phenomenon is more prevalent in acute than in sub-acute or chronic symptoms. They found 21 of 23 studies supporting the prognostic validity of centralization, including three high-quality studies. They conclude that findings of centralization or directional preference may be useful indicators of management strategies and prognosis in acute low back pain.

Kent & Kjaer (2012) investigated in a literature review if subgroups of people with particular psychosocial characteristics, such as fear avoidance, anxiety, catastrophizing, could be targeted with different treatment approaches. It appeared that graded activity plus treatment based classification aimed at people with high fear of movement was more effective in reducing this fear than treatment-based classification alone. Also, they describe that active rehabilitation with physical exercise classes based on cognitive behavioural principles was more effective than GP care at reducing activity limitations. However, they conclude that only few studies have investigated targeted psychosocial interventions. Overall they suggest more properly designed and adequately powered trials to find further responses to these queries.

It may be concluded that researchers in low back pain have recognized the necessity of subgroups in classifications for scientific studies. Many of these studies seem to reflect the clinical reasoning processes of physiotherapists, however currently it may be challenging to develop trials, which mirror the complexity of the clinical decision-making processes fully.

Clinical reasoning

The scope of the Maitland Concept, underpinned by open-minded clinical reasoning and patient-centred practice, is within the domain of rehabilitation. A classic example of this scope is evident from the following experience of one of the authors.

Whilst leading a course week on The Maitland Concept in a major European city with 20 students, a patient demonstration was arranged.

The patient, a 17-year-old male handball player, presented with low back pain and left-sided sciatica. He had hurt his back when he threw a ball in mid-air and landed awkwardly, twisting his back. He had had these symptoms for several months without resolution and he was only able to train for handball for half an hour before his symptoms became severe enough for him to have to stop.

He informed the group that he had a spondylolisthesis. His X-ray, in fact, showed a pars defect of congenital origin at L4. The group as a whole then began to think exclusively about the spondylolisthesis as the major factor in his problem and the focus of management.

Clinical examination, however, revealed a restriction in lumbar flexion, which became more so with cervical flexion as an addition but easier when deep abdominal muscles were activated. Lumbar extension was very restricted and reproduced his buttock and calf pain. When he jumped, as in handball, on initiation of the jump he lost control of his trunk lateral flexion. His SLR was restricted on the left and his L5 segment was stiff. He felt most comfortable lying on his right side.

Based on these findings and evidence he began to be able to control his symptoms and increase his exercise tolerance (1 hour training) over 4 days of functional interventions including:

• Restoration of pain-free SLR by the use of neural gliding techniques in right side lying with lumbar rotation and activation of deep abdominal muscles

• Mobilization of L5 whilst activating deep abdominal muscles

• Tonic control of the trunk in gradually loaded positions up to jumping and throwing.

The message here is that independent of pathological defects within the spine, which do not fully explain the onset and nature of the patient's symptoms, functional restoration and conditioning can and does have an effect on movement related symptoms, activity limitations and participation restrictions.

This example demonstrates the complexity of the clinical reasoning processes of physiotherapists, with the different paradigms and theoretical models, which they employ during assessment and treatment. With the ‘brick wall model’ of clinical reasoning, as developed by Maitland (1986), it is suggested that physiotherapists follow a different decision-making process from that of other professionals (e.g. medical practitioners), as the core of a physiotherapists' work lies in the analysis and treatment of movement functions. With the brick wall model Maitland moved away from the biomedical diagnosis as primary basis for decisions regarding the selection and application of physiotherapy treatments. Furthermore, he accentuated the necessity of independent decision-making processes in order to provide the best MSK-physiotherapy care (manipulative physiotherapy) possible. However, Maitland (1995) emphasized that manipulative physiotherapy should always occur under the umbrella of recognized health-care practice.

Physiotherapists often employ various forms of clinical reasoning, dependent on the particular needs of a situation. Most known is procedural clinical reasoning, with assessment and treatment procedures based on hypotheses generation and testing as well as on clinical pattern recognition (Jones 1995; for example, a physiotherapist examining a patient with sciatica and numbness in the big toe would include neurological examination and SLR as part of the assessment procedure). It has been recognized that therapists employ other forms of clinical reasoning as for example interactive, narrative, conditional or educational reasoning in addition to procedural reasoning strategies (Edwards 2000, Hengeveld 1998). As the subjective examination follows mostly a semi-structured interview, there is ample opportunity to integrate both procedural and interactive and narrative clinical reasoning, in which patients are enabled to give an account of their experience in sufficient depth.

Sound clinical reasoning is based on a profound and wide clinical knowledge base and cognitive and metacognitive abilities (Jones 1995). Also, theoretical knowledge from varied basic sciences is being applied to clinical situations: for example, the physiotherapist might think that a patient has nociceptive facet joint pain if the patient complains of deep unilateral aching stiffness in the lumbar spine when moving. This analysis is born out of knowledge of structure, mechanics and specific innervations of structures. Therefore, physiotherapists need a reflective and analytical approach to most, if not all, decisions they make in clinical practice and to develop an attitude of lifelong learning, in which they recognize their current specific learning needs.

Hypotheses generation and testing

At the moment a patient registers for treatment with a physiotherapist, the process of hypotheses generation will start, on the one hand by the physiotherapist, on the other hand by patients themselves.

Categorization of hypotheses support clinicians to distinguish relevant information from irrelevant information, to become aware of subtle expressions of the patient indicative of the individual illness experience with the illness-behaviour and to become more comprehensive when summarizing information from assessment procedures (Thomas-Edding 1987, Jensen et al. 1999). These hypotheses categories are described in Chapters 2 and 7.

Patients may focus on questions such as ‘what do I have’, ‘what can be done for it’, ‘how long will it take’. Their attitude towards treatment will be affected by their thoughts, emotions, belief-system, influences from their social environment and earlier experiences with therapy. For example, a patient may reveal that they are frightened of bending since they hurt their back because they don't want the same experience of pain again. They say ‘I do not want you to hurt me’. The analysis here is that the therapist must try to employ mobilization techniques in a way that also helps the patient to regain confidence in movement again. Explanation and inclusion in treatment decisions therefore become crucial. As these factors may be crucial in final treatment outcomes, they need to be considered by the therapist as contributing factors to the (movement) disorder or even determining factors in the individual illness experience of their clients. Therefore, physiotherapists should include hypotheses categories such as ‘contributing factors’ and ‘individual illness-experience’ in the reflection and planning of assessment, treatment and the therapeutic relationship.

Overall, the hypotheses and clinical decisions of physiotherapists may pivot around three main issues (Mattingly 1991):

1. What are possible causes and contributing factors to the patient's disorder? This relates to questions and tests regarding:

a. Possible pathobiological processes, including red flags

b. Analysis of causes of movement dysfunctions (movement behaviour)

c. Analysis of (movement-)impairments, activities, participation, contributing factors

d. Contribution of the individual illness-experience and behaviour, including yellow flags. E. e. Neurophysiological pain mechanisms

f. Physiological tissue-processes, as for example stages of tissue-healing.

2. Which treatment approaches may be most effective? This is associated with decisions on the current best evidence of therapies, but also with the question whether the current best evidence seems suitable to the patient as an individual. Therapists need to understand the role of passive and active movement, as well as other physical applications in treatment.

Possible habitually selected treatments based on the notion ‘I've always done it this way and it worked' need to be reflected upon; however, it is equally important to remain attentive of following injudiciously the favourite current treatment forms of a clinical and scientific cultural society. For any treatment chosen, clinical proof of its effects need to be given by consequent, comprehensive and well-reflected reassessment procedures (see Box 6.5).

3. How can patients be actively engaged in the therapeutic process?

There is increasing scientific support for the role of the therapeutic relationship in treatment outcomes and person-centred, multidimensional approaches with a cognitive behavioural perspective (Asenlöf et al. 2005, 2009). Also active engagement of a patient into treatment should support the process of patient-empowerment, as advocated by the World Health Organization (WHO 2008). Hall et al. (2010), in a review on the influence of the therapeutic relationship on treatment outcome, concluded that particularly beneficial effects could be found in treatment compliance, depressive symptoms, treatment satisfaction and physical function.

The question of active engaging patients in the therapeutic process is related to consideration of:

a. The roles of both therapist and patient in treatment (e.g. coach, educator, curative role, preventive role) (e.g. is the patient expecting something to be done to them or are they expecting the therapist to inform them on what they can do for themselves)

b. Expectations of the patients towards therapy (do they expect to be given manipulation or exercises for their back pain; also, do they have positive expectations towards the treatment)

c. Cognitive factors as belief systems about the causes and treatment options. Also the paradigms and perspectives patients have on their problem. If this differs from that of the physiotherapist, educational strategies at an early stage are necessary (e.g. the patient might think that moving and exercising will cause damage to their back whilst the therapist thinks that movement is necessary for recovery and reducing pain)

d. Affective factors, as for example gentle guidance towards more confidence in trusting to move (both in reassessment procedures as in explicit movement/exercise experiences)

e. Influence on, and by, the social environment. In this relationship at times the concept of secondary gain has been brought forward. Secondary gain is described as a social advantage attained by a person as a consequence of an illness; however, tertiary gains may also exist, in which others in the direct environment benefit from the illness of the person. It is warned not to focus solely on secondary gain of a person with pain without asking what may be the secondary losses to the person (Fishbain 1994). (Here the patient and therapist must have the same goals e.g. to return a patient with back pain to a working and productive life or, as in the case of chronic disability, to provide the patient the strategies to master their situation themselves.)

f. Behavioural factors, as for example movement behaviour, expression, guarding, confronting.

It is recommended that within a therapeutic relationship patients need to be treated as equals and experts in their own right, and that their reports on pain need to be believed and acted upon. Opportunities need to be provided to communicate, to talk with and listen to the patients about their problems, needs and experiences. In addition, independence in choosing personal treatment goals and interventions within a process of setting goals with, rather than for, a patient needs to be encouraged (Mead 2000). See also Chapter 3.

Experiential knowledge, clinical patterns

While reassessment-procedures primarily aim at monitoring clinical evidence of treatment-outcomes, they also fulfill an important role in the development of the experiential knowledge base of clinicians, as described by Schön (1983). It appears that experts may have more patterns in memory and may be capable of overseeing a situation quickly and are capable to find more comprehensive and effective solutions, faster than novices in a field (De Groot 1946). This is often an intuitive, implicit process. The concept of clinical patterns as a part of the experiential knowledge base has found acceptance in physiotherapy education and practice (Jones 1995). Studies between experts and novices demonstrated differences in ‘if … then …’ rules as a form of forward reasoning, being more present with experts. These rules may be considered as an expression of clinical pattern recognition and students need to be encouraged to express their ‘if … then … rules’ explicitly and to engage in consequent, written planning of assessment-procedures and treatment sessions (for example, an expert physiotherapist will have the experiential knowledge and professional knowledge to know quickly whether a patient with back pain will respond to manual therapy or will need cognitive approaches. In this way expert physiotherapists will reach a successful outcome quicker than the novice or move the patient on to self-management more quickly).

The development of clinical patterns cannot occur only by theoretical learning. Direct clinical experiences are necessary, in which clinical presentations and individual stories of patients are being encapsulated in clinical memory (Schmidt & Boshuyzen 1993). The application of theoretical knowledge, direct patient-contact, disciplined processes of hypotheses-generation and testing with consequent reassessment procedures and structured reflexion are prerequisites to the development of clinical patterns and expertise.

The following groups of clinical patterns may be distinguished:

• Movement disorders in conjunction with pathobiological processes. This is related to the question if, in the background of the movement disorder, pathobiological processes are present. Associated issues are:

How do they influence the short term and long term prognosis of the movement disorder?

In cases of NSLBP: are any movement patterns attributable to nociceptive processes in lumbar spine structures (e.g. disc, facet joint) or clinical syndromes (e.g. lumbar stenosis, neurogenic pain, lumbar structural/functional stability dysfunction), which need a specific approach to treatment?

• One-component versus multicomponent movement disorder. Movement disorders where it is more likely that one movement component is involved versus multiple movement components. One-component movement disorders may occur more frequently in younger people, with a single trauma in history (e.g. knee-distortion) with pain-reduction and improvement of activity levels occurring to the expected time of tissue-healing. Multicomponent movement disorders are more likely to occur where there is a degenerative, osteoarthritic background. In the latter case, screening of possible contributing areas to the nociception is important in the first three treatment sessions (e.g. pain in the buttock area often requires assessment of the lumbar spine, sacroiliac joint, hip, neurodynamic functions, possibly thoracic spine, and muscular functions).

• Approach to treatment: one-dimensional versus multidimensional approach. A movement disorder, which requires an explicit multidimensional approach to treatment. This means that contributing factors such as cognitive, affective, sociocultural and behavioural factors need to be explicitly defined in treatment-planning and in reassessment-procedures. In this case the quality of the therapeutic relationship, communication (interactive clinical reasoning), education and information may play a crucial role. This multidimensional approach is more likely to be required in chronic pain states or where recuperation of normal function and pain-reduction take much longer than normally expected. This is particularly necessary in those cases, where patients express a sense of helplessness, hopelessness or strong frustration with the provided health-care, with conflicting information; differ in beliefs / paradigms regarding causes and treatment; present avoidance-behaviour which has become maladaptive; perceive their state as highly disabling; demonstrate hypervigilant movement behaviour.

Prognosis and clinical prediction rules

Making a prognosis is an important skill in physiotherapy practice. However, often it is a daunting task (Maitland et al. 2005) as clinicians are more likely to be dealing with probabilities more than with certainties. Making a prognosis is a skill, in which clinicians match the clinical presentation of a patient's problem with theoretical knowledge (e.g. tissue healing) and clinical experiences made with patients who present with similar dysfunctions and resources. Hence, it contains elements of clinical pattern recognition. The years of experience which a clinician has spent with the assessment and treatment of particular disorders of persons will certainly aid in making a more accurate prognosis; however, experienced clinicians probably express themselves carefully while making a prognosis, as more stories may be encapsulated in their clinical memory in which patients' processes of recuperation differed from the initial prognosis made by the therapist.

Nevertheless, a clinician frequently needs to estimate in which way results may be achieved, how long treatment may take and which concrete results may be achieved. Patients often want to know, what is wrong with them, what can be done about it and how long it is going to take? Also, from the viewpoint of insurance companies and referring doctors, a physiotherapeutic prognosis may be essential.

Prognosis takes place in various phases:

1. At the beginning of a treatment series:

a. What can be achieved on a short-term basis: which results can be expected within the first three or four sessions (for example, the therapist might think, if the patient with acute low back pain improves by 80% within the first 3–4 sessions then there is a high probability that they will return to their normal duties)?

b. What can be achieved on a long-term basis during the overall process of physiotherapy?

2. During the treatment series, especially during retrospective assessment in every third or fourth session. It is essential to reflect on all the hypotheses formed and rejected thus far in the therapeutic process; especially the reflection on the prognosis may aid the clinician to learn profoundly from each encounter with a patient, and to develop and deepen clinical patterns in memory (for example, the therapist may find that the patients back pain is settling within 2–3 sessions of mobilization but their leg pain is not changing. The therapist may then think that the problem may take longer to sort out and other, additional treatment approaches may need to be considered).

3. At the end, during final analytical assessment – making a prognosis for the time after the therapy has been be completed:

a. The likely restraints on lifestyle.

b. The likelihood of recurrences of episodes of the disorder, and the possible early warning signs that the patient must heed in order to minimize the severity of the recurrence, and the steps the patient then needs to take.

c. The need for specific ongoing exercises, intermittent maintenance treatment, or follow-up assessment (for example, one patient with back pain may feel that they do not need any further advice where as another may be pain free and yet still fear that they will hurt their back again if they go back to work. In the second case it is important for therapy to include graded work hardening to ensure sustainable recovery and a favourable prognosis).

Specific hypothesis categories should also be considered to make a comprehensive prognosis:

1. Disorders that are easy or difficult to help (e.g. complex regional pain syndromes).

2. Nature of the person, including attitudes, beliefs, feelings, values, expectations, (movement) behaviour, and so on.

3. Nature of the disorder (intraarticular and periarticular disorders; mechanical osteoarthritis/inflammatory osteoarthritis; acute injury/chronic degenerative injury, nociception alone/nociception with peripheral neurogenic or central sensitization).

4. The body's capacity to inform and adapt. (The way the patient ‘feels’ about the disorder often correlates well with other aspects of prognosis. For example: ‘I've had back pain for 20 years so I know I'll never totally get rid of it, but I've been able to cope with it so far'.)

5. Contributing factors and other barriers to recovery (structural anomalies, systemic disease, general health problems such as diabetes, ergonomic/socioeconomic environments such as: keyboarding, heavy manual work; repetitive, monotonous activities; little control over work circumstances).

6. Expertise of the physiotherapist, especially in the field of communication and handling.

The bio-psychosocial model of the ICF (WHO 2001) may serve as an aid in considering aspects of a prognosis. If only function impairments are present – as, for example, slight restricted mobility of the hip and muscle imbalance in an otherwise healthy patient who is without great activity limitations, participation restriction and no relevant context factors – the prognosis will be, of course, much more favourable than if disturbances of all elements are present. The physiotherapist has to evaluate whether discrepancies among the elements of the model are present.

In prognosis-making, numerous factors need to be taken into consideration in either short-term or long-term prognosis:

• Stage of tissue healing and damage

• Mechanical versus inflammatory presentation of the disorder

• Irritability of the disorder

• Relationship between impairments, activity limitations and participation restrictions

• Onset of the disorder, duration of the history, stability of the disorder and progression/course of the disorder (are attacks more frequent or disabling?)

• Pre-existing disorders and dysfunctions (e.g. the patient has fallen on the shoulder; however, they may have had degenerative changes in the neck with some pain for some years)

• One- or multicomponent movement disorder (e.g. only local movement dysfunction in elbow, or the disorder has more components contributing to it: shoulder, cervical and thoracic spine, neurodynamic dysfunction)

• Contributing factors – ‘cause of the source’ (e.g. posture, muscle weakness or tightness, discrepancies in mobility of joint complexes, such as spine or wrist)

• Cognitive, affective, sociocultural aspects, learning processes: patient's beliefs, earlier experiences, expectation, personality, life style, learning behaviour, movement behaviour

• Multidimensional approach to treatment: consideration if the cognitive, affective and behavioural dimensions need to be addressed in treatment.

After some years of clinical experience, physiotherapists learn to recognize which kinds of clinical presentation react more or less favourably to treatment (Table 6.4).

Table 6.4

| Disorders easy to help | Disorders which may be more difficult to help |

| Strong relationship of patient's symptoms and movement | Weak relationship between the symptoms and movements in the patient's mind |

| Recognizable/typical syndrome or pathology | Atypical, unclear patterns, syndromes or pathology |

| Predominantly primary hyperalgesia and tissue-based pain mechanisms (nociception; peripheral neurogenic) | Predominantly secondary hyperalgesia from central nervous system sensitization rather than stimulus-response related tissue responses |

| Model of patient: helpful thoughts and behaviours (‘I can still do some things’; ‘I have found ways to get relief’) | Maladaptive thoughts and behaviour: (‘I don’t think I ever get better’; ‘I dare not move because always hurts me’) and other yellow flags |

| Familiar symptoms which the patient recognizes as tissue based (‘it feels like a bruise’) | Unfamiliar symptoms which the patient has difficulty describing in sensory terms |

| No or minimal barriers to recovery of predictors of chronicity (‘yellow flags’) | Multifactorial/multicomponent /complex regional pain syndromes |