Sustaining functional capacity and performance

Introduction

Physiotherapists play a central role in the maintenance and improvement of the movement capacity of individuals in a society. The overall objective of physiotherapeutic treatment may be summarized as follows: to enhance movement functions, overall wellbeing and purposeful actions in daily life, in order to allow a patient to participate in their chosen activities of life (in their roles as spouse, family member, friend; in sports, leisure activities and work).

Within the description of physiotherapy by the World Confederation of Physical Therapy (WCPT 1999) the core of the profession is described as follows:

• Human movement is central to the skills and knowledge of the physiotherapist

• These skills are particularly important in circumstances where movement and function are threatened by the process of ageing, or that of injury and disease

• Physiotherapy places full and functional movement at the heart of what it means to be healthy.

• Physiotherapists are concerned with identifying and maximizing movement potential, within the spheres of promotion, prevention, treatment and rehabilitation

• Intervention is implemented and modified in order to reach agreed goals and may include: manual handling; movement enhancement; physical, electrotherapeutic and mechanical agents; functional training; provisions of aids and appliances; patient-related instruction; documentation, coordination and communication

• Intervention may also be aimed at prevention of impairments, functional limitations, disability and injury including the promotion and maintenance of health, quality of life, and fitness for all ages and populations.

Within physiotherapy many treatment methods exist to achieve the above-mentioned aims. It has been discussed that many physiotherapists appear to identify with various treatment methods (KNGF 1992), without identifying with a central core of movement rehabilitation. This notion was formed a few decades ago; however, it still seems valid now, as other ‘new’ treatment methods appear to have become dominant and often exclusively applied. In spite of specializations within the field of physiotherapy, it is necessary for physiotherapists to develop skills in a wide range of treatment methods, including communication and patient education.

The following quote may demonstrate this principle:

Many of these approaches are practised to the exclusion of others. A manipulative physiotherapist may not take account of functional restoration. A Feldenkrais practitioner may not be concerned about fitness and functional restoration programmes may emphasize strength and stability at the expense of moving with ease. Self-management as the total solution can ignore the benefits of ‘hands-on’ therapy such as massage. Strength, mobility, fitness and relaxation all contribute to full functioning. Can practitioners afford to practise one method to the exclusion of others, or even worse, actively discourage others?

(McIndoe 1995, p. 156)

In the decades since the first development of the Maitland Concept of neuromusculoskeletal (manipulative) physiotherapy, many societal changes have occurred including immense changes in the lifestyles of many people. Furthermore, the viewpoints within medical and physiotherapeutic practice and science have changed from dualistic, biomedical to more holistic, bio-psychosocial paradigms.

Naturally these changes are also reflected in the workings of this concept; however, its core principles for the clinical work of physiotherapists are as valid as in its initial stages.

Lifestyle and physical activity

Lifestyles in the industrialized world have become more sedentary with different diets over the decennia since the Second World War. The impact of inactivity and diet on health issues is increasingly acknowledged and it has been recognized that regular physical activity is effective in the primary and secondary prevention of several diseases, for example cardiovascular disease, diabetes, some forms of cancer, hypertension, obesity, depression, osteoarthritis and osteoporosis. Furthermore, there is indication that musculoskeletal fitness is of particular importance in the elderly to maintain their independence (Warburton et al. 2006). It is estimated that each year 1.9 million people die as a result of physical inactivity, and that at least 30 minutes of moderate intensity physical activity 5 days per week reduces the risk of several of these common non-communicable diseases (WHO 2004). Global programmes to promote healthier lifestyles have been developed (WHO 2008) and it is acknowledged that the unique role of physiotherapists with their specific knowledge in sustaining movement capacity and health promotion will increase in these programmes in the near future (WCPT 2012).

Role of passive movement in promotion of active movement and physical activity

With the changing role of physiotherapists towards health promotion and prevention, as well as the focus on secondary prevention of ongoing disability due to pain, it may seem that passive movement as an element of treatment would become less relevant, or even obsolete. One of the listed psychosocial factors hindering full restoration of function is ‘overly depending on passive modalities’ and ‘excessive downtime because of the pain’ (Kendall et al. 1997). This has led to a somewhat polarized discussion of ‘hand-on’ versus ‘hands-off’ therapy by manipulative physiotherapists. In this debate it was assumed that passive modalities would make a patient dependent upon the treatment, and active movement would enhance active coping strategies. It seems that within this discussion no cognitive-behavioural perspectives on passive and active treatment modalities have been taken into consideration. Currently it appears sometimes that manipulative physiotherapists have to justify the selection of passive mobilization and manipulation in the treatment of their patients with painful movement disorders.

However, over the years an extensive body of randomized controlled trials (RCTs), reviews and practice guidelines report that in acute and sub-acute phases passive mobilizations and manipulations in combination with self-management strategies appear to lead to better treatment outcomes than single active or passive treatment-modalities (e.g. Gross et al. 2002, Jull et al. 2002, Vicenzino 2003, AAMPGG 2003, Van Tulder et al. 2006, Walker et al. 2008). In a recent editorial in the journal manual therapy it was commented that:

… Hands on, hands off? There is ample evidence of changes in motor control in association with neck and back pain. Thus there is no argument that exercise and activity are important components of any rehabilitation program to address these deficits. There is also ample evidence that zygapophysial joints and discs are common sources of pain. Manipulative/manual therapy is directed towards the painful joint dysfunction and there is a considerable body of research into the mechanisms of effect and effectiveness of manipulative therapy. Manipulative/manual therapy has proven pain relieving effects. […] the evidence suggests that the use of manipulative/manual therapy should not be forgotten. Painful joint dysfunction is present in the vast majority of neck and low back pain patients …

(Jull & Moore, 2012; p. 200)

Hence, also in contemporary perspectives, the art of passive mobilization and manipulation still plays a central role in the treatment of many movement disorders. Particularly in acute and sub-acute phases of nociceptive and peripheral neurogenic disorders to influence pain, passive mobilization and manipulation may give short-term effects on pain reduction. Furthermore passive mobilization techniques can be employed to optimize mobility of joints, neurodynamic structures, soft tissues and muscles. The discussion should revolve around the question of how active and passive treatment modalities can complement each other to achieve optimum treatment results, rather than a somewhat polarized selection of either one or the other treatment form. If passive mobilizations, and possibly also manipulations, are being applied within a cognitive behavioural approach to treatment, it is possible that better results are being achieved (Bunzli et al. 2011), both in the treatment of acute and sub-acute pain as well as in the treatment on ongoing pain and disability.

To summarize, with the application of passive mobilizations and/or manipulations within the overall physiotherapeutic management, the following aspects may need to be taken into consideration:

• Passive mobilizations serve as a kick-start to active movement.

• Passive movements also may play a role in the diagnostics of movement disorders, particularly within a framework of dominant peripheral nociceptive and neurogenic pain mechanisms. The abnormalities detected as for example pain-reproduction and restricted range of motion as well as the outcome in reassessment procedures after the application of the passive techniques, may be indicative of the source of the patient's symptoms.

However, in cases on central nervous system modulation with peripheral sensitization of tissue-reactions and more generalized tenderness false-positive results may occur. Nonetheless, in these circumstances hypotheses may be developed regarding reactivity and possible pathophysiological, cognitive, emotional and behavioural contributing factors to the pain experience. The reactivity to passive movement and touch, as well as generalized tenderness, may serve as a parameter in reassessment procedures.

Hence, touch and palpation also need to be seen as an important part of communication with the tissues and the understanding of responses of these tissues to touch and passive movement. On the one hand, touch and palpation allow the therapist to compare the state of the tissues encountered and, on the other hand, to be able to identify with the patient and gain an understanding of why and how protective responses have developed.

• In principle passive movement may find a place on the level of ‘body parts’ on Cott et al.'s (1995) movement continuum (see Chapter1 (and 2) of Volume 2). It is postulated that all levels on the movement continuum are interdependent. For example, painfully restricted hip movements may limit activities such as getting up from a chair, bending down or walking, adding to a lack of confidence in everyday activities and may become a contributing factor for loss of independence in elderly people. Therefore the optimization of the movement potential on this level of ‘body parts’ may be a central condition towards the restoration of full movement capacity. Based on information from subjective examination, the goals of rehabilitation of the movement levels of the person in the environment and society may be defined. However, the manipulative physiotherapist's specific physical examination procedures, including passive motion tests, will reveal if the conditions on the movement level of ‘body parts’ are being fulfilled and need to be defined in the treatment objectives.

• Passive mobilization may be necessary to optimize joint function in the so-called ‘functional corners’, e.g. shoulder-quadrant, extension abduction and extension adduction of the elbow or knee, or flexion/adduction (F/AD) of the hip (Maitland 1991). This will ensure that the joints have a functional reserve capacity when the movement system is asked to do a little more than it does normally. This functional reserve capacity may be a contributing factor in the reduction of the incidence of recurrent episodes.

• Frequently, treatment with passive mobilization and/or manipulation may be considered to achieve pain reduction on a short-term basis; however, in order to maintain long-term treatment effects, active movement to control pain and movement impairments, such as mobility and motor control, need to be integrated in an early phase of treatment.

• It appears that the integration of a cognitive behavioural approach to manipulative physiotherapy may enhance treatment outcomes (Bunzli et al. 2011). This includes addressing a patient's worries, assessing the patient's cognitions about causes of and treatment options for their problem, collaborative goal-setting, following a motivational phase of change model and compliance enhancement strategies, including education. Furthermore, being alert towards patients' key gestures or remarks during the various examination and treatment procedures and responding to them is important. For example, during palpation and the examination of accessory movements, a patient may say ‘that spot you’re pressing on is hurting me!’ Your explanation may need to be: ‘This spot especially needs treatment, not the ones that are fully painfree; however, I'm going to gently move this spot in such a way that it remains below the threshold of pain'. Or during reassessment procedures: ‘Why do you always make me perform movements which hurt me?’ In the latter case it may be useful to take a moment to explain the purpose of the reassessment procedures and the patient's observational role in them to compare the pain sensation and movement-ability.

• A multidimensional attitude towards touch as well as passive and active movement is needed. The following quotes demonstrate dimensions of therapeutic touch beyond joint mechanics and anatomy:

Through the skin every human being is subject to a multitude of impressions by which he perceives the objects with which he is in contact. Further he may have bodily sensations. Through these manifestations each individual assumes his corporeal identity and without this he could not define his immediate ‘life-world’.

(Rey 1995, p. 5)

Although manipulation starts at a local anatomical site, its remote influence on the human experience can be as far as the infinite expansion of the psyche. Manipulation is not limited by anatomical boundaries but involves the abstract world of the imagination, emotions, thoughts and full-life experience of the individual. The body is the centre of orientation in our perception of our environment, focus of subjective experience, field of reference, organ of expression and articulatory node between the self and the environment. When we touch the patient, we touch the whole of this experience

(Ledermann 1996, p. 158)

• It is postulated that active movement can occur without active (cognitive and emotional) participation of the patient, while passive movement, in combination with in-depth communication skills, can require strong participation of the patient, thus enhancing bodily awareness (Banks & Hengeveld 2010). During touching, passive movement and communication, the physiotherapist may mirror certain bodily reactions and guide the patient towards increased awareness of use of the body. This may be essential for many (chronic) pain patients, as they do not seem to have a sense of how they use (and tense) their body in many life situations. In fact touch (and passive movement) may be essential in many bodily-perception trainings. Furthermore, touch deprivation may be one essential aspect of chronic pain and suffering.

• Gentle passive movements, especially passive physiological movements, may guide patients to assist in active moving, followed by active movements (Zusman 1991). This approach may be particularly beneficial in those cases in which active movement does not seem to be possible.

• In those cases where touch and passive movement do not seem to be possible, active movement frequently is also difficult. A salutogenic approach towards active testing and passive movement may enhance selection of treatment interventions, including passive movement and touch (see Chapter 2).

• As manipulative physiotherapists frequently will select and apply other interventions beyond passive mobilizations to optimize the movement potential of the patient, it is essential to monitor the treatment outcomes of each intervention by regular re-assessment procedures.

• Summarizing the treatment effects in the reassessment phase after a passive mobilization technique is an essential feature of a cognitive behavioural attitude towards treatment, ‘since we moved your neck, it seems now that you move more freely, like you said. Now we should seek similar movements, which you can perform by yourself, so that you can keep control over the pain by yourself.’

If passive movements are used judiciously in combination with self-management strategies, patient education and communication, musculoskeletal (manipulative) physiotherapists have a lot to offer in the treatment of painful movement disorders and the secondary prevention of chronic disability due to pain.

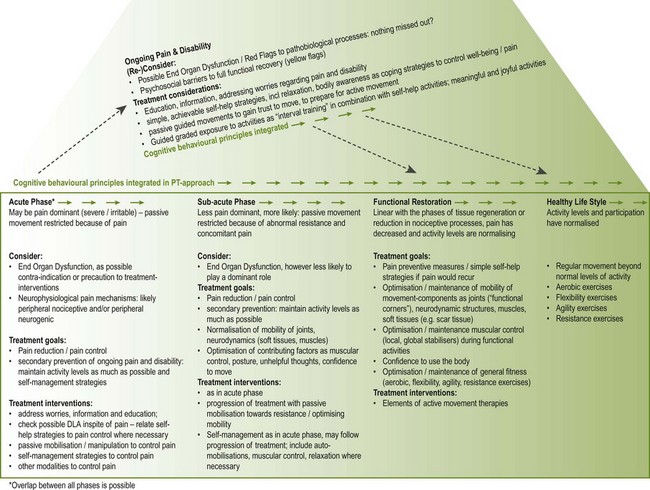

Figure 8.1 delineates the possible role of passive mobilization and/or manipulation within the overall physiotherapeutic process.

Figure 8.1 Therapeutic process: phases of functional restoration towards full movement capacity and the role of passive mobilization within this process. Some patients develop on-going pain and disability, which needs to be recognised in a phase as early as possible, in order to adapt the treatment to the specific needs of the patient.

Underlying mechanisms of passive movements

The underlying mechanisms of passive manipulative treatment have been described from different perspectives as biomechanics, tissue biology, neurophysiology and, partially, biochemistry. Early explanations included adjusting joint subluxations, restoring bony alignment and reducing nuclear protrusions. However it has been demonstrated that these theories have not found an acceptable scientific basis (Twomey 1992). Based on a literature review, it is postulated that the biological effects may be found in improvement of nutrition of spinal discs and vertebral joints, metabolic effects in synovia, subchondral bone and ligamentous and capsular structure, as well as fluid exchange between tissues (Twomey 1992). Neurophysiological effects, in particular, have received much attention in many publications (Wright 1995). In a study with 38 subjects with mild or moderate knee pain, passive accessory movements were compared with manual contact and no contact interventions. Pain pressure thresholds were described as increasing significantly in the mobilization group, locally in the knee, but also more distal from the affected joints (Moss et al. 2007). Similar results have been achieved in other studies on the spine (Vicenzino et al. 1998b, Sterling et al. 2001), elbow (Paungmali et al. 2003) and ankle (Yeo & Wright 2011). The authors postulated that local physiological, cellular mechanisms, such as alteration in concentration of inflammatory agents e.g. prostaglandin PGE2, as well as central nervous system mechanisms, could be involved in this phenomenon. The central mechanisms could include activation of local segmental inhibitory pathways in the spinal cord as well as descending inhibitory pathways from the brainstem (Moss et al. 2007). Sympathoexcitory effects have been described by various authors (Chiu & Wright 1996, Sterling et al. 2001), with effects on cardiorespiratory systems, as well as sudomotor and peripheral vasomotor changes (Vicenzino et al. 1998a). Based on a literature-review, Schmid et al. (2008) conclude that descending pathways may play a key role in manipulative physiotherapeutic induced hypoalgesia, with consistency for concurrent hypoalgesia, sympathetic nervous system excitation and changes in motor function. These notions are confirmed by Bialosky et al. (2008), who suggest a model in which a cascade of neurophysiological responses from the peripheral and central nervous system may be responsible for the therapeutic effects. Zusman (2004) proposes three neurological mechanisms as an explanation for the effects of manipulative physiotherapy:

1. Input by repeated stimuli, for example oscillatory passive movement and its progression, would lead to a desensitization of the nervous system with restoration of normal system sensory processing

2. Based on central learning theory and neuroplasticity, habituation of sensomotor processes, in which synaptic learning would lead to decreased behavioural responses to repeated stimulation; and

3. (Averse memory) extinction of protective, unfavourable sensomotoric patterns, by offering the nervous system different, normal sensomotor stimuli with passive and active movements.

Functional restoration programmes and self-management

With the development of functional restoration programmes to sustain optimum movement capacity of an individual, it is essential to consider the person's context, lifestyle, needs and preferences. Some like the challenges of medical training and fitness machines, whilst others prefer to run and do exercises in a forest rather than in a gymnasium. Others may favour exercising to gentle music and following movement programmes that enhance a sense of inner contemplation, rather than intense training accompanied by loud music. Furthermore, with regard to contextual aspects: a mother who has three young children, and who takes care of a sick father-in-law, may need simple relaxation techniques and exercises which can be adapted to her daily life, rather than a pre-set exercise programme which demands that she reserves extra time in her schedule.

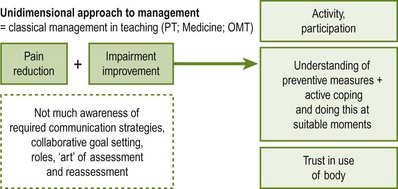

In a more traditional multidimensional approach to management, manipulative physiotherapists set the priorities of treatment firstly in reduction and control of the pain, in parallel with improvement of the movement-impairments. Often it is assumed that the patients themselves take the responsibility of rehabilitation on activity and participation levels: ‘Now that my shoulder is better, I have resumed training in volleyball. Also I spoke with the boss and I’ll start working again next week'. Furthermore, it is assumed that the patient immediately understands and applies preventive and self-management measures at appropriate moments, and regains confidence to move and use the body again (Fig. 8.2). If these situations indeed do occur, the manipulative physiotherapist does not need to consider many treatment objectives of functional restoration or motivation to change lifestyle. However, probably more often than not, therapists needs to ask themselves why patients do not resume their activities, or do not seem to apply the suggestions/exercises of the therapist, or why they do not appear to have confidence to use the body in daily life.

Figure 8.2 One-dimensional approach to treatment. Reproduced from Hengeveld (2000) with permission from Elsevier and Elly Hengeveld.

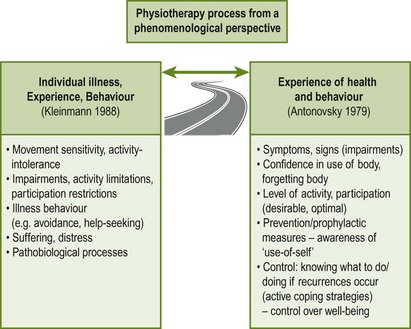

Usually the hypotheses regarding the movement dysfunctions and concomitant neurophysiological pain mechanisms, precautions to treatment and the individual illness experience with assessment and probationary treatments will have been established after the first two–three therapy sessions. In order to plan a comprehensive treatment ‘thinking from the end’ can be a useful tool to help plan further treatment in this phase (Fig. 8.3), by asking the following questions:

Figure 8.3 Manipulative physiotherapists guide patients on a disease-health continuum, towards a sense of health and well-being in movement functions. This approach guides physiotherapists in planning comprehensive treatment objectives. Reproduced from Hengeveld & Banks (2005) with permission from Elsevier.

• Which movement-impairments should be improved, if an ideal state could be achieved?

• Which activities must improve? Do any activities regarding participation need to be followed up?

• Is the general level of activity in daily life optimal, too low, or relatively high? If too low: how does one motivate the patient to increase levels of fitness and apply a fitness programme? If relatively high: are there any relaxation strategies that the patient may employ during daily life? Is there any disuse of structures by habituated movement patterns in daily life, which need to be addressed?

• Does the patient seem to trust the movement of his or her body in daily life? (If not: how can the manipulative physiotherapist guide the patient to the experience?)

• Does the patient move with an overly increased bodily awareness (and guarding) or seem to ‘forget’ the body during meaningful activities?

• Is the patient aware of any preventive measures and how to use his or her body in everyday situations?

• Does the patient seem to have an adequate sense of control of the pain or well-being? If not, which measures or specific coping strategies should be undertaken?

Purposes of functional restoration programmes

Functional restoration programmes may fulfil different purposes:

• Self-help strategies to control pain and to promote a sense of well-being

• Rehabilitation of movement impairments

• Prevention of new episodes of symptoms

• Increase bodily awareness and relaxation, including the change in habitual movement patterns

• Enhancing trust to move and to participate with confidence in daily life activities

• Increase general fitness and optimization of activity levels.

1. Self-help strategies to control pain and to promote a sense of well-being. These may include:

c. Relaxation strategies, including pendular exercises, visualization techniques, distraction

d. Body and proprioceptive awareness

f. Other pain management strategies, e.g. hot packs, cold packs.

The therapist first needs to establish the sources of nociception and movement dysfunction with the specific examination procedures of manipulative physiotherapy. Then the way in which the movement dysfunction should be treated needs to be determined collaboratively with the patient 1) by means of the therapist with passive movement and touch and 2) by self-management strategies of the patient, to maintain the gains from treatment. Exercises and other self-management strategies primarily need to be based on information of the subjective examination (24-hour behaviour of symptoms; history; contributing factors) rather than information from inspection and active testing alone. For example, a woman with a flat thoracic spine, who usually works in flexed positions may control her pain best by repeated movements in extension and/or rotation, in spite of the flattened thoracic spine.

2. Rehabilitation of movement impairments such as joint mobility, neurodynamics and muscle function, including automobilization exercises, neurodynamic ‘slider and tensioner’ techniques, muscle stretching/inhibition and muscular recruitment. The following aspects need to be taken into account:

a. Most of the exercises should maintain the gains from treatment with passive mobilization

b. The exercises need to reflect the current clinical stages of the patient's disorder, similarly to the selection and progression of treatment with passive movement

c. Particularly in peripheral joints, automobilizations can be similar to the passive mobilizations as performed by the therapist.

3. Prevention of new episodes of symptoms.

a. This may include recommendations from back-schools, muscular recruitment in everyday activities such as lifting things, increased awareness of body use (see above) and regular repetitive movements to compensate habitual patterns (e.g. repeated extension movements of the spine after sitting or pendular movements of the shoulder or knee after having been in an end-of-range position for a while).

b. Passive mobilization may be necessary to optimize joint function in the so-called ‘functional corners’, as for example shoulder-quadrant, extension abduction and extension adduction of the elbow or knee, or F/AD of the hip. This will ensure that the joints have a functional reserve capacity, when the movement system is asked to do a little more than it does normally. This functional reserve capacity will be a contributing factor to reduce the incidence of recurrent episodes, which is based on the following principle: ‘the more limited a movement is, the more vulnerable the structures will be if moved beyond their currents limits’.

4. Increase bodily awareness and relaxation, including the change in habitual movement patterns.

a. Within the change of habits in work movements and postures, training of awareness of the use of the body may be necessary. Many patients may not be aware of how they use their bodies with tension and guarded movements, which in itself may be a contributing factor to ongoing pain and hypersensitivity of structures.

b. Often, patients need to learn the pacing of daily life activities. They may perform certain activities for too long in the same manner. However, the education of pacing strategies needs to be considered from a cognitive behavioural perspective, as the physiotherapist enters the patient's world of personal values and meanings. It may not always be easy to change habits that have evolved over many years of a lifetime.

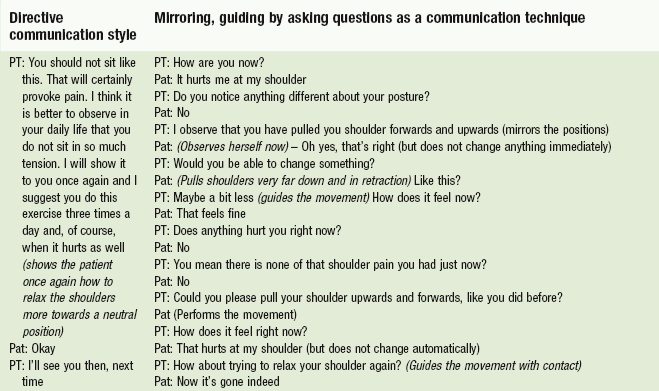

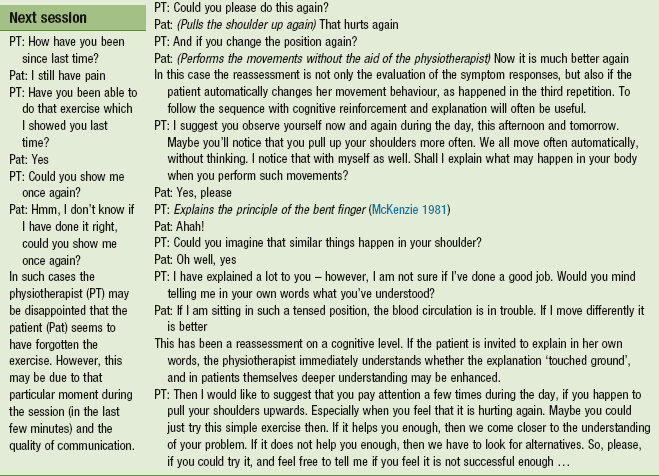

c. The therapist may guide the patient by gentle communication techniques and touch towards a different perception of the use of the body, e.g. a woman who habitually sits with her shoulder pulled into elevation and protraction and flexion of her thoracic spine (Table 8.1).

Table 8.1

Various communication styles leading to different responses and awareness

Reproduced from Banks and Hengeveld (2010) with permission from Elsevier.

5. Enhancing trust to move and to participate with confidence in daily life activities.

a. Frequently it is necessary for the manipulative physiotherapist to monitor whether the patient has regained trust to move in daily life situations. For example, is the patient confident to cross a street after a period of acute neck pain (requiring quick rotational movements)? Can the patient perform long periods of work that requires a lot of concentration (after an acceleration injury of the neck), or run to catch a bus after an episode of acute back pain? Frequently these automatic motor patterns have to be retrained, but it needs to be done in circumstances, which mirror the daily life situations as much as possible.

b. Another important element of moving with confidence is that a person normally is not aware of the body during meaningful activities. This ‘forgetting of the body’ is in a sense an aspect of a healthy experience. However, if symptoms should recur after a while, the patient ideally should integrate some of the recommended self-management strategies automatically.

c. Passive mobilizations may be a means to let patients experience movements again, which they did not dare to perform before. Again, passive mobilization may kickstart active movement.

6. Increase general fitness, optimization of activity levels and changes in lifestyle.

a. Many patients may need to increase their general physical fitness levels with physiological stimuli to improve cardiovascular condition, overall strength and agility.

b. Persons who have been avoiding activities may be physically deconditioned and may need reconditioning programmes with graded exposure to activity.

c. However, passive movement may be considered as a graded loading of structures and may become, in combination with well-guided reassessment procedures, a first step in the graded exposure to activities. In fact passive movement may be of support in the restoration of movement tolerance and acceptance, particularly in those cases where the patient has lost confidence in any active movement.

d. Furthermore, passive movement may ensure reserve capacity in mobility to maximize performance. This follows the same principle as stated above under the heading of prevention (optimizing mobility in ‘functional corners’ of, for example, the shoulder, hip, elbow, knee).

In planning functional restoration programmes, cognitive behavioural principles should be considered to enhance treatment outcomes.

Cognitive behavioural principles

As stated in Chapter 2 physiotherapists play an important role in changing patients' behaviour, particularly in relation to movement and functional capacity. It has been postulated that the integration of cognitive behavioural principles may enhance therapeutic outcome (Bunzli et al. 2011). It is essential to see these principles as an integral part of physiotherapy practice and not as a substitute.

It is recognized that behaviour and habits will not change overnight after a single instruction of an exercise. Part of the work of physiotherapists involves change management, in which motivation, increasing awareness and careful planning of all steps in the therapeutic process are essential. It is necessary to recognize that patients may go through different motivational phases, in which the recognition and guidance by the therapist may be crucial to final therapeutic outcomes.

The role of cognitive behavioural practice will apply in both the application of mobilization and manipulation, and more particularly in achieving the desired effect of maximizing functional capacity. This may encompass:

• Changes in movement behaviour in daily life – if pain or discomfort occurs, individuals learn to perform certain movements

• Changes in habitual patterns of movement in daily life, which may be a causative factor of pain

• Motivation to change behaviour with regard to training and maintaining fitness

• By means of information and educational strategies patients may develop a different perspective on their problem, for example, the meaning of pain as a threat may change; therefore, the patient is empowered to develop different coping strategies.

Next to skilled communication, the key cognitive behavioural aspects that may need to be integrated into physiotherapeutic approaches include:

• Recognition of potential barriers to full functional recovery

Recognition of potential barriers to full functional recovery

If individuals may not recuperate to full functional activities, it is recommended to take a bio-psychosocial perspective. On the one hand, it is essential to consider possible pathobiological processes (‘red flags’), which may have been missed out in the initial diagnostic process or psychosocial aspects, contributing to the pain and disability. It is important not to neglect the ‘bio’ viewpoint on patients' problems, even in the presence of psychosocial aspects (Box 8.1; Hancock et al. 2011).

On the other hand several potential psychosocial barriers to full functional recovery have been described and summarized in the term ‘yellow flags’ (Kendall et al. 1997, Watson & Kendall 2000, Waddell 2004). They have been described in a mnemonic ‘ABCDEFW’, which does not indicate a ranking in relative importance (Kendall et al. 1997). The yellow flags as they are related to physiotherapy practice are outlined in Box 8.2.

It is critical to avoiding pejorative labelling of patients with yellow flags as this will have a negative effect on the attitudes of clinicians and management of the patient's problem (Kendall et al. 1997). Predicting poor outcomes in acute nociceptive pain states with the presence of relevant yellow flags should lead to different approaches to treatment rather than denying therapy or shifting patients over to psychiatrists.

Within the physiotherapeutic process the most relevant yellow flags may be summarized as below (Hengeveld 2003). They need to be considered in clinical reasoning processes with the hypotheses categories ‘individual illness experience’ or ‘contributing factors’.

‘Perceived disability’

The perceived disability is an important element of the individual illness-experience. If this perception does not seem related to the phases of tissue regeneration or normalization of nociceptive processes, it needs to be specifically addressed in treatment, whether with educational strategies or direct experiences with activities which the patient feels may not be possible. However, this may need patience and careful planning by the therapist. A first impression of the perceived disability may be gained when at initial assessment the therapist asks about the patient's main problem and then completes the question with a more general question: ‘how does this problem interfere with your daily life: none at all, moderate or strong?’

‘Beliefs and expectations’

‘Beliefs and expectations’ can refer to the causes of the problem, as well to as the possible treatment options.

• Regarding causes and treatment option, the therapist needs to be aware that the patient may follow different paradigms from the therapist. If the patient has a more biomedical, structural oriented paradigm, while the physiotherapist follows a movement paradigm, confusion and insecurity may result if this is not clarified in the early phases of a treatment series. Therefore, time should be allocated in the ‘welcoming phase’ of treatment, to address the various approaches which may be possible and to emphasize the paradigms of the physiotherapist as a specialist for the diagnosis and treatment of movement dysfunctions. Some communication examples are given in Chapter 3, Communication and the therapeutic relationship.

• Over the course of treatment, if patients seem to relate their pain and disability strongly to an incident which lies many years back, it may be useful to invest time on educational strategies, in which it is gently clarified that the things which caused that start of the nociceptive processes may not be those aspects which maintain them. It is discussed that a pain experience often changes over time, due to interactions between the individual, his or her environment and medical professionals (Delvecchio Good et al. 1992), and due to an increasing influence of cognitive, emotional and behavioural factors (Vlaeyen & Crombez 1999).

• In addressing the coping strategies that the patient performs when the pain occurs, it is possible that patients perceive a sense of helplessness, by stating that ‘they cannot do anything to influence the pain’. In these cases it is essential to look for any instinctive postures or intuitive movements made by the patients. Very often these particular postures and movements may be integrated into therapy; for example, patients may state that they cannot do anything to help their pain while simultaneously placing their hands on their back and bending slightly away from the painful side. By making the patient aware that they already do something instinctively to help their pain, the therapist could suggest that this might even be a useful strategy if done deliberately, repeated and in a more relaxed way – and so, from the perspective of passive movements, the therapist may start treatment in combined flexion/sideflexion directions away from the painful side. Often patients may not be aware that they instinctively perform very useful strategies; the therapists' role may be to make the patient aware and to reinforce this behaviour by encouragement and subtle guidance.

Confidence in own capabilities

The topic of patients' confidence in their own capabilities to control pain and/or well-being is linked to beliefs and expectations, as discussed above.

If a patient shows little confidence and demonstrates strong protective movement behaviour or even a fear to move the performance of physical examination may be challenging, particularly if the physiotherapist emphasizes pain reproduction as the sole parameter to assessment. It has been acknowledged that a clinician's behaviour may reinforce the illness behaviour and experience of the patient (Hadler 1996, Pilowsky 1997). In such a situation it may be possible that careful guiding only until the onset of pain (‘P1’) and immediately away from the point of pain, in fact may reinforce the maladaptive or unhelpful behaviour. Test movements may be taken ‘slightly beyond the onset of pain’, rather than ‘until the onset of pain’. A point in the movement may occur where the patient indicates that the pain increases. The therapist then gently moves back in the movement to check if the pain subsides quickly enough, then progresses to the onset of pain again, at the same time enquiring if the patient has the trust to move a bit further. For example, if the patient is able to move until 90° of arm flexion before the pain starts, but stills trusts to move until 110°, the therapist has found two important variables in the test movement:

• ‘Trust 1’ at 110° of flexion, indicating the point in the movement at which the patient trusted to move to, in spite of the pain.

In fact, this approach to physical examination in cases of strong fear-avoidance behaviour may be considered as a first step toward guided graded-exposure-to-activity.

The communication example in Box 8.3 may explain some of the subtleties of the examination process in these circumstances.

Sense-of-control over well-being and movement behaviour when pain occurs

A patient's sense of control over their own well-being and movement behaviour when the pain occurs are both partially linked to beliefs and expectation, but also to direct behaviour.

The subjective examination phase, in which it is assessed when symptoms would increase, is particularly important for obtaining information about the sense of control and the behaviour leading to the increase in pain, as well as the behaviour used in controlling the pain or well-being. This phase of the examination may be an important learning stage for the patient, to link the activities to the onset of pain, as well as to the reduction of pain. Therefore, the potential of ‘patient-empowerment’ (Klaber Moffet & Richardson 1997) is very high at this initial stage of examination.

Opinions of other clinicians

If a patient has seen various clinicians, e.g. different medical specialists but also more than one physiotherapist, they may be left feeling insecure and confused from all the different opinions they may have received. In particular this may be the case if the patient's implicit expectation is that there is only one cure to the problem, and that the problem will be just normalized or removed. A possible remark indicating this could be, for example: ‘everybody says something different, why don’t they find it and fix it?’ It may be essential to take time and discuss with the patient the challenges and possibilities which may lie in all the different paradigms and viewpoints they may have encountered during their quest to relieve their pain. In fact, it may be necessary to address the issue of the numerous encounters explicitly, in order to gain the patient's trust:

Team members must, therefore, take great care with not only what they say, but also how they speak and behave. They should have the ability to put patients at their ease. Patients will disclose more information if they have confidence that clinicians are being honest and non-judgemental. Patients will have been seen by a number of other specialists. Usually these consultations have been very short, often not with a consultant, but with a trainee, whose communication skills may not be well developed. It may have been implied, that the pain is ‘all in the head’ or that patients are exaggerating their pain. The patient may even have been invited to see a psychiatrist.

The team member, therefore, generally has a considerable amount of repair work to do in order to gain the patient's confidence and impress upon the patient that this consultation will be different.

(Main & Spanswick, 2000; pp. 120 &121)

Level of activities and participation

The level of activities may be low and the patient may have been labelled as ‘physically deconditioned’ and suffering from ‘kinesiophobia’. Although reconditioning programmes towards a better physical condition will be necessary in many cases, it is important to realize that a term such as ‘kinesiophobia’ is somewhat awkward, as the behaviour leading to the avoidance of activities is in principle healthy, protective behaviour, which has become maladaptive over the course of time. A phobia is a psychiatric term described in DSM-IV (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4e; American Psychiatric Association 2000) and should stay in the realm of psychopathology. In fact, avoidance behaviour may be linked to aspects other than an avoidance to move, e.g. avoiding meaningful social activities such as accepting dinner invitations or going to the theatre (Philips & Jahanshani 1986, Philips 1987). Therefore this kind of behaviour may be considered to be a social avoidance of meaningful and joyful stimuli.

Reactions of social environment

It has been recognized for a long time that the social environment (e.g. spouse, boss, colleagues, friends) may have a direct influence on the behaviour and perception of a person with pain (Kleinmann 1988, Pilowsky 1997, Delvecchio Good et al. 1992, Kendall et al. 1997). Illness behaviour, with stress reactions or a sense of threat, may be reinforced by certain rewards, but also by punishing behaviour of the social environment. Constructs of ‘gain’ are likely placed under the umbrella of ‘reactions of the environment’. Secondary gain, which is claimed to play a role in the generation and maintenance of illness behaviour, may too readily lead to stigmatizing towards malingering (Fishbain 1994). Secondary gain is described as a social advantage attained by a person as a consequence of an illness; however, tertiary gains may also exist, in which others in the direct environment benefit from the illness of the person. It is warned not to focus solely on the secondary gain of a person with pain without asking what may be the secondary losses to the person as well (Fishbain 1994).

The process of collaborative goal-setting

The development of a therapeutic relationship is an essential element of a cognitive behavioural approach to treatment. It has been postulated that a constructive therapeutic relationship supports patients' satisfaction of treatment and aids in the development of trust (May 2001). It appears to enhance treatment outcomes (Foster et al. 2008, Bunzli et al. 2011). It is recommended that within a therapeutic relationship patients need to be treated as equals and experts in their own right. Within this practice following a process of collaborative goal-setting is recommended (Main & Spanswick 2000).

There are indications that compliance with the recommendations, instructions and exercises may increase if treatment objectives are defined in a collaborative rather than a directive way (Riolo 1995, Sluys et al. 1993, Bassett & Petrie 1997, Middleton 2004, McLean et al. 2010).

It is essential to consider collaborative goal-setting as a process throughout all treatment sessions rather than only at the beginning of the treatment series. In fact, ongoing information and goal-setting may be considered essential elements of the process of informed consent.

Various agreements between the physiotherapist and patient may be made in the process of collaborative goal-setting:

• Initially the physiotherapist and patient need to define treatment objectives collaboratively

• Additionally, the parameters to monitor treatment results may be defined in a collaborative way

• The physiotherapist and patient need to collaborate on the selection of interventions to achieve the desired outcomes

• In situations where ‘sensitive practice’ seems especially relevant, some patients may need to be given the choice of a male or a female physiotherapist or may express their preference regarding a more open or an enclosed treatment room (Schachter et al. 1999).

Frequently, physiotherapists may ask a patient at the end of the subjective examination what would be the goal of treatment. Often the response will be that the patient would like to have less pain and no further clarification of this objective takes place. In some cases this approach may be too superficial, especially if the prognosis is that diminution of pain intensity and frequency may not be easily achieved. This may be the case in certain chronic pain states or where secondary prevention of chronic disability seems necessary. Patients commonly state that their goal of treatment is ‘having less pain’; however, after being asked some clarifying questions it often transpires that they wish to find more control over their well-being with regard to pain, in order to be able to resume certain activities.

In the initial session during subjective examination, various stages occur in which collaborative goal-setting may take place by the communication technique of summarizing:

• After establishment of the main problem and the areas in which the patient may feel the symptoms

• After the establishment of the 24-hour behaviour of symptoms, activity levels and coping strategies

• After establishment of the history

• After completion of the physical examination (at this stage it is essential to establish treatment objectives collaboratively, not only in the reduction of pain, but also to define clear goals on the levels of activity which need to be improved and in which circumstances the patient may need self-management strategies to increase control over wellbeing and pain).

The relatively detailed process of collaborative goal-setting needs to be continued during the initial phase of each session. It is essential to clarify if the earlier agreed goals are still to be followed up. If possible, it is useful to explain to the patient the diverse treatment options on how the goals may be achieved and then let the patient make the choice of the interventions.

Another phase of collaborative goal-setting takes place in later stages during retrospective assessment procedures. In this phase a reconsideration of treatment objectives is often necessary. Initially the physiotherapist and patient may have agreed to work on improvement of pain, pain control with self-management strategies, educational strategies with regard to pain and movement, and to treat impairments of local functions, such as pain-free joint movement and muscular recruitment. In later stages it is essential to establish goals with regard to activities that are meaningful for the patient. If a patient is able to return to work after a certain period of sick leave, it is important to know about those activities which the patient seems most concerned about and where the patient expects to develop symptoms again. For example, an electrician who needs to kneel down in order to perform a task close to the floor may be afraid that in this case his back will start to hurt again. It may be necessary to include this activity in the training programme in combination with simple self-management strategies, which can be employed immediately in the work place.

This phase of retrospective assessment, including a prospective assessment with redefinition of treatment objectives on activity and participation levels, is considered to be one of the most important phases of the rehabilitation of patients with movement disorders (Maitland 1986).

To summarize, the process of collaborative goal-setting should include the following aspects (Brioschi 1998):

• The reason for referral to physiotherapy

• The patient's definition of the problem, including goals and expectations

• Clarification of questions with regard to setting, frequency and duration of treatment

• Hypotheses and summary of findings of the physiotherapist, and clarification of the possibilities and limitations of the physiotherapist, resulting in agreements, collaborative goal definitions, and a verbal, or sometimes written, treatment contract.

Phases of change

It has been suggested that individuals may go through various phases of motivation before they start to change behaviour (Box 8.4; Prochaska & DiClemente 1994, van der Burght & Verhulst 1997, Dijkstra 2002). Habits rarely change overnight and people will go through phases in which the intention may exist to change behaviour, but distractions and tasks in daily life, as well as other habits, may hinder the patient from automatically and consequently incorporating the suggested behaviour immediately. Physiotherapists have to be aware of these phases and adapt their instructions, recommendations and treatment accordingly.

It appears that explicitly recognizing and working with the phases of change may enhance compliance or adherence to suggestions and exercises more than other interventions, for example supporting materials. Based on a literature-review, McLean et al. (2010) concluded that there was moderate evidence that a motivational cognitive behavioural (CB) programme can improve attendance at exercise-based clinic sessions.

Compliance

Compliance is described as the degree to which the behaviour of a client coincides with the recommendations of the clinician (Schneiders et al. 1998). At times the word ‘adherence’ is used as well. However, both terms are somewhat awkward, as they indicate too strongly an authoritarian one-dimensional patient–clinician relationship in which the patient has to follow the orders of the clinician in a passive role (Kleinman 1997). Within this context a focus on the change of unfavourable (movement) behaviours in daily life is recommended, hence taking a cognitive–behavioural perspective in which the term ‘compliance’ is associated with a more active role for the patient.

Barriers to compliance

It seems that compliance to medical or physiotherapy interventions ranges from 15 to 94%, depending on the way the studies were performed (Sluys & Hermans 1990, Ferri et al. 1998). There appear to be different opinions as to why patients do not follow the advice, recommendations or exercises given by a physiotherapist. It appears that many physiotherapists contribute this to patients' lack of motivation or discipline (Kok & Bouter 1990).

However, a profound study indicates several categories of barriers perceived by patients to the suggested behaviours (Sluys 1991):

• Barriers to incorporating the suggestions and exercises into daily life (e.g. exercises in supine cannot be performed in a work setting; not enough time to exercise every day for 30 minutes; directive goal-setting such as ‘you should take more time off for yourself’; too many instructions and suggestions in one treatment session)

• Lack of positive feedback (insecurity as to whether the exercises are performed in the correct manner; no experience if the exercises truly are helpful)

• Sense of helplessness (the patient does not experience an ability to influence the situation positively).

Compliance enhancement

Various strategies may need to be employed to enhance the patient compliance to the physiotherapist's suggestions, recommendations and instructions. This may include motivational phases, short-term and long-term compliance:

Consider the various phases of changes through which a patient may go and adapt the treatment accordingly (see above).

Consider the various phases of changes through which a patient may go and adapt the treatment accordingly (see above).

Include patient education sessions on pain, neurophysiological pain mechanisms and the role of movement in tissue regeneration or modulation/neuroplastic changes of nociceptive processes.

Include patient education sessions on pain, neurophysiological pain mechanisms and the role of movement in tissue regeneration or modulation/neuroplastic changes of nociceptive processes.

The phase of short-term compliance starts once the patient begins to experiment with a few simple exercises in daily life.

The phase of short-term compliance starts once the patient begins to experiment with a few simple exercises in daily life.

The desired effect should not be expected immediately, nor should the patient be expected to perform the exercises at all the appropriate moments in his/her daily life.

The desired effect should not be expected immediately, nor should the patient be expected to perform the exercises at all the appropriate moments in his/her daily life.

Often it is better to start off with one or two exercises and to check whether they are helpful, before integrating others into the self-management pain control programme.

Often it is better to start off with one or two exercises and to check whether they are helpful, before integrating others into the self-management pain control programme.

Regular contact between the physiotherapist and patient is essential, in which the patient can ask questions and the physiotherapist can give corrections or suggestions.

Regular contact between the physiotherapist and patient is essential, in which the patient can ask questions and the physiotherapist can give corrections or suggestions.

The physiotherapist may need to motivate the patient to ‘hang on’ to the exercises, even if no immediate results are experienced yet.

The physiotherapist may need to motivate the patient to ‘hang on’ to the exercises, even if no immediate results are experienced yet.

During the subjective reassessment in follow-up sessions, the physiotherapist should find out whether the patient has been able to perform the exercises and if they have done them at appropriate times of the day. Patients may do the exercises at fixed times of the day; however, when pain increases they often stay in the habituated behaviour of resting or taking medication, rather than trying out the suggested interventions. It is essential that the physiotherapist does not consider this as a lack of motivation, but as a new help-seeking behaviour which has not been habituated yet. The style of communication may substantially influence this process of learning and experimenting with exercises in various daily life situations.

During the subjective reassessment in follow-up sessions, the physiotherapist should find out whether the patient has been able to perform the exercises and if they have done them at appropriate times of the day. Patients may do the exercises at fixed times of the day; however, when pain increases they often stay in the habituated behaviour of resting or taking medication, rather than trying out the suggested interventions. It is essential that the physiotherapist does not consider this as a lack of motivation, but as a new help-seeking behaviour which has not been habituated yet. The style of communication may substantially influence this process of learning and experimenting with exercises in various daily life situations.

The patient maintains the behaviour after completion of the therapy (long-term compliance).

The patient maintains the behaviour after completion of the therapy (long-term compliance).

This phase needs to be well prepared.

This phase needs to be well prepared.

It usually takes place towards the end of the treatment series and is completed with the final analytical assessment.

It usually takes place towards the end of the treatment series and is completed with the final analytical assessment.

Collaboratively with the physiotherapist, the patient needs to anticipate future situations in which pain recurrences are likely to occur.

Collaboratively with the physiotherapist, the patient needs to anticipate future situations in which pain recurrences are likely to occur.

The physiotherapist and patient discuss and repeat the behaviours which may be useful to influence the discomfort if the situation should occur.

The physiotherapist and patient discuss and repeat the behaviours which may be useful to influence the discomfort if the situation should occur.

Repetition of prophylactic measures is frequently helpful in this phase as well.

Repetition of prophylactic measures is frequently helpful in this phase as well.

Selection of meaningful exercises to enhance compliance: algorithm of actions and decisions

In order to find simple exercises which are meaningful to the patient, several decisions and actions may need to be taken:

• Find the sources of the movement dysfunction by examination and reassessment procedures.

• Make a decision collaboratively with, rather than for, the patient with regard to treatment goals and interventions.

• In the planning phase of treatment and the selection of interventions decide which physiotherapist-directed interventions (e.g. passive mobilizations) and which self-management strategies are to be employed.

• Consider the objectives of the strategies: does the patient need to perform the exercises for a limited period (e.g. postoperative treatment), or does the patient have to do the exercises for an indefinite period?

• For those patients whose main complaint is pain, it is essential to teach coping strategies that have an influence on the pain prior to the employment of interventions, which should influence contributing factors like posture and general fitness. With these coping strategies, patients may perceive a sense of success and control over their well-being; hence, they may develop the trust to perform exercises that they initially believed to be harmful.

Guidance towards a healthy lifestyle with increased activities needs education and the direct experience of a sense of control over the pain. Without effective coping strategies addressing pain and well-being, it may become an almost insurmountable task to develop an active lifestyle for persons suffering from pain and lack of confidence to move.

Compliance enhancement: general remarks

• One of the most essential goals of a self-management strategy is guiding patients to a sense-of-control over their wellbeing (Harding et al. 1998).

• Coping strategies for pain control should mainly be based on difficulties in daily life. In these cases, information from the subjective examination is frequently more important in decision-making than data from inspection or active movement testing (especially data from ‘24-hour behaviour’ and precipitating factors in history). For example, a woman who works at a sewing machine in a factory develops pain in the thoracic area after 6 hours of work. Although physical examination shows that she has a flattened thoracic kyphosis, her self-management strategies to alleviate the pain are variations of repeated extension and rotation movements.

• Exercises that need to be employed long-term should be integrated into normal routines (e.g. no exercises in supine lying). Provide simple, achievable exercises that can be easily incorporated into the daily life.

• Exercises need to contribute to a sense of success.

• It is essential not to teach a single intervention, but to work collaboratively with the patient on modifications of the exercise/instruction according to the demands of the various daily life situations. The patient needs to know that the adaptations are not different exercises, but ‘variations on the same theme’.

• Follow an instruction and education plan in which an awareness of all the instructions given during one session is necessary. Repeat the given information over various sessions; give pieces of information, rather than everything at once.

• Take time to teach the exercises, rather than telling the patient what to do in the last few minutes of a session. Allocate time for the patient to ask questions.

• If a patient believes that moving may be harmful when activities and work-situations provoke pain, the physiotherapist can guide the patient with educational strategies that are complementary to passive mobilizations and other self-management interventions. At times the physiotherapist may use the following axioms in the educational process:

• Written information as a mnemonic may enhance understanding. At times, patients may do this by themselves. A ‘pain, activities and exercise-diary’ may be incorporated.

• Ensure that the exercises can be implemented in daily life situations – therefore the patient frequently needs to be provided with variations of the same exercise (especially in those situations where the patient needs to develop a new behaviour, which needs to last for a long time, maybe even a lifetime).

• Anticipate difficulties: after the selection and instruction of an exercise, the physiotherapist needs to discuss with the patient whether and where he or she anticipates difficulties; certain exercises may be very useful but perhaps not during a given work situation. Collaborative problem-solving for such a situation is essential and modifications of the exercise need to be worked out.

• At the completion of a treatment series, in order to enhance long-term compliance, further anticipation of possible future recurrences and their solutions needs to take place.

Conclusion: compliance enhancement

Before instructing an exercise the physiotherapist may go through the following steps and questions:

• What are the goals of the exercise?

• When should the exercises be employed in daily life?

• Have I explained the objectives of the exercises to the patient?

• Have I checked if the patient has understood?

• Were the exercises reassessed immediately after the exercise? Did they contribute to a sense-of-success?

• Did I anticipate collaboratively with the patient whether and when difficulties may occur in performing the exercises?

• Which solutions have I worked out collaboratively with the patient?

Patient education

In order to promote motivation and enhance motivation of the patient, education has found an important place in physiotherapy practice (Sluys 2000, Butler & Moseley 2003). Patient education is considered a core task in physiotherapy practice, as the definition of physiotherapy by the World Confederation of Physical Therapy (WCPT 1999) states:

Intervention/treatment is implemented and modified in order to reach agreed goals and may include manual handling; movement enhancement; physical, electro-therapeutic and mechanical agents; functional training; provision of assistive technologies; patient related instruction and counselling; documentation and co-ordination, and communication.

Some educational principles

It has been recognized that in physiotherapy much information is given; however, it does not seem to follow explicit principles of cognitive-behavioural therapy, information technology or education (Sluys & Hermans 1990). It seems that many therapists do employ the principles, but in a more implicit, intuitive sense (Hengeveld 2000, Green et al. 2008, Sandborgh et al. 2010). Before embarking on an educational session, it is important to consider several educational principles (Brioschi 2005):

• What is the objective of the educational session(s)? For example, explain pain and the role of movement/activity in the management of pain; the role of movement and relaxation in the maintenance of health; the role of active movement in the regeneration of disc or cartilage tissue.

• Establish the cognitive level of the patient – at what complexity the education should be delivered?

• Develop an educational strategy – the information may be given (and reassessed) piecemeal over further sessions; a progression of information may enhance the educational process.

• Develop simple metaphors to explain aspects of pain and its treatment from the physiotherapist's perspective.

• Prepare educational material to support the educational process.

• Consider ways to reassess the process, e.g. by asking patients to repeat in their own words what they remember from the session.

• Ask yourself: does the given information contribute to more understanding or to more confusion in the patient?

• Give the patient time to ask questions; also in follow-up sessions.

In addition, the choice of words should be selected in such a way that the patient is directly integrated in the discussion, i.e. talking with rather than to the patient. It is pertinent to note that patients may be motivated faster, and on a long-term basis, if they hear themselves making statements about their options and possibilities.

A language that enhances change should revolve around five aspects:

1. Wishes (‘I would like to be able to play with my kids again’)

2. Reasons (‘I come to the physiotherapy because I want to learn what I could do myself’)

3. Possibilities (‘I could go swimming more regularly’)

4. Confidence (‘Going on my bike to work is something I could try, as I have done that before’)

5. Necessity (‘If I don’t do anything, I think my back will only get worse’)

If a person is changing in motivation, they may use language indicating commitment to the change. Clinicians should develop sensitivity towards these subtleties of language. Patients may state, for example (van Merendonk et al. 2012):

• I will do it when I have time

• I'll do my best to plan it into my schedule

It is stated that patient education is of particular relevance when the clinical presentation is characterized and dominated by central nervous system modulation of a pain experience and/or where maladaptive illness perceptions and behaviour is present (Nijs et al. 2011). However, it may be argued that each person, regardless of the clinical problem, needs adequate information in order to understand the physiotherapist's reasoning in the determination of a meaningful, individualized therapy.

Conclusion

Musculoskeletal (manipulative) physiotherapists have a core task in the treatment of patients with movement disorders and the guidance towards functional restoration and a healthy lifestyle. At certain times in the process the art of passive movement should not be neglected, and the incorporation of cognitive behavioural principles should be considered throughout all phases of the process. In order to provide optimum patient care, these elements deserve their justified place in contemporary practice as much as any other information gained from contemporary evidence-based practice.

References

AAMPGG (Australian Acute Musculoskeletal Pain Guidelines Group). Evidence-based management of acute musculoskeletal pain. Bowen Hills: Australian Academic Press; 2003.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, ed 4. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

Banks, K, Hengeveld, E. Maitland's Clinical Companion: an essential guide for students. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2010.

Bassett, SF, Petrie, KJ. The effect of treatment goals on patient compliance with physiotherapy exercise programmes. Physiother Can. 1997;85:130–137.

Bialosky, JE, Bishop, MD, Price, DD, et al. The mechanisms of manual therapy in the treatment of musculoskeletal pain. A comprehensive model. Man Ther. 2008;13(1):1–8.

Boissonnault, W. Primary care for the physical therapist. Examination and triage, ed 2. St. Louis: Elsevier – Saunders; 2010.

Brioschi R: Kurs: die therapeutische Beziehung. Leitung: Brioschi R & Hengeveld E. Fortbildungszentrum Zurzach, Mai 1998.

Brioschi, R. Course on interdisciplinary pain management – ZST. Switzerland: Zurzach; 2005.

Bunzli, S, Gillham, D, Esterman, A. Physiotherapy-provided operant conditioning in the management of low back pain disability: a systematic review. Physiother Res Int. 2011;16(2011):4–19.

Butler, DS, Moseley, GL. Explain pain. Adelaide, Australia: Noigroup Publications; 2003.

Chiu, TW, Wright, A. To compare the effects of different rates of application of a cervical mobilisation technique on the sympathetic outflow to the upper limb in normal subjects. Man Ther. 1996;1(4):198–203.

Cott, CA, Finch, E, Gasner, D, et al. The movement continuum theory for physiotherapy. Physiother Can. 1995;47:87–95.

Courneya, KS, Friedenreich, CM, Sela, RA, et al. Exercise motivation and adherence in cancer survivors after participation in a randomized controlled trial: an attribution theory perspective. Int J Behav Med. 2004;11(1):8–17.

Delvecchio Good, MJ, Brodwin, PE, Good, B, et al. Pain as human experience. An anthropological perspective. Berkeley: University of California Press; 1992.

Dijkstra, A. Het veranderingsfasenmodel als leidraad bij het motiveren tot en begeleiding van gedragsverandering bij patienten. Ned Tijdschr Fysio. 2002;112:62–68.

Ferri, M, Brooks, D, Goldstein, RS. Compliance with treatment – an ongoing concern. Physiother Can. 1998;50:286–290.

Fishbain, DA. Secondary gain concept. Definition of problems and its abuse in medical practice. Am Pain Soc J. 1994;3:264–273.

Foster, NA, Bishop, A, Thomas, E, et al. Illness perceptions of low back pain patients in primary care: what are they, do they change and are they associated with outcome? Pain. 2008;136:177–187.

Goodman, CBC, Snyder, TEK. Differential diagnosis for physical therapist: screening for referral, ed 5. St. Louis: Elsevier-Saunders; 2012.

Green, A, Jackson, DA, Klaber Moffet, JA. An observational study of physiotherapists’ use of cognitive behavioural principles in the management of patients with back pain and neck pain. Physiotherapy. 2008;94:306–313.

Gross, AM, Kay, TM, Kennedy, C, et al. Clinical practice guideline on the use of manipulation or mobilization in the treatment of adults with mechanical neck disorders. Man Ther. 2002;7(4):193–205.

Hadler, NM. If you have to prove you are ill, you can't get well. Spine. 1996;20:2397–2400.

Hancock, MJ, Maher, CG, Laslett, M, et al. Discussion paper: what happened to the ‘bio’ in the bio-psycho-social model of low back pain? Eur Spine J. 2011;20:2105–2110.

Harding, VR, Simmonds, MJ, Watson, PJ. Physical therapy for chronic pain. Pain, Clin Updates (IASP). 1998;VI:1–4.

Hengeveld, E. Psychosocial issues in physiotherapy: manual therapists’ perspectives and observations. London: Department of Health Sciences, University of East London; 2000.

Hengeveld, E. Das biopsychosoziale Modell. In: van den Berg F, ed. Angewandte Physiologie, Band 4: Schmerzen verstehen und beeinflussen. Stuttgart: Thieme Verlag, 2003.

Hengeveld, E, Banks, K. ed 4. Maitland's Peripheral manipulation: management of neuromusculoskeletal disorders. Edinburgh:Butterworth Heinemann Elsevier; 2005;vol 2.

Jull, G, Trott, P, Potter, H, et al. A randomized controlled trial of exercise and manipulative therapy for cervicogenic headache. Spine. 2002;27(17):1835–1843.

Jull, G, Moore, A. Editorial: Hands on, hands off? The swings in musculoskeletal physiotherapy practice. Man Ther. 2012;17:199–200.

Kendall, NAS, Linton, SJ, Main, CJ, et al. Guide to assessing psychosocial yellow flags in acute low back pain: risk factors for long-term disability and work loss. Wellington, New Zealand: Accident Rehabilitation and Compensation Insurance Corporation of New Zealand and the National Health Committee; 1997.

Klaber Moffet, J, Richardson, PH. The influence of the physiotherapist-patient relationship on pain and disability. Physiother Theory and Pract. 1997;13:89–96.

Kleinmann, A. The illness narratives: suffering, healing and the human condition. New York: Basic Books Harpers; 1988.

Kleinman, A. The spirit catches you and you fall down: a Hmong child, her American doctors and the collision of two cultures. In: Fadiman A, ed. The spirit catches you and you fall down: a Hmong child, her American doctors and the collision of two cultures. New York: Farrar, Strauss and Giroux, 1997.

KNGF. Visie op Fysiotherapie. Amersfoort: Koninklijk Nederlands Genootschap voor Fysiotherapie; 1992.

Kok, J, Bouter, L. Patientenvoorlichting door fysiotherapeuten in de eerste lijn. Ned Tijdschr Fysio. 1990;100:59–63.

Ledermann, E. Fundamentals of manual therapy: physiology, neurology and psychology. New York: Churchill-Livingstone; 1996.

Main, CJ, Spanswick, CS. Pain management: an interdisciplinary approach. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 2000.

Maitland, GD. Vertebral manipulation, ed 5. Oxford: Butterworth Heinemann Elsevier; 1986.

Maitland, GD. Peripheral manipulation, ed 3. Oxford: Butterworth Heinemann; 1991.

May, S. Patient satisfaction with management of back pain. Part 1: What is satisfaction? Review of satisfaction with medical management; Part 2: An explorative, qualitative study into patients’ satisfaction with physiotherapy. Physiotherapy. 2001;87:4–20.

McIndoe, R. Moving out of pain: hands-on or hands-off. In: Shacklock M, ed. Moving in on pain. Melbourne: Butterworth Heinemann, 1995.

McKenzie, RA. The lumbar spine: mechanical diagnosis and therapy. Waikanae, New Zealand: Spinal Publications; 1981.

McLean, SM, Burton, L, Littlewood, C. Interventions for enhancing adherence with physiotherapy. Man Ther. 2010;15:514–521.

Middleton, A. Chronic low back pain: patient compliance with physiotherapy advice and exercise, perceived barriers and motivation. Phys Ther Rev. 2004;9:153–160.

Moss, P, Sluka, K, Wright, A. The initial effects of knee joint mobilisation on oateoarthritic hyperalgesia. Man Ther. 2007;12:109–118.

Nijs, J, van Wilgen, CP, van Oosterwijck, J, et al. How to explain central sensitization to patients with ‘unexplained’ chronic musculoskeletal pain: practice guidelines. Man Ther. 2011;16:413–418.

Paungmali, A, O'Leary, S, Souvlis, T, et al. Hypoalgesic and sympathoexcitatory effects of mobilisation with movement for lateral epicondylalgia. Phys Ther. 2003;83:374–383.

Philips, HC. Avoidance-behaviour and its role in sustaining chronic pain. Behav Res Ther. 1987;25:273–279.

Philips, HC, Jahanshani, M. The components of pain behaviour Report. Behav Res Ther. 1986;24:117–124.

Pilowsky, I. Abnormal illness behaviour. Chichester: John Wiley; 1997.

Prochaska, J, DiClemente, C. Stages of change and decisional balance for twelve problem behaviours. Health Psychol. 1994;13:39–46.

Refshauge, K, Gass, E. Musculoskeletal physiotherapy. Oxford: Butterworth Heinemann; 1995.

Rey, R. The history of pain. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1995.

Riolo, L. Commentary. Phys Ther. 1995;73:784–786.

Sahrmann, S, Course on the assessment and treatment of movement impairments. 1999.

Sandborgh, M, Asenlof, P, Lindberg, P, et al. Implementing behavioural medicine in physiotherapy treatment. Part II: Adherence to treatment protocol. Adv Physiother. 2010;12:13–23.

Schachter, CL, Stalker, CA, Teram, E. Towards sensitive practice: issues for physical therapists working with survivors of childhood abuse. Phys Ther. 1999;79:248–261.

Schmid, A, Brunner, F, Wright, A, et al. Paradigm shift in manual therapy? Evidence for a central nervous system component in the response to passive cervical joint mobilisation. Man Ther. 2008;13:387–396.

Schneiders, A, Zusman, M, Singer, KP. Exercise therapy compliance in acute low back pain patients. Man Ther. 1998;3:147–152.