Evidence about patients' experiences and concerns

After reading this chapter, you should be able to:

• Appreciate the role of qualitative research in providing information about patients' experiences and concerns

• Describe the basic assumptions that underpin the common qualitative research methodologies of phenomenology, grounded theory, ethnography, action research, feminist research, and discourse analysis

• Develop a qualitative clinical question

• Have a basic understanding of how to search for qualitative research

• Critically appraise qualitative research articles

• Have a basic understanding of how to interpret the findings of qualitative research articles

• Discuss how the findings of qualitative research may be used in practice

This chapter focuses on questions that relate to the experiences of patients and health professionals and the meaning that patients and health professionals associate with these experiences. In general terms, evidence-based health care has tended to focus on the search for objective evidence to establish the degree to which a particular intervention or activity results in defined outcomes. The importance of basing practice on the best available evidence is now well accepted, and ways of finding, appraising and applying evidence related to diagnosis, prognosis, the effects of an intervention and experiences and perceptions from those involved in health care are becoming increasingly well understood. Thus, evidence-based practice is generally conceptualised as searching for, appraising and synthesising the results of high quality research and transferring the findings to practice and policy domains to improve health outcomes.

Health professionals seek evidence to substantiate the worth of a very wide range of activities and interventions, and thus the type of evidence needed depends on the nature of the activity and its purpose. Pearson and colleagues1 have described a model of evidence-based health care in which they assert that, if evidence is needed to address the multiple questions, concerns or interests of health professionals or the users of health services, it must come from a wide range of research traditions. Evidence that arises out of qualitative inquiry is frequently sought and utilised in clinical practice.2 Qualitative research seeks to make sense of phenomena in terms of the meanings that people bring to them.3 Evidence from qualitative studies that explore the experience of patients and health professionals has an important role in ensuring that the particularities associated with individual patients, families and communities are just as important as information that arises out of quantitative research.

Qualitative researchers attempt to increase our understandings of:

• how individuals and communities perceive health, manage their own health and make decisions related to health service usage

• the culture of communities and of organisations in relation to implementing change and overcoming barriers to the use of new knowledge and techniques

• how patients experience health, illness and the health system

• the usefulness, or otherwise, of components and activities of health services that cannot be measured in quantitative outcomes (such as health promotion and community development)

• the behaviours/experiences of health professionals, contexts of health care and why we behave/experience things in certain ways.

Qualitative research can generate evidence that informs clinical decision making on matters related to the feasibility, appropriateness or meaningfulness of a certain intervention or activity. Pearson et al.2 describe feasibility as the extent to which an activity is practical and practicable. Clinical feasibility is about whether or not an activity or intervention is physically, culturally or financially practical or possible within a given context. They define appropriateness as the extent to which an intervention or activity fits with or is apt in a situation. Clinical appropriateness is about how an activity or intervention relates to the context in which care is given. Meaningfulness refers to how an intervention or activity is experienced by the patient. It relates to the personal experience, opinions, values, thoughts, beliefs and interpretations of patients. Evidence-based practice in its fullest sense is about making decisions about the feasibility, appropriateness, meaningfulness and effectiveness of interventions—and quantitative and qualitative evidence are often of equal importance in this endeavour. Qualitative research does not always involve the evaluation of an intervention. It may also seek to understand how patients try to cope with their disease, or how they experience illness in a broader social–cultural context. Apart from focusing on an intervention, qualitative research can also focus on a certain phenomenon of interest.

This chapter explores the value of different qualitative methodologies that can be used in qualitative research to address patients' experiences and concerns. It also presents a stepwise approach to developing qualitative clinical questions and searching for, appraising and applying qualitative evidence. Clinical scenarios and relevant qualitative articles are used to illustrate these processes.

Qualitative research: the value of different philosophical perspectives and methodologies in researching patients' experiences and concerns

Qualitative research that focuses on patients' (and health professionals') experiences and concerns assists people to tell their stories about what it is like to be a certain person, living in a particular time and place, in relation to a set of circumstances, and analyses the data generated to describe human experience and meaning. Qualitative researchers collect and analyse words, pictures, drawings, photos and other non-numerical data because these are the media through which people express themselves and their relationships to other people and their world. This means that if researchers want to know what the experience of care is like, they will ask the people receiving that care to describe or visualise their experience in order to capture the rich meaning. Through these approaches, the enduring realities of people's experiences are not over-simplified and subsumed into a number or a statistic.

All research has underlying philosophical positions or assumptions. In qualitative research, two common philosophical perspectives are the interpretive and critical perspectives. Interpretive research is undertaken with the assumption that reality is socially constructed through the use of language and shared meanings. Therefore, interpretive researchers attempt to understand phenomena through listening to people or watching what they do in order to interpret their meanings.4 From the critical perspective, knowledge is considered to be value-laden and shaped by historical, social, political, gender and economic conditions. This in turn is thought to shape social structures and assumptions that, if they remain unquestioned, may serve to oppress particular groups.5 Critical approaches in qualitative research ask not just what is happening, but why, and seek to generate theory and knowledge in order to help people bring about change.

Different qualitative methodologies may be used depending on the underlying philosophical perspective. For example, phenomenology, grounded theory and ethnography as commonly used ‘interpretive’ methodological approaches to research because they all aim to describe and understand phenomena. Critical researchers, on the other hand, seek to generate change by bringing problems or injustices forward for conscious debate and consideration, and therefore may choose methodological approaches such as action research, feminism and discourse analysis. Although these six methodologies are discussed separately in this chapter, qualitative researchers often combine elements from different methodologies when undertaking their research. Different qualitative research approaches set out to achieve different things and when differing perspectives are put together, they provide a multifaceted view of the subject of inquiry that deepens our understanding of it. In this sense they are not substitutes for each other due to some essential superiority of one method over another, but rather they represent a theoretical ‘tool kit’ of devices. Depending on the task at hand, one methodology on one occasion may be a more useful tool than another. We will describe these six commonly used methodologies below.

Qualitative methodologies used in health research

Interpretive approaches to research

Phenomenology

A phenomenological research approach values human perception and subjectivity and seeks to explore what an experience is like for the individual concerned.6 The basis of this approach is a concept called ‘lived experience’, which means that people who are living presently, or have lived an experience previously, are in the best position to speak of it, to inform others of what the experience is like or what it means to them. Phenomenology is concerned with discovering the ‘essence’ of experience. It usually draws on a very small sample of 3 to 10 research subjects, asking the question: ‘What was it like to have that experience?’ Large sample sizes such as those found in quantitative research are not required in qualitative research, as the aim is to gather detailed information to understand the depth and nature of experiences. Data are collected using a focused, but non-structured, interview technique to elicit descriptions of the participant's experiences. This style of interview supports the role of the researcher as one who does not presume to know what the important aspects of the experience to be revealed are. Several steps are involved in thematic data analysis.6 The interviews are transcribed verbatim and read by researchers who attempt to totally submerge themselves in the text in order to identify the implicit or essential themes of the experience, thus seeking the fundamental meaning of the experience.

The strength of the phenomenological method is that it seeks to derive meaning and knowledge from the phenomena themselves and, although it is generally conceded that unmediated access to a phenomenon is never a possibility (that is, the exclusion of all prior perceptions and research bias), the emphasis on the experience of the participants ensures that this model represents as closely as possible the participants' perspective.7,8 In this sense the perspectives that arise from the phenomenological approach help to shape the categories of concern in terms of the issues that the participants themselves identify. Through the phenomenological method, participants contribute substantially to informing and describing the field of inquiry that future policy needs to address.

Grounded theory

Grounded theory is a methodology developed by sociologists Glaser and Strauss9 to express their ideas of generating theory from the ‘ground’ to explain data collected during the study, using an ‘iterative’ (or cyclical/circular) approach whereby data are gathered using an ongoing collection process from a variety of sources. Grounded theorists use a theoretical sample of people that are most likely to be the best informants to deliver the building blocks for the theory to be developed. Theoretical samples work towards a saturation point. That is, the point in which no new themes or issues emerge from the data. Glaser and Strauss developed this approach in their ground-breaking work on death and dying in hospitals.9 Strauss and Corbin10 have developed an approach that begins with open coding of data and requires the researcher to take the data apart. The approach distinguishes itself from phenomenology in putting a heavy emphasis on understanding the parts from a text to construct the overall picture of ‘What is going on here?’

Ethnography

The term ethnography was used originally to describe a research technique that was used to study groups of people who: shared social and cultural characteristics; thought of themselves as a group; and shared common language, geographical locale and identity. Classic ethnographies portray cultures, providing ‘a portrait of the people’ (the literal meaning of the term ethnography), and move beyond descriptions of what is said and done in order to understand ‘shared systems of meanings that we call culture’.11 An ethnographer comes to understand the social world of the group in an attempt to develop an inside view while recognising that it will emerge from an outside perspective. In this sense the researcher attempts to experience the world of the ‘other’ (euphemistically referred to as ‘going native’), while appreciating that the experience emerges through the ‘self’ of the researcher. Ethnography involves participant observation, the recording of field notes and interviewing key informants. The identifying feature of participant observation is the attempt to reconstruct a representation of a culture that closely reflects ‘the native’s point of view’.

Critical approaches to research

Action research

Action research is the pursuit of knowledge through working collaboratively on describing the social world and acting on it in order to change it. Through acting on the world this way, critical theory and understandings are generated. Action research asks the question, ‘What is happening here and how could it be different?’ It involves reflecting on the world in order to change it and then entering into a cyclical process of reflection, change and evaluation. Data collected in action research include transcripts of group discussions as well as quantitative and qualitative data suggested by the participative group. Both of these types of data are analysed concurrently. Themes, issues and concerns are extracted and discussed by both the research team and the participative group. Action research provides a potential means for overcoming the frequent failure of externally generated research to be embraced by research consumers, who often regard this form of research as unrelated to and not associated with their practice.

Discourse analysis

Discourse analysis has its roots in postmodern thinking and emerged in a number of academic disciplines in the last two or so decades of the 20th century. It has played an important role in creating new ways of developing ideas in the arts, science and culture. At its simplest (and it is far from simple!), postmodernism is a response to modernity—the period when science was trusted and represented progress—and essentially focuses on questioning the centrality of both science and established principles, disciplines and institutions to achieving progress. The nature of ‘truth’ is a recurring concern to postmodernists, who generally claim that there are no truths but instead there are multiple realities and that understanding of the human condition is dynamic and diverse. The notion that no one view, theory or understanding should be privileged over another is a belief of postmodernist critique and analysis. The scrutiny and breakdown of ideas that are associated with postmodernism are most frequently applied through the discursive analysis of texts. Discourse is defined as to ‘talk, converse; hold forth in speech or writing on a subject; give forth’.12 Thus, discourse analysis essentially refers to the capturing of public, professional, political and even private discourses and deconstructing these ‘messages’. Discursive analysis aims at revealing what is being said, thought and done in relation to a specific topic or issue.

Hopefully by now you will have realised that qualitative research evidence is an important source of knowledge related to the ‘culture, practices, and discourses of health and illness’.13,14 The value of such research and its methodologies lies in its ability to systematically examine questions about issues such as experiences, opinions and reasons for behaviours that are unable to be answered by means of quantitative research that often uses frequencies and associations.

Using qualitative evidence: a stepwise approach

Structuring a qualitative question

The team that was described in the clinical scenario at the beginning of this chapter want to find out what receiving care from a large primary healthcare team is like for people who have a chronic illness. The PICO format that was described in Chapter 2 does not do justice to the variety of qualitative questions that can emerge within different methodologies; however, it is a helpful tool to structure qualitative questions. Generally there is no ‘comparison’ in a qualitative question, and the ‘I’ refers to ‘interest’ or ‘issue’ rather than intervention. And sometimes you may wish to add the term ‘evaluation’, as this is more appropriate than outcome (‘What are we evaluating in the study?’).

Searching for qualitative evidence

Because the question for our clinical scenario explicitly seeks qualitative information, the team will clearly need to search for qualitative research articles. It may be clear from the previous section that using the term ‘qualitative research’ is, however, in itself problematic. The word ‘qualitative’ is frequently used to describe a singular, specific methodology (for example, ‘in this study a qualitative methodology was pursued’), when in its broadest sense it is an umbrella term that encompasses a wide range of methodologies stemming from a number of diverse traditions.

Finding qualitative research papers through database searches is often difficult.15 It has been claimed that finding quantitative studies is much easier because the progress that has been made in indexing specific quantitative designs has not been paralleled in the qualitative domain. In Chapter 3, we provided you with some search strategies for locating qualitative research in MEDLINE, CINAHL, Embase and PsycINFO (refer to Table 3.1 in Chapter 3). For example, you may remember that, in MEDLINE, the best multiple-term strategy that minimised the difference between a sensitive and a specific search16 was to combine the content terms with the following methodological terms: interview:.mp. OR experience:.mp. OR qualitative.tw. However, if you wish to look for a particular method, relevant terms such as phenomenology or grounded theory will need to be used.

Critically appraising qualitative evidence—is the evidence likely to be biased?

Qualitative approaches are located in diverse understandings of knowledge; they do not distance the researcher from the researched; and the data analysis is legitimately influenced by the researcher when they interpret the data. This poses considerable challenges in appraising the quality of qualitative research. Dixon-Woods, Agarwal and Smith18 suggest that ‘there are now over 100 sets of proposals on quality in qualitative research’ and it seems to be unlikely that the international research community will come to an agreement on which particular instrument to put forward as the standard for quality appraisal in qualitative research, at least in the short term. A useful point to start the process of quality appraisal is to read the chapter on critical appraisal of qualitative research written by the Cochrane Qualitative Research Methods Group and available as supplemental guidance to the Cochrane Handbook of Systematic Reviews of Interventions.19 Although it focuses on qualitative evidence appraisal in the context of systematic reviews, it lists the core concepts to be considered in quality appraisal of qualitative research and a selection of instruments that are available for quality appraisal. It also provides some guidance on the phases that need to be considered in critical appraisal and on how to deal with the outcome of a critical appraisal exercise.20

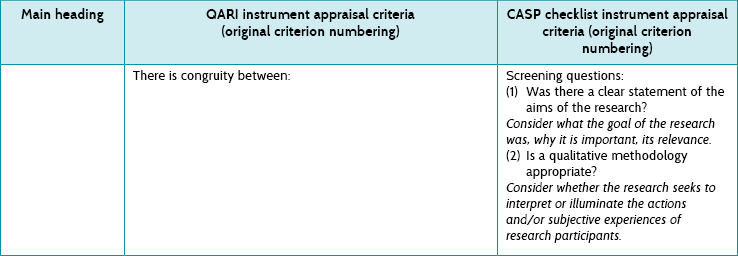

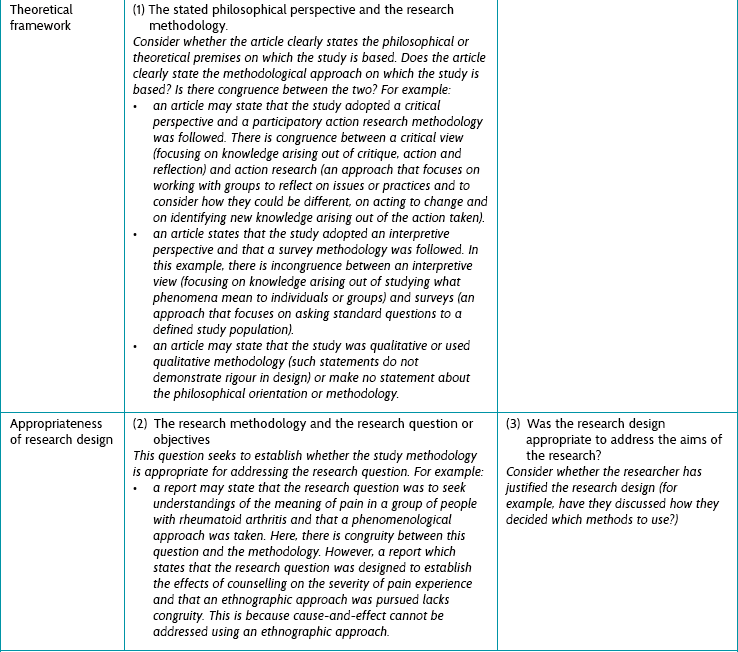

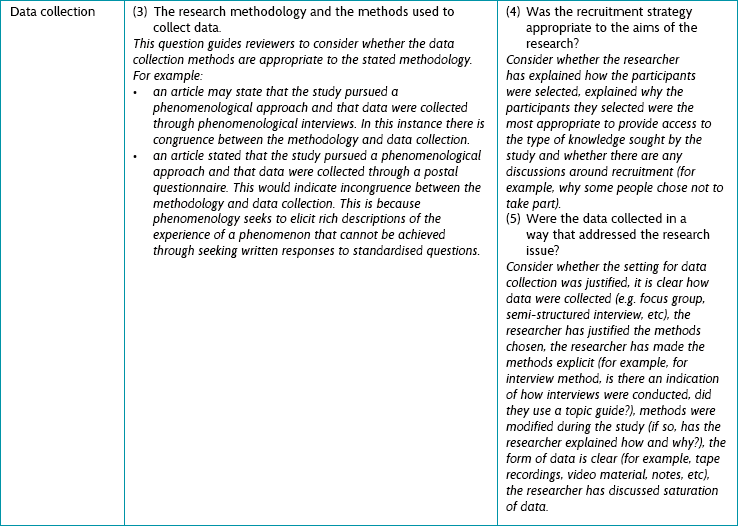

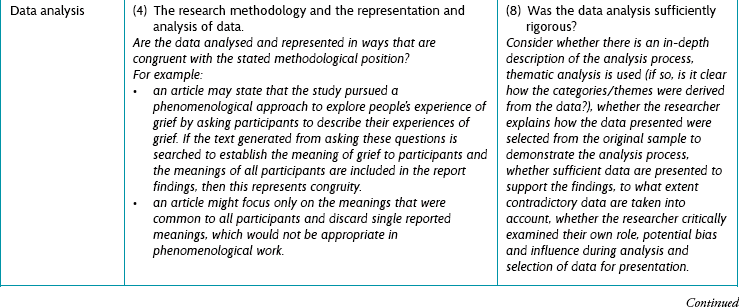

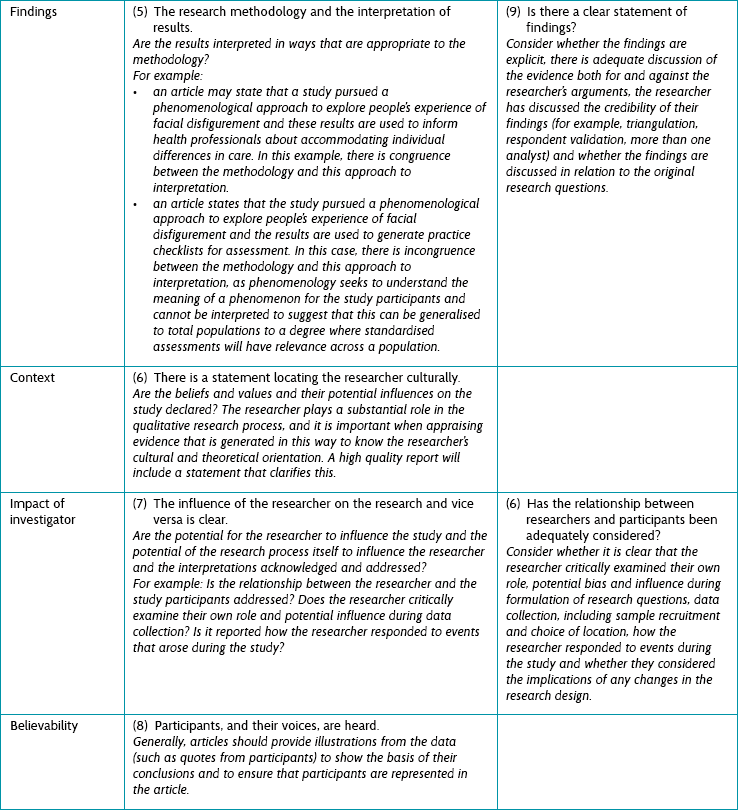

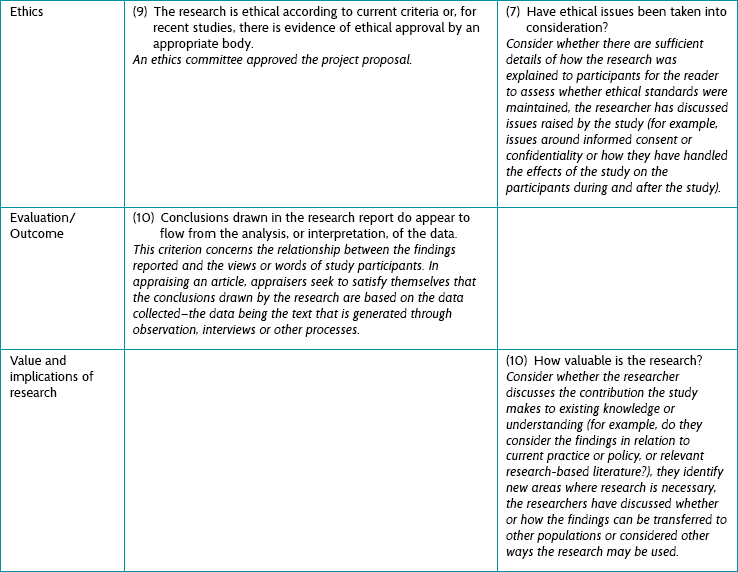

In the rest of this chapter we will cross-compare the quality criteria and discuss some of the strengths and weaknesses of two commonly used critical appraisal tools: the QARI (Qualitative Assessment and Review Instrument)21 critical appraisal instrument and the CASP (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme)22 instrument. Both instruments contain 10 quality criteria.

In this comparison we will emphasise the extent to which both instruments facilitate the assessment of validity in qualitative research. In earlier chapters of this book you have seen that assessing the risk of bias of a study is also a major aim when critically appraising quantitative data. Validity in quantitative research is assessed by establishing the extent to which the design and conduct of a study address potential sources of bias. This focus on limiting bias to establish validity does not fit with the philosophical foundations of qualitative approaches to inquiry. There is no emerging consensus on what the actual focus of quality appraisal in qualitative research should consist of. Some argue that the focus should be on the rigour of the research design as well as on the quality of reporting. Others argue that quality of reporting is only a facilitator of appraising qualitative research papers and that the main focus should be on evaluating validity, referring to the kinds of understanding we have of the phenomena under study (accounts identified by researchers) and whether or not these are subject to potential flaws. Potential flaws can occur, for example, in the translation from statements of study participants into researcher statements or from study findings into a conclusion.

We tend to adopt the latter approach, emphasising that statements need to be grounded in research evidence, that we need to know whether statements from a researcher accurately reflect the ideas participants intended to reveal, and that the set of arguments or the conclusion derived from a study necessarily follows from the premises. To facilitate comparison between the QARI and the CASP, we took the 11 main headings (left column of Table 10.1) reported in Hannes et al23 and adapted the original table for the purpose of this comparison.

Earlier we indicated that the philosophical stance one takes influences the research methodology one uses for research. In the same way, the methodological position chosen influences the way in which data are collected.4 One feature of the QARI tool, that is not present in the CASP tool, is to check the congruence between these aspects of a study. QARI also focuses on the extent to which the influence of the researcher is acknowledged, and that what participants said is represented in the findings and form the basis of any conclusions drawn.

The CASP checklist, with its pragmatic focus on the different phases in a research project, does not engage with the theoretical and paradigmatic level for which one needs to be an experienced qualitative researcher. As a consequence it is more friendly to novice researchers. Overall, CASP does a better job than QARI in capturing the audit trail of individual studies and, as such, enables reviewers to evaluate whether a study has been conducted according to the ‘state of the art’ for a particular method. Specifically, the CASP tool reminds the reader to think about the idea of rigour (whether thorough and appropriate approaches have been applied to key research methods in the study); credibility (whether the findings are well presented and meaningful); and relevance (how useful the findings are to you and your organisation). Within the qualitative research tradition, there are specific strategies that the researcher can use to improve the credibility of the research, and these are indicated in the CASP tool as a prompt for the reader to consider them. For example, the researcher may make use of triangulation and respondent validation. To explain further: triangulation occurs when data are collected and considered from a number of different sources, which may help to confirm the findings or to increase the completeness of data collected.24 Respondent validation (also known as member checking) is where the researcher seeks confirmation and clarification from the participants that the data accurately reflect what they meant or wanted to say.

Another important feature of qualitative research is that the researcher is integral to the research process. It is therefore important that their role is considered and explained in the research report. The CASP tool prompts the reader to ask whether the researcher critically examined their own role, potential bias and influence during analysis and selection of data for presentation. One of the strengths of the QARI tool is that it suggests that the reader evaluate whether or not the researchers have reflected on their cultural and theoretical background and provided a rationale for the methodological choices made to control their impact on the research. However, it goes even further—also evaluating whether researchers have invested in an epistemological type of reflexivity. Thinking about how the choice of method might have influenced the findings is equally as important as thinking about what the potential impact of the researcher has been.

To illustrate the critical appraisal process, we will evaluate the clinical scenario using the 10 QARI criteria. Additional insights generated by using the CASP tool are added at the end of each of the QARI comments.

Further comments comparing the QARI and CASP approaches to critical appraisal

Before finishing off this section on critical appraisal, we will highlight some of the interesting topics we came across when evaluating this particular study with the quality criteria of both the QARI tool and the CASP checklist. The most important issue is that the influence of the researcher on the research, or vice versa, is hardly addressed in this study and neither is the cultural or theoretical background of the researchers. The lack of sensitivity to these issues can be problematic, because most qualitative research is largely inductive. Researchers typically look at reality and try to develop a theory from the information derived from the field. The philosophical position of the researcher towards the research project determines not only the choice of an appropriate method, but also the window through which he or she will be looking at the data. It has a direct impact on the way the findings will be interpreted and presented. Therefore, a research project that does not reveal what view of reality the researcher holds can be called highly mechanistic.23

We have highlighted the fact that there are several methodologies which could be considered in qualitative research. If you decide to go down one particular path, you need to understand and articulate how the knowledge tradition you opt for, together with its claims to understanding, influence your data collection, analysis and conclusion. Clarifying and justifying the window that determines your view will allow an experienced reviewer to judge the impact of your theoretical and methodological choices.

There are some other interesting differences between the instruments compared, as reported by Hannes et al.23 The QARI tool does not include an item about relevance or transferability (which the CASP checklist addresses in item 10). Whether or not ‘relevance’ is an issue that needs to be evaluated in the context of a critical appraisal exercise is debatable. Like ethics, the ‘relevance’ criterion most likely has its roots in the idea that research should address the concerns of health professionals rather than be the product of individual academic interest. This also raises the important question of whether or not an ethics approval has direct implications on the methodological quality of a study. To conclude our comments about these two approaches for appraising qualitative research, both instruments can assist us in evaluating methodological quality of studies; however, their approach to appraising qualitative research is somewhat different.

How, then, do we make sense of the appraisal as a whole? Pearson21 offers the following categorisation of judgment about a qualitative article. Overall the article may be considered:

• Unequivocal: the evidence is beyond reasonable doubt and includes findings that are factual, directly reported/observed and not open to challenge.

• Credible: the evidence, while interpretative, is plausible in light of the data and theoretical framework. Conclusions can be logically inferred from the data but because the findings are essentially interpretative, these conclusions are open to challenge.

• Unsupported: findings are not supported by the data and none of the other level descriptors apply.

The next issue to consider is how we might use the findings in practice.

Applying qualitative evidence

Research from qualitative studies can inform health professionals' thinking about similar situations/populations that they are working with. However, the way in which findings from qualitative evidence might be used in practice differs from quantitative research. Quantitative research findings are reported in terms of the probability (for example) of an outcome occurring when a particular intervention is implemented, in the same way, for a defined patient group. This therefore requires health professionals to accept a generalisation that the research findings can be applied to patients similar to those participating in the study. In quantitative research, this concept is referred to as generalisability. There are objections to the application of qualitative findings in practice because of the theoretical underpinnings of many qualitative methodologies. Principally this relates to the idea that ‘truth’ is contextual, or for certain methodologies ‘in the moment’, and therefore only representative of a particular person or group at that time and within that context. Therefore it is argued that the findings of a qualitative study of one group of people in a single study cannot be extrapolated to other people, groups or contexts. Researchers who follow this line of argument claim that the pooling and/or application of qualitative findings is, in effect, an attempt to formulate a result that can be generalised across a population and, as such, is an inappropriate use of qualitative findings.

Other researchers have developed a strong opposing view and suggest that the term generalisability is being misinterpreted. Sandelowski and colleagues25 have put forward that the argument against the pooling or application of qualitative findings is founded on a ‘narrowly conceived’ view of what constitutes generalisability—that is, a view that sees it in relation to the representativeness (in terms of size and randomisation) of a sample and of statistical significance. They argue that qualitative research has the capacity to produce generalisations—but they are suggestive or naturalistic (or realistic) in nature rather than generalisations that are predictive, as is the case in quantitative research.25 The CASP checklist adds the criterion of relevance or transferability of findings as an important issue to be evaluated when reading a research paper and, depending on the type of qualitative design used, it seems reasonable to do so. There is little reason to believe that a theoretical or conceptual model that is based on a theoretical sample that used a maximum variation strategy (sampling to maximise diversity of participants represented), reached a point of saturation and was tested in different settings (for example, as grounded theory approaches do) could not be considered generalisable or relevant to other settings. However, bear in mind that many qualitative researchers aim to just understand a phenomenon, rather than to generalise the findings to other settings.

References

1. Pearson, A, Wiechula, R, Court, A, et al. The JBI model of evidence-based healthcare. Int J Evidence-based Healthcare. 2005; 3:207–215.

2. Pearson, A, Field, J, Jordan, Z. Evidence-based clinical practice in nursing and health care. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing; 2007.

3. Denzin, NK. The art and politics of interpretation. In: Denzin N, Lincoln Y, eds. Handbook of qualitative research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1994:500–515.

4. The Joanna Briggs Institute, CSR Study Guide Module 4. The systematic review of evidence generated by qualitative research, narrative and text. The Joanna Briggs Institute, Adelaide, South Australia, Australia, 2012. Online Available www.joannabriggs.edu.au/documents/train-the-trainer/module4/ttt_m4_studyguide.pdf [15 Jul 2012].

5. Berman, H, Ford-Gilboe, M, Campbell, JC. Combining stories and numbers: a methodologic approach for a critical nursing science. Adv Nurs Sci. 1998; 21(1):1–15.

6. van Manen, M. Researching lived experience: human science for an action sensitive pedagogy. Toronto: Althouse Press; 1997.

7. Koch, T. Establishing rigour in qualitative research: the decision trail. J Adv Nurs. 1993; 19:976–986.

8. Koch, T. Implementation of a hermeneutic inquiry in nursing: philosophy, rigour and representation. J Adv Nurs. 1996; 24:174–184.

9. Glaser, B, Strauss, A. The discovery of grounded theory: strategies for qualitative research. New York: Aldine de Gruyter; 1967.

10. Strauss, A, Corbin, J. Basics of qualitative research: grounded theory procedures and techniques. London: Sage; 1990.

11. Boyle, J. Styles of ethnography. In: Morse J, ed. Critical issues in qualitative research methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1994:159–185.

12. Concise Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1964.

13. McCormick, J, Rodney, P, Varcoe, C. Reinterpretations across studies: an approach to meta-analysis. Qual Health Res. 2003; 13:933–944.

14. Green, J, Britten, N. Qualitative research and evidence based medicine. BMJ. 1998; 316:1230–1232.

15. Shaw, R, Booth, A, Sutton, A, et al. Finding qualitative research: an evaluation of search strategies. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2004; 4:5.

16. Wong, S, Wilczynski, N, Haynes, RB, et al. Developing optimal search strategies for detecting clinically relevant qualitative studies in MEDLINE. Medinfo. 2004; 11:311–316.

17. Freeman, G, Shepperd, S, Robinson, I, et al, Report of a scoping exercise for the National Co-ordinating Centre for NHS Service Delivery and Organisation R&D (NCCSDO). NCCSDO, London, 2000. Online Available www.netscc.ac.uk/hsdr/files/project/SDO_ES_08-1009-002_V01.pdf [19 Nov 2012].

18. Dixon-Woods, M, Shaw, R, Agarwal, S, et al. The problem of appraising qualitative research. Qual Saf Health Care. 2004; 13:223–225.

19. Higgins JPT, Green S, eds. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration: 2011. Online Available www.cochrane-handbook.org [8 Nov 2012].

20. Hannes, K, Chapter 4: Critical appraisal of qualitative researchNoyes J, Booth A, Hannes K, et al, eds. Supplementary guidance for inclusion of qualitative research in Cochrane systematic reviews of interventions. Version 1 [updated August 2011]. Cochrane Collaboration Qualitative Methods Group: 2011. Online Available cqrmg.cochrane.org/supplemental-handbook-guidance [8 Nov 2012].

21. Pearson, A. Balancing the evidence: incorporating the synthesis of qualitative data into systematic reviews. JBI Reports. 2004; 2:45–64.

22. Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP), 10 questions to help you make sense of qualitative research. Public Health Resource Unit, England, 2006. Online Available www.casp-uk.net/wp-content/uploads/2011/11/CASP_Qualitative_Appraisal_Checklist_14oct10.pdf [14 Nov 2012].

23. Hannes, K, Lockwood, C, Pearson, A. A comparative analysis of three online appraisal instruments’ ability to assess validity in qualitative research. Qual Health Research. 2010; 20:1736–1743.

24. Shih, F. Triangulation in nursing research: issues of conceptual clarity and purpose. J Adv Nurs. 1998; 28(3):631–641.

25. Sandelowski, M, Docherty, S, Emden, C. Focus on qualitative methods. Qualitative metasynthesis: issues and techniques. Res Nurs Health. 1997; 20:365–371.