Finding the evidence

After reading this chapter, you should be able to:

• Describe the basic principles of efficient searching

• Understand how literature services are organised

• Be aware of the major online evidence-based resources and how they fit into the organisation of literature services

• Be aware of the discipline-specific online evidence-based resources

• Know which databases will be likely to have an answer when searching for evidence for each type of question (that is, intervention, diagnosis, prognosis and qualitative)

One of the most important and challenging aspects of implementing evidence-based practice can be finding the current best evidence relevant to your clinical question. The internet provides ready and free access to information, but the information explosion and the ever-increasing availability of online resources makes finding the current best evidence difficult. Many online resources falsely claim to be ‘evidence-based’, making it difficult for health professionals to navigate internet sites. In addition to discerning whether the information provided on the internet site is based on sound evidence, research shows that some of the obstacles that are most frequently encountered when attempting to find the answer to a clinical question are:

• the excessive amount of time required to find information

• difficulty in selecting an optimal filter to search for information

• failure of the selected resource to provide an answer.1

These barriers can be reduced by approaching the search for the current best evidence in a systematic way that harnesses the organisation of the literature to your advantage. In this chapter we will show you some of the main ways that you can do this. We will begin by describing the basics of searching, followed by a description of a model that outlines a categorisation of evidence-based information services and how this evidence is processed and presented. Within each category of this model, we will describe the types of evidence that are included and the resources that are available to find that type of evidence. We will concentrate on the resources which have the strongest evidence base, as these resources are the ones that are likely to be of most use to you in your clinical practice and are also typically the resources that are easier and faster to use. The chapter concludes with a number of clinical questions and examples of how you can find an answer to these questions using the model and the information resources described in the chapter.

The basics of searching

So that your search for evidence is as efficient as possible, it is a good idea to understand some of the basic principles of effective searching, which are:

1. Carefully define your clinical question.

2. Choose your key search terms.

3. Broaden your search if necessary, with synonyms, truncation and/or wildcards.

Carefully define your clinical question

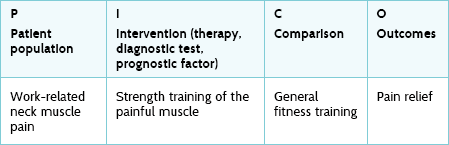

Information about how to construct a well-formulated clinical question, using the PICO format, was provided in Chapter 2.

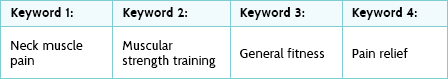

Choose your key search terms

Using the PICO format to structure your clinical question makes choosing key search terms relatively easy. Typically you would start your search using the ‘P’ (patients [or population]) and ‘I’ (intervention) terms or phrases from your question. For example, if your question was ‘In people with chronic low back pain, is an operant–behavioural graded activity program more effective than physical training in improving functional ability?’ you would start your search with the phrases "chronic low back pain" (‘P’ terms) and "operant-behavioural graded activity" (‘I’ terms).

Broaden your search if necessary

Once you have identified key terms or phrases, you should consider broadening your search, particularly if your initial search yields no relevant articles.

• The first way to broaden your search is to consider using synonyms and related terms. For example, if you are searching for articles on patients with "rheumatoid arthritis" you can broaden your search by also searching with the terms "RA" and "rheumatologic disease". Several online resources list synonyms and related terms for many diseases and conditions, for example, eMedicine from WebMD (emedicine.medscape.com; choose a specialty and then a condition), eMedicineHealth from WebMD (www.emedicinehealth.com/script/main/hp.asp) and Genetics Home Reference from the US National Library of Medicine (ghr.nlm.nih.gov/glossary).

• Another way to widen your search is to use truncation and wildcards.

• When using truncation in a search you enter the first part of a keyword, insert a symbol (usually an asterisk symbol*), and accept any variant spellings or word endings from the occurrence of the symbol onwards. For example, "disease*" would retrieve records with the word disease, as well as the words diseases, diseased, etc.

• When using wildcards in a search you enter a wild card character (usually "?") within or at the end of a keyword to substitute for only one character. Wildcards are particularly useful when searching for some plural forms, such as "wom?n", which would retrieve records with the words woman and women. Wildcards are also very useful when searching for terms where there is a variation between the American and Australian spelling of words such as orthopaedic and paediatric. Searching with the term "orthop?edic" will find articles that use orthopaedic as well as orthopedic.

• Truncation symbols and wildcard characters vary between databases and database providers; for example, in PubMed the truncation symbol is an asterisk (*), whereas when searching MEDLINE in Ovid it is a colon (:) or dollar sign ($). Consult each database's online help section to determine which symbols or characters to use.

Use Boolean operators

Once you have determined the terms or phrases that you will include in your search, you should consider combining your search terms using the Boolean logical operators.

• The Boolean AND command is used when you want all search terms to be present in each article that is retrieved. For example, when searching using ‘P’ terms and ‘I’ terms you would combine these using the Boolean AND command as you would want to retrieve articles that have both your patient/population of interest and the intervention of interest. Using our back pain example above, your search filter would be "(chronic low back pain) AND (operant-behavioural graded activity)", thus narrowing your search.

• The Boolean OR command is used when you want any of the specified search terms to be present in the articles. When incorporating synonyms and related terms you would search using the Boolean OR command, for example "rheumatoid arthritis OR RA OR rheumatologic disease", thus broadening your search. When using this search you will retrieve articles that use any one of ‘rheumatoid arthritis’ or ‘RA’ or ‘rheumatologic disease’. How search terms should be grouped together—that is, whether "double inverted commas" or brackets () should be used—varies between different databases, so it is useful to check this in the database's help section.

Basics of searching—an example

To illustrate these basics of searching further, we will work through a step-by-step example.

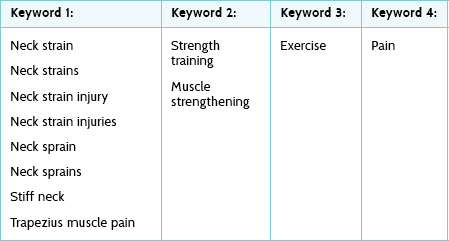

A model of evidence-based information services

In this chapter we will use a six-level pyramid to discuss the organisation of evidence-based information services.2 This ‘6S’ model (see Figure 3.1) is hierarchical in nature and has:

Figure 3.1 The 6S pyramid showing levels of organisation of evidence from healthcare research. Reproduced with permission from DiCenso A, Bayley L, Haynes RB, Assessing preappraised evidence: fine-tuning the 5S model into a 6S model. American College of Physicians; 2009.2

• original studies (what was done in one study) at the base

• synopses of studies (what the evidence is in one study, along with an expert telling you its strengths and potential practice changes)—that is, succinct descriptions of original studies often accompanied by expert commentaries such as those found in evidence-based secondary journals like ACP Journal Club

• syntheses (what the evidence is across several studies on the same topic)—that is, systematic reviews of the literature

• synopses of syntheses (what the evidence is across several studies, along with an expert telling you its strengths and potential practice changes)—that is, succinct descriptions of systematic reviews, often accompanied by expert commentaries such as those found in evidence-based secondary journals like ACP Journal Club

• summaries—that is, management options for diseases or conditions arranged by clinical topics such as those that appear in the online resources Physicians' Information and Education Resource (PIER) and Clinical Evidence (quite like a textbook chapter with a broad-based summary of a content area)

• systems—that is, integrated decision support services which provide evidence plus ‘actions’ that should be taken in relation to a specific patient or situation.

As you are seeking the current best evidence, begin your search as high up in the pyramid as possible. The higher you go in the pyramid, the more the evidence has been collected, sifted and synthesised. As the synthesis and evaluation work has already been done by others, using evidence from the higher levels will save you time and labour and assist you to apply the best quality evidence that is currently available.

Deciding where to start on the pyramid depends largely on the question being asked and what resources are available to you. As explained earlier, you should be guided by the hierarchy of evidence for the type of question that you are asking. Additionally, you will also find that much of the content available at the higher levels of the pyramid is aimed at the medical profession, and that most of the evidence for nursing and allied health questions are found in levels one (bottom) and three of the pyramid and, at times, levels two and four. At each level of the ‘6S’ pyramid, users of the evidence must appraise the quality of the evidence presented to ensure that the methods used to generate this evidence were sound. Detailed information about how to critically appraise evidence, once you have found it, is presented in Chapters 4–13 of this book. Each level of the pyramid will now be discussed further, starting at the top of the pyramid, where the best and most highly synthesised evidence can be found.

Systems—first layer (top) of the pyramid

Systems are found at the top of the ‘6S’ pyramid. A system is an integrated clinical decision support service designed to improve clinical decision making. Such a system may be integrated into an electronic patient health record system or hospital clinical information system. Alternatively, the system may allow for entry of patient-specific characteristics, such as age, gender, renal function and allergy history. These computerised decision support systems reliably link patient characteristics with the current evidence-based guidelines for care. The system generates patient-specific recommendations (for example, lower the dose of insulin because of hypoglycaemic events or schedule a blood test because it is due next month). A key component of a clinical decision support service that differentiates it from other types of evidence-based information services is the integration of patient-specific variables.

Clinical decision support systems have been developed for various clinical issues, including the diagnosis of chest pain, the management of chronic disease (such as diabetes care) and the timely administration of preventive services (such as immunisations). Systematic reviews of the effects of computerised clinical decision support systems showed that some may improve health professionals' performance.3–8 If you have such a system in your workplace, you are lucky as it is likely that you will not need to look further for the best evidence to answer your clinical question. However, most people will not be able to begin their search at the top of the pyramid because systems are relatively rare, existing for only a few diseases or conditions, and usually have a medical focus. Not all health professions have electronic patient medical records and, even if they do, many are not integrated with a decision support system that has an evidence-based guideline summarising the current best evidence on a topic of interest. Therefore, if you do not have access to a system that addresses your information needs, you will need to start your search for the current best evidence at the next level down in the pyramid.

Summaries—second layer of the pyramid

Summaries are information resources that provide regularly updated evidence, which is usually arranged by clinical topics. They are considered to be similar to traditional textbook chapters in form and content. Evidence-based clinical guidelines are also located at this level of the pyramid. Summaries provide guidance and/or recommendations for patient management and often provide links to other aspects of the disease or condition. Summaries can be found in disease-specific textbooks such as Evidence-based endocrinology9 but, unless the textbook is accompanied by a website where the content can be regularly updated, the content in a print textbook quickly becomes outdated. Online textbooks that are regularly updated are becoming more common. Medicine has the most of these online textbooks, and some of these contain information which may be of interest to allied health professionals or nurses. All of the online textbooks listed as examples below are available on a subscription basis, but many workplaces, particularly academic and healthcare institutions, may have institutional subscriptions.

• Clinical Evidence (clinicalevidence.bmj.com/ceweb/index.jsp) is provided by the BMJ Publishing Group and summarises evidence on the benefits and harms of healthcare interventions for selected medical conditions. The evidence is drawn from systematic reviews and original studies. The content is presented in question format (for example, What are the effects of interventions aimed at reducing relapse rates and disability in people with multiple sclerosis?), with the levels of evidence used to answer the question and hyperlinks to the supporting evidence. A clinical guide (that is, a comment on how to use this information in clinical practice) is also presented.

• Best Practice (bestpractice.bmj.com/best-practice/welcome.html) is provided by the BMJ Evidence Centre (a division of the BMJ Group) and incorporates Clinical Evidence. The service combines the latest research evidence, guidelines and expert opinion regarding prevention, diagnosis, treatment and prognosis using a step-by-step approach (that is, presented for each medical condition/disease are highlights, basics, prevention, diagnosis, treatment and follow-up). Recommendations are supported with links to the evidence.

• Physician's Information and Education Resource (PIER) (pier.acponline.org/index.html), from the American College of Physicians (ACP), is an integrated summary service that provides evidence-based guidance and practice recommendations for health professionals. It is organised into seven topic types (diseases, screening and prevention, complementary and alternative medicine, ethical and legal issues, procedures, quality measures and drug resources), with each topic containing several modules. PIER's authors are supported by an explicit evidence-based process, where current best evidence is provided to the authors of the chapters after comprehensive literature searches are conducted.

PIER is available online to ACP members and can also be accessed through STAT!Ref (www.statref.com), an online healthcare reference that provides full-text access to key medical reference sources and textbooks, some of which are evidence-based resources. STAT!Ref is a subscription-based resource that is usually available in academic or hospital environments where institutional subscriptions exist. PIER is more directive than Clinical Evidence, as it contains recommendations rather than evidence summaries.

• UpToDate (www.uptodate.com) is an online textbook that is very comprehensive in its topic coverage. It is currently organised into 17 medical specialties (for example, adult primary care and internal medicine, cardiovascular medicine, endocrinology and diabetes, family medicine). UpToDate provides specific recommendations (guidelines) for health professionals for patient care and most, but not all, of these recommendations include an assessment of the quality of the evidence.

• First Consult (www.firstconsult.com/php/376749460-30/home.html) is part of MD Consult, from Elsevier, and is an evidence-based and continuously updated clinical information resource for primary care clinicians. Designed for use at point-of-care (for example at the bedside, in the clinic), information is arranged around the components of medical topics, differential diagnosis and procedures. Recommendations are made and the levels of evidence and links to supporting evidence accompany some recommendations.

• DynaMed (dynamed.ebscohost.com), from EBSCO Publishing, is a clinical reference tool for use at the point-of-care (for example at the bedside, in the clinic). It has clinically-organised summaries for more than 3200 topics. Recommendations are made and the levels of evidence and links to supporting evidence accompany some recommendations.

• EBM Guidelines: Evidence-Based Medicine (onlinelibrary.wiley.com/book/10.1002/0470057203), from Wiley Interscience, is a collection of clinical guidelines for primary care combined with the best available evidence. There are approximately 1000 primary care practice guidelines, which are continuously updated and cover a wide range of medical conditions. Both diagnosis and treatment are included.

Synopses of syntheses—third layer of the pyramid

If you do not find an answer to your clinical question in a summary, the next best place to search for an answer is in synopses of syntheses. Synopses of syntheses are structured abstracts or brief overviews of published systematic reviews that have been screened for methodological rigour. This means you do not have to do this step yourself! Synopses of syntheses can be found in the following online resources:

• ACP Journal Club (www.acpjc.org) is a pre-appraised secondary journal that is available online as well as in print within the Annals of Internal Medicine. To produce the content for this journal, research staff hand-search over 120 core healthcare journals and critically appraise the articles in each issue to identify high-quality primary studies and review articles that have potential for clinical application. From this pool of articles, practising health professionals rate the content for relevancy and newsworthiness. The studies and reviews that are considered to be the most clinically important are summarised in structured abstracts. A clinical expert comments on the methods and provides a clinical bottom line (that is, how to use the evidence in clinical practice).

The focus of the content in ACP Journal Club is internal medicine, and it includes sections on therapy, diagnosis, prognosis, aetiology, quality improvement and continuing education, economics, clinical prediction guides and differential diagnosis. As well as being a subscription-based resource, ACP Journal Club is one of the databases available through Ovid (gateway.ovid.com), a company that designs search engines and makes several evidence-based databases available on a subscription basis. Many institutions such as libraries, hospitals and universities use Ovid and therefore have institutional subscriptions.

• Evidence-Based Nursing (http://ebn.bmj.com), Evidence-Based Medicine (http://ebm.bmj.com) and Evidence-Based Mental Health (http://ebmh.bmj.com) are all currently published by the BMJ Publishing Group. Articles and reviews that meet specified criteria for rigour and relevance to nursing, general medicine and mental health, respectively, are selected for inclusion. A commentary is provided that identifies the key findings and implications for clinical practice.

• Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE) (www.crd.york.ac.uk/crdweb) is produced by the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD) at the University of York in the United Kingdom and contains abstracts of quality-assessed non-Cochrane systematic reviews. Each abstract includes a summary of the review together with a critical commentary about the overall quality of the review. DARE covers a broad range of health-related interventions. At the time of writing, DARE included over 21,000 abstracts of systematic reviews. When searching on the CRD website, content is retrieved from DARE, NHS EED (National Institute for Health Research Economic Evaluation Database) and HTA (Health Technology Assessment Database) simultaneously. DARE, as well as NHS EED and HTA, are available free of charge.

• Bandolier (www.medicine.ox.ac.uk/bandolier) provides a summary service that covers selected medical topics. Information comes from systematic reviews, meta-analyses, randomised trials and high quality observational studies. The review of the clinical evidence is combined with a clinical commentary and a clinical bottom line. Bandolier's internet version is free of charge.

Several journals also have sections where they highlight critically appraised papers. They generally use similar principles and format to ACP Journal Club. Examples in the allied health professions are the Journal of Physiotherapy, Australian Occupational Therapy Journal and the Canadian Association of Occupational Therapists' OT Now publication.

A list of resources with hotlinks to pre-appraised resource journals (synopses) for various disciplines is maintained by The New York Academy of Medicine (www.nyam.org/fellows-members/ebhc/eb_publications.html).

Syntheses (systematic reviews)—fourth layer of the pyramid

When no synopses of syntheses can be found, the next best place to look for an answer to your clinical question is a systematic review. Systematic reviews provide syntheses of the highest quality evidence available for a specific clinical question. Information about how to appraise systematic reviews is presented in Chapter 12 of this book. Systematic reviews can be found in the following resources:

• Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (www.thecochranelibrary.com) is part of the Cochrane Library and is made up of several review groups that concentrate and synthesise the evidence in specific healthcare areas. For example, the focus of the Cochrane Musculoskeletal Group is synthesising the evidence from randomised controlled trials and controlled clinical trials of interventions that are concerned with the prevention, treatment and/or rehabilitation of musculoskeletal disorders.

The focus of the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews was originally on healthcare interventions. However, from Issue 1, 2008, reviews on diagnostic test accuracy were introduced. At the time of writing (March 2012), there were over 7200 records available and most of these were completed reviews. Even with this many systematic reviews available, the Cochrane Collaboration contains less than a quarter of the world's supply of systematic reviews.

The Cochrane Library, which houses the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, is a subscription-based resource that is usually available in academic or hospital environments where institutional subscriptions exist. However, residents in a number of countries or regions can access The Cochrane Library online for free (for a list visit www.thecochranelibrary.com/view/0/FreeAccess.html). Cochrane systematic reviews are indexed in several large biomedical electronic databases such as MEDLINE, and are therefore also available through other vendors such as Ovid on a subscription basis and through PubMed (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?db=pubmed), which is free.

There are a number of ways to search in the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, such as Quick Search, Advanced Search and MeSH search (see Box 3.1 for an explanation of MeSH). As the Cochrane Library is such an important evidence-based practice resource, it is important that you know how to search in it efficiently. We highly recommend that you read the easy-to-read Cochrane Library User Guide (available for free at www.cochrane.org.au/libraryguide).

Cochrane reviews are updated regularly, and previous versions of a review are archived on the Cochrane Library website under the ‘Other versions’ tab available on the article display page. Older versions of the review can only be retrieved via the ‘Other versions’ tab as they are not picked up by a Cochrane Library search. The Cochrane Library also includes DARE content.

• Campbell Collaboration (www.campbellcollaboration.org) conducts and maintains systematic reviews about the effects of interventions in the social, behavioural and educational arenas (for example social skills training). As of March 2012, the free searchable database contained more than 200 systematic reviews.

• Various biomedical databases—many systematic reviews are available in the large electronic biomedical databases such as MEDLINE and EMBASE. These databases are available through various providers such as Ovid (gateway.ovid.com) on a subscription basis. MEDLINE is also available free of charge through PubMed.

It can be challenging to efficiently retrieve systematic reviews from these large databases because of the sheer volume of articles that they contain and because they also contain many other types of articles that are not useful for answering clinical questions. To assist with the retrieval of systematic reviews, researchers have developed search filters for use in these large databases. The ‘Clinical Queries’ screen in PubMed (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/clinical or accessed by a link on the PubMed homepage) offers some assistance to efficient searching by providing a ready-to-use search filter for identifying systematic reviews. This feature is described in more detail later in this chapter when MEDLINE is discussed further.

• Discipline-specific databases—there are several discipline-specific databases which contain systematic reviews or index systematic reviews. For example:

• health-evidence.ca (www.health-evidence.ca) is a free, searchable online registry of public health systematic reviews.

• EvidenceUpdates (http://plus.mcmaster.ca/EvidenceUpdates) is a freely available resource. EvidenceUpdates is described in more detail in the following section on studies.

• OBESITY+ (http://plus.mcmaster.ca/obesity/Default.aspx) provides access to a subset of the content found in EvidenceUpdates. The content focuses on obesity. OBESITY+ is described in more detail in the following section on studies.

• REHAB+ (http://plus.mcmaster.ca/rehab/Default.aspx) provides access to the current best evidence about the causes, course, diagnosis, prevention, treatment and economics related to rehabilitation. REHAB+ is described in more detail in the following section on studies.

• Nursing+ (http://plus.mcmaster.ca/NP) provides access to the current best evidence about the causes, course, diagnosis, prevention, treatment and economics related to nursing care. Nursing+ is described in more detail in the following section on studies.

• OTseeker (Occupational Therapy Systematic Evaluation of Evidence) is an occupational therapy evidence database and is freely available at www.otseeker.com. OTseeker is described in more detail in the following section on studies.

• PEDro is the Physiotherapy Evidence Database, from the Centre for Evidence-based Physiotherapy in Australia, and is freely available at www.pedro.org.au. PEDro is described in more detail in the following section on studies.

• PsycBITE (the Psychological Database for Brain Impairment Treatment Efficacy) is freely available at www.psycbite.com. PsycBITE is described in more detail in the following section on studies.

• speechBITE (Speech Pathology Database for Best Interventions and Treatment Efficacy) is freely available at www.speechbite.com and is described in more detail in the following section on studies.

• The Joanna Briggs Institute provides a library of systematic reviews that is available on a subscription basis (http://connect.jbiconnectplus.org). It contains reviews that are primarily of relevance to nursing.

Synopses of studies—fifth layer of the pyramid

When no syntheses can be found, the next best place to look for an answer to your clinical question is synopses of studies. Synopses of studies are structured abstracts or brief overviews of published individual studies that have been screened for methodological rigour. This means you do not have to do this step yourself. Synopses of studies are found in evidence-based abstraction journals, that is ACP Journal Club (www.acpjc.org), Evidence-Based Nursing (http://ebn.bmj.com), Evidence-Based Medicine (http://ebm.bmj.com) and Evidence-Based Mental Health (http://ebmh.bmj.com), as described in the section on synopses of syntheses.

Studies—sixth layer (bottom) of the pyramid

When none of the upper layers of the pyramid provide an answer to your clinical question, you must look for individual studies. There are millions of individual studies, which can make it difficult for you to efficiently find the evidence that you need to answer your clinical question. When searching for individual studies, you should start your search using databases that have screened many sources for you, include only the most important clinical studies and have pre-appraised the studies for you. Examples are:

• EvidenceUpdates (plus.mcmaster.ca/EvidenceUpdates) provides access to scientifically sound and clinically relevant systematic reviews and studies that have been published in over 120 premier healthcare journals. The content found in these 120 journals is critically appraised by research staff, and those studies and reviews that are scientifically sound are then rated for relevancy and newsworthiness by a worldwide panel of practising doctors. The content focuses on internal medicine and its subspecialties, general medical practice and nursing. Various types of articles are included, such as those concerned with therapy, diagnosis, prognosis, aetiology, quality improvement and continuing education, economics, clinical prediction guides and differential diagnosis. A searchable database is available for use after registering for this free service.

The following three databases are subsets of the content found in EvidenceUpdates. Their content is rated for relevancy and newsworthiness by a worldwide panel of practising health professionals who have a special interest in the area of interest of each database (for example, practising occupational therapists and physiotherapists provide the ratings for REHAB+). These databases are free to search after completing a quick registration process.

• OBESITY+ (http://plus.mcmaster.ca/obesity/Default.aspx) provides access to the current best evidence about the causes, course, diagnosis, prevention, treatment and economics of obesity and its related metabolic and mechanical complications.

• REHAB+ (http://plus.mcmaster.ca/rehab/Default.aspx) provides access to the current best evidence about the causes, course, diagnosis, prevention, treatment and economics related to rehabilitation.

• Nursing+ (http://plus.mcmaster.ca/NP) provides access to the current best evidence about the causes, course, diagnosis, prevention, treatment and economics related to nursing care.

• Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials is part of the Cochrane Library and is the largest electronic registry of randomised controlled trials in existence (in September 2012, there were over 680,000 records). It is available as part of a subscription to the Cochrane Library and is also available through Ovid's Evidence-Based Medicine Reviews, which are packages of databases available on a subscription basis, as well as through several other services such as Wiley Interscience. This registry of individual controlled trials is a companion database to the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, which was described earlier in the chapter. The articles in this registry are sourced from large databases including MEDLINE and EMBASE, hand-searches of major healthcare journals across many health disciplines and other sources that are utilised by the review groups within the Cochrane Collaboration.

• OTseeker (www.otseeker.com) is a discipline-specific database that contains abstracts of systematic reviews and randomised controlled trials relevant to occupational therapy (over 9000 as of November 2012). The trials included in this database have been critically appraised and rated to help you interpret the results and assess the validity of the findings. OTseeker is available free of charge.

• PEDro (www.pedro.org.au) is a discipline-specific database that contains abstracts of randomised controlled trials, systematic reviews and evidence-based clinical practice guidelines relevant to physiotherapy (over 22,000 as of November 2012). As with the articles on OTseeker, most trials in the database have been critically appraised and this assessment helps you to discriminate between trials which are likely to be valid and interpretable and those which are not. PEDro is available free of charge.

• PsycBITE (www.psycbite.com) catalogues studies (randomised and non-randomised controlled trials, case series and single subject design) and systematic reviews focusing on the cognitive, behavioural and other types of treatment for the psychological problems and issues that can occur as a result of acquired brain impairment. The methodological quality of most of the randomised trials, non-randomised controlled trials and case series has been rated.

• speechBITE (www.speechbite.com) is modelled on PsycBITE and contains treatment studies (systematic reviews, randomised and non-randomised controlled trials, case series and single subject design) across the scope of speech pathology practice. The randomised and non-randomised controlled trials have been critically appraised.

If you cannot find an answer to your clinical question using a pre-appraised service such as those outlined above, the next step is to use one or more of the large electronic bibliographic databases that are described in this section. When searching in the large electronic databases, it is often most effective if you search using a combination of index terms and textwords. These are explained in Box 3.1.

• MEDLINE is the largest biomedical database and currently has over 21 million citations. MEDLINE is produced by the US National Library of Medicine and is available for free through PubMed (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?db=pubmed). Searching efficiently in MEDLINE is important because of the large size of the database and also because many of the articles included in the database are not appropriate for use in evidence-based practice (for example literature reviews). MEDLINE is also available through providers, such as Ovid, on a subscription basis. When accessing MEDLINE via Ovid, content searches can also be limited by Clinical Queries for individual studies about therapy, diagnosis, prognosis, aetiology, clinical prediction guides, costs, economics and studies of a qualitative nature, as well as systematic reviews.

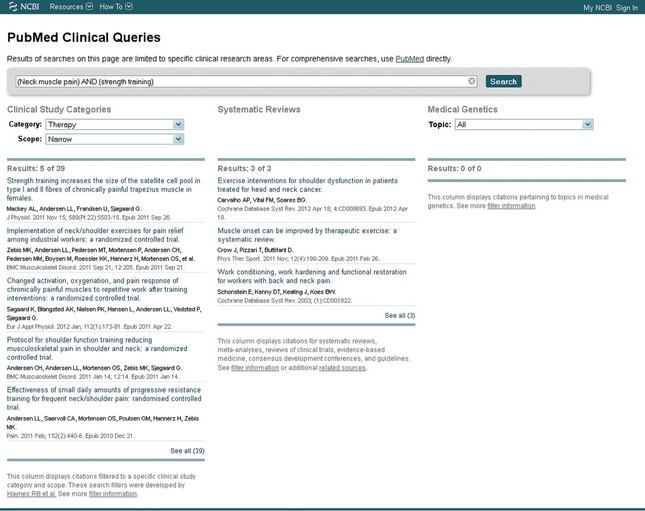

• As mentioned previously in this chapter, the Clinical Queries screen in PubMed (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/clinical) can be a great tool to facilitate efficient clinical searching by providing ready-to-use search filters. These search strategies filter the retrieval of appropriate study types for the clinical categories of therapy, diagnosis, aetiology, prognosis and clinical prediction. For example, when searching for an article about therapy, the search filter attempts to restrict the retrieval to articles that report using a randomised controlled trial design.

• Search strategies that filter the retrieval of appropriate study types for the clinical categories of healthcare costs and healthcare quality (and some qualitative topics) can be found on the Health Services Research Queries screen (www.nlm.nih.gov/nichsr/hedges/search.html) after clicking on the Special Queries link in PubMed.

When using the Clinical Queries or Health Services Research Queries interfaces, you only need to:

1. Enter basic content information (such as the keywords from your clinical question—try starting with the ‘P’ and ‘I’ keywords and then broaden or narrow your search as needed) and click on ‘Search’.

2. Then, select the type of question that you are searching for an answer to (in Clinical Queries, you can choose from therapy, prognosis, diagnosis, aetiology or clinical prediction guides).

3. Decide if you want to conduct a broad (sensitive) or narrow (specific) search:

a. A sensitive (broad) search increases the likelihood of retrieving every possible relevant study, which in PubMed can often result in an unmanageable number of search results.

b. You may wish to begin by selecting a specific (narrow) search, which will minimise the number of irrelevant studies that are returned. If you get very few, or no, search results, you can then repeat the search and change the emphasis to sensitive.

That is all you have to do. Everything else, such as the methodological refining of the search filter, is done for you. The results will be presented in two columns: one containing primary studies (called ‘clinical studies’ by PubMed) and one containing systematic reviews (sometimes there can be some inaccuracies in this, with systematic reviews appearing in the primary study list and non-systematic reviews appearing in the systematic reviews list). There is also a third column called ‘Medical Genetics’, but the results in this column are unlikely to be of use for health professionals who are trying to answer a clinical question. A useful feature of Clinical Queries is that it also searches using the relevant MeSH terms (without you having to select them). Another handy feature of PubMed is the Related Citations feature—a list of related articles (as the name aptly suggests!) that appears on the right-hand margin of the search results screen. This can be a quick and easy way to locate some additional articles that are relevant to your search, or at least, some related terms to search with.

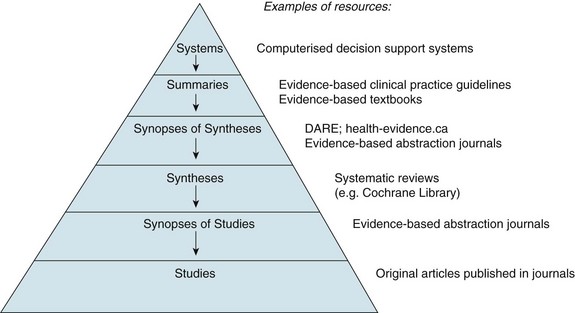

Figure 3.2 shows the search page of Clinical Queries and a basic search related to the clinical scenario that was outlined earlier in this chapter. Details of the search that Clinical Queries actually ran for you are shown in the ‘search details’ box on the right-hand side of the full search results page (once you click on ‘see all’ at the bottom of the first search results page that is displayed). In the example search that is shown in Figure 3.2, even though we only typed in (Neck muscle pain) AND (strength training), this is what was actually searched for:

Figure 3.2 The Clinical Queries search page in PubMed. Reproduced courtesy of National Center for Biotechnology Information/U.S. National Library of Medicine.

Other large databases are:

• EMBASE is a large European database with over 20 million citations. EMBASE is similar to MEDLINE in scope and content, with an overlap in content between the two databases of about 30–50%. Compared with MEDLINE, EMBASE provides greater coverage of European and non-English-language publications and a broader coverage of topics concerned with pharmaceuticals, psychiatry, toxicology and alternative medicine. EMBASE is available through various providers, such as Ovid, on a subscription basis. Your hospital or academic institution library may have an institutional subscription to this resource. As in Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid EMBASE content searches can be limited by Clinical Queries for individual studies about therapy, diagnosis, prognosis, aetiology, economics and studies of a qualitative nature, as well as systematic reviews.

• CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature) is the premier nursing and allied health database, and contains over 2.3 million records. CINAHL is offered by the vendor EBSCOHost. As in Ovid MEDLINE and Ovid EMBASE, EBSCO CINAHL offers content searches that can be limited by Clinical Queries for individual studies about therapy, prognosis, aetiology and studies of a qualitative nature, as well as systematic reviews.

• PsycINFO is the comprehensive international bibliographic database of psychological literature from the 1800s to the present, and contains over 3 million records. As with the other large databases, multiple access routes are available and all require a subscription. In Ovid PsycINFO, Clinical Queries can be used to limit retrieval to individual studies about therapy and those of a qualitative nature, as well as systematic reviews.

When searching using the large electronic databases, it is important to use the help function that is found within each database so that you become familiar with how to search the database efficiently. The features and interfaces of databases change from time to time and, as mentioned earlier, there are some subtle differences across databases in terms of refining search techniques, such as the symbols for truncation and the use of double quotation marks instead of parentheses for combining terms.

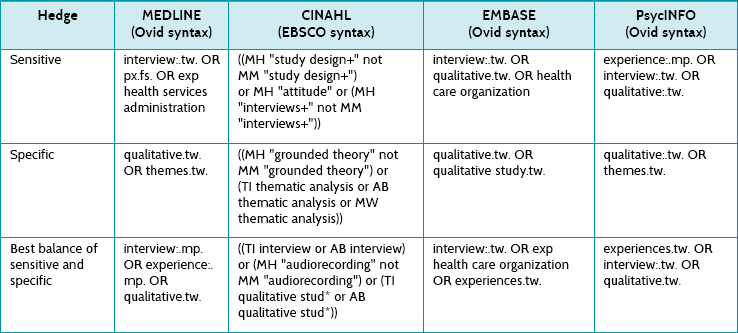

Some tips for locating qualitative research

Finding qualitative research can be very difficult. One of the reasons is that it is indexed in a number of different ways. Using the term ‘qualitative’ as a search term is often not useful, as sometimes qualitative research is indexed by the specific method that was used to collect data (for example, focus group or in-depth interview) and other times it is indexed according to the methodology that was used (for example, phenomenology or grounded theory). Table 3.1 shows some empirically derived10–13 search filters that can be used to locate qualitative studies in CINAHL, MEDLINE, EMBASE and PsycINFO. They are methodological search filters, meaning that they focus on the methods of qualitative research rather than the content. Combine these methodological search filters with your content terms, that is the keywords from your clinical question.

TABLE 3.1:

Search filters for locating qualitative research in MEDLINE, CINAHL, EMBASE and PsycINFO

Ovid syntax: colon (:) = truncation; exp = explosion; fs = floating subheading; mp = multiple posting, term found in title, abstract or index terms; px = psychology; tw = textword.

EBSCO syntax: + = explode; AB = abstract; MH = subject heading; MM = exact major subject heading; MW = subject heading word; TI = title.

For example, to locate qualitative research about depression in women, you could try the following search string in Ovid MEDLINE:

The search filters shown in Table 3.1, except for the CINAHL filter, are in Ovid syntax (that is, Ovid language) so they will need translation if you are searching using another interface. The CINAHL filter provided is in EBSCO syntax, as CINAHL has only been available through this provider since 2009. The PubMed translation of the MEDLINE sensitive and specific search can be found on the Special Queries page of PubMed under Health Services Research Queries, which we described earlier in this chapter when MEDLINE was explained. As you can see in Table 3.1, there is a choice of three different search filters—‘sensitive’, ‘specific’ or ‘best balance of sensitive and specific’.

• Use the sensitive search filter when you want a very broad search and do not want to risk missing any relevant articles.

• Use the specific search filter when you want to narrow your search and want to find just a few relevant articles.

• Use the ‘best balance’ search filters for a search that provides a good balance between sensitivity and specificity.

Alerting or updating services

Although it is not on the ‘6S’ pyramid specifically, electronic communication (that is, email) can be a useful method of informing health professionals about newly published studies. Unlike all of the resources outlined above that require you to go and search for the evidence, alerting services bring the research literature to you in the form of email alerts or RSS (really simple syndication) feeds, which are simply a list of items that you sign up to receive. In Chapter 2, this was described as ‘push’ or ‘just-in-case’ information. Several alerting systems that target articles to individual health professionals have been developed. Some examples are:

• EvidenceUpdates (plus.mcmaster.ca/EvidenceUpdates) is a free service that alerts health professionals to newly published studies and systematic reviews from over 120 premier healthcare journals that are published in their discipline. It is the same process that the ACP Journal Club uses to select both clinically relevant and methodologically rigorous papers. If a paper is going to be clinically useful, it has a high probability of being selected in this database. Newly published studies and systematic reviews have been pre-appraised for methodological rigour, and clinical relevancy and newsworthiness. Users choose the frequency at which they wish to receive email notifications or RSS feeds and the disciplines in which they are interested (for example: general medicine practice, endocrinology) and set the score level for clinical relevance and newsworthiness to a level that is acceptable to them.

• OBESITY+ (plus.mcmaster.ca/obesity/Default.aspx) offers a free alerting service that provides access to a subset of the content found in EvidenceUpdates. The content of OBESITY+ was described earlier in this chapter.

• REHAB+ (plus.mcmaster.ca/rehab/Default.aspx) offers a free alerting service that provides access to a subset of the content found in EvidenceUpdates that is relevant to rehabilitation.

• Nursing+ (plus.mcmaster.ca/NP) provides access to the current best evidence about the causes, course, diagnosis, prevention, treatment and economics related to nursing care and also has a free alerting service.

• My NCBI (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/myncbi) is an alerting service within PubMed that will email users with new citations from MEDLINE in the clinical areas that they have specified. Users set up a search that will automatically email them citations of newly published articles based on content (for example, asthma in adolescents) or journal titles. My NCBI is offered free of charge through PubMed. However, the newly published articles are not filtered by methodological rigour and you will need to critically appraise the articles that are sent to you before considering their use in clinical practice.

• Journals may enable you to register to have the table of contents emailed to you as each new issue of the journal is published. You may wish to do this for journals that you frequently consult. As with My NCBI, the newly published articles are not filtered by methodological rigour and you will need to critically appraise the articles that are sent to you before considering their use in clinical practice.

Other resources

Again, although not specifically on the ‘6S’ pyramid, many search engines are available for use on the internet. When using these search engines (for example Google), you are not searching a defined database but are searching the internet in general. A major negative aspect of using these search engines is that evidence-based information may be difficult to find and much high quality clinical research (such as that located in databases) cannot be located at all in this way. On the other hand, positive aspects are that an internet search can be a quick way of tracking down a specific article and obtaining information about issues that keep changing, such as listings of country-specific vaccination rules for travellers. Examples of internet search engines are:

• Google (www.google.com), Yahoo (www.yahoo.com), MSN (www.msn.com) and Ask (www.ask.com). All four internet search engines are commonly used and freely accessible. Search Engine Watch (searchenginewatch.com/article/2048976/Major-Search-Engines-and-Directories) maintains a list of major search engines on the web and rates the usefulness of each. Note that when searching using Google, truncations or wild cards for letters of the alphabet are not an option. In Google, the use of wild cards is for words rather than letters. For example, typing personal * records would retrieve items that include personal health records, personal medical records, personal records, etc.

• Google Scholar (scholar.google.com) is a free service provided by Google that provides searching of the scholarly literature. From one site, you are able to search across many disciplines and sources such as peer-reviewed papers, theses, books, abstracts and articles that are from academic publishers, professional societies, preprint repositories, universities and other scholarly organisations. Google Scholar sorts articles by weighting the full text of the article, the author, the publication in which the article appears and how often the article has been cited in other scholarly literature. This sorting results in the most relevant articles being likely to appear on the first page.

• Search engines that retrieve and combine results from multiple search engines (meta-search engines) also exist.

Finally, you may be faced with a clinical question where you do not know which of the evidence-based resources may be best for answering your particular clinical problem. In these situations, ‘federated search engines’ provide a means to search many resources, with the retrieval of results organised according to the source of evidence. Examples are:

• ACCESSSS (plus.mcmaster.ca/accessss) is a free health-related meta-search engine that searches multiple databases with just one entry of your search term(s). ACCESSSS is designed to find the best evidence-based answer to your clinical questions by simultaneously searching the leading evidence-driven medical publications and high quality clinical literature. As of September 2011, sources included in ACCESSSS searches included DynaMed, UpToDate, STAT!Ref PIER, Best Practice, DARE, McMaster Premium Literature Service (PLUS), ACP Journal Club, PubMed Clinical Queries and PubMed. ACCESSSS searches and groups the results according to the ‘6S’ pyramid. ACCESSSS is a product of the McMaster Health Knowledge Refinery (http://hiru.mcmaster.ca/hiru) which is a continuously updated resource for evidence-based clinical decisions. After registering for the service, alerts to new evidence tailored to your clinical/research needs are provided, as well as links to prescribing and patient information.

• SUMSearch 2 (sumsearch.org) is a free health-related meta-search engine that simultaneously searches for original studies, systematic reviews and practice guidelines from multiple sources. You can focus (for example, intervention) and limit (for example, age) your search. By using SUMSearch 2, you can search multiple medical databases with one entry of search terms. For example, the entry of two words, ‘spinal manipulation’ in SUMSearch 2 provided links to 19 guidelines that are available through the US National Guidelines Clearinghouse, 4 guidelines in PubMed, 231 systematic reviews in PubMed and 51 original studies in PubMed. By contrast, when an internet search engine such as Google (www.google.com) was used to perform this search, it retrieved approximately 2.8 million entries for ‘spinal manipulation’ and the items were not grouped by source (for example PubMed) or type of evidence (for example systematic reviews).

• TRIP (Turning Research Into Practice, www.tripdatabase.com) is similar to SUMSearch 2 in that it searches multiple databases and other evidence-based resources with just one entry of your search term(s). TRIP groups the search results into evidence-based synopses, systematic reviews, guidelines (from Australia and New Zealand, Canada, UK, USA and other locations), clinical questions and answers, core primary research, e-textbooks and more. Any articles that are retrieved from MEDLINE are organised by purpose—therapy, diagnosis, systematic review, prognosis and aetiology. You can register for My TRIP and obtain access to extra features including alerts to new evidence.

Search examples

In this section we will use some of the resources described in this chapter to answer several different clinical questions—one from each of the four major question types that are covered in this book (effects of intervention, diagnosis, prognosis, and questions about patients' experiences and concerns).

Clinical question about the effects of intervention

You are a physiotherapist and currently have two patients who are pregnant and experiencing pelvic and back pain. You wonder:

Starting at the top of the ‘6S’ pyramid, you confirm that there is nothing at the top three levels of the pyramid, which is often the case for allied health clinical questions. As your question is one about intervention effectiveness, you are ideally hoping to find a systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Therefore, your next step is to look for a systematic review (fourth level of the pyramid—syntheses) by searching in the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, using the keywords from your clinical question (pregnan* AND acupuncture).

Your search retrieves one review14 that summarises interventions for preventing and treating pelvic and back pain in pregnancy. As all but one study included in the review had moderate to high potential for bias (as stated by the authors of the review), you decide to look for other systematic reviews, ideally ones where acupuncture was the only intervention of focus.

Since PEDro contains systematic reviews and pre-appraised articles related to physiotherapy, you decide to search there next. On the advanced search page, you type in the terms ‘pregnancy acupuncture’, and select the body part ‘lumbar spine, sacro-iliac joint and pelvis’. Note that in PEDro you do not need to type in Boolean operators; just tick the box at the bottom of the advanced search page indicating whether you want the search terms to be combined with AND or OR. Your search retrieves 13 records, and three of these are systematic reviews. One was the Cochrane review that you had already found. One focuses on transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) for pain relief with labour. The third review is a systematic review of acupuncture for pelvic and back pain in pregnancy,15 which appears to be exactly what you are after.

Note that during this search you try the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews and the relevant discipline-specific database (PEDro in this case) before trying the large electronic databases such as MEDLINE, as it is typically much more efficient to locate evidence about an intervention question in these databases than in the large electronic databases.

Clinical question about diagnosis

You are an occupational therapist who works in a community health centre. The team that you work in is putting together an initial assessment form for newly referred patients, and they wish to include some screening questions that will provide useful information to various members of the team. You are interested in including a brief cognitive screening test, such as the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), as part of this initial assessment but wonder how accurate this test is at predicting cognitive impairment in older people who live in the community. Your question is:

After confirming that there is nothing available at the top three levels of the pyramid, you proceed to the fourth level of the pyramid (syntheses). You conduct a search in the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, but no search results are returned. Since the Cochrane database only recently started adding diagnostic reviews, you are not surprised that no relevant reviews are retrieved.

You then search using PubMed Clinical Queries (with ‘diagnosis’ selected as the category and a narrow search chosen) with the terms:

This produces 109 hits, which you decide is too many to look through. You add the word ‘community’ to your search string and this produces 30 articles, three of which are exactly what you are after.16–18

Clinical question about prognosis

You are a recently graduated speech pathologist who has just commenced working in a stroke rehabilitation unit. One of your patients is 2 months post-stroke and has severe dysphagia (difficulty swallowing). His wife asks you how likely it is that his swallowing will get better in the next few months and that he will be able to return to eating a normal diet. As you are new to this area of clinical practice and have little clinical experience to guide your answer, you form the following clinical question:

You search using PubMed Clinical Queries (with prognosis selected as the clinical category and a narrow search chosen) with the terms:

This produces 23 hits, two of which are exactly what you are after.19,20

Clinical question about patients' experiences and concerns

You are a dietitian working with children who are obese. The children are having a very difficult time losing weight. You wonder why it is that children who are obese often find it so difficult to lose weight when the lifestyle factors that contribute to the condition are so widely recognised. Your question is:

This question would best be answered by a qualitative research design. Currently, qualitative studies are most likely found on the bottom layer of the pyramid: studies. You start your search using CINAHL (through EBSCOhost), as this can be a useful database to search when looking for qualitative research. You search using the search string:

choosing the ‘TX All Text’ searching field. You also limit the search by using the Clinical Queries feature of CINAHL and select ‘qualitative—best balance’ as you only want to retrieve qualitative articles.

Your search produces 11 hits, one of which is directly on target.21 You notice that one of the other hits is also very relevant, but when you look at the abstract of it you realise that it is actually a synopsis22 of the original article that has been published in Evidence-Based Nursing, which is a synopsis journal—located on the third and fifth layer of the pyramid (synopses of syntheses and synopses of studies). This is great news for you, as it means that this original article has been pre-appraised for you and considered to be clinically important and that the synopsis will also contain a clinical bottom line that has been written by a clinical expert in this field!

Another approach for this search would be to use PubMed, using the Health Services Research Queries feature (accessed by clicking on the ‘Topic-Specific Queries’ link on the main PubMed page followed by the ‘Health Services Research [HSR] Queries’ link) that was described earlier in this chapter. One of the categories for searching on this page is qualitative research. You choose this category and ‘Narrow, specific search’ for the scope, and enter the same search terms as we used above in CINAHL. The search retrieves 13 citations. The eleventh article on the list of search results is the same primary article21 that you found using CINAHL.

References

1. Ely, J, Osheroff, J, Ebell, M, et al. Obstacles to answering doctor's questions about patient care with evidence: qualitative study. BMJ. 2002; 324:710–716.

2. DiCenso, A, Bayley, L, Haynes, RB. Assessing preappraised evidence: fine-tuning the 5S model into a 6S model. Ann Intern Med. 2009; 151:JC3-2–3.

3. Roshanov, P, Misra, S, Gertein, H, et al. Computerised clinical decision support systems for chronic disease management: a decision-maker–researcher partnership systematic review. Implement Sci. 2011; 6:92.

4. Sahota, N, Lloyd, R, Ramakrishna, A, et al. Computerised clinical decision support systems for acute care management: a decision-maker–researcher partnership systematic review of effects of process of care and patient outcomes. Implement Sci. 2011; 6:91.

5. Nieuwlatt, R, Connolly, S, MacKay, J, et al. Computerised clinical decision support systems for therapeutic drug monitoring and dosing: a decision-maker–researcher partnership systematic review. Implement Sci. 2011; 6:90.

6. Hemens, BJ, Holbrook, A, Tonkin, M, et al. Computerised clinical decision support systems for drug prescribing and management: a decision-maker–researcher partnership systematic review. Implement Sci. 2011; 6:89.

7. Roshanov, P, You, J, Dhaliwal, J, et al. Can computerised clinical decision support systems improve practitioners’ diagnostic test ordering? A decision-maker–researcher partnership systematic review. Implement Sci. 2011; 6:88.

8. Souza, N, Sebaldt, R, Mackay, J, et al. Computerised clinical decision support systems for primary preventive care: a decision-maker–researcher partnership systematic review of effects on process of care and patient outcomes. Implement Sci. 2011; 6:89.

9. Montori, VM. Evidence-based endocrinology. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 2005.

10. Wong, S, Wilczynski, N, Haynes, RB, et al. Developing optimal search strategies for detecting clinically relevant qualitative studies in MEDLINE. Medinfo. 2004; 11:311–316.

11. Wilczynski, N, Marks, S, Haynes, RB. Search strategies for identifying qualitative studies in CINAHL. Qual Health Res. 2007; 17:705–710.

12. Walters, L, Wilczynski, N, Haynes, RB, et al. Developing optimal search strategies for retrieving clinically relevant qualitative studies in EMBASE. Qual Health Res. 2006; 16:162–168.

13. McKibbon, KA, Wilczynski, N, Haynes, RB. Developing optimal search strategies for retrieving qualitative studies in PsycINFO. Eval Health Prof. 2006; 29:440–454.

14. Pennick, VE, Young, G. Interventions for treating and preventing pelvic and back pain in pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2, 2007. [CD001139. doi: 10.1002/14651858. CD001139.pub2].

15. Ee, C, Manheimer, E, Pirotta, M, et al. Acupuncture for pelvic and back pain in pregnancy: a systematic review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008; 198:254–259.

16. Gagnon, M, Letenneur, L, Dartigues, J, et al. Validity of the Mini-Mental State examination as a screening instrument for cognitive impairment and dementia in French elderly community residents. Neuroepidemiology. 1990; 9:143–150.

17. Loewenstein, D, Barker, W, Harwood, D, et al. Utility of a modified Mini-Mental State Examination with extended delayed recall in screening for mild cognitive impairment and dementia among community dwelling elders. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2000; 15:434–440.

18. Scazufca, M, Almeida, O, Vallada, H, et al. Limitations of the Mini-Mental State Examination for screening dementia in a community with low socioeconomic status: results from the Sao Paulo Ageing & Health Study. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2009; 259:8–15.

19. Mann, G, Hankey, G, Cameron, D. Swallowing function after stroke: prognosis and prognostic factors at 6 months. Stroke. 1999; 30:744–748.

20. Han, T, Paik, N, Park, J, et al. The prediction of persistent dysphagia beyond six months after stroke. Dysphagia. 2008; 23:59–64.

21. Murtagh, J, Dixey, R, Rudolf, M. A qualitative investigation into the levers and barriers to weight loss in children: opinions of obese children. Arch Dis Child. 2006; 91:920–923.

22. Macdonald, M. Clinically obese children identified facilitators and barriers to initiating and maintaining the behaviours required for weight loss. Evid Based Nurs. 2007; 10:92.