Implementing evidence into practice

After reading this chapter, you should be able to:

• Describe the process of transferring evidence into practice

• Explain what is meant by an evidence–practice gap and describe methods that can be used to demonstrate an evidence-based gap

• Explain various types of barriers to successfully implementing evidence and how barriers and enablers can be identified

• Describe strategies and interventions that can be used to facilitate the implementation of evidence

• Describe theories which can inform the development of implementation strategies and help explain behaviour change as it relates to the implementation of evidence

As we have seen throughout this book, searching for and appraising research articles are key components of evidence-based practice. However, while they are worthy activities, on their own they do not change patient outcomes. To improve outcomes, health professionals need to do more than read the evidence. Transferring the evidence into practice is also required. Professionals need to translate research that has proven value, for example evidence from evidence-based clinical guidelines, systematic reviews and high quality randomised controlled trials. Findings from research projects which have involved years of hard work, many participants and often substantial costs should not remain hidden in journals. Translating or implementing evidence into practice is the final step in the process of evidence-based practice, but it is often the most challenging step.

Implementation is a complex but active process which involves individuals, teams, systems and organisations. Translating evidence into practice requires careful forward planning.1 While some planning usually does occur, the process is often intuitive.2 There may be little consideration of potential problems and barriers. As a consequence, the results may be disappointing. To help increase the likelihood of success when implementing evidence, this chapter provides a checklist for individuals and teams to use when planning the implementation of evidence.

In this chapter, definitions of implementation ‘jargon’ are provided, followed by examples of evidence that different disciplines have applied in practice. A description is provided of the steps that health professionals follow when translating evidence into practice. Steps include collecting and analysing local data (gap analysis) and identifying possible barriers and enablers to change. Barriers might include negative attitudes, limited skills and knowledge, or limited access to medical records and equipment. A menu of implementation strategies is presented, along with a review of the evidence for the effectiveness of these strategies. Finally, theories which can help us predict and explain individual and group behaviour change are considered.

Implementation terminology

A number of confusing terms appear in the implementation literature. Different terms may mean the same thing in different countries. To help you navigate this new terminology, definitions relevant to the chapter are provided in Box 16.1.

Implementation case studies

To help you understand the process of implementation, we now consider three case studies. The first case study involves reducing referrals for a test procedure (X-rays) by general practitioners for people who present with acute low back pain.7 This case example involves the overuse of X-rays. The other two case studies involve increasing the uptake of two under-used interventions: cognitive–behavioural therapy for adolescents with depression,8 and community travel and mobility training for people with stroke.9,10

Case study 1. Reducing the use of X-rays by general practitioners for people with acute low-back pain

Low back pain is one of the most common musculoskeletal conditions seen not only by general practitioners,11 but also by allied health practitioners such as physiotherapists, chiropractors and osteopaths. Clinical guidelines released in Australia in mid-2005 recommend that people presenting with an episode of acute non-specific low back pain should not be sent for an X-ray because of the limited diagnostic value of this test for this condition.12 In Australia, about 25% of people who visited their local general practitioner with acute low back pain between 2005 and 2008 were referred for an X-ray13 after release of the guidelines. Even higher proportions are reported in the United States and Europe.7 Put simply, X-rays are over-prescribed and costly. Instead of recommending an X-ray, rest and passive interventions, general practitioners should advise people with acute low back pain to remain active.12

In this instance, the evidence–practice gap is the overuse of a costly diagnostic test which can delay recovery. Recommendations about the management of acute low back pain, including the use of X-rays, have been made through the national clinical guidelines.12 A program to change practice, in line with guideline recommendations, is the focus of one implementation study in Australia7 and will be discussed further throughout this chapter.

Case study 2. Increasing the delivery of cognitive–behavioural therapy to adolescents with depression by community mental health professionals

Cognitive–behavioural therapy has been identified as an effective intervention for adolescents with depression, a condition that is on the increase in developed countries.14 Outcomes from cognitive–behavioural therapy that is provided in the community are superior to usual care for this population.15 Clinical guidelines recommend that young people who are affected by depression should receive a series of cognitive–behavioural therapy sessions. However, a survey of one group of health professionals in North America found that two-thirds had no formal training in cognitive–behavioural therapy, and no prior experience using an intervention manual for cognitive–behavioural therapy.8 In other words, they were unlikely to deliver cognitive–behavioural therapy if they did not know much about it. Furthermore, almost half of the participants in that study reported that they never or rarely used evidence-based interventions for youths with depression, and a quarter of the group had no plans to use evidence-based intervention in the following 6 months. Subsequently, that group of mental health professionals was targeted with an implementation program to increase the uptake of the underused cognitive–behavioural therapy. The randomised controlled trial that describes this implementation program8 and the evidence–practice gap (underuse of cognitive–behavioural therapy) will also be discussed throughout this chapter.

Case study 3. Increasing the delivery of travel and mobility training by community rehabilitation therapists to people who have had a stroke

People who have had a stroke typically have difficulty accessing their local community. Many experience social isolation. Approximately 50% of people who complete an on-road driving test after their stroke pass this test and resume driving,16 but many do not return to driving17 and up to 50% experience a fall at home in the first 6 months.18 Australian clinical guidelines recommend that community-dwelling people with stroke should receive up to seven escorted journey sessions and transport information from a rehabilitation therapist, to help increase outdoor journeys.19 Although that recommendation is based on a single randomised controlled trial,20 the size of the intervention effect was large. The intervention doubled the proportion of people with stroke who reported getting out as often as they wanted and doubled the number of monthly outdoor journeys, compared with participants in the control group.20

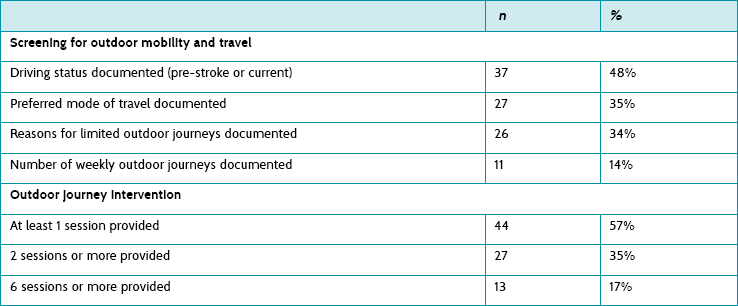

In order to see whether people with stroke were receiving this intervention from community-based rehabilitation teams in a region of Sydney, local therapists and the author of this chapter conducted a retrospective file audit. The audit revealed that therapists were documenting very little about outdoor journeys and transport after stroke. Documented information about the number of weekly outings was present in only 14% of files (see Table 16.1). Furthermore, only 17% of people with stroke were receiving six or more sessions of intervention that targeted outdoor journeys, which was the ‘dose’ of intervention provided in the original trial by Logan and colleagues.20,21 The audit data highlighted an evidence–practice gap, specifically the underuse of an evidence-based intervention. This example will be used as the third case study throughout the chapter, to illustrate the process of implementation.

The process of implementation

The following section summarises two models that may help you better understand the steps and factors involved in implementing evidence.

Model 1. The evidence-to-practice pipeline

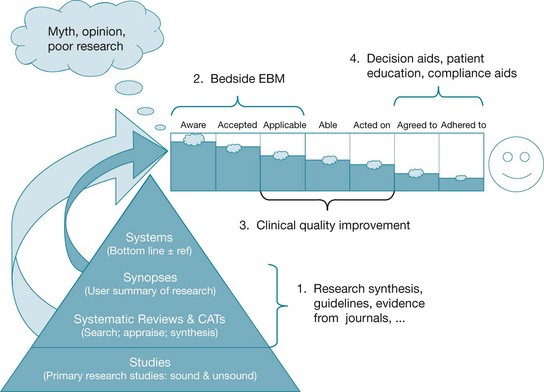

The ‘evidence pipeline’ described by Glasziou and Haynes22 and shown in Figure 16.1 provides a helpful illustration of steps in the implementation process. This metaphorical pipeline highlights how leakage can occur, drip by drip, along the way from awareness of evidence to the point of delivery to patients. First, there is an ever-expanding pool of published research to read, both original and synthesised research. This large volume of information causes busy professionals to miss important, valid evidence (awareness). Then, assuming that they have heard of the benefits of a successful intervention (or the overuse of a test procedure), professionals may need persuasion to change their practice (acceptance). They may be more inclined to provide familiar interventions with which they are confident, and which patients expect and value. Hidden social pressure from patients and other team members can make practice changes less likely to occur. Busy professionals also need to recognise appropriate patients who should receive the intervention (or not receive a test procedure). Professionals then need to apply this knowledge in the course of a working day (applicability).

Figure 16.1 The research-to-practice pipeline. From: Glasziou P, Haynes B. The paths from research to improved health outcomes. ACP Journal Club 2005;22 reproduced with permission from BMJ Publishing Group Ltd.

Some test procedures and interventions will require new skills and knowledge. For example, the delivery of cognitive–behavioural therapy to adolescents with depression involves special training, instruction manuals, extra study and supervision. A lack of skills and knowledge may be a barrier to practice change for professionals who need to deliver the intervention (able). A further challenge is that while we may be aware of an intervention, accept the need to provide it and are able to deliver it, we may not act on the evidence all of the time (acted on). We may forget—or, more likely, we may find it difficult to change well-established habits. For example, general practitioners who have been referring people with acute back pain for an X-ray for many years may find this practice difficult to stop.

The evidence-to-practice pipeline illustrates the steps involved in maximising the acceptance and uptake of research findings. The final two steps rely on patients agreeing to a different test procedure than they expect (agree) and changing their behaviour to comply with an intervention. For example, people with low back pain will need to stay active within the level of comfort permitted by their low back pain (adherence). Any intervention that involves a major change in behaviour, for example exercise or the use of cognitive–behavioural therapy principles, is likely to be difficult for many people to adopt and maintain. These last two steps highlight the important role that shared decision making and clear communication of evidence to patients (which were explained in Chapter 14) have in the process of implementing evidence into practice.

Model 2. Plan and prepare model

A different process of implementation has been proposed by Grol and Wensing.3 Their bottom line is ‘plan and prepare’. While intended for the implementation of clinical guidelines, the principles apply equally well to the implementation of test ordering, outcome measurement or interventions and for procedures that are either underused or overused. The ‘plan and prepare’ model involves five key steps:

1. Write a proposal for change with clear aims and target groups.

2. Analyse the target groups and setting for barriers, problems, enablers and other factors that may hinder or help the change process.

3. Decide on implementation strategies to help professionals learn about, adopt and sustain the practice change.

4. Execute the implementation plan, documenting a list of activities, tasks and a timeline.

5. Evaluate, revise if necessary and continuously monitor the implementation plan, using clinical indicators to measure ongoing success.

Using the travel and mobility study as an example, the two primary aims were:

• to increase the use of the underused intervention by rehabilitation therapists, as recommended by a national guideline recommendation

• to increase community participation, and the number of outdoor journeys, by people with stroke who received the evidence-based intervention.

The two target groups were:

Examples of ‘targets’ or indicators of implementation success were also documented early in this project for both groups.9 The first target was that rehabilitation therapists would deliver an outdoor mobility and travel training intervention20,21 to 75% of people with stroke who were referred to the service (that is, a change in professional behaviour). The second target was that 75% of people with stroke who received the intervention would report getting out of the house as often as they wanted, and take more outdoor journeys per month compared with pre-intervention.

Other steps in the ‘plan and prepare’ model (identifying barriers and enablers, selecting implementation strategies) are discussed, using examples, in the following sections.

Demonstrating an evidence–practice gap (gap analysis)

A common first step is to identify and clarify the research–practice gap which needs to be bridged. Most health professionals who seek funding for an implementation project, and post-graduate students who write research proposals, will demonstrate their evidence–practice gap using simple data collection methods. Surveys and file audits are the most popular methods.

Surveys for gap analysis

A survey can be developed and used, with health professionals or patients, to explore attitudes, knowledge and current practices. If a large proportion of health professionals admit to knowing little about, or rarely using, an evidence-based intervention, this information represents the evidence–practice gap. In the cognitive–behavioural therapy example discussed earlier,8 a local survey was used to explore attitudes to, knowledge of and use of cognitive–behavioural therapy by community mental health professionals.

The process of developing a survey to explore attitudes and behavioural intentions has been well documented in a manual by Jill Francis and colleagues.23 The manual is intended for use by health service researchers who want to predict and understand behaviour, and measure constructs associated with the Theory of Planned Behaviour. Behavioural theories are discussed in a later section of this chapter. If you intend to develop your own local survey or questionnaire, whether the survey is for gap analysis or barrier analysis, it is recommended that you consult this excellent resource (freely available online; see reference 23). Sample questions include: ‘Do you intend to do (intervention X) with all of your patients?’ and ‘Do you believe that you will be able to do X with your patients?’.

Audits for gap analysis

Audit is another method which can be used to demonstrate an evidence–practice gap. A small file audit can be conducted using local data (for example, 10 files may be selected, reflecting consecutive admissions over 3 months). The audit can be used to determine how many people with a health condition received a test or an evidence-based intervention. For example, we could determine the proportion of people with acute back pain for whom an X-ray had been ordered in a general practice over the previous 3 months. We could also count how frequently (or rarely) an intervention was used.

In the travel and mobility study, it was possible to determine the proportion of people with stroke who had received one or more sessions with an occupational therapist or physiotherapist to help increase outdoor journeys.9 Baseline file audits of 77 consecutive referrals across five services in the previous year revealed that 44 out of 77 (57%) people with stroke had received at least one session targeting outdoor journeys, but 22 out of 77 (35%) had received two or more sessions, and only 13 out of 77 (17%) had received six or more sessions. In the original randomised controlled trial that evaluated this intervention,20,21 a median of six sessions targeting outdoor journeys had been provided by therapists. This number of sessions was considered the optimal ‘dose’ (or target) of intervention.

It has been recommended that more than one method should be used to collect data on current practice, as part of a gap analysis (for example, an audit and a survey).2 Collecting information from a small but representative sample of health professionals or patients, using both qualitative and quantitative methods, can be useful.2

In Australia, examples of evidence–practice gaps in healthcare have been summarised by the National Institute of Clinical Studies (NICS).24 This organisation highlights gaps between what is known and what is practised. For example, projects have investigated evidence–practice gaps in the following areas: underuse of smoking cessation programs by pregnant mothers, suboptimal management of acute pain and cancer pain in hospitalised patients and underuse of preventative interventions for venous thromboembolism in hospitalised patients.25

After collating quantitative and qualitative information from a representative sample of health professionals, and/or patients in a facility, the next step is to identify potential barriers and enablers to implementation.

Identifying barriers and enablers to implementation (barrier analysis)

Barriers are factors or conditions that may prevent successful implementation of evidence. Conversely, enablers are factors that increase the likelihood of success. Barriers and enablers can be attributed to individuals (for example, attitudes or knowledge), groups and teams (for example, professional roles) or patients (for example, expectations about intervention). When barriers and enablers have been identified, a tailored program of strategies can be developed.

Attitudinal barriers are easy to recognise. Most health professionals will know someone in their team or organisation that resists change. Perhaps they have been exposed to too much change and innovation. Knowledge, skill and systems barriers are often less obvious (for example, do team members know how to deliver cognitive–behavioural therapy? Do they have access to manuals, video-recorders or vehicles for community visits?). Experienced health professionals may be reluctant to acknowledge a lack of skills, knowledge or confidence. Qualitative methods such as interviews can be useful for investigating what people know, how confident they feel and what they think about local policies, procedures and systems. Social influences can also be a barrier (or an enabler), but may be invisible. For example, patients may expect, and place pressure on, health professionals to order tests or deliver particular interventions.

Methods for identifying barriers are similar to those used for identifying evidence–practice gaps: surveys, individual and group interviews (or informal chats), and observation of practice.26,27 Sometimes it may be useful to use two or more methods. The choice of method will be guided by time and resources, as well as local circumstances and the number of health professionals involved.

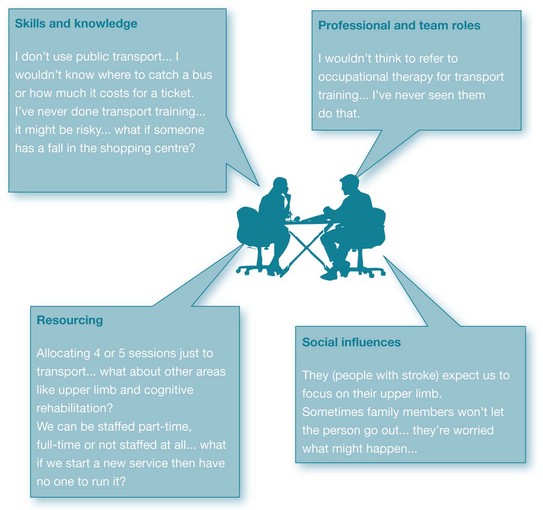

The travel and mobility study involved community occupational therapists, physiotherapists and therapy assistants from two different teams. Individual interviews were conducted with these health professionals. Interviews were tape-recorded with their consent (ethics approval was obtained), and the content was transcribed and analysed. The decision to conduct individual interviews was based on a desire to find out what professionals in different disciplines knew and thought about the planned intervention, and about professional roles and responsibilities. Rich and informative data were obtained;10 however, this method produced a large quantity of information which was time-consuming to collect, transcribe and analyse. A survey or focus group would be more efficient for busy health professionals to use in practice. Examples of quotes from the interviews and four types of barriers from this study are presented in Figure 16.2.

Figure 16.2 Barriers to the delivery of a community-based outdoor journey intervention for people with stroke, identified through qualitative interviews with allied health professionals (n = 13).

Examples of questions to ask during interviews or in a survey, and potential barriers and enablers to consider, are listed in Box 16.2. The list has been adapted from a publication by Michie and colleagues.28

While patient expectations of intervention can be sought, this step often appears to be omitted during barrier analysis. A systematic review of treatment expectations confirmed that most people with acute low back pain who consult their general practitioner expect additional diagnostic tests to be ordered, and a referral to be made to specialists.29 General practitioners in another study also reported a tendency to ‘give in’ to patients' demands for an X-ray and referral to a physiotherapist.30 McKenzie and colleagues7 targeted this lack of confidence as part of their implementation strategy. To help practitioners refer fewer patients for an X-ray, workshops were conducted to model, rehearse and practise persuasive communication techniques during patient consultations. Such strategies targeted the skills, knowledge and confidence of health professionals who had to overcome pressure and social influence from patients.

Resources which can be used to identify barriers and enablers include those produced by the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) in England26 and the National Institute of Clinical Studies (NICS) in Australia.27 An important next step is selecting evidence-based strategies to target identified barriers.

Implementation strategies and interventions

A range of strategies and interventions have been used to target barriers, help health professionals change their behaviour and get evidence into practice. The list is extensive. Frequently used strategies are listed below:

• educational meetings33

• educational outreach visits,34,35 including academic detailing (face-to-face education of health professionals, typically pharmacists and doctors, to change their clinical habits, such as prescribing habits, so that they are in line with best evidence)

• the use of external facilitators36

• reminders,37,38 including patient-mediated and computer-aided interventions

• team building/practice development

• tailored (targeted) interventions or strategies that are planned and take account of prospectively identified barriers to change41

• multifaceted interventions, including several of the above strategies.42

Only some of these strategies have been evaluated for effectiveness and summarised in systematic reviews, or ‘overviews’ of reviews.43,44 Some of the commonly used strategies, and findings from systematic reviews, are discussed next.

Educational materials

This strategy includes the distribution of published or printed materials such as clinical guideline summaries and guideline recommendations. Some authors also include audio-visual materials and electronic publications in their definition of educational materials. Content may be delivered personally or through mass mailouts. Materials may or may not target known knowledge and skill barriers. Such materials are relatively low-cost and feasible to provide, but are unlikely to be effective if they do not target local knowledge barriers.

In Chapter 13, the potential value of evidence-based clinical guidelines was explained. In an attempt to get health professionals to use clinical guidelines, they are often printed and mailed out to health professionals. Alone, mailed dissemination of guidelines is known to have little or no effect on behaviour. Consequently, this process of mailing out guidelines to professionals is often used with control groups in cluster randomised controlled trials. For example, in the study by McKenzie and colleagues,7 doctors in the control group of practices received guideline recommendations about the management of acute low back pain. These guidelines were not expected to change doctors' X-ray ordering behaviour.

A Cochrane review on the effect of printed educational materials located and appraised 23 studies.31 When randomised controlled trials were analysed alone (n = 6), the median effect was 4% absolute improvement (interquartile range −8% to 10%) for categorical outcomes such as X-ray requests and smoking cessation. The relative risk difference for continuous process outcomes such as medication change and X-ray requests per practice was greater (median change 14%, interquartile range −5% to 27%) based on four randomised controlled trials. However, there was no positive effect on patient outcomes. Indeed, a negative effect or deterioration in patient outcomes was reported when data were analysed. The median effect was −4% (interquartile range −1% to −5%) for categorical outcomes such as return to work, screening for a health condition, or smoking cessation. The authors concluded that when compared with no intervention, printed educational materials may positively influence practitioner behaviour but they do not improve patient outcomes.

The overall effect that may be expected from using educational materials to change practice is less than 10% improvement. As this chapter will show, few interventions to change practitioner behaviour result in changes greater than 10%.

Educational meetings

This strategy includes workshops, conferences, meetings and in-service sessions, intended to increase awareness, impart knowledge and develop skills. Meetings can be interactive or didactic. The former may target skills, attitudes and knowledge, whereas didactic sessions mainly target knowledge barriers. Ideally, these sessions target identified skills or knowledge barriers. If practitioners indicate lack of confidence with a new practice, such as cognitive–behavioural therapy in the study by Kramer and Burns,8 educational meetings can help to address the need. In response to therapists' preferences, Kramer and Burns provided a one-day training session which prepared therapists to deliver motivational interviewing and cognitive behavioural therapy, educate adolescents about depression, promote medication adherence and assess ongoing suicide risk.

In the travel and mobility study, occupational therapists and physiotherapists indicated a lack of awareness about the published evidence, as well as a need for information about local transport systems (for example, local bus routes and ticketing systems) and risk management strategies when escorting a person with stroke across roads, to local shops and on public transport.10 They also indicated a preference for a half-day workshop, which was provided.

The most recent review to examine the effect of educational meetings is a 2009 Cochrane review.33 Its findings were consistent with the 2001 review which it replaced, but 49 new trials (total of 81 trials) were added. In most studies, the health professionals were doctors, particularly general practitioners. Targeted behaviours included delivery of preventative health education to patients, such as smoking cessation and exercise, test ordering, screening for disease and prescribing. Median follow-up time was 6 months. Appraisal of the 81 trials revealed much variation in the complexity of behaviours targeted, characteristics of interventions used and results. The median improvement in compliance with practice with any type of educational meeting compared with no intervention was 6% (interquartile range 2% to 16%). Educational meetings can result in small to moderate improvements in professional practice, with smaller improvements in patient outcomes. The 2001 review found interactive education meetings to be more effective than didactic meetings. The 2009 review found mixed interactive and didactic education to be most effective, not interactive education alone. No significant difference was found between multifaceted interventions (those with more than one component) and single interventions. Higher attendance at educational meetings was also associated with greater effects.

Educational outreach visits

An educational outreach visit is defined as a face-to-face visit by a trained person to the practice setting of health professionals, with the intent of improving practice.32,35 This strategy is also known as educational or academic detailing and educational visiting.35 The aim may be to decrease prescribing or test-ordering behaviours, and/or increase screening practices, and/or the routine delivery of an evidence-based intervention. This strategy is derived from social marketing and uses social persuasion methods to target individual knowledge and attitudes. Sessions aim to transmit a small number of messages (two or three) in 15 to 20 minutes, using an approach tailored to individual professionals or practices. Typically, the focus is on simple behaviours such as medication prescribing habits.

An example of the use of outreach visits to change practice was where a trained pharmacist visited general practitioners to discuss childhood asthma management, while also leaving educational materials about best practice. The effect of the educational outreach visits was tested using a cluster randomised controlled trial design, and involved multiple general practices in a township near Cape Town, South Africa.34 Parents of children provided survey data on asthma severity and symptom frequency. Asthma symptom scores declined by 0.8 points more (on a 9-point scale, p = 0.03) in children whose doctor had received outreach visits compared with the control group of children. For every child with asthma seen in a practice which received outreach visits, the authors report that one extra child will experience substantially reduced symptoms.

A systematic review of studies published up until 1998 examined the effect of outreach visits on professional practice.32 This review located and analysed 13 cluster randomised controlled trials, and five controlled before and after studies, with most evaluating outreach visits as part of a multifaceted intervention. When outreach visits were provided as part of a multifaceted intervention, they improved practice by a median of 6% (interquartile range −4% to 17%). The reviewers suggested that organisations should carefully consider the resources and cost involved in providing outreach visits for this modest (6%) change in behaviour. The Cochrane review on the effect of educational outreach visits was last updated in 2007.35 This review appraised 69 studies published up until March 2007, involving more than 15,000 health professionals; 28 studies contributed to the median effect size. The reviewers reported a median (adjusted risk) difference in practice of 6% (interquartile range 3% to 9%). Many of the studies evaluated the effect of outreach visits on prescribing practice. The median effect was more varied when other types of professional practice were examined (median 6%, interquartile range 4% to 16%). The effect of outreach visits was slightly superior to audit and feedback when the two strategies were compared (in eight trials). When individual visits were compared with group visits (three trials), the results were mixed.

Reminders

Reminders aim to prompt a health professional to recall information, such as performing or avoiding some action, to improve individual patient care. A reminder can be provided verbally, on paper or via computer screen. Reminders can be encounter-specific, patient-mediated and/or involve computer-aided decision support.

‘Encounter-specific’ refers to reminders that are delivered to a health professional and associated with particular encounters such as breast screening or dental reviews, or a particular test result. In one example, educational messages about diabetes care were delivered to general practitioners with laboratory test results to help improve the quality of diabetes care.37 Two examples of messages attached to HbA1c (haemoglobin/blood test) reports were: ‘If HbA1c <6.5% = within target for type 2 diabetes’; and ‘If HbA1c 6.5–7.0% = for type 2 diabetes, consider increasing oral therapy’. Other messages targeted blood pressure control and foot inspection. Statistically significant reductions were reported in mean diastolic but not systolic blood pressure following the brief educational messages. The odds of achieving target blood pressure control and receiving a foot inspection during a consultation were increased. However, there was no effect on mean HbA1c or cholesterol levels.

‘Patient-mediated’ reminders involve the person with the health condition taking information to the treating professional to help prompt a practice behaviour. One example is the use of a ‘diabetes passport’,45 a patient-held record. The patient takes a passport with them to appointments, to help prompt monitoring by health professionals of blood pressure and foot health care, amongst other health indicators. After introducing the passports to patients and embedding the passport into general practices in the Netherlands, the effect on patient health outcomes was evaluated using a randomised controlled trial.46 Diabetes passports were issued to 87% of eligible patients. After 15 months, 76% of patients reported that the passport was being used, and referred to, during clinic visits. Process measures of diabetes care improved significantly in intervention practices compared with control practices; for example, HbA1c, creatinine, cholesterol, weight and glucose were examined more often, although blood pressure and foot inspections were not conducted more often. There were no significant differences in patient outcomes such as quality of life, self-advocacy or diabetes knowledge.

In the travel and mobility study, fluorescent pink stickers were provided as a reminder to therapists, containing the messages ‘Screened for outdoor journeys’ and ‘Intervention provided targeting outdoor journeys’. These stickers were placed on the desks of occupational therapists and physiotherapists. The first sticker reminded therapists to ask a series of screening questions about driving status and community outings, complete a screening form and place the form in the patient's file, accompanied by the sticker and a file entry. The second sticker prompted therapists to deliver an outdoor journey intervention to people with stroke who were not getting out as often as they wanted, then document the content of sessions in the patient's file, accompanied by the sticker.

Evidence for the effectiveness of reminders is higher than for most other implementation strategies, but rehabilitation therapists have not been the focus of studies to date. The most recent Cochrane review only examined the effect of pop-up computer screen reminders when used with doctors.38 That study found 28 studies that evaluated the effects of different on-screen computer reminders, for prescribing medications, warning the doctors about drug interactions, providing vaccinations and ordering tests. The review found small to moderate benefits; reminders improved doctors' practices by a median of 4%, with patients' health improving by a median of 3% in eight of the 28 studies. No specific reminders or features of reminders were consistently associated with these larger benefits.

Audit and feedback

Audit refers to any summary of clinical performance over a specified period of time. Feedback about audit findings may be written or oral, and the summary may or may not include details of compliance with audit criteria and recommendations for action. Audit information can be obtained from medical records, computerised databases or by observing patients and professionals. Implementation literature describes audit and feedback together, because there is limited value in conducting an audit if the target professionals do not receive feedback about the findings. Thus, some form of feedback about audit findings is needed.

One aim of audit and feedback is to create some urgency in the health professionals about the need for change. Without objective data from audits, health professionals are likely to perceive that their practice is within acceptable levels. However, it has been demonstrated that self-reports of behaviour are likely to overestimate performance by up to 27%.47

Audits are the mainstay of quality-improvement activities, yet surprisingly few health professionals have conducted an audit. If they have, the audit has typically focused on compliance with note writing and record keeping. Rarely do file audits focus on the content of the interventions. Even fewer audits seem to focus on evidence-based interventions. Audits conducted as part of an implementation process focus on evidence-based processes. For example: ‘Of 50 files audited, what proportion of patients was asked screening questions, as recommended in a clinical guideline?’ or ‘What proportion of patients received written educational materials, as recommended in a clinical guideline?’

A Cochrane review of 118 trials investigated the effect of clinical audits, with or without feedback.39 Feedback after an audit does improve practice, but the effects are small to moderate. The primary outcome of interest was practice change where audit and feedback were used as part of an intervention, for example in combination with an educational meeting. Comparison of dichotomous outcome data (for example, practice changed yes/no) resulted in a median-adjusted risk difference in compliance with desired practice of 5% (interquartile range 3% to 11%). That is, the probability of compliance with desired practice following audit and feedback was approximately 5% greater, compared with other interventions or no intervention. For continuous outcomes such as number of tests or prescriptions, the median-adjusted risk percentage change in practice for professionals who received audit and feedback compared with no intervention was 16% (interquartile range 5% to 37%).

Jamtvedt and colleagues39 did not find a significant difference in the relative effectiveness of audit and feedback, with or without educational meetings or multifaceted interventions. When audit and feedback were used alone (which is rare in clinical practice), the median effect was greater (median-adjusted risk difference of 11.9% for continuous outcomes, interquartile range 5% to 22%) than no intervention. Larger effects were seen if baseline adherence to recommended practice was low and feedback intensity was greater. Audit and feedback should therefore be viewed as a helpful quality-improvement strategy, but caution is required during implementation projects because of the costs associated with data extraction and analysis of audit data. A promising cluster trial is currently underway,40 exploring how feedback can be used to increase acceptability and usability in primary care. The trial aims to determine whether a theory-informed worksheet attached to feedback reports can help general practitioners improve the quality of care provided to patients with diabetes and/or ischaemic heart disease.

In summary, the effectiveness of several implementation strategies has been evaluated in systematic reviews. Most strategies lead to a small change in practice (typically no greater than 10%). Larger changes can be expected if compliance with practice at baseline is low. Health professionals and service managers who evaluate change due to implementation of evidence should not be surprised by changes of this magnitude. A process of continuous quality improvement is the best way to improve practice in line with the evidence, and discussion about this is included in Chapter 17. For updates on the effectiveness of these and other strategies to change behaviour, the website of the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care review group (www.epoc.cochrane.org) is a useful resource.

The use of theory to support evidence implementation

Implementation of evidence is a complex process involving change in attitudes, systems and behaviour. Theories and frameworks are helpful for explaining complex processes. Thus it is helpful to theorise about why a person, organisation or profession succeeded or had difficulty with change, such as delivering an intervention or ceasing to use a test procedure. Theories can also be used for planning. We can anticipate potential problems, such as a change in professionals' (or patient) roles, and target these in advance.

The use of a theory or theoretical framework is now recommended to help identify and address factors that influence the adoption of a new practice behaviour.48,49 Change theories can help us predict who might change, who might be resistant to change, how change might be experienced and the stages of change that most people will move through. Theories can also help inform the development of survey instruments23,50 and interview questions about barriers to evidence uptake.28 Researchers seeking funding, and postgraduate students investigating the implementation of innovations, are now expected to use theories to guide their research.

Grol and colleagues49 have proposed a taxonomy of theories which aim to explain or predict: (1) individual behaviour change (for example, attitudes, routines, motivation); (2) the effect of social context on change (for example, social/peer pressure, opinion leaders, role models); and (3) organisational or team behaviour change (for example, culture, systems, resources). The authors note that most theories overlap, sometimes to a large extent. Grol and colleagues summarised each ‘type’ of theory. Behaviour theories aim to explain behaviour. Cognitive theories aim to explain thought processes, attitudes and values. Social theories aim to explain how social groups or systems operate. Problems can occur at any level. For more in-depth information about this, you may wish to read their summary.49

Theories which explain behaviour change

Some theories explain how change is experienced and factors which promote change. Examples include the transtheoretical stages of change theory by Prochaska and DiClemente51 and the diffusions of innovation theory by Rogers.52

The stages of change theory has been used to guide many implementation studies, particularly those targeting public health behaviours such as cigarette smoking and alcohol consumption.51 Individuals at each of the stages (for example pre-contemplation, contemplation, preparation and action) are typically targeted with different behaviour-change strategies. However, a systematic review which examined the body of research on interventions based on the stages of change theory found no difference in outcomes (amount of behaviour change) in studies using this theory, compared with studies that were not based on this theory.53

Another use of the stages of change theory has been for the development of an instrument to measure attitudes and readiness to change (Clinician Readiness to Measure Outcomes Scale, CReMOS).50 The aim of the CReMOS is to measure clinicians' attitudes to outcome measurement and self-reported changes in attitude and practice, as a result of learning about standardised outcome measures. Sample statements from the 26-item CReMOS questionnaire, associated with the five stages of change, include:

• ‘I know my interventions work. I do not need to measure them.’ (Precontemplation)

• ‘Measuring outcomes would be good if it did not mean spending time doing extra paperwork.’ (Contemplation)

• ‘I have had someone teach me how to search electronic databases to locate relevant outcome measures for my patients.’ (Preparation)

• ‘I have trialled some outcome measures with my patients.’ (Action)

• ‘I have been measuring outcomes with my patients for at least 6 months.’ (Maintenance)

The highly influential theory of diffusion of innovations has been used to help spread many innovations in health services and has been comprehensively reviewed by Greenhalgh and colleagues.4,54 Diffusion is a passive process of social influence, whereas dissemination and implementation are active, planned processes that aim to encourage the adoption of an innovation. The original theory proposed that the spread or diffusion of ideas about a new practice could be achieved by harnessing the influence of opinion leaders and change agents. The social networks of targeted individuals could be mapped and targeted during the diffusion process (who knows whom, and who copies whom). Some individuals lead the adoption (innovators), while others become champions and opinion leaders (the early adopters). A large proportion of individuals adopt the change in practice when change becomes inevitable (the early majority) and can be used to encourage and persuade others (the late majority). And finally, there are always non-adopters who will only change when forced to do so by policy or performance review (the laggards).

Studies and organisations which talk about using ‘opinion leaders’ and ‘champions’ are using ideas from the diffusions of innovation theory. One such study in occupational therapy55 involved using a local opinion leader to teach therapists about evidence-based practice when the phenomenon was new and considered an ‘innovation’. Funding was obtained to train 100 occupational therapists how to search for, and critically appraise, research evidence. The local opinion leader delivered a two-day workshop and encouraged therapists to become ‘champions’ of evidence-based practice in their organisation. To help spread the innovation, therapists provided in-service training at work for other staff and established journal clubs.56

Theories which predict behaviour change

Theories which can help us to anticipate or predict behaviour change include Ajzen's theory of planned behaviour57 and a psychological theory of behaviour change developed by Michie and colleagues.28 When planning to implement evidence, we are often interested in theories which help predict who will, and will not, adopt new practice behaviours. Questions and topics derived from these theories have been used in surveys and interviews, and to map results.

The Theory of Planned Behaviour23,57 is one of the most frequently used theoretical frameworks. This theory proposes that intention and perceived control over behaviour are proximal predictors of behaviour; and while these constructs cannot be directly observed, they can be inferred from survey or questionnaire responses.23 To predict whether a person intends to do something, we need to know whether that person is in favour of doing it (‘attitude’), how much the person feels social pressure to do it (‘subjective norm’) and whether they feel in control of the action in question (‘perceived behavioural control’). The Theory of Planned Behaviour proposes that these three constructs—attitudes, subjective norms and perceived behavioural control—predict the intention to perform a behaviour. Recent systematic reviews have confirmed that there is, indeed, a predictable relationship between the intentions of a health professional and their subsequent behaviour.58,59 However, the review by Godin and colleagues59 suggests that the Theory of Planned Behaviour helps predict behaviour, while other theories better capture intentions. Surveys and questionnaires based on the Theory of Planned Behaviour have been developed and used to investigate attitudes to and beliefs about the uptake of evidence.23

The Psychological Theory of Behaviour Change28 is a more recent addition to the list of theories and also aims to help professionals and researchers anticipate and predict behaviour change. Michie and colleagues28 proposed 12 domains and developed an interview profile which can be used to inform the implementation of evidence, in particular for identifying barriers and strategies to target known barriers. The domains are shown in Table 16.2.

TABLE 16.2:

Examples of questions to ask about barriers to implementation based on two theories of behaviour change

| Focus/domain of question | Theory of planned behaviour23 | Psychological theory of behaviour change28 |

| Knowledge | Do you know about the evidence/guideline? Do you know you should be doing X? |

|

| Skills | Do you know how to deliver X? How easy or difficult do you find performing X? How confident are you about being able to perform X to the required standard in the required context? |

|

| Intentions, motivations and goals | Do you intend to do X with all of your patients? Of the next 10 patients you see with a diagnosis of X, for how many would you expect to do X? |

How much do you want to do X? How much do you feel a need to do X? Are there other things you want to do or achieve that might interfere with X? Does the evidence/guideline conflict with other interventions you want to deliver? Are there incentives to do X? |

| Attitudes and emotions | Are there any issues that come to mind when you think about doing X? Overall do you think that doing X is harmful/pleasant; the right thing to do; the wrong thing to do/good practice? |

Does doing X evoke an emotional response? To what extent do emotional factors facilitate or hinder X? |

| Professional/ social roles | Is it expected that you will do X? | Do you think guidelines or evidence should determine your behaviour? Is doing X compatible or in conflict with your professional role/standards/identity? Would this be true for all professional groups involved? |

| Beliefs about capabilities | Do you believe that you will be able to do X with the patient? | How easy or difficult it is it for you to do X? How confident are you that you can do X in spite of the difficulties? What would help you do X? How capable are you of maintaining X? How well equipped/comfortable do you feel about doing X? |

| Beliefs about consequences | What do you think will happen (to yourself, patients, colleagues and the organisation, positive and negative, short- and long-term consequences) if you do X? What are the costs of X? What do you think will happen if you do not do X? Do the benefits of doing X outweigh the costs? Does the evidence suggest that doing X is a good thing? |

|

| Memory, attention and decision processes | Is X something you usually do? Will you think or remember to do X? How much attention will you have to pay to doing X? Might you decide not to do X? Why? |

|

| Environmental context and resources | To what extent do physical or resource factors facilitate or hinder X? Are there competing tasks and time constraints? Are the necessary resources (staff, equipment etc) available to you and others who are expected to do X? |

|

| Social influence or pressure | Are there any individuals or groups who would approve or disapprove of you doing X? Do you feel under any social pressure to do X with your patients? Do your patients expect or want X? |

To what extent do social influences (for example peers, managers, other professional groups, patients, patients' relatives) facilitate or hinder X? Do you observe others performing X? (that is, do you have role models?) |

| Behavioural regulation | What preparatory steps (individual or organisational) are needed to do X? Are there procedures or ways of working that encourage you to do X? |

|

| Nature of the behaviours | What is the proposed behaviour? Who needs to do what differently, when, where, how, how often and with whom? What do you currently do? Is this a new behaviour, or an existing behaviour that needs to become a habit? Are there systems for maintaining longer-term change? |

As an example, in the travel mobility study involving occupational therapists and physiotherapists,10 interview questions probed for therapists' attitudes, skills and knowledge, as well as role expectations about an outdoor journey intervention for people with stroke. The Psychological Theory of Behaviour Change provided a structure during interviews and, later, during analysis. Some brief examples of comments from therapists are presented in Figure 16.2. The majority of comments made during the 13 interviews could be mapped to two domains: beliefs about capabilities and social influences.

‘It’s quite a time-consuming intervention, in terms of the number of patients you can see, and the number of hours. I think it would be hard to get to the six [sessions of the outdoor journey intervention].’

‘The whole scooter thing is still something they [occupational therapists] are nervous about. How do we know the person’s appropriate for a scooter? How do you assess a person …? and stuff around insurance and all that sort of thing … A lot of therapists don’t get much exposure (to motorised scooters). I've never done a scooter prescription.'

‘Asking about driving, when someone is so unwell, can be an area that you don’t want to go to. It can be the last thing on their mind, and the carers’ mind. “Oh no! He won't get back to driving!” These sort of things could be a bit difficult to initiate in conversation.'

• Social influence (from patients and carers):

‘Sometimes they (people with stroke) are completely focused on their mobility, and tend to think of it (an outdoor journey intervention) as more of a physio thing. Maybe they won’t bring it up with us (the occupational therapists). Others are more focused on getting their arm to work again. Trying to identify goals different from that can be hard. Usually they’ve been told “We're referring you for upper limb therapy” and they become very focused on that. They don't want to look at getting out and about.'

‘We could only achieve the goals he wanted to (work on) and would agree to.’

‘His wife isn’t confident that he can do it. She says “No, he won't be able to do it.” Last week they had the opportunity to catch the train into the therapy session here, but the wife called the son to tell him to take the day off work to bring him in. So we've planned a visit to the coffee shop that he went to. It means catching a train, getting him to buy the tickets, and so on. It's cognitive as well as language. But his wife isn't confident he can do it …'

Michie and colleagues60 have recently added to the behaviour change literature with their ‘behaviour change wheel’. The wheel comprises a hub and three essential conditions for change (capability, opportunity and motivation), nine intervention strategies to address deficits in these conditions and seven categories of policy to enable interventions to occur. The authors suggest that the wheel can be used by health services and policy makers to design more effective, targeted interventions.

Francis and colleagues used this theory and interview schedule with intensive-care consultants and neonatologists to determine which domains might prevent or enable behaviour change.61 The domains relevant to this specialty group were: knowledge, beliefs about capabilities, beliefs about consequences, social influences and behavioural regulation. In another study, doctors' beliefs about consequences and their capabilities were likely determinants of lumbar spine X-ray referrals for patients presenting with low back pain.62

In summary, psychological theories can help service providers to predict who might be resistant to change, and why. Barriers and enablers to change can be identified more accurately, including intentions, attitudes, beliefs, skills and knowledge. These domains can then be targeted using evidence-based interventions as suggested in this chapter. There is supporting evidence that strategies which are tailored to these barriers (for example, education to address a knowledge or skills gap) can change practice.41

References

1. Grol, R. Implementation of changes in practice. In: Grol R, Wensing M, Eccles M, eds. Improving patient care: the implementation of change in clinical practice. Edinburgh: Elsevier Butterworth–Heinemann; 2005:6–15.

2. van Bokhoven, M, Kok, G, Weijden, V. Designing a quality improvement intervention: a systematic approach. Qual Saf Health Care. 2003; 12:215–220.

3. Grol, R, Wensing, M. Effective implementation: a model. In: Grol R, Wensing M, Eccles M, eds. Improving patient care: the implementation of change in clinical practice. Edinburgh: Elsevier Butterworth–Heinemann; 2005:41–57.

4. Greenhalgh, T, Robert, G, Bate, P, et al. Diffusions of innovations in health service organisations: a systematic review. Oxford, UK: BMJ Books; 2005.

5. Woolf, S. The meaning of translational research and why it matters. JAMA. 2008; 299:211–213.

6. Davis, D, Evans, M, Jadad, A, et al. The case for knowledge translation: shortening the journey from evidence to effect. BMJ. 2003; 327:33–35.

7. McKenzie, J, French, S, O'Connor, D, et al. IMPLEmenting a clinical practice guideline for acute low back pain evidence-based manageMENT in general practice (IMPLEMENT): Cluster randomised controlled trial study protocol. Implement Sci. 2008; 3:11.

8. Kramer, T, Burns, B. Implementing cognitive behavioural therapy in the real world: a case study of two mental health centres. Implement Sci. 2008; 3:14.

9. McCluskey, A, Middleton, S. Feasibility of implementing an outdoor journey intervention to people with stroke: a feasibility study involving five community rehabilitation teams. Implement Sci. 2010; 5:59.

10. McCluskey, A, Middleton, S. Delivering an evidence-based outdoor journey intervention to people with stroke: barriers and enablers experienced by community rehabilitation teams. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010; 10:18.

11. Britt, H, Miller, G, Charles, J, et al. General practice activity in Australia 2009–10. General Practice Series No 27. AIHW Cat No GEP 27. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare; 2010.

12. National Health and Medical Research Council and Australian Acute Musculoskeletal Pain Guidelines Group. Evidence-based management of acute musculoskeletal pain: a guide for clinicians. Bowen Hills, Qld: Australian Academic Press; 2004.

13. Williams, C, Maher, C, Hancock, M, et al. Low back pain and best practice care: a survey of general practice physicians. Arch Int Med. 2010; 170:271–277.

14. Klein, J, Jacobs, R, Reinecke, M. Cognitive-behavioural therapy for adolescent depression: a meta-analytic investigation of changes in effect-size estimates. J Am Acad Child Adoles Psychiatry. 2007; 46:1403–1413.

15. Weersing, V, Weisz, J. Community clinic treatment of depressed youth: benchmarking usual care against CBT clinical trials. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2002; 70:299–310.

16. Chua, M, McCluskey, A, Smead, J. Retrospective analysis of factors that affect driving assessment outcomes after stroke. Aust J Occ Ther. 2012; 59:121–130.

17. Fisk, G, Owsley, C, Pulley, L. Driving after stroke: driving exposure, advice and evaluations. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1997; 78:1338–1345.

18. Mackintosh, S, Goldie, P, Hill, K. Falls incidence and factors associated with falling in older, community-dwelling, chronic stroke survivors (>1 year after stroke) and matched controls. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2005; 17:74–81.

19. National Stroke Foundation. Clinical guidelines for stroke management. Melbourne: National Stroke Foundation; 2010.

20. Logan, P, Gladman, J, Avery, A, et al. Randomised controlled trial of an occupational therapy intervention to increase outdoor mobility after stroke. BMJ. 2004; 329:1372–1377.

21. Logan, P, Walker, M, Gladman, J. Description of an occupational therapy intervention aimed at improving outdoor mobility. Br J Occup Ther. 2006; 69:2–6.

22. Glasziou, P, Haynes, B. The paths from research to improved health outcomes. ACP J Club. 2005; 142:A8–A9.

23. Francis, J, Eccles, M, Johnstone, M, et al, Constructing questionnaires based on the theory of planned behaviour: a manual for health services researchers. Centre for Health Services Research, University of Newcastle, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2004. Online Available pages.bangor.ac.uk/~pes004/exercise_psych/downloads/tpb_manual.pdf [23 Nov 2012].

24. National Institute of Clinical Studies (NICS). Evidence–practice gaps report (volumes 1 and 2). Melbourne: NICS; 2005.

25. National Institute of Clinical Studies (NICS). Evidence–practice gaps report, volume 1: a review of developments 2004–7. Melbourne: NICS; 2008.

26. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE), How to change practice: understand, identify and overcome barriers to change. NICE, London, 2007. Online Available www.nice.org.uk/usingguidance/implementationtools/howtoguide/barrierstochange.jsp [14 Nov 2012].

27. National Institute of Clinical Studies (NICS), Identifying barriers to evidence uptake. NICS, Melbourne, 2006. Online Available www.nhmrc.gov.au/nics/materials-and-resources/identifying-barriers-evidence-uptake [14 Nov 2012].

28. Michie, S, Johnston, M, Abraham, C, et al. Making psychological theory useful for implementing evidence based practice: a consensus approach. Qual Saf Health Care. 2005; 14:26–33.

29. Verbeek, J, Sengers, M, Riemens, L, et al. Patient expectations of treatment for back pain: a systematic review of qualitative and quantitative studies. Spine. 2004; 29:2309–2318.

30. Schers, H, Wensing, M, Huijsmans, Z, et al. Implementation barriers for general practice guidelines on low back pain: a qualitative study. Spine. 2001; 26:E348–E353.

31. Farmer, A, Legare, F, Turcot, K, et al. Printed educational materials: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (3):2008. [CD004398. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004398.pub2].

32. Grimshaw, J, Eccles, M, Thomas, R, et al. Toward evidence-based quality improvement: evidence (and its limitations) of the effectiveness of guideline dissemination and implementation strategies 1966–1998. J Gen Intern Med. 2006; 21:S14–S20.

33. Forsetlund, L, Bjorndal, A, Rashidian, A, et al. Continuing education meetings and workshops: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2):2009. [CD003030. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003030.pub2].

34. Zwarenstein, M, Bheekie, A, Lombard, C, et al. Educational outreach to general practitioners reduces children's asthma symptoms: a cluster randomised controlled trial. Implement Sci. 2007; 2:30.

35. O'Brien, M, Rogers, S, Jamtvedt, G, et al. Educational outreach visits: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (4):2007. [CD000409. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000409.pub2].

36. Stetler, C, Legro, M, Rycroft-Malone, J, et al. Role of ‘external facilitation’ in implementation of research findings: a qualitative evaluation of facilitation experiences in the Veterans Health Administration. Implement Sci. 2006; 1:23.

37. Foy, R, Eccles, M, Hrisos, S, et al. A cluster randomised trial of educational messages to improve the primary care of diabetes. Implement Sci. 2011; 6:129.

38. Shojania, KG, Jennings, A, Mayhew, A, et al. The effects of on-screen, point of care computer reminders on processes and outcomes of care. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (3):2009. [CD001096. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001096.pub2].

39. Jamtvedt, G, Young, J, Kristoffersen, D, et al. Audit and feedback: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2):2010. [CD000259. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000259.pub2].

40. Ivers, NM, Tu, K, Francis, J, et al. Feedback GAP: study protocol for a cluster-randomised trial of goal setting and action plans to increase the effectiveness of audit and feedback interventions in primary care. Implement Sci. 2010; 41:5. [98].

41. Baker, R, Camosso-Stefinovic, J, Gillies, C, et al. Tailored interventions to overcome identified barriers to change: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (3):2010. [CD005470. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005470.pub2].

42. Wright, J, Bibby, J, Eastham, J, et al. Multifaceted implementation of stroke prevention guidelines in primary care: cluster-randomised evaluation of clinical and cost effectiveness. Qual Saf Health Care. 2007; 16:51–59.

43. Bero, L, Grilli, R, Grimshaw, J, et al. Closing the gap between research and practice: an overview of systematic reviews of interventions to promote the implementation of research findings. BMJ. 1998; 317:465–468.

44. Grimshaw, J, Shirran, L, Thomas, R, et al. Changing provider behavior: an overview of systematic reviews of interventions. Med Care. 2001; 39:II2–I45.

45. Dijkstra, R, Braspenning, J, Huijsmans, Z, et al. Introduction of diabetes passports involving both patients and professionals to improve hospital outpatient diabetes care. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2005; 68:126–134.

46. Dijkstra, R, Braspenning, J, Grol, R. Implementing diabetes passports to focus practice reorganisation on improving diabetes care. Int J Qual Health Care. 2008; 20:72–77.

47. Adams, A. Evidence of self-report bias in assessing adherence to guidelines. Int J Qual Health Care. 1999; 11:187–192.

48. Ceccato, N, Ferris, L, Manuel, D, et al. Adopting health behaviour change theory through the clinical practice guideline process. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2007; 27:201–207.

49. Grol, R, Wensing, M, Hulscher, M, et al. Theories of implementation of change in healthcare. In: Grol R, Wensing M, Eccles M, eds. Improving patient care: the implementation of change in clinical practice. Edinburgh: Elsevier Butterworth–Heinemann; 2005:15–40.

50. Bowman, J, Lannin, N, Cook, C, et al. Development and psychometric testing of the Clinician Readiness for Measuring Outcomes Scale (CReMOS). J Eval Clin Pract. 2009; 15:76–84.

51. Prochaska, J, DiClemente, C. In search of how people change: applications to addictive behaviours. Am Psychol. 1992; 47:1102–1114.

52. Rogers, EM. Diffusion of innovations, 4th ed. New York: Free Press; 1995.

53. Reisma, R, Pattenden, J, Bridle, C, et al. A systematic review of the effectiveness of interventions based on a stages of change approach to promote individual behaviour change. Health Technol Assess. 2002; 6:1–243.

54. Greenhalgh, T, Robert, G, Macfarlane, F, et al. Diffusion of innovations in service organisations: systematic review and recommendations. Milbank Q. 2004; 82:581–629.

55. McCluskey, A, Lovarini, M. Providing education on evidence-based practice improved knowledge but did not change behaviour: a before and after study. BMC Med Educ. 2005; 5:40.

56. McCluskey, A, Home, S, Thompson, L. Becoming an evidence-based practitioner. In: Law M, MacDermid J, eds. Evidence-based rehabilitation: a guide to practice. 2nd ed. Thorofare, NJ: Slack; 2008:35–60.

57. Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behaviour. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process. 1991; 50:179–211.

58. Eccles, M, Hrisos, S, Francis, J, et al. Do self-reported intentions predict clinicians’ behaviour: a systematic review. Implement Sci. 2006; 1:28.

59. Godin, G, Belanger-Gravel, A, Eccles, M, et al. Healthcare professionals’ intentions and behaviours: a systematic review of studies based on social cognitive theories. Implement Sci. 2008; 3:36.

60. Michie, S, van Stralen, M, West, R. The behaviour change wheel: a new method for characterising and designing behavior change interventions. Implement Sci. 2011; 6:42.

61. Francis, J, Stockton, C, Eccles, M, et al. Evidence-based selection of theories for designing behaviour change interventions: using methods based on theoretical construct domains to understand clinicians’ blood transfusion behaviour. Br J Health Psychol. 2009; 14:625–646.

62. Grimshaw, J, Eccles, M, Steen, N, et al. Applying psychological theories to evidence-based clinical practice: identifying factors predictive of lumbar spine x-ray for low back pain in UK primary care practice. Implement Sci. 2011; 6:55.