Embedding evidence-based practice into routine clinical care

After reading this chapter, you should be able to:

• Understand that evidence-based practice occurs at micro, meso and macro levels of organisations

• Explain why organisations should promote evidence-based practice

• Describe the characteristics of organisations which integrate evidence-based practice

• Describe specific strategies that organisations might use to support evidence-based practice

Evidence-based practice can be conceptualised as operating at three organisational levels:

• microsystems of clinical departments, units, wards or clinical practices

• mesosystems such as hospitals and large group-practices

• macrosystems of health departments, general practice governing organisations, professional societies and clinical service networks.

Microsystems can be regarded as first-order units of practice in which health professionals, either as individuals or as tightly connected small groups, directly confront challenges in integrating evidence into the routine care of individual patients. This can occur at the bedside, clinic, community and through regular interactions with nearby colleagues. Until this chapter, this book has primarily focused on the skills required to undertake evidence-based practice at this level and described the use of the five-step process for evidence-based practice.

Barriers to evidence-based practice at the microsystem level have been explored in many studies, across many settings and many professional groups, and in various countries (see for example references 1–5). There is remarkable consistency in the major barriers that have been identified, and some of these are summarised in Table 17.1.

TABLE 17.1:

Commonly identified barriers to embedding evidence-based practice into routine clinical practice

| Barrier | Description |

| Skills | A lack of skills in searching for, interpreting and applying research among health professionals means that they are insecure about changing practice from what they have read. There is also often too little support for doing so (including from senior colleagues with skills in evidence-based practice). |

| Time | In the chaos of everyday clinical practice, ‘running behind’, or dealing with urgent clinical situations, is common. The time pressure of administration and other responsibilities that health professionals have, coupled with the time taken for finding, let alone reading and appraising, the evidence, means that evidence-based practice is all too easily a casualty of being busy. |

| Attitudes | The traditional view of knowledge attainment (and thus, by extension, evidence-based practice) is that it is separate from clinical practice. That is, it is the responsibility of the individual health professional and, often, to be undertaken at the health professional's own expense and time. These attitudes may be held by both health professionals and the organisations where they work. |

But health professionals, as either individuals or small groups, do not work in a vacuum. They operate within the mesosystems of large organisations. These, in turn, are influenced by external forces which come from the macrosystems level of government and professional governance bodies which define healthcare policies, standards and norms of practice. All three levels are interdependent and this is reflected in the evolution of our understanding of, and approach towards, translating evidence into practice over the last 20 years or so.6

The complexity and interrelatedness of these three levels was acknowledged in the previous chapter (Chapter 16), where we examined strategies which could be used to more consistently incorporate evidence into practice (either to accelerate the adoption of evidence-based practices or to discontinue interventions or assessment practices that are not supported by appropriate evidence). We overviewed strategies that can be used to narrow the gaps between current practice and practice that is based on the most rigorous evidence available, and also highlighted the influences and involvements of individuals, organisations and systems to achieve this aim.

Similarly, successfully using the steps of evidence-based practice in routine clinical work (as opposed to translating specific research evidence into practice, as discussed in Chapter 16) is not solely a function of behaviour or responsibility of individual health professionals. It also requires enablers and reinforcers which operate throughout different levels of the system of care in which health professionals work. There are enablers and reinforcers for each of the three major types of barriers to evidence-based practice listed in Table 17.1 (that is, skills, time and attitudes). The prime focus of this chapter is the organisational settings (or systems of care) that determine the extent to which evidence-based practice becomes more (much more for some) an everyday part of the clinical work that is done at the level of individuals and small groups.

Why is a systems approach important?

A systems approach examines what can be done at the organisational level to foster evidence-based practice as a core component of organisational activity. What can we do to make evidence-based practice part of the mission statement or modus operandi, or even the ‘brand’, of an organisation? How do we systematise the strategies for improving translation of evidence into practice (that were discussed at the health professional level in Chapter 16) at the level of the organisation?

The premise is that if organisations endorse evidence-based practice as ‘the way we do things around here’, then their policies, procedures, infrastructure and governance are more likely to support evidence-based practice. This then makes it easier for the individuals within the organisation to practise this way. Organisations need structures, processes and cultures that can accommodate the complexity of implementing evidence-based practice in daily operations.

Why should organisations want to promote evidence-based practice?

1 Maintaining reputation and ‘market share’

Organisations—not just the individual health professionals who work within them—are now held more accountable for ensuring that the care they provide is safe, effective and of high quality. It is no longer the sole responsibility of individual health professionals to provide good care: the organisation itself can now suffer loss of reputation, staff and revenue if it is not seen as proactively nurturing evidence-based practice. Moreover, organisations do not operate in isolation, but instead in a constantly changing environment of new healthcare and information technologies, novel multidisciplinary models of care and changing societal expectations. All this necessitates clinical practice to be constantly informed (and re-informed) by good evidence if the organisation is to retain respect and authority within the community at large. Organisations also need to do this if they want to entice increasingly sophisticated and demanding recipients of care to pass through their doors.

2 Innovation is associated with better delivery of care

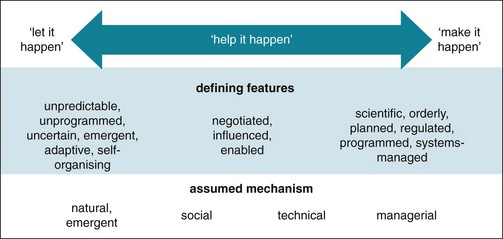

Organisations which foster evidence-based practice are more likely to be innovative, challenge orthodox practice and be ready to adopt new safety and quality initiatives that benefit patients. They are also more exciting and professionally satisfying to work in. A large-scale empirical study among the entire population of public hospital organisations (n = 173) that are part of the English National Health Service revealed a significant positive relationship between science- and practice-based innovation and clinical performance.7 Other studies have revealed an association between evidence-based practice support systems and improved patient safety, reduced complications and shorter length of stay among Medicare beneficiaries in acute care hospitals in the United States.8 An organisation's receptivity to, and readiness for, change are key determinants to how quickly and successfully new innovations in practice are adopted.9 This is illustrated in Figure 17.1. Importantly, theories around organisational change readiness and implementation emphasise that change is both a social and a technical innovation. That is, whether change occurs or not depends just as much on group psychology and mindsets, internal and external socio-political influences, peer pressures and cultural attitudes as it does on implementing data systems or reconfiguring equipment and service resources.

Figure 17.1 The spread of innovation in an organisation: its defining features and assumed mechanism. Adapted from Greenhalgh T, et al. Diffusion of innovations in service organizations: systematic review and recommendations. Milbank Quarterly 2004; Fig 2.9 Copyright 2004 Milbank Memorial Fund. Published by Blackwell Publishing; reproduced with permission.

3 Efficiency

In an era of limited resources but expanding demand for health care, organisations must learn to do more with less. This means they must discontinue—and disinvest from—clinical practices which consume resources but do not add value to patient care. Various ways of doing this have been proposed, including:

• eliminating waste—for example, stopping waste such as duplicated tests as well as unnecessary tests, procedures and treatments that confer no health benefit.10 It has been estimated that this may account for as much as 30% of healthcare costs;11,12

• reducing diagnostic and treatment variation among health professionals and between communities; and

• reforming medical liability laws to decrease the practice of defensive medicine.

Many of these approaches (for example, reducing overuse, avoiding preventable complications and improving inefficient processes) are under way in many organisations, in both private and public sectors.13 Greater alignment of clinical practice with evidence-based practice could result in significant savings in healthcare expenditure14 or, at the very least, better value care for the monies spent.

Culture and characteristics of organisations which integrate evidence-based practice

Introducing any innovation, including evidence-based practice, is challenging and occurs within a complex organisational context. The culture of an organisation influences attitudes towards the use of evidence-based practice and the change process itself.15 An organisation's culture refers to the norms and expectations about how things are done in an organisation16 or, more simply: ‘how things are done around here’. An organisation's culture can affect staff attitudes, perceptions and behaviour.15 Therefore, fostering a culture which is constructive and supportive of evidence-based practice is a key enabler of evidence-based practice. Some of the key characteristics of organisations that support the use of evidence-based practice are outlined below.

1 Active senior leadership commitment and support for evidence-based practice

Organisationally-driven evidence-based practice is more likely when senior leaders (such as clinical directors and managerial executives) promote change and foster a learning environment.17,18 Leadership styles that positively influence the use of evidence-based practice have been described as transactional and/or transformative.19 Transformative leadership supposes a strong attachment between the leader and their ‘followers’, such that the leader is then able to inspire and motivate others through role-modelling and mentoring.20 Role models are very powerful change agents in the behaviour of health professionals. If senior health professionals perform evidence-based practice as part of routine care themselves, this is an important influence on other staff. For this reason alone, organisations should expect competence in evidence-based practice in their senior staff when offering appointments. Competency in this should be evaluated when undertaking professional performance reviews (perhaps based on documented evidence-based audits of clinical practice and 360° feedback from working colleagues). By spending their own time and effort on activities that directly support evidence-based continuous improvement and quality of care, senior leaders demonstrate the personal commitment and investment needed for sustained improvement.17

Transactional leadership makes use of rewards for meeting specific goals or performance criteria.21 Examples of transactional leadership strategies that foster evidence-based practice include: performance appraisals for reviewing staff members' goals and learning needs for evidence-based practice; rostering time; providing remuneration; and organising physical resources (meeting rooms, audio-visual equipment, data systems, etc) which encourage staff to undertake a myriad of activities that foster evidence-based practice. Examples of these are journal clubs, practice reviews, bedside teaching, seminars and workshops, clinical audits and quality and safety improvement projects. Leaders may also create opportunities to communicate successes and failures and reward those who have championed evidence-based practice. Examples of rewards include: academic or peer commendations, sponsorship of presentations at professional meetings, awarding credits for maintenance of professional standard programs or continuing professional development schemes20 and providing further training and leadership opportunities.22

2 Infrastructure of clinical informatics

For evidence-based practice to work, health professionals need ready access to three forms of data:

A evidence in response to specific clinical questions posed during the course of doing routine clinical work;

B guidelines and other forms of evidence guidance (for example clinical decision support systems) which can inform commonly performed clinical decisions; and

C metrics of current practice for the purposes of conducting audits and identifying evidence–practice gaps—that is, the gaps between current practice (what we are doing) and best practice as defined by best available evidence (what we should be doing).

A Access to evidence to answer specific questions

It is essential that organisations provide access to the relevant electronic literature databases for searching. This is normally provided through an organisation's library. In the community or smaller organisations, library services can be more of a problem. Obtaining full-text papers may have to rely on professional organisations (colleges, societies, associations or academies). Nevertheless, off-site access to free databases is becoming more easily achieved (see Chapter 3).

Health and medical librarians (now increasingly called ‘clinical informationists’) are important in helping to seek out the evidence that is requested by health professionals. Information requests (in the form of clinical questions) received from health professionals are reformatted into ‘answerable questions’, evidence is searched for, critically appraised (sometimes) and then returned to the health professional. Health professionals can then decide how to apply the evidence in the clinical setting from which the questions originated. In some cases, clinical informationists actually attend ward rounds and clinics, recording questions as they arise and then finding relevant evidence. Experiments featuring standardised literature searches and feedback of results to practising health professionals have changed practice for the better.23 These services, in one form or another, exist in many organisations and target not only health professionals but also managers and policy-makers.24

Several services have been established, some more successful than others. One of the most enduring is the ATTRACT service (www.attract.wales.nhs.uk), which runs in Wales, UK.25 It has become embedded into the routine of many health professionals in the country, and the database of questions asked, and their answers, have themselves become a valuable resource—the TRIP database (www.tripdatabase.com), which was explained in Chapter 3. Question-answering services have been trialled in other countries, such as Australia and Canada.26,27 However, these services come at a cost and although they are probably cost-effective in terms of cost-savings resulting from better care,28 budgetary constraints probably act as a barrier to their wholesale introduction. They can also fail from poor demand, possibly because the culture of asking questions (itself an evidence-based practice skill, as discussed in Chapter 2) is underdeveloped in many organisations.

B Access to clinical decision support systems

Such systems, especially if computerised, have great potential to assist evidence-based practice. If they are well designed and field-tested with health professional input,29 they can significantly improve quality of care and patient outcomes. The information devices which underpin clinical decision support systems are moving away from fixed desktop computers to more-portable and -personal digital devices such as notebooks, tablets and smart-phones. This technology now allows instant availability of evidence search engines, evidence-based clinical guidelines and pathways and clinical prediction rules. Research is starting to show benefits in terms of better and more-timely care.30,31 This technology places the individual health professional firmly in the driver's seat for accessing and applying evidence to patient care.

However, organisations must commit to resourcing and maintaining the physical devices (such as repairing and renewing them) and the quality of the content found on them (such as ensuring that evidence resources are valid and up-to-date), and ensuring a proficient skill level of those who use them (such as by mandating ongoing health professional training and assessment). It has been shown that when given access to online information sources, health professionals from different disciplines are able to find correct answers to at least half of their clinical questions.32

C Access to databases for auditing current practice

In most healthcare facilities, data are collected routinely for non-clinical purposes (often financial reasons!). In hospitals, different clinical units centralise collection of discrete data that reflect the single focus of the clinical activity (for example, postoperative wound infections). In contrast, in community clinical settings, data are usually routinely collected only for individual patients. This presents challenges to getting aggregate data on outcomes. Aggregating data can also be complicated (for example, by ethical issues) by the use of electronic patient-held records which are being introduced in some settings (www.ehealthinfo.gov.au). In addition, community health settings usually deal with a far greater range of clinical problems (because there is less specialisation in community-based care). This means there are many more categories of care, with fewer components in each category. Both of these elements combine to mean that if data are needed to identify evidence–practice gaps, or to decide about the adoption of a change in practice based on new evidence, then the data may have to be collected as an independent effort rather than using data that is routinely collected for other purposes. However, in the near future, electronic health records, which are already extensively employed in many primary care settings, may offer the ability to quickly extract de-identified clinical data that examines routine care with reference to evidence-based standards.

3 Provision of training

Organisations must provide the necessary education and training to enable all health professionals to have skills in evidence-based practice. A systematic review of interactive teaching of evidence-based practice around clinical cases (that is, clinically integrated with everyday work) found that this style of teaching changes knowledge and skills much more effectively than didactic lectures or tutorials.33 Focused teaching in evidence-based practice (and access to electronic searching facilities) has been shown to improve the quality of care and the number of evidence-based interventions used by health professionals.34 When considering which educational format to use for learning about evidence-based practice, small-group interaction, role-play and simulation of real-world learning environments, mentorship, and high educator to learner ratios have been found to be associated with more-effective learning.35,36 In addition to the general evidence-based practice skills, health professionals also need to learn skills in decision making (that is, placing the evidence in perspective against the circumstances and needs of the patient)37 and skills in communicating evidence to patients (which were described in Chapter 14).

Organisations need to maximise evidence-based practice learning opportunities. Some suggestions for ways of doing this are by:

• quarantining a little ‘offline’ time, away from clinical duties (perhaps weekly);

• expecting health professionals to attend courses/workshops to learn evidence-based practice skills; and

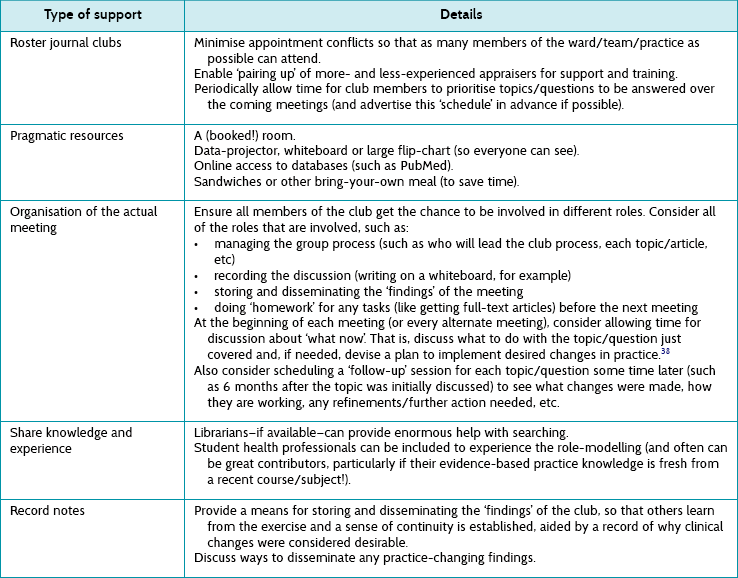

Evidence-based journal clubs (as opposed to the traditional, and more common, journal club which is typically not evidence-based) are especially important. They focus on ‘pull’ strategies (see Chapter 2), in which health professionals bring along questions that have arisen during routine clinical work, search for the answers in the form of evidence and critically appraise the evidence. Such exercises require support from the organisation if they are to work well. Some examples of the support needed are outlined in Table 17.2.

4 Using evidence-based practice to improve quality and safety

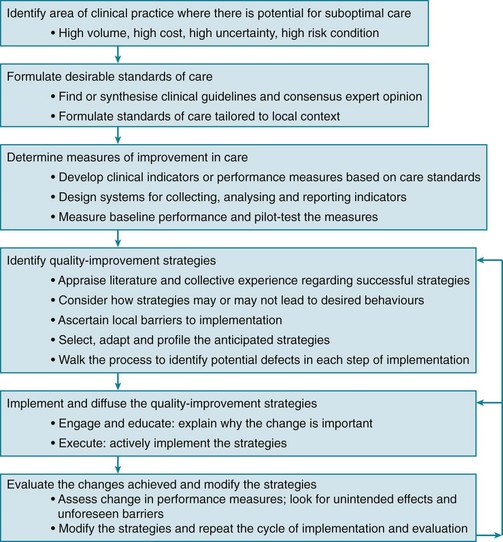

Evidence-based practice and the new science of quality and safety improvement (QSI) complement each other. New evidence will drive new QSI initiatives. Conversely, QSI aspirations will need best available evidence. How you decide what changes to make takes you to the growing literature around evidence-based QSI interventions itself. One approach to QSI is predicated on the use of evidence, as shown in Figure 17.2.39

Figure 17.2 Quality and Safety Improvement (QSI) and how evidence-based practice is a necessary component. From Scott I, Phelps G. Measurement for improvement: getting one to follow the other. Internal Medicine Journal 2009; Fig 1.39 © 2009 Royal Australasian College of Physicians; reproduced with permission.

The focus of evidence-based practice is on ‘doing the right things’, whereas quality improvement focuses more on ‘doing things right’. Combined, these processes help us to ‘do the right things right’.40 The implication is that those who work in quality-improvement teams need to consider the validity, applicability and value of the change being introduced, and those who work from an evidence-based practice perspective need to look beyond the evidence to consider how change might be introduced in the local context.

In recent times, several developments have consolidated the linking of evidence-based practice with QSI:

A Clinical registries: registries which collect and analyse process and outcome data on large cohorts of patients from multiple hospitals and practices have grown in number in recent years41 and provide an objective, audit-based window into real-world clinical practice and its possible shortcomings. Organisations which participate in such registries demonstrate evidence-based practice in action and are associated with higher-quality care. Registries can also generate new knowledge about effectiveness of care in unselected patients that may not be obvious in the results of randomised trials that seek to determine efficacy in highly selected populations.

B Quality improvement collaborations: hospitals and other healthcare organisations can share data and experiences about care for specific patient populations and learn from each other about how to improve care and close evidence–practice gaps. Such collaborations can achieve substantial improvement in evidence-based care processes within relatively short time spans at relatively low cost.42–44

C Health service accreditation: this is increasingly looking not just at structures (such as buildings, staffing levels, physical infrastructure) but also at outcomes (quality of care). Accreditation teams now expect healthcare organisations to integrate an evidence-based quality improvement framework into their operations with proactive remediation of identified instances of suboptimal care. To date, particular attention has been given to the care of common presentations which are associated with high morbidity or high resource utilisation.

There is also a Cochrane group (The Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Group; epoc.cochrane.org) which reports on what QSI interventions are effective.

5 Changing clinical processes

Finding and doing better ways to do things is dependent on the ability to change. The success and the speed of adoption of evidence-based practice are related. Successful adoption of evidence-based practice in an organisation requires an organisational ethos and governance structure which are committed to the ongoing redesign of clinical care processes in response to new evidence about patient need and the effectiveness of interventions. Importantly, clinical process redesign, if it is to be successful and sustained, has to be driven and owned internally by the members of the organisation, not imposed or led by external agencies.45 What should change is determined by evidence.21 Clinical redesign is made up of several stages:

• providing a platform for building evidence-based practice reliably into routine work, rather than layering it on top of existing work as an added demand;46

• facilitating change by engaging health professionals in high-priority problem-solving around concrete and meaningful issues and providing them with the training and information necessary to effect change;17,47 and

• maintaining momentum for further change and improvement. Success motivates staff to go further with improvement to achieve more success.

Successful clinical process redesign relies on having all the enabling organisational characteristics that have already been discussed operating simultaneously within the one organisation. To illustrate this, several exemplars of large-scale clinical process redesign are described in Box 17.1.

6 Organisational policies which embrace evidence-based practice

An organisation's policies can influence the extent to which evidence-based practice is embraced within the organisation. Policy statements indicate an organisation's position or principles regardless of whether this organisation is at the level of government, a profession, a healthcare agency or a non-profit health organisation. Many organisations now incorporate the principle of evidence-based practice as part of their policies. In turn this can influence governance structures, purchasing decisions and expectations for employees. Some organisations have position statements which are supportive of evidence-based practice that are designed to be visionary. However, other organisations go further and provide policies which inform governance structures that include expectations that employees will engage in evidence-based practice (for example, by meeting competency requirements or to support credentialling).56 This is not to be confused with evidence-based policy which concerns the use of research evidence to inform policy development.

Most health professionals have an organisation (College, Association or Academy) to support them in their professional development. Some have developed resources and methods of facilitating skill development related to evidence-based practice, especially upskilling in question-asking, searching and critical appraisal. Maintenance of professional standards schemes also give increasing levels of credit points to audit and practice review activities that seek to align and remediate evidence–practice gaps. Many health professional organisations also have specific policy statements about evidence-based practice in the form of position statements. A few extracts from position statements from different disciplines are provided in Box 17.2 as examples.

Organisational policies which support evidence-based practice (however specific this may be) are an essential means by which the organisation communicates a willingness to embrace a culture of evidence-based practice, and helps to establish the norms and expectations about how things are to be done.

Conclusion

In this chapter we have explained why promoting evidence-based practice is important to organisations and how they might go about it. Box 17.3 summarises the most pertinent strategies for supporting evidence-based practice.57–59 Ensuring that patients receive evidence-based healthcare requires healthcare organisations to be proactive in adopting evidence-based practice across the spectrum of their activities. This requires:

• active top leadership commitment and support

• a well-developed and user-friendly infrastructure of clinical informatics

• dedicated training of health professionals in the direct application of evidence to clinical care

• alignment of evidence-based practice with quality and safety improvement frameworks

• systematised clinical process redesign in response to new evidence-based clinical practices

• evidence-based health policy-making at the level of senior executives.

Professional organisations also have a role in promoting evidence-based practice by developing resources and methods in question-asking, searching and critical appraisal relevant to their members. While the key factor in advancing evidence-based practice will always remain the individual health professional, the existence of an organisational environment which recognises the value of, and encourages, evidence-based practice will add immeasurable value in accelerating and expanding the benefits of evidence-based practice to all who seek care within our healthcare organisations.

References

1. McColl, A, Smith, H, White, P, et al. General practitioners' perceptions of the route to evidence based medicine: a questionnaire survey. BMJ. 1998; 316:361–365.

2. Burkiewicz, J, Zgarrick, D. Evidence-based practice by pharmacists: utilisation and barriers. Ann Pharmacother. 2005; 39:1214–1219.

3. Bennett, S, Tooth, L, McKenna, K, et al. Perceptions of evidence based practice: a survey of occupational therapists. Aust Occup Ther J. 2003; 50:13–22.

4. Al-Almaie, S, Al-Baghli, N. Barriers facing physicians practicing evidence-based medicine in Saudi Arabia. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2004; 24:163–170.

5. Lai, N, Teng, C, Lee, M. The place and barriers of evidence based practice: knowledge and perceptions of medical, nursing and allied health practitioners in Malaysia. BMC Res Notes. 2010; 3:279.

6. Scott, I. The evolving science of translating research evidence into clinical practice. Evid Based Med. 2007; 12:4–7.

7. Salge, T, Vera, O. Hospital innovativeness and organizational performance: evidence from English public acute care. Health Care Manage Rev. 2009; 34:54–67.

8. Bonis, P, Pickens, G, Rind, D, et al. Association of a clinical knowledge support system with improved patient safety, reduced complications and shorter length of stay among Medicare beneficiaries in acute care hospitals in the United States. Int J Med Inform. 2008; 77:745–753.

9. Greenhalgh, T, Robert, G, Macfarlane, F, et al. Diffusion of innovations in service organizations: systematic review and recommendations. Milbank Q. 2004; 82:581–629.

10. American College of Physicians, How can our nation conserve and distribute health care resources effectively and efficiently? Policy paper. American College of Physicians, Philadelphia, 2011. Online Available www.acponline.org/advocacy/where_we_stand/policy/health_care_resources.pdf [29 May 2012].

11. Al-Khatib, S, Hellkamp, A, Curtis, J, et al. Non-evidence-based ICD implantations in the United States. JAMA. 2011; 305:43–49.

12. Wennberg, J, Fisher, E, Skinner, J. Geography and the debate over Medicare reform. Suppl web exclusive. Health Aff (Millwood). 2002; W96–114.

13. Swensen, S, Kaplan, G, Meyer, G, et al. Controlling healthcare costs by removing waste: what American doctors can do now. BMJ Qual Saf. 2011; 20:534–537.

14. Marshall, M, Ovretveit, J. Can we save money by improving quality? BMJ Qual Saf. 2011; 20:293–296.

15. Aarons, G. Measuring provider attitudes toward evidence-based practice: consideration of organisational context and individual differences. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2005; 14:255–271.

16. Glisson, C, James, L. The cross-level effects of culture and climate in human service teams. J Organ Behav. 2002; 23:767–794.

17. Sirio, C, Segel, K, Keyser, D, et al. Pittsburgh regional healthcare initiative: a systems approach for achieving perfect patient care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2003; 22:157–165.

18. Lukas, C, Holmes, S, Cohen, A, et al. Transformational change in health care systems: an organizational model. Health Care Manage Rev. 2007; 32:309–320.

19. Aarons, G. Transformational and transactional leadership: association with attitudes toward evidence-based practice. Psychiatr Serv. 2006; 57:1162–1169.

20. Bradley, E, Webster, T, Baker, D, et al. Translating research into practice: speeding the adoption of innovative health care programs. Issue Brief (Commonw Fund). 2004; 724:1–12.

21. Jung, D. Transformational and transactional leadership and their effects on creativity in groups. Creat Res J. 2001; 13:185–195.

22. Caldwell, E, Whitehead, M, Fleming, J, et al. Evidence-based practice in everyday clinical practice: strategies for change in a tertiary occupational therapy department. Aust Occup Ther J. 2008; 55:79–84.

23. Lucas, B, Evans, A, Reilly, B, et al. The impact of evidence on physicians’ inpatient treatment decisions. J Gen Intern Med. 2004; 19:402–409.

24. Davidoff, F, Miglus, J. Delivering clinical evidence where it's needed: building an information system worthy of the profession. JAMA. 2011; 305:1906–1907.

25. Brassey, J, Elwyn, G, Price, C, et al. Just in time information for clinicians: a questionnaire evaluation of the ATTRACT project. BMJ. 2001; 322:529–530.

26. Del Mar, C, Silagy, C, Glasziou, P, et al. Feasibility of an evidence-based literature search service for general practitioners. Med J Aust. 2001; 175:134–137.

27. McGowan, J, Hogg, W, Campbell, C, et al. Just-in-time information improved decision-making in primary care: a randomised controlled trial. PLoS ONE. 2008; 3:e3785.

28. McGowan, J, Hogg, W, Zhong, J, et al. A cost–consequences analysis of a primary care librarian question and answering service. PLoS ONE. 2012; 7:e33837.

29. Kawamoto, K, Houlihan, C, Balas, E, et al. Improving clinical practice using clinical decision support systems: a systematic review of trials to identify features critical to success. BMJ. 2005; 330:765.

30. McCord, G, Smucker, W, Selius, B, et al. Answering questions at the point of care: do residents practice EBM or manage information sources? Acad Med. 2007; 82:298–303.

31. Lindquist, A, Johansson, P, Petersson, G, et al. The use of the Personal Digital Assistant (PDA) among personnel and students in health care: a review. J Med Internet Res. 2008; 10:e31.

32. Westbrook, J, Coiera, E, Gosling, A. Do online information retrieval systems help experienced health professionals answer clinical questions? J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2005; 12:315–321.

33. Coomarasamy, A, Khan, K. What is the evidence that postgraduate teaching in evidence-based medicine changes anything? A systematic review. BMJ. 2004; 329:1017.

34. Straus, S, Ball, C, Balcombe, N, et al. Teaching evidence-based medicine skills can change practice in a community hospital. J Gen Intern Med. 2005; 20:340–343.

35. Murad, M, Montori, V, Kunz, R, et al. How to teach evidence-based medicine to teachers: reflections from a workshop experience. J Eval Clin Pract. 2009; 15:1205–1207.

36. Menon, A, Korner-Bitensky, N, Kastner, M, et al. Strategies for rehabilitation professionals to move evidence-based knowledge into practice: a systematic review. J Rehabil Med. 2009; 41:1024–1032.

37. Slawson, D, Shaughnessy, A. Teaching evidence-based medicine: should we be teaching information management instead? Acad Med. 2005; 80:685–689.

38. Glasziou, P. ACP Journal Club. Applying evidence: what's the next action? Ann Intern Med. 2009; 150:JC1–JC2. [JC1–3].

39. Scott, I, Phelps, G. Measurement for improvement: getting one to follow the other. Intern Med J. 2009; 39:347–351.

40. Glasziou, P, Ogrinc, G, Goodman, S. Can evidence-based medicine and clinical quality improvement learn from each other? BMJ Qual Saf. 2011; 20(Suppl 1):i13–i17.

41. Evans, S, Scott, I, Johnson, N, et al. Development of clinical-quality registries in Australia: the way forward. Med J Aust. 2011; 194:360–363.

42. Scott, I, Denaro, C, Bennett, C, et al. Achieving better in-hospital and post-hospital care of patients recently admitted with acute cardiac disease. for the Brisbane Cardiac Consortium Leadership Group. Med J Aust. 2004; 180:S83–S88.

43. Scott, I, Darwin, I, Harvey, K, et al. Multisite, quality-improvement collaboration to optimise cardiac care in Queensland public hospitals. Med J Aust. 2004; 180:392–397.

44. Schouten, L, Hulscher, M, van Everdingen, J, et al. Evidence for the impact of quality improvement collaboratives: systematic review. BMJ. 2008; 336:1491–1494.

45. Scott, I, Guyatt, G. Clinical practice guidelines: the need for greater transparency in formulating recommendations. Med J Aust. 2011; 195:29–33.

46. Bradley, E, Holmboe, E, Mattera, J, et al. Data feedback efforts in quality improvement: lessons learned from US hospitals. Qual Saf Health Care. 2004; 13:26–31.

47. Beer, M, Eisenstat, R, Spector, B. Why change programs don't produce change. Harv Bus Rev. 1990; 68:158–166.

48. Kizer, K. The ‘new VA’: a national laboratory for health care quality management. Am J Med Qual. 1999; 14:3–20.

49. Demakis, J, McQueen, L, Kizer, K, et al. Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (QUERI): a collaboration between research and clinical practice. Med Care. 2000; 38(Suppl 1):I-17–25.

50. Jha, A, Perlin, J, Kizer, K, et al. Effect of the transformation of the Veterans Affairs health care system on the quality of care. N Engl J Med. 2003; 348:2218–2227.

51. Schilling, L, Dearing, J, Staley, P, et al. Kaiser Permanente's performance improvement system, part 4: creating a learning organization. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2011; 37:532–543.

52. Schilling, L, Deas, D, Jedlinsky, M, et al. Kaiser Permanente's performance improvement system, part 2: developing a value framework. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2010; 36:552–560.

53. James, B, Savitz, L. How Intermountain trimmed health care costs through robust quality improvement efforts. Health Aff (Millwood). 2011; 30:1185–1191.

54. Wagner, E, Austin, B, Davis, C, et al. Improving chronic illness care: translating evidence into action. Health Aff (Millwood). 2001; 20:64–78.

55. Coleman, K, Austin, B, Brach, C, et al. Evidence on the Chronic Care Model in the new millennium. Health Aff (Millwood). 2009; 28:75–85.

56. Oman, K, Duran, C, Fink, R. Evidence-based policy and procedures: an algorithm for success. J Nurs Admin. 2008; 38:47–51.

57. Wensing, M, Wollersheim, H, Grol, R. Organisational interventions to implement improvements in patient care: a structured review of reviews. Implement Sci. 2006; 1:2.

58. Lukas, C, Engle, R, Holmes, S, et al. Strengthening organisations to implement evidence-based clinical practices. Health Care Manage Rev. 2010; 35:235–245.

59. Powell, B, McMillen, J, Proctor, E, et al. A compilation of strategies for implementing clinical innovations in health and mental health. Med Care Res Rev. 2012; 69:123–157.