CHAPTER 10 Patient safety, risk management, and documentation

Asuccessful risk management program can be divided into two key components: 1) avoiding preventable adverse outcomes, thereby decreasing the risk of litigation; and 2) managing liability exposure following an adverse outcome (preventable or unpreventable).69 Patient safety initiatives in perinatal care have been successfully implemented both in the United States and abroad, and have demonstrated significant decreases in perinatal morbidity and mortality related to intrapartum asphyxia, low Apgar scores, hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy, and suboptimal obstetric care.12,21,42,74,77 Patient safety programs tend to share some common themes, including a human factors approach to error, standardization of clinical practice, and emphasis on a team approach that places high value on communication. The focus of this chapter is to provide some understanding of human error; to identify sources of potential errors related to perinatal care and more specifically, electronic fetal monitoring (EFM); to suggest strategies that may prevent or reduce errors; and to review approaches to assessment, communication, and documentation that promote optimal outcomes. Documentation issues specific to electronic fetal monitoring and related medical-legal concerns are also addressed.

Occurrence of errors

In 2000, the Institute of Medicine29 published To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System, a report that brought national attention to statistics identifying medical errors as a significant cause of patient death or injury. Although progress has been made, errors in obstetrics continue to result in preventable morbidity and mortality, both maternal and neonatal.55 The Institute of Medicine report29 advocated a shift, when patient injuries occur, from the old paradigm of “blame and train” to identifying underlying system failures that have contributed to the preventable adverse outcome.

Through the efforts of the Joint Commission for the Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (The Joint Commission), the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, and other organizations engaged in quality improvement in health care, patient safety has been established as the first priority in health care. The analysis of large numbers of injuries and reported errors confirms that adverse events most often result from error-prone systems and processes, not from error-prone individuals. Organizations must learn to avoid the “conspiracy of silence” and create systems where errors can be identified and prevention strategies can be developed.18,20

Human error

Health care providers are educated and socialized to “do the right thing”—that is, to provide safe and appropriate care that results in a positive outcome. However, all health care providers are human, and humans make errors. Error is a normal part of the human experience and does not reflect laziness, bad intentions, or a personality defect.58 Understanding the nature of human errors (human factor analysis) is essential to any effort to prevent them.

The most common types of human error are related to slips, trips, and lapses,58 which occur throughout a wide range of human activity. The following lists these activities in decreasing order of probability of occurrence:52,66

Human errors are more likely to occur in the presence of personal and environmental factors known to increase the risk of error. Specific conditions have been identified that are known to increase the risk of error, and it is helpful to be aware of them. These conditions, listed in decreasing probability of risk of error, include the following:58,66,76

Being aware of the most common types of errors and error-producing conditions helps in identifying, reducing, and managing risks in the perinatal setting. It is also helpful to understand human performance as it relates to knowledge, application of rules, and skills. For example, nurses function from a specialized knowledge base. As they become more skilled and experienced, they process information rapidly in recurrent activities and perform many duties automatically.57

Skill-based performance includes starting a routine intravenous line, applying the external fetal monitor, and performing Leopold’s maneuvers. Errors can occur when nurses’ routines change or their attention is diverted, or from physiologic (fatigue, illness), psychologic (stress, family issues, frustration), or environmental (noise or unusual unit activity) factors.

Rule-based performance requires extra attention when an event differs from the routine. For example, when confronted with a commonly occurring problem, such as onset of fetal heart rate (FHR) variable decelerations, experienced nurses operate from known and practiced rules or a series of learned responses for doing X when Y happens. When an unfamiliar problem arises, a rule-based error may occur because the wrong rule is chosen, the situation is not accurately perceived, or the rule is misapplied.57

Knowledge-based performance requires controlled and conscious thought when nurses encounter a completely new, unfamiliar, or infrequently occurring situation. Examples of this type of situation are acute uterine rupture, development of a rarely seen sinusoidal fetal heart rate pattern, unheralded prolonged fetal heart rate deceleration to 60 beats per minute or less, or maternal seizure in the absence of a known seizure-related condition. Errors can occur because of lack of information or data, or from misdirected attempts to match this novel situation to previous and more familiar situations. As the expertise of the nurse increases, the focus of control moves from a knowledge-based and rule-based performance to skill-based functions. What was once novel has become routine and the nurse does not usually have to resort to knowledge-based reasoning.57

In summary, not all errors are preventable. And although humans do err, errors do not always result in injury or adverse outcomes, and not all adverse outcomes are the result of error.57 It is unreasonable to presume that any one individual is the only person responsible for an error that results in injury to a patient. It is inappropriate to rely on prevention of error as the sole means of creating patient safety. Systems should be in place that will catch errors before they result in adverse outcomes; however, systems are subject to human and environmental variations. The role of risk management in the perinatal setting is twofold: (1) to reduce the probability that a given risk will result in a poor outcome, and (2) to recognize, mitigate, or minimize the consequences of the event rather than relying on prevention of error as the sole means of creating patient safety.62,69

Common errors in perinatal care

The most common errors leading to injury in perinatal care are as follows*:

Lack of accurate interpretation of fetal monitoring, resulting in lack of timely recognition of both antepartum and intrapartum fetal compromise

Lack of accurate interpretation of fetal monitoring, resulting in lack of timely recognition of both antepartum and intrapartum fetal compromise Delay in decision for, or initiation of, cesarean or operative vaginal delivery as indicated by fetal or maternal status

Delay in decision for, or initiation of, cesarean or operative vaginal delivery as indicated by fetal or maternal status Non-indicated use of induction or augmentation of labor; failure to discontinue uterine stimulants in the presence FHR changes; mismanagement of uterine stimulants resulting in excessive uterine activity

Non-indicated use of induction or augmentation of labor; failure to discontinue uterine stimulants in the presence FHR changes; mismanagement of uterine stimulants resulting in excessive uterine activityElectronic fetal monitoring continues to be an area that has great potential for error, in part due to the wide variance in electronic fetal monitoring education both between and among the disciplines of nursing, midwifery, and medicine.49 Electronic fetal monitoring interpretation issues have been linked to avoidable intrapartum fetal demise and “[have] become the dominant litigation theme internationally.”77 Clinicians are best served by advancing approaches to electronic fetal monitoring interpretation and management that are based on patient safety principles, such as the development of high-reliability perinatal units.

Prevention of errors and risk reduction

High-reliability perinatal units

Risk reduction and error prevention in perinatal care can be achieved when organizations direct their efforts to the avoidance of these common situations and foster high-reliability characteristics. High reliability is defined as the technical ability to operate technologically complex systems essentially without error over long periods of time. There are organizational characteristics and clinical practices that differentiate highly reliable perinatal units from those experiencing more error and injury. These organizations consider patient safety to be the first priority and have systems in place to prevent recognized sources of error and injury.

The primary characteristics of a high-reliability unit are as follows:36,48,60,61

Alarms can be called by anyone; hierarchy is minimized, rank is not an issue; anyone can challenge the status quo.

Alarms can be called by anyone; hierarchy is minimized, rank is not an issue; anyone can challenge the status quo. Jobs are designed for safety; there is minimal reliance on memory; protocols, checklists, and forcing functions are built into the system.

Jobs are designed for safety; there is minimal reliance on memory; protocols, checklists, and forcing functions are built into the system. Teams that are expected to work together (e.g., physicians, midwives, and nurses participating in the same advanced fetal monitoring workshops) are trained and educated together.

Teams that are expected to work together (e.g., physicians, midwives, and nurses participating in the same advanced fetal monitoring workshops) are trained and educated together. Multidisciplinary teams carry out drills for high-risk situations such as emergency cesarean deliveries.

Multidisciplinary teams carry out drills for high-risk situations such as emergency cesarean deliveries. The organization promotes the development of competencies and evaluates ongoing competence using a variety of learning techniques such as simulations, computer tutorials, and case studies in fetal monitoring.

The organization promotes the development of competencies and evaluates ongoing competence using a variety of learning techniques such as simulations, computer tutorials, and case studies in fetal monitoring.Knox and Simpson recently updated the concept of perinatal high reliability by discussing key concepts for patient safety initiatives. These include sensitivity to processes, avoidance of oversimplification when addressing failures, inclusion of near-miss analysis, and the importance of transparency in response to system failure.35 There are many tools and resources for promoting high reliability in perinatal care, and hospitals should explore a variety of methods to reach these goals. One approach to the development of high-reliability perinatal care is to consistently promote patient care within a model such as the Circle of Safety™.

Creating a circle of safety™

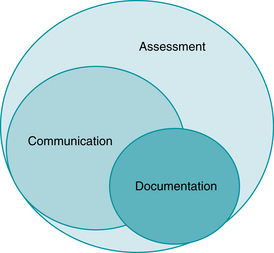

A concept developed to promote a systematic approach to patient safety in perinatal care is the Circle of Safety™. It consists of three main components: Clinical Comprehension, Communication, & Collaboration (Figure 10-1). Note that these three components are inextricably linked and all must be present to achieve patient safety.

Clinical Comprehension encompasses the knowledge base of the involved clinicians based on their training, education, and expertise in conjunction with specific individual patient information, such as risk factors and clinical context. It forms the foundation for safe patient care. If clinical comprehension is missing, both communication and collaboration will be adversely affected.

Clinical Comprehension encompasses the knowledge base of the involved clinicians based on their training, education, and expertise in conjunction with specific individual patient information, such as risk factors and clinical context. It forms the foundation for safe patient care. If clinical comprehension is missing, both communication and collaboration will be adversely affected. Communication refers to the ongoing dialogue between team members, including the patient and family members. Communication among clinicians may be based on a guide such as SBAR (situation, background, assessment, recommendation27,38) or the 5-step assertiveness46 script. Communication also includes discussions with the patient and family, such as informed consent, informed refusal, and disclosure. Appropriate communication is based on clinical knowledge and comprehension, which are the keys to effective collaboration. Samples of communication using SBAR and 5-step assertiveness in the perinatal setting are provided in Box 10-1 and Box 10-2. Hospital cultures that promote respectful conflict resolution and encourage direct communication experience improved nursing job satisfaction and a subsequent positive impact on both patient safety and evidence-based perinatal care.73

Communication refers to the ongoing dialogue between team members, including the patient and family members. Communication among clinicians may be based on a guide such as SBAR (situation, background, assessment, recommendation27,38) or the 5-step assertiveness46 script. Communication also includes discussions with the patient and family, such as informed consent, informed refusal, and disclosure. Appropriate communication is based on clinical knowledge and comprehension, which are the keys to effective collaboration. Samples of communication using SBAR and 5-step assertiveness in the perinatal setting are provided in Box 10-1 and Box 10-2. Hospital cultures that promote respectful conflict resolution and encourage direct communication experience improved nursing job satisfaction and a subsequent positive impact on both patient safety and evidence-based perinatal care.73 Collaboration occurs when clinicians form a plan of care that supports the patient and family and incorporates evidence-based practices and ongoing evaluation. Collaboration is a key process in achieving safety, often leading to new clinical comprehension regarding patient care and thus bringing the clinicians “full circle” in a safety-based approach.

Collaboration occurs when clinicians form a plan of care that supports the patient and family and incorporates evidence-based practices and ongoing evaluation. Collaboration is a key process in achieving safety, often leading to new clinical comprehension regarding patient care and thus bringing the clinicians “full circle” in a safety-based approach.

FIGURE 10-1 Schematic representation of the three elements of practice comprising the Circle of Safety™ approach: Clinical Comprehension, Communication, & Collaboration.

(Courtesy Perinatal Risk Management & Education Services, Chicago, IL.)

BOX 10-1 Sample Communication Related to Electronic Fetal Monitoring Using SBAR

Adapted from Leonard M, Graham S, Bonacrum D: The human factor: the critical importance of effective teamwork and communication in providing safe care. Qual Saf Health 13(Suppl 1):i85–i90, 2004; and Haig KM, Sutton S, Whittington J: SBAR: a shared mental model for improving communication between clinicians, Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf 32(3):167–175, 2006.

BOX 10-2 Sample Communication Related to Electronic Fetal Monitoring Using 5-Step Assertiveness

Adapted from Miller LA: Patient safety and teamwork in perinatal care, J Perinat Neonatal Nurs 19(1):46–51, 2005.

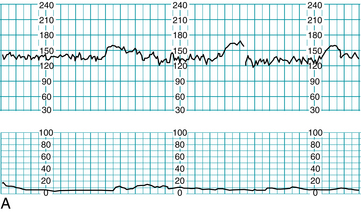

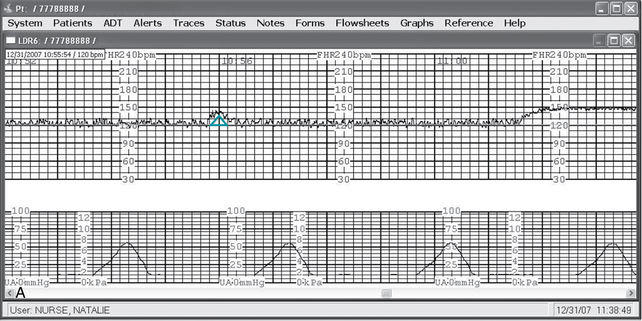

A case management illustration using the principles of clinical comprehension, communication, and collaboration outlined above can be found in Figure 10-2. In this case, a 24-year-old Gravida 2, Para 1 with a normal prenatal course and no risk factors had been ambulating in active labor following a normal electronic fetal monitoring tracing (Figure 10-2A). She was being followed by a certified nurse-midwife (CNM) who was on the labor and delivery unit. Returning to the room for reapplication of electronic fetal monitoring, the registered nurse (RN) had difficulty obtaining the fetal heart rate. This was noted on the central monitor by another registered nurse, who notified the certified nurse-midwife, and both went immediately to the labor room to assess and offer assistance (Figure 10-2B). A fetal heart rate below normal was audible, and the certified nurse-midwife performed a vaginal exam, artificially ruptured membranes (revealing approximately 2 cups of bright red bloody fluid), and applied a fetal scalp electrode.

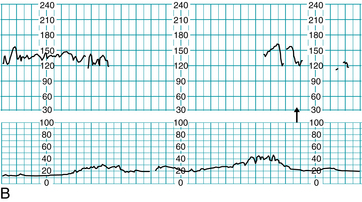

FIGURE 10-2 Application of the three principles of the Circle of Safety™ approach. A. FHR tracing prior to ambulation, all components normal. B. RN at desk notes irregularity on central display (arrow), notifies CNM, and both respond by going to labor room. C. First arrow: FHR audibly noted below normal, artificial rupture of membranes reveals bloody fluid, FSE placed and intrauterine resuscitation is begun. Second arrow: CNM decision to move patient to operating suite, team notified to assemble.

(Courtesy Perinatal Risk Management & Education Services, Chicago, IL.)

Bradycardia was noted and intrauterine resuscitation was begun (Figure 10-2C). The certified nurse-midwife called for the patient to be prepped and moved to the operating suite for probable cesarean delivery. She also asked for the physician and other support staff to be notified, including the pediatric/neonatal resuscitation team. Throughout the process the patient and family were apprised of the situation and given clear instructions and information as to the plan of action. The physician met the team in the operating suite and was given a quick report by the certified nurse-midwife. At this juncture, it was noted that although anesthesia had been paged and had responded, they had not yet arrived. The fetal heart rate remained bradycardic with absent variability, and the frank vaginal bleeding had continued. A second page to anesthesia was requested, and the certified nurse-midwife suggested use of local anesthesia should the anesthesiologist not arrive within the next 30 seconds. The physician agreed, but anesthesia arrived prior to the time limit and the patient was given general anesthesia. The infant was delivered and resuscitated successfully, resulting in Apgar scores of 6 and 9. Cord gases revealed metabolic acidosis in the umbilical artery, with only a respiratory acidosis in the umbilical vein, findings consistent with a short duration insult. Placental examination revealed an abruption of approximately 40%, confirmed by pathology studies. The time from the certified nurse-midwife deciding to move the patient to the operating suite to the actual delivery of the infant was nine minutes.

This case exemplifies the Circle of Safety™ methodology. The bedside team (registered nurses and certified nurse-midwife) had the requisite clinical comprehension; that is, they recognized what was likely an abruption and the seriousness of fetal heart rate findings in context. Communication was direct and clear, with each team member understanding his or her role and responding quickly and professionally. Team collaboration was evident throughout the case, from the initial response of the registered nurse at the central display to the communication between the certified nurse-midwife and physician in the operating suite. Prior to this event, the hospital had completed multidisciplinary education in the areas of electronic fetal monitoring, emergency response, and teamwork and had a policy in place that encouraged nurses and certified nurse-midwives to anticipate the need for emergent delivery and move the patient without waiting for a physician to arrive at the bedside. Physicians had been trained to respond immediately and to meet the team in the operating suite where they could make the ultimate decision regarding delivery. This tactic allows significant delays to be avoided, while respecting the physician’s ultimate decision on mode of delivery.

Following the application of an ongoing Circle of Safety™ approach to a specific situation encourages clinicians to constantly review and reformulate management plans in light of a changing clinical context. It recognizes the importance of a team approach, with clear communication among clinicians, as well as among patients, family members, and clinicians, and underscores the importance of creating a well-defined plan and re-evaluating the plan as labor progresses. When the plan is followed with regard to fetal heart rate tracing evaluation, it fits seamlessly with the standardized management decision model presented in Chapter 6.

Guidelines to promote safety and reduce risks

Recommendations and guidelines to promote patient safety and to decrease risk exposure include the following:9,11,19,31,62,69

Policies, procedures, and protocols

Create departmental policies (vs. nursing policies) for areas of practice that are interdisciplinary by nature (EFM, labor induction/augmentation) and attempt to standardize care whenever possible.

Create departmental policies (vs. nursing policies) for areas of practice that are interdisciplinary by nature (EFM, labor induction/augmentation) and attempt to standardize care whenever possible. Use guidelines promulgated by professional organizations (e.g., Association of Women’s Health, Obstetric and Neonatal Nurses, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists), journals, textbooks, and particularly evidence-based practice reports as sources for developing policies, procedures, and protocols.31

Use guidelines promulgated by professional organizations (e.g., Association of Women’s Health, Obstetric and Neonatal Nurses, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists), journals, textbooks, and particularly evidence-based practice reports as sources for developing policies, procedures, and protocols.31Competency

Verify nurses’ qualifications at the time of hire to ensure that they meet the prerequisites of the institution.

Verify nurses’ qualifications at the time of hire to ensure that they meet the prerequisites of the institution. Develop tools to evaluate performance related to specific skills, knowledge base of physiology and pathophysiology, and the standard of care to which nurses are held accountable, based on the facility’s rules (i.e., policies, procedures, and protocols).45

Develop tools to evaluate performance related to specific skills, knowledge base of physiology and pathophysiology, and the standard of care to which nurses are held accountable, based on the facility’s rules (i.e., policies, procedures, and protocols).45Fetal monitoring

Implement intrauterine resuscitation techniques appropriately; have reminders (printed or electronic) available for clinicians at bedside.

Implement intrauterine resuscitation techniques appropriately; have reminders (printed or electronic) available for clinicians at bedside. Communicate findings and efforts to correct FHR changes to physician or midwife in a clear and unambiguous manner using SBAR27,38 or 5-step assertiveness.47

Communicate findings and efforts to correct FHR changes to physician or midwife in a clear and unambiguous manner using SBAR27,38 or 5-step assertiveness.47 Continue fetal assessment until birth, including monitoring until the abdominal preparation is begun on women who are having a cesarean delivery.1

Continue fetal assessment until birth, including monitoring until the abdominal preparation is begun on women who are having a cesarean delivery.1Neonatal resuscitation

Organizational resources and systems to support timely interventions

Have sufficient staff or be able to redeploy staff as needed. During the intrapartum period, the nurse-to-patient ratio should be 1:2 or 1:1, depending on the stage of labor and the complexity of the situation.1,9,10 Staffing should be sufficient to begin a cesarean delivery within 30 minutes of a physician’s decision to operate. A more expeditious delivery (<30 minutes) may be necessary in cases of abruptio placentae, prolapse of the umbilical cord, hemorrhage secondary to placenta previa, and uterine rupture.1

Have sufficient staff or be able to redeploy staff as needed. During the intrapartum period, the nurse-to-patient ratio should be 1:2 or 1:1, depending on the stage of labor and the complexity of the situation.1,9,10 Staffing should be sufficient to begin a cesarean delivery within 30 minutes of a physician’s decision to operate. A more expeditious delivery (<30 minutes) may be necessary in cases of abruptio placentae, prolapse of the umbilical cord, hemorrhage secondary to placenta previa, and uterine rupture.1 Utilize a perinatal patient safety nurse, a full-time position in nursing dedicated to implementation and evaluation of all perinatal safety activities for the institution.53

Utilize a perinatal patient safety nurse, a full-time position in nursing dedicated to implementation and evaluation of all perinatal safety activities for the institution.53 Have systems in place that ensure a physician’s timely response to the perinatal unit when needed and requested (e.g., in cases of an abnormal FHR tracing, excessive uterine activity or tachysystole, complications during vaginal birth after cesarean delivery). A policy that exists in high-reliability perinatal units is that “a physician will come to the unit when requested by a nurse” (Box 10-3).36

Have systems in place that ensure a physician’s timely response to the perinatal unit when needed and requested (e.g., in cases of an abnormal FHR tracing, excessive uterine activity or tachysystole, complications during vaginal birth after cesarean delivery). A policy that exists in high-reliability perinatal units is that “a physician will come to the unit when requested by a nurse” (Box 10-3).36 Consider use of a hospitalist or laborist to ensure a physician is immediately available to labor & delivery.50

Consider use of a hospitalist or laborist to ensure a physician is immediately available to labor & delivery.50BOX 10-3 Elements of Promoting Safety and Reducing Risk

Perinatal teamwork: collaboration and communication

Recognize multidisciplinary teams as the unifying principle that creates operational excellence and success. “In any situation requiring a real-time combination of multiple skills, experiences and judgment, teams, as opposed to individuals, create superior performance.”68

Recognize multidisciplinary teams as the unifying principle that creates operational excellence and success. “In any situation requiring a real-time combination of multiple skills, experiences and judgment, teams, as opposed to individuals, create superior performance.”68 Engage in team building through a multidisciplinary clinical practice or performance improvement committee to come to consensus on both routine and problematic practices, to improve communication, to build trust and confidence in one another, and to achieve performance goals.68

Engage in team building through a multidisciplinary clinical practice or performance improvement committee to come to consensus on both routine and problematic practices, to improve communication, to build trust and confidence in one another, and to achieve performance goals.68 Create a culture in which everyone feels free to ask for help,28,75 and questions are not viewed as challenges to authority.39

Create a culture in which everyone feels free to ask for help,28,75 and questions are not viewed as challenges to authority.39 Implement strict policies on disruptive behavior for all disciplines, and provide education on effective and respectful interaction.32,63

Implement strict policies on disruptive behavior for all disciplines, and provide education on effective and respectful interaction.32,63Interdisciplinary case reviews

Use a proactive approach, such as “failure to rescue”64 to review processes related to EFM management. This approach does not require a sentinel event to trigger a review and allows hospitals to develop best-practice strategies as well as evaluate “near misses.”

Use a proactive approach, such as “failure to rescue”64 to review processes related to EFM management. This approach does not require a sentinel event to trigger a review and allows hospitals to develop best-practice strategies as well as evaluate “near misses.” Engage several reviewers from a variety of disciplines when reviewing and classifying adverse events.22

Engage several reviewers from a variety of disciplines when reviewing and classifying adverse events.22Chain of communication

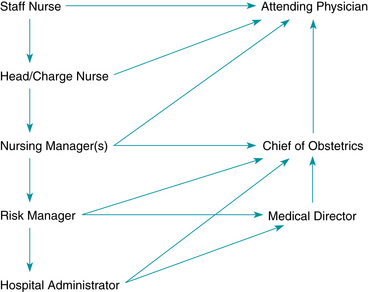

Develop a chain of communication (Figure 10-3) with key medical, nursing, administrative, and risk-management leaders.

Develop a chain of communication (Figure 10-3) with key medical, nursing, administrative, and risk-management leaders. Implement the chain of communication when team members disagree (e.g., about tracing interpretation or management of the patient) or when the clinicians fail to respond.25

Implement the chain of communication when team members disagree (e.g., about tracing interpretation or management of the patient) or when the clinicians fail to respond.25 Report to the quality/performance improvement committee any incidence of provider behavior that does not support quality or safe patient care, that increases risk to the patient, or that could contribute to an adverse outcome. If retaliation or retribution occurs, it should be reported as well. “When people fail to engage in respectful interactions, things can get dangerous.”36

Report to the quality/performance improvement committee any incidence of provider behavior that does not support quality or safe patient care, that increases risk to the patient, or that could contribute to an adverse outcome. If retaliation or retribution occurs, it should be reported as well. “When people fail to engage in respectful interactions, things can get dangerous.”36Joint nurse/provider education

Make EFM education a multidisciplinary event and teach all clinicians the standard management decision model presented in Chapter 6.

Make EFM education a multidisciplinary event and teach all clinicians the standard management decision model presented in Chapter 6.Management of risks and adverse outcomes

When there is litigation related to an adverse neonatal or maternal outcome, the physician, midwife, hospital, and, often, individual perinatal nurses are named as defendants.70 Health care providers by nature and education want to help and care for people, so they are particularly devastated when they are sued by a client. The word malpractice evokes a strongly negative response in all health care providers, particularly in obstetrics where the damages are likely catastrophic with economic damages in the millions. Care providers fear being involved in malpractice suits and judged by a jury as liable in a situation where the care was, in fact, reasonable. They are likely to become preoccupied, as unresolved lawsuits can take 3 or more years to be resolved.56 But medical errors and litigation are a reality of practice. Acknowledging the risk and developing systems to reduce the risk and/or consequence of error is the first step in reducing medical-legal exposure. When risk issues or adverse outcomes are identified, the woman’s medical record should be reviewed by the multidisciplinary health care team, utilizing an approach that will objectively analyze the clinical course to identify errors and contributing factors that may have resulted in an adverse outcome. Additionally, disclosure of adverse or unanticipated events to the patient and family is the responsibility of the health care team and may result in a reduction in legal action.3

Disclosure of unanticipated outcomes

When an injury occurs, the Joint Commission standards require that information about how the error occurred and remedies available be disclosed to the woman and her family.30 During disclosure, the woman and her family should be informed that the factors involved in the injury will be investigated so that steps can be taken to reduce the likelihood of similar injury to other patients.51 Disclosure should be made with the support of trained individuals; clinicians should refrain from discussing the details of the event with the patient and family without appropriate support through the organization’s disclosure process. Institutions should provide education related to the components of disclosure, and several organizations have developed disclosure programs that can serve as models for disclosure in the perinatal setting.23

Elements of malpractice

Failure to do something that a reasonable and prudent clinician would do in the same circumstances is known as malpractice or professional negligence. Clinicians are held to national standards of care and practice within the “same or similar circumstances” and “reasonably expected” parameters. Inherent in this statement is the expectation that the clinician is knowledgeable about the standards of care and is fully competent to apply those standards when caring for patients.41

Negligence is the failure to act in the required manner, causing harm to an individual. Malpractice is an unintentional act performed by a professional acting in a professional capacity that causes harm to an individual. Under the rule respondeat superior” let the master answer,” an employer is held liable for acts of malpractice committed by an employee while performing duties for which she or he was hired.

For an action to fit the legal definition of malpractice, the following four elements must be met:

Notification and clinical review

When there is error, injury, or other adverse outcome, there should be written and well-understood procedures to guide staff. Notification of supervisory or management-level individuals should be timely, according to organizational policy. Appropriate quality assurance memos or incident reports should be completed for performance improvement purposes. The medical record should contain documentation of the facts surrounding the event and should be free from editorial commentary and potentially damaging, biased, or blaming comments.

When an adverse outcome occurs, the entire perinatal unit is usually aware of the event. There is great interest in finding out what happened, and the staff sincerely wants to support the team members involved by reviewing the event in detail. However, chart review and questions in the absence of a “need to know” basis must be avoided. Any discussions occurring outside an official quality improvement or risk management forum will be discoverable in the event of litigation and can be required to be repeated under oath. Perinatal care providers should be knowledgeable about the appropriate time and place to discuss events, and they should be compliant with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) regulations regarding protected patient information.

A critical incident debriefing by a skilled resource, such as an employee assistance program, a trained hospital-based team, a social worker, or a chaplain, provides an opportunity for staff to process feelings and concerns related to adverse outcomes and patient injuries in an environment free from discovery and blame. The critical incident debriefing is most effective when conducted as soon as possible after the occurrence of the event.

In the event of litigation, a plaintiff’s attorney may attempt to make direct contact with nurses involved in the care of the allegedly injured patient. Hospital or unit orientation should include information about the correct response to such a request (refusal to discuss) and the requirement that the hospital’s risk management department be notified and involved before any discussion with a plaintiff’s attorney occurs (Box 10-4).

Reporting of sentinel events

Adverse events that meet the definition of a sentinel event (i.e., an unexpected occurrence involving death or serious physical or psychologic injury, or the risk thereof) must be reported according to the Joint Commission and state department of health standards. A sentinel event signals the need for immediate investigation and response. The Joint Commission specifically lists “any intrapartum maternal death and any perinatal death unrelated to a congenital condition in an infant with birthweight >2500 grams” as voluntarily reportable events.30 Following the report of a sentinel event, the organization must conduct a root-cause analysis and report the findings of that process to the Joint Commission. The root-cause analysis identifies causal factors for the sentinel event and improvements in processes or systems that would decrease the likelihood of such events in the future. Root-cause analysis follows an event and focuses primarily on systems and processes, not individual performance.

Documentation

The medical record and the terms utilized therein will be what attorneys, claim representatives, and reviewing expert physicians pre-judge. The accuracy of terms and the consistency of terminology among providers will weigh in judging not only the competency but also the credibility of providers. In cases involving electronic fetal monitoring, clinician’s use of the correct terminology in documentation as well as in communications under oath, such as deposition or trial testimony, can play a significant role in the outcome of litigation.46

To reduce risk, appropriate documentation must be kept, including the frequency of, content reviewed, and nomenclature utilized for fetal heart rate evaluation. Providers must know, understand, and utilize institutional policies, guidelines, and resources in the delivery of appropriate care and documentation. These documents will form either the shield of the provider’s defense or serve as a sword for the plaintiff’s case.

Documentation in the patient’s record is used to describe care and interventions provided in a sequential manner. This information may be stored or archived on an optical disk or other device (Figure 10-4). Increasing evidence indicates that documentation should be done only once, on the paper labor flow sheet or in the electronic record, to avoid duplication.34Duplicative charting presents a significant risk of inconsistencies that can be questioned or challenged by plaintiff attorneys in the event of future litigation. Furthermore, duplicative documentation in the medical record and on the fetal monitor strip is unnecessarily labor intensive for nurses who are frequently fully occupied in care of the woman and fetus.

FIGURE 10-4 Corometrics 250cx Maternal/Fetal Monitor. The fetal strip and vital signs automatically flow to an electronic medical record, providing a backup or an alternative to the storage of paper FHR tracings.

(Courtesy GE Medical Systems Information Technologies, Milwaukee, WI.)

To fully understand documentation issues in electronic fetal monitoring, the clinician must understand the difference between assessment, communication, and documentation (Figure 10-5). These are three distinct components of patient care, yet many nursing protocols fail to recognize the difference among these components, resulting in difficulty in compliance with documentation policies and excessive amounts of nursing time spent “nursing the chart” rather than providing patient care. A brief review is warranted here.

FIGURE 10-5 Illustration of the relationship between assessment, communication, and documentation in daily clinical practice.

(Courtesy Lisa A. Miller, CNM, JD.)

Components of care: assessment, communication, documentation

Assessment, the evaluation of patient status, is constant, ongoing, and very detailed. Clinicians notice many things about patients, not all of which are sufficiently clinically relevant to warrant communication or documentation. Indeed, much of what a nurse assesses and many activities a nurse performs are never communicated to other providers nor do they appear in the medical record. Examples include the act of introducing oneself to the patient and family, changing a soiled gown or sheet, or simply offering support or encouragement to the patient and her family. Thus the oft-quoted adage “if it wasn’t charted, it wasn’t done” has never been and will never be true. Yet many clinicians readily agree with this statement when being deposed in relation to a malpractice suit. The reality is, there is absolutely no rationale, and it would not be physically possible, to either communicate or document all the assessments and activities of any clinician, whether nurse, midwife, or physician. Assessment is simply too broad a category.

Communication is slightly less broad but still encompasses more than any clinician can, or needs, to document. Much communication in labor and delivery is routine, consisting of sharing information or giving instructions to patients and family members. It may include notification of the charge nurse or team leader regarding status changes or patient updates, not all of which needs to be placed in the medical record. Notification of the midwife or physician regarding labor progress and fetal status may be quite detailed, but could be documented simply as “Provider updated as to patient status.” There is no requirement, and it would not be effective use of a clinician’s time, to document verbatim each and every conversation that occurs over the course of labor and birth.

Documentation, therefore, is the least broad of the three categories, and yet it is often the most important in relation to litigation. Evidence is presented in the courtroom in the form of exhibits or testimony. The primary exhibit in a malpractice case is the medical record. Accordingly, an accurate, contemporaneous record is the foundation of either the plaintiff or defense case.

The best evidentiary friend of a plaintiff attorney is either inaccurate or inconsistent documentation of the care provided. Inaccurate documentation can stem from a competency issue, for example, where a fetal heart rate tracing is not appropriately interpreted, or from inaccurate nomenclature, such as what is present on the tracing. In either situation, the health care provider is left with a narrative note or deposition testimony which is inconsistent with the objective evidence on the tracing. Inconsistencies within a courtroom do not favor the inconsistent party.

Conflicting or contradictory documentation and use of nomenclature create difficulties for clinicians in both the screening and testimonial phases of malpractice litigation. When a file is being initially reviewed by plaintiff’s counsel to determine whether or not medical malpractice may have occurred, the medical record is the only documentation available. The narrative note supplied will be read against subsequent health care providers’ notes and a fetal heart rate tracing. Accurate recognition and description of fetal heart rate assessments in the patient’s chart demonstrate attentive and competent care. Inaccurate or incorrect terminology in a medical record when read and compared with the objective fetal heart tracing increases the likelihood of litigation.

Compounding the matter further, inconsistent and inaccurate terminology also creates difficult obstacles later, during the testimonial phase of litigation. When a witness uses modified or non-standardized terminology, other health care providers and expert witnesses will not understand the full extent of what is meant. This creates unclear communication, which can result in medical errors or the appearance of errors within a medical record. This problem is exemplified by the following deposition excerpt.

Deposition excerpt

A physician (MD) was questioned in deposition by the plaintiff’s attorney (PA) regarding a nursing narrative note.

The narrative notes within the case included the nurse documenting variable decelerations with “late components.” Utilizing the outdated terminology “late components” created a scenario where the significance is undefined and suggests a call should have been made. Further testimony demonstrated that no information regarding this deceleration was relayed. The nurse testified as follows:

The inappropriate utilization of nomenclature has created a scenario where the physician has inadvertently criticized the nurse. Furthermore, the nurse must separate herself from her own charting of the word late. This makes the case more difficult to defend. With appropriate utilization of nomenclature, the nurse would have simply charted this was a variable deceleration, and could have answered that as it was not recurrent, it was her clinical judgment that it did not warrant immediate notification of the physician.

The utilization of standardized terminology not only supports the defense of a medical malpractice action, it more importantly allows the physician and nurse to communicate clearly and make certain they are accurately discussing the findings and placing the same significance on each term.

Documentation issues specific to electronic fetal monitoring

In 2008, the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) reviewed and updated the standardized definitions for use in the interpretation of fetal heart tracings and created a three-tier categorization system.40 Currently, all professional organizations in the U.S. support the use of standardized terminology.2,6,8 Unfortunately, despite the attempts at standardization of terminology, many health care providers have been slow to adapt. This creates the risk of inaccurate communication between health care providers who misuse terms, and it creates the potential for a medical record replete with inconsistencies.4

There are several documentation issues that relate specifically to electronic fetal monitoring. These include what should be included in electronic fetal monitoring documentation; definition and use of summary terms, such as FHR categories and use of normal/tachysystole for uterine activity; further quantification of decelerations, and the frequency of documentation versus the frequency of assessment in FHR tracing review. Each institution must address these issues and provide guidance for staff members. There are few absolutes for any of these issues and institutional approaches will naturally vary, but some general principles will provide a starting point for team discussion.

Components of electronic fetal monitoring evaluation

In addition to uterine activity, there are five components that should be included in evaluation of the fetal heart rate tracing4,41:

These five components form the basis of electronic fetal monitoring management and should be included in documentation related to the fetal heart rate tracing. If using a graphic flowsheet, the fifth component (changes or trends over time) is apparent by simple review of the flowsheet. However, when clinicians use narrative charting, as is the case for most doctors and midwives, changes or trends over time may need to be specifically identified. In addition to the five fetal heart rate components, documentation should include uterine activity and mode of assessment (external or internal).

Use of fetal heart rate categories

The 2008 NICHD workshop report introduced a three-tiered category system to replace the use of poorly defined summary terms, such as reassuring and nonreassuring, when classifying and discussing FHR tracings. For purposes of documentation, it is preferable that clinicians document the components of the FHR tracing rather than the category. Should a FHR tracing be lost or an electronic archival system fail, the clinician who documented the FHR components can always determine what the corresponding category was at the time in question, but the reverse is not true. The clinician who simply documents a category will not be able to later articulate the FHR components if the tracing is unavailable. Some institutions are requiring nurses chart both the FHR components and the FHR tracing category, which is not only unnecessary but counterproductive, considering the already burdensome paperwork responsibilities of the bedside nurse.46 Clearly stated, FHR categories are summary terms that clinicians should know and be able to apply and articulate if queried; they are not required documentation components.

Documentation of uterine activity

Similar to the categories issue, clinicians should understand that the terms “normal” and “tachysystole” are summary terms used to describe uterine activity based on frequency of contractions over a 30-minute period. Clinicians are best served by documentation that provides a clear picture of uterine activity assessment as a whole, including frequency, duration, strength, and resting tone, the components of uterine activity (see Chapter 4). While summary terms can be helpful in drafting policies and procedures, they are limited in usefulness during deposition or trial, where clinicians are expected to be able to provide specific answers regarding patient assessment. There is no logical rationale for adding summary terms to documentation where documentation already includes the individual components assessed.

Quantification of decelerations

FHR decelerations may be further quantified by duration (onset to offset) and depth of nadir, but this is not mandatory.5,46 Clinicians should think logically about the benefits (or lack thereof) further quantification provides within the clinical context of FHR monitoring. Given that early decelerations are not associated with hypoxemia and considered clinically insignificant, further quantification of early decelerations does not seem clinically indicated or logical. Late decelerations reflect transient hypoxemia and warrant a clinical response regardless of depth, making further quantification moot. However, management of variable and prolonged decelerations may differ based on duration and depth of nadir, making it reasonable to further quantify these decelerations at least in communication with the team members, especially if the recipient of the communication does not have visual access to the fetal heart rate tracing. Communication is distinct from documentation and is often more detailed than what is documented in the medical record, as discussed above. Institutions will need to decide whether further quantification of decelerations is warranted in documentation practices, and if so, whether it is necessary for all deceleration types.

Frequency of electronic fetal monitoring assessment versus frequency of electronic fetal monitoring documentation

As discussed earlier in this chapter, assessment encompasses a clinical spectrum that is much larger than just documentation. Frequency of fetal heart rate tracing assessment may vary both by stage of labor as well as clinical context (antepartum vs. intrapartum, risk factors, previous fetal heart rate tracing, interventions). When utilizing electronic fetal monitoring, a continuous permanent record is created and is often archived electronically in addition to (or as an alternative to) an actual paper strip. Institutional protocols should be in place to delineate both the frequency of assessment of fetal heart rate tracings as well as the frequency of documentation regarding fetal heart rate findings. It is reasonable that fetal heart rate assessments may be more frequent than fetal heart rate documentation, in keeping with the reality of clinical practice.46 While a detailed discussion of perinatal documentation policies is beyond the scope of this book, all documentation policies related to electronic fetal monitoring should address the following:

The five components of FHR evaluation (baseline rate, baseline variability, presence of accelerations, periodic/episodic decelerations, changes/trends over time)

The five components of FHR evaluation (baseline rate, baseline variability, presence of accelerations, periodic/episodic decelerations, changes/trends over time)It is imperative that institutions create reasonable and rational policies regarding all three areas: assessment, communication, and documentation. While there is no one “right” way to accomplish this, the principles discussed above should serve as a starting point for clinicians, regardless of specialty. Documentation practices and policies will vary reasonably, based on type of system (computerized records vs. paper), style of charting (flowsheet vs. narrative), clinical context (labor evaluation vs. non-labor complaint), and numerous other factors. Regardless of the method or clinical context, clinicians can remember the important aspects of documentation by use of the simple acronym CLEAR45:

Logical - easily understood and clear; consider SOAP (subjective, objective, assessment, plan) for progress notes

Logical - easily understood and clear; consider SOAP (subjective, objective, assessment, plan) for progress notesIncorporating these concepts and addressing the key issues previously described will result in the development of sound, clinically realistic documentation policies that reflect interdisciplinary collaboration and patient care.

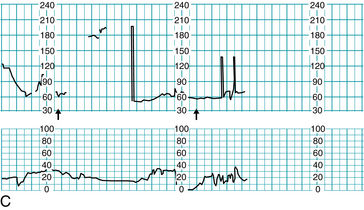

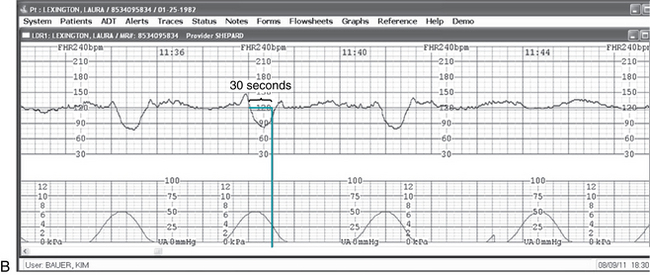

Electronic medical records and information systems

Computerized perinatal information systems are becoming more and more common as health care institutions strive to improve information flow and documentation practices. The options range from simple archiving of fetal heart rate tracings to completely integrated systems linking prenatal outpatient care to inpatient intrapartum and neonatal recordkeeping. Many systems offer remote viewing via computer intranet access, with at least one system offering data access, including real-time fetal heart rate tracing review, via mobile phone. Another system utilizes several onscreen tools that provide graphic overlays to help clinicians correctly apply the NICHD definitions and reach consensus regarding fetal heart rate tracing components (Figure 10-6). As compared to traditional paper records, computerized systems offer several benefits,43,72 including the following:

Automatic creation of notes and minimization of narrative/typing using preset scripts and drop-down menus

Automatic creation of notes and minimization of narrative/typing using preset scripts and drop-down menus Bedside access to protocols, policies, calculators, and other tools to improve or facilitate patient care

Bedside access to protocols, policies, calculators, and other tools to improve or facilitate patient care Facilitated data management and retrieval for reporting, statistics, and quality assurance activities

Facilitated data management and retrieval for reporting, statistics, and quality assurance activities

FIGURE 10-6 A. “E-tools” allow clinicians to confirm FHR finding based upon the NICHD terminology by overlaying them directly on the FHR tracing display on the computer. Pictured above is the Accel tool that identifies accelerations of the FHR. B. “E-tools” allow clinicians to confirm FHR finding based upon the NICHD terminology by overlaying them directly on the FHR tracing display on the computer. Pictured above is the Decel tool that helps evaluate the onset to nadir of decelerations as abrupt or gradual.

(Courtesy OBIX Perinatal System, Clinical Computer Systems, Inc., Elgin, IL.) (Courtesy OBIX Perinatal System, Clinical Computer Systems, Inc., Elgin, IL.)

While the popularity and acceptance of computerized perinatal information systems continues to grow, it is essential that institutions recognize the importance of appropriate training and an organized transition plan when moving from paper charting to electronic medical records. Setting a “go-live” date and providing adequate time for clinicians to become proficient with the system before that date are keys to a smooth transition. Having clinicians “double-chart” over a transition period is a poor strategy,34 replete with error potential and frustration for clinicians who are already burdened with documentation and administrative duties in addition to patient care.

Finally, it is important to note that computerized medical record systems vary with regard to transparency regarding documentation timing. Most systems provide the option to have medical record printouts that include keystroke data (i.e., the time the note was actually typed or entered) adjacent to the timing of the note. This information is sometimes referred to as the history or audit trail. When this information is included in the medical record printouts, the medical record is considered to be “transparent,” meaning that a reviewer is able to clearly see the actual time the notation was entered. Problems can arise when the medical record printout does not include this information and clinicians have entered data that would normally be considered a late entry but do not identify it as such. If the computer printout of the medical record gives the appearance of contemporaneous charting, but the audit trail or history reveals the actual time of the entry was hours or days after the notation time, it could be construed as a clinician’s attempt to “buff” the chart. This can result in allegations of spoliation in medical malpractice cases. Spoliation refers to the withholding or hiding of evidence in legal proceedings and could include additions to the medical record with the purpose of falsification to avoid liability. These allegations can be devastating to the defense of a medical malpractice suit. They are easily avoided by providing medical records that are transparent as to data entry and by setting reasonable standards for late entries and addendums to medical records.

Record storage and retrieval

The fetal monitor tracing is a part of the patient’s medical record; therefore, storage, security, and record retrieval are the responsibility of the hospital’s medical records department. If the paper strip is archived, each segment of the strip must be clearly identified per unit policy. The strips should be numbered sequentially and securely banded together for archiving. Confidentiality of the fetal monitor tracings must be maintained by storing them in a secure place until the woman’s entire medical record is sent to the medical records department. A process must be in place to request and reliably retrieve all fetal monitoring tracings, whether on paper, microfilm, or electronic archival. In the event of litigation, any missing monitoring information makes a case difficult (if not impossible) to defend despite excellent care and complete compliance with established standards.

Summary

A patient safety approach to risk management has been shown to improve outcomes and reduce liability, as well as improve safety climate and culture.16,26,53,74 System analysis of risk and error must replace outdated punitive approaches that use blame and focus on individual behavior/error. There are specific perinatal risk reduction strategies related to use of electronic fetal monitoring. An environment rich in competent care providers who practice as a team, use the same terminology, avoid variances in practice, and have systems in place for timely clinical intervention supports the likelihood of that organization being one of high reliability. Operating within a safety framework that includes ongoing clinical comprehension, communication, and collaboration improves patient care and reduces opportunity for error.

When formulating strategies and creating guidelines for patient care and documentation, clinicians and health systems must acknowledge and understand the difference between assessment, communication, and documentation. All these areas have potential for error, but an approach that respects the realities of clinical practice and makes patient safety the top priority serves both patients and clinicians. Documentation issues specific to electronic fetal monitoring must be addressed, and any terminology utilized must be clearly defined, understood, and used consistently by all team members. Information technology and computerized perinatal information systems can assist clinicians in meeting this challenge.

Finally, clinicians have a duty to disclose unanticipated outcomes. Disclosure should be accomplished by trained individuals and should include a discussion of any errors in an honest and forthright manner. Through the combination of a core philosophy of patient safety, collaborative care and teamwork, and direct and open disclosure practices, patients and families can be assured that health care systems are working successfully towards improved outcomes. And nurses, midwives, and doctors can effectively abide by the ancient wisdom of primum non nocere, “first do no harm.”

1. American Academy of Pediatrics, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Guidelines for perinatal care, ed 6. AAP, Washington, DC;ACOG: 2007

2. American College of Nurse-Midwives. Standard nomenclature for electronic fetal monitoring. Position Statement 2010. Silver Spring, MD: ACNM; 2010.

3. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Disclosure and discussion of adverse events. Committee Opinion no. 380. Washington, DC: ACOG; 2007.

4. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Inappropriate use of the terms fetal distress and birth asphyxia. Committee Opinion no. 197. Washington, DC: ACOG; 1998.

5. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists: Intrapartum fetal heart rate monitoring: nomenclature, interpretation, and general management principles. ACOG Practice Bulletin no. 106. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114:192-202

6. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Management of intrapartum fetal heart rate tracings, ACOG Practice Bulletin no. 116. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116:1232-1240.c.

7. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Umbilical cord blood gas and acid-base analysis. ACOG Committee Opinion. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108(5):1319-1322.

8. Association of Women’s Health, Obstetric and Neonatal Nurses. Fetal heart rate monitoring. Position Statement 2008. Available at www.awhonn.org/awhonn/content.do?name=05_HealthPolicyLegislation/5H_PositionStatements.htm, May 2, 2010. Accessed

9. Association of Women’s Health, Obstetric and Neonatal Nurses: Fetal heart monitoring.principles and practices, principles and practices. Dubuque, IA; Kendall Hunt: 2009

10. Association of Women’s Health, Obstetric and Neonatal Nurses. Guidelines for professional registered nurse staffing for perinatal units Washington DC;AWHONN: 2010.

11. Baker P. Medico-legal problems in obstetrics. Obstet Gynaecol Reproductive Med. 2009;19(9):253-256.

12. Becher J, Stenson B, Lyon A. Is intrapartum asphyxia preventable. BJOG. 2007;114(11):1442-1444.

13. Berkowitz RL: Of parachutes and patient care. a call to action. Am J Obstet Gynecol. E-pub ahead of print: Feb 1, 2011

14. Clark SL, Belfort MA, Byrum SL, et al: Improved outcomes, fewer cesarean deliveries, and reduced litigation: results of a new paradigm in patient safety. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199:105.e1-105.e7

15. Clark SL, Belfort MA, Dildy GA. Reducing obstetric litigation through alterations in practice patterns. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(6):1279-1283.

16. Clark SL, Meyers JA, Frye DK, et al. Patient safety in obstetrics-the Hospital Corporation of America experience. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;204(4):283-287.

17. Collins D. Multidisciplinary teamwork approach in labor and delivery and electronic fetal monitoring. J Perinat Neonatal Nurs. 2008;22:125-132.

18. Conway JB, Weingart SN: Organizational change in the face of highly public errors, I. the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute Experience. AHRQ Perspectives on Safety serial online: May 2005. Accessed. www.webmm.ahrq.gov/perspective.aspx?perspectiveID=3, October 29, 2007. from

19. Dickens BM, Cook RJ. The legal effects of fetal monitoring guidelines. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2010;108:170-173.

20. Downe S, Finlayson K, Fleming A. Creating a collaborative culture in maternity care. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2010;55(3):250-254.

21. Draycott T, Sibanda T, Owen L, et al. Does training in obstetric emergencies improve neonatal outcome. BJOG. 2006;113(2):177-182.

22. Forster AJ, O’Rourke K, Shojania KG, et al. Combining ratings from multiple physician reviewers helped to overcome the uncertainty associated with adverse event classification. J Clin Epidemiol. 2007;60(9):892-901.

23. Gallagher T, Studdert D, Levinson W. Disclosing harmful medical errors to patients. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(26):2713-2719.

24. Gennaro S, Mayberry LJ, Kafulafula U. The evidence supporting nursing management of labor. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2007;36(6):598-604.

25. Greenwald L, Mondor M. Malpractice and the perinatal nurse. J Perinat Neonatal Nurs. 2003;17(2):101-109.

26. Grunebaum A, Chervenak F, Skupski D. Effect of a comprehensive obstetric patient safety program on compensation payments and sentinel events. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;204(2):97-105.

27. Haig KM, Sutton S, Whittington J: SBAR: a shared mental model for improving communication between clinicians. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2006;32(3)167-175

28. Harris KT, Treanor CM, Salisbury ML: Improving patient safety with team coordination: challenges and strategies of implementation. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2006;35(4)557-566

29. Institute of Medicine. To err is human: building a safer health system. Washington DC: National Academy Press; 2000.

30. Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations. Comprehensive manual for accreditation of hospitals. Oak Brook, IL: The Joint Commission; 2003.

31. Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations. Preventing infant death during delivery. Sentinel Event Alert no. 30. Oak Brook, IL: The Joint Commission; 2003.

32. Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations. (The Joint Commission) behaviors that undermine a culture of safety. Sentinel Event Alert, no. 40. Oak Brook, IL: The Joint Commission; 2008.

33. Jonsson M, Nordén SL, Hanson U. Analysis of malpractice claims with a focus on oxytocin use in labour. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandanavica. 2007;86(3):315-319.

34. Kelly CS: Perinatal computerized patient record and archiving systems: pitfalls and enhancements for implementing a successful computerized medical record. J Perinat Neonatal Nurs. 1999;12(4)1-14

35. Knox G, Simpson KR. Perinatal high reliability. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;204(5):373-377.

36. Knox G, Simpson K, Garite T: High reliability perinatal units: an approach to the prevention of patient injury and medical malpractice claims. J Health Risk Manag. 1999;19(2)24-32

37. Koniak-Griffin D. Strategies for reducing the risk of malpractice litigation in perinatal nursing. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 1999;28(3):291-299.

38. Leonard M, Graham S, Bonacrum D: The human factor: the critical importance of effective teamwork and communication in providing safe care. Qual Saf Health. 2004;13(Suppl 1)i85-i90

39. Lyndon A, Zlatnick MG, Wachter RM: Effective physician-nurse communication. a patient safety essential for labor & delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol: 2011 doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2011.04.021

40. Macones GA, Hankins GD, Spong CY, et al: The 2008 National Institute of Child Health and Human Development workshop report on electronic fetal monitoring: update on definitions, interpretation, and research guidelines. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2008;37:510-515 Obstet Gynecol 112(3):661–666, 2008

41. Mahlmeister L. Legal implications of fetal heart assessment. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2000;29(5):517-526.

42. Mazza F, Kitchens J, Kerr S, et al. Eliminating birth trauma at Ascension Health. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2007;33(1):15-24.

43. McCartney PR. Using technology to promote perinatal patient safety. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2006;35(3):424-431.

44. McFerran S, Nunes J, Pucci D, et al: Perinatal patient safety project: a multicenter approach to improve performance reliability at Kaiser Permanente. J Perinat Neonatal Nurs. 2005;19(1)37-45

45. McRae M: Fetal surveillance and monitoring: legal issues revisited. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 1999;28(3)310-319

46. Miller L: Intrapartum fetal monitoring: liability and documentation. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2011;54:50-55

47. Miller LA. Patient safety and teamwork in perinatal care. J Perinat Neonatal Nurs. 2005;19(1):46-51.

48. Miller LA: Safety promotion and error reduction in perinatal care: lessons from industry. J Perinat Neonatal Nurs. 2003;17(2)128-138

49. Miller LA: System errors in intrapartum electronic fetal monitoring: a case review. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2005;50(6)507-517

50. Minkoff H, Fridman D. The immediately available physician standard. Semin Perinatol. 2010;34:325-330.

51. National Patient Safety Foundation. Talking to patients about health care injury: statement of principle. Chicago: NPSF; 2000.

52. Park K. Human error. Handbook of human factors and ergonomics. New York: Wiley; 1997.

53. Pettker CM, Thung SF, Norwitz ER, et al. Impact of a comprehensive patient safety strategy on obstetric adverse events. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;200:492.e1-492.e8.

54. Pettker CM, Thung SF, Raab CA, et al. A comprehensive obstetrics patient safety program improves safety climate and culture. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;204(3):2161-2166.

55. Provonost PJ, Holzmueller CG, Ennen CS, et al. Overview of progress in patient safety. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;204(1):5-10.

56. Queenan JT: Professional liability: storm warning. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;98(2)194-197

57. Raines D: Making mistakes: prevention is key to error-free health care. AWHONN Lifelines. 2000;4(1)35-39

58. Reason JT: Understanding adverse events. the human factor. Vincent C, editor. Clinical risk management. London: BMJ Books, 2001.

59. Reeves M: Building expertise: making the case for fetal heart monitoring certification. AWHONN Lifelines. 2001;5(2)71-72

60. Roberts KH. Managing hazardous organizations. Calif Manage Rev. 1990;32:101-113. (Summer)

61. Roberts KH. Some characteristics of high reliability organizations. Organization Sci. 1990;1(2):160-177.

62. Rommal C. Risk management issues in the perinatal setting. J Perinat Neonatal Nurs. 1996;10(3):1-31.

63. Rosenstein AH: Managing disruptive behaviors in the health care setting: focus on obstetrics services. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;204(3)187-192

64. Simpson KR: Failure to rescue: implications for evaluating quality of care during labor and birth. J Perinat Neonat Nurs. 2005;19(1)24-34

65. Simpson KR: Measuring perinatal patient safety: review of current methods. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2006;35(3)432-442

66. Simpson KR, Knox GE: Adverse perinatal outcomes: recognizing, understanding, and preventing common accidents. AWHONN Lifelines. 2003;7(3)224-235

67. Simpson KR, Knox GE: Common areas of litigation related to care during labor and birth: recommendations to promote patient safety and decrease risk exposure. J Perinat Neonatal Nurs. 2003;17(2)94-109

68. Simpson KR, Knox GE. Perinatal teamwork. AWHONN Lifelines. 2001;5(5):56-59.

69. Simpson KR, Knox GE: Risk management and EFM: decreasing risk of adverse outcomes and liability exposure. J Perinat Neonatal Nurs. 2000;14(3)40-52

70. Sinclair BP. Nurses and malpractice. AWHONN Lifelines. 2000;4(5):7.

71. Singh H, Thomas EJ, Petersen LA, et al: Medical errors involving trainees: a study of closed malpractice claims from 5 insurers. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(19)2030-2036

72. Slagle T: Perinatal information systems for quality improvement: visions for today. Pediatrics. 1999;103(1 Suppl E)266-277

73. Sleutel M, Schultz S, Wyble K. Nurses’ views of factors that help and hinder their intrapartum care. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2007;36(3):203-211.

74. Straub SD. Implementing best practice safety initiatives to diminish patient harm in a hospital-based family birth center. Newborn Infant Nurs Rev. 2010;10(3):151-156.

75. Veltman L. Poor systems create liability for good providers. , Garza M, Piver JS, editors.Ob Gyn Malpract Prevent. 2003;10:49-56. 7

76. White AA, Pichert JW, Bledsoe SH, et al. Cause and effect analysis of closed claims in obstetrics and gynecology. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105(5 Pt 1):1031-1038.

77. Young P, Hamilton R, Hodgett S, et al. Reducing risk by improving standards of intrapartum fetal care. J R Soc Med. 2001;94(5):226-231.