Risk management

The use of human error models to understand the causes of patient safety incidents

The use of human error models to understand the causes of patient safety incidents

Risk management techniques that can be used to understand the ‘root causes’ of an incident

Risk management techniques that can be used to understand the ‘root causes’ of an incident

Some of the common risks in the pharmacy setting

Some of the common risks in the pharmacy setting

The National Patient Safety Agency’s ‘Seven Steps to Patient Safety’

The National Patient Safety Agency’s ‘Seven Steps to Patient Safety’

A structured approach to undertaking risk assessment in the pharmacy

A structured approach to undertaking risk assessment in the pharmacy

Introduction

Risk – the probability that an adverse event will occur – is a normal part of daily life. We all continuously face risks and make decisions about them. Each day we decide when it is safe to cross the road and when it is more sensible to wait; we may choose to travel by car rather than walk. In these everyday choices, we assess the potential risks and benefits, and select a plan of action. Risk management is all about this process of anticipating potential hazards and reducing the likelihood of a problem occurring. However, before thinking about how to minimize or eliminate the possibility of errors, it is important to first consider how errors occur.

Human error models

Human error can be considered in two ways: the person approach and the systems approach. Traditionally, the person approach has been the dominant approach used in health care. This focuses on the errors of individuals, blaming them for forgetfulness, inattention, carelessness, negligence or recklessness. It has been widely acknowledged that blaming individuals does not encourage reporting and learning from errors, and the development of an effective risk management culture within healthcare settings depends critically on establishing an open reporting culture.

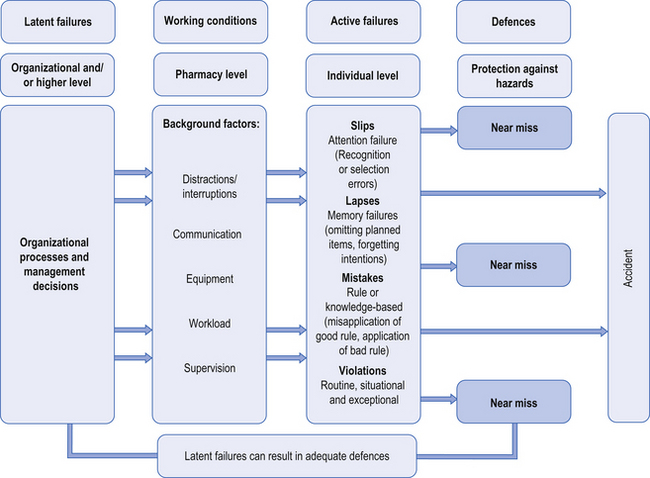

During the past decade, there has been increased interest to understand how management practices and other workplace factors impact on patient safety. The systems approach acknowledges that humans are imperfect and errors are to be expected, even in the best organizations. Rather than focusing on the individual, the systems approach concentrates on the conditions under which individuals work, trying to build defences to avoid errors or to mitigate their effects. James Reason (2000) classified medical errors into two types, active and latent failures, where active failures are unsafe acts (e.g. dispensing the wrong drug) committed by individuals who are at the ‘sharp end’ of health care, while latent failures are more distant from the actual incident and reflect failures in management or other organizational factors.

Active failures

Active failures take a variety of forms, such as slips, lapses, mistakes and procedural violations, as shown in Figure 10.1.

Figure 10.1 Reason’s (2000) four-stage model of human error theory.

Slips occur when there has been a lack of attention, despite the fact that the individual has all the necessary skills to complete the task successfully. Lapses involve memory failures, such as forgetting your intentions or omitting planned actions. In contrast, mistakes happen when we are in conscious control of the situation, but successfully execute the wrong plan of action. For instance, selecting the wrong plan can come about because of an incorrect assessment of the situation, such as arriving at the wrong diagnosis for an individual asking for an effective treatment for an ‘upset stomach’.

Violations, on the other hand, involve deliberate deviations from the procedures or best way of performing a task, such as not following SOPs (see Ch. 11) within the pharmacy. Several types of violations have been described, which are outlined in Box 10.1.

Each of these error types (slips, lapses, mistakes, violations) requires different strategies to be implemented to avoid similar events occurring in the future. Better system defences, such as redesigning the workplace, can help to minimize slips and lapses. Improved training and rigorous checking procedures can prevent some mistakes. Developing relevant procedures and protocols, ensuring effective implementation with the provision of the necessary resources and support are all important in promoting compliance and therefore avoiding procedural violations.

Latent failures

Latent failures are those whose adverse consequences may lie dormant, only becoming evident when they combine with other factors. These usually stem from poor decisions, made at a different time and place, by more senior members of the organization or people operating at a different level, such as the headquarters of a pharmacy chain. Latent failures have two kinds of adverse effect: they can lead to error and violation provoking conditions in the workplace (e.g. time pressures, understaffing, inadequate equipment, inexperience) or they can create weaknesses in the defences (e.g. unworkable procedures or design problems).

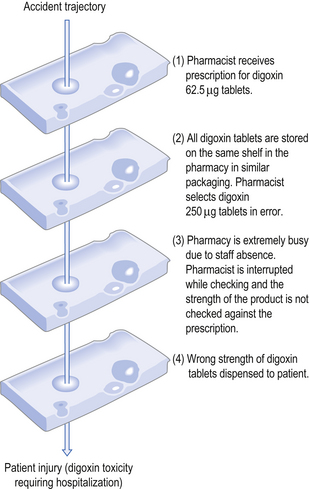

The investigation of many threats to patient safety has shown that there are usually multiple causes and they tend to occur when there is an unfortunate combination of active and latent failures. Reason (2000) proposed the ‘Swiss cheese’ model to illustrate how accidents can occur within systems. This analogy compares the defensive layers of the system to layers of Swiss cheese, each having holes that represent safety failures. The presence of holes in one slice may not result in an accident because the other slices act as safeguards. However, the holes in the layers may temporarily line-up, creating an opportunity for an accident. Figure 10.2 shows how multiple failures in the pharmacy setting can result in patient harm.

Risk management tools

There are a number of useful techniques that can be used to help understand the underlying causes of adverse events and help identify actions that can be put in place to avoid similar events occurring in the future. For instance, root cause analysis (RCA) provides a framework to reflect on an actual or potential error, working back across the sequence of events. RCA aims to uncover the underlying, contributory and causal factors that resulted in an error, and also understand better the protective factors that may have prevented harm from occurring. It is important to include all those involved in the incident in order clearly to map out the chronology of events. The analysis is then used to identify areas for change and possible solutions, to help minimize the reoccurrence of the event in the future. Various methods can be used for RCA including the use of a ‘fishbone diagram’, in which each of the ‘bones’ reflect different system failures, or the use of timelines where a chronological chain of events is mapped and tracked.

Failure modes and effects analysis (FMEA) is a systematic tool for evaluating a process and identifying where and how it might fail. It also assesses the relative impact of different types of failure and so prioritizes which areas need attention first. In addition, it can be used to assess the likelihood of the event reoccurring following changes to the system. The FMEA process involves:

Mapping out the steps of the process through group discussion

Mapping out the steps of the process through group discussion

Identification of possible failure modes (what could go wrong?) by brainstorming

Identification of possible failure modes (what could go wrong?) by brainstorming

For each error type or failure mode identified, a cause (why should failure happen?) and effect (what would be the consequences of each failure?) are attributed, together with scores for likelihood of occurrence, likelihood of detection and severity.

For each error type or failure mode identified, a cause (why should failure happen?) and effect (what would be the consequences of each failure?) are attributed, together with scores for likelihood of occurrence, likelihood of detection and severity.

Multiplication of these three scores generates a risk priority number (RPN), which can be used to prioritize changes within the pharmacy.

Risk to patients in the pharmacy setting

It is increasingly recognized that risks within healthcare organizations, including pharmacies, are diverse and complex, and not just confined to specific activities. An accurate estimate of the extent and causes of adverse events that originate from the pharmacy is difficult to obtain since different methods have been used to collect the data.

Research has, however, suggested that in the UK, for every 10 000 prescription items dispensed in community pharmacies, there are likely to be at least 26 dispensing incidents. Most threats do not result in actual patient harm, but have the potential to do so. The most common types of events include incorrect product selection (60%) and labelling errors (33%). Organizational factors are associated with the majority of these errors, including issues concerning distractions while assembling and checking prescriptions, poor communication, excessive workload and inadequate staffing.

Studies have also reported on practice variation in the way in which non-prescription medicines are sold and advice is communicated to patients in community pharmacies, suggesting that in some cases, pharmacy services may be deficient or sub-optimal. Over the last decade, the Consumers’ Association in the UK has repeatedly criticized deficiencies in the level of advice, questioning and referral of consumers to other healthcare professionals from community pharmacies.

It is also important to consider risks to pharmacy staff and customers through failures to comply with health and safety legislation. The Health and Safety at Work Act 1974 is the guiding piece of legislation placing responsibilities on employers and employees to carry out risk assessments. Pharmacies should have a health and safety policy in place, with responsibilities allocated to specific members of staff. Key areas of concern that are relevant to the pharmacy setting include having an effective procedures manual dealing with control of substances hazardous to health, fire precautions, workplace equipment, the pharmacy environment (such as unsafe furniture and fittings) and first aid.

Developments in health policy

In 2000, the Chief Medical Officer for England published An organisation with a memory (OWAM Report, DH 2000). This was a report of an expert group on learning from adverse events in the NHS, drawing on insights from human error and risk management as applied in other high-risk industries, such as aviation and nuclear power. The report presented international evidence on the scale and impact of adverse events and made reference to the lack of systems in the NHS that allowed there to be learning from adverse events. The expert group concluded that the NHS could benefit greatly by applying these risk management principles to health care.

The report also recommended as one of its four key targets, that there should be a 40% reduction in the number of serious errors involving prescribed drugs. In 2004, the Chief Pharmaceutical Officer for England published Building a safer NHS for patients: improving medication safety (DH 2004), which outlined strategies aimed at reducing the occurrence of prescribing, dispensing and administration errors drawing on experience and models of good practice within the NHS and worldwide.

More recent requirements, forming part of the essential services of the contractual framework for community pharmacy in England and Wales, has meant that SOPs covering the dispensing process need to be in place in pharmacies. In addition, all pharmacies should be able to demonstrate evidence of recording, reporting, monitoring, analysing and learning from patient safety incidents. Furthermore, pharmacists are now expected to be competent in risk management, including the application of root cause analysis (RCA).

National patient safety agency (NPSA)

Following the publication of the highly influential OWAM report, the NPSA was established in June 2001 to coordinate efforts to report and learn from patient safety incidents. The NPSA has published guidance for NHS organizations on the seven steps that they should take in order to improve patient safety (as described in Box 10.2). It is clear that risk management is firmly incorporated into this guidance.

Of particular interest, the NPSA has also published recommendations on the labelling and presentation of a dispensed medicine as well as suggestions on how to promote the safe use of medicines. In addition, it has also published recommendations on changes in the general dispensing environment that can improve patient safety.

The risk management process

The risk management process is about the planning, organization and development of a strategy that will identify, assess and ultimately minimize risk. The process can be represented by a sequence of steps but there is much overlap and often there is integration between all the steps.

Step 1: Establish the context

It is essential to identify all the legal and professional requirements for the pharmacy and to respond appropriately, since most of these will be needed for accreditation purposes or to satisfy a risk insurer or commissioner of pharmaceutical services. For instance, pharmacies are routinely inspected by the regulatory body. Community pharmacies in England and Wales are also required to take part in monitoring visits from representatives of their commissioning body to check compliance with the community pharmacy controls assurance framework.

Step 2: Identification of risk

It is important to take into account things that have gone wrong in the past or near miss incidents that have previously occurred. Box 10.3 lists a variety of methods that can be used to identify risks in the pharmacy, and different approaches can be used in combination. Each method will identify different aspects about the frequency and nature of risks in the pharmacy.

Step 3: Analysis of risk

Once a risk has been identified, it should be analysed to determine what action needs to be taken. Ideally, the risk should be eliminated, but often this may not be possible and efforts need to be taken to minimize its potential impact. The use of rigorous risk management techniques such as RCA and FMEA can play an important role at this stage.

The following factors should be considered:

The likelihood that an adverse event will occur

The likelihood that an adverse event will occur

Its potential impact (seriousness)

Its potential impact (seriousness)

The availability of methods to reduce the chance of the event happening

The availability of methods to reduce the chance of the event happening

The costs (financial and other) of solutions to minimize the occurrence of similar events in the future.

The costs (financial and other) of solutions to minimize the occurrence of similar events in the future.

This will involve making decisions about risks that are rare but potentially very serious compared with risks that are very common but have a low probability of causing harm.

Step 4: Manage the risk

A range of choices is often available to manage the identified risks. The decision is largely determined by the financial cost of implementation balanced against the potential benefits (such as the cost of compensation if an adverse event occurred). The cost of preventing one major, but very rare, adverse event may be very great when compared with preventing hundreds of more minor adverse events.

Risk control

It may not be possible to eliminate all the identified risks, but preventative steps can be introduced that minimize the likelihood of an adverse event occurring.

Risk acceptance

This involves the recognition that the risk cannot be entirely removed, but at least it can be known and anticipated.

Risk avoidance

It may be possible to avoid the risk by understanding the causes of the risk and taking appropriate actions. An example is the recognition that company branding may result in different medications, such as digoxin tablets (see Fig. 10.2), being packaged in similar ways. This risk can be reduced by using different manufacturers so that different medications are clearly distinguishable.

Step 5: Auditing and reviewing performance

Finally, the effectiveness of the approaches used to identify, analyse and treat risks should be reviewed. The role of audit is essential, in which risk management standards are set and monitored to see if the standards have been met. Following audit, the cycle of organizing, planning, measurement and review should reoccur to support continuous improvement within the pharmacy.

Conclusion

Risk management is an essential role for pharmacists to protect patients from harm. An understanding of human error models and risk management techniques can be used to analyse the possible risks in a working pharmacy environment and thus manage the risks.

Key Points

Risk is a normal part of daily life, but risk management attempts to minimize or eliminate risk

Risk is a normal part of daily life, but risk management attempts to minimize or eliminate risk

Errors can be classified as active or latent

Errors can be classified as active or latent

Active failures are things like slips, lapses, mistakes and procedural violations by a pharmacist

Active failures are things like slips, lapses, mistakes and procedural violations by a pharmacist

Latent failures often arise as a result of poor decisions by other, more senior people

Latent failures often arise as a result of poor decisions by other, more senior people

Techniques such as root cause analysis (RCA) are useful risk management tools

Techniques such as root cause analysis (RCA) are useful risk management tools

A systematic tool such as failure modes and effects analysis (FMEA) has three main steps – mapping, identification and specifying cause and effect. Together they produce a risk priority number (RPN)

A systematic tool such as failure modes and effects analysis (FMEA) has three main steps – mapping, identification and specifying cause and effect. Together they produce a risk priority number (RPN)

Adoption of SOPs is a contractual requirement for community pharmacies

Adoption of SOPs is a contractual requirement for community pharmacies

Risk management processes have five essential stages: establish a context; identify the risks; analyse the risks; manage the risks; audit and review performance

Risk management processes have five essential stages: establish a context; identify the risks; analyse the risks; manage the risks; audit and review performance