Prescribing for minor ailments

The growth of self-care and the increase in access to medicines

The growth of self-care and the increase in access to medicines

Gaining information from patients who present at the pharmacy with symptoms or conditions

Gaining information from patients who present at the pharmacy with symptoms or conditions

Use of clinical reasoning to aid differential diagnosis and not an acronym-based approach

Use of clinical reasoning to aid differential diagnosis and not an acronym-based approach

Assessment of patient’s symptoms in order to provide treatment and/or advice for minor ailments

Assessment of patient’s symptoms in order to provide treatment and/or advice for minor ailments

Introduction

The community pharmacist plays an essential role in providing patient care. In most western countries, a network of pharmacies allows patients easy and direct access to a pharmacist without an appointment. Without pharmacists, general medical services would be unable to cope with patient demand. In effect, pharmacists perform a vital triage role for doctors by filtering those patients who can be managed with appropriate advice and medicines and referring cases which require further investigation. This has been a central role of community pharmacists for many decades, but over the last 20 years the role has taken on greater significance as there has been a shift in global healthcare policy to empower patients to exercise self-care. For pharmacists to safely, effectively and competently manage minor ailments requires considerable knowledge and skill. It involves having the underpinning knowledge on diseases and their clinical signs and symptoms, the ability to apply this knowledge to an individual patient and use problem solving to arrive at a working differential diagnosis. This has to be combined with good interpersonal skills such as picking up on non-verbal cues, asking appropriate questions and articulating clearly any advice which is given (see Ch. 25). This chapter attempts to provide the contextual framework behind the growing prominence of the pharmacist in managing minor ailments and the key skills required to maximize performance.

The concept and growth of self-care

The concept of self-care is not new. People have always treated themselves for common illnesses and pharmacists have always provided an avenue for people to practise self-care. Self-care does not mean individuals are left on their own and means more than just looking after themselves. It includes all the decisions and actions people take in respect of their health and covers recognizing symptoms, when to seek advice, treating the illness and making lifestyle changes to prevent ill health. The expertise and support provided by healthcare professionals, such as pharmacists, is crucial to making self-care work. The profile of self-care has dramatically increased in recent years and is largely government driven, consumer fuelled and professionally supported.

Government policy

The creation of national healthcare schemes, such as the NHS has encouraged the general population to become more reliant on institutional bodies to look after their health. This has led to increased demand on services provided by these bodies, including the management of minor illness. For example, more than one in three GP consultations are for minor illnesses and an estimated 20–40% of GP time could be saved if patients exercised self-care. Similar findings have been recorded for patients attending hospital emergency departments. This dependence by patients on bodies such as the NHS has led to government policies which encourage and facilitate self-care. In the UK, the government agenda for modernizing the NHS was spelt out in its White Paper-The NHS Plan (2000). Within this document, the government made its intention clear to make self-care an important part of NHS health care. It stated that the front line of health care was in the home. Since that time the government has published numerous papers detailing why and how maximizing self-care can be achieved.

NHS walk-in centres and telephone help lines

The UK government has been proactive in facilitating self-care, most obviously by the formation of NHS walk-in centres and the telephone help lines NHS Direct (England and Wales) and NHS 24 (Scotland). The aim of walk-in centres is to improve access to health care that supports other local NHS providers. The service is nurse led but some employ doctors to work at particular times. The first NHS walk-in centre opened in 2000 and there are now approximately 90 operating in England. The Department of Health states that over 5 million people have used a walk-in centre with the main users being young adults. NHS Direct is a 24-hour nurse-led service that receives over 500 000 calls per month. Although originally designed as a telephone help line service, NHS Direct now also offers an online service and direct interactive digital TV plus the publication of its self-help guide. In April 2013, NHS Direct was replaced by the NHS 111 service.

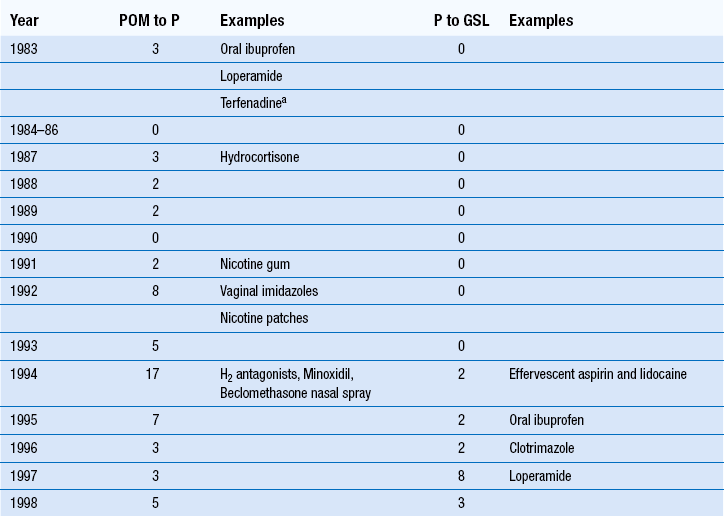

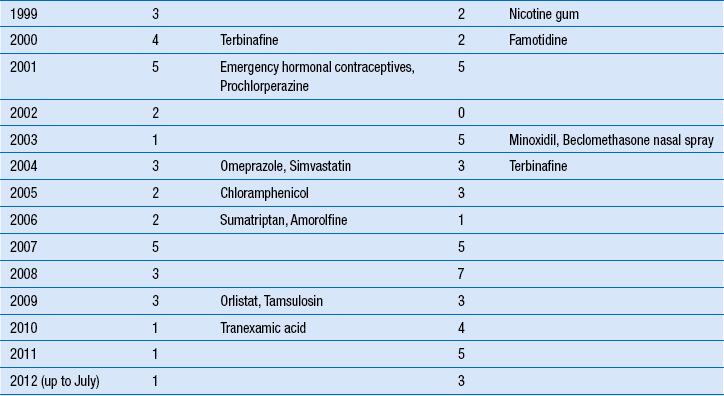

Deregulation of medicines

Less obvious, but arguably more important, has been the expansion of medicines available without prescription (Table 21.1). This has direct impact on community pharmacists and represents one of the major ways in which pharmacy can contribute to self-care. The switching of POMs to P status is now well established. Loperamide and ibuprofen were the first POMs to be switched in 1983. Between 1983 and 2012, over 80 POM to P and 50 P to GSL switches were made. Recent POM to P switches have seen new therapeutic classes deregulated (e.g. proton pump inhibitors, triptans, alpha-blockers) although the number of products switched has slowed. This is in contrast to P to GSL deregulation where the number of switches has steadily increased. This has led to the current situation where most medicines are now GSL and freely available from all retail outlets.

Table 21.1

Chronological history charting prescription only medicine (POM) to pharmacy (P) and P to general sales list (GSL) deregulation

aTerfenadine reverted back to POM control in 1997 following serious adverse events in America and was subsequently withdrawn by the manufacturers.

The pharmacists’ role in facilitating patient self-care

Pharmacists play a vital role in acting as a custodian of medicines and being the gatekeeper between patient self-care and the necessity to see a GP. As pharmacists are able to provide an ever-increasing arsenal of medicines to treat a growing number of conditions their role as first-line healthcare professionals is taking on greater significance, which in turn has implications on patient safety. It is vital that pharmacists possess the right knowledge and diagnostic skills to make sound clinical decisions.

Arriving at a differential diagnosis

The aim of any patient consultation is to determine a diagnosis from the presenting signs and symptoms. In some instances, a specific diagnosis can be determined as the set of signs and symptoms the patient has point very clearly to only one cause. However, in many cases the exact cause can be hard to determine and a ‘differential diagnosis’ will be made. In other words there is a degree of uncertainty with the diagnosis and the practitioner will make a treatment plan based on what they think is the most likely cause. For example, someone who presents with acute cough is likely to have a viral self-limiting cough but it could possibly be bacterial in origin. Advice and treatment might well be the same but an exact diagnosis cannot be made.

To be able to make sound and competent differential diagnoses pharmacists require the pre-requisite knowledge and good consultation skills.

Knowledge

The cornerstone of making any diagnosis is having a sound knowledge of the presentation of conditions, which are likely to be seen in a community pharmacy. Exact prevalence data is lacking for community pharmacy consultations but it does not seem unreasonable that patterns of presentation in a community pharmacy are not too dissimilar from a GP practice. Based on this assumption, it is simple to identify those conditions that are most likely to be seen by a community pharmacist. This should be the starting point from which to build subject specific knowledge. For example if we take red eye, prevalence data from general medical practice would show that:

Most Likely – Bacterial or allergic conjunctivitis

Most Likely – Bacterial or allergic conjunctivitis

Likely – Viral conjunctivitis, sub-conjunctival haemorrhage

Likely – Viral conjunctivitis, sub-conjunctival haemorrhage

It would seem most prudent to have a thorough knowledge of the signs and symptoms of all types of conjunctivitis and sub-conjunctival haemorrhage as these will form the vast majority of red eye presentations seen by the community pharmacist. Of course this does not mean that other conditions that are seen less commonly by the pharmacist should be ignored. However, if basic information on common presentations is lacking then inappropriate referrals are more likely and signs or symptoms that might suggest more sinister pathology will be missed.

Gaining information

Observation, asking questions and physical examination should all be used, where appropriate, to elicit information from the patient. Most obvious is the need to ask questions (see below) to explore the presenting signs and symptoms. However, equally important is knowing who you are dealing with and the way in which they present in the pharmacy. Finally, in certain circumstances questioning and observation can be supplemented by performing a physical examination (see later).

Questioning

Pharmacists will rely heavily on asking questions to guide a differential diagnosis. Studies with doctors have shown that an accurate patient history (gained from asking questions alone) is a powerful diagnostic tool and will enable the practitioner to arrive at a right diagnosis in about 80% of cases. If a physical examination is conducted and/or diagnostic tests performed, then the probability of a correct diagnosis is increased by 10–15%.

The ability to ask appropriate questions to gain the necessary information is therefore critical. The choice of question asked is rooted in clinical reasoning (see below) but at a more basic level, the type of question and the way in which it is asked will dictate the level of response given.

Use of open and closed questions

There are two main types of questions: open and closed. A closed question requires the respondent to give a single word reply such as ‘Yes’ or ‘No’. Closed questions often with words such as ‘Are you’, ‘Have you’ and ‘Do you’. Examples of closed questions are:

Closed questions can be very useful when asking for specific information or to test a hypothesis. Over use of closed questions however should be avoided as the consultation can then feel more like an interrogation than a two-way conversation.

Open questions allow patients to respond in their own way. They do not set any ‘limits’ and generally will provide more detailed information. Open questions often start with words such as ‘describe’, ‘what’, ‘where’ and ‘how’. Examples of open questions include:

Open questions are not without their problems. Some patients when asked an open question will provide irrelevant information and it can be difficult to pick up on the important information that is mixed in with irrelevant facts. An active listening approach is required (see Chs 17 and 25).

In most consultations a mixture of closed and open questions will be needed.

Using observation and knowledge of epidemiology

Assessment of the patient begins the moment the patient enters the pharmacy. First impressions can provide ‘cues’ to their state of health. Most pharmacists will probably do this at a subconscious level but what is important is to bring this to the conscious level and build it into your consultations. Many visual cues will be apparent if they are actively looked for. It may give you an indication of severity, for example does the patient look well or poorly? Do they show any obvious signs of discomfort? This initial assessment will provide useful information which shapes your thinking and actions, and is the first step to reaching a differential diagnosis. It might transpire that they have a self-limiting condition such as viral cough that ordinarily you would not refer to the GP but because the person is elderly and has marked systemic upset, a referral is appropriate.

The key is to observe your patient. What is their physical appearance? Is the patient overweight or showing signs of being a smoker? Are there any signs of confusion, pain or systemic illness? Take time to assess what they look like, how they move and how they behave.

In tandem with observation, the pharmacist should draw on the epidemiology of conditions within a population. This will be very helpful in formulating early ideas about what the likely diagnosis will be.

Take headache as an example. The age and gender of the patient will affect diagnostic probability: migraine is three times more common in women than men, whereas cluster headache is eight times more common in men. Onset of migraine tends to occur in adolescents or young adults but is rare in people aged over 50 years old. Therefore, the age and sex of the patient asking for advice on headache symptoms will begin to shape your differential diagnosis even before you start to ask any questions. This principle can be applied to all consultations and can also be used while asking questions.

Take cough as an example. A question that pharmacists will ask is the symptom duration. Knowing how long the cough has lasted will again affect the most likely diagnosis. The longer the cough has been present, the more prevalent are conditions with sinister pathology. So for a patient with a cough of 3 days duration, the most likely cause will be a viral upper respiratory tract infection. At 3 weeks’ duration, the chances of it being a viral cause are lessened but other conditions such as acute bronchitis become more likely. At 3 months’ duration, then sinister causes of cough are much more likely, such as chronic bronchitis, TB and carcinoma.

The linking of epidemiological data of conditions to each patient consultation is an important aspect of clinical reasoning and should be an integral part of the process when making a differential diagnosis.

Physical examination

Within the confines of a community pharmacy, the type and extent of physical examination that can be performed is limited. Examples of physical assessments that are suitable within the pharmacy include eye and ear examinations, assessment of skin disease and general inspection of the oral cavity. These examinations require little training but will improve the odds of making a correct diagnosis. Before conducting any physical examination, it is important to explain to the patient what you would like to do and why. Informed consent must be received. Ideally, physical examinations should be conducted in a private area and consideration should be given to having a chaperone present.

Clinical reasoning

Clinical reasoning is a critical skill that all pharmacists should possess. It is central to the decision-making processes associated with clinical practice. It enables practitioners to act autonomously allowing them to make the best reasoned actions in a specific context. When attempting to make a diagnosis, pharmacists will often be faced with an ill-defined problem, working with limited information where outcomes are difficult to predict. By this very definition pharmacists have to use their professional judgement and make decisions where clinical uncertainty will exist.

Much has been written on clinical reasoning and the ways in which it can be taught. A number of models have been proposed to explain the process and include hypothetico-deductive reasoning, pattern recognition and knowledge reasoning integration.

Given that OTC patient consultations is akin to medical practice in terms of making a diagnosis, then pharmacists should learn from the medical approach to clinical reasoning when making a diagnosis.

Hypothetico-deductive reasoning

As stated previously, pharmacists will often be faced with limited information in the early stages of a clinical encounter. The ‘art’ of deciding what information must be collected, what areas need exploration and what information can be safely disregarded will form the basis of the consultation. Data collection can therefore be described as both sequential and selective, which allow inferences to be drawn about the underlying cause of the patient’s signs and symptoms.

Research has shown doctors approach solving diagnostic problems by generating a small number of hypotheses early in a clinical encounter and based on limited information. The generation of these hypotheses then guides subsequent data collection. Each hypothesis can be used to predict what additional findings ought to be present if it were true and what further questions to ask in a guided search for these findings – a hypothetico-deductive approach. Hypothesis generation and testing involves both inductive (moving from a set of specific observations to a generalization) or deductive reasoning (moving from a generalization to a conclusion in relation to a specific case). Therefore, induction is used to generate hypotheses and deduction to test hypotheses.

An example may serve to illustrate this process:

Step 1: Drawing on subject specific knowledge

A cornerstone of making rationale decisions will be the need to have a good subject specific knowledge on cough and understanding the epidemiology of conditions that cause cough. You should know that the causes of cough and their relative incidence in community pharmacy are:

Most Likely – Viral infection (all ages)

Most Likely – Viral infection (all ages)

Likely – Upper airways cough syndrome (formerly known as postnasal drip and includes allergies), acute bronchitis

Likely – Upper airways cough syndrome (formerly known as postnasal drip and includes allergies), acute bronchitis

Unlikely – Croup, chronic bronchitis, asthma, pneumonia, ACE inhibitor induced

Unlikely – Croup, chronic bronchitis, asthma, pneumonia, ACE inhibitor induced

Very unlikely – Heart failure, bronchiectasis, tuberculosis, cancer, pneumothorax, lung abscess, nocardiosis, GORD

Very unlikely – Heart failure, bronchiectasis, tuberculosis, cancer, pneumothorax, lung abscess, nocardiosis, GORD

Step 2: Visual cues: age, sex and overweight

Before asking any questions, you are already using the visual cue information to start to generate hypotheses. If we consider his age and apply this to the prevalence of the above conditions, we can safely eliminate croup as a cause of cough and the diagnostic probability of other conditions is low; pneumothorax tends to occur in young people; heart failure and lung abscess tend to occur in the elderly; asthma (presenting as cough only) tends to occur in children.

We are now left with fewer possibilities as to the cause of cough, allowing us to generate hypotheses that do not (initially) consider those eliminated because of age. Early hypothesis generation may well centre on a viral cause of cough, as it is the most commonly encountered cause of cough in his age group. Other hypotheses will focus on those conditions deemed likely and to a lesser extent, those which are unlikely.

Step 3: Testing hypotheses

Questions now need to be asked to gain more information on the symptoms of the patient’s cough. Consideration should be given to what questions are asked and why. All questions that are asked should have an underlying purpose or reason. At this stage, early in the clinical encounter, initial questions should enable hypothesis generation to be narrowed. Questions asked should enable this narrowing process. So, if we take length of time the patient has had the cough as an example, subject-specific knowledge means we know that a cough of duration of longer than 3 weeks suggests a non-acute cause. Establishing duration will therefore be discriminatory in terms of narrowing down the diagnostic possibilities left open to you:

Certain causes of cough do not become chronic in nature. Therefore, if a patient presents with a long-standing cough, you can eliminate acute causes and thus narrow down your diagnosis. At this point, you can reformulate your hypotheses and the next set of questions you ask will try to distinguish between those conditions which remain as a possibility.

Your next question may ask about sputum production. From the chronic causes listed above, a medicine cause and GORD will be eliminated if the patient states that they produce sputum, leaving five causes of cough that may be causing the patient’s symptoms. From this point, you may need to ask specific (closed) discriminatory questions which allow you to hone your differential diagnosis still further. Some chronic cough conditions tend to show periodicity during the day, either being better or worse in the morning or evening. From our remaining conditions, we know that generally:

Chronic bronchitis is worse in the morning

Chronic bronchitis is worse in the morning

Bronchiectasis is worse in the morning and evening

Bronchiectasis is worse in the morning and evening

Our patient says that the cough is always worse after getting up in the morning. This therefore tends to point to a diagnosis of chronic bronchitis. Obviously, the diagnosis is very tentative and we can now ask supplementary questions that should support the differential diagnosis. For example, one hypothesis would be that the person is a smoker/ex-smoker (chronic bronchitis is closely associated with smokers or ex-smokers). To support our differential diagnosis, we would expect the patient to say he smoked or had smoked in the past. Again to support the differential diagnosis, we would expect to ask about the periodicity of cough in chronic bronchitis. Confirmation of this by the patient lends further support to your differential diagnosis. If the patient responds in a different way to that anticipated, then the differential diagnosis would need to be revised and hypotheses reconstructed to establish the cause of the cough. This example demonstrates that this model of clinical reasoning is sequential and selective.

Pattern recognition

What is pattern recognition? Simply, pattern recognition can be thought of as categorization or pattern interpretation. In the clinical context, it involves grouping similar patient presentations together. Each new case seen is stored in the practitioner’s memory in the same category. A non-medical analogy would be that if a person sees a dog we categorize it as a dog, but not necessarily what breed of dog, however after seeing sufficient dogs that look the same, we further categorize these to the breed of dog. Thus, we draw on memory recall from previous experience to help us categorize each new dog seen. Therefore in clinical practice, we build up a stored memory of previously seen similar cases from which we can draw on to help inform our diagnosis. This can be applied to all patient presentations but is especially useful for dermatological presentations, as visualization of a skin rash is more helpful than a description provided by a patient. Certain dermatological conditions have very characteristic presentations. For example, once a pharmacist has seen several cases of impetigo, it is a relatively straightforward task to diagnose the next case by recalling the appearance of previous rashes seen. Therefore, much of daily practice will consist of seeing new cases that strongly resemble previous encounters.

Hypothetico-deductive reasoning versus pattern recognition

In reality, a combination of hypothetico-deduction and pattern recognition is used. Pattern recognition is often attributed to the practitioner exhibiting expertise in that situation and clinical context. Expertise in medicine is often associated with time and practice. However, time and practice in a community pharmacy context may be less relevant in differentiating between ‘novice’ and ‘expert’ behaviour. This is because pharmacists, regardless of their level of experience, use the default option of medical practitioner referral when clinical uncertainty exists. While undoubtedly this constitutes safe practice, it does not necessarily equate to improving an individual’s ability at effective pattern recognition. As pattern recognition is rooted in memory recall by matching against similar previously seen cases, then the outcome is likely to be the same–referral. Pharmacists can therefore quickly reach a ‘glass ceiling’ of clinical competence unless they actively seek feedback from the medical practitioner (or patient) to either confirm or reject their original diagnosis.

Neither model provides an error-proof strategy and error rates of up to 15%, especially in difficult cases in internal medicine, have been reported in the medical literature. However, these models of ‘responding to symptoms’ are more likely to gain the correct diagnosis compared to using acronyms and the funnel method because acronyms and the funnel method tend to just gather information without having a hypothesis in mind.

Other approaches used in ‘responding to symptoms’

In pharmacy education the use of acronyms has been widely taught at undergraduate level and subsequently adopted into community practice. A number of acronyms have been developed and include: ENCORE, ASMETHOD, SIT DOWN SIR and WWHAM. WWHAM (Who is the patient? ‘What are the symptoms? How long have the symptoms been present? Action taken? Medication being taken?) is the most well known and most widely used, probably because of it being simple to remember. Acronyms will provide structure and consistency to patient consultation but the difficulty with using acronyms is that they are rigid and inflexible – a ‘one size fits all’ approach. Using an acronym is akin to strictly following a standard operating procedure. Questions may be asked because they are part of the acronym, but they may be of little diagnostic value or there might be no relevance or underpinning reasoning for asking the question.

The most commonly used acronym, WWHAM, is also the worst; this is because it is simple to remember and so provides the least information. In addition, not all questions are helpful in establishing a diagnosis; Action taken and Medication being taken are really questions designed to help with patient management rather than aiding a diagnosis. This means that if WWHAM is routinely used, then pharmacists are only asking three questions to determine the cause of the patients presenting signs and symptoms. Furthermore, the first question, ‘Who is the patient’, in the context in which WWHAM is used is also diagnostically unhelpful. In the acronym, this question is only being used to identify the patient. It is not being asked to establish a link between presenting symptoms and prevalence of conditions – if it were, then the question would be much more useful.

A further major failing of WWHAM and other acronyms is they concentrate very much on the presenting symptoms. They tend not to consider past medical history of similar episodes, do not explore family history or consider social factors that might be causing or compounding the symptoms.

In short, pharmacists should not use acronyms. They are too simplistic, rigid, inflexible and are poor in allowing the pharmacist to arrive at a correct diagnosis. If we compare the example highlighting hypothetico-deductive technique versus an acronym, the difference between the methods is clear and obvious. If WWHAM was used, the nature of the cough would have been established, and if chronic in nature a referral probably made. However, the information gained would have been superficial, which would not establish a more precise cause and it would also ask irrelevant questions, such as who it was for (we already knew) and what medication they had tried. More fundamentally, with regard to pattern recognition, the practitioner would not be able to draw on this consultation to inform future thinking.

The funnelling technique

A funnelling technique can be used to allow direction and focusing of ideas on a specific topic. This involves initially asking background ‘open’ questions to provide basic information, then asking specific ‘closed’ questions to provide specific detail and clarify points. In these circumstances, it can be useful to paraphrase comments made, to ensure that the understanding of the information being obtained from the patient is accurate. This checking procedure allows the pharmacist to check understanding and minimizes misinterpretation. It is possible during any one conversation to use more than one ‘funnel’, e.g. establishing a patient’s current medical condition, then going on to suggest appropriate action or medication available. In a pharmacy setting, where time can be a limiting factor, using the funnelling technique can be useful for directing and focusing a conversation to enable an end point to be achieved more quickly.

Outcomes from the consultation

The final step in prescribing for minor ailments is deciding what course of action is most appropriate. This could be a combination of referral to another healthcare professional, giving advice or supplying a product. It is important that you give the patient as much information as they want or need and this draws on your skills of counselling (see Ch. 25).

Conditional referrals

One of the key things a patient needs to know is: What is the best course of action to take. Obviously this will depend on a number of factors including the patient themselves, the differential diagnosis and the severity of the condition. As a general rule, all patients should be advised on a timescale, whether they return to the pharmacist or see another healthcare practitioner. This will have to be gauged on a person-to-person basis. For example, take two patients presenting with viral cough. Acute coughs can last up to 3 weeks, although the majority will have cleared in 14 days. Therefore, depending at which point each patient presented in the course of the condition will affect your conditional referral. If the first person presents after 10 days, then you might tell them to see the doctor in 5 days time if symptoms do not improve (beyond 14 days). The second patient has only had symptoms for 2 days, in which case you would tell them that symptoms may take another 12–14 days to fully resolve.

Treatment and advice

Once a full assessment of the symptoms has been made, and a decision made that the patient can be managed by the pharmacist, appropriate recommendations should be made. At this point, shared decision-making is recommended. The patient should be fully informed of the treatment options but be guided by the pharmacist to ensure the best option is agreed upon.

The pharmacist should take into account the efficacy, side-effects, interactions, cautions and contraindications of therapeutic options. With regard to efficacy, pharmacists should be aware that many OTC medicines have little or no evidence base. This does not necessarily mean they are not effective, but in today’s climate of evidence-based health care, products with proven efficacy should constitute first-line treatment.

The difficulty in establishing efficacy has many explanations and includes: products that are available OTC predating clinical trials, a general lack of trial data or poorly conducted trials, the placebo effect seen with some OTC medicines and the nature of self-limiting conditions–is it the medicine working or the symptoms resolving on their own? When selecting a product, the patient’s needs should be borne in mind. Factors such as prior use, formulation and dosage regimens should be considered. Non-drug treatment should also be offered where appropriate. For example, providing medication for motion sickness can be supplemented with advice on how to reduce symptoms, for example focusing on distant objects, not overeating before travel or sitting in the front seat in car journeys will help to reduce symptoms.

Children and the elderly

Care is needed in assessing the severity of symptoms in children and the elderly, as both groups can suffer from complications. For example, the risk of dehydration is greater in children with fever or the elderly with diarrhoea. Invariably, lower doses are used in children, and because the elderly suffer from liver and renal impairment they frequently require lower doses than younger adults. Children should be offered sugar-free formulations to minimize dental decay and elderly people often have difficulty in swallowing solid dose formulations. It is also likely that the majority of elderly patients will be taking other medication for chronic disease and the possibility of OTC–POM interactions should be considered.

Pregnancy

The potential for OTC medicines to cause teratogenetic effects is real. The safest option is to avoid taking medication during pregnancy, especially in the 1st trimester. Many OTC medicines are not licensed for use in pregnancy and breast-feeding because the manufacturer has no safety data or it is a restriction on their availability OTC. Table 21.2 highlights those medicines where restrictions apply.

Table 21.2

Medicines to avoid during pregnancy

| Medicine | Advice in pregnancy |

| Antihistamines – sedating | Some manufacturers advise avoidance, although chlorphenamine and triprolidine are classed by Briggs et al. as being compatible |

| Antihistamines – non-sedating | Manufacturers advise avoidance as limited human trial data, but animal data suggest low risk |

| Anaesthetics – local (benzocaine, lidocaine) | Avoid in 3rd trimester – possible respiratory depression |

| Bismuth | Manufacturers advise avoidance |

| Crotamiton (e.g. Eurax) | Manufacturers advise avoidance |

| Fluconazole | Avoid |

| Formaldehyde (e.g. Veracur) | Manufacturers advise avoidance |

| Ocular lubricants (e.g. hypromellose, carbomer) | Manufacturers advise avoidance as safety has not been established |

| H2 antagonists | Avoid |

| Hyoscine | Manufacturers advise avoidance as possible risk of minor malformations |

| Migraleve (opioid component) | Avoid in 3rd trimester |

| Iodine preparations | Avoid |

| Midrid | Avoid |

| Minoxidil (e.g. Regaine) | Avoid |

| Selenium (e.g. Selsun) | Manufacturers advise avoidance |

| Systemic sympathomimetics | Avoid in 1st trimester as mild fetal malformations have been reported |

Interactions of OTC medicines with other drugs

Medicines that are available for sale to the public are relatively safe. However, there are some important drug–drug interactions to be aware of when recommending OTC medicines. These are listed in Table 21.3.

Table 21.3

Interactions of OTC medicines with POMs that can be significant

| Medicine | Possible interactions | Outcome |

| Antihistamines–sedating | Opioid analgesics, anxiolytics, hypnotics and antidepressants | Increased sedation |

| Antacids (containing calcium, magnesium and aluminium) | Tetracyclines, quinolones, imidazoles, phenytoin, penicillamine, bisphosphonates, ACE inhibitors, angiotensin II | Decreased absorption |

| Aspirin | NSAIDs and anticoagulants | Increased risk of GI bleeds |

| Methotrexate | Reduced methotrexate excretion, toxicity | |

| Bismuth | Quinolone antibiotics | Reduced plasma quinolone concentration |

| Chloroquine | Amiodarone, sotalol, antipsychotics | Increased risk of arrhythmias |

| Fluconazole | Anticoagulants | Enhanced anticoagulant effect |

| Ciclosporin | Increased ciclosporin levels | |

| Carbamazepine and phenytoin | Increased levels of both antiepileptics | |

| Rifampicin | Decreases fluconazole levels | |

| Atorvastatin | Increased atorvastatin levels that can lead to muscle pain/myopathy | |

| Note: Seriousness of the possible outcome would mean it is good practice to avoid all statins with fluconazole | ||

| Hyoscine | TCAs, and other medicines with anticholinergic effects | Anticholinergic side-effects increased |

| Ibuprofen | Anticoagulants | Enhanced anticoagulant effect |

| Lithium | Reduced lithium excretion | |

| Methotrexate | Reduced methotrexate | |

| Opioid-containing products | Alcohol, opioid analgesics, anxiolytics, hypnotics and antidepressants | Increased sedation |

| Prochlorperazine | Alcohol, opioid analgesics, anxiolytics, hypnotics and antidepressants | Increased sedation |

| St John’s wort | Anticoagulants | Reduced anticoagulant effect |

| SSRIs | Potential serotonin syndrome | |

| Phenytoin, phenobarbital, carbamazepine | Reduced antiepileptic serum level | |

| Oral contraceptives | Reduced efficacy of contraceptive | |

| Antivirals, ciclosporin, digoxin | Reduced plasma concentrations | |

| Systemic sympathomimetics, including isometheptene (ingredient in Midrid) | MAOIs and moclobemide Beta-blockers and TCAs | Risk of hypertensive crisis Antagonism of antihypertensive effect |

| Topical (nasal or ocular) sympathomimetics | MAOIs and moclobemide | Risk of hypertensive crisis |

| Iron salts | Tetracyclines, quinolones, penicillamine | Reduced absorption if taken at same time |

ACE, angiotensin converting enzyme; GI, gastrointestinal; MAOI, monoamine oxidase inhibitor; NSAID, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor; TCA, tricyclic antidepressant.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the pharmacist plays a pivotal role in helping patients exercise self-care and provides an effective screening mechanism for doctors. The continued deregulation of medicines to pharmacy control will mean that pharmacists over the coming years will be able to prescribe more medicines from more therapeutic classes. This necessitates that all pharmacists have up-to-date clinical knowledge and can competently perform the role. This might require many to acquire new skills (e.g. physical examinations) and take a much more active role in monitoring and following up the patient after advice and products have been given.

Key Points

Pharmacists have a traditional role in assisting patients with self-care

Pharmacists have a traditional role in assisting patients with self-care

Recent increases in patient self-care are government driven, consumer fuelled and professionally supported

Recent increases in patient self-care are government driven, consumer fuelled and professionally supported

It is estimated that 20–40% of GP consultations are for conditions which are suitable for self-care

It is estimated that 20–40% of GP consultations are for conditions which are suitable for self-care

Pharmacists require excellent consultation and communication skills in order to be effective in eliciting information from patients

Pharmacists require excellent consultation and communication skills in order to be effective in eliciting information from patients

When prescribing, first-line treatment should have proven efficacy

When prescribing, first-line treatment should have proven efficacy

Special considerations apply to children, the elderly and women who are pregnant or breast-feeding

Special considerations apply to children, the elderly and women who are pregnant or breast-feeding