Communication skills for pharmacists and their team

Introduction

Josie is a community pharmacist. At the end of the working day she thinks back to what has happened that day. She has discussed with customers their purchases of medicines; advised patients how to use their prescription medicines; conducted a medicines use review; phoned the local GP about a potential drug interaction; supervised a methadone addict; spoken briefly to the district nurse; negotiated with her boss about a day off; interviewed a potential sales assistant; exchanged pleasantries with the delivery person; and had been introduced to the new chairman of the local pharmaceutical committee at lunchtime.

Ravi, a hospital pharmacist, similarly looked back at his working day. He had spent time on the wards discussing drug-related matters with junior doctors; undertaken medication histories; and talked to a patient about their discharge medication. The latter task involved phoning the patient’s GP and local pharmacist to arrange a continuity of medicine supply. He had given a seminar for fellow pharmacists. Later he had attended a committee meeting, with other healthcare professionals and administrators on developing policies for the safe use of medicines. He had finished off his day supervising the dispensary, and dealing with a complaint from a prescriber.

From the above descriptions of two pharmacists’ very different working days, it can be seen that while each is performing pharmaceutical tasks, all of these tasks required the use of communication skills. In fact, almost everything we do in life depends on communication. Pharmacists spend a large proportion of each working day communicating with other people – patients, doctors, other healthcare professionals, staff and others. Poor communication has the potential to cause a range of problems, from misunderstandings with healthcare professionals to inappropriate or incomplete advice on the use of medication to a patient/customer.

Thus, there is a need for effective communication skills for pharmacists. But how effective is our communication? Good communication demands effort, thought, time and a willingness to learn how to make the process effective. Some people find that good communication is difficult to achieve and an awareness of this fact is an important first step to improvement.

This chapter considers some of the elements of successful communication, looking at our assumptions and expectations of people and at the processes involved in communication, listening and questioning skills. A total model for an effective pharmacist–patient consultation is outlined, followed by the barriers to effective communication in pharmacy. The importance of confidentiality is emphasized.

Assumptions and expectations

When we meet somebody for the first time, we make assumptions about that person. We often put people into categories and the assumptions lead to expectations of their behaviour, job and character.

This initial judgement of a person is often based purely on what we see and hear and includes appearance, demeanor, speech, dress, age, gender, race and physical disabilities. It is important that we are aware of these assumptions in order to avoid stereotyping people. For example, the impression we have of a person wearing a hooded jacket, baseball cap and jeans may be very different from that of the same person wearing a designer shirt and smart trousers.

What is communication?

Communication is more than just talking. It is generally agreed that in any communication, the actual words (the talking) convey only about 10% of the message. This is called verbal communication. The other 90% is transmitted by non-verbal communication which consists of how it is said (about 40%) and body language (about 50%).

The communication process

Argyle (1983) describes the message process as a sender encoding a message, which is then decoded by the receiver:

Mistakes can be made by both sender and receiver. The sender may not send the message they wished to send or they may sometimes intentionally seek to deceive. At the receiving end the message may not be decoded correctly. Poor communication skills contribute to these mistakes in encoding and decoding. Messages are not normally one way and if we send a message then we generally expect a reply, and so in replying the receiver becomes the sender and the sender becomes the receiver. While the messages may be going backwards and forwards between two people, effective communication becomes a helical model. In other words, what one person says influences how the other person responds in a spiral fashion with reiteration and repetition, coming back around the spiral.

Pharmacists tend to see contact with patients/customers as either getting information or imparting advice. However, this ignores the vital purpose of communication, which is to initiate and enhance the relationship with their patients/customers. If this can be achieved, then pharmacists will be perceived as more ‘patient friendly’ and more supportive of patients. Indeed, good communication skills will make it easier for a pharmacist to seek information and to advise patients.

Listening skills

Communication is not just about saying the right words; it involves listening correctly. If we do not listen properly, then it means we are not decoding the message that is being sent to us. However good the patient is at telling the pharmacist their symptoms, if the pharmacist does not listen correctly, then the patient may be given the wrong diagnosis, medicine or advice. Listening and hearing are different. Hearing is a physical ability, while listening is a skill. Listening skills enable a person to make sense of and understand what another person is saying. The listening process is an active one that consists of three basic steps, namely:

Hearing: listening enough to catch what the person is saying

Hearing: listening enough to catch what the person is saying

Understanding: understanding the message in his or her own way (this may not be what was intended by the speaker)

Understanding: understanding the message in his or her own way (this may not be what was intended by the speaker)

Judging takes the understanding stage and questions whether it makes sense. Do I believe what I have heard? Is it credible? Have I really understood what I have been told or have I misinterpreted the meaning?

Judging takes the understanding stage and questions whether it makes sense. Do I believe what I have heard? Is it credible? Have I really understood what I have been told or have I misinterpreted the meaning?

How to be a good listener

Listening, like other skills, takes practice. Tips for developing good listening skills are shown in Box 17.1.

Questioning skills

Pharmacists need effective questioning skills to obtain information from patients/customers. Examples of situations in which questioning skills are used include:

Requests for treatments for minor ailments

Requests for treatments for minor ailments

Probing a patient’s knowledge of how they take/use their medicines

Probing a patient’s knowledge of how they take/use their medicines

Effective questioning skills involve the use of different types of questions, namely open and closed questions.

Effective questioning should be used in assessing a patient’s presenting symptoms. The mnemonic ‘PQRST’ provides key questions which will help pharmacists to obtain an overview of symptoms, although additional questions can be added, for example, ‘Is the patient taking any concurrent medication?’ The PQRST approach to symptom analysis is shown in Box 17.2.

Questioning skills do not apply only to pharmacist– patient/customer situations. Good questioning skills are required in staff training, implementing procedures and other management tasks, as well as dealing with other healthcare professionals and administrative staff.

On many occasions, questioning may not be a face-to-face situation. Often, a pharmacist has to communicate by telephone with, e.g. another healthcare professional. The major drawback of this type of communication is that reliance is put solely on good verbal communication skills and not on the non-verbal aspect of communication. In these circumstances, it is vital to obtain the information as efficiently as possible. For example, when a GP phones to order a prescription medicine for a patient, the pharmacist is required to ask specific questions to ensure that all information is accurate. As another example, a patient phones about a prescription item – using good questioning skills, the pharmacist should check the prescription information, identify the patient’s concerns and be able to take appropriate action.

A model for guiding the pharmacist–patient interview

The Calgary–Cambridge model was developed in 1996 to aid the teaching of communication skills. Since that time, it has been adopted widely (see Ch. 18). The Calgary–Cambridge model is designed to specifically integrate communication skills with the content skills of traditional medical history and thus the approach can be used by pharmacists for their core tasks, such as drug history taking and the interviewing of patients to determine the best treatment for presenting minor ailments.

The Calgary–Cambridge model has five main stages:

Concomitantly, and alongside these stages, the model provides for two further ongoing stages:

Providing the structure to the interview involves:

Summarizing at the end of a line of enquiry to make sure there is mutual understanding between the pharmacist/prescriber and the patient/customer, before continuing

Signposting – in other words indicating to the patient when moving from one section to the next, e.g. gathering information and explaining

Sequencing – this means developing a logical sequence which is apparent to the patient, in other words do not interrupt information gathering to explain and then go back to information gathering

Timing – this means keeping to agreed time, being able to close the session and not having to close abruptly because the time has run out.

Building the relationship during the interview involves:

Developing rapport – being aware of non-verbal behaviour clues and involving the patient in the interview process. Developing rapport has four areas:

Acceptance of the patient, their views and feelings and being non-judgemental

Acceptance of the patient, their views and feelings and being non-judgemental

Empathy with the patient by showing an understanding and appreciation of the patient’s feelings or predicament

Empathy with the patient by showing an understanding and appreciation of the patient’s feelings or predicament

Support which expresses itself as concern for the patient, a willingness to help, an acknowledgement of their coping efforts and self-care, e.g. use of OTC medicines, and offering a partnership approach

Support which expresses itself as concern for the patient, a willingness to help, an acknowledgement of their coping efforts and self-care, e.g. use of OTC medicines, and offering a partnership approach

Sensitivity, which includes dealing sensitively with embarrassing and disturbing topics.

Sensitivity, which includes dealing sensitively with embarrassing and disturbing topics.

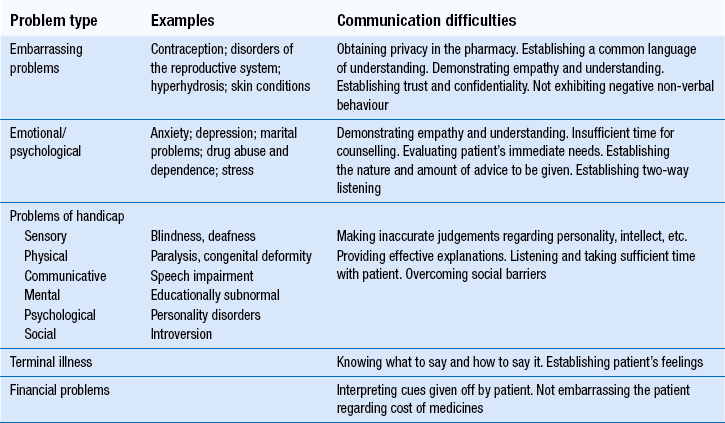

Some sensitive areas can be seen in Table 17.1.

An awareness of non-verbal behaviour is the next step in building the relationship. The awareness relates to the interviewers themselves – Are they demonstrating good eye contact and other features of positive non-verbal behaviour? Are they picking up on any cues displayed by the patient’s non-verbal behaviour? Any note taking or reading (or use of computers) should not interrupt or affect the dialogue.

In building the relationship, it is important to involve the patient and to share thoughts with them (e.g. ‘I think we are looking for a medicine that doesn’t cause drowsiness’), to provide a rationale for questions (e.g. explain why you need to know about concurrent prescribed medicines when recommending an OTC cough medicine), and to explain and ask permission if a physical examination is necessary.

We will now consider in more detail the stages of the interview process relevant to current pharmacy practice, according to the Calgary–Cambridge model.

Initiating the session

Preparation involves the interviewer (the pharmacist) preparing him- or herself and focusing on the session. The pharmacist will need to focus on meeting the patient. It is important to establish initial rapport by greeting the patient, introducing yourself, the role and nature of the interview (e.g. a pharmacist conducting a drug medication history) and obtain consent, if necessary. The next step is to identify the reasons for the consultation by an opening question such as, for a patient requesting to see the pharmacist, ‘I understand that you would like to speak to me – how can I help?’ The patient’s answer must be listened to attentively and then the pharmacist needs to check and confirm the list of problems/queries/issues with the patient. During this stage, the pharmacist should pick up on any verbal and non-verbal behaviour cues and help facilitate the patient’s responses. To complete this stage, an agenda for the interview is negotiated (e.g. ‘So you would like me to recommend a medicine to help relieve your cough that doesn’t make you drowsy? Is that right?’).

Gathering information

An initial exploration of the patient’s problems, either disease or illness, is necessary and the patient should be encouraged to ‘tell their tale’ in their own words. The pharmacist needs to listen attentively and question appropriately (open and closed questions) and suitable use of language (e.g. avoiding jargon and very technical language). The pharmacist needs to be aware of verbal and non-verbal cues and the possible need to facilitate responses. It may be necessary to clarify what the person is saying (e.g. ‘What do you exactly mean by a stomach cold?’). Certainly it will be necessary to periodically summarize to check your own understanding of what the patient has said. This summarizing also allows the patient to correct any misinterpretation. A further exploration of the disease framework may be necessary and this may include symptoms analysis (see, e.g. the PQRST symptoms analysis in Box 17.2), and more focused closed questions. The patient’s perspective is taken into account by the Calgary–Cambridge model at this stage in the interview, when a further exploration of the illness from the patient’s perspective is undertaken. This further exploration investigates the following:

The patient’s ideas and concerns, i.e. the patient’s beliefs on the causes of the illness and their concerns about each problem, e.g. the idea that taking medicines might make them addicted to the medicine

The patient’s ideas and concerns, i.e. the patient’s beliefs on the causes of the illness and their concerns about each problem, e.g. the idea that taking medicines might make them addicted to the medicine

The effects on the patient’s life of each problem, e.g. concern that a medicine may make them too drowsy to drive

The effects on the patient’s life of each problem, e.g. concern that a medicine may make them too drowsy to drive

The expectations of the patient, e.g. that a medicine will instantly make them better

The expectations of the patient, e.g. that a medicine will instantly make them better

The patient’s feelings and thoughts about the problems, e.g. feeling that no medicine is strong enough to take away the symptoms.

The patient’s feelings and thoughts about the problems, e.g. feeling that no medicine is strong enough to take away the symptoms.

The above are important and may indicate if a patient is unwilling to take, or is untrusting of, modern medicines. They may also indicate that the drug regimen and formulation would be totally unsuitable for the patient and should be changed. These are important issues for compliance and concordance (see Ch. 18).

Explanation and planning

This is the next stage of the interview, which has three areas, all of which are very appropriate to pharmacists (see Ch. 25):

1. To provide the correct amount and type of information

To give comprehensive and appropriate information

To assess each individual patient’s information needs and to neither restrict nor overload

To make information easier for the patient to remember and understand.

2. To achieve a shared understanding: incorporating the patient’s illness framework (see Ch. 3)

All of the above stages, although designed for medical interviews, are very relevant to pharmacists. Patients need to be involved in decisions about any treatment with medicines, and they need to be given sufficient information on what the medicine is used for and how to take it, in a way that is achievable in their lifestyle. Also, patients should be offered some information on side-effects, so that they can make an informed choice (see Ch. 18).

Closing the session

At the end of the session, it is important to summarize what has taken place and the joint decisions made. The patient should also be informed about the next stage; for example this could be seeing how the medicine works and coming back to the pharmacy if the patient feels the medicine is not working. Ensure the patient knows what to do if the problem/symptoms do not resolve (e.g. go to see the doctor), and finally, check whether the patient agrees and feels comfortable with the chosen plan or needs to discuss any other issues.

Patterns of behaviour in communication

A number of terms are used in connection with behaviour during communication:

Assertive behaviour may be defined as standing up for personal rights and expressing thoughts, feelings and beliefs in direct, honest and appropriate ways which do not violate another person’s rights. Being assertive involves listening to others and understanding their feelings. People who behave assertively deal with other people as equals. An assertive communicator will find a mutually acceptable solution. An important part of being assertive, therefore, is to formulate your aims and objectives clearly.

Assertive behaviour may be defined as standing up for personal rights and expressing thoughts, feelings and beliefs in direct, honest and appropriate ways which do not violate another person’s rights. Being assertive involves listening to others and understanding their feelings. People who behave assertively deal with other people as equals. An assertive communicator will find a mutually acceptable solution. An important part of being assertive, therefore, is to formulate your aims and objectives clearly.

Aggressive behaviour violates others’ rights as the aggressive person seeks to achieve goals at the expense of others. Aggressive behaviour is often frightening, threatening and unpredictable. It will bring out negative feelings in the receiver and communication will be difficult.

Aggressive behaviour violates others’ rights as the aggressive person seeks to achieve goals at the expense of others. Aggressive behaviour is often frightening, threatening and unpredictable. It will bring out negative feelings in the receiver and communication will be difficult.

Passive–aggressive behaviour usually involves a person giving a mixed message; that is, he may agree with what you are saying but then raise his eyebrows and pull a face at you behind your back.

Passive–aggressive behaviour usually involves a person giving a mixed message; that is, he may agree with what you are saying but then raise his eyebrows and pull a face at you behind your back.

Submissive behaviour is displayed by people who behave submissively, have very little confidence in themselves and show poor self-esteem. They often allow others to violate their personal rights and take advantage of them.

Submissive behaviour is displayed by people who behave submissively, have very little confidence in themselves and show poor self-esteem. They often allow others to violate their personal rights and take advantage of them.

Assertiveness is a positive way of relating to other people – a means of communicating as effectively as possible, particularly in potentially awkward situations. Assertive behaviour is useful when dealing with conflict, in negotiation, leadership and motivation, when giving and receiving feedback, in cooperative working and in meetings. Assertive communication can give the user confidence, and a feeling of more control over situations.

People who behave assertively usually achieve what they set out to do. This is in comparison to those who act aggressively, who think that they have achieved their goal – but usually at the cost of respect and loyalty from those around them. Submissive people rarely achieve what they want.

Barriers to communication

In a pharmacy setting, there are a number of factors which can be of benefit to, or can detract from, the quality of any communication. Common barriers which exist can be identified under four main headings:

Environment

Community and hospital pharmacies and hospital wards are some of the areas where pharmacists use their communication skills in a professional capacity. None of these areas is ideal for good communication, but an awareness of the limitations of the environment goes part of the way to resolving the problems. Some examples of potential problem areas are illustrated below.

A busy pharmacy

This may create the impression that there appears to be little time to discuss personal matters with patients. The pharmacist may appear to be too busy to devote his full attention to an individual matter. It is important that pharmacists organize their work patterns in such a way as to minimize this impression.

Lack of privacy

For good communication to occur and rapport to be developed, it should take place in a quiet environment, free of interruptions All pharmacies, whether hospital or community, should have counselling rooms or areas. Lack of these facilities, such as in a busy hospital ward, requires additional communication skills.

Noise

Noise within the working environment is an obvious barrier to good communication. People strain to hear what is said, comprehension is made more difficult and particular problems exist for the hearing impaired. Conversely, a patient may feel embarrassed having to explain a problem in a totally quiet environment where other people can ‘listen in’.

Physical barriers

Pharmacy counters and dispensing hatches are physical barriers which may dictate the distance between pharmacist and patient. This can create problems in developing effective communication. Similarly, a patient in bed (or in a wheelchair) and a pharmacist standing offers a different sort of barrier for effective communication. Ideally, faces should be at about the same level.

Patient factors

One of the main barriers to good communication in a pharmacy can be patients’ expectations. They may not expect the pharmacist to spend time with them checking their understanding of medication or other health-related matters. However, once the purpose of the communication is explained, most patients realize its importance and are quite happy to enter into a dialogue.

Patients with hearing and sight impairment

Such patients must be considered carefully when adopting questioning skills. Sight-impaired people will have difficulty or may not be able to read any written material, unless it is in Braille. Special Braille labels are available. Many customers who come into pharmacies will suffer from a degree of hearing impairment. Recognizing the profoundly deaf is usually simpler than recognizing those who have hearing impairment.

A person with hearing difficulty is likely to do one or more of the actions listed in Box 17.3. Having recognized a customer with hearing impairment, the guidelines in Box 17.4 are helpful. Listening, and being able to demonstrate that you are listening by using non-verbal responses, e.g. nods of the head, is very important for customers with hearing loss.

Comprehension difficulties

Not all people come from the same educational background or have the same native language and care must be taken to assess a patient’s level of understanding and choose appropriate language. Information leaflets in appropriate languages can be provided for patients with language difficulties and pharmacists may be able to access translator services from local primary care organizations.

Illiteracy

A significant proportion of the population, both in the UK and in other countries, is illiterate. For these patients, written material is meaningless. It is not always easy to identify illiterate patients, but additional verbal advice can be given and pictorial labels can be used. For example the United States Pharmacopoeia has designed a range of pictograms for this purpose.

The pharmacist and their team

Not everybody is a natural, good communicator. Identifying strengths and weaknesses will assist in improving communication skills. Some of the weaknesses which can be barriers to good communication are:

Delegation of responsibilities to untrained staff

Delegation of responsibilities to untrained staff

If any of these characteristics is present, the reason for it should be identified and resolved, if possible.

Confidentiality

Matters related to health and illness are highly private affairs. Therefore it is important that privacy and confidentiality are assured in the practice of pharmacy.

The public expects pharmacists to respect and protect confidentiality and have premises that provide an environment where you can communicate privately without fear that personal matters will be disclosed. This concerns the whole staff of the pharmacy, not just the pharmacists.

Time

In many instances, time, or the lack of it, can be a major constraint on good communication. It is always worthwhile checking what time people have available before trying to embark on any communication. That way, you will make the best use of what time is available.

Not all barriers to good communication can be removed, but an awareness that they exist and taking account of them will go a long way towards diminishing their negative impact.

Conclusion

Good communication is not easy and needs to be practised. We all have different personalities and skills, which mean that we have strengths in some areas and weaknesses in others. If we can become aware of, and maximize, our strengths and work to minimize our weaknesses, we will become better communicators. Being articulate and able to explain things clearly is of great importance to a pharmacist. However, listening with understanding and empathy is of equal, and in certain situations of greater, importance. We may all hear the words being said, but are we really listening to the complete message?

Key Points

Communication consists of both verbal and non-verbal communication

Communication consists of both verbal and non-verbal communication

Assertive behaviour treats other people as equals, and is not to be confused with aggressive behaviour, which violates other people’s rights

Assertive behaviour treats other people as equals, and is not to be confused with aggressive behaviour, which violates other people’s rights

Questioning and listening skills are equally important

Questioning and listening skills are equally important

In the working environment there are many potential barriers to effective communication, including the environment, patient and pharmacist and the time implications

In the working environment there are many potential barriers to effective communication, including the environment, patient and pharmacist and the time implications

Confidentiality must be assured in the practice of pharmacy

Confidentiality must be assured in the practice of pharmacy

Pharmacists need to maximize their strengths and minimize their weaknesses of communication

Pharmacists need to maximize their strengths and minimize their weaknesses of communication