Communication skills

advice and information on the selection of medicines

The rationale and need for giving information and advice

The rationale and need for giving information and advice

Situations suitable for pharmaceutical information and advice

Situations suitable for pharmaceutical information and advice

Assessing the need for giving information and advice

Assessing the need for giving information and advice

How to decide on the content and method of giving information and advice

How to decide on the content and method of giving information and advice

Introduction

Pharmacists have always provided information and advice on the use of medicines. The Nuffield Report (1968) recognized that there were ‘some categories of individuals who certainly will need advice, help and encouragement in the handling of their medicines’ and that ‘anyone who has to rely on a continuous drug regime, should be a candidate for additional support and help from pharmacies’. These statements highlight the traditional role of the pharmacist in the provision of advice to patients/customers.

The NHS Plan 2000 in the UK outlined the need for pharmacists to become more involved in helping patients to get the best from their medicines. The aim was to ‘Give patients the confidence that they are getting good advice when they consult a pharmacist’. The introduction of MURs and the new medicine service (NMS), further develops the pharmacists role in advice and information giving. Other examples of advice giving by pharmacists include when handing out prescription medicines, selling OTC medicines, on hospital discharge and during medication reviews.

Medicines research has led to the production of new, effective drugs formulated in many specialised dosage forms, such as modified-release formulations, aerosols, patches, nail lacquers, etc. which utilize conventional and other absorption routes (e.g. percutaneous, nasal and vaginal) (see Ch. 29). Often these medicines are packaged in specialized containers, for example aerosols for rectal use, self-administration parenteral products, metered-dose nasal sprays. These developments mean that pharmacists are in an excellent position to provide advice to patients/consumers on how to correctly use/administer these medicines in as safe a manner as possible.

What is information and advice giving in pharmacy?

Patients and customers have a right to be involved in the decisions about their treatment and their use and choice of medicines (see Ch. 18). Thus, pharmacists require effective communication skills to be able to identify the individual needs of a patient/customer and to determine the type and amount of advice and level of explanation appropriate to provide at that particular time.

The BNF uses the term ‘counselling’ rather than advice in individual monographs to detail the type of advice to be given to a patient. Such advice is above that required on the label of a dispensed product and usually involves unusual/complicated methods or times of administration or the potential interaction with foods. For example, bulk-forming laxatives have the counselling statement, ‘Preparations that swell in contact with liquid should always be carefully swallowed with water and should not be taken immediately before going to bed’.

The need for information and advice giving

It has been estimated that up to 50% of older people do not take their medicines as intended. Similarly, 50% of patients (not necessarily older people) with hypertension fail to take their medicines correctly. Thus, it has been suggested that advice by pharmacists could lead to better compliance and hence less therapeutic failure and possible death.

The aims of information and advice

Pharmacists in their patient-advising roles may adapt and make use of the problem-solving model of counselling developed by Egan (1990).

Thus the aims, in addition to the provision of advice, could be to:

Encourage patients to identify any problems they perceive with medicines and also any solutions to these problems

Encourage patients to identify any problems they perceive with medicines and also any solutions to these problems

Encourage patients to develop their own action plan for taking/using medicines correctly

Encourage patients to develop their own action plan for taking/using medicines correctly

Gain an understanding of the patient’s perspective

Gain an understanding of the patient’s perspective

Respect the patient’s beliefs and be non-judgemental of their use (or non-use) of medicines.

Respect the patient’s beliefs and be non-judgemental of their use (or non-use) of medicines.

Opportunities for giving information and advice

The pharmacist is often the last healthcare professional whom a patient sees before starting drug therapy. It is at this stage that the pharmacist should identify the information and advice needs of the patient. Pharmacists should take a prominent and proactive role. The opportunities for giving information and advice to patients are many, but the main opportunity is at the end of the dispensing process, the sale of a medicine, during a MUR or NMS opportunity (see Ch. 14).

No patient should receive a dispensed medicine without the pharmacist making an assessment of the needs of the patient. The availability of PMRs and the information contained within them will underpin the extent and type of information and advice provided to an individual patient.

The sale of medicines from a community pharmacy can be the result of: (a) a direct request for a named medicine by a customer and (b) a request for advice on the treatment of a symptom or minor ailment by a patient. The amount and content of the information and advice given to a patient will vary with the type of initial request, the medicine sold and the patient.

Thus, the opportunities for community pharmacists to become involved in patient advice are wide ranging. Other possible areas include:

Visits to care/residential/nursing homes

Visits to care/residential/nursing homes

Public health (see Ch. 13)

Public health (see Ch. 13)

Special weeks/days, e.g. Asthma Week, Breast Awareness Week, Stop Smoking Day

Special weeks/days, e.g. Asthma Week, Breast Awareness Week, Stop Smoking Day

Pet medicines (see Ch. 28).

Pet medicines (see Ch. 28).

Similarly, there are many opportunities for hospital pharmacists. Inpatients may require advice on their medicines during admission and should be made fully aware of any alterations in their medication on discharge. Outpatients will, also, require advice on newly prescribed medicines.

Pharmacists may be involved in providing medication to patients in long-term residential homes. In such situations it may be necessary to give information and advice to both the patient and/or their carers.

How to provide information and advice

Information and advice giving, wherever it occurs, should take place in a thoughtful, structured way. The pharmacist must possess not only a sound knowledge of the drugs and appliances being dispensed or sold, but also excellent communication skills. Pharmacists should be able to provide information and advice in a non-paternalistic way that allows the patient to ask questions in order to understand the information, so that they can make decisions about their own treatment and care. Pharmacists must have the ability to explain information clearly and unambiguously and in language the recipient can understand. They must know the right questions and how to ask them and, most importantly, they must know how to listen. For information and advice giving to be successful, it must be a two-way process. Rapport is built-up between the pharmacist and the patient and a much more meaningful dialogue can take place.

The Cambridge–Calgary model (see Chs 17 and 18) details how to provide explanations to patients. It is important to provide the correct amount and type of information:

Chunks and checks. The information needs to be given in suitable bite-sized chunks. Observation of patient response should indicate whether the chunks are too small or too large and thus further chunks of information can be adjusted to suit the patient.

Chunks and checks. The information needs to be given in suitable bite-sized chunks. Observation of patient response should indicate whether the chunks are too small or too large and thus further chunks of information can be adjusted to suit the patient.

Assess the patient’s starting point. How much do they know? This should be assessed early on in the session.

Assess the patient’s starting point. How much do they know? This should be assessed early on in the session.

Ask patients what information would be helpful. For example, a patient may be more concerned about the immediate effects of the drug on their lifestyle rather than the long term.

Ask patients what information would be helpful. For example, a patient may be more concerned about the immediate effects of the drug on their lifestyle rather than the long term.

Give explanations at an appropriate time. Avoid giving advice or information prematurely.

Give explanations at an appropriate time. Avoid giving advice or information prematurely.

To help the patient recall and understand the advice/information that you provide, the pharmacist should:

Organize the explanation. Try to develop a logical sequences and discrete sections – do not combine information on side-effects with how to administer the medicine.

Organize the explanation. Try to develop a logical sequences and discrete sections – do not combine information on side-effects with how to administer the medicine.

Use signposting – in other words, if there are three points to get over, say so, and continue with first …, second …, etc.

Use signposting – in other words, if there are three points to get over, say so, and continue with first …, second …, etc.

Use easily understood and concise language. Avoid using jargon, abbreviations and technical terms where possible.

Use easily understood and concise language. Avoid using jargon, abbreviations and technical terms where possible.

Use visual methods of explanation. Demonstration models of pharmaceutical packaging can be useful, e.g. aerosols.

Use visual methods of explanation. Demonstration models of pharmaceutical packaging can be useful, e.g. aerosols.

Check patient understanding at regular intervals. Ask the patient to explain to you or to demonstrate the use of a medicine.

Check patient understanding at regular intervals. Ask the patient to explain to you or to demonstrate the use of a medicine.

What information to include

Each situation and each patient will have different information needs, but as a general summary, no patient who has been given medication should leave a community or hospital pharmacy without knowing:

How to take or use the medicine

How to take or use the medicine

When to take or use the medicine

When to take or use the medicine

How long to continue to take or use

How long to continue to take or use

What to expect, e.g. immediate relief, no effect for several days

What to expect, e.g. immediate relief, no effect for several days

Why the medicine is being taken or used

Why the medicine is being taken or used

What to do if something goes wrong, e.g. if a dose is missed

What to do if something goes wrong, e.g. if a dose is missed

How to recognize side-effects and minimize their incidence

How to recognize side-effects and minimize their incidence

Lifestyle changes which need to be made

Lifestyle changes which need to be made

Dietary changes which need to be made

Dietary changes which need to be made

How to obtain further supplies of the medication if appropriate.

How to obtain further supplies of the medication if appropriate.

Who to give advice and information to

Not every patient will require information and advice but it is important that pharmacists can correctly identify those who do by, first, considering the medication.

A multiple-item prescription may present problems to the patient in terms of different drugs, different dosage forms and regimens, etc. Additionally, the individual medicine on any prescription, because of its characteristics, e.g. complex dosage regimen, special delivery methods, novel packaging, etc., may require explanation to ensure the patient has a clear understanding of how to use it.

Other reasons for giving advice/information will be if the drug has:

A narrow therapeutic index. The need for strict adherence to dosing should be emphasized. Drugs such as lithium or theophylline are common examples

A narrow therapeutic index. The need for strict adherence to dosing should be emphasized. Drugs such as lithium or theophylline are common examples

The potential for interaction with another drug. (See Appendix 1 in the BNF.)

The potential for interaction with another drug. (See Appendix 1 in the BNF.)

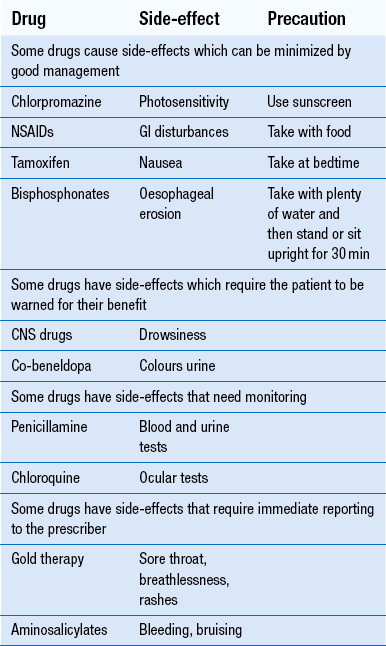

The potential to cause side-effects. The patient should be told not only how to recognize the side-effects, but also how to reduce the incidence or severity of them and what to do if they occur (see Table 25.1). Select the side-effects which are most likely to occur and advise on them

The potential to cause side-effects. The patient should be told not only how to recognize the side-effects, but also how to reduce the incidence or severity of them and what to do if they occur (see Table 25.1). Select the side-effects which are most likely to occur and advise on them

A cautionary and advisory label (BNF Appendix 3) should be attached to the medicine. The information on these labels should always be reinforced.

A cautionary and advisory label (BNF Appendix 3) should be attached to the medicine. The information on these labels should always be reinforced.

Second, consider the patient. The level and type of information given and how it is given will depend on a variety of factors:

Is the patient known at the pharmacy and have they been identified previously as having problems with drug therapy?

Is the patient known at the pharmacy and have they been identified previously as having problems with drug therapy?

What information/advice has the patient previously received?

What information/advice has the patient previously received?

What are the patient’s comprehension levels?

What are the patient’s comprehension levels?

What level of support does the patient need or have?

What level of support does the patient need or have?

The age of the patient. In general, all patients who are elderly should be offered information and advice. If the prescription is for a child, the parent or guardian should be given advice.

The age of the patient. In general, all patients who are elderly should be offered information and advice. If the prescription is for a child, the parent or guardian should be given advice.

Is the patient pregnant or breast-feeding? Such patients may require reassurance that the therapy is safe to take. Similarly, a breast-feeding mother may require advice on when to take the medication so that it least affects the child.

Is the patient pregnant or breast-feeding? Such patients may require reassurance that the therapy is safe to take. Similarly, a breast-feeding mother may require advice on when to take the medication so that it least affects the child.

Does the patient have physical disabilities? These could include mobility problems, causing problems in opening containers, blindness or deafness.

Does the patient have physical disabilities? These could include mobility problems, causing problems in opening containers, blindness or deafness.

Does the patient have mental disabilities? These could include states of confusion, anxiety or forgetfulness. Limited intellectual capacity could lead to patients being unable to read labels, etc. or understanding instructions.

Does the patient have mental disabilities? These could include states of confusion, anxiety or forgetfulness. Limited intellectual capacity could lead to patients being unable to read labels, etc. or understanding instructions.

Other instances which should alert the pharmacist to the need for advice/information would be:

The purchase by a patient of an OTC product, which is incompatible with the prescribed medication, e.g. a patient with hypertension who is taking atenolol and wishes to purchase pseudoephedrine for nasal congestion.

The purchase by a patient of an OTC product, which is incompatible with the prescribed medication, e.g. a patient with hypertension who is taking atenolol and wishes to purchase pseudoephedrine for nasal congestion.

A patient asking for an item not to be dispensed. This could indicate that the patient is non-compliant with that medication.

A patient asking for an item not to be dispensed. This could indicate that the patient is non-compliant with that medication.

A patient asking to buy an OTC medicine which is to relieve the side-effects of a prescribed medicine. An example of this would be when a patient who is being prescribed NSAIDs asks for an indigestion remedy. This should be investigated.

A patient asking to buy an OTC medicine which is to relieve the side-effects of a prescribed medicine. An example of this would be when a patient who is being prescribed NSAIDs asks for an indigestion remedy. This should be investigated.

Stages in the information/advice giving process

If information and advice giving is approached in a structured manner, then the time will be used efficiently and there will be a greater likelihood of success. The following stages have been adapted from the guidelines on Counselling and Advice on Medicines and Appliances in Community Pharmacy Practice produced by the Scottish Office Clinical Research and Audit Group:

Recognizing the need for counselling

Recognizing the need for counselling

Assessing and prioritizing the needs

Assessing and prioritizing the needs

Recognizing the need for information and advice

The pharmacist will need to consider the content of the prescription and the characteristics of the patient.

Are the instructions clear?

It is the pharmacist’s responsibility to make sure that the patient knows what instructions such as ‘when necessary’ or ‘as directed’, mean. In the UK, the Human Medicines Regulations 2012, allow a pharmacist to put detailed directions onto a label where the prescriber has written ‘as directed’ on the prescription.

Assessing and prioritizing the needs

Although all individuals should be considered for information and advice, there will be some for whom little or none is required. For example, a customer who asks for an OTC by name and has used it successfully on several previous occasions may require minimal information and advice. Giving information and advice is time-consuming and so pharmacists should concentrate their time and efforts on those patients requiring it. Also, the pharmacist may have to be selective in what advice is given to a patient. The average number of facts which can be retained at any one time by most individuals is three. Box 25.1 illustrates this point.

Specifying assessment methods

It cannot be assumed that because the information and advice has been given, that the patient understands or is able to adhere to that advice. It is, therefore, important that, before embarking on any information advice giving process, the pharmacist has an idea how the success of the process can be measured.

This assessment could consist of checking that the patient can read the label, use an inhaler device or open a container with a child-resistant cap. Checking on understanding may require follow-up, such as an enquiry the next time the patient visits the pharmacy, to ensure that no problems have occurred and the response to the therapy is as expected.

Implementation

The appearance of the pharmacy and pharmacist are important and it should be apparent that information and advice are offered as a professional service.

Lack of time is a major barrier to good information and advice giving. Patients should be given an indication of why you wish to speak to them and you should always check that they have the time to listen. If the patient is unknown to the pharmacist, it is important at the beginning of the conversation to try to gauge not just the amount of information that is needed but also the patient’s level of comprehension. Is the patient fluent in the language or are they hard of hearing? The information/advice giving process must not be a monologue by the pharmacist, giving a long list of information points. There should be ample opportunity for the patient to ask questions.

Assessing the success of the process

Having given the information, it is then of major importance to check if the process has been successful. What does the patient understand? Can he use his device? Does he have any problems? The ideal, where possible, is to assess compliance/concordance through follow-up.

During the information and advice giving process, the pharmacist should check if the patient understands the information imparted. Watching the patient’s body language and maintaining eye contact can give useful clues as to whether the message is being understood and whether compliance/concordance is likely.

Aids to information and advice giving

Patient information leaflets (PIL), warning cards and placebo devices are all useful aids when giving advice to patients. All patient packs of medicines contain a PIL. These should be used where appropriate and important points highlighted. Placebo devices can be used to demonstrate a particular technique and also to check a patient’s ability to use a device. Leaflets on how to use ear drops, eye drops, eye ointment, pessaries, suppositories, a nebulizer, malaria tablets and head louse lotions are available. These, along with warning cards for anticoagulant therapy, lithium, monoamine oxidase inhibitors and steroids should be available in all pharmacies. The use of Braille labels and pictograms should be considered for the vision impaired and illiterate, respectively.

An example

The following example illustrates the wide variety of issues which have to be dealt with by pharmacists. It is not intended to be comprehensive, as different situations and different patients will produce a variety of problems and issues.

Recognize the need for information and advice

Mrs Myrtle has not been prescribed the tablets before, therefore drug name and dose timings should be given.

NSAIDs can cause GI irritation if not taken with or after food. The warning label which indicates this will need to be reinforced.

Mrs Myrtle appears to have problems with her hands. Will she be able to open a bottle with a child-resistant cap? She lives alone, so does not have anyone to help her.

Has she been buying any OTC medication to try to alleviate the pain in her hands? Some of the OTC products available for relief of arthritic pain contain diclofenac or other NSAIDs.

Mrs Myrtle will need to be advised to swallow the tablets whole and not to chew them. Will she be able to swallow them whole? Other formulations of diclofenac are available and may need to be considered for this patient.

Assessing and prioritizing the information and advice needs

Compliance problems

It is important to ensure that Mrs Myrtle can open the container and that she will have no difficulty swallowing the tablets.

Side-effects

It is vitally important to alert Mrs Myrtle to the fact that the tablets may irritate her stomach and how she can avoid this.

OTC purchases

To avoid any duplication of drug therapy it is important to find out if Mrs Myrtle is taking any OTC medicines, what they are, and make sure they are not going to cause any problems.

Timing of doses and duration of treatment

Mrs Myrtle should be told that the NSAID tablets should give pain relief within 1 week and successful anti-inflammatory action should be seen within 3 weeks. The drug must be taken at regular intervals.

A simple demonstration with a child resistant container will identify if she needs a container with a plain cap fitted. If swallowing is identified as a problem, she can be reassured that alternative therapy is available in liquid or granular form. It may then be necessary to contact the prescriber to alert him to this.

Any potential OTC problems can be dealt with by simple questioning.

Mrs Myrtle should be invited to let you know how she is getting on with her tablets and to contact you if she has any queries.

Conclusion

Develop the habit of thinking about medicines from the patient’s point of view. What do patients need to know? What are their concerns about taking the medicine? What can be done to help patients resolve their concerns? Identifying information and advice giving points from the information at your disposal is fundamental to good pharmacy practice. It is important to remember, however, that asking questions and listening carefully to the information provided by patients is critical to the success of the process.

Key Points

Advice/information giving is an important part of the role of the pharmacist

Advice/information giving is an important part of the role of the pharmacist

The prescription is a useful guide to possible information and advice needs of the patient

The prescription is a useful guide to possible information and advice needs of the patient

The extent to which patients should be told about side-effects will vary from one patient to another

The extent to which patients should be told about side-effects will vary from one patient to another

It may be necessary to limit the amount of information given to avoid confusion

It may be necessary to limit the amount of information given to avoid confusion

Checking is important in ensuring patient understanding

Checking is important in ensuring patient understanding

Information and advice giving is not a lecture – patients must be given the opportunity to ask questions

Information and advice giving is not a lecture – patients must be given the opportunity to ask questions