Substance use and misuse

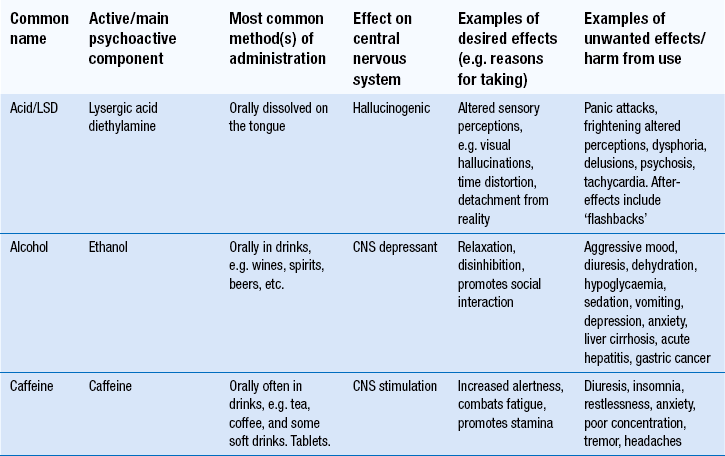

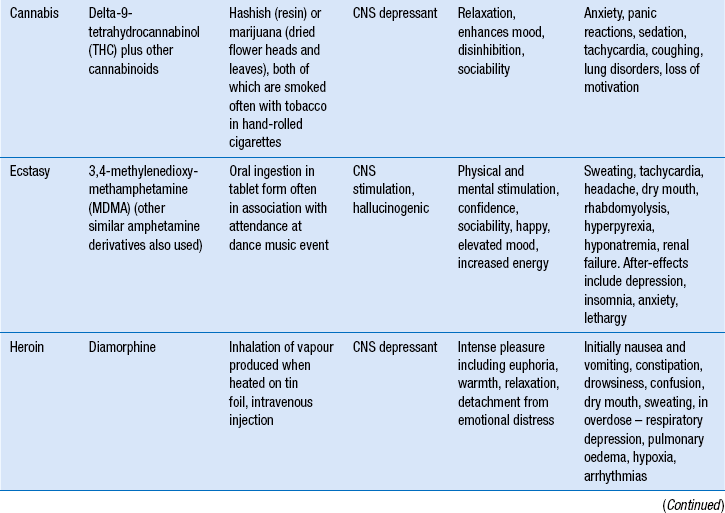

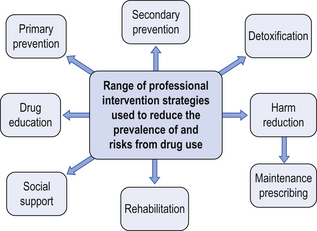

The main psychoactive substances taken for non-medicinal purposes

The main psychoactive substances taken for non-medicinal purposes

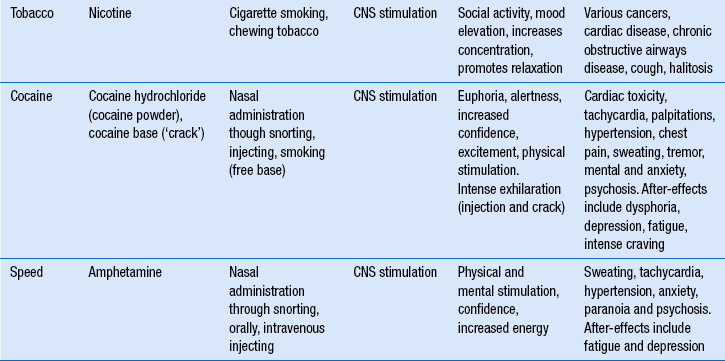

The range of professional interventions used in the field of substance misuse

The range of professional interventions used in the field of substance misuse

The aim of pharmaceutical interventions and their operation

The aim of pharmaceutical interventions and their operation

Key factors to consider when providing pharmaceutical care to people with drug misuse problems

Key factors to consider when providing pharmaceutical care to people with drug misuse problems

Introduction

This chapter begins with some background information before it summarizes current thinking on drug misuse and drug dependence. It then looks at treatment provision in the UK and the range of interventions used, focussing on the practical provision of the two main pharmaceutical interventions: needle exchange and substitute pharmacotherapy provision.

Terminology

Terminology used in the field of drug misuse can be confusing, even for those who work in the area. There are political and philosophical differences behind the use of various terms, a discussion of which is outside the scope of this work. However, it is important to be aware that a variety of terms essentially refer to the same things.

‘Drug use’ in the context of this chapter, is the term commonly used to refer to the consumption of psychoactive substances without medical or healthcare instruction. The term ‘drug misuse’ refers to drug use that is problematical and incurs significant risk of harm. These two terms are often used interchangeably. ‘Drug abuse’ essentially refers to the same thing but its use is less common in recent publications. ‘Substance’ is sometimes used in place of ‘drug’ to include non-medicinal chemicals such as solvents, alcohol and nicotine.

‘Dependence’ or ‘addiction’ refers to the compulsion to continue administration of psychoactive substance(s) in order to avoid physical and/or psychological withdrawal effects. Dependence syndrome is defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as:

A cluster of behavioural, cognitive, and physiological phenomena that develop after repeated substance use and that typically include a strong desire to take the drug, difficulties in controlling its use, persisting in its use despite harmful consequences, a higher priority given to drug use than to other activities and obligations, increased tolerance, and sometimes a physical withdrawal state. The dependence syndrome may be present for a specific psychoactive substance (e.g. tobacco, alcohol, or diazepam), for a class of substances (e.g. opioid drugs), or for a wider range of pharmacologically different psychoactive substances.

Dependence can be classified in more detail, as found in the Shorter Oxford Textbook of Psychiatry.

‘Drug user’ is commonly used to refer to someone who participates in drug/substance use. The term ‘drug misuser’ refers to someone undertaking drug use in such a way that it is problematical and presents significant risk of harm. The two terms tend to be used interchangeably. Terms such as ‘drug addict’ and ‘drug abuser’ are less used in recent literature.

Historical note

Historical works on psychoactive drug consumption make interesting reading and help us to understand how current drug policy came to be formulated. They indicate that psychoactive drug use is not a new phenomenon in society – psychoactive drug use has been recorded as part of some societies more than 7000 years ago.

Substances that are used and their effects

Table 50.1 lists some commonly used psychoactive substances in western societies and summarizes their effects. (Nicotine is included for completeness: the role of the pharmacist in smoking cessation is covered in Ch. 48). The unwanted and harmful effects of some drugs relate to prolonged and excessive use, whereas others occur with single doses of smaller amounts. The method of administration also influences the extent of the risks, e.g. injecting opiates presents greater health risks than taking them by vaporization (‘chasing the dragon’). Table 50.1 is presented as a guide, but it is not comprehensive.

Why do people use psychoactive drugs?

Benefits

Why people use psychoactive drugs is a multifaceted question to which there is no simple answer. As a crude summary, people do so because they expect to experience a benefit in some way. Any awareness of risks is weighed up against the perceived benefits and the decision to take the drug prevails.

The expected or perceived benefits may include: the attainment of pleasurable feelings (e.g. relaxation); increased social interaction (e.g. reduced inhibitions); alteration of the person’s psychological condition to a more desirable state (e.g. escapism); physical change (e.g. anabolic steroids taken by bodybuilders) or avoidance of withdrawal symptoms in someone who is dependent on a drug. The reasons for use may change over time with the same user, e.g. opiate use may be commenced to escape from reality but then continued to avoid the withdrawal effects.

Choice of drug used

The decision to use a drug may be influenced by many things, including:

Risks

The incidence and nature of risks vary with the drug and how it is used, the individual concerned and the circumstances. Examples of such variables include the drug substance, the presence of impurities, the dose, the frequency of use, the route of administration, the legal status of the drug, related social and financial circumstances, the personality of the individual drug user and the interaction between drug use and lifestyle.

Weighing up benefits vs risks

If the benefits from drug use are experienced before the harm, or to a greater perceived extent than the harm, positive endorsement of drug taking occurs. Following positive endorsement, drug use may, but does not necessarily, continue.

Control and dependence

A lack of specific types of neurological control is sometimes given as the reason why some people develop addictions to specific psychoactive drug(s) whereas others do not. Published studies can be criticized as the models of behaviour are largely shown in animals not humans. Nevertheless, neurological processes manifest positive and negative reinforcement of drug seeking and taking behaviours, with genetic variations influencing these.

The level of control a drug user has over his use will influence the balance between the benefits and harms experienced. With controlled use, harms can be prevented or contained, e.g. the quantity of alcohol consumed may be controlled to avoid unwanted effects. In uncontrolled use, harms can escalate. Uncontrolled use is a characteristic of drug dependence.

When a person loses control over his drug consumption, or rather drug consumption controls the person, this may be described as dependence. Drug dependence can present a significant amount of harm to the individual and to society. There is a clear association between drug dependence and social deprivation. Socially deprived areas tend to have a greater incidence of drug problems. However, drug problems are also found in non-deprived areas.

Withdrawal

When a person stops using a substance they are dependent on, they often experience withdrawal. Withdrawal can be described in two forms.

Physical withdrawal effects

These are physical signs and symptoms experienced when the drug is removed. Examples include seizures in alcohol withdrawal, stomach cramps and severe influenza-type symptoms experienced in opiate withdrawal, palpitations and anxiety in cocaine withdrawal, insomnia in nicotine withdrawal. Physical withdrawal effects can be severe and tend to be of shorter duration than psychological withdrawal effects. For example the acute physical withdrawal stage from heroin lasts usually no more than 7 days.

Psychological withdrawal effects

These are psychological disturbances experienced when a drug is removed. These cannot be so easily observed or measured in the way that many physical withdrawal effects can, but they must not be underestimated. Psychological withdrawal includes intense craving, intense emotional experiences such as unmasking of grief, inability to cope, altered mood and depression, which may be prolonged and severe. It tends to be of long duration and contributes markedly to relapse back to drug use.

The harms relating to psychoactive drug use and dependence

The risks and harms that drug use and dependence can present to the individual and society vary with the drug taken, the individual and the circumstances in which the drugs are taken. It is not possible to list all possible consequences from drug use/misuse in this chapter. The risks are categorized below.

Health problems

These affect the individual drug user and include physical and psychological health problems, which can be large and complex. As well as being caused by the individual substances concerned, health problems may relate to the method of administration. For example, injecting drug use is associated with damage to the circulatory system. Blood-borne virus infection (e.g. with HIV, hepatitis B and hepatitis C) is associated with the sharing of injecting equipment. Pharmacists are largely involved in preventing or reducing the harm from drug dependence. Hence the role of the pharmacist in drug dependence contributes towards individual and public health and safety.

Social problems

The social problems should not be underestimated and often drive people to seek treatment. Social problems may include poverty (e.g. social deprivation, exclusion or failure in education, inability to obtain or sustain employment, spending of income on drugs), damage to family relationships, difficulties forming relationships, exclusion from society and homelessness.

Drug-related crime

Drug-related crime includes not only the criminal activities committed against the Misuse of Drugs Act (see below) for which the individual is punished, but also crime that impacts on communities and society at large. The latter may relate to the acquisition of drugs or the effects of drugs, e.g. burglary to obtain money to buy drugs, robbery, violence associated with drunkenness, drunk/drug driving. Drug-related crime is of concern to society and is one of the reasons why treatment of drug problems and drug dependence is a key public health issue (see Ch. 13). Additionally, there is evidence that treatment of drug dependence contributes towards a very marked reduction in drug-related crime. Hence, treatment benefits not only the individual in terms of improved health but also society by making communities safer.

Drug users are often at greater risk than non-drug users of being victims of crime, e.g. violence associated with debt to drug dealers, prostitution, robbery and mugging if homeless or intoxicated.

Legislation

Misuse of Drugs Act

The Misuse of Drugs Act 1971 classifies drugs into Class A, Class B and Class C. The purpose of this legislation is to define the penalties imposed for the illegal undertaking of various activities, e.g. possession, supply, import, and export. These are summarized in Table 50.2. This classification system is different from the Misuse of Drugs Regulations that largely govern dispensing and other activities of the pharmacist.

Table 50.2

Classification of some commonly misused substances according to the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971

| Class | Drugs | Maximum penalties |

| A | Cocaine including crack cocaine, diamorphine (heroin), dipipanone, ecstasy, LSD, methadone, morphine, opium, pethidine | 7 years imprisonment and/or unlimited fine for possession. Life imprisonment and/or fine for supplya |

| Bb | Most amphetaminesc, cannabisd, codeine, dihydrocodeine, methylphenidate | 5 years imprisonment and/or fine for possession. 14 years imprisonment and a fine for supply |

| C | Benzodiazepines, anabolic steroids and growth hormones | 2 years imprisonment and/or fine for possession. 14 years imprisonment and/or fine for supply |

aThe term ‘supply’ includes drug trafficking and unauthorized production.

bIf Class B drugs are prepared for injection they become Class A.

cUnless prepared for injection when amphetamines become Class A.

Road Traffic Act

This 1988 Act makes it illegal to be in charge of a motor vehicle if ‘unfit to drive through drink or drugs’. This includes both illicit substances and prescribed medicines. Drivers are required by law to notify the Driving and Vehicle Licensing Agency (DVLA) if there is any reason that the safety of their driving may be impaired, e.g. the misuse of drugs, the need for medicines that impair reactions or cause sedation. The responsibility for notification lies with the patient, not healthcare professionals.

The management of drug use and dependence

Pharmacists are primarily involved with the treatment of dependence rather than interventions aimed at recreational and non-problematic drug use. The prevalence of drug dependence on a population basis is relatively small compared with national statistics that estimate numbers of people who have ever tried drugs. However, the extent of harm from drug dependence can be large; hence the need for effective strategies to support people in changing their drug use. Since the 1990s, treatment, criminal justice and prevention initiatives in the UK have been guided by government drugs strategies.

Figure 50.1 illustrates the range of methods used in preventing, reducing and controlling drug use and dependence and managing the adverse consequences.

Figure 50.1 The range of professional intervention strategies used to reduce or manage drug use and dependence.

Primary prevention

Primary prevention is concerned with preventing people from starting to use drugs. Target groups include vulnerable groups such as school children, children in care and young people who have left education. Health promotion and education campaigns are used to warn about the harm that can result from drug use and dependence using. Primary prevention also includes legislation, as the illegal nature of many drugs may prevent some people from using them. It is difficult to evaluate the impact of primary prevention activities. Reliable research in this area can also be difficult to undertake. This does not mean that primary prevention activities should not be used. They are very important for informing children and young people about drugs and their effects, in a factually correct and not ‘scaremongering’ way.

Secondary prevention

Secondary prevention is aimed at people who use drugs by discouraging further use. Examples of secondary prevention are giving advice to prevent problems such as overheating and dehydration to ecstasy users, discouraging heroin smokers from progressing to injecting, and warning of the risks and guiding on the use of CNS depressant drugs (such as heroin and methadone) by stimulant users (such as ecstasy and amphetamine) when depressant drugs are used to assist with the ‘come down’ following CNS stimulation.

Drug education

Drug education is a tool used in primary and secondary prevention campaigns and formats include leaflets, booklets, films, online information and posters. People who are dependent on drugs may also benefit from drug education as they may not be fully informed on the drugs they use or may consider using, e.g. long-term risks and overdose prevention. Drug education is also a key part of harm reduction, giving people information to assist them in minimizing risks from drug taking, e.g. safer injecting information. Drug education may be provided by a range of people, e.g. teachers, youth workers, health promotion workers, medical and nursing staff and police officers and should always be appropriate for the target group. For example, advice given to dependent heroin smokers would differ from that aiming to prevent heroin use in school children. Pharmacists may be asked to provide talks and should only deliver such talks if they feel competent to do so and capable of answering questions. Advice and information from a credible source such as publications by drug charities and health promotion units and the support of the local drugs service should be sought.

Social support

Social support refers loosely to non-medical/pharmacological interventions that can be made. These may include practical advice and assistance (e.g. seeking housing, benefits advice, and provision of hostel accommodation) and use of psychological tools such as motivational interviewing. Motivational interviewing aims to assist people in examining their drug use and the impact it has on their lives and those of others to move people towards a psychological state, where they are motivated to change their behaviour and attempt to change their drug use. Pharmacists should be aware of the need for a holistic approach to care, to improve outcomes. Some pharmacists with a special interest (PwSI) who have specialized in drug misuse have developed skills in motivational interviewing and other psychological support tools.

Detoxification

Detoxification aims for the person to become abstinent from the drug on which they are dependent by the gradual removal of the drug or substitute therapy. Examples include the use of diazepam at gradually reducing doses in benzodiazepine dependence and the use of nicotine replacement therapy.

Rehabilitation

Rehabilitation may include a detoxification process followed by a period of social support and intensive psychotherapy to facilitate sustained change. Alternatively, it may comprise the social support and intensive psychotherapy phase only, with successful detoxification being a requirement for entry on the programme. Rehabilitation is usually provided within a ‘therapeutic community’ – participants live in the environment where treatment is given, often for several months. The outcomes from various drug rehabilitation programmes show improvements in drug use, physical health, psychological health and involvement in crime.

Harm reduction

Harm reduction is a generic term to describe the range of interventions used to reduce the adverse consequences of drug dependence experienced by both individual drug users and society. Strategies prioritize goals in treatment, recognizing that, whereas abstinence from drug use may be the end goal, in some cases and for some drugs, it is not always immediately achievable. Instead, the risks and harm to the individual and others are reduced, by a process of prioritization, which the individual is involved in defining. Harm reduction engages drug users with service providers, enabling for example, motivational interventions. Harm reduction is, for most, an important route to abstinence.

Examples of harm reduction interventions include the provision of sterile injecting equipment and information to drug injectors to prevent the sharing of injecting equipment (to prevent the transmission of HIV, hepatitis B and C). Minimizing the prevalence of such diseases also protects the non-injecting community.

Harm reduction also includes the provision of substitute therapies with the aim of reducing illicit drug use and reducing drug-related crime. Substitute therapy is provided, either at an adequate maintenance dose or as a detoxification agent. Pharmacists are frequently involved in the provision of harm reduction services.

Service providers

Drug and alcohol services in the UK can be broadly grouped according to their different sources of funding.

Statutory sector

The statutory sector comprises NHS and local authority services and includes prevention initiatives and services that provide harm reduction and abstinence-directed care. A large amount of NHS drug treatment is provided in GP surgeries, either by GPs alone or in partnership with GP liaison workers from specialist drugs services. This is often termed ‘shared care’. Community drug teams (CDTs) are attached to NHS trusts. CDTs may provide primary care drug treatment, either through GP liaison work or with their own clinicians running special clinics, similar to outpatient clinics. CDT services are typically provided by doctors and psychiatric nurses but some employ pharmacists to advise on or undertake prescribing and manage on-site dispensing. Statutory sector needle exchanges also exist.

NHS services also include secondary care, where treatment such as inpatient detoxification from alcohol and other drugs is provided, typically over a short time period such as 2 weeks.

Voluntary sector

Voluntary sector (‘third sector’) services are particularly prevalent in the substance misuse field. Voluntary sector services receive funding from a range of sources (e.g. NHS, criminal justice money, local authorities, grants and donations) and are usually registered charities, with paid workers and/or volunteers operating under a management committee structure. Workers may come from a range of backgrounds, e.g. nursing, social work and community work. Some projects employ current or ex-drug users. Services may include:

Information and advice including harm reduction information

Information and advice including harm reduction information

Preparation for rehabilitation or inpatient detoxification and aftercare

Preparation for rehabilitation or inpatient detoxification and aftercare

Support to and liaison with GPs

Support to and liaison with GPs

Specialist services such as women-only sessions

Specialist services such as women-only sessions

Outreach and detached street-based work

Outreach and detached street-based work

Input into multidisciplinary groups funded by the statutory service such as pregnancy clinics for drug-using women.

Input into multidisciplinary groups funded by the statutory service such as pregnancy clinics for drug-using women.

Other voluntary sector services offer spiritual and practical support, e.g. hostel accommodation and self-help groups. The voluntary sector also may represent drug users’ views in advocacy, policy and service planning.

Private sector

The private sector includes ultra-rapid detoxification units, inpatient detoxification clinics, private primary care doctors and residential rehabilitation providers, private psychotherapists and alternative therapy providers. Funding for some of these treatments may come through the statutory sector but they are most often paid for by the patients or their families. Some pharmacists work in private sector treatment facilities advising on prescribing and dispensing. Private services offer a wide range of choice to patients but access is obviously limited by ability to pay. Ultra-rapid detoxification is not recommended for safety reasons.

Pharmaceutical care

This section focuses on pharmaceutical care of drug users, specifically looking at aspects of good pharmacy practice.

The role of the pharmacist in drug dependence

Community pharmacists

Community pharmacists are ideally placed to contribute to the care of drug users. In addition to the health gains for the patient, there are several advantages for drug users, the community and pharmacists from providing care:

Extended opening hours: most pharmacies are open at least part of the weekend and some evenings, when specialist drugs services may be closed

Extended opening hours: most pharmacies are open at least part of the weekend and some evenings, when specialist drugs services may be closed

Discretion: pharmacies provide a confidential service exchange

Discretion: pharmacies provide a confidential service exchange

Job satisfaction: the pharmacist may be the only healthcare professional with whom some drug users have regular contact. Over time, improvements in health can often be seen in people receiving substitute therapies, bringing job satisfaction.

Job satisfaction: the pharmacist may be the only healthcare professional with whom some drug users have regular contact. Over time, improvements in health can often be seen in people receiving substitute therapies, bringing job satisfaction.

The two most common services provided by community pharmacists to prevent and reduce harm are needle exchange and dispensing services.

Hospital pharmacists

Hospitals should have guidelines for the admission and discharge of drug users to ensure that any ongoing prescribing is continued. There should also be policies and specialist support available to ensure treatment can be initiated if a need is identified.

Hospital pharmacists may contribute to the formulation of such guidelines. Issues to include are:

Admissions: how to ensure the safe and prompt continuation of substitute prescribing with attention paid to acute and out of hours admissions

Admissions: how to ensure the safe and prompt continuation of substitute prescribing with attention paid to acute and out of hours admissions

Discharge: how to ensure safe continuation of substitute prescribing on discharge without a break in care or doubling up of prescribing. Liaison with the patient’s nominated community pharmacist is important

Discharge: how to ensure safe continuation of substitute prescribing on discharge without a break in care or doubling up of prescribing. Liaison with the patient’s nominated community pharmacist is important

Initiation of substitute therapy. For example, if a heroin-dependent person is admitted to a ward unplanned via accident and emergency, it will be necessary to control withdrawal symptoms that onset quickly (typically within 4–6 h)

Initiation of substitute therapy. For example, if a heroin-dependent person is admitted to a ward unplanned via accident and emergency, it will be necessary to control withdrawal symptoms that onset quickly (typically within 4–6 h)

Appropriate referral to service providers: Guidance on identifying patients at particular risk and rapid referral from hospital to primary care services is recommended.

Appropriate referral to service providers: Guidance on identifying patients at particular risk and rapid referral from hospital to primary care services is recommended.

Hospital pharmacists play a key role in advising on co-prescribing for people on substitute therapies such as methadone. Many drug interactions can occur. Treatments for epilepsy and HIV/AIDS in particular must be carefully considered.

Specialist pharmacists (PwSI)

There are pharmacists who specialize in drug dependency, many of whom come under the umbrella term of ‘pharmacist with a special interest’ (PwSI). Some provide services from community pharmacies, whereas others may be based in GP surgeries or specialist drugs services. They may be prescribers, or provide support to clinical colleagues, e.g. by advising on prescribing or providing drug information. They may also oversee dispensing and liaise with (other) community pharmacists. Others undertake strategic roles such as coordinating local pharmacy needle exchange services or overseeing the pharmacy contribution to shared care.

Needle and syringe exchange

Background

Needle and syringe exchange programmes (NSPs) began in the UK in the mid-1980s in response to the threat from HIV. NSPs were started in many countries in order to enable safe injecting of drugs. Research projects found that NSPs were effective in reducing the transmission of HIV without causing an increase in injecting drug use.

In the early 1990s, hepatitis C (HCV) was identified. This blood-borne virus is highly transmissible among injectors. It has been shown to be spread through the sharing of injecting paraphernalia, including needles and syringes, but also probably other items used in the preparation of illicit injections play a role, for example mixing water, shared makeshift filters used to remove insoluble materials and contaminated swabs. It is important that NSPs are widely available in order to limit the spread of blood-borne viruses.

Practical issues in NSP provision

Needle exchange procedure

Needle exchange involves supplying clean, sterile injecting equipment in exchange for used equipment, which is returned in a sealed sharps container. Practitioners should provide advice and check injecting sites, with referral to medical services when problems such as abscesses are identified.

NSP are usually coordinated within the health locality, so local policies and procedures should exist and in order to minimize risk support and guidance should be available to pharmacists. Adequate storage facilities are essential. Used equipment returned to the pharmacy in a sharps bin should be placed in a larger bin by the client, stored in a separate area from clean equipment and away from medicines. These bins are sealed when full and collected for incineration by clinical waste disposal companies.

To maximize the public health benefits, injecting drug users need to be able to use a clean set of equipment for each injection and every set of equipment supplied should be returned for incineration. In order to try to meet this aim, adequate amounts of injecting equipment should be supplied, bearing in mind that some crack cocaine injectors may be injecting very frequently (e.g. 15 times per day or more). Capping of numbers of sets of equipment allowed is not advocated and dilutes harm reduction effectiveness. A sharps bin should be supplied with every exchange. The return of equipment should be strongly encouraged. Written advice on safe disposal accompanied by verbal emphasis is important. However, if a person requests needle exchange but has no used equipment to return, it is advocated that supply is provided, as the health risks of not supplying are great. Pharmacy staff should not open disposal bins to count the number of sets returned.

Record-keeping and audit

Records need to be kept in order to audit the pharmacy NSP. In order to encourage use, needle exchange should be provided on an anonymous basis (no names recorded). Attractions of pharmacy-based NSPs are their anonymity and low threshold access. Too many obstacles will discourage use. One of the benefits of pharmacy NSPs is their ability to attract hard-to-reach clients. In some schemes, pharmacies issue cards which give the service user an identification number or code. This can be used to record service usage but it also allows discreet service provision, as the person only needs to show the card to indicate that they require needle exchange. This can be helpful in a crowded pharmacy. The advantage of having a record for each service user is that it can quickly be seen if someone returns used equipment or not. Those who do not can be targeted with information and firm requests to return equipment. The disadvantage is that in a busy pharmacy, this system can be too time-consuming. Additionally, some people do not want to carry a card, fearing that it identifies them as an injector. As a basic requirement, the daily number of sets of injecting equipment supplied and the approximate number returned should be recorded and data compiled for weekly or monthly audit purposes. Data should be returned to the scheme coordinator where one exists. Pharmacies with poor return rates should seek the advice of specialist drugs agencies and the scheme coordinator on strategies to increase return rates and be proactive in encouraging returns.

Risk management

A written procedure for needle exchange should be in place and followed. Body fluid spillage kits should be kept in all pharmacies as a matter of routine, irrespective of whether the pharmacy is part of an NSP, and staff should be trained in their use. In the event of an incident (e.g. a patient bleeds or vomits on the floor), the kit should be used.

Chain mail gloves should be kept in needle exchange pharmacies for use in the event of loose used injecting equipment within the pharmacy requiring disposal. If any event occurs they should be documented as part of the pharmacy’s critical incident scheme. Procedures should then be reviewed to see if anything could be done to avoid such an incident in the future (see Ch. 11).

Links with specialist services

Pharmacy NSP providers should have links with local drugs agencies and know what services are provided. Knowledge of other local services means that the pharmacist can advise when a need is identified or an opportunity arises. Often younger, newer injectors and women use pharmacy NSP because of the low threshold and discretion. The pharmacist may be the only healthcare professional these service users have contact with and should consider themselves a gateway to specialist services. Some specialist agencies may be able to supply pharmacists with targeted written information for drug injectors, such as safer injecting leaflets, and with free condoms to reduce sexually transmitted diseases. Safer injecting leaflets should not be available for self-selection but should be targeted at injectors.

Use of pharmacotherapies in drug dependence

The term pharmacotherapy in this context refers to any drug treatment used to assist in the management of drug dependence or symptoms of withdrawal. Substitute therapy refers to drug treatment that replaces an illegal drug with a legal one of the same or similar pharmacological class. For example methadone is a substitute for opiates such as heroin. Non-substitute drugs may also be used to control withdrawal symptoms (e.g. lofexidine to manage opiate withdrawal) and to manage symptoms secondary to withdrawal (e.g. loperamide to manage diarrhoea associated with opiate withdrawal).

Role of pharmacotherapy

Pharmacotherapy can be mistaken both by patients and by professionals as an all-encompassing solution. Alone it cannot stop someone using drugs but it can facilitate change in motivated people by providing what many describe as ‘breathing space’. For example substitute therapy can prevent withdrawal symptoms thus giving the person a chance to sever links with illicit drug suppliers. Substitute therapy also removes the need to commit crime to obtain money for drugs. Pharmacotherapy therefore has benefits for both the individual and society.

Evidence shows maintenance doses of substitute drug treatment alone improve patient physical health and mental health outcomes, reduce drug-related deaths and improve social functioning. However, outcomes can be enhanced with appropriate ‘wrap around’ services providing support and counselling, where the person freely is willing to take part.

The psychoactive and non-psychoactive effects of substitute therapies are not usually the same as the illicit drugs they replace and an awareness of this in the patient at the start of treatment is important. For example, orally taken methadone does not produce euphoria and it can cause lethargy and a feeling of ‘heaviness’ not associated with heroin use.

All who receive pharmacotherapy, especially in the early stages of treatment, may not achieve complete abstinence from illicit drug use. Ideally, maintenance therapy at an adequate dose may be necessary, prior to planned detoxification and aftercare. This maintenance stage may last for many years.

Methadone

Methadone is used as a substitute drug in opiate dependence. Its long half-life (24–48 h) makes it suitable for once-daily dosing in the majority of cases, although a few patients prefer to divide the dose. Providing it is given in adequate doses and for a satisfactory length of time, there is substantial evidence to suggest that methadone treatment has several benefits:

The benefits extend beyond the individual patient into the community. Less injecting reduces the risks of blood-borne virus transmission.

Failure to reduce or prevent illicit drug consumption is associated with maintenance doses of methadone less than 60 mg/day and premature pressure to abstain from methadone (Ward et al. 1999). Withdrawal of treatment should begin only when the patient is willing to attempt this, as motivation is the key to success. In detoxification, the speed of dose reduction largely depends on how well the patient is coping. Reductions should be calculated as a percentage of the dose; hence towards the smaller end of the scale, dosing will be reduced by smaller quantities. For some people, the small doses can be the hardest to reduce.

It is important to discuss with patients potential overdose risks from combining CNS depressants, including alcohol. Healthcare teams need to understand that some illicit drug use may continue, especially at the early stages of treatment. Several information leaflets are available, which explain this to patients, e.g. the ‘Methadone Briefing’ from Exchange Supplies (see: http://www.druglibrary.eu/library/books/methadone/intro.html) or the Department of Health-supported Exchange Supplies Going Over DVD.

Pharmacists should have a good understanding of the clinical aspects relating to methadone treatment before they begin providing methadone dispensing services. This should be gained as part of a CPD plan if needed.

Other treatments

Buprenorphine is a partial agonist, used as an opiate substitution therapy instead of methadone. Its use has become more widespread. The patient needs clear advice on initiation and counselling on the risks of attempting to overcome the antagonist properties, for example by using large amounts of opiate. This may present an overdose risk. Buprenorphine is used in sublingual tablet form and has a long half-life, which facilitates daily or even every second day administration. The patient must not take the first dose of buprenorphine until they are experiencing opiate withdrawal symptoms to avoid precipitated withdrawal. More information will be given in the manufacturer’s data sheet.

Lofexidine and naltrexone are also used in the management of opiate withdrawal. The former reduces some of the physical withdrawal effects from opiates by acting on the noradrenergic system, while the latter is an opiate antagonist used in relapse prevention. There are also recognized regimens to assist withdrawal for those with stimulant, benzodiazepine and alcohol dependence. When a person is dependent on more than one drug, withdrawal should be done one drug at a time.

Urine screening and responding to symptoms

People receiving treatment for drug dependence may have their urine screened. This is done to check for evidence of compliance with prescribed regimens or to confirm the consumption of illicit drugs. Pharmacists should undertake training in this area of toxicology, as some over the counter and prescribed medicines can interfere with urine screens, giving false results.

Pharmaceutical dispensing services

Shared care

Shared care with regard to substance misuse is a partnership between the GP, pharmacist, key worker and patient, to manage dependence within a formalized, structured scheme. Pharmacists participating in such schemes receive additional remuneration. Examples of schemes in the UK include those in Glasgow and Berkshire. Daily dispensing of controlled drugs is often advocated by prescribers. This means that the pharmacist is likely to be the healthcare professional with the most frequent contact with the patient. Pharmacists can play an important role in monitoring the patient’s health.

One of the benefits of shared care is that the workload of providing care is distributed locally. This prevents one or two pharmacies becoming overburdened and allows patients access to care within their communities. Participation of all or the majority of community pharmacies in the area is therefore vital for the scheme to succeed.

Before joining a shared-care scheme, pharmacists should consider any changes within the pharmacy that may be necessary. For example is there enough space in the controlled drug cabinet to store dispensed controlled drugs waiting for collection? Consider the layout of the premises. What can be done to ensure an appropriate area is available to allow a respectful service to be provided? Is there a private area for supervised consumption?

Supervised consumption

Many shared-care schemes require daily dispensing and supervision of consumption of all or most doses of substitute therapy, at least for the first 3–6 months of treatment. Supervised consumption was introduced because of leakage of methadone and other drugs to the illicit market contributing to overdoses in people who had not been prescribed the drugs.

Supervised consumption is a contentious area (see Ch. 48). Some patients view it as a useful part of treatment, whereas others dislike it. Supervised consumption can cause the patient much embarrassment.

To assist with organization, it is suggested that pharmacists prepare all daily dispensed prescriptions the day before or at the start of the week. Doses should be packaged appropriately in individually labelled containers and stored in the controlled drug cupboard, or as legislation dictates, with the prescription attached. When the patient presents for supervised consumption, the pharmacist should recheck the dispensed item. The patient should then be given the substance to be consumed together with a drink of water. The water helps take the taste of the medicine away, rinses the mouth (methadone is acidic, which could damage tooth enamel) and helps ensure the dose has been swallowed. Disposable cups should be used. The pharmacist should take the opportunity for discussion with the patient to assess their well-being and offer any advice as the opportunity arises. Over time, a good rapport and therapeutic relationship can develop with patients.

Confidentiality

Communication between healthcare professionals is key in shared care. However, patient confidentiality must be borne in mind. Information should only be shared on a need-to-know basis and with consent. Such consent is usually obtained at the start of treatment as part of a shared care agreement. The patient should be involved in negotiations about care and treatment changes. Patient’s wishes should only be breached when a severe risk to health or well-being is considered to exist if confidentiality is not broken. All matters relating to the upholding or breaching of confidentiality should be documented.

Contracts

Some shared-care schemes advocate the use of contracts, which clearly state what is expected of the patient and what the patient can expect from the service. Often they dictate standards of behaviour and include clauses requiring the patient to fulfill certain criteria, including restricting the times when patients can collect prescriptions. It is debated whether contracts should be used specifically for patients with drug problems. They imply that it is expected that the person will not behave appropriately and as such stereotypes patients. Contracts are not routinely used within pharmacy health care for other patients and it can be argued that using one for drug users is unfair and discriminatory. Pharmacies should have practice leaflets as a matter of routine which are available to all pharmacy users. These may include a statement that all pharmacy customers have a right to privacy and respect and all pharmacy staff have a right to be treated with courtesy. If individuals present any problems, the pharmacist should deal with these individually. This applies to any customers who cause difficulty within the pharmacy. Pharmacies should have a complaints procedure which can be useful for reviewing response to such incidents.

Restricted collection hours for drug users should also be considered with caution. Pharmacists are required to dispense prescriptions with ‘reasonable promptness’. Refusing to dispense a prescription during opening hours because a person has not arrived within a designated collection time may be considered discriminatory and is certainly unfair.

Locums

All standard operating procedures for pharmacy services should be documented and available for locums (see Ch. 11). This includes needle exchange and supervised consumption.

Key Points

Pharmacists can make an important contribution to the care and support of people with drug misuse problems

Pharmacists can make an important contribution to the care and support of people with drug misuse problems

Treatment of substance misuse benefits not only the patient but the community as well by reducing blood-borne virus transmission and drug-related crime

Treatment of substance misuse benefits not only the patient but the community as well by reducing blood-borne virus transmission and drug-related crime

Pharmacists should seek adequate continuous professional development to increase their competence in providing services to drug users. This should include clinical and therapeutic knowledge of treatment in this area as well as service provision skills

Pharmacists should seek adequate continuous professional development to increase their competence in providing services to drug users. This should include clinical and therapeutic knowledge of treatment in this area as well as service provision skills

Pharmacists should seek to be informed on local specialist services for drug users and have good professional links with such treatment providers

Pharmacists should seek to be informed on local specialist services for drug users and have good professional links with such treatment providers

Pharmacists should treat all pharmacy users with respect. This includes not discriminating on the basis of a person’s disease state or drug dependence

Pharmacists should treat all pharmacy users with respect. This includes not discriminating on the basis of a person’s disease state or drug dependence

Local pharmacy scheme coordinators can be of great benefit in supporting pharmacists who provide services to drug users

Local pharmacy scheme coordinators can be of great benefit in supporting pharmacists who provide services to drug users