Monitoring the patient

Introduction

Monitoring the patient may conjure up visions of healthcare professionals, including pharmacists, taking samples of blood from the patient, recording measurements or merely observing them in order to manage a medical condition. While these are important examples of how monitoring may be achieved, there are other schemes that are used specifically in relation to monitoring patients and their medication.

Pharmacovigilance is the science and activities relating to the detection, assessment, understanding and prevention of adverse effects or any other drug-related problem. This has become increasingly important in evaluating medicines and providing checks, controls and warnings to healthcare professionals and patients.

The yellow card scheme

The Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) is the government agency which is responsible for assessing the safety, quality and efficacy of a wide range of materials from medicines and medical devices to blood and therapeutic products that are derived from tissue engineering. The MHRA authorizes and regulates their sale or supply for human use in the UK (see Ch. 4).

Medicines are controlled as soon as they are first discovered and undergo clinical trials, but it is recognized that only the most common or predictable adverse drug reactions (ADRs) will be detected by the time the drug is marketed and some adverse reactions may not be seen until a very large number of people have received the medicine.

As part of its activities, the MHRA operates post-marketing surveillance and other systems for reporting, investigating and monitoring adverse reactions to medicines and adverse incidents involving medical devices. Included in this remit, the MHRA and the Commission on Human Medicines (CHM) run the UK’s national reporting system for ADRs – called the Yellow Card Scheme (YCS).

The YCS was introduced in 1964 initially to provide doctors or dentists with a route to report a suspicion that a medicine could have harmed a patient. The YCS gets its name from the colour of the original document used for reporting the ADR. These ‘cards’ have become increasingly more accessible and can be sourced by a variety of methods (Box 51.1). There is also a Yellow card freephone line. The fundamental principles of the scheme have not changed. Proof of a causal link between a medicine or a combination of medicines does not need to be established, so the reports are suspected ADRs. In the UK, the MHRA collates data on ADRs via the YCS from a wide range of healthcare professionals working in the NHS or from private healthcare providers. These now include doctors, dentists, pharmacists (from 1997), nurses, midwives and health visitors (from 2002) and also HM Coroners. Reports are received directly from them and via pharmaceutical companies. The scheme is voluntary for healthcare professionals (HCPs) but pharmaceutical companies holding marketing authorizations have a statutory obligation to report ADRs to the MHRA.

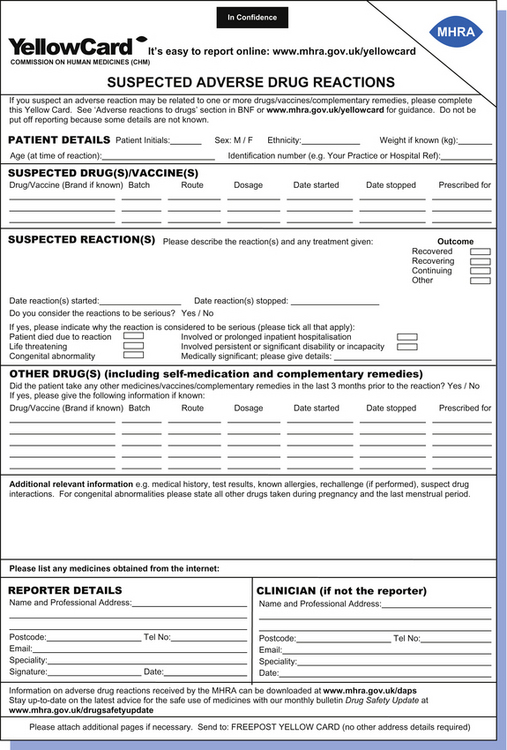

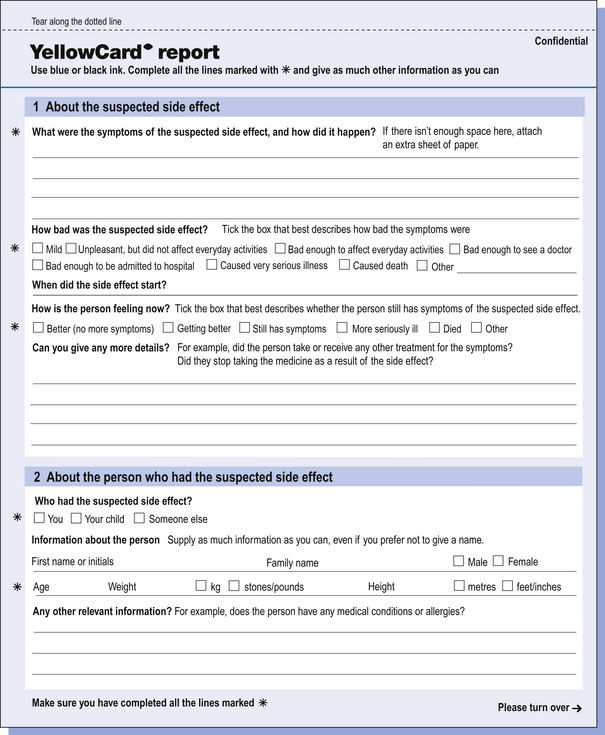

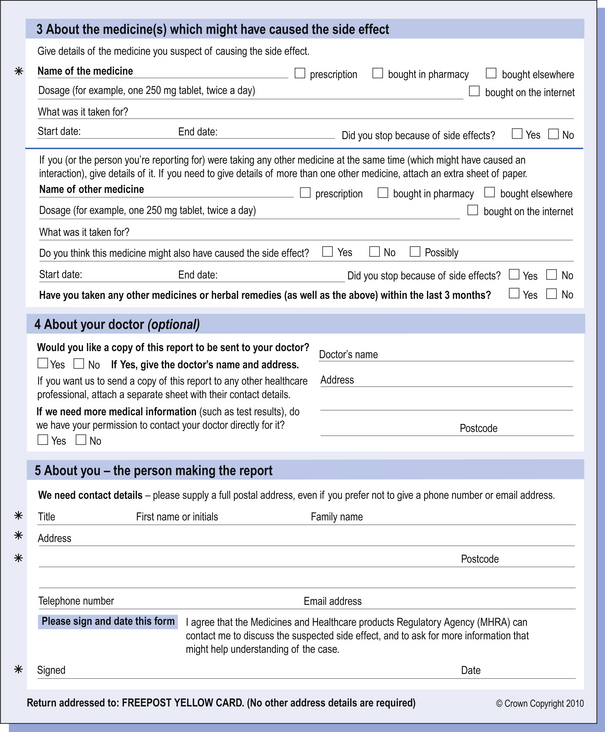

Following pilot schemes in 2005–2006, direct reports from patients, parents and carers are now accepted. The Yellow Card report forms for patients are different from those for healthcare professionals. Standard report forms are shown in Figures 51.1 and 51.2.

Figure 51.1 Standard Yellow Card report form for reporting suspected adverse drug reactions by healthcare professionals. (Crown Copyright 2012).

Figure 51.2 Standard Yellow Card report form for reporting suspected adverse drug reactions by patients, parents and carers. (Crown Copyright 2010).

There have been over 600 000 reports received since the YCS was set up. Yellow Card reports are collected on all types of medicines irrespective of legal status. These include:

However, additional criteria have also been applied when products have been selected for intensive monitoring, and include:

A different formulation for an existing route

A different formulation for an existing route

A new combination of active substances

A new combination of active substances

Administration by a new route which is significantly different from existing routes

Administration by a new route which is significantly different from existing routes

HCPs are asked to report all suspected ADRs for these products as opposed to focussing only on serious reactions for established products.

It has been suggested that the capacity of the scheme to identify ADRs should be strengthened by including other categories such as:

The Commission and the MHRA monitored intensively products carrying a black triangle symbol (▼) in the BNF. This symbol identified newly licensed medicines where the drug was a new active substance.

A product retained black triangle status until the safety of the drug or product was well established, which was usually following 2 years of post-marketing experience. There were generally 250–300 drugs under intensive surveillance (Black Triangle List). In July 2012, new pharmacovigilance legislation came into effect across the EU and a European Additional Monitoring list was published in April 2013. A medicine can be included on the list when it is approved for the first time or at any time during its lifecycle and will remain under additional monitoring usually for five years. The list will be reviewed every month.

The Black Triangle will now be used by all EU Member States and from the autumn of 2013 medicines under additional monitoring will have an inverted Black Triangle displayed in their patient information leaflet and in the information for healthcare professionals, called the summary of product characteristics, together with a short sentence:

There are a number of problems associated with the YCS but the major one has been, and continues to be, under-reporting. An internet electronic Yellow Card is available (http://www.mhra.gov.uk) to enable all reporters to submit ADR reports via the MHRA website in a paperless way.

The online reporting forms have been designed to improve clarity and usability by incorporating ‘drop-down’ menus and dictionaries for technical terms. They allow a reporter to save a partially completed report at any point so that it can be finished and submitted at a convenient time or later when more information had been received concerning the ADR. This method is being strongly promoted to encourage spontaneous reporting. The MHRA and CHM also have five Yellow Card centres whose role focusses on increasing awareness of ADRs and the YCS and follow-up of reports in their areas as this has been shown to improve the number and quality of reports. In the period 1 November 2001 to 31 December 2006, reporting of ADRs initially increased by approximately 5% each year compared with the same period in the previous year, but numbers have remained static, at approximately 25 000 reports per year since then.

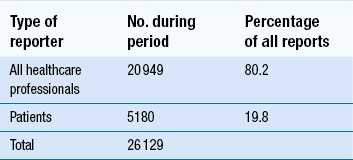

In a 2-year study period between 1 October 2005 and 30 September 2007, the YCS received 26 129 reports from all patients and HCPs. Table 51.1 provides details on the specialty of the reporters for reports received during this period. Patient reporting has been supported by the distribution of improved Yellow Cards to all GP surgeries, community pharmacies and other NHS outlets across the UK and the freephone line. The patient electronic Yellow Card has been updated and can also be accessed through the website. The study showed that patients had adopted paper, internet and telephone methods of reporting, whereas HCPs appeared to prefer to submit paper reports. However, this may have changed in the interim.

Since the scheme was opened to them, there has been a steady increase in the number of ADR reports received from patients. The patient report form uses a different format and less technical terms than those used by HCPs. In 2011, an evaluation of the pharmacovigilance impact of patient reporting of ADRs to the UK YCS noted that patient reports add value to the scheme because they report different types of drugs and reactions to reports from HCPs. They tend to provide more detail on the impact of the ADR on daily life and activities and the reports are of an equivalent level of seriousness to those of HCPs in generating new potential signals. Information collected through the YCS is an important means of monitoring drug safety in clinical practice and many important early warnings of new ADRs have been identified in addition to increasing the knowledge of known ADRs.

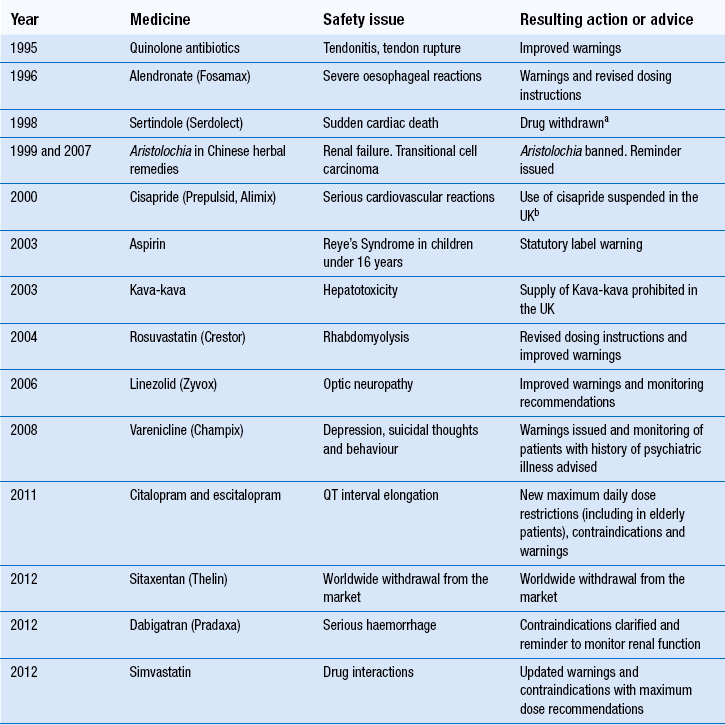

All data are closely scrutinized by the MHRA/CHM to determine whether a potential health threat is emerging and further investigation is required or more immediate action needs to be taken. In some cases, marketing authorization for the drug is withdrawn by the regulatory authority when the risks are considered to outweigh the benefits or the company may voluntarily suspend or withdraw the product. In several instances, a drug has continued to be available following amendments to the summary of product characteristics (SPC) and patient information leaflet (PIL) indicating restrictions in use, reduction in dosages and special warnings and precautions. Some examples can be seen in Table 51.2. Complete listings of the suspected ADRs reported to the MHRA through the YCS by HCPs and patients are provided in drug analysis prints (DAPs). Drug analysis prints can be accessed from the MHRA website.

Table 51.2

Safety issues which Yellow Card reports have helped to identify

aSertindole was reinstated in 2002 with increased warnings.

bCisapride licences have been cancelled.

It is recognized that there are a number of problems with spontaneous reporting systems such as this. Under-reporting arises because HCPs or patients do not recognize an ADR if it is unknown or difficult to spot. Conversely, there may be a bias to report ADRs that are well publicized. The true incidence of a particular ADR cannot be determined, since there is a lack of information on the total number of patients exposed to the drug. The quality of the data reported is variable and some important details may be omitted and the report only indicates that an ADR is suspected, which does not imply causality, and false positives are mixed with true effects. The YCS is also poor at detecting long delayed reactions.

In addition, reporting systems in different countries differ and it was difficult to compare reports of ADRs across international boundaries. However, the WHO set up its Collaborating Centre for International Drug Monitoring after the thalidomide disaster. Since 1978, the programme has been carried out by the Uppsala Monitoring Centre (UMC) in Sweden, which is able to apply techniques to identify signals of ADRs that require further investigations using reports from over 100 member nations.

Patient or consumer reporting schemes are known to be operating in 46 countries.

The role of the pharmacist

Pharmacists have an important contribution to make in the prevention, identification, documentation and reporting of ADRs and in strengthening Yellow Card reporting. Currently, the proportion of Yellow Cards received from pharmacists remains around 13%, whereas the proportion of patient reports submitted over a similar time period is almost 20%.

The new medicine service (NMS) was launched in October 2011 and commissioned until December 2013. In the first 9 months, the NMS had a marked effect on reporting by community pharmacists with a significant increase of 120% compared with the same period in the previous year.

It is important that pharmacists are not reluctant to report suspected ADRs because they are often the HCP most able to identify ADRs and to play an active role in their prevention.

On a daily basis, the pharmacist becomes aware of factors that could indicate an ADR is occurring such as:

Excessive therapeutic effects of medicines

Excessive therapeutic effects of medicines

Medications prescribed or purchased to treat ‘side-effects’

Medications prescribed or purchased to treat ‘side-effects’

Drugs being discontinued but alternatives with the same indication being prescribed or purchased.

Drugs being discontinued but alternatives with the same indication being prescribed or purchased.

Their role as prescribers means they are more closely involved with the patient and the choice of medication. The expanding range of over-the-counter (OTC) medicines and the increasing number of medicines whose legal status has changed means that the responsibility of providing guidance to patients on the safe use of medicines frequently falls to the pharmacist (see Ch. 21). This also means that they should be advising patients to contribute to the YCS by completing forms themselves or encouraging patients to do so.

The future

For the future, it is hoped that the information collected by the YCS can be used by researchers to help studies that will advance knowledge in the safe use of medicines. Examples of research applications that have been accepted, include acute renal toxicity reported to the YCS and pharmacogenetics of antimicrobial drug-induced liver injury.

International collaboration is also important to improve patient safety and public health. In conjunction with the launch of the new EU pharmacovigilance legislation, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) is responsible for a centralized system for reporting suspected adverse drug reaction cases to common medicines and active substances used in nationally-authorized medicines in the EU. The system will publish regular reports and in doing so, provide better prevention, detection and assessment of ADRs throughout the EU. Similarly, pharmacovigilance methods are being applied to public health programmes to supplement existing knowledge on adverse effects of newly introduced medicines for conditions such as malaria, tuberculosis and HIV.

The medicines use review (MUR)/prescription intervention service

Background

The community pharmacy contractual framework (CPCF) for England and Wales was introduced in April 2005. The CPCF comprises ‘Essential’, ‘Advanced’ and ‘Enhanced’ service tiers. The medicines use review (MUR)/prescription intervention service is included under ‘Advanced’ services.

Although there are two service titles, in reality there is only one service, and the same premises and pharmacist accreditation requirement apply to both but the trigger which initiates provision is different. The MUR is a national service in which accredited pharmacists are remunerated to discuss the patient’s medication both prescribed and non-prescribed and support them in getting the most from their medicines.

The pharmacist reviews the patient’s use, experience and taking of medicines together with identifying side-effects and interactions. The regular MUR is a routine consultation not triggered by a problem with the patient’s adherence to their regimen. Prescription interventions involve the same review, but are triggered by a significant issue, such as an adherence problem, that comes to light during the dispensing of a prescription. The pharmacist aims to resolve any issues around poor or ineffective drug use by the patient and in this way, uses a different approach to patient monitoring and patient safety. Following the first year of implementation, the national evaluation of the CPCF in 2007 indicated that 60% of pharmacies were providing the MUR service. The MUR was seen as the first opportunity for the pharmacist to demonstrate the added value that their input could make to patient care. Since then, the directions applying to MURs have been amended to incorporate a revised reporting form and GP (or equivalent) notification requirements. Uptake of the service has steadily increased and statistics now show that around 9000 pharmacies claim MUR payments, with an average of 20–25 MURs carried out per claiming pharmacy, each month.

Accreditation

A pharmacy can only provide advanced services if it is satisfactorily providing all the essential services in the CPCF. In order to provide MUR services, certain criteria must be met by both the pharmacy from which the service is taking place and the pharmacist who is providing the service.

Pharmacy criteria

As well as providing essential services, a pharmacy must have a consultation area:

Where the patient and pharmacist can sit down together

Where the patient and pharmacist can sit down together

Where the patient and pharmacist can talk together without being overheard by other visitors to the pharmacy or staff undertaking normal duties

Where the patient and pharmacist can talk together without being overheard by other visitors to the pharmacy or staff undertaking normal duties

Which is clearly designated for confidential consultations, distinct from the general public areas of the pharmacy.

Which is clearly designated for confidential consultations, distinct from the general public areas of the pharmacy.

If there is no space for a consultation room, pharmacists may conduct an MUR when the pharmacy is closed, making the whole pharmacy the consultation room. A request form has to be submitted to the Commissioning body in order to do this.

Pharmacists’ criteria

Pharmacists must successfully undertake a competency assessment to gain accreditation before providing MURs and send a copy of the certificate to the PCO before they can begin to offer the service.

Any higher education institution (HEI) can provide training and competency assessments for the MUR service. A national competency framework is used as the basis for these assessments. The framework is not designed to be an exhaustive list of competencies that might be required to undertake MUR, but consists of those key elements that can be assessed in a robust and reliable manner.

There are a number of providers who run courses and/or competency assessments. Additionally, some academic institutions that provide postgraduate clinical programmes, such as diplomas, have ensured their courses develop and test the skills of students in order to meet the requirements of the MUR competencies. A list of providers across the UK is available from the Pharmaceutical Services Negotiating Committee (PSNC) website (www.psnc.org.uk).

A pharmacist registered with a primary care organization in England has to register separately in Wales – and a pharmacist registered with a local health board in Wales has to register separately in England.

A pharmacist must also apply to the PCO for permission to conduct MURs in special circumstances, e.g. at a patient’s own home, at a residential home, at an external clinic or on the phone. A separate request has to be made for each category of patient on each occasion.

Carrying out an MUR

Although it could be considered to be a simple task to carry out an MUR once the criteria for the premises and pharmacist have been satisfied, it still requires a considerable amount of planning and preparation to achieve a satisfactory result.

Patient selection – there are specified criteria that determine which patients are suitable for selection:

An MUR can be conducted with patients on multiple medicines and those with long-term conditions

An MUR can be conducted with patients on multiple medicines and those with long-term conditions

Regular MURs, initiated by the pharmacist, must only be provided for patients who have been using the pharmacy for the dispensing of prescriptions for at least the previous 3 months

Regular MURs, initiated by the pharmacist, must only be provided for patients who have been using the pharmacy for the dispensing of prescriptions for at least the previous 3 months

The next regular MUR can be conducted 12 months after the last MUR.

The next regular MUR can be conducted 12 months after the last MUR.

In addition, national target groups were introduced in October 2011 and at least 50% of all MURs undertaken by each pharmacy in each year should be on patients in these groups. The national target groups and other patient groups suitable for MURs can be seen in Box 51.2.

It is important to note that the MUR covers all the patient’s medicines not just those that are specified for the target group. Patients on only one medicine may have an MUR if that medicine is one of those specified in the high risk group.

Patients who have been recruited to the new medicine scheme (NMS) because they have been prescribed a new medicine for the management of a long-term condition on discharge from hospital should not have an MUR.

Local criteria

Most PCOs, working with their community pharmacies, may identify priority groups who would be appropriate for MURs, based on the needs of the local health economy. Many pharmacists have or are looking to have areas of specialized interest and MURs provide them with an excellent opportunity to use this expertise in certain patient groups.

Pharmacists do not only select suitable patients themselves, they may accept referrals for MUR from the local surgery, other HCPs, e.g. district and practice nurses, key workers and social services. In this way, one of the perceived positive aspects for the CPCF, to allow the extended role of the community pharmacist to align with local health needs, may be achieved. The pharmacist can accept requests directly from patients for an MUR as long as the national criteria are met.

Prescription intervention

It should be noted that the patient selection criteria do not apply in the case of a ‘prescription intervention’, where the requirement for a MUR to be undertaken is initiated by the pharmacist identifying a significant problem during the dispensing of regular prescriptions. In particular, the requirement to have provided pharmaceutical services for a minimum of 3 months is removed. In these cases, the initiating issue which led to the need for a prescription intervention is discussed with the patient as part of the MUR.

Engaging the patient

Since the service was introduced, engaging with patients to invite them to attend for the MUR has proved to be a problem. Patients must give written consent to an MUR using nationally approved wording to permit their information to be shared with the GP, PCO and the NHS Business Services Authority (NHSBSA).

Initially uptake was poor because few patients had heard of the service and awareness of its purpose was low. Surveys had indicated that patients supported the concept of pharmacists helping them to understand what their medicines were for but patients were less inclined to attend an appointment to discuss their medicines. Many did not perceive that an annual MUR was required.

Similarly, GPs and other relevant professionals had received little information about the service, availability was not, and is still not guaranteed from all pharmacies, and there were a number of other problems with the paperwork resulting in reluctance to signpost the service to patients.

Since that time, steps have been taken locally and nationally to develop and provide support for those offering the MUR service. These resources can be accessed from the PSNC website. In July 2012, the new NHS MUR requirements were started, with specific changes made to the structure of the MUR process. Pharmacists have realized that they have to proactively engage patients to emphasize the benefits of the service and arrange appointments. To incorporate MURs into the daily work of the pharmacy without additional pharmacist cover is difficult. Experience has now shown that the most successful MUR schemes use skill mix with pharmacy staff assisting with planning and preparatory work for the MUR. Pharmacy staff require an understanding of what MURs are all about, but once this has been established, they can work together to:

Alert the pharmacist when a potential MUR candidate has presented a prescription or is about to receive the dispensed items

Alert the pharmacist when a potential MUR candidate has presented a prescription or is about to receive the dispensed items

Organize the appointment system when the MUR pharmacist is available

Organize the appointment system when the MUR pharmacist is available

Bringing in an extra pharmacist on 1 or 2 days per week is another option.

The patient interview

Despite pharmacists having extensive experience in communicating with patients, many have found the MUR interview difficult. Eliciting the information required to capture all that is required for the national dataset can be time-consuming and is important, as this must be kept for every MUR completed for 2 years.

With experience, pharmacists have realized that the key areas they need to address are to:

look through the patient medication record (PMR) beforehand

look through the patient medication record (PMR) beforehand

note any listed medical conditions

note any listed medical conditions

prepare a structured format for the session including suitable questions

prepare a structured format for the session including suitable questions

This is in addition to all the general issues of putting the patient at ease, revising the purpose of the interview, active listening and appropriate responses to any comments or questions from the patient.

Completing the MUR

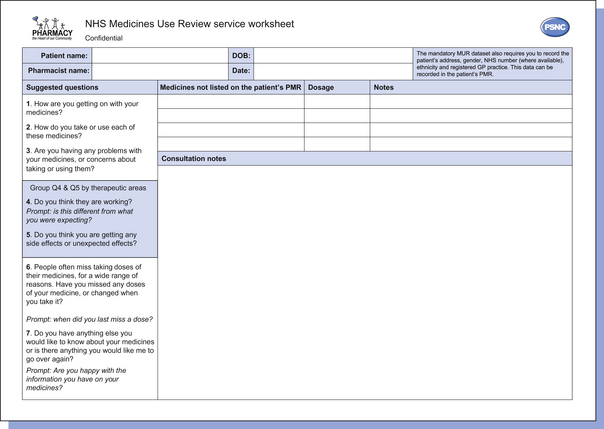

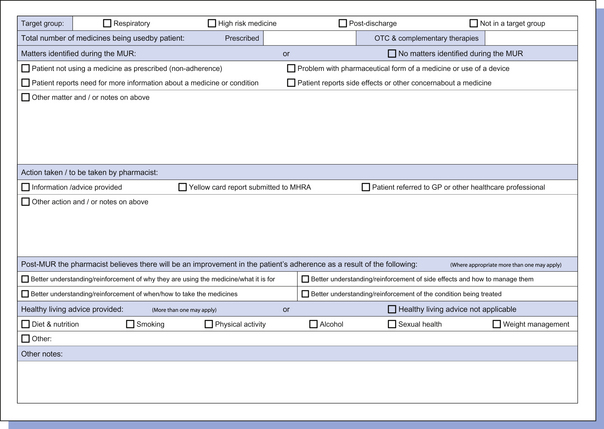

Since July 2012, there is no longer a requirement to use the previous MUR form. A PSNC MUR worksheet is available (see Fig. 51.3) but the pharmacist can adopt any method for creating a record as long as it includes the nationally agreed MUR dataset and ensures that ongoing care is provided.

The patient no longer needs to be provided with a copy of the full MUR form, but pharmacists may provide them with a summary of the key points discussed during the MUR. If there are no items to consider, the pharmacist needs only to store the data and include it in a quarterly activity report to the PCO.

These changes have made the system more efficient and acceptable to all those involved.

Interactions with GPs

The MUR was the first community pharmacy service where a formal communication between the pharmacist and the GP was required to notify a GP practice that an MUR had been carried out on a patient. However, it has been agreed that this information was not useful and consequently an approved MUR Feedback Form (accessed from the PSNC website) is now provided to the patient’s GP practice, only where there is an issue for them to consider. The pharmacist may also feel it is necessary to discuss urgent issues with the GP directly.

The future

The potential outcomes from MURs and the NMS include improved attainment of health goals and quality of life through better use of medicines, reduced wastage and more effective use of resources. It is possible that patients will make fewer visits to the surgery and have reduced unplanned hospital admissions. To some extent, these outcomes have been accepted, although a major flaw has been the lack of measurements and monitoring of the quality of the service. The introduction of targeted MURs has provided evidence that they can provide better control and improve symptom management of respiratory conditions.

MURs are one of the biggest innovations in community pharmacy in the last few years. They require community pharmacists to undertake functions complementing the work of GPs and other healthcare workers and align them to local health priorities. Pharmacy has to continue to demonstrate that services such as the MUR and NMS are valuable in delivering medicines’ optimization. Improvement in patient knowledge ensures better medicines safety, a more rational approach to the use of medication and better monitoring.

MUR statistics collated for England are available to view on the PSNC website (www.psnc.org.uk).

Key Points

The MHRA is responsible for assessing safety, quality and efficacy of medicines and medical devices in the UK

The MHRA is responsible for assessing safety, quality and efficacy of medicines and medical devices in the UK

Post-marketing surveillance aims to detect ADRs which did not show during pre-marketing testing

Post-marketing surveillance aims to detect ADRs which did not show during pre-marketing testing

The YCS was introduced for doctors and dentists in 1964 to report suspected ADRs

The YCS was introduced for doctors and dentists in 1964 to report suspected ADRs

The YCS has been extended to other HCPs, including pharmacists and patients

The YCS has been extended to other HCPs, including pharmacists and patients

New pharmacovigilance legislation was introduced across the EU and a European Additional Monitoring list to identify drugs for intensive monitoring replacing the Black Triangle list

New pharmacovigilance legislation was introduced across the EU and a European Additional Monitoring list to identify drugs for intensive monitoring replacing the Black Triangle list

When an ADR is identified, the drug may be voluntarily or compulsorily withdrawn or it may continue in use with amended SPC or PIL

When an ADR is identified, the drug may be voluntarily or compulsorily withdrawn or it may continue in use with amended SPC or PIL

Under-reporting appears to be a problem with ADRs

Under-reporting appears to be a problem with ADRs

MUR is an advanced service in the pharmacy contract in England and Wales, but was slow to become established

MUR is an advanced service in the pharmacy contract in England and Wales, but was slow to become established

For accreditation to carry out MUR, the pharmacy and pharmacist must meet set criteria, the pharmacist applying to the PCO for permission

For accreditation to carry out MUR, the pharmacy and pharmacist must meet set criteria, the pharmacist applying to the PCO for permission

There are national target groups for selection of patients for MUR

There are national target groups for selection of patients for MUR

Apart from comprehensive preparation, the pharmacist needs to employ effective communication skills

Apart from comprehensive preparation, the pharmacist needs to employ effective communication skills

The MUR feedback form is to be sent to the GP practice only when there is an issue to consider

The MUR feedback form is to be sent to the GP practice only when there is an issue to consider