Control of medicines

Most countries place legal controls on their medicines

Most countries place legal controls on their medicines

All stages in the development, manufacture and distribution of medicines are controlled

All stages in the development, manufacture and distribution of medicines are controlled

Medicines are classified to control their access to the general public

Medicines are classified to control their access to the general public

Introduction

Modern medicines have transformed the world, but the drugs within them are powerful chemicals which have potentially harmful adverse effects. Medicines and drugs can be misused (see Ch. 50), abused and when taken as an overdose, which may be intentional, can sometimes be fatal. Self-treatment of the wrong drug for the wrong condition or disease can have severe consequences. For these reasons, most governments or states control all aspects of medicines from their first trials in animals, through manufacture and distribution to post marketing pharmacovigilance: together with who can supply and/or prescribe the medicine. This chapter explains this process in more detail and describes the controls placed on large organizations, such as the pharmaceutical industry, as well as the legal controls placed on the medicines and the professionals acting as suppliers/prescribers.

Control of medicines

Most countries have legislation in place to regulate and control medicines: in the UK, this is the Human Medicines Regulations 2012. The legislation will be administered through the legal system and government departments. Examples of these departments include the Department of Health (DH), which is headed by the Minister for Health in the UK, the Department of Health and Ageing in Australia and the Department of Health and Human Services in the USA. These Departments create agencies, which are responsible for the day-to-day regulation and control of medicines. The Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Authority (MHRA) in the UK is responsible for ensuring that medicines and medical devices work, and are acceptably safe. In Australia, the Therapeutic Goods Administration regulates medicines. In the USA, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) aims to protect consumers and enhance public health by maximizing compliance of FDA-regulated products. These regulated products include medicines and medical devices. The FDA also deals with veterinary products, as well as human medicines. Veterinary medicines are regulated by the Veterinary Medicines Directorate in the UK (see Ch. 28).

In addition to the MHRA in the UK, advisory bodies have been set up including the Commission on Human Medicines, the Herbal Medicine Advisory Committee and the Advisory Board on Registration of Homeopathic Products. These advisory bodies have expert panels which advise the Minister of Health on matters relating to their specialist products.

The MHRA is organized into divisions including: licensing, medical devices, vigilance risk management of medicines and inspection, enforcement and standards. These divisions ensure that medicines are regulated and their safety and efficacy are monitored, at both pre- and post-marketing stages.

Pre-marketing of medicines

Before medicines are marketed, the regulatory authorities in a country will place controls, usually in the form of licences or certificates, on the various development stages. In order to proceed to test a potential drug, the regulatory authority must grant licences before animal testing and human or veterinary clinical trials can be undertaken. If all these tests are successful and lead to a new medicine being developed, then the pharmaceutical company will need to obtain a Marketing Authorization (previously product licence in the UK) from the regulatory authorities. Only after obtaining this Marketing Authorization can a medicine be marketed in that country. Some medicines in the UK are licensed by the European Medicines Agency.

Any medicine imported into a country, will usually require a Marketing Authorization from the country of origin and an importation licence/certificate from the regulatory authority of the importing country.

Manufacturing and wholesaling of medicines

The manufacturing conditions employed by a pharmaceutical company in the production of medicines will be subject to controls by the regulatory authority. A system of inspection, enforcement and standards will be applied both before and after the granting of a Manufacturer’s Licence. Inspection and standards will involve premises, equipment, record-keeping and suitability of staff employed. Legally, no manufacturer can produce medicines without a Manufacturer’s Licence.

Manufacturers of medicines will normally be allowed to sell directly to the professional outlets for medicines, but usually sell though a pharmaceutical wholesaler. These wholesalers will be subject to controls by the regulatory authority, which will be similar to those applied to manufacturers. Again, inspection and application of standards will apply to premises, equipment and systems of transportation before the granting of a Wholesaler’s Licence. Enforcement of standards will apply after the licence is obtained. No wholesaler of medicines can operate legally without a Wholesaler’s Licence.

Post-marketing of medicines

The vigilance of medicines, after their marketing, with regard to their safety and efficacy will be monitored by the regulatory authority. Any medicine found to have adverse effects, which give rise to concerns over safety, can be withdrawn from the market immediately and, concomitantly, the Marketing Authorization removed (see Ch. 22).

Supply of medicines

The legal structure within a country will regulate the supply of medicines. Box 4.1 shows some of the controls on medicines.

Thus, the legislation controls healthcare professionals and their staff (see Ch. 5) and their professional premises, such as community pharmacies.

Legal classification of medicines

The legal classification used for medicines in a country will have a direct impact on how and where the general public can access their medicines.

Most countries have additional laws to restrict access to narcotic analgesics and other groups of potent medicines and drugs of abuse.

Some countries have a two-tier classification of drugs:

‘Non-prescription’ medicines, also called ‘general sales’ or ‘over-the-counter’ (OTC) medicines. These medicines are available from pharmacies and also from other retail outlets such as grocers, supermarkets, newsagents and garage forecourts.

‘Non-prescription’ medicines, also called ‘general sales’ or ‘over-the-counter’ (OTC) medicines. These medicines are available from pharmacies and also from other retail outlets such as grocers, supermarkets, newsagents and garage forecourts.

Some countries further divide non-prescription medicines into ‘pharmacy medicines’ and OTC medicines. ‘Pharmacy medicines’ are available for sale to the general public, but only from a pharmacy and under the supervision of a pharmacist. Thus, pharmacists have a direct input into the sale of these medicines. Germany, Ireland and the UK are examples of countries which have this three-tier classification.

Australia has a three-tier classification, but has further divided pharmacy medicines into those that can be sold:

The USA, Estonia and Saudi Arabia are examples of countries with a two-tier system in which pharmacists control access by the general public to prescription-only medicines.

Reclassification

In recent years, some medicines have been reclassified, usually from prescription-only to pharmacy or general sales classifications. This allows more medicines to become available, often with pharmacist input, to the general public for purchase. Such a process has given pharmacists a more professional image and increased the professional content of their work (see Ch. 21).

Prescribers

Any medicine classified as ‘prescription-only’ must have a prescriber to write the prescription before the patient can be supplied with that medicine. Traditionally, prescribers were doctors, dentists and veterinary practitioners (for animal medicines). In the last few decades, there has been a dramatic increase in the number of medicines available to treat disease and illness (see Chs 20 and 22) and this has resulted in an increase in the number of prescriptions provided by the traditional prescribers. In order to use the skills of other healthcare professionals, new methods of access to medicines have been introduced. These include non-medical prescribing, patient group directives (PGD) and minor ailment schemes (see Chs 21 and 49).

Non-medical prescribing

The review of prescribing, supply and administration of medicines chaired by June Crown in 1999 recommended that there should be two types of prescriber: the independent prescriber and the dependent prescriber, now termed the ‘supplementary prescriber’.

Over the years, there have been many reports from the DH outlining the benefits of non-medical prescribing for patients, doctors and non-medical prescribers themselves (see Box 4.2). Many of these benefits stem from having the healthcare professional responsible for the care of a patient’s condition also writing the prescription.

Independent prescribing

Independent prescribers (IP) are responsible for the diagnosis of the patient and can initiate prescriptions for patients without referring to other healthcare professionals. They have responsibility for monitoring and reviewing the patient’s progress. In the UK, the first independent non-medical prescribers were the community practitioner nurse prescribers, introduced in 1994 in pilot sites and extended nationwide in 1999. These prescribers had a limited number of medicines which they could prescribe.

In 2002, a new class of nurse prescriber was created; they were originally called extended formulary nurse prescribers. This opened prescribing to any registered nurse. Nurses that chose this route to becoming a prescriber were required to complete a training course which consisted of 26 taught days and 12 days learning in practice, which included prescribing under the supervision of a medical prescriber. In 2006, many of the previous restrictions on extended formulary nurse prescribers were removed and their name was changed to ‘independent nurse prescribers’. The independent nurse prescribers are able to prescribe any licensed medicine for any medical condition. Nurse independent prescribers must work within their own level of competence and expertise.

The changes in 2006 also paved the way for pharmacist independent prescribers, who can prescribe the same medicines and under the same conditions as nurse independent prescribers. Optometrists can also, with additional training, become optometrist independent prescribers. In this case they can prescribe any licensed medicine for ocular conditions affecting the eye and the tissues surrounding the eye, except controlled drugs or medicines for parenteral administration.

Supplementary prescribing

Supplementary prescribing is viewed by the UK DH as a voluntary partnership between the independent and the supplementary prescriber that has the agreement of the patient. Therefore, the patient must be informed regarding the underlying principles of the prescribing partnership by the independent prescriber and give their consent to the transfer of care to a supplementary prescriber. The patient does not have to give written consent, but once consent has been given, it should be noted in the patient’s medical notes.

Providing the patient agrees, there is very little restriction as to what can be prescribed. Controlled drugs and unlicensed medicines were added to the list of drugs that can be prescribed by supplementary prescribers in May 2005.

An independent prescriber, who must be a doctor or a dentist, makes the diagnosis. If the independent prescriber thinks that the patient can be safely managed by a supplementary prescriber, then both the independent prescriber and supplementary prescriber agree a clinical management plan (CMP) for the patient. However, the independent prescriber does not discard all their responsibility and must still review the patient at suitable intervals, which should rarely exceed a year.

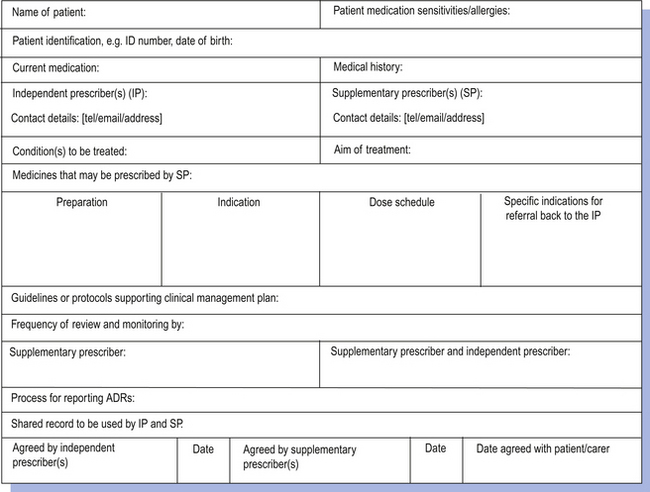

The CMP is central to supplementary prescribing in that it forms the agreement between the independent and supplementary prescribers that sets out what the supplementary prescriber is able to prescribe (Fig. 4.1). Each CMP must be drawn up for a specific named patient. The nature of the CMP can vary in terms of its detail and scope. At one end of the spectrum it could be very specific, allowing only relatively minor modifications to be made to the original prescription under specified criteria, such as increasing the dosage of an antihypertensive drug in order to reduce blood pressure to a specified level. At the other end of the spectrum it could be very open, allowing the supplementary prescriber to prescribe a wide range of drugs in accordance with a clinical guideline, such as the British Thoracic Society’s guidelines for the management of asthma. The nature of the CMP will depend upon the confidence and competence of the supplementary prescriber in each therapeutic area and also the willingness of the independent prescriber to delegate the responsibility. The plan also sets out the circumstances that would require referral back to the independent prescriber.

The patients most likely to benefit from supplementary prescribing are those with chronic conditions requiring ongoing care, such as diabetes mellitus, asthma or hypertension. In addition, those with uncomplicated conditions, rather than those patients with multiple problems, are likely to be the most suitable candidates for supplementary prescribing. In practice, the supplementary prescriber is likely to continue prescribing the items initiated by the independent prescriber until there is a change in the patient’s condition, provided such items have been included in the CMP. A change in the patient’s condition could involve a deterioration of a chronic progressive condition. An example of managing the deterioration is stepping up therapy by prescribing an additional item such as a steroid inhaler to an asthmatic patient who is poorly controlled on a salbutamol inhaler alone (see Ch. 43).

As supplementary prescribers do not diagnose conditions, one might assume that they would be unable to prescribe for patients presenting with acute conditions. However, they can prescribe items in response to changes in the patient’s condition, provided such items have been included in the CMP. A change in the patient’s condition could involve an acute exacerbation of a chronic condition. An example is prescribing an antibiotic for a chest infection for a patient with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Patient group directions

An alternative way of getting medicines to patients without writing a prescription involves the use of a PGD. These allow pharmacists, or other healthcare professionals, to supply named products to patients who meet the inclusion criteria specified in the PGD. The legal definition of a PGD is: ‘A written instruction for the sale, supply and/or administration of named medicines in an identified clinical situation. It applies to groups of patients who may not be individually identified before presenting for treatment’.

Under a PGD, pre-packed licensed medicines can be supplied to patients who meet the appropriate inclusion criteria and do not meet any of the specified exclusion criteria. The PGD must state the qualifications and training required of the staff administering the PGD, and it must name the medicine(s) that can be supplied. It must also list any advice that should be given to the patient, describe the referral procedure and state the action that should be taken in the case of a patient suffering an adverse drug reaction. The PGD must be reviewed and approved by a team containing a doctor and a pharmacist.

The DH has made it clear that the preferred route of getting medicines to patients is via the issuing of a prescription to a named patient by a trained and qualified prescriber and that PGDs should only ever be used where they offer clear advantages to patient care without compromising patient safety. Situations that could be suitable for PGDs are those that involve one-off or relatively short courses of standard treatment (i.e. the PGD operator does not have to select the drug, dose or formulation). An example of a PGD is the supply of emergency hormonal contraception through community pharmacies (see Ch. 48). PGDs have also been set up to supply medicines for weight loss, erectile dysfunction and smoking cessation.

Minor ailment scheme

Pharmacists have a long tradition of selling medicines over the counter to treat minor ailments. In some situations, pharmacists might have a choice regarding the method of supply of a medicine to treat a patient. This could be via an over the counter sale, prescribing a medicine as part of a minor ailment scheme (see Ch. 21) or supply through a PGD. In some of these situations the exact same product could be supplied and the only differences between the different methods might be who pays for the treatment and whether records have to be made. The pharmacist’s duty of care to the patient does not vary between the different methods of supply and pharmacists should not treat an over-the-counter purchase of a medicine any differently than prescribing a medicine.

When recommending products to patients for OTC purchase, the pharmacist is acting as an independent prescriber, although they can only recommend general sales medicines or pharmacy medicines. As an independent prescriber, the pharmacist must go through all the steps of the prescribing process (see Ch. 20). The patient should be involved in the decision-making process to achieve concordance (see Ch. 18), and appropriate advice given to allow the patient or their carer to monitor the progress of their treatment and to know when to seek further help or advice (see Ch. 25).

Advertising of medicines

Many countries have strict controls on the advertising of prescription-only medicines. For example, advertising to anyone other than a healthcare professional is banned in the UK. These controls are to help protect the public from the potential misuse of medicines. However, in other countries, banning advertising is considered to be a constraint on trade and so advertising of prescription-only medicines is allowed, as for example in China. Nowadays, it is very difficult for any country to completely control the advertising of prescription-only medicines because the general public can access both advertising and information about prescription-only medicines via the internet. Some of the information on these sites may contain inaccurate information (see Ch. 16).

The advertising of pharmacy medicines and general sales medicines is usually permitted. However, most countries will have, as a minimum, some guidelines to ensure that advertisements are truthful and do not make excessive claims for their products. The advertising of pharmacy medicines may result in difficult patients who are not prepared for the pharmacist to advise against, or refuse to sanction, their purchase of a particular pharmacy medicine. Thus, the laws governing the advertising of medicines in that country will influence the everyday work of community pharmacists.

Key Points

Medicines are controlled by legislation

Medicines are controlled by legislation

Access to medicines is limited by their legal classification

Access to medicines is limited by their legal classification

Non-medical prescribing has used the skills of healthcare professionals

Non-medical prescribing has used the skills of healthcare professionals

Patient group directions enable medicines to be accessed without a prescription

Patient group directions enable medicines to be accessed without a prescription

Controls on the advertising of medicines are prejudiced by the internet

Controls on the advertising of medicines are prejudiced by the internet