Sleep-Related Movements and Scoring Techniques

Movements during sleep can occur as physiological phenomena or as the manifestations of sleep pathological conditions. In fact, abnormal movements during sleep have been observed in almost all major categories of the International Classification of Sleep Disorders (ICSD-2). Examples are periodic and nonperiodic movements in insomnia, major motor activity related to arousals at the end of apnea-hypopnea episodes, abnormal motor activity during rapid eye movement (REM) and non-REM sleep in narcolepsy, abnormal sleep-related movement as a hallmark of many parasomnias, and sleep-related movement disorders encompassing restless legs syndrome, periodic limb movement disorder, rhythmical movement disorder, bruxism, and sleep-related cramps.

In addition, the category of “isolated symptoms, apparently normal variants and unresolved issues” contains many other sleep-related movements, for which the definite assignment into normal or pathological movement has not yet been made (e.g., sleep starts or hypnic jerks, hypnagogic foot tremor and alternating leg muscle activation, propriospinal myoclonus at sleep onset, and excessive fragmentary myoclonus).

This chapter focuses on scoring techniques of sleep-related movement disorders.

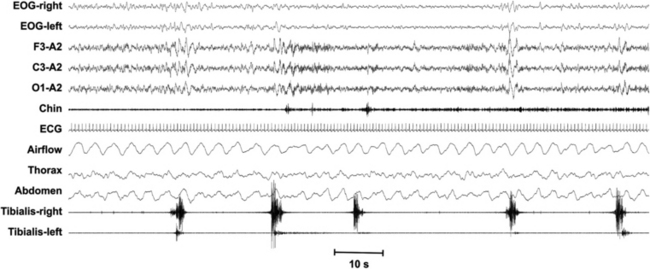

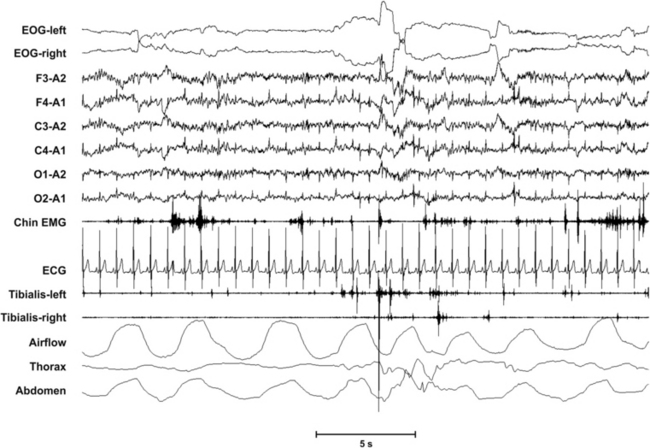

FIGURE 7.1 Periodic limb movements (PLM) are movements lasting 0.5 to 10 seconds, separated by 5 to 90 seconds (onset to onset), and occurring in a series of at least four, with a minimum amplitude of an 8-μV increase in electromyographic (EMG) voltage above resting EMG. The number of the movements presenting these features per hour defines the PLM index. It can be calculated during sleep or during wakefulness.

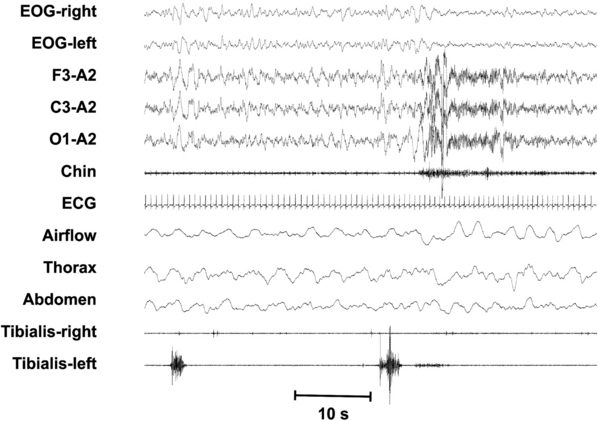

FIGURE 7.2 A leg movement is considered associated with an arousal when there is less than 0.5 seconds between the end of one event and the onset of the other, regardless of which is first. The periodic limb movements (PLM)/arousal index is the number of PLM events associated with arousal per hour of sleep.

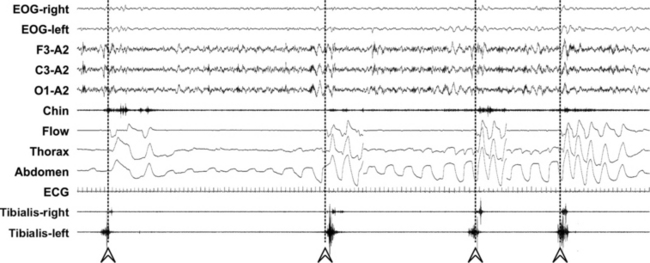

FIGURE 7.3 A leg movement is associated with the ending of an apnea/hypopnea event when they overlap or the offset of the earlier event precedes the onset of the other by less than 0.5 seconds, regardless of which is first; these leg movements are excluded from the computation of periodic limb movements–related parameters. Arrowheads and dashed lines indicate the resumption of breathing after apnea episodes.

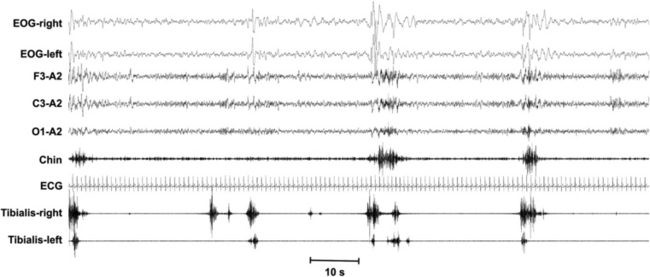

FIGURE 7.4 The leg motor activity during sleep also contains irregular short-interval movements interrupting the regular periodic sequences. Also long-interval movements (>90 seconds) are present that do not belong to the periodic activity. The degree of periodicity can be measured by means of the periodicity index (the number of movements in sequences of at least four separated by 10 to 90 seconds divided by the total number of movements, including those with intervals <10 seconds and >90 seconds). Note that for this analysis intervals of less than 5 seconds are also counted, in contrast to that for periodic limb movements index.

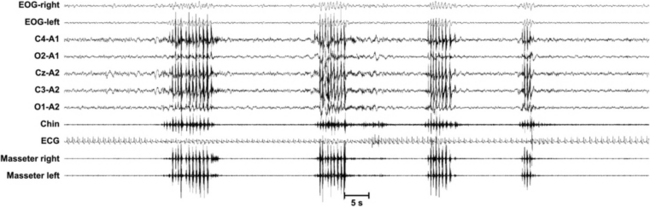

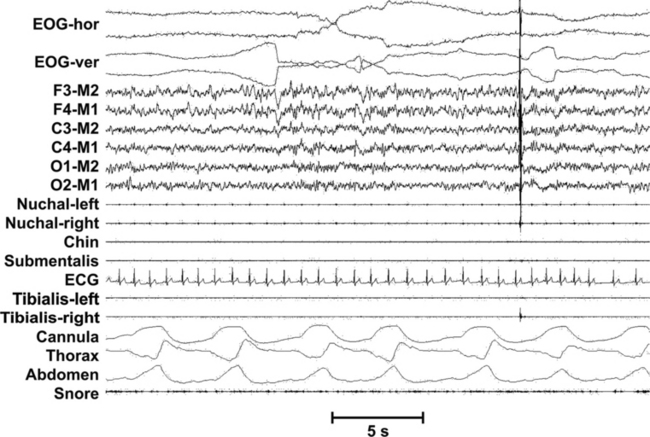

FIGURE 7.5 Polysomnographic recording of a sequence of rhythmical masticatory muscle activity (RMMA; at least three rhythmical phasic contractions at a frequency of 1 Hz, lasting between 0.25 and 2 seconds) episodes in one subject with sleep bruxism (SB). An episode of SB may consist of RMMA, tonic (sustained contraction for more than 2 seconds), or mixed phasic-tonic masticatory muscle activities, associated with tooth-grinding sound during sleep. Contractions shorter than 0.25 seconds are scored as myoclonus. Each SB episode has to be separated by a period of at least 3 seconds of stable background electromyogram (EMG) to be scored as a new SB episode. SB can be scored reliably by audio-video recording in combination with polysomnography, with a minimum of two audible tooth-grinding episodes per night, in the absence of epilepsy. The diagnosis of SB requires the presence of at least four episodes of SB per hour of sleep or at least 25 individual masticatory muscle bursts per hour of sleep, accompanied by at least two audible episodes of tooth-grinding noise. For the scoring of SB the recommended chin EMG electrodes have been indicated to be sufficient, but additional masseter and/or temporal EMG can be helpful, in accordance with the discretion of the investigator or clinician.

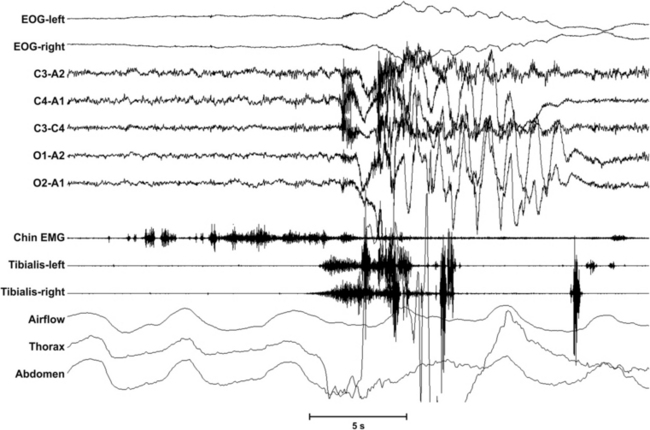

FIGURE 7.6 Polysomnographic recording of a rhythmical movement disorder episode. Rhythmical movement disorder consists of repetitive, stereotyped, and rhythmical motor behaviors, such as head banging, head rolling, body rocking, and body rolling. Because the movements involve large muscle groups, often the polysomnographic recording shows mainly movement artifacts. The behavior arises during wakefulness or during superficial sleep stages, rarely also in rapid eye movement sleep around arousals, for instance, respiratory arousals. If possible, the frequency of the repetitive movements should be reported (usually between 0.5 and 2 Hz) and the duration of the episode, and it should be indicated during which stage of wakefulness or sleep it arises, and/or if it is associated with an arousal.

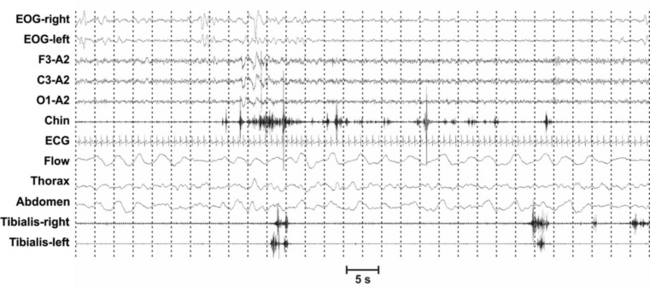

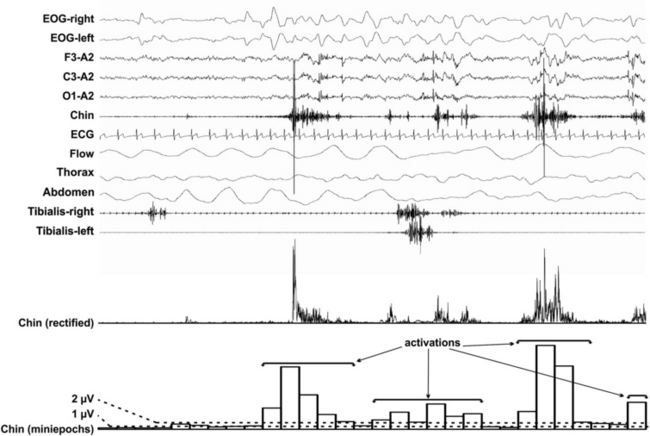

FIGURE 7.7 Excessive transient (phasic) chin electromyographic (EMG) activity bursts (0.1 to 5 seconds in duration and at least twice or four times as high in amplitude as the background EMG activity according to different systems) and periodic limb movements in sleep (tibialis anterior EMG channels) in a polysomnographic recording of a patient with rapid eye movement (REM) sleep behavior disorder. The phasic chin EMG activity can be quantified by subdividing REM sleep into 3-second miniepochs and counting those miniepochs, including phasic bursts as defined earlier, and then dividing this number by the total number of REM sleep miniepochs. In this example, 13 miniepochs out of 30 (43.3%) included phasic chin EMG activity.

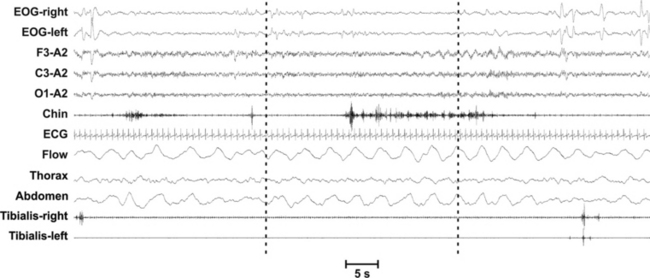

FIGURE 7.8 Excessive tonic chin electromyographic (EMG) activity (at least 50% of the duration of the epoch having a chin EMG amplitude greater than the minimum amplitude in non–rapid eye movement [NREM]) in the middle 30-second epoch in a polysomnographic recording of one patient with REM sleep behavior disorder (RBD). For “any” muscle activity (tonic, phasic) when using 3-second miniepochs the proposed cutoff for 100% specificity for RBD is 18.2, and 14.5 when analyzing based on 30-second epochs.

FIGURE 7.9 This figure gives an example of tonic and phasic muscle activity in the chin and phasic activity in the tibialis anterior muscles from a patient with rapid eye movement (REM) sleep behavior disorder (RBD). Quantification of “any” muscle activity in the chin (tonic or phasic) plus quantification of phasic muscle activity in two upper extremity muscles (flexor digitorum superficialis and biceps brachii) has a very high sensitivity and specificity for RBD (and has therefore been proposed as the preferred minimal muscle combination for diagnosis of RBD by the Sleep Innsbruck Barcelona [SINBAR] group). To achieve a 100% specificity for RBD, a cutoff of 31.9% for any chin and phasic flexor digitorum superficialis has been proposed when calculating quantification based on 3-second miniepochs, and 27.2% when using 30-second epochs. However, many laboratories will record electromyography only from chin and tibialis anterior muscles. Here the proposed cutoff for diagnosis of RBD is 46.4% for 3-second miniepochs, (any chin plus phasic tibial anterior from both sides), and 42.5% for 30-second epochs, but area under the curve for the combination chin-tibial anterior muscle is slightly lower.

FIGURE 7.10 Example of the calculation of the atonia index on one polysomnographic rapid eye movement (REM) sleep epoch of a patient with REM sleep behavior disorder. The chin electromyographic signal is first rectified, then its average amplitude for 1-second miniepochs is calculated. Activations are defined as single or sequences of consecutive miniepochs exceeding the threshold of 2 μV (16 miniepochs in this example); the atonia index is the ratio of the number of miniepochs exceeding the threshold of 2 μV to the total number of miniepochs, excluding those with average amplitude >1 ≤2 μV (five miniepochs in this example). Thus in this example, atonia index = 16/25 = 0.64. Total REM sleep atonia index >0.9 denotes normal atonia; atonia index ≥0.8 ≤0.9 indicates a mild/moderate atonia reduction, and atonia index <0.8 indicates clearly reduced atonia.

FIGURE 7.11 Polysomnographic recording of neck myoclonus (head jerk) characterized by a movement associated with a short stripe-shaped movement-induced artifact over the electroencephalographic leads during rapid eye movement sleep.

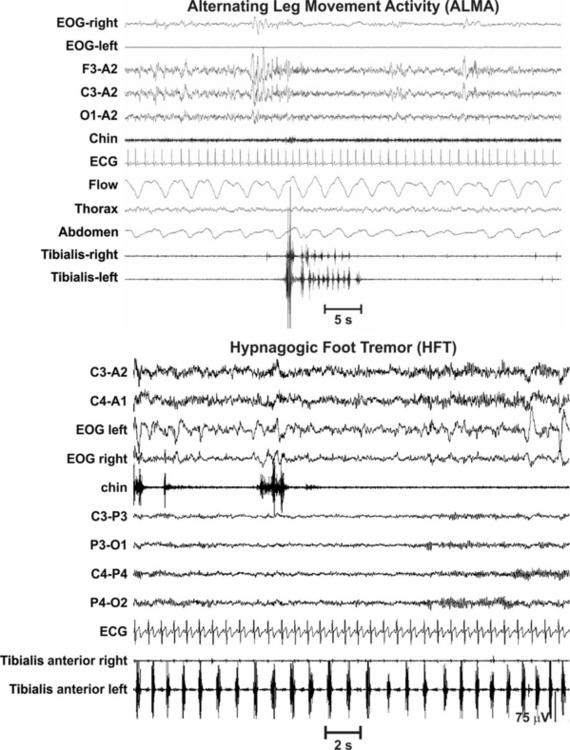

FIGURE 7.12 Top panel, Polysomnographic recording of alternating leg muscle activity during sleep, a quickly alternating pattern of anterior tibialis activation occurring at a frequency of approximately 1 to 2 Hz, lasting between 0.1 and 0.5 seconds each, organized in sequences of alternating activations lasting up to 20 to 30 seconds. Bottom panel, Hypnagogic foot tremor at the transition between wake and sleep or during light sleep; polysomnographic recordings show the presence of recurrent electromyographic (EMG) potentials or foot movements typically at 1 to 2 Hz (range 0.5 to 3 Hz) in one or both feet. The EMG bursts are longer than those of myoclonus (>250 milliseconds), last usually less than 1second, and are organized in trains lasting 10 or more seconds (see Chapters 9 and 10).

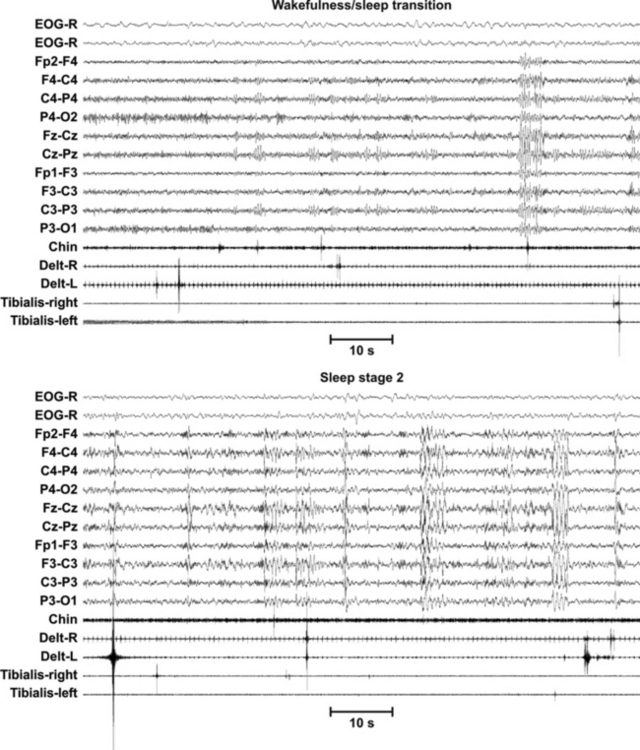

FIGURE 7.13 Excessive fragmentary myoclonus (EFM) at the wakefulness/sleep transition and during sleep stage N2. EFM is characterized at polysomnography by recurrent and persistent, very brief (75 to 150 milliseconds) electromyographic potentials in various muscles, occurring asynchronously and asymmetrically, in a sustained manner, without clustering. More than five potentials per minute should be sustained for at least 20 minutes of stage N2 or slow wave sleep. EFM can be quantified by means of the myoclonus index, which is defined as the number of 3-second miniepochs containing at least one fragmentary myoclonus potential fulfilling the criteria, counted for each 30-second epoch, and resulting in a number between 0 and 10.

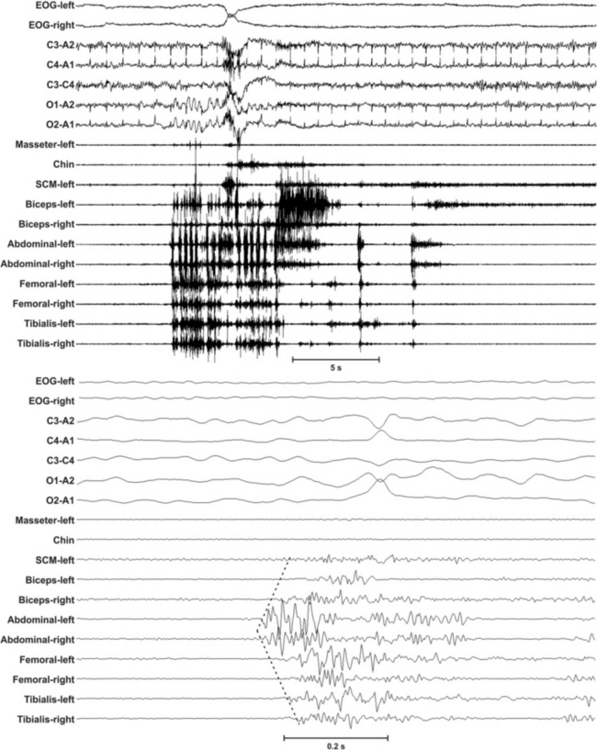

FIGURE 7.14 Spreading of muscle activation, rostrally and caudally, starting from abdominal muscles in one patient with propriospinal myoclonus (PSM). PSM is characterized by generalized and symmetrical jerks that arise during the transition between wakefulness and sleep, from axial muscles of the abdomen, thorax, or neck, and spread rostrally and caudally to the other myotomes by means of slow propriospinal polysynaptic pathways. No quantitative polysomnographic features have been described, and its description is basically qualitative. Femoral, Quadariceps femorias muscle.

Ferri, R., Rundo, F., Manconi, M., et al. Improved computation of the atonia index in normal controls and patients with REM sleep behavior disorder. Sleep Med. 2010; 11:947–949.

Frauscher, B., Hogl, B. REM sleep behavior disorder: discovery of RBD, clinical and laboratory diagnosis and treatment. In Chokroverty S., Allen R., Walters A., Montagna P., eds. : Sleep and Movement Disorders, 2nd ed., New York: Oxford University Press, 2013. [In press].

Frauscher, B., Iranzo, A., Gaig, C., et al. Normative EMG values during REM sleep for the diagnosis of REM sleep behavior disorder. Sleep. 2012; 35(6):835–847.

Iranzo, A., Frauscher, B., Santos, H., et al. Usefulness of the SINBAR (Sleep Innsbruck Barcelona) electromyographic montage to detect the motor and vocal manifestations occurring in REM sleep behavior disorder. Sleep Med. 2011; 12:284–288.