Motor Disorders During Sleep

Motor control in sleep is as complex as in wakefulness but clearly different. Sleep is considered a state of relative mental and physical inactivity; sleep, however, is not simply a state of passivity. We see both negative and positive phenomena during sleep. Furthermore, the status immediately before sleep onset (predormitum) and just before sleep offset in the morning (postdormitum) are distinct from sleep and wakefulness proper with different motor behavior (e.g., propriospinal myoclonus and hypnic jerks in predormitum and sleep inertia in postdormitum). Many diurnal abnormal movements continue in sleep but to a lesser degree than in wakefulness, whereas new adventitious movements may be triggered by sleep, causing the paradox of a sleeping brain with an active body. Modern technology using video-polysomnographic recordings and neuroimaging (positron emission tomography, single-photon emission computed tomography, and other functional magnetic resonance imaging displays) have opened up a new world of nocturnal events encompassing both physiological and pathological motor manifestations, shedding light on the pathophysiology of many sleep-related movement disorders.

The second edition of the International Classification of Sleep Disorders published in 2005 included a separate section devoted to sleep-related movement disorders. This category includes restless legs syndrome, periodic limb movements in sleep and periodic limb movement disorder, sleep-related leg cramps, sleep-related bruxism, sleep-related rhythmical movement disorders, and other sleep-related movement disorders caused by a known physiological condition or substance abuse and those not caused by a substance or known physiological condition (e.g., other psychiatric or behavioral sleep-related movement disorders). Most of the nosological entities characterized by prominent motor abnormalities are, however, included in the category of parasomnias (e.g., undesirable motor events and behavior occurring during sleep that do not necessarily disturb sleep architecture and that are not caused by abnormalities intrinsic to basic sleep mechanisms). Parasomnias include disorders of arousals (e.g., confusional arousals, sleepwalking, sleep terrors arising out of non–rapid eye movement [NREM] sleep), those associated with rapid eye movement (REM) sleep (e.g., REM sleep behavior disorder, parasomnia overlap disorder, status dissociatus, nightmares, and recurrent isolated sleep paralysis), and other parasomnias (e.g., nocturnal dissociative disorder, catathrenia or nocturnal groaning, exploding head syndrome, and sleep-related eating disorders). While we await a deeper understanding of the pathophysiological mechanisms, however, description remains the first step in the knowledge of a phenomenon. Video recordings and polygraphic pictures go a long way in helping clinicians to recognize and characterize the various movement abnormalities encountered in the everyday practice of sleep medicine. Therefore an atlas showing characteristic polysomnographic (PSG) features of different motor disorders arising during sleep provides a good guide in the interpretation of the tracings and helps technicians and physicians recognize patterns useful in the differential diagnosis. Figures 10.1 to 10.12 provide examples of PSG tracings and a brief clinical description for clinical-physiological correlation derived from the following motor disorders emerging during sleep: sleep terror (see Fig. 10.1), status dissociatus (see Fig. 10.2), propriospinal myoclonus at sleep onset (see Fig. 10.3), faciomandibular myoclonus (see Fig. 10.4), sleep-related eating disorder (see Fig. 10.5), bruxism (see Fig. 10.6), bruxism with catathrenia (see Fig. 10.7), hypnagogic foot tremor (see Fig. 10.8), alternating leg muscle activation (see Fig. 10.9), excessive fragmentary myoclonus (see Fig. 10.10), and confusional arousal (see Figs. 10.11 and 10 12).

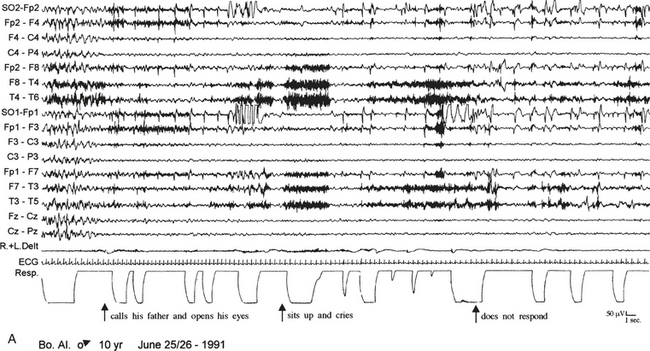

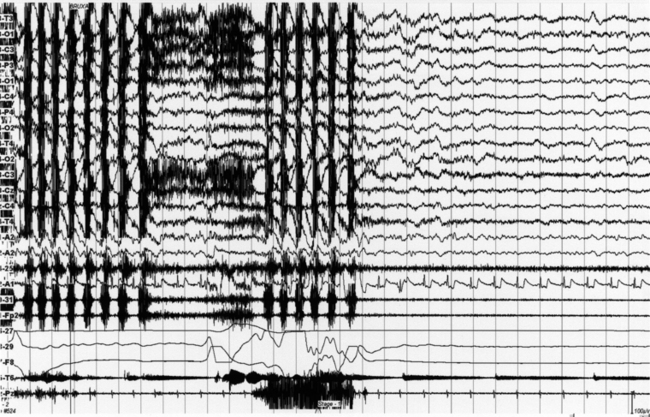

FIGURE 10.1 Sleep terror.

A 10-year-old boy presented with a 6-year history of sudden awakenings usually within 2 hours after sleep onset. A, During the episodes the patient sat up with a fearful expression and glassy eyes, vocalized and screamed with tachycardia, tachypnea, flushing of the skin, and mydriasis. The patient was confused and disoriented if awakened. The polysomnographic recording shows that the episode arises from stage N3 of sleep with a diffuse “hypersynchronous” rhythmical delta activity, deep inspiration, and tachycardia. At the beginning of the episode the patient calls his father, open his eyes, and cries, but electroencephalographic background activity remains slow. B, At the end of the episode the patient goes back to sleep. ECG, Electrocardiogram; top 16 channels, electroencephalogram (international nomenclature system); SO, supraorbital electrode; R.+L. Delt., right and left deltoideus muscle; Resp., thoracoabdominal respiration.

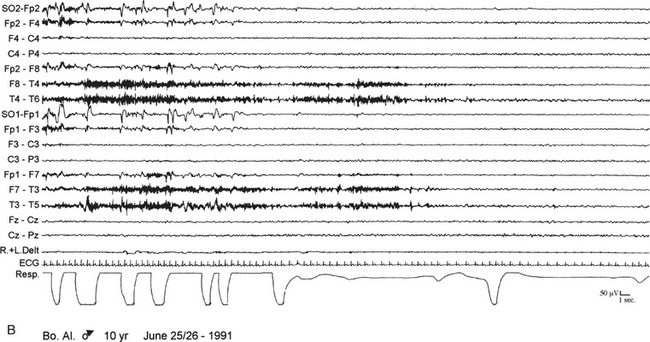

FIGURE 10.2 Status dissociatus.

A 66-year-old woman with harlequin syndrome suffered, approximately 1 year after right jaw and multiple limb trauma, restless sleep, interrupted by excessive motor and sometimes harmful activities associated with vocalization and a report of dreaming corresponding to the motor manifestations. Hypnagogic hallucinations and sleep paralysis rarely occurred. Polysomnographic tracing shows intermingled non–rapid eye movement (NREM) and rapid eye movement (REM) electroencephalographic features (top three channels). In particular, sleep spindles were observed during REM sleep patterns (sawtooth waves, desynchronized high-frequency/low-amplitude activity, and REMs). Mylohyoid (Mylo EMG) muscle atonia was not complete with brief, sudden twitches and tonic electromyographic bursts. Respiration shows irregular tracings of REM sleep. R-EOG, Right electro-oculogram; L-EOG, left electro-oculogram; Mylo, mylohyoideus; RtTib, right tibialis anterior; INTRC, intercostalis; THO Resp, thoracic respiration; ABD Resp, abdominal respiration; R.Pleth, right plethysmogram; L.Pleth, left plethysmogram; System. art. press., systemic arterial pressure.

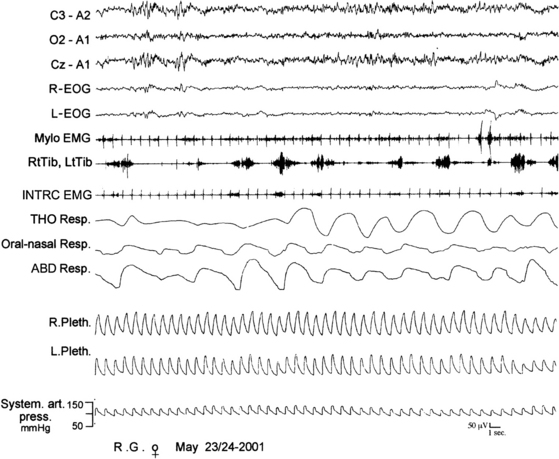

FIGURE 10.3 Propriospinal myoclonus at the wake-sleep transition.

A 40-year-old man presented with a 4-year history of axial jerks during relaxed wakefulness impeding falling asleep. Polysomnographic recording shows repetitive myoclonic axial jerks. The electromyographic activity originates in the left rectus abdominis muscle, thereafter propagating to rostral (sternocleidomastoid, masseter, mylohyoid) and caudal (biceps femoris) muscles. The panel on the left shows jerks at low speed; the right panel shows one of the jerks at high speed. The arrow in the right panel shows the onset of the jerk originating form the left rectus abdominis muscle. The asterisk shows muscle artifacts in the EEG channels concomitant with the jerks. R., Right; L., left; Mylo, mylohyoideus; S.C.M., sternocleidomastoideus; INTRC, intercostalis; Rectus abd., rectus abdominis; Rectus fem., rectus femoris; Biceps fem., biceps femoris; top two channels, electroencephalogram. ![]() (See Video Vignette 12.)

(See Video Vignette 12.)

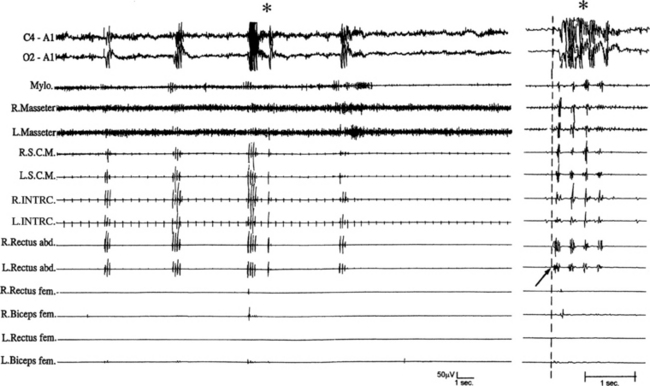

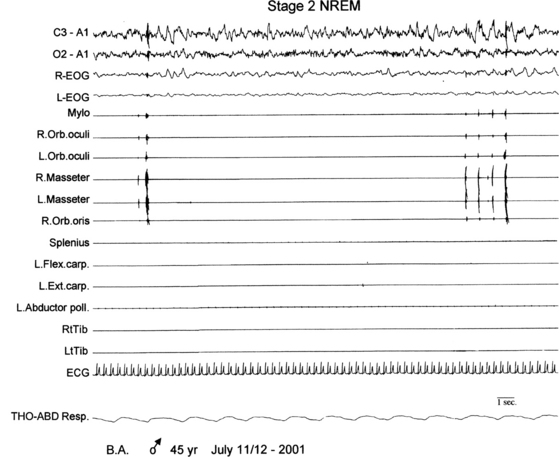

FIGURE 10.4 Faciomandibular myoclonus.

A 45-year-old man presented nocturnal tongue biting and bleeding since age 25 years. Nocturnal polysomnographic re-cording shows myoclonic electromyographic activity of mylohyoid, orbicularis oculi and oris, or masseter muscles during non–rapid eye movement sleep. R, Right; L, left; L-EOG and R-EOG, left and right electro-oculogram; Mylo, mylohyoideus; Orb. oculi, orbicularis oculi; Orb. oris, orbicularis oris; Flex. carp., flexor carpi; Ext. carp., extensor carpi; Abductor poll., abductor pollicis; RtTib, LtTib, right and left tibialis anterior; THO-ABD Resp., thoracoabdominal respiration; top two channels, electroencephalogram.

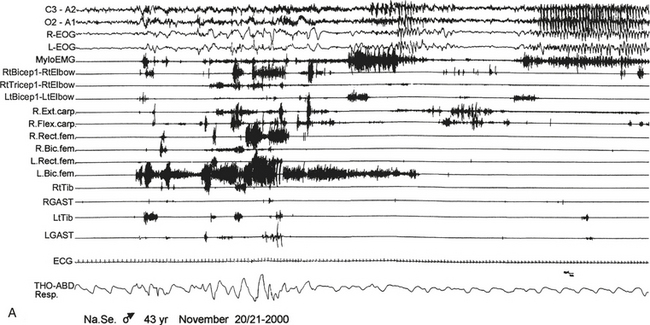

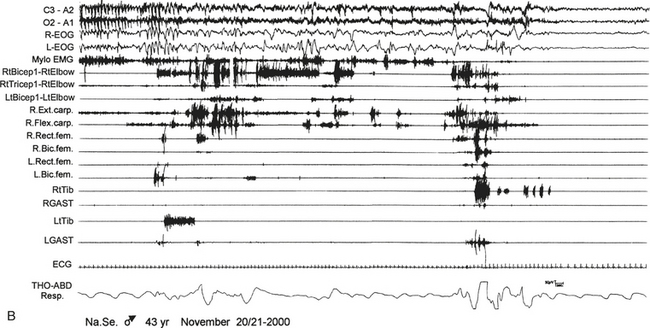

FIGURE 10.5 Sleep-related eating disorder.

A 43-year-old man presented with a history of 20 years of abrupt awakenings from nocturnal sleep associated with compulsive feeding behavior out of control. Polysomnographic recording shows an episode of eating behavior arising from sleep (stage II). A, The patient wakes up and after 40 seconds begins to eat a snack put on a cart near his bed (observe the artifact of mastication on electroencephalogram channels); then he lies down and goes back to sleep (end of B). Top two channels in A and B, Electroencephalogram; R., right; L., left; L-EOG and R-EOG, left and right electro-oculogram; Mylo, mylohyoideus; RtBicep1-RtElbow and LtBicep1-LtElbow, right and left biceps brachii; RtTricep1-RtElbow, right triceps brachii; Ext. carp, extensor carpi; Flex. carp, flexor carpi; Rect. fem, rectus femori; Bic. fem, biceps femori; RtTib and LtTib, right and left tibialis anterior; RGAST and LGAST, right and left gastrocnemius; THO-ABD Resp., thoracoabdominal respiration.![]() (See Video Vignette 13.)

(See Video Vignette 13.)

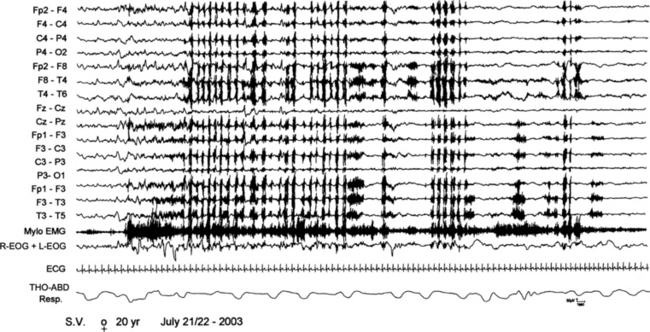

FIGURE 10.6 A 20-year-old woman referred for sudden nocturnal awakenings with vocalization and sleepwalking. Polysomnogram shows an arousal from non–rapid eye movement stage IV sleep with subsequent rhythmic masticatory muscles activation and teeth gnashing (electromyographic artifacts on electroencephalogram channels) typical of sleep bruxism. Top 15 channels, Electroencephalogram; Mylo EMG, mylohyoid EMC activity; R-EOG + L-EOG, right and left electro-oculogram; ECG, electrocardiogram; THO-ABD Resp, thoracoabdominal respiration.

FIGURE 10.7 Bruxism with episodes of nocturnal groaning (a rare rapid eye movement parasomnia but sometimes with non-REM–related episodes too, with a noisy “lament” in expiration) in a 31-year-old man with a history of bruxism for more than 10 years (orthodontic surgery at that time). He gives a history of a nocturnal noise during sleep (obtained from his wife) for 2 years. The groaning episode on the polysomnogram is characterized by a prolonged central apnea in expiration associated with groaning noise. Top 14 channels, Electroencephalogram; Pg1-A2 and Pg2-A2, left and right electro-oculograms; submental EMG (24-25); electrocardiogram (32-A1); Masseter EMG (30-31 and FP1-FP2); oronasal (26-27) airflow; thoracic (28-29) and abdominal (F7-F8) respiratory effort channels.

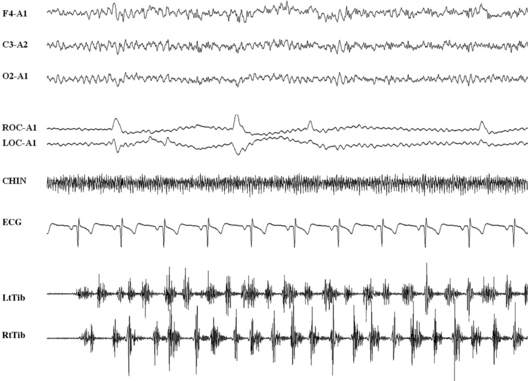

FIGURE 10.8 Hypnagogic foot tremor.

A 69-year-old man affected by snoring and nonrestorative sleep. Thirty seconds of polysomnographic example of rest wakefulness. A series of rapid tibialis anterior activations longer than 30 seconds, with single burst duration of 200 to 300 msec. Top three channels, Electroencephalogram; ROC and LOC, right and left ocular canthus; ECG, electrocardiogram; RtTib and LtTib, right and left tibialis anterior muscles. See also Chapter 7.

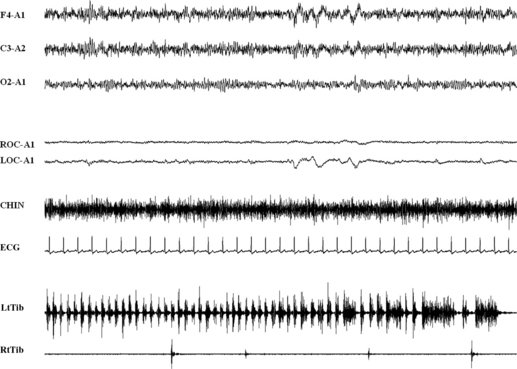

FIGURE 10.9 Alternating leg muscle activation.

A 32-year-old man with a history of chronic insomnia without comorbidity with restless legs syndrome. Ten seconds of polysomnographic example of a transition from rest wakefulness to N1 sleep. A series of alternating tibialis anterior activations longer than 10 seconds, with single burst duration of 200 to 300 msec. Top three channels, Electroencephalogram; ROC and LOC, right and left ocular canthus; ECG, electrocardiogram; RtTib and LtTib, right and left tibialis anterior muscles. See also Chapters 7 and 9.

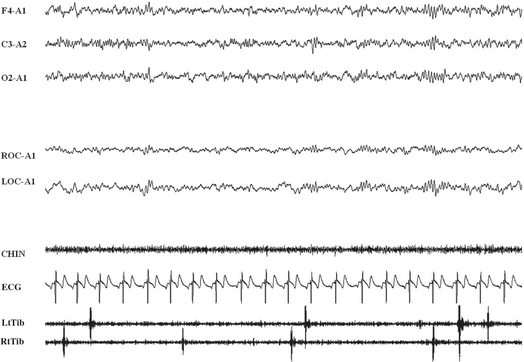

FIGURE 10.10 Excessive fragmentary myoclonus (EFM).

A 71-year-old man presented a 2-year history of continuous twitchlike movements in parts of his arms and legs throughout the night. The movements came and went without causing any sleep disturbance. His wife noticed tiny movements of the fingers or toes that did not wake the patient. No movement across a joint space was observed, and the patient was totally unaware of movements. These movements were isolated phenomena. The patient did not report insomnia, excessive daytime somnolence, obstructive sleep apnea, or rapid eye movement (REM) sleep behavior disorder. The polysomnographic tracing documented very brief electromyographic potential in muscle traces at the transition from wake to sleep (stage 1 non-REM sleep) and during REM sleep. The potentials occurred asynchronously and asymmetrically and were seldom associated with a visible movement. EFM is considered an abnormal intensification of physiological hypnic fragmentary myoclonus. Top three channels, Electroencephalogram (Cz-A1); R, right; L, left; EOC, electro-oculogram; Mylo, mylohyoideus; ECG, electrocardiogram; RtTib and LtTib, right and left tibialis anterior; CHIN, chin electromyogram activity.

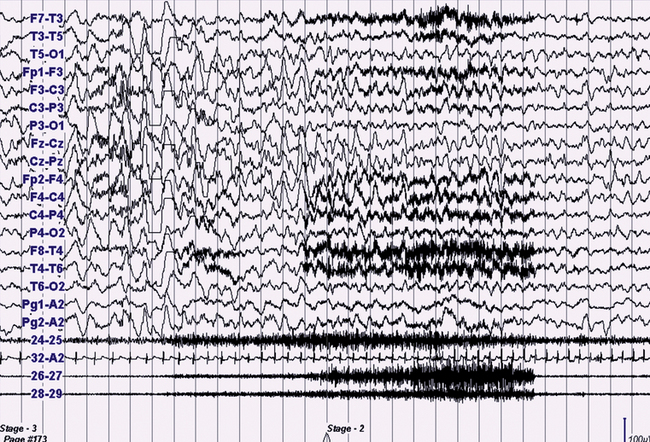

FIGURE 10.11 Confusional arousal.

A 13-year-old boy presented with a 3-year history of nocturnal complex episodes (e.g., sleepwalking or screaming) associated with tachycardia without morning recall and with a frequency of two to three nights a week and sometimes multiple episodes per night. The episodes were more frequent during the first half of the night or during daytime naps. There is a positive familial history (mother) for similar episodes until 15 years of age. The polysomnographic recording (30-second epoch) shows an episode emerging from N3, with electroencephalographic (EEG) rhythmical slow wave activity, tachycardia, and increased electromyographic (EMG) activity. The patient sat up slowly in bed, looked around with confusion, uttering some meaningless words and apparently with no awareness for at least 2 minutes. Top 16 channels, EEG (international electrode placement); Pg1-A2 and Pg2-A2, left and right eletro-oculogram; 24-25, chin EMG; 32-A2, electrocardiogram; 26-27, right deltoid EMG; 28-29, left deltoid EMG.

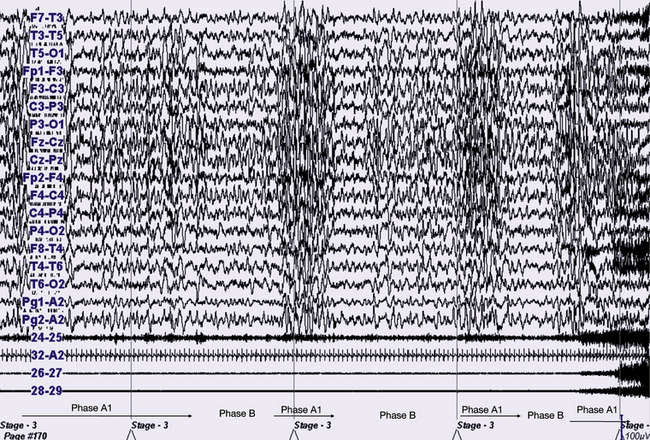

FIGURE 10.12 The same patient and the same episode as in Figure 10.11, with slow speed (60-second epoch). Polysomnogram is showing sleep instability preceding the confusional arousal episode. It is clearly a cyclic alternating pattern during stage N3 epochs alternating with phase A1 and phase B. The episode clearly starts during a phase A1.

Chokroverty, S. Sleep Disorders Medicine: Basic Science, Technical Considerations and Clinical Aspects, 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2009.

Chokroverty, S., Allen, R., Walters, A., Montagna, P. Sleep and Movement Disorders, 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 2013. [In press].

Kryger, M., Roth, T., Dement, W. Principles and Practice of Sleep Medicine, 4th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2011.