Postoperative Analgesia

Epidural and Spinal Techniques

Brendan Carvalho MBBCh, FRCA, MDCH, Alexander Butwick MBBS, FRCA, MS

Chapter Outline

NEURAXIAL TECHNIQUES FOR CESAREAN DELIVERY

EFFICACY AND BENEFITS OF NEURAXIAL ANALGESIA

PHARMACOLOGY OF NEURAXIAL OPIOIDS

Central Nervous System Penetration

Distribution and Movement of Opioids within the Central Nervous System

Patient-Controlled Epidural Analgesia

Extended-Release Epidural Morphine

Intrathecal Opioid Combinations

Maternal Safety and Neonatal Effects

SIDE EFFECTS OF NEURAXIAL OPIOIDS

NEURAXIAL NONOPIOID ANALGESIC ADJUVANTS

N-Methyl-D-Aspartate Antagonists

The cesarean delivery rate in the United States has steadily increased as a result of changing patterns in obstetric practice,1 and recent data indicate that more than 1 million cesarean deliveries are now performed annually in the United States.2 With cesarean delivery accounting for an ever-increasing proportion of all deliveries in the United States and in many other developed countries,3 strategies for reducing adverse postcesarean maternal outcomes, including postoperative pain, have important clinical and public health implications.

Postoperative pain after cesarean delivery can be moderate to severe and is equivalent to that reported after abdominal hysterectomy.4 Management of postoperative pain is frequently substandard, with 30% to 80% of patients experiencing moderate to severe postoperative pain.5,6 In an effort to improve pain management in the United States, The Joint Commission has stated that postoperative pain should be the “fifth vital sign.”7 The Joint Commission also proposed the goal of having patients experience uniformly low postoperative pain scores of less than 3 (based on a numerical pain scale [0 to 10] at rest and with movement). In the United Kingdom, the Royal College of Anaesthetists8 has proposed the following standards for adequate postcesarean analgesia:

1. More than 90% of women should have a pain score of less than 3 (as measured by a numerical pain scale [0 to 10]).

2. More than 90% of women should be satisfied with their pain management.8

A 2007 study suggested that these goals for postcesarean analgesia and maternal satisfaction are frequently not attained.9 A sample of expectant mothers attending birthing classes identified pain during and after cesarean delivery as their most important concern (Table 28-1).10 Effective pain management should be highlighted as an essential element of postoperative care.

TABLE 28-1

Women's Ranking and Relative Value of Potential Anesthesia Outcomes before Cesarean Delivery*

| Outcome | Rank† | Relative Value‡ |

| Pain during cesarean delivery | 8.4 ± 2.2 | 27 ± 18 |

| Pain after cesarean delivery | 8.3 ± 1.8 | 18 ± 10 |

| Vomiting | 7.8 ± 1.5 | 12 ± 7 |

| Nausea | 6.8 ± 1.7 | 11 ± 7 |

| Cramping | 6.0 ± 1.9 | 10 ± 8 |

| Itching | 5.6 ± 2.1 | 9 ± 8 |

| Shivering | 4.6 ± 1.7 | 6 ± 6 |

| Anxiety | 4.1 ± 1.9 | 5 ± 4 |

| Somnolence | 2.9 ± 1.4 | 3 ± 3 |

| Normal | 1 | 0 |

* Data are mean ± standard deviation.

† Rank = 1 to 10 from the most desirable (1) to the least desirable (10) outcome.

‡ Relative value = dollar value patients would pay to avoid an outcome (e.g., they would pay $27 of a theoretical $100 to avoid pain during cesarean delivery).

From Carvalho B, Cohen SE, Lipman SS, et al. Patient preferences for anesthesia outcomes associated with cesarean delivery. Anesth Analg 2005; 101:1182-7.

Neuraxial Techniques for Cesarean Delivery

In the United States and the United Kingdom, most cesarean deliveries are performed with neuraxial anesthesia (spinal, epidural, or combined spinal-epidural [CSE] techniques).11-13 A meta-analysis found no differences between spinal and epidural anesthetic techniques with regard to failure rate, additional requests for intraoperative analgesia, need for conversion to general anesthesia, maternal satisfaction, postoperative analgesic requirements, or neonatal outcomes.14 There may be other nonclinical factors that influence the choice of neuraxial anesthetic technique for cesarean delivery. Spinal anesthesia has been shown to be more cost effective than epidural anesthesia for cesarean delivery, because needle placement is technically less challenging and adequate surgical anesthesia is achieved more rapidly.15 These advantages, combined with the low incidence of post–dural puncture headache with non-cutting spinal needles (see Chapter 12), have increased the popularity of spinal-based anesthetic techniques for patients undergoing cesarean delivery. A 2008 survey of members of the Society for Obstetric Anesthesia and Perinatology found that 85% of elective cesarean deliveries are performed with spinal anesthesia.13 A workforce survey in the United States demonstrated that the majority of laboring women receive epidural analgesia.11 If a patient receiving epidural analgesia during labor subsequently requires a cesarean delivery, most anesthesia providers choose to administer medications through the epidural catheter to achieve adequate surgical anesthesia (see Chapter 26).11-13

A CSE technique incorporates the rapid onset of spinal anesthesia with placement of an epidural catheter for supplementation of intraoperative anesthesia and/or for provision of postoperative analgesia. The CSE technique is increasingly used when prolonged duration of surgery is anticipated (e.g., obesity, multiple previous surgeries).16 After surgery, patients with an epidural catheter in situ may benefit from intermittent bolus injection or continuous epidural infusion of local anesthetic and/or opioid for postoperative analgesia.

Efficacy and Benefits of Neuraxial Analgesia

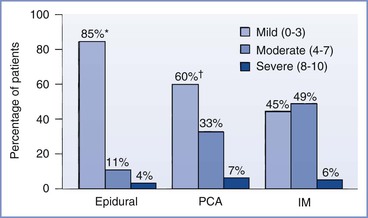

Neuraxial opioid administration currently represents the “gold standard” for providing effective postcesarean analgesia. A meta-analysis of studies involving a broad population of patients undergoing a variety of surgical procedures confirmed that opioids delivered by either patient-controlled epidural analgesia (PCEA) or continuous epidural infusion (CEI) provide postoperative pain relief that is superior to that provided by intravenous patient-controlled analgesia (PCA).17 Similar results have been reported in studies comparing intrathecal and epidural opioid administration with intravenous opioid PCA or intramuscular opioid administration after cesarean delivery (Figure 28-1).18-21 A 2010 systematic review found that neuraxial morphine provides better analgesia than parenteral opioids after cesarean delivery.22 Neuraxial opioids also provide postcesarean analgesia that is superior to that provided by local anesthetic techniques (e.g., transversus abdominis plane blocks) and oral analgesics (e.g., nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [NSAIDs], opioids) (see Chapter 27).23-26 Wound infiltration of a local anesthetic has been proposed as an alternative to an epidural technique for postcesarean analgesia27,28; however, the efficacy and reliability of this technique are variable.29-31 Intrathecal morphine is particularly effective after abdominal surgery.32 Although neuraxial analgesia offers important benefits in optimizing postoperative analgesia, multimodal analgesic strategies should be used to augment the analgesic effect of neuraxial opioids in this setting.25

FIGURE 28-1 Randomized trial of postcesarean analgesia with epidural analgesia, intravenous patient-controlled analgesia (PCA), or intramuscular (IM) administration of morphine. Percentage of patients reporting mild, moderate, or severe discomfort during a 24-hour study period. *P < .05, epidural versus PCA and IM; †P = NS, PCA versus IM. (From Harrison DM, Sinatra RS, Morgese L, et al. Epidural narcotic and PCA for postcesarean section pain relief. Anesthesiology 1988; 68:454-7.)

Persistent and chronic incisional and pelvic pain have been described after cesarean delivery, with an incidence of 1% to 15%.33-41 Psychosocial and pathophysiologic factors may also increase the likelihood of chronic postoperative pain.42,43 Severe acute postoperative pain is one of the most prominent associated factors.34,37,42,44 The development of chronic pain after surgery has been associated with central sensitization, hyperalgesia, and allodynia. Measures to attenuate or prevent pain sensitization may reduce the likelihood of development of chronic postoperative pain. Studies have shown that the use of perioperative neuraxial blockade may prevent central sensitization and chronic pain.33,45,46 De Kock et al.45 found that intrathecal clonidine, administered before colonic surgery, had antihyperalgesic effects and resulted in less residual pain 6 months after surgery than did placebo. Lavand'homme et al.46 reported that the administration of a multimodal antihyperalgesic regimen (intraoperative intravenous ketamine and epidural analgesia with bupivacaine, sufentanil, and clonidine) was associated with a lower incidence of residual pain 1 year after colonic surgery compared with intravenous analgesia administered during and after surgery. A study investigating risk factors for chronic pain after hysterectomy found that spinal anesthesia was associated with a lower frequency of chronic postoperative pain compared with general anesthesia.47 In another study, persistent postoperative pain was more frequent after cesarean delivery performed with general anesthesia compared with neuraxial anesthesia.34 Additional mechanistic and clinical research is needed to improve our understanding of persistent pain after cesarean delivery and to improve current treatment regimens for managing patients with postcesarean-related pain syndromes.

Although neuraxial opioids provide postcesarean analgesia that is superior to that provided by systemic opioids, some opioid-related side effects (e.g., pruritus) commonly occur after neuraxial opioid administration.18,48,49 Both higher49,50 and lower21,51 maternal satisfaction scores have been reported with neuraxial opioid administration for postcesarean analgesia. This variability in reported maternal satisfaction scores may be influenced by how patients judge analgesic quality against the presence and severity of opioid-related side effects (e.g., pruritus, nausea and vomiting).

Neuraxial anesthetic and analgesic techniques may also confer important physiologic benefits that decrease perioperative complications and improve postoperative outcomes.52-54 The potential benefits include a lower incidence of pulmonary infection and pulmonary embolism, an earlier return of gastrointestinal function, fewer cardiovascular and coagulation disturbances, and a reduction in inflammatory and stress-induced responses to surgery.52-54 In contrast to the wealth of data from clinical studies and meta-analyses that have shown a reduction in postoperative pain with neuraxial analgesia, there is less consistent evidence linking neuraxial anesthesia with a reduction in postoperative morbidity and mortality.52,55

Most patients undergoing cesarean delivery are young, healthy, and at low risk for major perioperative morbidity and mortality. For this patient population, the benefits of neuraxial analgesia include better postoperative analgesia, increased functional ability, earlier ambulation, and earlier return of bowel function.56-59 However, differences in postcesarean complication rates with the use of neuraxial versus systemic opioid analgesia have not been definitively demonstrated.56,60 Surgical trauma and postoperative immobility are associated with an increased risk for postoperative deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. The risk for venous thromboembolism is 6-fold higher in pregnant women and 10-fold higher in puerperal women than in nonpregnant women of similar age.61 In theory, early ambulation and avoidance of prolonged immobility may reduce the risk for postpartum deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. Effective postoperative analgesia can reduce pain on movement, thereby facilitating deep breathing, coughing, and early ambulation. These beneficial effects may lead to a reduction in the incidence of pulmonary complications (i.e., atelectasis, pneumonia) after cesarean delivery.

Neuraxial analgesic techniques may be more likely to reduce perioperative morbidity in high-risk obstetric patients. Women with severe preeclampsia, cardiovascular disease, and morbid obesity may benefit from the reduction in cardiovascular stress and improved pulmonary function associated with effective postcesarean analgesia.62,63 Rawal et al.63 compared the efficacy of intramuscular versus epidural morphine in 30 nonpregnant, morbidly obese patients after abdominal surgery. Patients in the epidural morphine group were more alert, ambulated more quickly, recovered bowel function earlier, and had fewer pulmonary complications.

Investigators have found that CEI of an opioid with a dilute solution of local anesthetic attenuates coagulation abnormalities, hemodynamic fluctuation, and stress hormone responses in nonpregnant patients.64-66 Some studies have suggested that opioid-based PCEA may improve postoperative outcome.67-69 Patients treated with PCEA meperidine after cesarean delivery ambulated more quickly and experienced an earlier return of gastrointestinal function compared with similar patients who received intravenous meperidine PCA.67

Pharmacology of Neuraxial Opioids

Prior to 1974, investigators speculated that the analgesic effect of opioids was due to pain modulation at supraspinal centers or increased activation of descending inhibitory pathways, without a direct effect at the spinal cord. The identification of endogenous opioid peptides, specific opioid binding sites, and opioid receptor subtypes has helped to clarify the site and mechanism of action of opioids within the central nervous system (CNS).70-73 The discovery that opioid receptors are localized within discrete areas in the CNS (laminae I, II, and V of the dorsal horn) suggested that exogenous opioids could be administered neuraxially to produce antinociception. Opioids administered to superficial layers of the dorsal horn produced selective analgesia of prolonged duration without affecting motor function, sympathetic tone, or proprioception.74 In addition, the analgesia provided by intraspinal opioids suggested that many of the unwanted side effects of intraspinal local anesthetic administration could be avoided.75 In 1979, Wang et al.76 published the first report of intraspinal opioid administration in humans. Intrathecal morphine (0.5 to 1 mg) produced complete pain relief for 12 to 24 hours in six of eight patients suffering from intractable cancer pain, with no evidence of sedation, respiratory depression, or impairment of motor function. Subsequently, researchers and clinicians have validated the analgesic efficacy of neuraxial opioids.

Central Nervous System Penetration

Opioids administered epidurally must penetrate the dura, pia, and arachnoid membranes to reach the dorsal horn and activate the spinal opioid receptors. The arachnoid layer is the primary barrier to drug transfer into the spinal cord.77 Movement through this layer is passive and depends on the physicochemical properties of the opioid. Drugs penetrating this arachnoid layer must first move into a lipid bilayer membrane, then traverse the hydrophilic cell itself, and finally partition into the other cell membrane before entering the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). Opioid penetration of spinal tissue is proportional to the drug's lipid solubility. Opioids that are highly lipid soluble (e.g., sufentanil, fentanyl) are unable to cross the hydrophilic cell, whereas those that are hydrophilic have difficulty crossing the lipid membrane.78 Highly lipid-soluble drugs have poor CSF bioavailability because of (1) poor penetration through the arachnoid layer, (2) rapid absorption and sequestration by epidural fat, and (3) high vascular uptake by epidural veins.

Some investigators have questioned the neuraxial specificity of lipophilic opioids given epidurally and have suggested that the primary analgesic effect occurs via vascular uptake, systemic absorption, and redistribution of the drug to supraspinal sites.79-84 Earlier studies suggested that parenteral fentanyl provides analgesia equivalent to that provided by epidural fentanyl.84,85 Investigators postulated that systemic absorption of fentanyl from the epidural space resulted in the subsequent analgesic effect.84,85 Ionescu et al.86 reported that plasma levels of sufentanil were comparable throughout a 3-hour sampling interval after epidural or intravenous injection. In contrast, more recent evidence suggests that epidural fentanyl provides analgesia via a spinal mechanism.87-89 Cohen et al.,90 comparing a continuous infusion of intravenous fentanyl with epidural fentanyl after cesarean delivery, reported improved analgesia and less supplemental analgesic consumption despite lower plasma fentanyl levels with epidural administration. There is evidence that bolus administration of lipophilic opioids has both spinal and supraspinal effects in obstetric patients.87-89 After the administration of an epidural bolus of sufentanil 50 µg,* CSF concentrations of sufentanil were 140 times greater than those found in plasma; however, the amount detected in cisternal CSF was only 5% of that measured in lumbar CSF.91

Hydrophilic morphine has a higher CSF bioavailability, with better penetration into the CSF and less systemic absorption. A bolus dose of epidural morphine 6 mg results in peak plasma concentration of 34 ng/mL at 15 minutes after administration and a peak CSF concentration of approximately 1000 ng/mL at 1 hour.92 A poor correlation between the analgesic effect and plasma levels of morphine has been observed after epidural administration, indicating a predominantly spinal location of action.93,94

Intrathecal administration allows for injection of the drug directly into the CSF. This is a more efficient method of delivering opioid to spinal cord receptors than epidural or parenteral administration. A bolus dose of intrathecal morphine 0.5 mg results in a CSF concentration higher than 10,000 ng/mL, with barely detectable plasma concentrations.95

Distribution and Movement of Opioids within the Central Nervous System

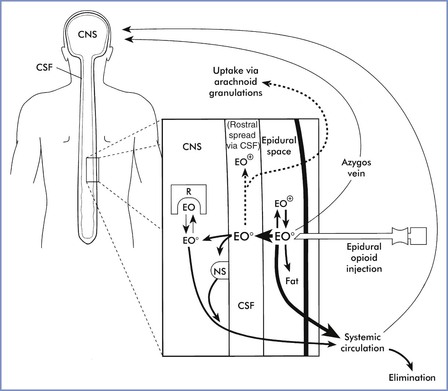

The movement and distribution of opioids within the CNS has been described as follows (Figure 28-2):

1. Movement in the spinal cord (white and gray matter). Lipophilic agents (e.g., fentanyl) are taken up by the white matter with much greater affinity than hydrophilic agents (e.g., morphine), and less drug will reach the dorsal horn in the gray matter.77,78,96

2. Movement within the epidural space (and subsequently epidural fat or veins). Lipophilic agents are more likely to be absorbed and transported from the epidural space to the systemic circulation.

3. Rostral spread in the CSF to the brainstem. Rostral spread is determined by CSF drug bioavailability and the drug concentration gradient; hydrophilic opioids (e.g., morphine) are associated with more rostral spread.91,97

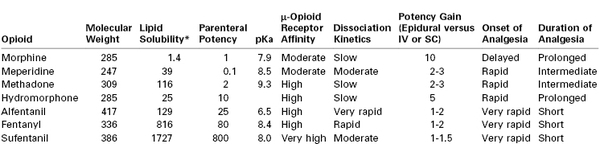

Although opioid dose, volume of injectate, and degree of ionization are important variables, lipid solubility plays the key role in determining the onset of analgesia, the dermatomal spread, and the duration of activity (Table 28-2).80,98 Highly lipid-soluble opioids penetrate the spinal cord more rapidly and have a quicker onset of action than more ionized water-soluble agents. The duration of activity is affected by the rate of clearance of the drug from the sites of activity. Lipid-soluble opioids are rapidly absorbed from the epidural space, whereas hydrophilic agents remain in the CSF and spinal tissues for a longer time (see Figure 28-2).80,98 Sufentanil is more lipid soluble than fentanyl; however, sufentanil has a greater µ-opioid receptor affinity, resulting in a comparatively longer duration of analgesia after neuraxial administration.

FIGURE 28-2 Factors that influence dural penetration, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) sequestration, and vascular clearance of epidurally administered opioids. The major portion of epidurally administered opioids (EO) is absorbed by epidural and spinal blood vessels or dissolved into epidural fat. Molecules taken up by the epidural plexus and azygos system may recirculate to supraspinal centers and mediate central opioid effects. A smaller percentage of uncharged opioid molecules (EO0) traverse the dura and enter the CSF. Lipophilic opioids rapidly exit the CSF and penetrate into spinal tissue. As with intrathecal dosing, the majority of these molecules either are trapped within lipid membranes (nonspecific binding sites [NS]) or are rapidly removed by the spinal vasculature. A small fraction of molecules bind to and activate opioid receptors (R). Hydrophilic opioids penetrate pia-arachnoid membranes and spinal tissue slowly. A larger proportion of these molecules remain sequestered in CSF and are slowly transported rostrally. This CSF depot permits gradual spinal uptake, greater dermatomal spread, and a prolonged duration of activity. CNS, central nervous system; EO+, charged epidurally administered opioid molecules. (From Sinatra RS. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of spinal opioids. In Sinatra RS, Hord AH, Ginsberg B, Preble LM, editors. Acute Pain: Mechanisms and Management. St. Louis, Mosby, 1992:106.)

TABLE 28-2

Spinal Opioid Physiochemistry and Pharmacodynamics

* Octanol-water partition coefficient at pH of 7.4.

IV, Intravenous; SC, subcutaneous.

Intrathecal and epidural opioids often produce analgesia of greater intensity than similar doses administered parenterally. The gain in potency is inversely proportional to the lipid solubility of the agent used. Hydrophilic opioids exhibit the greatest gain in potency; the potency ratio for intrathecal to systemic morphine is approximately 1 : 100.98,99

Epidural Opioids

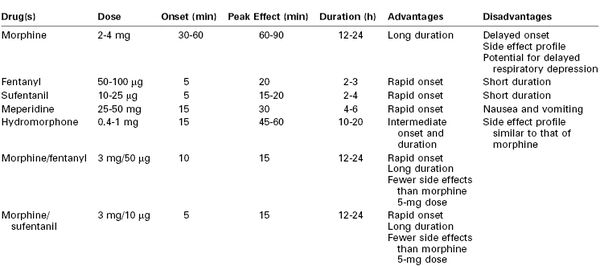

The provision of cesarean delivery anesthesia using an epidural catheter (placed during labor or as part of a CSE technique) has prompted an extensive evaluation of epidural opioids to facilitate postoperative analgesia (Table 28-3).

Morphine

Preservative-free morphine received U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval for neuraxial administration in 1984, and subsequently epidural morphine administration has been widely investigated and extensively used.100 Epidural administration of morphine provides postcesarean analgesia superior to that provided by intravenous or intramuscular morphine.18-21 A meta-analysis concluded that epidural morphine administration increases the time to first analgesic request, decreases pain scores, and reduces postoperative analgesic requests during the first 24 hours after cesarean delivery compared with systemic opioid administration.22 However, epidural morphine administration is associated with an increased risk for pruritus (relative risk [RR], 2.7; 95% confidence interval [CI], 2.1 to 3.6) and nausea (RR, 2.0; 95% CI, 1.2 to 3.3), compared with systemic opioid administration.22

Onset and Duration

After epidural administration, plasma morphine concentrations are similar to those observed after intramuscular injection. Epidural morphine has a relatively slow onset of action, as a result of its low lipid solubility and slower penetration into spinal tissue.80-82,98 The peak analgesic effect is observed 60 to 90 minutes after epidural administration.92 Nonetheless, we prefer to delay epidural morphine administration until immediately after delivery of the infant, or later if maternal hemodynamic instability warrants further delay.

Morphine has a prolonged duration of analgesia, and analgesic efficacy typically persists long after plasma concentrations have declined to subtherapeutic levels.80,92,98 Epidural morphine provides pain relief for approximately 24 hours after cesarean delivery58,101-103; however, there is wide variation in analgesic duration and efficacy among patients. Within the narrow range of doses studied, investigators have not demonstrated a correlation between the dose of morphine and the duration of analgesia.101,103,104

The volume of the diluent does not appear to affect the pharmacokinetics or clinical activity of epidural morphine. The quality and duration of analgesia, the need for supplemental analgesics, and the incidence of side effects were similar when epidural morphine 4 mg was administered with 2, 10, and 20 mL of sterile saline.105

The choice of local anesthetic used for epidural anesthesia may affect the subsequent efficacy of epidural morphine.106 Some parturients who received 2-chloroprocaine as the primary local anesthetic agent for cesarean delivery have experienced unexpectedly poor postoperative analgesia (typically lasting < 4 hours).106,107 In contrast, Hess et al.108 observed no difference in pain scores, side effects, or the need for supplemental analgesics when epidural morphine 3 mg was given after epidural administration of preservative-free 3% 2-chloroprocaine or placebo; however, the epidural agents were administered 30 minutes after performance of a CSE technique that included intrathecal hyperbaric bupivacaine 11.25 mg and fentanyl 25 µg in women undergoing elective cesarean delivery. The occurrence of inadequate analgesia may therefore be related to the relatively rapid regression of 2-chloroprocaine anesthesia and the delay to peak effect of epidural morphine, rather than the postulated µ-opioid receptor antagonism of 2-chloroprocaine.106,108,109

Single-Dose Regimens to Optimize Postcesarean Analgesia and Minimize Opioid-Related Side Effects

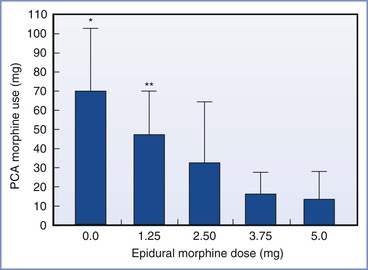

In a prospective dose-response study, Palmer et al.104 observed that postcesarean analgesia (assessed by need for supplemental intravenous morphine PCA) improved as the dose of epidural morphine increased from 0 to 3.75 mg. A further increase in dose (to 5 mg) did not significantly improve analgesia or reduce the amount of supplemental intravenous morphine used in the first 24 postoperative hours (Figure 28-3).104 Chumpathong et al.101 did not observe any difference in pain relief, patient satisfaction, or side effects in women receiving epidural morphine 2.5 mg, 3 mg, or 4 mg for postcesarean analgesia. Rosen et al.102 found that epidural morphine 5 mg and 7.5 mg provided similar analgesic efficacy, as opposed to a 2-mg dose, which provided ineffective analgesia. Epidural morphine 3 mg was recommended by Fuller et al.103 after a large retrospective study of epidural morphine in doses ranging from 2 to 5 mg for postcesarean analgesia.

FIGURE 28-3 Random allocation dose-response trial of epidural morphine 0, 1.25, 2.5, 3.75, and 5.0 mg for postcesarean delivery analgesia. Breakthrough pain as assessed by total 24-hour patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) morphine use. Data are mean ± 95% confidence interval. Groups were significantly different (P < .001). *Group 0.0 mg was significantly different from groups 2.5, 3.75, and 5.0 mg. **Group 1.25 mg was significantly different from groups 3.75 and 5.0 mg. (From Palmer CM, Nogami WM, Van Maren G, Alves DM. Postcesarean epidural morphine: a dose-response study. Anesth Analg 2000; 90:887-91.)

In contemporary clinical practice, doses of epidural morphine 2 to 4 mg are most commonly used. Lower doses may not provide effective analgesia, and women may require additional supplemental analgesia,102,104 whereas higher doses may increase opioid-related side effects without improving analgesia.

The long duration of epidural morphine analgesia prompts many clinicians to remove the epidural catheter after bolus administration. However, some investigators have proposed that the epidural catheter should be left in situ to allow administration of additional doses.110 Zakowski et al.110 reported that only 36% of patients who received two doses of epidural morphine 5 mg (at the time of delivery and at 24 hours postoperatively) required supplemental analgesics, compared with 76% of patients who received one dose of 5 mg at the time of delivery.

Epidural versus Intrathecal Administration

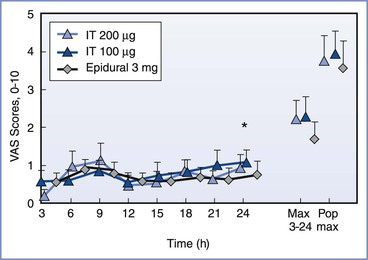

A number of studies have compared the postcesarean analgesic efficacy of epidural and intrathecal administration of opioids.14,111,112 Equipotent doses have been evaluated, with use of a conversion ratio of 20 : 1 to 30 : 1 between epidural and intrathecal administration. Sarvela et al.112 compared epidural morphine 3 mg with intrathecal morphine 0.1 mg and 0.2 mg; they found that the two routes of administration provided postcesarean analgesia with similar efficacy and equal duration (Figure 28-4). Duale et al.111 observed modest improvements in pain scores and less morphine consumption with epidural morphine 2 mg than with intrathecal morphine 0.075 mg. In both studies, the incidence of side effects (e.g., sedation, pruritus, nausea and vomiting) was not significantly different between the epidural and intrathecal routes of administration.111,112 No differences in postoperative pain scores, analgesic consumption, or treatment of side effects (e.g., nausea, vomiting, pruritus) were reported in a cohort of women who underwent scheduled cesarean delivery and received intrathecal morphine 0.2 mg, compared with a cohort who underwent intrapartum cesarean delivery and received epidural morphine 4 mg.113 A meta-analysis concluded that both epidural and intrathecal techniques provide effective postcesarean analgesia, with neither technique being superior in terms of analgesic efficacy.14 However, intrathecal administration results in less systemic drug exposure and less potential fetal drug exposure and may have a faster onset of action than epidural administration of morphine. Additionally, unintentional subdural or intrathecal administration of a dose intended for epidural administration can lead to profound sedation and respiratory depression, requiring opioid reversal and intensive care monitoring with possible ventilatory support.114 If a CSE anesthetic is planned, intrathecal administration of the opioid may be preferable.

FIGURE 28-4 Randomized trial of epidural morphine 3 mg, intrathecal (IT) morphine 100 µg (0.1 mg), and IT morphine 200 µg (0.2 mg). Visual analog scale (VAS) scores of postoperative pain during the first 24 hours at 3-hour intervals, as well as the maximal pain score at rest for each patient during the first 24 hours (Max 3-24) and the maximal pain score when moving (Pop max), expressed as means and 95% error bars in the three groups. *P < .05, epidural compared with both IT groups at 24 hours. (From Sarvela J, Halonen P, Soikkeli A, Korttila K. A double-blinded, randomized comparison of intrathecal and epidural morphine for elective cesarean delivery. Anesth Analg 2002; 95:436-40.)

Fentanyl

Fentanyl is not approved by the FDA for neuraxial administration, but it is very commonly administered “off label” for postcesarean analgesia. Commercial preparations of fentanyl contain no preservatives, are suitable for epidural or intrathecal administration, and have an excellent safety record. Grass et al.115 reported that the 50% and 95% effective doses (ED50 and ED95, respectively) of epidural fentanyl to reduce postcesarean pain scores to less than 10 mm (using a 100-mm visual analog scale) were 33 µg and 92 µg, respectively. Epidural fentanyl doses of 1 µg/kg have also been suggested to optimize intraoperative analgesia.116 In clinical practice, doses of 50 to 100 µg are given alone or in combination with epidural morphine. Adverse neonatal effects should be considered if fentanyl is administered before delivery. It may be prudent to delay fentanyl administration until the umbilical cord has been clamped if high doses (> 100 µg) are planned. Epidural fentanyl doses less than 50 µg do not provide optimal analgesia.117

The slow onset of action of morphine limits its ability to provide optimal intraoperative analgesia, and more lipophilic opioids (e.g., fentanyl) with a faster onset of analgesia are more appropriate for supplementation of intraoperative analgesia (see Table 28-2).98,118,119 Although single-dose epidural fentanyl improves intraoperative analgesia, no meaningful postoperative pain relief occurs beyond 4 hours.120 Naulty et al.121 reported that epidural fentanyl 50 to 100 µg provided 4 to 5 hours of pain relief and significantly reduced 24-hour analgesic requirements after cesarean delivery. However, Sevarino et al.122 reported an analgesic duration of only 90 minutes and no reduction in 24-hour opioid requirements in patients who received epidural fentanyl 100 µg with epidural lidocaine anesthesia for cesarean delivery. A dose-response study of epidural fentanyl 25, 50, 100, and 200 µg (with lidocaine and epinephrine) found that the duration of analgesia ranged from 1 to 2 hours.115 These discrepancies in the duration of analgesia can likely be attributed to the use of different local anesthetics in these studies. Bupivacaine has a long duration of action and may potentiate spinal opioid analgesia by altering opioid receptor conformation and facilitating opioid receptor binding.123,124 Prior epidural administration of 2-chloroprocaine may be associated with a short duration of epidural fentanyl analgesia. This effect does not appear to be a pH-dependent phenomenon; it may reflect µ-opioid receptor antagonism caused by 2-chloroprocaine.109

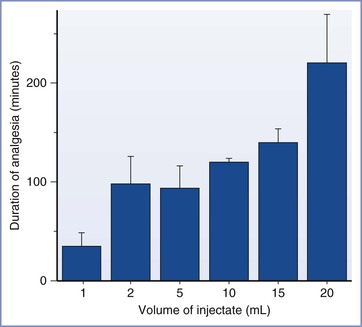

Lipophilic opioids do not spread rostrally in CSF to any great extent and tend to have limited dermatomal spread.80, 98 Birnbach et al.125 found that the onset and duration of analgesia provided by epidural fentanyl 50 µg could be improved by increasing the volume of normal saline in the epidural injectate (Figure 28-5); this finding contrasts to observations of epidural morphine (see earlier discussion).

FIGURE 28-5 Duration of postcesarean analgesia provided by epidural fentanyl 50 µg administered in different volumes of normal saline. P < .001, each group compared with the control group (1 mL). (Data from Birnbach DJ, Johnson MD, Arcario T, et al. Effect of diluent volume on analgesia produced by epidural fentanyl. Anesth Analg 1989; 68:808-10.)

Local anesthetics may have a synergistic effect with epidurally administered opioids. The concurrent administration of local anesthetic reduces epidural fentanyl dose requirements after cesarean delivery.126 Epidural fentanyl, administered either as a single dose or as a continuous or patient-controlled infusion, generally has fewer side effects than epidural morphine.83,121,122 Some investigators have suggested that the administration of epidural fentanyl before incision may provide preemptive analgesia that improves postoperative analgesia.116

Sufentanil

Epidural sufentanil is a lipid-soluble opioid that provides a rapid onset of effective postcesarean analgesia. In patients recovering from cesarean delivery, the potency ratio of epidural sufentanil to epidural fentanyl is approximately 5 : 1.115 No differences in onset, quality, or duration of analgesia were found after epidural administration of equi-analgesic doses of sufentanil and fentanyl.115 Like fentanyl, epidural sufentanil does not provide postoperative analgesia of significant duration. Rosen et al.127 compared postcesarean epidural morphine 5 mg with epidural sufentanil 30, 45, or 60 µg. Although most patients who received sufentanil reported pain relief within 15 minutes, the duration of analgesia was 4 to 5 hours, in contrast to the 26 hours of analgesia with epidural morphine.127 The duration of analgesia is dose dependent; an epidural bolus of sufentanil 25 µg produced less than 2 hours of analgesia, whereas 60 µg provided 5 hours of pain relief.115,127

The rapid onset and short duration of action of sufentanil are desirable characteristics for continuous epidural infusion. The vascular uptake of epidural sufentanil is significant, and plasma concentrations increase progressively after epidural administration. However, no data exist to establish dose limits for epidural sufentanil administration in this setting.

Meperidine

Epidural meperidine has been used for postcesarean analgesia and has local anesthetic properties. Two clinical trials compared the safety and efficacy of epidural meperidine 50 mg and intramuscular meperidine 100 mg administered to patients after cesarean delivery.128,129 Epidural meperidine provided a faster onset of analgesia with a duration (2 to 4 hours) similar to that provided by intramuscular meperidine. Paech130 evaluated the quality of analgesia and side effects produced by a single epidural bolus of meperidine 50 mg or fentanyl 100 µg. The onset of pain relief was slightly faster with fentanyl; however, the duration of analgesia was longer with meperidine. Ngan Kee et al.131,132 compared different doses of epidural meperidine (12.5, 25, 50, 75, and 100 mg) as well as varying volumes of diluent. The investigators concluded that meperidine 25 mg diluted in 5 mL of saline was superior to 12.5 mg and that doses greater than 50 mg offered no improvement in the quality or duration of analgesia. Epidural meperidine is not associated with marked hemodynamic effects, which are more commonly observed after intrathecal administration.133 Studies that have compared a single bolus dose of epidural or intrathecal morphine with PCEA meperidine have reported superior analgesia with morphine, but with a higher incidence of opioid-related side effects such as nausea, pruritus, and sedation.134,135 The potential for accumulation of the active metabolite normeperidine limits meperidine doses and duration of treatment in this setting.136

Other Epidural Opioids

Hydromorphone

Hydromorphone is a hydroxylated derivative of morphine with a lipid solubility intermediate between that of morphine and meperidine.137 The quality of epidural hydromorphone analgesia after cesarean delivery appears to be similar to that observed with epidural morphine; however, its onset is faster and its duration is slightly shorter.138-140 Evidence suggests a potency ratio of 3 : 1 to 5 : 1 between epidural morphine and epidural hydromorphone.137

Chestnut et al.140 evaluated postcesarean analgesia with epidural hydromorphone 1 mg. Most patients reported good or excellent pain relief, and the mean time to first request for supplemental analgesia was 13 hours. Dougherty et al.138 reported that epidural hydromorphone 1.5 mg provided 18 hours of postcesarean analgesia and could be prolonged to 24 hours with the addition of epinephrine. Henderson et al.139 observed 19 hours of postcesarean analgesia with epidural hydromorphone 1 mg. The incidence of pruritus was high in the two latter studies.138,139 Halpern et al.141 found no overall differences in quality of postcesarean analgesia or severity of side effects between patients who received either epidural hydromorphone 0.6 mg or epidural morphine 3 mg. Pruritus was more pronounced in the hydromorphone group in the first 6 hours; however, the incidence was higher in the morphine group at 18 hours. A Cochrane review suggests that epidural morphine and hydromorphone provide analgesia with similar efficacy and side effects when given for the treatment of acute or chronic pain.142

Diamorphine

Diamorphine is a lipid-soluble derivative of morphine that is commonly administered neuraxially in the United Kingdom.143 The lipid solubility of diamorphine provides rapid-onset analgesia, and its principal metabolite (morphine) facilitates a prolonged duration of analgesia. Epidural diamorphine 5 mg provides rapid onset and effective postcesarean analgesia.144,145 Roulson et al.146 found that epidural diamorphine 2.5 mg provided postcesarean analgesia for 16 hours. Other investigators have found the duration of postcesarean analgesia provided by epidural diamorphine to be 6 to 12 hours.144,145,147 In the United Kingdom, the National Institute of Clinical Excellence (NICE) suggests a dose of epidural diamorphine of 2.5 to 5 mg for postcesarean analgesia.148

Butorphanol

The mixed agonist-antagonist opioid butorphanol offers two theoretical advantages when administered epidurally: (1) modulation of visceral nociception due to selective κ-opioid receptor activity, and (2) a ceiling effect for respiratory depression even if opioid molecules spread rostrally to the brainstem.71 Unfortunately, significant sedation often occurs as a result of vascular uptake and activation of supraspinal κ-opioid receptors. Although epidural butorphanol 2 to 4 mg provides up to 8 hours of postcesarean analgesia,149,150 a dose-dependent increase in sedation occurs. Low doses (0.5 and 0.75 mg) of epidural butorphanol are not associated with significant sedation but provide modest analgesia after cesarean delivery compared with epidural bupivacaine alone.151 Camann et al.152 found that epidural butorphanol 2 mg offered few advantages over a similar dose given intravenously. In addition to excessive maternal somnolence, there is concern about the neurologic safety of epidural butorphanol, which is based on observations after repeated intrathecal injections in animals.153,154 Epidural butorphanol is not recommended for postcesarean analgesia because of its potential neurotoxicity, and it is not approved by the FDA for neuraxial use.

Nalbuphine

Nalbuphine is a semisynthetic opioid with higher lipid solubility than morphine. In vitro studies have shown that moderate agonist activity occurs at κ-opioid receptors, and antagonist activity occurs at µ-opioid receptors. In animal models, neuraxial nalbuphine provides effective analgesia. The rapid onset and intermediate duration of action of nalbuphine are consistent with its lipid solubility and rapid clearance.155 However, Camann et al.156 found that for doses ranging from 10 to 30 mg, epidural nalbuphine provided minimal analgesia and significant somnolence after cesarean delivery. The addition of nalbuphine 0.02 to 0.08 mg/mL to an epidural infusion of hydromorphone 0.075 mg/mL did not improve analgesia after cesarean delivery.157

Epidural Opioid Combinations

Theoretically, the epidural administration of a lipophilic opioid combined with morphine should provide analgesia of rapid onset and prolonged duration. The use of lipophilic opioids administered intrathecally (e.g., fentanyl 15 µg) or epidurally (e.g., fentanyl 100 µg in combination with epidural morphine 3.5 mg) improves analgesia and reduces nausea and vomiting during cesarean delivery.158,159 Some investigators have expressed concern that opioid interactions might reduce analgesic efficacy after epidural administration and that neuraxial fentanyl might initiate acute tolerance or affect the pharmacokinetic and receptor-binding characteristics of morphine. However, these concerns have not been confirmed in subsequent studies.159,160 Epidural fentanyl, administered immediately after delivery of the infant, improved the quality of intraoperative analgesia without worsening epidural morphine analgesia after cesarean delivery.159

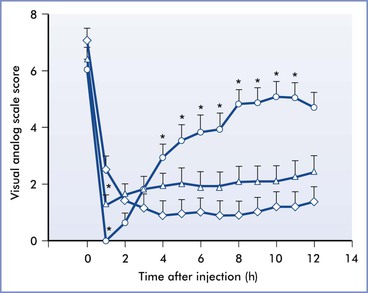

Dottrens et al.161 compared a single epidural dose of either morphine 4 mg, sufentanil 50 µg, or morphine 2 mg with sufentanil 25 µg. The addition of sufentanil to epidural morphine provided a more rapid onset and similar duration of postcesarean analgesia than morphine alone.161 Morphine alone or in combination with sufentanil provided analgesia of significantly longer duration than sufentanil alone (Figure 28-6). Sinatra et al.162 were unable to show any potentiation when epidural sufentanil 30 µg was added to morphine 3 mg, and the duration of this combination was shorter than that of epidural morphine 5 mg alone. The addition of a lipophilic opioid to epidural morphine is popular clinically and may improve intraoperative analgesia; however, the dose of morphine should not be reduced because postoperative analgesia may be compromised.

FIGURE 28-6 Randomized trial of epidural morphine 4 mg (⋄), sufentanil 50 µg (○), or the combination of morphine 2 mg and sufentanil 25 µg (△). Postcesarean delivery pain as measured by visual analog scale before and after epidural study drug administration. *P < .05 in comparison with time-matched data points for epidural morphine administration. (From Dottrens M, Rifat K, Morel DR. Comparison of extradural administration of sufentanil, morphine and sufentanil-morphine combination after caesarean section. Br J Anaesth 1992; 69:9-12.)

Studies that have evaluated the combination of butorphanol and morphine have provided conflicting results.163-165 Lawhorn et al.164 found that the combination of epidural morphine 4 mg and butorphanol 3 mg provided a duration of analgesia similar to that provided by epidural morphine alone. Wittels et al.163 noted that patients who received epidural butorphanol 3 mg with morphine 4 mg reported superior pain control, a lower incidence of pruritus, and greater satisfaction during the first 12 hours after cesarean delivery than patients who received morphine alone. In contrast, Gambling et al.165 observed no significant differences in pain, satisfaction, nausea, or pruritus when epidural butorphanol (1, 2, or 3 mg) was added to morphine 3 mg, and butorphanol administration resulted in significantly higher somnolence scores.

A low dose (5 mg) of epidural nalbuphine added to epidural morphine 4 mg has been found to reduce the severity of morphine-induced pruritus without affecting postcesarean analgesia; however, a 10-mg dose increased postoperative pain scores.166

Patient-Controlled Epidural Analgesia

The use of continuous epidural analgesia is a popular means of providing postoperative analgesia in patients undergoing thoracic or upper abdominal surgery. Improved analgesic outcomes have been reported in reviews of studies that compared epidural analgesia with intravenous PCA after nonobstetric surgery.6,17

Several studies have suggested that PCEA, using fentanyl and bupivacaine, provides better analgesia than CEI.167,168 Other potential advantages of PCEA over CEI are lower total doses of local anesthetic, fewer nursing and physician interventions, improved patient autonomy, and better patient satisfaction.169 A systematic review of studies comparing PCEA, CEI, and intravenous PCA suggested that CEI provides significantly better analgesia than PCEA in nonobstetric patients.17 However, marked heterogeneity among studies prevented definitive conclusions.

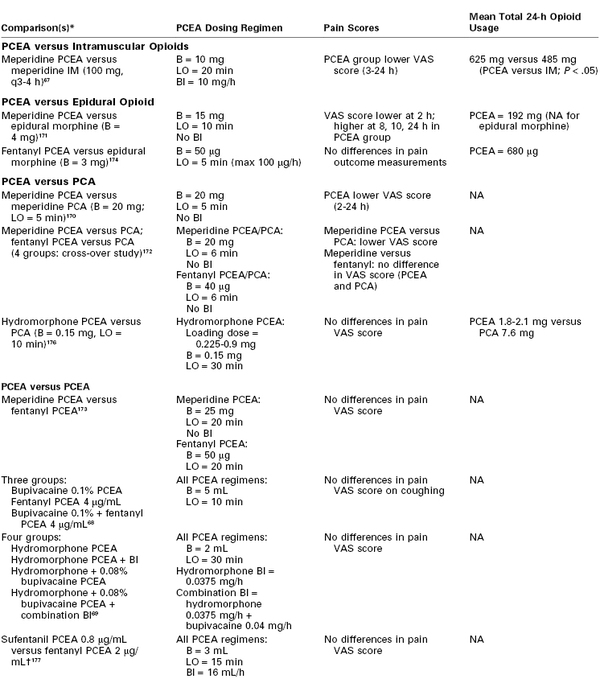

Epidural morphine has a prolonged latency; therefore the use of morphine for PCEA is not a viable option owing to the accompanying risk for delayed respiratory depression. Thus, more lipophilic drugs have been more widely evaluated for PCEA after cesarean delivery (Table 28-4).

TABLE 28-4

Comparative Studies Investigating Opioid-Containing, Patient-Controlled Epidural Analgesia (PCEA) Regimens for Postcesarean Analgesia

* Superscript numbers indicate chapter references.

† Both groups received 0.01% bupivacaine + epinephrine 0.5 µg/mL.

B, bolus; BI, background infusion; IM, intramuscular injection; LO, lockout interval; NA, data not available; PCA, intravenous patient-controlled analgesia; PCEA, patient-controlled epidural analgesia; VAS, visual analog scale.

Previous investigations have compared meperidine PCEA with other routes of parenteral administration (PCA, intramuscular). Yarnell et al.67 reported that PCEA meperidine provided better postcesarean analgesia than intermittent intramuscular meperidine. Patients receiving PCEA were also able to ambulate and nurse their infants earlier. Paech et al.170 performed a crossover study to compare PCEA with intravenous PCA meperidine for the first 24 hours after cesarean delivery; patients were randomly assigned to either PCEA or intravenous PCA for 12 hours before crossing over to the other route of drug administration for the next 12 hours. The PCEA and PCA meperidine protocols in this study were identical (20-mg bolus, 5-minute lockout). Patients receiving meperidine PCEA had lower pain scores at rest and with coughing than patients receiving intravenous PCA. Other studies have compared PCEA meperidine with other opioids for postcesarean analgesia. Fanshawe171 compared PCEA meperidine with single-dose epidural morphine. Postoperative pain scores were significantly lower with PCEA meperidine at 2 hours but were higher at 6, 8, and 24 hours. The investigators speculated that the variability in analgesic outcomes could have resulted from a suboptimal PCEA meperidine bolus dose of 15 mg. Studies have suggested that a meperidine bolus dose of 25 mg would be better suited for PCEA use (analgesic onset 12 minutes, median duration 165 minutes).132,136 Ngan Kee et al.172 and Goh et al.173 used different crossover study designs to investigate the analgesic effects of meperidine and fentanyl using intravenous PCA and PCEA modalities. Ngan Kee et al.172 observed that PCEA (fentanyl or meperidine) regimens were associated with lower pain scores compared with the respective PCA regimens. Goh et al.173 observed similar analgesic profiles among patients receiving fentanyl and meperidine PCEA, but noted more favorable side-effect profiles and better patient satisfaction among patients receiving meperidine PCEA.

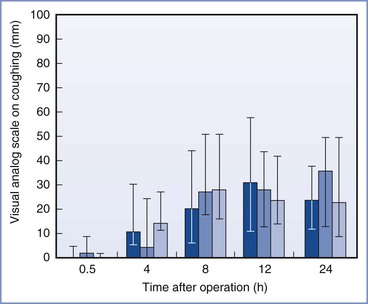

Fentanyl PCEA (50-µg bolus, 5-minute lockout, maximum dose 100 µg/h) has been shown to produce similar analgesia and less pruritus compared with epidural morphine 3 mg.174 Cooper et al.68 postulated that the combination of epidural fentanyl with local anesthetic (fentanyl 2 µg/mL with 0.05% bupivacaine) would provide better analgesia than that provided by a single-drug regimen (fentanyl 4 µg/mL or 0.1% bupivacaine PCEA). The combination-drug regimen was associated with lower pain scores at rest and significantly lower total drug requirements. However, no significant differences in pain scores during coughing were reported among the three groups (Figure 28-7). Matsota et al.175 compared PCEA with 0.15% ropivacaine, 0.15% levobupivacaine, and a 0.15% ropivacaine-fentanyl 2 µg/mL combination regimen for postcesarean analgesia. Administration of the ropivacaine-fentanyl combination resulted in higher patient satisfaction despite a lack of difference among groups in pain scores or local anesthetic consumption.

FIGURE 28-7 Randomized trial of postcesarean delivery patient-controlled epidural analgesia (PCEA) with fentanyl 4 µg/mL, 0.1% bupivacaine, or both fentanyl 2 µg/mL and 0.05% bupivacaine. Pain scores during coughing on a visual analog scale. Median score and interquartile range for groups who received epidural bupivacaine (dark blue bars), fentanyl (medium blue bars), and bupivacaine plus fentanyl (light blue bars). There were no differences in scores among the 3 groups. (From Cooper DW, Ryall DM, McHardy FE, et al. Patient-controlled extradural analgesia with bupivacaine, fentanyl, or a mixture of both, after caesarean section. Br J Anaesth 1996; 76:611-5.)

The efficacy of hydromorphone (single drug and combination) PCEA regimens after cesarean delivery has been investigated (see Table 28-4).69,157,176 Parker and White176 compared hydromorphone PCEA with intravenous PCA; no significant differences in pain scores were found between the two treatment groups. However, investigators found that patients who received hydromorphone PCEA received less opioid in the first 24 hours, had less pruritus, and reported a more rapid return of bowel function. In a follow-up study, these investigators assessed hydromorphone PCEA, with and without a background infusion, and hydromorphone combined with 0.08% bupivacaine, with and without a background infusion.69 No differences in pain scores, PCEA usage, or 24-hour PCEA requirements were noted, and the combination of hydromorphone-bupivacaine PCEA with a background infusion was associated with a greater degree of lower extremity numbness and weakness.

Parker et al.157 assessed how varying concentrations of epidural nalbuphine may alter the analgesic efficacy and side-effect profile of hydromorphone PCEA. The investigators found that higher doses of nalbuphine were associated with partial reversal of analgesia, more pruritus, less nausea, and decreased urinary retention.

PCEA with sufentanil has been evaluated for postcesarean analgesia.177,178 Cohen et al.177 compared fentanyl and sufentanil PCEA after cesarean delivery. The PCEA regimen in each group included 0.01% bupivacaine and epinephrine 0.5 µg/mL. Pain scores and side effects (nausea, pruritus, and sedation) were similar in the two groups; however, vomiting occurred more commonly in the sufentanil group. Vercauteren et al.178 compared sufentanil PCEA (bolus 5 µg, lockout 10 minutes) with an identical PCEA regimen accompanied by a background infusion of sufentanil 4 µg/h.178 Pain was significantly lower at 6 hours in the group receiving PCEA with a background infusion, but no other differences in analgesia were reported between 6 and 24 hours. The overall incidence and severity of sedation were higher in the background infusion group.

Integrating different epidural regimens (PCEA with CEI) may be beneficial in optimizing postoperative analgesia. In a study assessing analgesia after intra-abdominal surgery, patients receiving fentanyl PCEA with bupivacaine CEI reported pain scores similar to those in patients receiving a bupivacaine-fentanyl CEI; however, the total fentanyl requirements were lower in the PCEA group.179 Further work is necessary to evaluate PCEA regimens that optimize analgesic efficacy while maintaining adequate patient mobility and ambulation after surgery. It remains unclear whether a single drug or a combination PCEA drug regimen is preferable or whether a background infusion optimizes analgesia for patients receiving PCEA.

Although CEI or PCEA can provide satisfactory postoperative analgesia, these techniques diminish maternal mobility, increase costs, and potentially increase the risk for catheter-related complications (e.g., hematoma, infection) in comparison with single-dose administration of neuraxial morphine.180 In addition, epidural catheter movement commonly occurs with ambulation or patient movement and ultimately can result in ineffective postoperative analgesia.26 These disadvantages associated with epidural catheter–based techniques (CEI and PCEA) have limited their popularity for provision of postcesarean analgesia compared with the use of single-bolus doses of intrathecal or epidural morphine.13

Extended-Release Epidural Morphine

Extended-release epidural morphine (EREM) (DepoDur) is an FDA-approved drug that delivers standard morphine sulfate via DepoFoam (Pacira Pharmaceuticals, Inc., San Diego, CA). DepoFoam is a drug-delivery system composed of multivesicular lipid particles containing nonconcentric aqueous chambers that encapsulate the active drug.181,182 These naturally occurring lipids are broken down by erosion and reorganization, resulting in a sustained release of morphine for up to 48 hours after epidural administration of a single dose.182-184

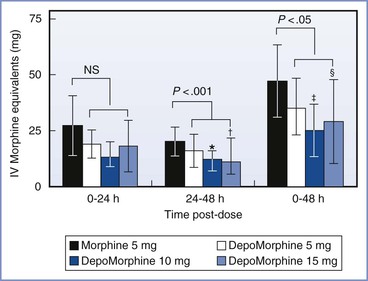

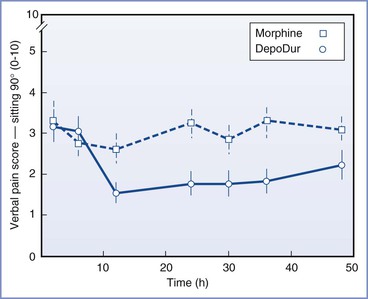

Two studies have evaluated the analgesic efficacy of EREM for postcesarean analgesia.57, 58 Both studies concluded that patients receiving EREM report lower pain scores and have lower requirements for supplemental analgesia over 48 hours than patients receiving standard epidural morphine.57,58 In the first study, overall supplemental opioid use was approximately 50% less in the EREM 10-mg and 15-mg groups than in the standard epidural morphine 5-mg group (Figure 28-8).57 A follow-up study, which allowed concurrent administration of an NSAID in both groups, compared a single dose of EREM 10 mg with standard epidural morphine 4 mg after cesarean delivery. The investigators found that analgesic consumption was 60% less in women in the EREM group than in women in the standard epidural morphine group.58 Patients who received EREM also had better and more prolonged pain control both at rest and with movement (Figure 28-9). A retrospective study of patients undergoing knee and hip arthroplasty found that EREM resulted in similar levels of pain control, improved ambulation, but more respiratory depression and nausea, compared with a CEI of 0.1% bupivacaine with morphine 40 µg/mL.185 In the two postcesarean studies, there was no significant difference in the incidence of nausea, pruritus, or sedation between the EREM and standard epidural morphine groups, and no respiratory depression or hypoxic events were observed.57,58 However, it is likely that the study groups were too small for accurate evaluation of side-effect profiles. Pooled data from EREM studies for nonobstetric surgery suggest that EREM is associated with more side effects than standard epidural morphine, especially with higher doses.182,186 A meta-analysis found that EREM was associated with a significantly higher risk for respiratory depression compared with intravenous opioid PCA (odds ratio [OR], 5.8; 95% CI, 1.1 to 31.9; P = .04).187 Further research is needed to assess the side-effect and safety profile of EREM in obstetric patients.

FIGURE 28-8 Randomized trial of single-shot epidural morphine compared with extended-release epidural morphine (EREM). Use of supplemental opioid analgesics (in morphine mg-equivalents) during the 48 hours after the study dose (DepoMorphine is EREM). IV, intravenous. *P = .0134; †P = .0001; †P = .0108; §P = .0065. (Modified from Carvalho B, Riley E, Cohen SE, et al. Single-dose, sustained-release epidural morphine in the management of postoperative pain after elective cesarean delivery: results of a multicenter randomized controlled study. Anesth Analg 2005; 100:1150-8.)

FIGURE 28-9 Randomized trial of single-shot epidural morphine 4 mg and extended-release epidural morphine (EREM) 10 mg for postcesarean analgesia. Pain intensity over time (verbal rating scale for pain [VRSP] 0-10) during activity (sitting up 90 degrees) plotted as means with standard deviations. P = .003 for EREM (DepoDur) group versus the conventional morphine group. (From Carvalho B, Roland LM, Chu LF, et al. Single-dose, extended-release epidural morphine (DepoDur) compared to conventional epidural morphine for postcesarean pain. Anesth Analg 2007; 105:176-83.)

When EREM is given correctly in the epidural space, monitoring for respiratory depression should be continued for 48 hours (compared with 24 hours with standard epidural morphine).188 Unintentional intrathecal EREM administration has the potential to result in profound and prolonged opioid-related side effects; however, a case report of unintentional intrathecal administration of a standard dose of EREM did not result in profound side effects or respiratory depression.189 Although single-dose EREM may reduce the need for additional doses of opioid, more prolonged monitoring is necessary, which may increase the required level of nursing care in the postoperative period.190

Currently, there is insufficient clinical evidence to advocate a change in the planned anesthetic technique (from a spinal to an epidural or CSE technique) solely for the purpose of EREM administration in patients undergoing cesarean delivery. However, many clinicians already use CSE techniques for elective cesarean delivery in selected patients (when the duration of the cesarean delivery is expected to extend beyond that provided by spinal anesthesia). In addition, many cesarean deliveries are performed in women in whom an epidural catheter has been placed previously during labor. Therefore, it is possible that EREM may be an attractive option for clinicians who plan to use or insert an epidural catheter for cesarean delivery. However, caution should be exercised when the administration of EREM follows the use of any epidural local anesthetic. Early pharmacokinetic studies suggested a potential physicochemical interaction between EREM and epidural local anesthetics, which could negate the sustained-release effect derived from the DepoFoam. A 2011 study found that epidural lidocaine administration (20 to 35 mL) for cesarean delivery, administered 1 hour before EREM administration, increased peak venous blood morphine levels and increased the incidence of vomiting, use of supplemental oxygen, and hypotension, compared with a control group who did not receive epidural lidocaine.191 However, Gambling et al.192 demonstrated no differences in the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profiles of EREM when administered 15, 30, and 60 minutes after epidural bupivacaine 0.25%. The package insert advises: “Local anesthetics other than a 3-mL test dose of lidocaine are not permitted. If the 3-mL test dose is used, wait 15 minutes and then flush the epidural catheter with 1 mL of saline before administration of EREM.”193

In summary, EREM provides effective postoperative pain relief and reduces the need for supplemental analgesics in comparison with standard epidural morphine for up to 48 hours after cesarean delivery.57,58 This analgesic advantage must be weighed against potential disadvantages associated with EREM administration. The role of EREM for postcesarean analgesia remains unclear186; however, selective use may be beneficial in a subset of patients with significant analgesic needs. In such cases, a single dose of EREM 6 to 10 mg is recommended after the infant is delivered (and the umbilical cord is clamped), as an alternative to standard epidural morphine.

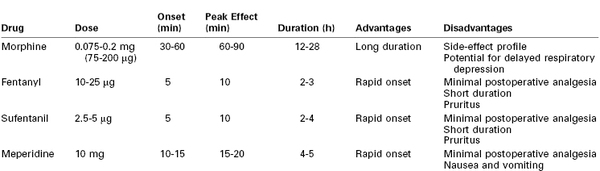

Intrathecal Opioids

Spinal anesthesia has become the preferred anesthetic technique for patients undergoing elective cesarean delivery in the United States and the United Kingdom.11-13 Intrathecal opioids are commonly administered with a local anesthetic to improve intraoperative and postoperative analgesia (Table 28-5).

Morphine

The potency differences between intrathecal and epidural opioids account for the smaller doses of intrathecal opioid used for cesarean delivery. Intrathecal morphine 0.075 to 0.2 mg has been found to be equivalent to epidural morphine 2 to 3 mg.111,112 Initial reports of increased side effects with intrathecal administration likely resulted from the use of very high doses (2 to 10 mg). The analgesic efficacy, duration of action, and side-effect profile of intrathecal morphine are similar to that of epidural morphine in patients undergoing cesarean delivery (see earlier discussion).111,112,194

Onset and Duration

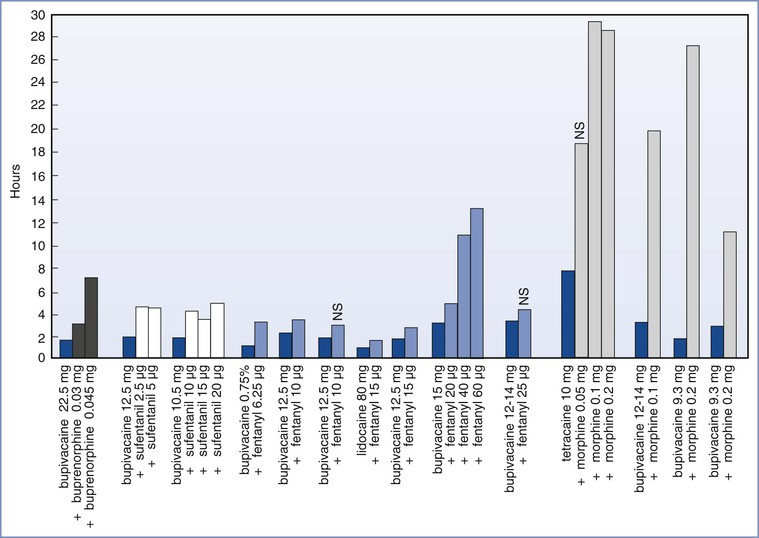

Intrathecal morphine administration may result in a faster onset of analgesia than epidural morphine, but 45 to 60 minutes are still required for the drug to achieve a peak effect. The duration of analgesia is similar to the duration after epidural administration (14 to 36 hours).* A systematic review and meta-analysis found that the median time to first analgesic request was 27 hours (range, 11 to 29 hours) after intrathecal morphine administration for postcesarean analgesia (Figure 28-10).51 A meta-analysis of studies of intrathecal opioid administration in adults undergoing orthopedic, urologic, gynecologic, or general surgical procedures reported that intrathecal morphine (0.05 to 2 mg) provided postoperative analgesia with a mean duration of 503 minutes (95% CI, 315 to 641).198 The duration of analgesia may be dose dependent.51,195Abboud et al.195 observed that postcesarean analgesia increased from 19 hours to 28 hours with intrathecal morphine 0.1 mg and 0.25 mg, respectively.

FIGURE 28-10 Systematic review of intrathecal opioid analgesia for post–cesarean delivery analgesia. Time to first administration (in hours) of postoperative supplemental analgesics in patients receiving spinal anesthesia with local anesthetic alone (dark blue bars) or local anesthetic combined with buprenorphine, sufentanil, fentanyl, or morphine in varying doses (various bars). NS, no significant difference from control. (From Dahl JB, Jeppesen IS, Jorgensen H, et al. Intraoperative and postoperative analgesic efficacy and adverse effects of intrathecal opioids in patients undergoing cesarean section with spinal anesthesia. Anesthesiology 1999; 91:1919-27.)

Optimal Dosage

Several studies have attempted to determine the optimal dose of intrathecal morphine for postcesarean analgesia. Palmer et al.199 compared postcesarean intravenous PCA morphine use after doses of intrathecal morphine ranging from 0.025 to 0.5 mg. The investigators found no significant difference in PCA morphine use with morphine doses greater than 0.075 mg.199 They concluded that there was little justification for using a dose of intrathecal morphine higher than 0.1 mg for postcesarean analgesia. Milner et al.200 noted that intrathecal morphine 0.1 mg and 0.2 mg produced comparable analgesia but that the lower dose led to less nausea and vomiting. Yang et al.201 showed that intrathecal morphine 0.1 mg provided similar postcesarean analgesia with fewer side effects in comparison with 0.25 mg. Uchiyama et al.202 performed a dose-response study with intrathecal morphine 0, 0.05, 0.1, and 0.2 mg. They observed that 0.1 mg and 0.2 mg provided comparable and effective postcesarean analgesia for 28 hours. The 0.05-mg dose was less effective, and the incidence of side effects was greater with the 0.2-mg dose; therefore, the investigators concluded that intrathecal morphine 0.1 mg is the optimal dose for postcesarean analgesia.202 A recent retrospective study reported that intrathecal morphine 0.2 mg provided better analgesia than 0.1 mg but with the “trade-off” of increased nausea.203 Girgin et al.204 reported no differences in analgesia with intrathecal morphine doses ranging from 0.1 to 0.4 mg; however, pruritus was increased with higher morphine doses. A systematic review recommended 0.1 mg as the intrathecal morphine dose of choice.51

Several studies have compared the analgesic efficacy and side-effect profile of intrathecal morphine with those of PCEA after cesarean delivery. A study comparing intrathecal morphine 0.15 mg with PCEA with 0.06% bupivacaine and sufentanil 1 µg/mL found superior analgesia and fewer side effects with the PCEA regimen.180 Paech et al.135 compared intrathecal morphine 0.2 mg with PCEA meperidine for postcesarean analgesia. Patients in the morphine group reported lower pain scores but also had a higher incidence of pruritus, nausea, and drowsiness. In a study of intrathecal morphine (0, 0.05 and 0.1 mg) followed by a CEI (0.2% ropivacaine at 6 mL/h), intrathecal morphine improved postcesarean analgesia compared with placebo.205

In summary, the intrathecal administration of a small dose of morphine (0.075 to 0.2 mg) provides effective analgesia for 14 to 36 hours after cesarean delivery. Larger doses may increase side effects without conferring additional analgesic benefit. Because of the variability in patient response to intrathecal morphine, some patients may experience inadequate postoperative analgesia and/or opioid-related side effects. Thus, the use of low-dose intrathecal morphine as a component of multimodal analgesia may provide optimal analgesia with a low risk for side effects (see Chapter 27).

Fentanyl

Intrathecal fentanyl improves intraoperative analgesia (especially during uterine exteriorization), reduces intraoperative nausea and vomiting, decreases local anesthetic dose requirement, and provides a better postoperative transition to other pain medications during recovery from spinal anesthesia for cesarean delivery.206-209 However, intrathecal fentanyl provides a limited duration of postcesarean analgesia, with a median time to first request for additional analgesia of 4 hours (range, 2 to 13 hours) (see Figure 28-10).51 The aforementioned meta-analysis of studies of intrathecal opioid administration in adults undergoing nonobstetric surgery reported that intrathecal fentanyl (10 to 50 µg) provided postoperative analgesia with a mean duration of 114 minutes (95% CI, 60 to 168).198 A study that compared intrathecal morphine 0.1 mg with fentanyl 25 µg found that morphine provided better and longer postoperative analgesia after cesarean delivery.210

The analgesic effects, duration of analgesia, and side effects after intrathecal fentanyl are dose related.51,206,207 Belzarena et al.206 found that intrathecal fentanyl provided analgesia for a duration of 305 to 787 minutes (with 0.25 µg/kg and 0.75 µg/kg, respectively). However, patients who received the higher dose experienced decreased respiratory rates and a high incidence of side effects (e.g., pruritus, nausea). Dahlgren et al.207 reported that intrathecal fentanyl 10 µg added to bupivacaine increased the mean time of effective analgesia from 121 minutes to 181 minutes. Hunt et al.211 compared a range of intrathecal fentanyl doses (2.5 to 50 µg) in combination with intrathecal bupivacaine for cesarean delivery. Intrathecal fentanyl doses larger than 6.25 µg were associated with better intraoperative analgesia and a longer time to first request for additional analgesia than administration of bupivacaine alone (72 minutes versus 192 minutes, respectively).211 Chu et al.212 found that fentanyl doses of 12.5 to 15 µg were required to increase the duration of effective analgesia.

In summary, intrathecal fentanyl optimizes intraoperative analgesia and provides immediate postoperative analgesia. However, intrathecal fentanyl (10 to 25 µg) provides a limited duration of postcesarean analgesia (2 to 4 hours) and does not decrease subsequent postoperative analgesic requirements.

Sufentanil

Sufentanil has a fast onset of action, which may improve intraoperative analgesia and reduce the dose of local anesthetic required for cesarean anesthesia.213 However, its pharmacokinetic properties limit the duration of effective postcesarean analgesia after intrathecal administration.51 Courtney et al.214 found that intrathecal sufentanil 10, 15, or 20 µg resulted in a mean duration of postcesarean analgesia of approximately 3 hours. More than 90% of patients reported pruritus, but only one patient required treatment. Dahlgren et al.207 compared the safety and efficacy of the co-administration of sufentanil 2.5 or 5 µg, fentanyl 10 µg, or placebo with hyperbaric bupivacaine 12.5 mg for cesarean delivery. The duration of effective analgesia was longer with the opioids, particularly in the sufentanil groups; sufentanil 5 µg provided the longest duration of analgesia but also had the highest incidence of pruritus. Patients receiving intrathecal sufentanil had lower requirements for intraoperative antiemetics and postoperative intravenous morphine.207 A study that compared intrathecal sufentanil 2.5, 5.0, and 7.5 µg found that 5.0 and 7.5 µg provided more effective postcesarean analgesia than was observed in a control group (no intrathecal opioids); however, the incidence of pruritus was higher with sufentanil, especially with the 7.5-µg dose.215 Karaman et al.216 found that intrathecal sufentanil 5 µg delayed the time to first analgesic request to 6 hours, compared with 20 hours for intrathecal morphine 0.2 mg. A study that compared intrathecal ropivacaine 15 mg to ropivacaine 10 mg with sufentanil 5 µg showed that sufentanil provided effective analgesia with a mean duration of only 260 minutes. However, women in the sufentanil group had less intraoperative hypotension, shivering, and vomiting, as well as a shorter duration of motor blockade.217 A study that compared intrathecal fentanyl 20 µg and sufentanil 2.5 µg added to bupivacaine for cesarean delivery found no difference in the quality of intraoperative and postoperative analgesia, as well as no difference in the frequency of nausea and pruritus between the two opioid groups.218

Other Intrathecal Opioids

Meperidine

Intrathecal meperidine reduces the intensity of pain associated with the regression of spinal anesthesia and provides postoperative analgesia of intermediate duration (4 to 5 hours).219,220 Yu et al.221 found that the addition of meperidine 10 mg to hyperbaric bupivacaine 10 mg prolonged the mean duration of postcesarean analgesia (234 minutes in the meperidine group versus 125 minutes in a placebo group). However, the incidence of intraoperative nausea and vomiting was greater in the meperidine group. A dose of 7.5 mg added to bupivacaine 10 mg provided postoperative analgesia for 257 ± 112 minutes (mean ± SD) compared with a saline group (161 ± 65 min).222

Unlike other opioids, meperidine possesses local anesthetic qualities. Some anesthesia providers have administered intrathecal 5% meperidine (1 mg/kg) as the sole anesthetic agent for cesarean delivery under spinal anesthesia. However, surgical anesthesia was unreliable, with a mean anesthetic duration of 41 ± 15 minutes.219,220

Diamorphine

Diamorphine has physicochemical properties that are of value in providing intrathecal analgesia. A high lipophilicity (octanol-water coefficient = 280) results in a rapid onset of analgesia, and diamorphine's active metabolite (morphine) provides a prolonged duration of analgesia.

Kelly et al.223 compared intrathecal diamorphine 0.125, 0.25, and 0.375 mg for cesarean delivery. The 0.25-mg and 0.375-mg doses provided effective postcesarean analgesia; the incidence of both vomiting and pruritus was dose related. Stacey et al.224 reported that the duration of analgesia was dose dependent and found that intrathecal diamorphine 1 mg provided 10 hours of postcesarean analgesia, compared with 7 hours for 0.5 mg. The rapid onset of diamorphine is a potential advantage in the provision of intraoperative as well as postoperative analgesia.225,226 Saravanan et al.227 concluded that the ED95 for intrathecal diamorphine to prevent intraoperative discomfort was 0.4 mg. A dose-response study using intrathecal diamorphine 0.1, 0.2, or 0.3 mg reported a dose-dependent enhancement of analgesia and an increase in pruritus.9

Husaini et al.228 observed that intrathecal diamorphine 0.2 mg and intrathecal morphine 0.2 mg provided similar postcesarean analgesia as measured by postoperative intravenous PCA morphine requirements. However, the patients who received intrathecal morphine had a higher incidence of pruritus and drowsiness. Hallworth et al.229 reported that intrathecal diamorphine 0.25 mg produced the same duration and quality of postcesarean analgesia as did epidural diamorphine 5 mg, with less nausea and vomiting.

Diamorphine has been commonly used in the United Kingdom, but it is not available for clinical use in the United States. In the United Kingdom, the National Institute of Clinical Excellence suggests an intrathecal diamorphine dose of 0.3 to 0.4 mg for postcesarean analgesia.148

Nalbuphine

Culebras et al.230 compared intrathecal morphine 0.2 mg with intrathecal nalbuphine (0.2, 0.8, or 1.6 mg) for postcesarean analgesia. Intrathecal nalbuphine 0.8 mg provided good intraoperative and early postoperative analgesia without side effects. However, intrathecal morphine provided significantly longer postoperative analgesia. In an accompanying editorial, the study was criticized because the safety and neurotoxicity of nalbuphine had not been adequately assessed.155

Intrathecal Opioid Combinations

Intrathecal administration of morphine in combination with a lipophilic opioid (e.g., fentanyl, sufentanil) may offer some advantages. Intrathecal morphine has a delayed onset, and therefore lipophilic opioids with a rapid onset may improve intraoperative analgesia and reduce the intensity of pain associated with the regression of spinal anesthesia in the postanesthesia care unit after surgery. Chung et al.231 found that the combination of intrathecal meperidine 10 mg and morphine 0.15 mg provided better intraoperative analgesia, less need for supplemental analgesia, and higher satisfaction than intrathecal morphine alone for cesarean delivery. Intrathecal sufentanil 5 µg co-administrated with morphine 0.15 mg provided better and longer pain relief than intrathecal sufentanil plus a single injection of subcutaneous morphine; however, a higher incidence of side effects, such as nausea and vomiting, was observed with intrathecal morphine.232

Some investigators have suggested that intrathecal morphine may be less effective when concurrently administered with intrathecal fentanyl.233 Cooper et al.233 reported that patients who received intrathecal fentanyl 25 µg with bupivacaine had higher postoperative intravenous morphine PCA requirements than patients who received bupivacaine alone. The investigators postulated that this phenomenon was due to acute spinal opioid tolerance. Carvalho et al.234 found no difference in postoperative analgesia requirement but small differences in pain scores with the addition of increasing doses of intrathecal fentanyl (5, 10, or 25 µg) to intrathecal morphine 0.2 mg for cesarean delivery. The authors suggested that intrathecal fentanyl may induce subtle acute tolerance to intrathecal morphine. However, the clinical significance of this finding is unclear, especially in light of the intraoperative benefit of using intrathecal fentanyl. Sibilla et al.197 found that the intrathecal combination of fentanyl 25 µg with morphine 0.1 mg provided similar postoperative analgesia to that provided by intrathecal morphine alone. Many anesthesia providers currently administer both intrathecal morphine and fentanyl when giving spinal anesthesia for cesarean delivery.13 The co-administration of intrathecal fentanyl does not appear to significantly compromise the postoperative analgesia provided by intrathecal morphine.

Multimodal Analgesia

Despite the appropriate administration of neuraxial techniques, the quality and duration of analgesia after cesarean delivery is often incomplete. Thus, neuraxial opioids are rarely the sole analgesic technique used for postcesarean analgesia. Rather, neuraxial opioids should be considered as part of a multimodal analgesic approach for the treatment of postcesarean pain.25,26,59 Multimodal strategies (with neuraxial opioid and postoperative NSAID and acetaminophen administration) optimize analgesia and reduce analgesic requirements and side effects (see Chapter 27).

Maternal Safety and Neonatal Effects

Careful evaluation of the potential adverse effects of neuraxial pharmacologic agents is necessary before clinical administration of these agents.235 In obstetric patients, adverse maternal effects (e.g., neurotoxicity, altered uteroplacental perfusion) as well as potential adverse neonatal effects should be assessed. Although many agents are used routinely and safely in clinical practice, not all are licensed for neuraxial administration in the United States.

Maternal Safety