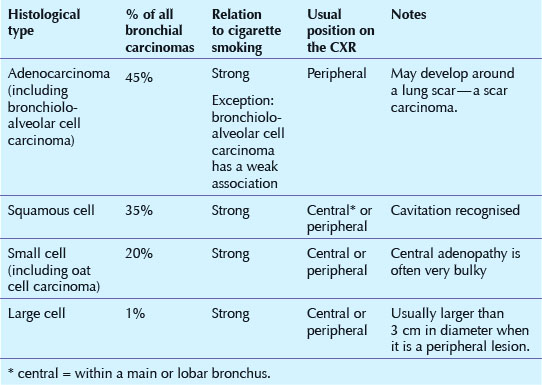

10 BRONCHIAL CARCINOMA

Every patient with an ominous symptom (e.g. smoker with recurrent haemoptysis) or with a less alarming symptom (e.g. a persistent cough in a man aged 65 years)—is thinking:

CXR: MISSED LUNG CANCERS—IMPORTANT MESSAGES

A carcinoma can be overlooked on the CXR because a superimposed structure (rib or vessel) makes it less conspicuous. This occurred in 71% of overlooked lesions in one series2.

A carcinoma can be overlooked on the CXR because a superimposed structure (rib or vessel) makes it less conspicuous. This occurred in 71% of overlooked lesions in one series2.

OBVIOUS CXR ABNORMALITY

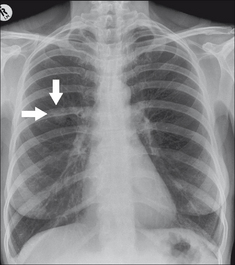

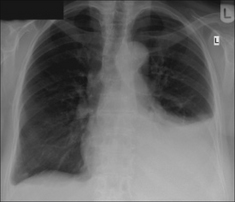

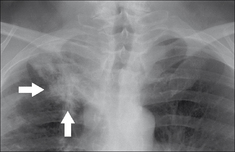

Many bronchial carcinomas are easy to detect—usually as a conspicuous mass peripherally or at a hilum (Figs 10.1-10.4).

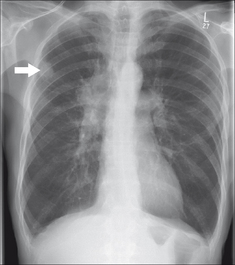

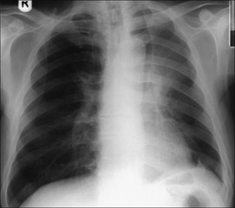

Figure 10.1 Lung opacity (arrow) with an irregular outline. Enlarged right hilum. Peripheral bronchial carcinoma with metastatic spread to the hilar lymph nodes.

SUBTLE CXR ABNORMALITY

TUMOURS WILL HIDE

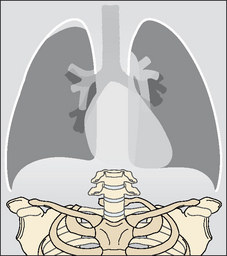

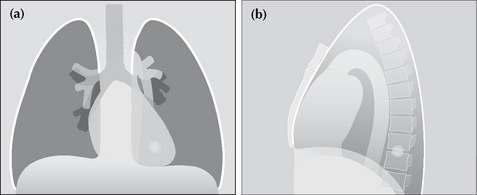

Some carcinomas are difficult to detect because of their position or because they are overlapped by normal structures (Figs 10.5, 10.7 and 10.8). To locate a hidden mass you need to inspect four areas very carefully:

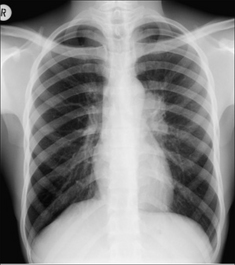

Figure 10.5 A small nodule is situated in the left lower lobe. On the frontal projection it will be overlooked unless: (a) correct windowing is carried out; and (b) this “behind the heart” area is looked at very carefully.

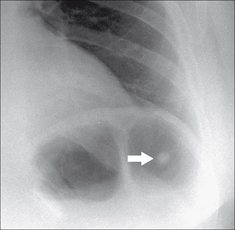

Figure 10.7 The right apical lesion (arrows) should not be dismissed as benign apical pleural thickening or fibrosis. It is a bronchial carcinoma. The overlying ribs are partially obscuring the tumour.

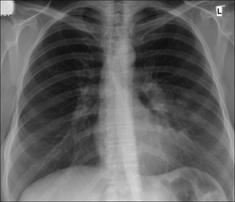

Figure 10.8 A peripheral nodule (arrow) is situated below the horizon of the left dome of the diaphragm. Bronchial carcinoma.

Make sure that the density of the heart on both sides of the spine is equal. Anything other than a very slight difference in density should raise the possibility of a lower lobe lesion/mass.

Some tumours begin as flat lesions and the CXR appearance may be dismissed as simple pleural thickening (Fig. 10.7). Overlap by the first and second ribs may compound the problem. A flat apical carcinoma can mimic a pleural cap (see box below and p. 230).

A large part of each lower lobe lies below the horizon of each dome of the diaphragm. Even so, if a lung mass is surrounded by air, then it is usually detectable on the frontal CXR (Fig. 10.8).

This does not refer to hilar enlargement. It refers to the lung parenchyma around, behind and in front of a hilum. Overlap by vessels entering or leaving the hilum can cause a nearby lung lesion to be overlooked.

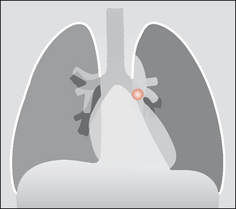

CENTRAL TUMOUR—NO LOBAR COLLAPSE

A tumour within a main bronchus which has not caused lobar collapse can be difficult to detect. Abnormal features may be subtle. Keep your eyes peeled for a dense hilum and/or an enlarged hilum.

CENTRAL TUMOUR—WITH LOBAR COLLAPSE

Paradoxically, complete collapse of a lobe can often be more difficult to detect than partial collapse (see Fig. 10.10). The features indicating lobar collapse are described in detail in Chapter 5, pp. 52–69.

PERIPHERAL TUMOUR—WITH DISTAL CONSOLIDATION

Sometimes a carcinoma well away from the hilum will obstruct the distal airways. This can result in an area of consolidation merging with the tumour mass, making the overall appearance indistinguishable from a simple pneumonia (Fig. 10.11).

Figure 10.11 Consolidation in a lingular segment of the left upper lobe. A central tumour is the underlying cause in this patient.

The clinical presentation will often help to distinguish between the patient with a simple infection and the patient who may be harbouring an underlying carcinoma. It is the overall clinical picture which dictates the next steps(Table 10.2).

Table 10.2 Peripheral consolidation on the CXR — the next steps.

| Clinical presentation/impression | Recommended action |

|---|---|

| Simple community acquired infection | Treat as for infection. No need for a repeat CXR unless some other adverse feature is present. |

| Simple infection unlikely | Sputum cytology and bronchoscopy and/or CT |

| Indeterminate clinical features |

PERIPLEURAL TUMOUR—WITH A PLEURAL EFFUSION

A primary tumour may infiltrate the adjacent pleura and cause an effusion. The effusion can easily hide the carcinoma (Fig. 10.12).

EXTENSIVE NODAL DISEASE

Small cell carcinoma of the bronchus often presents with extensive mediastinal lymph node enlargement. Although the disease may be extensive it is possible for any mediastinal alteration on the CXR to be subtle. It is important not only to check that the mediastinal contour appears anatomical but also to check that no variation in density is present.

Figure 10.9 A central tumour has obstructed the left main bronchus and caused collapse of the upper lobe. This classic, albeit peculiar, appearance is described in detail on pp. 65–66.

BEWARE—ONE CANCER IS THE GREAT IMPERSONATOR5

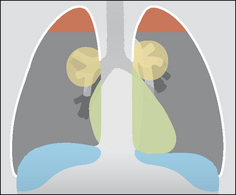

Bronchioloalveolar cell carcinoma (approximately 1–7% of all primary bronchial carcinomas) can adopt various disguises (Figs 10.13-10.15).

Most commonly it appears as a peripheral mass or nodule which is indistinguishable from any of the other primary carcinomas. The mass or nodule may cavitate.

Most commonly it appears as a peripheral mass or nodule which is indistinguishable from any of the other primary carcinomas. The mass or nodule may cavitate. Occasionally the CXR appearance mimics alveolar disease…similar to a pneumonia. The alveolar shadowing may extend to involve several lobes. An air bronchogram may also occur (see p. 227). A non-resolving pneumonia that is clinically puzzling should raise a warning flag: the pneumonic appearance might be tumour tissue—a bronchioloalveolar cell carcinoma.

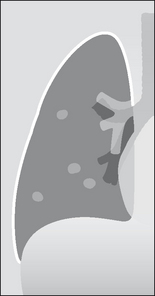

Occasionally the CXR appearance mimics alveolar disease…similar to a pneumonia. The alveolar shadowing may extend to involve several lobes. An air bronchogram may also occur (see p. 227). A non-resolving pneumonia that is clinically puzzling should raise a warning flag: the pneumonic appearance might be tumour tissue—a bronchioloalveolar cell carcinoma. Very occasionally it is multicentric, presenting as multiple discrete pulmonary nodules mimicking metastatic disease.

Very occasionally it is multicentric, presenting as multiple discrete pulmonary nodules mimicking metastatic disease.

Figure 10.13 Bronchiolo-alveolar cell carcinoma. The most common CXR finding—a peripheral solitary lung lesion.

Figure 10.14 Bronchiolo-alveolar cell carcinoma. An occasional CXR appearance—lobar consolidation mimicking a pneumonia.

Figure 10.15 Bronchiolo-alveolar cell carcinoma. Yet another CXR appearance: multiple discrete pulmonary nodules.

Cavitation

15% of peripheral primary carcinomas cavitate. Most of these are squamouscell carcinomas.

Golden’s S sign

A collapsed right upper lobe with a mass at the hilum results in a reverse S configuration. The reversed S is made up of an elevated horizontal fissure and a bulky tumour at the hilum. See p. 64.

Asbestos related bronchial carcinoma6

The relative risk of developing a bronchial carcinoma in non-smoking asbestos workers varies in different series (1.4 to 4 times the risk as compared with non-smokers not exposed to asbestos).

The relative risk of developing a bronchial carcinoma in non-smoking asbestos workers varies in different series (1.4 to 4 times the risk as compared with non-smokers not exposed to asbestos). Asbestos exposure and cigarette smoking have a synergistic effect—increasing the risk of developing a bronchial carcinoma. The risk is as high as 100 times greater than for non-smokers with no asbestos exposure.

Asbestos exposure and cigarette smoking have a synergistic effect—increasing the risk of developing a bronchial carcinoma. The risk is as high as 100 times greater than for non-smokers with no asbestos exposure.1. Kaneko M, Eguchi K, Ohmatsu H, et al. Peripheral lung cancer: screening and detection with low-dose spiral CT versus radiography. Radiology. 1996;201:798-802.

2. Lorentz GBA, Quekel MD, Kessels AGH, et al. Miss rate of lung cancer on the chest radiograph in clinical practice. Chest. 1999;115:720-724.

3. O’Connell RS, McLoud TC, Wilkins EW. Superior sulcus tumor: radiographic diagnosis and workup. AJR. 1983;140:25-30.

4. Renner RR, Pernice NJ. The apical cap. Semin Roentgenol. 1977;12:299-302.

5. Epstein DM. Bronchioloalveolar carcinoma. Semin Roentgenol. 1990;25:105-111.

6. Aronchick JM. Lung cancer: Epidemiology and Risk Factors. Semin Roentgenol. 1990;25:5-11.