Chapter 368 Congenital Disorders of the Nose

Normal Newborn Nose

Children and adults preferentially breathe through their nose unless nasal obstruction interferes. Most newborn infants are obligate nasal breathers and significant nasal obstruction presenting at birth, such as choanal atresia, may be a life-threatening situation for the infant unless an alternative to the nasal airway is established. Nasal congestion with obstruction is common in the 1st year of life and can affect the quality of breathing during sleep; it may be associated with a narrow nasal airway, viral or bacterial infection, enlarged adenoids, or maternal estrogenic stimuli similar to rhinitis of pregnancy. The internal nasal airway doubles in size in the 1st 6 mo of life, leading to resolution of symptoms in many infants. Supportive care with a bulb syringe and saline nose drops, topical nasal decongestants, and antibiotics, when indicated, improve symptoms in affected infants.

Physiology

The nose is responsible for olfaction and initial warming and humidification of inspired air. In the anterior nasal cavity, turbulent airflow and coarse hairs enhance the deposition of large particulate matter; the remaining nasal airways filter out particles as small as 6 µm in diameter. In the turbinate region, the airflow becomes laminar and the airstream is narrowed and directed superiorly, enhancing particle deposition, warming, and humidification. Nasal passages contribute as much as 50% of the total resistance of normal breathing. Nasal flaring, a sign of respiratory distress, reduces the resistance to inspiratory airflow through the nose and can improve ventilation (Chapter 365).

Although the nasal mucosa is more vascular, especially in the turbinate region than in the lower airways, the surface epithelium is similar, with ciliated cells, goblet cells, submucosal glands, and a covering blanket of mucus. The nasal secretions contain lysozyme and secretory immunoglobulin A (IgA), both of which have antimicrobial activity, and IgG, IgE, albumin, histamine, bacteria, lactoferrin, and cellular debris, as well as mucous glycoproteins, which provide viscoelastic properties. Aided by the ciliated cells, mucus flows toward the nasopharynx, where the airstream widens, the epithelium becomes squamous, and secretions are wiped away by swallowing. Replacement of the mucous layers occurs about every 10-20 min. Estimates of daily mucus production vary from 0.1-0.3 mg/kg/24 hr, with most of the mucus being produced by the submucosal glands.

Congenital Disorders

Congenital structural nasal malformations are uncommon compared with acquired abnormalities. The nasal bones can be congenitally absent so that the bridge of the nose fails to develop, resulting in nasal hypoplasia. Congenital absence of the nose (arhinia), complete or partial duplication, or a single centrally placed nostril can occur in isolation but is usually part of a malformation syndrome. Rarely, supernumerary teeth are found in the nose, or teeth grow into it from the maxilla.

Nasal bones can be sufficiently malformed to produce severe narrowing of the nasal passages. Often, such narrowing is associated with a high and narrow hard palate. Children with these defects can have significant obstruction to airflow during infections of the upper airways and are more susceptible to the development of chronic or recurrent hypoventilation (Chapter 17). Rarely, the alae nasi are sufficiently thin and poorly supported to result in inspiratory obstruction, or there may be congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction with cystic extension into the nasopharynx, causing respiratory distress.

Choanal Atresia

This is the most common congenital anomaly of the nose and has a frequency of ∼1/7,000 live births. It consists of a unilateral or bilateral bony (90%) or membranous (10%) septum between the nose and the pharynx; most cases are a combination of bony and membranous atresia. About 50-70% of affected infants have other congenital anomalies, with the anomalies occurring more often in bilateral cases. The CHARGE syndrome (coloboma, heart disease, atresia choanae, retarded growth and development or CNS anomalies or both, genital anomalies or hypogonadism or both, and ear anomalies or deafness or both) is one of the more common anomalies associated with choanal atresia. Most patients with CHARGE syndrome have mutations in the CHD7 gene, which is involved in chromatin organization. Approximately 10-20% of patients with choanal atresia have the CHARGE syndrome.

Clinical Manifestations

Newborn infants have a variable ability to breathe through their mouths, so nasal obstruction does not produce the same symptoms in every infant. When the obstruction is unilateral, the infant may be asymptomatic for a prolonged period, often until the 1st respiratory infection, when unilateral nasal discharge or persistent nasal obstruction can suggest the diagnosis. Infants with bilateral choanal atresia who have difficulty with mouth breathing make vigorous attempts to inspire, often suck in their lips, and develop cyanosis. Distressed children then cry (which relieves the cyanosis) and become calmer, with normal skin color, only to repeat the cycle after closing their mouths. Those who are able to breathe through their mouths at once experience difficulty when sucking and swallowing, becoming cyanotic when they attempt to feed.

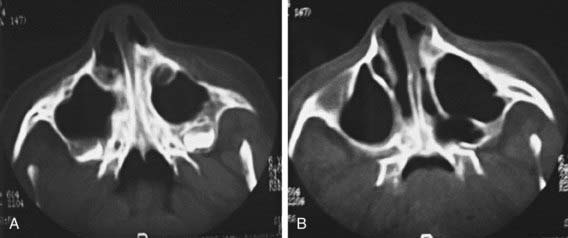

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is established by the inability to pass a firm catheter through each nostril 3-4 cm into the nasopharynx. The atretic plate may be seen directly with fiberoptic rhinoscopy. The anatomy is best evaluated by using high-resolution CT (Fig. 368-1).

Treatment

Initial treatment consists of prompt placement of an oral airway, maintaining the mouth in an open position, or intubation. A standard oral airway (such as that used in anesthesia) can be used, or a feeding nipple can be fashioned with large holes at the tip to facilitate air passage. Once an oral airway is established, the infant can be fed by gavage until breathing and eating without the assisted airway is possible. In bilateral cases, intubation or, less often, tracheotomy may be indicated. If the child is free of other serious medical problems, operative intervention is considered in the neonate; transnasal repair is the treatment of choice, with the introduction of small magnifying endoscopes and smaller surgical instruments and drills. Stents are usually left in place for weeks after the repair to prevent closure or stenosis. Tracheotomy should be considered in cases of bilateral atresia in which the child has other potentially life-threatening problems and in whom early surgical repair of the choanal atresia may not be appropriate or feasible. Operative correction of unilateral obstruction may be deferred for several years. In both unilateral and bilateral cases, restenosis necessitating dilation or reoperation, or both, is common. Mitomycin C has been used to help prevent the development of granulation tissue and stenosis.

Congenital Defects of the Nasal Septum

Perforation of the septum is most commonly acquired after birth secondary to infection, such as syphilis, tuberculosis, or trauma; rarely, it is developmental. Continuous positive airway pressure cannulas are a cause of iatrogenic perforation. Trauma from delivery is the most common cause of septal deviation noted at birth. When recognized early, it can be corrected with immediate realignment using blunt probes, cotton applicators, and topical anesthesia. Formal surgical correction, when required, is usually postponed to avoid disturbance of midface growth.

Mild septal deviations are common and usually asymptomatic; abnormal formation of the septum is uncommon unless other malformations are present, such as cleft lip or palate.

Pyriform Aperture Stenosis

Infants with this bony abnormality of the anterior nasal aperture present with severe nasal obstruction at birth or shortly thereafter. Diagnosis is made by CT of the nose; surgical repair by means of an anterior, sublabial approach may be needed if the child cannot feed or breathe without difficulty. A drill is used to enlarge the stenotic anterior bone apertures.

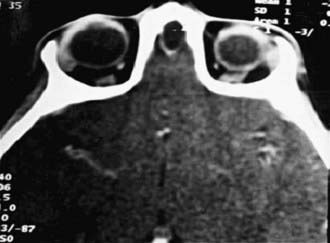

Congenital Midline Nasal Masses

Dermoids, gliomas, and encephaloceles (in descending order of frequency) occur intranasally or extranasally and can have intracranial connections. Nasal dermoids often have a dimple or pit on the nasal dorsum, sometimes with hair being present, and can predispose to intracranial infections if an intracranial fistula or sinus is present. Recurrent infection of the dermoid itself is more common. Gliomas or heterotopic brain tissue are firm, whereas encephaloceles are soft and enlarge with crying or the Valsalva maneuver. Diagnosis is based on physical examination findings and results from imaging studies. CT provides the best bony detail, but MRI allows sagittal views, which may be needed to further define intracranial extension (Fig. 368-2). Surgical excision of these masses is generally required, with the extent and surgical approach based on the type and size of the mass.

Figure 368-2 CT axial view showing nasal dermoid extension into the anterior cranial fossa through a defect in the cribriform plate.

(From Meher R, Singh I, Aggarwal S: Nasal dermoid with intracranial extension, J Postgrad Med 51:39–40, 2005.)

Other nasal masses include hemangiomas, congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction (which can occur as an intranasal mass), nasal polyps, and tumors such as rhabdomyosarcoma (Chapter 494). Nasal polyps are rarely present at birth, but the other masses often present at birth or in early infancy (Chapter 370).

Poor development of the paranasal sinuses and a narrow nasal airway are associated with recurrent or chronic upper airway infection in Down syndrome (Chapter 76).

Diagnosis and Treatment

In children with congenital nasal disorders, supportive care of the airway is given until the diagnosis is established. Diagnosis is made through a combination of flexible scoping and imaging studies, primarily CT scan. In the case of surgically correctable congenital problems such as choanal atresia, surgery is performed once the child is deemed healthy and free of life-threatening problems such as congenital heart disease.

Aramaki M, Udaka T, Kosaki R, et al. Phenotypic spectrum of CHARGE syndrome with CHD7 mutations. J Pediatr. 2006;148:410-414.

Burrow TA, Saal HM, de Alarcon A, et al. Characterization of congenital anomalies in individuals with choanal atresia. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009;135:543-547.

Durmaz A, Tosun F, Yldrm N, et al. Transnasal endoscopic repair of choanal atresia: results of 13 cases and meta-analysis. J Craniofac Surg. 2008;19(5):1270-1274.

Giffon SD, Goncalves VM, Zanardi VA, et al. Cerebellar involvement in midline facial defects with ocular hypertelorism. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2006;43:466-470.

Harley EH. Pediatric congenital nasal masses. Ear Nose Throat J. 1991;70:28-32.

Jongmans MCJ, Admiraal RJ, vander Donk KP, et al. CHARGE syndrome: the phenotypic spectrum of mutations in the CHD7 gene. J Med Genet. 2006;43:306-314.

Khafagy YW. Endoscopic repair of bilateral congenital choanal atresia. Laryngoscope. 2002;112:316-319.

Rahbar R, Jones DT, Nuss RC, et al. The role of mitomycin in the prevention and treatment of scar formation in the pediatric aerodigestive tract: friend or foe? Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2002;128:401-406.

Rohrich RJ, Lowe JB, Schwartz MR. The role of open rhinoplasty in the management of nasal dermoid cysts. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999;10:2163-2170.

Samadi DS, Shah UK, Handler SD, et al. Choanal atresia: a twenty-year review of medical comorbidities and surgical outcomes. Laryngoscope. 2003;113:254-258.

Van Den Abbeele T, Triglia JM, Francois M, et al. Congenital nasal pyriform aperture stenosis: diagnosis and management of 20 cases. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2001;110:70-75.

Veruloed MPJ, Hoevenadrs-van den Boom MAA, Knoors H, et al. CHARGE syndrome: relations between behavioral characteristics and medical conditions. Am J Med Genet. 2006;140A:851-862.

Zuckerman JD, Zapata S, Sobol SE. Single stage choanal atresia in the neonate. Arch Otolaryng Head Neck Surg. 2008;134:1090-1093.