Chapter 378 Congenital Anomalies of the Larynx, Trachea, and Bronchi

Because the larynx functions as a breathing passage, a valve to protect the lungs, and the primary organ of communication, symptoms of laryngeal anomalies are those of airway obstruction, difficulty feeding, and abnormalities of phonation (Chapter 365). Obstruction of the pharyngeal airway (due to enlarged tonsils, adenoids, tongue, or syndromes with midface hypoplasia) typically produces worse obstruction during sleep than during waking. Obstruction that is worse when awake is typically laryngeal, tracheal, or bronchial and is exacerbated by exertion. Congenital anomalies of the trachea and bronchi can create serious respiratory difficulties from the first minutes of life. Intrathoracic lesions typically cause expiratory wheezing and stridor, often masquerading as asthma. The expiratory wheezing contrasts to the inspiratory stridor caused by the extrathoracic lesions of congenital laryngeal anomalies, specifically laryngomalacia and bilateral vocal cord paralysis.

With airway obstruction, the severity of the obstructing lesion, the work of breathing, determines the necessity for diagnostic procedures and surgical intervention. Obstructive symptoms vary from mild to severe stridor with episodes of apnea, cyanosis, suprasternal (tracheal tugging) and subcostal retractions, dyspnea, and tachypnea. Chronic obstruction can cause failure to thrive.

Bibliography

Zoumalan R, Maddalozzo J, Holinger LD: Etiology of stridor in infants, Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 116:329–334, 2007

378.1 Laryngomalacia

Clinical Manifestations

Laryngomalacia is the most common congenital laryngeal anomaly and the most common cause of stridor in infants and children. Sixty percent of congenital laryngeal anomalies in children with stridor are due to laryngomalacia. Stridor is inspiratory, low-pitched, and exacerbated by any exertion: crying, agitation, or feeding. Stridor results from the collapse of supraglottic structures inwards during inspiration. Symptoms usually appear within the first 2 wk of life and increase in severity for up to 6 mo, although gradual improvement can begin at any time. Laryngopharyngeal reflux is commonly associated with laryngomalacia.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis is confirmed by outpatient flexible laryngoscopy (Fig. 378-1). When the work of breathing is moderate to severe, airway films and chest radiographs are indicated. With associated dysphagia, a contrast swallow study and esophagram may be considered. Because 15-60% of infants with laryngomalacia have synchronous airway anomalies, complete bronchoscopy is undertaken for patients with moderate to severe obstruction.

Treatment

Expectant observation is suitable for most infants because most symptoms resolve spontaneously as the child and airway grow. Laryngopharyngeal reflux is managed aggressively. For the few patients who have such severe obstruction that surgical intervention is unavoidable (patients with apparent life-threatening events, cor pulmonale, cyanosis, failure to thrive) endoscopic supraglottoplasty can be used to avoid tracheotomy.

Dickson JM, Richter GT, Derr JM, et al. Secondary airway lesions in infants with laryngomalacia. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2009;118:37-43.

Holinger LD, Konior RJ. Surgical management of severe laryngomalacia. Laryngoscope. 1989;99:136.

Thompson D. Abnormal integrative function in laryngomalacia. Laryngoscope. 2007;117(6(Pt Suppl 114)):1-33.

378.2 Congenital Subglottic Stenosis

Clinical Manifestations

Congenital subglottic stenosis is the 2nd most common cause of stridor. Stridor is biphasic or primarily inspiratory. Recurrent or persistent croup is typical. First symptoms often occur with a respiratory tract infection as the edema and thickened secretions of a common cold narrow an already compromised airway.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis made by airway radiographs is confirmed by direct laryngoscopy. As with all cases of upper airway obstruction, tracheostomy is avoided when possible. Dilation and endoscopic laser surgery are rarely effective because most congenital stenoses are cartilaginous. Anterior laryngotracheal decompression (cricoid split) or laryngotracheal reconstruction with cartilage grafting is usually effective in avoiding tracheostomy. The differential diagnosis includes other anatomic anomalies as well as a hemangioma or papillomatosis.

378.3 Vocal Cord Paralysis

Clinical Manifestations

Vocal cord paralysis is the 3rd most common congenital laryngeal anomaly that produces stridor in infants and children. Congenital central nervous system lesions such as myelomeningocele, Arnold-Chiari malformation, and hydrocephalus may be associated with bilateral paralysis.

Unilateral paralysis may be a result of recurrent laryngeal nerve injury following surgical management of congenital cardiac anomalies or tracheoesophageal fistula.

Bilateral vocal cord paralysis produces airway obstruction manifested by high-pitched inspiratory stridor: a phonatory sound or inspiratory cry. Unilateral paralysis causes aspiration, coughing, and choking; the cry is weak and breathy, but stridor and other symptoms of airway obstruction are less common.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of vocal cord paralysis is made by awake flexible laryngoscopy. A thorough investigation for the underlying primary cause is indicated. Because of the association with other congenital lesions, evaluation includes neurology and cardiology consultations as well as diagnostic endoscopy of the larynx, trachea, and bronchi.

Treatment

Vocal cord paralysis in infants usually resolves spontaneously within 6-12 mo. Bilateral paralysis can require temporary tracheotomy. For unilateral vocal cord paralysis with aspiration, injection laterally to the paralyzed vocal cord moves it medially to reduce aspiration and related complications.

378.4 Congenital Laryngeal Webs and Atresia

Most congenital laryngeal webs are glottic with subglottic extension and associated subglottic stenosis. Airway obstruction is not always present and may be related to the subglottic stenosis. Thick webs may be suspected in lateral radiographs of the airway. Diagnosis is made by direct laryngoscopy (Fig. 378-2). Treatment might require only incision or dilation. Webs with associated subglottic stenosis are likely to require cartilage augmentation of the cricoid cartilage (laryngotracheal reconstruction). Laryngeal atresia occurs as a complete glottic web and commonly is associated with tracheal agenesis and tracheoesophageal fistula.

378.5 Congenital Subglottic Hemangioma

Symptoms of airway obstruction typically occur within the 1st 2 mo. of life. Stridor is biphasic but usually more prominent during inspiration. A barking cough, hoarseness, and symptoms of recurrent or persistent croup are typical. A facial hemangioma is not always present, but when it is evident, it is in the beard distribution. Chest and neck radiographs can show the characteristic asymmetric narrowing of the subglottic larynx. Treatment is discussed in Chapter 382.3.

378.6 Laryngoceles and Saccular Cysts

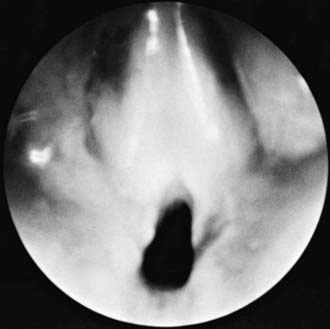

A laryngocele is an abnormal air-filled dilation of the laryngeal saccule. It communicates with the laryngeal lumen and, when intermittently filled with air, causes hoarseness and dyspnea. A saccular cyst (congenital cyst of the larynx) is distinguished from the laryngocele in that its lumen is isolated from the interior of the larynx and it contains mucus, not air. A saccular cyst may be visible on radiography, but the diagnosis is made by laryngoscopy (Fig. 378-3). Needle aspiration of the cyst confirms the diagnosis but rarely provides a cure. Approaches include endoscopic CO2 laser excision, endoscopic extended ventriculotomy, or, traditionally, external excision.

Figure 378-3 Endoscopic photograph of a saccular cyst.

(From Ahmad SM, Soliman AMS: Congenital anomalies of the larynx, Otolaryngol Clin North Am 40:177–191, 2007, Fig 3.)

Civantos FJ, Holinger LD. Laryngoceles and saccular cysts in infants and children. Arch Otolaryn Head Neck Surg. 1992;118:296-300.

Kirse DJ, Rees CJ, Celmer AW, et al. Endoscopic extended ventriculotomy for congenital saccular cysts of the larynx in infants. Arch Otolarygol Head Neck Surg. 2006;132(7):724-728.

378.7 Posterior Laryngeal Cleft and Laryngotracheoesophageal Cleft

The posterior laryngeal cleft (PLC) is characterized by aspiration and is due to a deficiency in the midline of the posterior larynx. In severe cases the cleft extends inferiorly into the cervical or thoracic trachea so there is no separation between the trachea and esophagus, creating a laryngotracheoesophageal cleft (LTEC). Laryngeal clefts can occur in families and are likely to be associated with tracheal agenesis, tracheoesophageal fistula, and multiple congenital anomalies, as with G syndrome, Opitz-Frias syndrome, and Pallister-Hall syndrome.

Initial symptoms are those of aspiration and respiratory difficulties. Esophagogram is undertaken with extreme caution. Confirmation of the diagnosis is made by direct laryngoscopy and bronchoscopy. Stabilization of the airway is the 1st priority. Gastroesophageal reflux must be controlled and a careful assessment for other congenital anomalies is undertaken before repair.

378.8 Vascular and Cardiac Anomalies

The aberrant innominate artery is the most common cause of secondary tracheomalacia (Chapter 426). Expiratory wheezing and cough occur and, rarely, reflex apnea or “dying spells.” Surgical intervention is rarely necessary. Infants are treated expectantly because the problem is self-limited.

The term vascular ring is used to describe vascular anomalies that result from abnormal development of the aortic arch complex. The double aortic arch is the most common complete vascular ring, encircling both the trachea and esophagus, compressing both. With few exceptions, these patients are symptomatic by 3 mo of age. Respiratory symptoms predominate, but dysphagia may be present. The diagnosis is established by barium esophagram that shows a posterior indentation of the esophagus by the vascular ring (Fig. 426-2). CT scan with contrast or MRI with angiography provides the surgeon the information needed (Chapter 426).

Other vascular anomalies include the pulmonary artery sling, which also requires surgical correction. The most common open (incomplete) vascular ring is the aberrant right subclavian artery. Although common, it is usually asymptomatic and of academic interest only.

Congenital cardiac defects are likely to compress the left main bronchus or lower trachea. Any condition that produces significant pulmonary hypertension increases the size of the pulmonary arteries, which in turn cause compression of the left main bronchus. Surgical correction of the underlying pathology to relieve pulmonary hypertension relieves the airway compression.

378.9 Tracheal Stenoses, Webs, and Atresia

Long-segment congenital tracheal stenosis with complete tracheal rings typically occurs within the 1st yr of life, usually after a crisis has been precipitated by an acute respiratory illness. The diagnosis may be suggested by plain radiographs. CT with contrast delineates associated intrathoracic anomalies such as the pulmonary artery sling, which occurs in one third of patients; one fourth have associated cardiac anomalies. Bronchoscopy is the best method to define the degree and extent of the stenosis and the associated abnormal bronchial branching pattern. Treatment of clinically significant stenosis involves tracheal resection of short segment stenosis, slide tracheoplasty for long segment stenosis. Congenital soft tissue stenoses and thin webs are rare. Dilation may be all that is required.

378.10 Foregut Cysts

The bronchogenic cyst, intramural esophageal cyst (esophageal duplication), and enteric cyst can all produce symptoms of respiratory obstruction and dysphagia. The diagnosis is suspected when chest radiographs or CT scan delineate the mass, and, in the case of enteric cyst, the associated vertebral anomaly. The treatment of all foregut cysts is surgical excision.