Chapter 438 Diseases of the Blood Vessels (Aneurysms and Fistulas)

438.1 Kawasaki Disease

(See also Chapter 160.)

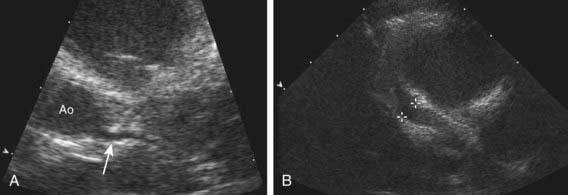

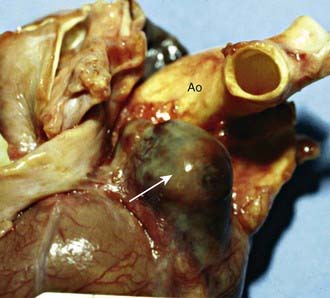

Aneurysms of the coronary or systemic arteries may complicate Kawasaki disease and are the leading cause of morbidity in this disease (Figs. 438-1 and 438-2 on the Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics website at www.expertconsult.com ![]() ). Other than in Kawasaki disease, aneurysms are not common in children and occur most frequently in the aorta in association with coarctation of the aorta, patent ductus arteriosus, and Marfan syndrome and in intracranial vessels (Chapter 594). They may also occur secondary to an infected embolus; infection contiguous to a blood vessel; trauma; congenital abnormalities of vessel structure, especially the medial wall; and arteritis, for example, polyarteritis nodosa, Behçet syndrome, and Takayasu arteritis (Chapter 161.2).

). Other than in Kawasaki disease, aneurysms are not common in children and occur most frequently in the aorta in association with coarctation of the aorta, patent ductus arteriosus, and Marfan syndrome and in intracranial vessels (Chapter 594). They may also occur secondary to an infected embolus; infection contiguous to a blood vessel; trauma; congenital abnormalities of vessel structure, especially the medial wall; and arteritis, for example, polyarteritis nodosa, Behçet syndrome, and Takayasu arteritis (Chapter 161.2).

438.2 Arteriovenous Fistulas

Arteriovenous fistulas may be limited to small cavernous hemangiomas or may be extensive (Chapters 499 and 642). The most common sites in infants and children are within the cranium, in the liver, in the lung, in the extremities, and in vessels in or near the thoracic wall. These fistulas, though usually congenital, may follow trauma or be a manifestation of hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (Osler-Weber-Rendu disease). Femoral arteriovenous fistulas are a rare complication of percutaneous femoral catheterization.

Clinical Manifestations

Clinical symptoms occur only in association with large arteriovenous communications when arterial blood flows into a low-pressure venous system without the resistance of the capillary bed; local venous pressure is increased, and arterial flow distal to the fistula is decreased. Systemic arterial resistance falls because of the runoff of blood through the fistula. Compensatory mechanisms include tachycardia and increased stroke volume so that cardiac output rises. Total blood volume is also increased. In large fistulas, left ventricular dilatation, a widened pulse pressure, and high output heart failure occur. CT, MRI, or injection of contrast material into an artery proximal to the fistula confirms the diagnosis.

Large intracranial arteriovenous fistulas most often occur in newborn infants in association with a vein of Galen malformation. The large intracranial left-to-right shunt results in heart failure secondary to the demand for high cardiac output. Patients with smaller communications may not have cardiovascular manifestations but may later be disposed to hydrocephalus (Chapter 585.11) or seizure disorders. The diagnosis can often be made by auscultation of a continuous murmur over the cranium. Older children with more diffuse intracranial arteriovenous malformations may be recognized on the basis of intracranial calcification and high cardiac output without cardiac failure.

Hepatic arteriovenous fistulas may be generalized or localized in the liver and may be hemangioendotheliomas or cavernous hemangiomas. The fistula may be located between the hepatic artery and the ductus venosus or portal vein. Congenital hemorrhagic telangiectasia may also be present. Large arteriovenous fistulas are associated with increased cardiac output and heart failure. Hepatomegaly is usual, and systolic or continuous murmurs may be audible over the liver.

Peripheral arteriovenous fistulas generally involve the extremities and are associated with disfigurement, swelling of the extremity, and visible hemangiomas. Some are located in areas that result in upper airway obstruction. Because only a small minority results in large arterial runoff, cardiac failure is uncommon.

Treatment

Medical management of heart failure is initially helpful in neonates with these conditions; with time, the size of the shunt may diminish and symptoms spontaneously regress. Hemangiomas of the liver often eventually disappear completely. Large liver hemangiomas have been treated with steroids, ε-aminocaproic acid, interferon, local compression, embolization, or local irradiation; the beneficial effects of these management options are not firmly established because individual patients display marked variation in clinical course without treatment. Catheter embolization is becoming the treatment of choice for many patients with a symptomatic arteriovenous fistula. Embolic agents that have been used include detachable balloons, steel (Gianturco) coils, and liquid tissue adhesives (cyanoacrylate). Often, multiple procedures are necessary before flow is significantly reduced. Surgical removal of a large fistula may be attempted in patients with severe cardiac failure and lack of improvement with medical treatment. Surgical treatment may be contraindicated or unsuccessful when the lesion is extensive and diffuse or is located in a position where adjoining tissue may be injured during the surgery or related procedures.

Abernethy LJ. Classification and imaging of vascular malformations in children. Eur Radiol. 2003;13:2483-2497.

Faughnan ME, Thabet A, Mei-Zahav M, et al. Pulmonary arteriovenous malformations in children: outcomes of transcatheter embolotherapy. J Pediatr. 2004;145:826-831.

Fong LV, Lee SH, Salmon AP. Diagnosis of cerebral arteriovenous malformations by colour Doppler examination. Eur Heart J. 1992;13:415-417.

Friedman DM, Verma R, Madrid M, et al. Recent improvement in outcome using transcatheter embolization techniques for neonatal aneurysmal malformations of the vein of Galen. Pediatrics. 1993;91:583-586.