Chapter 637 Evaluation of the Patient

History and Physical Examination

Although many skin disorders are easily recognized by simple inspection, the history and physical examination are often necessary for accurate assessment. The entire body surface, all mucous membranes, conjunctiva, hair, and nails should always be examined thoroughly under adequate illumination. The color, turgor, texture, temperature, and moisture of the skin and the growth, texture, caliber, and luster of the hair and nails should be noted. Skin lesions should be palpated, inspected, and classified on the bases of morphology, size, color, texture, firmness, configuration, location, and distribution. One must also decide whether the changes are those of the primary lesion itself or whether the clinical pattern has been altered by a secondary factor such as infection, trauma, or therapy.

Primary lesions are classified as macules, papules, patches, plaques, nodules, tumors, vesicles, bullae, pustules, wheals, and cysts. A macule represents an alteration in skin color but cannot be felt. When the lesion is >1 cm, the term patch is used. Papules are palpable solid lesions <1 cm. Aggregations of papules are referred to as plaques. Nodules are larger in diameter and deeper in the skin than papules. Tumors are usually larger than nodules and vary considerably in mobility and consistency. Vesicles are raised, fluid-filled lesions <0.5 cm in diameter; when larger, they are called bullae. Pustules contain purulent material. Wheals are flat-topped, palpable lesions of variable size, duration, and configuration that represent dermal collections of edema fluid. Cysts are circumscribed, thick-walled lesions; they are covered by a normal epidermis and contain fluid or semisolid material.

Primary lesions may change into secondary lesions, or secondary lesions may develop over time where no primary lesion existed. Primary lesions are usually more helpful for diagnostic purposes than secondary lesions. Secondary lesions include scales, ulcers, erosions, excoriations, fissures, crusts, and scars. Scales consist of compressed layers of stratum corneum cells that are retained on the skin surface. Erosions involve focal loss of the epidermis, and they heal without scarring. Ulcers extend into the dermis and tend to heal with scarring. Ulcerated lesions inflicted by scratching are often linear or angular in configuration and are called excoriations. Fissures are caused by splitting or cracking; they usually occur in diseased skin. Crusts consist of matted, retained accumulations of blood, serum, pus, and epithelial debris on the surface of a weeping lesion. Scars are end-stage lesions that can be thin, depressed and atrophic, raised and hypertrophic, or flat and pliable; they are composed of fibrous connective tissue. Lichenification is a thickening of skin with accentuation of normal skin lines that is caused by chronic irritation (rubbing, scratching) or inflammation.

If the diagnosis is not clear after a thorough examination, one or more diagnostic procedures may be indicated.

Biopsy of Skin

Biopsy of skin is occasionally required for diagnosis. Punch biopsy is a simple, relatively painless procedure and usually provides adequate tissue for examination if the appropriate lesion is sampled. The selection of a fresh, well-developed primary lesion is extremely important to obtain an accurate diagnosis. The site of the biopsy should have relatively low risk for damage to underlying dermal structures. After cleansing of the site, the skin is anesthetized by application of EMLA (eutectic mixture of local anesthetics) cream (containing lidocaine and prilocaine) and/or intradermal injection of 1-2% lidocaine (Xylocaine), with or without epinephrine, with a 27- or 30-gauge needle. A punch, 3 or 4 mm in diameter, is pressed firmly against the skin and rotated until it sinks to the proper depth. All 3 layers (epidermis, dermis, subcutis) should be contained in the plug. The plug should be lifted gently with forceps or extracted with a needle and separated from the underlying tissue with iris scissors. Bleeding abates with firm pressure and with suturing. The biopsy specimen should be placed in 10% formaldehyde solution (Formalin) for appropriate processing.

Wood Lamp

A Wood lamp emits ultraviolet light mainly at a wavelength of 365 nm. The examination, which is performed in a darkened room, is useful in detecting hypopigmented macules and certain superficial fungal infections of the scalp. Blue-green fluorescence is detectable at the base of each infected hair shaft in ectothrix and some endothrix infections. Scales and crusts may appear pale yellow, but this color is not evidence of a fungal infection. Dermatophyte lesions of the skin (tinea corporis) do not fluoresce; macules of tinea versicolor have a golden fluorescence under a Wood lamp. Erythrasma, an intertriginous infection caused by Corynebacterium minutissimum, may fluoresce pink-orange, whereas Pseudomonas aeruginosa is yellow-green under a Wood lamp. Discrete areas of altered pigment can often be visualized more clearly by using a Wood lamp, particularly if the pigmentary change is epidermal. Hyperpigmented lesions appear darker, and hypopigmented lesions (e.g., those seen in tuberous sclerosis) lighter than the surrounding skin.

Potassium Hydroxide Preparation

Potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation is a rapid and reliable method for detecting fungal elements of both yeasts and dermatophytes. Scaly lesions should be scraped at the active border for optimal recovery of mycelia and spores. Vesicles should be unroofed, and the blister top should be clipped and placed on a slide for examination. In tinea capitis, infected hairs must be plucked from the follicle; scales from the scalp do not usually contain mycelia. A few drops of 20% KOH are added to the specimen, which is then gently heated over an alcohol lamp until the KOH begins to bubble; alternatively, sufficient time (≈10-20 min) can be allowed for dissolution of the keratin at room temperature. Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) can be included in the KOH solution. The preparation is examined under low-intensity light for fungal elements.

Tzanck Smear

Tzanck smear is useful in the diagnosis of some viral infections (herpes simplex, varicella, herpes zoster, eczema herpeticum) and for the detection of acantholytic cells in pemphigus. An intact, fresh blister is ruptured and drained of fluid. The base of the blister is then scraped with a dull-edged instrument, with care taken to avoid drawing a significant amount of blood; the material is smeared on a clear glass slide and air dried. Staining with Giemsa stain is preferable, but Wright stain is acceptable. Balloon cells and multinucleated giant cells are diagnostic of herpesvirus infection; acantholytic epidermal cells are characteristic of pemphigus.

The direct fluorescent assay is more sensitive and specific. The keratinocytes are scraped from the base of the blister as described earlier. The laboratory stains the slide with labeled antibodies specific for varicella-zoster virus or herpes simplex virus. Observation of the slide with a fluorescence microscope documents the presence of the specific virus within the cells. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing for herpesviruses is rapid, safe, and both specific and sensitive.

Immunofluorescence Studies

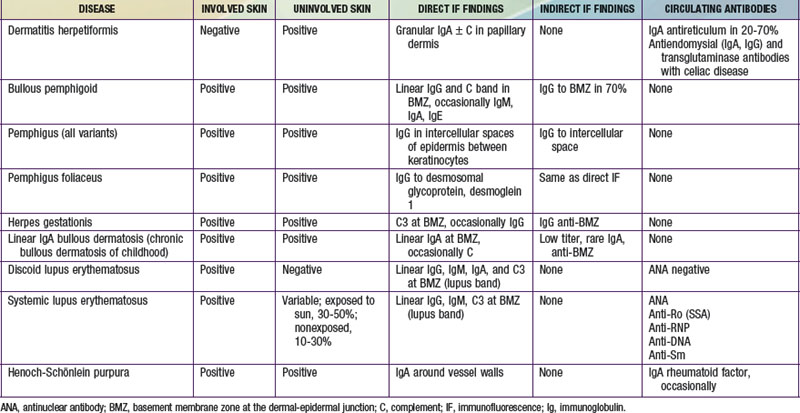

Immunofluorescence studies of skin can be used to detect tissue-fixed antibodies to skin components and complement; characteristic staining patterns are specific for certain skin disorders (Table 637-1). Serum can be used for identifying circulating antibodies. Skin biopsy specimens for direct immunofluorescence preparations should be obtained from involved sites except in those diseases for which perilesional skin or uninvolved skin is required. A punch biopsy sample is obtained, and the tissue is placed in a special transport medium or immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen for transport or storage. Thin cryostat sections of the specimen are incubated with fluorescein-conjugated antibodies to the specific antigens.

Serum of patients can be examined by indirect immunofluorescence techniques using sections of normal human skin, guinea pig lip, or monkey esophagus as substrate. The substrate is incubated with fresh or thawed frozen serum and then with fluorescein-conjugated antihuman globulin. If the serum contains antibody to epithelial components, its specific staining pattern can be seen on fluorescence microscopy. By serial dilution, the titer of circulating antibody can be estimated.

637.1 Cutaneous Manifestations of Systemic Diseases

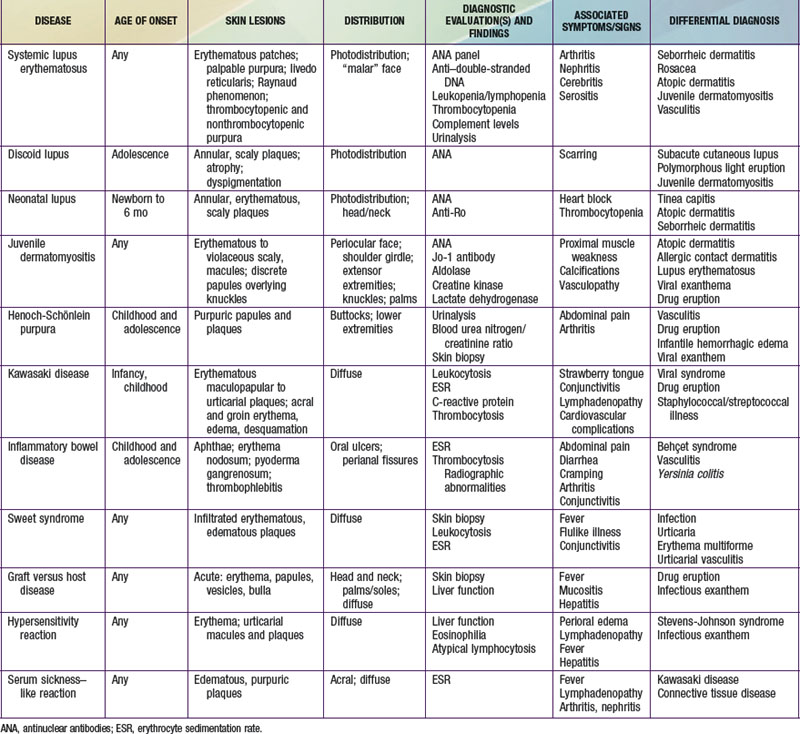

Selected diseases have signature skin findings, often as the presenting signs of illness, that can facilitate the assessment of patients with complex medical status (see Table 637-2 on the Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics website at www.expertconsult.com).

Connective Tissue Diseases

Lupus Erythematosus

Lupus erythematosus (LE; Chapter 152) is an idiopathic autoimmune inflammatory disease that may be multisystemic or confined to the skin.

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

Systemic LE (SLE) is a chronic inflammatory multisystem disease. It is a diagnosed when 4 of 11 well-defined criteria are present (Chapter 152). Three of the criteria are skin findings. Criterion 1 is the classic malar or “butterfly” rash (Fig. 637-1). It must be distinguished from other causes of a “red face,” most notably seborrheic dermatitis, atopic dermatitis, and rosacea. Criterion 2 is a discoid rash. Criterion 3 is a photosensitive erythematous macular or papular eruption (Fig. 637-2). Other associated but not diagnostic cutaneous findings include purpuric lesions, livedo reticularis, mucosal ulcerations, Raynaud phenomenon, and nonscarring alopecia.

Cutaneous LE demonstrates varying degrees of epidermal atrophy, plugging of hair follicles, and a vacuolar alteration at an inflamed dermal-epidermal junction. Deposition of immunoglobulins (IgM, IgG) and complement in lesional skin may help confirm the diagnosis. Immune deposits in nonlesional sun-exposed skin are found in the majority of patients with SLE (lupus band test). Treatment of skin lesions includes sun protection and low- to mid-potency topical corticosteroids.

Neonatal Lupus Erythematosus

Neonatal LE (NLE; Chapter 152.1) manifests during the 1st weeks to months of life as annular, erythematous, scaly plaques, typically on the head, neck, and upper trunk (Fig. 637-3). Ultraviolet light may exacerbate or initiate cutaneous lesions. NLE is often misdiagnosed as infantile eczema, seborrheic dermatitis, or tinea corporis. Passive transfer of maternal IgG (anti-Ro/La, SS-A/SS-B) antibodies causes the transient skin lesions; antibody levels wane by 6 mo, generally resulting in clearance of the rash. Congenital heart block occurs in 30% of affected infants, but only 10% of affected infants have both skin and cardiac abnormalities. Noncardiac extracutaneous manifestations, such as anemia, thrombocytopenia, and cholestatic liver disease, are uncommon. Maternal antibody (antinuclear antibody [ANA]) testing is indicated.

Discoid Lupus Erythematosus

Discoid LE (DLE) is uncommon in early childhood and manifests in late adolescence. The signature skin findings in DLE are chronic, erythematous, scaly, atrophic, telangiectatic plaques (Fig. 637-4) on sun-exposed skin that frequently heal with scarring and dyspigmentation. Extracutaneous features may include involvement of the nasal and oral mucosa, eyes, and nails. The differential diagnosis includes other photodermatoses, such as polymorphous light eruption, juvenile springtime eruption, and juvenile dermatomyositis. There is a distinct overlap between SLE and DLE, with common histopathologic features and photoexacerbation; most patients with DLE have normal laboratory results and do not progress to systemic disease. Topical sunscreens and steroids may be helpful. Intralesional steroids and oral antimalarials (hydroxychloroquine) are used for severe disease.

Juvenile Dermatomyositis

Characteristic skin findings are often the presenting sign of juvenile dermatomyositis (JDMS; Chapter 153). An ill-defined, erythematous to violaceous, scaly, minimally pruritic eruption occurs in photodistributed areas such as the face, upper trunk, and extensor extremities. Circumscribed periocular involvement of this heliotrope rash may take the appearance of “raccoon eyes,” particularly in young children. Distinctive papules overlying the knuckles (Gottron papules) are helpful in suggesting the diagnosis in the absence of associated muscle weakness (Fig. 637-5). Other cutaneous features include nail fold and gingival margin telangiectasia, palmar hyperkeratosis (“mechanic’s hands”), and a poikilodermatous (dyspigmentation and telangiectasia) eruption over the shoulder girdle (“shawl sign”). Cutaneous features may precede the systemic illness. The differential diagnosis includes atopic dermatitis, other connective tissue diseases, lichen planus, medication reactions, and infectious exanthems. The paucity of itch in JDMS may help eliminate some diagnostic considerations. Lesional skin demonstrates epidermal atrophy and vacuolar degeneration at the dermal-epidermal junction. JDMS is distinct from adult dermatomyositis in both presentation and prognosis. Pediatric patients have more difficulty with gastrointestinal vasculopathy and cutaneous calcifications but are not at increased risk of malignancy.

Treatment includes systemic steroidal and nonsteroidal immunosuppressants, intravenous immunoglobulin, anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) agents, and anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies; topical photoprotection is vital to prevent cutaneous exacerbations.

Progressive Systemic Sclerosis

Progressive systemic sclerosis frequently manifests as acral (sclerodactyly, ulceration, nail fold telangiectasia, or Raynaud phenomenon) and other cutaneous changes (pinched nose, furrowed perioral skin, or “scleroderma facies”) (Chapter 154). Overlap syndromes, such as CREST (calcinosis, Raynaud phenomenon, esophageal dysmotility, sclerodactyly, and telangiectasias) and mixed connective tissue disease, may include some physical and laboratory features of scleroderma.

Vasculitides

The vasculitides (Chapter 161) encompass a broad group of disorders having considerable overlap with connective tissue diseases. Immune-mediated inflammation of blood vessels of varying size may be caused by an underlying inflammatory state, infection, medication, or malignancy. Common clinical features include palpable nonthrombocytopenic purpuric skin lesions, arthritis, fever, myalgia, fatigue, and weight loss as well as an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR). Extracutaneous organs that may be involved include the joints, lungs, kidneys, and central nervous system.

Henoch-Schönlein Purpura (IgA Vasculitis)

Henoch-Schönlein purpura (HSP) is a vasculitis that manifests as purpuric lesions prominently on the buttocks and lower extremities of school-aged children (Fig. 637-6). Infantile hemorrhagic edema (IHE; also called acute hemorrhagic edema of infancy) shares some clinical features with HSP but appears in infants and toddlers. IHE is characterized by circumscribed purpuric papules and plaques on the trunk and extremities but, unlike HSP, commonly affects the face and lacks other organ involvement. IHE may follow a recent infection and manifests as peripheral edema and fever; patients with HSP are usually afebrile. HSP must also be differentiated from infectious causes of purpuric skin lesions, such as meningococcemia, Rocky Mountain spotted fever, and purpuric viral exanthems such as those caused by enteroviruses, as well as from juvenile rheumatoid arthritis and other vasculitides. Diagnosis is confirmed by vasculitis with the immunofluorescence finding of IgA in the blood vessel walls.

Kawasaki Disease

Kawasaki disease (Chapter 160) is a clinical diagnosis based on both cutaneous and extracutaneous features. The skin eruption of Kawasaki disease may be polymorphic, manifesting variously as urticarial, maculopapular, or morbilliform patches and plaques on the trunk and extremities, but early involvement with erythema and peeling in the perineum/inguinal region may be an initial clue to the diagnosis. Acral edema and desquamation are also prominent features but typically occur later. Conjunctivitis (nonpurulent), often with sparing of the limbus, and lingual plaques (“white strawberry tongue”) that shed to produce denuded, erythematous patches with prominent papilla (“strawberry tongue”) are classic mucocutaneous features.

Behçet Disease

Behçet disease (Chapter 155) is multisystem disease that includes oral and genital ulceration and ocular disease (uveitis, relapsing iridocyclitis). Recurrent aphthous stomatitis is present in almost all patients and is commonly the presenting symptom. Genital ulcerations may resemble aphthae, can occur on the penis or scrotum, and may be particularly painful in females. Additional skin findings may include folliculitis, purpuric lesions, erythema nodosum, and pustule formation after venipuncture or skin trauma (pathergy). Differential diagnosis of oral lesions includes recurrent aphthous stomatitis, herpes simplex, and less common oculocutaneous syndromes (e.g., MAGIC [mouth and genital ulcers with inflamed cartilage] syndrome). Skin biopsy demonstrates nongranulomatous vasculitis in all vessel sizes. Oral lesions may respond to swish and spit/swallow preparations variably including corticosteroids, antihistamines, antibiotics, and analgesics.

Gastrointestinal Diseases

Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Up to 30% of patients with ulcerative colitis (Chapter 328.1) present with cutaneous manifestations. Aphthous ulcers are common and may worsen with gastrointestinal exacerbations. Erythema nodosum, occurring in up to 10% of patients, manifests as warm, erythematous nodules, often on the distal lower extremities. Pyoderma gangrenosum is a focal, ulcerative process that has distinctive, inflamed, undermined borders and a purulent, boggy center. Thrombophlebitis also occurs at an increased rate in patients with ulcerative colitis. In most cases, treatment of the underlying disease state improves the cutaneous sequelae.

Crohn disease, or regional enteritis (Chapter 328.2), classically manifests as perianal fissures and skin tags, abscesses, sinuses, and fistulas; these may be presenting signs. As in ulcerative colitis, aphthae, erythema nodosum, and pyoderma gangrenosum occur at increased frequency and may improve with treatment of the underlying disease. Noncaseating granulomatous inflammation is seen on routine histopathology, and when found in skin not contiguous with the intestinal tract, is labeled metastatic Crohn disease. Metastatic lesions may appear as solitary or multiple, localized plaques or nodules and may be located on perianal, perioral, or other cutaneous surfaces, including scars and ileostomy sites. Standard therapy includes immunosuppressive medications, anti-TNF agents, anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies, nutritional support, and surgery for complications.

Cutaneous Manifestations of Malignancy

Cutaneous metastases may manifest as firm nodules at any cutaneous site. Distinctive paraneoplastic reaction patterns may result in sometimes striking rashes. Some genetic syndromes have an increased malignancy risk that may be suggested initially by cutaneous signs.

Sweet Syndrome

Also known as acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis, Sweet syndrome (Chapter 161.5) manifests abruptly as tender, erythematous, edematous plaques or nodules on any area of the skin, often accompanied by fever, anemia, and leukocytosis. Diagnosis is confirmed by the presence of a dense neutrophilic infiltrate without evidence of vasculitis. The differential diagnosis includes pyoderma gangrenosum, cellulitis, erythema multiforme, Behçet disease, and erythema nodosum. The etiology of Sweet syndrome is unknown but may involve a hypersensitivity reaction to a bacterial, viral, or tumor antigen. Forty-two percent of cases of Sweet’s syndrome in childhood occur without an identifiable etiology. The other 58% have been associated with recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis, vasculitis with aortitis, recurrent infection due to immunodeficiency, arthritis, SLE, aplastic anemia, Fanconi anemia, and leukemia. Sweet syndrome is sensitive to oral corticosteroids.

Necrolytic Migratory Erythema

Necrolytic migratory erythema (NME), or glucagonoma syndrome, is a distinctive migratory erythema that often signals an underlying neoplasm, usually an α-cell pancreatic tumor. Polycyclic erythematous patches and plaques on the trunk, extremities, and groin occur in association with glossitis and cheilitis. Elevated glucagon levels, glucose intolerance, and hypoaminoacidemia confirm the diagnosis, and tumor resection leads to resolution of the rash.

Other cutaneous findings that may signal an underlying malignancy include pruritus, ichthyosis, acanthosis nigricans, urticaria, pemphigus, and erythroderma.

Cutaneous Reactions in the Setting of Immunosuppression

Medication reactions, infectious etiologies, and graft versus host disease (GVHD) are included in the differential diagnosis in immunosuppressed patients; cutaneous and histologic similarities can be confounding.

Medication Reactions

The majority of medication reactions are mild morbilliform or exanthematous eruptions of little clinical consequence. Identifying the suspect medication may be difficult owing to the many medications used in immunosuppressed patients. Features that may help identify suspect medications include rash onset relative to exposure, character of distribution and spread, associated symptoms, and laboratory data. Medication eruptions begin on the trunk 7-10 days after exposure; they spread peripherally and are associated with pruritus and, less commonly, with fever, arthralgia, and lymphadenopathy. Eosinophilia may support a diagnosis of drug eruption but may be absent in the setting of bone marrow suppression. Penicillins, sulfa drugs, cephalosporins, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, anticonvulsants, and, on occasion, aminoglycosides are common offenders. Medication eruptions may resolve despite continued use of the offending agent, or they may progress to more severe involvement. A careful drug history, elimination of all nonessential, suspect medications or change to medications of dissimilar class, and treatment of pruritus with emollients, topical steroids, antihistamines, and antipruritics are indicated. Skin biopsies are rarely useful in distinguishing medication eruptions from infectious exanthems, although GVHD, if sufficiently advanced, may have signature histopathologic findings.

Graft versus Host Disease

GVHD (Chapter 131) may have florid cutaneous expression in addition to characteristic extracutaneous features such as fever, mucositis, diarrhea, and hepatitis. It may be either acute or chronic. Acute GVHD occurs in 35-50% of hematopoietic stem cell transplants and may be mistaken for a medication reaction or infectious exanthem, on the basis of the nonspecific erythematous maculopapular eruption that often starts focally and generalizes. Features that may suggest GVHD include timing of eruption (typically 1-3 wk after transplantation, at the time of hematopoietic reconstitution), initial involvement of the head and neck including the ears, and subsequent spread to the trunk, extremities, palms, and soles. Chronic GVHD, which occurs in ≈20% of long-term transplant survivors, is seen most often in patients who have previously experienced acute GVHD. About 50% of patients with acute GVHD eventually have chronic GVHD. Cutaneous manifestations of chronic GVHD are distinctive, with sclerotic, dyspigmented scaly plaques and lichenoid papules predominating (Fig. 637-7). Treatment includes systemic immunosuppression supplemented by topical steroids, topical immunomodulators, antihistamines, antipruritics, and emollients. Chronic disease may also respond to pentostatin, mycophenolate mofetil, photochemotherapy (PUVA), UVA-1, and plasmapheresis. GVHD may also develop in susceptible patients who have not undergone transplantation, such as the severely immunosuppressed neonate or infant in response to therapeutic transfusion of nonirradiated blood products, the fetus with congenital immunodeficiency and with transplacental passage of maternal lymphocytes, as well as the older child with malignancy who has received nonirradiated blood products.

Bolanos-Meade J, Vogelsang GB. Chronic graft-versus host disease. Curr Pharm Des. 2008;14:1974-1986.

Borlu M, Uksal U, Ferahbas A, et al. Clinical features of Behçet’s disease in children. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:713-716.

Fiore E, Rizzi M, Ragazzi M, et al. Acute hemorrhagic edema of young children (cockade purpura and edema): a case series and systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:684-695.

Hospach T, von den Driesch P, Dannecker GE. Acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis (Sweet’s syndrome) in childhood and adolescence: two new patients and review of the literature on associated diseases. Eur J Pediatr. 2009;168:1-9.

Jacobsohn DA, Vogelsang GB. Acute graft versus host disease. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2007;2:35.

Lee LA. Transient autoimmunity related to maternal autoantibodies: neonatal lupus. Autoimmune Rev. 2005;4:207-213.

Pluchinotta FR, Schiavo B, Vittadello F, et al. Distinctive clinical features of pediatric systemic lupus erythematosus in three different age classes. Lupus. 2007;16:550-555.

Saulsbury FT. Clinical update: Henoch-Schönlein purpura. Lancet. 2007;369:976-978.

Shah KN, Honig PJ, Yan AC. Urticaria multiforme: a case series and review of acute annular urticarial hypersensitivity syndromes in children. Pediatrics. 2007;119:e1177-e1183.

Timani S, Mutasim DF. Skin manifestation of inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Dermatol. 2008;26:265-273.

Van Beek AP, de Haas ER, van Vloten WA, et al. The glucagonoma syndrome and necrolytic migratory erythema: a clinical review. Eur J Endocrinol. 2004;151:531-537.

Zulian F, Martini G. Childhood systemic sclerosis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2007;19:592-597.

637.2 Multisystem Medication Reactions

See also Chapter 146.

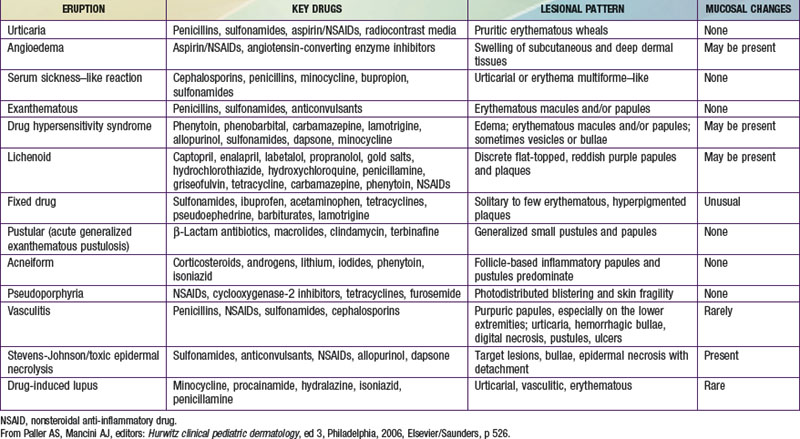

Most cutaneous reactions that result from the use of systemic medications are confined to the skin and resolve without sequelae after discontinuation of the offending agent (see Table 637-3 on the Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics website at www.expertconsult.com). More severe drug eruptions may be life-threatening, making rapid recognition vital (Chapter 646).

Drug Rash with Eosinophilia and Systemic Symptoms (Dress Syndrome)

DRESS syndrome, or drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms, was formerly called anticonvulsant hypersensitivity syndrome and pseudolymphoma syndrome. It is classically seen 1-6 wk after initial exposure to an aromatic anticonvulsant or other drugs (allopurinol, minocycline, sulfonamides, other antibiotics) and often manifest as the triad of fever, rash, and hepatitis. The skin rash is characterized by a pruritic, diffuse, erythematous to urticarial eruption of coalescing plaques (Fig. 637-8). Exfoliation early in the course, as seen in toxic epidermal necrolysis, is uncommon. If mucous membrane involvement occurs, it is usually mild. Prominent periocular or facial edema, cervical lymphadenopathy, pharyngitis, and malaise accompany this dramatic cutaneous eruption. Eosinophilia (≥ 500/µL) occurs in up to 30% of patients. Atypical lymphocytosis is common. Hepatitis ranging from mild elevation of liver transaminase values to frank hepatic failure may also be accompanied by interstitial nephritis, pneumonitis, myocarditis, shock, and encephalitis. Late-onset (several months) thyroiditis and hypothyroidism may occur as a result of antimicrosomal antibodies directed against thyroid peroxidases involved in drug metabolism. A heritable defect in the epoxide hydrolase pathway, in the case of anticonvulsants, leads to accumulation of toxic metabolites, which react with lymphocytes. Anticonvulsants with the distinctive aromatic structure (carbamazepine, phenobarbital, phenytoin) carry a high risk of triggering hypersensitivity syndrome in susceptible individuals and their first-degree relatives. The differential diagnosis includes Stevens-Johnson syndrome, viral exanthem, macrophage activation and hemophagocytic syndromes, and GVHD in the appropriate clinical setting. In addition to anticonvulsants, sulfonamides may cause similar symptoms on 1st exposure because of abnormalities in glutathione S-transferase pathways. Many other antibiotics have also been implicated as causes of this syndrome.

Figure 637-8 Nine yr old boy with cerebral palsy and seizures treated with carbamazepine. Seventeen days after start of therapy he demonstrated fever, rash (exanthematous), lymphadenopathy and nephritis, all part of a drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome.

(From Schachner LA, Hansen RC, editors: Pediatric dermatology, ed 3, Philadelphia, 2003, Mosby, p 1269.)

Withdrawal of the medication is the primary therapeutic intervention, with symptomatic treatment of itch and/or pain being universal. Oral corticosteroid therapy may be acutely beneficial, especially in the setting of rapidly evolving hepatic or renal involvement in hypersensitivity syndrome. Counseling about increased risk with similar medications and in siblings is important. Hypersensitivity reactions can flare, both in the skin and other organ systems, well after the medication has been withdrawn and initial improvement achieved, necessitating close follow-up for several months.

Serum Sickness–Like Reaction

Serum sickness–like reaction (SSLR) manifests as urticarial to purpuric, sharply marginated coalescing plaques and acral erythema/edema, often in association with arthritis, lymphadenopathy, and fever. Unlike with true serum sickness (Chapter 144), laboratory evidence of circulating immune complexes and multisystem involvement of vasculitis are typically absent. The differential diagnosis includes Kawasaki disease, connective tissue diseases, acute annular urticaria, and hypersensitivity syndrome. SSLR is most commonly seen after exposure to cefaclor. The cause is unknown, but a toxic metabolite is suspected. In contrast to hypersensitivity reaction, SSLR typically occurs after repeated drug exposures. Symptomatic treatment and medication withdrawal are recommended.

Acute Generalized Exanthematous Pustulosis

Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP) is a pustular lesion, often drug-related (aminopenicillins, macrolides, sulfonamides), that is characterized by many nonfollicular sterile pustules with underlying edema and erythema (Fig. 637-9). Neutrophilia and fever are common, whereas eosinophilia is less common than in DRESS syndrome. The rash may burn or itch; mucous membrane involvement is rare and often mild. Internal organ involvement is not common and often is asymptomatic. Therapy consists of stopping the causative drug; steroids may be needed in some severe cases.

Figure 637-9 Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP) is characterized by the acute onset of fever and generalized erythema with numerous, small, discrete, sterile, nonfollicular pustules. Pustules may appear in a few days after the drug therapy is started. Pustules resolve in less than 15 days, followed by desquamation.

(From Habif TP, editor: Clinical dermatology, ed 4, Philadelphia, 2004, Mosby, p 490.)

Ben m’rad M, Leclerc-Mercier S, Blanche P, et al. Drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome: clinical and biologic patterns in 24 patients. Medicine. 2009;88:131-140.

Chen YC, Ching HC, Chu CY. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms. Arch Dematol. 2010;146(12):1373-1379.

Eshki M, Allamore L, Musette P, et al. Twelve-year analysis of severe cases of drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:67-72.

Lerch M, Pichler WJ. The immunological and clinical spectrum of delayed drug-induced exanthems. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;4:411-419.

Sidoroff A, Halevy S, Nico Bouwes J, et al. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP)—a clinical reaction pattern. J Cutan Pathol. 2001;28:113-119.