Chapter 6 Cornea

Introduction

Anatomy and physiology

General aspects

The cornea is a complex structure which, as well as having a protective role, is responsible for about three-quarters of the optical power of the eye. The normal cornea is free of blood vessels; nutrients are supplied and metabolic products removed mainly via the aqueous humour posteriorly and the tears anteriorly, with a downhill anterior–posterior oxygen gradient. The cornea is the most densely innervated tissue in the body, with a subepithelial and a deeper stromal plexus, both supplied by the 1st division of the trigeminal nerve. For this reason corneal abrasions and disease processes such as bullous keratopathy are associated with pain, photophobia and reflex lacrimation.

Dimensions

The average corneal diameter is 11.5 mm vertically and 12 mm horizontally. It is 540 µm thick centrally on average, and thicker towards the periphery. Central corneal thickness varies between individuals and is a key determinant of the conventionally-measured intraocular pressure level.

Layers

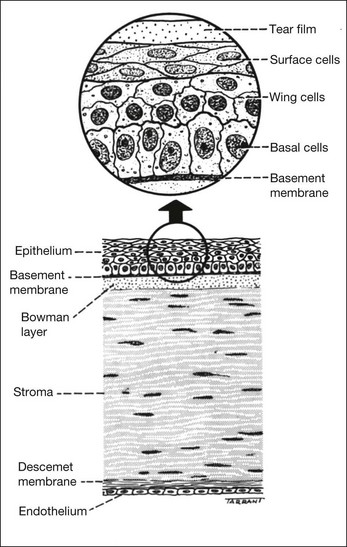

The cornea consists of the following layers (Fig. 6.1), each of which is critical to normal function:

Signs of corneal inflammation

Superficial lesions

Deep lesions

Table 6.1 Characteristics of infective versus sterile corneal infiltrates

| Infective | Sterile | |

|---|---|---|

| Size | Tend to be larger | Tend to be smaller |

| Progression | Rapid | Slow |

| Epithelial defect | Very common and larger when present | Much less common and if present tends to be small |

| Pain | Moderate-severe | Mild |

| Discharge | Purulent | Mucopurulent |

| Single or multiple | Typically single | Commonly multiple |

| Unilateral or bilateral | Unilateral | Often bilateral |

| Anterior chamber reaction | Severe | Mild |

| Location | Often central | Typically peripheral |

| Adjacent corneal reaction | Extensive | Limited |

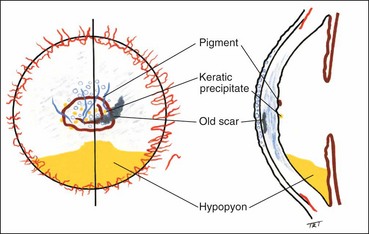

Documentation of clinical signs

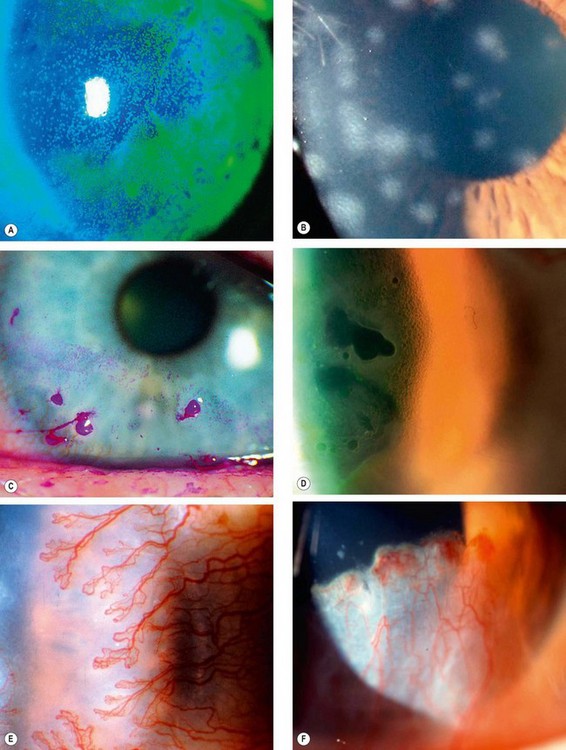

Clinical signs should be illustrated with a labelled diagram, particularly in order to facilitate monitoring. The dimensions of epithelial and stromal lesions, and the depth of new vessels, should all be recorded. Colour coding can be helpful (Fig. 6.4).

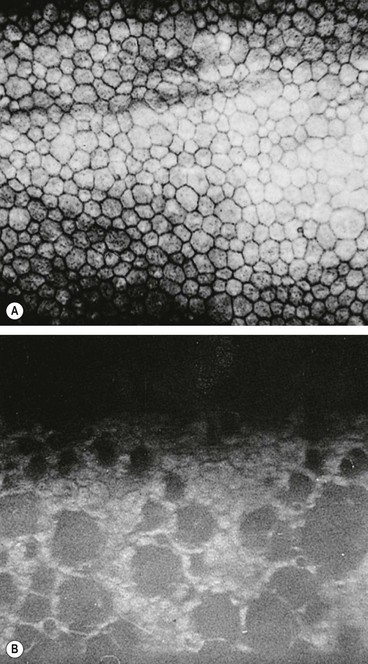

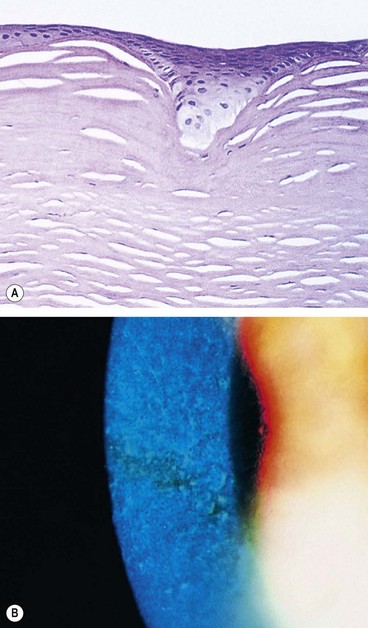

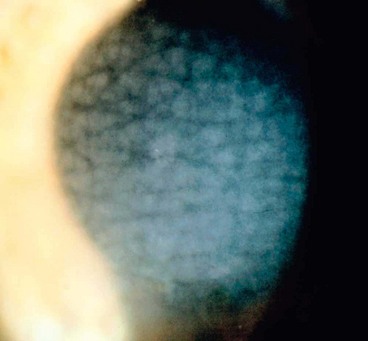

Specular microscopy

Specular microscopy is the study of the changes in different layers of the cornea under very high magnification (100 times greater than slit-lamp biomicroscopy) that is mainly being used to assess the endothelium. The image is analyzed with respect to cellular size, shape, density and distribution. The normal endothelial cell is a regular hexagon (Fig. 6.5A) and the normal cell density in a young adult is about 3000 cells/mm2.

Principles of treatment

Control of infection and inflammation

Promotion of epithelial healing

Re-epithelialization is of great importance in any corneal disease, as thinning seldom progresses if the epithelium is intact.

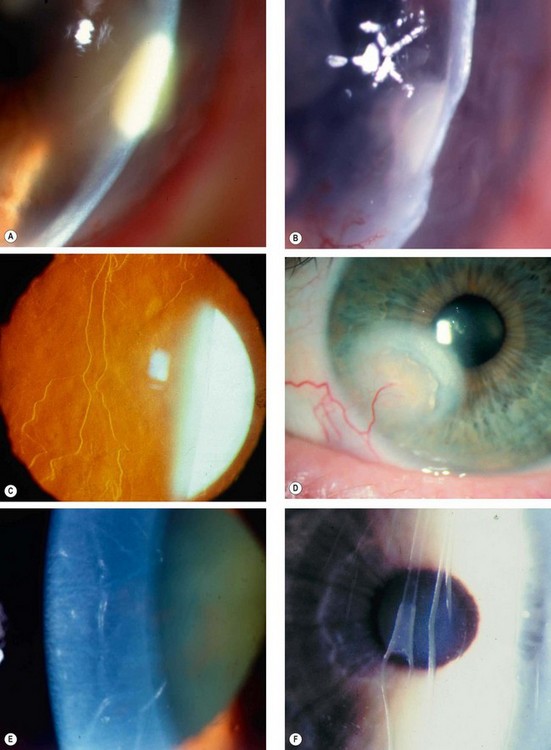

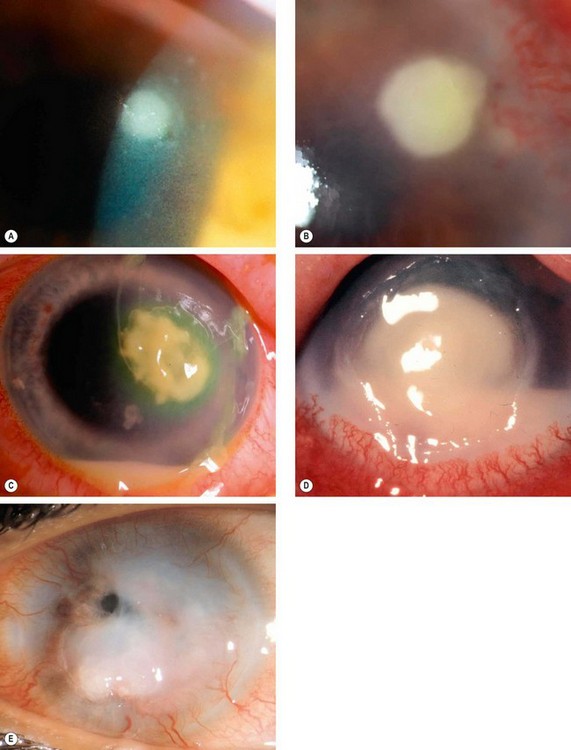

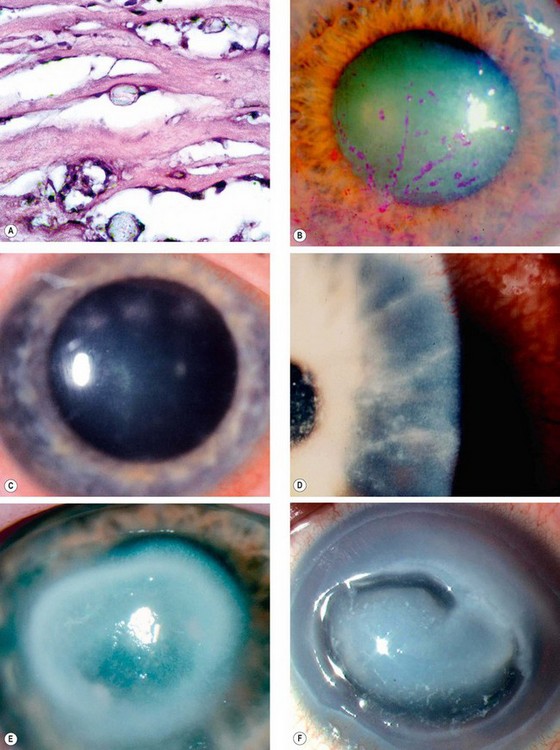

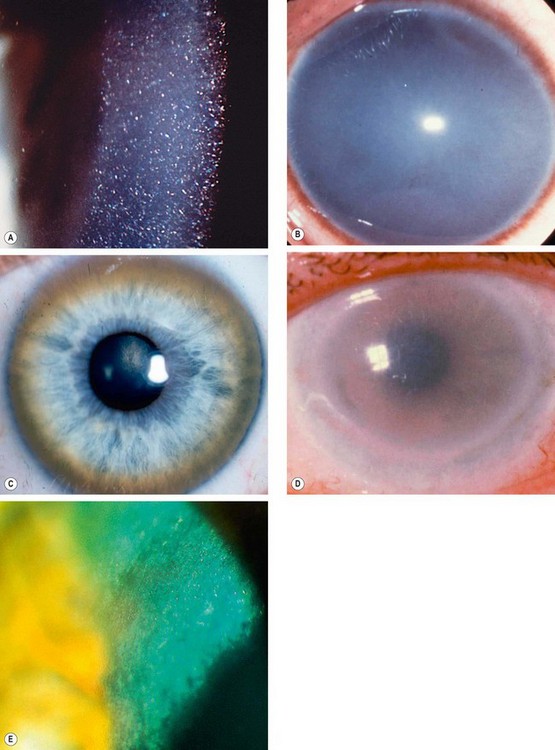

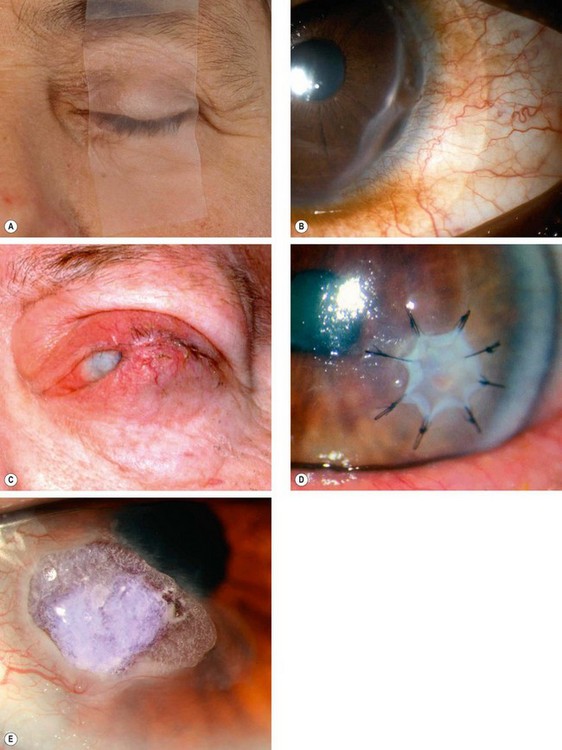

Fig. 6.6 Methods of promoting epithelial healing. (A) Taping the lids temporarily; (B) bandage contact lens in an eye with a small perforation; (C) tarsorrhaphy; (D) amniotic membrane graft over a persistent epithelial defect; (E) tissue glue under a bandage contact lens in an eye with severe thinning

(Courtesy of S Tuft – figs A, B, D and E)

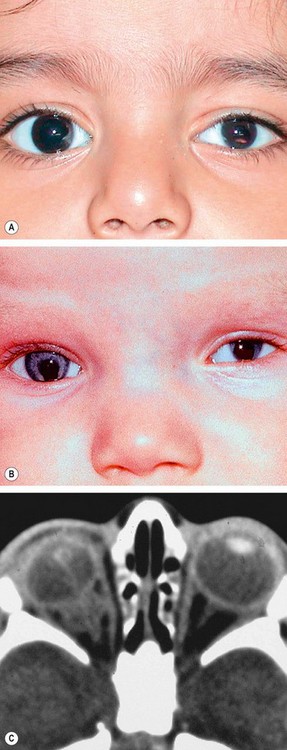

Bacterial keratitis

Pathogenesis

Pathogens

Bacterial keratitis usually only develops when the ocular defences have been compromised (see below). However, some bacteria, including N. gonorrhoeae, N. meningitidis, C. diphtheriae, and H. influenzae are able to penetrate a normal corneal epithelium, usually in association with severe conjunctivitis. It is important to remember that infections may be polymicrobial, including bacterial and fungal co-infection. The most common pathogens are the following:

Risk factors

Clinical features

Investigations

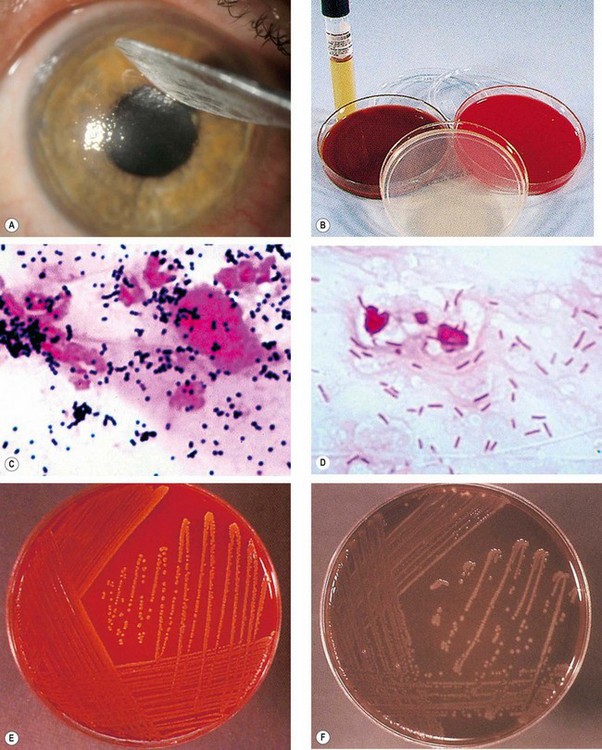

Fig. 6.8 Bacteriology. (A) Corneal scraping; (B) culture media; (C) smear shows Gram-positive spherical cocci mostly arranged in clusters (S. aureus); (D) smear shows Gram-negative bacilli (P. aeruginosa); (E) S. aureus grown on blood agar forming golden colonies with a shiny surface; (F) N. gonorrhoeae grown on chocolate agar

(Courtesy of J Harry – fig. A; Emond, Welsby and Rowland, from Colour Atlas of Infectious Diseases, Mosby 2003 – figs B–F)

Table 6.2 Culture media for corneal scrapings

| Medium | Notes | Specificity |

|---|---|---|

| Blood agar (Fig. 6.8E) | 5–10% sheep or horse blood | Most bacteria and fungi except Neisseria, Haemophilus and Moraxella |

| Chocolate agar (Fig. 6.8F) | Blood agar in which the cells have been lysed by heating. Does not contain chocolate! | Fastidious bacteria, particularly H. Influenzae, Neisseria and Moraxella |

| Sabouraud dextrose agar | Low pH and antibiotic (e.g. chloramphenicol) to deter bacterial growth | Fungi |

| Non-nutrient agar seeded with E. coli | E. coli is a food source for Acanthamoeba | Acanthamoeba |

| Brain heart infusion | Rich lightly buffered medium providing a wide range of substrates | Difficult-to-culture organisms; particularly suitable for streptococci and meningococci. Supports yeast and fungal growth |

| Cooked meat broth | Developed during the First World War for the growth of battlefield anaerobes | Anaerobic (e.g. Propionibacterium acnes) as well as fastidious bacteria |

| Löwenstein-Jensen | Contains various nutrients together with bacterial growth inhibitors | Mycobacteria, Nocardia |

Table 6.3 Stains for corneal and conjunctival scrapes

| Stain | Organism |

|---|---|

| Gram | Bacteria, fungi, Microsporidia |

| Giemsa | Bacteria, fungi, Acanthamoeba, Microsporidia |

| Calcofluor white (fluorescent microscope) | Acanthamoeba, fungi, Microsporidia |

| Acid-fast stain (AFB) e.g. Ziehl–Neelsen, Auramine O (fluorescent) |

Mycobacterium, Nocardia spp. |

| Grocott-Gömöri methenamine-silver | Fungi, Acanthamoeba, Microsporidia |

| Periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) | Fungi, Acanthamoeba |

Refrigerated media should be gently warmed to room temperature prior to sample application.

Most laboratories test for antibiotic sensitivity using a disc diffusion (Kirby–Bauer) method. The relevance of this to topical antibiotic instillation, where very high tissue levels can be achieved, is uncertain.

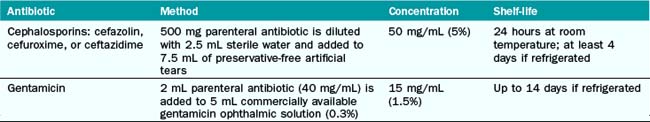

Treatment

General considerations

Local therapy

Topical therapy can achieve high tissue concentration and initially should consist of broad spectrum antibiotics which cover most common pathogens. Initially instillation is at hourly intervals day and night for 24–48 hours, and then is tapered according to clinical progress.

Table 6.4 Antibiotics for treatment of keratitis

| Isolate | Antibiotic | Concentration |

|---|---|---|

| Empirical treatment | Fluoroquinolone monotherapy or | 0.3% |

| Cefuroxime + | 5% | |

| Gentamicin duotherapy | 1.5% | |

| Gram-positive cocci | Cefuroxime | 0.3% |

| Vancomycin or Teicoplanin | 5% 1% |

|

| Gram-negative rods | Gentamicin or | 1.5% |

| Fluoroquinolone or | 0.3% | |

| Ceftazidime | 5% | |

| Gram-negative cocci | Fluoroquinolone | 0.3% |

| Ceftriaxone | 5% | |

| Mycobacteria | Amikacin or | 2% |

| Clarithromycin | 1% | |

| Nocardia | Amikacin or | 2% |

| Trimethorim + Sulphamethoxazole | 1.6% | |

| 8% |

Systemic antibiotics

Systemic antibiotics are not usually given, but may be appropriate in the following circumstances:

Management of apparent treatment failure

Fungal keratitis

Introduction

Pathogenesis

Fungi are a group of microorganisms that have rigid walls and a distinct nucleus with multiple chromosomes containing both DNA and RNA. Fungal keratitis is rare in temperate countries but is a major cause of visual loss in tropical and developing countries. The two main types of fungi causing keratitis are:

Predisposing factors

Common predisposing factors are chronic ocular surface disease, long-term use of topical steroids (often in conjunction with prior corneal transplantation), contact lens wear, systemic immunosuppression and diabetes. Filamentary keratitis may be associated with trauma, often relatively minor, involving plant matter or gardening/agricultural tools.

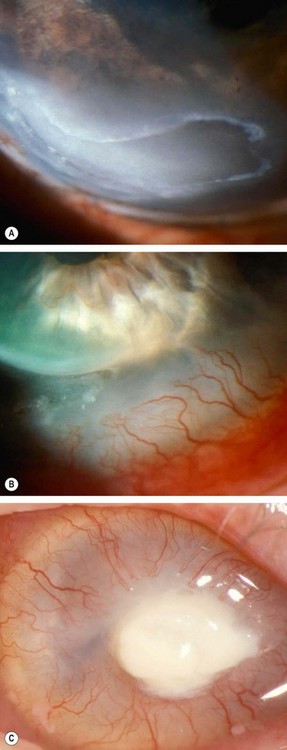

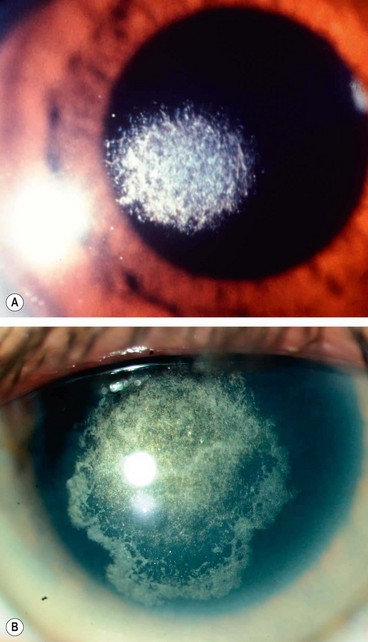

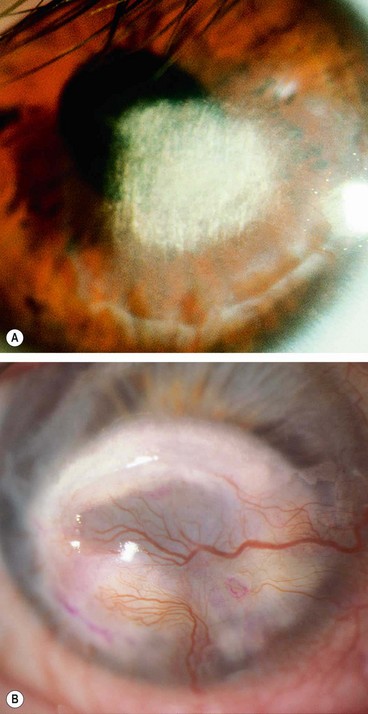

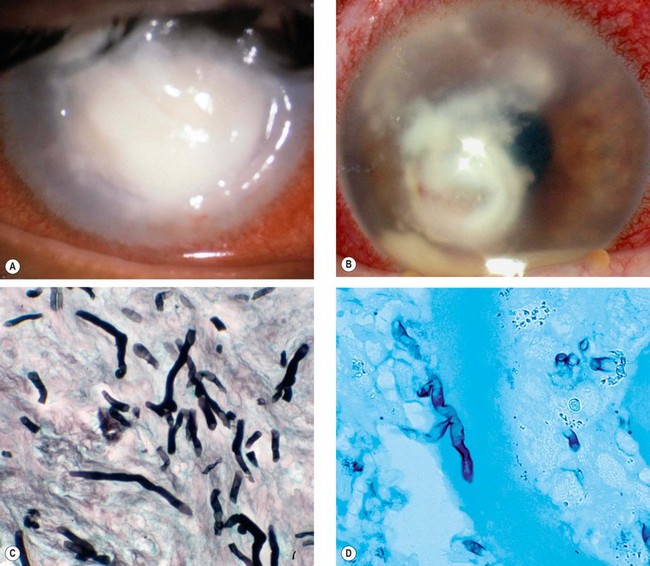

Candida and filamentous keratitis

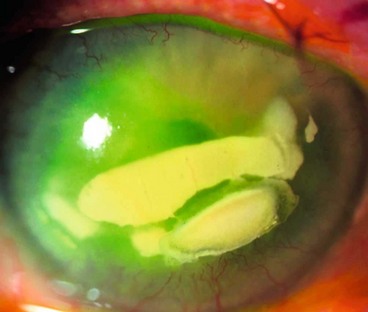

Clinical features

The diagnosis is often delayed unless there is a high index of suspicion, and often infection will initially have been presumed to be bacterial.

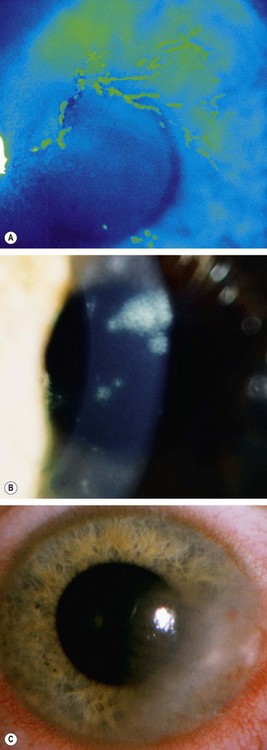

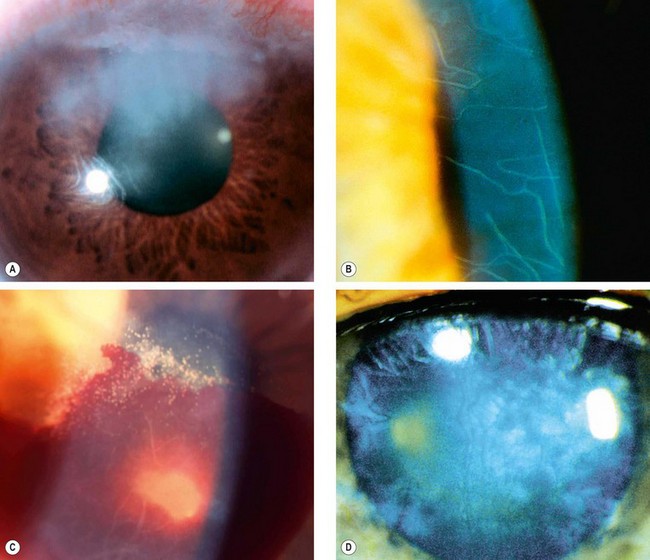

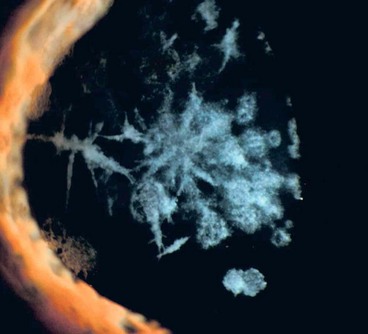

Fig. 6.10 Fungal keratitis. (A) Candida keratitis; (B) filamentous keratitis with satellite lesions and a small hypopyon; (C) Gram-stained Candida spp shows pseudohyphae; (D) corneal smear stained with Grocott hexamine silver shows Aspergillus spp.

(Courtesy of S Tuft – figs A and B; Hart and Shears – fig C; J Harry and G Misson, from Clinical Ophthalmic Pathology, Butterworth-Heinemann 2001 – fig. D)

Investigations

Samples for laboratory examination should be acquired before commencing antifungal therapy.

Treatment

Improvement may be slow in comparison to bacterial infection.

Microsporidial keratitis

Pathogenesis

Microsporidia is a phylum of obligate intracellular one-celled parasites previously thought to be protozoa but recently reclassified as fungi. They rarely cause disease in the immunocompetent and until the advent of AIDS microsporidia were rarely pathogenic for humans. The most common general infection is enteritis and the most common ocular manifestation is keratoconjunctivitis.

Diagnosis

Treatment

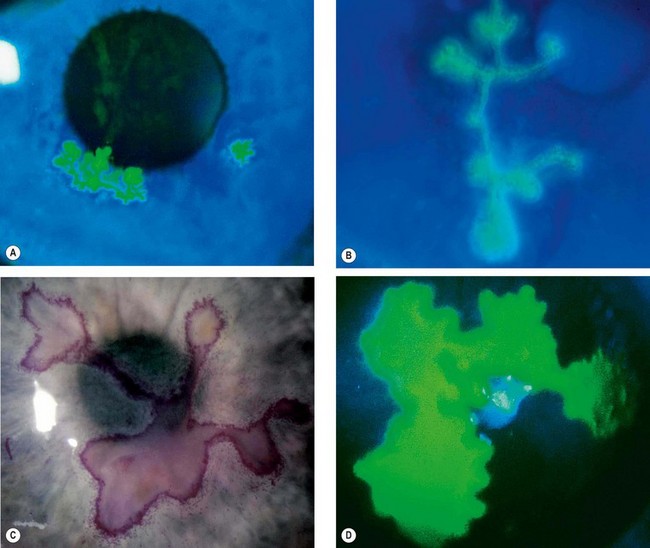

Herpes simplex keratitis

Introduction

Herpetic eye disease is the most common infectious cause of corneal blindness in developed countries. As many as 60% of corneal ulcers in developing countries may be the result of herpes simplex virus and 10 million people worldwide may have herpetic eye disease.

Herpes simplex virus (HSV)

HSV is enveloped with a cuboidal capsule and has a linear double-stranded DNA genome. The two subtypes are HSV-1 and HSV-2, and these reside in almost all neuronal ganglia. HSV-1 causes infection above the waist (principally the face, lips and eyes), whereas HSV-2 causes venereally-acquired infection (genital herpes). Rarely HSV-2 may be transmitted to the eye through infected secretions, either venereally or at birth (neonatal conjunctivitis). HSV transmission is facilitated in conditions of crowding and poor hygiene.

Primary infection

Primary infection, without previous viral exposure, usually occurs in childhood and is spread by droplet transmission, or less frequently by direct inoculation. Due to protection bestowed by maternal antibodies, it is uncommon during the first 6 months of life, though occasionally severe neonatal systemic disease may occur. Most primary infections are subclinical or cause only mild fever, malaise and upper respiratory tract symptoms. Blepharitis and follicular conjunctivitis may develop but are usually mild and self-limited. Treatment, if necessary, involves topical aciclovir ointment for the eye and/or cream for skin lesions.

Recurrent infection

Recurrent disease (reactivation in the presence of cellular and humoral immunity) occurs as follows:

Epithelial keratitis

Clinical features

Epithelial (dendritic or geographic) keratitis is associated with active virus replication.

Treatment

Treatment of HSV disease is predominantly with nucleoside (purine or pyrimidine) analogues that are incorporated to form abnormal viral DNA. Aciclovir, ganciclovir and trifluridine have low toxicity and approximately equivalent effect. Idoxuridine and vidarabine are older drugs which are probably less effective and more toxic to the epithelium but are still used in regions where low cost is critical. The majority of dendritic ulcers will eventually heal spontaneously without treatment, though scarring and vascularization may be more significant with more prolonged disease.

Disciform keratitis

The exact aetiology of disciform keratitis (endotheliitis) is controversial. It may be active HSV infection of keratocytes or endothelium, or a hypersensitivity reaction to viral antigen in the cornea. A clear past history of epithelial ulceration is not always present.

Clinical features

Treatment

Treatment is set out below, but in practice the regimen should be tailored individually. Careful monitoring and adequate treatment, dependent on severity of inflammation, is critical to minimize progression of scarring. Patients should be cautioned to seek treatment at the first suggestion of recurrence, though minimal inflammation may not warrant treatment or can be addressed with cycloplegia alone.

Necrotizing stromal keratitis

This rare condition is thought to result from active viral replication within the stroma, though immune-mediated inflammation plays a significant role. It may be difficult to distinguish clinically from severe disciform keratitis and there may be a spectrum of disease, including overlap with neurotrophic keratopathy. One should be wary that a similar clinical picture may be caused by other infections.

Neurotrophic ulceration

Neurotrophic ulceration is caused by failure of re-epithelialization resulting from corneal anaesthesia, often exacerbated by other factors such as drug toxicity.

Other considerations

Prophylaxis

Long-term daily oral aciclovir reduces the rate of recurrence of epithelial and stromal keratitis by about 50% and is usually well tolerated. Prophylaxis should be considered in patients with frequent debilitating recurrences, particularly if bilateral or involving an only eye. The standard daily dose of aciclovir is 400 mg b.d. but if necessary a higher dose can be tried. Oral valaciclovir (500 mg once daily) or famciclovir are alternatives. The prophylactic effect decreases or disappears when the drug is stopped.

Complications

Keratoplasty

Recurrence of herpetic eye disease and rejection threaten the survival of corneal grafts. A trial of a rigid contact lens is often worthwhile prior to committing to surgery.

Herpes zoster ophthalmicus

Introduction

Pathogenesis

The varicella-zoster virus (VZV) causes both chickenpox (varicella) and shingles (herpes zoster). VZV belongs to the same subfamily of the herpes virus group as the HSV and the two viruses are morphologically identical but antigenically distinct. After an episode of chickenpox the VZV travels in a retrograde manner to the dorsal root and cranial nerve sensory ganglia, where it may remain dormant for decades, with reactivation thought to occur after VZV-specific cell-mediated immunity has faded. Herpes zoster ophthalmicus (HZO) describes shingles involving the dermatome supplied by the ophthalmic division of the 5th cranial (trigeminal) nerve. Mild ocular involvement can also occasionally occur when the disease affects the maxillary division alone.

Mechanisms of ocular involvement

Risk of ocular involvement

Acute shingles

General features

Treatment

Eye disease

Acute eye disease

Chronic eye disease

Post-herpetic neuralgia

Post-herpetic neuralgia is defined as pain that persists for more than one month after the rash has healed. It develops in up to 75% of patients over 70 years of age. Pain may be constant or intermittent, worse at night and aggravated by minor stimuli (allodynia), touch and heat. It generally improves slowly with time with only 2% of patients affected after 5 years. Neuralgia can impair the quality of life, and may lead to depression of sufficient severity to present the danger of suicide. Patients severely affected should be referred to a specialist pain clinic. Treatment involves the following:

Interstitial keratitis

Pathogenesis

Interstitial keratitis (IK) is an inflammation of the corneal stroma without primary involvement of the epithelium or endothelium. In most cases, the inflammation is an immune-mediated process triggered by an appropriate antigen. Syphilis-related (usually congenital and sometimes acquired) IK is the archetype, but no longer the most common in developed countries. Others include herpetic keratitis (including chickenpox), other viral infections, tuberculosis, sarcoidosis, Cogan syndrome (see below), and a range of other infections.

Syphilitic IK

Syphilis is caused by the spirochaete Treponema pallidum. The organism is very fragile, easily eliminated by drying or heating, and does not survive in culture.

Acquired infection

Congenital infection

Infection of the fetus can occur transplacentally. It may lead to stillbirth, be subclinical, or can result in a range of clinical features. It is important to diagnose and treat infants as early as possible.

Syphilitic IK

Cogan syndrome

Cogan syndrome is a rare systemic autoimmune vasculitis characterized by intraocular inflammation and vestibuloauditory dysfunction (particularly neurosensory deafness but also tinnitus and vertigo) developing within months of each other. The disease primarily occurs in young adults, with both sexes affected equally.

Protozoan keratitis

Acanthamoeba

Pathogenesis

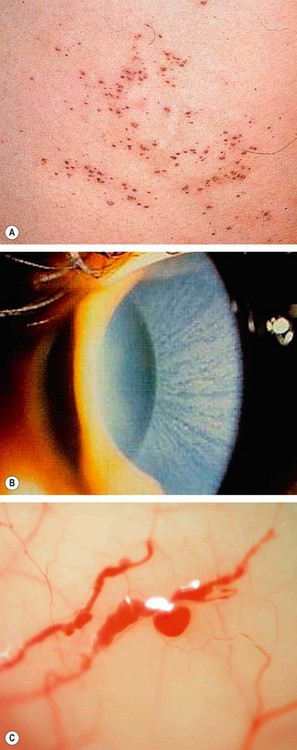

Acanthamoeba spp. are ubiquitous free-living protozoa commonly found in soil, fresh or brackish water and the upper respiratory tract. The cystic form (Fig. 6.24A) is highly resilient. Under appropriate environmental conditions, the cysts turn into trophozoites, which produce a variety of enzymes, leading to tissue penetration and destruction. In developed countries keratitis is most frequently associated with contact lens wear, especially if tap water is used for rinsing.

Diagnosis

Early misdiagnosis as herpes simplex keratitis is relatively common. In advanced disease the possibility of fungal keratitis should be remembered.

Treatment

It is important to maintain a high index of suspicion for Acanthamoeba infection in any patient who responds incompletely to antibacterial therapy. The outcome is very much better if treatment is started within 4 weeks of onset of symptoms.

Onchocerciasis

Onchocerciasis (‘river blindness’) is caused by infestation with the parasitic helminth Onchocerca volvulus. It is the second most common infectious cause of blindness in the world and is endemic in areas of Africa, with foci elsewhere.

Bacterial hypersensitivity-mediated corneal disease

Marginal keratitis

Pathogenesis

Marginal keratitis is probably caused by a hypersensitivity reaction against staphylococcal exotoxins and cell wall proteins with deposition of antigen-antibody complexes in the peripheral cornea (antigen diffusing from the tear film, antibody from the blood vessels) with a secondary lymphocytic infiltration. The lesions are culture negative but S. aureus can frequently be isolated from the lid margins.

Diagnosis

Treatment

Coexisting chronic blepharitis should be treated if troublesome, or if marginal keratitis is frequently recurrent. Treatment of symptomatic disease is with a weak topical steroid such as prednisolone 0.5% q.i.d. for 1 week, sometimes combined (often in a fixed combination) with a topical antibiotic. An extended course of an oral tetracycline (erythromycin in children) may rarely be required for troublesome recurrent disease.

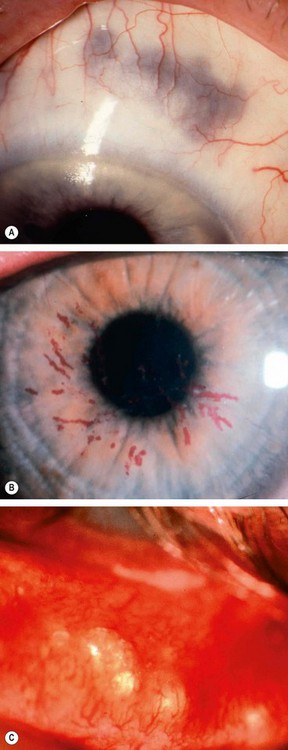

Phlyctenulosis

Pathogenesis

Phlyctenulosis is usually a self-limiting disease although rarely it may be severe and even blinding. Most cases seen in developed countries are the result of a presumed delayed hypersensitivity reaction to staphylococcal antigen; the most common systemic association is rosacea. However, in developing countries the majority are associated with tuberculosis or helminthic infestation.

Diagnosis

Rosacea

Pathogenesis

Rosacea is a common, idiopathic, chronic dermatosis involving the sun-exposed skin of the face and upper neck. Ocular complications develop in 6–18% of patients. The aetiology of rosacea is uncertain, and it is likely that there is interaction of several different factors. Vascular factors, including the vasodilatation response, are thought to be important. Papule and pustule formation may be precipitated by lipases secreted by S. epidermidis. Lipases break down the wax and sterol esters secreted by the meibomian glands to release inflammatory free fatty acids. Follicular infection with Demodex mites may have an aetiological role, although these are almost universally present in healthy older adults.

General features

In contrast to acne vulgaris comedones (blackheads or whiteheads) are absent.

Ocular rosacea

Severe peripheral corneal ulceration

Mooren ulcer

Pathogenesis

Mooren ulcer is a rare, idiopathic disease characterized by progressive circumferential peripheral, stromal ulceration with later central spread. There are two types: the first affects predominantly older patients, often in only one eye, and usually responds well to medical therapy; the second is more aggressive and less responsive to treatment. The latter may be bilateral and associated with severe pain, and tends to occur in younger patients, including widespread reports in young men from the Indian subcontinent. An autoimmune mechanism is thought to be responsible for Mooren ulcer, and in at least some (secondary) cases, there is an evident history of a corneal insult such as surgery, trauma or infection which is presumed to act as a trigger in susceptible individuals. These secondary cases tend to fall within the ‘limited’ category. It is critical to attempt to rule out associated systemic autoimmune disease (see below) before concluding the diagnosis to be Mooren ulcer.

Diagnosis

Treatment

The clinical course varies dependent on whether the patient appears to fall within the ‘limited’ or ‘relentless’ categories. In the second group, the outlook for vision tends to be very poor even with treatment.

Peripheral ulcerative keratitis associated with systemic autoimmune disease

Pathogenesis

Peripheral ulcerative keratitis (PUK) may precede or follow the onset of systemic disease. Severe peripheral corneal infiltration, ulceration or thinning unexplained by evident ocular disease should prompt a search for an associated systemic collagen vascular disorder (see below). In patients with an underlying autoimmune disease there is immune complex deposition in peripheral cornea. Diseased epithelium, keratocytes and recruited inflammatory cells may result in the release of matrix metalloproteinases that degrade collagen and the extracellular matrix. Autoantibodies may target sites in the corneal epithelium.

Clinical features

Associated systemic disease

Treatment

PUK associated with a potentially life-threatening systemic vasculitis must be treated with systemic immunosuppressive agents in collaboration with a rheumatologist.

Terrien marginal degeneration

Terrien disease is an uncommon idiopathic thinning of the peripheral cornea. Although usually categorized as a degeneration, some cases are associated with episodes of episcleritis or scleritis. About 75% of affected patients are male and the condition is usually bilateral although involvement may be symmetrical.

Diagnosis

Treatment

Neurotrophic keratopathy

Pathogenesis

Neurotrophic keratopathy occurs when there is loss of the trigeminal innervation to the cornea resulting in partial or complete anaesthesia.

The loss of neural influences results in intracellular oedema, exfoliation of epithelial cells, impairment of epithelial healing and loss of goblet cells, culminating in epithelial breakdown and persistent ulceration. Loss of acetylcholine, substance P, and growth factors from the epithelium appear to be important.

Causes

Diagnosis

The severity of signs can vary during the course of disease. Some patients develop serious lesions early while others only develop problems after many years.

Treatment

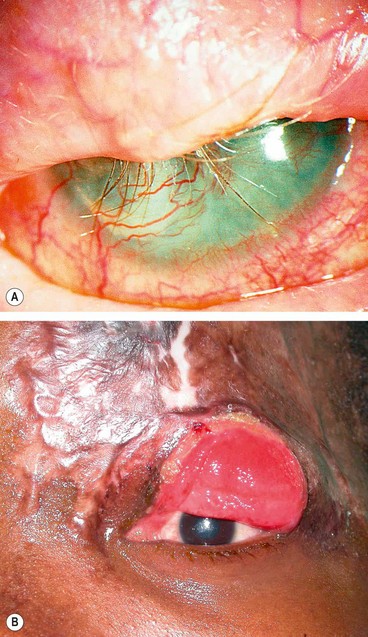

Exposure keratopathy

Pathogenesis

Exposure keratopathy is the result of incomplete lid closure (lagophthalmos). Lagophthalmos may only be present on blinking or gentle lid closure, but absent on forced lid closure. The result is drying of the cornea despite normal tear production.

Causes

Diagnosis

Miscellaneous keratopathy

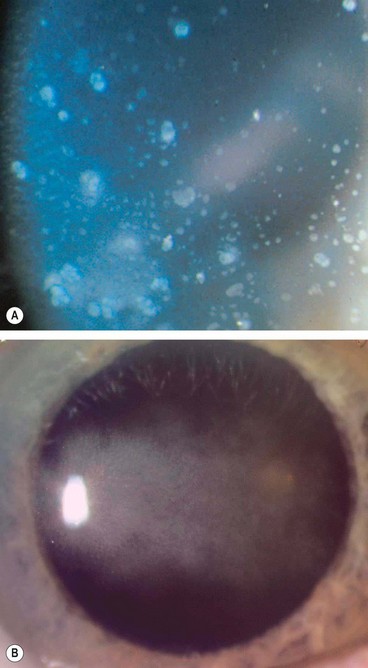

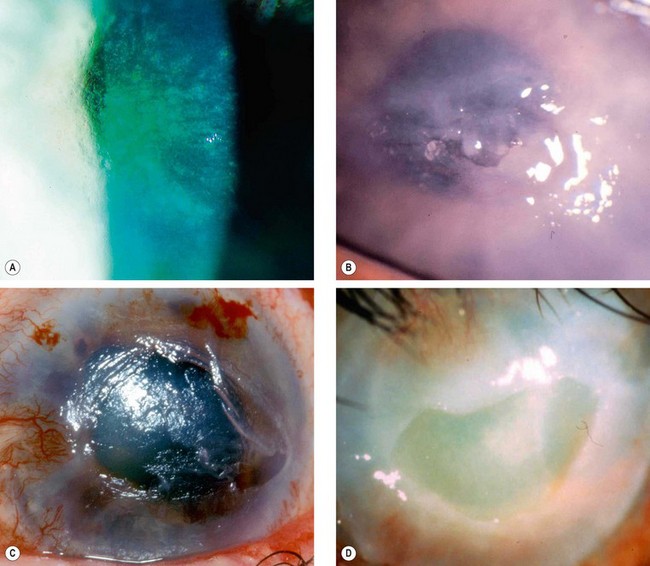

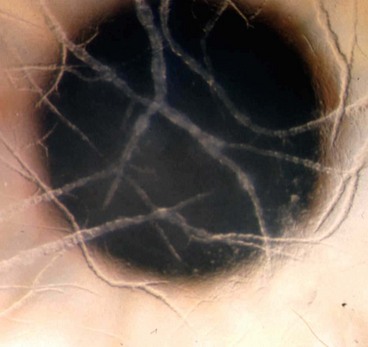

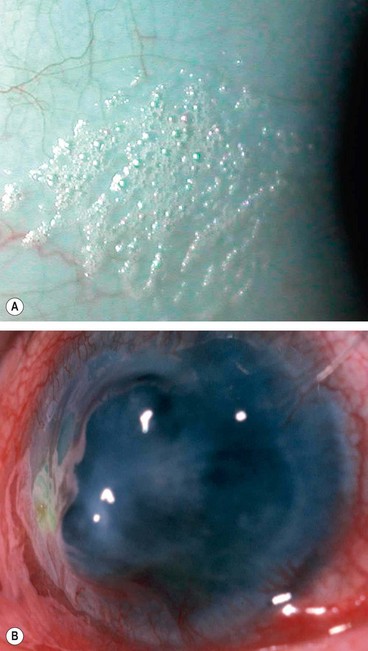

Infectious crystalline keratopathy

Pathogenesis

Infectious crystalline keratopathy is a rare, indolent infection usually associated with long-term topical steroid therapy where there has been an epithelial defect, most frequently following penetrating keratoplasty. S. viridans is most commonly isolated, although numerous other bacteria and fungi have been implicated.

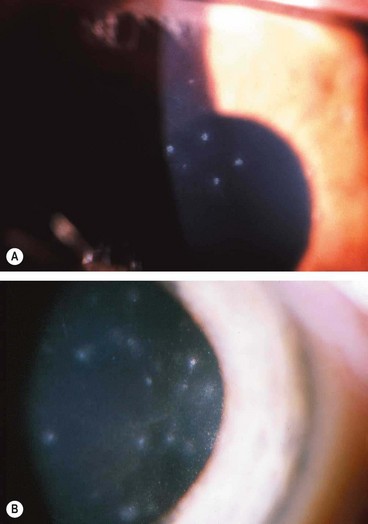

Thygeson superficial punctate keratitis

Thygeson superficial punctate keratitis is an uncommon, usually bilateral, idiopathic condition characterized by exacerbations and remissions. It most commonly affects young adults but may occur at any age and recurrences can continue for decades.

Diagnosis

Treatment

Filamentary keratopathy

Pathogenesis

Filamentary keratopathy is a common condition that can cause considerable discomfort. It is thought that a loose area of epithelium acts as a focus for deposition of mucus and cellular debris. The causes are shown in Table 6.6.

Table 6.6 Causes of filamentary keratopathy

Diagnosis

Recurrent corneal epithelial erosions

Pathogenesis

Recurrent corneal epithelial erosion is the tendency for minor trauma to precipitate significant corneal epithelial disturbances. The condition is caused by an abnormally weak attachment between the basal cells of the corneal epithelium and their basement membrane. Minor trauma, such as eyelid-corneal interaction during sleep, can be sufficient to detach the epithelium. Erosions may be associated with previous trauma or corneal surgery, and with certain corneal dystrophies (see below).

Diagnosis

Xerophthalmia

Pathogenesis

Vitamin A is essential for the maintenance of the body’s epithelial surfaces, for immune function and for the synthesis of retinal photoreceptor proteins. Xerophthalmia refers to the spectrum of ocular disease caused by lack of vitamin A, and is a late manifestation of severe deficiency. Lack of vitamin A in the diet may be caused by malnutrition, malabsorption, chronic alcoholism or by highly selective dieting. The risk in infants is increased if their mothers are malnourished and by coexisting diarrhoea or measles.

Diagnosis

Fig. 6.39 Xerophthalmia. (A) Bitot spot; (B) keratomalacia and perforation

(Courtesy of N Rogers – fig. A; S Kumar Puri – fig. B)

Table 6.7 WHO grading of Xerophthalmia

Treatment

Keratomalacia is an indicator of very severe vitamin A deficiency and should be treated as a medical emergency due to the risk of death, particularly in infants.

Corneal ectasias

Keratoconus

Pathogenesis

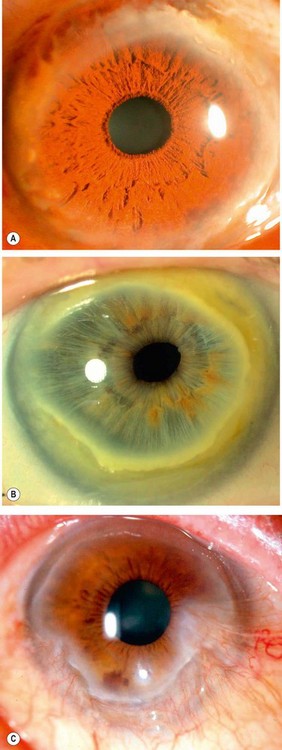

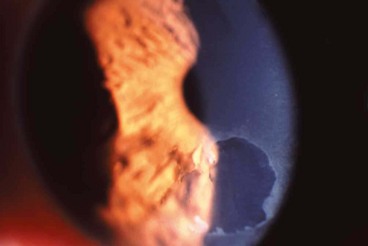

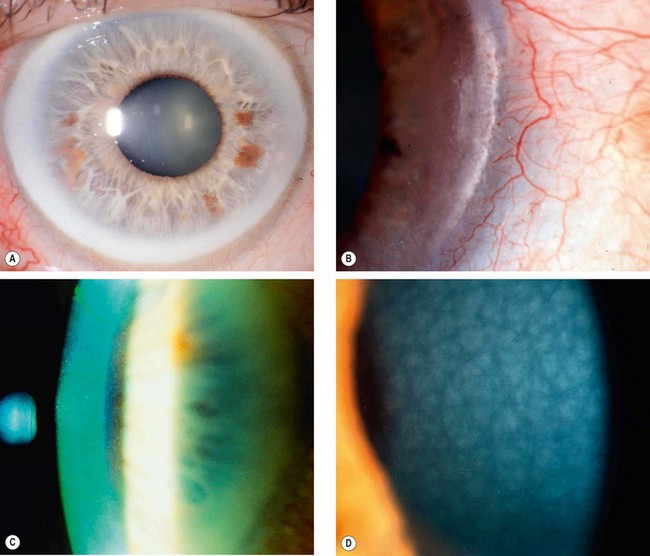

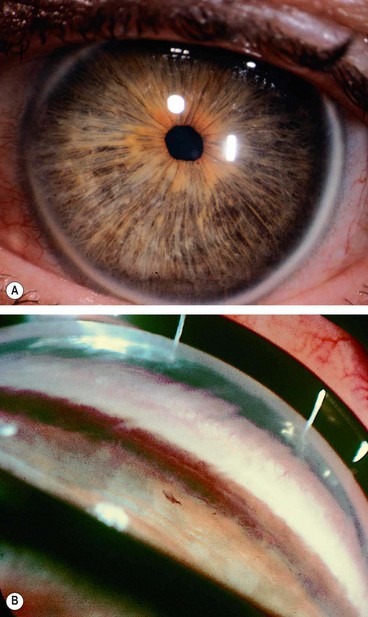

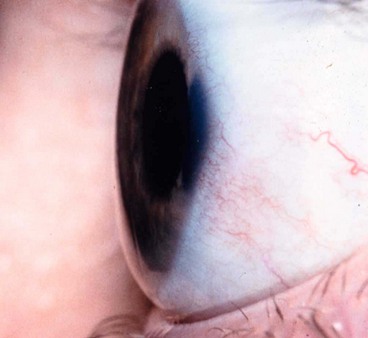

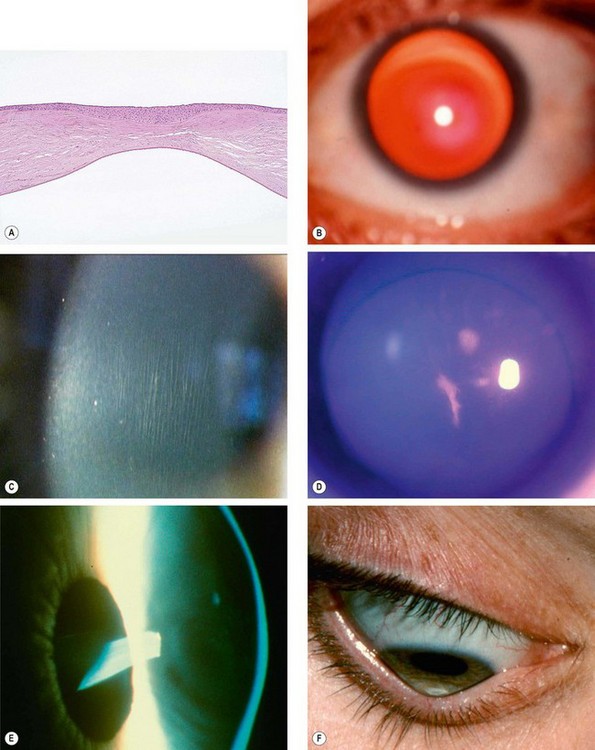

Keratoconus is a progressive disorder in which the cornea assumes a conical shape secondary to stromal thinning and protrusion (Fig. 6.40A). Both eyes are affected, at least on topographical imaging, in almost all cases. The role of heredity has not been clearly defined and most patients do not have a positive family history. Offspring appear to be affected in only about 10% of cases and autosomal dominant transmission with incomplete penetrance has been proposed.

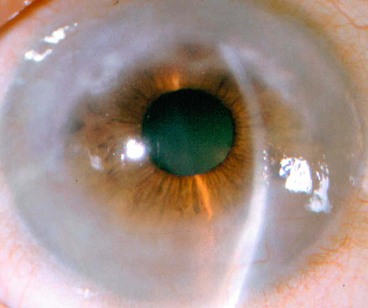

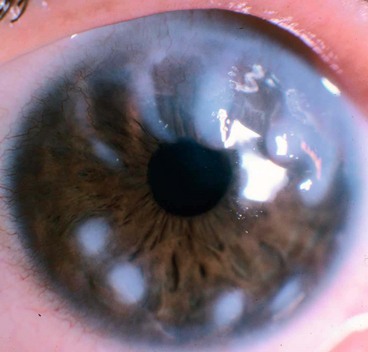

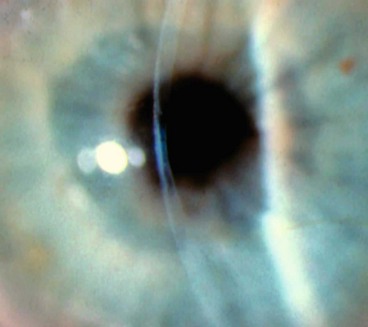

Fig. 6.40 Keratoconus. (A) Histology shows central stromal thinning; (B) ‘oil-droplet’ red reflex; (C) Vogt striae; (D) Fleischer ring; (E) advanced thinning; (F) Munson sign

(Courtesy of J Harry and G Misson, from Clinical Ophthalmic Pathology, Butterworth-Heinemann 2001 – fig. A; M Leyland – fig. C; S Fogla – fig. D; R Bates – fig. E)

Presentation

Presentation is typically during puberty with unilateral impairment of vision due to progressive myopia and astigmatism, which subsequently becomes irregular. As a result of the asymmetrical nature of the condition, the fellow eye usually has normal vision with negligible astigmatism at presentation. Approximately 50% of normal fellow eyes will progress to keratoconus within 16 years; the greatest risk is during the first 6 years of onset.

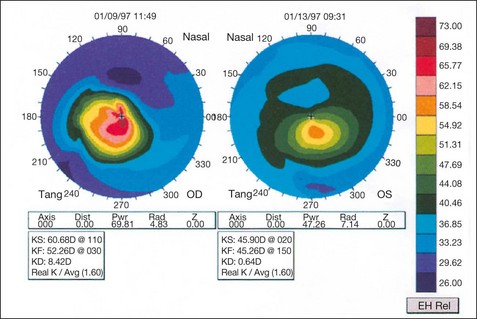

Diagnosis

The hallmark of keratoconus is central or paracentral stromal thinning, accompanied by apical protrusion and irregular astigmatism. It can be graded by keratometry according to severity as mild (<48 D), moderate (48–54 D) and severe (>54 D).

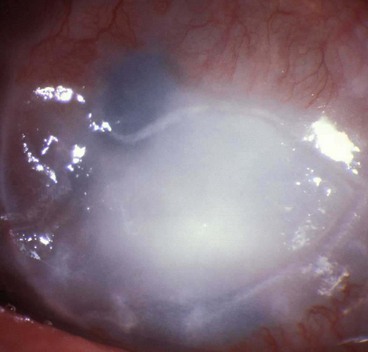

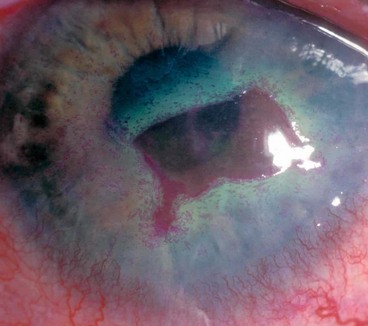

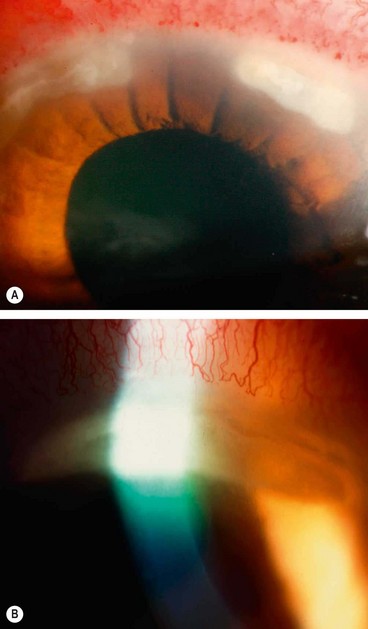

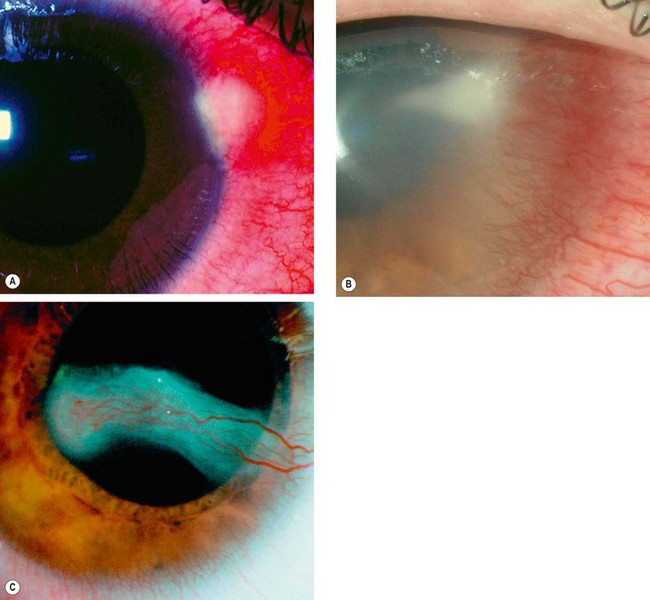

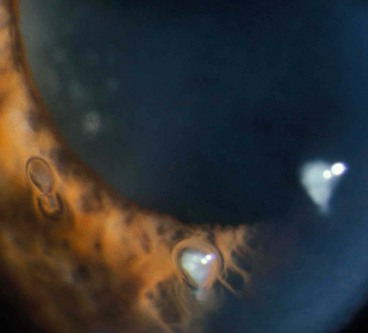

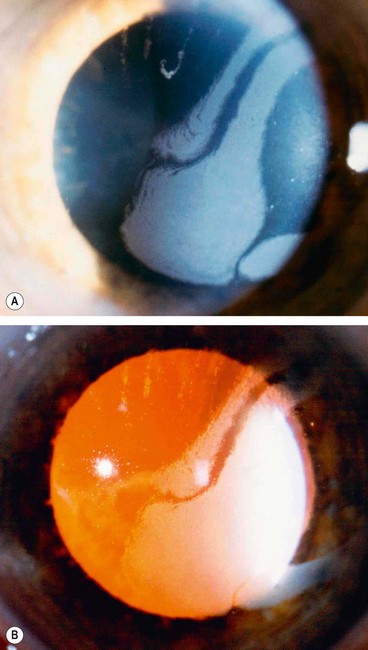

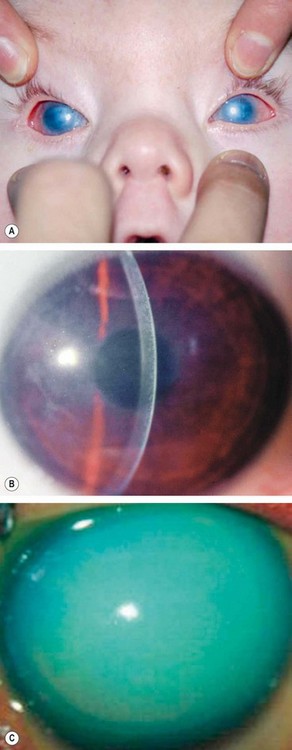

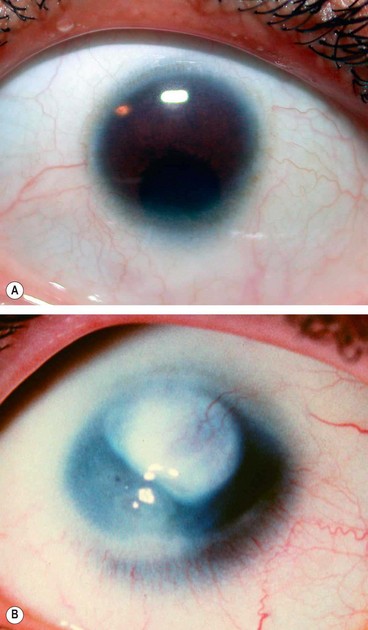

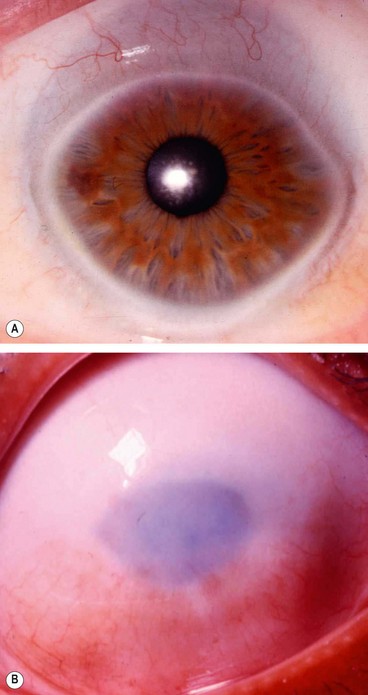

Acute hydrops

Acute hydrops is caused by a rupture in Descemet membrane that allows an influx of aqueous into the cornea (Fig. 6.42A and B). Although the break usually heals within 6–10 weeks and the corneal oedema clears, a variable amount of stromal scarring may develop (Fig. 6.42C). Acute episodes are initially treated with cycloplegia, hypertonic (5%) saline ointment and patching or a soft bandage contact lens. Healing may sometimes result in improved visual acuity as a result of scarring and flattening of the cornea.

Associations

Treatment

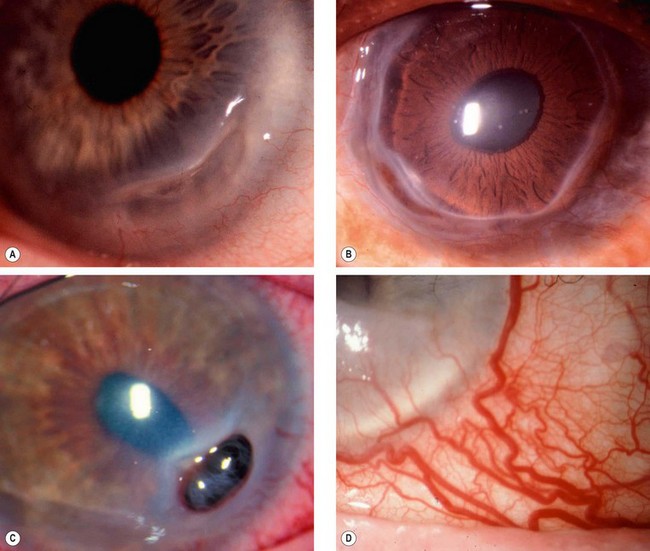

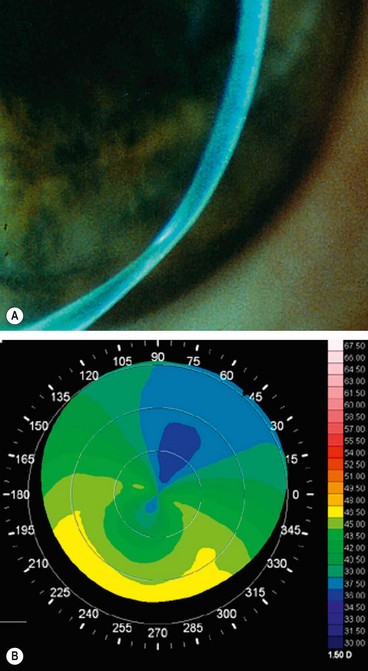

Pellucid marginal degeneration

Pellucid marginal degeneration is a rare progressive peripheral corneal thinning disorder, typically involving the inferior cornea. Occasionally it may co-exist with keratoconus and keratoglobus (see below). Like keratoconus, pellucid marginal degeneration is bilateral, although often asymmetrical.

Diagnosis

Treatment

Keratoglobus

Keratoglobus is an extremely rare congenital condition in which the entire cornea is abnormally thin. Possibly genetically related to keratoconus, it may be associated with Leber congenital amaurosis and blue sclera.

Corneal dystrophies

The corneal dystrophies are a group of progressive, usually bilateral, mostly genetically determined, non-inflammatory opacifying disorders. Based on biomicroscopical and histopathological features corneal dystrophies are classified into (a) epithelial, (b) Bowman layer, (c) stromal and (d) endothelial. Recent advances in molecular genetics have identified the responsible gene defects for most.

Epithelial dystrophies

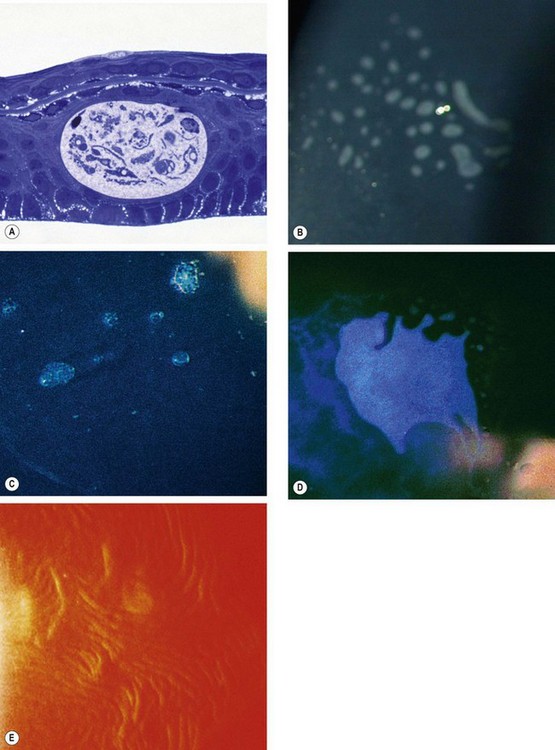

Cogan epithelial basement membrane dystrophy

Epithelial basement membrane dystrophy is the most common dystrophy seen in clinical practice. Despite this it is frequently misdiagnosed, principally due to its variable appearance.

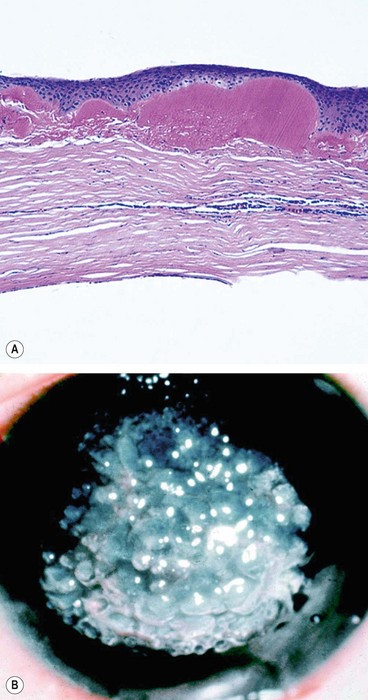

Fig. 6.45 Cogan epithelial basement membrane dystrophy. (A) Histology shows intraepithelial extension of the basement membrane above the intraepithelial cyst – toluidine blue stain; (B) dots; (C) microcysts; (D) map-like pattern; (E) fingerprint lines seen on retroillumination

(Courtesy of Krachmer, Mannis and Holland, from Cornea, Mosby 2005 – fig. E; J Harry and G Misson, from Clinical Ophthalmic Pathology, Butterworth-Heinemann 2001 – fig. A)

Meesmann epithelial dystrophy

Meesmann dystrophy is a very rare non-progressive abnormality of corneal epithelial metabolism, underlying which mutations in the genes encoding corneal epithelial keratins have been reported.

Bowman layer/anterior stromal dystrophies

Reis–Bücklers dystrophy (corneal dystrophy of Bowman layer, type I, CDB1, GCD type III)

This so-called ‘true’ form of Reis–Bücklers dystrophy may also be categorized as a form of granular stromal dystrophy (GCD type III).

Thiel–Behnke dystrophy (corneal dystrophy of Bowman layer, type II, CDB2, honeycomb-shaped corneal dystrophy)

Stromal dystrophies

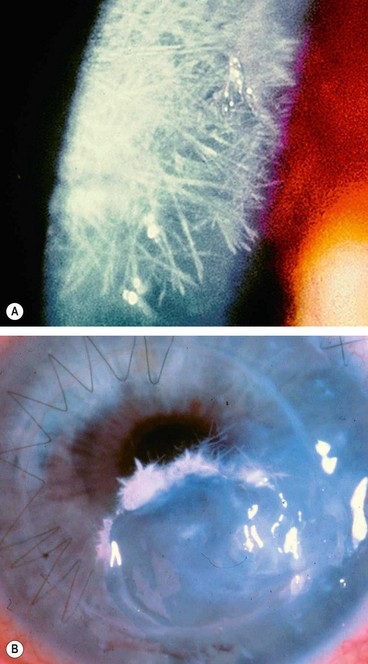

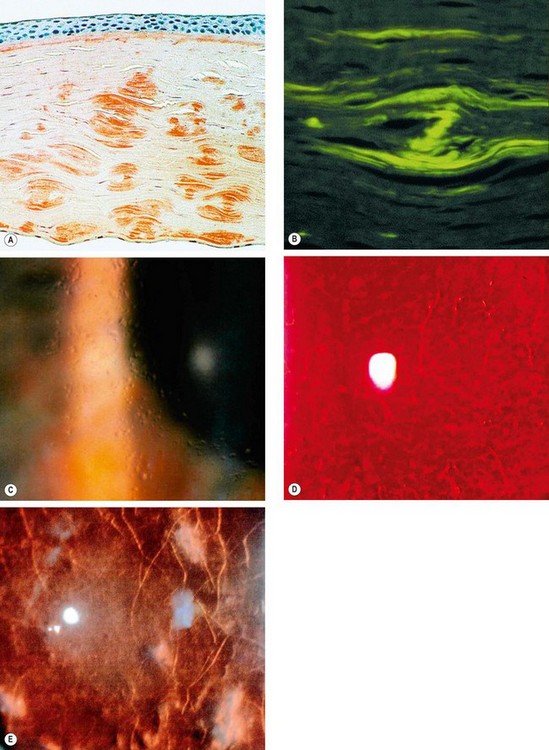

Lattice corneal dystrophy type I (LCD1, Biber–Haab–Dimmer)

Fig. 6.51 Lattice dystrophy type 1. (A) Histology shows amyloid staining with Congo red; (B) green birefringence of amyloid when viewed with polarized light; (C) glassy dots in the anterior stroma; (D) fine lattice lines; (E) stromal haze

(Courtesy of J Harry – fig. A; J Harry and G Misson, from Clinical Ophthalmic Pathology, Butterworth-Heinemann 2001 – fig. B; D Smerdon – fig. D).

Lattice corneal dystrophy type II (LCD2, Finnish type amyloidosis, Meretoja syndrome, amyloid cranial neuropathy with lattice corneal dystrophy)

Lattice corneal dystrophy type IIIA

Lattice type IIIA is characterized by thick rope-like bands of deposited amyloid (Fig. 6.52). The age of onset is late (70–90 years) and inheritance AD (gene TGFB1).

Gelatinous drop-like dystrophy (Japanese type amyloid corneal dystrophy)

This is a rare disorder mainly affecting Japanese patients.

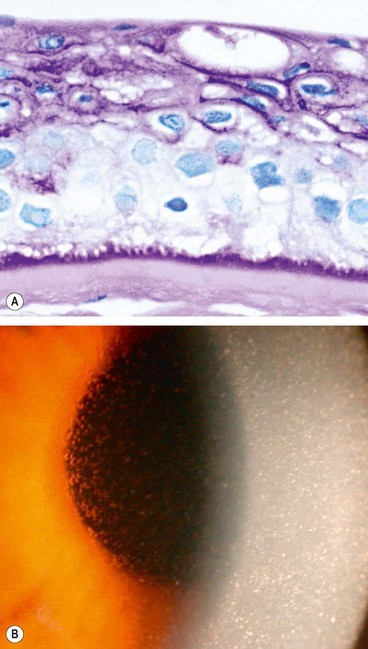

Fig. 6.53 Gelatinous drop-like dystrophy; (A) Histology shows irregular anterior stromal amyloid deposits; (B) clinical appearance

(Courtesy of J Harry and G Misson, from Clinical Ophthalmic Pathology, Butterworth-Heinemann 2001 – fig. A; Krachmer, Mannis and Holland, from Cornea, Mosby 2005 – fig. B)

Granular corneal dystrophy type I (GCD1, Groenouw type I)

Granular corneal dystrophy type II (GCD2, Avellino, combined granular-lattice dystrophy)

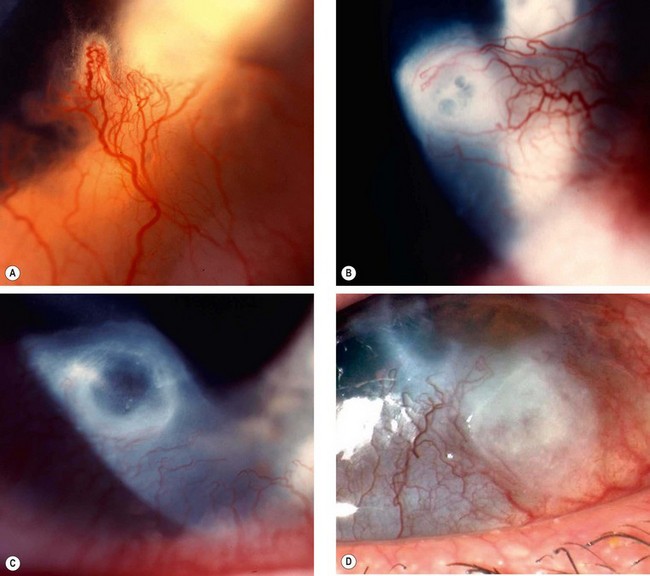

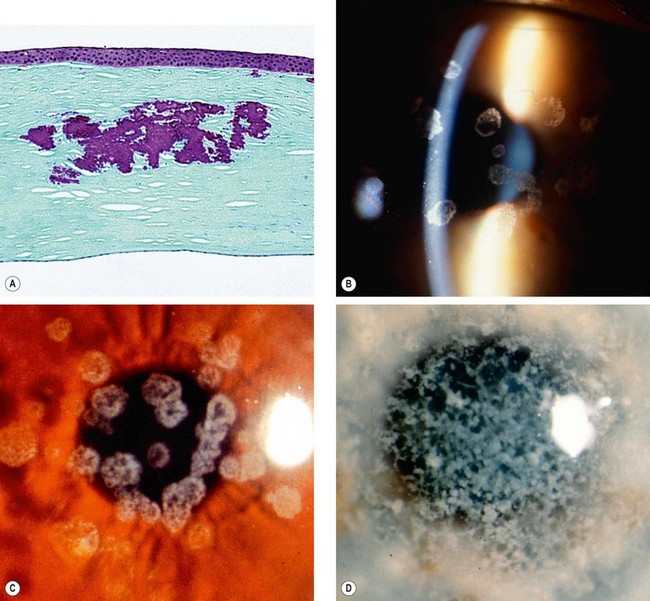

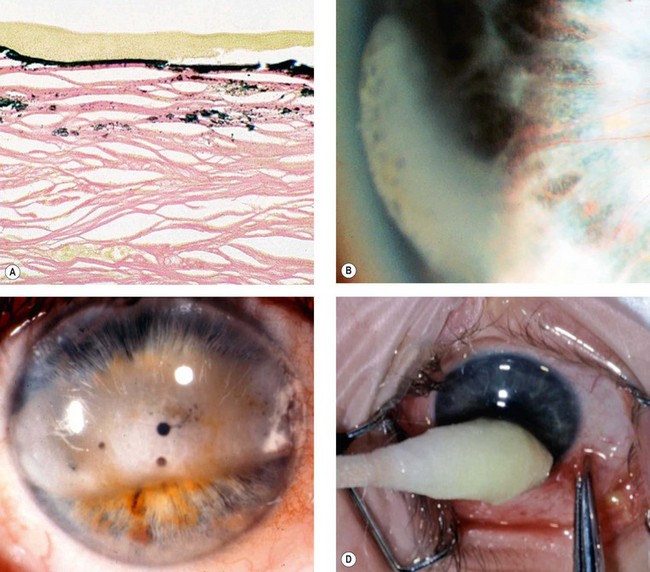

Macular dystrophy (Groenouw type II)

Macular dystrophy is the least common stromal dystrophy, in which a systemic inborn error of keratan sulphate metabolism seems to have only corneal manifestations. It has been divided into clinically indistinguishable types I, IA and II depending on the presence or absence of antigenic keratan sulphate in the serum and cornea; these have been shown to be due to mutations in the same sulfotransferase gene (CHST6).

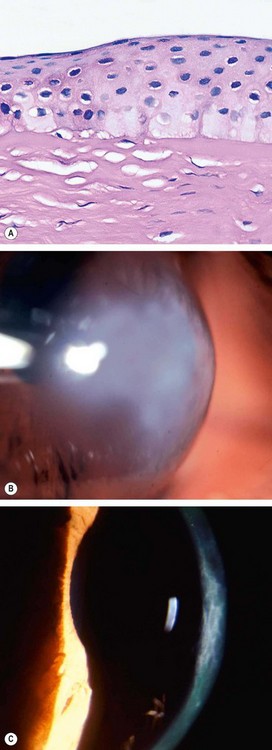

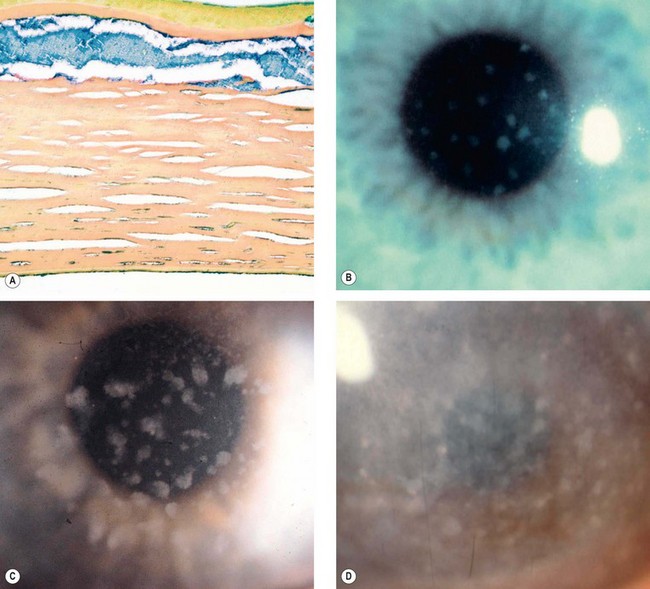

Fig. 6.56 Macular dystrophy. (A) Histology shows deposits of abnormal glycosaminoglycans that appear blue with colloidal iron stain; (B) poorly delineated deposits; (C) increase in size and stromal haze; (D) extensive involvement

(Courtesy of R Ridgway – figs. B, C and D; J Harry and G Misson, from Clinical Ophthalmic Pathology, Butterworth-Heinemann, 2001 – fig. A)

François central cloudy dystrophy

Endothelial dystrophies

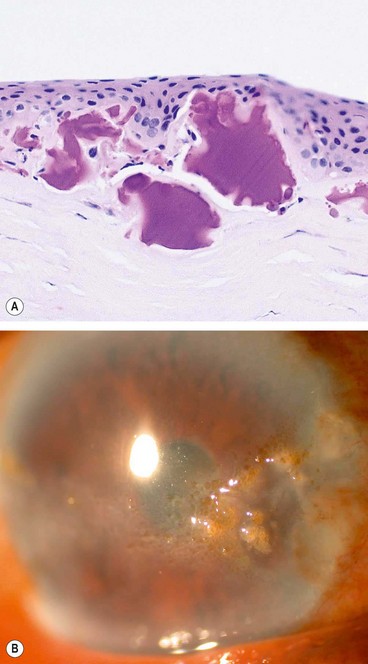

Fuchs endothelial dystrophy

Fuchs endothelial dystrophy (FED) is characterized by bilateral accelerated endothelial cell loss. It is more common in women and is associated with a slightly increased prevalence of open-angle glaucoma.

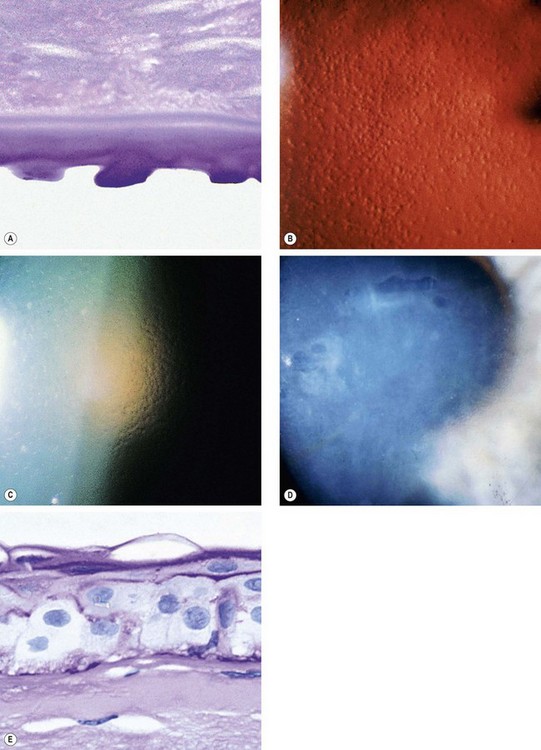

Fig. 6.58 Fuchs endothelial dystrophy. (A) Histology of cornea guttata shows irregular excrescences of Descemet membrane – PAS stain; (B) cornea guttata seen on specular reflection; (C) ‘beaten-bronze’ endothelium; (D) bullous keratopathy; (E) histology shows severe epithelial oedema with surface bullae – PAS stain

(Courtesy of J Harry – figs A and E; W Lisch – fig. D)

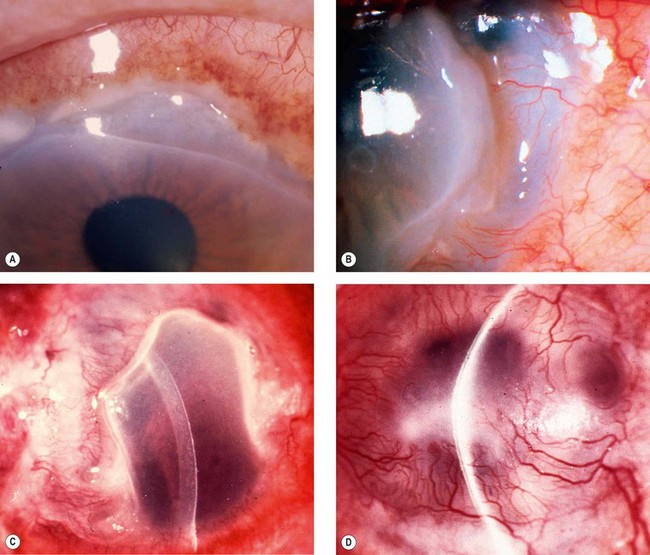

Posterior polymorphous dystrophy

Posterior polymorphous corneal dystrophy (PPCD) is a rare, innocuous and asymptomatic condition in which corneal endothelial cells display characteristics similar to epithelium. There are three forms, PPCD1-3, each caused by mutations in different genes.

Congenital hereditary endothelial dystrophy

Congenital hereditary endothelial dystrophy (CHED) is a rare dystrophy in which there is focal or generalized absence of corneal endothelium. There are two main forms, CHED1 and CHED2, the latter being more severe.

Corneal degenerations

Age-related degenerations

Arcus senilis

Vogt limbal girdle

Vogt limbal girdle is a common innocuous condition which is more common in women and is present in up to 60% of individuals over 40 years of age.

Cornea farinata

Cornea farinata is a visually insignificant condition characterized by bilateral, minute, flour-like deposits in the deep stroma, most prominent centrally (Fig. 6.61C).

Crocodile shagreen

Crocodile shagreen is characterized by asymptomatic, greyish-white, polygonal stromal opacities separated by relatively clear spaces (Fig. 6.61D). The opacities most frequently involve the anterior two-thirds of the stroma (anterior crocodile shagreen), although on occasion they may be found more posteriorly (posterior crocodile shagreen). It resembles the central cloudy dystrophy of François (see Fig. 6.57).

Lipid keratopathy

Band keratopathy

Spheroidal degeneration

Metabolic keratopathies

Cystinosis

Mucopolysaccharidoses

Wilson disease

Lecithin-cholesterol-acyltransferase deficiency (Norum disease)

This is an AR disease characterized by hyperlipidaemia, early atheroma, anaemia and renal disease. Keratopathy is characterized by numerous minute greyish dots throughout the stroma, often concentrated in the periphery in an arcus-like configuration (Fig. 6.66D).

Immunoprotein deposits

Fabry disease (angiokeratoma corporis diffusum)

Tyrosinaemia type 2 (Richner–Hanhart syndrome)

Contact lenses

Therapeutic uses

The risks of fitting a contact lens to an already compromised eye are greater than with lens wear for cosmetic reasons. The balance between benefit and risk should therefore be carefully considered, and close monitoring is vital to ensure early diagnosis and treatment of complications. The choice of lens type is dictated by the nature of ocular pathology.

Optical

Optical indications are aimed at improving visual acuity when this cannot be achieved by spectacles in the following conditions:

Promotion of epithelial healing

Pain relief

Preservation of corneal integrity

Complications

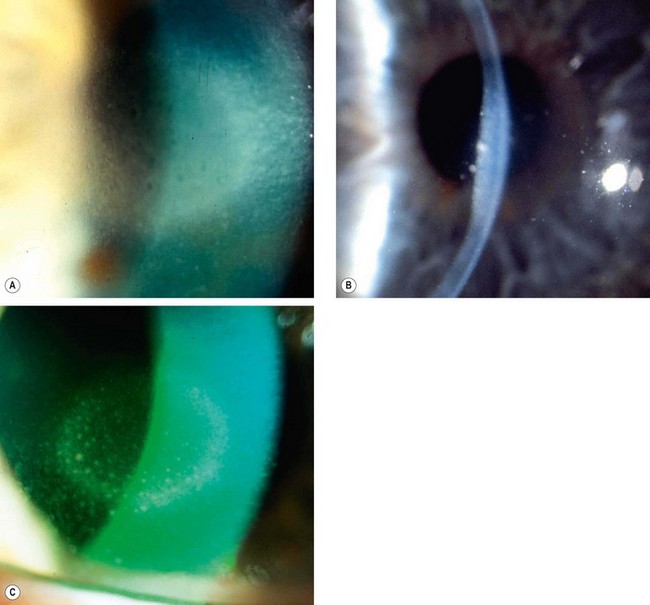

Mechanical and hypoxic keratitis

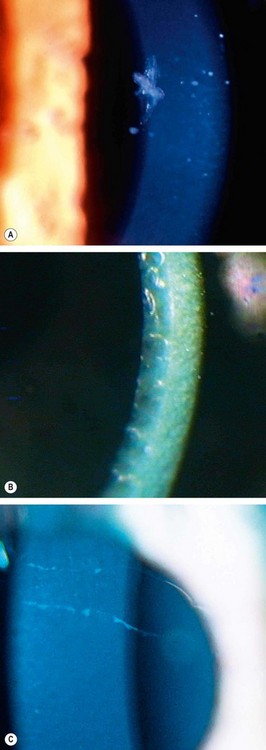

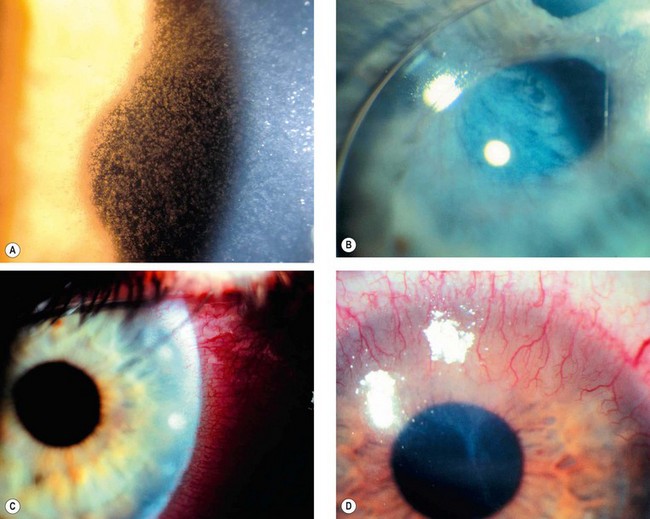

Fig. 6.69 Complications of contact lens wear. (A) Epithelial microcysts from acute hypoxia; (B) lipid deposition from chronic hypoxia; (C) marginal infiltrates in immune response keratitis; (D) vascularization and scarring in chronic toxic keratitis

(Courtesy of S Tuft – figs A and B; J Dart – fig. D)

Immune response keratitis

Toxic keratitis

Suppurative keratitis

Contact lens wear is the greatest risk factor for the development of bacterial keratitis; the risk is probably least for rigid contact lenses. Bacteria in the tear film are normally unable to bind to the corneal epithelium, but following an abrasion and in association with hypoxia, bacteria can attach and penetrate the epithelium with the potential to cause infection. Bacteria and protozoa may also be introduced onto the corneal surface by poor lens hygiene or the use of tap water to rinse lenses.

Congenital anomalies of the cornea and globe

Microcornea

Microcornea is a rare AD unilateral or bilateral condition.

Megalocornea

Megalocornea is a rare, bilateral, non-progressive condition thought to be due to defective growth of the optic cup.

Sclerocornea

Sclerocornea is a very rare, usually bilateral, condition that may be associated with cornea plana (see below).

Cornea plana

This is a rare bilateral condition.

Keratectasia

Keratectasia is a very rare, usually unilateral, condition thought to be the result of intrauterine keratitis and perforation. It is characterized by protuberance between the eyelids or a severely opacified and sometimes vascularized cornea (Fig. 6.74). It is often associated with raised intraocular pressure.

Posterior keratoconus

Posterior keratoconus is an uncommon, sporadic, unilateral, non-progressive increase in curvature of the posterior corneal surface. The anterior surface is normal and visual acuity unimpaired because of the similar refractive indices of the cornea and aqueous humour. Two types are recognized:

Microphthalmos

Microphthalmos is a developmental arrest of ocular growth, defined as total axial length (TAL) at least two standard deviations below age-similar controls. The TAL is reduced because of stunted growth of the anterior or posterior segment, or both. The condition is typically sporadic and may be unilateral or bilateral.