CHAPTER 59 The Flap Technique for Pocket Therapy

Several techniques can be used for the treatment of periodontal pockets. The periodontal flap is one of the most frequently employed procedures, particularly for moderate and deep pockets in posterior areas (see Chapter 52).

Overview

Flaps are used for pocket therapy to accomplish the following:

To fulfill these purposes, several flap techniques are available and in current use.

Technique for Access and Pocket Depth Reduction/Elimination

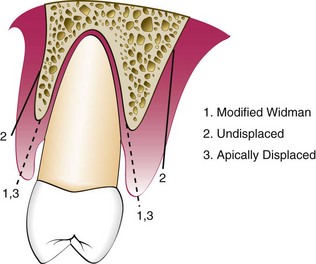

The three different categories of flap techniques used in periodontal flap surgery are (1) the modified Widman flap, (2) the undisplaced flap, and the (3) apically displaced flap.

The modified Widman flap facilitates instrumentation for root therapy. It does not attempt to reduce the pocket depth, but it does eliminate the pocket lining. The original intent of the surgery was to access the root surface for scaling and root planing. The objectives for the other two flap procedures, the nondisplaced flap and the apically displaced flap, include root surface access and the reduction or elimination of the pocket depth. The decision on which procedure to utilize depends on two important anatomic landmarks: the pocket depth and location of the mucogingival junction. These landmarks establish the presence and width of the attached gingiva, which is the basis for the decision.

The modified Widman flap has been described for exposing the root surfaces for meticulous instrumentation and for removal of the pocket lining.6 Again, it is not intended to eliminate or reduce pocket depth, except for the reduction that occurs in healing by tissue shrinkage.

The undisplaced (unrepositioned) flap improves accessibility for instrumentation, but it also removes the pocket wall, thereby reducing or eliminating the pocket. This is essentially an excisional procedure of the gingiva.

The apically displaced flap provides accessibility and eliminates the pocket, but it does the latter by apically positioning the soft tissue wall of the pocket.2 Therefore it preserves or increases the width of the attached gingiva by transforming the previously unattached keratinized pocket wall into attached tissue. This increase in the width of the attached gingiva is based on the apical shift of the mucogingival junction, which may include the apical displacement of the muscle attachments. A study made before and 18 years after apically displaced flaps failed to show a permanent relocation of the mucogingival junction.1

Incisions

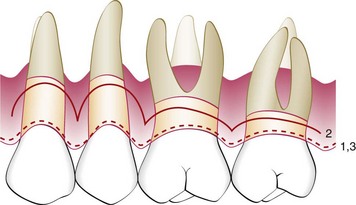

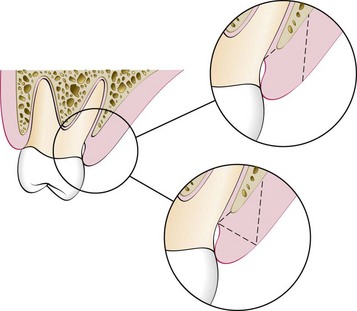

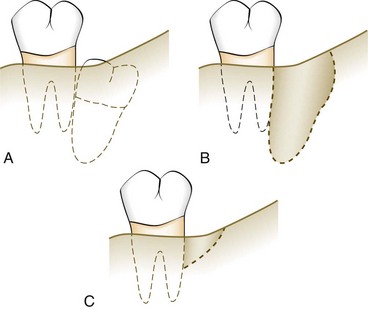

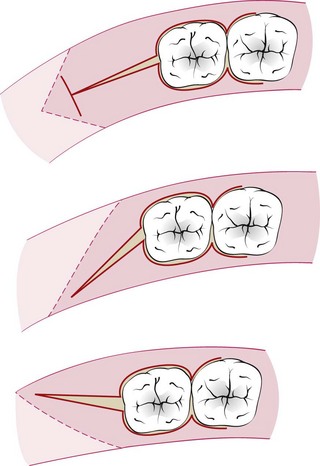

All three flap techniques just discussed use the basic incisions described in Chapter 57: the internal bevel incision, the crevicular incision, and the interdental incision. However, there are important variations in the way these incisions are performed for the different types of flaps (Figures 59-1 and 59-2). The internal beveled incision for the modified Widman flap closely follows the scalloped outline of the dentition to minimize the loss of the attached keratinized gingiva. This incision is made 1 to 2 mm from the teeth. The gingival margin is removed and the flap is reflected to gain access for root therapy.

The apically displaced flap technique is selected for cases that present a minimal amount of keratinized, attached gingiva. For this reason, the internal bevel incision should be made as close to the tooth as possible, 0.5 to 1.0 mm (see Figure 59-1). There is no need to determine where the bottom of the pocket is in relation to the incision for the apically displaced flap, as one would for the undisplaced flap. The flap is placed at the tooth-bone junction by apically displacing the flap. Its final position is not determined by the placement of the first incision.

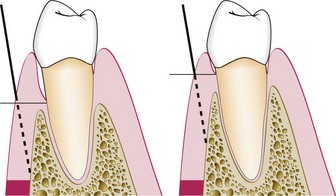

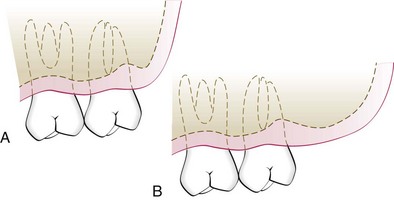

For the undisplaced flap, the internal bevel incision is initiated at or near a point just coronal to where the bottom of the pocket is projected on the outer surface of the gingiva (see Figure 59-1). This incision can be accomplished only if sufficient attached gingiva remains apical to the incision. Therefore the two anatomic landmarks, the pocket depth and the location of the mucogingival junction, must be considered to evaluate the amount of attached gingiva that will remain after the surgery has been completed. Because the pocket wall is not displaced apically, the initial incision should eliminate the pocket wall. Therefore an incision should not be made too close to the tooth because it will not eliminate the pocket wall and may result in the re-creation of the soft tissue pocket. If the tissue is too thick, the flap margin should be thinned with the initial incision. The proper placement of the flap margin at the tooth-bone junction during closure is important to prevent either recurrence of the pocket or result in the exposure of bone. The internal bevel incision should be scalloped into the interdental area to preserve the interdental papilla (see Figure 59-2). This will allow better coverage of the bone at both the radicular and the interdental areas.

If the surgeon contemplates osseous surgery, the first incision should be placed in such a way to compensate for the removal of the bone tissue so the flap can be placed at the tooth-bone junction.

Reconstructive Techniques

The techniques used to achieve reconstructive and regenerative objectives are the papilla preservation flap8 and the conventional flap using only crevicular or pocket incisions. This will allow the clinician to retain the maximum amount of gingival tissue, including the papilla, which is essential for graft or membrane coverage.

Modified Widman Flap

In 1965, Morris4 revived a technique described early in the twentieth century in the periodontal literature; he called it the “unrepositioned mucoperiosteal flap.” Essentially, the same procedure was presented in 1974 by Ramfjord and Nissle,6 who called it the “modified Widman flap” (Figure 59-3). This technique offers the possibility of establishing an intimate postoperative adaptation of healthy collagenous connective tissue to tooth surfaces2,3,5,6 and provides access for adequate instrumentation of the root surfaces and immediate closure of the area. The following steps outline the modified Widman flap technique.

Figure 59-3 Modified Widman flap technique. A, Facial view before surgery. Probing of pockets revealed interproximal depths ranging from 4 to 8 mm and facial and palatal depths of 2 to 5 mm. B, Radiographic survey of area. Note generalized horizontal bone loss. C, Facial internal bevel incision. D, Palatal incision. E, Elevation of the flap, leaving a wedge of tissue still attached to its base. F, Removal of tissue. G, Tissue removed and ready for scaling and root planing. H, Scaling and root planing of exposed root surfaces. I, Continuous, independent sling suture of facial portion of surgery. J, Continuous, independent sling suture of palatal portion of surgery. K, Post surgical result.

(Courtesy Dr. Kitetsu Shin, Saitama, Japan).

Ramfjord and Nissle6 performed an extensive longitudinal study comparing the Widman procedure, as modified by them, with the curettage technique and the pocket elimination methods that include bone contouring when needed. The patients were assigned randomly to one of the techniques, and results were analyzed yearly up to 7 years after therapy. They reported approximately similar results with the three methods tested. Pocket depth was initially similar for all methods but was maintained at shallower levels with the Widman flap; the attachment level remained higher with the Widman flap.

Undisplaced Flap

Currently, the undisplaced flap may be the most frequently performed type of periodontal surgery. It differs from the modified Widman flap in that the soft tissue pocket wall is removed with the initial incision; thus it may be considered an “internal bevel gingivectomy.” The undisplaced flap and the gingivectomy are the two techniques that surgically remove the pocket wall. To perform this technique without creating a mucogingival problem, the clinician should determine that enough attached gingiva will remain after removal of the pocket wall. The following steps outline the undisplaced flap technique.

Figure 59-4 Diagram showing the location of two different areas where the internal bevel incision is made in an undisplaced flap. The incision is made at the level of the pocket to discard the tissue coronal to the pocket if there is sufficient remaining attached gingiva.

Figure 59-5 Undisplaced flap. A and B, Preoperative facial and palatal views. C and D, Internal bevel incisions in the facial and palatal aspects. Note the deeper scalloping palatally for the replaced flap. E and F, Flap elevated showing osseous defects. G and H, Osseous surgery has been performed. I and J, Flaps have been placed in their original site and sutured. K and L, Postoperative results.

(Courtesy Dr. Paulo Camargo, University of California, Los Angeles.)

Palatal Flap

The surgical approach to the palatal area differs from that for other areas because of the character of the palatal tissue and the anatomy of the area. The palatal tissue is all attached, keratinized tissue and has none of the elastic properties associated with other gingival tissues. Therefore the palatal tissue cannot be apically displaced, and a partial-thickness (split-thickness) flap cannot be accomplished.

The initial incision for the palatal flap should allow the flap, when sutured, to be precisely adapted at the root-bone junction. The flap cannot be moved apically or coronally to adapt to the root-bone junction, as can be done with the flaps in other areas. Therefore the location of the initial incision is important for the final placement of the flap.

The palatal tissue may be thin or thick, it may or may not have osseous defects, and the palatal vault may be high or low. These anatomic variations may require changes in the location, angle, and design of the incision.

The initial incision for a flap varies with the anatomic situation. As shown in Figure 59-6, the initial incision may be the usual internal bevel incision, followed by crevicular and interdental incisions. If the tissue is thick, a horizontal gingivectomy incision may be made, followed by an internal bevel incision that starts at the edge of this incision and ends on the lateral surface of the underlying bone. The placement of the internal bevel incision must be done in such a way that the flap fits around the tooth without exposing the bone.

Figure 59-6 Examples of two methods for eliminating a palatal pocket. One incision is an internal bevel incision made at the area of the apical extent of the pocket. The other procedure uses a gingivectomy incision, which is followed by an internal bevel incision.

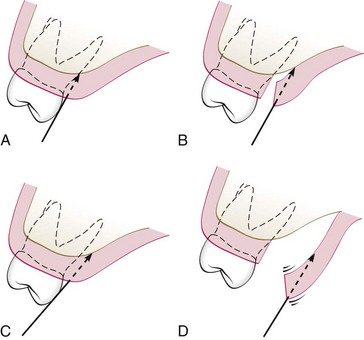

Before the flap is reflected to the final position for scaling and management of the osseous lesions, its thickness must be checked. Flaps should be thin to adapt to the underlying osseous tissue and provide a thin, knifelike gingival margin. Flaps, particularly palatal flaps, often are too thick; they may have a propensity to separate from the tooth and may delay and complicate healing. It is best to thin the flaps before their complete reflection because a free, mobile flap is difficult to hold for thinning (Figure 59-7). A sharp, thin papilla positioned properly around the interdental areas at the tooth-bone junction is essential to prevent recurrence of soft tissue pockets.

Figure 59-7 Diagrams illustrating the angle of the internal bevel incision in the palate and the different ways to thin the flap. A, Usual angle and direction of the incision. B, Thinning of the flap after it has been slightly reflected with a second internal incision. C, Beveling and thinning of the flap with the initial incision if the position and contour of the tooth allow. D, The problem encountered in thinning the flap once it has been reflected. The flap is too loose and free for proper positioning and incision.

The purpose of the palatal flap should be considered before the incision is made. If the intent of the surgery is debridement, the internal bevel incision is planned so that the flap adapts at the root-bone junction when sutured. If osseous resection is necessary, the incision should be planned to compensate for the lowered level of the bone when the flap is closed. Probing and sounding of the osseous level and the depth of the intrabony pocket should be used to determine the position of the incision.

The apical portion of the scalloping should be narrower than the line-angle area because the palatal root tapers apically. A rounded scallop results in a palatal flap that does not fit snugly around the root. This procedure should be done before the complete reflection of the palatal flap because a loose flap is difficult to grasp and stabilize for dissection.

It is sometimes necessary to thin the palatal flap after it has been reflected. This can be accomplished by holding the inner portion of the flap with a mosquito hemostat or Adson forceps as the inner connective tissue is carefully dissected away with a sharp #15 scalpel blade. Care must be taken not to perforate or overthin the flap. The edge of the flap should be thinner than the base; therefore the blade should be angled toward the lateral surface of the palatal bone. The dissected inner connective tissue is removed with a hemostat. As with any flap, the triangular papilla portion should be thin enough to fit snugly against the bone and into the interdental area (Figure 59-8).

Figure 59-8 A, Distal view of incisions made to eliminate a pocket distal to the maxillary second molar. B, Two parallel incisions and the removal of the intervening tissue. C, Thinning of the flap and contouring of the bone. D, Approximation of the buccal and palatal flaps.

The principles for the use of vertical releasing incisions are similar to those for using other incisions. Care must be exercised so that the length of the incision is minimal to avoid the numerous vessels located in the palate.

Apically Displaced Flap

With some variants, the apically displaced flap technique can be used for (1) pocket eradication and/or (2) widening the zone of attached gingiva. Depending on the purpose, it can be a full-thickness (mucoperiosteal) or a split-thickness (mucosal) flap. The split-thickness flap requires more precision and time, as well as a gingival tissue thick enough to split, but it can be more accurately positioned and sutured in an apical position using a periosteal suturing technique, as follows:

Figure 59-9 Apically displaced flap. A and B, Facial and lingual preoperative views. C and D, Facial and lingual flaps elevated. E and F, After debridement of the areas. G and H, Sutures in place. I and J, Healing after 1 week. K, Healing after 2 months. Note the preservation of attached gingiva displaced to a more apical position.

(Courtesy of Dr. Thomas Han, Los Angeles.)

After 1 week, dressings and sutures are removed. The area is usually repacked for another week, after which the patient is instructed to use chlorhexidine mouth rinse or to apply chlorhexidine topically with cotton-tipped applicators for another 2 or 3 weeks.

Flaps for Reconstructive Surgery

In current reconstructive therapy, bone grafts, membranes, or a combination of these, with or without other agents, are used for a successful outcome (see Chapter 61). The flap design should therefore be set up so that the maximum amount of gingival tissue and papilla are retained to cover the material(s) placed in the pocket.

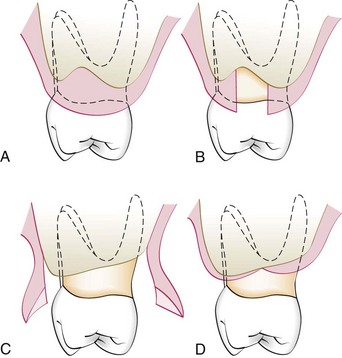

Two flap designs are available for reconstructive surgery: the papilla preservation flap and the conventional flap with only crevicular incisions. The flap design of choice is the papilla preservation flap, which retains the entire papilla covering the lesion. However, to use this flap, there must be adequate interdental space to allow the intact papilla to be reflected with the facial or lingual/palatal flap. When the interdental space is very narrow, making it impossible to perform a papilla preservation flap, a conventional flap with only crevicular incisions is made.

Papilla Preservation Flap

The technique for employing a papilla preservation flap (Figures 59-10 and 59-11) is as follows:

Figure 59-10 Flap design for a papilla preservation flap. A, Incisions for this type of flap are depicted by interrupted lines. The preserved papilla can be incorporated into the facial or the lingual-palatal flap. B, Reflected flap exposes the underlying bone. Several osseous defects are seen. C, Flap returned to its original position, covering the entire interdental spaces.

Figure 59-11 Papilla preservation flap. A, Facial view after sulcular incisions have been made. B, Straight-line incision in the palatal area about 3 mm from gingival margins. This incision is then connected to the margins with vertical incisions in the midpart of each tooth. C, Papillae are reflected with the facial flap. D, Lingual view after reflection of the flap. E, Lingual view after the flap is brought back to its original position. It is then sutured with independent sutures. F, Facial view after healing. G, Palatal view after healing.

(Courtesy of Dr. Thomas Han, Los Angeles.)

Conventional Flap

The technique for employing a conventional flap for reconstructive surgery is as follows:

Distal Molar Surgery

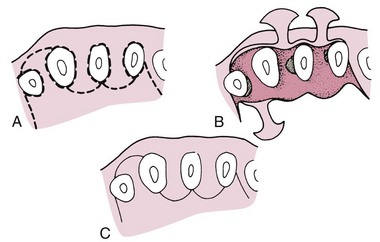

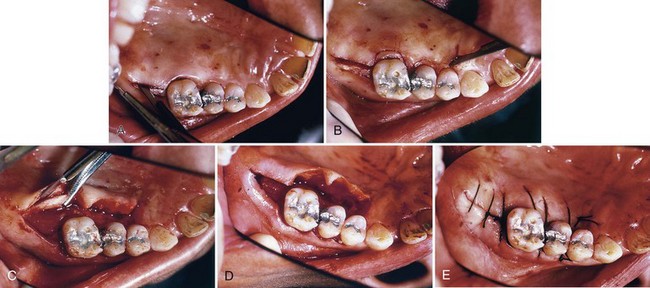

Treatment of periodontal pockets on the distal surface of terminal molars is often complicated by the presence of bulbous fibrous tissue over the maxillary tuberosity or prominent retromolar pads in the mandible. Deep vertical defects are also often present in conjunction with the redundant fibrous tissue. Some of these osseous lesions may result from incomplete repair after the extraction of impacted third molars (Figure 59-12).

Figure 59-12 A, Impaction of a third molar distal to a second molar with little or no interdental bone between the two teeth. B, Removal of the third molar creates a pocket with little or no bone distal to the second molar. This often leads to a vertical osseous defect distal to the second molar (C).

The gingivectomy incision is the most direct approach in treating distal pockets that have adequate attached gingiva and no osseous lesions. However, the flap approach is less traumatic postsurgically because it produces a primary closure wound rather than the open secondary wound left by a gingivectomy incision. In addition, it results in attached gingiva and provides access for examination and if needed, correction of the osseous defect. Procedures for this purpose were described by Robinson7 and Braden2 and modified by several other investigators. Some representative procedures are discussed here.

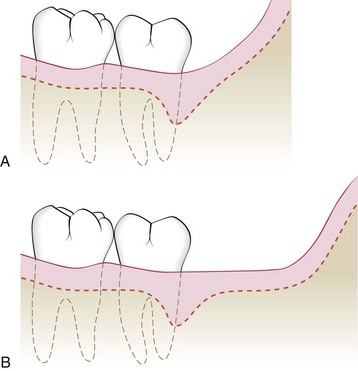

Maxillary Molars

The treatment of distal pockets on the maxillary arch is usually simpler than the treatment of a similar lesion on the mandibular arch because the tuberosity presents a greater amount of fibrous attached gingiva than does the area of the retromolar pad. In addition, the anatomy of the tuberosity extending distally is more adaptable to pocket elimination than is that of the mandibular molar arch, where the tissue extends coronally. However, the lack of a broad area of attached gingiva and the abruptly ascending tuberosity sometimes complicate therapy (Figure 59-13).

Figure 59-13 A, Removal of a pocket distal to the maxillary second molar may be difficult if there is minimal attached gingiva. If the bone ascends acutely apically, the removal of this bone may make the procedure easier. B, Long distal tuberosity with abundant attached gingiva is an ideal anatomic situation for distal pocket eradication.

The following considerations determine the location of the incision for distal molar surgery: accessibility, amount of attached gingiva, pocket depth, and available distance from the distal aspect of the tooth to the end of the tuberosity or retromolar pad.

Technique

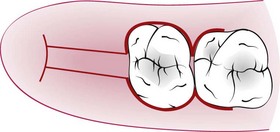

Two parallel incisions, beginning at the distal portion of the tooth and extending to the mucogingival junction distal to the tuberosity or retromolar pad, are made (Figure 59-14). The faciolingual distance between these two incisions depends on the depth of the pocket and the amount of fibrous tissue involved. The deeper the pocket, the greater is the distance between the two parallel incisions. Importantly, when the tissue between the two incisions is removed and the flaps are thinned, the two flap edges must approximate each other at a new apical position without overlapping.

Figure 59-14 A, Distal pocket eradication procedure with the incision distal to the molar. B, Scalloped incision around the remaining teeth. C, Flap reflected and thinned around the distal incision. D, Flap in position before suturing. It should be closely approximated. E, Flap sutured both distally and over the remaining surgical area.

When the depth of the pocket cannot be easily estimated, it is better to err on the conservative side, leaving overlapping flaps rather than flaps that are too short and result in exposure of bone. When the two flaps overlap after the surgery is completed, they should be placed one over the other, and the overlapping portion of one of them is grabbed with a hemostat. A sharp knife or scissors is then used to cut the excess.

A transversal incision is made at the distal end of the two parallel incisions so that a long, rectangular piece of tissue can be removed. These incisions are usually interconnected with the incisions for the remainder of the surgery in the quadrant involved. The parallel distal incisions should be confined to the attached gingiva because bleeding and flap management become problems when the incision is extended into the alveolar mucosa. If access is difficult, especially if the distance from the distal aspect of the tooth to the mucogingival junction is short, a vertical incision can be made at the end of the parallel incisions.

In treating the tuberosity area, the two distal incisions are usually made at the midline of the tuberosity (Figure 59-15). In most cases, no attempt is made to undermine the underlying tissue at this time. These incisions are made straight down into the underlying bone where access is difficult. A #12B blade is generally used. It is easier to dissect out the underlying redundant tissue when the flap is partially reflected. When the distal flaps are placed back on the bone, the two flap margins should closely approximate each other.

Mandibular Molars

Incisions for the mandibular arch differ from those used for the tuberosity because of differences in the anatomy and histologic features of the areas. The retromolar pad area does not usually present as much fibrous attached gingiva. The keratinized gingiva, if present, may not be found directly distal to the molar. The greatest amount may be distolingual or distofacial and may not be over the bony crest. The ascending ramus of the mandible may also create a short, horizontal area distal to the terminal molar (Figure 59-16). The shorter this area, the more difficult it is to treat any deep distal lesion around the terminal molar.

Figure 59-16 A, Pocket eradication distal to a mandibular second molar with minimal attached gingiva and a close ascending ramus is anatomically difficult. B, For surgical procedures distal to a mandibular second molar, abundant attached gingiva and distal space are ideal.

The two incisions distal to the molar should follow the area with the greatest amount of attached gingiva (Figure 59-17). Therefore the incisions could be directed distolingually or distofacially, depending on which area has more attached gingiva. Before the flap is completely reflected, it is thinned with a #15 blade. It is easier to thin the flap before it is completely free and mobile. After the reflection of the flap and the removal of the redundant fibrous tissue, any necessary osseous surgery is performed. The flaps are approximated similarly to those in the maxillary tuberosity area.

Figure 59-17 Incision designs for surgical procedures distal to the mandibular second molar. The incision should follow the areas of greatest attached gingiva and underlying bone.

![]() Science Transfer

Science Transfer

Periodontal flap procedures for pocket therapy include flaps solely for access to root surfaces and bone margins, flaps for the precise processes of osseous surgery, and flaps for periodontal regeneration. Each of these approaches have specific flap designs, step-by-step elements, and all of them have calculus removal and root planing as an essential treatment protocol. Flaps should allow adequate access and should be reflected so that at least 3 mm of bone crestal is exposed. If flaps are to be positioned apically, flap mobility is obtained by extending facial and lingual flap elevation beyond the mucogingival junction, which enables the elasticity of the mucosa to be applied. Palatal flaps are much less mobile; thus inverse bevel incisions are used to remove marginal gingival tissues so that at the time of suturing, the flap margin is positioned apically, if so indicated.

Papilla preservation techniques with various modifications are applied to those areas in which gingival recession needs to be minimized. In some esthetic locations, nonsurgical therapy may be more appropriate than flap surgery.

Postoperative plaque control is essential for successful outcomes, and clinicians should ensure that patients have demonstrated adequate oral hygiene during the presurgical Phase I events and continue this after surgery. Adjacent edentulous areas are incorporated into the flap design using wedge incisions that enable access to adjacent root surfaces for complete root planing and allow clinicians to visualize and treat the associated bone defects.

1 Ainamo A, Bergenholtz A, Hugoson A, et al. Location of the mucogingival junction 18 years after apically repositioned flap surgery. J Clin Periodontol. 1992;19:49.

2 Braden BE. Deep distal pockets adjacent to terminal teeth. Dent Clin North Am. 1969;13:161.

3 Matelski DE, Hurt WC. The corrective phase: the modified Widman flap. In: Hurt WC, editor. Periodontics in general practice. Springfield, Ill: Charles C Thomas, 1976.

4 Morris ML. The unrepositioned mucoperiosteal flap. Periodontics. 1965;3:147.

5 Ramfjord SP. Present status of the modified Widman flap procedure. J Periodontol. 1977;48:558.

6 Ramfjord SP, Nissle RR. The modified Widman flap. J Periodontol. 1974;45:601.

7 Robinson RE. The distal wedge operation. Periodontics. 1966;4:256.

8 Takei HH, Han TJ, Carranza FA, et al. Flap technique for periodontal bone implants: papilla preservation technique. J Periodontol. 1985;56:204.