CHAPTER 52 Phase II Periodontal Therapy

Although in a strict sense, all instrumental therapy can be considered surgical, this chapter refers only to those techniques that include the intentional severing or incising of gingival tissue* with the following purposes:

Objectives of the Surgical Phase

The surgical phase of periodontal therapy has the following main objectives:

The surgical phase consists of techniques performed for pocket therapy and for the correction of related morphologic problems, namely, mucogingival defects. In many cases, procedures are combined so that one surgical intervention fulfills both objectives.

The purpose of surgical pocket therapy is to eliminate the pathologic changes in the pocket walls; to create a stable, easily maintainable state; and if possible, to promote periodontal regeneration. To fulfill these objectives, surgical techniques (1) increase accessibility to the root surface, making it possible to remove all irritants; (2) reduce or eliminate pocket depth, making it possible for the patient to maintain the root surfaces free of plaque; and (3) reshape soft and hard tissues to attain a harmonious topography. Pocket reduction surgery seeks to reduce pocket depth by either resective or regenerative means or often by a combination of both methods (Box 52-1). Chapters 59 to 61 describe the different techniques used for these purposes.

BOX 52-1 Periodontal Surgery

Pocket Reduction Surgery

Resective (gingivectomy, apically displaced flap, and undisplaced flap with or without osseous resection)

Correction of Anatomic/Morphologic Defects

Plastic surgery techniques to widen attached gingiva (free gingival grafts, other techniques, etc)

Esthetic surgery (root coverage, recreation of gingival papillae)

Preprosthetic techniques (crown lengthening, ridge augmentation, and vestibular deepening)

Placement of dental implants, including techniques for site development for implants (guided bone regeneration, sinus grafts)

The second objective of the surgical phase of periodontal therapy is the correction of anatomic morphologic defects that may favor plaque accumulation and pocket recurrence or impair esthetics. It is important to understand that these procedures are not directed to treat disease but aim to alter the gingival and mucosal tissues to correct defects that may predispose to disease. They are performed on noninflamed tissues and in the absence of periodontal pockets. Three types of techniques fall into this category, as follows (see Box 52-1):

The plastic and esthetic surgery techniques are presented in Chapter 63 and the preprosthetic techniques in Chapter 65.

In addition, periodontal surgical techniques for the placement of dental implants are available. These involve not only the implant placement techniques but also a variety of surgical procedures to adapt the neighboring tissues, such as the sinus floor or the mandibular nerve canal, for subsequent placement of the implant (see Box 52-1). These methods are discussed in Chapters 71 and 72.

Surgical Pocket Therapy

Surgical pocket therapy can be directed toward (1) access surgery to ensure the removal of irritants from the tooth surface or (2) elimination or reduction of the depth of the periodontal pocket.

The effectiveness of periodontal therapy is predicated on success in completely eliminating calculus, plaque, and diseased cementum from the tooth surface. Numerous investigations have shown that the difficulty of this task increases as the pocket becomes deeper.2,5 The presence of irregularities on the root surface also increase the difficulty of the procedure. As the pocket becomes deeper, the surface to be scaled increases, more irregularities appear on the root surface, and accessibility is impaired.11,15 The presence of furcations will also create insurmountable problems for scaling the root surface4 (see Chapter 62).

These problems can be reduced by resecting or displacing the soft tissue wall of the pocket, thereby increasing the visibility and accessibility of the root surface.3 The flap approach and the gingivectomy technique attain this result.

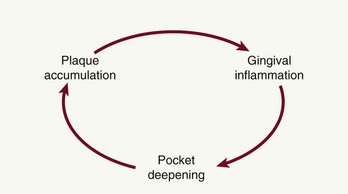

The need to eliminate or reduce the depth of the pocket is another important consideration. Pocket elimination consists of reducing the depth of periodontal pockets to that of a physiologic sulcus to enable cleansing by the patient. By proper case selection, both resective techniques and regenerative techniques can be used to accomplish this goal. The presence of a pocket produces areas that are impossible for the patient to keep clean, which establishes the vicious cycle depicted in Figure 52-1.

Results of Pocket Therapy

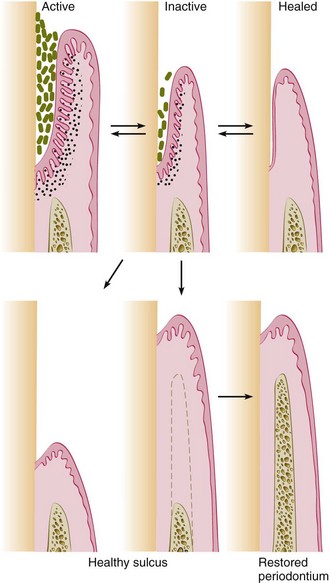

A periodontal pocket can be in an active state or a period of inactivity or quiescence. In an active pocket, underlying bone is being lost (Figure 52-2, top left). It often can be diagnosed clinically by bleeding, either spontaneously or on probing. After Phase I therapy the inflammatory changes in the pocket wall subside, rendering the pocket inactive and reducing its depth (Figure 52-2, top center). The extent of this reduction depends on the depth before treatment and the degree to which the depth is the result of the edematous and inflammatory component of the pocket wall.

Figure 52-2 Possible results of pocket therapy. An active pocket can become inactive and heal by means of a long junctional epithelium. Surgical pocket therapy can result in a healthy sulcus, with or without gain of attachment. Improved gingival attachment promotes restoration of bone height, with re-formation of periodontal ligament fibers and layers of cementum.

Whether the pocket remains inactive depends on the depth, the individual characteristics of the plaque components and the host response. Recurrence of the initial activity is likely.

Inactive pockets can sometimes heal with a long junctional epithelium (Figure 52-2, top right). However, this condition also may be unstable, and the chance of recurrence and re-formation of the original pocket is always present because the epithelial union to the tooth is weak. However, one study in monkeys has shown that the long junctional epithelial union may be as resistant to plaque infection as a normal connective tissue attachment.9

Studies have shown that inactive pockets can be maintained for long periods with little loss of attachment by means of frequent scaling and root-planing procedures.6,10,12 A more reliable and stable result is obtained, however, by transforming the pocket into a healthy sulcus. The bottom of the healthy sulcus can be located either where the bottom of the pocket was localized or coronal to it. In the first case, there is no gain of attachment (Figure 52-2, bottom left), and the area of the root that was previously the tooth wall of the pocket becomes exposed. This does not mean that the periodontal treatment has caused recession but rather that it has uncovered the recession previously induced by the disease.

The healthy sulcus can also be located coronal to the bottom of the preexisting pocket (Figure 52-2, bottom center and right). This is conducive to a restored marginal periodontium; the result is a sulcus of normal depth with gain of attachment. The creation of a healthy sulcus and a restored periodontium entails a total restoration of the status that existed before periodontal disease began, which is the ideal result of treatment.

Pocket Elimination Versus Pocket Maintenance

Pocket elimination (depth reduction to gingival sulcus levels) has traditionally been considered one of the main goals of periodontal therapy. It was considered vital because of the need to improve accessibility to root surfaces for the therapist during treatment and for the patient after healing. The prevalent opinion is the presence of deep pockets after therapy represents a greater risk of disease progression than shallow sites. Individual probing depths are not good predictors of future clinical attachment loss. The absence of deep pockets in treated patients, on the other hand, is an excellent predictor of a stable periodontium.5

Longitudinal studies of different therapeutic modalities over the last 30 years have given conflicting results,7,16 probably because of inherent problems created by the “split-mouth” design. In general, after surgical therapy, pockets that rebound to a shallow or moderate depth can be maintained in a healthy state and without radiographic evidence of advancing bone loss by maintenance visits consisting of scaling and root planing, with oral hygiene reinforcement performed at regular intervals of 3 months or less. In these patients, the residual pocket can be examined with a thin periodontal probe, but no pain, exudate, or bleeding results. This appears to indicate that no plaque has formed on the subgingival root surfaces.

These findings do not alter the indications for periodontal surgery because the results are based on surgical exposure of the root surfaces for thorough elimination of irritants. However, these findings emphasize the importance of the maintenance phase and the close monitoring of both level of attachment and pocket depth, together with the other clinical variables (bleeding, exudation, or tooth mobility). The transformation of the initial deep, active pocket into a shallower, inactive, maintainable pocket requires some form of definitive pocket therapy and constant supervision thereafter.

Pocket depth is an extremely useful and widely employed clinical determination, but it must be evaluated together with level of attachment and the presence of bleeding, exudation, and pain. The most important variable for evaluating whether a pocket (or deep sulcus) is progressive is the level of attachment, which is measured in millimeters from the cementoenamel junction. The apical displacement of the level of attachment places the tooth in jeopardy, not the increase in pocket depth, which may be caused by coronal displacement of the gingival margin.

Pocket depth remains an important clinical variable that contributes to decisions about treatment selection. Lindhe et al8 compared the effect of root planing alone and with a modified Widman flap on the resultant level of attachment and in relation to initial pocket depth. They reported that scaling and root-planing procedures induce loss of attachment if performed in pockets shallower than 2.9 mm, whereas gain of attachment occurs in deeper pockets. The modified Widman flap induces loss of attachment if done in pockets shallower than 4.2 mm but results in a greater gain of attachment than root planing in pockets deeper than 4.2 mm. The loss is a true loss of connective tissue attachment, whereas the gain can be considered a false gain because of reduced penetrability of connective tissues apical to the bottom of the pocket after treatment.9,17

Furthermore, probing depths established after active therapy and healing (approximately 6 months after treatment) can be maintained unchanged or reduced even further during a maintenance period involving careful prophylaxis once every 3 months.8

Ramfjord12 and Rosling13 and their colleagues showed that, regardless of the surgical technique used for pocket therapy, a certain pocket depth recurs. Therefore maintenance of this depth without any further loss of attachment becomes the goal.

Reevaluation After Phase I Therapy

Longitudinal studies have noted that all patients should be treated initially with scaling and root planing and that a final decision on the need for periodontal surgery should be made only after a thorough evaluation of the effects of Phase I therapy.5 The assessment is generally made no less than 1 to 3 months and sometimes as much as 9 months after the completion of Phase I therapy.1 This reevaluation of the periodontal condition should include reprobing the entire mouth. The presence of calculus, root caries, defective restorations, and signs of persistent inflammation should also be evaluated.

Critical Zones in Pocket Surgery

Criteria for the selection of one of the different surgical techniques for pocket therapy are based on clinical findings in the soft tissue pocket wall, tooth surface, underlying bone, and attached gingiva.

Zone 1: Soft Tissue Pocket Wall

The clinician should determine the morphologic features, thickness, and topography of the soft tissue pocket wall and persistence of inflammatory changes in the wall.

Zone 2: Tooth Surface

The clinician should identify the presence of deposits and alterations on the cementum surface and determine the accessibility of the root surface to instrumentation. Phase I therapy should have solved many, if not all, of the problems on the tooth surface. Evaluation of the results of Phase I therapy should determine the need for further therapy and the method to be used.

Zone 3: Underlying Bone

The clinician should establish the shape and height of the alveolar bone next to the pocket wall through careful probing and clinical and radiographic examinations. Bony craters, horizontal or angular bone losses, and other bone deformities are important criteria in selection of the treatment technique.

Zone 4: Attached Gingiva

The clinician should consider the presence or absence of an adequate band of attached gingiva when selecting the pocket treatment method. Diagnostic techniques for mucogingival problems are described in Chapter 63. An inadequate attached gingiva may be caused by a high frenum attachment, marked gingival recession, or a deep pocket that reaches the level of the mucogingival junction. All these possible conditions should be explored and their influence on pocket therapy determined.

Indications for Periodontal Surgery

The following findings may indicate the need for a surgical phase of therapy:

Methods of Pocket Therapy

The methods for pocket therapy can be classified under the following three main headings:

The techniques, what they accomplish, and the factors governing their selection are presented in Chapters 59 to 62.

Criteria for Method Selection

Scientific criteria to establish the indications for each technique are difficult to determine. Longitudinal studies following a significant number of cases over a number of years, standardizing multiple factors and many variables, would be needed. Clinical experience, however, has suggested the criteria for selecting the method to treat the pocket. The selection of a technique for treatment of a particular periodontal lesion is based on the following considerations:

Each of these variables are analyzed in relation to the pocket therapy techniques available, and a specific technique is selected. Of the many techniques, the one that would most successfully solve the problems with the fewest undesirable effects should be chosen. Clinicians who adhere to one technique to solve all problems do not use to the advantage of the patient the wide repertoire of techniques at their disposal.

Approaches to Specific Pocket Problems

Therapy for Gingival Pockets

Two factors are taken into consideration: (1) the character of the pocket wall and (2) the accessibility of the pocket. The pocket wall can be either edematous or fibrotic. Edematous tissue shrinks after the elimination of local factors, thereby reducing or totally eliminating pocket depth. Therefore scaling and root planing are the technique of choice in these cases.

Pockets with a fibrotic wall are not appreciably reduced in depth after scaling and root planing; therefore they are eliminated surgically. Until recently, gingivectomy was the only technique available; it solves the problem successfully, but in cases of marked gingival enlargement (e.g., severe phenytoin enlargement), it may leave a large wound that goes through a painful and prolonged healing process. In these patients, a modified flap technique can adequately solve the problem with fewer postoperative problems (see Chapter 58).

Therapy for Slight Periodontitis

In slight or incipient periodontitis, a small amount of bone loss has occurred, and pockets are shallow to moderate. In these patients, the conservative approach with good oral hygiene will generally suffice to control the disease. Incipient periodontitis that recurs in previously treated sites may require a thorough analysis of the causes for the recurrence. Occasionally, a surgical approach may be required to correct the problem.

Therapy for Moderate-to-Severe Periodontitis in Anterior Sector

The anterior teeth are important esthetically; therefore the technique that causes the least amount of visual root exposure should be considered. However, the importance of esthetics may be different for different patients, and nonelimination of the pocket may place the tooth in jeopardy. The final decision may have to be a compromise between health and esthetics, not attaining ideal results in either respect.

Anterior teeth offer two main advantages to a conservative approach: (1) they are all single rooted and easily accessible and (2) patient compliance and thoroughness in plaque control are easier to attain. Therefore scaling and root planing are the technique of choice for the anterior teeth.

Sometimes, however, a surgical technique may be necessary because of the need for improved accessibility for root planing or regenerative surgery of osseous defects. The papilla preservation flap can be used for both purposes and also offers a better postoperative result, with less recession and reduced soft tissue crater formation interproximally.14 The papilla preservation flap is the first choice when a surgical approach is needed.

When the teeth are too close interproximally, the papilla preservation technique may not be feasible, and a technique that splits the papilla must be used. The sulcular incision flap offers good esthetic results and is the next choice.

When esthetics are not the primary consideration, the modified Widman flap can be chosen. This technique uses an internal bevel incision about 1 to 2 mm from the gingival margin without thinning the flap and may result in some minor recession.

Infrequently, bone contouring may be needed despite the resultant root exposure. The technique of choice is the apically displaced flap with bone contouring.

Therapy for Moderate-to-Severe Periodontitis in Posterior Area

Treatment for premolars and molars usually poses no esthetic problem but frequently involves difficult accessibility. Bone defects occur more often in the posterior than the anterior sector, and root morphologic features, particularly in relation to furcations, may offer insurmountable problems for instrumentation in a close field. Therefore surgery is frequently indicated in the posterior region.

The purpose of surgery in the posterior area is either enhanced accessibility or the need for definitive pocket reduction requiring osseous surgery. Accessibility can be obtained by either the undisplaced or the apically displaced flap.

Most patients with moderate to severe periodontitis have developed osseous defects that require some degree of osseous remodeling or reconstructive procedures. When osseous defects amenable to reconstruction are present, the papilla preservation flap is the technique of choice because it better protects the interproximal areas where defects are frequently present. Second and third choices are the sulcular flap and the modified Widman flap, maintaining as much of the papilla as possible.

When osseous defects with no possibility of reconstruction are present, such as interdental craters, the technique of choice is the flap with osseous contouring.

Surgical Techniques for Correction of Morphologic Defects

The objectives and rationale for the techniques performed to correct morphologic defects (mucogingival, esthetic, and preprosthetic) are given in Chapter 63.

Surgical Techniques for Implant Placement and Related Problems

The objectives and rationale for these techniques are described in Chapter 71.

![]() Science Transfer

Science Transfer

Phase II therapy is used to surgically treat residual periodontal pockets and bone defects remaining after Phase I therapy. All patients treated surgically need to have a preoperative history of adequate plaque control with 20% or more of the tooth surfaces free of plaque after oral hygiene procedures.

Most types of surgical therapy will result in some postsurgical gingival recession and so they are not useful in the anterior segments of the mouth in those patients in whom the esthetic shape of the gingiva is visible. These patients may be best treated with nonsurgical procedures, but new, innovative regeneration surgical techniques using modified papilla preservation approaches, together with minimally invasive procedures, often coupled with a basis of microsurgery, are showing promising results in maintaining and even improving papillary and labial tissue levels.

1 Badersten A, Nilveus R, Egelberg J. Effect of nonsurgical periodontal therapy. II. Severely advanced periodontitis. J Clin Periodontol. 1984;11:63.

2 Bower RC. Furcation morphology relative to periodontal treatment: furcation root surface anatomy. J Periodontol. 1979;50:366.

3 Caffesse RG, Sweeney PL, Smith BA. Scaling and root planing with and without periodontal flap surgery. J Clin Periodontol. 1986;11:205.

4 Gher ME, Vernino AR. Root morphology: clinical significance in pathogenesis and treatment of periodontal disease. J Am Dent Assoc. 1980;101:627.

5 Greensteifl G. Contemporary interpretation of probing depth assessment: diagnostic and therapeutic implications: a literature review. J Periodontol. 1997;68:1194.

6 Hill RW, Ramfjord SP, Morrison GC, et al. Four types of periodontal treatment compared over two years. J Periodontol. 1981;52:655.

7 Kaldahl WB, Kalkwarf KL, Patil KD. A review of longitudinal studies that compared periodontal therapies. J Periodontol. 1993;64:243.

8 Lindhe J, Socransky SS, Nyman S, et al. Critical probing depths in periodontal therapy. J Clin Periodontol. 1982;9:323.

9 Magnusson I, Runstad L, Nyman S, et al. A long junctional epithelium: a locus minoris resistentiae in plaque infection. J Clin Periodontol. 1983;10:333.

10 Pihlstrom BL, Ortiz Campos C, McHugh RB. A randomized four-year study of periodontal therapy. J Periodontol. 1981;52:227.

11 Rabbani GM, Ash MM, Caffesse RG. The effectiveness of subgingival scaling and root planing in calculus removal. J Periodontol. 1981;52:119.

12 Ramfjord SP, Knowles JW, Nissle RR, et al. Results following three modalities of periodontal therapy. J Periodontol. 1975;12:522.

13 Rosling B, Nyman S, Lindhe J, et al. The healing potential of the periodontal tissues following different techniques of periodontal surgery in plaque-free dentitions: a 2-year clinical study. J Clin Periodontol. 1976;3:233.

14 Takei HH, Han TJ, Carranza FAJr, et al. Flap technique for periodontal bone implants: the papilla preservation technique. J Periodontol. 1985;56:204.

15 Waerhaug J. Healing of the dentoepithelial junction following subgingival plaque control. II. As observed on extracted teeth. J Periodontol. 1978;40:119.

16 Weeks PR. Pros and cons of periodontal pocket elimination procedures. J West Soc Periodontol. 1980;28:4.

17 Westfelt E, Bragd L, Socransky SS, et al. Improved periodontal conditions following therapy. J Clin Periodontol. 1985;12:283.