Chapter 1 Ethics, law and communication

Ethics and the law

Ethics: an introduction

The practice of medicine is inherently moral:

Biomedical expertise and clinical science has to be applied by and to people.

Biomedical expertise and clinical science has to be applied by and to people.

Medical decisions are underpinned by values and principles.

Medical decisions are underpinned by values and principles.

Potential courses of action will have implications that are often uncertain.

Potential courses of action will have implications that are often uncertain.

Technological advancements sometimes have unintended or unforeseen consequences.

Technological advancements sometimes have unintended or unforeseen consequences.

The profession has to agree on its collective purpose, aims and standards. People are much more than a collection of symptoms and signs – they have preferences, priorities, fears and hopes. Doctors too are much more than interpreters of symptoms and signs – they also have preferences, priorities, fears and hopes. Ethics is part of practice; it is a practical pursuit.

The study of the moral dimension of medicine is known as medical ethics in the UK, and bioethics internationally. To become and to practise as a doctor requires an awareness of, and reflection on, one’s ethical attitudes. All of us have personal values and moral intuitions. In the field of ethics, a necessary part of learning is to become aware of the assumptions on which these personal values are based, to reflect on them critically, and to listen and respond to challenging or opposing beliefs.

Ethics is commonly characterized as the consideration of big moral questions that preoccupy the media: questions about cloning, stem cells and euthanasia are what many immediately think of when the words ‘medical ethics’ are used. However, ethics pervades all of medicine. The daily and routine workload is also rife with ethical questions and dilemmas: introductions to patients, dignity on the wards, the use of resources in clinic, the choice of antibiotic and the medical report for a third party, are as central to ethics as the issues that absorb the popular representation of the subject.

The study and practice of ethics incorporate knowledge, cognitive skills such as reasoning, critique and logical analysis, and clinical skills. Abstract ethical understanding has to be integrated with other clinical knowledge and applied thoughtfully and appropriately in practice.

Ethical practice: sources, resources and approaches

To engage with an ethical issue in clinical practice depends on:

discerning the relevant moral question(s)

discerning the relevant moral question(s)

looking at the relevant ethical theories and/or tools

looking at the relevant ethical theories and/or tools

identifying applicable guidance (e.g. from a professional body)

identifying applicable guidance (e.g. from a professional body)

integrating the ethical analysis with an accurate account of the law (both national and international).

integrating the ethical analysis with an accurate account of the law (both national and international).

Personal views must be taken into account, but other perspectives should be acknowledged and supported by reasoning, and located in an accurate understanding of the current law and relevant professional guidance.

Ethical theories and frameworks

Key ethical theories are summarized in Box 1.1.

![]() Box 1.1

Box 1.1

Key ethical theories

Deontology: a universally applicable rule or duty-based approach to morality, e.g. a deontologist would argue that one should always tell truth irrespective of the consequences.

Consequentialism: an approach that argues that morality is located in consequences. Such an approach will focus on likely risks and benefits.

Virtue ethics: offers an approach in which particular traits or behaviours are identified as desirable.

Rights theory: assesses morality with reference to the justified claims of others. Rights are either ‘natural’ and arise from being human, or legal, and therefore enforceable in court. Positive rights impose a duty on another to act whilst negative rights prohibit interference by others.

Narrative ethics: an approach that argues morality is embedded in the stories shared between patient and clinician and allows for multiple perspectives.

Many doctors find that ethical frameworks and tools which focus on the application of ethical theory to clinical problems are useful. Perhaps the best known is the ‘Four Principles’ approach, in which the principles are:

1. Autonomy: to allow ‘self-rule’, i.e. let patients make their own choices and to decide what happens to them

2. Beneficence: to do good, i.e. act in a patient’s best interests

For some, a consistent process that incorporates the best of each theoretical approach is helpful. So, whatever the ethical question, one should:

summarize the problem and state the moral dilemma(s)

summarize the problem and state the moral dilemma(s)

identify the assumptions being made or to be made

identify the assumptions being made or to be made

analyse with reference to ethical principles, consequences, professional guidance and the law

analyse with reference to ethical principles, consequences, professional guidance and the law

acknowledge other approaches and state the preferred approach with explanation.

acknowledge other approaches and state the preferred approach with explanation.

People respond differently to ethical theories and approaches. Do not be afraid to experiment with ways of thinking about ethics. It is worthwhile understanding other ethical approaches, even in broad terms, as it helps in understanding how others might approach the same ethical problem, especially given the increasingly global context in which healthcare is delivered.

Professional guidance and codes of practice

As well as ethical theories and frameworks, there are codes of practice and professional guidelines. For example, in the UK, the standards set out by the General Medical Council (GMC) are the basis on which doctors are regulated within the UK: if a doctor falls below the expectations of the GMC, disciplinary procedures may follow, irrespective of the harm caused or whether legal action ensues. In other countries, similar professional bodies exist to license doctors and regulate healthcare. All clinicians should be aware of the regulatory framework and professional standards in the country within which they are practising.

Increasingly, ethical practice and professionalism are considered significant from the earliest days of medical study and training. In the UK, attention has turned to the standards expected of medical students. For example, in the UK, all medical schools are required to have ‘Fitness to Practise’ procedures. Students should be aware of their professional obligations from the earliest days of their admission to a medical degree. All medical schools are effectively vouching for a student’s suitability for provisional registration at graduation. Medical students commonly work with patients from the earliest days of their training and are privileged in the access they have to vulnerable people, confidential information and sensitive situations. As such, medical schools have particular responsibilities to ensure that students behave professionally and are fit to study, and eventually to practise, medicine.

The Hippocratic Oath, although well-known, is outdated and something of an ethical curiosity, with the result that it is rarely, if ever, sworn. The symbolic value of taking an oath remains, however, and many medical schools expect students to make a formal commitment to maintain ethical standards.

The law

As it pertains to medicine, the law establishes boundaries for what is deemed to be acceptable professional practice. The law that applies to medicine is both national and international, e.g. the European Convention on Human Rights (Box 1.2). Within the UK, along with other jurisdictions, both statutes and common law apply to the practice of medicine (Box 1.3).

![]() Box 1.2

Box 1.2

European Convention on Human Rights

Substantive rights which apply to evaluating good medical practice

Prohibition of torture, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment (Article 3)

Prohibition of torture, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment (Article 3)

Prohibition of slavery and forced labour (Article 4)

Prohibition of slavery and forced labour (Article 4)

Right to liberty and security (Article 5)

Right to liberty and security (Article 5)

Right to a fair trial (Article 6)

Right to a fair trial (Article 6)

No punishment without law (Article 7)

No punishment without law (Article 7)

Right to respect for private and family life (Article 8)

Right to respect for private and family life (Article 8)

Freedom of thought, conscience and religion (Article 9)

Freedom of thought, conscience and religion (Article 9)

![]() Box 1.3

Box 1.3

Statutes and common law

Statutes

Primary legislation made by the state, e.g. Acts of Parliament in the UK, such as the Mental Capacity Act 2005

Primary legislation made by the state, e.g. Acts of Parliament in the UK, such as the Mental Capacity Act 2005

Secondary (or delegated) legislation: supplementary law made by an authority given the power to do so by the primary legislation

Secondary (or delegated) legislation: supplementary law made by an authority given the power to do so by the primary legislation

Implementation (or statutory) guidance, e.g. the Mental Health Act Code of Practice

Implementation (or statutory) guidance, e.g. the Mental Health Act Code of Practice

The majority of cases involving healthcare arise in the civil system. Occasionally, a medical case is subject to criminal law, e.g. when a patient dies in circumstances that could constitute manslaughter.

Respect for autonomy: capacity and consent

Capacity

Capacity is at the heart of ethical decision-making because it is the gateway to self-determination (Box 1.4). People are able to make choices only if they have capacity. The assessment of capacity is a significant undertaking: a patient’s freedom to choose depends on it. If a person lacks capacity, it is meaningless to seek consent. In the UK, the Mental Capacity Act 2005 sets out the criteria for assessing whether a person has the capacity to make a decision (see Ch. 23, p. 1191).

![]() Box 1.4

Box 1.4

Principles of self-determinationa

Every adult has the right to make his/her own decisions and to be assumed to have capacity unless proved otherwise.

Every adult has the right to make his/her own decisions and to be assumed to have capacity unless proved otherwise.

Everyone should be encouraged and enabled to make his/her own decisions, or to participate as fully as possible in decision-making.

Everyone should be encouraged and enabled to make his/her own decisions, or to participate as fully as possible in decision-making.

Individuals have the right to make eccentric or unwise decisions.

Individuals have the right to make eccentric or unwise decisions.

Proxy decisions should consider best interests, prioritizing what the patient would have wanted, and should be the ‘least restrictive of basic rights and freedoms’.

Proxy decisions should consider best interests, prioritizing what the patient would have wanted, and should be the ‘least restrictive of basic rights and freedoms’.

a Principles underlying the Mental Capacity Act 2005 (England and Wales), which applies to patients over the age of 16 years.

Assessment of capacity is not a one-off judgement. Capacity can fluctuate and assessments of capacity should be regularly reviewed. Capacity should be understood as task-oriented. People may have capacity to make some choices but not others and capacity is not automatically precluded by specific diagnoses or impairments. The way in which a doctor communicates can enhance or diminish a patient’s capacity, as can pain, fatigue and the environment.

Consent

Consent is integral to ethical and lawful practice. To act without, or in opposition to, a patient’s expressed, valid consent is, in many jurisdictions, to commit an assault or battery. Obtaining informed consent fosters choice and gives meaning to autonomy. Valid consent is:

given by a patient who has capacity to make a choice about his or her care

given by a patient who has capacity to make a choice about his or her care

voluntary, i.e. free from undue pressure, coercion or persuasion

voluntary, i.e. free from undue pressure, coercion or persuasion

continuing, i.e. patients should know that they can change their mind at any time.

continuing, i.e. patients should know that they can change their mind at any time.

The basis of informed consent

Those seeking consent for a particular procedure must be competent in the knowledge of how the procedure is performed and its problems. Whilst it is common and good practice for written information to be provided to patients, the existence of written material and a consent form does not remove the responsibility to talk to the patient. The information given to a patient should be that which a ‘reasonable person’ would require whilst being alert to the particular priorities and concerns of individuals. Information shared should:

explain possible consequences of treatment and non-treatment

explain possible consequences of treatment and non-treatment

disclose uncertainty; this should be as much part of the discussion as sharing what is well-understood.

disclose uncertainty; this should be as much part of the discussion as sharing what is well-understood.

Patients should be encouraged to ask questions and express their concerns and preferences. Since it is the health and lives of patients that are potentially at risk, the moral focus of such disclosure should be on what is acceptable to patients rather than to the professionals.

Consent in educational settings

Much medical education and training takes place in the clinical environment. Future doctors have to learn new skills and apply their knowledge to real patients. However, patients must be given a choice as to whether they wish to participate in educational activities. The principles of seeking consent for education are identical to those applied to clinical situations.

Advance decisions

Advance decisions (sometimes colloquially described as ‘living wills’) enable people to express their wishes about future treatment or interventions. The decisions are made in anticipation of a time when a person ceases to have capacity. Different countries have differing approaches to advance decision-making and it is necessary to be aware of the relevant law in the area in which one is practising. Within the UK, advance decisions are governed by legislation, for example the Mental Capacity Act 2005 applies in England and Wales. The criteria for a legally valid advanced decision are that it is:

based on appropriate information

based on appropriate information

specific and applicable to the situation in which it is being considered.

specific and applicable to the situation in which it is being considered.

In practice, it is often the requirement of specificity that is most difficult for patients to fulfil because of the inevitable uncertainty surrounding future illness and potential treatments or interventions. There is one difficulty that for many goes to the heart of an ethical objection to advance decision-making, namely that it is difficult to anticipate the future and how one is likely to feel about that future.

Scope

An advance decision can be made to refuse treatment and to express preferences, but cannot be used to demand treatment. In general, no patient has the right to demand or request treatment that is not clinically indicated. Therefore it would be inconsistent to allow patients to include in their advance decisions requests for specific treatments, procedures or interventions. An advance decision cannot be used to refuse basic care such as maintaining hygiene.

Format

Advance decisions are made orally or in writing. However, advance decisions on the withdrawal or withholding of life-sustaining treatment must be in written form and witnessed and the decision should state explicitly that it is intended to apply even to life-saving situations. The more informal and nonspecific the advance decision is, the more likely it is to be challenged or disregarded as being invalid. If working in a country where advance decisions are recognized, clinicians should make reasonable attempts to establish whether there is a valid advance decision in place and the presumption is to save life where there is ambiguity about either the existence or content of an advance decision. Advance decisions should be periodically reviewed and amendments, revocations or additions are possible provided that the person concerned still has capacity.

Ethical and practical rationale

The ethical rationale for the acceptance of advance decisions is usually said to be respect for patient autonomy and represents the extension of the right to make choices about healthcare in the future. True respect for autonomy and the freedom to choose necessarily involves allowing people to make choices that others might consider misguided. Some suggest that giving patients the opportunity to express their concerns, preferences and reservations about the future management of their health fosters trust and effective relationships with clinicians. However, it could also be argued that none of us will ever have the capacity to make decisions about our future care because the person we become when ill is qualitatively different from the person we are when we are healthy.

Lasting power of attorney

Many countries allow for the appointment of a proxy, or for a third party, to make substituted judgements for people lacking capacity. In England and Wales, consent or refusal can be expressed by someone who has been granted a lasting power of attorney (LPA). Once a person’s lack of capacity has been registered with the Public Guardian and the lasting power of attorney granted, the person holding the power of attorney is charged with representing a patient’s best interests. Therefore, it is imperative to establish whether there is a valid LPA in respect of an incapacitous patient and to adhere to the wishes of the person acting as attorney. The only circumstances in which clinicians need not follow the LPA is where the attorney appears not to be acting in the patient’s best interests. In such situations, the case should be referred to the Court of Protection. Like advance decisions, the ethical rationale for the existence of LPAs is that prospective autonomy is desirable and facilitates informed care, rather than second-guessing patient preferences.

Best interests of patients who lack capacity

Where an adult lacks capacity to give consent, and there is no valid advance decision or power of attorney in place, clinicians are obliged to act in the patient’s best interests. This encompasses more than an individual’s best medical interests. In practice, the determination of best interests is likely to involve a number of people, for example members of the healthcare team, professionals with whom the patient had a longer-term relationship, and relatives and carers.

In England and Wales, an Independent Mental Capacity Advocacy Service provides advocates for patients who lack capacity and have no family or friends to represent their interests. ‘Third parties’ in such a situation, including Independent Mental Capacity Advocates, are not making decisions; rather, they are being asked to give an informed sense of the patient and his or her likely preferences. In some jurisdictions, e.g. in North America, clinical ethicists play an advocacy role and seek to represent the patient’s best interests.

Provision or cessation of life-sustaining treatment

A common situation requiring determination of a patient’s best interests is the provision of life-sustaining treatment, often at the end of life, for a patient who lacks capacity and has neither advance decision nor an attorney. It is considered acceptable not to use medical means to prolong the lives of patients where:

Based on good evidence, the team believes that further treatment will not save life

Based on good evidence, the team believes that further treatment will not save life

The patient is already imminently and irreversibly close to death

The patient is already imminently and irreversibly close to death

The patient is so permanently or irreversibly brain damaged that he or she will always be incapable of any future self-directed activity or intentional social interaction.

The patient is so permanently or irreversibly brain damaged that he or she will always be incapable of any future self-directed activity or intentional social interaction.

Moral and religious beliefs vary widely and, in general, decisions not to provide or continue life-sustaining treatment should always be made with as much consensus as possible amongst both the clinical team and those close to the patient. Where there is unresolvable conflict between those involved in decision-making, a court should be consulted. In emergencies in the UK, judges are always available in the relevant court.

Where clinicians decide not to prolong the lives of imminently dying and/or extremely brain-damaged patients, the legal rationale is that they are acting in the patient’s best interests and seeking to minimize suffering rather than intending to kill, which would constitute murder. In ethical terms, the significance of intention, along with the moral status of acts and omissions, is integral to debates about assisted dying and euthanasia.

Assisted dying

Currently in many countries, there is no provision for lawful assisted dying. For example, physician-assisted suicide, active euthanasia and suicide pacts are all illegal in the UK. In contrast, some jurisdictions, including the Netherlands, Switzerland, Belgium and certain states in the USA, permit assisted dying. However, even where assisted dying is not lawful, withholding and withdrawing treatment is usually acceptable in strictly defined circumstances, where the intention of the clinician is to minimize suffering, not to cause death. Similarly, the doctrine of double effect may apply. It enables clinicians to prescribe medication that has as its principal aim, the reduction of suffering by providing analgesic relief but which is acknowledged to have side-effects such as the depression of respiratory effort (e.g. opiates). Such prescribing is justifiable on the basis that the intention is benign and the side-effects, whilst foreseen, are not intended to be the primary aim of treatment. End-of-life care pathways, which provide for such approaches where necessary, are discussed in Chapter 10.

Although assisted dying is unlawful in the UK, the Director of Public Prosecutions (DPP) has issued guidance on how prosecution decisions are made in response to a request from the courts, following an action brought by Debbie Purdy. Thus, there are now guidelines that indicate what circumstances are likely to weigh either in favour of, or against, a prosecution. Nevertheless, the law itself is unchanged by the DPP’s guidance: for a clinician to act to end a patient’s life remains a criminal offence.

FURTHER READING

British Medical Association. Assisted Suicide: Guidance for Doctors in England, Wales and Northern Ireland. London: BMA; 2010.

General Medical Council. Treatment and Care Towards the End of Life. London: GMC; 2010.

IMCA. Making Decisions: The Independent Mental Capacity Advocate (IMCA) Service. London: Department of Health; 2009.

UKHL. R (Purdy) v Director of Public Prosecutions [2009] UKHL 45.

Mental health and consent

The vast majority of people being treated for psychiatric illness have capacity to make choices about healthcare. However, there are some circumstances in which mental illness compromises an individual’s capacity to make his or her own decisions. In such circumstances, many countries have specific legislation that enables people to be treated without consent on the basis that they are at risk to themselves and/or to others.

People who have, or are suspected of having, a mental disorder may be detained for assessment and treatment in England and Wales under the Mental Health Act 2007 (which amended the 1983 statute). There is one definition of a mental disorder for the purposes of the law: The Mental Health Act 2007 defines a mental disorder as ‘any disorder or disability of the mind’. Addiction to drugs and alcohol is excluded from the definition. Appropriate medical treatment should be available to those who are admitted under the Mental Health Act. In addition to assessment and treatment in hospital, the legislation provides for Supervised Community Treatment Orders, which consist of supervised community treatment after a period of detention in hospital. The law is tightly defined with multiple checks and limitations which are essential given the ethical implications of detaining and treating someone against his or her will.

Even in situations in which it is lawful to give a detained patient psychiatric treatment compulsorily, efforts should be made to obtain consent if possible. For concurrent physical illness, capacity should be assessed in the usual way. If the patient does have capacity, consent should be obtained for treatment of the physical illness. If a patient lacks capacity because of the severity of a psychiatric illness, treatment for physical illness should be given on the basis of best interests or with reference to a proxy or advance decision, if applicable. If treatment can be postponed without seriously compromising the patient’s interests, consent should be sought when the patient once more has capacity.

Consent and children

Where a child does not have the capacity to make decisions about his or her own medical care, treatment will usually depend upon obtaining proxy consent. In the UK, consent is sought on behalf of the child from someone with ‘parental responsibility’. In the absence of someone with parental responsibility, e.g. in emergencies where treatment is required urgently, clinicians proceed on the basis of the child’s best interests.

Sometimes parents and doctors disagree about the care of a child who is too young to make his or her own decisions. Here, both national and European case law demonstrates that the courts are prepared to override parental beliefs if they are perceived to compromise the child’s best interests. However, the courts have also emphasized that a child’s best medical interests are not necessarily the same as a child’s best overall interests. Whenever the presenting patient is a child, clinicians are dealing with a family unit. Sharing decisions, and paying attention to the needs of the child as a member of a family, are the most effective and ethical ways of practising.

As children grow up, the question of whether a child has capacity to make his or her own decisions is based on principles derived from a case called Gillick v. West Norfolk and Wisbech Area Health Authority, which determined that a child can make a choice about his or her health where:

The patient, although under 16, can understand medical information sufficiently

The patient, although under 16, can understand medical information sufficiently

The doctor cannot persuade the patient to inform, or give permission for the doctor to inform, his or her parents

The doctor cannot persuade the patient to inform, or give permission for the doctor to inform, his or her parents

In cases where a minor is seeking contraception, the patient is very likely to have sexual intercourse with or without adequate contraception

In cases where a minor is seeking contraception, the patient is very likely to have sexual intercourse with or without adequate contraception

The patient’s mental or physical health (or both) are likely to suffer if treatment is not provided

The patient’s mental or physical health (or both) are likely to suffer if treatment is not provided

It is in the patient’s best interests for the doctor to treat without parental consent.

It is in the patient’s best interests for the doctor to treat without parental consent.

The Gillick case recognized that children differ in their abilities to make decisions and established that function, not age, is the prime consideration when considering whether a child can give consent. Situations should be approached on a case-by-case basis, taking into account the individual child’s level of understanding of a particular treatment. It is possible (and perhaps likely) that a child may be considered to have capacity to consent to one treatment but not another. Even where a child does not have capacity to make his or her own decision, clinicians should respect the child’s dignity by discussing the proposed treatment even if the consent of parents also has to be obtained.

In the UK, once a child reaches the age of 16, the Mental Capacity Act 2005 states that he or she should be treated as an adult save for the purposes of advance decision-making and appointing a lasting power of attorney.

Confidentiality

Confidentiality is essential to therapeutic relationships. If clinicians violate the privacy of their patients, they risk causing harm, disrespect autonomy, undermine trust, and call the medical profession into disrepute. The diminution of trust is a significant ethical challenge, with potentially serious consequences for both the patient and the clinical team. Within the UK, confidentiality is protected by common and statutory law. Some jurisdictions make legal provision for privacy. Doctors who breach the confidentiality of patients may face severe professional and legal sanctions. For example, in some jurisdictions, to breach a patient’s confidentiality is a statutory offence.

Respecting confidentiality in practice

Patients should understand that information about them will be shared with other clinicians and healthcare workers involved in their treatment. Usually, by giving consent for investigations or treatment, patients are deemed to give their implied consent for information to be shared within the clinical team. Very rarely, patients might object to information being shared even within a team. In such situations, the advice is that the patient’s wish should be respected unless it compromises treatment. In almost all clinical circumstances, therefore, the confidentiality of patients must be respected. Unfortunately, confidentiality can be easily breached inadvertently. For example, clinical conversations take place in lifts, corridors and cafes. Even on wards, confidentiality is routinely compromised by the proximity of beds and the visibility of whiteboards containing medical information. Students and doctors should be alert to the incidental opportunities for breaches of confidentiality and seek to minimize their role in unwittingly revealing sensitive information.

When confidentiality must or may be breached

The duty of confidence is not absolute. Sometimes, the law requires that clinicians must reveal private information about patients to others, even if they wish it were otherwise (Box 1.5). There are also circumstances in which a doctor has the discretion to share confidential information within defined terms. Such circumstances highlight the ethical tension between the rights of individuals and the public interest.

Aside from legal obligations, there are three broad categories of qualifications that exist in respect of the duty of confidentiality, namely:

1. The patient has given consent.

2. It is in the patient’s best interests to share the information but it is impracticable or unreasonable to seek consent.

These three categories are useful as a framework within which to think about the extent of the duty of confidentiality and they also require considerable ethical discretion in practice, particularly in relation to situations where sharing confidential information might be considered to be in the ‘public interest’. In England and Wales, there is legal guidance on what constitutes sufficient ‘public interest’ to justify sharing confidential information, which is derived from the case of W v. Egdell. In that case, the Court of Appeal held that only the ‘most compelling circumstances’ could justify a doctor acting contrary to the patient’s perceived interest in the absence of consent. The court stated that it would be in the public interest to share confidential information where:

there is a real and serious risk of harm

there is a real and serious risk of harm

there is a risk to an identifiable individual or individuals.

there is a risk to an identifiable individual or individuals.

Consent should be sought wherever possible, and disclosure on the basis of the ‘public interest’ should be a last resort. Each case must be weighed on its own individual merits and a clinician who chooses to disclose confidential information on the ground of ‘public interest’ must be prepared to justify his or her decision. Even where disclosure is justified, confidential information must be shared only with those who need to know.

If there is perceived public interest risk, does a doctor have a duty to warn? In some jurisdictions, there is a duty to warn but in England and Wales, there is no professional duty to warn others of potential risk. The judgement of W v. Egdell provides a justification for breaches of confidence in the public interest but it does not impose an obligation on clinicians to warn third parties about potential risks posed by their patients.

FURTHER READING

British Medical Association. Confidentiality and Disclosure of Health Information: Toolkit. London: BMA; 2009.

General Medical Council. Confidentiality: Protecting and Providing Information. London: GMC; 2009. www.gmc-uk.org.

Resource allocation

Resources should be considered broadly to encompass all aspects of clinical care, i.e. they include time, knowledge, skills and space, as well as treatment. In circumstances of scarcity, waste and inefficiency of any resource are of ethical concern.

Access to healthcare is considered to be a fundamental right and is captured in international law since it was included in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. However, resources are scarce and the question of how to allocate limited resources is a perennial ethical question. Within the UK, the courts have made it clear that they will not force NHS Trusts to provide treatments which are beyond their means. Nevertheless, the courts also demand that decisions about resources must be made on reasonable grounds.

Fairness

Both ethically and legally, prejudice or favouritism is unacceptable. Methods for allocating resources should be fair and just. In practice, this means that scarce resources should be allocated to patients on the basis of their comparative need and the time at which they sought treatment. It is respect by clinicians for these principles of equality – equal need and equal chance – that fosters fairness and justice in the delivery of healthcare. For example, a well-run Accident and Emergency Department will draw on the principles of equality of need and chance to:

decide who to treat first and how

decide who to treat first and how

offer treatment that has been shown to deliver optimal results for minimal expense

offer treatment that has been shown to deliver optimal results for minimal expense

use triage to determine which patients are most in need and ensure that they are seen first; the queue (or waiting list) being based on need and time of presentation.

use triage to determine which patients are most in need and ensure that they are seen first; the queue (or waiting list) being based on need and time of presentation.

People should not be denied potentially beneficial treatments on the basis of their lifestyles. Such decisions are almost always prejudicial. For example, why single out smokers or the obese for blame, as opposed to those who engage in dangerous sports? Patients are not equal in their abilities to lead healthy lives and to make wise healthcare choices.

Education, information, economic worth, confidence and support are all variables that contribute to, and socially determine health and wellbeing. As such, to regard all people as equal competitors and to reward those who in many ways are already better off, is unjust and unfair.

Global perspectives

Increasingly, resource allocation is being considered from an international or global perspective. Beyond the boundaries of the NHS and the borders of the UK, the moral questions about the availability of, and access to, effective healthcare are rightly attracting the attention of ethicists and clinicians. Anyone who is training for, or working in, medicine in the 21st century should consider fundamental moral questions about resource allocation, in particular those being raised by issues such as:

Professional competence and mistakes

Doctors have a duty to work to an acceptable professional standard. There are essentially three sources that inform what it means to be a ‘competent’ doctor, namely:

In practice, there is frequently overlap and interaction between the categories, e.g. a doctor may be both a defendant in a negligence action and the subject of fitness to practise procedures. Professional bodies are established by, and work within, a legal framework and in order to implement policy, legislation is required and interpretative case law will often follow.

Standards and the law

In most countries, the law provides the statutory framework within which the medical profession is regulated. For example, in the UK, it is the function of the GMC to maintain the register of medical practitioners, provide ethical guidance, guide and quality assure medical education and training, and conduct fitness to practise procedures. Therefore it is the GMC that defines standards of professional practice and has responsibility for investigation when a doctor’s standard of practice is questioned.

Clinicians have a responsibility not only to reflect on their own practice, but also to be aware of and, if necessary, respond to the practice of colleagues even in the absence of formal ‘line management’ responsibilities. In England and Wales, for example, the Public Interest Disclosure Act 1998 provides statutory protection for those who express formal concern about a colleague’s performance, provided the expression of concern:

FURTHER READING

General Medical Council. Duties of a Doctor Registered with the GMC. London: GMC; http://www.gmc-uk.org/guidance/ethical_guidance/7162.asp.

Clinical negligence

Negligence is a civil claim where damage or loss has arisen as a result of an alleged breach of professional duty such that the standard of care was not, on the balance of probabilities, that which could be reasonably expected.

Of the components of negligence, duty is the simplest to establish: all doctors have a duty of care to their patients (although the extent of that duty in emergencies and social situations is uncertain and contested in relation to civil law). Whether a doctor has discharged his or her professional duty adequately is determined by expert opinion about the standards that might reasonably be expected and his or her conduct in relation to those standards. If a doctor has acted in a way that is consistent with a reasonable body of his peers and his actions or omissions withstand logical analysis, he or she is likely to meet the expected standards of care. Lack of experience is not taken into account in legal determinations of negligence.

The commonest reason for a negligence action to fail is causation, which is notoriously difficult to prove in clinical negligence claims. For example, the alleged harm may have occurred against the background of a complex medical condition or course of treatment, making it difficult to establish the actual cause.

Clinical negligence remains relatively rare and undue fear of litigation can lead to defensive and poor practice. All doctors make errors and these do not necessarily constitute negligence or indicate incompetence. Inherent in the definition of incompetence is time, i.e. on-going review of a doctor’s practice to see whether there are patterns of error or repeated failure to learn from error. Regulatory bodies and medical defence organizations recommend that doctors should be honest and apologetic about their mistakes, remembering that to do so is not necessarily an admission of negligence (see p. 14). Such honesty and humility, aside from its inherent moral value, has been shown to reduce the prospect of patient complaints or litigation.

Professional bodies

Professional bodies have diverse but often overlapping roles in developing, defining and revising standards for doctors. The principal publications in which the GMC sets out standards and obligations relating to competence and performance, are ‘Duties of a Doctor’ and ‘Good Medical Practice’.

Policy

There have been an exponential number of policy reforms that have shaped the ways in which the medical competence and accountability agendas have evolved. One of the most notable is the increase in the number of organizations concerned broadly with ‘quality’ and performance. The increased scrutiny of doctors’ competence has found further policy translation in the development of appraisal schemes and the revalidation process. There have been other policy initiatives that adopt the rhetoric of ‘quality’ such as increased use of clinical and administrative targets, private finance initiatives and the development of specialist screening facilities and treatment centres.

The issue of professional accountability in medicine is a hot topic. The law, professional guidance and policy documentation provide a starting point for clinicians. Complaints and possible litigation are often brought by patients who feel aggrieved for reasons that may be unconnected with the clinical care that they have received. When patients are asked about their decisions to complain or to sue doctors, it is common for poor communication, insensitivity, administrative errors and lack of responsiveness to be cited as motivation (see p. 7). There is less to fear than doctors sometimes believe. The courts and professional bodies are neither concerned with best practice, nor with unfeasibly high standards of care. What is expected is that doctors behave in a way that accords with the practice of a reasonable doctor – and the reasonable doctor is not perfect. As long as clinicians adhere to some basic principles, it is possible to practise defensible rather than defensive medicine. It should be reassuring that complaints and litigation are avoidable, simply by developing and maintaining good standards of communication, organization and administration – and good habits begin in medical school. In particular, effective communication is a potent weapon in preventing complaints and, ultimately, encounters with the legal and regulatory systems.

Communication

Communication in healthcare

Communication in healthcare is fundamental to achieving optimal patient care, safety and health outcomes. The aim of every healthcare professional is to provide care that is evidence-based and unconditionally patient-centred. Patient-centred care depends on a consulting style that fosters trust and communication skills, with the attributes of flexibility, openness, partnership, and collaboration with the patient.

Doctors work in multiprofessional teams. As modern healthcare has progressed, it is now more effective, more complex and more hazardous. Successful communication within healthcare teams is therefore vital.

What is patient-centred communication?

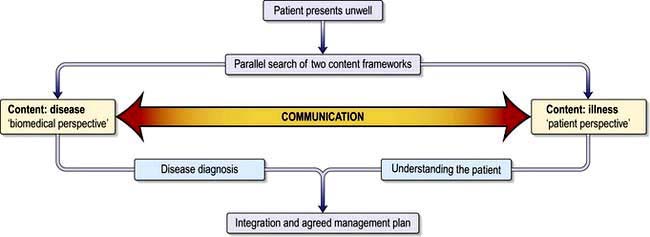

Patient-centred communication involves reaching a common ground about the illness, its treatment, and the roles that the clinician and the patient will assume (Fig. 1.1). It means discovering and connecting both the biomedical facts of the patient’s illness in detail and the patient’s ideas, concerns, expectations and feelings. This information is essential for diagnosis and appropriate management and also to gain the patient’s confidence, trust and involvement.

Figure 1.1 The patient-centred clinical interview.

(Adapted from: Levenstein JH. In: Stewart M, Roter D, eds. Communicating with Medical Patients. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1989, with permission.)

The traditional approach of ‘doctor knows best’ with patients’ views not being considered is very outdated. This change is spreading worldwide and is not just societal but driven by evidence about improved health outcome. There are three main reasons for this:

Patients increasingly expect information about their condition and treatment options and want their views taken into account in deciding treatment. This does not mean clinicians totally abdicate power. Patients want their doctors’ opinions and expertise and may still prefer to leave matters to the clinician.

Patients increasingly expect information about their condition and treatment options and want their views taken into account in deciding treatment. This does not mean clinicians totally abdicate power. Patients want their doctors’ opinions and expertise and may still prefer to leave matters to the clinician.

Many health problems are long-term conditions and patients may become experts actively involved in self-care. They have to manage their conditions and reduce risks from lifestyle habits in a partnership approach to care.

Many health problems are long-term conditions and patients may become experts actively involved in self-care. They have to manage their conditions and reduce risks from lifestyle habits in a partnership approach to care.

A distinguishing feature of the healthcare professions is that patients expect humanity and empathy from their doctors as well as competence. Clinicians can usually offer practical help with patients’ concerns and expectations but, if not, they can always listen supportively.

A distinguishing feature of the healthcare professions is that patients expect humanity and empathy from their doctors as well as competence. Clinicians can usually offer practical help with patients’ concerns and expectations but, if not, they can always listen supportively.

Patient-centred communication requires a good balance between:

What are the effects of communication?

Enormous benefits accrue from good communication (Box 1.6). Patients’ problems are identified more accurately and efficiently, expectations for care are agreed and patients and clinicians experience greater satisfaction. Poor communication results in missed problems (Box 1.7) and concerns, strained relationships, complaints and litigation.

![]() Box 1.7

Box 1.7

Patient reports of failure to identify problems in interviews

54% of complaints and 45% of concerns were not elicited

54% of complaints and 45% of concerns were not elicited

50% of psychological problems not elicited

50% of psychological problems not elicited

80% of breast cancer patients’ concerns remain undisclosed

80% of breast cancer patients’ concerns remain undisclosed

In 50% of visits, patients and doctors disagreed on the main presenting problem

In 50% of visits, patients and doctors disagreed on the main presenting problem

In 50% of cases, patient’s history was blocked by interruption within 24 seconds

In 50% of cases, patient’s history was blocked by interruption within 24 seconds

From: Simpson M, Buckman R, Stewart M et al. The Toronto Consensus Statement. British Medical Journal 1991; 303:1385–1387, with permission.

Diagnostic accuracy

Clinicians commonly interrupt patients after an average 24 seconds, whether or not a patient has finished explaining their problem. Uninterrupted patients will talk for 90 seconds on average (maximum 2.5 minutes). Clinicians are failing if a serious point is raised only as the patient is preparing to leave and this then takes longer.

Health outcomes

These are improved by good communication. Hospital visits, admissions, length of stay and mortality rate are reduced where clinicians used a biopsychosocial approach to managing people with medically unexplained symptoms. Conversely, the main predictive factor for patients developing depression on learning of the diagnosis of cancer was the way their bad news had been broken.

Adherence to treatment

Some 45% of patients are not following treatment advice properly. Errors in use of medications are costly and risk patient safety. Patients may not understand or remember what they were told, whilst others actively decide not to follow advice and commonly do not tell their doctors. Research shows that clinicians rarely check patients’ understanding or views, yet such communication contributes to adherence (Practical Box 1.1).

Patient satisfaction and dissatisfaction

Satisfaction with consultations is largely a result of patients knowing they are:

Satisfaction with a consultation affects psychological wellbeing and adherence to treatment, both of which have a knock-on effect on clinical outcomes. It also reduces patient complaints and litigation (Box 1.8). Some 70% of lawsuits are a result of poor communication rather than failures of biomedical practice. Complaints and lawsuits represent only the tip of the iceberg of discontent, as revealed by surveys of patients in hospital and primary care.

Clinician satisfaction

Healthcare professionals have a very high rate of occupational stress and burnout, which is costly both to them and to health services. Notwithstanding pressure from staffing shortages and inadequate resources, it is the quality of relationships with patients and colleagues that affects clinician satisfaction and happiness.

Time and costs

Those who integrate patient-centred communication into all interviews actually save time and also reduce non-essential investigations and referrals, which waste resources. Patients given the latest evidence on treatment options commonly choose more conservative management with no adverse effects on health outcomes. This has potential for considerable savings in health budgets.

Barriers and difficulties in communication

Communication is not straightforward (Box 1.9). Time constraints can prevent both doctors and patients from feeling that they have each other’s attention and that they fully understand the problem from each other’s perspective. Underestimation of the influence of psychosocial issues on illness and their costs to healthcare means clinicians may resort to avoidance strategies when they fear the discussion will unleash emotions too difficult to handle, upset the patient or take too much time (Box 1.10).

![]() Box 1.9

Box 1.9

Common barriers and difficulties in communication

| Clinician factors | Shared factors | Patient factors |

|---|---|---|

![]() Box 1.10

Box 1.10

Strategies that doctors use to distance themselves from patients’ worries

| Patient says: ‘I have this headache and I’m worried …’ | |

|---|---|

Selective attention to cues |

‘What is the pain like?’ |

Normalizing |

‘It’s normal to worry. Where is the pain?’ |

Premature reassurance |

’Don’t worry. I’m sure you’ll be fine’ |

False reassurance |

‘Everything is OK’ |

Switching topic |

‘Forget that. Tell me about …’ |

Passing the buck |

‘Nurse will tell you about that’ |

Jollying along |

‘Come on now, look on the bright side’ |

Physical avoidance |

Passing the bedside without stopping |

From Maguire P. Communication Skills for Doctors. London: Arnold; 2000, with permission.

Patients for their part will not disclose concerns if they are anxious and embarrassed, or sense that the clinician is not interested or thinks that their complaints are trivial. Many patients have poor knowledge of how their body works and struggle to understand new information provided by doctors. Some concepts may be too unfamiliar to make sense of, even if described simply, and patients may be too embarrassed to say they don’t understand. For example, when explaining fasting blood sugar levels to newly diagnosed diabetics it was found that many did not realize that there is sugar in their blood.

Clinicians are human and are often rushed and stressed. They work against the clock and in fallible systems. But as professionals, it is they, together with healthcare managers, who bear the responsibility for dealing with these difficulties and problems, not the patient.

FURTHER READING

Ambady N, LaPlante D, Nguyen T et al. Surgeon’s tone of voice: a clue to malpractice history. Surgery 2002; 132(1):5–9.

Coulter A, Ellins J. Effectiveness of strategies for informing, educating, and involving patients. BMJ 2007; 335:24–27.

Margalit A, El-Ad A. Costly patients with unexplained medical symptoms. A high-risk population. Patient Educ Couns 2008; 70:173–178.

The medical interview

Structure and skills for effective interviewing

Clinicians conduct some 200 000 medical interviews during their careers. Flexibility is a key skill in patient-centred communication because each patient is different. A framework helps clinicians use time productively. The example below applies to a first consultation and may vary slightly in a follow-up appointment or emergency visit.

There are seven essential steps in the medical interview:

1. Building a relationship

Because patients are frequently anxious and may feel unwell, introductions and first impressions are critical to create rapport and trust. Without rapport and trust, effective communication is impossible. Well-organized arrangements for appointments, reception and punctuality put patients at ease. Clinicians’ non-verbal messages, body language and unspoken attitudes have a huge impact on the emotional tone of the interview. Seating arrangements, eye contact, facial expression and tone of voice should all convey friendliness, interest and respect.

2. Opening the discussion

The aim is to obtain all the patients’ concerns, remembering that they usually have at least three (range 1–12). Ask ‘What would you like to discuss today?’ or ‘What problems have brought you to see me today?’

Listen attentively without interrupting. Ask ‘And is there something else?’ to screen for any other problems before exploring the history in detail.

Only when all concerns are identified can the agenda be prioritized, balancing the patients’ main concerns with the clinician’s medical priorities.

3. Gathering information

The components of a complete history are shown in Table 1.1.

Table 1.1 Components of a medical interview

Listening skills

Attentive listening is a necessary communication skill. Ask the patient to tell the story of the problem in their own words from when it first started up to the present. Patients will recognize clinicians are listening if they look at them and not the notes or computer. Occasional nods will encourage the patient to continue. Avoid interrupting before the patient has finished talking.

Questioning styles

The way a clinician asks questions determines whether the patient speaks freely or just gives one word or brief answers (Practical Box 1.2). Start with open questions (‘What problems have brought you in today?’) and move to screening (‘Is there anything else?’), focused (‘Can you tell me more about the pain?’) and closed questions (‘Where is the pain?’). Open methods allow clinicians to listen and to generate their problem-solving approach. Closed questions are necessary to check specific symptoms but if used too early, they may narrow down and lead to inaccuracies by missing patients’ problems.

![]() Practical Box 1.2

Practical Box 1.2

Questioning style

Closed questioning style

Open questioning style

Doctor: ‘Tell me about the pain you’ve been having.’ (open/focused Q)

Patient: ‘Well it’s been getting worse over the past few weeks and waking me up at night. It’s just here (points to sternum), it’s very sharp and I get a burning and bad acid taste in the back of my throat. I try to burp to clear it. I’ve taken antacids but they don’t seem to be helping now and I’m a bit worried about it. I’m losing sleep and I’ve got a busy workload so that’s a worry too.’

Doctor: ‘I see. So it’s bothering you quite a lot. Anything else you’ve noticed?’ (empathic statement, open screening Q)

Patient: ‘I’ve noticed I get it more after I’ve had a few drinks. I have been drinking and smoking a bit more recently. Actually I’ve been getting lots of headaches too which I’ve just taken Ibuprofen for.’

Doctor: ‘You say you are worried, is there anything in particular that concerns you?’ (picks up on patient’s cue and uses reflecting question)

Patient: ‘I wondered if I might be getting an ulcer.’

Doctor: ‘I see. So this sharp pain under your breastbone with some acid reflux for several weeks is worse at night and aggravated by drinking and smoking but not relieved by antacids. You are busy at work, getting headaches, drinking and smoking a bit more and not sleeping well. You’re concerned this could be an ulcer.’ (summarizing)

Patient: ‘Yes, a friend had problems like this.’

Doctor: ‘I can appreciate why you might be thinking that then.’ (validation)

Patient: ‘Yes and he had to have a “scope” so I wondered whether I would need one?’(expectation)

Doctor: ‘Well, let me explain first what I think this is and then what I would recommend next …’ (signposting)

Leading questions which imply the expected answer (‘You’ve given up drinking haven’t you?’) risk inaccurate responses as patients may go along with the clinician rather than disagree.

4. Understanding the patient

Finding out the patient’s perspective is an essential step towards achieving common ground.

Ideas, concerns and expectations (ICE)

Patients seek help because of their own ideas or concerns about their condition. If these are not heard, they may think the clinician has not got things right and then not follow advice. Moreover, any misconceptions which could affect their symptoms and ability to recover will go uncorrected. A patient’s views can emerge if the clinician listens carefully and picks up on cues. But if they do not, it is necessary to ask specific questions, e.g.:

‘What were you worried this might be?’

‘What were you worried this might be?’

‘Are there any particular concerns you have about …?’

‘Are there any particular concerns you have about …?’

‘Was there anything you were hoping we might do about this?’

‘Was there anything you were hoping we might do about this?’

Hearing patients’ ideas, acknowledging their concerns and empathizing, are essential steps in engaging a patient’s trust, and beginning to ‘treat the whole patient’. The example in Practical Box 1.2 also shows how information that may be biomedically relevant emerges while listening to patients.

Non-verbal communication

In adult conversation, some 5% of meaning derives from words, 35% from tone of voice and 60% from body language and non-verbal communication. When there is mismatch between words and tone, the non-verbal communication elements hold the truer meaning. Patients who are anxious, uneasy, puzzled or confused are more likely to communicate this through expression and/or restless activity, for example of the feet and hands, than to tell the clinician outright. The observant clinician can pick up on this: ‘You seem uneasy about what I have said …’, thus inviting the patient to share their concerns.

Empathizing

Empathy has been described as ‘imagination for others’. It is different from sympathy (feeling sorry for the patient), which rarely helps. Empathy is a key skill in building the patient–clinician relationship and is highly therapeutic. The starting point is attentive listening and observing patients to try and understand their predicament. This understanding then needs to be conveyed back in a supportive way. Whilst empathy is about trying to understand, the phrase ‘I understand’ may be met with ‘how could you!’ It is usually more helpful to reflect back using some of the patient’s own words and ideas. For example, by saying: ‘It sounds like …’ (patient heard); ‘I can see you are upset’ (patient seen); ‘I realize that this is a shock’ (acknowledgement); ‘I can tell you that most people in your circumstances get angry’ (accepting the patient).

Like other communication skills, empathy can be taught and learnt but it has to be genuine and cannot be counterfeited by a repertoire of routine mannerisms.

5. Sharing information

Tailoring information to what the patient wants to know and the level of detail they prefer helps them understand.

Patients generally want to know ‘is this problem serious and how will it affect me; what can be done about it; and what is causing it?’ Research shows patients cannot take in explanations about cause if they are still worrying about the first two concerns.

Information must be related not only to the biomedical facts, but tailored to patients’ ideas and concerns.

Information must be related not only to the biomedical facts, but tailored to patients’ ideas and concerns.

Most patients want to be fully informed, irrespective of socioeconomic group.

Most patients want to be fully informed, irrespective of socioeconomic group.

Most patients of all ages will understand and recall 70–80% of even the most unfamiliar, complex or alarming information if given along the guidelines shown in Practical Box 1.3.

Most patients of all ages will understand and recall 70–80% of even the most unfamiliar, complex or alarming information if given along the guidelines shown in Practical Box 1.3.

![]() Practical Box 1.3 Giving information

Practical Box 1.3 Giving information

The 3E Model: Explore, Explain, Explore

Explain

Chunk and check. Give information in assimilable chunks, one thing at a time. Check after each chunk that the patient is understanding.

Signpost. ‘I’ll explain first of all …’; ‘Can I move on now to explain treatment options …?’

Link. Explain the cause and effect of the condition in the context of the patient’s symptoms, e.g. ‘The reason you are experiencing … is because …’

Plain language. Clear, concise language; translate any unavoidable medical terms and write them down.

Aid recall. Simple diagrams, leaflets, recommend websites and support organizations.

6. Reaching agreement on management

Understanding the situation is the first step but the clinician and patient also then need to agree on the best course for possible investigations and treatments.

Clinical records

All medical interviews should be well documented. Good records are the responsibility of everyone in the healthcare team (Table 1.2), as is maintenance of confidentiality. They are vital in providing best care, reducing error and ensuring patient safety.

Table 1.2 Essentials of record-keeping

Records should include: |

aGMC Good Medical Practice 2012. bMPS Guide to Medical Records 2010; http://www.medicalprotection.org/uk/booklets/medical-records.

In many countries, patients have the right to see their records, which provide essential information when a complaint or claim for negligence is made. They are also valuable as part of audit aimed at improving standards of healthcare.

Computer records are increasingly replacing written records. They include more information and overcome problems of legibility, for example prescription errors are reduced by 66% when electronic prescriptions replace handwritten ones. With adequate data protection, use of electronic records via the internet holds immense potential for unifying patient record systems and allowing access electronically by members of the healthcare team in primary, secondary and tertiary care sectors.

FURTHER READING

Royal College of Physicians. A Clinician’s Guide to Record Standards 2009; http://www.rcplondon.ac.uk/clinical-standards/hiu/medical-records.

Team communication

Modern healthcare is complex and patients are looked after by multiple healthcare professionals working in shifts. Effective team communication is absolutely essential and this is never more vital than when people are busy or a patient is critically ill. Contexts for team communication include handover, requesting help, accepting referrals and communication in the operating theatre. Lessons from industries such as aviation and energy show how to reduce error caused by poor communication.

Problems arise when information is not transmitted, is misunderstood or is not recorded. Communication styles vary. Some people are indirect and more elaborate in their speech, whilst others go straight to the point, leaving out detail and their own rationale. Each type can feel irritated, offended or puzzled by the other and most complaints in teams relate to communication. Handover between teams is helped when everyone adopts a clear system.

Frameworks such as SBAR (Situation–Background–Assessment–Recommendation) use standardized prompt questions in four sections to ensure team members share concise and focused information at the correct level of detail (Box 1.11). This increases patient safety.

![]() Box 1.11 SBAR

Box 1.11 SBAR

A structure for team communication

S – Situation |

|

B – Background |

|

A – Assessment |

|

R – Recommendation (examples) |

Problems also occur when people have differing opinions about treatment, which are not resolved. Hierarchies make it harder for people to speak up. This can be dangerous if, for example, a nurse or junior doctor feels unable to point out an error, offer information or ask a question. Hinting and hoping is not good communication. Team leaders who ‘flatten’ the hierarchy by knowing and using people’s names, routinely have briefings and debriefings, do not let their own self-image override doing the right thing and positively encourage colleagues to speak up, reduce the number of adverse events. Teamwork requires collaboration, open sharing of ideas and being prepared to discuss weaknesses and errors. These skills can be learned.

Communication on discharge is just as essential and primary care physicians need sufficient information, including information about medication, to safely continue care.

FURTHER READING

BMA. Safe Handover: Safe Patients. Guidance on Clinical Handover for Clinicians and Managers. London: British Medical Association 2009; http://www.bma.org.uk/employmentandcontracts/working_arrangements/Handover.jsp.

SBAR (Situation–Background–Assessment–Recommendation) films at: http://www.institute.nhs.uk/safer_care/safer_care/sbar_escalation_films.html.

Communicating in difficult situations

The skills outlined previously form the basis of any patient interview but some interviews are particularly difficult:

Breaking bad news

Bad news is any information which is likely to drastically alter a patient’s view of the future. The way news is broken has an immediate and long-term effect. When skilfully performed, the patient and family are enabled to understand, cope and make the best of even very bad circumstances. These interviews are difficult because biomedical measures may be of little or no help, and patients are upset and can react unpredictably. The clinician may also feel upset, more so if there is an element of medical mishap. The two most difficult things that clinicians report are how to be honest with the patient whilst not destroying hope, and how to deal with the patient’s emotions.

Withholding information from patients or telling only the family is a thing of the past and becoming so even in parts of the world where traditionally disclosure did not occur. Although truth can hurt, deceit hurts more. It erodes trust and deprives patients of information to make choices. Most people now express the wish to be told the truth and the evidence is that patients:

usually know more than anyone realizes and may imagine things worse than they are

usually know more than anyone realizes and may imagine things worse than they are

appreciate clear information even about the worst news and want the opportunity to talk openly and ask questions, rather than join in a charade of deception

appreciate clear information even about the worst news and want the opportunity to talk openly and ask questions, rather than join in a charade of deception

A framework: the S–P–I–K–E–S strategy

Having a framework helps clinicians to present bad news in a factual, unhurried, balanced and empathic fashion whilst responding to each patient.

S – Setting

See the patient as soon as the current information has been gathered.

See the patient as soon as the current information has been gathered.

Ask not to be disturbed and hand bleeps to colleagues.

Ask not to be disturbed and hand bleeps to colleagues.

If possible, the patient should have someone with them.

If possible, the patient should have someone with them.

Choose a quiet place with everyone seated and introduce everyone.

Choose a quiet place with everyone seated and introduce everyone.

Indicate your status, extent of your responsibility toward the patient and the time available.

Indicate your status, extent of your responsibility toward the patient and the time available.

P – Perception

Ask before telling. Find out what has happened to the patient since the last appointment and what has been explained or construed so far. This stage helps gauge the patient’s perception, but should not be too drawn out.

K – Knowledge

If the patient wishes to know:

Give a warning to help the patient prepare: ‘I’m afraid it looks more serious than we hoped.’

Give a warning to help the patient prepare: ‘I’m afraid it looks more serious than we hoped.’

At this point, WAIT: allow the patient to think, and only continue when the patient gives some lead to follow. This pause may be a long one, commonly a matter of minutes, but useful to help patients take in the situation. Patients may shut down and be unable to hear anything further until their thoughts settle down.

At this point, WAIT: allow the patient to think, and only continue when the patient gives some lead to follow. This pause may be a long one, commonly a matter of minutes, but useful to help patients take in the situation. Patients may shut down and be unable to hear anything further until their thoughts settle down.

Give direct information, in small chunks. Avoid technical terms. Check understanding frequently: ‘Is this making sense so far?’ before moving on. Watch for signs the patient can take no more.

Give direct information, in small chunks. Avoid technical terms. Check understanding frequently: ‘Is this making sense so far?’ before moving on. Watch for signs the patient can take no more.

Emphasize which things, for example pain and other symptoms, are fixable and which others are not.

Emphasize which things, for example pain and other symptoms, are fixable and which others are not.

Be prepared for the question: ‘How long have I got?’ Avoid providing a figure to an individual, which is bound to be inaccurate. Common faults are to be overly optimistic. Some patients wish to know survival rates for their condition. Tell them as much as is appropriate. Stress the importance of ensuring that the quality of life is made as good as possible from day to day.

Be prepared for the question: ‘How long have I got?’ Avoid providing a figure to an individual, which is bound to be inaccurate. Common faults are to be overly optimistic. Some patients wish to know survival rates for their condition. Tell them as much as is appropriate. Stress the importance of ensuring that the quality of life is made as good as possible from day to day.

Provide some positive information and hope, tempered with realism.

Provide some positive information and hope, tempered with realism.

E – Empathy

Responding to the patient’s emotions is about the human side of medical care and also helps patients to take in and adjust to difficult information. A range of emotions are experienced in seriously and terminally ill patients (Box 1.12).

Be prepared for the patient to have disorderly emotional responses of some kind. Acknowledge them early on as being what you expect and understand and wait for them to settle before continuing.

Be prepared for the patient to have disorderly emotional responses of some kind. Acknowledge them early on as being what you expect and understand and wait for them to settle before continuing.

Crying can be a release for some patients. Allow time if the patient needs it, rather than rushing in to stop the crying.

Crying can be a release for some patients. Allow time if the patient needs it, rather than rushing in to stop the crying.

Learn to judge which patients wish to be touched and which do not. You can always reach out and touch their chair.

Learn to judge which patients wish to be touched and which do not. You can always reach out and touch their chair.

Keep pausing to allow patients to think and frame their questions.

Keep pausing to allow patients to think and frame their questions.

Watch for shutdown: stop the interview if necessary and arrange to resume later.

Watch for shutdown: stop the interview if necessary and arrange to resume later.

S – Strategy and summary

Patients who have a clear plan for the next and future steps are likely to feel less anxious and uncertain. The clinician must ensure:

The patient has understood what has been discussed because at times of emotion, misconceptions can take root

The patient has understood what has been discussed because at times of emotion, misconceptions can take root

Crucial information is written down to take away

Crucial information is written down to take away

The patient knows how to contact the appropriate team member and thus has a safety net in place; when the next appointment is (preferably soon), who it is with and its purpose

The patient knows how to contact the appropriate team member and thus has a safety net in place; when the next appointment is (preferably soon), who it is with and its purpose

Family members are invited to meet the clinicians as the patient wishes and further sources of information are provided

Family members are invited to meet the clinicians as the patient wishes and further sources of information are provided

FURTHER READING

Lloyd M, Bor R. Communication Skills in Medicine, 3rd edn. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 2009.

Silverman J, Kurtz Z, Draper J. The Calgary-Cambridge guide: a guide to the medical interview. In: Skills for Communicating with Patients, 2nd edn. Abingdon: Radcliffe Medical Press; 2005, at: http://www.skillscascade.com/index.html.

FURTHER READING

Baile WF, Lenzi R, Kudelka AP et al. SPIKES – a six-step protocol for delivering bad news: application to the patient with cancer. Oncologist 2000; 5:302–311.

Chaturvedi SK. Truth telling and communication skills. Indian J Psychiatry 2009; 51:227.

Cheng SY, Hu WY, Liu WJ. Good death study of elderly patients with terminal cancer in Taiwan. Palliat Medic 2008; 22:626–632.

Clayton JM, Hancock K, Parker S et al. Sustaining hope when communicating with terminally ill patients and their families: a systematic review. Psychooncology 2008; 17:641–659.

Follow-up

Bad news is a process and not a one-off. Patients may well not remember everything from the last visit and recapping is necessary. Always start by asking what they have understood so far. It is extremely distressing for patients to hear conflicting things from different clinicians. Keep colleagues informed and document accurately what was said to a patient and the patient’s wishes.

The move from active treatment to palliative care is a difficult stage in bad news. Patients want to know what happens next. They want to know ‘Will I be in pain?’; ‘Can I stay at home?’; and ‘How long do I have?’ Give clear answers with acknowledgement of any uncertainty. The priorities in patient care now are: relief of symptoms, quality of life and enabling the patient to settle family matters or unfinished business.

The clinician’s role is to mediate between the patient, other medical staff and the patient’s relatives whilst continuing to be an empathic and caring doctor.

When things go wrong

When things go wrong, as inevitably they do at some time, even in the best of medical care, it is distressing for all concerned. Doctors need to communicate honestly and clearly to minimize distress and act immediately to put matters right, if that is possible. The consultation that occurs after an adverse experience is crucial in influencing any decision to sue.

Being open is recognized as good practice internationally. Doctors should offer an apology and explain fully and promptly what has happened, and the likely short-term and long-term effects of any harm. Reluctance to say ‘sorry’ comes from a fear that it is an admission of fault, which later compromises liability, but guidelines from official bodies emphasize that this is not so. As well as being morally right, an honest approach decreases the trauma felt by patients and relatives following an adverse event and is more likely to lead to forgiveness. Examples of an open approach in the USA, Australia and Singapore have actually reduced costs of complaints.

Having a clear framework also helps to reduce clinicians’ stress and develop their professional reputation for handling difficult situations properly.

Complaints