Suicide and self-harm (see also p. 909)

Suicide accounts for 2% of male and 1% of female deaths in England and Wales each year, equivalent to a rate of 8 per 100 000. The rate increases with age, peaking for women in their 60s and for men in their 70s. Suicide is the second most common cause of mortality in 15- to 34-year-olds. Approximately 15% of people who have suffered a severe depressive disorder (requiring admission) will eventually commit suicide, with 6% doing so in the 10 years after their first admission. Suicide rates in schizophrenia sufferers are likewise high, being 20–50 times the rate in the general population; 20–40% of people with schizophrenia make suicide attempts, and 9–13% are successful.

The highest rates of suicide have been reported in rural southern India (148/100 000 in young women and 58/100 000 in young men) and in eastern Europe (30–40/100 000), while the lowest are those of Spain (3.9/100 000) and Greece (2.8/100 000), but such variations may reflect differences in reporting, which may be related to religion, as much as genuine differences. The provision of mental health care to suicidal individuals varies greatly around the world, with a recent WHO study suggesting that most receive no treatment at all. Factors that increase the risk of suicide are indicated in Table 23.16.

Table 23.16 Factors that increase the risk of suicide

Male sex

Older age

Living alone

Immigrant status

Recent bereavement, separation or divorce

Recent loss of a job or retirement

Living in a socially disorganized area

Family history of affective disorder, suicide or alcohol misuse

Previous history of affective disorder, alcohol or drug misuse

Previous suicide attempt

Addiction to alcohol or drugs

Severe depression or early dementia

Incapacitating painful physical illness

|

A distinction must be drawn between those who attempt suicide – self-harm (SH) – and those who succeed (suicides):

The majority of cases of SH occur in people under 35 years of age.

The majority of cases of SH occur in people under 35 years of age.

The majority of suicides occur in people aged over 60.

The majority of suicides occur in people aged over 60.

Suicides are more common in men, while SH is more common in women.

Suicides are more common in men, while SH is more common in women.

Suicides are more common in older men, although rates are falling. Rates in young men are rising fast throughout the UK and Europe.

Suicides are more common in older men, although rates are falling. Rates in young men are rising fast throughout the UK and Europe.

Suicides in women are slowly falling in the UK.

Suicides in women are slowly falling in the UK.

Approximately 90% of cases of SH involve self-poisoning.

Approximately 90% of cases of SH involve self-poisoning.

A formal psychiatric diagnosis usually can be made retrospectively in suicide, but is unusual in SH.

A formal psychiatric diagnosis usually can be made retrospectively in suicide, but is unusual in SH.

There is, however, an overlap between SH and suicide. Between 1% and 2% of people who attempt suicide will kill themselves in the year following SH. The risk of suicide stays elevated in those with SH, with 0.5% per annum committing suicide in the following 20 years. In the UK, there are 100 000 cases of SH each year, and the overwhelming majority of these are seen and treated within accident and emergency departments.

The guidelines (Box 23.11) for the assessment of such patients will help ensure that the risk factors relating to suicide are covered. Indications for referral to a psychiatrist before discharge from hospital are also given.

Box 23.11

Box 23.11

Guidelines for the assessment of patients who harm themselves

Questions to ask: of concern if positive answer

Was there a clear precipitant/cause for the attempt?

Was there a clear precipitant/cause for the attempt?

Was the act premeditated or impulsive?

Was the act premeditated or impulsive?

Did the patient leave a suicide note?

Did the patient leave a suicide note?

Had the patient taken pains not to be discovered?

Had the patient taken pains not to be discovered?

Did the patient make the attempt in strange surroundings (i.e. away from home)?

Did the patient make the attempt in strange surroundings (i.e. away from home)?

Would the patient do it again?

Would the patient do it again?

Other relevant factors

Has the precipitant or crisis resolved?

Has the precipitant or crisis resolved?

Is there continuing suicidal intent?

Is there continuing suicidal intent?

Does the patient have any psychiatric symptoms?

Does the patient have any psychiatric symptoms?

What is the patient’s social support system?

What is the patient’s social support system?

Has the patient inflicted self-harm before?

Has the patient inflicted self-harm before?

Has anyone in the family ever taken their life?

Has anyone in the family ever taken their life?

Does the patient have a physical illness?

Does the patient have a physical illness?

Indications for referral to a psychiatrist

Absolute indications include:

Clinical depression

Clinical depression

Psychotic illness of any kind

Psychotic illness of any kind

Clearly preplanned suicidal attempt which was not intended to be discovered

Clearly preplanned suicidal attempt which was not intended to be discovered

Persistent suicidal intent (the more detailed the plans, the more serious the risk)

Persistent suicidal intent (the more detailed the plans, the more serious the risk)

A violent method used

A violent method used

Other common indications include:

Alcohol and drug misuse

Alcohol and drug misuse

Patients over 45 years, especially if male, and young adolescents

Patients over 45 years, especially if male, and young adolescents

Those with a family history of suicide in first-degree relatives

Those with a family history of suicide in first-degree relatives

Those with serious (especially incurable) physical disease

Those with serious (especially incurable) physical disease

Those living alone or otherwise unsupported

Those living alone or otherwise unsupported

Those in whom there is a major unresolved crisis

Those in whom there is a major unresolved crisis

Persistent suicide attempts

Persistent suicide attempts

Any patients who give you cause for concern

Any patients who give you cause for concern

In general, it is worth trying to interview a family member or close friend and check these points with them. Requests for immediate re-prescription on discharge should be denied, except in cases of essential medication. In such cases, however, only 3 days’ supply of medication should be given, and the patient should be requested to report to their general practitioner or to their psychiatric outpatient clinic for further supplies. Occasionally, involuntary admission to hospital may be required (p. 1191).

FURTHER READING

Bruffaerts R, Demyttenaere K, Hwang I et al. Treatment of suicidal people around the world. Br J Psychiatry 2011; 199:64–70.

Moran P et al. The natural history of self-harm from adolescence to young adulthood. Lancet 2012; 379:236–243.

National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health. CG16: Self-harm – The short-term physical and psychological management and secondary prevention of self-harm in primary and secondary care. NCCMH; July 2004.

Anxiety disorders

These are conditions in which anxiety dominates the clinical symptoms. They are classified according to whether the anxiety is persistent (general anxiety) or episodic, with the episodic conditions classified according to whether the episodes are regularly triggered by a cue (phobia) or not (panic disorder). The differential diagnoses of anxiety disorders are given in Table 23.17. A patient with one anxiety disorder may well in time develop others.

Table 23.17 Anxiety disorders: the differential diagnosis

| Psychiatric disorder |

Endocrine disorder |

Depressive illness

Obsessive-compulsive disorder

Presenile dementia

Alcohol dependence

Drug dependence

Benzodiazepine withdrawal

|

Hyperthyroidism

Hypoglycaemia

Phaeochromocytoma

|

General anxiety disorder

This occurs in 4–6% of the population and is more common in women. Symptoms are persistent and often chronic. General anxiety disorder (GAD) and its related panic disorder are differential diagnoses for functional somatic syndromes, owing to the many physical symptoms that are caused by these conditions.

Clinical features

The physical and psychological symptoms are outlined in Table 23.18. The patient looks worried, has a tense posture, restless behaviour and a pale and sweaty skin. The patient takes time to go to sleep, and when asleep wakes intermittently with worry dreams. Associated conditions include the hyperventilation syndrome, which is even more common in panic disorder (Box 23.12). The patient will sigh deeply, particularly when talking about the stresses in their life.

Table 23.18 Physical and psychological symptoms of anxiety

Physical symptoms |

Gastrointestinal |

Genitourinary |

Dry mouth

Difficulty in swallowing

Epigastric discomfort

Aerophagy (swallowing air)

’Diarrhoea’ (usually frequency)

Respiratory |

Increased frequency

Failure of erection

Lack of libido |

Nervous system |

Fatigue

Blurred vision

Dizziness

Sensitivity to noise and/or light

Headache

Sleep disturbance

Trembling |

Feeling of chest constriction

Difficulty in inhaling

Overbreathing

Choking |

Cardiovascular |

Palpitations

Awareness of missed beats

Chest pain |

Psychological symptoms |

Apprehension and fear

Irritability

Difficulty in concentrating

Distractibility |

Restlessness

Depersonalization

Derealization |

Box 23.12

Box 23.12

The hyperventilation syndrome

Features

Panic attacks – fear, terror and impending doom – accompanied by some or all of the following:

dyspnoea (trouble getting a good breath in)

dyspnoea (trouble getting a good breath in)

palpitations

palpitations

chest pain or discomfort

chest pain or discomfort

suffocating sensation

suffocating sensation

dizziness

dizziness

paraesthesiae in hands and feet

paraesthesiae in hands and feet

peri-oral paraesthesiae

peri-oral paraesthesiae

sweating

sweating

carpopedal spasms

carpopedal spasms

Cause

Overbreathing leading to a decrease in PaCO2 and an increase in arterial pH, leading to relative hypocalcaemia.

Diagnosis

A provocation test – voluntary overbreathing for 1 minute – provokes similar symptoms; rebreathing from a large paper bag relieves them.

Management

Explanation and reassurance is given.

Explanation and reassurance is given.

The patient is trained in relaxation techniques and slow controlled breathing.

The patient is trained in relaxation techniques and slow controlled breathing.

The patient is asked to breathe into a closed paper bag.

The patient is asked to breathe into a closed paper bag.

Mixed anxiety and depressive disorder

This disorder is probably the commonest mood disorder in primary care, in which there are equal elements of both anxiety and depression, showing how closely associated these two abnormal mood states are.

Panic disorder

Panic disorder is diagnosed when the patient has repeated sudden attacks of overwhelming anxiety, accompanied by severe physical symptoms, usually related to both hyperventilation (Box 23.12) and sympathetic nervous system activity (palpitations, tremor, restlessness and sweating). The lifetime prevalence is 5%. People with panic disorder often have catastrophic illness beliefs during the panic attack, such as the conviction that they are about to die from a stroke or heart attack. The fear of a stroke is related to dizziness and headache. Fear of a heart attack accompanies chest pain (atypical chest pain). The occasional patient with long-standing attacks may deny feeling anxious and simply report the physical symptoms.

Aetiology

General anxiety and panic disorders occur four or more times as commonly in first-degree relatives of affected patients. Sympathetic nervous system overactivity, increased muscle tension and hyperventilation are the common pathophysiological mechanisms. Anxiety is the emotional response to the threat of a loss, whereas depression is the response to the loss itself. There is some evidence that being bullied, with the explicit threats involved, leads to anxiety disorders in adolescents.

Phobic (anxiety) disorders

Phobias are common conditions in which intense fear is triggered by a stimulus, or group of stimuli, that are predictable and normally cause no particular concern to others (e.g. agoraphobia, claustrophobia, social phobia). This leads to avoidance of the stimulus (Box 23.13). The patient knows that the fear is irrational, but cannot control it. The prevalence of all phobias is 8%, with many patients having more than one. Many phobias of ‘medical’ stimuli exist (e.g. of doctors, dentists, hospitals, vomit, blood and injections) which affect the patient’s ability to receive adequate healthcare.

Box 23.13

Box 23.13

Phobias

A phobia is an abnormal fear and avoidance of an object or situation.

A phobia is an abnormal fear and avoidance of an object or situation.

Phobias are common (8% prevalence), disabling and treatable with behaviour therapy.

Phobias are common (8% prevalence), disabling and treatable with behaviour therapy.

Aetiology

Phobias may be caused by classical conditioning, in which a response (fear and avoidance) becomes conditioned to a previously benign stimulus (a lift), often after an initiating emotional shock (being stuck in a lift). In children, phobias can arise through imagined threats (e.g. stories of ghosts told in the playground). Women have twice the prevalence of phobias than men. Phobias aggregate in families, with increasing evidence of the importance of genetic factors being published.

Agoraphobia

Translated as ‘fear of the market place’, this common phobia (4% prevalence) presents as a fear of being away from home, with avoidance of travelling, walking down a road and supermarkets being common cues. This can be a very disabling condition, since the patient often avoids leaving home, particularly by themselves. It is often associated with claustrophobia, a fear of enclosed spaces.

Social phobia

This is the fear and avoidance of social situations: crowds, strangers, parties and meetings. Public speaking would be the sufferer’s worst nightmare. It is suffered by 2% of the population.

Simple phobias

The commonest is the phobia of spiders (arachnophobia), particularly in women. The prevalence of simple phobias is 7% in the general population. Other common phobias include insects, moths, bats, dogs, snakes, heights, thunderstorms and the dark. Children are particularly phobic about the dark, ghosts and burglars, but the large majority grow out of these fears.

FURTHER READING

Hofmann SG, Smits JA. Cognitive-behavioural therapy for adult anxiety disorders: a meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. J Clin Psychiatry 2008; 69:621–632.

NICE. CG 113: Generalised anxiety disorder and painc disorder (with or without agoraphobia) in adults: Management in primary, secondary and community care. London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence; January 2011.

Tyrer P, Baldwin D. Generalised anxiety disorder. Lancet 2006; 368:2156–2166.

Treatment of anxiety disorders

Psychological treatments

For many people with brief episodes, discussion with a doctor concerning the nature of anxiety is usually sufficient.

Relaxation techniques can be effective in mild/moderate anxiety. Relaxation can be achieved in many ways, including complementary techniques such as meditation and yoga. Conventional relaxation training involves slowing down the rate of breathing, muscle relaxation and mental imagery.

Relaxation techniques can be effective in mild/moderate anxiety. Relaxation can be achieved in many ways, including complementary techniques such as meditation and yoga. Conventional relaxation training involves slowing down the rate of breathing, muscle relaxation and mental imagery.

Anxiety management training involves two stages. In the first stage, verbal cues and mental imagery are used to arouse anxiety to demonstrate the link with symptoms. In the second stage, the patient is trained to reduce this anxiety by relaxation, distraction and reassuring self-statements.

Anxiety management training involves two stages. In the first stage, verbal cues and mental imagery are used to arouse anxiety to demonstrate the link with symptoms. In the second stage, the patient is trained to reduce this anxiety by relaxation, distraction and reassuring self-statements.

Biofeedback is useful for showing patients that they are not relaxed, even when they fail to recognize it, having become so used to anxiety. Biofeedback involves feeding back to the patient a physiological measure that is abnormal in anxiety. These measures may include electrical resistance of the skin of the palm, heart rate, muscle electromyography or breathing pattern.

Biofeedback is useful for showing patients that they are not relaxed, even when they fail to recognize it, having become so used to anxiety. Biofeedback involves feeding back to the patient a physiological measure that is abnormal in anxiety. These measures may include electrical resistance of the skin of the palm, heart rate, muscle electromyography or breathing pattern.

Behaviour therapies are treatments that are intended to change behaviour and thus symptoms. The most common and successful behaviour therapy (with 80% success in some phobias) is graded exposure, otherwise known as systematic desensitization. First, the patient rates the phobia into a hierarchy or ‘ladder’ of worsening fears (e.g. in agoraphobia: walking to the front door with a coat on; walking out into the garden; walking to the end of the road). Second, the patient practises exposure to the least fearful stimulus until no fear is felt. The patient then moves ‘up the ladder’ of fears until they are cured.

Behaviour therapies are treatments that are intended to change behaviour and thus symptoms. The most common and successful behaviour therapy (with 80% success in some phobias) is graded exposure, otherwise known as systematic desensitization. First, the patient rates the phobia into a hierarchy or ‘ladder’ of worsening fears (e.g. in agoraphobia: walking to the front door with a coat on; walking out into the garden; walking to the end of the road). Second, the patient practises exposure to the least fearful stimulus until no fear is felt. The patient then moves ‘up the ladder’ of fears until they are cured.

Cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT) (see p. 1174) is the treatment of choice for panic disorder and general anxiety disorder because the therapist and patient need to identify the mental cues (thoughts and memories) that may subtly provoke exacerbations of anxiety or panic attacks. CBT also allows identification and alteration of the patient’s ‘schema’, or way of looking at themselves and their situation, that feeds anxiety.

Cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT) (see p. 1174) is the treatment of choice for panic disorder and general anxiety disorder because the therapist and patient need to identify the mental cues (thoughts and memories) that may subtly provoke exacerbations of anxiety or panic attacks. CBT also allows identification and alteration of the patient’s ‘schema’, or way of looking at themselves and their situation, that feeds anxiety.

Drug treatments

Initial ‘drug’ treatment should involve advice to gradually cease taking anxiogenic recreational drugs such as caffeine and alcohol (which can cause a rebound anxiety and withdrawal). Prescribed drugs used in the treatment of anxiety can be divided into two groups: those that act primarily on the central nervous system, and those that block peripheral autonomic receptors.

Benzodiazepines are centrally acting anxiolytic drugs. They are agonists of the inhibitory transmitter γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA). Diazepam (5 mg twice daily, up to 10 mg three times daily in severe cases), alprazolam (250–500 µg three times daily) and chlordiazepoxide have relatively long half-lives (20–40 h) and are used as anti-anxiety drugs in the short term. Side-effects include sedation and memory problems, and patients should be advised not to drive while on treatment. They can cause dependence and tolerance within 4–6 weeks, particularly in those with dependent personalities. A withdrawal syndrome (Table 23.19) can occur after just 3 weeks of continuous use and is particularly severe when high doses have been given for a longer time. Thus, if a benzodiazepine drug is prescribed for anxiety, it should be given in as low a dose as possible, preferably on an ‘as necessary’ basis, and for not more than 2–4 weeks. A withdrawal programme from chronic use includes changing the drug to the long-acting diazepam, followed by a very gradual reduction in dosage.

Benzodiazepines are centrally acting anxiolytic drugs. They are agonists of the inhibitory transmitter γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA). Diazepam (5 mg twice daily, up to 10 mg three times daily in severe cases), alprazolam (250–500 µg three times daily) and chlordiazepoxide have relatively long half-lives (20–40 h) and are used as anti-anxiety drugs in the short term. Side-effects include sedation and memory problems, and patients should be advised not to drive while on treatment. They can cause dependence and tolerance within 4–6 weeks, particularly in those with dependent personalities. A withdrawal syndrome (Table 23.19) can occur after just 3 weeks of continuous use and is particularly severe when high doses have been given for a longer time. Thus, if a benzodiazepine drug is prescribed for anxiety, it should be given in as low a dose as possible, preferably on an ‘as necessary’ basis, and for not more than 2–4 weeks. A withdrawal programme from chronic use includes changing the drug to the long-acting diazepam, followed by a very gradual reduction in dosage.

Most SSRIs (e.g. fluoxetine, paroxetine, sertraline, escitalopram, citalopram) are useful symptomatic treatments for general anxiety and panic disorders, as well as some phobias (social phobia), although doses higher than those used in depression are often required. Duloxetine, mirtazapine, venlafaxine and pregabalin are alternative treatments for GAD with the added benefit of possibly preventing the subsequent development of depression. Treatment response is often delayed several weeks; a trial of treatment should last 3 months.

Most SSRIs (e.g. fluoxetine, paroxetine, sertraline, escitalopram, citalopram) are useful symptomatic treatments for general anxiety and panic disorders, as well as some phobias (social phobia), although doses higher than those used in depression are often required. Duloxetine, mirtazapine, venlafaxine and pregabalin are alternative treatments for GAD with the added benefit of possibly preventing the subsequent development of depression. Treatment response is often delayed several weeks; a trial of treatment should last 3 months.

Antipsychotics such as aripiprazole or olanzapine can be effective for more severe or refractory cases.

Antipsychotics such as aripiprazole or olanzapine can be effective for more severe or refractory cases.

Beta-blockers are effective in reducing peripheral symptoms: many of the symptoms of anxiety are due to an increased or sustained release of adrenaline (epinephrine) and noradrenaline (norepinephrine) from the adrenal medulla and sympathetic nerves. Beta-blockers such as propranolol (20–40 mg two or three times daily) are effective in reducing peripheral symptoms such as palpitations, tremor and tachycardia, but they do not help central symptoms such as anxiety.

Beta-blockers are effective in reducing peripheral symptoms: many of the symptoms of anxiety are due to an increased or sustained release of adrenaline (epinephrine) and noradrenaline (norepinephrine) from the adrenal medulla and sympathetic nerves. Beta-blockers such as propranolol (20–40 mg two or three times daily) are effective in reducing peripheral symptoms such as palpitations, tremor and tachycardia, but they do not help central symptoms such as anxiety.

Table 23.19 Withdrawal syndrome with benzodiazepines

Insomnia |

Perceptual distortions |

Anxiety |

Hallucinations (which may be visual) |

Tremulousness |

Hypersensitivities (light, sound, touch) |

Muscle twitchings |

Convulsions |

Acute stress reactions and adjustment disorders

Acute stress reaction

This occurs in individuals in response to exceptional physical and/or psychological stress. While severe, such a reaction usually subsides within days. The stress may be an overwhelming traumatic experience (e.g. accident, battle, physical assault, rape) or a sudden change in the social circumstances of the individual, such as a bereavement. Individual vulnerability and coping capacity play a role in the occurrence and severity of an acute stress reaction, as evidenced by the fact that not all people exposed to exceptional stress develop symptoms. Symptoms usually include an initial state of feeling ‘dazed’ or numb, with inability to comprehend the situation. This may be followed either by further withdrawal from the situation or by anxiety and overactivity. No treatments beyond reassurance and support are normally necessary.

Adjustment disorder

This disorder can follow an acute stress reaction and is common in the general hospital. This is a more prolonged (up to 6 months) emotional reaction to a significant life event, with low mood joining the initial shock and consequent anxiety, but not of sufficient severity or persistence to fulfil a diagnosis of a depressive or anxiety disorder. Supportive counselling is usually a successful treatment, allowing facilitation of unexpressed feelings, elucidation of unspoken fears, and education about the likely future.

Normal grief

Normal grief immediately follows bereavement, is expressed openly, and allows a person to go through the social ceremonies and personal processes of bereavement. The three stages are, first, shock and disbelief, second, the emotional phase (anger, guilt and sadness) and, third, acceptance and resolution. This normal process of adjustment may take up to a year, with movement between all three stages occurring in a sometimes haphazard fashion.

Pathological (abnormal) grief

This is a particular kind of adjustment disorder. It can be characterized as excessive and/or prolonged grief, or even absent grieving with abnormal denial of the bereavement. Usually a relative will be stuck in grief, with insomnia and repeated dreams of the dead person, anger at doctors or even the patient for dying, consequent guilt in equal measure, and an inability to ‘say good-bye’ to the loved person by dealing with their effects. Guided mourning uses cognitive and behavioural techniques to allow the relative to stop grieving and move on in life.

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

This is a protracted response to a stressful event or situation of an exceptionally threatening nature, likely to cause pervasive distress in almost anyone. Causes include natural or human disasters, war, serious accidents, witnessing the violent death of others, being the victim of sexual abuse, rape, torture, terrorism or hostage-taking. Predisposing factors such as personality, previously unresolved traumas, or a history of psychiatric illness may prolong the course of the syndrome. These factors are neither necessary nor sufficient to explain its occurrence, which is most related to the intensity of the trauma, the proximity of the patient to the traumatic event, and how prolonged or repeated it was. Functional brain scan research suggests a possible neurophysiological relationship with obsessive-compulsive disorder (p. 1181).

FURTHER READING

Stein D, Seedat S, Iversen A et al. Post-traumatic stress disorder. Lancet 2006; 369:139–144.

Clinical features

The typical symptoms of PTSD include:

‘Flashbacks’: repeated vivid reliving of the trauma in the form of intrusive memories, often triggered by a reminder of the trauma

‘Flashbacks’: repeated vivid reliving of the trauma in the form of intrusive memories, often triggered by a reminder of the trauma

Insomnia, usually accompanied by nightmares, the nocturnal equivalent of flashbacks

Insomnia, usually accompanied by nightmares, the nocturnal equivalent of flashbacks

Emotional blunting, emptiness or ‘numbness’, alternating with

Emotional blunting, emptiness or ‘numbness’, alternating with

–

intense anxiety with exposure to events that resemble an aspect of the traumatic event, including anniversaries of the trauma

Avoidance of activities and situations reminiscent of the trauma

Avoidance of activities and situations reminiscent of the trauma

Emotional detachment from other people

Emotional detachment from other people

Hypervigilance with autonomic hyperarousal and an enhanced startle reaction.

Hypervigilance with autonomic hyperarousal and an enhanced startle reaction.

This clinical picture represents the severe end of a spectrum of emotional reactions to trauma, which might alternatively take the form of an adjustment or mood disorder. The course is often fluctuating but recovery can be expected in two-thirds of cases at the end of the first year. Complications include depressive illness and alcohol misuse. In a small proportion of cases the condition may show a chronic course over many years and a transition to an enduring personality change.

Treatment and prevention

Compulsory psychological debriefing immediately after a trauma does not prevent PTSD and may be harmful. Prevention is better achieved by the support offered by others who were also involved. Trauma focused CBT is often effective. Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) is equally effective treatment and may require fewer sessions. SSRIs and venlafaxine have a place in the management of chronic PTSD, but drop-out from pharmacotherapy is common.

The adult consequences of childhood sexual and physical abuse

Estimates of the prevalence of childhood sexual abuse vary depending on definition but there is reasonable evidence that 20% of women and 10% of men suffered significant, coercive and inappropriate sexual activity in childhood. The abuser is usually a member of the family or known to the child. The likelihood of long-term consequences is determined by:

an earlier age of onset

an earlier age of onset

the severity of the abuse

the severity of the abuse

the repeated nature and duration of the period of abuse

the repeated nature and duration of the period of abuse

the association with physical abuse.

the association with physical abuse.

Consequent adult psychiatric disorders include depressive illness, substance misuse, eating disorders, borderline personality disorder and deliberate self-harm. Other negative outcomes include a decline in socioeconomic status, sexual problems, prostitution and difficulties in forming adult relationships.

Repeated childhood physical and emotional abuse or neglect may also affect emotional and personality development, predisposing the adult to similar psychiatric disorders. Those with repeated abuse are more likely to have long-term physical stress related consequences, such as hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis downregulation and smaller brain hippocampal sizes.

Psychodynamic psychotherapy

Psychodynamic psychotherapy is derived from psychoanalysis and is based on a number of key analytical concepts. These include Freud’s ideas about psychosexual development, defence mechanisms, free association as the method of recall, and the therapeutic techniques of interpretation, including that of transference, defences and dreams. Such therapy usually involves once-weekly sessions, the length of treatment varying between 3 months and 2 years. The long-term aim of such therapy is twofold: symptom relief and personality change. Psychodynamic psychotherapy is classically indicated in the treatment of unresolved conflicts in early life, as might be found in non-psychotic and personality disorders, but there is no convincing evidence concerning its superiority over alternative forms of treatment.

Cognitive analytical therapy

Cognitive analytical therapy is an integration of cognitive behaviour therapy and psychodynamic therapy. It is a short-term therapy that involves the patient and therapist recognizing the origins of a recurrent problem, reformulating how it continues to occur, and revising other ways of coping and internalizing it, using both the transference of the patient–therapist relationship and behavioural experiments.

Obsessive-compulsive disorder

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) is characterized by obsessional ruminations and compulsive rituals. It is particularly associated with and/or secondary to both depressive illness and Gilles de la Tourette’s syndrome (p. 1122). The prevalence is between 1% and 2% in the general population, and patients often do not seek help. There is an equal distribution by gender, and the mean age of onset ranges from 20 to 40 years.

FURTHER READING

Abramowitz JS, Taylor S, McKay D. Obsessive-compulsive disorder. Lancet 2009; 374:491–499.

Storch EA, Murphy TK, Goodman WK et al. A preliminary study of D-cycloserine augmentation of cognitive-behavioral therapy in pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder. Biol Psychiatry 2010; 68:1073–1076.

Clinical features

The obsessions and compulsions are time consuming and intrusive so that they affect functioning and cause considerable distress. Ruminations are often unpleasant repetitive thoughts, out of character, such as being dirty or violent. This can lead to a constant need to check that everything and everyone is alright and that things have been done correctly, and reassurance cannot remove the doubt that persists. Some rituals are derived from superstitions, such as actions repeated a fixed number of times, with the need to start again if interrupted. When severe and primary, OCD can last for many years and may be resistant to treatment. However, obsessional symptoms commonly occur in other disorders, most notably depressive illness and schizophrenia, and remit with the resolution of the primary disorder.

Minor degrees of obsessional symptoms and compulsive rituals or superstitions are common in people who are not ill or in need of treatment, particularly in times of stress. The mildest grade is that of obsessional personality traits such as over-conscientiousness, tidiness, punctuality and other attitudes and behaviours indicating a strong tendency towards conformity and inflexibility. Such individuals are perfectionists who are intolerant of shortcomings in themselves and others, and take pride in their high standards. When such traits are so marked that they dominate other aspects of the personality, in the absence of clear-cut OCD, the diagnosis is obsessional (anankastic) personality (see p. 1190).

Aetiology

Genetic

OCD is found in 5–7% of the first-degree relatives. Twin studies showed 80–90% concordance in monozygotic twins and about 50% in dizygotic twins. Genetic factors account for more of the variance in childhood onset cases than in those who develop it as an adult.

Biological model

Neuroimaging studies suggest dysfunction in the orbito-striatal area (including the caudate nucleus) and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex combined with abnormalities in serotonergic (underactive) and glutamatergic (overactive) neurotransmission. Further support for this model comes from an association with a number of neurological disorders involving dysfunction of the striatum, including Parkinson’s disease, Huntington’s and Sydenham’s chorea. The latter has also been associated with OCD and tic disorders in the paediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorder associated with streptococcal infection (PANDAS). This is a rare condition in children following group A haemolytic streptococcal infection. OCD also can follow head trauma.

Cognitive-behavioural model

Most people have the occasional intrusive thoughts, but would ordinarily dismiss these as meaningless and not focus upon them further. These develop into an obsession when they assume great significance to the individual, causing greater anxiety. This anxiety motivates suppression of these thoughts and ritual behaviours are developed to further reduce anxiety.

Treatment

Psychological treatments

Cognitive behavioural therapy focusing on exposure and response prevention is reasonably effective. This involves confronting the anxiety provoking stimulus in a controlled environment and not performing the associated ritual. The aim is for the individual to habituate to the stimulus, thus reducing anxiety. Since it provokes anxiety, the drop-out rate is often high.

Physical treatment

Tricyclic antidepressants and serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Clomipramine (a tricyclic) and the SSRIs are the mainstay of drug treatment. Their efficacy is independent of their antidepressant action but the doses required are usually some 50–100% higher than those effective in depression. Although many sufferers respond, relapse rates on discontinuation are high. Three months’ treatment with maximum tolerated doses may be necessary for a positive response and in those who fail to respond, the addition of an antipsychotic significantly improves outcome, especially when tics occur co-morbidly. Positive correlations between reduced severity of OCD and decreased orbitofrontal and caudate metabolism following behavioural and SSRI treatments have been demonstrated in a number of studies.

Anti-glutamatergic agents. Recent studies have suggested that riluzole may be effective. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled augmentation trial of D-cycloserine (an N-methyl-D-aspartic acid (NMDA) receptor agonist) administered in combination with CBT, prior to sessions, has suggested that this may speed treatment response time.

Deep brain stimulation. This is a non-ablative, and therefore potentially reversible, surgical technique that involves the electrical stimulation of the basal ganglia by implanted electrodes, creating a ‘functional lesion’. Although this has had success, often impressively so in intractable cases, issues still remain regarding subject selection and the optimum anatomical targets.

Psychosurgery. This is very occasionally recommended in cases of chronic and severe OCD that has not responded to other treatments. The development of stereotactic techniques has led to the replacement of the earlier, crude leucotomies with more precise surgical interventions such as subcaudate tractotomy and cingulotomy, with small yttrium radioactive implants, which induce lesions in the cingulate area or the ventromedial quadrant of the frontal lobe.

Prognosis

Two-thirds of cases improve within a year. The remainder run a fluctuating or persistent course. The prognosis is worse when the personality is obsessional or anankastic and the OCD is primary and severe.

Alcohol misuse and dependence

A wide range of physical, social and psychiatric problems are associated with excessive drinking. Alcohol misuse occurs when a patient is drinking in a way that regularly causes problems to the patient or others.

The problem drinker is one who causes or experiences physical, psychological and/or social harm as a consequence of drinking alcohol. Many problem drinkers, while heavy drinkers, are not physically addicted to alcohol.

The problem drinker is one who causes or experiences physical, psychological and/or social harm as a consequence of drinking alcohol. Many problem drinkers, while heavy drinkers, are not physically addicted to alcohol.

Heavy drinkers are those who drink significantly more in terms of quantity and/or frequency than is safe to do in the long term.

Heavy drinkers are those who drink significantly more in terms of quantity and/or frequency than is safe to do in the long term.

Binge drinkers are those who drink excessively in short bouts, usually 24–48 h long, separated by often quite lengthy periods of abstinence. Their overall monthly or weekly alcohol intake may be relatively modest.

Binge drinkers are those who drink excessively in short bouts, usually 24–48 h long, separated by often quite lengthy periods of abstinence. Their overall monthly or weekly alcohol intake may be relatively modest.

Alcohol dependence is defined by a physical dependence on or addiction to alcohol. The term ‘alcoholism’ is a confusing one with off-putting connotations of vagrancy, ‘meths’ drinking and social disintegration. It has been replaced by the term ‘alcohol dependence syndrome’.

Alcohol dependence is defined by a physical dependence on or addiction to alcohol. The term ‘alcoholism’ is a confusing one with off-putting connotations of vagrancy, ‘meths’ drinking and social disintegration. It has been replaced by the term ‘alcohol dependence syndrome’.

Epidemiology of alcohol misuse

A total of 20% of men and 10% of women drink more than double the recommended limits of 3 units a day of alcohol for men, and 2 units for women in the UK. The amount of alcohol consumed in the UK has doubled over the last 50 years. Some 4% of men and 2% of women report alcohol withdrawal symptoms, suggesting dependence. Approximately one in five male admissions to acute medical wards is directly or indirectly due to alcohol. People with serious drinking problems have a two to three times increased risk of dying compared with members of the general population of the same age and sex.

Table 23.20 provides an approximate estimate of what can be expected in an average individual in the way of behavioural impairment resulting from a particular blood alcohol level. The amount of alcohol is measured for convenience in units which contain about 8 g of absolute alcohol and raises the blood alcohol concentration by about 15–20 mg/dL, the amount that is metabolized in 1 h. One unit of alcohol is found in half a pint of ordinary beer (3.5% alcohol by volume, ABV) and 125 mL of 9% wine. However, some beer and most lager is now 5% ABV; 3 units per pint. Wine is often 13% ABV and sold in 175 mL glasses; 2–3 units per glass.

Table 23.20 Behavioural effects of alcohol

| Blood alcohol concentration (BAC) (mg/dL) |

Expected effect |

20–99 |

Impaired coordination, euphoria |

100–199 |

Ataxia, poor judgement, labile mood |

200–299 |

Marked ataxia and slurred speech; poor judgement, labile mood, nausea and vomiting |

300–399 |

Stage 1 anaesthesia, memory lapse, labile mood |

400+ |

Respiratory failure, coma, death |

Detection

Alcohol misuse should be suspected in any patient presenting with one or more physical problems commonly associated with excessive drinking (see p. 226). Alcohol misuse may also be associated with a number of psychiatric symptoms/disorders and social problems (Table 23.21).

Table 23.21 Common alcohol-related psychological and social problems

| Psychological |

Social |

Depression

Anxiety

Memory problems

Delirium tremens

Attempted suicide

Suicide

Pathological jealousy

|

Domestic violence

Marital and sexual difficulties

Child abuse

Employment problems

Financial difficulties

Accidents at home, on the roads, at work

Delinquency and crime

Homelessness

|

Guidelines

The patient’s frequency of drinking and quantity drunk during a typical week should be established:

Up to 21 units of alcohol a week for men and 14 units for women: this carries no long-term health risk

Up to 21 units of alcohol a week for men and 14 units for women: this carries no long-term health risk

21–35 units a week for men and 14–24 units for women: there is unlikely to be any long-term health damage, provided the drinking is spread throughout the week

21–35 units a week for men and 14–24 units for women: there is unlikely to be any long-term health damage, provided the drinking is spread throughout the week

Over 36 units a week for men and 24 for women: damage to health becomes increasingly likely

Over 36 units a week for men and 24 for women: damage to health becomes increasingly likely

Above 50 units a week for men and 35 for women: this is a definite health hazard.

Above 50 units a week for men and 35 for women: this is a definite health hazard.

Diagnostic markers of alcohol misuse

Laboratory parameters indicating alcohol misuse in recent weeks include elevated γ-glutamyl transpeptidase (γ-GT) and mean corpuscular volume (MCV). Blood or breath alcohol tests are useful in anyone suspected of very recent drinking.

Alcohol dependence syndrome

Dependence is a pattern of repeated self-administration that causes tolerance, withdrawal and compulsive drug-taking, the essential element of which is the continued use of the substance despite significant substance-related problems. Symptoms of alcohol dependence in a typical order of occurrence are shown in Table 23.22. Diagnostic criteria for alcohol withdrawal syndrome are shown in Table 23.23.

Table 23.22 Symptoms of alcohol dependence

Unable to keep to a drink limit

Difficulty in avoiding getting drunk

Spending a considerable time drinking

Missing meals

Memory lapses, blackouts

Restless without drink

Organizing day around drink

Trembling after drinking the day before

Morning retching and vomiting

Sweating excessively at night

Withdrawal fits

Morning drinking

Increased tolerance

Hallucinations, frank delirium tremens

|

Table 23.23 Diagnostic criteria for alcohol withdrawal syndrome

Any three of the following: |

Tremor of outstretched hands, tongue or eyelids

Sweating

Nausea, retching or vomiting

Tachycardia or hypertension

Anxiety

Psychomotor agitation

Headache

Insomnia

Malaise or weakness

Transient visual, tactile or auditory hallucinations or illusions

Grand mal convulsions

|

The course of the alcohol dependence syndrome

About 25% of all cases of alcohol misuse will lead to chronic alcohol dependence. This most commonly ends in social incapacity, death or abstinence. Alcohol dependence syndrome usually develops after 10 years of heavy drinking (3–4 years in women). In some individuals who use alcohol to alter consciousness, obliterate conscience and defy social mores, dependence and loss of control may appear in only a few months or years.

Delirium tremens (DTs)

Delirium tremens is the most serious withdrawal state and occurs 1–3 days after alcohol cessation, so is commonly seen 1–2 days after admission to hospital. Patients are disorientated, agitated, and have a marked tremor and visual hallucinations (e.g. insects or small animals coming menacingly towards them). Signs include sweating, tachycardia, tachypnoea and pyrexia. Complications include dehydration, infection, hepatic disease or the Wernicke–Korsakoff syndrome (p. 1147).

Causes of alcohol dependence

Genetic factors. Sons of alcohol-dependent people who are adopted by other families are four times more likely to develop drinking problems than are the adopted sons of non-alcohol misusers. Genetic markers include dopamine-2 receptor allele A1, alcohol dehydrogenase subtypes and monoamine oxidase B activity, but they are not specific.

Environmental factors. One in 10 boys who grow up in a household where neither parent misused alcohol subsequently become alcohol dependent, compared with one in four of those reared by alcohol-misusing fathers and one in three of those reared by alcohol-misusing mothers.

Biochemical factors. Several factors have been suggested, including abnormalities in alcohol dehydrogenase, neurotransmitter substances and brain amino acids, such as GABA. There is no conclusive evidence that these or other biochemical factors play a causal role.

Psychiatric illness. This is an uncommon cause of addictive drinking but it is a treatable one. Some depressed patients drink excessively in the hope of raising their mood. People with anxiety states or phobias are also at risk.

Excess consumption in society. The prevalence of alcohol dependence and problems correlates with the general level (per capita consumption) of alcohol use in a society. This, in turn, is determined by factors that may control overall consumption – including price, licensing laws, availability, and the societal norms concerning the use and misuse of alcohol.

Treatment

Psychological treatment of problem drinking

Successful identification at an early stage can be a helpful intervention in its own right. It should lead to:

The provision of information concerning safe drinking levels

The provision of information concerning safe drinking levels

A recommendation to cut down where indicated

A recommendation to cut down where indicated

Simple support and advice concerning associated problems.

Simple support and advice concerning associated problems.

Such a brief intervention is effective in its own right. Successful alcohol misuse treatment involves motivational enhancement (motivational therapy), feedback, education about adverse effects of alcohol, and agreeing drinking goals. A motivational approach is based on five stages of change: precontemplation, contemplation, determination, action and maintenance. The therapist uses motivational interviewing and reflective listening to allow the patient to persuade himself along the five stages to change.

This technique, cognitive behaviour therapy and 12-step facilitation (as used by Alcoholics Anonymous, AA) have all been shown to reduce harmful drinking. With addictive drinking, self-help group therapy, which involves the long-term support by fellow members of the group (e.g. AA), is helpful in maintaining abstinence. Family and marital therapy involving both the alcohol misuser and spouse may also be helpful. Families of drinkers find meeting others in a similar situation helpful (Al-Anon).

Drug treatments of problem drinking

Alcohol withdrawal and DTs

Addicted drinkers often experience considerable difficulty when they attempt to reduce or stop their drinking. Withdrawal symptoms are a particular problem and delirium tremens needs urgent treatment (Box 23.14). In the absence of DTs, alcohol withdrawal can be treated on an outpatient basis, using one of the fixed schedules in Box 23.14, so long as the patient attends daily for medication and monitoring, and has good social support. Outpatient schedules are sometimes given over 5 days. Long-term treatment with benzodiazepines should not be prescribed in those patients who continue to misuse alcohol. Some alcohol misusers add dependence on diazepam or clomethiazole to their problems.

Box 23.14

Box 23.14

Management of delirium tremens (DTs)

General measures

Admit the patient to a medical bed.

Admit the patient to a medical bed.

Correct electrolyte abnormalities and dehydration.

Correct electrolyte abnormalities and dehydration.

Treat any co-morbid disorder (e.g. infection).

Treat any co-morbid disorder (e.g. infection).

Give parenteral thiamine slowly (250 mg daily for 3–5 days in the absence of Wernicke–Korsakoff, W–K syndrome).

Give parenteral thiamine slowly (250 mg daily for 3–5 days in the absence of Wernicke–Korsakoff, W–K syndrome).

Give parenteral thiamine slowly (500 mg daily for 3–5 days with W–K encephalopathy. Note: beware anaphylaxis).

Give parenteral thiamine slowly (500 mg daily for 3–5 days with W–K encephalopathy. Note: beware anaphylaxis).

Give prophylactic phenytoin or carbamazepine, if previous history of withdrawal fits.

Give prophylactic phenytoin or carbamazepine, if previous history of withdrawal fits.

Specific drug treatment

Give one of the following orally:

Diazepam 10–20 mg

Diazepam 10–20 mg

Chlordiazepoxide 30–60 mg

Chlordiazepoxide 30–60 mg

Repeat 1 h after last dose depending on response.

Fixed-schedule regimens

Diazepam 10 mg every 6 h for 4 doses, then 5 mg 6-hourly for 8 doses OR

Diazepam 10 mg every 6 h for 4 doses, then 5 mg 6-hourly for 8 doses OR

Chlordiazepoxide 30 mg every 6 h for 4 doses, then 15 mg 6-hourly for 8 doses.

Chlordiazepoxide 30 mg every 6 h for 4 doses, then 15 mg 6-hourly for 8 doses.

Provide additional benzodiazepine when symptoms and signs are not controlled.

Drugs for prevention of alcohol dependence

Naltrexone, the opioid antagonist (50 mg per day), reduces the risk of relapse into heavy drinking and the frequency of drinking. Acamprosate (1–2 g/day) acts on several receptors including those for GABA, noradrenaline (norepinephrine) and serotonin. There is reasonable evidence that it reduces drinking frequency. Neither drug seems particularly helpful in maintaining abstinence. Both drug effects are enhanced by combining them with counseling, but their moderate efficacy precludes regular use.

Drugs such as disulfiram react with alcohol to cause unpleasant acetaldehyde intoxication and histamine release. A daily maintenance dose means that the patient must wait until the disulfiram is eliminated from the body before drinking safely. There is mixed evidence of efficacy.

Oral thiamine (300 mg/day) can prevent Wernicke–Korsakoff syndrome (p. 1147) in heavy drinkers.

Outcome

Research suggests that 30–50% of alcohol-dependent drinkers are abstinent or drinking very much less up to 2 years following traditional intervention. It is too early to be certain of the long-term outcome of patients treated with the latest psychological and pharmacological therapies.

FURTHER READING

Anton RF. Naltrexone for the management of alcohol dependence. N Engl J Med 2008; 359:715–721.

Moss M, Burnham EL. Alcohol abuse in the critically ill patient. Lancet 2006; 368:2231–2242.

Series – Drug use and dependence. Lancet 2012; 379:55–70; 71–83, 84–91.

Drug misuse and dependence

In addition to alcohol and nicotine, there are a number of psychotropic substances that are taken for their effects on mood and other mental functions (Table 23.24).

Table 23.24 Commonly used drugs of misuse and dependence

Stimulants |

Methylphenidate |

|

Phenmetrazine |

|

Phencyclidine (‘angel dust’) |

|

Cocaine |

|

Amfetamine derivates |

|

Ecstasy (MDMA) |

Hallucinogens |

Cannabis preparations |

|

Solvents |

|

Lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) |

|

Mescaline |

Narcotics |

Morphine |

|

Heroin |

|

Codeine |

|

Pethidine |

|

Methadone |

Tranquillizers |

Barbiturates |

|

Benzodiazepines |

Causes of drug misuse

There is no single cause of drug misuse and/or dependence. Three factors appear commonly, in a similar way to alcohol problems:

The availability of drugs

The availability of drugs

A vulnerable personality

A vulnerable personality

Social pressures, particularly from peers.

Social pressures, particularly from peers.

Once regular drug-taking is established, pharmacological factors determine dependence.

Solvents

Of the adolescents in the UK, 1% sniff solvents for their intoxicating effects. Tolerance develops over weeks or months. Intoxication is characterized by euphoria, excitement, a floating sensation, dizziness, slurred speech and ataxia. Acute intoxication can cause amnesia and visual hallucinations. In 2004, there were 47 deaths recorded in the UK from solvent misuse; 13 of these were among under 18-year-olds.

Amfetamines and related substances

These have temporary stimulant and euphoriant effects that are followed by fatigue and depression, with the latter sometimes prolonged for weeks. Psychological rather than true physical dependence occurs with amfetamine sulphate (’speed’). Methyl amfetamine, also known as ‘methamfetamine’ or ‘crystal meth’, is another amfetamine psychostimulant. The particularly high potential for abuse is associated with the activation of neural reward mechanisms involving nucleus accumbens dopamine release.

In addition to a manic-like presentation, amfetamines can produce a paranoid psychosis indistinguishable from schizophrenia.

‘Ecstasy’ (also known as: E, white burger, white dove), is the street name for 3,4-methylenedioxy-methamfetamine (MDMA), a psychoactive phenylisopropylamine, synthesized as an amfetamine derivative. It is a psychedelic drug, which is often used as a ‘dance drug’. It has a brief duration of action (4–6 h). Deaths have been reported from malignant hyperpyrexia and dehydration. Acute renal and liver failure can occur.

Cocaine (p. 917)

Cocaine is a central nervous system stimulant (with similar effects to amfetamines) derived from Erythroxylon coca trees grown in the Andes. In purified form it may be taken by mouth, snorted or injected. If cocaine hydrochloride is converted to its base (‘crack’), it can be smoked. This causes an intense stimulating effect, and ‘free-basing’ is common. Compulsive use and dependence occur more frequently among users who are free-basing. Dependent users take large doses and alternate between withdrawal phenomena of depression, tremor and muscle pains, and the hyperarousal produced by increasing doses. Prolonged use of high doses produces irritability, restlessness, paranoid ideation and occasionally convulsions. Persistent sniffing of the drug can cause perforation of the nasal septum. Overdoses cause death through myocardial infarction, cerebrovascular disease, hyperthermia and arrhythmias (p. 917).

Hallucinogenic drugs

Hallucinogenic drugs, such as lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) and mescaline, produce distortions and intensifications of sensory perceptions, as well as frank hallucinations in acute intoxication. Psychosis is a long-term complication.

Cannabis

Cannabis (also known as: grass, pot, skunk, spliff, marijuana) is a drug widely used in some subcultures. It is derived from the dried leaves and flowers of the plant Cannabis sativa. It can cause tolerance and dependence. Hashish is the dried resin from the flower tops, whilst marijuana refers to any part of the plant. The drug, when smoked, seems to exaggerate the pre-existing mood, be it depression, euphoria or anxiety. It has specific analgesic properties. Cannabis use has increased in the UK recently, especially use of more potent ‘skunk’. An amotivational syndrome with apathy and memory problems has been reported with chronic daily use. Cannabis may of itself sometimes cause psychosis in the right circumstances (see below).

Tranquillizers

Drugs causing dependence include barbiturates and benzodiazepines. Benzodiazepine dependence is common and may be iatrogenic, when the drugs are prescribed and not discontinued. Discontinuing treatment with benzodiazepines may cause withdrawal symptoms (Table 23.19). For this reason, withdrawal should be supervised and gradual.

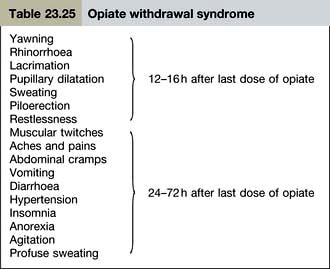

Opiates

Physical dependence occurs with morphine, heroin and codeine as well as with synthetic and semisynthetic opiates such as methadone, pethidine and fentanyl. These substances display cross-tolerance – the withdrawal effects of one are reduced by administration of another. The psychological effects of opiates are a calm, slightly euphoric mood associated with freedom from physical discomfort and a flattening of emotional response. This is believed to be due to the attachment of morphine and its analogues to endorphin receptors in the CNS. Tolerance to this group of drugs is rapidly developed and marked, but is rapidly lost following abstinence. The opiate withdrawal syndrome consists of a constellation of signs and symptoms (Table 23.25) that reaches peak intensity on the 2nd or 3rd day after the last dose of the opiate. These rapidly subside over the next 7 days. Withdrawal is dangerous in people with heart disease or other chronic debilitating conditions.

Opiate addicts have a relatively high mortality rate, owing to both the ease of accidental overdose and the blood-borne infections associated with shared needles. Heart disease (including infective endocarditis), tuberculosis and AIDS are common causes of death, while the complications of hepatitis B and C are also common.

Treatment of chronic misuse

Blood and urine screening for drugs is required in circumstances where drug misuse is suspected (Table 23.24). When a patient with an opiate addiction is admitted to hospital for another health problem, advice should be sought from a psychiatrist or drug misuse clinic regarding management of their addiction while an inpatient.

The treatment of chronic dependence is directed towards helping the patient either to live without drugs or to prevent secondary ill-health. Patients need help and advice in order to avoid a withdrawal syndrome. Some people with opiate addiction who cannot manage abstinence may be maintained on oral methadone. In the UK, only specially licensed doctors may legally prescribe heroin and cocaine to an addict for maintenance treatment of addiction. An overdose should be treated immediately with the opioid antagonist naloxone. Recently, injectable diacetylmorphine, the active ingredient in heroin, has been proposed as a more effective alternative to methadone but adverse effects (accidental overdose and seizures) remain a potential concern.

Drug-induced psychosis

Drug-induced psychosis has been reported with amfetamine and its derivatives, and cocaine and hallucinogens. It can occur acutely after drug use, but is more usually associated with chronic misuse. Psychoses are characterized by vivid hallucinations (usually auditory, but often in more than one sensory modality), misidentifications, delusions and/or ideas of reference (often of a persecutory nature), psychomotor disturbances (excitement or stupor) and an abnormal affect. ICD-10 requires that the condition occurs within 2 weeks and usually within 48 h of drug use and that it should persist for more than 48 h but not more than 6 months.

Cannabis use can result in anxiety, depression or hallucinations. Manic-like psychoses occurring after long-term cannabis use have been described, but seem more likely to be related to the toxic effects of heavy ingestion. However, a meta-analysis suggests that ever taking cannabis increases the risk of psychosis by 40%, daily cannabis use doubles the risk of psychosis, and that 14% of schizophrenia in the UK would be prevented if cannabis use ceased. The risk is higher in people taking cannabis early in their lives and with a heavy consumption.

FURTHER READING

Kuepper R, van Os J, Lieb R et al. Continued cannabis use and risk of incidence and persistence of psychotic symptoms: 10 year follow-up cohort study. BMJ 2011; 342:d738.

Oviedo-Joekes E, Brissette S, Marsh DC et al. Diacetylmorphine versus methadone for the treatment of opioid addiction. N Engl J Med 2009; 361:777–786.

Schizophrenia

The group of illnesses conventionally referred to as ‘schizophrenia’ is diverse in nature and covers a broad range of perceptual, cognitive and behavioural disturbances. The point prevalence of the condition is 0.5% throughout the world, with equal gender distribution. A physician primarily needs to know how to recognize schizophrenia, what problems it might present with in the general hospital, and how it is treated.

Causes

No single cause has been identified. Schizophrenia is likely to be a disease of neurodevelopmental disconnection caused by an interaction of genetic and multiple environmental factors that affect brain development. It is likely that daily cannabis use is a risk factor. The genetic aetiology is likely to be polygenic and non-mendelian. Schizophrenia has a heritability of about 60%. Functional neuroimaging studies and histology point towards alterations in prefrontal and less consistently temporal lobe function, with enlarged lateral ventricles and disorganized cytoarchitecture in the hippocampus, supporting the neurodevelopmental theory of aetiology. Dopamine excess (D2) is the oldest and most widely accepted neurochemical hypothesis, although this may only explain one group of symptoms (the positive ones). The cognitive impairments in schizophrenia may be related to dopamine D1 abnormalities. The interaction between serotonergic and dopaminergic systems is likely to play a role, although direct evidence is currently lacking. Additional hypotheses involving glutamate (NMDA) and GABA systems are currently also under scrutiny.

Clinical features

The illness can begin at any age but is rare before puberty. The peak age of onset is the early 20s. The symptoms that are diagnostic of the condition have been termed first rank symptoms and were described by the German psychiatrist Kurt Schneider. They consist of:

Auditory hallucinations in the third person, and/or voices commenting on their behaviour

Auditory hallucinations in the third person, and/or voices commenting on their behaviour

Thought withdrawal, insertion and broadcast

Thought withdrawal, insertion and broadcast

Primary delusion (arising out of nothing)

Primary delusion (arising out of nothing)

Delusional perception

Delusional perception

Somatic passivity and feelings – patients believe that thoughts, feelings or acts are controlled by others.

Somatic passivity and feelings – patients believe that thoughts, feelings or acts are controlled by others.

The more of these symptoms a patient has, the more likely the diagnosis is schizophrenia, but these symptoms may also occur in other psychoses. Other symptoms of acute schizophrenia include behavioural disturbances, other hallucinations, secondary (usually persecutory) delusions and blunting of mood. Schizophrenia is sometimes divided into ‘positive’ (type 1) and ‘negative’ (type 2) types:

Positive schizophrenia is characterized by acute onset, prominent delusions and hallucinations, normal brain structure, a biochemical disorder involving dopaminergic transmission, a good response to neuroleptics, and a better outcome.

Negative schizophrenia is characterized by a slow, insidious onset, a relative absence of acute symptoms, the presence of apathy, social withdrawal, lack of motivation, underlying brain structure abnormalities and poor neuroleptic response.

Chronic schizophrenia

This is characterized by long duration and ‘negative’ symptoms of underactivity, lack of drive, social withdrawal and emotional emptiness.

Differential diagnosis

Schizophrenia should be distinguished from:

Organic mental disorders (e.g. partial complex epilepsy)

Organic mental disorders (e.g. partial complex epilepsy)

Mood (affective) disorders (e.g. mania)

Mood (affective) disorders (e.g. mania)

Drug psychoses (e.g. amfetamine psychosis)

Drug psychoses (e.g. amfetamine psychosis)

Personality disorders (schizotypal).

Personality disorders (schizotypal).

In older patients, any acute or chronic brain syndrome can present in a schizophrenia-like manner. A helpful diagnostic point is that altered consciousness and disturbances of memory do not occur in schizophrenia, and visual hallucinations are unusual.

A schizoaffective psychosis describes a clinical presentation in which clear-cut affective and schizophrenic symptoms co-exist in the same episode.

Prognosis

The prognosis of schizophrenia is variable: 15–25% of people with schizophrenia recover completely, about 70% will have relapses and may develop mild to moderate negative symptoms, and about 10% will remain seriously disabled.

Treatment

The best results are obtained by combining drug and social treatments.

Antipsychotic (neuroleptic) drugs

These act by blocking the D1 and D2 groups of dopamine receptors. Such drugs are most effective against acute, positive symptoms and are least effective in the management of chronic, negative symptoms. Complete control of positive symptoms can take up to 3 months, and premature discontinuation of treatment can result in relapse.

As antipsychotic drugs block both D1 and D2 dopamine receptors, they usually produce extrapyramidal side-effects. This limits their use in maintenance therapy of many patients. They also block adrenergic and muscarinic receptors and thereby cause a number of unwanted effects (Table 23.26).

Table 23.26 Unwanted effects of antipsychotic drugs

| Common effects |

Rare effects |

Motor |

Hypersensitivity

Cholestatic jaundice

Leucopenia

Skin reactions |

Acute dystonia Parkinsonism

Akathisia (motor restlessness)

Tardive dyskinesia |

Autonomic |

Others |

Hypotension

Failure of ejaculation |

Precipitation of glaucoma

Galactorrhoea (due to hyperprolactinaemia)

Amenorrhoea

Cardiac arrhythmias

Seizures |

Antimuscarinic |

Dry mouth

Urinary retention

Constipation

Blurred vision |

Metabolic |

Weight gain |

The neuroleptic malignant syndrome is an infrequent but potentially dangerous unwanted effect. This is a medical emergency and should be managed on a medical ward. It occurs in 0.2% of patients on neuroleptic drugs, particularly the potent dopaminergic antagonists, e.g. haloperidol. Symptoms occur a few days to a few weeks after starting treatment and consist of hyperthermia, muscle rigidity, autonomic instability (tachycardia, labile blood pressure, pallor) and a fluctuating level of consciousness. Investigations show a raised creatine kinase, raised white cell count and abnormal liver biochemistry. The more severe consequences include renal failure, pulmonary embolus and death. Treatment consists of stopping the drug and general resuscitation, e.g. temperature reduction. Bromocriptine enhances dopaminergic activity and dantrolene will reduce muscle tone but no treatment has proven benefit.

Pregnancy. Data on the potential teratogenicity of antipsychotic (neuroleptic) medications are still limited. The disadvantages of not treating during pregnancy have to be balanced against possible developmental risks to the fetus. The butyrophenones (e.g. haloperidol) are probably safer than the phenothiazines. Subsequent management decisions on dosage will depend primarily on the ability to avoid side-effects, since the antiparkinsonian agents are still believed to be teratogenic and should be avoided.

Typical or first generation antipsychotics

Phenothiazines were the first group of antipsychotics to be developed but are used less frequently now. Chlorpromazine (100–1000 mg daily) is the drug of choice when a more sedating drug is required. Trifluoperazine is used when sedation is undesirable. Fluphenazine decanoate is used as a long-term prophylactic to prevent relapse, as a depot injection (25–100 mg i.m. every 1–4 weeks).

Butyrophenones (e.g. haloperidol 2–30 mg daily) are also powerful antipsychotics, used in the treatment of acute schizophrenia and mania. They are likely to cause a dystonia and/or extrapyramidal side-effects, but are much less sedating than the phenothiazines.

Atypical antipsychotics or serotonin dopamine antagonists (SDAs)

These drugs, also referred to as the ‘second generation antipsychotics’, are ‘atypical’ in that they block D2 receptors less than D1 and thus cause fewer extrapyramidal side-effects and less tardive dyskinesia. They are now recommended as first-line drugs for newly diagnosed schizophrenia and for patients taking typical antipsychotics but with significant adverse effects.

Risperidone is a benzisoxazole derivative with combined dopamine D2 receptor and 5HT2A-receptor blocking properties. Dosage ranges from 6 to 10 mg/day. The drug is not markedly sedative and the overall incidence and severity of extrapyramidal side-effects is lower than with more conventional antipsychotics. Hyperprolactinaemia can be problematic and prolactin levels should be monitored. Paliperidone is an active metabolite of risperidone, available in oral and depot (4 weekly) preparations.

Olanzapine has affinity for 5HT2, D1, D2, D4, and muscarinic receptor sites. Clinical studies indicate it to have a lower incidence of extrapyramidal side-effects. The apparent better compliance with the drug may be related to its lower side-effect profile and its once-daily dosage of 5–15 mg. Weight gain is a problem with long-term treatment and there is an increased risk of type 1 diabetes mellitus with this and other atypicals.

Neither risperidone nor olanzapine seems as specific a treatment for intractable chronic schizophrenia as clozapine. Other atypical antipsychotics include amisulpride, lurasidone, sulpiride, zotepine, ziprasidone and quetiapine, the latter causing less hyperprolactinaemia. Those taking atypical antipsychotics should have regular monitoring of their body mass index, cholesterol levels, blood sugar and QT interval on ECG. No more than one antipsychotic should be prescribed routinely.

Clozapine is used in patients who have intractable schizophrenia who have failed to respond to at least two conventional antipsychotic drugs or as first-line therapy. This drug is a dibenzodiazepine with a relative high affinity for D4 dopamine receptors, as compared with D1, D2, D3 and D5, in addition to muscarinic and α-adrenergic receptors. It additionally acts as a partial agonist at 5HT1A receptors, which may be of benefit in treating ‘negative’ symptoms of psychosis. Functional brain scans have shown that clozapine selectively blocks limbic dopamine receptors more than striatal ones, which is probably why it causes considerably fewer extrapyramidal side-effects. Clozapine exercises a dramatic therapeutic effect on both intractable positive and negative symptoms. However, it is expensive and produces severe agranulocytosis in 1–2% of patients. Therefore, in the UK for example, it can only be prescribed to registered patients by doctors and pharmacists registered with a patient-monitoring service. The starting dose is 25 mg per day with a maintenance dose of 150–300 mg daily. White cell counts should be monitored weekly for 18 weeks and then 2-weekly for the length of treatment. In addition to its antipsychotic actions, clozapine may also help reduce aggressive and hostile behaviour and the risk of suicide. It can cause considerable weight gain and sialorrhoea. There is an increased risk of diabetes mellitus and gastrointestinal hypomotility resulting in a functional obstruction has also been reported.

FURTHER READING

van Os J, Kapur S. Schizophrenia. Lancet 2009; 374: 635–645.

Psychological treatment

This consists of reassurance, support and a good doctor–patient relationship. Psychotherapy of an intensive or exploratory kind is contraindicated. In contrast, individual cognitive behaviour therapy can help reduce the intensity of delusions.

Social treatment

Social treatment involves attention being paid to the patient’s environment and social functioning. Family education can help relatives and partners to provide the optimal amount of emotional and social stimulation, so that not too much emotion is expressed (a risk for relapse). Sheltered employment is usually necessary for the majority of sufferers if they are to work. Assertive outreach mental health teams will follow up those poorly adhering to treatment.

Medical presentations related to treatment

The motor side-effects of neuroleptics are the commonest reason for a patient with schizophrenia to present to a physician, followed by self-harm. Acute dystonia normally arises in patients newly started on neuroleptics, causing torticollis. Extrapyramidal side-effects are common and present in the same way as Parkinson’s disease. They remit on stopping the drug and with antimuscarinic drugs, e.g. procyclidine. Akathisia is a motor restlessness, most commonly affecting the legs. It is similar to the restless legs syndrome, but apparent during the day. Amenorrhoea and galactorrhoea can be caused by dopamine antagonists. Postural hypotension can affect the elderly, and neuroleptics can be the cause of delirium in the elderly, if their antimuscarinic effects are prominent.

Long-term benefits outweigh the risks in most cases and long-term treatment is associated with a lower mortality rate when compared with no treatment. In this respect, the atypical antipsychotics are preferable to the typical antipsychotics and clozapine is the class leader in this regard.

Organic mental disorders

Organic brain disorders result from structural pathology, as in dementia, or from disturbed central nervous system (CNS) function, as in fever-induced delirium. They do not include mental and behavioural disorders due to alcohol and misuse of drugs, which are classified separately.

Delirium