Chapter 23 Psychological medicine

Introduction

Psychiatry is concerned with the study and management of disorders of mental function: primarily thoughts, perceptions, emotions and purposeful behaviours. Psychological medicine, or liaison psychiatry, is the discipline within psychiatry that is concerned with psychiatric and psychological disorders in patients who have physical complaints or conditions. This chapter will primarily concern itself with this particular branch of psychiatry.

The long-held belief that diseases are either physical or psychological has been replaced by the accumulated evidence that the brain is functionally or anatomically abnormal in most if not all psychiatric disorders. Physical, psychological and social factors, and their interactions must be looked into, in order to understand psychiatric conditions. This philosophical change of approach rejects the Cartesian dualistic approach of the mind/body biomedical model and replaces it with the more integrated biopsychosocial model.

Epidemiology (Box 23.1)

The prevalence of psychiatric disorders in the community in the UK is about 20%, mainly composed of depressive and anxiety disorders and substance misuse (mainly alcohol). The prevalence is about twice as high in patients attending the general hospital, with the highest rates in the accident and emergency department and medical wards.

![]() Box 23.1

Box 23.1

The approximate prevalence of psychiatric disorders in different populations

| Approximate percentage | |

|---|---|

Community |

20 |

Neuroses |

16 |

Psychoses |

0.5 |

Alcohol misuse |

5 |

Drug misuse |

2 (an underestimate) |

(total in community 20% due to co-morbidity) |

|

Primary care |

25 |

General hospital outpatients |

30 |

General hospital inpatients |

40 |

Culture and ethnicity

These can alter either the presentation or the prevalence of psychiatric ill-health. Biological factors in mental illness are usually similar across cultural boundaries, whereas psychological and social factors will vary. For example, the prevalence and presentation of schizophrenia vary little between countries, suggesting that biological/genetic factors are operating independently of cultural factors. In contrast, disorders in which social factors play a greater role vary between cultures, so that anorexia nervosa is found more often in developed cultures. Culture can also influence the presentation of illnesses, such that physical symptoms are more common presentations of depressive illness in Asia than in Europe. Similarly culture will influence the healthcare sought for the same condition.

The psychiatric history

As in any medical specialty, the history is essential in making a diagnosis. It is similar to that used in all specialties but tailored to help to make a psychiatric diagnosis, determine possible aetiology, and estimate prognosis. Data may be taken from several sources, including interviewing the patient, a friend or relative (usually with the patient’s permission), or the patient’s general practitioner. The patient interview also enables a doctor to establish a therapeutic relationship with the patient. Box 23.2 gives essential guidance on how to safely conduct such an interview, although it is unlikely that a patient will physically harm a healthcare professional. When interviewing a patient for the first time, follow the guidance outlined in Chapter 1 (see pp. 10–12).

![]() Box 23.2

Box 23.2

The essentials of a safe psychiatric interview

Beforehand: Ask someone of experience who knows the patient whether it is safe to interview the patient alone.

Beforehand: Ask someone of experience who knows the patient whether it is safe to interview the patient alone.

Access to others: If in doubt, interview in the view or hearing of others, or accompanied by another member of staff.

Access to others: If in doubt, interview in the view or hearing of others, or accompanied by another member of staff.

Setting: If safe; in a quiet room alone for confidentiality, not by the bed.

Setting: If safe; in a quiet room alone for confidentiality, not by the bed.

Seating: Place yourself between the door and the patient.

Seating: Place yourself between the door and the patient.

Alarm: If available, find out where the alarm is and how to use it.

Alarm: If available, find out where the alarm is and how to use it.

Components of the history are summarized in Table 23.1.

Table 23.1 Summary of the components of the psychiatric history

| Component | Description |

|---|---|

Reason for referral |

Why and how the patient came to the attention of the doctor |

Present illness |

How the illness progressed from the earliest time at which a change was noted until the patient came to the attention of the doctor |

Past psychiatric history |

Prior episodes of illness, where were they treated and how? Prior self-harm |

Past medical history |

Include emotional reactions to illness and procedures |

Family history |

History of psychiatric illnesses and relationships within the family |

Personal (biographical) history |

Childhood: Pregnancy and birth (complications, nature of delivery), early development and attainment of developmental milestones (e.g. learning to crawl, walk, talk). School history: age started and finished; truancy, bullying, reprimands; qualifications |

Adulthood: Employment (age of first, total number, reasons for leaving, problems at work), relationships (sexual orientation, age of first, total number, reasons for endings of relationships), children and dependants |

|

Reproductive history |

In women: include menstrual problems, pregnancies, terminations, miscarriages, contraception and the menopause |

Social history |

Current employment, benefits, housing, current stressors |

Personality |

This may help to determine prognosis. How do they normally cope with stress? Do they trust others and make friends easily? Irritable? Moody? A loner? This list is not exhaustive |

Drug history |

Prescribed and over-the-counter medication, units and type of alcohol/week, tobacco, caffeine and illicit drugs |

Forensic history |

Explain that you need to ask about this, since ill-health can sometimes lead to problems with the law. Note any violent or sexual offences. This is part of a risk assessment. Worst harm they have ever inflicted on someone else? Under what circumstances? Would they do the same again were the situation to recur? |

Systematic review |

Psychiatric illness is not exclusive of physical illness! The two may not only co-exist but may also have a common aetiology |

The mental state examination (MSE)

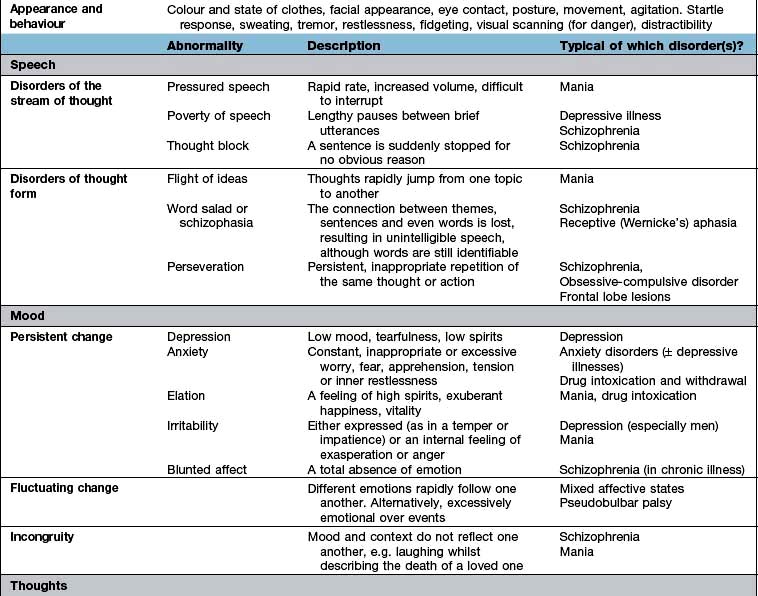

The history will already have assessed several aspects of the MSE, but the interviewer will need to expand several areas as well as test specific areas, such as cognition. The MSE is typically followed by a physical examination and is concluded with an assessment of insight, risk and a formulation that takes into account a differential diagnosis and aetiology. Each domain of the MSE is given below; abnormalities that might be detected and the disorders in which they are found are summarized in Table 23.2. The major subheadings are listed below.

Appearance and general behaviour

State and colour of clothes, facial appearance, eye contact, posture and movement provide information about a patient’s affect. Agitation and anxiety cause an easy startle response, sweating, tremor, restlessness, fidgeting, visual scanning (for danger) and even pacing up and down.

Speech

The rate, rhythm, volume and content of the patient’s speech should be examined for abnormalities. Note that speech is the only way that one can examine thoughts and as such, disorders of thought are typically seen in this section of the examination. Thought content (literally the content of their thoughts) is dealt with separately (see below). Abnormalities that may reflect neurological lesions, such as dysarthria and dysphasia, should also be assessed.

Mood and affect

The patient has an emotion or feeling, tells the doctor about their mood, and the doctor observes the patient’s affect. In psychiatric disorders, mood may be altered in three ways: a persistent change in mood, a fluctuating mood and an incongruous mood.

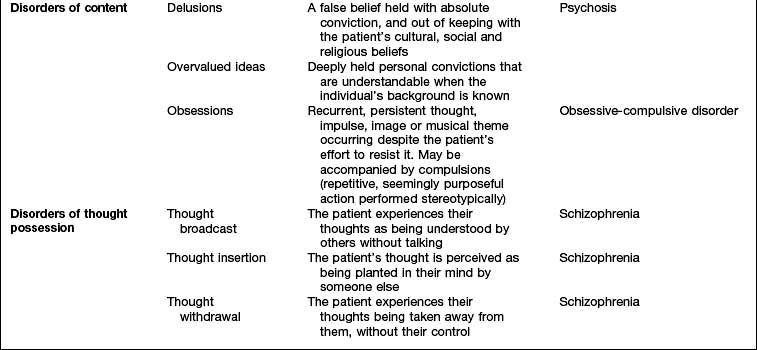

Thoughts

In addition to those abnormalities looked at under ‘speech’ (see above), abnormalities of thought content and thought possession are discussed here. Delusions (Table 23.2) can be further categorized as primary or secondary. Depending on whether they arise de novo or in the context of other abnormalities in mental state.

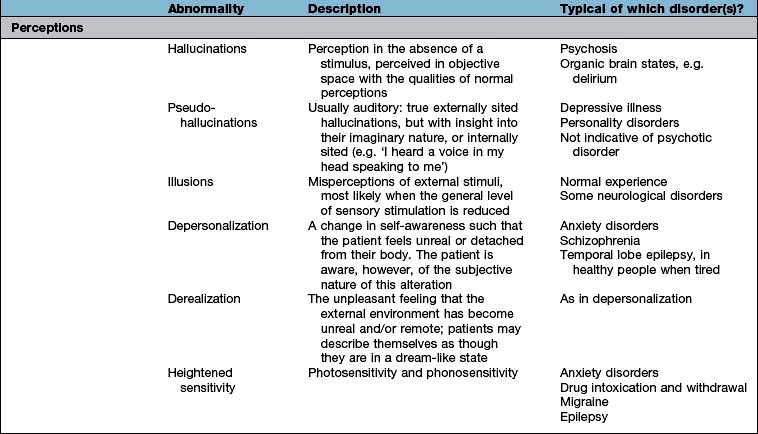

Abnormal perceptions

The assessment of perceptions in the mental state involves observation of the patient as well as asking questions of them. For example, patients experiencing auditory hallucinations may appear startled by sounds or voices that you cannot hear or may interact with them, e.g. appearing to be engaged in conversation when nobody else is in the room.

Hallucinatory phenomena can affect any sensory modality and specific types of hallucination will be dealt with later in the chapter with the disorders in which they most commonly occur.

Cognitive state

Examination of the cognitive state is necessary to diagnose organic brain disorders, such as delirium and dementia. Poor concentration, confusion and memory problems are the most common subjective complaints. Clinical testing involves the screening of cognitive functions, which may suggest the need for more formal psychometry. A premorbid estimate of intelligence, necessary to judge changes in cognitive abilities, can be made from asking the patient the final year level of education and the highest qualifications or skills achieved.

Testing can be divided into tests of diffuse and focal brain functions.

Diffuse functions

Orientation in time, place and person. Consciousness can be defined as the awareness of the self and the environment. Clouding of consciousness is more accurately a fluctuating level of awareness and is commonly seen in delirium.

Orientation in time, place and person. Consciousness can be defined as the awareness of the self and the environment. Clouding of consciousness is more accurately a fluctuating level of awareness and is commonly seen in delirium.

Attention is tested by saying the months or days backwards.

Attention is tested by saying the months or days backwards.

Verbal memory. Ask the patient to repeat a name and address with 10 or so items, noting how many times it takes to recall it 100% accurately (normal is 1 or 2) (immediate recall or registration).

Verbal memory. Ask the patient to repeat a name and address with 10 or so items, noting how many times it takes to recall it 100% accurately (normal is 1 or 2) (immediate recall or registration).

Long-term memory. Ask the patient to recall the news of that morning or recently. If they are not interested in the news, find out their interests and ask relevant questions (about their football team or favourite soap opera). Amnesia is literally an absence of memory and dysmnesia indicates a dysfunctioning memory.

Long-term memory. Ask the patient to recall the news of that morning or recently. If they are not interested in the news, find out their interests and ask relevant questions (about their football team or favourite soap opera). Amnesia is literally an absence of memory and dysmnesia indicates a dysfunctioning memory.

Focal functions

Frontal, temporal and parietal function tests are covered in chapter 22. Note any disinhibited behaviour not explained by another psychiatric illness. Sequential tasks are tested by asking the patient to alternate making a fist with one hand at the same time as a flat hand with the other. Ask the patient to tap a table once if you tap twice and vice-versa. Note any motor perseveration whereby the patient cannot change the movement once established. Observe for verbal perseveration, in which the patient repeats the same answer as given previously for a different question. Abstract thinking is measured by asking the meaning of common proverbs, a literal meaning suggesting frontal lobe dysfunction, assuming reasonable premorbid intelligence.

Assessing cognitive dysfunction

Questions on: orientation (e.g. time, date, place); registration (naming objects); attention and calculation (simple arithmetic); recall (previously mentioned objects); and language (understanding commands). This correlates well with more time-consuming intelligence quotient (IQ) tests, but it will not as easily pick up cognitive problems caused by focal brain lesions. Simple questioning will detect about 90% of people with cognitive impairments, with about 10% false positives.

Insight and illness beliefs

Insight is the degree to which a person recognizes that he or she is unwell, and is minimal in people with a psychosis. Illness beliefs are the patient’s own explanations of their ill health, including diagnosis and causes. These beliefs should be elicited because they can help to determine prognosis and adherence with treatment, whatever the diagnosis.

Risk

The assessment of risk may sound daunting but it is fundamental to clinical practice; for instance when determining whether a patient presenting with chest pain should be reviewed in the resuscitation room of the emergency department rather than a normal cubicle. Risk must be assessed in people with a psychiatric diagnosis, albeit that the nature of ‘risk’ is different.

Risk can be broken down into two parts: the risk that the patient poses to themselves and that which they pose to others (Table 23.3). You will have already made an appraisal of risk in your initial preparations for seeing the patient (Box 23.2) and in checking ‘forensic history’ (Table 23.1). It may be necessary to obtain additional information from family, friends or professionals who know the patient – this may save time and prove invaluable.

Table 23.3 The assessment of risk

| Risk to self | Risk to others | |

|---|---|---|

Active |

Acts of self-harm or suicide attempts |

Aggression towards others – this may be actual violence or threatening behaviour |

Look for prior history of self-harm and what may have precipitated or prevented it |

A past history of aggression is a good predictor of its recurrence. Look at the severity and quality of and remorse for prior violent acts as well as identifiable precipitants that might be avoided in the future (e.g. alcohol) |

|

Passive |

Self-neglect |

Neglect of others – always find out whether children or other dependants are at home |

Manipulation by others |

Severe behavioural disturbance

Patients who are aggressive or violent cause understandable apprehension in all staff, and are most commonly seen in the accident and emergency department. Information from anyone accompanying the patient, including police or carers, can help considerably. Box 23.3 gives the main causes of disturbed behaviour.

Management of the severely disturbed patient

The primary aims of management are control of dangerous behaviour and establishment of a provisional diagnosis. Three specific strategies may be necessary when dealing with the violent patient:

Remember that the behaviour exhibited is a reflection of an underlying disorder and as such portrays suffering and often fear. The approach to the agitated or even the violent patient therefore must take this into account and the steps used are with the intention of alleviating this suffering whilst maintaining the safety of the individual, the other patients and staff. Technically speaking, this management begins at the point of an initial assessment that takes into account prior episodes of disturbed behaviour and its precipitants. Armed with this knowledge it may be possible to prevent a recurrence.

‘Verbal de-escalation’. If a patient’s behaviour causes concern, the first step is to try and defuse the situation. Put more simply, this means talking to the patient. It may be something that is relatively simple to correct that has led to the disturbed behaviour such as staff explaining their intentions in approaching the patient.

Medication may be used but an effort should always be made to offer this on an oral basis. The protocol in the UK is to offer a short-acting benzodiazepine in the first instance, such as lorazepam (0.5–1 mg). Patients suffering from a psychotic disorder and who are already taking antipsychotics may be more appropriately treated with an antipsychotic but do not assume that this is the case and be wary of the ‘neuroleptic-naive’ patient. In the delirious or elderly patient, benzodiazepines should be avoided, as they may worsen any underlying confusion and can cause paradoxical agitation. In this instance, low-dose haloperidol is appropriate (2.5–5 mg). More recently, antihistamines have been added to this protocol, such as promethazine. Medications should be given sequentially, rather than all at once, where possible and allowing between 30 min and 1 h for them to take effect.

Physical restraint. In the instance that the above measures do not resolve the situation, physical restraint may be necessary in order to maintain safety and to administer medications on an intramuscular basis (note that for haloperidol this will alter the maximum dose it is safe to use in a 24-hour period). This should not be the first step taken nor should it be performed by staff unless they have been adequately trained in approved methods of control and restraint. This will typically mean nursing staff on a psychiatric ward or security staff on a general medical or surgical ward. Although this may vary between countries, in the UK it is the case that doctors will never be involved in the restraint of the patient. Restraint is a potentially dangerous intervention, even more so when mixed with psychotropic medication, and deaths have occurred as a direct consequence.

Monitoring. If medications (oral or otherwise) are employed, with or without restraint, regular monitoring of physical parameters such as blood pressure, pulse, respiratory rate and oxygen saturation should be performed at a frequency dictated by the level of ongoing agitation and consciousness.

FURTHER READING

NICE. Violence: The short term management of disturbed/violent behaviour in in-patient psychiatric settings and emergency departments. Clinical Guideline 25. London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, February 2005; www.nice.org.uk

Defence mechanisms

Although not strictly part of the mental state examination, it is useful to be able to identify psychological defences in ourselves and our patients. Defence mechanisms are mental processes that are usually unconscious. Some of the most commonly used defence mechanisms are described in Table 23.4 and are useful in understanding many aspects of behaviour.

Table 23.4 Common defence mechanisms

| Defence mechanism | Description |

|---|---|

Repression |

Exclusion from awareness of memories, emotions and/or impulses that would cause anxiety or distress if allowed to enter consciousness |

Denial |

Similar to repression and occurs when patients behave as though unaware of something that they might be expected to know, e.g. a patient who, despite being told that a close relative has died, continues to behave as though the relative were still alive |

Displacement |

Transferring of emotion from a situation or object with which it is properly associated to another that gives less distress |

Identification |

Unconscious process of taking on some of the characteristics or behaviours of another person, often to reduce the pain of separation or loss |

Projection |

Attribution to another person of thoughts or feelings that are in fact one’s own |

Regression |

Adoption of primitive patterns of behaviour appropriate to an earlier stage of development. It can be seen in ill people who become child-like and highly dependent |

Sublimation |

Unconscious diversion of unacceptable behaviours into acceptable ones |

The relevant physical examination

This should be guided by the history and mental state examination. Particular attention should usually be paid to the neurological and endocrinological examinations when organic brain syndromes and affective illnesses are suspected.

Summary or formulation

When the full history and mental state have been assessed, the doctor should make a concise assessment of the case, which is termed a formulation. In addition to summarizing the essential features of the history and examination, the formulation includes a differential diagnosis, a discussion of possible causal factors, and an outline of further investigations or interviews needed. It concludes with a concise plan of treatment and a statement of the likely prognosis.

Classification of psychiatric disorders

The classification of psychiatric disorders into categories is mainly based on symptoms and behaviours, since there are currently few diagnostic tests for psychiatric disorders. There currently exists an unhelpful dualistic division of psychiatric disorders from neurological diseases, since the pathologies of at least the majority of each group of conditions are located in the brain, e.g. Alzheimer’s disease causing dementia and a pseudobulbar palsy causing emotional lability.

Psychiatric classifications have traditionally divided up disorders into neuroses and psychoses.

Neuroses are illnesses in which symptoms vary only in severity from normal experiences, such as depressive illness.

Neuroses are illnesses in which symptoms vary only in severity from normal experiences, such as depressive illness.

Psychoses are illnesses in which symptoms are qualitatively different from normal experience, with little insight into their nature, such as schizophrenia.

Psychoses are illnesses in which symptoms are qualitatively different from normal experience, with little insight into their nature, such as schizophrenia.

There are several problems with a neurotic-psychotic dichotomy. First, neuroses may be as severe in their effects as psychoses. Second, neuroses may cause symptoms that fulfil the definition of psychotic symptoms. For instance, someone with anorexia nervosa may be convinced that they are fat when they are thin, and this belief would meet all the criteria for a delusional belief. Yet we would traditionally classify the illness as a neurosis.

The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders published by the World Health Organization has largely abandoned the traditional division between neurosis and psychosis, although the terms are still used. The disorders are now arranged in groups according to major common themes (e.g. mood disorders and delusional disorders). A classification of psychiatric disorders derived from ICD-10 is shown in Table 23.5, and this is the classification mainly used in this chapter (ICD-11 will be available in 2014).

Table 23.5 International classification of psychiatric disorders (ICD-10)

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of the American Psychiatric Association (DSM-IV-TR) is an alternative classification system (DSM-V in 2013).

FURTHER READING

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edn. Text Revision (DSM-5). Washington, DC: APA; 2013.

World Health Organization. The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders: Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1992.

Causes of a psychiatric disorder

A psychiatric disorder may result from several causes which may interact. It is most helpful to divide causes into the three ‘Ps’: predisposing, precipitating and perpetuating factors.

Predisposing factors often stem from early life and include genetic, pregnancy and delivery, previous emotional traumas and personality factors.

Predisposing factors often stem from early life and include genetic, pregnancy and delivery, previous emotional traumas and personality factors.

Precipitating (triggering) factors may be physical, psychological or social in nature. Whether they produce a disorder depends on their nature, severity and the presence of predisposing factors. For instance a death of a close, rather than distant, family member is more likely to precipitate a pathological grief reaction in someone who has not come to terms with a previous bereavement.

Precipitating (triggering) factors may be physical, psychological or social in nature. Whether they produce a disorder depends on their nature, severity and the presence of predisposing factors. For instance a death of a close, rather than distant, family member is more likely to precipitate a pathological grief reaction in someone who has not come to terms with a previous bereavement.

Perpetuating (maintaining) factors prolong the course of a disorder after it has occurred. Again they may be physical, psychological or social, and several are often active and interacting at the same time. For example, high levels of criticism at home combined with taking cannabis, as relief from the criticism, may help to maintain schizophrenia.

Perpetuating (maintaining) factors prolong the course of a disorder after it has occurred. Again they may be physical, psychological or social, and several are often active and interacting at the same time. For example, high levels of criticism at home combined with taking cannabis, as relief from the criticism, may help to maintain schizophrenia.

Psychiatric aspects of physical disease

People with non-psychiatric, ‘physical’ diseases are more likely to suffer from psychiatric disorders than those who are well. The most common psychiatric disorders in physically unwell patients are mood or adjustment disorders and acute organic brain disorders (delirium). The relationship between psychological and physical symptoms may be understood in one of four ways:

Psychological distress and disorders can precipitate physical diseases (e.g. the cardiac risk associated with depressive disorders or hypokalaemia causing arrhythmias in anorexia nervosa).

Psychological distress and disorders can precipitate physical diseases (e.g. the cardiac risk associated with depressive disorders or hypokalaemia causing arrhythmias in anorexia nervosa).

Physical diseases and their treatments can cause psychological symptoms or ill-health (Table 23.6).

Physical diseases and their treatments can cause psychological symptoms or ill-health (Table 23.6).

Both the psychological and physical symptoms are caused by a common disease process (e.g. Huntington’s chorea).

Both the psychological and physical symptoms are caused by a common disease process (e.g. Huntington’s chorea).

Physical and psychological symptoms and disorders may be independently co-morbid, particularly in the elderly.

Physical and psychological symptoms and disorders may be independently co-morbid, particularly in the elderly.

Table 23.6 Psychiatric conditions sometimes caused by physical diseases

| Psychiatric disorders/symptom | Physical disease |

|---|---|

Depressive illness |

Hypothyroidism |

Cushing’s syndrome |

|

Steroid treatment |

|

Brain tumour |

|

Anxiety disorder |

Thyrotoxicosis |

Hypoglycaemia (transient) |

|

Phaeochromocytoma |

|

Complex partial seizures (transient) |

|

Alcohol withdrawal |

|

Irritability |

Post-concussion syndrome |

Frontal lobe syndrome |

|

Hypoglycaemia (transient) |

|

Memory problem |

Brain tumour |

Hypothyroidism |

|

Altered behaviour |

Acute drug intoxication |

Postictal state |

|

Acute delirium |

|

Dementia |

|

Brain tumour |

Factors that increase the risk of a psychiatric disorder in someone with a physical disease are shown in Table 23.7.

Table 23.7 Factors increasing the risk of psychiatric disorders in the general hospital

Patient factors |

Setting |

Physical conditions |

Treatment |

Differences in treatment

Although the basic principles are the same as in treating psychiatric illnesses in the physically healthy, there are some differences:

Uncertainty regarding the physical diagnosis or prognosis, with its attendant tendency to imagine the worst, is often a triggering or maintaining factor, particularly in an adjustment or mood disorder. Good two-way communication between doctor and patient, with time taken to listen to the patient’s concerns, is often the most effective ‘antidepressant’ available.

Uncertainty regarding the physical diagnosis or prognosis, with its attendant tendency to imagine the worst, is often a triggering or maintaining factor, particularly in an adjustment or mood disorder. Good two-way communication between doctor and patient, with time taken to listen to the patient’s concerns, is often the most effective ‘antidepressant’ available.

The history may reveal the role of a physical disease or treatment exacerbating the psychiatric condition, which should then be addressed (Table 23.6). For example, the dopamine agonist bromocriptine can precipitate a psychosis.

The history may reveal the role of a physical disease or treatment exacerbating the psychiatric condition, which should then be addressed (Table 23.6). For example, the dopamine agonist bromocriptine can precipitate a psychosis.

When prescribing psychotropic drugs, the dose should be reduced in disorders affecting pharmacokinetics, e.g. fluoxetine in renal or hepatic failure.

When prescribing psychotropic drugs, the dose should be reduced in disorders affecting pharmacokinetics, e.g. fluoxetine in renal or hepatic failure.

Drug interactions should be of particular concern, e.g. lithium and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

Drug interactions should be of particular concern, e.g. lithium and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

Sometimes a physical treatment may be planned that may exacerbate the psychiatric condition. An example would be high-dose steroids as part of chemotherapy in a patient with leukaemia and depressive illness.

Sometimes a physical treatment may be planned that may exacerbate the psychiatric condition. An example would be high-dose steroids as part of chemotherapy in a patient with leukaemia and depressive illness.

Always remember the risk of suicide in an inpatient with a mood disorder and take steps to reduce that risk; for example, moving the patient to a room on the ground floor and/or having a registered mental health nurse attend the patient while at risk.

Always remember the risk of suicide in an inpatient with a mood disorder and take steps to reduce that risk; for example, moving the patient to a room on the ground floor and/or having a registered mental health nurse attend the patient while at risk.

The sick role and illness behaviour

The sick role describes behaviour usually adopted by ill people. Such people are not expected to fulfil their normal social obligations. They are treated with sympathy by others and are only obliged to see their doctor and take medical advice or treatments.

Illness behaviour is the way in which given symptoms may be differentially perceived, evaluated and acted (or not acted) upon by different kinds of persons. We all have illness behaviour when we choose what to do about a symptom. Going to see a doctor is generally more likely with more severe, distressing and numerous symptoms. It is also more likely in introspective individuals who focus on their health.

Abnormal illness behaviour occurs when there is a discrepancy between the objective pathology present and the patient’s response to it, in spite of adequate medical investigation and explanation.

Functional or psychosomatic disorders

So-called functional (in contrast to ‘organic’) disorders are illnesses in which there is no obvious pathology or anatomical change in an organ and there is a presumed dysfunction of an organ or system. Examples are given in Table 23.8. The psychiatric classification of these disorders would be somatoform disorders, but they do not fit easily within either medical or psychiatric classification systems, since they occupy the borderland between them. This classification also implies a dualistic ‘mind or body’ dichotomy, which is not supported by neuroscience. Since current classifications still support this outmoded understanding, this chapter will address these conditions in this way.

Table 23.8 ‘Functional’ somatic syndromes

The word psychosomatic has had several meanings, including psychogenic, ‘all in the mind’, imaginary and malingering. The modern meaning is that psychosomatic disorders are syndromes in which both physical and psychological factors are likely to be causative. So-called medically unexplained symptoms and syndromes are very common in both primary care and the general hospital (over half the outpatients in gastroenterology and neurology clinics have these syndromes). Because orthodox medicine has not been particularly effective in treating or understanding these disorders, many patients perceive their doctors as unsympathetic and seek out complementary or even alternative treatments of uncertain efficacy.

Because epidemiological studies suggest that having one of these syndromes significantly increases the risk of having another, some doctors believe that these syndromes represent different manifestations of a single ‘functional syndrome’, indicating a global somatization process. Functional disorders also have a significant association with depressive and anxiety disorders. Against this view is the evidence that the majority of primary care people with most of these disorders do not have either a mood or other functional disorder. It also seems that it requires a major stress or the development of a co-morbid psychiatric disorder in order for such sufferers to see their doctor, which might explain why doctors are so impressed with the associations with both stress and psychiatric disorders. Doctors have historically tended to diagnose ‘stress’ or ‘psychosomatic disorders’ in people with symptoms that they cannot explain. History is full of such disorders being reclassified as research clarifies the pathology. An example is writer’s cramp (p. 1122) which most neurologists now agree is a dystonia rather than a neurosis.

The likelihood is that these functional disorders will be reclassified as their causes and pathophysiology are revealed. Functional brain scans suggest enhancement of brain activity during interoception in more than one syndrome. Interoception is the perception of internal (visceral) phenomena, such as a rapid heartbeat.

Chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS)

There has probably been more controversy over the existence and cause of CFS than any other ‘functional’ syndrome in recent decades. This is reflected in its uncertain classification as neurasthenia in the psychiatric classification and myalgic encephalomyelitis (ME) under neurological diseases. There is now good evidence for the independent existence of this syndrome, although the diagnosis is made clinically and by exclusion of other fatiguing disorders. Its prevalence is 0.5–2.5% worldwide, mainly depending on how it is defined. It occurs most commonly in women between the ages of 20 and 50 years.

Clinical features

The cardinal symptom is chronic fatigue made worse by minimal exertion. The fatigue is usually both physical and mental, associated most commonly with:

Mood disorders are present in a large minority of patients, and can cause problems in diagnosis because of the overlap in symptoms. These mood disorders may be secondary, independent (co-morbid), or primary (with a misdiagnosis of CFS).

Aetiology

Functional disorders often have some aetiological factors in common with each other (Table 23.9), as well as more specific aetiologies. For instance, CFS can be triggered by certain infections, such as infectious mononucleosis and viral hepatitis. About 10% of patients who have infectious mononucleosis have CFS 6 months after the onset of infection, yet there is no evidence of persistent infection in these patients. Those fatigue states which clearly do follow on a viral infection can also be classified as post-viral fatigue syndromes.

Table 23.9 Aetiological factors commonly seen in ‘functional’ disorders

Other aetiological factors are uncertain. Immune and endocrine abnormalities noted in CFS may be secondary to the inactivity or sleep disturbance commonly seen. The role of stress is uncertain, with some indication that the influence of stress is mediated through consequent psychiatric disorders exacerbating fatigue, rather than any direct effect.

Management

The general principles of the management of functional disorders are given in Box 23.4. Specific management of CFS should include a mutually agreed and supervised programme of gradually increasing activity. However, only a quarter of patients recover after treatment. It is sometimes difficult to persuade a patient to accept what are inappropriately perceived as ‘psychological therapies’ for such a physically manifested condition. Antidepressants do not work in the absence of a mood disorder or insomnia.

![]() Box 23.4

Box 23.4

Management of functional somatic syndromes

The first principle is the identification and treatment of maintaining factors (e.g. dysfunctional beliefs and behaviours, mood and sleep disorders).

Stopping drugs (e.g. caffeine causing insomnia, analgesics causing dependence)

Stopping drugs (e.g. caffeine causing insomnia, analgesics causing dependence)

Prognosis

Prognosis is poor without treatment, with less than 10% of hospital attenders recovered after 1 year. Outcomes are worse with greater severity, increasing age, co-morbid mood disorders, and the conviction that the illness is entirely physical. A large trial showed that about 60% improve with active rehabilitative treatments, such as graded exercise therapy and cognitive behaviour therapy when added to specialist medical care.

FURTHER READING

White PD, Goldsmith KA, Johnson AL et al. Comparison of adaptive pacing therapy, cognitive behaviour therapy, graded exercise therapy, and specialist medical care for chronic fatigue syndrome (PACE): a randomised trial. Lancet 2011; 377:823–836.

White PD. Chronic fatigue syndrome: Is it one discrete syndrome or many? Implications for the “one vs. many” functional somatic syndromes debate. J Psychosom Res 2010; 68:455–459.

Fibromyalgia (chronic widespread pain, CWP)

This controversial condition of unknown aetiology overlaps with chronic fatigue syndrome, with both conditions causing fatigue and sleep disturbance (see p. 1162). Diffuse muscle and joint pains are more constant and severe in CWP, although the ‘tender points’, previously thought to be pathognomonic, are now known to be of no diagnostic importance (see p. 509.) Different specialists have different views.

CWP occurs most commonly in women aged 40–65 years, with a prevalence in the community of between 1% and 11%. There are associations with depressive and anxiety disorders, other functional disorders, physical deconditioning and a possibly characteristic sleep disturbance (Table 23.9). Functional brain scans suggest that patients actually perceive greater pain, supporting the idea of abnormal sensory processing, and this may be in part related to abnormalities in the regulation of central opioidergic mechanisms.

Management

Apart from the general principles in Box 23.4, management also consists of:

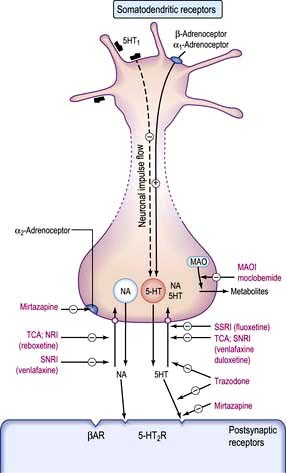

A meta-analysis suggests that tricyclic antidepressants that inhibit reuptake of both serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine – 5HT) and noradrenaline (norepinephrine) (e.g. amitriptyline, dosulepin) have the greatest effect on sleep, fatigue and pain. The doses used are too low for antidepressant effect and the drugs may work through their hypnotic and analgesic effects. Other centrally acting anti-nociceptive agents that are also antidepressants include duloxetine and milnacipran, used at full doses, or anticonvulsants, such as pregabalin and gabapentin.

Other chronic pain syndromes

A chronic pain syndrome is a condition of chronic disabling pain for which no medical cause can be found. The psychiatric classification would be a persistent somatoform pain disorder, but this is unsatisfactory since the criteria include the stipulation that emotional factors must be the main cause, and it is clinically difficult to be that certain.

The main sites of chronic pain syndromes are the head, face, neck, lower back, abdomen, genitalia or all over (CWP, fibromyalgia). ‘Functional’ low back pain is the commonest ‘physical’ reason for being off sick long term in the UK (p. 503). Quite often, a minor abnormality will be found on investigation (such as mild cervical spondylosis on the neck X-ray), but this will not be severe enough to explain the severity of the pain and resultant disability. These pains are often unremitting and respond poorly to analgesics. Sleep disturbance is almost universal and co-morbid psychiatric disorders are commonly found.

Aetiology

The perception of pain involves sensory (nociceptive), emotional and cognitive processing in the brain. Functional brain scans suggest that the brain responds abnormally to pain in these conditions, with increased activation in response to chronic pain. This could be related to conditioned behavioural and physiological responses to the initial acute pain. The brain may then adapt to the prolonged stimulus of the pain by changing its central processing. The prefrontal cortex, thalamus and cingulate gyrus seem to be particularly affected and some of these areas are involved in the emotional appreciation of pain in general. Thus, it is possible to start to understand how beliefs, emotions and behaviours might influence the perception of chronic pain (Table 23.9).

Management

Management involves the same principles as used in other functional syndromes (Box 23.4). Since analgesics are rarely effective, and can cause long-term harm, patients should be encouraged to gradually reduce their use. It is often helpful to involve the patient’s immediate family or partner, to ensure that the partner is also supported and not unconsciously discouraging progress.

Specific drug treatments are few:

Nerve blocks are not usually effective.

Nerve blocks are not usually effective.

Anticonvulsants such as carbamazepine, gabapentin and pregabalin may be given a therapeutic trial if the pain is thought to be neuropathic (see p. 1124).

Anticonvulsants such as carbamazepine, gabapentin and pregabalin may be given a therapeutic trial if the pain is thought to be neuropathic (see p. 1124).

Tricyclic antidepressants: The antidepressant dosulepin is an effective treatment in half of the patients who have atypical facial pain, and this effect seems to be independent of dosulepin’s effect on mood. Another tricyclic antidepressant, amitriptyline, is helpful in tension headaches, which might be related to its independent analgesic effect. Amitriptyline has the added bonus of increasing slow wave sleep, which may be why it is more effective than NSAIDs in chronic widespread pain.

Tricyclic antidepressants: The antidepressant dosulepin is an effective treatment in half of the patients who have atypical facial pain, and this effect seems to be independent of dosulepin’s effect on mood. Another tricyclic antidepressant, amitriptyline, is helpful in tension headaches, which might be related to its independent analgesic effect. Amitriptyline has the added bonus of increasing slow wave sleep, which may be why it is more effective than NSAIDs in chronic widespread pain.

Tricyclic antidepressants that affect both serotonin and noradrenaline (norepinephrine) reuptake (e.g. p. 1172) seem to be more effective than more selective noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors, e.g. in neuropathic pain. There is some evidence that tricyclics are generally superior to SSRIs in chronic pain syndromes.

Irritable bowel syndrome

This is one of the commonest functional syndromes, affecting some 10–30% of the population worldwide. The clinical features and management of the syndrome and the related functional bowel disorders are described in more detail in chapter 6. Although the majority of sufferers with the irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) do not have a psychiatric disorder, depressive illness should be excluded in people with constipation and a poor appetite. Anxiety disorders should be excluded in people with nausea and diarrhoea. Persistent abdominal pain or a feeling of emptiness may occasionally be the presenting symptom of a severe depressive illness, particularly in the elderly, with a nihilistic delusion that the body is empty or dead inside (see p. 1168).

Management

This is dealt with in more detail in Box 23.4. Seeing a physician who provides specific education that particularly addresses individual illness beliefs and concerns can provide lasting benefit. Psychological therapies that help the more severely affected include:

If indicated, the choice of antidepressant should be determined by the effects of these drugs on bowel transit times, with tricyclic antidepressants normally slowing and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) (p. 1172) normally speeding up transit times.

Multiple chemical sensitivity, Candida hypersensitivity, and food allergies

Some complementary health practitioners, doctors and patients themselves make diagnoses of multiple chemical sensitivities (MCS) (e.g. to foods, smoking, perfumes, petrol), Candida hypersensitivity and allergies (to food, tap-water and even electricity). Symptoms and syndromes attributed to these putative disorders are numerous and variable and include all the functional disorders, mood disorders and arthritis. Scientific support for the existence of these disorders is weak, particularly when double-blind methodologies have been used.

Type 1 hypersensitivities to foods such as nuts certainly exist, although they are fortunately uncommon (approximately 3/1000) (see pp. 68, 69). Direct specific food intolerances also occur (e.g. chocolate with migraine, caffeine with IBS).

Candidiasis can occur in the gastrointestinal tract in immunocompromised individuals, such as those with AIDS. Vaginal candidiasis can occur after antibiotic treatment in otherwise healthy women. A double-blind and controlled study of nystatin in women diagnosed as having candidiasis hypersensitivity syndrome showed that vaginitis was the only condition relieved more by nystatin than placebo. There is little evidence of Candida having a systemic role in other symptoms.

In spite of this evidence, the patient is often convinced of the legitimacy and usefulness of these diagnoses and their treatments.

Aetiology

Surveys of patients diagnosed with MCS or food allergies have shown high rates of current and previous mood and anxiety disorders (Table 23.9). Eating disorders (p. 1188) should be excluded in people with food intolerances. Some patients taking very low carbohydrate diets as putative treatments may develop reactive hypoglycaemia after a high carbohydrate meal, which they then interpret as a food allergy.

Classical conditioning can produce intolerance to foods and smells in healthy people and this may be a causative mechanism in some people with intolerance. This supports the existence of these intolerance conditions, but suggests they may be conditioned responses with attendant physiological consequences. This might explain why double-blinding sometimes abolishes the reaction to the stimulus.

Management

The general principles in Box 23.4 apply. If one assumes a phobic or conditioned response is responsible, graded exposure (systematic desensitization) to the conditioned stimulus may be worthwhile. Preliminary studies do suggest that this approach may successfully treat such intolerances, in the context of cognitive behaviour therapy.

Premenstrual syndrome

The premenstrual syndrome (PMS) consists of both physical and psychological symptoms that regularly occur during the premenstrual phase and substantially diminish or disappear soon after the period starts.

Physical symptoms include headache, fatigue, breast tenderness, abdominal distension and fluid retention.

Physical symptoms include headache, fatigue, breast tenderness, abdominal distension and fluid retention.

Psychological symptoms can include irritability, emotional lability or low mood, and tension.

Psychological symptoms can include irritability, emotional lability or low mood, and tension.

The premenstrual (late luteal) dysphoric disorder (PMDD) is a severe form of PMS with marked mood swings, irritability, depression and anxiety accompanying the physical symptoms. Women who generally suffer from mood disorders may be more prone to experience this disorder. The prevalence of PMS does not vary between cultures and is reported by the majority (75%) of women at some time in their lives. Severely disabling PMS (PMDD) occurs in about 3–8% of women.

The cause of the premenstrual syndrome remains unclear, although exacerbating factors include some of those outlined in Table 23.9. Research suggests that abnormalities of reproductive hormone receptors may play a role.

Management

The general principles in Box 23.4 apply. Treatments with vitamin B6 (p. 210), diuretics, progesterone, oral contraceptives, oil of evening primrose and oestrogen implants or patches (balanced by cyclical norethisterone) remain empirical. Psychotherapies aimed at enhancing the patient’s coping skills can reduce disability. Two trials suggest that graded exercise therapy improves symptoms. Several studies have demonstrated that SSRIs (p. 1172) are effective treatments for the premenstrual dysphoric disorder.

The menopause

The clinical features and management of the menopause are described on page 973. A prospective study has shown that there is no increased incidence of depressive disorders at this time. Such a significant bodily change, sometimes occurring at the same time as children leaving home, is naturally accompanied by an emotional adjustment that does not normally amount to a pathological state.

Somatoform disorders

As explained in the section on functional disorders (p. 1162), the classification of somatoform disorders is unsatisfactory because of the uncertain nature and aetiology of these disorders. However, there are certain disorders, beyond those described in ‘functional disorders’, that present frequently and coherently enough to be usefully recognized.

Somatization disorder

One in 10 patients presenting with a functional disorder will fulfil the criteria of a chronic somatization disorder. The condition is composed of multiple, recurrent, medically unexplained physical symptoms, usually starting early in adult life. Symptoms may be referred to almost any part or bodily system. The patient has often had multiple medical opinions and repeated negative investigations. Medical reassurance that the symptoms do not have a demonstrable physical cause fails to reassure the patient, who will continue to ‘doctor-shop’. The patient is usually reluctant to accept a psychological and/or social explanation for the symptoms. Abnormal illness behaviour is evident and patients can be attention-seeking and dependent on doctors. Yet they can complain about the medical care and attention they have previously received.

The aetiology is unknown, but both mood and personality disorders are often also present. It is often associated with dependence upon or misuse of prescribed medication, usually sedatives and analgesics. There is often a history of significant childhood traumas, or chronic ill-health in the child or parent, which may play an aetiological role or help to explain difficult therapeutic relationships (Table 23.9). The condition is probably the somatic presentation of psychological distress, although iatrogenic damage (from postoperative and drug-related problems) soon complicates the clinical picture. The course of the disorder is chronic and disabling, with long-standing family, marital and/or occupational problems.

Hypochondriasis

The conspicuous feature is a preoccupation with an assumed serious disease and its consequences. Patients commonly believe that they suffer from cancer or AIDS, or some other serious condition. Characteristically, such patients repeatedly request laboratory and other investigations to either prove they are ill or reassure themselves that they are well. Such reassurance rarely lasts long before another cycle of worry and requests begins. The symptom of hypochondriasis may be secondary to or associated with a variety of psychiatric disorders, particularly depressive and anxiety disorders. Occasionally the hypochondriasis is delusional, secondary to schizophrenia or a depressive psychosis. Hypochondriasis may co-exist with physical disease but the diagnostic point is that the patient’s concern is disproportionate and unjustified.

Management of somatoform disorders

The principles outlined in Box 23.4 apply to these disorders. Since they have a poor prognosis, the aim is to minimize disability. Furthermore, it is vital that all members of staff and close family members adopt the same approach to the patient’s problems. The patients often consciously or unconsciously split both medical staff and family members into ‘good’ and ‘bad’ (or caring and uncaring) people, as a way of projecting their distress.

Patients appreciate a discussion and explanation of their symptoms. The doctor should sensitively explore possible psychological and social difficulties, if possible by demonstrating links between symptoms and stresses. Such discussion usually gives information that can be used to formulate an agreed plan of management. A contract of mutually agreed care involving the appropriate professionals (general practitioner, and a choice of psychotherapist, health psychologist, complementary health professional, physician or psychiatrist), with agreed frequency of visits and a review date, can be helpful in managing the condition. Management also includes cessation of reassurance that no serious disease has been uncovered, since this simply reinforces dependence on the doctor. Repeated laboratory investigations should be discouraged.

Cognitive behaviour therapy has been shown to provide effective rehabilitation in significant numbers of patients suffering from a somatoform disorder.

Dissociative/conversion disorders

A dissociative disorder is a condition in which there is a profound loss of awareness or cognitive ability without medical explanation. The term dissociative indicates the disintegration of different mental activities, and covers such phenomena as amnesia, fugues and pseudoseizures (non-epileptic attacks).

Conversion disorder occurs when an unresolved conflict is converted into usually symbolic physical symptoms as a defence against it. Such symptoms commonly include paralysis, abnormal movements, sensory loss, aphonia, disorders of gait and pseudocyesis (false pregnancy). The lifetime prevalence has been estimated at 3–6 per 1000 in women, with a lower prevalence in men. Most cases begin before the age of 35 years. Dissociation is unusual in the elderly.

Clinical features

The various symptoms are usually divided into dissociative and conversion categories (Table 23.10). Dissociative disorders have the following three characteristics that are necessary in order to make the diagnosis:

They occur in the absence of physical pathology that would fully explain the symptoms.

They occur in the absence of physical pathology that would fully explain the symptoms.

They are produced unconsciously.

They are produced unconsciously.

Symptoms are not caused by overactivity of the sympathetic nervous system.

Symptoms are not caused by overactivity of the sympathetic nervous system.

Table 23.10 Common dissociative/conversion symptoms

| Dissociative (mental) | Conversion (physical) |

|---|---|

Other characteristics include:

Symptoms and signs often reflect a patient’s ideas about illness.

Symptoms and signs often reflect a patient’s ideas about illness.

There is usually abnormal illness behaviour, with exaggeration of disability.

There is usually abnormal illness behaviour, with exaggeration of disability.

There may have been significant childhood traumas.

There may have been significant childhood traumas.

Primary gain is the immediate relief from the emotional conflict.

Primary gain is the immediate relief from the emotional conflict.

Secondary gain refers to the social advantage gained by the patient by being ill and disabled (sympathy of family and friends, being off work, disability pension).

Secondary gain refers to the social advantage gained by the patient by being ill and disabled (sympathy of family and friends, being off work, disability pension).

Physical disease is not uncommonly also present (e.g. pseudoseizures are more common in someone with epilepsy).

Physical disease is not uncommonly also present (e.g. pseudoseizures are more common in someone with epilepsy).

Dissociative amnesia commences suddenly. Patients are unable to recall long periods of their lives and may even deny any knowledge of their previous life or personal identity. In a dissociative fugue, patients not only lose their memory but wander away from their usual surroundings, and, when found, deny all memory of their whereabouts during this wandering. The differential diagnosis of a fugue state includes post-epileptic automatism, depressive illness and alcohol misuse.

Multiple personality disorder is rare, but dramatic, and may be triggered by suggestion on the part of a psychotherapist. There are rapid alterations between two or more ‘personalities’ in the same person, each of which is repressed and dissociated from the other ‘personalities’. A differential diagnosis is rapid cycling manic depressive disorder which would explain sudden apparent changes in personality.

Differential diagnosis

Dissociation is usually a stable and reliable diagnosis over time, although high rates of co-morbid mood and personality disorders are found in chronic sufferers. Particular care should be taken to make the diagnosis on positive grounds, and not simply on the basis of an absence of a medical diagnosis. Care should also be taken to exclude or treat co-morbid psychiatric disorders.

Aetiology

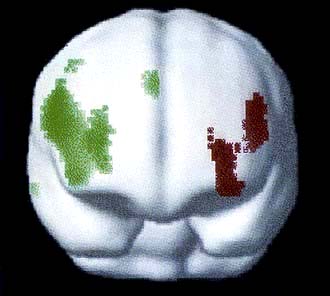

Functional brain scans differ between healthy controls feigning a motor abnormality and people with a similar conversion motor symptom, which suggests that dissociation involves different areas of the brain from simulation (Fig. 23.1). Functional brain scanning of a patient with conversion paralysis has shown that recalling a past trauma not only activated the emotional areas, such as the amygdala, but also reduced motor cortex activity. This would suggest that conversion involves a disinhibition of voluntary will at an unconscious level, so that the patient can no longer will something to happen.

Figure 23.1 Statistical parametric maps superimposed on an MRI scan of the anterior surface of the brain, orientated as though looking at a person head on. Red region shows hypofunction of people with conversion motor symptoms. The green region shows hypofunction of healthy controls feigning the same motor abnormality.

(From Spence SA, Crimlisk HL, Cope H et al. Discrete neurophysiological correlates in prefrontal cortex during hysterical and feigned disorders of movement. Lancet 355:1243–1244, with permission.)

The psychoanalytical theory of dissociation is that it is the result of emotionally charged memories that are repressed into the unconscious at some point in the past. Symptoms are explained as the combined effects of repression and the symbolic conversion of this emotional energy into physical symptoms. This hypothesis is difficult to test, although there is some evidence that people with dissociative disorders are more likely to have suffered childhood abuse, particularly when the abuse was both sexual and physical and started early in childhood. Caution should be taken with such a history obtained by therapies that ‘recover’ childhood memories that were previously completely unknown to the patient.

People with dissociative disorders by definition adopt both the sick role and abnormal illness behaviour, with consequent secondary gains that help to maintain the illness.

Management

The treatment of dissociation is similar to the treatment of somatoform disorders in general, outlined above and in Box 23.4. The first task is to engage the patient and their family with an explanation of the illness that makes sense to them, is acceptable, and leads to the appropriate management. An invented example of a suitable explanation is given in Box 23.5. Such an explanation would be modified by mutual discussion until an agreed understanding was achieved, which would serve as a working model for the illness. Provision of a rehabilitation programme that addresses both the physical and psychological needs and problems of the patient would then be planned.

A graded and mutually agreed plan for a return to normal function can usually be led by the appropriate therapist (e.g. speech therapist for dysphonia, physiotherapist for paralysis).

A graded and mutually agreed plan for a return to normal function can usually be led by the appropriate therapist (e.g. speech therapist for dysphonia, physiotherapist for paralysis).

At the same time, a psychotherapeutic assessment should be made in order to determine the appropriate form of psychotherapy. For instance, couple therapy will address a significant relationship difficulty; individual psychotherapy could ease an unresolved conflict from childhood.

At the same time, a psychotherapeutic assessment should be made in order to determine the appropriate form of psychotherapy. For instance, couple therapy will address a significant relationship difficulty; individual psychotherapy could ease an unresolved conflict from childhood.

![]() Box 23.5

Box 23.5

An example of an explanation that might be given for a dissociative disorder

You told me about the tremendous shock you felt when your mother suddenly died. This was particularly the case since you hadn’t spoken to her for so long beforehand, after that big disagreement with her over your wedding to John. You weren’t able to say good-bye before she died. Your brain was overloaded with grief, guilt and anger all at once. I wonder whether that is why you aren’t able to speak now. I wonder whether it’s difficult to think of anything to say that would make things right, particularly since you can’t speak with your mother now.

Abreaction brought about by hypnosis or by intravenous injections of small amounts of midazolam may produce a dramatic, if sometimes short-lived, recovery. In the abreactive state, the patient is encouraged to relive the stressful events that provoked the disorder and to express the accompanying emotions, i.e. to abreact. Such an approach has been useful in the treatment of acute dissociative states in wartime, but appears to be of less value in civilian life. It should only be contemplated in the presence of an anaesthetist with suitable resuscitation equipment to hand.

Hypnotherapy is psychotherapy while the patient is in a hypnotic trance, the idea being that therapy is more possible because the patient is relaxed and not using repression. This may allow the therapist access to the previously unconscious emotional conflicts or memories. There are no published trials of this technique in dissociation, which Freud gave up as unsuccessful in order to found psychoanalysis, but some hypnotherapists claim good results. Care should be taken to avoid a catastrophic emotional reaction when the patient is suddenly faced with the previously repressed memories.

Prognosis

Most cases of recent onset recover quickly with treatment, which is why a positive diagnosis should be made early. Those cases that last longer than a year are likely to persist, with entrenched abnormal illness behaviour patterns. One study found that 83% were still unwell at 12 years’ follow-up.

FURTHER READING

olde Hartman TC, Borghuis MS, Lucassen PL et al. Medically unexplained symptoms, somatisation disorder and hypochondriasis: course and prognosis. A systematic review. J Psychosom Res 2009; 66:363–377.

Stone J, Smyth R, Carson A et al. Systematic review of misdiagnosis of conversion symptoms and “hysteria”. BMJ 2005; 331:989.

Sleep difficulties

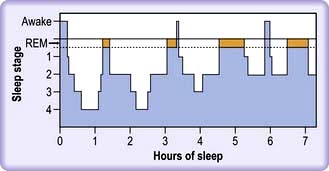

Sleep is divided into rapid eye movement (REM) and non-REM sleep:

As drowsiness begins, the alpha rhythm on an EEG disappears and is replaced by deepening slow wave activity (non-REM).

As drowsiness begins, the alpha rhythm on an EEG disappears and is replaced by deepening slow wave activity (non-REM).

After 60–90 minutes, this slow wave pattern is replaced by low amplitude waves on which are superimposed rapid eye movements lasting a few minutes.

After 60–90 minutes, this slow wave pattern is replaced by low amplitude waves on which are superimposed rapid eye movements lasting a few minutes.

This cycle is repeated during the duration of sleep, with the REM periods becoming longer and the slow wave periods shorter and less deep (Fig. 23.2).

This cycle is repeated during the duration of sleep, with the REM periods becoming longer and the slow wave periods shorter and less deep (Fig. 23.2).

Figure 23.2 Sleep architecture, showing cycles of slow wave sleep interspersed with rapid eye movement (REM) sleep. Sleep is ‘staged’ by the electroencephalogram (EEG). Deeper sleep (stages 3 and 4) is demonstrated by slow waves on the EEG. Sleep occurs in cycles, light sleep (accompanied by REM sleep and dreaming) to deep sleep and back again, and these cycles last about 90 min.

REM sleep is accompanied by dreaming and physiological arousal. Slow wave sleep is associated with release of anabolic hormones and cytokines, with an increased cellular mitotic rate. It helps to maintain host defences, metabolism and repair of cells. For this reason slow wave sleep is increased in those conditions where growth or conservation is required (e.g. adolescence, pregnancy, thyrotoxicosis).

Insomnia is difficulty in sleeping; a third of adults complain of insomnia and in a third of these, it can be severe.

Primary sleep disorders include sleep apnoea (p. 818), narcolepsy which responds to tigotine, the restless legs syndrome (Ekbom’s) (see p. 616) and the related periodic leg movement disorder, in which the legs (and sometimes the arms) jerk while asleep.

Delayed sleep phase syndrome occurs when the circadian pattern of sleep is delayed so that the patient sleeps from the early hours until mid-day or later, and is most common in young people. Night terrors, sleep-walking and sleep-talking are non-REM phenomena, called parasomnias, are most commonly found in children, but can recur in adults when under stress or suffering from a mood disorder. Sleep disorders secondary to another medical diagnosis will not be discussed here.

Psychophysiological insomnia commonly occurs secondary to functional, mood and substance misuse disorders, and when under stress (Box 23.6). It can often be triggered by one of these factors, but then become a habit on its own, driven by anticipation of insomnia and day-time naps.

![]() Box 23.6

Box 23.6

Common causes of insomnia

Insomnia causes day-time sleepiness and fatigue, with consequences such as road traffic accidents. Assessment should pay particular attention to mood, life difficulties and drug intake (especially alcohol, nicotine and caffeine), and the timing of the insomnia should be ascertained:

Initial insomnia (trouble getting off to sleep) is common in mania, anxiety, depressive disorders and substance misuse.

Initial insomnia (trouble getting off to sleep) is common in mania, anxiety, depressive disorders and substance misuse.

Middle insomnia (waking up in the middle of the night) occurs with medical conditions such as sleep apnoea and prostatism.

Middle insomnia (waking up in the middle of the night) occurs with medical conditions such as sleep apnoea and prostatism.

Late insomnia (early morning waking) is caused by depressive illness and malnutrition (anorexia nervosa).

Late insomnia (early morning waking) is caused by depressive illness and malnutrition (anorexia nervosa).

Habitual alcohol consumption should be carefully estimated since even a small excess can be a potent cause of insomnia, as well as recent withdrawal. Caffeine is perhaps the most commonly taken drug in the UK, and its effects are easily underestimated. Six cups of real coffee a day are likely to cause insomnia in the average healthy adult. Caffeine is not only found in tea and coffee, but is also found in chocolate, cola drinks and some analgesics. Prescription drugs that can either disturb sleep or cause vivid dreams include most appetite suppressants, glucocorticoids, dopamine agonists, lipid-soluble beta-blockers (e.g. propranolol) and certain psychotropic drugs (especially when first prescribed, e.g. fluoxetine, reboxetine, risperidone).

Hypersomnia is not uncommon in adolescents with depressive illness, occurs in narcolepsy, and may temporarily follow infections such as infectious mononucleosis.

Management of insomnia

This is determined by diagnosis. Where none is immediately apparent, it is worth educating the patient about sleep hygiene. In addition:

Simple measures such as decreasing alcohol intake, having supper earlier, exercising daily, having a hot bath prior to going to bed and establishing a routine of going to bed at the same time should all be tried.

Simple measures such as decreasing alcohol intake, having supper earlier, exercising daily, having a hot bath prior to going to bed and establishing a routine of going to bed at the same time should all be tried.

Relaxation techniques and cognitive behaviour therapy have a role in those with intractable insomnia.

Relaxation techniques and cognitive behaviour therapy have a role in those with intractable insomnia.

Short half-life benzodiazepines can be useful for acute insomnia, but should not be used for more than 2 weeks continuously to avoid dependence.

Short half-life benzodiazepines can be useful for acute insomnia, but should not be used for more than 2 weeks continuously to avoid dependence.

Non-benzodiazepine hypnotics (zaleplon, zopiclone, zolpidem) act at the benzodiazepine receptors and occasional dependence has been reported.

Non-benzodiazepine hypnotics (zaleplon, zopiclone, zolpidem) act at the benzodiazepine receptors and occasional dependence has been reported.

Certain antihistamines (e.g. diphenhydramine and promethazine) and antidepressants (e.g. amitriptyline, trimipramine, trazodone, mirtazapine) are not addictive and can be used as hypnotics in low dose, with the added advantage of improving slow wave sleep. The commonest side-effects are morning sedation and weight gain.

Certain antihistamines (e.g. diphenhydramine and promethazine) and antidepressants (e.g. amitriptyline, trimipramine, trazodone, mirtazapine) are not addictive and can be used as hypnotics in low dose, with the added advantage of improving slow wave sleep. The commonest side-effects are morning sedation and weight gain.

Mood (affective) disorders

Classification

The central feature of these disorders is an abnormality of mood. Mood is best described in terms of a continuum ranging from severe depression at one extreme to severe mania at the other, with the normal, stable mood in the middle. Mood disorders are divided into bipolar and unipolar affective disorders.

Bipolar affective disorder

Patients suffer bouts of both depression and mania. Although mania can rarely occur by itself without depressive mood swings (thus being ‘unipolar’), it is far more commonly found in association with depressive swings, even if sometimes it takes several years for the first depressive illness to appear.

Bipolar I disorder is defined as one or more manic or mixed (signs of mania and depression) episodes.

Bipolar I disorder is defined as one or more manic or mixed (signs of mania and depression) episodes.

Bipolar II is defined as a depressive episode with at least one episode of hypomania (this is shorter lived than mania and is not accompanied by psychotic symptoms). Hypomania is noticeably abnormal but does not result in functional impairment or hospitalization.

Bipolar II is defined as a depressive episode with at least one episode of hypomania (this is shorter lived than mania and is not accompanied by psychotic symptoms). Hypomania is noticeably abnormal but does not result in functional impairment or hospitalization.

Bipolar III disorder is less well established and describes depressive episodes, with hypomania occurring only when taking an antidepressant.

Bipolar III disorder is less well established and describes depressive episodes, with hypomania occurring only when taking an antidepressant.

About 10% of patients who have depressive illness are eventually found to have a bipolar illness.

Depressive disorders

Depressive disorders or ‘episodes’ are classified by the ICD-10 as mild, moderate or severe, with or without somatic symptoms. Severe depressive episodes are divided according to the presence or absence of psychotic symptoms.

Clinical features of depressive disorder

Whereas everyone will at some time or other feel ‘fed up’ or ‘down in the dumps’, it is when such symptoms become qualitatively different, pervasive or interfere with normal functioning that a depressive illness has occurred. Depressive disorder, clinical or ‘major’ depression, is characterized by disturbances of mood, speech, energy and ideas (Table 23.11). Patients often describe their symptoms in physical terms. Marked fatigue and headache are the two most common physical symptoms in depressive illness and may be the first symptoms to appear. Patients describe the world as looking grey, themselves as lacking a zest for living, being devoid of pleasure and interest in life (anhedonia). Anxiety and panic attacks are common; secondary obsessional and phobic symptoms may emerge. Symptoms should last for at least 2 weeks and should cause significant incapacity (e.g. trouble working or relating to others) in order to be dealt with as an illness.

Table 23.11 Characteristic features of depressive illness

| Characteristic | Clinical features |

|---|---|

Mood |

Depressed, miserable or irritable |

Talk |

Impoverished, slow, monotonous |

Energy |

Reduced, lethargic, lacking motivation |

Ideas |

Feelings of futility, guilt, self-reproach, unworthiness, hypochondriacal preoccupations, worrying, suicidal thoughts, delusions of guilt, nihilism and persecution |

Cognition |

Impaired learning, pseudodementia in elderly patients |

Physical |

Insomnia (especially early waking), poor appetite and weight loss, constipation, loss of libido, erectile dysfunction, bodily pains |

Behaviour |

Retardation or agitation, poverty of movement and expression |

Hallucinations |

Auditory – often hostile, critical |

In the more severe forms, diurnal variation in mood can occur, feeling worse in the morning, after waking in the early hours with apprehension. Suicidal ideas are more frequent, intrusive and prolonged. Delusions of guilt, persecution and bodily disease are not uncommon, along with second-person auditory hallucinations insulting the patient or suggesting suicide. In severe depressive illness, particularly in the elderly, concentration and memory can be so badly affected that the patient appears to have dementia (pseudodementia). Delusions of poverty and non-existence (nihilism) occur particularly in this age group. Suicide is a real risk, with the lifetime risk being approximately 5% in primary care patients, but 15% in those with depressive illness severe enough to warrant admission to hospital. People with bipolar disorder are also at greater risk of suicide. Screening questions for depressive illness are shown in Box 23.7.

![]() Box 23.7

Box 23.7

Screening questions for depressive illness

During the last month, have you often been bothered by feeling down, depressed or hopeless?

During the last month, have you often been bothered by feeling down, depressed or hopeless?

During the last month, have you often been bothered by having little interest or pleasure in doing things?

During the last month, have you often been bothered by having little interest or pleasure in doing things?

If one or both of the answers is ‘yes’, assess further for depressive illness.

Epidemiology

About a third of the population will feel unhappy at any one time, but this is not the same as depressive illness; the middle-aged feel least happy compared to the young and elderly. The point prevalence of depressive illness is 5% in the community, with a further 3% having dysthymia (see below). It is more common in women, but there is no increase with age, and no difference by ethnic group or socioeconomic class (apart from a clear association with unemployment). Married and never married people have similar prevalence rates, with separated and divorced people having two to three times the prevalence. Some studies have suggested that depressive illness is becoming more common.

Depressive illnesses are more common in the presence of:

physical diseases, particularly if chronic, stigmatizing or painful

physical diseases, particularly if chronic, stigmatizing or painful

excessive and chronic alcohol use (probably the most depressing drug humans use)