Conception Through Adolescence

• Discuss common physiological and psychosocial health concerns during the transition of the child from intrauterine to extrauterine life.

• Describe characteristics of physical growth of the unborn child and from birth to adolescence.

• Describe cognitive and psychosocial development from birth to adolescence.

• Explain the role of play in the development of a child.

• Discuss ways in which the nurse is able to help parents meet their children’s developmental needs.

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Potter/fundamentals/

Stages of Growth and Development

Human growth and development are continuous and complex processes that are typically divided into stages organized by age-groups such as from conception to adolescence. Although this chronological division is arbitrary, it is based on the timing and sequence of developmental tasks that the child must accomplish to progress to another stage. This chapter focuses on the various physical, psychosocial, and cognitive changes and health risks and health promotion concerns during the different stages of growth and development.

Selecting a Developmental Framework for Nursing

Providing developmentally appropriate nursing care is easier when you base planning on a theoretical framework (see Chapter 11). An organized, systematic approach ensures that the plan of care assesses and meets the child’s and family’s needs. If you deliver nursing care only as a series of isolated actions, you will possibly overlook some of the child’s developmental needs. A developmental approach encourages organized care directed at the child’s current level of functioning to motivate self-direction and health promotion. For example, nurses encourage toddlers to feed themselves to advance their developing independence and thus promote their sense of autonomy. Another example involves a nurse understanding an adolescent’s need to be independent and thus establishing a contract about the care plan and its implementation.

Intrauterine Life

From the moment of conception until birth, human development proceeds at a predictive and rapid rate. During gestation or the prenatal period, the embryo grows from a single cell to a complex, physiological being. All major organ systems develop in utero, with some functioning before birth. Development proceeds in a cephalocaudal (head-to-toe) and proximal-distal (central-to-peripheral) pattern (Santrock, 2009).

Pregnancy that reaches full term is calculated to last an average of 38 to 40 weeks and is divided into three stages or trimesters. Beginning on the day of fertilization, the first 14 days are referred to as the preembryonic stage, followed by the embryonic stage that lasts from day 15 until the eighth week. These two stages are then followed by the fetal stage that lasts from the end of the eighth week until birth (Davidson et al., 2008). Gestation is commonly divided into equal phases of 3 months called trimesters.

The placenta begins development at the third week of the embryonic stage and produces essential hormones that help maintain the pregnancy. It functions as the fetal lungs, kidneys, gastrointestinal tract, and an endocrine organ. Because the placenta is extremely porous, noxious materials such as viruses, chemicals, and drugs also pass from mother to child. These agents are called teratogens and can cause abnormal development of structures in the embryo. The effect of teratogens on the fetus or unborn child depends on the developmental stage in which exposure takes place, individual genetic susceptibility, and the quantity of the exposure. The embryonic stage is the most vulnerable since all body organs are formed by the eighth week. Some maternal infections can cross the placental barrier and negatively influence the health of the mother, fetus, or both. It is important to educate women about avoidable sources of teratogens and help them make healthy lifestyle choices before and during pregnancy.

Health Promotion During Pregnancy

The diet of a woman both before and during pregnancy has a significant effect on fetal development. Women who do not consume adequate nutrients and calories during pregnancy may not be able to meet the fetus’ nutritional requirements. An increase in weight does not always indicate an increase in nutrients. In addition, the pattern of weight gain is important for tissue growth in a mother and fetus. For women who are at normal weight for height, the recommended weight gain is 25 to 35 pounds over three trimesters (Davidson et al., 2008). As a nurse, you are in a key position to provide women with the education they need about nutrition before conception and throughout an expectant mother’s pregnancy.

Pregnancy presents a developmental challenge that includes physiological, cognitive, and emotional states that are accompanied by stress and anxiety. The expectant woman will soon adopt a parenting role; and relationships within the family will change, whether or not there is a partner involved. Pregnancy can be a period of conflict or support; family dynamics impact fetal development. Parental reactions to pregnancy change throughout the gestational period, with most couples looking forward to the birth and addition of a new family member (Davidson et al., 2008). Listen carefully to concerns expressed by a mother and her partner and offer support through each trimester.

The age of the pregnant woman sometimes plays a role in the health of the fetus and the overall pregnancy. Fetuses of older mothers are at risk for chromosomal defects, and older women may have more difficulty in becoming pregnant (Santrock, 2009). Studies indicate that pregnant adolescents often seek out less prenatal care than women in their 20s and 30s and are at higher risk for complications of pregnancy and labor. Infants of teen mothers are at increased risk for prematurity; low birth weight; and exposure to alcohol, drugs, and tobacco in utero and early childhood (Davidson et al., 2008). Adolescents who have been able to participate in prenatal classes may have improved nutrition and healthier babies.

Fetal growth and hormonal changes during pregnancy often result in discomfort for the expectant mother. Common concerns expressed include problems such as nausea and vomiting, breast tenderness, urinary frequency, heartburn, constipation, ankle edema, and backache. Always anticipate these discomforts and provide self-care education throughout the pregnancy. Discussing the physiological causes of these discomforts and offering suggestions for safe treatment can be very helpful for expectant mothers and contribute to overall health during pregnancy (Davidson et al., 2008).

Some complementary and alternative therapies such as herbal supplements can be harmful during pregnancy. Your assessment should include questions about use of these substances when providing education during pregnancy (Davidson et al., 2008). You can promote maternal and fetal health by providing accurate and complete information about health behaviors that support positive outcomes for pregnancy and childbirth.

Transition from Intrauterine to Extrauterine Life

The transition from intrauterine to extrauterine life requires profound physiological changes in the newborn and occurs during the first 24 hours of life. Assessment of the newborn during this period is essential to ensure that the transition is proceeding as expected. Gestational age and development, exposure to depressant drugs before or during labor, and the newborn’s own behavioral style also influence the adjustment to the external environment.

Physical Changes

An immediate assessment of the newborn’s condition to determine the physiological functioning of the major organ systems occurs at birth. The most widely used assessment tool is the Apgar score. Heart rate, respiratory effort, muscle tone, reflex irritability, and color are rated to determine overall status of the newborn. The Apgar assessment is generally conducted at 1 and 5 minutes after birth and is sometimes repeated until the newborn’s condition stabilizes. The most extreme physiological change occurs when the newborn leaves the utero circulation and develops independent circulatory and respiratory functioning.

Nursing interventions at birth include maintaining an open airway, stabilizing and maintaining body temperature, and protecting the newborn from infection. The removal of nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal secretions with suction or a bulb syringe ensures airway patency. Newborns are susceptible to heat loss and cold stress. Because hypothermia increases oxygen needs, it is essential to stabilize and maintain the newborn’s body temperature. Healthy newborns may be placed directly on the mother’s abdomen and covered in warm blankets or provided warmth via a radiant warmer. Preventing infection is a major concern in the care of the newborn, whose immune system is immature. Good handwashing technique is the most important factor in protecting the newborn from infection. You can help prevent infection by instructing parents and visitors to wash their hands before touching the infant.

Psychosocial Changes

After immediate physical evaluation and application of identification bracelets, the nurse promotes the parents’ and newborn’s need for close physical contact. Early parent-child interaction encourages parent-child attachment. Merely placing the family together does not promote closeness. Most healthy newborns are awake and alert for the first half-hour after birth. This is a good time for parent-child interaction to begin. Close body contact, often including breastfeeding, is a satisfying way for most families to start bonding. If immediate contact is not possible, incorporate it into the care plan as early as possible, which means bringing the newborn to an ill parent or bringing the parents to an ill or premature child. Attachment is a process that evolves over the infant’s first 24 months of life, and many psychologists believe that a secure attachment is an important foundation for psychological development in later life (Santrock, 2009).

Newborn

The neonatal period is the first 28 days of life. During this stage the newborn’s physical functioning is mostly reflexive, and stabilization of major organ systems is the primary task of the body. Behavior greatly influences interaction among the newborn, the environment, and caregivers. For example, the average 2-week-old smiles spontaneously and is able to look at the mother’s face. The impact of these reflexive behaviors is generally a surge of maternal feelings of love that prompt the mother to cuddle the baby. You apply knowledge of this stage of growth and development to promote newborn and parental health. For example, the newborn’s cry is generally a reflexive response to an unmet need (such as hunger, fatigue, or discomfort). Thus you help parents identify ways to meet these needs by counseling them to feed their baby on demand rather than on a rigid schedule.

Physical Changes

You perform a comprehensive nursing assessment as soon as the newborn’s physiological functioning is stable, generally within a few hours after birth. At this time the nurse measures height, weight, head and chest circumference, temperature, pulse, and respirations and observes general appearance, body functions, sensory capabilities, reflexes, and responsiveness. Following a comprehensive physical assessment, assess gestational age and interactions between infant and parent that indicate successful attachment (Hockenberry and Wilson, 2011).

The average newborn is 2700 to 4000 g (6 to 9 pounds), 48 to 53 cm (19 to 21 inches) in length, and has a head circumference of 33 to 35 cm (13 to 14 inches). Neonates lose up to 10% of birth weight in the first few days of life, primarily through fluid losses by respiration, urination, defecation, and low fluid intake. They usually regain birth weight by the second week of life; and a gradual pattern of increase in weight, height, and head circumference is evident. Accurate measurement as soon as possible after birth provides a baseline for future comparison (Hockenberry and Wilson, 2011).

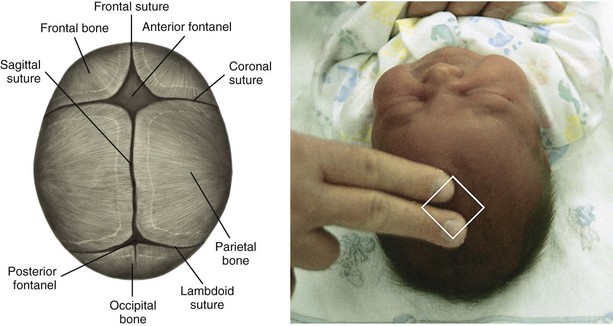

Normal physical characteristics include the continued presence of lanugo on the skin of the back; cyanosis of the hands and feet for the first 24 hours; and a soft, protuberant abdomen. Skin color varies according to racial and genetic heritage and gradually changes during infancy. Molding, or overlapping of the soft skull bones, allows the fetal head to adjust to various diameters of the maternal pelvis and is a common occurrence with vaginal births. The bones readjust within a few days, producing a rounded appearance to the head. The sutures and fontanels are usually palpable at birth. Fig. 12-1 shows the diamond shape of the anterior fontanel and the triangular shape of the posterior fontanel between the unfused bones of the skull. The anterior fontanel usually closes at 12 to 18 months, whereas the posterior fontanel closes by the end of the second or third month.

FIG. 12-1 Fontanels and suture lines. (From Hockenberry MJ, Wilson D: Wong’s nursing care of infants and children, ed 9, St Louis, 2011, Mosby.)

Assess neurological function by observing the newborn’s level of activity, alertness, irritability, and responsiveness to stimuli and the presence and strength of reflexes. Normal reflexes include blinking in response to bright lights, startling in response to sudden loud noises or movement, sucking, rooting, grasping, yawning, coughing, sneezing, palmar grasp, swallowing, plantar grasp, Babinski, and hiccoughing. Assessment of these reflexes is vital because the newborn depends largely on reflexes for survival and in response to its environment. Fig. 12-2 shows the tonic neck reflex in the newborn.

FIG. 12-2 Tonic neck reflex. Newborns assume this position while supine. (From Hockenberry MJ, Wilson D: Wong’s nursing care of infants and children, ed 9, St Louis, 2011, Mosby.)

Normal behavioral characteristics of the newborn include periods of sucking, crying, sleeping, and activity. Movements are generally sporadic, but they are symmetrical and involve all four extremities. The relatively flexed fetal position of intrauterine life continues as the newborn attempts to maintain an enclosed, secure feeling. Newborns normally watch the caregiver’s face; have a nonpurposeful reflexive smile; and respond to sensory stimuli, particularly the primary caregiver’s face, voice, and touch.

In accordance with the recommendations of the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), position infants for sleep on their backs to decrease the risk of sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) (Hockenberry and Wilson, 2011; Santrock, 2008). Newborns establish their individual sleep-activity cycle, and parents develop sensitivity to their baby’s cues. Studies have found that parents position their infants at home in the same positions they observed in the hospital setting; thus nurses must demonstrate correct positioning on the back to reduce the incidence of SIDS (Davidson et al., 2008). Co-sleeping or bed sharing has also been reported to possibly be associated with an increased risk for SIDS (Hockenberry and Wilson, 2011; Santrock, 2008). Safeguards include proper positioning; removing stuffed animals, soft bedding, and pillows; and avoiding overheating the infant. Individuals should avoid smoking during pregnancy and around the infant because it places the infant at greater risk for SIDS (Hockenberry and Wilson, 2011).

Cognitive Changes

Early cognitive development begins with innate behavior, reflexes, and sensory functions. Newborns initiate reflex activities, learn behaviors, and learn their desires. At birth infants are able to focus on objects about 20 to 25 cm (8 to 10 inches) from their faces and perceive forms. A preference for the human face is apparent. Teach parents about the importance of providing sensory stimulation such as talking to their babies and holding them to see their faces. This allows infants to seek or take in stimuli, thereby enhancing learning and promoting cognitive development.

For newborns crying is a means of communication to provide cues to parents. Some babies cry because their diapers are wet or they are hungry or want to be held. Others cry just to make noise or because they need a change in position or activity. The crying frustrates the parents if they cannot see an apparent cause. With the nurse’s help parents learn to recognize infants’ cry patterns and take appropriate action when necessary.

Psychosocial Changes

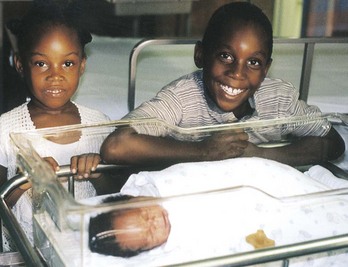

During the first month of life most parents and newborns normally develop a strong bond that grows into a deep attachment. Interactions during routine care enhance or detract from the attachment process. Feeding, hygiene, and comfort measures consume much of infants’ waking time. These interactive experiences provide a foundation for the formation of deep attachments. Early on older siblings need to have opportunity to be involved in the newborn’s care. Family involvement helps support growth and development and promotes nurturing (Fig. 12-3).

If parents or children experience health complications after birth, this may compromise the attachment process. Infants’ behavioral cues are sometimes weak or absent, and caregiving is possibly less mutually satisfying. Some tired or ill parents have difficulty interpreting and responding to their infants. Preterm infants and those born with congenital anomalies are often too weak to be responsive to parental cues and require special supportive nursing care. For example, infants born with heart defects tire easily during feedings. Nurses can support parental attachment by pointing out positive qualities and responses of the newborn and acknowledging how difficult the separation can be for parents and infant.

Health Promotion

Newborn screening tests are administered before babies leave the hospital to identify serious or life-threatening conditions before symptoms begin. Results of the screening tests are sent directly to the infant’s pediatrician. If a screening test suggests a problem, the baby’s physician usually follows up with further testing and may refer the infant to a specialist for treatment if needed. Blood tests help determine inborn errors of metabolism (IEMs). These are genetic disorders caused by the absence or deficiency of a substance, usually an enzyme, essential to cellular metabolism that results in abnormal protein, carbohydrate, or fat metabolism. Although IEMs are rare, they account for a significant proportion of health problems in children. Neonatal screening is done to detect phenylketonuria (PKU), hypothyroidism, galactosemia, and other diseases to allow appropriate treatment that prevents permanent mental retardation and other health problems.

The AAP recommends universal screening of newborn hearing before discharge since studies have indicated that the incidence of hearing loss is as high as 1 to 3 per 1000 normal newborns (Davidson et al., 2008). If health care providers detect the loss before 3 months of age and intervention is initiated by 6 months, children are able to achieve normal language development that matches their cognitive development through the age of 5 (Hockenberry and Wilson, 2011).

Car Seats

An essential component of discharge teaching is the use of a federally approved car seat for transporting the infant from the hospital or birthing center to home. Automobile injuries are a leading cause of death in children in the United States. Many of these deaths occur when the child is not properly restrained (Hockenberry and Wilson, 2011). Parents need to learn how to properly fit the restraint to the infant and how to properly install the car seat. All infants and toddlers should ride in a rear-facing car safety seat until they are 2 years of age or until they reach the highest weight or height allowed by the manufacturer or their car safety seat (American Academy of Pediatrics, 2011a). Placing an infant in a rear-facing restraint in the front seat of a vehicle is extremely dangerous in any vehicle with a passenger-side air bag. Nurses are responsible for providing education on the use of a car seat before discharge from the hospital.

Cribs and Sleep

Beginning June 28, 2011, new federal safety standards prohibit the manufacture or sale of drop-side rail cribs (American Academy of Pediatrics, 2011b). New cribs sold in the United States must meet these governmental standards for safety, but some older cribs were manufactured before the newer requirements were instituted. Unsafe cribs should be disassembled and thrown away (American Academy of Pediatrics, 2011b). Parents also need to inspect an older crib to make sure the slats are no more than 6 cm (2.4 inches) apart. The crib mattress should fit snugly, and crib toys or mobiles should be attached firmly with no hanging strings or straps. Instruct parents to remove mobiles as soon as the infant is able to reach them (Hockenberry and Wilson, 2011). Also consider using a portable play yard, as long as it is not a model that has been recalled.

Infant

During infancy, the period from 1 month to 1 year of age, rapid physical growth and change occur. This is the only period distinguished by such dramatic physical changes and marked development. Psychosocial developmental advances are aided by the progression from reflexive to more purposeful behavior. Interaction between infants and the environment is greater and more meaningful for the infant. During this first year of life the nurse easily observes the adaptive potential of infants because changes in growth and development occur so rapidly.

Physical Changes

Steady and proportional growth of the infant is more important than absolute growth values. Charts of normal age- and gender-related growth measurements enable the nurse to compare growth with norms for a child’s age. Measurements recorded over time are the best way to monitor growth and identify problems. Size increases rapidly during the first year of life; birth weight doubles in approximately 5 months and triples by 12 months. Height increases an average of 2.5 cm (1 inch) during each of the first 6 months and about 1.2 cm ( inch) each month until 12 months (Hockenberry and Wilson, 2011).

inch) each month until 12 months (Hockenberry and Wilson, 2011).

Throughout the first year the infant’s vision and hearing continue to develop. Some infants as young as  months are able to link visual and auditory stimuli (Santrock, 2009). Patterns of body function also stabilize, as evidenced by predictable sleep, elimination, and feeding routines. Some reflexes that are present in the newborn such as blinking, yawning, and coughing remain throughout life; whereas others such as grasping, rooting, sucking, and the Moro or startle reflex disappear after several months.

months are able to link visual and auditory stimuli (Santrock, 2009). Patterns of body function also stabilize, as evidenced by predictable sleep, elimination, and feeding routines. Some reflexes that are present in the newborn such as blinking, yawning, and coughing remain throughout life; whereas others such as grasping, rooting, sucking, and the Moro or startle reflex disappear after several months.

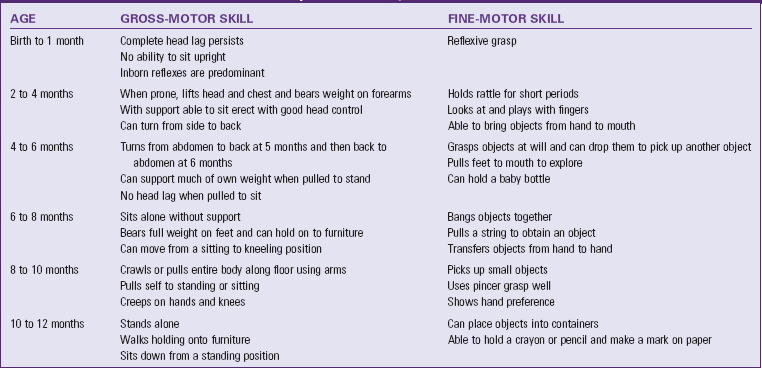

Gross-motor skills involve large muscle activities and are usually closely monitored by parents who easily report recently achieved milestones. Newborns can only momentarily hold their heads up, but by 4 months most infants have no head lag. The same rapid development is evident as infants learn to sit, stand, and then walk. Fine-motor skills involve small body movements and are more difficult to achieve than gross-motor skills. Maturation of eye-and-hand coordination occurs over the first 2 years of life as infants move from being able to grasp a rattle briefly at 2 months to drawing an arc with a pencil by 24 months. Development proceeds at a variable pace for each individual but usually follows the same pattern and within the same time frame (Table 12-1).

Cognitive Changes

The complex brain development during the first year is demonstrated by the infant’s changing behaviors. As he or she receives stimulation through the developing senses of vision, hearing, and touch, the developing brain interprets the stimuli. Thus the infant learns by experiencing and manipulating the environment. Developing motor skills and increasing mobility expand an infant’s environment and, with developing visual and auditory skills, enhance cognitive development. For these reasons Piaget (1952) named his first stage of cognitive development, which extends until around the third birthday, the sensorimotor period. Today’s researchers have many more methods available to study the cognitive development of infants, and they believe that infants are far more competent than Piaget was able to discern by observation alone (Santrock, 2009) (see Chapter 11).

Infants need opportunities to develop and use their senses. Nurses need to evaluate the appropriateness and adequacy of these opportunities. For example, ill or hospitalized infants sometimes lack the energy to interact with their environment, thereby slowing their cognitive development. Infants need to be stimulated according to their temperament, energy, and age. The nurse uses stimulation strategies that maximize the development of infants while conserving their energy and orientation. An example of this is a nurse talking to and encouraging an infant to suck on a pacifier while administering the infant’s tube feeding.

Language

Speech is an important aspect of cognition that develops during the first year. Infants proceed from crying, cooing, and laughing to imitating sounds, comprehending the meaning of simple commands, and repeating words with knowledge of their meaning. By 1 year infants not only recognize their own names but are able to say three to five words and understand almost 100 words (Hockenberry and Wilson, 2011). The nurse promotes language development by encouraging parents to name objects on which their infant’s attention is focused. The nurse also assesses the infant’s language development to identify developmental delays or potential abnormalities.

Psychosocial Changes

During their first year infants begin to differentiate themselves from others as separate beings capable of acting on their own. Initially, infants are unaware of the boundaries of self, but through repeated experiences with the environment they learn where the self ends and the external world begins. As they determine their physical boundaries, they begin to respond to others (Fig. 12-4).

FIG. 12-4 Smiling at and talking to an infant encourage bonding. (From Murray SS, McKinney ES: Foundations of maternal-newborn and women’s health nursing, ed 5, St Louis, 2010, Saunders.)

Two- and 3-month-old infants begin to smile responsively rather than reflexively. Similarly they recognize differences in people when their sensory and cognitive capabilities improve. By 8 months most infants are able to differentiate a stranger from a familiar person and respond differently to the two. Close attachment to their primary caregivers, most often parents, usually occurs by this age. Infants seek out these persons for support and comfort during times of stress. The ability to distinguish self from others allows infants to interact and socialize more within their environments. For example, by 9 months infants play simple social games such as patty-cake and peek-a-boo. More complex interactive games such as hide-and-seek involving objects are possible by age 1.

Erikson (1963) describes the psychosocial developmental crisis for the infant as trust versus mistrust. He explains that the quality of parent-infant interactions determines development of trust or mistrust. The infant learns to trust self, others, and the world through the relationship between the parent and child and the care the child receives (Hockenberry and Wilson, 2011). During infancy the child’s temperament or behavioral style becomes apparent and influences the interactions between parent and child. You can help parents understand their child’s temperament and determine appropriate childrearing practices (see Chapter 11).

Assess the availability and appropriateness of experiences contributing to psychosocial development. Hospitalized infants often have difficulty establishing physical boundaries because of repeated bodily intrusions and painful sensations. Limiting these negative experiences and providing pleasurable sensations are interventions that support early psychosocial development. Extended separations from parents complicate the attachment process and increase the number of caregivers with whom the infant must interact. Ideally the parents provide the majority of care during hospitalization. When parents are not present, either at home or in the hospital, make an attempt to limit the number of different caregivers who have contact with the infant and to follow the parents’ directions for care. These interventions foster the infant’s continuing development of trust.

Play

Play provides opportunities for development of cognitive, social, and motor skills. Much of infant play is exploratory as infants use their senses to observe and examine their own bodies and objects of interest in their surroundings. Adults facilitate infant learning by planning activities that promote the development of milestones and providing toys that are safe for the infant to explore with the mouth and manipulate with the hands such as rattles, wooden blocks, plastic stacking rings, squeezable stuffed animals, and busy boxes.

Health Risks

Injury from motor vehicle accidents, aspiration, suffocation, falls, or poisoning is a major cause of death in children 6 to 12 months old. An understanding of the major developmental accomplishments during this time period allows for injury-prevention planning. As the child achieves gains in motor development and becomes increasingly curious about the environment, constant watchfulness and supervision are critical for injury prevention.

Child Maltreatment

Child maltreatment includes intentional physical abuse or neglect, emotional abuse or neglect, and sexual abuse (Hockenberry and Wilson, 2011). More children suffer from neglect than any other type of maltreatment. Children of any age can suffer from maltreatment, but the youngest are the most vulnerable. In addition, many children suffer from more than one type of maltreatment. No one profile fits a victim of maltreatment, and the signs and symptoms vary (Box 12-1).

A combination of signs and symptoms or a pattern of injury should arouse suspicion. It is important for the health care provider to be aware of certain disease processes and cultural practices. Lack of awareness of normal variants such as Mongolian spots causes the health care provider to assume that there is abuse. Children who are hospitalized for maltreatment have the same developmental needs as other children their age, and the nurse needs to support the child’s relationship with the parents (Hockenberry and Wilson, 2011).

Health Promotion

The quality and quantity of nutrition profoundly influences the infant’s growth and development. Many women have already selected a feeding method well before the infant’s birth, yet others will have questions for the nurse later in the pregnancy. Nurses are in a unique position to help parents select and provide a nutritionally adequate diet for their infant. Understand that factors such as support, culture, role demands, and previous experiences influence feeding methods (Davidson et al., 2008).

Breastfeeding is recommended for infant nutrition because breast milk contains the essential nutrients of protein, fats, carbohydrates, and immunoglobulins that bolster the ability to resist infection. Both the AAP and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services recommend human milk for the first year of life (Hockenberry and Wilson, 2011). However, if breastfeeding is not possible or if the parent does not desire it, an acceptable alternative is iron-fortified commercially prepared formula. Recent advances in the preparation of infant formula include the addition of nucleotides and long-chain fatty acids, which augment immune function and increase brain development. The use of whole cow’s milk, 2% cow’s milk, or alternate milk products before the age of 12 months is not recommended. The composition of whole cow’s milk can cause intestinal bleeding, anemia, and increased incidence of allergies (Hockenberry and Wilson, 2011).

The average 1-month-old infant takes approximately 18 to 21 ounces of breast milk or formula per day. This amount increases slightly during the first 6 months and decreases after introducing solid foods. The amount of formula per feeding and the number of feedings vary among infants. The addition of solid foods is not recommended before the age of 6 months because the gastrointestinal tract is not sufficiently mature to handle these complex nutrients and infants are exposed to food antigens that produce food protein allergies. Developmentally, infants are not ready for solid food before 6 months. The extrusion (protrusion) reflex causes food to be pushed out of the mouth. The introduction of cereals, fruits, vegetables, and meats during the second 6 months of life provides iron and additional sources of vitamins. This becomes especially important when children change from breast milk or formula to whole cow’s milk after the first birthday. Solid foods should be offered one new food at a time. This allows for identification if a food causes an allergic reaction. The use of fruit juices and nonnutritive drinks such as fruit-flavored drinks or soda should be avoided since these do not provide sufficient and appropriate calories during this period (Hockenberry and Wilson, 2011). Infants also tolerate well-cooked table foods by 1 year. The amount and frequency of feedings vary among infants; thus be sure to discuss differing feeding patterns with parents.

Supplementation: The need for dietary vitamin and mineral supplements depends on the infant’s diet. Full-term infants are born with some iron stores. The breastfed infant absorbs adequate iron from breast milk during the first 4 to 6 months of life. After 6 months iron-fortified cereal is generally an adequate supplemental source. Because iron in formula is less readily absorbed than that in breast milk, formula-fed infants need to receive iron-fortified formula throughout the first year.

Adequate concentrations of fluoride to protect against dental caries are not available in human milk; therefore fluoridated water or supplemental fluoride is generally recommended. A recent concern is the use of complementary and alternative medical therapies in children that may or may not be safe. Inquire about the use of such products to help the parent determine whether or not the product is truly safe for the child (Hockenberry and Wilson, 2011).

Immunizations

The widespread use of immunizations has resulted in the dramatic decline of infectious diseases over the past 50 years and therefore is a most important factor in health promotion during childhood. Although most immunizations can be given to persons of any age, it is recommended that the administration of the primary series begin soon after birth and be completed during early childhood. Vaccines are among the safest and most reliable drugs used. Minor side effects sometimes occur; however, serious reactions are rare. Parents need instructions regarding the importance of immunizations and common side effects such as low-grade fever and local tenderness. The recommended schedule for immunizations changes as new vaccines are developed and advances are made in the field of immunology. Stay informed of the current policies and direct parents to the primary caregiver for their child’s schedule. The AAP maintains the most current schedule on their Internet website, http://www.aap.org. Research over the past three decades has clearly indicated that infants experience pain with invasive procedures (e.g., injections) and that nurses need to be aware of measures to reduce or eliminate pain with any health care procedure (see Chapter 31).

Sleep

Sleep patterns vary among infants, with many having their days and nights reversed until 3 to 4 months of age. Thus it is common for infants to sleep during the day. By 6 months most infants are nocturnal and sleep between 9 and 11 hours at night. Total daily sleep averages 15 hours. Most infants take one or two naps a day by the end of the first year. Many parents have concerns regarding their infant’s sleep patterns, especially if there is difficulty such as sleep refusal or frequent waking during the night. Carefully assesses the individual problem before suggesting interventions to address their concern.

Toddler

Toddlerhood ranges from the time children begin to walk independently until they walk and run with ease, which is from 12 to 36 months. The toddler has increasing independence bolstered by greater physical mobility and cognitive abilities. Toddlers are increasingly aware of their abilities to control and are pleased with successful efforts with this new skill. This success leads them to repeated attempts to control their environments. Unsuccessful attempts at control result in negative behavior and temper tantrums. These behaviors are most common when parents stop the initial independent action. Parents cite these as the most problematic behaviors during the toddler years and at times express frustration with trying to set consistent and firm limits while simultaneously encouraging independence. Nurses and parents can deal with the negativism by limiting the opportunities for a “no” answer. For example, the nurse does not ask the toddler, “Do you want to take your medicine now?” Instead, he or she tells the child that it is time to take medicine and offers a choice of water or juice to drink with it.

Physical Changes

The average toddler grows 6.2 cm (2.5 inches) in height and gains approximately 5 to 7 pounds each year (Santrock, 2009). The rapid development of motor skills allows the child to participate in self-care activities such as feeding, dressing, and toileting. In the beginning the toddler walks in an upright position with a broad stance and gait, protuberant abdomen, and arms out to the sides for balance. Soon the child begins to navigate stairs, using a rail or the wall to maintain balance while progressing upward, placing both feet on the same step before continuing. Success provides courage to attempt the upright mode for descending the stairs in the same manner. Locomotion skills soon include running, jumping, standing on one foot for several seconds, and kicking a ball. Most toddlers ride tricycles, climb ladders, and run well by their third birthday.

Fine-motor capabilities move from scribbling spontaneously to drawing circles and crosses accurately. By 3 years the child draws simple stick people and is usually able to stack a tower of small blocks. Children now hold crayons with their fingers rather than with their fists and can imitate vertical and horizontal strokes. They are able to manage feeding themselves with a spoon without rotating it and can drink well from a cup without spilling. Toddlers can turn pages of a book one at a time and can easily turn doorknobs (Hockenberry and Wilson, 2011).

Cognitive Changes

Toddlers increase their ability to remember events and begin to put thoughts into words at about 2 years of age. They recognize that they are separate beings from their mothers, but they are unable to assume the view of another. Toddlers reason based on their own experience of an event. They use symbols to represent objects, places, and persons. Children demonstrate this function as they imitate the behavior of another that they viewed earlier (e.g., pretend to shave like daddy), pretend that one object is another (e.g., use a finger as a gun), and use language to stand for absent objects (e.g., request bottle).

Language

The 18-month-old child uses approximately 10 words. The 24-month-old child has a vocabulary of up to 300 words and is generally able to speak in two-word sentences, although the ability to understand speech is much greater than the number of words acquired (Hockenberry and Wilson, 2011). “Who’s that?” and “What’s that?” are typical questions children ask during this period. Verbal expressions such as “me do it” and “that’s mine” demonstrate the 2-year-old child’s use of pronouns and desire for independence and control. By 36 months the child can use simple sentences, follow some grammatical rules, and learn to use five or six new words each day. Language development may seem to occur in early childhood, but it actually develops further into the later school years and adolescence (Santrock, 2009). Parents can facilitate language development best by talking to their children. Reading to children helps expand their vocabulary, knowledge, and imagination. Television is never used instead of parent-child interaction.

Psychosocial Changes

According to Erikson (1963) a sense of autonomy emerges during toddlerhood. Children strive for independence by using their developing muscles to do everything for themselves and become the master of their bodily functions. Their strong wills are frequently exhibited in negative behavior when caregivers attempt to direct their actions. Temper tantrums result when parental restrictions frustrate toddlers. Parents need to provide toddlers with graded independence, allowing them to do things that do not result in harm to themselves or others. For example, young toddlers who want to learn to hold their own cups often benefit from two-handled cups with spouts and plastic bibs with pockets to collect the milk that spills during the learning process.

Play

Socially toddlers remain strongly attached to their parents and fear separation from them. In their presence they feel safe, and their curiosity is evident in their exploration of the environment. The child continues to engage in solitary play during toddlerhood but also begins to participate in parallel play, which is playing beside rather than with another child. Play expands the child’s cognitive and psychosocial development. It is always important to consider if toys support development of the child, along with the safety of the toy.

Health Risks

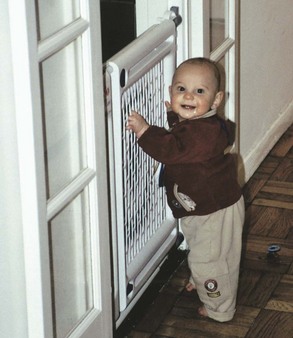

The newly developed locomotion abilities and insatiable curiosity of toddlers make them at risk for injury. Toddlers need close supervision at all times and particularly when in environments that are not childproofed (Fig. 12-5).

FIG. 12-5 Safety precautions should be provided for toddlers. (Courtesy Elaine Polan, RNC, BSN, MS.)

Poisonings occur frequently because children near 2 years of age are interested in placing any object or substance in their mouths to learn about it. The prudent parent removes or locks up all possible poisons, including plants, cleaning materials, and medications. These parental actions create a safer environment for exploratory behavior. Lead poisoning continues to be a serious health hazard in the United States, and children under the age of 6 years are most vulnerable (Hockenberry and Wilson, 2011).

Toddlers’ lack of awareness regarding the danger of water and their newly developed walking skills make drowning a major cause of accidental death in this age-group. Limit setting is extremely important for toddlers’ safety. Motor vehicle accidents account for half of all accidental deaths in children between the ages of 1 and 4 years. Some of these deaths are the result of unrestrained children, and some are attributed to injuries within the car resulting from not using car seat safety guidelines (Hockenberry and Wilson, 2011). Injury prevention is best accomplished by associating various injuries with the attainment of developmental milestones.

Toddlers who become ill and require hospitalization are most stressed by the separation from their parents. Nurses encourage parents to stay with their child as much as possible and actively participate in providing care. Creating an environment that supports parents helps greatly in gaining the cooperation of the toddler. Establishing a trusting relationship with the parents often results in toddler acceptance of treatment.

Health Promotion

Childhood obesity and the associated chronic diseases that result are sources of concern for all health care providers. Children establish lifetime eating habits in early childhood, and there is increased emphasis on food choices. They increasingly meet nutritional needs by eating solid foods. The healthy toddler requires a balanced daily intake of bread and grains, vegetables, fruit, dairy products, and proteins. Because the consumption of more than a quart of milk per day usually decreases the child’s appetite for these essential solid foods and results in inadequate iron intake, advise parents to limit milk intake to 2 to 3 cups per day (Hockenberry and Wilson, 2011). Children are usually not offered low-fat or skim milk until age 2 because they need the fat for satisfactory physical and intellectual growth.

Mealtime has psychosocial and physical significance. If the parents struggle to control toddlers’ dietary intake, problem behavior and conflicts can result. Toddlers often develop “food jags,” or the desire to eat one food repeatedly. Rather than becoming disturbed by this behavior, encourage parents to offer a variety of nutritious foods at meals and to provide only nutritious snacks between meals. Serving finger foods to toddlers allows them to eat by themselves and to satisfy their need for independence and control. Small, reasonable servings allow toddlers to eat all of their meals.

Toilet Training

Increased locomotion skills, the ability to undress, and development of sphincter control allow toilet training if the toddler has developed the necessary language and cognitive abilities. Parents often consult nurses for an assessment of readiness for toilet training. Recognizing the urge to urinate and or defecate is crucial in determining the child’s mental readiness. The toddler must also be motivated to hold on to please the parent rather than letting go to please the self to successfully accomplish toilet training (Hockenberry and Wilson, 2011). The nurse needs to remind parents that patience, consistency, and a nonjudgmental attitude, in addition to the child’s readiness, are essential to successful toilet training.

Preschoolers

The preschool period refers to the years between ages 3 and 5. Children refine the mastery of their bodies and eagerly await the beginning of formal education. Many people consider these the most intriguing years of parenting because children are less negative, more accurately share their thoughts, and more effectively interact and communicate. Physical development occurs at a slower pace than cognitive and psychosocial development.

Physical Changes

Several aspects of physical development continue to stabilize in the preschool years. Children gain about 5 pounds per year; the average weight at 3 years is 32 pounds; at 4 years, 37 pounds; and at 5 years about 41 pounds. Preschoolers grow 6.2 to 7.5 cm ( to 3 inches) per year, double their birth length around 4 years, and stand an average of 107 cm (43 inches) tall by their fifth birthday. The elongation of the legs results in more slender-appearing children. Little difference exists between the sexes, although boys are slightly larger with more muscle and less fatty tissue. Most children are completely toilet trained by the preschool years (Hockenberry and Wilson, 2011).

to 3 inches) per year, double their birth length around 4 years, and stand an average of 107 cm (43 inches) tall by their fifth birthday. The elongation of the legs results in more slender-appearing children. Little difference exists between the sexes, although boys are slightly larger with more muscle and less fatty tissue. Most children are completely toilet trained by the preschool years (Hockenberry and Wilson, 2011).

Large and fine muscle coordination improves. Preschoolers run well, walk up and down steps with ease, and learn to hop. By 5 years they usually skip on alternate feet, jump rope, and begin to skate and swim. Improving fine-motor skills allows intricate manipulations. They learn to copy crosses and squares. Triangles and diamonds are usually mastered between ages 5 and 6. Scribbling and drawing help to develop fine muscle skills and the eye-hand coordination needed for the printing of letters and numbers.

Children need opportunities to learn and practice new physical skills. Nursing care of healthy and ill children includes an assessment of the availability of these opportunities. Although children with acute illnesses benefit from rest and exclusion from usual daily activities, children who have chronic conditions or who have been hospitalized for long periods need ongoing exposure to developmental opportunities. The parents and nurse weave these opportunities into the children’s daily experiences, depending on their abilities, needs, and energy level.

Cognitive Changes

Maturation of the brain continues, with the most rapid growth occurring in the frontal lobe areas, where planning and organizing new activities and maintaining attention to tasks are paramount. Scientific advances in the use of brain-scanning techniques have demonstrated that patterns within the brain change significantly between the ages of 3 to 15 years (Santrock, 2009).

Preschoolers demonstrate their ability to think more complexly by classifying objects according to size or color and by questioning. Children have increased social interaction, as is illustrated by the 5-year-old child who offers a bandage to a child with a cut finger. Children become aware of cause-and-effect relationships, as illustrated by the statement, “The sun sets because people want to go to bed.” Early causal thinking is also evident in preschoolers. For example, if two events are related in time or space, children link them in a causal fashion. For example, the hospitalized child reasons, “I cried last night, and that’s why the nurse gave me the shot.” As children near age 5, they begin to use or learn to use rules to understand causation. They then begin to reason from the general to the particular. This forms the basis for more formal logical thought. The child now reasons, “I get a shot twice a day, and that’s why I got one last night.” Children in this stage also believe that inanimate objects have lifelike qualities and are capable of action, as seen through comments such as, “Trees cry when their branches get broken.”

Preschoolers’ knowledge of the world remains closely linked to concrete (perceived by the senses) experiences. Even their rich fantasy life is grounded in their perception of reality. The mixing of the two aspects often leads to many childhood fears, and adults sometimes misinterpret it as lying when children are actually presenting reality from their perspective. Preschoolers believe that, if a rule is broken, punishment results immediately. During these years they believe that a punishment is automatically connected to an act and do not yet realize that it is socially mediated (Santrock, 2008).

The greatest fear of this age-group appears to be that of bodily harm; this is evident in children’s fear of the dark, animals, thunderstorms, and medical personnel. This fear often interferes with their willingness to allow nursing interventions such as measurement of vital signs. Preschoolers cooperate if they are allowed to help the nurse measure the blood pressure of a parent or to manipulate the nurse’s equipment.

Language

Preschoolers’ vocabularies continue to increase rapidly; and by the age of 6 children have 8000 to 14,000 words that they use to define familiar objects, identify colors, and express their desires and frustrations (Santrock, 2008). Language is more social, and questions expand to “Why?” and “How come?” in the quest for information. Phonetically similar words such as die and dye or wood and would cause confusion in preschool children. Avoid such words when preparing them for procedures and assess comprehension of explanations.

Psychosocial Changes

The world of preschoolers expands beyond the family into the neighborhood where children meet other children and adults. Their curiosity and developing initiative lead to actively exploring the environment, developing new skills, and making new friends. Preschoolers have a surplus of energy that permits them to plan and attempt many activities that are beyond their capabilities such as pouring milk from a gallon container into their cereal bowls. Guilt arises within children when they overstep the limits of their abilities and think that they have not behaved correctly. Children who in anger wished that their sibling were dead experience guilt if that sibling becomes ill. Children need to learn that “wishing” for something to happen does not make it occur. Erikson (1963) recommends that parents help their children strike a healthy balance between initiative and guilt by allowing them to do things on their own while setting firm limits and providing guidance.

Sources of stress for preschoolers can include changes in caregiving arrangements, starting school, the birth of a sibling, parental marital distress, relocation to a new home, or an illness. During these times of stress preschoolers sometimes revert to bed wetting or thumb sucking and want the parents to feed, dress, and hold them. These dependent behaviors are often confusing and embarrassing to parents. They benefit from the nurse’s reassurance that they are the child’s normal coping behaviors. Provide experiences that these children are able to master. Such successes help them return to their prior level of independent functioning. As language skills develop, encourage children to talk about their feelings. Play is also an excellent way for preschoolers to vent frustration or anger and is a socially acceptable way to deal with stress.

Play

The play of preschool children becomes more social after the third birthday as it shifts from parallel to associative play. Children playing together engage in similar if not identical activity; however, there is no division of labor or rigid organization or rules. Most 3-year-old children are able to play with one other child in a cooperative manner in which they make something or play designated roles such as mother and baby. By age 4 children play in groups of two or three, and by 5 years the group has a temporary leader for each activity.

Pretend play allows children to learn to understand others’ points of view, develop skills in solving social problems, and become more creative. Some children have imaginary playmates. These playmates serve many purposes. They are friends when the child is lonely, they accomplish what the child is still attempting, and they experience what the child wants to forget or remember. Imaginary playmates are a sign of health and allow the child to distinguish between reality and fantasy.

Television, videos, electronic games, and computer programs also help support development and the learning of basic skills. However, these should be only one part of the child’s total play activities. The AAP (2011c) advises no more than 1 to 2 hours per day of educational, nonviolent TV programs, which should be supervised by parents or other responsible adults in the home. Limiting TV viewing will provide more time for children to read, engage in physical activity, and socialize with others (Hockenberry and Wilson, 2011).

Health Risks

As fine- and gross-motor skills develop and the child becomes more coordinated with better balance, falls become much less of a problem. Guidelines for injury prevention in the toddler also apply to the preschooler. Children need to learn about safety in the home, and parents need to continue close supervision of activities. Children at this age are great imitators; thus parental example is important. For instance, parental use of a helmet while bicycling sets an appropriate example for the preschooler.

Health Promotion

Little research has explored preschoolers’ perceptions of their own health. Parental beliefs about health, children’s bodily sensations, and their ability to perform usual daily activities help children develop attitudes about their health. Preschoolers are usually quite independent in washing, dressing, and feeding. Alterations in this independence influence their feelings about their own health.

Nutrition

Nutrition requirements for the preschooler vary little from those of the toddler. The average daily intake is 1800 calories. Parents often worry about the amount of food their child is consuming, and this is a relevant concern because of the problem of childhood obesity. However, the quality of the food is more important than quantity in most situations. Preschoolers consume about half of average adult portion sizes. Finicky eating habits are characteristic of the 4-year-old; however, the 5-year-old is more interested in trying new foods.

Sleep

Preschoolers average 12 hours of sleep a night and take infrequent naps. Sleep disturbances are common during these years. Disturbances range from trouble getting to sleep to nightmares to prolonging bedtime with extensive rituals. Frequently children have had an overabundance of activity and stimulation. Helping them to slow down before bedtime usually results in better sleeping habits.

Vision

Vision screening usually begins in the preschool years and needs to occur at regular intervals. One of the most important tests is to determine the presence of nonbinocular vision or strabismus. Early detection and treatment of strabismus are essential by ages 4 to 6 to prevent amblyopia, the resulting blindness from disuse (Hockenberry and Wilson, 2011).

School-Age Children and Adolescents

The developmental changes between ages 6 and 18 are diverse and span all areas of growth and development. Children develop, expand, refine, and synchronize physical, psychosocial, cognitive, and moral skills so the individual is able to become an accepted and productive member of society. The environment in which the individual develops skills also expands and diversifies. Instead of the boundaries of family and close friends, the environment now includes the school, community, and church. With age-specific assessment, you need to review the appropriate developmental expectations for each age-group. You can promote health by helping children and adolescents achieve a necessary developmental balance.

School-Age Children

During these “middle years” of childhood, the foundation for adult roles in work, recreation, and social interaction is laid. In industrialized countries this school-age period begins when the child starts elementary school around the age of 6 years. Puberty, around 12 years of age, signals the end of middle childhood. Children make great developmental strides during these years as they develop competencies in physical, cognitive, and psychosocial skills.

The school or educational experience expands the child’s world and is a transition from a life of relatively free play to one of structured play, learning, and work. The school and home influence growth and development, requiring adjustment by the parents and child. The child learns to cope with rules and expectations presented by the school and peers. Parents have to learn to allow their child to make decisions, accept responsibility, and learn from the experiences of life.

Physical Changes

The rate of growth during these early school years is slow and consistent, a relative calm before the growth spurt of adolescence. The school-age child appears slimmer than the preschooler as a result of changes in fat distribution and thickness (Hockenberry and Wilson, 2011). The average increase in height is 5 cm (2 inches) per year, and weight increases by 4 to 7 pounds per year. Many children double their weight during these middle childhood years, and most girls exceed boys in both height and weight by the end of the school years (Hockenberry and Wilson, 2011).

School-age children become more graceful during the school years because their large muscle coordination improves and their strength doubles. Most children practice the basic gross-motor skills of running, jumping, balancing, throwing, and catching during play, resulting in refinement of neuromuscular function and skills. Individual differences in the rate of mastering skills and ultimate skill achievement become apparent during their participation in many activities and games. Fine-motor skills improve; and, as children gain control over fingers and wrists, they become proficient in a wide range of activities.

Most 6-year-old children are able to hold a pencil adeptly and print letters and words; by age 12 the child is able to make detailed drawings and write sentences in script. Painting, drawing, playing computer games, and modeling allow children to practice and improve newly refined skills. The improved fine-motor capabilities of youngsters in middle childhood allow them to become very independent in bathing, dressing, and taking care of other personal needs. They develop strong personal preferences in the way these needs are met. Illness and hospitalization threaten children’s control in these areas. Therefore it is important to allow them to participate in care and maintain as much independence as possible. Children whose care demands restriction of fluids cannot be allowed to decide the amount of fluids they will drink in 24 hours, but they can help decide the type of fluids and help keep a record of their intake.

Assessment of neurological development is often based on fine-motor coordination. Fine-motor coordination is critical to success in the typical American school, where children have to hold pencils and crayons and use scissors and rulers. The opportunity to practice these skills through schoolwork and play is essential to learning coordinated, complex behaviors.

As skeletal growth progresses, body appearance and posture change. Earlier the child’s posture was stoop shouldered, with slight lordosis and a prominent abdomen. The posture of a school-age child is more erect. It is essential to evaluate children, especially girls after the age of 12 years, for scoliosis, the lateral curvature of the spine.

Eye shape alters because of skeletal growth. This improves visual acuity, and normal adult 20/20 vision is achievable. Screening for vision and hearing problems is easier, and results are more reliable because school-age children more fully understand and cooperate with the test directions. The school nurse typically assesses the growth, visual, and auditory status of school-age children and refers those with possible deviations to a health care provider such as their family practitioner or pediatrician.

Cognitive Changes

Cognitive changes provide the school-age child with the ability to think in a logical manner about the here and now and to understand the relationship between things and ideas. They are now able to use their developed thinking abilities to experience events without having to act them out (Hockenberry and Wilson, 2011). Their thoughts are no longer dominated by their perceptions; thus their ability to understand the world greatly expands.

School-age children have the ability to concentrate on more than one aspect of a situation. They begin to understand that others do not always see things as they do and even begin to understand another viewpoint. They now have the ability to recognize that the amount or quantity of a substance remains the same even when its shape or appearance changes. For instance, two balls of clay of equal size remain the same amount of clay even when one is flattened and the other remains in the shape of a ball.

The young child is able to separate objects into groups according to shape or color, whereas the school-age child understands that the same element can exist in two classes at the same time. By 7 or 8 years these children develop the ability to place objects in order according to their increasing or decreasing size (Hockenberry and Wilson, 2011; Santrock, 2009). School-age children frequently have collections such as baseball cards or stuffed animals that demonstrate this new cognitive skill.

Language Development

Language growth is so rapid during middle childhood that it is no longer possible to match age with language achievements. Children improve their use of language and expand their structural knowledge. They become more aware of the rules of syntax, the rules for linking words into phrases and sentences. They also identify generalizations and exceptions to rules. They accept language as a means for representing the world in a subjective manner and realize that words have arbitrary rather than absolute meanings. Children begin to think about language, which enables them to appreciate jokes and riddles. They are not as likely to use a literal interpretation of a word; rather they reason about its meaning within a context (Hockenberry and Wilson, 2011).

Psychosocial Changes

Erikson (1963) identifies the developmental task for school-age children as industry versus inferiority. During this time children strive to acquire competence and skills necessary for them to function as adults. School-age children who are positively recognized for success feel a sense of worth. Those faced with failure often feel a sense of mediocrity or unworthiness, which sometimes results in withdrawal from school and peers.

School-age children begin to define themselves on the basis of their internal characteristics more than external characteristics. They begin to define their self-concept and develop self-esteem, an overall self-evaluation. Interaction with peers allows them to define their own accomplishments in relation to others as they work to develop a positive self-image (Santrock, 2008).

Peer Relationships

Group and personal achievements become important to the school-age child. Success is important in physical and cognitive activities. Play involves peers and the pursuit of group goals. Although solitary activities are not eliminated, group play overshadows them. Learning to contribute, collaborate, and work cooperatively toward a common goal becomes a measure of success (Fig. 12-6).

FIG. 12-6 School-age children gain a sense of achievement working and playing with peers. (From Hockenberry MJ, Wilson D: Wong’s nursing care of infants and children, ed 9, St Louis, 2011, Mosby.)

The school-age child prefers same-sex peers to opposite-sex peers. In general, girls and boys view the opposite sex negatively. Peer influence becomes quite diverse during this stage of development. Clubs and peer groups become prominent. School-age children often develop “best friends” with whom they share secrets and with whom they look forward to interacting on a daily basis. Group identity increases as the school-age child approaches adolescence.

Sexual Identity

Freud described middle childhood as the latency period because he believed that children of this period had little interest in their sexuality. Today many researchers believe that school-age children have a great deal of curiosity about their sexuality. Some experiment, but this play is usually transitory. Children’s curiosity about adult magazines or meanings of sexually explicit words is also an example of their sexual interest. This is the time for children to have exposure to sex education, including sexual maturation, reproduction, and relationships (Hockenberry and Wilson, 2011).

Stress

Today’s children experience more stress than children in earlier generations. Stress comes from parental expectations; peer expectations; the school environment; or violence in the family, school, or community. Some school-age children care for themselves before or after school without adult supervision. Latchkey children sometimes feel increased stress and are at greater risk for injury and unsafe behaviors (Hockenberry and Wilson, 2011). The nurse helps the child cope with stress by helping the parents and child to identify potential stressors and designing interventions to minimize stress and the child’s stress response. Deep-breathing techniques, positive imagery, and progressive relaxation of muscle groups are interventions that most children can learn (see Chapter 32). Include the parent, child, and teacher in the intervention for maximal success.

Health Risks

Accidents and injuries are a major health problem affecting school-age children. They now have more exposure to various environments and less supervision, but their developed cognitive and motor skills make them less likely to suffer from unintentional injury. Some school-age children are risk takers and attempt activities that are beyond their abilities (Hockenberry and Wilson, 2007). Motor vehicle injuries as a passenger or pedestrian and bicycle injuries are among the most common in this age-group.

Infections account for the majority of all childhood illnesses; respiratory infections are the most prevalent. The common cold remains the chief illness of childhood. Certain groups of children are more prone to disease and disability, often as a result of barriers to health care. Poverty and the prevalence of illness are highly correlated. Access to care is often very limited, and health promotion and preventive health measures are minimal.

Health Promotion

During the school-age years identity and self-concept become stronger and more individualized. Perception of wellness is based on readily observable facts such as presence or absence of illness and adequacy of eating or sleeping. Functional ability is the standard by which personal health and the health of others are judged. Six-year-olds are aware of their body and modest and sensitive about being exposed. Nurses need to provide for privacy and offer explanations of common procedures.

Health Education

The school-age period is crucial for the acquisition of behaviors and health practices for a healthy adult life. Because cognition is advancing during the period, effective health education must be developmentally appropriate. Promotion of good health practices is a nursing responsibility. Programs directed at health education are frequently organized and conducted in the school. Effective health education teaches children about their bodies and how the choices they make impact their health (Hockenberry and Wilson, 2011). During these programs focus on the development of behaviors that positively affect children’s health status.

Health Maintenance

Parents need to recognize the importance of annual health maintenance visits for immunizations, screenings, and dental care. When their school-age child reaches 10 years of age, parents need to begin discussions in preparation for upcoming pubertal changes. Topics include introductory information regarding menstruation, sexual intercourse, reproduction, and sexually transmitted infections (STIs). Human papilloma virus (HPV) is a widespread virus that will infect over 50% of males and females in their lifetime (AAP, 2010). For many individuals HPV clears spontaneously, but for others it can cause significant consequences. Females can develop cervical, vaginal, and vulvar cancers and genital warts; and males can develop genital warts. Since it is not possible to determine who or who will not develop disease from the virus, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2010a), along with the AAP, recommends routine HPV vaccination for girls ages 11 to 12 and for young women ages 13 through 26 who have not already been vaccinated. It is further recommended that HPV vaccine be given to boys and young men ages 9 to 26 years.

Safety

Because accidents such as fires and car and bicycle crashes are the leading cause of death and injury in the school-age period, safety is a priority health teaching consideration. Nurses contribute to the general health of children by educating them about safety measures to prevent accidents. At this age encourage children to take responsibility for their own safety.

Nutrition

Growth often slows during the school-age period as compared to infancy and adolescence. School-age children are developing eating patterns that are independent of parental supervision. The availability of snacks and fast-food restaurants makes it increasingly difficult for children to make healthy choices. The prevalence of obesity among children 6 to 11 years of age increased from 6.5% in 1980 to 19.6% in 2008 (CDC, 2010b). Childhood obesity has become a prominent health problem, resulting in increased risk for hypertension, diabetes, coronary heart disease, fatty liver disease, pulmonary complications such as sleep apnea, musculoskeletal problems, dyslipidemia, and potential for psychological problems. Studies have found that overweight children are teased more often, less likely to be chosen as a friend, and more likely to be thought of as lazy and sloppy by their peers (Hockenberry and Wilson, 2011). Nurses contribute to meeting national policy goals by promoting healthy lifestyle habits, including nutrition. School-age children need to participate in educational programs that enable them to plan, select, and prepare healthy meals and snacks. Children need adequate caloric intake for growth throughout childhood accompanied by activity for continued gross-motor development.

Adolescents

Adolescence is the period during which the individual makes the transition from childhood to adulthood, usually between ages 13 and 20 years. The term adolescent usually refers to psychological maturation of the individual, whereas puberty refers to the point at which reproduction becomes possible. The hormonal changes of puberty result in changes in the appearance of the young person, and cognitive development results in the ability to hypothesize and deal with abstractions. Adjustments and adaptations are necessary to cope with these simultaneous changes and the attempt to establish a mature sense of identity. In the past many referred to adolescence as a stormy and stressful period filled with inner turmoil, but today it is recognized that most teenagers successfully meet the challenges of this period.

The nurse’s understanding of development provides a unique perspective for helping teenagers and parents anticipate and cope with the stresses of adolescence. Nursing activities, particularly education, promote healthy development. These activities occur in a variety of settings, and you can direct them at the adolescent, parents, or both. For example, the nurse conducts seminars in a high school to provide practical suggestions for solving problems of concern to a large group of students such as treating acne or making responsible decisions about drugs or alcohol use. Similarly a group education program for parents about how to cope with teenagers would promote parental understanding of adolescent development.

Physical Changes

Physical changes occur rapidly in adolescence. Sexual maturation occurs with the development of primary and secondary sexual characteristics. The four main focuses of the physical changes are:

1. Increased growth rate of skeleton, muscle, and viscera.

2. Sex-specific changes such as changes in shoulder and hip width.

3. Alteration in distribution of muscle and fat.

4. Development of the reproductive system and secondary sex characteristics.

Wide variation exists in the timing of physical changes associated with puberty between sexes and within the same sex. Girls tend to begin their physical changes approximately 2 years earlier than boys, usually between the ages of 11 to 14 years (Santrock, 2009). The rates of height and weight gain are usually proportional, and the sequence of pubertal growth changes is the same in most individuals.

Hormonal changes within the body create change when the hypothalamus begins to produce gonadotropin-releasing hormones that stimulate ovarian cells to produce estrogen and testicular cells to produce testosterone. These hormones contribute to the development of secondary sex characteristics such as hair growth and voice changes and play an essential role in reproduction. The changing concentrations of these hormones are also linked to acne and body odor. Understanding these hormonal changes enables you to reassure adolescents and educate them about body care needs.

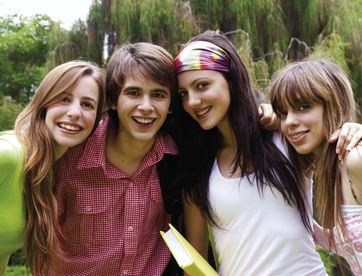

Boys who mature early are more poised, relaxed, good-natured, skilled in athletic activities, and likely to be school leaders than boys who mature late. In contrast, girls who mature early are less satisfied with their figures by late adolescence. The reason for this is that early-maturing girls tend to be shorter and somewhat heavier than late-maturing girls, who tend to be taller and thinner (Santrock, 2008). Being like peers is extremely important for adolescents (Fig. 12-7). Any deviation in the timing of the physical changes is extremely difficult for adolescents to accept. Therefore provide emotional support for those undergoing early or delayed puberty. Even adolescents whose physical changes are occurring at the normal times seek confirmation of and reassurance about their normalcy.

Height and weight increases usually occur during the prepubertal growth spurt, which peaks in girls at about 12 years and in boys at about 14 years. Girls’ height increases 5 to 20 cm (2 to 8 inches), and weight increases by 15 to 55 pounds. Boys’ height increases approximately 10 to 30 cm (4 to 12 inches), and weight increases by 15 to 65 pounds. Individuals gain the final 20% to 25% of their height and 50% of their weight during this time period (Hockenberry and Wilson, 2011).

Girls attain 90% to 95% of their adult height by menarche (the onset of menstruation) and reach their full height by 16 to 17 years of age, whereas boys continue to grow taller until 18 to 20 years of age. Fat is redistributed into adult proportions as height and weight increase, and gradually the adolescent torso takes on an adult appearance. Although individual and sex differences exist, growth follows a similar pattern for both sexes. Personal growth curves help the nurse assess physical development. However, the individual’s sustained progression along the curve is more important than a comparison to the norm.

Cognitive Changes