Developmental Theories

• Discuss factors influencing growth and development.

• Describe biophysical developmental theories.

• Describe and compare the psychoanalytical/psychosocial theories proposed by Freud and Erikson.

• Describe Piaget’s theory of cognitive development.

• Apply developmental theories when planning interventions in the care of patients throughout the life span.

• Discuss nursing implications for the application of developmental principles to patient care.

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Potter/fundamentals/

Understanding normal growth and development helps nurses predict, prevent, and detect deviations from patients’ own expected patterns. Growth encompasses the physical changes that occur from the prenatal period through older adulthood and also demonstrates both advancement and deterioration. Young children grow more quickly than older children, and by adulthood growth in height ceases. In late adulthood there is a loss of both muscle and bone, which may cause a decrease in height in some people (Santrock, 2009). Development refers to the biological, cognitive, and socioemotional changes that begin at conception and continue throughout a lifetime. Development is dynamic and includes progression. However, in some disease processes development is delayed or regresses. For example, older adults demonstrate cognitive development resulting in wisdom as they incorporate life experiences into decision making, but they do not perform as well as young adults when speed is required for information processing (Santrock, 2008).

Individuals have unique patterns of growth and development. The ability to progress through each developmental phase influences the overall health of the individual. The success or failure experienced within a phase affects the ability to complete subsequent phases. If individuals experience repeated developmental failures, inadequacies sometimes result. However, when the individual experiences repeated successes, health is promoted. For example, a child who does not walk by 20 months may demonstrate delayed gross motor ability that slows exploration and manipulation of the environment. In contrast, a child who walks by 10 months is able to explore and find stimulation in the environment.

Today nurses need to adopt a life span perspective of human development that takes into account all developmental stages of life. Traditionally development focused on childhood, but a comprehensive view of development also includes the changes that occur during the adult years. An understanding of growth and development throughout the life span assists in planning questions for health screening and health history and in health teaching for patients of all ages.

Developmental Theories

Developmental theories provide a framework for examining, describing, and appreciating human development. For example, knowledge of Erikson’s psychosocial theory of development helps caregivers understand the importance of supporting the development of basic trust in the infancy stage. Trust establishes the foundation for all future relationships. Developmental theories are also important in helping nurses assess and treat a person’s response to an illness. Understanding the specific task or need of each developmental stage guides caregivers in planning appropriate individualized care for patients. Specific developmental theories that define the aging process for adults are discussed in Chapters 13 and 14.

Human development is a dynamic and complex process that cannot be explained by only one theory. This chapter presents biophysical, psychoanalytical/psychosocial, cognitive, and moral developmental theories. Chapters 25 and 35 cover the areas of learning theory for patient teaching and spiritual development.

Biophysical Developmental Theories

Biophysical development is how our physical bodies grow and change. Health care providers are able to quantify and compare the changes that occur as a newborn infant grows into adulthood against established norms. How does the physical body age? What are the triggers that move the body from the physical characteristics of childhood, through adolescence, to the physical changes of adulthood?

Gesell’s Theory of Development

Fundamental to Gesell’s theory of development is that each child’s pattern of growth is unique and this pattern is directed by gene activity (Gesell, 1948). Gesell found the pattern of maturation follows a fixed developmental sequence in humans. Sequential development is evident in fetuses, in which there is a specified order of organ system development. Today we know that growth in humans is both cephalocaudal and proximodistal. The cephalocaudal pattern describes the sequence in which growth is fastest at the top (head and then down); proximodistal growth starts at the center of the body and moves toward the extremities.

Genes direct the sequence of development; but environmental factors also influence development, resulting in developmental changes. For example, genes may direct the growth rate for an individual, but that growth is only maximized if environmental conditions are adequate. Poor nutrition or chronic disease often affects the growth rate and results in smaller stature, regardless of the genetic blueprint. However, adequate nutrition and the absence of disease cannot result in stature beyond that determined by heredity.

Psychoanalytical/Psychosocial Theory

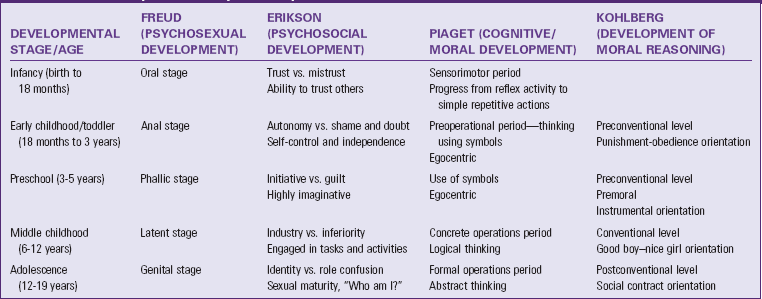

Theories of psychoanalytical/psychosocial development describe human development from the perspectives of personality, thinking, and behavior (Table 11-1). Psychoanalytical theory explains development as primarily unconscious and influenced by emotion. Psychoanalytical theorists maintain that these unconscious drives influence development through universal stages experienced by all individuals (Berger, 2007).

Sigmund Freud

Freud’s psychoanalytical model of personality development states that individuals go through five stages of psychosexual development and that each stage is characterized by sexual pleasure in parts of the body: the mouth, the anus, and the genitals. Freud believed that adult personality is the result of how an individual resolved conflicts between these sources of pleasure and the mandates of reality (Berger, 2007; Santrock, 2009).

Stage 1: Oral (Birth to 12 to 18 Months): Initially sucking and oral satisfaction are not only vital to life but also extremely pleasurable in their own rights. Late in this stage the infant begins to realize that the mother/parent is something separate from self. Disruption in the physical or emotional availability of the parent (e.g., inadequate bonding or chronic illness) could affect an infant’s development.

Stage 2: Anal (12 to 18 Months to 3 Years): The focus of pleasure changes to the anal zone. Children become increasingly aware of the pleasurable sensations of this body region with interest in the products of their effort. Through the toilet-training process the child delays gratification to meet parental and societal expectations.

Stage 3: Phallic or Oedipal (3 to 6 Years): The genital organs are the focus of pleasure during this stage. The boy becomes interested in the penis; the girl becomes aware of the absence of the penis, known as penis envy. This is a time of exploration and imagination as the child fantasizes about the parent of the opposite sex as his or her first love interest, known as the Oedipus or Electra complex. By the end of this stage the child attempts to reduce this conflict by identifying with the parent of the same sex as a way to win recognition and acceptance.

Stage 4: Latency (6 to 12 Years): In this stage Freud believed that sexual urges from the earlier oedipal stage are repressed and channeled into productive activities that are socially acceptable. Within the educational and social worlds of the child, there is much to learn and accomplish.

Stage 5: Genital (Puberty Through Adulthood): In this final stage sexual urges reawaken and are directed to an individual outside the family circle. Unresolved prior conflicts surface during adolescence. Once the individual resolves conflicts, he or she is then capable of having a mature adult sexual relationship.

Freud believed that the components of the human personality develop in stages and regulate behavior. These components are the id, the ego, and the superego. The id (i.e., basic instinctual impulses driven to achieve pleasure) is the most primitive part of the personality and originates in the infant. The ego represents the reality component, mediating conflicts between the environment and the forces of the id. The ego helps people judge reality accurately, regulate impulses, and make good decisions. The third component, the superego, performs regulating, restraining, and prohibiting actions. Often referred to as the conscience, the superego is influenced by the standards of outside social forces (e.g., parent or teacher).

Some of Freud’s critics contend that he based his analysis of personality development on biological determinants and ignored the influence of culture and experience. Other critics think that Freud’s basic assumptions such as the Oedipus complex are not applicable across different cultures. Psychoanalysts today believe that the role of conscious thought is much greater than Freud imagined (Santrock, 2008).

Erik Erikson

Freud had a strong influence on his psychoanalytical followers, including Erik Erikson (1902-1994), who constructed a theory of development that differed from Freud’s in two major views. Erikson maintained that development occurred throughout the life span and that it focused on psychosocial stages rather than psychosexual stages.

According to Erikson’s theory of psychosocial development, individuals need to accomplish a particular task before successfully mastering the stage and progressing to the next one. Each task is framed with opposing conflicts, and tasks once mastered are challenged and tested again during new situations or at times of conflict (Hockenberry and Wilson, 2011). Erikson’s eight stages of life are described here.

Trust versus Mistrust (Birth to 1 Year): Establishing a basic sense of trust is essential for the development of a healthy personality. The infant’s successful resolution of this stage requires a consistent caregiver who is available to meet his needs. From this basic trust in parents, the infant is able to trust in himself, in others, and in the world (Hockenberry and Wilson, 2011). The formation of trust results in faith and optimism. A nurse’s use of anticipatory guidance helps parents cope with the hospitalization of an infant and the infant’s behaviors when discharged to home.

Autonomy versus Sense of Shame and Doubt (1 to 3 Years): By this stage a growing child is more accomplished in some basic self-care activities, including walking, feeding, and toileting. This newfound independence is the result of maturation and imitation. The toddler develops his or her autonomy by making choices. Choices typical for the toddler age-group include activities related to relationships, desires, and playthings. There is also opportunity to learn that parents and society have expectations about these choices. Limiting choices and/or enacting harsh punishment leads to feelings of shame and doubt. The toddler who successfully masters this stage achieves self-control and willpower. The nurse models empathetic guidance that offers support for and understanding of the challenges of this stage.

Initiative versus Guilt (3 to 6 Years): Children like to pretend and try out new roles. Fantasy and imagination allow them to further explore their environment. Also at this time they are developing their superego, or conscience. Conflicts often occur between the child’s desire to explore and the limits placed on his or her behavior. These conflicts sometimes lead to feelings of frustration and guilt. Guilt also occurs if the caregiver’s responses are too harsh. Preschoolers are learning to maintain a sense of initiative without imposing on the freedoms of others. Successful resolution of this stage results in direction and purpose. Teaching the child impulse control and cooperative behaviors helps the family avoid the risks of altered growth and development.

Industry versus Inferiority (6 to 11 Years): School-age children are eager to apply themselves to learning socially productive skills and tools. They learn to work and play with their peers. They thrive on their accomplishments and praise. Without proper support for learning new skills or if skills are too difficult, they develop a sense of inadequacy and inferiority. Children at this age need to be able to experience real achievement to develop a sense of competency. Erikson believed that the adult’s attitudes toward work are traced to successful achievement of this task (Erikson, 1963). During hospitalization it is important for the school-age child to understand the routines and participate as actively as possible in his or her treatment. For example, some children enjoy keeping a record of their intake and output.

Identity versus Role Confusion (Puberty): Dramatic physiological changes associated with sexual maturation mark this stage. There is a marked preoccupation with appearance and body image. This stage, in which identity development begins with the goal of achieving some perspective or direction, answers the question, “Who am I?” Acquiring a sense of identity is essential for making adult decisions such as choice of a vocation or marriage partner. Each adolescent moves in his or her unique way into society as an interdependent member. There are also new social demands, opportunities, and conflicts that relate to the emergent identity and separation from family. Erikson held that successful mastery of this stage resulted in devotion and fidelity to others and to their own ideals (Hockenberry and Wilson, 2011). The nurse provides education and anticipatory guidance for the parent about the changes and challenges to the adolescent. Nurses also help hospitalized adolescents deal with their illness by giving them enough information to allow them to make decisions about their treatment plan.

Intimacy versus Isolation (Young Adult): Young adults, having developed a sense of identity, deepen their capacity to love others and care for them. They search for meaningful friendships and an intimate relationship with another person. Erikson portrayed intimacy as finding the self and then losing the self in another (Santrock, 2008). If the young adult is not able to establish companionship and intimacy, isolation results because he or she fears rejection and disappointment (Berger, 2007). Nurses must understand that hospitalization increases a young adults’ need for intimacy; thus young adults benefit from the support of their partner or significant other during this time.

Generativity versus Self-Absorption and Stagnation (Middle Age): Following the development of an intimate relationship, the adult focuses on supporting future generations. The ability to expand one’s personal and social involvement is critical to this stage of development. Middle-age adults achieve success in this stage by contributing to future generations through parenthood, teaching, and community involvement. Achieving generativity results in caring for others as a basic strength. Inability to play a role in the development of the next generation results in stagnation (Santrock, 2008). Nurses assist physically ill adults in choosing creative ways to foster social development. Middle-age persons often find a sense of fulfillment by volunteering in a local school, hospital, or church.

Integrity versus Despair (Old Age): Many older adults review their lives with a sense of satisfaction, even with their inevitable mistakes. Others see themselves as failures, with their lives marked by despair and regret. Older adults often engage in a retrospective appraisal of their lives. They interpret their lives as a meaningful whole or experience regret because of goals not achieved (Berger, 2007). Because the aging process creates physical and social losses, some adults also suffer loss of status and function (e.g., through retirement or illness). These external struggles are also met with internal struggles such as the search for meaning in life. Meeting these challenges creates the potential for growth and the basic strength of wisdom (Fig. 11-1).

Nurses are in positions of influence within their communities to help people feel valued, appreciated, and needed. Erikson stated, “Healthy children will not fear life, if their parents have integrity enough not to fear death” (Erikson, 1963). Although Erikson believed that problems in adult life resulted from unsuccessful resolution of earlier stages, his emphasis on family relationships and culture offered a broad, life-span view of development. As a nurse, you will use this knowledge of development as you deliver care in any health care setting.

Theories Related to Temperament

Temperament is a behavioral style that affects an individual’s emotional interactions with others (Santrock, 2008). Personality and temperament are often closely linked, and research shows that individuals possess some enduring characteristics into adulthood. The individual differences that children display in responding to their environment significantly influence the way others respond to them and their needs. Knowledge of temperament helps parents better understand their child (Hockenberry and Wilson, 2011).

Psychiatrists Stella Chess (1914-2007) and Alexander Thomas (1914-2003) conducted a 20-year longitudinal study that identified three basic classes of temperament:

• The easy child—Easygoing and even-tempered. This child is regular and predictable in his or her habits. An easy child is open and adaptable to change and displays a mild-to– moderately intense mood that is typically positive.

• The difficult child—Highly active, irritable, and irregular in habits. Negative withdrawal toward others is typical, and the child requires a more structured environment. A difficult child adapts slowly to new routines, people, or situations. Mood expressions are usually intense and primarily negative.

• The slow-to–warm up child—Typically reacts negatively and with mild intensity to new stimuli. The child adapts slowly with repeated contact unless pressured and responds with mild but passive resistance to novelty or changes in routine.

Research on temperament and its stability has continued, with an emphasis on the individual’s ability to make thoughtful decisions about behavior in demanding situations. Knowledge of temperament and how it impacts the parent-child relationship is critical when providing anticipatory guidance for parents. With the birth of a second child, most parents find that the strategies that worked well with the first child no longer work at all. The nurse individualizes counseling to greatly improve the quality of interactions between parents and children (Hockenberry and Wilson, 2011).

Perspectives on Adult Development

Early study of development focused only on childhood because scholars throughout history regarded the aging process as one of inevitable and irreversible decline. However, we now know that, although the changes come more slowly, people continue to develop new abilities and adapt to shifting environments. The life span perspective suggests that understanding adult development requires multiple viewpoints. Two of the ways that researchers have studied adult development are through the stage-crisis view and the life span approach. The most well-known stage theory is the one developed by Erik Erikson that was discussed earlier. Another stage theory that contributed to understanding development throughout the life span was provided through the work of Robert Havinghurst.

Stage-Crisis Theory

Physicist, educator, and aging expert Robert Havinghurst (1900-1991) conducted extensive research and developed a theory of human development based on developmental tasks. Havinghurst’s theory incorporates three primary sources for developmental tasks: tasks that surface because of physical maturation, tasks that evolve from personal values, and tasks that are a result of pressures from society. As with Erikson, Havinghurst believed that successful resolution of the developmental task was essential to successful progression throughout life. He identified six stages and six-to-ten developmental tasks for each stage: infancy and early childhood (birth to age 6), middle childhood (6 to 12 years), adolescence (13 to 18 years), early adulthood (19 to 30 years), middle adulthood (30 to 60 years), and late adulthood (60 and over). Havinghurst believed that the number of tasks differs in each age level for individuals because of the interrelationship among biology, society, and personal values. In later years Havinghurst turned his focus to the study of aging. In response to the view that older adults should gradually withdraw from society, Havinghurst proposed an activity theory, which states that continuing an active, involved lifestyle results in greater satisfaction and well-being in aging (see Chapter 14).

Life Span Approach

The contemporary life-events approach takes into consideration the variations that occur for each individual. This view considers the individual’s personal circumstances (health and family support), how the person views and adjusts to changes, and the current social and historical context in which the individual is living (Santrock, 2009). Contemporary theorists such as Paul Baltes (1939-2006) and Laura Carstensen (1954- ) have continued to study development in adulthood and proposed theories that support the need for a balance between the pursuit of active engagement and selection of activities that support personal enjoyment for successful aging. The selective optimization with compensation theory (Baltes, Freund, and Li, 2005) is based on the concept that, as individuals age, they are able to compensate for some decreases in physical or cognitive performance by developing new approaches. They are also able to optimize performance in some areas through continued practice or the use of new technology. Carstensen, Isaacowitz, and Charles (1999) developed the socioemotional selectivity theory suggesting that, as people age, they become more selective and invest their energies in meaningful relationships, goals, and activities. Current research on successful aging is much more consistent with a life span approach that emphasizes age-related goals that are relationship and socially oriented to support continued well-being (Reichstadt et al., 2010).

Cognitive Developmental Theory

Psychoanalytical/psychosocial theories focus on an individual’s unconscious thought and emotions; cognitive theories stress how people learn to think and make sense of their world. As with personality development, cognitive theorists have explored both childhood and adulthood. Some of the theories highlight qualitative changes in thinking; others expand to include social, cultural, and behavioral dimensions.

Jean Piaget

Jean Piaget (1896-1980) was most interested in the development of children’s intellectual organization: how they think, reason, and perceive the world. Piaget’s theory of cognitive development includes four periods that are related to age and demonstrate specific categories of knowing and understanding. He built his theory on years of observing children as they explored, manipulated, and tried to make sense out of the world in which they lived. Piaget believed that individuals move from one stage to the other seeking cognitive equilibrium or a state of mental balance (Santrock, 2009). Within each of these primary periods of cognitive development are specific stages (see Table 11-1).

Period I: Sensorimotor (Birth to 2 Years): Infants develop a schema or action pattern for dealing with the environment. These schemas include hitting, looking, grasping, or kicking. Schemas become self-initiated activities (e.g., the infant learning that sucking achieves a pleasing result generalizes the action to suck fingers, blanket, or clothing). Successful achievement leads to greater exploration. During this stage the child learns about himself and his environment through motor and reflex actions. He or she learns that he or she is separate from the environment and that aspects of the environment (e.g., parents or favorite toy) continue to exist even though they cannot always be seen. Piaget termed this understanding that objects continue to exist even when they cannot be seen, heard, or touched object permanence and considered it one of the child’s most important accomplishments.

Period II: Preoperational (2 to 7 Years): During this time children learn to think with the use of symbols and mental images. They exhibit “egocentrism” in that they see objects and persons from only one point of view, their own. They believe that everyone experiences the world exactly as they do. Early in this stage children demonstrate “animism” in which they personify objects. They believe that inanimate objects have lifelike thought, wishes, and feelings. Their thinking is influenced greatly by fantasy and magical thinking. Children at this stage have difficulty conceptualizing time. Play becomes a primary means by which they foster their cognitive development and learn about the world (Fig. 11-2). Nursing interventions during this period recognize the use of play as the way the child understands the events taking place.

Period III: Concrete Operations (7 to 11 Years): Children now are able to perform mental operations. For example, the child thinks about an action that before was performed physically. Children are now able to describe a process without actually doing it. At this time they are able to coordinate two concrete perspectives in social and scientific thinking so they are able to appreciate the difference between their perspective and that of a friend. Reversibility is one of the primary characteristics of concrete operational thought. Children can now mentally picture a series of steps and reverse the steps to get back to the starting point. The ability to mentally classify objects according to their quantitative dimensions, known as seriation, is achieved. They are able to correctly order or sort objects by length, weight, or other characteristics. Another major accomplishment of this stage is conservation, or the ability to see objects or quantities as remaining the same despite a change in their physical appearance (Santrock, 2009).

Period IV: Formal Operations (11 Years to Adulthood): The transition from concrete to formal operational thinking occurs in stages during which there is a prevalence of egocentric thought. This egocentricity leads adolescents to demonstrate feelings and behaviors characterized by self-consciousness, a belief that their actions and appearance are constantly being scrutinized (an “imaginary audience”), that their thoughts and feelings are unique (the “personal fable”), and that they are invulnerable (Santrock, 2008). These feelings of invulnerability frequently lead to risk-taking behaviors, especially in early adolescence. As adolescents share experiences with peers, they learn that many of their thoughts and feelings are shared by almost everyone, helping them to know that they are not so different. As adolescents mature, their thinking moves to abstract and theoretical subjects. They have the capacity to reason with respect to possibilities. For Piaget this stage marked the end of cognitive development.

Piaget’s work has been challenged over the years as researchers have continued to study cognitive development. For example, some aspects of objective performance emerge earlier than Piaget believed, and other cognitive abilities can surface later than he predicted. We now know that many adults may not become formal operational thinkers and others have cognitive development that goes beyond the stages that Piaget proposed (Santrock, 2009). Assessment of cognitive ability becomes critical as the nurse engages in health care teaching for patients and families.

Research in Adult Cognitive Development

Research into cognitive development in adulthood began in the 1970s and continues today. Research supports that adults do not always arrive at one answer to a problem but frequently accept several possible solutions. Adults also incorporate emotions, logic, practicality, and flexibility when making decisions. On the basis of these observations, developmentalists proposed a fifth stage of cognitive development termed postformal thought. Within this stage adults demonstrate the ability to recognize that answers vary from situation to situation and that solutions need to be sensible.

One of the earliest to develop a theory of adult cognition was William Perry (1913-1998), who studied college students and found that continued cognitive development involved increasing cognitive flexibility. As adolescents were able to move from a position of accepting only one answer to realizing that alternative explanations could be right, depending on one’s perspective, there was a significant cognitive change. Adults change how they use knowledge, and the emphasis shifts from attaining knowledge or skills to using knowledge for goal achievement (Box 11-1).

Moral Developmental Theory

Moral development refers to the changes in a person’s thoughts, emotions, and behaviors that influence beliefs about what is right or wrong. It encompasses both interpersonal and intrapersonal dimensions as it governs how we interact with others (Santrock, 2009). Although various psychosocial and cognitive theorists address moral development within their respective theories, the theories of Piaget and Kohlberg are more widely known (see Table 11-1).

Lawrence Kohlberg’s Theory of Moral Development

Kohlberg’s theory of moral development expands on Piaget’s cognitive theory. Kohlberg interviewed children, adolescents, and eventually adults and found that moral reasoning develops in stages. From an examination of responses to a series of moral dilemmas, he identified six stages of moral development under three levels (Kohlberg, 1981).

Level I: Preconventional Reasoning: This is the premoral level, in which there is limited cognitive thinking and the individual’s thinking is primarily egocentric. At this stage thinking is mostly based on likes and pleasures. This stage progresses toward having punishment guide behavior. The person’s moral reason for acting, the “why,” eventually relates to the consequences that the person believes will occur. These consequences come in the form of punishment or reward. It is at this level that children view illness as a punishment for fighting with their siblings or disobeying their parents. Nurses need to be aware of this egocentric thinking and reinforce that the child does not become ill because of wrongdoing.

Stage 1: Punishment and Obedience Orientation: In this first stage a child’s response to a moral dilemma is in terms of absolute obedience to authority and rules. A child in this stage reasons, “I must follow the rules; otherwise I will be punished.” Avoiding punishment or the unquestioning deference to authority is characteristic motivation to behave. Physical consequences guide right and wrong choices. If the child is caught, it must be wrong; if he or she escapes, it must be right.

Stage 2: Instrumental Relativist Orientation: In this stage the child recognizes that there is more than one right view; a teacher has one view that is different from that of the child’s parent. The decision to do something morally right is based on satisfying one’s own needs and occasionally the needs of others. The child perceives punishment not as proof of being wrong (as in stage 1) but as something that one wants to avoid. Children at this stage follow their parent’s rule about being home in time for supper because they do not want to be confined to their room for the rest of the evening if they are late.

Level II: Conventional Reasoning: At level II, conventional reasoning, the person sees moral reasoning based on his or her own personal internalization of societal and others’ expectations. A person wants to fulfill the expectations of the family, group, or nation and also develop a loyalty to and actively maintain, support, and justify the order. Moral decision making at this level moves from, “What’s in it for me?” to “How will it affect my relationships with others?” Emphasis now is on social rules and a community-centered approach (Berger, 2007). Nurses observe this when family members make end-of-life decisions for their loved ones. Individual members often struggle with this type of moral dilemma. Grief support involves an understanding of the level of moral decision making of each family member (see Chapter 36).

Stage 3: Good Boy–Nice Girl Orientation: The individual wants to win approval and maintain the expectations of one’s immediate group. “Being good” is important and defined as having good motives, showing concern for others, and keeping mutual relationships through trust, loyalty, respect, and gratitude. One earns approval by “being nice.” For example, a person in this stage stays after school and does odd jobs to win the teacher’s approval.

Stage 4: Society-Maintaining Orientation: Individuals expand their focus from a relationship with others to societal concerns during stage 4. Moral decisions take into account societal perspectives. Right behavior is doing one’s duty, showing respect for authority, and maintaining the social order. Adolescents choose not to attend a party where they know beer will be served, not because they are afraid of getting caught, but because they know that it is not right.

Level III: Postconventional Reasoning: The person finds a balance between basic human rights and obligations and societal rules and regulations in the level of postconventional reasoning. Individuals move away from moral decisions based on authority or conformity to groups to define their own moral values and principles. Individuals at this stage start to look at what an ideal society would be like. Moral principles and ideals come into prominence at this level (Berger, 2007).

Stage 5: Social Contract Orientation: Having reached stage 5, an individual follows the societal law but recognizes the possibility of changing the law to improve society. The individual also recognizes that different social groups have different values but believes that all rational people would agree on basic rights such as liberty and life. Individuals at this stage make more of an independent effort to determine what society should value rather than what the society as a group would value, as would occur in stage 4. The United States Constitution is based on this morality.

Stage 6: Universal Ethical Principle Orientation: Stage 6 defines “right” by the decision of conscience in accord with self-chosen ethical principles. These principles are abstract, like the Golden Rule, and appeal to logical comprehensiveness, universality, and consistency (Kohlberg, 1981). For example, the principle of justice requires the individual to treat everyone in an impartial manner, respecting the basic dignity of all people, and guides the individual to base decisions on an equal respect for all. Civil disobedience is one way to distinguish Stage 5 from Stage 6. Stage 5 emphasizes the basic rights, the democratic process, and following laws without question, whereas stage 6 defines the principles by which agreements will be most just. For example, a person in stage 5 follows a law, even if it is not fair to a certain racial group. An individual in stage 6 may not follow a law if it does not seem just to the racial group. For example, Martin Luther King believed that although we need laws and democratic processes, people who are committed to justice have an obligation to disobey unjust laws and accept the penalties for disobeying these laws (Crain, 1985).

Kohlberg’s Critics

Kohlberg constructed a systemized way of looking at moral development and is recognized as a leader in moral developmental theory. However, critics of his work raise questions about his choice of research subjects. For example, most of Kohlberg’s subjects were males raised in Western philosophical traditions. Research attempting to support Kohlberg’s theory with individuals raised in the Eastern philosophies found that individuals raised in Eastern philosophies never rose above stages 3 or 4 of Kohlberg’s model. To some, these findings suggest that people from Eastern philosophies have not reached higher levels of moral development, which is untrue. Others believe Kohlberg’s research design did not allow a way to measure those raised within a different culture.

Kohlberg has also been criticized for age and gender bias. Carol Gilligan, an associate, criticizes Kohlberg for his gender biases. She believes that he developed his theory based on a justice perspective that focused on the rights of individuals. In contrast, Gilligan’s research looked at moral development from a care perspective that viewed people in their interpersonal communications, relationships, and concern for others (Santrock, 2009). She believes that females are socialized to be nurturing and caring and thus are reluctant to make judgments based solely on justice (Berger, 2007). Other researchers have examined Gilligan’s theory in studies with children and have not found evidence to support gender differences (Berger, 2007; Santrock, 2009).

Moral Reasoning and Nursing Practice

Nurses need to know their own moral reasoning level. Recognizing your own moral developmental level is essential in separating your beliefs from others when helping patients with their moral decision-making process. It is also important to recognize the level of moral reasoning used by other members of the health care team and its influence on a patient’s care plan. Ideally all members of the health care team are on the same level, creating a unified outcome. This is exemplified in the following scenario: The nurse is caring for a homeless person and believes that all patients deserve the same level of care. The case manager, who is responsible for resource allocation, complains about the patient’s length of stay and the amount of resources being expended on this one patient. The nurse and the case manager are in conflict because of their different levels of moral decision making within their practices. They decide to hold a health care team conference to discuss their differences and the ethical dilemma of ensuring that the patient receives an appropriate level of care.

Developmental theories help nurses to use critical thinking skills when asking how and why people respond as they do. From the diverse set of theories included in this chapter, the complexity of human development is evident. No one theory successfully describes all the intricacies of human growth and development. Today’s nurse needs be knowledgeable about several theoretical perspectives when working with patients.

Your assessment of a patient requires a thorough analysis and interpretation of data to form accurate conclusions about his or her developmental needs. Accurate identification of nursing diagnoses relies on your ability to consider developmental theory in data analysis. You compare normal developmental behaviors with those projected by developmental theory. Examples of nursing diagnoses applicable to patients with developmental problems include risk for delayed development, delayed growth and development, and risk for disproportionate growth.

Growth and development, as supported by a life-span perspective, is multidimensional. The theories included are the basis for a meaningful observation of an individual’s pattern of growth and development. They are important guidelines for understanding important human processes that allow nurses to begin to predict human responses and recognize deviations from the norm.

Key Points

• Nurses administer care for individuals at various developmental stages. Developmental theory provides a basis for nurses to assess and understand the responses seen in their patients.

• Humans continue to develop throughout their lives. Development is not limited to childhood and adolescence; persons grow and develop throughout their life span.

• Theory is a way to account for how and why people grow up as they do. Theories provide a framework to clarify and organize existing observations to explain and try to predict human behavior.

• Growth refers to the quantitative changes that nurses measure and compare to norms.

• Development implies a progressive and continuous process of change, leading to a state of organized and specialized functional capacity. These changes are quantitatively measurable but are more distinctly measured in qualitative changes.

• Biophysical development theory explores theories of why individuals age from a biological standpoint, why development follows a predictable sequence, and how environmental factors can influence development.

• Cognitive development focuses on the rational thinking processes that include the changes in how children, adolescents, and adults perform intellectual operations.

• Developmental tasks are age-related achievements, the success of which leads to happiness; whereas failure often leads to unhappiness, disapproval, and difficulty in achieving later tasks.

• Developmental crisis occurs when a person is having great difficulty meeting tasks of the current developmental period.

• Psychosocial theories describe human development from the perspectives of personality, thinking, and behavior with varying degrees of influence from internal biological forces and external societal/cultural forces.

• Temperament is a behavioral pattern that affects the individual’s interactions with others.

• Moral development theory attempts to define how moral reasoning matures for an individual.

Clinical Application Questions

Preparing for Clinical Practice

1. Mrs. Banks is an 84-year-old woman who has recently been diagnosed with breast cancer. She also has severe cardiovascular disease that limits her choices of treatment. She has completed a series of radiation treatments that have left her exhausted and unable to participate in her usual activities. Her oncologist now recommends a cycle of chemotherapy treatments that her cardiologist believes would be fatal. Her family is urging her to do all that is recommended. The patient, who is in good spirits despite her diagnosis, decides against further medical treatment.

a. How does Mrs. Banks’ cognitive developmental stage impact her decision making related to her health care?

b. Which of the psychosocial developmental theories helps explain her decision?

c. Using your knowledge of her developmental stage, how can you help the family adjust to her choice?

2. Amanda Peters, 9 years old, was admitted to the unit yesterday with a new diagnosis of type I diabetes. Her mother has spent the night with her and is arranging the food on Amanda’s breakfast tray when you enter the room to check her blood sugar and administer her insulin. Although the diabetes educator will be meeting with Amanda and her family, as part of her care today you want to begin her discharge teaching.

a. According to Piaget’s theory, how will Amanda’s cognitive development direct your teaching?

b. Using Erikson’s theory as a basis, what psychosocial factors will you consider when discussing home care with Amanda and her family?

c. Based on her developmental stage, how can Amanda’s family support her active participation in care?

3. You have been assigned to care for Daniel Jackson, a 17-year-old male who was in an automobile accident several days ago and sustained a fractured pelvis. He has had a surgical repair and remains on bed rest. School is starting next month and he was scheduled to begin football practice next week. During bedside report he refuses to make eye contact with the nursing staff or respond to any questions to help direct his care.

a. How will you incorporate your knowledge of adolescent development as you establish priorities for his care?

b. Thinking about Erikson’s theory, what psychosocial concerns do you anticipate that Daniel might experience during his hospitalization and recovery period?

c. How will Daniel’s cognitive development contribute to his future planning?

![]() Answers to Clinical Application Questions can be found on the Evolve website.

Answers to Clinical Application Questions can be found on the Evolve website.

Are You Ready to Test Your Nursing Knowledge?

1. The nurse is aware that preschoolers often display a developmental characteristic that makes them treat dolls or stuffed animals as if they have thoughts and feelings. This is an example of:

2. An 18-month-old child is noted by the parents to be “angry” about any change in routine. This child’s temperament is most likely to be described as:

3. Nine-year-old Brian has a difficult time making friends at school and being chosen to play on the team. He also has trouble completing his homework and, as a result, receives little positive feedback from his parents or teacher. According to Erikson’s theory, failure at this stage of development results in:

4. The nurse teaches parents how to have their children learn impulse control and cooperative behaviors. This would be during which of Erickson’s stages of development?

5. When Ryan was 3 months old, he had a toy train; when his view of the train was blocked, he did not search for it. Now that he is 9 months old, he looks for it, reflecting the presence of:

6. When preparing a 4-year-old child for a procedure, which method is developmentally most appropriate for the nurse to use?

1. Allowing the child to watch another child undergoing the same procedure

2. Showing the child pictures of what he or she will experience

3. Talking to the child in simple terms about what will happen

4. Preparing the child through play with a doll and toy medical equipment

7. A 35-year-old woman is speaking with you about her recent diagnosis of a chronic illness. She is concerned about her treatment options in relation to her ability to continue to care for her family. As she considers the options and alternatives, she incorporates information, her values, and emotions to decide which plan will be the best fit for her. She is using which form of cognitive development?

8. You are caring for a recently retired man who appears withdrawn and says he is “bored with life.” Applying the work of Havinghurst, you would help this individual find meaning in life by:

1. Encouraging him to explore new roles.

2. Encouraging relocation to a new city.

9. Place the following stages of Freud’s psychosexual development in the proper order by age progression.

10. According to Piaget’s cognitive theory, a 12-year-old child is most likely to engage in which of the following activities?

1. Using building blocks to determine how houses are constructed

2. Writing a story about a clown who wants to leave the circus

11. Allison, age 15 years, calls her best friend Laura and is crying. She has a date with John, someone she has been hoping to date for months, but now she has a pimple on her forehead. Laura firmly believes that John and everyone else will notice the blemish right away. This is an example of the:

12. Elizabeth, who is having unprotected sex with her boyfriend, comments to her friends, “Did you hear about Kathy? You know, she fools around so much; I heard she was pregnant. That would never happen to me!” This is an example of adolescent:

13. Teaching an older adult how to use e-mail to communicate with a grandchild who lives in another state is an example of ____________, which aids cognitive performance by using new approaches.

14. Dave reports being happy and satisfied with his life. What do we know about Dave?

1. He is in one of the later developmental periods, concerned with reviewing his life.

2. He is atypical, since most people in any of the developmental stages report significant dissatisfaction with their lives.

3. He is in one of the earlier developmental periods, concerned with establishing a career and satisfying long-term relationships.

4. It is difficult to determine Dave’s developmental stage since most people report overall satisfaction with their lives in all stages.

15. You are working in a clinic that provides services for homeless people. The current local regulations prohibit providing a service that you believe is needed by your patients. You adhere to the regulations but at the same time are involved in influencing authorities to change the regulation. This action represents which stage of moral development?

Answers: 1. 4; 2. 2; 3. 3; 4. 2; 5. 1; 6. 4; 7. 4; 8. 1; 9. 3, 5, 2, 1, 4; 10. 2; 11. 1; 12. 4; 13. 3; 14. 4; 15. 2.

References

Baltes, PB, Freund, AM, Li, S. The psychological science of human aging. In: Johnson ML, ed. The Cambridge handbook of age and aging. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2005:47.

Berger, KS. The developing person: Through the life span, ed 7. New York: Worth; 2007.

Carstensen, LL, Isaacowitz, DM, Charles, ST. Taking time seriously: A theory of socioemotional selectivity. Am Psychol. 1999;54:165.

Crain, WC, Theories of development. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1985. http://faculty.plts.edu/gpence/html/kohlberg.htm [Accessed June 19, 2011].

Erikson, E. Childhood and society. New York: Norton; 1963.

Gesell, A. Studies in child development. New York: Harper; 1948.

Hockenberry, MJ, Wilson, D. Wong’s nursing care of infants and children, ed 9. St Louis: Mosby; 2011.

Kohlberg, L. The philosophy of moral development: Moral stages and the idea of justice. San Francisco: Harper & Row; 1981.

Reichstadt, J, et al. Older adults’ perspectives on successful aging: Qualitative interviews. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;18(7):567.

Santrock, JW. Life span development, ed 12. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2008.

Santrock, JW. A topical approach to life span development, ed 5. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2009.

Research References

Cully, JA, et al. Predicting quality of life in veterans with heart failure: The role of disease severity, depression, and comorbid anxiety. Behav Med. 2010;36:70–76.

Hägglund, L, et al. Depression among elderly people with and without heart failure, managed in a primary healthcare setting. Scandinav J Caring Sci. 2008;22:376–382.

Kessler, RC, et al. Age differences in major depression: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). Psychol Med. 2010;40(2):225–237.