Sexuality

• Identify personal attitudes, beliefs, and biases related to sexuality.

• Discuss the nurse’s role in maintaining or enhancing a patient’s sexual health.

• Describe key concepts of sexual development across the life span.

• Identify causes of sexual dysfunction.

• Assess a patient’s sexuality.

• Formulate appropriate nursing diagnoses for patients with alterations in sexuality.

• Identify patient risk factors in the area of sexual health.

• Identify and describe nursing interventions to promote sexual health.

• Evaluate patient outcomes related to sexual health needs.

• Identify other health care providers and community resources available to help patients resolve sexual concerns that are outside the nurse’s level of expertise.

• Use critical thinking skills when helping patients meet their sexual needs.

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Potter/fundamentals/

Sexuality is part of a person’s personality and is important for overall health. Even though discussion of sexual topics has increased over the years, many adults lack knowledge regarding sexuality. Although patients may be hesitant to bring up their concerns, they often share their feelings when the nurse addresses sexuality in a relaxed, matter-of-fact manner. To feel comfortable addressing sexuality, nurses need therapeutic communication skills and to be knowledgeable about sexual functioning, issues, and assessment. Many values and issues surround sexuality. Religious teachings, cultural influences on gender roles, beliefs about sexual orientation, and social and environmental climates influence the values systems for both patients and health care providers.

Sexuality has many definitions. Expression of an individual’s sexuality is influenced by interaction among biological, sociological, psychological, spiritual, economic, political, religious, and cultural factors (Gorman and Sultan, 2008; World Health Organization [WHO], 2010). In addition, values, attitudes, behaviors, relationships with others, and the need to establish emotional closeness with others influence sexuality.

Sexuality differs from sexual health. According to WHO (2010), sexual health is “a state of physical, emotional, mental and social well-being in relation to sexuality; it is not merely the absence of disease, dysfunction or infirmity.” People who are sexually healthy have a positive and respectful approach to sexuality and sexual relationships. They also have a potential for having pleasurable and safe sexual experiences that are free from coercion, discrimination, and violence.

Scientific Knowledge Base

Nurses help patients achieve sexual health by having a sound scientific knowledge base regarding sexuality. A basic understanding of sexual development, sexual orientation, contraception, abortion, and sexually transmitted infections (STIs) is necessary.

Sexual Development

Sexuality changes as a person grows and develops. Each stage of development brings changes in sexual functioning and the role of sexuality in relationships.

Infancy and Early Childhood

The first 3 years of life are crucial in the development of gender identity (Edelman and Mandle, 2010). The child identifies with the parent of the same sex and develops a complementary relationship with the parent of the opposite sex. Children become aware of differences between the sexes, begin to perceive that they are either male or female, and interpret the behaviors of others as behavior appropriate for a female or a male.

School-Age Years

During the school years parents, educators, and peer groups serve as role models and teachers about how men and women act with and relate to one another. School-age children generally have questions regarding the physical and emotional aspects of sex. They need accurate information from home and school about changes in their bodies and emotions during this period and what to expect as they move into puberty (Edelman and Mandle, 2010). Knowledge about normal emotional and physical changes associated with puberty decreases anxiety as these changes begin to happen. Menstruation or nocturnal emission is sometimes frightening for uninformed children, and some view them as evidence of a dreadful disease.

Puberty/Adolescence

The emotional changes during puberty and adolescence are as dramatic as the physical ones. The adolescent functions within a powerful peer group, with the almost constant anxiety of “Am I normal?” and “Will I be accepted?” (Fig. 34-1). They face many decisions and need accurate information on topics such as body changes, sexual activity, emotional responses within intimate sexual relationships, STIs, contraception, and pregnancy.

FIG. 34-1 Adolescents function within a powerful network of peers as they explore their sexual identity. (© bikeriderlondon.)

In the United States approximately 46% of high school students report that they have had sexual intercourse at least one time and 14% of high school students had had four or more sexual partners (CDC, 2010a). One reason why adolescents are sexually active is because many believe that sexual intercourse helps them achieve goals of intimacy, relationships, and pleasure (Fantasia, 2009). A substantial number of sexually active teenagers do not protect themselves from pregnancy or STIs. The dynamics of sexual risk taking are not fully understood, but studies have found correlations among drug/alcohol use, sexual abuse, and unsafe sex (Elkington, Bauermeister, and Zimmerman, 2010; Fantasia, 2009). Adolescents tend to think that unwanted pregnancy, STIs, and other negative outcomes of sexual behavior are not likely to happen to them. Parents need to understand the importance of providing factual information, sharing their values, and promoting sound decision-making skills. They need to know that, even with the best guidance and information, adolescents make their own decisions and need to be held accountable for them.

Adolescence is often a time when individuals explore their primary sexual orientation (Bowder and Greenberg, 2010). They may identify with a sexual minority group such as lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender (LGBT) (Young-Bruehl, 2010). Adolescents often face significant stress related to these choices and benefit from education about sexuality issues (Doty et al., 2010). Support from peers, family, school counselors, clergy, nurses, and other health professionals is important during this time.

Young Adulthood

Although young adults have matured physically, they continue to explore and mature emotionally in relationships. Intimacy and sexuality are issues for all young adults whether they are in a sexual relationship, choose to abstain from sex, remain single by choice, are homosexual, or are widowed. People are sexually healthy in numerous ways. Sexual activity is often defined as a basic need, and healthy sexual desire is channeled into forms of intimacy throughout a lifetime.

As sexually active adults develop intimate relationships, they learn techniques of stimulation that are satisfying to both themselves and their sexual partners. Some adults need permission or affirmation that alternative ways of sexual expression other than penile-vaginal intercourse are normal. Other individuals require significant education or therapy to achieve mutually satisfying sexual relationships.

Middle Adulthood

Changes in physical appearance in middle adulthood sometimes lead to concerns about sexual attractiveness. In addition, actual physical changes related to aging affect sexual functioning. Decreasing levels of estrogen in perimenopausal woman lead to diminished vaginal lubrication and decreased vaginal elasticity. Both of these changes often lead to dyspareunia, or the occurrence of pain during intercourse. Decreasing levels of estrogen may also result in a decreased desire for sexual activity. As men age, they are likely to experience changes such as an increase in the postejaculatory refractory period and delayed ejaculation. Anticipatory guidance regarding these normal changes, using vaginal lubrication, and creating time for caressing and tenderness ease concerns regarding sexual functioning. Some aging adults also need to adjust to the impact of chronic illness, medications, aches, pains, and other health concerns about sexuality.

Later in the adult years some individuals have to adjust to the social and emotional changes associated with children moving away from home. This results in either a time of renewed intimacy between partners or a time when formerly intimate partners realize that they no longer care for one another or have common interests. In either case, when children leave home, intimate relationships usually change.

Older Adulthood

Sexuality in older adults is an important aspect of health that is often overlooked by health care providers. Studies show a positive correlation between sexual activity and physical health in older adults (Lindau and Gavrilova, 2010; Lindau et al., 2007). Many studies suggest that older adults retain an interest in sexual function and are sexually active. Other studies conclude that there is a decline of sexual interest and behavior among older adults, especially in women (Box 34-1). Factors that determine sexual activity in older adults include present health status, past and present life satisfaction, and the status of marital or intimate relationships. For example, many older women are widowed or divorced and lack available sexual partners, which accounts for their decline in sexual activity. Nurses working with older adults need to be aware of the sexuality of their patients, assess interest and functioning, and plan accordingly (Wallace, 2008). It is essential to maintain a nonjudgmental attitude and convey that sexual activity is normal in later years. Emphasize that sexual activity is not essential to maintaining quality of life, especially when patients have decided not to remain sexually active.

To be effective in promoting sexual health, nurses need to understand the normal sexual changes that occur as people age. The excitement phase prolongs in both men and women, and it usually takes longer for them to reach orgasm. The refractory time following orgasm is also longer. Both genders experience a reduced availability of sex hormones. Men often have erections that are less firm and shorter acting. Women usually do not have difficulty maintaining sexual function unless they have a medical condition that impairs their sexual activity. Typically the infrequency of sex in older women is related to the age, health, and sexual function of their partner. Women continue to experience changes related to menopause, and those with problems related to urinary incontinence often experience embarrassment during intercourse. Couples who have physically disabling conditions often need information about which positions are more comfortable when having sexual intercourse.

Sexual Orientation

Sexual orientation describes the predominant pattern of a person’s sexual attraction over time. Many stereotypical myths remain about people who are LGBT. Current evidence indicates that they experience decreased access to health care and do not readily seek preventive care (Brown, 2009; Williamson, 2010). Nonjudgmental nurses who have a solid knowledge base help to discourage these myths and provide nursing care that includes attention to the person’s sexual orientation.

Contraception

Numerous contraceptive options are available to sexually active couples today. They provide varying levels of protection against unwanted pregnancies. Some methods do not require a prescription, whereas others require a prescription or some other type of intervention from a health care provider. Methods that are effective for contraception do not always reduce the risk of STIs. For example, the pill and intrauterine device (IUD) are effective as birth control but not for protection from STIs. Effectiveness varies with each contraceptive method and the consistency of use. Unplanned pregnancies occur because contraceptives are not used, are used inconsistently, or are used improperly (Gabelnick et al., 2009).

Nonprescription Contraceptive Methods

Nonprescription methods for contraception include abstinence, barrier methods, and timing of intercourse with regard to the woman’s ovulation cycle. Although abstinence from sexual intercourse is 100% effective, it is often difficult for both men and women to use consistently. Any act of unprotected intercourse potentially results in pregnancy and exposure to STIs.

Barrier methods include over-the-counter spermicidal products and condoms. Spermicidal products (e.g., creams, jellies, foams, and sponges) are put into the vagina before intercourse to create a spermicidal barrier between the uterus and ejaculated sperm. A condom is a thin rubber sheath that fits over the penis to prevent entrance of sperm into the vagina. A diaphragm is a barrier method, which must be used with a spermacide with each sexual encounter. Vaginal spermicides and condoms are most effective when instructions are followed carefully; their combined use is more effective in preventing pregnancy than the use of either one alone (Warner and Steiner, 2009).

Nonprescription methods of contraception based on the physiological changes of the menstrual cycle include the rhythm, basal body temperature, cervical mucus, and fertility-awareness methods. Couples who use these methods need to understand the reproductive cycle of the woman’s body and the subtle signs and signals that her body gives during the cycle. To prevent pregnancy couples abstain from sexual intercourse during designated fertile periods.

Methods That Require a Health Care Provider’s Intervention

Contraceptive methods that require the intervention of a health care provider include hormonal contraception, IUDs, the diaphragm, the cervical cap, and sterilization. Hormonal contraception is available in several forms: oral contraceptive pills, vaginal contraceptive rings, hormonal injections, subdermal implant, transdermal skin patches, and IUDs. Hormonal contraception alters the hormonal environment to prevent ovulation, thicken cervical mucus, and thin the lining of the uterus.

An IUD is a plastic device inserted by a health care provider into the uterus through the cervical opening. IUDs contain either copper or progesterone. The primary mechanism by which both types of IUDs prevent pregnancy is to stop the sperm from fertilizing an egg (Grimes, 2009; Murphy, 2011; Ortiz and Croxatto, 2007). The release of progesterone may also increase cervical mucus thickness and alter the lining of the uterus.

The diaphragm is a round, rubber dome that has a flexible spring around the edge. It is used with a contraceptive cream or jelly and is inserted in the vagina so it provides a contraceptive barrier over the cervical opening. The woman needs to be refitted after a significant change in weight (10-lb gain or loss) or pregnancy. The cervical cap functions like the diaphragm; however, it covers only the cervix. It may be left in place longer, and some perceive it as more comfortable than the diaphragm.

Sterilization is the most effective contraception method other than abstinence. Female sterilization, or tubal ligation, involves cutting, tying, or otherwise ligating the fallopian tubes. In male sterilization, or vasectomy, the vas deferens, which carries the sperm away from the testicles, is cut and tied. Both a tubal ligation and a vasectomy are usually considered permanent surgical procedures.

Sexually Transmitted Infections

The incidence of STIs continues to increase. About 19 million people in the United States are diagnosed with an STI each year; almost half of them are 15 to 24 years of age (CDC, 2009). The prevalence of STIs is a major health concern for several reasons. Black and Hispanic populations are diagnosed with STIs more frequently than whites, and women have more complications associated with STIs than men. In addition, social factors such as poverty, low literacy, discrimination, use of illegal drugs (e.g., crack cocaine, methamphetamine), incarceration, sexual abuse, and racial segregation contribute to racial disparities in the STI rates (Hogben and Leichliter, 2008). Treatment of STIs in America costs about $16 million annually (CDC, 2009). Commonly diagnosed STIs include syphilis, gonorrhea, chlamydia, trichomoniasis, and infection with the human papillomavirus (HPV) and herpes simplex virus (HSV) type II (genital warts and genital herpes, respectively).

As the name implies, STIs are transmitted from infected individuals to partners during intimate sexual contact. The site of transmission is usually genital, but sometimes it is oral-genital or anal-genital. People most likely to be infected share one key characteristic: unprotected sex with multiple partners. Gonorrhea, chlamydia, syphilis, and pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) are caused by bacteria and are usually curable with antibiotics. Patients need to take antibiotics for the full course of treatment. However, an emerging concern is that some of these bacterial infections (e.g., gonorrhea and syphilis) are now developing antibiotic-resistant strains. Infections such as genital herpes, HPV, and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) are caused by viruses and cannot be cured.

A major problem in dealing with STIs is finding and treating the people who have them. Some people do not know that they are infected because symptoms are sometimes absent or go unnoticed (CDC, 2009). Common symptoms of an STI include discharge from the vagina, penis, or anus; pain during sex or when urinating; blisters or sores in the genital area; and fever (Marrazzo et al., 2009). Because sexual behavior often includes the whole body rather than just the genitalia, many parts of the body are potential sites for an STI. The ears, mouth, throat, tongue, nose, and eyelids are sometimes used for sexual pleasure. The perineum, anus, and rectum are also frequently included in sexual activity. Furthermore, any contact with another person’s body fluids around the head or an open lesion on the skin, anus, or genitalia can transmit an STI.

Sometimes people do not seek treatment because they are embarrassed to discuss sexual symptoms or concerns. They are also often hesitant to talk about their sexual behavior if they believe that it is not “normal.” Any sexual behavior that embarrasses the patient often hinders the detection of an STI. Develop communication skills and a nonjudgmental attitude to provide effective care for those diagnosed with one. Detect valuable clues about an STI by establishing trust, talking with patients, and asking questions in a caring manner. Assess attitudes toward sexuality and adjust the intervention to make it acceptable to the patient’s sexual value system.

Human Immunodeficiency Virus Infection

HIV infection is sometimes spread through sexual contact. Although HIV is present in most body fluids, it is a bloodborne pathogen. Transmission occurs when there is an exchange of body fluid. Primary routes of transmission include contaminated intravenous (IV) needles, anal intercourse, vaginal intercourse, oral-genital sex, and transfusion of blood and blood products. Populations that are at risk for HIV include people who use illicit IV drugs and share needles, individuals with hemophilia, and people who have unprotected sexual contact.

The natural history of HIV is composed of three stages. The primary infection stage lasts for about a month after contracting the virus. During this time the person often experiences flulike symptoms. Then he or she enters the clinical latency phase; at this time there are no symptoms of infection. HIV antibodies appear in the blood about 6 weeks to 3 months after infection. If left untreated, people who are infected with HIV live about 10 years. The last stage, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), happens when the person begins to show symptoms of the disease. AIDS is a serious, debilitating, and eventually fatal disease. Highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) greatly increases the survival time of persons who live with HIV/AIDS (Marrazzo et al., 2009).

Human Papillomavirus Infection

HPV is the most common STI in the United States, with approximately 6 million new infections every year (CDC, 2010b). Most HPV infections are asymptomatic and self-limiting. However, certain types of HPV can cause cervical cancer in women and anogenital cancers and genital warts in both men and women (CDC, 2010b; Palefsky, 2010). HPV is spread through direct contact with warts, semen, and other body fluids from others who have the disease. The textured warts often have a cauliflower appearance and are most common on the penis and scrotum in men and the vagina and cervix in women. An HPV vaccine that protects both men and woman against the types of HPV that most commonly cause health concerns is available (CDC, 2010b).

Chlamydia

An infection of the bacteria Chlamydia trachomatis causes chlamydia. It is the most commonly reported bacterial STI in the United States, affecting about 2.8 million Americans each year (CDC, 2009). Chlamydia infects the genitourinary tract and rectum in adults, and it causes conjunctivitis and pneumonia in newborn babies. Transmission occurs when the person comes in contact with fluids from infected sites (e.g., cervix or urethra). It is a major health issue because, if it is not treated, it causes PID, ectopic pregnancy, infertility, and neonatal complications. The risk of infection is higher in people who are less than 25 years old and who do not consistently use barrier contraceptives. It is also common in people who have multiple sex partners and who are infected with other STIs (Marrazzo et al., 2009). Most chlamydia infections go undiagnosed and untreated because 75% of women and 50% of men experience no symptoms (Grimshaw-Mulcahy, 2008). Symptoms that women often experience include dysuria, urinary frequency, and purulent vaginal discharge. In men it usually infects the urethra and causes nongonococcal urethritis (NGU). Dysuria and urethral discharge are common symptoms of NGU (Marrazzo et al., 2009).

Nursing Knowledge Base

Use critical thinking skills and basic nursing knowledge when addressing patients’ sexual health needs. Draw from the following areas of nursing knowledge: sociocultural dimensions of sexuality, decisional issues, and alterations in sexual health.

Sociocultural Dimensions of Sexuality

Cultural rules and norms regarding acceptable behavior within the culture influence sexuality. People assign different meanings to sexuality based on their culture, gender, education, socioeconomic status, and religion (Giger and Davidhizar, 2008; Stilos et al., 2008). Society plays a powerful role in shaping sexual values and attitudes and supporting specific expression of sexuality in its members.

Each cultural and social group has its own set of rules and norms that guide sexual behavior, sexual health, and the willingness to discuss this private part of life. For example, cultural norms influence how people find partners, whom they choose as partners, how they relate to one another, how often they have sex, and what they do when they have sex. Personal beliefs enable certain practices and prohibit others (Box 34-2).

Impact of Pregnancy and Menstruation on Sexuality

Sexual interest and activity of women and their partners vary during pregnancy and menstruation. Some cultures encourage sexual intercourse or male-female contact during menstruation and pregnancy, but other cultures strictly forbid it. For example, in the Hindu culture a woman avoids worship, cooking, and other members of the family during menstruation. Research has found no physiological contraindication to intercourse during menstruation or during most pregnancies. Female sexual interest tends to fluctuate during pregnancy, with increased interest during the second trimester and often decreased interest during the first and third trimesters. There is often a decrease in libido during the first trimester because of nausea, fatigue, and breast tenderness. During the second trimester blood flow to the pelvic area increases to supply the placenta, resulting in increased sexual enjoyment and libido. During the third trimester the increased abdominal size often makes finding a comfortable position difficult (Lowdermilk et al., 2010).

Discussing Sexual Issues

Sexuality is a significant part of each person’s being, yet sexual assessment and interventions are not always included in health care (Lindau et al., 2007; Stilos et al., 2008). The area of sexuality is often emotionally charged for nurses and patients. Sometimes nurses avoid discussing sexual issues with patients because they lack information or have different values than their patients. Nurses who have difficulty discussing topics related to sexuality need to explore their discomfort and develop a plan to address it. If you are uncomfortable with topics related to sexuality, the patient is unlikely to share sexual concerns with you.

Decisional Issues

Individuals make many decisions about their sexuality. Some nurses help patients make decisions about contraception and abortion.

Contraception

Decisions patients make regarding contraception have far-reaching effects on their lives. Pregnancy, whether planned or unplanned, significantly affects the life of the mother and father and often their support network. Effects are physical, interpersonal, social, financial, and societal. The choice to use contraception is multifaceted and not completely understood. Factors that affect the effectiveness of contraception include the method of contraception, the couple’s understanding of the contraceptive method, the consistency of use, and compliance with the requirements of the chosen method. Choice of contraception method varies in relation to the age, marital status, income, education, and previous pregnancies of the woman (Mosher and Jones, 2010).

Abortion

Half of all pregnancies in the United States are unplanned; the majority of unplanned pregnancies occur in teenagers, women over 40 years of age, and low-income nonwhite women (Paul and Stewart, 2009). Almost half of unintended pregnancies end in abortion (Mosher and Jones, 2010). Abortions have been performed since ancient times. The safety and availability of abortions in the United States improved after the 1973 Supreme Court decision Roe v Wade, which established the right of every woman to have an abortion. Abortions are safer and less costly when performed in the early weeks of pregnancy.

Abortion is a hotly debated issue. Women and their partners who face an unwanted pregnancy may consider it. If caring for a patient contemplating abortion, provide an environment in which the patient is able to discuss the issue openly, allowing exploration of various options with an unwanted pregnancy. Discuss religious, social, and personal issues in a nonjudgmental manner with patients. Reasons for choosing an abortion vary and include terminating an unwanted pregnancy or aborting a fetus known to have birth defects. When a woman chooses abortion as a way of dealing with an unwanted pregnancy, the woman and often her partner experience a sense of loss, grief, and/or guilt.

Be aware of personal values related to abortion. Nurses are entitled to their personal views and should not be forced to participate in counseling or procedures contrary to beliefs and values. It is essential to choose specialties or places of employment where personal values are not compromised and the care of a patient in need of health care is not jeopardized.

Prevention of Sexually Transmitted Infections

Abstinence is the only practice that is considered to be 100% effective in preventing transmission of STIs. Responsible sexual behavior includes knowing one’s sexual partner, being able to openly discuss sexual and drug-use history with the partner, not allowing drugs or alcohol to influence decision making, and using protective devices.

Alterations in Sexual Health

Infertility is the inability to conceive after 1 year of unprotected intercourse. A couple who wants to conceive and cannot has special needs. Some experience a sense of failure and feel that their bodies are defective. Sometimes the desire to become pregnant grows until it permeates most waking moments. Some individuals become preoccupied with creating just the right circumstances for conception. With advances in reproductive technology, infertile couples face many choices that involve religious and ethical values and financial limitations.

Choices for the infertile couple include pursuit of adoption, medical assistance with fertilization, or adapting to the probability of remaining childless. Organizations such as RESOLVE: The National Organization of Infertility, a national support group for couples with infertility, or international adoption groups provide couples with support and offer referral sources.

Sexual Abuse

Sexual abuse is a widespread health problem. Abuse crosses all gender, socioeconomic, age, and ethnic groups. Most often it is at the hands of a former intimate partner or family member. Sexual abuse has far-ranging effects on physical and psychological functioning (Edelman and Mandle, 2010). Sometimes sexual abuse begins, continues, or even intensifies during pregnancy. Cues that raise a question of possible sexual abuse include extreme jealousy and refusal to leave a woman’s presence. The overall appearance is sometimes that of a very concerned and caring husband or boyfriend, when the underlying reason for this behavior is very different.

When you recognize abuse, mobilize support for the victim and the family. All family members usually require therapy to promote healthy interactions and relationships. Rape victims often need to work through the crisis before feeling comfortable with intimate expressions of affection. The partner needs to know how to help and support the victim. Children who have been sexually molested need to understand that they are not at fault for the incident. The parents need to understand that their response is critical to how the child reacts and adapts. Nurses are in an ideal position to assess occurrences of sexual violence, help patients confront these stressors, and educate individuals regarding community services. Nurses must also report suspected abuse to the proper authorities.

Personal and Emotional Conflicts

Ideally sex is a natural, spontaneous act that passes easily through a number of recognizable physiological stages and ends in one or more orgasms. In reality this sequence of events is more the exception than the rule. Nurses meet patients who have problems with one or more of the stages of sexual activity, including the feeling of wanting sex, the physiological processes and emotions of having sex, and the feelings experienced after sex. For example, some women and men who are taking antidepressants report that their ability to reach orgasm is negatively affected.

Sexual Dysfunction

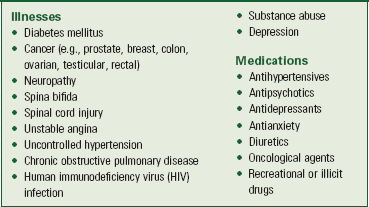

Sexual dysfunction, the absence of complete sexual functioning, is common. The incidence of sexual dysfunction in the general population is estimated to be as high as 40% in men and 45% in women (Gorman and Sultan, 2008; Murtagh, 2010; Shifren et al., 2008). It is more prevalent in men and women with poor emotional and physical health (Box 34-3). Sometimes the exact cause cannot be determined.

Erectile dysfunction (ED) affects as many as 40% of men between 40 and 70 years of age in the United States and is often unreported (Green and Kodish, 2009; Hillman, 2008). It occurs more frequently in older men, but it occurs in younger men as well (Lindau et al., 2007). Risk factors are similar to those for heart disease (i.e., diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, hypothyroidism, chronic renal failure, smoking, obesity, alcohol abuse, and lack of exercise). The etiology of ED is often multifactorial. Neurogenic problems, medications, or endocrine or psychogenic factors can cause it. An age-related decrease in testosterone often results in decreased tone of the erectile tissues.

One of the most common problems affecting women of all ages is hypoactive sexual desire disorder (HSDD) (Kingsberg, 2011; West et al., 2008). Biological, organic, or psychosocial factors can contribute to the incidence of HSDD. Chronic medical conditions such as breast or gynecological cancers and hormonal fluctuations, pain, or depression and anxiety can contribute to a decreased interest in sexual intimacy.

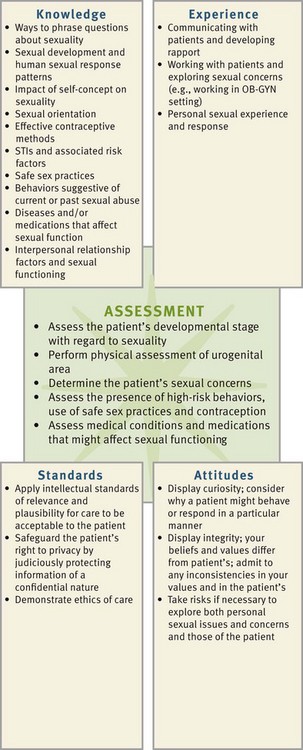

Critical Thinking

Successful critical thinking requires synthesis of knowledge, experience, information gathered from patients, critical thinking attitudes, and intellectual and professional standards. Nurses use clinical judgment to anticipate information needs, analyze assessment data, and make appropriate decisions regarding patient care. Fig. 34-2 shows how to use elements of critical thinking and patient assessment data to develop appropriate nursing diagnoses.

FIG. 34-2 Critical thinking model for sexuality assessment. OB-GYN, Obstetric-gynecological; STI, sexually transmitted infection.

In the case of sexuality, integrate knowledge from nursing and other disciplines. Have a thorough understanding of safe sex practices and the risks and behaviors associated with sexual problems to anticipate how to assess a patient and interpret findings. Use previous experiences to provide care for patients with sexual issues in a more reflective and helpful way. Patients have different customs and values from those of the nurse. Professional standards require respect for each patient as an individual. Critical thinking attitudes such as integrity require you to recognize when personal opinions and values are in conflict with those of the patient and to consider how to proceed in a way that is mutually beneficial.

Nursing Process

Apply the nursing process and use a critical thinking approach in your care of patients. The nursing process provides a clinical decision-making approach to help you develop and implement an individualized plan of care. Assess all relevant factors, including physical, psychological, social, and cultural, to determine a patient’s sexual well-being. The nursing role in addressing sexual concerns ranges from ongoing assessment to providing information, counseling, and referral. Keep in mind that nurses are not expected to have answers to all sexual issues and concerns identified.

Assessment

During the assessment process, thoroughly assess each patient and critically analyze findings to ensure that you make patient-centered clinical decisions required for safe nursing care.

Through the Patient’s Eyes

As in any patient assessment, it is important to understand the patient’s expectations regarding care. Questions such as “What would you like to have happen in regard to your sexual health problems?” and “What initial steps might you take?” help the patient identify desired outcomes. It is important to set aside personal views and consider the patient’s needs and preferences for care.

Factors Affecting Sexuality

In gathering a sexual history consider physical, functional, relationship, lifestyle, developmental, and self-esteem factors that influence sexual functioning. Sexual desire varies among individuals; some people want and enjoy sex every day, whereas others want sex only once a month, and still others have no sexual desire and are quite comfortable with that fact. Sexual desire becomes an issue if the person wants to satisfy sexual desire more often, if he or she believes that it is necessary to measure up to some cultural norm, or if there is a discrepancy between the sexual desires of the partners in a relationship.

Ask patients to describe factors that typically influence their sexual desire. Knowing the patients’ medical history and probing for information is helpful. For example, minor illness, medications, and fatigue often decrease sexual desire. Lifestyle factors such as the use or abuse of alcohol, lack of sleep, lack of time, or the demands of caring for a new baby are other influencing factors. For example, working parents sometimes feel so overburdened that they perceive sexual advances from a partner as an additional demand on them. Confirm factors that potentially affect sexual desire and determine with the patient the extent to which sexual function is impaired.

Self-concept issues (see Chapter 33), including identity, body image, role performance, and self-esteem, affect a patient’s sexuality. Consider how these factors relate to the patient’s condition. For example, poor body image associated with chronic disease magnifies feelings of rejection. This often results in diminished or absent sexual desire. Problems with a person’s self-esteem frequently lead to conflicts involving sexuality. Patients who experience negative feelings often suppress sexual feelings when they have not developed a healthy sense of a sexual self. Low sexual self-esteem negatively affects a person’s self-concept.

Issues in a relationship often affect sexual desire. After the initial glow of a new relationship has faded, some couples find that they have major differences in their values or lifestyles. Ask couples to describe how close they feel to each other and how often they interact on an intimate level. Assess communication patterns between sexual partners to determine sexual satisfaction within a relationship.

Sexual Health History

Most patients want to know how medications, treatments, and surgical procedures influence their sexual relationship even though they often do not ask questions. With experience nurses recognize that most patients welcome the opportunity to talk about their sexuality, especially when they are experiencing difficulties. The PLISSIT assessment model helps nurses discuss sexuality with patients in a relaxed, matter-of-fact manner (Wallace, 2008) (Box 34-4).

Incorporate assessment questions related to sexuality in the nursing history (Box 34-5). Using an opening statement puts the patient at ease when introducing these questions (e.g., “Sex is an important part of life, and a person’s health status often affects sexuality. Many people have questions and concerns about their sexual health. What questions or concerns do you have now?”). Use knowledge of developmental stages to determine which areas are likely to be important for the patient. For example, when gathering a sexual history from an older adult, it is important to keep in mind that some have difficulty discussing intimate details with health care providers.

Nurses who conduct sexual assessments of children and adolescents face special challenges. Use language that is accurate and that the child or adolescent understands. Also promote normal development, avoid minimizing problems, and screen for sexual concerns while making the child or adolescent feel at ease. The sexual counseling of minors raises ethical and legal issues regarding the patient’s rights to health care and education on the one hand and the parents’ or guardian’s right to supervise information on the other. Children and adolescents frequently respond when they know that having questions related to sexuality is normal. Being open, positive, and interested when introducing sexual questions is helpful.

In light of the prevalence of domestic violence and sexual abuse, questions relating to abusive relationships are important. Address these questions in private. Recognizing both subjective and objective signs and symptoms of abuse in children and adults aids in identification of this too-common problem (Table 34-1).

TABLE 34-1

Signs and Symptoms That Indicate Possible Current Sexual Abuse or a History of Sexual Abuse

Data from Hockenberry MJ, Wilson D: Wong’s essentials of pediatric nursing, ed 8, St Louis, 2009, Elsevier; Davidson MR, London ML, Ladewig PA: Olds’ Maternal-newborn nursing & women’s health across the lifespan, ed 8, Upper Saddle River, NJ, 2008, Pearson Prentice Hall; Ball JW, Bindler RC: Pediatric nursing caring for children, ed 4, Upper Saddle River, NJ, 2008, Pearson Prentice Hall.

Some individuals are too embarrassed or do not know how to ask sexual questions directly. Look for clues that a person has questions. For example, a patient expresses concern about how his or her partner will respond now or makes a sexual comment or joke. Observing for and listening to concerns about sexuality take practice. With experience a nurse develops skill in clarifying and paraphrasing to help individuals express sexual concerns. By including sexuality in the nursing history, the nurse acknowledges that sexuality is an important component of health and creates an opportunity for the person to discuss sexual concerns.

Sexual Dysfunction

Many illnesses, injuries, medications, and aging changes have a negative effect on sexual health. Sexual dysfunction is either temporary or permanent. Apply knowledge about conditions that frequently cause sexual dysfunction while assessing a patient’s risks (see Box 34-3). Awareness of the possible effects of physical problems, altered self-concept, medications, and the factors addressed thus far on sexual functioning helps in conducting a thorough assessment. Some patients bring up the topic of sexual dysfunction. Other times issues become evident as the patient answers other nursing history questions.

Physical Assessment

The physical examination is important in evaluating the cause of sexual concerns or problems and usually provides the best opportunity to teach an individual about sexuality. In examining a woman’s breasts and the external and internal genitalia, a nurse has the opportunity to assess the woman’s reaction, answer questions, and provide information about the examination of anatomical and physiological structures. For example, a nurse teaches a woman how to perform breast self-examination during physical assessment (see Chapter 30). During physical assessment of the genitalia, he or she teaches men how to perform testicular self-examination (see Chapter 30). Knowledge of normal scrotal anatomical structures helps men detect signs of testicular cancer. Instruct both men and women on signs and symptoms of STIs during the examination when patients’ histories suggest risks for STIs.

Nursing Diagnosis

After completing an assessment and applying critical thought to the diagnostic process, select diagnoses applicable to the patient’s needs. Possible nursing diagnoses related to sexual functioning are listed here:

• Interrupted family processes

• Deficient knowledge (contraception/STIs)

• Ineffective sexuality pattern

Assessment data that signal a nursing diagnosis related to sexuality often include history of surgery of reproductive organs, changes in appearance or body image, a history of or current physical or sexual abuse, chronic illness, or developmental milestones such as puberty or menopause. To make a nursing diagnosis related to sexual dysfunction, consider anatomical, physiological, sociocultural, ethical, and situational issues thoroughly.

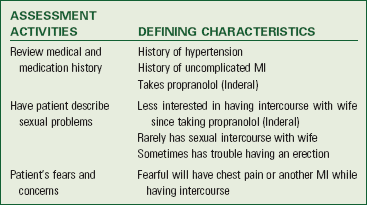

As with making any nursing diagnosis, clarify that the defining characteristics exist and that the patient perceives a problem or difficulty with regard to sexuality (Box 34-6). Determining the etiological or contributing factors helps in planning effectively and selecting the appropriate nursing interventions. For example, the nursing interventions appropriate for the nursing diagnosis of sexual dysfunction are different for different etiological factors. Sexual dysfunction related to misinformation about the risk of sexually transmitted infections requires counseling and education on how to maintain safe sexual practices. In contrast, patients who experience sexual dysfunction related to physical abuse need counseling and referral to community resources (e.g., crisis services and physical abuse support group).

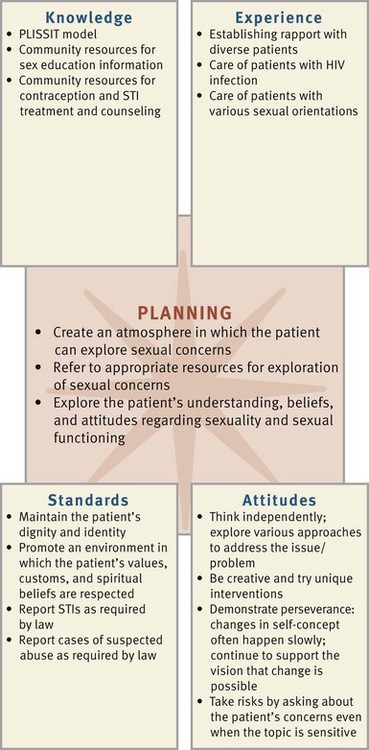

Planning

Synthesize information from multiple resources to develop an individualized plan of care (Fig. 34-3). Critical thinking ensures that the patient’s plan of care integrates all that a nurse knows about the individual and critical thinking elements as they pertain to sexuality. Professional standards are especially important to consider when developing a plan of care. Maintain a patient’s dignity and identity at all times. For example, to convey respect for the patient’s gender preferences, include a lesbian or gay partner in the plan to the degree that the patient wishes.

FIG. 34-3 Critical thinking model for sexuality planning. HIV, Human immunodeficiency virus; STI, sexually transmitted infection.

Develop an individualized plan of care for each nursing diagnosis (see the Nursing Care Plan). Set realistic goals and measurable outcomes with the patient. For example, a patient who has dyspareunia has a nursing diagnosis of sexual dysfunction related to decreased sexual desire. The nurse and patient develop a goal to report decreased anxiety and greater satisfaction with sexual activity within 1 month. Expected outcomes include that the patient will do the following:

• Consistently use a water-soluble lubricant before sexual intercourse within 1 week

• Discuss stressors that contribute to sexual dysfunction with partner within 2 weeks

• Identify alternative, satisfying, and acceptable sexual practices for self and partner within 4 weeks

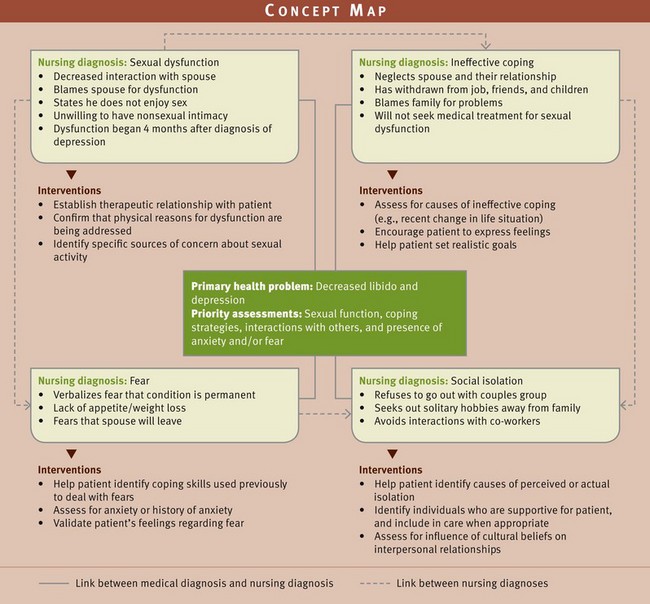

A concept map is another method that is useful in organizing patient care (Fig. 34-4). The concept map shows the relationship of a medical diagnosis (decreased libido and depression) to the four nursing diagnoses identified from the patient assessment data. It also shows the links and relationship to the nursing diagnosis and interventions appropriate for each diagnosis. For example, ineffective coping affects and contributes to social isolation; and as long as the patient has ineffective coping, the social isolation continues or perhaps worsens.

Setting Priorities

The care plan shows the goals, expected outcomes, and interventions for a patient experiencing sexual dysfunction. Nursing interventions for patients with sexual concerns focus on supporting the patient’s need for intimacy and sexual activity. Patients often feel overwhelmed and hopeless about returning to the level of previous sexual functioning. They usually need time to adapt to physical and psychosocial changes that affect their sexuality and sexual health.

The priority in addressing needs related to sexuality includes establishing a therapeutic relationship so the patient feels comfortable in discussing issues related to sexuality. Look for strengths in both the patient and the family while providing education and access to resources to turn limitations into strengths. Patient teaching communicates the normalcy of feelings following certain situations (e.g., the diagnosis of a chronic illness or the loss of a body part). The nurse determines the patient’s needs and plans accordingly.

The patient’s current problems and needs help the nurse determine the priorities related to the patient’s sexual health. Priorities for sexual health often include resuming sexual activities. For example, if the patient is recovering from a mastectomy and is having problems resuming an intimate relationship with her spouse because of problems related to body image, the nurse helps her adapt to and cope with the changes in her body image associated with the mastectomy. Once the patient’s issues related to body image are resolved, she is able to restore intimacy with her spouse and address her sexual health needs.

Teamwork and Collaboration

Planning in the area of sexuality often includes collaboration with other health care providers and referrals to community resources (Box 34-7). Nurses generally raise awareness of sexual issues, help to clarifying concerns, and/or provide information. Nurses who have specialized education in sexual functioning and counseling provide more intensive sex therapy. It is necessary to understand the limits of your knowledge base and include other health care providers such as sex therapists, clinical psychologists, and social workers as appropriate to meet patients’ needs for sexual health. For example, conflicts in marriage usually require intensive treatment with a mental health professional or certified sex therapist. For the woman who is currently in an abusive relationship, the nurse collaborates with special women’s shelters that provide counseling and serve as a safe place for her while further plans are made.

Implementation

As a nurse, promote sexual health as a component of overall wellness by identifying patients at increased risk (Box 34-8), providing appropriate information, helping individuals gain insight into their problems, and exploring methods to deal with them effectively.

Health Promotion

Helping patients maintain or gain sexual health involves consideration of factors that influence sexual satisfaction. Educate patients about sexual health, including measures for contraception, safe sex practices, and prevention of STIs. Regular breast self-examinations, mammograms, and Papanicolaou (Pap) smears are important sexual health measures for women; testicular self-examinations are important for men. Offer the HPV vaccine to males and females who are between 9 and 26 years of age. The vaccine is safe for girls as young as 9 years old and is recommended for females ages 13 to 26 if they have not already completed the three required injections. Booster doses currently are not recommended. The vaccine is most effective if administered before sexual activity or exposure (CDC, 2010b; Palefsky, 2010).

Exploring an individual’s values, discussing levels of satisfaction, and providing sex education require therapeutic communication skills. Structure the environment and timing to provide privacy, comfort, and uninterrupted time (Wallace, 2008). For example, when discussing methods of contraception with a woman, provide education in a private area with the patient fully dressed rather than in the examination room when the patient is only partially clothed.

Topics of education vary and often are related to the patient’s developmental level. For example, a nurse talks to school-age children regarding the appearance of breast buds or pubic hair. When discussing sexual health with patients of childbearing age, always consider the patient’s cultural and religious beliefs regarding contraception. The discussion includes the desire for children, usual sexual practices, and acceptable methods of contraception. Nurses review all methods of contraception to allow patients to make informed decisions.

Major developmental crises (e.g., puberty, climacteric, or menopause) prompt education about sexuality. Situational crises such as a life change with pregnancy, illness, extreme financial stress, placement of a spouse in a nursing home, or loss and grief affect sexuality. Effects can last for days, months, or years and are often minimized when the individual is prepared for possible changes in sexual functioning.

Demonstrate recognition, acceptance, and respect for an older adult’s sexuality by displaying a willingness to openly discuss sex and sexuality-related concerns. Strategies that enhance sexual functioning include the following (Kautz and Upadhyaya, 2010):

• Plan sexual activity for times when the couple feels rested.

• Take pain medication if needed before sexual intercourse.

• Use pillows and alternate positioning to enhance comfort.

• Encourage touch, kissing, hugging, and other tactile stimulation.

• Communicate concerns and fears with partner and health care provider.

Individuals who have more than one sex partner or whose partner has other sexual experiences need to learn about safe sex practices. Provide information about STI symptoms and transmission, use of condoms, and risky sexual activities (e.g., trauma from penile-anal sex). To prevent HIV infection, teach patients to avoid having multiple sex partners and use condoms to reduce the risk of HIV/AIDS. Role play is useful in helping a person learn to say no or negotiate with a partner to use a condom (Box 34-9). Also teach patients to avoid the use of IV drugs. If people do use IV drugs, tell them to avoid sharing needles with others and to always use new needles. When discussing safe sex, consider patients’ physical and emotional health.

Encourage patients to have regular health examinations to maintain sexual health. Often asymptomatic STIs are diagnosed during a physical examination with appropriate laboratory work. Annual health examinations provide an opportunity to discuss contraception and safe sex practices. However, some people do not routinely seek annual health examinations. Barriers to health screenings include cultural beliefs, low socioeconomic status, and low health literacy (Hogben and Leichliter, 2008; Shaw et al., 2009). Consider cultural implications as well. For example, Arab women frequently do not have breast examinations, mammograms, and cervical cancer screening because of religious and cultural beliefs about modesty (Cohen and Azaiza, 2010). Develop a therapeutic relationship with patients and provide culturally sensitive education that is written at an appropriate reading level (see Chapter 25). Encourage patients to find health care providers that they can trust and help patients who are uninsured or underinsured locate resources that can help them pay for important sexual health screenings (Hogben and Leichliter, 2008).

Acute Care

Illness and surgery create situational stressors that often affect a person’s sexuality. During periods of illness individuals experience major physical changes, the effects of drugs or treatments, the emotional stress of a prognosis, concern about future functioning, and separation from significant others. Never assume that sexual functioning is not a concern merely because of an individual’s age or severity of prognosis. After identifying concerns, address them in the context of his or her value system.

When a patient identifies sexual concerns, initiate discussion and education appropriately. Help patients to anticipate how their illness or disease will change over time and the adjustments that will be necessary to achieve sexual fulfillment.

Restorative and Continuing Care

Frequently nurses establish relationships with couples that encourage honest and open discussions about sexual health during restorative or continuing care. Address needs by taking a sexual health history and implementing a basic model such as PLISSIT to provide options for patients (see Box 34-4). Assessment and management of sexual concerns are important when promoting sexual intimacy and providing closeness and closure between partners at the end of life.

In the home environment it is important to provide information on how an illness limits sexual activity and give ideas for adapting or facilitating sexual activity. Interventions range from giving permission for a partner to lie in bed and hold a patient to coordinating nursing care and medications to provide opportunity for privacy and intimacy. Often nurses help individuals create an environment that is comfortable for sexual activity in the home. This sometimes involves making recommendations for ways to arrange the bedroom to accommodate physical limitations. For example, some individuals who are in a wheelchair prefer being able to move the chair close to the side of the bed at an angle that allows for more ease in touching and caressing. Suggestions regarding how to accommodate barriers such as Foley catheters or drainage tubes contribute to sexual activity.

In the long-term care setting facilities need to make proper arrangements for privacy during residents’ sexual experiences (Frankowski and Clark, 2009). The ideal situation is to set up a pleasant room that is used for a variety of activities that the resident is able to reserve for private visits with a spouse or partner. If this is not possible, make arrangements for the roommate of a patient to be somewhere else to allow a couple time alone. Never leave patients alone in a situation in which they can injure themselves.

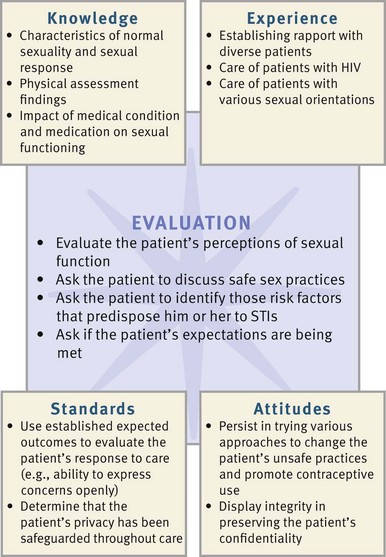

Evaluation

Evaluate patient responses to nursing interventions to determine if goals and outcome criteria have been met (Fig. 34-5). Critical thinking ensures that the nurse applies what is known about sexuality and the patient’s unique situation.

FIG. 34-5 Critical thinking model for sexuality evaluation. HIV, Human immunodeficiency virus; STI, sexually transmitted infection.

Have follow-up discussions with the patient or partner to determine whether goals and outcomes have been achieved. Sexuality is felt more than observed, and sexual expression requires an intimacy that is not amenable to observation. Therefore ask patients questions about risk factors, sexual concerns, and their level of satisfaction. Observe behavioral cues such as eye contact, posture, and extraneous hand movements that indicate comfort or suggest continued anxiety or concern as topics are addressed. Anticipate the need to modify expectations with the individual and partner when evaluating outcomes. Sometimes a nurse needs to establish more appropriate time frames in which to achieve the target goals. Ask patients to define what is acceptable and satisfying while considering the partner’s level of sexual satisfaction.

Patient Outcomes

When outcomes are not met, begin to ask questions to determine appropriate changes in interventions. Examples of questions include the following:

• What other questions do you have about your sexual health?

• Did you experience less pain during sexual intercourse after taking your pain medication?

• Which positions did you find most comfortable when you had sexual intercourse? Which positions were most awkward?

• What barriers are preventing you from discussing your feelings and fears with your partner?

Key Points

• Sexuality is related to all dimensions of health; therefore address sexual concerns or problems while providing routine nursing care.

• Sexuality is a part of each individual’s identity and includes biological sex, gender identity, gender role, and sexual partner preference.

• Attitudes toward sexuality vary widely. Religious beliefs, values of society, the media, the family, and other factors all influence it.

• Nurses’ attitudes toward sexuality vary and often differ from those of patients; be sensitive to patients’ sexual preferences and needs.

• Sexual development begins in infancy and involves some level of sexual behavior or growth in all developmental stages.

• The physiological sexual response changes with aging, but aging does not lead to diminished sexuality.

• Sexual health contributes to an individual’s sense of self-worth and positive interpersonal relationships.

• Sexual dysfunctions result from varied and complex etiologies.

• Interventions for sexual dysfunctions depend on the condition and the patient; they often include giving information, teaching specific exercises, improving communication between partners, and referral to a knowledgeable professional.

• Sexual biases, comfort with touching genitalia, desire for future fertility, financial status, ability to plan sexual contact, and ability to communicate with the sex partner all affect the choice and use of effective contraceptive methods.

• Include a brief review of sexuality whenever assessing a patient’s level of wellness.

• Most nursing interventions that enhance sexual health require providing education.

• Evaluate outcomes of care by talking with patients regarding satisfaction with sexual functioning and through observations of nonverbal behaviors that suggest anxiety. Include the partner when appropriate.

Clinical Application Questions

Preparing for Clinical Practice

1. Mr. Clements returns to see the advanced practice nurse (APN) in his cardiologist’s office for a routine visit. During the visit the APN plans to assess Mr. Clements’ sexuality. What can the APN do to help Mr. Clements feel comfortable in discussing his sexuality? Develop an opening statement that would be effective in decreasing his anxiety about discussing this private aspect of his life.

2. During the office visit Mr. and Mrs. Clements state that, although they are able to engage in sexual intercourse, it is taking both of them longer to reach orgasm. Explain why they are experiencing this change and describe at least three strategies that they could use to enhance their sexual functioning.

3. Mrs. Clements vocalizes concern about continuing sexual activity because Mr. Clements sometimes becomes short of breath during intercourse. She also says he seems to have less energy by the end of the day than before the MI. Using the PLISSIT model, give two examples of specific suggestions that the APN might give to the couple.

![]() Answers to Clinical Application Questions can be found on the Evolve website.

Answers to Clinical Application Questions can be found on the Evolve website.

Are You Ready to Test Your Nursing Knowledge?

1. The nurse is providing education on sexually transmitted infections (STIs) to a group of adolescents. The nurse knows that further teaching is needed when one of the adolescents states:

1. “A vaccine is available to reduce infection from certain types of human papillomavirus.”

2. “I should be screened for an STI after I am with a new partner.”

3. “I know I’m not infected if I don’t have any symptoms such as discharge or sores.”

4. “A viral infection such as herpes or human papillomavirus cannot be treated with antibiotics.”

2. A 25-year-old patient is in the emergency department and states that she has had a cough and fever for the past 3 days. While performing a physical assessment, the nurse finds several bruises that are in various stages of healing and suspects that the patient possibly is a victim of sexual abuse. Which of the following is the nurse’s first action?

1. Refer the patient to a sexual counselor

2. Tell the patient about the safe house for women

3. A 26-year-old married woman recently discovered that she is pregnant and is at her first prenatal visit. While assessing the patient, the woman’s health nurse practitioner discovers that she has purulent vaginal discharge. The patient states, “It burns when I urinate, and I seem to have to go to the bathroom frequently.” Based on these symptoms, the nurse practitioner determines that further follow-up is needed because the patient:

1. Should be tested for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).

2. May have a sexually transmitted infection (STI) such as chlamydia.

4. A new graduate nurse is working in a rehabilitation center that specializes in the care of patients with spinal cord injuries (SCIs). The new graduate knows that sexual issues are common among patients with SCIs. Which of the following actions enhances the nurse’s comfort in discussing sexual issues with the patients? (Select all that apply.)

1. Clarifying personal values related to sexuality

2. Role playing discussion of sexual concerns with another nurse

3. Attending a conference to enhance knowledge about sexuality

4. Avoiding a discussion of sexual concerns until after completing new nurse orientation

5. The nurse is gathering a sexual history from a 68-year-old man in a nursing home. It is important for the nurse to keep in mind that:

1. Older adults are usually not part of a sexual minority group.

2. Older adults sometimes do not reveal intimate details.

3. Older men and women lose their interest in sex.

4. Older adults in nursing homes do not usually participate in sexual activity.

6. Certain cultural groups in the United States are disproportionately affected by diseases such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). The nurse understands that this is most likely caused by: (Select all that apply.)

1. Expectations about behavior by men or women in the culture.

2. Higher percentages of lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender individuals in the culture.

3. Genetic predisposition to the disease in the culture

4. Communication patterns and language practiced by the culture.

7. Since the majority of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) have few if any symptoms, it is important for the nurse to:

1. Encourage regular screenings in all sexually active individuals.

2. Provide information about contraception options.

3. Administer prescribed antibiotics for human papillomavirus (HPV) or genital herpes outbreaks.

8. Establishing trust and encouraging disclosure about sexuality are often facilitated if the nurse begins by asking the patient:

1. How often he or she has sexual intercourse.

2. To disrobe in preparation for the physical assessment.

9. A 15-year-old girl states that she is having unprotected intercourse with her boyfriend. She asks for more information about birth control methods. The nurse informs the patient that: (Select all that apply.)

1. Condoms or diaphragms must be used with each sexual encounter.

2. Hormonal methods offer little protection against sexually transmitted infections (STIs).

3. Barrier methods offer some protection against STIs.

4. Sterilization is an effective option that she should consider.

10. The nurse reviews the health history of a 24-year-old woman who indicates that she has had three new sexual partners since her previous examination 2 years ago. The nurse discusses the need for sexually transmitted infection (STI) screening with the patient even though she denies symptoms or discomfort. The nurse realizes that the most serious complication from untreated STIs in females is:

11. The nurse is providing education about condom use at a community clinic for older adults. Which of following statements demonstrates that the adults understand correct use of condoms? (Select all that apply.)

1. “I can use any kind of lubricant such as lotions or baby oil.”

2. “Before using the condom, I should check the package for damage or expiration.”

3. “I need to use a condom to help reduce the risk of sexually transmitted infections.”

4. “A good place to store condoms is in the bathroom so they don’t dry out.”

12. Which of the following represents a nonjudgmental approach when gathering a sexual health history?

1. How do you and your wife/husband feel about intimacy?

2. Do you have sex with men, women, or both?

13. A 54-year-old male patient who is being seen for an annual physical tells the nurse that he is having difficulty sustaining an erection. The nurse reviews his health history and notes no current health problems except medical treatment for depression. The nurse understands that:

1. A personal issue such as this is best addressed by the male physician during the examination.

2. Erectile dysfunction affects most men over the age of 50.

3. The patient needs to be screened for sexually transmitted infections (STIs).

4. Antidepressant medication may be affecting his sexual functioning.

14. The nurse at a community health center is teaching a group of menopausal women about normal changes in the female sexual response that occur with aging. The nurse knows that the information is understood when one of the women states that:

1. It’s normal for me to take longer to reach an orgasm.

2. I might experience chest pain or shortness of breath during intercourse.

3. It’s normal for me to lose interest in sexual relationships.

4. I won’t need to be concerned about contraception or sexually transmitted infections because of my age.

15. A school nurse is completing a health history on an adolescent female and notices several body piercings and tattoos. The student tells the nurse that she is planning to get more tattoos and piercings over the summer break. The nurse tells the student piercing and tattoos can:

Answers: 1. 3; 2. 2; 3. 2; 4. 1, 2, 3; 5. 2; 6. 1, 4; 7. 1; 8. 3; 9. 2, 3; 10. 3; 11. 2, 3; 12. 2; 13. 4; 14. 1; 15. 3.

References

Adams, MP, Holland, LN, Jr. Pharmacology for nurses: a pathophysiological approach, ed 3. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall; 2011.

Bowder, VR, Greenberg, CS. Children and their families, ed 2. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2010.

Brown, MT. LGBT aging and rhetorical silence. Sexuality Res Social Policy: J NSRC. 2009;6(4):65.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, United States Department of Health and Human Services (CDC/USDHHS), Sexually transmitted disease surveillance, 2008. Atlanta, Ga. November 2009. accessed from http://www.cdc.gov/std/stats08/trends.htm [Accessed September 12, 2011].

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Youth risk behavior surveillance—United States, 2009. MMWR 2010;59(SS-5):1. accessed from http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/pdf/ss/ss5905.pdf [Accessed September 12, 2011].

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, United States Department of Health and Human Services (CDC/USDHHS), Vaccine information statement (interim) human papilloma virus (HPV) Gardasil, 3/30/2010, 2010. accessed from http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/pubs/vis/downloads/vis-hpv-gardasil.pdf [Accessed September 12, 2011].

Edelman, CL, Mandle, CL. Health promotion throughout the life span, ed 7. St Louis: Mosby; 2010.

Frankowski, AC, Clark, LJ. Sexuality and intimacy in assisted living: residents’ perceptions and experiences. Sexuality Res Social Policy NRSC. 2009;6(4):25.

Gabelnick, HL, et al. Contraceptive research and development. In Hatcher RA, et al, eds.: Contraceptive technology, ed 19, New York: Ardent Media, 2009.

Giger, JN, Davidhizer, RE. Transcultural Nursing, ed 5. St Louis: Mosby; 2008.

Gorman, LM, Sultan, DF. The patient with sexual dysfunction. In Gorman L, ed.: Psychosocial nursing for general patient care, ed 3, Philadelphia: FA Davis, 2008.

Grimes, DA. Intrauterine devices. In Hatcher RA, et al, eds.: Contraceptive technology, ed 19, New York: Ardent Media, 2009.

Grimshaw-Mulcahy, LJ. Now I know my STDs. Part II: Bacterial and protozoal. J Nurse Pract. April, 2008;4(4):271.

Hayward, M, Tindale, R. Knowing your dydoe from your madonna: an emergency nurse guide to body piercing. Emerg Nurse. 2008;15(10):26.

Hillman, J. Sexual issues and aging within the context of work with older adult patients. Prof Psychol Res Pract. 2008;39(3):290.

Hogben, M, Leichliter, JS. Social determinants and sexually transmitted disease disparities. Sexually Transmitted Dis. 2008;35(suppl 12):S13. [DOI:10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31818d3cad].

Kautz, DD, Upadhyaya, RC. Enhancing sexual intimacy. In: Mauk KL, ed. Gerontological nursing: competencies for care. Sudbury, Mass: Jones & Bartlett; 2010:602.

Kingsberg, SA. Hypoactive sexual desire disorder: understanding the impact on midlife women. Female Patient. 2011;36(3):39.

Lowdermilk, DL, et al. Maternity nursing, ed 8. St Louis: Mosby; 2010. [p 190].

Marrazzo, JM, et al. Reproductive tract infections, including HIV and other sexually transmitted infections. In Hatcher RA, et al, eds.: Contraceptive technology, ed 19, New York: Ardent Media, 2009.

Mosher, WD, Jones, J. Use of contraception in the United States: 1982-2008, National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Stat. 23(29), 2010. [DOI: 0.1016/j.jmwh.2009.12.006].

Murphy, PA. Contraception and reproductive health. In: King TL, Brucker MC, eds. Pharmacology for women’s health. Sudbury, Mass: Jones & Bartlett, 2011.

Palefsky, JM. Human papillomavirus-related disease in men: not just a women’s issue. J Adolesc Health. 2010;46:S12.

Paul, M, Stewart, FH. Abortion. In Hatcher RA, et al, eds.: Contraceptive technology, ed 19, New York: Ardent Media, 2009.

Shaw, SJ, et al. The role of culture in health literacy and chronic disease screening and management. J Immmigr Minor Health. 2009;11(6):460.

Steinke, EE, Jaarsma, T. Impact of cardiovascular disease on sexuality. In: Moser D, Riegel B, eds. Cardiac nursing: a companion to Braunwald’s heart disease. St Louis: Saunders; 2008:241.

Stilos, K, et al. Addressing the sexual health needs of patients with gynecologic cancers. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2008;12(3):457. [DOI:10.1188/08.CJON.457-463].

Wallace, MA. Assessment of sexual health in older adults. Am J Nurs. 2008;108(7):52.

Warner L, Steiner MJ, In Hatcher RA, et al, eds. Contraceptive technology, ed 19, New York: Ardent Media, 2009.

Williamson, C. Providing care to transgender persons: a clinical approach to primary care, hormones, and HIV management. J Nurses AIDS Care. 2010;21(3):221.

World Health Organization, Gender and human rights: sexual health, 2010. accessed from http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/topics/gender_rights/sexual_health/en/ [Accessed September 12, 2012].

Young-Bruehl, E. Sexual diversity in cosmopolitan perspective. Studies Gender Sexuality. 2010;11:1.

Research References

Cohen, M, Azaiza, F. Increasing breast examinations among Arab women using a tailored culture-based intervention. Behav Med. 2010;36:92.

Doty, ND, et al. Sexuality-related social support among lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth. J Youth Adolesc. 2010;39:1134. [DOI:10.1007/s10964-010-9566-x].

Elkington, KS, Bauermeister, JA, Zimmerman, MA. Psychological distress, substance abuse, and HIV/STI risk behaviors among youth. J Youth Adolesc. 2010;39:514. [DOI:10.1007/s10964-010-9524-7].

Fantasia, HC. Adolescent sexual decision making: a review of the literature. Am J Nurse Pract. 2009;13(11/12):22.

Fredriksen-Goldsen, KI, Muraco, A. Aging and sexual orientation: a 25-year review of the literature. Res Aging. 2010;32(2):372. [DOI:10.1177/0164027509360355].

Green, R, Kodish, S. Discussing a sensitive topic: nurse practitioners’ and physician assistants’ communication strategies in managing patients with erectile dysfunction. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2009;21:698.

Koch, JR, et al. Body art, deviance, and American college students. Social Sci J. 2010;47:151.

Lescano, CM, et al. Cultural factors and family-based HIV prevention intervention for Latino youth. J Pediatr Psychol. 2009;34(10):1041.

Lindau, ST, Gavrilova, N. Sex, health and years of sexually active life gained due to good health: evidence from two US population-based cross-sectional surveys of aging. Br Med J. 2010;340:c810. [DOI:10.1136/bmj.c810].

Lindau, ST, et al. A study of sexuality and health among older adults in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:762.

Murtagh, J. Female sexual function, dysfunction, and pregnancy: implications for practice. Am College Nurse-Midwives. 2010;55(5):438.

Ortiz, ME, Croxatto, HB. Copper-T intrauterine device and levonorgestrel intrauterine system: biological basis of their mechanism of action. Contraception. 2007;75(suppl):16.

Rivardo, MG, Keelan, CM. Body modifications, sexual activity, and religious practices. Psychol Rep. 2010;106(2):467.

Shifren, JL, et al. Sexual problems and distress in United States women: prevalence and correlates. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112:970.

Smith, KP, Christakis, NA. Association between widowhood and risk of diagnosis with a sexually transmitted infection in older adults. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(11):2055.

West, SL, et al. Prevalence of low sexual desire and hypoactive sexual desire disorder in a nationally representation sample of US women. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(13):1441.

Wohl, AR, et al. Factors associated with late HIV testing for Latinos diagnosed with AIDS in Los Angeles. AIDS Care. 2009;21(9):1203.