Health Assessment and Physical Examination

• Discuss the purposes of physical assessment.

• Discuss how cultural diversity influences a nurse’s approach to and findings from a health assessment.

• List techniques for preparing a patient physically and psychologically before and during an examination.

• Describe interview techniques used to enhance communication during history taking.

• Make environmental preparations before an examination.

• Identify data to collect from the nursing history before an examination.

• Demonstrate the techniques used with each physical assessment skill.

• Discuss normal physical findings in a young, middle-age, and older adult.

• Discuss ways to incorporate health promotion and health teaching into the examination.

• Identify ways to use physical assessment skills during routine nursing care.

• Describe physical measurements made in assessing each body system.

• Identify self-screening examinations commonly performed by patients.

• Identify preventive screenings and the appropriate age(s) for each screening to occur.

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Potter/fundamentals/

The health assessment and physical examination are the first steps toward providing safe and competent nursing care. The nurse is in a unique position to determine each patient’s current health status, distinguish variations from the norm, and recognize improvements or deterioration in his or her condition. As a nurse, you must be able to recognize and interpret each patient’s behavioral and physical presentation. By performing health assessments and physical examinations, you will identify health patterns and evaluate each patient’s response to treatments and therapies.

Nurses gather assessment data about patients’ past and current health conditions in a variety of ways, using a comprehensive or focused approach, depending on the patient situation. Assessments are performed at health fairs, at screening clinics, in a health provider’s office, in acute care agencies, or in patients’ homes. Depending on the outcome of an assessment, a nurse considers evidence-based recommendations for care based on a patient’s values, the health provider’s clinical expertise, or own personal experience.

A complete health assessment involves a nursing history (see Chapter 16) and behavioral and physical examination. Through the health history interview you gather subjective data about a patient’s condition. You obtain objective data while observing a patient’s behavior and overall presentation. You identify additional objective data through a head-to-toe body system review during the physical examination. Your clinical judgments are based on all of the gathered data to create a plan of care for each situation. With accurate data you create a patient-centered care plan, identifying the nursing diagnoses, desired patient outcomes, and nursing interventions. Continuity in health care improves when you evaluate a patient by making ongoing, objective, and comprehensive assessments.

Purposes of the Physical Examination

A physical examination is conducted as an initial evaluation in triage for emergency care; for routine screening to promote wellness behaviors and preventive health care measures; to determine eligibility for health insurance, military service, or a new job; or to admit a patient to a hospital or long-term care facility. After considering the patient’s current condition, a nurse selects a focused physical examination on a specific system or area. For example, when a patient is having a severe asthma episode, the nurse first focuses on the pulmonary and cardiovascular systems so treatments can begin immediately. When the patient is no longer at risk for a bad outcome or injury, the nurse performs a more comprehensive examination of other body systems.

For patients who are hospitalized, a nurse integrates the collection of physical assessment data during routine patient care, validating findings with what is known about the patient’s health history. For example, on entering a patient’s room a nurse may notice behavioral patient cues that indicate comfort, anxiety, or sadness; assess the skin during the bed bath; or assess physical movements and swallowing abilities while administering medications. Use physical examination to do the following:

• Gather baseline data about the patient’s health status.

• Support or refute subjective data obtained in the nursing history.

• Identify and confirm nursing diagnoses.

• Make clinical decisions about a patient’s changing health status and management.

Cultural Sensitivity

Respect the cultural differences among patients from a variety of backgrounds when completing an examination. It is important to remember that cultural differences influence patient behaviors. Consider the patient’s health beliefs, use of alternative therapies, nutrition habits, relationships with family, and comfort with physical closeness during the examination and history. These factors will affect your approach as well as the type of findings you might expect.

Be culturally aware and avoid stereotyping on the basis of gender or race. There is a difference between cultural characteristics and physical characteristics. Learn to recognize common characteristics and disorders among members of ethnic populations within the community. It is equally important to recognize variations in physical characteristics such as in the skin and musculoskeletal system, which are related to racial variables. By recognizing cultural diversity, you show respect for each patient’s uniqueness, leading to higher-quality care and improved clinical outcomes (see Chapter 9).

Preparation for Examination

Physical examination is a routine part of a nurse’s patient assessment. In many care settings a head-to-toe physical assessment is required daily. You perform a reassessment when a patient’s condition changes as it improves or worsens. In some health care settings such as during a home health visit a focused physical examination is preferred. Proper preparation of the environment, equipment, and patient ensures a smooth physical examination with few interruptions. A disorganized approach causes errors and incomplete findings. Safety for confused patients should be a priority; never leave a confused or combative patient alone during an examination.

Infection Control

Some patients present with open skin lesions, infected wounds, or other communicable diseases. Use standard precautions throughout an examination (see Chapter 28). When an open sore or microorganism is present, wear gloves to reduce contact with contaminants. If a patient has excessive drainage or there is a risk of splattering from a wound, additional personal protective equipment such as an isolation gown or eye shield should be used. Follow agency hand hygiene policies before initiating and after completing a physical assessment.

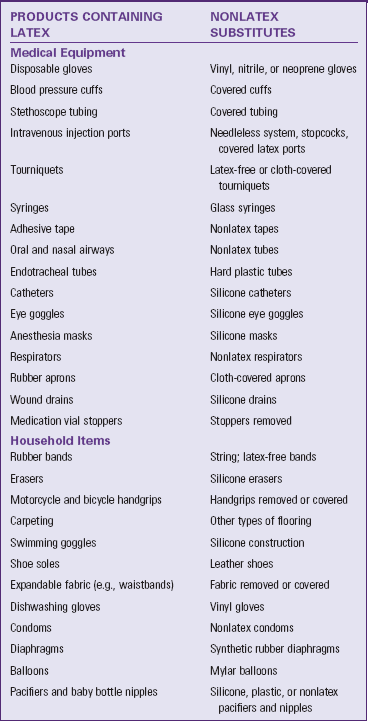

Although most health care agencies make nonlatex gloves available, it is your responsibility to identify latex allergies in patients and use equipment items that are latex free. By recognizing risk factors for latex allergies, the patient remains free of a natural rubber latex (NRL) allergy response. Two types of allergic responses appear with NRL. The most immediate is an immunological reaction type 1 response, for which the body develops antibodies known as immunoglobulin E that can lead to an anaphylactic response. Atopy occurs when there is an increased tendency for the body to form antibodies as a result of the immune response. The second is the allergic contact dermatitis type 4 response, which causes a delayed reaction that appears 12 to 48 hours after exposure (Bundesen, 2008). Both require prior exposure to the substance to which the body reacts. The severity of the response varies among individuals. Table 30-1 provides a short list of products that contain latex and suggests available alternatives.

TABLE 30-1

Products Containing Latex and Nonlatex Substitutes*

*This list is intended to provide examples of products and alternatives. It is not complete.

Modified from American Latex Allergy Association: Literature review on latex-food cross-reactivity, 1991-2006, 2011, http://www.latexallergyresources.org/topics/CrossReactiveAllergens.cfm. Accessed September 8, 2011; and Seidel HM et al: Mosby’s guide to physical examination, ed 7, St Louis, 2011, Mosby;

Environment

A respectful, considerate physical examination requires privacy. In the acute setting, nurses perform assessments in a patient’s room. Examination rooms are used in clinics or office settings. In the home the examination is performed in a space where privacy can be established such as the patient’s bedroom.

Examination spaces need to be well equipped for any procedures. Adequate lighting is necessary to properly illuminate body parts. The hospital patient room can be secured for privacy so patients are comfortable discussing their condition. Eliminate extra noise and take precautions to prevent interruptions from others. The room must be warm enough to maintain comfort.

Depending on the body part being assessed, it may be difficult to perform a selected assessment skill when a patient is in bed or on a stretcher. Special examination tables make positioning easier and body areas more easily accessible. By assisting patients on and off the examination table, injury can be avoided, and falls prevented. Examination tables can be uncomfortable; elevate the head of the table about 30 degrees. A small pillow helps with head and neck comfort. If the examination is completed in the patient room, raise the patient’s bed to be able to reach him or her more easily.

Equipment

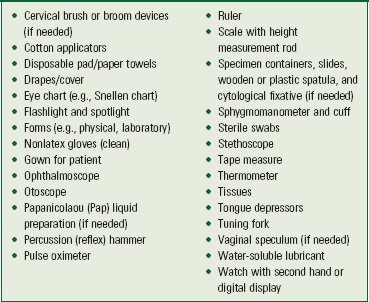

Perform hand hygiene thoroughly before handling equipment and starting an examination. Arrange any necessary equipment so that it is readily available and easy to use. Prepare equipment as appropriate (e.g., warm the diaphragm of the stethoscope between the hands before applying it to the skin). Be sure that equipment functions properly before using it (e.g., ensure that the ophthalmoscope and otoscope have good batteries and light bulbs). Box 30-1 lists typical equipment used during a physical examination.

Physical Preparation of the Patient

To show respect for a patient, ensure that physical comfort needs are met. Before starting, ask if the patient needs to use the restroom. An empty bladder and bowel facilitate examination of the abdomen, genitalia, and rectum. Collection of urine or fecal specimens occurs at this time if needed.

Physical preparation involves making certain that patient privacy is maintained with proper dress and draping. The patient in the hospital likely is wearing only a simple gown. In the clinic or health care provider’s office the patient needs to undress and usually is provided a disposable paper cover or paper gown. If the examination is limited to certain body systems, it is not always necessary for the patient to undress completely. Provide the patient privacy and plenty of time to undress to avoid embarrassment. After changing into the recommended gown or cover, the patient sits or lies down on the examination table with a light drape over the lap or lower trunk. Make sure that he or she stays warm by eliminating drafts, controlling room temperature, and providing warm blankets. Routinely ask if he or she is comfortable.

Positioning

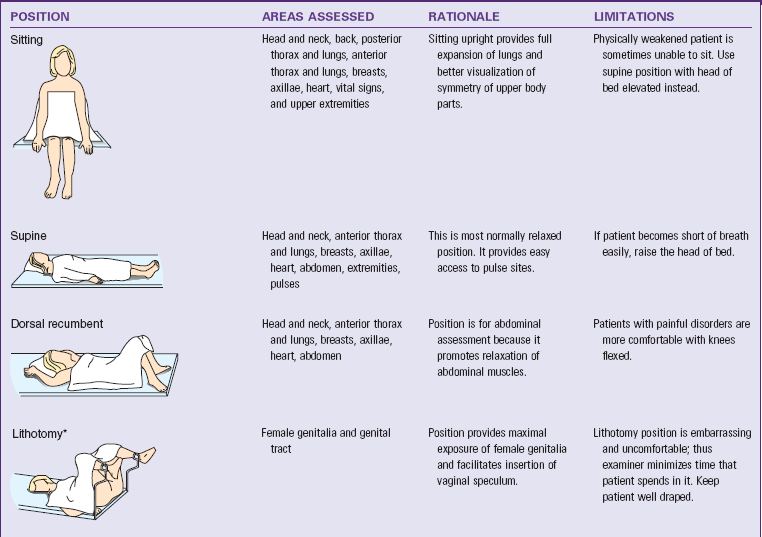

During the examination ask the patient to assume proper positions so body parts are accessible and he or she stays comfortable. Table 30-2 lists the preferred positions for each part of the examination and contains figures illustrating the positions. Patients’ abilities to assume positions depend on their physical strength, mobility, ease of breathing, age, and degree of wellness. After explaining the positions, help the patient to assume them. Take care to maintain respect and show consideration by adjusting the drapes so that only the area examined is accessible. During the examination a patient may need to assume more than one position. To decrease the number of position changes, organize the examination so all techniques requiring a sitting position are completed first, followed by those that require a supine position next, and so forth. Use extra care when positioning older adults with disabilities and limitations.

Psychological Preparation of a Patient

Many patients find an examination stressful or tiring, or they experience anxiety about possible findings. A thorough explanation of the purpose and steps of each assessment lets a patient know what to expect and how to cooperate. Adapt explanations to the patient’s level of understanding and encourage him or her to ask questions and comment on any discomfort. Convey an open, professional approach while remaining relaxed. A quiet, formal demeanor inhibits the patient’s ability to communicate, but a style that is too casual may cause him or her to doubt an examiner’s competence (Seidel et al., 2011).

Consider cultural or social norms when performing an examination on a person of the opposite gender. When this situation occurs, another person of the patient’s gender or a culturally approved family member needs to be in the room. By taking this step you demonstrate cultural awareness for a patient’s individual needs. As a side benefit, the second person acts as a witness to the conduct of the examiner and the patient should any question arise.

During the examination, watch the patient’s emotional responses by observing whether his or her facial expressions show fear or concern or if body movements indicate anxiety. When you remain calm, the patient is more likely to relax. Especially if the patient is weak or elderly, it is necessary to pace the examination, pausing at intervals to ask how he or she is tolerating the assessment. If the patient feels alright, the examination can proceed. However, do not force the patient to cooperate based on your schedule. Postponing the examination is advantageous because the findings may be more accurate when the patient can cooperate and relax.

Assessment of Age-Groups

It is necessary to use different interview styles and approaches to physical examination for patients of different age-groups. Your approach will vary with each group. When assessing children, show sensitivity and anticipate the child’s perception of the examination as a strange and unfamiliar experience. Routine pediatric examinations focus on health promotion and illness prevention, particularly for the care of well children who receive competent parenting and have no serious health problems (Josephson and AACAP Work Group, 2007). This examination focuses on growth and development, sensory screening, dental examination, and behavioral assessment. Children who are chronically ill or disabled and foster, foreign-born, or adopted children sometimes require additional examination visits. When examining children, the following tips help in data collection:

• Gather all or part of the history on infants and children from parents or guardians.

• Perform the examination in a nonthreatening area; provide time for play to become acquainted.

• Because parents sometimes think the examiner is testing them, offer support during the examination and do not pass judgment.

• Call children by their first name and address the parents as “Mr., Mrs., or Ms.” rather than by their first name unless instructed differently.

• Use open-ended questions to allow parents to share more information and describe more of the children’s problems. This also allows observation of parent-child interactions. You can interview older children, who often provide details about their health history and severity of symptoms.

• Treat adolescents as adults and individuals because they tend to respond best when treated as such.

• Remember that adolescents have the right to confidentiality. After talking with parents about historical information, speak alone with adolescents.

A comprehensive health assessment and examination of older adults includes physical data, developmental stage, family relationships, religious and occupational pursuits, and a review of the patient’s cognitive, affective, and social level (Kresevic, 2008). An important aspect is to assess the patient’s ability to perform basic activities of daily living (e.g., bathing, grooming) and complex instrumental activities of daily living (e.g., making phone call).

Throughout the examination recognize that with advancing age the body does not demonstrate obvious injury or disease as vigorously as younger patients and older adults do not always exhibit the expected signs and symptoms (Meiner, 2011). Characteristically older adults present with subtle or atypical signs and symptoms. Principles to follow during examination of an older adult include the following:

• Do not stereotype about aging patients’ level of cognition. Most older adults are able to adapt to change and learn about their health. Similarly most are reliable historians.

• Recognize that some older adults have sensory or physical limitations that affect how quickly they can be interviewed and examinations can be conducted. It might be necessary to plan for more than one examination session. Sometimes it helps to give patients an initial health questionnaire before they come to a clinic or office.

• Perform the examination with adequate space; this is especially important for patients with mobility aids such as a cane or walker.

• During the examination use patience, allow for pauses, and observe for details. Recognize normal physiological and behavioral changes that are characteristic of later life.

• Certain types of health information are stressful for older patients to give. Some view illness as a threat to independence and a step toward institutionalization.

• Be aware of the location of the closest bathroom facility in case the patient has an urgent need to eliminate.

• Be alert to signs of increasing fatigue such as sighing, grimacing, irritability, leaning against objects for support, and drooping head and shoulders.

Organization of the Examination

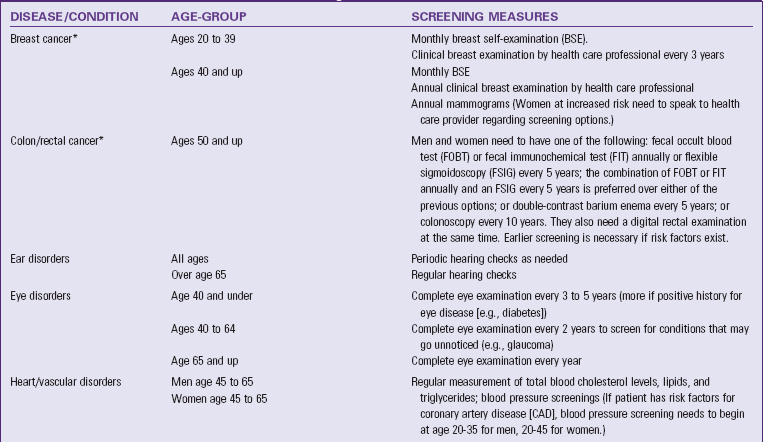

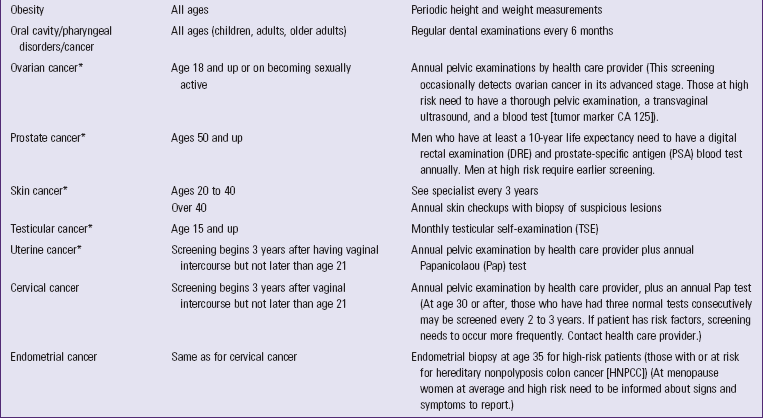

You will conduct a physical examination by assessing each body system. Use judgment to ensure that an examination is relevant and includes the correct assessments. Patients with focused symptoms or needs require only parts of an examination; thus, when a patient comes to a clinic with symptoms of a severe chest cold, a neurological assessment should not be required. A patient entering the emergency department with acute abdominal symptoms requires assessment of the body systems most at risk for being abnormal. However, when a patient is admitted to the hospital, you will perform a complete examination at the time of admission and at least once each day. Agency guidelines may define the components of a complete examination (see agency policy). A patient in the community seeks screening for specific conditions, often dependent on the patient’s age or health risks listed in Table 30-3.

TABLE 30-3

Recommended Preventive Screenings

*Data from American Cancer Society: Cancer facts and figures 2011, Atlanta, 2011, The Society; website for further information on preventative screenings: Guide to clinical preventive services, AHRQ Publication No. 05-0570, Rockville, Md, 2011, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, http://www.ahrp.gov/.

Any physical examination should follow a systematic routine to avoid missing important findings. A head-to-toe approach includes all body systems, and the examiner recalls and performs each step in a predetermined order. For an adult the examination begins with an assessment of the head and neck and progresses methodically down the body to incorporate all body systems. The following tips help keep an examination well organized:

• Compare both sides of the body for symmetry. A degree of asymmetry is normal (e.g., the biceps muscles in the dominant arm are sometimes more developed than the same muscles in the nondominant arm).

• If the patient is seriously ill, first assess the systems of the body most at risk for being abnormal. For example, a patient with chest pain first undergoes a cardiovascular assessment.

• If the patient becomes fatigued, offer rest periods between assessments.

• Perform painful procedures near the end of an examination.

• Record assessments in specific terms in the electronic or paper record. A standard form allows for recording information in the same sequence that it is gathered.

• Use common and accepted medical terms and abbreviations to keep notes accurate, brief, and concise.

• Record quick notes during the examination to avoid delays. Complete any larger documentation notes at the end of the examination.

Techniques of Physical Assessment

The four techniques used in a physical examination are inspection, palpation, percussion, and auscultation.

Inspection

To inspect, carefully look, listen, and smell to distinguish normal from abnormal findings. To do so, you must be aware of any personal visual, hearing, or olfactory deficits. It is important to deliberately practice this skill and learn to recognize all of the possible pieces of data that can be gathered through inspection alone. Inspection occurs when interacting with a patient, watching for nonverbal expressions of emotional and mental status. Physical movements and structural components can also be identified in such an informal way. Most important, be deliberate and pay attention to detail. Follow these guidelines to achieve the best results during inspection:

• Make sure that adequate lighting is available, either direct or tangential.

• Use a direct lighting source (e.g., a penlight or lamp) to inspect body cavities.

• Inspect each area for size, shape, color, symmetry, position, and abnormality.

• Position and expose body parts as needed so all surfaces can be viewed but privacy can be maintained.

• When possible, check for side-to-side symmetry by comparing each area with its match on the opposite side of the body.

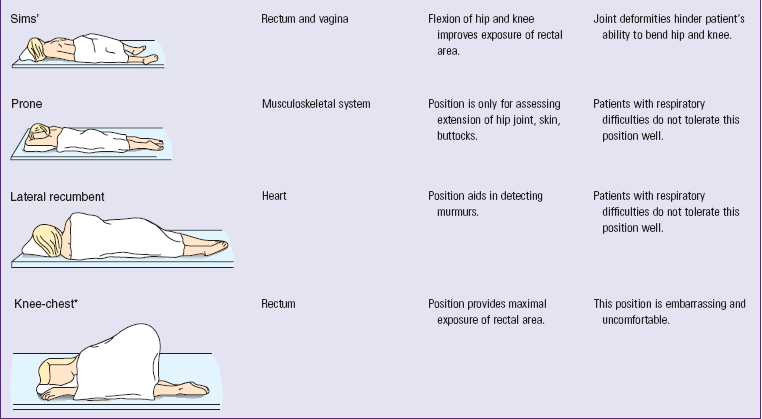

While assessing a patient, recognize the nature and source of body odors (Table 30-4). An unusual odor often indicates an underlying pathology. Olfaction helps to detect abnormalities that cannot be recognized by any other means. For example, when a patient’s breath has a sweet, fruity odor, assess for signs of diabetes. Continue to inspect various parts of the body during the physical examination. Palpation may be used concurrently with inspection, or it may follow in a more deliberate fashion.

Palpation

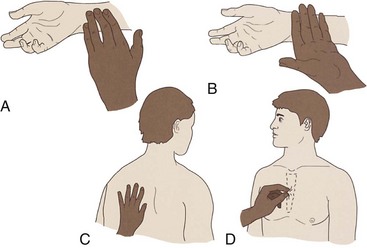

Palpation involves using the sense of touch to gather information. Through touch you make judgments about expected and unexpected findings of the skin or underlying tissue, muscle, and bones. For example, you palpate the skin for temperature, moisture, texture, turgor, tenderness, and thickness and the abdomen for tenderness, distention, or masses. Use different parts of the hand to detect different characteristics (Table 30-5). The palmar surface of the hand and finger pads is more sensitive than the fingertips and should be used to determine position, texture, size, consistency, masses, fluid, and crepitus (Fig. 30-1, A). Assess body temperature by using the dorsal surface or back of the hand (Fig. 30-1, B). The palmar surface of the hand and fingers (Fig. 30-1, C) is more sensitive to vibration. Measure position, consistency, and turgor by lightly grasping the body part with the fingertips (Fig. 30-1, D).

FIG. 30-1 A, Radial pulse is detected with the pads of fingertips, the most sensitive part of the hand. B, Dorsum of the hand detects temperature variations in skin. C, The bony part of the palm at the base of the fingers detects vibrations. D, Skin is grasped with the fingertips to assess turgor.

Touching the patient is a personal experience for both you and the patient. Display respect and concern throughout the examination. Before palpating consider the patient’s condition and ability to tolerate the assessment techniques, paying close attention to areas that are painful or tender. In addition, always be conscious of the environment and any threats to the patient’s safety.

Prepare for palpation by warming hands, keeping fingernails short and using a gentle approach. Palpation proceeds slowly, gently, and deliberately. The patient needs to be guided to relax and feel comfortable since tensed muscles make assessment more difficult. To promote relaxation, have him or her take slow, deep breaths and place both arms along the sides of the body. Ask the patient to point to more sensitive areas, watching for nonverbal signs of discomfort. Palpate tender areas last.

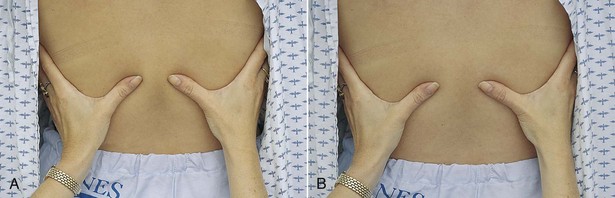

Two types of palpation are used for physical examination, light and deep. Light palpation is performed by placing the hand on the body part being examined; it also involves pressing inward about 1 cm ( inch). Light, superficial palpation of structures such as the abdomen gives the patient the chance to identify areas of tenderness (Fig. 30-2, A). Inquire about areas of tenderness and assess them further for potentially serious pathologies. Deep palpation is used to examine the condition of organs such as those in the abdomen (Fig. 30-2, B). Depress the area under examination approximately 4 cm (2 inches) (Seidel et al., 2011), using one or both hands (bimanually). When using bimanual palpation, relax one hand (sensing hand) and place it lightly over the patient’s skin. The other hand (active hand) helps apply pressure to the sensing hand. The lower hand does not exert pressure directly and thus remains sensitive to detect organ characteristics. For safety deep palpation should be observed by your clinical instructor when you first attempt the procedure.

inch). Light, superficial palpation of structures such as the abdomen gives the patient the chance to identify areas of tenderness (Fig. 30-2, A). Inquire about areas of tenderness and assess them further for potentially serious pathologies. Deep palpation is used to examine the condition of organs such as those in the abdomen (Fig. 30-2, B). Depress the area under examination approximately 4 cm (2 inches) (Seidel et al., 2011), using one or both hands (bimanually). When using bimanual palpation, relax one hand (sensing hand) and place it lightly over the patient’s skin. The other hand (active hand) helps apply pressure to the sensing hand. The lower hand does not exert pressure directly and thus remains sensitive to detect organ characteristics. For safety deep palpation should be observed by your clinical instructor when you first attempt the procedure.

Percussion

Percussion involves tapping the skin with the fingertips to vibrate underlying tissues and organs. The vibration travels through body tissues, and the character of the resulting sound reflects the density of the underlying tissue. The denser the tissue, the quieter the sound. By knowing how various densities influence sound, it is possible to locate organs or masses, map their edges, and determine their size. An abnormal sound suggests a mass or substance such as air or fluid within an organ or body cavity. The skill of percussion is used more often by advanced practice nurses than by nurses in daily practice at the bedside.

Auscultation

Auscultation involves listening to sounds the body makes to detect variations from normal. Some sounds such as speech and coughing can be heard without additional equipment, but a stethoscope is necessary to hear internal body sounds.

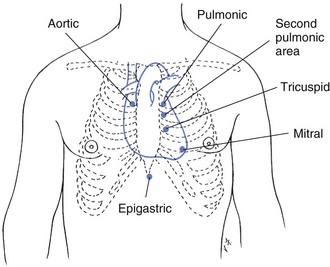

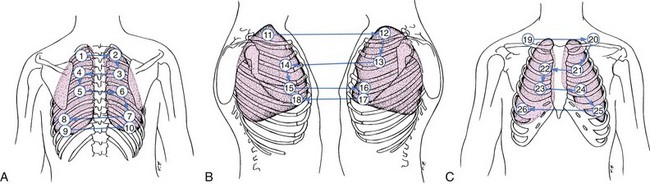

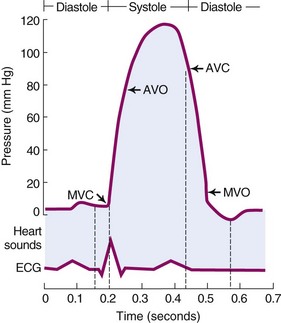

Internal body sounds are created by blood, air, or gastric contents as they move against the body structures. For example, normal heart sounds are created when the heart valves close, moving blood to the next portion of the cardiovascular system. Normal sounds for each body system are discussed later in this chapter. Learn to recognize abnormal sounds after learning normal variations. Becoming more proficient in auscultation occurs by knowing the types of sounds each body structure makes and the location in which the sounds are heard best.

To auscultate internal sounds you need to hear well, have a good stethoscope, and know how to use it properly. Nurses with hearing disorders can obtain stethoscopes with extra sound amplification. Chapter 29 describes the parts of the stethoscope and its general use. The bell is best for hearing low-pitched sounds such as vascular and certain heart sounds, and the diaphragm is best for listening to high-pitched sounds such as bowel and lung sounds.

By practicing with the stethoscope, you become proficient at using it and realize when sounds are clear and when there are extraneous sounds. Extraneous sounds created by rubbing against the tubing or chest piece interfere with auscultation of body organ sounds. By deliberately producing these sounds, you learn to recognize and disregard them during the actual examination. Box 30-2 contains ways to practice using and techniques for caring for the stethoscope. Describe any sound you hear using the following characteristics:

• Frequency indicates the number of sound wave cycles generated per second by a vibrating object. The higher the frequency, the higher the pitch of a sound and vice versa.

• Loudness refers to the amplitude of a sound wave. Auscultated sounds range from soft to loud.

• Quality refers to sounds of similar frequency and loudness from different sources. Terms such as blowing or gurgling describe the quality of sound.

• Duration means the length of time that sound vibrations last. The duration of sound is short, medium, or long. Layers of soft tissue dampen the duration of sounds from deep internal organs.

Auscultation requires concentration and practice. While listening, know which sounds are normally produced in certain parts of the body and what causes the sounds. Normal sounds will be discussed in each body system section of this chapter. After understanding the cause and character of normal auscultated sounds, it becomes easier to recognize abnormal sounds and their origins.

General Survey

When a patient first enters the examination room, observe his or her walk and general appearance and be attentive to his or her behavior and dress. A general survey, or appraisal, of the patient’s presentation and behavior provides information about characteristics of an illness, the patient’s ability to function independently, body image, emotional state, recent changes in weight, and developmental status. If there are abnormalities or problems, assess the affected body system more closely during the full examination.

General Appearance and Behavior

Assess appearance and behavior while preparing the patient for the examination. For this review include:

• Gender and race: A person’s gender affects the type of examination performed and the order of the assessments. Different physical features are related to gender and race. Certain illnesses are more likely to affect a specific gender or race (e.g., the incidence of skin cancer is more common in whites than in blacks, prostate cancer is higher in black men than in white men, and cancer of the bladder is four times higher in men than women) (American Cancer Society [ACS], 2011).

• Age: Age influences normal physical characteristics and a person’s ability to participate in some parts of the examination.

• Signs of distress: Sometimes obvious signs or symptoms indicate pain (grimacing, splinting painful area), difficulty breathing (shortness of breath, sternal retractions), or anxiety. Set priorities and examine the related physical areas first.

• Body type: Observe if the patient appears trim and muscular, obese, or excessively thin. Body type reflects the level of health, age, and lifestyle.

• Posture: Normal standing posture shows an upright stance with parallel alignment of the hips and shoulders. Normal sitting posture involves some degree of rounding of the shoulders. Observe whether the patient has a slumped, erect, or bent posture, which reflects mood or pain. Changes in older adult physiology often result in a stooped, forward-bent posture, with the hips and knees somewhat flexed and the arms bent at the elbows.

• Gait: Observe as the patient walks into the room or stands at the bedside (if the patient is ambulatory). Note whether movements are coordinated or uncoordinated. A person normally walks smoothly, with the arms swinging freely at the sides and the head and face leading the body.

• Body movements: Observe whether movements are purposeful, noting any tremors involving the extremities. Determine if any body parts are immobile.

• Hygiene and grooming: Note the patient’s level of cleanliness by observing the appearance of the hair, skin, and fingernails. Determine if his or her clothes are clean. Grooming depends on the patient’s cognitive and emotional function, daily or social activities, and occupation. Observe for excessive use of cosmetics or colognes that could indicate a change in self-perception.

• Dress: Culture, lifestyle, socioeconomic level, and personal preference affect the selection and wearing of clothing. However, you should assess whether or not the clothing is appropriate for the temperature, weather conditions, or setting. Depressed or mentally ill people may not be able to select proper clothing, and an older adult might tend to wear extra clothing because of sensitivity to cold.

• Body odor: An unpleasant body odor can result from physical exercise, poor hygiene, or certain disease states. Validate any odors that might indicate a health problem.

• Affect and mood: Affect is a person’s feelings as he or she appears to others. Patients express mood or emotional state verbally and nonverbally. Determine whether or not verbal expressions match nonverbal behavior and if the mood is appropriate for the situation. By maintaining eye contact you can observe facial expressions while asking questions.

• Speech: Normal speech is understandable and moderately paced and shows an association with the person’s thoughts. However, emotions or neurological impairment sometimes causes rapid or slowed speech. Observe whether the patient speaks in a normal tone with clear inflection of words.

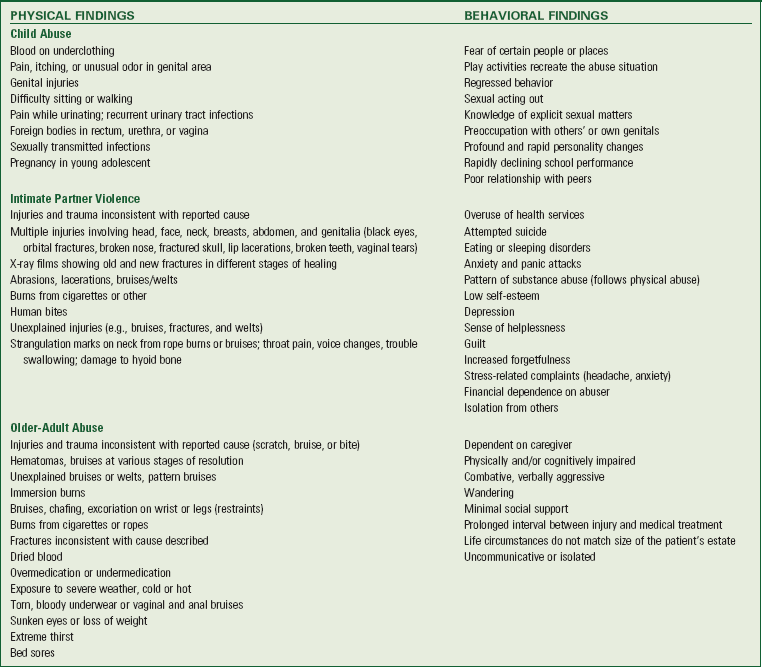

• Signs of patient abuse: During the examination observe if the patient fears his or her spouse or partner, a caregiver, a parent, or an adult child. Abuse of children, women, and older adults is a growing health problem. Consider any obvious physical injury or neglect as signs of possible abuse (e.g., evidence of malnutrition or presence of bruising on the extremities or trunk). Abuse occurs in many forms: physical, mental or emotional, sexual, social, and financial or economic. Observe the behavior of the individual for any signs of frustration, explanations that do not fit his or her physical presentation, or signs of injury. Most states mandate a report to a social service center when abuse or neglect is suspected (Box 30-3). It is difficult to detect abuse because victims often do not complain or report that they are in an abusive situation (Cohen et al., 2007). If abuse is suspected, find a way to interview the patient in private; patients are more likely to reveal any problems when the suspected abuser is absent from the room. It is imperative that you help the patient find safe housing or seek protection from the abuser since the risk for further abuse is high once the victim has reported it or tries to leave the abusive situation.

• Substance abuse: Unusual or inconsistent behavior may be an indicator of substance abuse, which can affect all socioeconomic groups. Although a single patient visit to a clinic does not always reveal the problem, unusual behaviors should be investigated further to reveal behaviors that should be confirmed with a well-focused history and physical examination. Always approach the patient in a caring and nonjudgmental way; substance abuse involves both emotional and lifestyle issues. Box 30-4 lists characteristics of patients who should be further assessed for potential substance abuse. The CAGE questionnaire provides a useful set of questions to guide assessment. CAGE is an acronym for the following:

• Have you ever felt the need to Cut down on your drinking or drug use?

• Have people Annoyed you by criticizing your drinking or drug use?

• Have you ever felt bad or Guilty about your drinking or drug use?

• Have you ever used or had a drink first thing in the morning as an Eye-opener to steady your nerves or feel normal?

If two or more of the CAGE questions are positive, be aware that substance abuse is likely and the patient needs guidance and encouragement to seek treatment. Among older adults risk factors for development of alcohol-related problems include chronic medical disorders, sleep disorders, social isolation, loneliness, bereavement, and acute or chronic pain. Older women appear to abuse alcohol more often than elderly men (Boyle and Davis, 2006).

Vital Signs

After completing the general survey, measure the patient’s vital signs (see Chapter 29). Measurement of vital signs is more accurate if completed before beginning positional changes or movements. If there is a chance that the vital signs are skewed when first measured, recheck them later during the rest of the examination. Pain, considered the fifth vital sign, should also be assessed.

Height and Weight

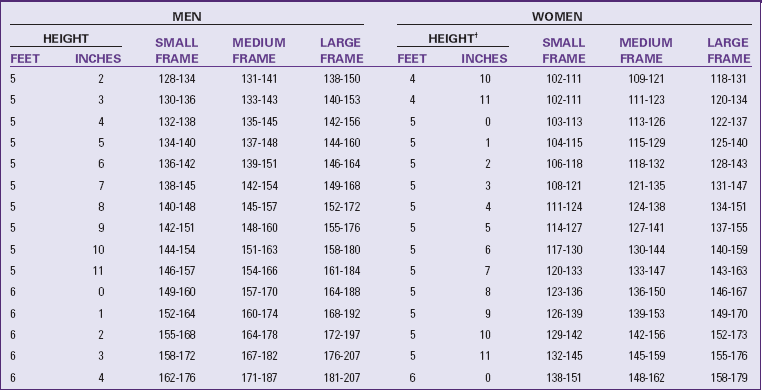

Height and weight reflect a person’s general health status. Standardized tables help reveal the normal expected adult weight for a given height (Table 30-6). Assess every patient to identify if he or she is at a healthy weight, overweight, or obese. Weight is routinely measured during health screenings, visits to physicians’ offices or clinics, and on admission to the hospital. Infants and children are measured for both height and weight at each health care visit to assess for healthy growth and development. If older adults are underweight, difficulty with feeding and other functional activities is a possibility. Measuring height and weight of older adults, along with obtaining a dietary history, shows risk factors for chronic diseases (Box 30-5).

TABLE 30-6

Height and Weight Table: Weights for Persons 25 to 59 Years According to Build*

*Indoor clothing weighing 5 pounds for men and 3 pounds for women.

Courtesy Metropolitan Life Insurance Company: Statistical bulletin, New York, 2010, Metropolitan.

Assess trends in weight changes compared with height for signs of poor health. Assessments screen for abnormal weight changes. A patient’s weight normally varies daily because of fluid loss or retention. However, a downward trend in a frail older adult indicates that there is a serious reduction in nutritional reserves. The nursing history helps to focus on possible causes for a change in weight (Table 30-7). Ask the patient to report current height and weight, along with a history of any substantial weight gain or loss. A weight gain of 5 pounds (2.3 kg) in 1 day indicates fluid-retention problems. A weight loss is considered significant if the patient has lost more than 5% of body weight in a month or 10% in 6 months.

TABLE 30-7

Nursing History for Weight Assessment

When a patient is hospitalized, daily weight is measured at the same time of day, on the same scale, with approximately the same clothes. This allows an objective comparison of subsequent weights. Accuracy of weight measurement is important because health care providers base medical and nursing decisions (e.g., drug dosage, medications) on changes.

Several different scales are available for use. Patients capable of bearing their own weight use a standing scale. The standard platform scale is calibrated by moving the large and small weights to zero. By adjusting the calibrating knob, the balance beam is leveled and steadied. The patient stands on the scale platform and remains still as the nurse adjusts the largest solid weight to the 50-pound or 22.5-kg increment under the patient’s weight. Next the smaller weight is moved to balance the scale at the nearest  pound or 0.1 kg (Seidel et al., 2011). Electronic scales automatically display the weight within seconds. They are calibrated automatically each time they are used.

pound or 0.1 kg (Seidel et al., 2011). Electronic scales automatically display the weight within seconds. They are calibrated automatically each time they are used.

Bed and chair scales are available for patients who are unable to bear weight. Newer electronic hospital beds have built-in electronic scales for weighing patients who are not able to get out of bed.

You can use a basket or platform scale to weigh infants. After removing the infant’s clothing, weigh him or her in dry disposable diapers. Adjust the measurement later for the weight of the diaper, ensuring an accurate reading. Keep the room warm to prevent chills. Place a light cloth or paper on the surface of the infant scale to prevent cross-infection from urine or feces. When placing an infant in a basket or on a platform, hold a hand lightly above him or her to detect movements and prevent accidental falls. Measure an infant’s weight in both ounces and grams.

Measure height in patients capable of standing by having them remove their shoes. The standing surface should be clean. Use a measuring rod attached vertically to a weight scale, or use a tape ruler on the wall. As the patient stands erect, place a flat surface on his or her head that is even with the vertical measure. Then read the number on the scale or ruler that indicates his or her height in centimeters or inches.

Remove the shoes of a nonweight-bearing patient and position the patient (such as an infant) supine on a firm surface. When measuring an infant, hold his or her head and make sure that his or her legs are straight at the knees. After positioning the infant, use a tape measure to measure length from the head to the bottom of the feet (Fig. 30-3). Record the infant’s length to the nearest 0.5 cm or  inch.

inch.

Skin, Hair, and Nails

The integumentary system refers to the skin, hair, scalp, and nails. To assess the integument, you first gather a health history to guide your examination and use the techniques of inspection and palpation.

Skin

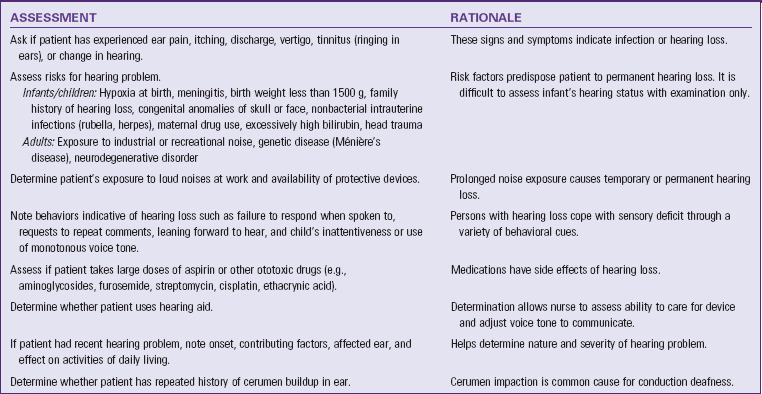

Begin an assessment of the skin by focusing on the health history questions found in Table 30-8. The physical examination begins with an inspection of all visible skin surfaces; the less visible surfaces are assessed when you examine other body systems. Use the senses of sight, smell, and touch while performing inspection and palpation of the skin.

TABLE 30-8

Nursing History for Skin Assessment

| ASSESSMENT | RATIONALE |

| Ask patient about history of changes in skin: dryness, pruritus, sores, rashes, lumps, color, texture, odor, and lesion that does not heal. | Patient is best source to recognize change. Usually skin cancer is first noticed as a localized change in skin color. |

| Consider if patient has the following history: fair, freckled, ruddy complexion; light-colored hair or eyes; tendency to burn easily. | Characteristics are risk factors for skin cancer. |

| Determine whether patient works or spends excessive time outside. If so, ask whether patient wears sunscreen and the level of protection. | Exposed areas such as face and arms are more pigmented than rest of body. The American Cancer Society (2011) recommends use of sunscreen. |

| Determine whether patient has noted lesions, rashes, or bruises. | Most skin changes do not develop suddenly. Change in character of lesion possibly indicates cancer. Bruising indicates trauma or bleeding disorder. |

| Question patient about frequency of bathing and type of soap used. | Excessive bathing and use of harsh soaps cause dry skin. |

| Ask if patient has had recent trauma to skin. | Some injuries cause bruising and changes in skin texture. |

| Determine whether patient has history of allergies. | Skin rashes commonly occur from allergies. |

| Ask if patient uses topical medications or home remedies on skin. | Incorrect use of topical agents causes inflammation or irritation. |

| Ask if patient goes to tanning parlors, uses sunlamps, or takes tanning pills. | Overexposure of skin to these irritants can cause skin cancer. |

| Ask if patient has family history of serious skin disorders such as skin cancer or psoriasis. | Family history can reveal information about patient’s condition. |

| Determine if patient works with creosote, coal, tar, petroleum products, arsenic compounds, or radium. | Exposure to these agents creates risk for skin cancer. |

Assessment of the skin reveals the patient’s health status related to oxygenation, circulation, nutrition, local tissue damage, and hydration. Check the condition of the patient’s integument to determine the need for nursing care. For example, assessment findings can help determine the type of hygiene measures required to maintain integrity of the integument (see Chapter 39). Adequate nutrition and hydration become goals of therapy if there is an alteration in the integumentary status (see Chapter 44).

Every patient has a risk for skin impairment during administration of care in a hospital setting. Risk increases if there is pressure against the skin when the patient is immobile, from reactions to various medications used in treatment, and from moisture if the patient is incontinent. At high risk are patients who are neurologically impaired or chronically ill or have had orthopedic or vascular injuries. Also at higher risk are patients with diminished mental status, poor tissue oxygenation, low cardiac output, or inadequate nutrition. Patients who are homebound, in nursing homes, or extended care facilities are often at risk for similar problems, depending on their level of mobility and the presence of chronic illness. Routinely assess the skin of all at-risk patients to look for primary or initial lesions that develop. Without proper care primary lesions can deteriorate to become secondary lesions that require more extensive nursing care. For example, the development of a pressure ulcer lengthens a hospital stay unless it is prevented or discovered and treated early (see Chapter 48).

Adequate lighting is required when assessing the skin. Daylight is the best choice to identify variations in skin color, especially for detecting skin changes in dark-skinned patients. When sunlight is not available, fluorescent lighting is the next best choice. Room temperature also affects skin assessment. A room that is too warm causes superficial vasodilation, resulting in increased redness of the skin. A cool environment causes the sensitive patient to develop cyanosis around the lips and nail beds (Seidel et al., 2011).

Although you inspect the skin over each part of the body during an examination, it is helpful to make a brief but careful overall visual sweep of the entire body. This approach provides a good idea of the distribution and extent of any lesions and the overall symmetry of skin color. Inspect all skin surfaces, making a point to do so when examining other body systems. Often overlooked, inspection of the feet is absolutely essential for patients with poor circulation or diabetes. If any abnormalities are found during an examination, palpate the involved areas. Use disposable gloves for palpation if open, moist, or draining lesions are present.

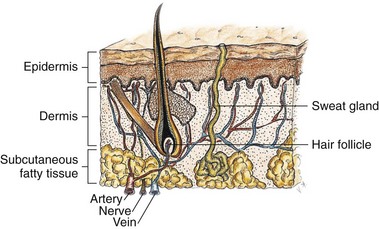

Throughout the examination remain alert for skin odors. White and black adolescents and adults ordinarily have body odor because they have a greater number of functioning apocrine glands. In contrast, Asians and Native Americans/American Indians often do not (Seidel et al., 2011). Fig. 30-4 illustrates a normal cross-section of the skin.

FIG. 30-4 A cross-section of the skin reveals three layers: epidermis, dermis, and subcutaneous fatty tissues.

Color

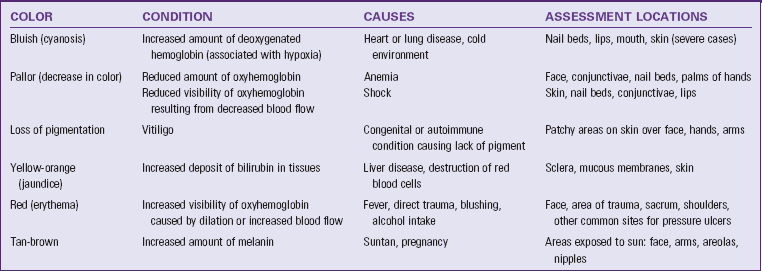

Skin color varies from body part to body part and from person to person. Despite individual variations, it is usually uniform over the body. Table 30-9 lists common variations. Normal skin pigmentation ranges in tone from ivory or light pink to ruddy pink in light skin and from light to deep brown or olive in dark skin. In older adults pigmentation increases unevenly, causing discolored skin. While inspecting the skin be aware that cosmetics or tanning agents sometimes mask normal skin color.

The assessment of color first involves areas of the skin not exposed to the sun such as the palms of the hands. Note if the skin is unusually pale or dark. Areas exposed to the sun such as the face and arms are darker. It is more difficult to note changes such as pallor or cyanosis in patients with dark skin. Usually color hues are most evident in the palms, soles of the feet, lips, tongue, and nail beds. Areas of increased color (hyperpigmentation) and decreased color (hypopigmentation) are common. Skin creases and folds are darker than the rest of the body in the dark-skinned patient.

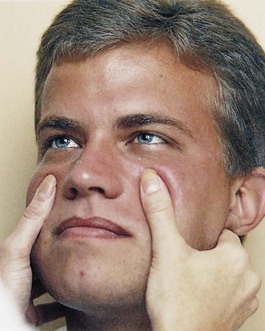

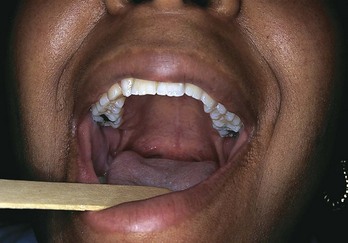

Inspect sites where abnormalities are more easily identified. For example, pallor is more evident in the face, buccal (mouth) mucosa, conjunctiva, and nail beds. Observe for cyanosis (bluish discoloration) in the lips, nail beds, palpebral conjunctivae, and palms. In recognizing pallor in the dark-skinned patient, observe that normal brown skin appears to be yellow-brown and normal black skin appears to be ashen gray. Also assess the lips, nail beds, and mucous membranes for generalized pallor; if pallor is present, the mucous membranes are ashen gray. Assessment of cyanosis in the dark-skinned patient requires observing areas where pigmentation occurs the least (conjunctiva, sclera, buccal mucosa, tongue, lips, nail beds, and palms and soles). In addition, verify these findings with clinical manifestations (Seidel et al., 2011).

The best site to inspect for jaundice (yellow-orange discoloration) is on the patient’s sclera. You can see normal reactive hyperemia, or redness, most often in regions exposed to pressure such as the sacrum, heels, and greater trochanter. Inspect for any patches or areas of skin color variation. Localized skin changes such as pallor or erythema (red discoloration) indicate circulatory changes. For example, an area of erythema is caused by localized vasodilation resulting from a sunburn, inflammation, or fever. It is difficult to observe erythema in the dark-skinned patient; thus palpate the area for heat and warmth to note the presence of skin inflammation. Compare the area with a different part of the skin to detect a difference in temperature. An area of an extremity that appears unusually pale results from arterial occlusion or edema. Be sure to ask if the patient has noticed any changes in skin coloring.

There is also a pattern of findings associated with patients who are chemically dependent or intravenous (IV) drug abusers (Table 30-10). It is sometimes difficult to recognize signs and symptoms through an isolated examination. A patient who takes repeated IV injections has edematous, reddened, and warm areas along the arms and legs. This pattern suggests recent injections. Evidence of old injection sites appears as hyperpigmented and shiny or scarred areas.

TABLE 30-10

Physical Findings of the Skin Indicative of Substance Abuse

Data from Brewer JD et al: Cocaine abuse: dermatologic manifestations and therapeutic approaches, J Am Acad Dermatol 59:483, 2008; McKenry L et al: Mosby’s pharmacology in nursing, ed 22, St Louis, 2006, Mosby; and Smith DE, Seymour RB: Clinician’s guide to substance abuse, New York, 2001, McGraw-Hill.

Moisture

The hydration of skin and mucous membranes helps to reveal body fluid imbalances, changes in the environment of the skin, and regulation of body temperature. Moisture refers to wetness and oiliness. The skin is normally smooth and dry. Skinfolds such as the axillae are normally moist. Minimal perspiration or oiliness is often present (Seidel et al., 2011). Increased perspiration can be associated with activity, exposure to warm environments, obesity, anxiety, or excitement. Use ungloved fingertips to palpate skin surfaces. Observe for dullness, dryness, crusting, and flaking that resembles dandruff when the skin surface is lightly rubbed. Excessively dry skin is common in older adults and persons who use excessive amounts of soap during bathing (Meiner, 2011). Other factors causing dry skin include lack of humidity, exposure to sun, smoking, stress, excessive perspiration, and dehydration. Excessive dryness worsens existing skin conditions such as eczema and dermatitis.

Temperature

The temperature of the skin depends on the amount of blood circulating through the dermis. Increased or decreased skin temperature indicates an increase or decrease in blood flow. An increase in skin temperature often accompanies localized erythema or redness of the skin. A reduction in skin temperature often accompanies pallor and reflects a decrease in blood flow. It is important to remember that a cold exam room can cause changes in the patient’s skin temperature and color.

Accurately assess temperature by palpating the skin with the dorsum or back of the hand. Compare symmetrical body parts. Normally the skin temperature is warm. Sometimes it is the same throughout the body, and other times it varies in one area. Always assess skin temperature for patients at risk of having impaired circulation such as after a cast application or vascular surgery. You can identify a stage I pressure ulcer early by noting warmth over an area of erythema on the skin (see Chapter 48).

Texture

Texture refers to the character of the surface of the skin and how the deeper layers feel. By palpating lightly with the fingertips, you determine whether the patient’s skin is smooth or rough, thin or thick, tight or supple, and indurated (hardened) or soft. The texture of the skin is normally smooth, soft, even, and flexible in children and adults. However, the texture is usually not uniform throughout, with thicker texture over the palms of the hand and soles of the feet. In older adults the skin becomes wrinkled and leathery because of a decrease in collagen, subcutaneous fat, and sweat glands.

Localized skin changes result from trauma, surgical wounds, or lesions. When there are irregularities in texture such as scars or indurations, ask the patient about recent injury to the skin. Deeper palpation sometimes reveals irregularities such as tenderness or localized areas of induration, which can be caused by repeated injections.

Turgor

Turgor refers to the elasticity of the skin. Normally the skin loses its elasticity with age, but fluid balance can also affect skin turgor. Edema or dehydration diminishes turgor. To assess skin turgor, grasp a fold of skin on the back of the forearm or sternal area with the fingertips and release (Fig. 30-5). Since the skin on the back of the hand is normally loose and thin, turgor is not reliably assessed at that site (Seidel et al., 2011). Normally the skin lifts easily and falls immediately back to its resting position. When turgor is poor, it stays pinched and shows tenting. Evaluate the ease with which the skin moves and the speed at which it returns to its resting state. Failure of the skin to reassume its normal contour or shape indicates dehydration. The patient with poor skin turgor does not have resilience to the normal wear and tear on the skin, and a decrease in turgor predisposes the patient to skin breakdown.

Vascularity

The circulation of the skin affects color in localized areas and leads to the appearance of superficial blood vessels. Vascularity occurs in localized pressure areas when patients remain in one position. Vascularity appears reddened, pink or pale (see Chapter 48). With aging, capillaries become fragile and more easily injured. Petechiae are nonblanching, pinpoint-size, red or purple spots on the skin caused by small hemorrhages in the skin layers. Many petechiae have no known cause, but some may indicate serious blood-clotting disorders, drug reactions, or liver disease.

Edema

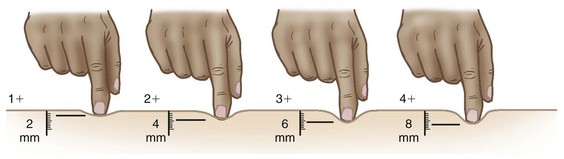

Areas of the skin become swollen or edematous from a buildup of fluid in the tissues. Direct trauma and impairment of venous return are two common causes of edema. Inspect edematous areas for location, color, and shape. The formation of edema separates the surface of the skin from the pigmented and vascular layers, masking skin color. Edematous skin also appears stretched and shiny. Palpate edematous areas to determine mobility, consistency, and tenderness. When pressure from the examiner’s fingers leaves an indentation in the edematous area, it is called pitting edema. To assess the degree of pitting edema, press the edematous area firmly with the thumb for several seconds and release. The depth of pitting, recorded in millimeters, determines the degree of edema (Seidel et al., 2011). For example, 1+ edema equals a 2-mm depth, 2+ edema equals a 4-mm depth, 3+ equals 6 mm, and 4+ equals 8 mm (Fig. 30-6).

Lesions

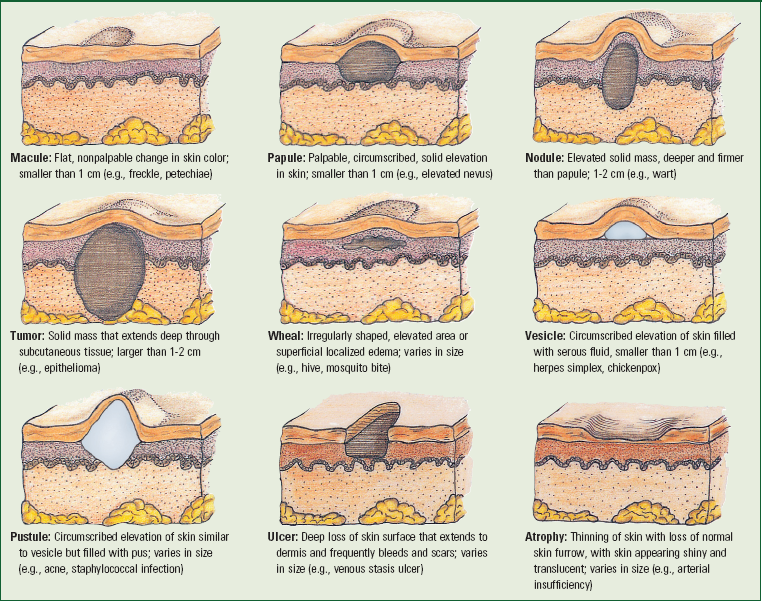

The term lesion refers broadly to any unusual finding of the skin surface. Normally the skin is free of lesions, except for common freckles or age-related changes such as skin tags, senile keratosis (thickening of skin), cherry angiomas (ruby red papules), and atrophic warts. Lesions that are primary occur as an initial spontaneous sign of a pathological process such as with an insect bite. Secondary lesions result from later formation or trauma to a primary lesion such as occurs with a pressure ulcer. When you find a lesion, collect standard information about its color, location, texture, size, shape, type, grouping (clustered or linear), and distribution (localized or generalized). Next observe for any exudate, odor, amount, and consistency. Measure the size of the lesion in centimeters by using a small, clear, flexible ruler. Measure each lesion for height, width, and depth.

Palpation helps determine the mobility, contour (flat, raised, or depressed), and consistency (soft or indurated) of a lesion. Certain types of lesions present characteristic patterns. For example, a tumor is usually an elevated, solid lesion larger than 2 cm. Primary lesions such as macules and nodules come from some stimulus to the skin (Box 30-6). Secondary lesions such as ulcers occur as alterations in primary lesions. After you identify a lesion, closely inspect it in good lighting. Palpate gently, covering the entire area of the lesion. If it is moist or draining fluid, wear gloves during palpation and pay attention to whether or not the patient identifies any areas of tenderness.

Skin (cutaneous) malignancies are the most common neoplasms in patients. For this reason the examiner should incorporate a thorough skin assessment on all patients. Cancerous lesions have distinct features and over time undergo changes in color and size (Box 30-7). Basal cell carcinoma is most common in sun-exposed areas and frequently occurs with a history of sun-damaged skin; it almost never spreads to other parts of the body. Squamous cell carcinoma is more serious than basal cell and develops on the outer layers of sun-exposed skin; these cells may travel to lymph nodes and throughout the body. Malignant melanoma, a skin cancer that develops from melanocytes, begins as a mole or other area that has changed in appearance and is usually located on normal skin; in African Americans (more than in other races), it can also appear under fingernails or on the palms of the hands and soles of the feet. Use the ABCD mnemonic to assess the skin for any type of carcinoma (ACS, 2011):

• Asymmetry—look for an uneven shape

• Border irregularity—look for edges that are blurred, notched, or ragged

• Color—look for pigmentation that is not uniform; variegated areas of blue, black, and brown and areas of pink, white, gray, blue, or red are abnormal

• Diameter—look for areas greater than the size of a typical pencil eraser

Report abnormal lesions to the health care provider for further examination. Since ultraviolet light of the sun or tanning beds increase the risk for development of skin cancers, teach patients about the risks that exist. They should be taught how to perform a skin self-examination, using the best-quality teaching materials (Box 30-8).

Hair and Scalp

Two types of hair cover the body: soft, fine, vellus hair, which covers the body; and coarse, long, thick terminal hair, which is easily visible on the scalp, axillae, and pubic areas and in the beard on men. First, obtain health history information listed in Table 30-11. Prepare to inspect the condition and distribution of hair and the integrity of the scalp by first obtaining a good light source. In addition, hair assessment occurs during all portions of the examination.

TABLE 30-11

Nursing History for Hair and Scalp Assessment

| ASSESSMENT | RATIONALE |

| Ask patient if he or she is wearing a wig or hairpiece and ask him or her to remove it. | Wigs or hairpieces interfere with inspection of hair and scalp. (Patient sometimes requests to omit this part of examination.) |

| Determine if patient has noted change in growth or loss of hair; change in texture or color. | Change often occurs slowly over time. |

| Identify type of hair care products used for grooming. | Excessive use of chemical agents and burning of hair causes drying and brittleness. |

| Determine if patient has recently had chemotherapy (drugs that cause hair loss) or taken a vasodilator (minoxidil) for hair growth. | Chemotherapeutic agents kill cells that rapidly multiply such as tumor and normal hair cells. Minoxidil causes excessive hair growth. |

| Has patient noted changes in diet or appetite? | Nutrition influences condition of hair. |

Inspection

During inspection explain that it is necessary to separate parts of the hair to detect abnormalities. Wear a pair of clean gloves if open lesions or lice are noted.

First inspect the color, distribution, quantity, thickness, texture, and lubrication of body hair. Scalp hair is coarse or fine and curly or straight; and it should be shiny, smooth, and pliant. While separating sections of scalp hair, observe characteristics of color and coarseness. Color varies from very light blond to black to gray and is sometimes altered by rinses or dyes. In older adults the hair becomes dull gray, white, or yellow.

Be aware of the normal distribution of hair growth in a man and a woman. At puberty an increase in the amount and distribution of hair occurs for both genders. During the aging process the hair may thin over the scalp, axillae, and pubic areas. For older men, facial hair decreases. A woman with hirsutism has hair growth on the upper lip, chin, and cheeks, with vellus hair becoming coarser over the body. This may be related to an endocrine disorder. For some a change in hair growth negatively affects body image and emotional well-being. The amount of hair covering the extremities is sometimes reduced as a result of aging, or it could result from arterial insufficiency that could reduce hair growth over the lower extremities. In the United States and some other cultures, women commonly shave their legs and axilla, although shaving remains a matter of personal preference among women from all cultures.

Assess for causes of changes in the thickness, texture, and lubrication of scalp hair. At times these are a result of febrile illnesses or scalp diseases that result in hair loss. Conditions such as thyroid disease alter the condition of the hair, making it fine and brittle. Hair loss (alopecia) or thinning of the hair is usually related to genetic tendencies or endocrine disorders such as diabetes, thyroiditis, and even menopause. Poor nutrition causes stringy, dull, dry, and thin hair. The oil of sebaceous glands lubricates the hair, but excessively oily hair is associated with androgen hormone stimulation. Dry, brittle hair occurs with aging and excessive use of chemical agents.

Normally the scalp is smooth and inelastic, with even coloration. Carefully separate strands of hair and thoroughly inspect the scalp for lesions, which are not easy to notice in thick hair. Note the characteristics of any scalp lesion. For lumps or bruises, ask if the patient has experienced recent head trauma. Moles on the scalp are common, but they can bleed as a result of vigorous combing or brushing. Dandruff or psoriasis frequently causes scaliness or dryness of the scalp.

Careful inspection of hair follicles on the scalp and pubic areas can reveal lice or other parasites. The three types of lice are Pediculus humanus capitis (head lice), Pediculus humanus corporis (body lice), and Pediculus pubis (crab lice). The presence of lice does not mean a person practices poor hygiene. Lice spread easily, especially among children who play closely together. Head and crab lice attach their eggs to hair. The tiny eggs look like oval particles of dandruff, although the lice themselves are difficult to see (Fig. 30-7). Head and body lice are very small with grayish-white bodies, whereas crab lice have red legs. To better identify infestations, observe for small, red, pustular eruptions in the hair follicles and areas where skin surfaces meet, such as behind the ears and in the groin. A person often has intense itching of the scalp, especially on the back of the head or neck. Combing with a fine-tooth comb reveals the small oval-shaped lice; discovery of lice requires immediate treatment. Teach the patient to perform best hair and scalp hygiene practices (Box 30-9).

Nails

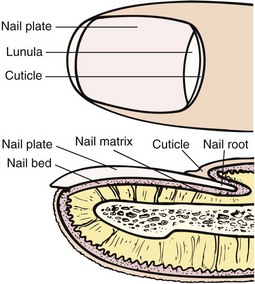

The condition of the nails reflects general health, state of nutrition, a person’s occupation, and habits of self-care. Before assessing the nails, gather a brief history (Table 30-12). The most visible portion of the nail is the nail plate, the transparent layer of epithelial cells covering the nail bed (Fig. 30-8). The vascularity of the nail bed creates the underlying color of the nail. The semilunar whitish area at the base of the nail bed is called the lunula, from which the nail plate grows.

TABLE 30-12

Nursing History for Nail Assessment

FIG. 30-8 Components of nail unit. (From Lewis SL et al: Medical-surgical nursing, ed 8, St Louis, 2011, Mosby.)

Inspection and Palpation

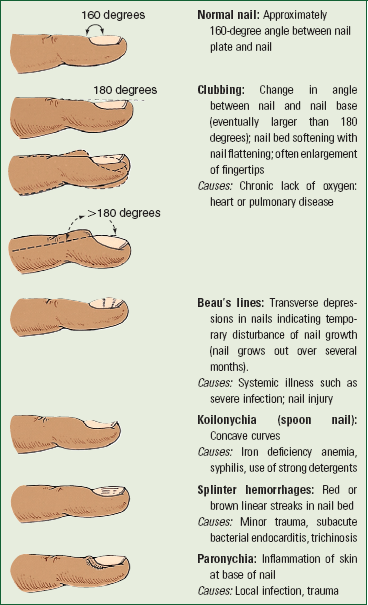

Inspect the nail bed for color, length, symmetry, cleanliness, and configuration. The shape and condition of the nails can give clues to pathophysiological problems. Assess the thickness and shape of the nail, the texture of the nail, the angle between the nail and the nail bed, and the condition of the lateral and proximal nail folds around the nail. When inspecting the nails, you gather a sense about the patient’s hygiene practices. The nails are normally transparent, smooth, well rounded, and convex, with a nail bed angle of about 160 degrees (Box 30-10). A larger angle and softening of the nail bed indicate chronic oxygenation problems. The surrounding cuticles are smooth, intact, and without inflammation. When you assess for basic care of the nails, you recognize that nail biting, stains, and jagged edges either represent poor nail care or are caused by habits or occupational exposure to grease or dirt. Jagged, bitten, or broken nail edges or cuticles predispose a patient to localized infection.

When palpating, expect to find a firm nail base and check for any abnormalities such as erythema or swelling. For patients with impaired circulation, especially observe for early signs of infection or open lesions. To palpate, gently grasp the patient’s finger and observe the color of the nail bed. The nail bed and nails appear pink with white nail tips in white patients. In darker-skinned patients the nail beds are darkly pigmented with a blue or reddish hue. A brown or black pigmentation is normal with longitudinal streaks (Fig. 30-9). Trauma, cirrhosis, diabetes mellitus, and hypertension cause splinter hemorrhages. Vitamin, protein, and electrolyte changes cause various lines or bands to form on the nail beds.

FIG. 30-9 Pigmented bands in nail of patient with dark skin. (From Habif TP: Clinical dermatology: a color guide to diagnosis and therapy, ed 5, St Louis, 2010, Mosby.)

Nails normally grow at a constant rate, but direct injury or generalized disease changes growth patterns. With aging the nails of the fingers and toes become harder and thicker. Longitudinal striations develop, and the rate of nail growth slows. Nails become more brittle, dull, and opaque and turn yellow in older adults with insufficient calcium. In addition, the cuticle becomes less thick and wide.

Calluses and corns are commonly found on the toes or fingers. A callus is flat and painless, resulting from a thickening of the epidermis. Friction and pressure from shoes cause corns, usually over bony prominences. During the examination instruct the patient in proper nail care (Box 30-11).

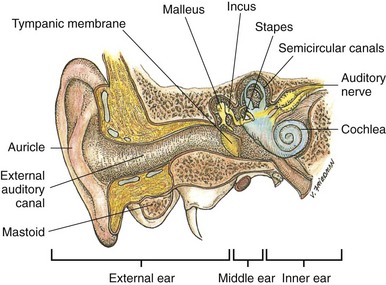

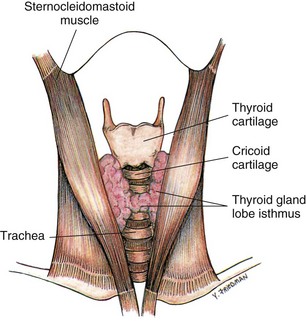

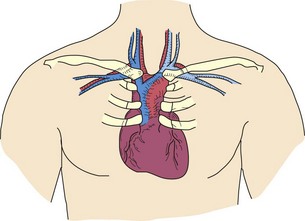

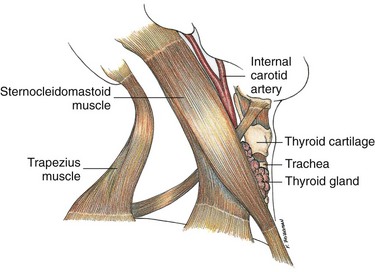

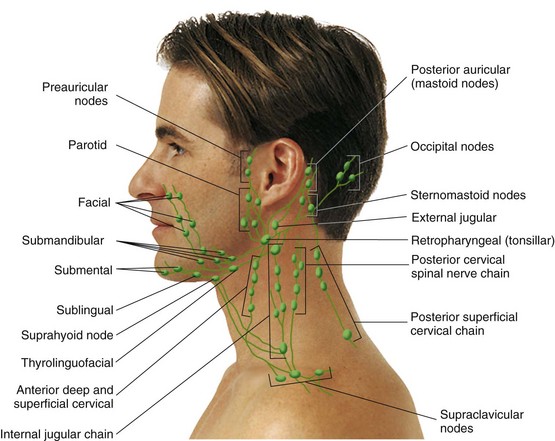

Head and Neck

An examination of the head and neck includes assessment of the head, eyes, ears, nose, mouth, pharynx, and neck (lymph nodes, carotid arteries, thyroid gland, and trachea). During assessment of peripheral arteries also assess the carotid arteries. Assessment of the head and neck uses inspection, palpation, and auscultation, with inspection and palpation often used simultaneously.

Head

The nursing history screens for intracranial injury and local or congenital deformities (Table 30-13). Inspect the patient’s head, noting the position, size, shape, and contour. The head is normally held upright and midline to the trunk. Holding it tilted to one side acts as a behavioral indicator of a potential unilateral hearing or visual loss or is a physical indicator of muscle weakness in the neck. A horizontal jerking or bobbing indicates a tremor.

TABLE 30-13

Nursing History for Head Assessment

Note the patient’s facial features, looking at the eyelids, eyebrows, nasolabial folds, and mouth for shape and symmetry. It is normal for slight asymmetry to exist. If there is facial asymmetry, note if all features on one side of the face are affected or if only a portion of the face is involved. Various neurological disorders (e.g., facial nerve paralysis) affect different nerves that innervate muscles of the face.

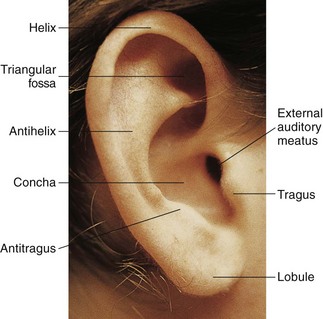

Examine the size, shape, and contour of the skull. The skull is generally round with prominences in the frontal area anteriorly and the occipital area posteriorly. Trauma typically causes local skull deformities. In infants a large head results from congenital anomaly or the buildup of cerebrospinal fluid in the ventricles (hydrocephalus). Some adults have enlarged jaws and facial bones resulting from acromegaly, a disorder caused by excessive secretion of growth hormone. Palpate the skull for nodules or masses. Gently rotate the fingertips down the midline of the scalp and along the sides of the head to identify abnormalities. Palpate the temporomandibular joint (TMJ) space bilaterally. Place the fingertips just anterior to the tragus of each ear. The fingertips should slip into the joint space as the patient’s mouth opens to gently palpate the joint spaces. Normally the movements should be smooth, although it is not unusual to hear or feel a clicking or snapping in the TMJ (Seidel et al., 2011).

Eyes

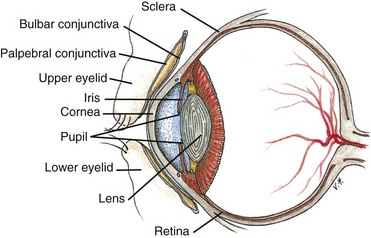

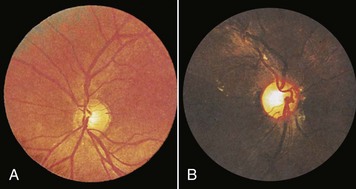

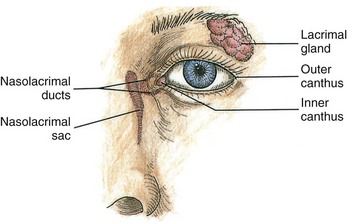

Examination of the eyes includes assessment of visual acuity, visual fields, extraocular movements, and external and internal eye structures. Fig. 30-10 shows a cross-section of the eye. The eye assessment detects visual alterations and determines the general level of assistance that patients require when ambulating or performing self-care activities. Some patients with visual problems also need special aids for reading educational materials or instructions (e.g., medication labels). Table 30-14 reviews the nursing history for an eye examination. Box 30-12 describes common types of visual problems.

TABLE 30-14

Nursing History for Eye Assessment

| ASSESSMENT | RATIONALE |

| Determine if patient has history of eye disease, (e.g., glaucoma, retinopathy, cataracts), eye trauma, diabetes, hypertension, or eye surgery. | Some diseases or trauma cause risk for partial or complete visual loss. Patient may have had surgery for a visual disorder. |

| Determine problems that prompted patient to seek health care. Ask patient about eye pain, photophobia (sensitivity to light), burning or itching, excess tearing or crusting, diplopia (double vision) or blurred vision, awareness of a “film” or “curtain” over field of vision, floaters (small, black spots that seem to float across field of vision), flashing lights, or halos around lights. | Common symptoms of eye disease indicate need for health care provider. |

| Determine whether there is family history of eye disorders or diseases. | Certain eye problems such as glaucoma or retinitis pigmentosa are inherited. |

| Review patient’s occupational history and recreational hobbies. Are safety glasses worn? | Performance of close, intricate work causes eye fatigue. Working with computers causes eye strain. Certain occupational tasks (e.g., working with chemicals) and recreational activities (e.g., fencing, motorcycle riding) place people at risk for eye injury unless they take precautions. |

| Ask patient if he or she wears glasses or contacts and, if so, how often. | Patients need to wear glasses or contacts during certain portions of examination for accurate assessment. |

| Determine when patient last visited ophthalmologist or optometrist. | Date of last eye examination reveals level of preventive care patient takes. |

| Assess medications patient is taking, including eye drops or ointment. | Determines need to assess patient’s knowledge of medications. Certain medications cause visual symptoms. |

Visual Acuity

The assessment of visual acuity (i.e., the ability to see small details) tests central vision. The easiest way to assess near vision is to ask patients to read printed material under adequate lighting. If patients wear glasses, make sure that they wear them during the assessment. Determine the language the patient speaks and his or her reading ability. Asking patients to read aloud helps to determine literacy. If the patient has difficulty reading, move to the next step.

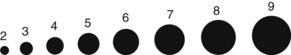

Assessment of distant vision requires using a Snellen chart (paper chart or projection screen). The chart should be well lighted. Test vision without corrective lenses first. Have the patient sit or stand 6.1 m (20 feet) away from the chart and try to read all of the letters beginning at any line with both eyes open. Then have the patient read the line with each eye separately (patient covers the opposite eye with an index card or eye cover to avoid applying pressure to the eye). Note the smallest line for which the patient is able to read all of the letters correctly and record the visual acuity for that line. Repeat the test with the patient wearing corrective lenses. Complete the test rapidly enough so the patient does not memorize the chart (Seidel et al., 2011). If a patient is unable to read, use an E chart or one with pictures of familiar objects. Instead of reading letters, patients tell which direction each E is pointing or the name of the object.

The Snellen chart has standardized numbers at the end of each line of the chart. The numerator is the number 20, or the distance the patient stands from the chart. The denominator is the distance from which the normal eye is able to read the chart. Normal visual acuity is 20/20. The larger the denominator, the poorer the patient’s visual acuity. For example, a value of 20/40 means that the patient, standing 20 feet away, can read a line that a person with normal vision can read from 40 feet away. Record visual acuity for each eye and both eyes, and record whether the test was performed with or without correction (including glasses or contact lenses).

If patients cannot read even the largest letters or figures of a Snellen chart, test their ability to count upraised fingers or distinguish light. Hold a hand 30 cm (1 foot) from the patient’s face and have him or her count the upraised fingers. To check light perception shine a penlight into the eye and turn off the light. If the patient notes when the light is turned on or off, light perception is intact.

Assess near vision by asking the patient to read a handheld card containing a vision screening chart. The patient holds the card a comfortable distance (5 to 6 cm [about  to 14 inches]) from the eyes and reads the smallest line possible. This portion of the examination is a good time to discuss the need for routine eye examinations (Box 30-13).

to 14 inches]) from the eyes and reads the smallest line possible. This portion of the examination is a good time to discuss the need for routine eye examinations (Box 30-13).

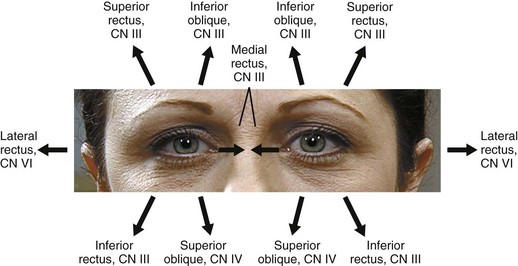

Extraocular Movements

Six small muscles guide the movement of each eye. Both eyes move parallel to one another in each of the six directions of gaze (Fig. 30-11). To assess extraocular movements the patient sits or stands, and the nurse faces the patient from 60 cm (2 feet) away. The nurse holds a finger at a comfortable distance (15 to 30 cm [6 to 12 inches]) from the patient’s eyes. While the patient maintains his or her head in a fixed position facing forward, the nurse directs him or her to follow with the eyes only as the nurse’s finger moves to the right, left, and diagonally up and down to the left and right. The nurse moves the finger smoothly and slowly within the normal field of vision.

FIG. 30-11 Six directions of gaze. Direct patient to follow finger movement through each gaze. CN, Cranial nerve. (From Seidel HM et al: Mosby’s guide to physical examination, ed 7, St Louis, 2011, Mosby.)

As the patient gazes in each direction, observe for parallel eye movement, the position of the upper eyelid in relation to the iris, and the presence of abnormal movements. As the eyes move through each direction of gaze, the upper eyelid covers the iris only slightly. Nystagmus, an involuntary, rhythmical oscillation of the eyes, occurs as a result of local injury to eye muscles and supporting structures or a disorder of the cranial nerves innervating the muscles. Initiate nystagmus in patients with normal eye movements by having them gaze to the far left or right.

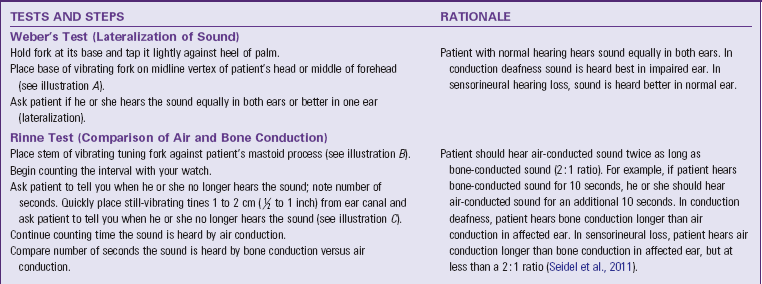

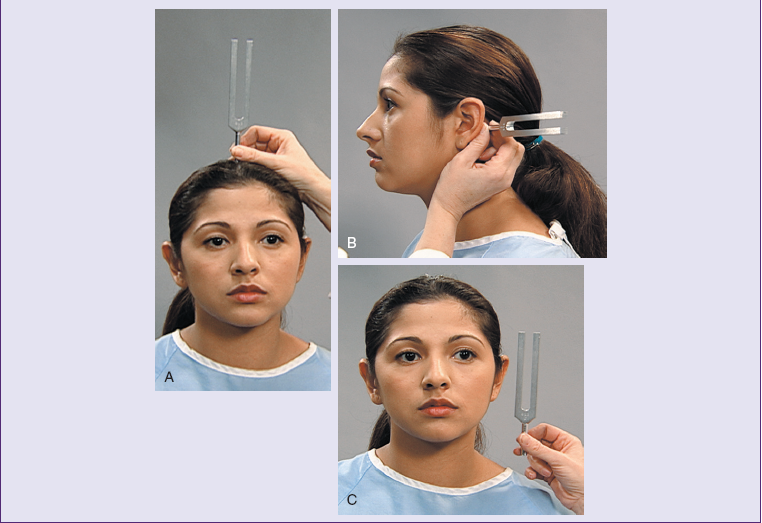

Visual Fields