Self-Concept

• Discuss factors that influence the components of self-concept.

• Identify stressors that affect self-concept and self-esteem.

• Describe the components of self-concept as related to psychosocial and cognitive developmental stages.

• Explore ways in which a nurse’s self-concept and nursing actions affect a patient’s self-concept and self-esteem.

• Discuss evidence-based practice applicable for identity confusion, disturbed body image, low self-esteem, and role conflict.

• Examine cultural considerations that affect self-concept.

• Apply the nursing process to promote a patient’s self-concept.

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Potter/fundamentals/

Self-concept is an individual’s view of self. It is a subjective view and a complex mixture of unconscious and conscious thoughts, attitudes, and perceptions. Self-concept, or how a person thinks about oneself, directly affects self-esteem, or how one feels about oneself. Although these two terms are often used interchangeably, nurses need to differentiate the two so they correctly and completely assess patients and develop an individualized plan of care based on the patient’s needs.

Nurses care for patients who face a variety of health problems that threaten their self-concept and self-esteem. The loss of bodily function, decline in activity tolerance, and difficulty in managing a chronic illness are examples of situations that change a patient’s self-concept. As a nurse, you will help patients adjust to alterations in self-concept and support components of self-concept to promote successful coping and positive health outcomes.

Scientific Knowledge Base

The development and maintenance of self-concept and self-esteem begin at a young age and continue across the life span with a general tendency for boys to report higher self-esteem than girls. However, the exact amount of this gender difference and the way it varies across the life span remain unclear. Parents and other primary caregivers influence the development of a child’s self-concept and self-esteem. In addition, individuals learn and internalize cultural influences on self-concept and self-esteem in childhood and adolescence (Guilamo-Ramos, 2009). There is a significant amount of emphasis on fostering a school-age child’s self-concept. In general, young children tend to rate themselves higher than they rate other children, suggesting that their view of themselves is positively inflated. Adolescence is a particularly critical time when many variables, including school, family, and friends, affect self-concept and self-esteem (Martyn-Nemeth et al., 2009). The adolescent experience can adversely affect self-esteem, often more strongly for girls than for boys. For example, some adolescent girls are more sensitive about their appearance and how others view them. Thus it is important to assess changes in self-esteem among early, middle, and late adolescence because changes in self-concept occur over time (Fig. 33-1).

FIG. 33-1 Adolescents’ participation in group activities can foster self-esteem. (From Hockenberry MJ, Wilson D: Wong’s essentials of pediatric nursing, ed 8, St Louis, 2009, Mosby.)

Job satisfaction and overall performance in adulthood are also linked to self-esteem. Sometimes when individuals lose a job, their sense of self diminishes, they lose motivation to be socially active, or they even become depressed. They lose their job identity, and this alters their self-perceptions. Establishing a stable sense of self that transcends relationships and situations is a developmental goal of adulthood.

Evidence suggests that sense of self is often negatively affected in older adulthood because of the intensity of emotional and physical changes associated with aging (Ebersole et al., 2008; Price, 2010). For example, when an older adult loses a partner or experiences a change in health, sometimes there is a change in social interaction or even self-care practices.

Researchers also found ethnic and cultural differences in self-concept and self-esteem across the life span that impact health behaviors. In Latino youth, ethnic pride and self-esteem serve as protective factors against risk behaviors, including intentions to smoke cigarettes and to have sexual intercourse (Guilamo-Ramos, 2009). Cultural identity of older adults is one of the major elements of self-concept and a key aspect of self-esteem (Ebersole et al., 2008). Considering aging from a cultural perspective provides the context for providing the highest-quality nursing care. Sensitivity to factors that affect self-concept and self-esteem in diverse cultures is essential to ensure an individualized approach to health care.

How individuals view themselves and their perception of their health are closely related. Lower self-esteem is a risk factor that leaves one vulnerable to health problems, whereas higher self-esteem and strong social relationships support good health (Stinson et al., 2008). A patient’s belief in personal health often enhances his or her self-concept. Statements such as “I can get through anything” or “I’ve never been sick a day in my life” indicate that a person’s thoughts about personal health are positive. Illness, hospitalization, and surgery also affect self-concept. Chronic illness often affects the ability to provide financial support and maintain relationships, which then affects an individual’s self-esteem and perceived roles within the family. Negative perceptions regarding health status are reflected in such statements as “It’s not worth it anymore” or “I’m a burden to my family.” Further, chronic illness affects identity and body image as reflected by verbalizations such as “I’ll never get any better” or “I can’t stand to look at myself anymore.”

What individuals think and how they feel about themselves affect the way in which they care for themselves physically and emotionally and how they care for others. Further, a person’s behaviors are generally consistent with both self-concept and self-esteem. Individuals who have a poor self-concept often do not feel in control of situations and worthy of care, which influences decisions regarding health care. Patients often have difficulty making even simple decisions, such as what to eat. Knowledge of variables that affect self-concept and self-esteem is critical to provide effective treatment.

Nursing Knowledge Base

In providing evidence-based practice to patients, incorporate professional nursing knowledge developed from the humanities, sciences, nursing research, and clinical practice. A broad knowledge base allows nurses to have a holistic view of patients, thus promoting quality patient care that best meets the self-concept needs of each patient and family. Understanding a patient’s self-concept is a necessary part of all nursing care (Stuart, 2009).

Development of Self-Concept

The development of self-concept is a complex lifelong process that involves many factors. Erikson’s psychosocial theory of development (1963) remains beneficial in understanding key tasks that individuals face at various stages of development. Each stage builds on the tasks of the previous stage. Successful mastery of each stage leads to a solid sense of self (Box 33-1).

Learn to recognize an individual’s failure to achieve an age-appropriate developmental stage or his or her regression to an earlier stage in a period of crisis. This understanding allows you to individualize care and determine appropriate nursing interventions. Self-concept is always changing and is based on the following:

• Perceived reactions of others to one’s body

• Ongoing perceptions and interpretations of the thoughts and feelings of others

• Personal and professional relationships

• Academic and employment-related identity

• Personality characteristics that affect self-expectations

• Perceptions of events that have an impact on the self

Self-esteem is usually highest in childhood, declines during adolescence, gradually rises throughout adulthood, and diminishes again in old age (Stuart, 2009). Although this pattern varies, in general it holds true across gender, socioeconomic status, and ethnicity. Children often report high self-esteem because their sense of self is inflated by a variety of extremely positive sources, and the subsequent decline is from time to time associated with a shift to more realistic information about the self.

Erikson’s (1963) emphasis on the generativity stage (see Chapter 11) explains the rise in self-esteem and self-concept in adulthood. The individual focuses on being increasingly productive and creative at work, while at the same time promoting and guiding the next generation. Several individuals report a decline in self-esteem in later adulthood (Ebersole et al., 2008). Based on Erikson’s stages of development, a decline in self-concept in later adulthood reflects a diminished need for self-promotion and a shift in self-concept to a more modest and balanced view of self. Identifying specific nursing interventions to address the unique needs of patients at various life stages is essential.

Components and Interrelated Terms of Self-Concept

A positive self-concept gives a sense of meaning, wholeness, and consistency to a person. A healthy self-concept has a high degree of stability, which generates positive feelings toward self. The components of self-concept are identity, body image, and role performance. Because how one thinks about oneself (self-concept) affects how one feels about oneself (self-esteem), both concepts need to be evaluated.

Identity

Identity involves the internal sense of individuality, wholeness, and consistency of a person over time and in different situations. It implies being distinct and separate from others. Being “oneself” or living an authentic life is the basis of true identity. Children learn culturally accepted values, behaviors, and roles through identification and modeling. They often gain an identity from self-observations and from what individuals tell them. An individual first identifies with parenting figures and later with other role models such as teachers or peers. To form an identity, the child must be able to bring together learned behaviors and expectations into a coherent, consistent, and unique whole (Erikson, 1963).

The achievement of identity is necessary for intimate relationships because individuals express identity in relationships with others (Stuart, 2009). Sexuality is a part of identity, and its focus differs across the life span. For example, as an adult ages, the focus shifts from procreation to companionship, physical and emotional intimacy, and pleasure-seeking (Ebersole et al., 2008). Gender identity is a person’s private view of maleness or femaleness; gender role is the masculine or feminine behavior exhibited. This image and its meaning depend on culturally determined values (see Chapters 9 and 22).

Cultural differences in identity exist (Box 33-2). Racial or cultural identity develops from identification and socialization within an established group and through the experience of integrating the response of individuals outside the cultural or racial group into one’s self-concept. Differences in ethnic identity (e.g., Mexican American or Cuban American) exist through identification with traditions, customs, and rituals within one’s race/ethnic group (e.g., Hispanic/Latino). In general, the more a person identifies with social groups, the greater his or her self-esteem. In addition, when ethnic identity is central to self-concept and is positive, ethnic pride and self-esteem tend to be high (Guilamo-Ramos, 2009). An individual who experiences discrimination, prejudice, or environmental stressors such as low-income or high-crime neighborhoods often conceptualizes himself or herself differently than an individual who experiences better living conditions.

Body Image

Body image involves attitudes related to the body, including physical appearance, structure, or function. Feelings about body image include those related to sexuality, femininity and masculinity, youthfulness, health, and strength. These mental images are not always consistent with a person’s actual physical structure or appearance. Some body image distortions have deep psychological origins, such as the eating disorder anorexia nervosa. Other alterations occur as a result of situational events, such as the loss or change in a body part. Be aware that most men and women experience some degree of dissatisfaction with their bodies, which affects body image and overall self-concept. Individuals often exaggerate disturbances in body image when a change in health status occurs. The way others view a person’s body and the feedback offered are also influential. For example, a controlling, violent husband tells his wife that she is ugly and that no one else would want her. Over the years of marriage she incorporates this devaluation into her self-concept.

Cognitive growth and physical development also affect body image. Normal developmental changes such as puberty and aging have a more apparent effect on body image than on other aspects of self-concept. Hormonal changes during adolescence and menopause influence body image. The development of secondary sex characteristics and the changes in body fat distribution have a tremendous impact on an adolescent’s self-concept. Early maturation is associated with lower psychological well-being and lower enjoyment of physical activity, which in turn could negatively impact body image (Davison et al., 2007). For both male and female adolescents, negative body image is a risk factor for suicidal thoughts (Brausch and Muehlenkamp, 2007). A threat to body image and overall self-concept can affect adherence to recommended health regimens, including diet and taking medications as prescribed (Thomas, 2007). Changes associated with aging (e.g., wrinkles; graying hair; and decrease in visual acuity, hearing, and mobility) also affect body image in an older adult.

Cultural and societal attitudes and values influence body image. Culture and society dictate the accepted norms of body image and influence one’s attitudes (Fig. 33-2). Racial and ethnic background plays an integral role in body satisfaction in adolescent girls and is reflected in differences in body satisfaction among groups. Further, body image is more favorable in cultures in which girls describe more reasonable views about physical appearance, report less social pressure for thinness, and have less tendency to base self-esteem on body image. Values such as ideal body weight and shape and attitudes toward piercing and tattoos are culturally based. American society emphasizes youth, beauty, and wholeness. Western cultures have been socialized to dread the normal aging process, whereas eastern cultures view aging very positively and respect older adults. Body image issues are often associated with impaired self-concept and self-esteem.

Role Performance

Role performance is the way in which individuals perceive their ability to carry out significant roles (e.g., parent, supervisor, or close friend). Normal changes associated with maturation result in changes in role performance. For example, when a man has a child, he becomes a father. The new role of father involves many changes in behavior if the man is going to be successful. Group interventions aimed at improving fathering experiences have led to significant improvements in the father’s participation in the family, including role performance, involvement, communication, self-esteem, a sense of increased competence, and decreased stress in parenting (Gearing et al., 2008). Roles that individuals follow in given situations involve socialization, expectations, or standards of behavior. The patterns are stable and change only minimally during adulthood.

Ideal societal role behaviors are often hard to achieve in real life. Individuals have multiple roles and personal needs that sometimes conflict. Successful adults learn to distinguish between ideal role expectations and realistic possibilities. To function effectively in multiple roles, a person must know the expected behavior and values, desire to conform to them, and be able to meet the role requirements. Fulfillment of role expectations leads to an enhanced sense of self. Difficulty or failure in meeting role expectations leads to deficits and often contributes to decreased self-esteem or altered self-concept.

Self-Esteem

Self-esteem is an individual’s overall feeling of self-worth or the emotional appraisal of self-concept. It is the most fundamental self-evaluation because it represents the overall judgment of personal worth or value. Self-esteem is positive when one feels capable, worthwhile, and competent (Rosenberg, 1965). A person’s self-esteem is related to his or her evaluation of his or her effectiveness at school, within the family, and in social settings. The evaluation of others also is likely to have a profound influence on a person’s self-esteem. For example, college athletes report greater levels of self-esteem and social connectedness and lower levels of depression than nonathletes. The positive influence of team support can protect college athletes from disturbances of self-esteem and depression symptoms (Armstrong and Oomen-Early, 2009).

Considering the relationship between a person’s actual self-concept and his or her ideal self enhances understanding of that person’s self-esteem. The ideal self consists of the aspirations, goals, values, and standards of behavior that a person considers ideal and strives to attain. In general, a person whose self-concept comes close to matching the ideal self has high self-esteem, whereas a person whose self-concept varies widely from the ideal self suffers from low self-esteem (Stuart, 2009). Once established, basic feelings about the self tend to be constant, even though a situational crisis can temporarily affect self-esteem.

Factors Influencing Self-Concept

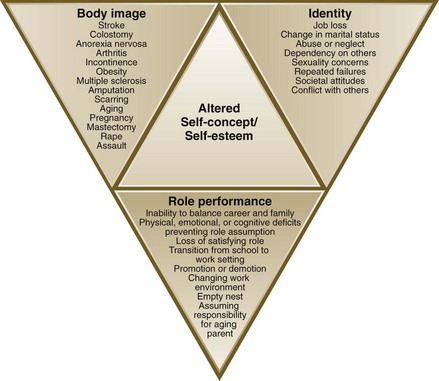

A self-concept stressor is any real or perceived change that threatens identity, body image, or role performance (Fig. 33-3). An individual’s perception of the stressor is the most important factor in determining his or her response. The ability to reestablish balance following a stressor is related to numerous factors, including the number of stressors, duration of the stressor, and health status (see Chapter 37). Stressors challenge a person’s adaptive capacities. Changes that occur in physical, spiritual, emotional, sexual, familial, and sociocultural health affect self-concept. Being able to adapt to stressors is likely to lead to a positive sense of self, whereas failure to adapt often leads to a negative self-concept.

Any change in health is a stressor that potentially affects self-concept. A physical change in the body sometimes leads to an altered body image, affecting identity and self-esteem. Chronic illnesses often alter role performance, which change an individual’s identity and self-esteem. Further, an essential process in the adjustment to loss is the development of a new self-concept. A loss of a partner can lead to a loss of identity and a lower self-esteem. Unlike the loss in self-esteem shown in vulnerable older adults, the resiliency demonstrated in some older adults may reflect more sophisticated cognitive strategies to manage losses.

The stressors created as a result of a crisis also affect a person’s health. If the resulting identity confusion, disturbed body image, low self-esteem, or role conflict is not relieved, illness can result. For example, the diagnosis of cancer places additional demands on a person’s established living pattern. It changes his or her appraisal of and satisfaction with the current level of physical, emotional, and social functioning. In this case assess self-esteem, effectiveness of coping strategies, and social support. During self-concept crises, supportive and educative resources are valuable in helping a person learn new ways of coping with and responding to the stressful event or situation to maintain or enhance self-concept.

Identity Stressors

Stressors affect an individual’s identity throughout life, but individuals are particularly vulnerable during adolescence. Adolescents are trying to adjust to the physical, emotional, and mental changes of increasing maturity, which results in insecurity and anxiety. It is also a time when the adolescent is developing psychosocial competence, including coping strategies (see Chapter 37).

An adult generally has a more stable identity and thus a more firmly developed self-concept than an adolescent. Cultural and social stressors rather than personal stressors have more impact on an adult’s identity. For example, an adult has to balance career and family or make choices regarding honoring religious traditions from one’s family of origin. Identity confusion results when people do not maintain a clear, consistent, and continuous consciousness of personal identity. It occurs at any stage of life if a person is unable to adapt to identity stressors.

Body Image Stressors

A change in the appearance, structure, or function of a body part requires an adjustment in body image. An individual’s perception of the change and the relative importance placed on body image affects the significance of a loss of function or change in appearance. For example, if a woman’s body image incorporates reproductive organs as the ideal, a hysterectomy needed because of a diagnosis of uterine cancer is a significant alteration and can result in a perceived loss of femininity or wholeness. Changes in the appearance of the body such as an amputation, facial disfigurement, or scars from burns are obvious stressors affecting body image. Mastectomy and colostomy are surgical procedures that alter the appearance and function of the body, yet the changes are not apparent to others when the individual is dressed. Although potentially undetected by others, these bodily changes significantly impact the individual. Even some elective changes such as breast augmentation or reduction affect body image. Chronic illnesses such as heart and renal disease affect body image because the body no longer functions at an optimal level. The patient has to adjust to a decrease in activity tolerance that impacts his or her ability to perform normal activities of daily living. In addition, pregnancy, significant weight gain or loss, pharmacological management of illness, or radiation therapy changes body image. Negative body image often leads to adverse health outcomes.

The response of society to physical changes in an individual often depends on the conditions surrounding the alteration. Some social changes have allowed the public to respond more favorably to illness and altered body image. For example, the media frequently presents positive stories about persons adjusting in a healthy manner following serious disabilities (e.g., Christopher Reeve’s spinal cord injury) or adapting to a debilitating illness (e.g., Michael J. Fox’s Parkinson’s disease). These stories change public awareness and the perception of what constitutes a disability and provide positive role models for individuals undergoing self-concept stressors and their families, friends, and society as a whole. In view of the growing epidemic of obesity in western cultures, parents and health care providers need to address weight management issues without causing further injury to body image. Providing a social environment that focuses on health and fitness rather than a drive for thinness for girls or muscularity for boys can potentially increase adolescent satisfaction with their bodies (Brunet et al., 2010).

Role Performance Stressors

Throughout life a person undergoes numerous role changes. Situational transitions occur when parents, spouses, children, or close friends die or people move, marry, divorce, or change jobs. It is important to recognize that a shift along the continuum from illness to wellness is as stressful as a shift from wellness to illness. Any of these transitions may lead to role conflict, role ambiguity, role strain, or role overload.

Role conflict results when a person has to simultaneously assume two or more roles that are inconsistent, contradictory, or mutually exclusive. For example, when a middle-age woman with teenage children assumes responsibility for the care of her older parents, conflicts occur in relation to being both a parent to her children and the child of her parents. Negotiating a balance of time and energy between her children and parents creates role conflicts. The perceived importance of each conflicting role influences the degree of conflict experienced. The sick role involves the expectations of others and society regarding how an individual behaves when sick. Role conflict occurs when general societal expectations (take care of yourself, and you will get better) and the expectations of co-workers (need to get the job done) collide. The conflict of taking care of oneself while getting everything done is often a major challenge.

Role ambiguity involves unclear role expectations, which makes people unsure about what to do or how to do it, creating stress and confusion. Role ambiguity is common in the adolescent years. Parents, peers, and the media pressure adolescents to assume adultlike roles, yet many lack the resources to move beyond the role of a dependent child. Role ambiguity is also common in employment situations. In complex, rapidly changing, or highly specialized organizations, employees often become unsure about job expectations.

Role strain combines role conflict and role ambiguity. Some express role strain as a feeling of frustration when a person feels inadequate or unsuited to a role such as providing care for a family member with Alzheimer’s disease.

Role overload involves having more roles or responsibilities within a role than are manageable. This is common in an individual who unsuccessfully attempts to meet the demands of work and family while carving out some personal time. Often during periods of illness or change, those involved either as the one who is ill or as a significant other find themselves in role overload.

Self-Esteem Stressors

Individuals with high self-esteem are generally more resilient and better able to cope with demands and stressors than those with low self-esteem. Low self-worth contributes to feeling unfulfilled and disconnected from others. Decreased self-worth can potentially result in depression and unremitting uneasiness or anxiety. Illness, surgery, or accidents that change life patterns also influence feelings of self-worth. Chronic illnesses such as diabetes, arthritis, and cardiac dysfunction require changes in accepted and long-assumed behavioral patterns. The more the chronic illness interferes with the ability to engage in activities contributing to feelings of worth or success, the more it affects self-esteem.

Self-esteem stressors vary with developmental stages. Perceived inability to meet parental expectations, harsh criticism, inconsistent discipline, and unresolved sibling rivalry reduce the level of self-worth of children. A developmental milestone such as pregnancy introduces unique self-concept stressors and has significant health care implications. For some economically disadvantaged youth, safe sex behaviors are not always valued, and pregnancy is an affirmation of ethnic identity. Low self-esteem during adolescence also has significant real-world consequences in adulthood, including poor health, criminal behavior, and limited economic prospects compared to adolescents with high self-esteem. Self-esteem and health behaviors are intertwined. Stressors affecting the self-esteem of an adult include failure in work and unsuccessful relationships. Self-concept stressors in older adults include health problems, declining socioeconomic status, spousal loss or bereavement, loss of social support, and decline in achievement experiences following retirement (Box 33-3).

Family Effect on Self-Concept Development

The family plays a key role in creating and maintaining the self-concepts of its members. Children develop a basic sense of who they are from their family caregivers. A child also gains accepted norms for thinking, feeling, and behaving from family members. Sometimes well-meaning parents cultivate negative self-concepts in children. Some literature suggests that parents are the most important influences on a child’s development, yet variations in parenting approach depend on the culture. Specifically a child’s positive self-esteem and school achievement are fostered by parents who respond in a firm, consistent, and warm manner. High parental support and parental monitoring are related to greater self-esteem and lower risk behaviors. For example, in Mexican American adolescents perceived parental educational involvement combined with their perceived acculturation and self-esteem significantly affect their aspirations and achievement (Carranza et al., 2009). Parents who are harsh, inconsistent, or have low self-esteem themselves often behave in ways that foster negative self-concepts in their children. Positive communication and social support foster self-esteem and well-being in adolescence. To reverse a patient’s negative self-concept, first assess the family’s style of relating (see Chapter 10). Family and cultural factors sometimes influence negative health practices such as cigarette smoking (Box 33-4). Self-concept change demands an evidence-based practice approach supported by the entire health care team.

Nurse’s Effect on Patient’s Self-Concept

A nurse’s acceptance of a patient with an altered self-concept promotes positive change. Often this simply involves sitting with a patient and forming a therapeutic relationship. When a patient’s physical appearance has changed, it is likely that both the patient and the family look to nurses and observe their verbal and nonverbal responses and reactions to the changed appearance. You need to remain aware of your own feelings, ideas, values, expectations, and judgments. Self-awareness is critical in understanding and accepting others. Nurses need to assess and clarify the following self-concept issues about themselves:

• Thoughts and feelings about lifestyle, health, and illness

• Awareness of how their own nonverbal communication affects patients and families

• Personal values and expectations and how these affect patients

• Ability to convey a nonjudgmental attitude toward patients

• Preconceived attitudes toward cultural differences in self-concept and self-esteem

Some patients with a change in body appearance or function are extremely sensitive to the verbal and nonverbal responses of the health care team. A positive, matter-of-fact approach to care provides a model for the patient and family to follow. For example, when you observe a positive change in a patient’s behavior, note it and allow the patient to establish its meaning. Nurses have a significant effect on patients by conveying genuine interest and acceptance. Including self-concept issues in the planning and delivery of care can positively influence patient outcomes. Building a trusting nurse-patient relationship that incorporates both the patient and family in the decision-making process enhances self-concept. Nurses individualize their approach by highlighting a patient’s unique needs and incorporating alternative health care practices or methods of spiritual expression into the plan of care. It is important that health care providers understand the degree to which self-esteem and sexuality affect patient outcomes (Figueroa-Hass, 2007).

Your nursing care significantly affects a patient’s body image. For example, the body image of a woman following a mastectomy is positively influenced by a nurse showing acceptance of the mastectomy scar. On the other hand, a nurse who has a shocked or disgusted facial expression contributes to the woman developing a negative body image. Patients closely watch the reactions of others to their wounds and scars, and it is very important to be aware of your responses toward the patient. Statements such as “This wound is healing nicely” or “This tissue looks healthy” are affirmations for the body image of the patient. Nonverbal behaviors convey the level of caring that exists for a patient and affect self-esteem. Anticipate personal reactions, acknowledge them, and focus on the patient instead of the unpleasant task or situation. Nurses who put themselves in the patient’s situation incorporate measures to ease embarrassment, frustration, anger, and denial.

Preventive measures, early identification, and appropriate treatment minimize the intensity of self-esteem stressors and the potential effects for a patient and his or her family. Learn to design specific self-concept interventions to fit a patient’s profile of risk factors. It is essential to assess a patient’s perception of a problem and work collaboratively to resolve self-concept issues. For example, incorporating self-esteem activities into regular school health and physical education curriculum can result in a positive change in students’ physical self-esteem and family self-esteem (Lai et al., 2009). Interventions designed to promote active living and healthy eating may be beneficial for preventing childhood obesity, improving self-esteem, preventing chronic diseases, and improving mental health in adulthood (Wang et al., 2009).

Critical Thinking

Successful critical thinking requires synthesis of knowledge, experience, information gathered from patients and families, critical thinking attitudes, and ethical and professional standards. Solid clinical judgment requires anticipating and securing the necessary information, analyzing the data, and making appropriate decisions regarding patient care.

In the case of self-concept, it is essential to integrate knowledge from nursing and other disciplines, including self-concept theory, communication principles, and a consideration of cultural and developmental factors. Previous experience in caring for patients with self-concept alterations helps to individualize care. Self-concept profoundly influences a person’s response to illness. A critical thinking approach to care is essential.

Nursing Process

Apply the nursing process and use a critical thinking approach in your care of patients. The nursing process provides a clinical decision-making approach for you to develop and implement an individualized plan of care. The nursing process is continuous until the patient’s self-concept is improved, restored, or maintained.

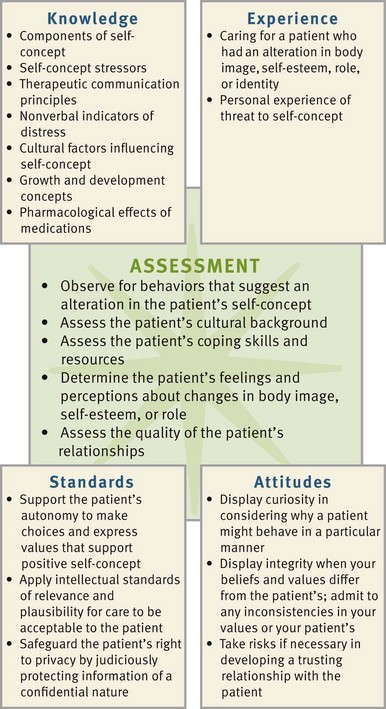

Assessment

During the assessment process, thoroughly assess each patient and critically analyze findings to ensure that you make patient-centered clinical decisions required for safe nursing care. In assessing self-concept and self-esteem, first focus on each component of self-concept (identity, body image, and role performance). Assessment needs to include looking for the range of behaviors suggestive of an altered self-concept or self-esteem (Box 33-5), actual and potential self-concept stressors (see Fig. 33-3), and coping patterns. Gathering comprehensive assessment data requires the critical synthesis of information from multiple sources (Fig. 33-4). In addition to direct questioning (Box 33-6), nurses gather much of the data regarding self-concept through observation of the patient’s nonverbal behavior and by paying attention to the content of the patient’s conversations. Take note of the manner in which patients talk about the people in their lives because this provides clues to both stressful and supportive relationships and key roles the patient assumes. Using knowledge of developmental stages to determine which areas are likely to be important to the patient, inquire about these aspects of the person’s life. For example, ask a 70-year-old patient about his life and what has been important to him. The individual’s conversation likely provides data relating to role performance, identity, self-esteem, stressors, and coping patterns.

Through the Patient’s Eyes

An important factor in assessing self-concept is the person’s viewpoint of his or her health condition and its influence on self-concept. Give patients the opportunity to tell their stories of how they perceive their illness or condition affecting their identity, their image of themselves, and their ability to lead a normal lifestyle. Also assess patients’ expectations of health care by asking them how interventions will make a difference. This is also an opportunity to discuss the patient’s goals. For example, a nurse working with a patient who is experiencing anxiety related to an upcoming diagnostic study asks the patient about his expectations of the relaxation exercise that they have been practicing together. The patient’s response gives the nurse valuable information about the patient’s beliefs and attitudes regarding the efficacy of the interventions and the potential need to modify the nursing approach.

Coping Behaviors

The nursing assessment also includes consideration of previous coping behaviors; the nature, number, and intensity of the stressors; and the patient’s internal and external resources. Knowledge of how a patient has dealt with stressors in the past provides insight into his or her style of coping. Patients do not address all issues in the same way, but they often use a familiar coping pattern for newly encountered stressors. Identify previous coping strategies to determine whether these patterns have contributed to healthy functioning or created more problems. For example, the use of drugs or alcohol during times of stress often creates additional stressors (see Chapter 37).

Significant Others

Exploring resources and strengths such as availability of significant others or prior use of community resources is important in formulating a realistic and effective plan of care. Valuable information comes from conversations with family and significant others. Significant others sometimes have insights into the person’s way of dealing with stressors. They also have knowledge about what is important to the person’s self-concept. The way in which a significant other talks about the patient and the significant other’s nonverbal behaviors provide information about what kind of support is available for the patient.

Nursing Diagnosis

Carefully consider the assessment data to identify a patient’s actual or potential problem areas. Rely on knowledge and experience, apply appropriate professional standards, and look for clusters of defining characteristics that indicate a nursing diagnosis. Although there are four nursing diagnostic labels for altered self-concept, the following list (NANDA International, 2009) also provides examples of self-concept–related nursing diagnoses:

Making nursing diagnoses about self-concept is complex. Often isolated data are defining characteristics for more than one nursing diagnosis (Box 33-7). For example, a patient expresses feelings of uncertainty and inadequacy. These are defining characteristics for both anxiety and situational low self-esteem. Realizing that the patient is demonstrating defining characteristics of more than one nursing diagnosis guides you to gather specific data to validate and differentiate the underlying problem. To further assess the possibility of anxiety as the nursing diagnosis, consider whether the person has any of the following defining characteristics: Is the person experiencing increased muscle tension, shakiness, a sense of being “rattled,” or restlessness? These symptoms suggest anxiety as the more appropriate diagnosis. On the other hand, if the person expresses a predominantly negative self-appraisal, including inability to handle situations or events and difficulty making decisions, these characteristics suggest that situational low self-esteem is more appropriate. To further aid in differentiating between the two demonstrated diagnoses, information regarding recent events in the person’s life and how the person has viewed himself or herself in the past provide insight into the most appropriate nursing diagnosis. As you gather additional data, usually the priority nursing diagnosis becomes evident.

To validate critical thinking regarding a nursing diagnosis, share observations with the patient and allow him or her to verify perceptions. This approach often results in the patient providing additional data, which further clarifies the situation. For example, “I noticed that you jumped when I touched your arm. Are you feeling uneasy today?” allows the patient to verify whether he or she is in fact anxious and describe his or her concerns.

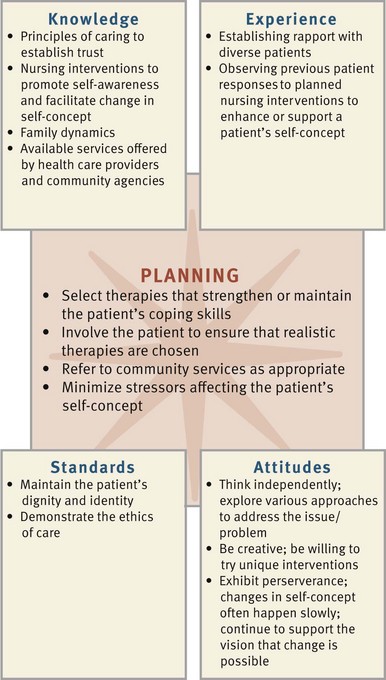

Planning

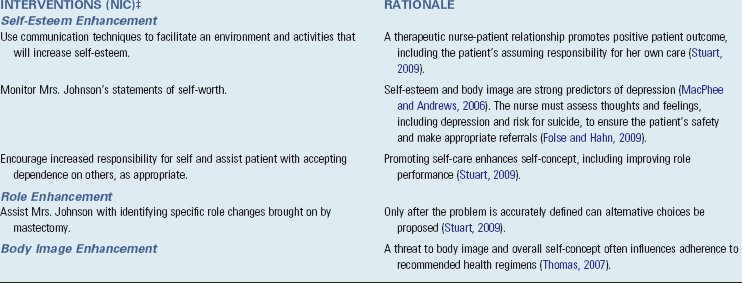

During planning synthesize knowledge, experience, critical thinking attitudes, and standards (Fig. 33-5). Critical thinking ensures that a patient’s plan of care integrates information known about the individual and key critical thinking elements (see the Nursing Care Plan). Professional standards are especially important to consider when developing a plan of care. These standards often establish ethical or evidence-based practice guidelines for selecting effective nursing interventions.

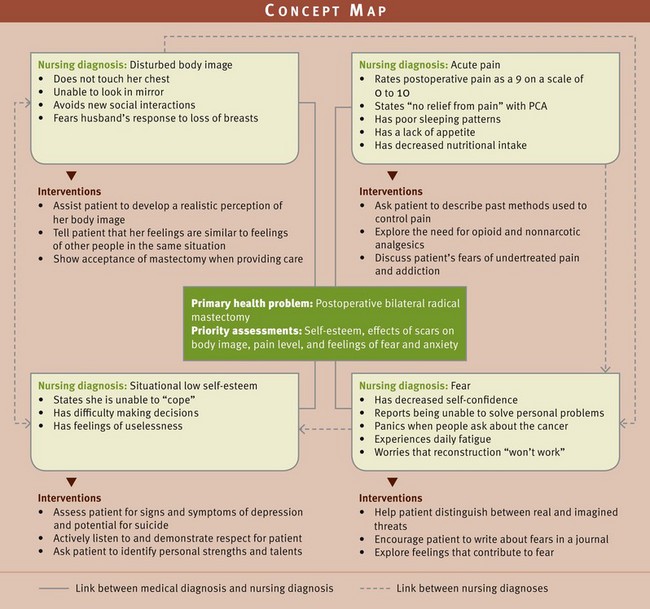

Another method to assist in planning care is a concept map. An example of an illustrative concept map (Fig. 33-6) shows the relationship of a primary health problem (postoperative bilateral radical mastectomy) and four nursing diagnoses and several interventions. The concept map shows how the nursing diagnoses are interrelated. It also assists in showing the interrelationships among nursing interventions. A single nursing intervention can be effective for more than one diagnosis.

Goals and Outcomes

Develop an individualized plan of care for each nursing diagnosis. Work collaboratively with the patient to set realistic expectations for care. Make sure that goals are individualized and realistic with measurable outcomes. In establishing goals, consult with the patient about whether they are achievable. Consultation with significant others, mental health clinicians, and community resources results in a more comprehensive and workable plan. When you set goals, consider the data necessary to demonstrate that the patient’s problem would change if the nursing diagnosis were managed. The outcome criteria should reflect these changes. For example, a patient is diagnosed with situational low self-esteem related to a recent job layoff. Establish a goal: “Patient’s self-esteem and self-concept will improve in 1 week.” Examples of expected outcomes directed toward that goal include the following:

Setting Priorities

The care plan presents the goals, expected outcomes, and interventions for a patient with an alteration in self-concept. Interventions help the patient adapt to the stressors that led to the self-concept disturbance and support and reinforce the development of coping methods. Often a patient perceives a situation as overwhelming and feels hopeless about returning to the level of previous functioning. The patient often needs time to adapt to physical changes but can work toward progressive improvement in self-concept and self-esteem.

Establishing priorities includes using therapeutic communication to address self-concept issues, which ensures that the patient’s ability to address physical needs is maximized. Look for strengths in both the individual and the family and provide resources and education to turn limitations into strengths. Patient teaching creates understanding of the normalcy of certain situations (e.g., nature of a chronic disease, change in relationships, or effect of a loss). Often, once patients understand their situations, their sense of hopelessness and helplessness is lessened.

Teamwork and Collaboration

A patient’s perceptions of significant others are important to incorporate into the plan of care. Individuals who have experienced deficits in self-concept before the current episode of treatment have often established a system of support that includes mental health clinicians, clergy, and other community resources. Before including family members, consider the patient’s desires for their involvement and cultural norms regarding who most frequently makes decisions in the family. Patients who are experiencing threats to or alterations in self-concept often benefit from collaboration with mental health and community resources to promote increased awareness. Additional resources include physical therapy, occupational therapy, behavioral health, social services, and pastoral care. Knowledge of available resources allows appropriate referrals.

Implementation

As with all the steps of the nursing process, a therapeutic nurse-patient relationship is central to the implementation phase. You develop the goals and outcome criteria and then consider nursing interventions for promoting a healthy self-concept and helping the patient move toward his or her goals. To develop effective nursing interventions, consider each nursing diagnosis and individualize interventions that address the diagnosis. Collaborating with members of the health care team maximizes the comprehensiveness of the approach to self-concept issues. Regardless of the health care setting, it is important to work with patients and their families or significant others to promote a healthy self-concept. For example, select nursing interventions that help patients regain or restore the elements that contribute to a strong and secure sense of self. The approaches chosen vary according to the level of care required.

Health Promotion

Work with patients to help them develop healthy lifestyle behaviors that contribute to a positive self-concept. Measures that support adaptation to stress such as proper nutrition, regular exercise within the patient’s capabilities, adequate sleep and rest, and stress-reducing practices contribute to a healthy self-concept. Nurses are in a unique position to identify lifestyle practices that put a person’s self-concept at risk or are suggestive of altered self-concepts. For example, a young teacher visits a clinic with complaints of being unable to sleep and experiencing anxiety attacks. In gathering the nursing history, lifestyle practices such as too little rest, a large number of life changes occurring simultaneously, and excessive use of alcohol emerge. These data, when taken together, are suggestive of actual or potential self-concept disturbances. Determine how the patient views the various lifestyle elements to facilitate his or her insight into behaviors and make referrals or provide needed health teaching.

Acute Care

In the acute care setting some patients experience potential threats to their self-concept because of the nature of the treatment and diagnostic procedures. Threats to a person’s self-concept often result in anxiety and/or fear. As a nurse, you need to address the patient’s numerous stressors, including fear of unknown diagnoses (prior to diagnostic tests), the need to modify lifestyle, and anticipated changes in functioning. In the acute care setting there is often more than one stressor, thus increasing the overall stress level for the patient and family.

Nurses in the acute care setting encounter patients who face the need to adapt to an altered body image as a result of surgery or other physical change. With shortened lengths of stay, addressing these needs is difficult to do while in an acute care setting; thus appropriate follow-up and referrals, including home care, are essential. Remain sensitive to the patient’s level of acceptance of any changes. Forcing confrontation with a change before the patient is ready likely delays the person’s acceptance. Signs that a person is receptive to accepting a change include asking questions related to how to manage a particular aspect of what has happened or looking at the changed body area. As the patient expresses readiness to integrate the body change into his or her self-concept, let him or her know about support groups that are available and offer to make the initial contact.

Restorative and Continuing Care

Often in a home care environment a nurse has more of an opportunity to work with a patient to reach the goal of attaining a more positive self-concept. Interventions designed to help a patient reach the goal of adapting to changes in self-concept or attaining a positive self-concept are based on the premise that the patient first develops insight and self-awareness concerning problems and stressors and then acts to solve the problems and cope with the stressors. One way to achieve this is by reframing the patient’s thoughts and feelings in a more positive way. Incorporate this approach into patient teaching for alterations in self-concept, including situational low self-esteem, that sometimes are present in the home care setting (Box 33-8).

Increase the patient’s self-awareness by allowing him or her to openly explore thoughts and feelings. A priority nursing intervention is the expert use of therapeutic communication skills to clarify the expectations of a patient and family. Open exploration makes the situation less threatening for a patient and encourages behaviors that expand self-awareness. Accept the patient’s thoughts and feelings nonjudgmentally, help the patient clarify interactions with others, and be empathic. Support self-expression and stress the patient’s self-responsibility.

Help the patient define problems clearly and identify positive and negative coping mechanisms. Work closely with him or her to analyze adaptive and maladaptive responses, contrast different alternatives, devise a plan, and discuss outcomes. Collaborate with the patient to identify alternative solutions and develop realistic goals to facilitate real change and encourage further goal-setting behaviors. Design opportunities that result in success, reinforce the patient’s skills and strengths, and help him or her find needed assistance. Encourage the patient to commit to decisions and actions to achieve goals by teaching him or her to move away from ineffective coping mechanisms and develop successful coping strategies. Supporting attempts that are helpful is essential because with each success a patient is able to make another attempt.

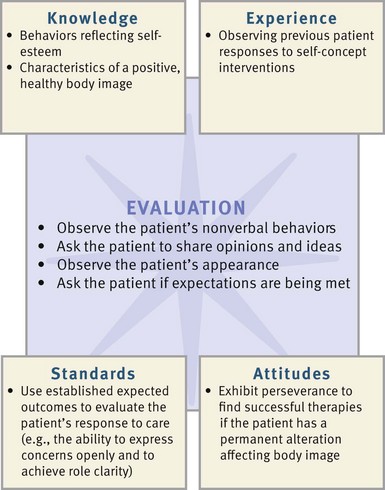

Evaluation

Use critical thinking to evaluate the patient’s perceived success in meeting each goal and the established expected outcomes (Fig. 33-7). Frequent evaluation of patient progress is necessary. Apply knowledge of behaviors and characteristics of a healthy self-concept when reviewing the actual behaviors that patients display. This determines whether outcomes have been met.

Patient Outcomes

Expected outcomes for a patient with a self-concept disturbance include nonverbal behaviors indicating a positive self-concept, statements of self-acceptance, and acceptance of change in appearance or function. Key indicators of a patient’s self-concept are nonverbal behaviors. For example, a patient who has had difficulty making eye contact demonstrates a more positive self-concept by making more frequent eye contact during conversation. Social interaction, adequate self-care, acceptance of the use of prosthetic devices, and statements indicating understanding of teaching all indicate progress. Investing in satisfying activities, exerting choices in daily life, understanding own needs during transitions, and adapting to life circumstances are evidence of self-esteem and self-efficacy in older adults (Ebersole et al., 2008). A positive attitude toward rehabilitation and increased movement toward independence facilitate a return to preexisting roles at work or at home. Patterns of interacting also reflect changes in self-concept. For example, a patient who has been hesitant to express personal views more readily offers opinions and ideas as self-esteem increases.

The goals of care sometimes become unrealistic or inappropriate as a patient’s condition changes. Revise the plan if needed, reflecting on successful experiences with other patients. Patient adaptation to major changes takes a year or longer, but the fact that this period is long does not suggest problems with adaptation. Look for signs that the patient has reduced some stressors and that some behaviors have become more adaptive. If initial outcomes regarding self-concept are not met, individualize the following questions:

• Tell me what you will do if you are not able to return to work (may substitute school or home) as planned.

• Who will you contact if you are not feeling any better about yourself in 2 weeks?

• What are you doing to actively promote improvement in your self-concept and self-esteem?

• How will you know that your self-concept and self-esteem are improving?

Changes in self-concept take time. Although change is often slow, care of a patient with a self-concept disturbance is rewarding.

Key Points

• Self-concept is an integrated set of conscious and unconscious attitudes and perceptions about self.

• Components of self-concept are identity, body image, and role performance.

• Each developmental stage involves factors that are important to the development of a healthy, positive self-concept.

• Identity is particularly vulnerable during adolescence.

• Body image is the mental picture of one’s body and is not necessarily consistent with a person’s actual body structure or physical appearance.

• Body image stressors include changes in physical appearance, structure, or functioning caused by normal developmental changes or illness.

• Self-esteem stressors include developmental and relationship changes, illness, surgery, accidents, and the responses of other individuals to changes resulting from these events.

• Role stressors, including role conflict, role ambiguity, and role strain, originate in unclear or conflicting role expectations; the effects of illness often aggravate this.

• A nurse’s self-concept and nursing actions have an effect on a patient’s self-concept.

• Planning and implementing nursing interventions for self-concept disturbance involve expanding a patient’s self-awareness, encouraging self-exploration, aiding in self-evaluation, helping formulate goals in regard to adaptation, and assisting a patient in achieving these goals.

Clinical Application Questions

Preparing for Clinical Practice

1. On the second postoperative day you enter the room and find Mrs. Johnson crying. She states that she has just gotten off the phone with her 23-year-old daughter and has agreed to care for her 3-month-old granddaughter while the daughter returns to work. You were informed in shift report that Mrs. Johnson had a restless night and has not taken pain medication since 2030. You assess that she is in moderate pain, which you immediately treat with morphine. Within 40 minutes Mrs. Johnson reports that the morphine has decreased her pain rating from a 6 to a 3 on a scale of 0 to 10 but has left her somewhat drowsy. Mrs. Johnson has shared with you some of her concerns about whether or not she can actually provide child care for her granddaughter but states, “Maybe it will make me feel worthwhile and will take my mind off of how disgusting I look.” She continues, “I just want to be normal again.” How would you address her comment regarding “being normal again” and her lack of understanding of her physical condition, including pain management, increased fatigue, and limitations regarding lifting?

2. As a part of your home care experience, you are assigned to visit Mrs. Johnson who, in addition to caring for her infant granddaughter, is also caring for her mother, who is increasingly agitated and aggressive secondary to Alzheimer’s disease. When you go to the home, you find Mrs. Johnson tearful. She says, “I can’t do this anymore. She doesn’t like anything I cook. She calls me two or three times during the night to sit with her; sometimes she doesn’t even recognize me. The baby is constantly crying; I think she senses my stress. I feel so overwhelmed.” What additional assessment data would be important to gather? What priority nursing diagnosis could be made for Mrs. Johnson?

3. You suspect that Mrs. Johnson’s depressed mood and loss of interest in usual activities exceeds your previous diagnosis of situational low self-esteem. Describe which assessment data are needed to modify your plan of care. Identify your priority actions.

![]() Answers to Clinical Application Questions can be found on the Evolve website.

Answers to Clinical Application Questions can be found on the Evolve website.

Are You Ready to Test Your Nursing Knowledge?

1. Following a bilateral mastectomy, a 50-year-old patient refuses to eat, discourages visitors, and pays little attention to her appearance. One morning the nurse enters the room to see the patient with her hair combed and makeup applied. Which of the following is the best response from the nurse?

1. “What’s the special occasion?”

2. “You must be feeling better today.”

2. A patient diagnosed with major depressive disorder has a nursing diagnosis of chronic low self-esteem related to negative view of self. Which of the following would be the most appropriate cognitive intervention by the nurse?

1. Promote active socialization with other patients

2. Role play to increase assertiveness skills

3. Several staff members complain about a patient’s constant questions such as “Should I have a cup of coffee or a cup of tea?” and “Should I take a shower now or wait until later?” Which interpretation of the patient’s behavior helps the nurses provide optimal care?

1. Asking questions is attention-seeking behavior.

2. Inability to make decisions reflects a self-concept issue.

4. A depressed patient is crying and verbalizes feelings of low self-esteem and self-worth such as “I’m such a failure … I can’t do anything right.” The best nursing response would be to:

1. Remain with the patient until he or she stops crying.

2. Tell the patient that is not true and that every person has a purpose in life.

3. Review recent behaviors or accomplishments that demonstrate skill ability.

4. Reassure the patient that you know how he is feeling and that things will get better.

5. An adult woman is recovering from a mastectomy for breast cancer and is frequently tearful when left alone. The nurse’s approach should be based on an understanding of which of the following:

1. Patients need support in dealing with the loss of a body part.

2. The patient’s family should take the lead role in providing support.

3. The nurse should explain that breast tissue is not essential to life.

4. The patient should focus on the cure of the cancer rather than loss of the breast.

6. When caring for an 87-year-old patient, the nurse needs to understand that which of the following most directly influences the patient’s current self-concept:

1. Attitude and behaviors of relatives providing care

2. Caring behaviors of the nurse and health care team

3. Level of education, economic status, and living conditions

4. Adjustment to role change, loss of loved ones, and physical energy

7. A 20-year-old patient diagnosed with an eating disorder has a nursing diagnosis of situational low self-esteem. Which of the following nursing interventions would be best to address self-esteem?

1. Offer independent decision-making opportunities

2. Review previously successful coping strategies

8. The nurse asks the patient, “How do you feel about yourself?” The nurse is assessing the patient’s:

9. The nurse can increase a patient’s self-awareness through which of the following actions? (Select all that apply.)

1. Helping the patient define her problems clearly

2. Allowing the patient to openly explore thoughts and feelings

3. Reframing the patient’s thoughts and feelings in a more positive way

4. Have family members assume more responsibility during times of stress

10. When developing an appropriate outcome for a 15-year-old girl, the nurse considers that a primary developmental task of adolescence is to:

11. An appropriate nursing diagnosis for an individual who experiences confusion in the mental picture of his physical appearance is:

12. In planning nursing care for an 85-year-old male, the most important basic need that must be met is:

13. Based on knowledge of Erikson’s stages of growth and development, the nurse plans her nursing care with the knowledge that old age is primarily focused on:

14. The home health nurse is visiting a 90-year-old man who lives with his 89-year-old wife. He is legally blind and is 3 weeks’ post right hip replacement. He ambulates with difficulty with a walker. He comments that he is saddened now that his wife has to do more for him and he is doing less for her. Which of the following is the priority nursing diagnosis?

1. Self-care deficit, toileting

2. Deficient knowledge regarding resources for the visually impaired

15. Based on knowledge of the developmental tasks of Erikson’s Industry versus Inferiority, the nurse emphasizes proper technique for use of an inhaler with a 10-year-old boy so he will:

Answers: 1. 4; 2. 3; 3. 2; 4. 1; 5. 1; 6. 4; 7. 1; 8. 2; 9. 1, 2, 3; 10. 1; 11. 2; 12. 2; 13. 4; 14. 4; 15. 1.

References

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Tobacco use among adults—United States, 2005. MMWR. 2006;55(42):1145.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Youth risk behavior surveillance—United States, 2009. MMWR. 2010;59(SS-5):1.

Ebersole, P, et al. Toward healthy aging: human needs and nursing response, ed 7. St Louis: Mosby; 2008.

Erikson, E. Childhood and society, ed 2. New York: WW Norton; 1963.

NANDA International. NANDA International nursing diagnoses: definitions and classifications, 2009-2011. Oxford, UK: Wiley-Blackwell; 2009.

Rosenberg, M. Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 1965.

Stuart, GW. Principles and practice of psychiatric nursing, ed 9. St Louis: Mosby; 2009.

Research References

Armstrong, S, Oomen-Early, J. Social connectedness, self-esteem, and depression symptomology among collegiate athletes versus nonathletes. J Am College Health. 2009;57(5):521.

Brausch, AM, Muehlenkamp, JJ. Body image and suicidal ideation in adolescents. Body Image. 2007;4(2):207.

Brunet, J, et al. Exploring a model linking social physique anxiety, drive for muscularity, drive for thinness and self-esteem among adolescent boys and girls. Body Image. 2010;7(2):137.

Carranza, FD, et al. Mexican American adolescents’ academic achievement and aspirations: the role of perceived parental educational involvement, acculturation, and self-esteem. Adolescence. 2009;44(174):313.

Croghan, IT, et al. Is smoking related to body image satisfaction, stress, and self-esteem in young girls? Am J Health Behav. 2006;30(3):322.

Davison, KK, et al. Why are early maturing girls less active: links between pubertal development, psychological well-being, and physical activity among girls ages 11 and 13. Social Sci Med. 2007;64(12):2391.

Figueroa-Hass, CL. Effect of breast augmentation mammoplasty on self-esteem and sexuality: a quantitative analysis. Plastic Surg Nurs. 2007;27(1):16.

Folse, VN, Hahn, RL. Suicide risk screening in an emergency department: engaging staff nurses in continued testing of a brief instrument. Clin Nurs Res. 2009;18(3):253.

Gearing, RE, et al. Remembering fatherhood: evaluating the impact of a group intervention on fathering. J Specialists Group Work. 2008;33(1):22.

Greene, K, Banerjee, SC. Adolescents’ responses to peer smoking offers: the role of sensation seeking and self-esteem. J Health Commun. 2008;13(3):267.

Guilamo-Ramos, V. Maternal influence on adolescent self-esteem, ethnic pride and intentions to engage in risk behavior in Latino youth. Prev Sci. 2009;10(4):366.

Jackson, LA, et al. Self-concept, self-esteem, gender, race, and information technology use. Cyberpsychol Behav. 2009;12(4):437.

Kaminski, PL, Hayslip, B. Gender differences in body esteem among older adults. J Women Aging. 2006;18(3):19.

Lai, HR, et al. The effects of a self-esteem program incorporated into health and physical education classes. J Nurs Res. 2009;17(4):233.

MacPhee, AR, Andrews, J. Risk factors for depression in early adolescence. Adolescence. 2006;41(163):435.

Martyn-Nemeth, P, et al. The relationships among self-esteem, stress, coping, eating behavior, and depressive mood in adolescents. Res Nurs Health. 2009;32(1):96.

Nelson, MC, Gordon-Larsen, P. Physical activity and sedentary behavior patterns are associated with selected adolescent risk behaviors. Pediatrics. 2006;117(4):1281.

Price, B. The older woman’s body image. Nurs Older People. 2010;22(1):31.

Sertoz, OO, et al. Body image and self-esteem in somatizing patients. Psych Clin Neurosci. 2009;63(4):508.

Stinson, DA, et al. The cost of lower self-esteem: testing a self- and social-bonds model of health. J Personality Social-Psychol. 2008;94(3):412.

Thomas, CM. The influence of self-concept on adherence to recommended health regimens in adults with heart failure. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2007;22(5):405.

Wang, F, et al. The influence of childhood obesity on the development of self-esteem. Health Rep. 2009;20(2):21.