Patient Education

• Identify the appropriate topics that address a patient’s health education needs.

• Describe the similarities and differences between teaching and learning.

• Identify the role of the nurse in patient education.

• Identify the purposes of patient education.

• Use communication principles when providing patient education.

• Describe the domains of learning.

• Identify basic learning principles.

• Discuss how to integrate education into patient-centered care.

• Differentiate factors that determine readiness to learn from those that determine ability to learn.

• Compare and contrast the nursing and teaching processes.

• Write learning objectives for a teaching plan.

• Establish an environment that promotes learning.

• Include patient teaching while performing routine nursing care.

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Potter/fundamentals/

Patient education is one of the most important roles for a nurse in any health care setting. Shorter hospital stays, increased demands on nurses’ time, an increase in the number of chronically ill patients, and the need to give acutely ill patients meaningful information quickly emphasize the importance of quality patient education. As nurses try to find the best way to educate patients, the general public has become more assertive in seeking knowledge, understanding health, and finding resources available within the health care system. Nurses provide patients with information needed for self-care to ensure continuity of care from the hospital to the home (Falvo, 2010).

Patients have the right to know and be informed about their diagnoses, prognoses, and available treatments to help them make intelligent, informed decisions about their health and lifestyle. Part of patient-centered care is to integrate educational approaches that acknowledge patients’ expertise with their own health. Creating a well-designed, comprehensive teaching plan that fits a patient’s unique learning needs reduces health care costs, improves the quality of care, and ultimately changes behaviors to improve patient outcomes. Ultimately this helps patients make informed decisions about their care and become healthier and more independent (Edelman and Mandle, 2010; Villablanca et al., 2010).

Standards for Patient Education

Patient education has long been a standard for professional nursing practice. All state Nurse Practice Acts recognize that patient teaching falls within the scope of nursing practice (Bastable, 2006). In addition, various accrediting agencies set guidelines for providing patient education in health care institutions. For example, The Joint Commission (TJC, 2011) sets standards for patient and family education. These standards require nurses and the health care team to assess patients’ learning needs and provide education about many topics, including medications, nutrition, the use of medical equipment, pain, and the patient’s plan of care. Successful accomplishment of the standards requires collaboration among health care professionals and enhances patient safety. Educational efforts should be patient-centered by taking into consideration patients’ own education and experience, their desire to actively participate in the educational process, and their psychosocial, spiritual, and cultural values. It is important to document evidence of successful patient education in patients’ medical records. Standards such as these help to direct your patient education.

Purposes of Patient Education

The goal of educating others about their health is to help individuals, families, or communities achieve optimal levels of health (Edelman and Mandle, 2010). Patient education is an essential component of providing safe, patient-centered care (QSEN, 2010). In addition, providing education about preventive health care helps reduce health care costs and hardships on individuals, families, and communities. Patients now know more about health and want to be involved in health maintenance. Provide education about health and health care in places that are convenient and familiar to patients. Comprehensive patient education includes three important purposes, each involving a separate phase of health care.

Maintenance and Promotion of Health and Illness Prevention

As a nurse you are a visible, competent resource for patients who want to improve their physical and psychological well-being. In the school, home, clinic, or workplace you provide information and skills that enable patients to assume healthier behaviors. For example, in childbearing classes you teach expectant parents about physical and psychological changes in the woman and fetal development. After learning about normal childbearing, the mother who applies new knowledge is more likely to eat healthy foods, engage in physical exercise, and avoid substances that can harm the fetus. Promoting healthy behavior through education allows patients to assume more responsibility for their health (Longo et al., 2010). Greater knowledge results in better health maintenance habits. When patients become more health conscious, they are more likely to seek early diagnosis of health problems (Hawkins et al., 2011; Redman, 2007).

Restoration of Health

Injured or ill patients need information and skills to help them regain or maintain their levels of health. Patients recovering from and adapting to changes resulting from illness or injury often seek information about their condition. For example, a woman who recently had a hysterectomy asks about her pathology reports and expected length of recovery. However, some patients find it difficult to adapt to illness and become passive and uninterested in learning. As the nurse you learn to identify patients’ willingness to learn and motivate interest in learning (Redman, 2007). The family often is a vital part of a patient’s return to health. Family caregivers often require as much education as the patient, including information on how to perform skills within the home. If you exclude the family from a teaching plan, conflicts can occur. However, do not assume that the family should be involved; assess the patient-family relationship before providing education for family caregivers.

Coping with Impaired Functions

Not all patients fully recover from illness or injury. Many have to learn to cope with permanent health alterations. New knowledge and skills are often necessary for patients to continue activities of daily living. For example, a patient loses the ability to speak after larynx surgery and has to learn new ways of communicating. Changes in function are physical or psychosocial. In the case of serious disability such as following a stroke or a spinal cord injury, the patient’s family needs to understand and accept many changes in his or her physical capabilities. The family’s ability to provide support results in part from education, which begins as soon as you identify the patient’s needs and the family displays a willingness to help. Teach family members to help the patient with health care management (e.g., giving medications through gastric tubes and doing passive range-of-motion exercises). Families of patients with alterations such as alcoholism, mental retardation, or drug dependence learn to adapt to the emotional effects of these chronic conditions and provide psychosocial support to facilitate the patient’s health. Comparing the desired level of health with the actual state of health enables you to plan effective teaching programs.

Teaching and Learning

It is impossible to separate teaching from learning. Teaching is an interactive process that promotes learning. It consists of a conscious, deliberate set of actions that help individuals gain new knowledge, change attitudes, adopt new behaviors, or perform new skills (Billings and Halstead, 2009). A teacher provides information that prompts the learner to engage in activities that lead to a desired change.

Learning is the purposeful acquisition of new knowledge, attitudes, behaviors, and skills (Bastable, 2008). Complex patterns are required if the patient is to learn new skills, change existing attitudes, transfer learning to new situations, or solve problems (Redman, 2007). A new mother exhibits learning when she demonstrates how to bathe her newborn. The mother shows transfer of learning when she uses the principles she learned about bathing a newborn when she bathes her older child. Generally teaching and learning begin when a person identifies a need for knowing or acquiring an ability to do something. Teaching is most effective when it responds to the learner’s needs (Redman, 2007). The teacher assesses these needs by asking questions and determining the learner’s interests. Interpersonal communication is essential for successful teaching to occur (see Chapter 24).

Role of the Nurse in Teaching and Learning

Nurses have an ethical responsibility to teach their patients (Heiskell, 2010). In The Patient Care Partnership, the American Hospital Association (2003) indicates that patients have the right to make informed decisions about their care. The information required to make informed decisions must be accurate, complete, and relevant to patients’ needs.

TJC’s Speak Up Initiatives helps patients understand their rights when receiving medical care (TJC, 2010). The assumption is that patients who ask questions and are aware of their rights have a greater chance of getting the care they need when they need it. The program offers the following Speak Up tips to help patients become more involved in their treatment:

• Speak up if you have questions or concerns. If you still do not understand, ask again. It is your body, and you have a right to know.

• Pay attention to the care you get. Always make sure that you are getting the right treatments and medicines by the right health care professionals. Do not assume anything.

• Educate yourself about your illness. Learn about the medical tests that are prescribed and your treatment plan.

• Ask a trusted family member or friend to be your advocate (advisor or supporter).

• Know which medicines you take and why you take them. Medication errors are the most common health care mistakes.

• Use a hospital, clinic, surgery center, or other type of health care organization that has been carefully evaluated.

• Participate in all decisions about your treatment. You are the center of the health care team.

In addition, patients are advised that they have a right to be informed about the care they will receive, obtain information about care in their preferred language, know the names of their caregivers, receive treatment for pain, receive an up-to-date list of current medications, and expect that they will be heard and treated with respect.

Teach information that patients and their families need. You frequently clarify information provided by health care providers and are the primary source of information that patients need to adjust to health problems (Bastable, 2006). However, it is also important to understand patients’ preferences for what they wish to learn. For example, a patient requests information about a new medication, or family members question the reason for their mother’s pain. Identifying the need for teaching is easy when patients request information. However, a patient’s need for teaching is often less obvious. To be an effective educator, the nurse has to do more than just pass on facts. Carefully determine what patients need to know and find the time when they are ready to learn. When nurses value and provide education, patients are better prepared to assume health care responsibilities. Nursing research about patient education supports the positive impact of patient education on patient outcomes (Box 25-1).

Teaching as Communication

The teaching process closely parallels the communication process (see Chapter 24). Effective teaching depends in part on effective interpersonal communication. A teacher applies each element of the communication process while providing information to learners. Thus the teacher and learner become involved together in a teaching process that increases the learner’s knowledge and skills.

The steps of the teaching process are similar to those of the communication process. You use patient requests for information or perceive a need for information because of a patient’s health restrictions or the recent diagnosis of an illness. Then you identify specific learning objectives to describe what the learner will be able to do after successful instruction.

The nurse is the sender who conveys a message to the patient. Many intrapersonal variables influence your style and approach. Attitudes, values, emotions, cultural perspective, and knowledge influence the way information is delivered. Past experiences with teaching are also helpful for choosing the best way to present necessary content.

The receiver in the teaching-learning process is the learner. A number of intrapersonal variables affect motivation and ability to learn. Patients are ready to learn when they express a desire to do so and are more likely to receive the message when they understand the content. Attitudes, anxiety, and values influence the ability to understand a message. The ability to learn depends on factors such as emotional and physical health, education, cultural perspective, patients’ values about their health, the stage of development, and previous knowledge.

Effective communication involves feedback. An effective teacher provides a mechanism for evaluating the success of a teaching plan and then provides positive reinforcement (Bastable, 2008; Redman, 2007). Examples of ways to evaluate teaching sessions through feedback include having a patient demonstrate a newly learned skill or asking a patient to describe how the correct dosage schedule for a new medication will be incorporated into a daily routine. Feedback needs to show the success of the learner in achieving objectives (i.e., the learner verbalizes information or provides a return demonstration of skills learned).

Domains of Learning

Learning occurs in three domains: cognitive (understanding), affective (attitudes), and psychomotor (motor skills) (Bloom, 1956; Bastable, 2008). Any health topic involves one or all domains or any combination of the three. You often work with patients who need to learn in each domain. For example, patients diagnosed with diabetes need to learn how diabetes affects the body and how to control blood glucose levels for healthier lifestyles (cognitive domain). In addition, patients begin to accept the chronic nature of diabetes by learning positive coping mechanisms (affective domain). Finally, many patients living with diabetes learn to test their blood glucose levels at home. This requires learning how to use a glucose meter (psychomotor domain). The characteristics of learning within each domain influence the teaching and evaluation methods used. Understanding each learning domain prepares the nurse to select proper teaching techniques and apply the basic principles of learning (Box 25-2).

Cognitive Learning

Cognitive learning includes all intellectual behaviors and requires thinking (Bastable, 2008). In the hierarchy of cognitive behaviors the simplest behavior is acquiring knowledge, whereas the most complex is evaluation. Cognitive learning includes the following:

• Knowledge: Learning new facts or information and being able to recall them

• Comprehension: The ability to understand the meaning of learned material

• Application: Using abstract, newly learned ideas in a concrete situation

• Analysis: Breaking down information into organized parts

• Synthesis: The ability to apply knowledge and skills to produce a new whole

• Evaluation: A judgment of the worth of a body of information for a given purpose

Affective Learning

Affective learning deals with expression of feelings and acceptance of attitudes, opinions, or values. Values clarification (see Chapter 22) is an example of affective learning. The simplest behavior in the hierarchy is receiving, and the most complex is characterizing (Krathwohl et al., 1964). Affective learning includes the following:

• Receiving: Being willing to attend to another person’s words

• Responding: Active participation through listening and reacting verbally and nonverbally

• Valuing: Attaching worth to an object or behavior demonstrated by the learner’s behavior

• Organizing: Developing a value system by identifying and organizing values and resolving conflicts

• Characterizing: Acting and responding with a consistent value system

Psychomotor Learning

Psychomotor learning involves acquiring skills that require the integration of mental and muscular activity such as the ability to walk or use an eating utensil (Redman, 2007). The simplest behavior in the hierarchy is perception, whereas the most complex is origination. Psychomotor learning includes the following:

• Perception: Being aware of objects or qualities through the use of sense organs

• Set: A readiness to take a particular action; there are three sets: mental, physical, and emotional

• Guided response: The performance of an act under the guidance of an instructor involving imitation of a demonstrated act

• Mechanism: A higher level of behavior by which a person gains confidence and skill in performing a behavior that is more complex or involves several more steps than a guided response

• Complex overt response: Smoothly and accurately performing a motor skill that requires a complex movement pattern

• Adaptation: The ability to change a motor response when unexpected problems occur

• Origination: Using existing psychomotor skills and abilities to perform a highly complex motor act that involves creating new movement patterns

Basic Learning Principles

To teach effectively and efficiently, you first need to understand how people learn (Eshleman, 2008). Motivation addresses a person’s desire or willingness to learn (Redman, 2007). The patient’s willingness to become involved in learning influences your teaching approach. Previous knowledge, experience, attitudes, and sociocultural factors influence a person’s motivation. The ability to learn depends on physical and cognitive attributes, developmental level, physical wellness, and intellectual thought processes. An ideal learning environment allows a person to attend to instruction.

A person’s learning style affects preferences for learning. People process information in the following ways: by seeing and hearing, reflecting and acting, reasoning logically and intuitively, and analyzing and visualizing. Some people learn information gradually, whereas others learn more sporadically. Effective teaching plans include a combination of approaches that meet multiple learning styles (Billings and Halstead, 2009).

Motivation to Learn

An attentional set is the mental state that allows the learner to focus on and comprehend a learning activity. Before learning anything, patients must give attention to, or concentrate on, the information to be learned. Physical discomfort, anxiety, and environmental distractions influence the ability to attend. Therefore determine the patient’s level of comfort before beginning a teaching plan and ensure that the patient is able to focus on the information.

As anxiety increases, the patient’s ability to pay attention often decreases. Anxiety is uneasiness or worry resulting from anticipating a threat or danger. When faced with change or the need to act differently, a person feels anxious. Learning requires a change in behavior and thus produces anxiety. A mild level of anxiety motivates learning. However, a high level of anxiety prevents learning from occurring. It incapacitates a person, creating an inability to focus on anything other than relieving the anxiety. Manage the patient’s anxiety (see Chapter 37) before educating to improve the patient’s comprehension and understanding of the information given (Fredericks et al., 2008).

Motivation

Motivation is a force that acts on or within a person (e.g., an idea, emotion, or a physical need) to cause the person to behave in a particular way (Redman, 2007). If a person does not want to learn, it is unlikely that learning will occur. Motivation sometimes results from a social, task mastery, or physical motive.

A social motive is a need for connection, social approval, or self-esteem. People normally seek out others with whom they can compare opinions, abilities, and emotions. For example, new parents often seek validation of ideas and parenting techniques from others whom they have identified as role models in their social environment or health care workers with whom they have established a relationship.

Task mastery motives are based on needs such as achievement and competence. For example, a high school senior who has diabetes begins to test blood glucose levels and make decisions about insulin dosages in preparation for leaving home and establishing independence. The ability to successfully manage diabetes provides the motivation to master the task or skill. After a person succeeds at a task, he or she is usually motivated to achieve more.

Often patient motives are physical. Some patients are motivated to return to a level of physical normalcy. For example, a patient with a below-the-knee amputation is motivated to learn how to walk with assistive devices. Knowledge that is necessary for survival, problem recognition, and critical decision making creates a stronger stimulus for learning than knowledge that merely promotes health (Bastable, 2006).

You assess a patient’s motivation to learn and what the patient needs to know to promote compliance with their prescribed therapy. Unfortunately not all people are interested in maintaining health. Many do not adopt new health behaviors or change unhealthy behaviors unless they perceive a disease as a threat, overcome barriers to changing health practices, and see the benefits of adopting a healthy behavior. For example, some patients with lung disease continue to smoke. No therapy has an effect unless a person believes that health is important.

Use of Theory to Enhance Motivation and Learning

Health education often involves changing attitudes and values that are not easy to change by simply teaching facts. Therefore it is important for you to use various interventions based on theory when developing patient education plans. Because of the complexity of the patient education process, different theories and models are available to guide patient education. Using a theory that matches the patient’s needs in practice will provide more effective patient education. Social learning theory provides one of the most useful approaches to patient education because it explains the characteristics of the learner and guides the educator in developing effective teaching interventions that result in enhanced learning and improved motivation (Bandura, 2001; Stonecypher, 2009).

According to social learning theory, people continuously attempt to control events that affect their lives. This allows them to attain desired outcomes and avoid undesired outcomes, resulting in improved motivation. Self-efficacy, a concept included in social learning theory, refers to a person’s perceived ability to successfully complete a task. When people believe that they are able to execute a particular behavior, they are more likely to perform the behavior consistently and correctly (Bandura, 1997).

Self-efficacy beliefs come from four sources: enactive mastery experiences, vicarious experiences, verbal persuasion, and physiological and affective states (Bandura, 1997). Understanding the four sources of self-efficacy allows you to develop interventions to help patients adopt healthy behaviors. For example, a nurse who is wishing to teach a child recently diagnosed with asthma how to correctly use an inhaler expresses personal belief in the child’s ability to use the inhaler (verbal persuasion). Then the nurse demonstrates how to use the inhaler (vicarious experience). Once the demonstration is complete, the child uses the inhaler (enactive mastery experience). As the child’s wheezing and anxiety decrease after the correct use of the inhaler, he or she experiences positive feedback, further enhancing his or her confidence to use it (physiological and affective states). Interventions such as these enhance perceived self-efficacy, which in turn improves the achievement of desired outcomes.

Self-efficacy is a concept included in many health promotion theories because it often is a strong predictor of healthy behaviors and because many interventions improve self-efficacy, resulting in improved lifestyle choices (Bandura, 1997). Because of its use in theories and research studies, many evidence-based teaching interventions include a focus on self-efficacy. When nurses implement interventions to enhance self-efficacy, their patients frequently experience positive outcomes. For example, researchers associated interventions that include self-efficacy with effective management of heart failure (While and Kiek, 2009; Yehle and Plake, 2010), participation in physical activity (Ashford et al., 2010), self-management of arthritis (Nunez et al., 2009), and improved management of asthma in children (Coffman et al., 2009).

Psychosocial Adaptation to Illness

A temporary or permanent loss of health is often difficult for patients to accept. They need to grieve, and the process of grieving gives them time to adapt psychologically to the emotional and physical implications of illness. The stages of grieving (see Chapter 36) include a series of responses that patients experience during a loss such as illness. They experience these stages at different rates and sequences, depending on their self-concept before illness, the severity of the illness, and the changes in lifestyle that the illness creates. Effective, supportive care guides the patient through the grieving process.

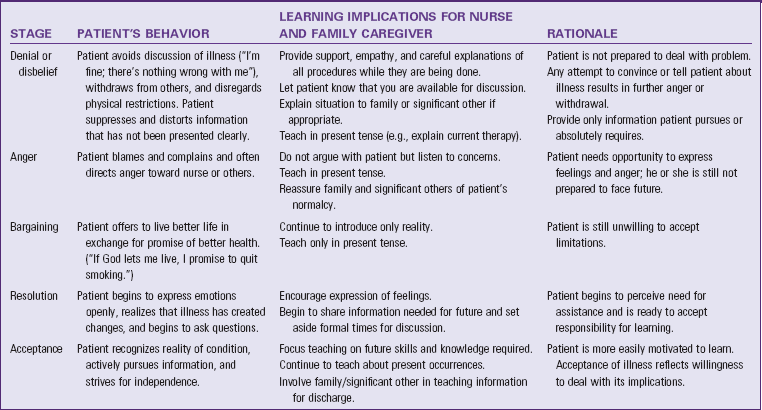

Readiness to learn is related to the stage of grieving (Table 25-1). Patients cannot learn when they are unwilling or unable to accept the reality of illness. However, properly timed teaching facilitates adjustment to illness or disability. Identify the patient’s stage of grieving on the basis of his or her behaviors. When the patient enters the stage of acceptance, the stage compatible with learning, introduce a teaching plan. Continuous assessment of the patient’s behaviors determines the stages of grieving. Teaching continues as long as the patient remains in a stage conducive to learning.

Active Participation

Learning occurs when the patient is actively involved in the educational session (Edelman and Mandle, 2010). A patient’s involvement in learning implies an eagerness to acquire knowledge or skills. It also improves the opportunity for the patient to make decisions during teaching sessions. For example, when teaching car seat safety during a parenting class, hold a teaching session in the parking lot where the participants park their cars. Encourage active participation by providing the learners with several different car seats for them to place in their cars. At the completion of this session, the parents are able to determine which type of car seat fits in their cars and which is the easiest to use. This provides participants with the information needed to purchase the appropriate car seat.

Ability to Learn

Cognitive development influences the patient’s ability to learn. You can be a competent teacher, but if you do not consider the patient’s intellectual abilities, teaching is unsuccessful. Learning, like developmental growth, is an evolving process. You need to know the patient’s level of knowledge and intellectual skills before beginning a teaching plan. Learning occurs more readily when new information complements existing knowledge. For example, measuring liquid or solid food portions requires the ability to perform mathematical calculations. Reading a medication label or discharge instructions requires reading and comprehension skills. Learning to regulate insulin dosages requires problem-solving skills.

Learning in Children

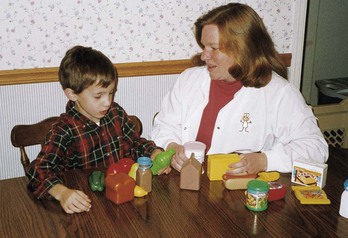

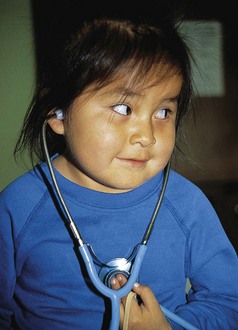

The capability for learning and the type of behaviors that children are able to learn depend on the child’s maturation. Without proper physiological, motor, language, and social development, many types of learning cannot take place. However, learning occurs in children of all ages. Intellectual growth moves from the concrete to the abstract as the child matures. Therefore information presented to children needs to be understandable, and the expected outcomes must be realistic, based on the child’s developmental stage (Box 25-3). Use teaching aids that are developmentally appropriate (Fig. 25-1). Learning occurs when behavior changes as a result of experience or growth (Hockenberry and Wilson, 2011).

Adult Learning

Teaching adults differs from teaching children. Adults are able to critically reflect on their current situation and sometimes need help to see their problems and change their perspectives (Redman, 2007). Because adults become independent and self-directed as they mature, they are often able to identify their own learning needs (Billings and Halstead, 2009). Learning needs come from problems or tasks that result from real-life situations. Although adults tend to be self-directed learners, they often become dependent in new learning situations. The amount of information provided and the amount of time that is spent with the adult patient vary, depending on the patient’s personal situation and readiness to learn. An adult’s readiness to learn is often associated with his or her developmental stage and other events that are occurring in his or her life. Resolve any needs or issues that the patient perceives as extremely important so learning can occur.

Adults have a wide variety of personal and life experiences on which to draw. Therefore enhance adult learning by encouraging them to use these experiences to solve problems (Eshleman, 2008). Furthermore, make education patient-centered by developing educational topics and goals in collaboration with the adult patient. Adult patients are ultimately responsible for changing their own behavior. Assessing what the adult patient currently knows, teaching what the patient wants to know, and setting mutual goals improve the outcomes of patient education (Bastable, 2008).

Physical Capability

The ability to learn often depends on the patient’s level of physical development and overall physical health. To learn psychomotor skills, a patient needs to possess a certain level of strength, coordination, and sensory acuity. For example, it is useless to teach a patient to transfer from a bed to a wheelchair if he or she has insufficient upper body strength. An older patient with poor eyesight or the inability to grasp objects tightly cannot learn to apply an elastic bandage. Therefore do not overestimate the patient’s physical development or status. The following physical characteristics are necessary to learn psychomotor skills:

• Size (height and weight match the task to perform or the equipment to use [e.g., crutch walking])

• Strength (ability of the patient to follow a strenuous exercise program)

• Coordination (dexterity needed for complicated motor skills such as using utensils or changing a bandage)

• Sensory acuity (visual, auditory, tactile, gustatory, and olfactory; sensory resources needed to receive and respond to messages taught)

Any condition (e.g., pain or fatigue) that depletes a person’s energy also impairs the ability to learn. For example, a patient who spends a morning having rigorous diagnostic studies is unlikely to be able to learn because of fatigue. Postpone teaching when an illness becomes aggravated by complications such as a high fever or respiratory difficulty. After working with a patient, assess the patient’s energy level by noting the patient’s willingness to communicate, the amount of activity initiated, and his or her responsiveness toward questions. Temporarily stop teaching if the patient needs rest. You achieve greater teaching success when patients are physically able to actively participate in learning.

Learning Environment

Factors in the physical environment where teaching takes place make learning either a pleasant or a difficult experience (Bastable, 2008). The ideal setting helps the patient focus on the learning task. The number of persons that the nurse teaches, the need for privacy, the room temperature, the room lighting, noise, the room ventilation, and the room furniture are important factors when choosing the setting. The ideal environment for learning is a room that is well lit and has good ventilation, appropriate furniture, and a comfortable temperature. A darkened room interferes with the patient’s ability to watch your actions, especially when demonstrating a skill or using visual aids such as posters or pamphlets. A room that is cold, hot, or stuffy makes the patient too uncomfortable to focus on the information being presented.

It is also important to choose a quiet setting. A quiet setting offers privacy; infrequent interruptions are best. Provide privacy even in a busy hospital by closing cubicle curtains or taking the patient to a quiet spot. Family caregivers often need to share in discussions in the home. However, patients who are reluctant to discuss the nature of the illness when others are in the room benefit from receiving education in a room separate from household activities such as a bedroom.

Teaching a group of patients requires a room that allows everyone to be seated comfortably and within hearing distance of the teacher. Make sure that the size of the room does not overwhelm the group. Arranging the group to allow participants to observe one another further enhances learning. More effective communication occurs as learners observe others’ verbal and nonverbal interactions.

Nursing Process

Apply the nursing process and use a critical thinking approach in your care of patients. The nursing process provides a clinical decision-making approach for you to develop and implement an individualized plan of care. A relationship exists between the nursing and teaching processes (Redman, 2007). During the assessment phase of the nursing process, determine the patient’s health care needs (see Unit 3). At times assessment reveals a patient’s need for health care information. Individualize nursing diagnoses to a patient’s situation and establish a plan of care to meet desired goals and outcomes and prescribe evidence-based nursing interventions for improving or maintaining a patient’s health. Evaluation determines the level of success in meeting goals of care.

While diagnosing a patient’s health care problems, you often identify the need for education. When education becomes a part of the care plan, the teaching process begins. Like the nursing process, the teaching process requires assessment—in this case, analyzing the patient’s learning needs, motivation, and ability to learn. A diagnostic statement specifies the information or skills that the patient requires. Develop specific learning objectives, implement appropriate patient-centered teaching strategies, and use learning principles to ensure that the patient acquires the necessary knowledge and skills. Finally, the teaching process requires an evaluation of learning based on learning objectives.

The nursing and teaching processes are not the same. The nursing process requires assessment of all sources of data to determine a patient’s total health care needs. The teaching process focuses on the patient’s learning needs and willingness and capability to learn. Table 25-2 compares the teaching and nursing processes.

TABLE 25-2

Comparison of the Nursing and Teaching Processes

| BASIC STEPS | NURSING PROCESS | TEACHING PROCESS |

| Assessment | Collect data about patient’s physical, psychological, social, cultural, developmental, and spiritual needs from patient, family, diagnostic tests, medical record, nursing history, and literature. | Gather data about patient’s learning needs, motivation, ability to learn, and teaching resources from patient, family, learning environment, medical record, nursing history, and literature. |

| Nursing diagnosis | Identify appropriate nursing diagnoses based on assessment findings. | Identify patient’s learning needs on basis of three domains of learning. |

| Planning | Develop an individualized care plan. Set diagnosis priorities based on patient’s immediate needs, expected outcomes, and patient-centered goals. Collaborate with patient on care plan. | Establish learning objectives stated in behavioral terms. Identify priorities regarding learning needs. Collaborate with patient about teaching plan. Identify type of teaching method to use. |

| Implementation | Perform nursing care therapies. Include patient as active participant in care. Involve family/significant other in care as appropriate. | Implement teaching methods. Actively involve patient in learning activities. Include family caregiver as appropriate. |

| Evaluation | Identify success in meeting desired outcomes and goals of nursing care. Alter interventions as indicated when goals are not met. | Determine outcomes of teaching-learning process. Measure patient’s achievement of learning objectives. Reinforce information as needed. |

Assessment

When providing patient education, it is important to partner with the patient to ensure safe, compassionate, and coordinated care (QSEN, 2010). During the assessment process, thoroughly assess a patient and critically analyze your findings to ensure that you make patient-centered clinical decisions required for safe nursing care. To be successful in teaching a patient, you need to assess all factors influencing the choice of relevant content, the patient’s ability to learn, and the resources available for instruction. By seeing health care situations “through patients’ eyes,” you gain a better appreciation of their knowledge, expectations, and preferences for learning. Learning needs, identified by both you and a patient, determine the choice of teaching content. An effective assessment provides the basis for individualized patient teaching (Olsen, 2010). Box 25-4 summarizes examples of specific assessment questions to use in determining a patient’s unique learning needs.

Sometimes nurses use formal educational assessment tools to determine their patients’ perceived learning needs. Other times they simply identify their patients’ expectations during routine assessments. Patients identify their own learning needs based on the implications of living with their illness. To meet these learning needs, assess what patients view as important information to know. When a patient feels a need to know something, he or she is likely to be receptive to information presented. For example, many parents need to know how to care for their new baby. Therefore they are often very receptive to information about baby care (e.g., how to feed the baby and make sure that he or she gets enough sleep).

Learning Needs: Determine information that is critical for patients to learn. Learning needs change, depending on a patient’s current health status. Because the health status is dynamic, assessment is an ongoing activity. Assess the following:

• Information or skills needed by the patient to perform self-care and to understand the implications of a health problem—Health care team members anticipate learning needs related to specific health problems. For example, you teach a young man who has just entered high school how to perform testicular self-examination.

• Patient experiences (e.g., new or recurring problem, past hospitalization) that influence the need to learn

• Information that family caregivers require to support the patient’s needs—The amount of information needed depends on the extent of the family member’s role in helping the patient.

Motivation to Learn: Ask questions that identify and define the patient’s motivation. These questions help to determine if the patient is prepared and willing to learn. Assess the following motivational factors:

• Behavior (e.g., attention span, tendency to ask questions, memory, and ability to concentrate during the teaching session)

• Health beliefs and sociocultural background—Sociocultural norms, values, and traditions all influence a patient’s beliefs and values about health and various therapies, communication patterns, and perceptions of time (see Chapter 9).

• Perception of the severity and susceptibility of a health problem and the benefits and barriers to treatment

• Perceived ability to perform health behaviors

• Attitudes about health care providers (e.g., role of patient and nurse in making decisions)

• Learning style preference—Patients who are visual learners learn best when you use pictures and diagrams to explain information. Patients who prefer auditory learning are distracted by pictures and prefer listening to information (e.g., podcasts). Kinesthetic learners learn best while they are moving and participating in hands-on activities. Demonstrations and role playing work well with these learners (Eshleman, 2008). Patients who learn best by reasoning logically and intuitively learn better if presented with a case study that requires careful analysis and discussion with others to arrive at conclusions.

Ability to Learn: Determine the patient’s physical and cognitive ability to learn. Health care providers often underestimate patients’ cognitive deficits. Many factors impair the ability to learn, including fatigue, body temperature, electrolyte levels, oxygenation status, and blood glucose level. In any health care setting several of these factors often influence a patient at the same time. Assess the following factors related to the ability to learn:

• Physical strength, endurance, movement, dexterity, and coordination—Determine the extent to which the patient can perform skills. For example, have the patient manipulate equipment that will be used in self-care at home.

• Sensory deficits (see Chapter 49) that affect the patient’s ability to understand or follow instruction

• Patient’s reading level—This is often difficult to assess because patients who are functionally illiterate are often able to conceal it by using excuses such as not having the time or not being able to see. One way to assess a patient’s reading level and level of understanding is to ask the patient to read instructions from an educational handout and then explain their meaning (see the discussion of health literacy, p. 337).

• Patient’s developmental level—This influences the selection of teaching approaches (see Box 25-3).

• Patient’s cognitive function, including memory, knowledge, association, and judgment

• Pain, fatigue, anxiety, or other physical symptoms that interfere with the ability to maintain attention and participate—In acute care settings a patient’s physical condition can easily prevent a patient from learning.

Teaching Environment: The environment for a teaching session needs to be conducive to learning. Assess the following environmental factors:

Resources for Learning: A patient frequently requires the support of family members or significant others. If this support is necessary, assess the readiness and ability of a family caregiver to learn the information necessary for the care of the patient. Also review resources within the home environment. Assess the following:

• Patient’s willingness to have family caregivers involved in the teaching plan and provide health care—Information about the patient’s health care is confidential unless the patient chooses to share it. Sometimes it is difficult for the patient to accept the help of family caregivers, especially when bodily functions are involved.

• Family caregiver’s perceptions and understanding of the patient’s illness and its implications—Family caregivers’ perceptions should match those of the patient; otherwise conflicts occur in the teaching plan.

• Family caregiver’s willingness and ability to participate in care—If the patient chooses to share information about his or her health status with family members, they need to be responsible, willing, and physically and cognitively able to assist in care activities such as bathing or administering medications. Not all family members meet these requirements.

• Resources—These include financial or material resources such as having the ability to obtain health care equipment.

• Teaching tools, including brochures, audiovisual materials, or posters—Printed material needs to present current information that is written clearly and logically and matches the patient’s reading level.

Health Literacy and Learning Disabilities: Current research shows that health literacy is a strong predictor of a person’s health status (Kim and Yu, 2010; Wolf et al., 2010). The World Health Organization (2011) defines health literacy as the cognitive and social skills that determine the motivation and ability of individuals to gain access to, understand, and use information in ways that promote and maintain good health. Health literacy includes patients’ reading and mathematics skills, comprehension, ability to make health-related decisions, and successful functioning as a consumer of health care (Speros, 2005). Persons most likely to be at risk for low health literacy include the elderly (age 65 years and older), minority populations, immigrant populations, persons of low income (approximately half of Medicare/Medicaid recipients read below the fifth-grade level), and people with chronic mental and/or physical health conditions (National Network of Libraries of Medicine, 2011).

Functional illiteracy, the inability to read above a fifth-grade level, is a major problem in America today. The National Assessment of Adult Literacy Survey (NAALS), conducted in 2003 by the National Center for Education Statistics, assessed the extent of literacy skills in Americans over the age of 16 (Kutner et al., 2006). Results from the NAALS reflected that over 75 million American adults had basic or below-basic levels of health literacy. Approximately 14% of adults could not understand a basic patient education pamphlet, and 36% could not perform moderately difficult tasks (e.g., reading a childhood vaccination chart or determining possible medication interactions from a prescription label). Older adults, men, people who did not speak English before entering school, people living below poverty level, and people without a high school education tended to have lower health literacy scores. White and Asian/Pacific Islander adults had higher literacy levels than African American, Native American/Alaska Native, and multiracial adults. Hispanic adults had the lowest levels of health literacy.

To compound the problem, the readability of printed health education material ranges from elementary school to college level. Currently printed educational materials are often above the patient’s reading level (Clauson et al., 2010; MacDonald et al., 2010). Removing medical terms from health information lowers the reading level, but this often does not bring it to an acceptable level. Unfortunately health care professionals do not always address the gap between the patient’s reading level and the readability of educational materials (Attwood, 2008; Rothman et al., 2009). This results in unsafe care. To ensure patient safety, all health care providers need to ensure that information is presented clearly and in a culturally sensitive manner (TJC, 2010).

Because health literacy influences how you deliver teaching strategies, it is critical for you to assess a patient’s health literacy before providing instruction. Assessing health literacy is challenging, especially in busy clinical settings where there is often little time to conduct a thorough health literacy assessment. However, all health care providers need to identify problems and provide appropriate education to people who have special health literacy needs (TJC, 2010). Research shows that many Americans read and understand information that is 3 to 5 years below their last year of formal education.

Try asking patients to perform simple literacy skills. For example, can a patient read back to you a medication label correctly? After you give a simple 1-minute explanation of a diet or exercise program, can the patient explain it back to you? Can a patient correctly describe in his or her own words the information in a written handout? Most people with low health literacy say they are good readers even if they cannot read (Lee et al., 2010). You can use a variety of screening tools to test literacy. The Wide Range Achievement Test (WRAT 3) evaluates reading, spelling, and arithmetic skills for patients from 5 to 74 years of age. The Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine (REALM) uses pronunciation of health care terms to determine approximate reading level. The Cloze test, a test of reading comprehension, asks patients to fill in the blanks that are in a written paragraph. You also need to assess the patient’s ability to understand mathematical calculations in addition to reading skills.

In addition to illiteracy, assess patients for learning disabilities that impair the ability to learn. For example, many self-care behaviors require an understanding of mathematics, including computation and fractions. If a patient’s learning disability impairs the ability to effectively use mathematics skills, teaching is challenging, especially when trying to teach him or her about complex medication dosages and frequencies. Another learning disability that affects a patient’s ability to learn includes attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Patients with ADHD frequently have a low threshold of frustration and difficulty recalling information and staying focused during educational sessions.

Patients who have low health literacy or learning disabilities may be ashamed of not being able to understand you and often try to mask their inability to comprehend information. Therefore make sure that you are sensitive and maintain a therapeutic relationship with your patients while assessing their ability to learn. Appreciating the unique qualities of your patients helps to ensure safe and effective patient care (QSEN, 2010).

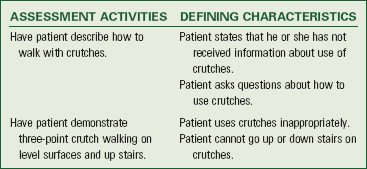

Nursing Diagnosis

After assessing information related to the patient’s ability and need to learn, interpret data and cluster-defining characteristics to form diagnoses that reflect his or her specific learning needs (Box 25-5). This ensures that teaching will be goal directed and individualized. If a patient has several learning needs, the nursing diagnoses guide priority setting. When the nursing diagnosis is deficient knowledge, the diagnostic statement describes the specific type of learning need and its cause (e.g., deficient knowledge regarding psychomotor learning related to inexperience with medication self-administration). Classifying diagnoses by the three learning domains helps you to focus specifically on subject matter and teaching methods. Patients often require education to support resolution of their various health problems. Examples of nursing diagnoses that indicate a need for education include the following:

• Deficient knowledge (affective, cognitive, psychomotor)

• Ineffective health maintenance

• Ineffective family therapeutic regimen management

When you can manage or eliminate health care problems through education, the related factor of a diagnostic statement is deficient knowledge. For example, an older adult is having difficulty managing a medication regimen that involves a number of newly prescribed medications she has to take at different times of the day. The nursing diagnosis is Ineffective self-health management related to deficient knowledge. In this case educating the patient about her medications and the correct dosage schedules improves her ability to schedule and take them as directed. When you identify conditions that cause barriers to effective learning (e.g., nursing diagnosis of acute pain or activity intolerance), teaching is inappropriate. In these cases delay teaching until the nursing diagnosis is resolved or the health problem controlled.

Planning

After determining the nursing diagnoses that identify a patient’s learning needs, develop a teaching plan, determine goals and expected outcomes, and involve the patient in selecting learning experiences (see the Nursing Care Plan). Expected outcomes (or learning objectives) guide the choice of teaching strategies and approaches with a patient. Patient participation ensures a more relevant, meaningful plan.

Goals and Outcomes: Goals of patient education indicate that a patient achieves a better understanding of the information provided and is able to attain health or better manage illness. If possible, include the patient when establishing learning goals and outcomes and serve as a resource in setting the minimum criteria for success. Outcomes often describe a behavior that identifies the patient’s ability to do something on completion of teaching such as will empty colostomy bag, or will administer an injection. When developing outcomes, conditions or time frames need to be realistic and meet the patient’s needs (e.g., “will identify the side effects of aspirin by discharge”). Consider conditions under which the patient or family will typically perform the behavior (e.g., “will walk from bedroom to bathroom using crutches”).

In some health care settings nurses develop written teaching plans. The teaching plan includes topics for instruction, resources (e.g., equipment, teaching booklets, and referrals to special educational programs), recommendations for involving family, and objectives of the teaching plan. Some plans are very detailed, whereas others are in outline form. Use the plan to provide continuity of instruction. The more specific the plan, the easier it is to follow.

The setting influences the complexity of any teaching plan. In an acute care setting plans are concise and focused on the primary learning needs of the patient because there is limited time for teaching. Home care and outpatient clinic teaching plans are usually more comprehensive in scope because you often have more time to instruct patients and patients are often less anxious in outpatient settings.

Setting Priorities: Include the patient when determining priorities for patient education. Base priorities on the patient’s immediate needs, nursing diagnoses, and the goals and outcomes established for him or her. Priorities also depend on what the patient perceives to be most important, his or her anxiety level, and the amount of time available to teach. A patient’s learning needs are set in order of priority. For example, a patient recently diagnosed with coronary artery disease has deficient knowledge related to the illness and its implications. The patient benefits most by first learning about the correct way to take nitroglycerin and how long to wait before calling for help when chest pain occurs. Once you assist in meeting patient needs related to basic survival, you can discuss other topics such as exercise and nutritional changes.

Timing: When is the right time to teach? Before a patient enters a hospital? When a patient first enters a clinic? At discharge? At home? Each is appropriate because patients continue to have learning needs and opportunities as long as they stay in the health care system. Plan teaching activities for a time when the patient is most attentive, receptive, and alert and organize the patient’s activities to provide time for rest and teaching-learning interactions.

Timing is sometimes difficult because the emphasis is often on a patient’s early discharge from a hospital. For example, it takes several days after surgery for a patient to be alert and comfortable enough to learn. By the time a patient feels ready to learn, sometimes discharge is already scheduled. Therefore, to improve patient outcomes, anticipate patients’ educational needs before they occur.

Although prolonged sessions cause concentration and attentiveness to decrease, make sure that teaching sessions are not too brief. The patient needs time to comprehend the information and give feedback. It is easier for him or her to tolerate and retain interest in the material during frequent sessions lasting 10 to 15 minutes. However, factors such as shorter hospital stays and lack of insurance reimbursement for outpatient education sessions often necessitate longer teaching sessions.

The frequency of sessions depends on the learner’s abilities and the complexity of the material. For example, a child newly diagnosed with diabetes requires more visits to an outpatient center than the older adult who has had diabetes for 15 years and lives in a nursing home. Make sure that intervals between teaching sessions are not so long that the patient forgets information. Home care nurses frequently reinforce learning during home visits when patients are discharged from the hospital.

Organizing Teaching Material: An effective teacher carefully considers the order of information to present. When a nurse has an ongoing relationship with a patient, as in the case of home health or case management, an outline of content helps organize information into a logical sequence. Material needs to progress from simple to complex ideas because a person must learn the simple facts and concepts before learning how to make associations or complex interpretations of ideas. Staff nurses in an acute care setting will often focus on the simpler, more essential concepts, whereas home health nurses can better address complex issues. For example, to teach a woman how to feed her husband who has a gastric tube, the nurse first teaches the wife how to measure the tube feeding and manipulate the equipment. Once the wife has accomplished this, the process of administering the feeding occurs.

Begin instruction with essential content because patients are more likely to remember information that you teach early in the teaching session. For example, immediately after surgical removal of a malignant breast tumor, the patient has many learning needs. Start with essential information such as how to monitor the incision site for signs of infection; deal with the emotional aspects of a cancer diagnosis and complete the teaching session with informative but less critical content, including the warning signs of cancer. Repetition reinforces learning. A concise summary of key topics helps the learner remember the most important information (Bastable, 2008).

Teamwork and Collaboration: During planning choose appropriate teaching methods, encourage the patient to offer suggestions, and make referrals to other health care professionals (e.g., dietitians and physical, speech, or occupational therapists) when appropriate. The nurse is the member of the health care team primarily responsible for ensuring that all patient educational needs are met. However, sometimes patient needs are highly complex. In these cases identify appropriate health education resources within the health care system or the community during planning. Examples of resources for patient education include diabetes education clinics, cardiac rehabilitation programs, prenatal classes, and support groups. When patients receive education and support from these types of resources, the nurse obtains a referral order when necessary, encourages patients to attend educational sessions, and reinforces information taught. Resources that specialize in a particular health need (e.g., wound care or ostomy specialists) are integral to successful patient education.

Implementation

The implementation of patient education depends on your ability to critically analyze assessment data when identifying learning needs and developing the teaching plan (see Care Plan). Carefully evaluate the learning objectives and determine which teaching and learning principles most effectively and efficiently assist the patient in meeting expected goals and outcomes. Implementation involves believing that each interaction with a patient is an opportunity to teach. Use evidence-based interventions to create an effective learning environment.

Maintaining Learning Attention and Participation: Active participation is key to learning. Persons learn better when more than one of the senses is stimulated. Audiovisual aids and role play are good teaching strategies. By actively experiencing a learning event, the person is more likely to retain knowledge. A teacher’s actions also increase learner attention and interest. When conducting a discussion with a learner, the teacher stays active by changing the tone and intensity of his or her voice, making eye contact, and using gestures that accentuate key points of discussion. An effective teacher engages learners and talks and moves among a group rather than remaining stationary behind a lectern or table. A learner remains interested in a teacher who is actively enthusiastic about the subject under discussion.

Building on Existing Knowledge: A patient learns best on the basis of preexisting cognitive abilities and knowledge. Thus a teacher is more effective when he or she presents information that builds on a learner’s existing knowledge. A patient quickly loses interest if a nurse begins with familiar information. For example, a patient who has lived with multiple sclerosis for several years is beginning a new medication that is given subcutaneously. Before teaching the patient how to prepare the medication and give the injection, the nurse asks him or her about previous experience with injections. On assessment the nurse learns that the patient’s father had diabetes and the patient administered the insulin injections. The nurse individualizes the teaching plan by building on the patient’s previous knowledge and experience with insulin injections.

Teaching Approaches: A nurse’s approach in teaching is different from teaching methods. Some situations require a teacher to be directive. Others require a nondirective approach. An effective teacher concentrates on the task and uses teaching approaches according to the learner’s needs. A learner’s needs and motives frequently change over time. Thus the effective teacher is always aware of the need to modify teaching approaches.

Telling: Use the telling approach when teaching limited information (e.g., preparing a patient for an emergent diagnostic procedure). If a patient is highly anxious but it is vital for information to be given, telling is effective. When using telling, the nurse outlines the task the patient will perform and gives explicit instructions. There is no opportunity for feedback with this method.

Participating: In the participating approach the nurse and patient set objectives and become involved in the learning process together. The patient helps decide content, and the nurse guides and counsels the patient with pertinent information. In this method there is opportunity for discussion, feedback, mutual goal setting, and revision of the teaching plan. For example, a parent caring for a child with leukemia learns how to care for the child at home and recognize problems that need to be reported immediately. The parent and nurse collaborate on developing an appropriate teaching plan. After each teaching session is completed, the parent and nurse review the objectives together, determine if the objectives were met, and plan what will be covered in the next session.

Entrusting: The entrusting approach provides the patient the opportunity to manage self-care. The patient accepts responsibilities and performs tasks correctly and consistently. The nurse observes the patient’s progress and remains available to assist without introducing more new information. For example, a patient has been managing diabetes well for 10 years. Because of the development of a complication, the patient now has to walk instead of jog during exercise. The patient understands how to adjust insulin when exercising to prevent hypoglycemia. The nurse instructs the patient about the newly prescribed exercise therapy and allows him or her to adjust insulin dosages independently.

Reinforcing: Reinforcement requires using a stimulus that increases the probability for a response. A learner who receives reinforcement before or after a desired learning behavior is likely to repeat the behavior. Feedback is a common form of reinforcement. Reinforcers are positive or negative. Positive reinforcement such as a smile or spoken approval produces desired responses. Although negative reinforcement such as frowning or criticizing decreases an undesired response, people usually respond better to positive reinforcement (Bastable, 2008). The effects of negative reinforcement are less predictable and often undesirable.

Three types of reinforcers are social, material, and activity. When a nurse works with a patient, most reinforcers are social, used to acknowledge a learned behavior (e.g., smiles, compliments, or words of encouragement). Examples of material reinforcers are food, toys, and music. These work best with young children. Activity reinforcers rely on the principle that a person is motivated to engage in an activity if he or she has the opportunity to engage in a more desirable activity after completion of the task. For example, a patient is more likely to go to a mental health counseling session if he or she is given the chance to go outside for a walk afterward.

Choosing an appropriate reinforcer involves giving careful thought and attention to individual preferences. Observing behavior often helps reveal the best reinforcer to use. Do not use reinforcers as threats. They are not effective with every patient. A young child responds more to social reinforcers than do older children or adults. In adults reinforcement is more effective when the nurse establishes a therapeutic relationship with the patient.

Incorporating Teaching with Nursing Care: Many nurses find that they are able to teach more effectively while delivering nursing care. This becomes easier as you gain confidence in your clinical skills. For example, while hanging blood you explain to the patient why the blood is necessary and the symptoms of a transfusion reaction that need to be reported immediately. Another example is explaining the side effects of a medication while administering it. An informal, unstructured style relies on the positive therapeutic relationship between nurse and patient, which fosters spontaneity in the teaching-learning process. Teaching during routine care is efficient and cost-effective (Fig. 25-2).

Instructional Methods: Choose instructional methods that match a patient’s learning needs, the time available for teaching, the setting, the resources available, and your comfort level with teaching. Skilled teachers are flexible in altering teaching methods according to the learner’s responses. An experienced teacher uses a variety of techniques and teaching aids. Do not expect to be an expert educator when first entering nursing practice. Learning to become effective in teaching takes time and practice.

When first starting to teach patients, it helps to remember that patients perceive you as an expert. However, this does not mean that they expect you to have all of the answers. It simply means that they expect that you will keep them appropriately informed. Effective nurses keep the teaching plan simple and focused on patients’ needs.

One-on-One Discussion: Perhaps the most common method of instruction is one-on-one discussion. When teaching a patient at the bedside, in a physician’s office, or in the home, the nurse shares information directly. You usually give information in an informal manner, allowing the patient to ask questions or share concerns. Use various teaching aids such as models or diagrams during the discussion, depending on the patient’s learning needs. Use unstructured and informal discussions when helping patients understand the implications of illness and ways to cope with health stressors.

Group Instruction: Some nurses choose to teach patients in groups because of the advantages associated with group teaching. Groups are an economical way to teach a number of patients at one time, and patients are able to interact with one another and learn from the experiences of others. Learning in a group of six or less is more effective and avoids outburst behaviors. Groups also foster the development of positive attitudes that help patients meet learning objectives (Bezalel et al., 2010). Group instruction often involves both lecture and discussion. Lectures are highly structured and efficient in helping groups of patients learn standard content about a subject. A lecture does not ensure that learners are actively thinking about the material presented; thus discussion and practice sessions are essential. After a lecture, learners need the opportunity to share ideas and seek clarification. Group discussions allow patients and families to learn from one another as they review common experiences. A productive group discussion helps participants solve problems and arrive at solutions toward improving each member’s health. To be an effective group leader, the nurse guides participation. Acknowledging a look of interest, asking questions, and summarizing key points foster group involvement. However, not all patients benefit from group discussions, and sometimes the physical or emotional level of wellness makes participation difficult or impossible.

Preparatory Instruction: Patients frequently face unfamiliar tests or procedures that create significant anxiety. Providing information about procedures often decreases anxiety because patients have a better idea of what to expect during the procedure, which helps to give them a sense of control. The known is less threatening than the unknown. Use the following guidelines for giving preparatory explanations:

• Describe physical sensations during a procedure. For example, when drawing a blood specimen, explain that the patient will feel a sticking sensation as the needle punctures the skin.

• Describe the cause of the sensation, preventing misinterpretation of the experience. For example, explain that a needlestick burns because the alcohol used to clean the skin enters the puncture site.

• Prepare patients only for aspects of the experience that others have commonly noticed. For example, explain that it is normal for a tight tourniquet to cause a person’s hand to tingle and feel numb.

Demonstrations: Use demonstrations when teaching psychomotor skills such as preparation of a syringe, bathing an infant, crutch walking, or taking a pulse. Demonstrations are most effective when learners first observe the teacher and then, during a return demonstration, have the chance to practice the skill. Combine a demonstration with discussion to clarify concepts and feelings. An effective demonstration requires advanced planning:

1. Be sure that the learner can easily see each step of the demonstration. Position the learner to provide a clear view of the skill being performed.

2. Assemble and organize the equipment. Make sure that all equipment works.

3. Perform each step slowly and accurately in sequence while analyzing the knowledge and skills involved and allow the patient to handle the equipment

4. Review the rationale and steps of the procedure.

5. Encourage the patient to ask questions so he or she understands each step.

6. Judge proper speed and timing of the demonstration based on the patient’s cognitive abilities and anxiety level.

7. To demonstrate mastery of the skill, have the patient perform a return demonstration under the same conditions that will be experienced at home or in the place where the skill is to be performed. For example, when a patient needs to learn to walk with crutches, the nurse simulates the home environment. If the patient’s home has stairs, the patient practices going up and down a staircase in the hospital.

Analogies: Learning occurs when a teacher translates complex language or ideas into words or concepts that the patient understands. Analogies supplement verbal instruction with familiar images that make complex information more real and understandable. For example, when explaining arterial blood pressure, use an analogy of the flow of water through a hose. Follow these general principles when using analogies:

Role Play: During role play people are asked to play themselves or someone else. Patients learn required skills and feel more confident in being able to perform them independently. The technique involves rehearsing a desired behavior. For example, a nurse who is teaching a parent how to respond to a child’s behavior pretends to be a child who is having a temper tantrum. The parent responds to the nurse who is pretending to be the child. Afterward the nurse evaluates the parent’s response and determines whether an alternative approach would have been more appropriate.

Simulation: Simulation is a useful technique for teaching problem solving, application, and independent thinking. During individual or group discussion you pose a pertinent problem or situation for patients to solve. For example, patients with heart disease plan a meal that is low in cholesterol and fat. The patients in the group decide which foods are appropriate. You ask the group members to present their diet, providing an opportunity to identify mistakes and reinforce correct information.

Illiteracy and Other Disabilities: It is important to use words that a patient is able to understand. Medical jargon is confusing. Implications of low health literacy, illiteracy, and learning disabilities include an impaired ability to analyze instructions or synthesize information. In addition, many of these patients have not acquired the problem-solving skills of drawing conclusions and inferences from experience, and they do not ask questions to obtain or clarify information that has been presented. Box 25-6 summarizes nursing interventions that nurses use when caring for patients who have literacy or learning disability problems.

Sometimes patients have sensory deficits that affect how the nurse presents information (see Chapter 49). For example, patients who are deaf require a sign language interpreter. Not all people who are deaf read lips. Therefore it is very important to provide clear written materials that match the patients’ reading level. Visual impairments also impact the teaching strategy used by the nurse. Many people who are blind have acute listening skills. Avoid shouting and announce your presence to patients with visual impairments before approaching them. If the patient has partial vision, use colors and a print font size (14-point font or greater) that the patient is able to see. Be sure to use proper lighting. Other helpful interventions include audiotaping teaching sessions and providing structured, well-organized instructions (Bastable, 2008).

Cultural Diversity: You must have knowledge of a patient’s cultural background and beliefs and his or her ability to understand instructions in a language different from his or her native language (see Chapter 9 and Box 25-7). Cultural diversity poses a great challenge when you are trying to provide culturally sensitive care. When educating patients of different ethnic groups, be aware of the distinctive aspects of each culture, being careful not to stereotype patients (Campinha-Bacote, 2009). Collaborate with other nurses and educators to present appropriate teaching approaches, and ask the people in the cultural group to help by sharing their values and beliefs. Ethnic nurses are excellent resources who are able to provide input through their experiences to improve the care provided to members of their own community (Bastable, 2008). When patients cannot understand English, use trained and certified health care interpreters to provide health care information.

In addition, be aware of intergenerational conflict of values. This occurs when immigrant parents uphold their traditional values and their children, who are exposed to American values in social encounters, develop beliefs similar to those of their American peers. Consider this conflict in values when providing information to families or groups who have members from different generations. To enhance patient education in culturally diverse populations, know when and how to provide education while respecting cultural values. Modify teaching regarding interventions or desired behaviors to accommodate for cultural differences. Effective educational strategies often require the nurse to use different patterns of communication (Campinha-Bacote, 2009).

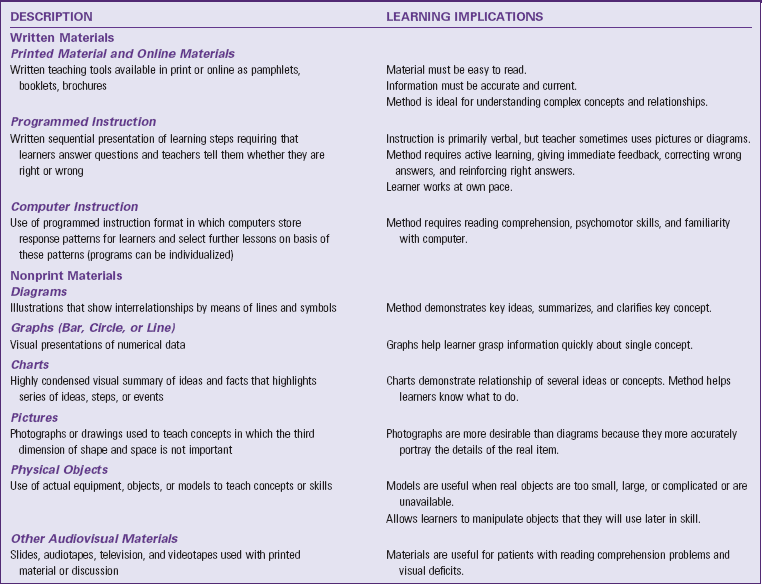

Using Teaching Tools: Many teaching tools are available for patient education. Selection of the right tool depends on the instructional method, the patient’s learning needs, and his or her ability to learn (Table 25-3). For example, a printed pamphlet is not the best tool to use for a patient with poor reading comprehension, but an audiotape is a good choice for a patient with visual impairment.

Special Needs of Children and Older Adults: Children, adults, and older adults learn differently. You adapt teaching strategies to each learner. Children pass through several developmental stages (see Unit 2). In each developmental stage children acquire new cognitive and psychomotor abilities that respond to different types of teaching methods (Fig. 25-3). Incorporate parental input in planning health education for children.

FIG. 25-3 The preschool child learns not to be afraid of medical equipment by being allowed to handle the stethoscope and imitating its use.

Older adults experience numerous physical and psychological changes as they age (see Chapter 14). These changes not only increase their educational needs but also create barriers to learning unless adjustments are made in nursing interventions. Sensory changes such as visual and hearing changes require adaptation of teaching methods to enhance functioning. Older adults learn and remember effectively if the nurse paces the learning properly and if the material is relevant to the learner’s needs and abilities. Although many older adults have slower cognitive function and reduced short-term memory, you facilitate learning in several ways to support behaviors that maximize the individual’s capacity for self-care (Box 25-8).