Behavioral-Environmental

The Individual in the Community

Community nutrition is an evolving area of practice with the broad focus of serving the population at large. Although this practice area encompasses the goals of public health, in the United States the current model has been shaped and expanded by prevention and wellness initiatives that evolved in the 1960s. Because the thrust of community nutrition is to be both proactive and responsive to the needs of the community, current emphasis areas include disaster and pandemic control, food and water safety, and controlling environmental risk factors related to obesity.

Historically public health was defined as “the science and art of preventing disease, prolonging life, and promoting health and efficiency through organized community effort” (Winslow, 1920). The public health approach, also known as a population-based or epidemiologic approach, differs from the clinical or patient care model generally seen in hospitals and other clinical settings. In the public health model the client is the community, a geopolitical entity. The focus of the traditional public health approach is primary prevention with health promotion, as opposed to secondary prevention with the goal of risk reduction, or tertiary prevention with rehabilitation efforts. Changes in the health care system, technology, and attitudes of the nutrition consumer have influenced the expanding responsibilities of community nutrition providers.

In 1988, the Institute of Medicine published a landmark report that promoted the concept that the scope of community nutrition is a work in progress. This report defined a mission and delineated roles and responsibilities for practicing community nutrition that are still the basis for community nutrition practice today. The scope of community-based nutrition encompasses efforts to prevent disease and promote positive health and nutritional status for individuals and groups in settings where they live and work. The focus is on well-being and building potential for the best possible quality of life. “Well-being” goes beyond the usual constraints of physical and mental health and includes other factors that affect the quality of life within the community. Community members need a safe environment and adequate housing, food, income, employment, and education. The mission of community nutrition is to promote the conditions in which people can be healthy.

Programming and services can be for any segment of the population. The program or service should reflect the diversity of the designated community, such as politics, geography, culture, ethnicity, ages, genders, socioeconomic issues, and overall health status. Along with primary prevention, community nutrition provides links to programs and services with goals of disease risk reduction and rehabilitation.

In the traditional model, funding sources for public health efforts were monies allocated from official sources (government) at the local, state, or federal level. Currently nutrition programs and services are funded alone or in partnership with a broad range of sources, including public (government), private, and voluntary health sectors. As public source funding has declined, the need for private funding has become more crucial. The potential size and diversity of a designated “community” makes collaboration critical. A single agency may be unable to fund or deliver the full range of services. In addition, it is likely that the funding will be services or product (in-kind) rather than cash. Creative funding and management skills are crucial for a community practitioner.

Nutrition Practice In The Community

Nutrition professionals recognize that successful delivery of food and nutrition services involves actively engaging people in their own community. The pool of nutrition professionals delivering medical nutrition therapy (MNT) and nutrition education in community-based or public health facilities continues to expand. In addition, the objectives of Healthy People 2020 offer a common framework of measurable public health outcomes that can be used to assess the overall health of a community. Although the settings may vary, there are three core functions in community nutrition practice.

The three “core” functions of public health are community assessment, policy development, and public health assurance. These areas are also the components of community nutrition practice, especially community needs assessment as it relates to nutrition. The findings of these needs assessments shape policy development and protect the nutritional health of the public.

Although there is shared responsibility for completion of the core functions of public health, official state health agencies have primary responsibility for this task. Under this model, state public health agencies, community organizations, and leaders have responsibility for assessing the capacity of their state to perform the essential functions and to attain or monitor the goals and objectives of Healthy People 2020. Local health agencies are charged with protecting the health of their population groups by ensuring that effective service delivery systems are in place. The federal government can support the development and dissemination of public health knowledge and provide funding. See Box 10-1 for a list of various government agencies.

Typical settings for community nutrition include public health agencies (state and local) and the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women Infants and Children (WIC), a federal program that allocates funds to states for specific foods, health care referrals, and nutrition education for low-income, nutritionally at-risk pregnant, breastfeeding, and non-breastfeeding postpartum women, infants and children up to age five. The expansion of community-based practice beyond the scope of traditional public health has opened new employment opportunities for nutrition professionals.

Nutrition professionals often serve as consultants or may establish community-based private practices. Nutrition services also occur in programs for senior adults, community health centers, early intervention programs, Head Start (a federal program for low-income preschool children and their families), health maintenance organizations, food pantries and shelters, physicians’ offices, and schools. Effective practice in the community requires a nutrition professional who understands the effect of economic, social, and political issues on health. Because many community-based efforts are funded or guided by legislation and the resulting regulations and policies, community practice requires an understanding of the legislative process and an ability to translate policies into action. In addition, community practice requires a working knowledge of funding sources and resources at the federal, state, regional, and local level.

Needs Assessment For Community-Based Nutrition Services

Nutrition services should be organized to meet the needs of a “community.” Once that community has been defined, a community needs assessment is developed to shape the planning, implementation, and evaluation of nutrition services. An assessment is a current snapshot of the community and is used to identify the health risks or areas of greatest concern to community well-being. To be effective, the needs assessment must be a dynamic document that is responsive to changes in the community. A plan is only as good as the research used to shape the decisions, so a mechanism for ongoing review and revision should be built into the planning.

A needs assessment is based on objective data, including demographic information and health statistics. Information should represent the community’s diversity and be segmented by such factors as age, gender, socioeconomic status, disability, and ethnicity. Examples of information to be gathered include current morbidity and mortality statistics, number of low-birth-weight infants, deaths attributed to chronic diseases with a link to nutrition, and health-risk indicators such as incidence of smoking or obesity. Healthy People 2020 outlines the leading health indicators that can be used to create target objectives. Subjective information such as input from community members and leaders and health and nutrition professionals can be useful in supporting the objective data or in emphasizing questions or concerns. The process mirrors what the business world knows as market research.

Accessible community resources and services should also be catalogued. Environmental, policy, and societal changes have contributed to the rapid rise in obesity over the past few decades; walkable neighborhoods, good access to recreation facilities, and ready access to healthy foods are important measures to assess (Sallis and Glanz, 2009). In nutrition planning the goal is to determine who and what resources are available to community members when they need food- or nutrition-related products or services. For example, what services are available for nutrition therapy, nutrition and food education, and child care or homemaker skills training? Are there safe areas for exercise or recreation? Is there access to transportation? Is there compliance with disability legislation? Are mechanisms in place for emergencies that might affect access to adequate and safe food and water?

At first glance some of the data gathered in this process may not appear to relate directly to nutrition, but an experienced community nutritionist or a community-based advisory group with public health professionals can help connect this information to nutrition- and diet-related issues. Often the nutritional problems identified in a review of nutrition indicators are associated with dietary inadequacies, excesses, or imbalances that can be triggers for disease risk. Examples of trigger areas are presence of risk factors for cardiovascular disease; diabetes and stroke, including elevated blood cholesterol and lipids, inactivity, smoking, elevated blood glucose, high body mass index (BMI), and elevated blood pressure; risk factors for osteoporosis; evidence of eating disorders; high levels of teenage pregnancy; and evidence of hunger and food insecurity. Careful attention should be paid to the special needs of adults and children with disabilities or other lifestyle-limiting conditions. Access to safe and adequate amounts of food and water can be interrupted by something as simple as a power outage or as complex as a disaster. Once evaluated, the information is used to propose needed services, including MNT as discussed in other chapters, as part of the strategy for improving the overall health of the community.

Sources for Assessment Information

It is critical that community practitioners know how to locate relevant resources and evaluate the information for validity and reliability. Knowing the background and intent of any data source and identifying the limitations and the dates when the information was collected are critical points to consider when selecting and using such sources. Census information is a starting point for beginning a needs assessment. Morbidity and mortality and other health data collected by state and local public health agencies, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) are useful. Federal agencies and their state program administration counterparts are data sources; these agencies include the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (USDHHS), U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), and the Administration on Aging. Local providers such as community hospitals, WIC and child care agencies, health centers, and universities with a public health or nutrition department are additional sources of information. Volunteer organizations such as the March of Dimes, the American Heart Association (AHA), the American Diabetes Association, and the American Cancer Society (ACS) maintain population statistics. Health insurers are a source for current information related to health care consumers and geographic area.

National Nutrition Surveys

Nutrition and health surveys at the federal and state level provide information on the dietary status of a population, the nutritional adequacy of the food supply, the economics of food consumption, and the effects of food assistance and regulatory programs. Public guidelines for food selection are usually based on survey data. The data are also used in policy setting; program development; and funding at the national, state, and local levels. Until the late 1960s, the USDA was the primary source of food and nutrient consumption data. Although much of the data collection is still at the federal level, other agencies and states are now generating information that provides comprehensive information on the health and nutrition of the public.

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) provides a framework for describing the health status of the nation. Sampling the noninstitutionalized population, the initial study began in the early 1960s, with subsequent studies on a periodic basis from 1971 to 1994. NHANES has been collected on a continuous basis since 1999. The process includes interviewing approximately 6000 individuals each year in their homes and following up with approximately 5000 individuals with a complete health examination. Since its inception, each successive NHANES has included changes or additions that make the survey more responsive as a measurement of the health status of the population. NHANES I to III included medical history, physical measurements, biochemical evaluation, physical signs and symptoms, and diet information using food frequency questionnaires and a 24-hour recall. Design changes added special population studies to increase information on under-represented groups. NHANES III (1988-1994) included a large proportion of persons age 65 years and older. This information enhanced understanding of the growing and changing population of senior adults. Currently, reports are released in 2-year cycles. Sampling methodology is planned to over-sample high-risk groups not previously covered adequately (low income, those older than the age of 60, blacks, and Hispanic Americans).

Continuing Survey of Food Intake of Individuals: Diet and Health Knowledge Survey

The Continuing Survey of Food Intake of Individuals (CSFII) was a nationwide dietary survey instituted in 1985 by the USDA. In 1990 CSFII became part of the USDA National Nutrition Monitoring System. Information from previous surveys is available from the 1980s and 1990s. The Diet and Health Knowledge Survey (DHKS), a telephone follow-up to CFSII, began in 1989. The DHKS was designed as a personal interview questionnaire that allowed individual attitudes and knowledge about healthy eating to be linked with reported food choices and nutrient intakes. Early studies focused on dietary history and a 24-hour recall of adult men and women ages 19 to 50. The 1989 and 1994 surveys questioned men, women, and children of all ages and included a 24-hour recall (personal interview) and a 2-day food diary. Household data for these studies were determined by calculating the nutrient content of foods reported to be used in the home during the survey. These results were compared with nutrition recommendations for persons matching in age and gender. The information derived from the CSFII and DHKS is still useful for decision makers and researchers in monitoring the nutritional adequacy of American diets, measuring the effect of food fortification on nutrient intakes, tracking trends, and developing dietary guidance and related programs. In 2002, both surveys merged with NHANES to become the National Food and Nutrition Survey (NFNS) or What We Eat in America.

National Food and Nutrition Survey: What We Eat in America

The integrated survey, What We Eat in America, is collected as part of NHANES. Food-intake data are linked to health status from other NHANES components, allowing for exploration of relationships between dietary indicators and health status. The USDHHS is responsible for sample design and data, whereas the USDA is responsible for the survey’s collection and maintenance of the dietary data. Data are released at 2-year intervals and are accessible from the NHANES website (U.S. Department of Agriculture [USDA] and Agricultural Research Service, 2009).

National Nutrition Monitoring and Related Research Act

In 1990 Congress passed Public Law 101-445, the National Nutrition Monitoring and Related Research (NNMRR) Act. The purpose of this law is to provide organization, consistency, and unification to the survey methods that monitor the food habits and nutrition of the U.S. population, and to coordinate the efforts of the 22 federal agencies that implement or review nutrition services or surveys. Data obtained through NNMRR are used to direct research activities, develop programs and services, and make policy decisions regarding nutrition programs such as food labeling, food and nutrition assistance, food safety, and nutrition education. Reports of the various activities are issued approximately every 5 years and provide information on trends, knowledge, attitudes and behavior, food composition, and food supply determinants. They are available from the National Agricultural Library database.

National Nutrient Databank

The National Nutrient Databank, maintained by the USDA, is the United States’ primary resource of information from private industry, academic institutions, and government laboratories on the nutrient content of foods. Historically the information was published as the series Agriculture Handbook 8. Currently, the databases are available to the public on tapes and on the Internet. The bank is updated frequently and includes supplemental sources, international databases, and links to other sites. This databank is a standard and updated source of nutrient information for commercial references and data systems. When using sources other than the USDA site, it is important to check the sources and the dates of the updates for evidence that these sources are reliable and current.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

The CDC is a component of the USDHHS. It monitors the nation’s health, detects and investigates health problems, and conducts research to enhance prevention. The CDC is also a source of information on health for international travel. Housed at CDC is the NCHS, the lead agency for NHANES, morbidity and mortality, BMI, and other health-related measures. Public health threats, such as the H1N1 virus, are also monitored by CDC.

National Nutrition Guidelines And Goals

Policy development describes the process by which society makes decisions about problems, chooses goals, and prepares the means to reach them. Such policies may include health priorities and dietary guidance.

Early dietary guidance had a specific disease approach. The 1982 National Cancer Institute (NCI) landmark report, Diet, Nutrition and Cancer, evolved into Dietary Guidelines for Cancer Prevention. These were updated and broadened, combining recommendations on energy balance, nutrition, and physical activity in 2004. The ACS and the American Institute for Cancer Research (AICR) are excellent resources along with materials from the NCI. Another federal agency, the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute provided three sets of landmark guidelines for identifying and treating lipid disorders between 1987 and 2010.

The AHA guidelines focused on persons at risk for hypertension and coronary artery disease; they were written in 2000 and revised in 2006 to include environmental influences on food choices. Another consumer-friendly, single health guideline was released in 1991 as a part of the “5-A-Day for Better Health” program sponsored by the NCI, the National Institutes of Health, and the Produce for Better Health Foundation. This guidance was built around fruits and vegetables being naturally low in fat and good sources of fiber, several vitamins and minerals, and phytonutrients. In keeping with evidence-based messages, the quantity was expanded to five to nine servings of fruits and vegetables a day to promote good health under the name of “Fruits and Veggies: More Matters” (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [USDHHS], 2009).

Dietary Guidelines for Americans

Senator George McGovern and the Senate Select Committee on Nutrition and Human Needs presented the first Dietary Goals for the United States in 1977. In 1980 the goals were modified and issued jointly by the USDHHS and the USDA as the Dietary Guidelines for Americans (DGA). The original guidelines were a response to an increasing national concern for the rise in overweight, obesity, and chronic diseases such as diabetes, coronary artery disease, hypertension, and certain cancers. The approach continues to be one of health promotion and disease prevention, with special attention paid to specific population groups.

The release of the DGA led the way for a synchronized message to the community. The common theme has been a focus on a diet lower in sodium and saturated fat, with emphasis on foods that are sources of fiber, complex carbohydrates, and lean or plant-based proteins. The message is based on food choices for optimal health using appropriate portion sizes and calorie choices related to a person’s physiologic needs. Exercise, activity, and food safety guidance are standard parts of this dietary guidance. Fortunately, the current DGA are evidence-based rather than just “good advice.” The expert committee report provides scientific documentation that is widely used in health practice. The DGA have become a central theme in community nutrition assessment, program planning, and evaluation; they are incorporated into programs such as School Lunch and Congregate Meals. Updated every 5 years, the DGA have recently undergone revision in 2010.

Food Guides

In 1916 the USDA initiated the idea of food grouping in the pamphlet, Food for Young Children. Food grouping systems have changed in shape (wheels, boxes, and pyramids) and numbers of groupings (four, five, and seven groups), but the intent remains consistent: to present an easy guide for healthful eating. In 2005, an Internet-based tool called MyPyramid.gov: Steps to a Healthier You was released. In 2011, MyPyramid.gov was replaced with chooseMyPlate.gov along with a version for children called chooseMyPlate.gov/kids. These food guidance systems focus on health promotion and disease prevention, and are updated whenever DGA guidance changes.

Healthy People and the Surgeon General’s Report on Nutrition and Health

The 1979 report of the Surgeon General, Promoting Health/Preventing Disease: Objectives for the Nation, outlined the prevention agenda for the nation with a series of health objectives to be accomplished by 1990. In 1988, The Surgeon General’s Report on Nutrition and Health further stimulated health promotion and disease prevention by highlighting information on dietary practices and health status. Along with specific health recommendations, documentation of the scientific basis was provided. Because the focus included implications for the individual as well as for future public health policy decisions, this report remains a useful reference and tool. Healthy People 2000: National Health Promotion and Disease Prevention Objectives and Healthy People 2010 were the next generations of these landmark public health efforts. Both reports outlined the progress made on previous objectives and set new objectives for the next decade.

During the evaluation phase for setting the 2010 objectives, it was determined that the United States made progress in reducing the number of deaths from cardiovascular disease, stroke, and certain cancers. Dietary evaluation indicated a slight decrease in total dietary fat intake. However, during the previous decade there has been an increase in the number of persons who are overweight or obese, a risk factor for cardiovascular disease, stroke, and other leading chronic diseases and causes of death.

Objectives for Healthy People 2020 have specific goals that address nutrition and weight, heart disease and stroke, diabetes, oral health, cancer, and health for seniors. These goals are important for consumers and health care providers alike. The website for Healthy People 2020 offers an opportunity to monitor the progress on past objectives as well as on the shaping of future health initiatives.

National School Lunch Program

The National School Lunch Program (NSLP) is a federal assistance program that provides free or reduced-cost meals for low-income students in public, nonprofit private and residential institutions. It is administered at a state level through the education agencies that generally employ dietitians. In 1998 the program was expanded to include after-school snacks in schools with after-hours care. Currently the guidelines for calories, percent of calories from fat, percent of saturated fat, and the amount of protein and key vitamins and minerals must meet the DGA.

A requirement for wellness policies in schools that participate in the NSLP is in place (Edelstein et al., 2010). However, the School Nutrition Dietary Assessment Study, a nationally representative study fielded during school year 2004-2005 to evaluate nutritional quality of children’s diets, identified that 80% of children had excessive intakes of saturated fat and 92% had excessive intakes of sodium (Clark and Fox, 2009). An increase in whole grains, fresh fruits, and a greater variety of vegetables is needed (Condon et al., 2009). The state of Texas made changes to their school lunches by restricting portion sizes of high-fat and high-sugar snacks and sweetened beverages, fat content of foods, and high-fat vegetables like french fries; this led to a desired reduction in energy density (Mendoza et al., 2010). For current information and updates to these programs, check the USDA website.

The Recommended Dietary Allowances and Dietary Reference Intakes

The recommended dietary allowances (RDAs) were developed in 1943 by the Food and Nutrition Board of the National Research Council of the National Academy of Sciences. The first tables were developed at a time when the U.S. population was recovering from a major economic depression and World War II; nutrient deficiencies were a concern. The intent was to develop intake guidelines that would promote optimal health and lower the risk of nutrient deficiencies. As the food supply and the nutrition needs of the population changed, the intent of the RDAs was adapted to prevention of nutrition-related disease. Until 1989 the RDAs were revised approximately every 10 years.

The RDAs have always reflected gender, age, and life-phase differences. There have been additions of nutrients and revisions of the age-groups. However, recent revisions are a major departure from the single list some professionals still view as the RDAs. Beginning in 1998 an umbrella of nutrient guidelines known as the dietary reference intakes (DRIs) was introduced. Included in the DRIs are RDAs, as well as new designations, including guidance on safe upper limits of certain nutrients. As a group the DRIs are evaluated and revised at intervals, making these tools reflective of current research and population base needs (see Chapter 12).

Food Assistance And Nutrition Programs

Public health assurance addresses the implementation of legislative mandates, maintenance of statutory responsibilities, support of crucial services, regulation of services and products provided in both the public and private sector, and maintenance of accountability. This includes providing for food security, which translates into having access to an adequate amount of healthful and safe foods.

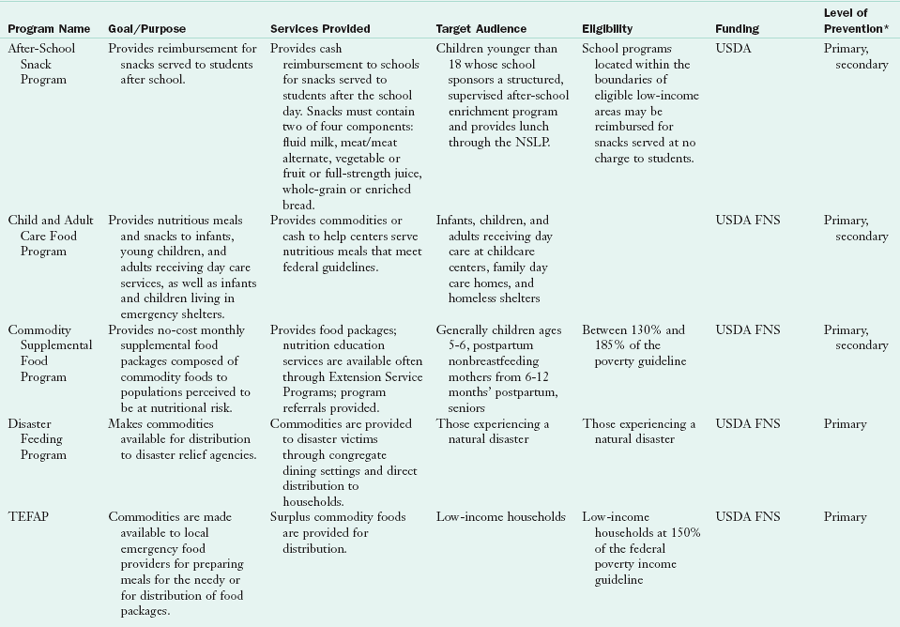

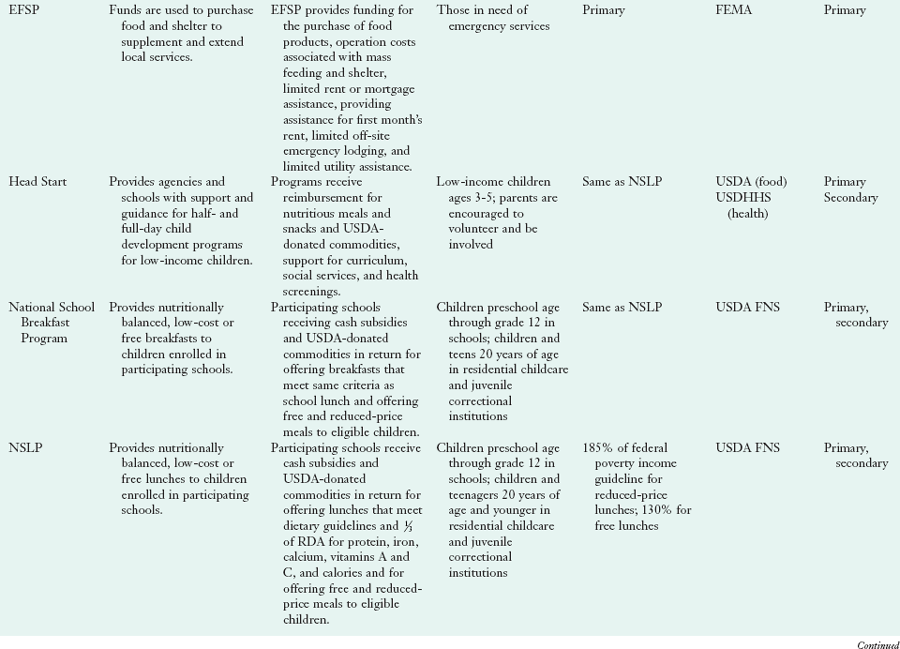

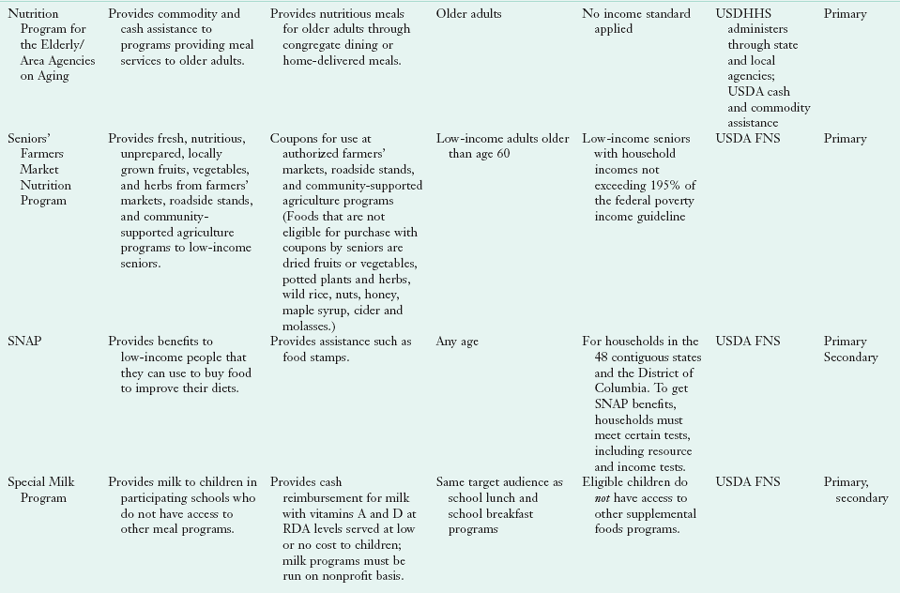

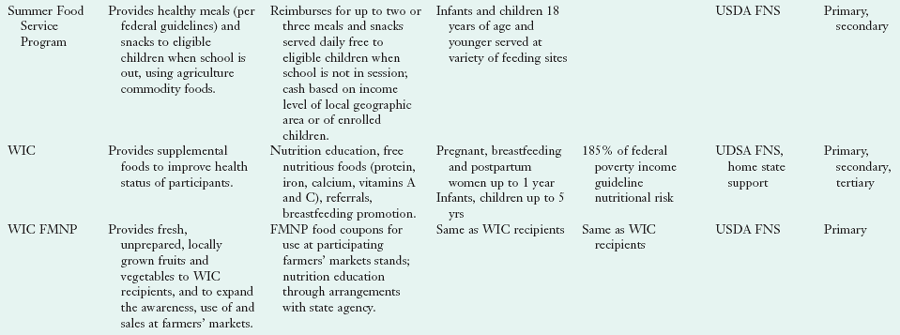

In the area of food security, or access by individuals to a readily available supply of nutritionally adequate and safe foods, programs such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) for food stamps, food pantries, and home-delivered meals, child nutrition programs, supermarkets, and other food sources should be available and used. For example, research on neighborhood food access indicates that low availability of healthy food in area stores is associated with low-quality diets of area residents (Rose et al., 2010). See Table 10-1 for a list of food and nutrition assistance programs.

TABLE 10-1

U.S. Food Assistance and Nutrition Programs

EFSP, Emergency Food and Shelter Program; FEMA, Federal Emergency Management Agency; FMNP, Farmers Market Nutrition Program; FNS, Food and Nutrition Service; NSLP, National School Lunch Program; RDA, recommended daily allowance; SNAP, Special Nutrition Assistance Program; USDA, U.S. Department of Agriculture; USDHHS, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; WIC, Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children.

*Level of prevention rationale: Programs that provide food only are regarded as primary; programs that provide food, nutrients at a mandated level of recommended dietary allowances or an educational component are regarded as secondary; and programs that used health screening measures on enrollment were regarded as tertiary.

Foodborne Illness

Each year there are an estimated 76 million cases of foodborne illness in the United States. The majority of foodborne illness outbreaks reported to the CDC result from bacteria, followed by viral outbreaks, chemical causes, and parasitic causes. Segments of the population are particularly susceptible to foodborne illnesses; vulnerable individuals are more likely to become ill and experience complications. Some of the nutritional complications associated with foodborne illness include reduced appetite and reduced nutrient absorption from the gut.

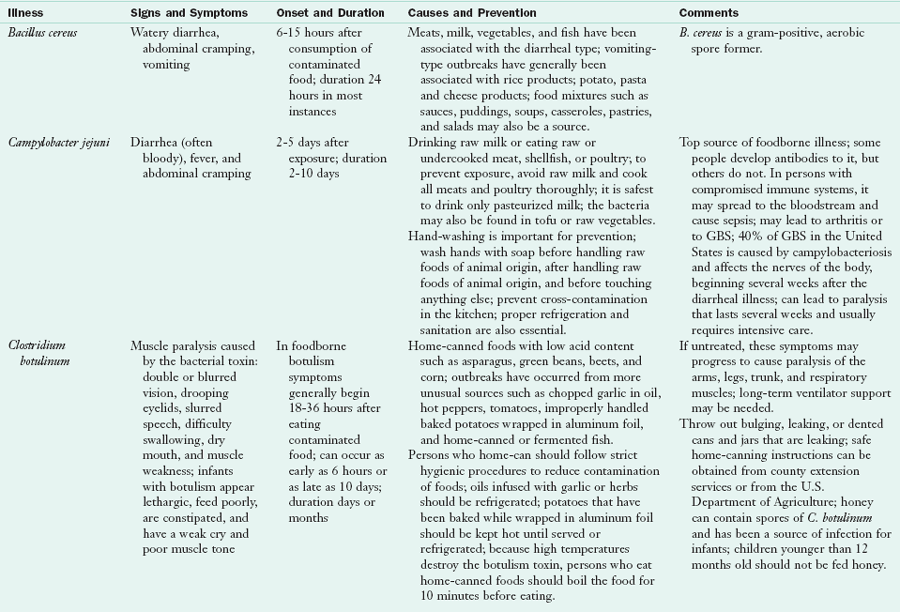

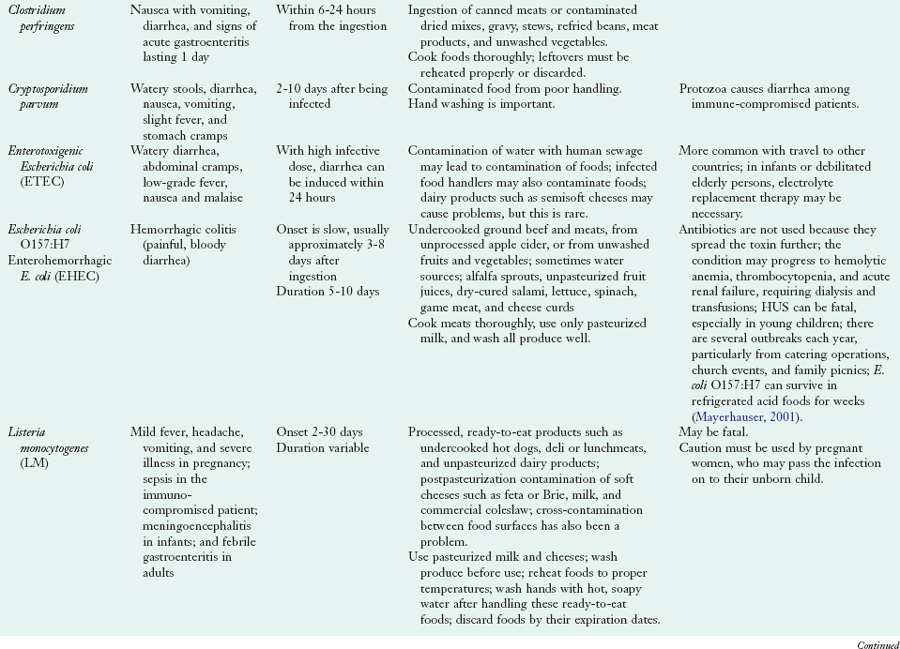

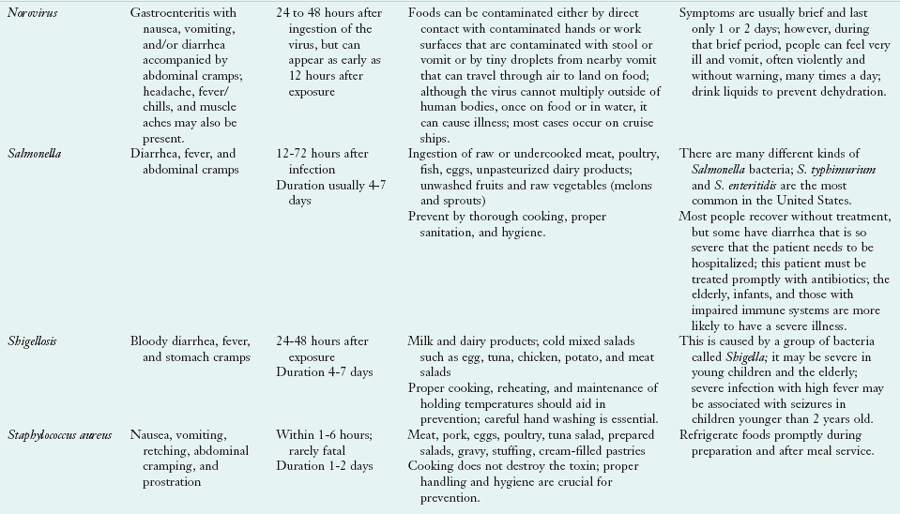

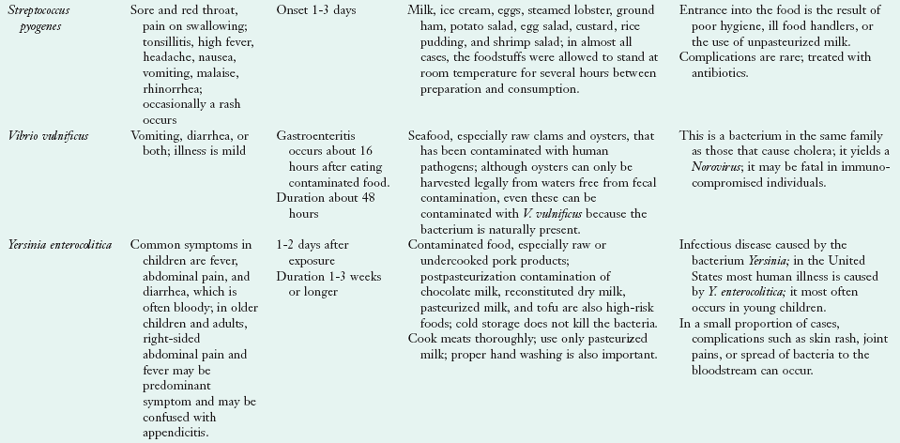

The 2000 edition of the DGA was the first to include food safety, important for linking the safety of the food and water supply with health promotion and disease prevention. This acknowledges the potential for foodborne illness to cause both acute illness and long-term chronic complications. Since 2000 all revisions of the DGA have made food safety a priority. Persons at increased risk for foodborne illnesses include young children; pregnant women; older adults; persons who are immunocompromised because of human immunodeficiency virus or acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, steroid use, chemotherapy, diabetes mellitus, or cancer; alcoholics; persons with liver disease, decreased stomach acidity, autoimmune disorders, or malnutrition; persons who take antibiotics; and persons living in institutionalized settings. Costs associated with foodborne illness include those related to investigation of foodborne outbreaks and treatment of victims, employer costs related to lost productivity, and food industry losses related to lower sales and lower stock prices (American Dietetic Association, 2009). Table 10-2 describes common foodborne illnesses and their signs and symptoms, timing of onset, duration, causes, and prevention.

TABLE 10-2

GBS, Guillian-Barré Syndrome; HUS, hemolytic uremic syndrome.

Adapted with permission from Escott-Stump S: Nutrition and diagnosis-related care, ed 7, Baltimore, 2011, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Other sources: http://www.cdc.gov/health/diseases; http://www.cfsan.fda.gov/~mow/intro.html, accessed April 23, 2010.

All food groups have ingredients associated with food safety concerns. There are concerns about microbial contamination of fruits and vegetables especially those imported from other countries. An increased incidence of foodborne illness occurs with new methods of food production or distribution, and with increased reliance on commercial food sources (ADA, 2009). Improperly cooked meats can harbor organisms that trigger a foodborne illness. Even properly cooked meats have the potential to cause foodborne illness if the food handler allows raw meat juices to contaminate other foods during preparation. Sources of a foodborne illness outbreak vary, depending on such factors as the type of organism involved, the point of contamination and the duration and temperature of food during holding.

Targeted food safety public education campaigns are important. However, the model for food safety has expanded beyond the individual consumer and now includes government, the food industry, and the general public. Several government agencies provide information through websites with links to the CDC, the USDA Food Safety and Inspection Service (FSIS), the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). A leading industry program, ServSafe®, provides food safety and training certification and was developed and administered by the National Restaurant Association. Because our food supply comes from a global market, food safety concerns are worldwide. The 2009 Country of Origin Labeling (COOL) legislation requires that retailers provide customers with the source of foods such as meats, fish, shellfish, fresh and frozen fruits and vegetables, and certain nuts and herbs. The USDA Agricultural Marketing Service has responsibility for COOL implementation. Future practice must include awareness of global food safety issues (see Clinical Insight: Global Food Safety).

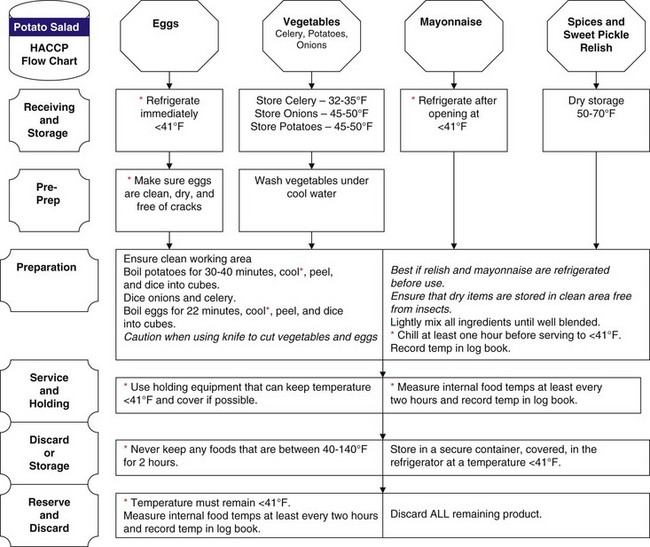

Hazard Analysis Critical Control Points

An integral strategy to reduce foodborne illness is risk assessment and management. Risk assessment entails hazard identification, characterization, and exposure. Risk management covers risk evaluation, option assessment and implementation, monitoring and review of progress. One formal program, organized in 1996, is the Hazard Analysis Critical Control Points (HACCP), a systematic approach to the identification, evaluation, and control of food safety hazards. HACCP involves identifying any biologic, chemical, or physical agent that is likely to cause illness or injury in the absence of its control as it pertains to food production. It also involves identifying points at which control can be applied, thus preventing or eliminating the food safety hazard or reducing it to an acceptable level. Restaurants and health care facilities are obligated to use HACCP procedures in their food handling practices.

There is an increased risk to health care professionals with direct patient contact, as well as those involved in community education. Those who serve populations at the greatest risk for foodborne illness have a special need to be involved in the network of food safety education and to communicate this information to their clients. Adoption of the HACCP regulations, food quality assurance programs, handling of fresh produce guidelines, technologic advances designed to reduce contamination, increased food supply regulations, and a greater emphasis on food safety education has contributed to a substantial decline in foodborne illness. Figure 10-1 shows a graphic used to explain HACCP to those who are cooking meals in large quantity.

Food And Water Safety

Although individual educational efforts are effective in raising awareness of food safety issues, food and water safety must be examined on a national, systems-based level (ADA, 2009). Several federal health initiatives include objectives relating to food and water safety, pesticide and allergen exposure, food-handling practices, reducing disease incidence associated with water, and reducing food- and water-related exposure to environmental pollutants. Related agencies can be found in Table 10-3.

TABLE 10-3

Food and Water Safety Resources

| American Egg Board | http://www.aeb.org |

| American Dietetic Association | http://www.eatright.org/ |

| American Meat Institute | http://www.meatami.com |

| CFSAN | http://www.cfsan.fda.gov |

| CFSCAN—Food and Water Safety—Disasters | http://www.cfsan.fda.gov/~dms/fsdisas.html |

| CDC | http://www.cdc.gov |

| CDC Disaster | http://www.bt.cdc.gov/disasters/ |

| FEMA | http://www.fema.gov |

| Food Chemical News | http://www.foodchemicalnews.com |

| Food Marketing Institute | http://www.fmi.org |

| Food Marketing Institute—Bird Flu | http://www.fmi.org/foodsafety/avian_flubrochure.htm |

| FoodNet | http://www.cdc.gov/foodnet/ |

| Food Preservation and Safety, Iowa State University | http://www.foodpres.com |

| Foundation for Food Irradiation Education | http://www.food-irradiation.com |

| Grocery Manufacturers of America | http://www.gmabrands.org |

| International Food Information Council | http://ific.org/food |

| National Broiler Council | http://www.eatchicken.com |

| National Cattleman’s Beef Association | http://www.beef.org/ |

| National Institutes of Health | http://www.nih.gov |

| National Food Safety Database | http://www.foodsafety.gov |

| National Restaurant Association Educational Foundation | http://www.edfound.org |

| The Partnership for Food Safety Education | http://www.fightbac.org |

| Produce Marketing Association | http://www.pma.com |

| PulseNet | http://www.cdc.gov/pulsenet/whatis.html |

| U.S. Department of Agriculture | http://www.usda.gov |

| U.S. Department of Agriculture Food Safety and Inspection Service | http://www.fsis.usda.gov |

| U.S. Department of Education | http://www.ed.gov |

| U.S. Department of Health and Human Services | http://os.dhhs.gov |

| U.S. EPA—Office of Ground and Drinking Water | http://www.epa.gov/safewater |

| U.S. EPA Seafood Safety | http://www.epa.gov/ost/fish |

| U.S. Food and Drug Administration | http://www.fda.gov |

| U.S. Poultry and Egg Association | http://www.poultryegg.org |

NOTE: Specific websites often change because of updating. Go to the home website and use a search to find the desired resources.

CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; CFSAN, Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition; EPA, Environmental Protection Agency; FEMA, Federal Emergency Management Agency.

Contamination

Controls and precautions in the area of limiting potential contaminants in the water supply are of continuing importance. Water contamination with arsenic, lead, pesticides, mercury, chlorine, herbicides, and Escherichia coli has been repeatedly highlighted by the media. It has been estimated that many public water systems, built using early twentieth-century technology, will need to invest more than $138 billion during the next 20 years to ensure continued safe drinking water (ADA, 2009). The effect on the potential safety of foods that have contact with these contaminants is an ongoing issue being monitored by advocacy and professional groups and governmental agencies.

Of interest to many is the issue of the potential hazards of ingestion of seafood that has been in contact with methyl mercury present naturally in the environment and released into the air from industrial pollution. Mercury has accumulated in bodies of water (i.e., streams, rivers, lakes, and oceans) and in the flesh of seafood in these waters (U.S. Food and Drug Administration and Environmental Protection Agency, 2009). The body of knowledge on issues such as this is constantly being updated, and there are now recommendations to restrict the consumption of certain fish such as shark, mackerel, tilefish, tuna, and swordfish by pregnant women (Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition, 2009). (See Chapter 16 for further discussion.) Other contaminants in fish, polychlorinated biphenyls, and dioxin are also of concern (Mozaffarian and Rimm, 2006).

There are precautions in place at the federal, state, and local levels that need to be addressed by dietetics professionals whose roles include advocacy, communication, and education. Both members of the public and local health officials must understand the risks and the importance of carrying out measures for food and water safety and protection. Both the EPA and the Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition (CFSAN) provide ongoing monitoring and guidance. In addition, food and water safety and foodborne illness issues are monitored by state and local health departments.

Organic Foods and Pesticide Use

The use of pesticides and contaminants from the water supply affect produce quality. The debate continues about whether or not organic foods are worth the extra cost. However, the beneficial effects of organic farming also need to be considered. Most experts agree that fruit such as apples may be healthier if chosen in the organic aisle. Otherwise, fruits with a thick skin, such as banana, are acceptable in either form. See Clinical Insight: Is Organic Produce Healthier?

Bioterrorism and Food-Water Safety

Bioterrorism is the deliberate use of microorganisms or toxins from living organisms to induce death or disease. Threats to the nation’s food and water supplies have made food biosecurity, or precautions to minimize risk, an issue when addressing preparedness planning. The CDC has identified seven foodborne pathogens as having the potential to be used by bioterrorists to attack the food supply: tularemia, brucellosis, Clostridium botulinum toxin, epsilon toxin of Clostridium perfringens, Salmonella, E. coli, and Shigella. These pathogens, along with potential water contaminants, such as mycobacteria, Legionella, Giardia, viruses, arsenic, lead, copper, methyl butyl ether, uranium, and radon, are the targets of federal systems put in place to monitor the safety of the food and water supply. Current surveillance systems are designed to detect foodborne illness outbreaks resulting from food spoilage, poor food handling practices, or other unintentional sources, but they were not designed to identify an intentional attack.

Consequences of a compromised food and water supply would be physical, psychological, political, and economic. Compromise could occur with food being the primary agent such as a vector to deliver a biologic or chemical weapon or with food being a secondary target, leaving an inadequate food supply to feed a region or the nation. Intentional use of a foodborne pathogen as the primary agent might be mistaken as a routine outbreak of foodborne illness. Distinguishing normal illness fluctuation from an intentional attack depends on having in place a system for preparedness planning, rapid communication, and central analysis.

Experience with the series of hurricanes in 2005 emphasizes the need to provide access to a safe food and water supply after emergencies and disasters. Access to food and water may be limited, which, in the case of bioterrorism, results in social disruption and self-imposed quarantine. These situations require a response different from the traditional approach to disaster relief, during which it is assumed that hungry people will seek assistance and have confidence in the safety of the food that is offered (Bruemmer, 2003). In the event of a disaster, dietetics professionals can play a key role by being aware of their environment, knowing available community and state food and nutrition resources, and participating in coordination and delivery of relief to victims of the disaster.

Disaster Planning

Dietetics and health professionals working in food service are expected to plan for the distribution of safe food and water in any emergency situation. This may include choosing food preparation and distribution sites, establishing temporary kitchens, preparing foods with limited resources, and keeping prepared food safe to eat through HACCP procedures (Puckett and Norton, 2009). To prepare for such planning, several federal agencies share the responsibility for food and water safety.

Planning, surveillance, detection, response, and recovery are the key components of public health disaster preparedness. The key agencies are the USDA, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), the CDC, and the FDA. In conjunction with DHS, USDA operates Protection of the Food Supply and Agricultural Production (PFSAP). PFSAP handles issues related to food production, processing, storage, and distribution. It addresses threats against the agricultural sector and border surveillance. PFSAP conducts food safety activities concerning meat, poultry, and egg inspection and provides laboratory support, research, and education on outbreaks of foodborne illness.

Ready.gov (www.ready.gov) is an education tool informing the public on how to prepare for a national emergency, including possible terrorist attacks. In addition, the USDA FSIS operates the Food Threat Preparedness Network (PrepNet) and the Food Biosecurity Action Team (F-Bat). PrepNet ensures effective coordination of food security efforts, focusing on preventive activities to protect the food supply. F-Bat assesses potential vulnerabilities along the farm-to-table continuum, provides guidelines to industry on food security and increased plant security, strengthens FSIS’s coordination and cooperation with law enforcement agencies, and enhances security features of FSIS laboratories (Bruemmer, 2003).

CDC has three operations relating to food security and disaster planning: PulseNet, FoodNet, and the Centers for Public Health Preparedness. PulseNet is a national network of public health laboratories that performs deoxyribonucleic acid fingerprinting on foodborne bacteria, assists in detecting foodborne illness outbreaks and tracing them back to their source, and provides linkages among sporadic cases. FoodNet is the Foodborne Diseases Active Surveillance Network, which functions as the principle foodborne disease component of the CDC’s Emerging Infections Program, providing active laboratory-based surveillance. The Centers for Public Health Preparedness funds academic centers linking schools of public health with state, local, and regional bioterrorism preparedness and public health infrastructure needs (Bruemmer, 2003).

CFSAN in the FDA is concerned with regulatory issues such as seafood HACCP, safety of food and color additives, safety of foods developed through biotechnology, food labeling, dietary supplements, food industry compliance, and regulatory programs to address health risks associated with foodborne chemical and biologic contaminants. CFSAN also runs cooperative programs with state and local governments.

The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), under the DHS, provides emergency support functions after a disaster or emergency. FEMA identifies food and water needs, arranges delivery, and provides assistance with temporary housing and other emergency services. Agencies that assist FEMA include the USDA, the Department of Defense, the USDHHS, the EPA, and the General Services Administration. Major players include voluntary agencies such as the American Red Cross, the Salvation Army, and community-based agencies and organizations. Disaster management is evolving as it is tested by both manufactured and natural disasters.

http://fnic.nal.usda.gov/nal_display/index.php?info_center=4&tax_level=1&tax_subject=256

Dietary Guidelines for Americans

http://www.cnpp.usda.gov/dietaryguidelines.htm

Environmental Protection Agency (Fish)

Federal Emergency Management Agency

Hazard Analysis Critical Control Points

http://www.fda.gov/Food/FoodSafety/HazardAnalysisCriticalControlPointsHACCP/HACCPPrinciplesApplicationGuidelines/default.htm

http://www.acf.hhs.gov/programs/ohs/legislation/index.html

National Academy Press—Dietary Reference Intakes

http://www.nap.edu/topics.php?topic=380

National Center for Health Statistics

National Health and Nutrition Examination Study

http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes.htm

U.S. Department of Agriculture Farm to School Initiative

http://www.fns.usda.gov/cnd/F2S/Default.htm

U.S. Department of Agriculture Nutrient Database

http://www.ars.usda.gov/nutrientdata

U.S. Department of Agriculture Nutrition Assistance Programs

References

American Dietetic Association (ADA). Position of the American Dietetic Association: food and water safety. J Am Diet Assoc. 2009;109:1449.

American Dietetic Association. the role of registered dietitians and dietetic technicians, registered in health promotion and disease prevention programs. J Am Diet Assoc. 2006;106:1875.

American Medical Association, Report of the Council on Science and Public Health. (CSAPH). CSAPH Report 8-A-09. Sustainable Food. Resolution 2008;405:A–08. Accessed 20 June 2009 from. http://www.ama-assn.org/ama1/pub/upload/mm/443/csaph-rep8-a09.pdf

Arcury, T, et al. Pesticide urinary metabolite levels of children in Eastern North Carolina farmworker households. Environ Health Perspect. 2007;115:1254.

Aruoma, OI. The impact of food regulation on the food supply chain. Toxicology. 2006;221:119.

Benbrook, C, et al. Methodologic flaws in selecting studies and comparing nutrient concentrations led Dangour to miss the emerging forest amid the trees. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;90:1700.

Bruemmer, B. Food biosecurity. J Am Diet Assoc. 2003;103:687.

Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition (CFSAN), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration. Food. Accessed 27 December 2009 from http://www.fda.gov/food/default.htm.

Clark, MA, Fox, MK. Nutritional quality of the diets of US public school children and the role of the school meal programs. J Am Diet Assoc. 2009;109:S44.

Condon, EM, et al. School meals: types of foods offered to and consumed by children at lunch and breakfast. J Am Diet Assoc. 2009;109:67.

Dangour, AD, et al. Nutritional quality of organic foods: a systematic review. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;90:680.

Dangour, AD, et al. Reply to DL Gibbon and C Benbrook et al. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;90:1701.

Dani, C, et al. Intake of purple grape juice as a hepatoprotective agent in Wistar rats. J Med Food. 2008;11:127.

Edelstein, S, et al. Reaching out to those at highest nutritional risk. In Nutrition in public health, ed 2, Sudbury, MA: Jones and Bartlett; 2010:122. [In press.].

Electronic Code of Federal Regulations (e-CFR). Title 7: Agriculture. Part 205—National Organic Program. Accessed 4 January 2010 from http://ecfr.gpoaccess.gov/cgi/t/text/text-idx?c=ecfr&sid=49c75b1e28f8cd145546869235346e46&rgn=div5&view=text&node=7:3.1.1.9.32&idno=7.

Greene, C, et al. Emerging issues in the US organic industry, Economic Information Bulletin Number EIB-55. Washington DC: United States Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service; June 2009.

Healthy People 2000. National health promotion and disease prevention objectives. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 1990.

Healthy People 2010. National health promotion and disease prevention objectives. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2000.

Healthy People 2020. National health promotion and disease prevention objectives. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2010.

Huen, K, et al. Developmental changes in PON1 enzyme activity in young children and effects on PON1 polymorphisms. Environ Health Perspect. 2009;117:1632.

Kummeling, I, et al. Consumption of organic food and risk of atopic disease during the first 2 years of life in the Netherlands. Br J Nutr. 2008;99:598.

Lairon, D. Nutritional quality and safety of organic food: a review. Agron Sustain Dev. 2009. [doi: 10.10151/agro/2009019].

Lu, C, et al. Dietary intake and its contribution to longitudinal pesticide exposure in urban/suburban children. Environ Health Perspect. 2008;116:537.

Lu, C, et al. Organic diets significantly lower children’s dietary exposure to organophosphorus pesticides. Environ Health Perspect. 2006;114:260.

Mayerhauser, CM. Survival of enterhemorrhagic Escherichia coli 0157: H7 in retail mustard. J Food Prot. 2001;64:783.

McCullum-Gómez, C, Scott, AM. Hot topic: perspective on the benefit of organic foods. http://www.eatright.org/About/Content.aspx?id=10614, September 2009. [Accessed 2 December 2009 from].

Mendoza, JA, et al. Change in dietary energy density after implementation of the Texas Public School Nutrition Policy. J Am Diet Assoc. 2010;110:434.

Mitchell, AE, et al. Ten year comparison of the influence of organic and conventional crop management on the content of flavonoids in tomatoes. J Agric Food Chem. 2007;55:6154.

Mozaffarian, D, Rimm, EB. Fish intake, contaminants, and human health: evaluating the risks and the benefits. JAMA. 2006;296:1885.

Mukherjee, A, et al. Longitudinal microbiological survey of fresh produce grown by farmers in the upper Midwest. J Food Prot. 2006;69:1928.

National Organic Program (NOP): Organic production and handling standards, Washington, DC, United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), Agricultural Marketing Service. Accessed 25 July 2009 from http://www.ams.usda.gov/AMSv1.0/getfile?dDocName=STELDEV3004445&acct=nopgeninfo.

Niggli, U, et al, Low greenhouse gas agriculture: mitigation and adaptation potential of sustainable farming systems. Rome, Italy: Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations; 2009. Accessed 29 June 2009 from. ftp://ftp.fao.org/docrep/fao/010/ai781e/ai781e00.pdf

Olsson, ME, et al. Antioxidant levels and inhibition of cancer cell proliferation in vitro by extracts from organically and conventionally cultivated strawberries. J Agri Food Chem. 2006;54:1248.

Organic Trade Association, Organic Trade Association’s 2009 organic industry survey. Greenfield, Ma: Organic Trade Association; 2009. Accessed 1 July 2009 from. http://www.ota.com

Puckett, R, Norton, C, Are you prepared? Developing a disaster plan for your facility. ADA Times, November-December 2005. Accessed 27 December 2009 from. http://www.eatright.org

Riddle, JA. Organic food safety—regulatory requirements, College of Food, Agricultural and Natural Resource Sciences, University of Minnesota, Organic Ecology Research and Outreach Program. Accessed 30 November 2009 from www.organicecology.umn.edu.

Rose, D, et al. The importance of a multi-dimensional approach for studying the links between food access and consumption. J Nutr. 2010. [Epub ahead of print.].

Sallis, JF, Glanz, K. Physical activity and food environments: solutions to the obesity epidemic. Milbank Q. 2009;87:123.

Semenova, AV, et al, COLIWAVE: a simulation model for survival of E. coli 0157:H7 in dairy manure and manure-amended soil. Ecol Model 2009. doi:10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2009.10.028

U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA). Country of origin labeling. Washington, DC. Accessed 27 December 2009 from http://www.ams.usda.gov/nop/AMSv1.0/Cool.

U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), Agricultural Research Service (ARS): What we eat in America (WWEIA), NHANES, Overview, Beltsville, Md, USDA. Accessed 27 December 2009 from http://www.ars.usda.gov/Services/docs.htm?docid=13793.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (USDHHS) Institutes of Health. 5 a day. http://www.5aday.gov, 2005. [Accessed 27 December 2009 from].

U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Mercury and fish. http://www.epa.gov/ost/fish.

Winslow, CEA. The untilled field of public health. Mod Med. 1920;2:183.

Worldwatch Institute, Questions and answers about global warming and abrupt climate change. Washington, DC: Worldwatch Institute; 2008. Accessed 26 July 2009 from. http://www.worldwatch.org/node/3949

Ziesemer, J, Energy use in organic food systems. Natural Resources Management and Environment Department, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Rome, Italy: FAO; 2007. Accessed 3 July 2009 from. http://www.fao.org/docs/eims/upload/233069/energy-use-oa.pdf