Food and Nutrient Delivery

Planning the Diet with Cultural Competency

An appropriate diet is adequate and balanced and considers the individual’s characteristics such as age and stage of development, taste preferences, and food habits. It also reflects the availability of foods, socioeconomic conditions, cultural practices and family traditions, storage and preparation facilities, and cooking skills. An adequate and balanced diet meets all the nutritional needs of an individual for maintenance, repair, living processes, growth, and development. It includes energy and all nutrients in proper amounts and in proportion to each other. The presence or absence of one essential nutrient may affect the availability, absorption, metabolism, or dietary need for others. The recognition of nutrient interrelationships provides further support for the principle of maintaining food variety to provide the most complete diet.

Dietitians translate food, nutrition, and health information into food choices and diet patterns for groups and individuals. With increasing knowledge of how diet influences diseases that lead to premature disability and mortality among Americans, an appropriate diet helps reduce the risk of developing chronic diseases and conditions. In this era of vastly expanding scientific knowledge, food intake messages for health promotion and disease prevention change rapidly. The public often hears references to functional food ingredients, which provide more benefits than just basic nutrition.

Determining Nutrient Needs

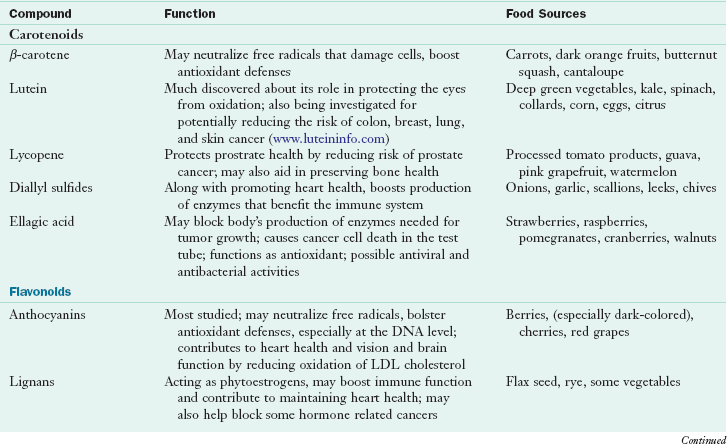

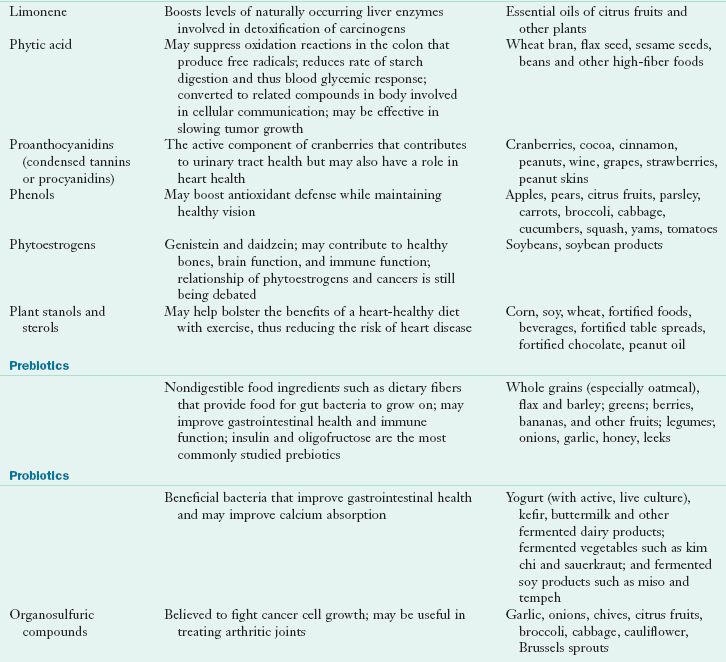

According to the Food and Nutrition Board, choosing a variety of foods should provide adequate amounts of nutrients. A varied diet may also ensure that a person is consuming sufficient amounts of functional food constituents that, although not defined as nutrients, have biologic effects and may influence health and susceptibility to disease. Examples include foods containing dietary fiber and carotenoids, as well as lesser known phytochemicals (components of plants that have protective or disease-preventive properties) such as isothiocyanates in broccoli or other cruciferous vegetables and lycopene in tomato products (see Chapter 20).

Worldwide Guidelines

Numerous standards serve as guides for planning and evaluating diets and food supplies for individuals and population groups. The Food and Agriculture Organization and the World Health Organization of the United Nations have established international standards in many areas of food quality and safety, as well as dietary and nutrient recommendations. In the United States the Food and Nutrition Board (FNB) of the Institute of Medicine (IOM) has led the development of nutrient recommendations since the 1940s. Since the mid-1990s, nutrient recommendations developed by the FNB have been used by the United States and Canada.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) and U.S. Department Health and Human Services (USDHHS) have a shared responsibility for issuing dietary recommendations, collecting and analyzing food composition data, and formulating regulations for nutrition information on food products. Health Canada is the agency responsible for Canadian dietary recommendations; in Australia, the guidelines are available through the National Health and Medical Research Council. The Japan Dietetic Association updates their guidelines every four years, the latest designed as the “Spinning Top” from the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare. Indeed, many countries have issued guidelines appropriate for the circumstances and needs of their populations.

Dietary Reference Intakes

American standards for nutrient requirements have been the recommended dietary allowances (RDAs) established by the FNB of the IOM. They were first published in 1941 and most recently revised between 1997 and 2002. Each revision incorporates the most recent research findings. In 1993 the FNB developed a framework for the development of nutrient recommendations, called dietary reference intakes (DRI). Nutrition and health professionals should always use updated food composition databases and tables and inquire whether data used in computerized nutrient analysis programs have been revised to include the most up-to-date information. An interactive DRI calculator is available at http://fnic.nal.usda.gov/interactiveDRI/.

Estimated Safe and Adequate Daily Dietary Intakes

Numerous nutrients are known to be essential for life and health, but data for some are insufficient to establish a recommended intake. Intakes for these nutrients are estimated safe and adequate daily dietary intakes (ESADDIs). Most intakes are shown as ranges to indicate that not only are specific recommendations not known, but also at least the upper and lower limits of safety should be observed.

DRI Components

The DRI model expands the previous RDA, which focused only on levels of nutrients for healthy populations to prevent deficiency diseases. To respond to scientific advances in diet and health throughout the life cycle, the DRI model now includes four reference points: adequate intake (AI), estimated average intake (EAR), RDA, and tolerable upper intake level (UL).

The adequate intake (AI) is a nutrient recommendation based on observed or experimentally determined approximation of nutrient intake by a group (or groups) of healthy people when sufficient scientific evidence is not available to calculate an RDA or an EAR. Some key nutrients are expressed as an AI, including calcium (see Chapter 3). The estimated average requirement (EAR) is the average requirement of a nutrient for healthy individuals; a functional or clinical assessment has been conducted, and measures of adequacy have been determined. An EAR is the amount of a nutrient with which approximately one half of individuals would have their needs met and one half would not. The EAR should be used for assessing the nutrient adequacy of populations, but not for individuals.

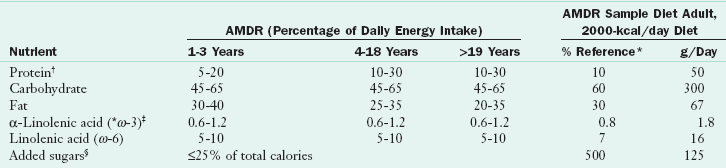

The recommended dietary allowance (RDA) presents the amount of a nutrient needed to meet the requirements of almost all (97% to 98%) of the healthy population of individuals for whom it was developed. An RDA for a nutrient should serve as a goal for intake for individuals, not as a benchmark for adequacy of diets of populations. Finally the tolerable upper intake level (UL) was established for many nutrients to reduce the risk of adverse or toxic effects from consumption of nutrients in concentrated forms—either alone or combined with others (not in food)—or from enrichment and fortification. A UL is the highest level of daily nutrient intake that is unlikely to have any adverse health effects on almost all individuals in the general population. The DRIs for the macronutrients, vitamins and minerals, including the ULs are presented on the inside front cover and opening page of this text. The acceptable macronutrient distribution ranges are based on energy intake by age and sex. See Table 12-1 and the DRI tables on the inside front cover of this text.

TABLE 12-1

Acceptable Macronutrient Distribution Ranges

AMDR, Acceptable macronutrient distribution range; DHA, docosahexaenoic acid; DRI, dietary reference intake; EPA, eicosapentaenoic acid.

*Suggested maximum.

†Higher number in protein AMDR is set to complement AMDRs for carbohydrate and fat, not because it is a recommended upper limit in the range of calories from protein.

‡Up to 10% of the AMDR for α-linolenic acid can be consumed as EPA, DHA, or both (0.06%-0.12% of calories).

§Reference percentages chosen based on average DRI for protein for adult men and women, then calculated back to percentage of calories. Carbohydrate and fat percentages chosen based on difference from protein and balanced with other federal dietary recommendations.

Modified from Food and Nutrition Board, Institute of Medicine: Dietary reference intakes for energy, carbohydrate, fiber, fat, fatty acids, cholesterol, protein, and amino acids, Washington DC, 2002, National Academies Press.

Target Population

Each of the nutrient recommendation categories in the DRI system is used for specific purposes among individuals or populations. The EAR is used for evaluating the nutrient intake of populations. The AI and RDA can be used for individuals. Nutrient intakes between the RDA and the UL may further define intakes that may promote health or prevent disease in the individual.

Age and Gender Groups

Because nutrient needs are highly individualized depending on age, sexual development, and the reproductive status of females, the DRI framework has 10 age groupings, including age-group categories for children, men and women 51 to 70 years of age, and those older than 70 years of age. It separates three age-group categories each for pregnancy and lactation—younger than 18 years, 19 to 30 years, and 31 to 50 years of age.

Reference Men and Women

The requirement for many nutrients is based on body weight, according to reference men and women of designated height and weight. These values for age-sex groups of individuals older than 19 years of age are based on actual medians obtained for the American population by the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988 to 1994. Although this does not necessarily imply that these weight-for-height values are ideal, at least they make it possible to define recommended allowances appropriate for the largest number of people.

Nutritional Status of Americans

Information about the diet and nutritional status of Americans and the relationship between diet and health is collected by 22 federal agencies. This effort is coordinated by the USDA and USDHHS through the National Nutrition Monitoring and Related Research Program, (See Chapter 10). Overall, analysis of the American diet shows that the population is slowly changing eating patterns and adopting more healthy diets. Intake of total fat, saturated fatty acids, and cholesterol has decreased in some segments of the population; servings of fruits and vegetables have risen to four per day. Hospitals have even taken on the challenge for healthier food intake (see Focus On: The “Healthy Food In Health Care” Pledge).

Unfortunately, gaps still exist between actual consumption and government recommendations in certain population subgroups. Nutrition-related health measurements indicate that overweight and obesity are increasing from lack of physical activity. Hypertension remains a major public health problem in middle-age and older adults and in non-Hispanic blacks in whom it increases the risk of stroke and coronary heart disease. Osteoporosis develops more often among non-Hispanic whites than non-Hispanic blacks. Finally, in spite of available choices, many Americans experience food insecurity, meaning that they lack access to adequate and safe food for an active, healthy life. Table 12-2 provides a list of food components and public health concerns related to those components.

TABLE 12-2

Food Components and Public Health Concerns

| Food Component | Relevance to Public Health |

| Energy | The high prevalence of overweight indicates that an energy imbalance exists among Americans because of physical inactivity and underreporting of energy intake or food consumption in national surveys. |

| Total fat, saturated fat, and cholesterol | Intakes of fat, saturated fatty acids, and cholesterol among all age groups older than 2 years of age are above recommended levels. Cholesterol intakes are generally within the recommended range of 300 mg/dL or less. |

| Alcohol | Intake of alcohol is a public health concern because it displaces food sources of nutrients and has potential health consequences. |

| Iron and calcium | Low intakes of iron and calcium continue to be a public health concern, particularly among infants and females of childbearing age. Prevalence of iron deficiency anemia is higher among these groups than among other age and sex groups. Low calcium intake is a particular concern among adolescent girls and adult women in most racial and ethnic groups. |

| Sodium* | Sodium intake exceeds government recommendations of 2300 mg/day in most age and sex groups. Strategies to lower intake can be found at the Institute of Medicine website at http://www.iom.edu/Reports/2010/Strategies-to-Reduce-Sodium-Intake-in-the-United-States.aspx |

| Other nutrients at potential risk | Some population or age groups may consume insufficient amounts of total carbohydrate and carbohydrate constituents such as dietary fiber; protein; vitamin A; carotenoids; antioxidant vitamins C and E; folate, vitamins B6. and B12; magnesium, potassium, zinc, copper, selenium, phosphorus, and fluoride. Studies also suggest that vitamin D deficiency is very common. |

| Unbalanced Nutrients | Intakes of polyunsaturated and monounsaturated fatty acids, trans-fatty acids, and fat substitutes are often excessive. |

*Recommended intake of 1500 mg or less in at-risk populations defined as African-Americans, people with hypertension, and anyone 40 years or older (IOM, 2004).

Healthy Eating Index

The Center for Nutrition Policy and Promotion of the USDA releases the Healthy Eating Index (HEI) to measure how well people’s diets conform to recommended healthy eating patterns. The index provides a picture of foods people are eating, the amount of variety in their diets, and compliance with specific recommendations in the Dietary Guidelines for Americans (DGA). The HEI is designed to assess and monitor the dietary status of Americans by evaluating 10 components, each representing different aspects of a healthy diet. The dietary components used in the evaluation include grains, vegetables, fruits, milk, meat, total fat, saturated fat, cholesterol, sodium, and variety. Data from the HEI over time show that Americans are reducing total and saturated fat and eating a wider variety of foods. The 2005 report suggests that milk intake is still low (Guenther et al., 2008). The overall HEI score ranges from 0 to 100. Interestingly, women generally have scores higher than men, and toddlers have the highest scores.

Nutrition Monitoring Report

At the request of the USDHHS and USDA, the Expert Panel on Nutrition Monitoring was established by the Life Sciences Research Office of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology to review the dietary and nutritional status of the American population. In general, the committee concluded that the food supply in the United States is abundant, although some people may not receive enough nutrients for various reasons. Nutrient intakes are most likely to be low in persons living below the poverty level. Intakes of nutrients reported to be low in the general population are even lower in the poverty group. Chapter 10 describes this report more fully.

National Guidelines For Diet Planning

Eating can be one of life’s greatest pleasures. People eat for enjoyment and to obtain energy and nutrients. Although many genetic, environmental, behavioral, and cultural factors affect health, diet is equally important for promoting health and preventing disease. Yet within the past 40 years, attention has been focused increasingly on the relationship of nutrition to chronic diseases and conditions. Although this interest derives somewhat from the rapid increase in number of older adults and their longevity, it is also prompted by the desire to prevent premature deaths from diseases such as coronary heart disease, diabetes mellitus, and cancer. Approximately two thirds of deaths in the United States are caused by chronic disease.

Current Dietary Guidance

In 1969 President Nixon convened the White House Conference on Nutrition and Health (AJCN, 1969). Increased attention was being given to prevention of hunger and disease. The development of dietary guidelines in the United States is discussed in Chapter 10. Guidelines directed toward prevention of a particular disease, such as those from the National Cancer Institute; the American Diabetes Association; the American Heart Association; and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute’s cholesterol education guidelines, contain recommendations unique to particular conditions. The American Dietetic Association supports a total diet approach, in which the overall pattern of food eaten, consumed in moderation with appropriate portion sizes and combined with regular physical activity, is key. Various guidelines that can be used by health counselors throughout the developed world are summarized in Box 12-1.

Implementing the Guidelines

The task of planning nutritious meals centers on including the essential nutrients in sufficient amounts as outlined in the newest DRIs, in addition to appropriate amounts of energy, protein, carbohydrate (including fiber and sugars), fat (especially saturated and trans-fats), cholesterol, and salt. Suggestions are included to help people meet the specifics of the recommendations. When specific numeric recommendations differ, they are presented as ranges.

To help people select an eating pattern that achieves specific health promotion or disease prevention objectives, nutritionists should assist individuals in making food choices (e.g., to reduce fat, to increase fiber). Although numerous federal agencies are involved in the issuance of dietary guidance, the USDA and USDHHS lead the effort. The Dietary Guidelines for Americans (DGA) were first published in 1980 and are revised every five years; the most recent guidelines were released in 2010 (Box 12-2). The DGA are designed to motivate consumers to change their eating and activity patterns by providing them with positive, simple messages. Using consumer research, the DGA develop messages that expand the influence of the dietary guidelines to encourage consumers to adopt them and ultimately change their behaviors. The messages reach out to consumers’ motivations, individual needs, and life goals, and can be used in education, counseling, and communications initiatives (USDA, 2005).

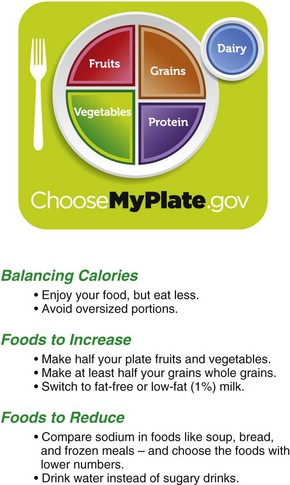

The MyPlate Food Guidance System, shown in Figure 12-1, replaces the MyPyramid and offers a guide for daily food choices and portions. Consumers can use chooseMyPlate.gov as a resource.

FIGURE 12-1 MyPlate showing the five essential food groups. (From the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). Accessed June 10, 2011 from http://www.chooseMyPlate.gov/.)

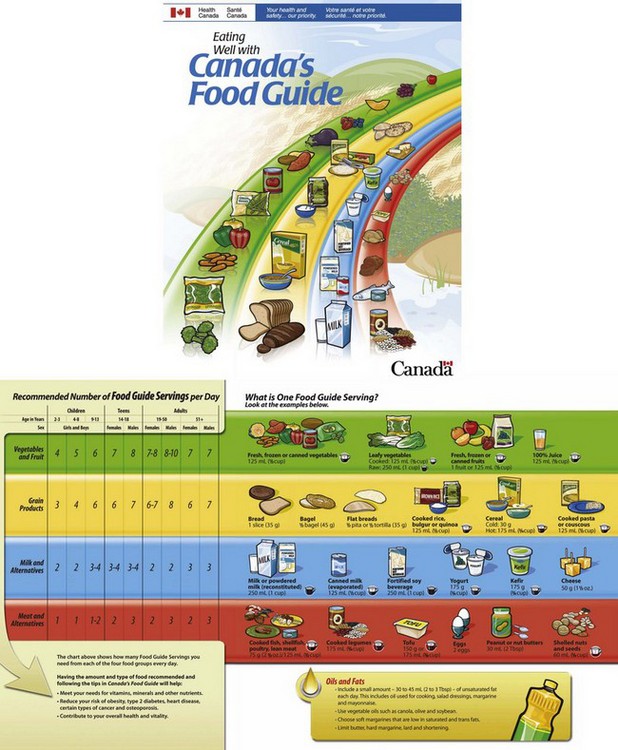

For comparison, see the Eating Well with Canada’s Food Guide as shown in Clinical Insight: Nutrition Recommendations for Canadians and Figure 12-2.

FIGURE 12-2 Eating well with Canada’s food guide. (Reprinted with permission from Health Canada. Data from Health Canada: Eating well with Canada’s food guide, Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, represented by the Minister of Healthy Canada, 2007. Accessed 22 May 2010 from www.hc-sc.gc.ca/fn-an/food-guide-aliment.

Food and Nutrient Labeling

To help consumers make choices between similar types of food products that can be incorporated into a healthy diet, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) established a voluntary system of providing selected nutrient information on food labels. The regulatory framework for nutrition information on food labels was revised and updated by the USDA (which regulates meat and poultry products and eggs) and the FDA (which regulates all other foods) with enactment of the Nutrition Labeling and Education Act (NLEA) in 1990. The labels became mandatory in 1994.

Mandatory Nutrition Labeling

As a result of the NLEA, nutrition labels must appear on most foods except products that provide few nutrients (such as coffee and spices), restaurant foods, and ready-to-eat foods prepared on site, such as supermarket bakery and deli items. Providing nutrition information on many raw foods is voluntary. However, the FDA and USDA have called for a voluntary point-of-purchase program in which nutrition information is available in most supermarkets. Nutrition information is provided through brochures or point-of-purchase posters for the 20 most popular fruits, vegetables, and fresh fish and the 45 major cuts of fresh meat and poultry.

Nutrition information for foods purchased in restaurants is widely available at the point of purchase or from Internet sites or toll-free numbers. New legislation may require chains with 20 or more locations to disclose on their menus or menu board the number of calories per menu item, with additional nutrition information including total calories and calories from fat, and amounts of fat, saturated fat, cholesterol, sodium, total carbohydrates, complex carbohydrates, sugars, dietary fiber, and protein available upon request.

Ready-to-eat unpackaged foods in delicatessens or supermarkets may provide nutrition information voluntarily. However, if nutrition claims are made, nutrition labeling is required at the point of purchase. If a food makes the claim of being organic, it also must meet certain criteria and labeling requirements.

Standardized Serving Sizes on Food Label

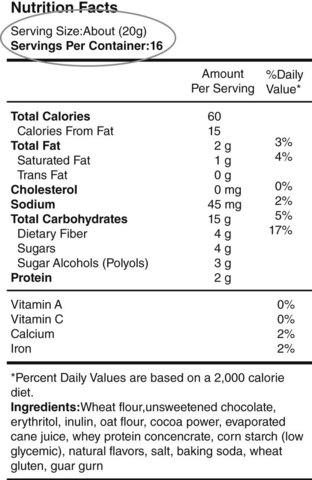

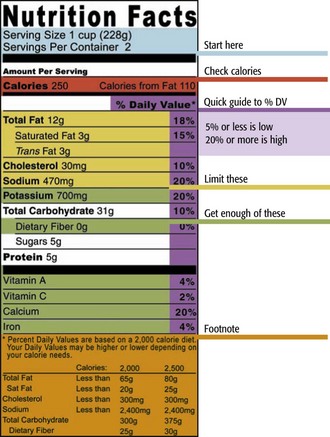

Serving sizes of products are set by the government based on reference amounts commonly consumed. For example, a serving of milk is 8 oz, and a serving of salad dressing is 2 tbsp. Standardized serving sizes make it easier for consumers to compare the nutrient contents of similar products (Figure 12-3).

Nutrition Facts Label

The nutrition facts label on a food product provides information on its per-serving calories and calories from fat. The label must list the amount (in grams) of total fat, saturated fat, trans fat, cholesterol, sodium, total carbohydrate, dietary fiber, sugar, and protein. For most of these nutrients the label also shows the percentage of the daily value (DV) supplied by a serving, showing how a product fits into an overall diet by comparing its nutrient content with recommended intakes of those nutrients. DVs are not recommended intakes for individuals; they are simply reference points to provide some perspective on daily nutrient needs. DVs are based on a 2000-kcal diet. For example, individuals who consume diets supplying more or fewer calories can still use the DVs as a rough guide to ensure that they are getting adequate amounts of vitamin C but not too much saturated fat.

The DVs exist for nutrients for which RDAs already exist (in which case they are known as reference daily intakes [RDIs]) (Table 12-3) and for which no RDAs exist (in which case they are known as daily reference values [DRVs] [Table 12-4]). However, food labels use only the term daily value. RDIs provide a large margin of safety; in general, the RDI for a nutrient is greater than the RDA for a specific age-group. The term RDI replaces the term U.S. RDAs used on previous food labels. The previously mentioned nutrients must be listed on the food label.

TABLE 12-3

| Nutrient | Amount |

| Vitamin A | 5000 IU |

| Vitamin C | 60 mg |

| Thiamin | 1.5 mg |

| Riboflavin | 1.7 mg |

| Niacin | 20 mg |

| Calcium | 1 g |

| Iron | 18 mg |

| Vitamin D | 400 IU |

| Vitamin E | 30 IU |

| Vitamin B6 | 2 mg |

| Folic acid | 0.4 |

| Vitamin B12 | 6 mcg |

| Phosphorus | 1 g |

| Iodine | 150 mcg |

| Magnesium | 400 mg |

| Zinc | 15 mg |

| Copper | 2 mg |

| Biotin | 0.3 mg |

| Pantothenic acid | 10 mg |

| Selenium | 70 mcg |

From Center for Food Safety & Applied Nutrition: A food labeling guide, College Park, Md, 1994, U.S. Department of Agriculture, revised 1999.

TABLE 12-4

| Food Component | DRV | Calculation |

| Fat | 65 g | 30% of kcal |

| Saturated fat | 20 g | 10% of kcal |

| Cholesterol | 300 mg | Same regardless of kcal |

| Carbohydrates (total) | 300 g | 60% of calories |

| Fiber | 25 g | 11.5 g per 1000 kcal |

| Protein | 50 g | 10% of kcal |

| Sodium | 2400 mg | Same regardless of kcal |

| Potassium | 3500 mg | Same regardless of kcal |

NOTE: The DRVs were established for adults and children over 4 years old. The values for energy yielding nutrients below are based on 2,000 calories per day.

As new DRIs are developed in various categories, labeling laws are updated. Figure 12-4 shows a sample nutrition facts label, and Box 12-3 provides tips for reading and understanding food labels. The FDA has a helpful website to assist consumers with reading labels (http://www.fda.gov/Food/LabelingNutrition/ConsumerInformation/UCM078889.htm).

FIGURE 12-4 Nutrition facts label information. (Source: U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Accessed 22 May 2010 from http://www.health.gov/dietaryguidelines/dga2005/healthieryou/html/tips_food_label.html.)

Nutrient Content Claims

Nutrient content terms such as reduced sodium, fat free, low calorie, and healthy must now meet government definitions that apply to all foods (Box 12-4). For example, lean refers to a serving of meat, poultry, seafood, or game meat with less than 10 g of fat, less than 4 g of saturated fat, and less than 95 mg of cholesterol per serving or per 100 g. Extra lean meat or poultry contains less than 5 g of fat, less than 2 g of saturated fat, and the same cholesterol content as lean, per serving, or per 100 g of product.

Health Claims

A health claim is allowed only on appropriate food products that meet specified standards. The government requires that health claims be worded in ways that are not misleading (e.g., the claim cannot imply that the food product itself helps prevent disease). Health claims cannot appear on foods that supply more than 20% of the DV for fat, saturated fat, cholesterol, and sodium. The following is an example of a health claim for dietary fiber and cancer: “Low-fat diets rich in fiber-containing grain products, fruits, and vegetables may reduce the risk of some types of cancer, a disease associated with many factors.” Box 12-5 lists health claims that manufacturers can use to describe food-disease relationships.

Dietary Patterns and Counseling Tips

Vegetarian diets are popular. Those who choose them may be motivated by philosophic, religious, or ecologic concerns, or by a desire to have a healthier lifestyle. Considerable evidence attests to the health benefits of a vegetarian diet. Studies of Seventh-Day Adventists indicate that the diet results in lower rates of type 2 diabetes, breast and colon cancer, and cardiovascular and gallbladder disease.

Of the millions of Americans who call themselves vegetarians, many eliminate “red” meats but eat fish, poultry, and dairy products. A lactovegetarian does not eat meat, fish, poultry, or eggs, but does consume milk, cheese, and other dairy products. A lactoovovegetarian also consumes eggs. A vegan does not eat any food of animal origin. The vegan diet is the only vegetarian diet that has any real risk of providing inadequate nutrition, but this risk can be avoided by careful planning (American Dietetic Association [ADA], 2009). A new type of semivegetarian is known as a flexitarian. Flexitarians generally adhere to a vegetarian diet for the purpose of good health and do not follow a specific ideology. They view an occasional meat meal as acceptable.

Vegetarian diets tend to be lower in iron than omnivorous diets, although the nonheme iron in fruits, vegetables, and unrefined cereals is usually accompanied either in the food or in the meal by large amounts of ascorbic acid that aids in iron assimilation. Vegetarians do not have a greater risk of iron deficiency than those who are not vegetarians (ADA, 2009). Vegetarians who consume no dairy products may have low calcium intakes, and vitamin D intakes may be inadequate among those in northern latitudes where there is less exposure to sunshine. The calcium in some vegetables is inactivated by the presence of oxalates. Although phytates in unrefined cereals also can inactivate calcium, this is not a problem for Western vegetarians, whose diets tend to be based more on fruits and vegetables than on the unrefined cereals of Middle Eastern cultures. Long-term vegans may develop megaloblastic anemia because of a deficiency of vitamin B12, found only in foods of animal origin. The high levels of folate in vegan diets may mask the neurologic damage of a vitamin B12 deficiency. Vegans should have a reliable source of vitamin B12 such as fortified breakfast cereals, soy beverages, or a supplement. Although most vegetarians meet or exceed the requirements for protein, their diets tend to be lower in protein than those of omnivores. This lower intake may help vegetarians retain more calcium from their diets. Furthermore, lower protein intake usually results in lower dietary fat because many high-protein animal products are also rich in fat (ADA, 2009).

Well-planned vegetarian diets are safe for infants, children, and adolescents and can meet all of their nutritional requirements for growth. They are also adequate for pregnant and lactating females. The key is that the diets be well planned. Vegetarians should pay special attention to ensure that they get adequate calcium, iron, zinc, and vitamins B12 and D. Calculated combinations of complementary protein sources is not necessary, especially if protein sources are reasonably varied. Table 12-5 highlights many of the phytochemicals and functional components rich in many vegetable-based diets. A useful website on vegetarian meal planning is available at http://www.eatright.org/ through the American Dietetic Association. See also Focus On: The “Healthy Food In Health Care” Pledge earlier in the chapter.

Cultural Aspects of Dietary Planning

To plan diets for individuals or groups that are appropriate from a health and nutrition perspective, it is important that registered dietitians and health providers use resources that are targeted to the specific client or group. Numerous population subgroups in the United States and throughout the world have specific cultural, ethnic, or religious beliefs and practices to consider. These groups have their own set of dietary practices or beliefs, which are important when considering dietary planning (Diabetes Care and Education Dietetic Practice Group, 2010). The IOM report entitled Unequal Treatment recommends that all health care professionals receive training in cross-cultural communication to reduce ethnic and racial disparities in health care; indeed, cultural competence is central to professionalism and quality (Betancourt and Green, 2010).

Attitudes, rituals, and practices surrounding food are part of every culture in the world and there are so many cultures in the world that it defies enumeration. Many world cultures have influenced American cultures as a result of immigration and intermarriage. This makes planning a menu that embraces cultural diversity and is sensitive to the needs of a specific group of people a major challenge. It is tempting to simplify the role of culture by attempting to categorize dietary patterns by race, ethnicity, or religion. However, this type of generalizing can lead to inappropriate labeling and misunderstanding.

To illustrate this point, consider the case of Native Americans. There are more than 500 different tribes spread across all 50 states. The food and customs of the tribes in the Southwest are drastically different than those of the Northwest. When discussing traditional foods among Native Americans, the situation is further complicated by the fact that many tribes were removed from their traditional lands by the U.S. government. Thus a Montana tribe that once depended on hunting bison and gathering local roots and berries may now be living in Oklahoma.

Another example of the complexity of diet and culture in the United State is that of African Americans. “Soul food” is commonly identified with African Americans from the South. Traditional food choices include grits, collard greens prepared with ham hocks and lard, with a side of corn bread. But this by no means represents the diet of all African Americans. African Americans may be eating the foods of their homeland. An Ethiopian meal might consist of a vegetable stew served atop bread known as injera, whereas someone eating the food of Ghana would probably be eating a stew atop rice or yams.

When faced with planning a diet to meet the needs of an unfamiliar culture, it is important to avoid forming opinions that are based on inaccurate information or stereotyping (see Chapter 15). Some cultural food guides have even been developed for specific populations (Figure 12-5) for helping to manage disease conditions.

FIGURE 12-5 El Plato del Bien Comer. (The Plate of Good Eating.) (Norma Oficial Mexicana NOM-043-SSA2-2005. Servicios básicos de salud. Promoción y educación para la salud en materia alimentaria. Criterios para brindar orientación. México, DF. Diario Oficial de la Federación, 23 de enero de 2006. Official Mexican Standard NOM-043-SSA2-2005. Basic health services. Promotion and health education with regard to food. Criteria for counseling. Government Gazzette. Mexico, January 23, 2006.)

Religion and Food

Dietary practices have been a component of religious practice for all of recorded history. Some religions forbid the eating of certain foods and beverages; others restrict foods and drinks during holy days. Specific dietary rituals may be assigned to members with designated authority or with special spiritual power (e.g., medicine men, priests). Sometimes dietary rituals or restrictions are observed based on gender. Dietary and food preparation practices (e.g., halal and kosher meat preparation) can be associated with rituals of faith.

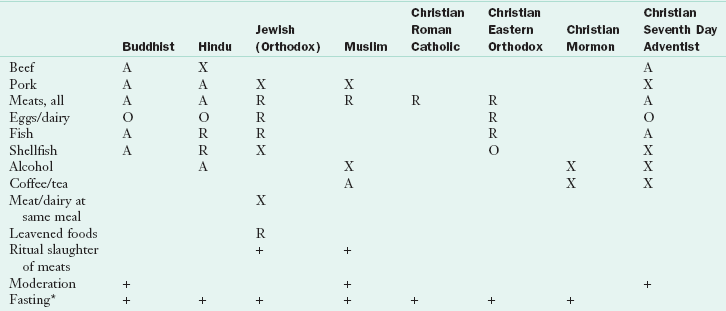

Fasting is practiced by many religions. It has been identified as a mechanism that allows one to improve one’s body, to earn approval (as with Allah or Buddha), or to understand and appreciate the sufferings of others. Attention to specific eating behaviors such as overeating, use of alcoholic or stimulant-containing beverages, and vegetarianism are also considered by some religions. Before planning menus for members of any religious group, it is important to gain an understanding of some traditions or dietary practices (Table 12-6). In all cases, discussing the personal dietary preferences of an individual is imperative (Kittler and Sucher, 2008).

TABLE 12-6

Some Religious Dietary Practices

Escott-Stump S: Nutrition and diagnosis-related care, ed 7, Baltimore, Md, 2011, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

+, Practiced; A, avoided by the most devout; O, permitted, but may be avoided at some observances; R, some restrictions regarding types of foods or when a food may be eaten; X, prohibited or strongly discouraged.

*Fasting varies from partial (abstention from certain foods or meals) to complete (no food or drink).

Modified from Kittler PG, Sucher KP: Food and culture, ed 5, Belmont, Ca, 2008, Wadsworth/Cengage Learning.

Center for Nutrition Policy and Promotion, U.S. Department of Agriculture

Centers for Disease Control—Health Literacy

http://www.cdc.gov/healthmarketing/healthliteracy/training/page5711.html

http://www.cnpp.usda.gov/USDAFoodCost-Home.htm

Dietary Guidelines for Americans

http://www.health.gov/DietaryGuidelines

http://www.fns.usda.gov/eatsmartplayhardkids/

http://fnic.nal.usda.gov/nal_display/index.php?info_center=4&tax_level=3&_tax_subject=256&topic_id=1348&level3_id=5732

Food and Drug Administration, Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition

Food and Nutrition Information Center, National Agricultural Library, U.S. Department of Agriculture

http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/fn-an/index_e.html

http://www.cnpp.usda.gov/HealthyEatingIndex.htm

Institute of Medicine, National Academy of Sciences

International Food Information Council

National Center for Health Statistics

http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes.htm

Nutrition.gov (U.S. government nutrition site)

References

American Dietetic Association (ADA). Position of the American Dietetic Association: vegetarian diets. J Am Diet Assoc. 2009;109:1266.

American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. White House Conference on Food, Nutrition and Health. AJCN. 1969;11:1543.

Betancourt, JR, Green, AR. Commentary: linking cultural competence training to improved health outcomes: perspectives from the field. Acad Med. 2010;85:583.

Diabetes Care and Education Dietetic Practice Group. Goody CM, Drago L, eds. Cultural food practices. Chicago: American Dietetic Association, 2010.

Guenther, P, et al. Healthy eating index. J Am Diet Assoc. 2008;108:1854–1864.

Health Canada. Eating well with Canada’s food guide. Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, represented by the Minister of Healthy Canada, 2007. Accessed 18 January 2010 from www.hc-sc.gc.ca/fn-an/food-guide-aliment.

Institute of Medicine (IOM), Food and Nutrition Board, Consensus Report: Dietary reference intakes: water, potassium, sodium, chloride, and sulfate. Accessed 11 March, 2011 at http://www.iom.edu/reports/2004/dietary-reference-intakes-water-potassium-sodium-chloride-and-sulfate.aspx.

Kittler, PG, Sucher, KP. Food and culture, ed 5. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth/Cengage Learning; 2008.

Pollan, M. The omnivore’s dilemma: a natural history of four meals. New York: Penguin; 2006.

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Center for Nutrition Policy and Promotion. Healthy eating index 2005. Accessed 16 April 2007 from www.cnpp.usda.gov.