Chapter 16 Special exercises for pregnancy and the puerperium

The information in this chapter is relevant for group practice, or for use on a one-to-one basis, and includes advice for the whole of the childbearing year. For this purpose, the childbearing year is defined as the 12-month period between conception and 12 weeks postpartum.

The role of the women’s health physiotherapist

The women’s health physiotherapist is part of the multidisciplinary team caring for women in pregnancy, labour and the puerperium. Working together with midwives, both are ideally placed to promote good health and fitness during a woman’s childbearing year and to prevent, identify and treat problems. This physiotherapist is specially trained to work with women at any stage of their lives in the specific areas of obstetrics, including pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain, gynaecology and urology/continence, with both in- and outpatients.

A combined approach from the women’s health physiotherapist, midwives, health visitors and other health professionals can provide an opportunity for education, discussion and health promotion in a group setting. They should aim to create a learning environment with a relaxed atmosphere, where parents-to-be can enjoy developing the confidence to cope with pregnancy, labour, birth and the early postnatal days. The physiotherapist is the ideal choice to teach the physical skills required for parenthood. However, where no physiotherapist is available, midwives may find themselves responsible for physical preparation as well as parent education in antenatal classes or on a one-to-one basis.

Anatomy, anatomical and physiological changes

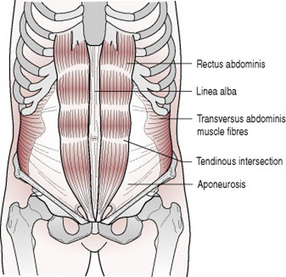

Four pairs of abdominal muscles combine to form the anterior and lateral abdominal wall, and may be termed the abdominal corset. The deepest of the group is the transversus abdominis (TrA) which lies deep to the internal abdominal oblique (IO) and external abdominal oblique (EO) with the rectus abdominis (RA) central, anterior and superficial.

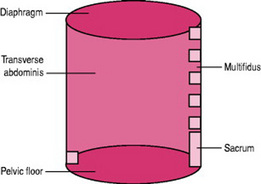

The deep muscles of the abdomen together with the pelvic floor muscles, multifidus (a deep muscle of the back) and the diaphragm, can be considered as a complete unit and may be termed the lumbopelvic cylinder (Fig. 16.1). When advising on exercise programmes relating to back-care and continence it is appropriate to consider the muscles of the cylinder as a working unit.

The coordinated actions of these muscles increase intra-abdominal pressure. At a high level, this facilitates expulsive actions of defaecation, micturition and parturition if in conjunction with a relaxed pelvic floor; and coughing, sneezing or vomiting if the diaphragm is relaxed. At a lower level, muscle activity exerts a force on the thoracolumbar fascia and a rise in intra-abdominal pressure that contributes to lumbar spine stability, crucial to pain-free resting posture and normal function.

The motor control of the muscles of the lumbopelvic cylinder is also significant in maintaining continence, controlling respiration and supporting the abdominal organs.

Optimal function of these muscles depends on timing of their recruitment, endurance, strength and coordination. This can be adversely affected by pain, postural malalignment, deficient nerve supply or fascial attachment.

The abdominal corset

The characteristics of the muscle fibres within the abdominal corset are variable.

The deepest TrA muscle is mainly slow twitch muscle fibres that are designed for endurance and postural control. The middle IO and EO muscles are a mix of slow and fast twitch fibres. This combination controls motion throughout movement, and may work eccentrically to decelerate movement, especially rotation. The most superficial RA has a bigger proportion of fast twitch muscle fibres that can produce and accelerate movement and act as shock absorbers of high loads.

The coordinated actions of all these muscles facilitate the maintenance of sustained postures and normal, pain-free movement of the lumbar spine.

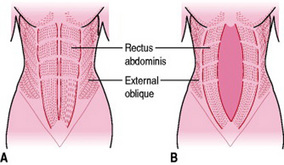

The RA (Fig. 16.2) is a pair of two parallel long flat muscles, which extend vertically on each side of the midline along the front of the abdomen, being broader and thinner above the umbilicus than below and separated by a band of connective tissue called the linea alba (white line). Contained within the rectus sheath, it extends inferiorly from the pubic symphysis to the xiphisternum and lower costal cartilages superiorly. The RA is a key postural muscle controlling pelvic girdle tilt and flexing the lumbar spine, as when doing a ‘sit-up’. RA is assisted by EO and IO and works with the abdominal muscles to raise intra-abdominal pressure. By its attachment to the pubic symphysis it contributes to stability of this joint.

If the RA is bilaterally weak, posterior pelvic tilt will be much more difficult to control and perform, as will head and shoulder raising in the supine position. The difficulty in controlling pelvic tilt may increase the lumbar lordosis with possible associated low back pain.

As the baby grows during pregnancy, the two parallel rectus muscles within the rectus sheath elongate and move apart and may overstretch the linea alba. This is termed diastasis rectus abdominis muscle (DRAM).

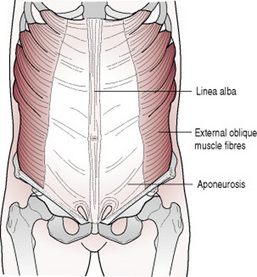

The EO muscles (Fig. 16.3) are the largest and the most superficial of the flat muscles and are situated on the anterolateral aspect of each side of the abdomen. Each is broad, thin and irregularly quadrilateral; its muscular portion occupies the side of the abdomen and its aponeurosis (a flat tendon composed of layers of collagen fibres), the anterior wall.

The main muscle fibres run obliquely downwards and medially from the outer borders and costal cartilages of the lower ribs and insert by the aponeurosis into the linea alba forming the anterior part of the rectus sheath. The most lateral fibres pass from the lower four ribs almost vertically down to insert as the inguinal ligament.

The EO compresses the abdominal cavity, which increases the intra-abdominal pressure. It also participates in both flexion and side flexion and produces and controls rotation of the vertebral column.

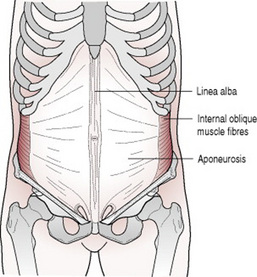

The IO muscles (Fig. 16.4) form the middle layer of the flat abdominal muscles, lying just underneath the EO and just superficial to TrA. The fibres arise from the inguinal ligament, iliac crest and thoracolumbar fascia. Fibres insert into the crest of the pubis, pectineal line and upwards and medially at right angles to those of external oblique, by an aponeurosis, into the linea alba forming the posterior part of the rectus sheath as it passes behind RA. The most posterior fibres run vertically upwards to insert in the lower ribs.

The lower anterior fibres of the IO muscles work with TrA to compress and support the lower abdominal viscera. The upper anterior fibres of both IOs contract to flex the spine, support and compress the abdominal viscera, depress the thorax and assist in respiration. Contracting unilaterally, the upper anterior fibres of IO work with the anterior fibres of the EO of the opposite side to produce and control rotation of the vertebral column. The lateral fibres of the IO on one side work with the lateral fibres of the EO on the same side to flex the trunk sideways.

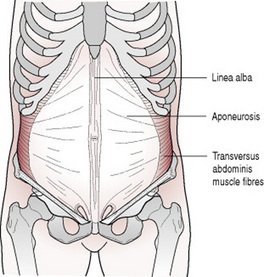

TrA (Fig. 16.5) is a pair of muscles which are the deepest of the abdominal muscle sheets with fibres running transversely from the lateral one third of the inguinal ligament, the anterior two thirds of the inner lip of the iliac crest, the thoracolumbar fascia and the inner surfaces of the costal cartilages of the lower six ribs. Fibres run transversely to form and combine with the broad aponeurosis of the obliques and form the rectus sheath which encases RA and inserts into the linea alba.

The TrA muscles compress the abdominal viscera, giving support similar to a girdle and stabilize the lumbar spine by attachment to the thoracolumbar fascia.

The lumbopelvic cylinder

This consists of the TrA, diaphragm, multifidus and the pelvic floor muscles.

The multifidus consists of a number of fleshy and tendinous fasciculi, the fibres of which pass upwards and medially and fill up the groove on either side of the spinous processes of the vertebrae. These fasciculi vary in length: the most superficial, the longest, pass from one vertebra to the third or fourth above; those next in order run from one vertebra to the second or third above; while the deepest connect two contiguous vertebrae. Multifidus contributes to spinal segmental stability.

The diaphragm is a shelf of muscle extending across the bottom of the ribcage. It separates the thoracic from the abdominopelvic cavity. In its relaxed state, the diaphragm is shaped like a dome. Its convex upper surface forms the floor of the thoracic cavity, and its concave under surface, the roof of the abdominal cavity. Its peripheral part consists of muscular fibres, which take origin from the circumference of the thoracic outlet and converge to be inserted into a central tendon.

The diaphragm is pierced by a series of apertures to permit the passage of structures between the thorax and abdomen, most importantly the aortic, oesophageal and the vena caval openings. It is critically important in respiration. In order to draw air into the lungs, the diaphragm contracts, moving downwards, working with the EI thus enlarging the thoracic cavity and reducing intrathoracic pressure. When the diaphragm relaxes, air is exhaled by elastic recoil of the lung and the tissues lining the thoracic cavity.

It also helps to expel vomit, faeces and urine from the body by increasing intra-abdominal pressure.

The pelvic floor is a fascial and muscular sheet forming the inferior boundary of the abdominopelvic cavity. The main muscular components are the puborectalis, pubococcygeus, iliococcygeus and ischiococcygeus, collectively termed the levator ani (see Ch. 8). It is attached to the inner surface of the side of the lesser pelvis, and unites with its opposite fellow forming the greater part of the floor of the pelvic cavity. It supports the viscera and surrounds the structures, which pass through the cavity.

The coordinated action of levator ani, in the presence of intact fascia, generates a rise in intra-abdominal pressure to maintain organ support and urinary and faecal continence.

Influence of pregnancy on lumbopelvic stability and control of continence

During pregnancy, relaxin and progesterone affect the collagen fibres in fascia, tendons, aponeuroses and linea alba, causing these tissues to become more elastic and less supportive (Ostgaard 1997).

Anatomical and physiological changes

Lumbopelvic stability is the control of neutral position, which allows pain-free movement and effective load transfer through the spine and pelvis. According to Panjabi (1992a,b), this is achieved when the passive, active and neural systems work together. The passive structures are the bones, joints and joint ligaments; the active are the muscles of the abdominal corset and cylinder and the neural are the nerves supplying them. Instability and consequent pain may develop if any of these systems are dysfunctional.

Continence is maintained by a control mechanism of urethral sphincteric control and urethral support. The structures which provide support for the urethra include the passive system of the fascia which is anchored to the inside of the pelvic bones, the active system of the pelvic floor muscles and the neural system of nerves, which control the timing, endurance and strength of the muscle contraction. Stress urinary incontinence can result when there are problems with any of these systems (DeLancey 1994).

There is much evidence that pregnancy and childbirth can disrupt these systems (DeLancey et al 2003). Ashton-Miller et al (2001) demonstrated that overstretch and damage of the ventral and medial parts of pubococcygeus is evident in parous women and not in nulliparae.

Allen et al (1990) showed that vaginal birth causes partial denervation of the pelvic floor in most women having their first baby. This is sometimes severe and associated with urinary or faecal incontinence. Damage is increased during an active second stage longer than 83 min and birthweight over 3.14 kg.

Also, Tetzschner et al (1996) showed that vaginal birth could cause damage and delayed conduction of the pudendal nerve and subsequent decrease in urethral closure pressure. However, for the majority, vaginal birth is the safest and least problematic. Caesarean section should not be considered solely to protect the pelvic floor, as MacLennan et al (2000) showed there is no significant reduction in long-term pelvic floor morbidity associated with caesarean section versus spontaneous vaginal birth.

Safe exercise in the childbearing year

The exercise needs of the disabled woman during the childbearing year should be assessed individually, so that specific advice and information can be given (see Fit and Safe leaflet at: www.acpwh.org.uk).

Exercising during the childbearing year is not harmful to either mother or baby (Artal et al. 2003, Brown 2002, RCOG 2006) if the pregnancy is normal and the mother healthy (Arena and Maffulli 2002, Avery et al 1999, Goodwin et al 2000, Hefferman 2000, Riemann et al. 2000) and can be positively beneficial if at a mild to moderate level. The aims of exercising in pregnancy should be to maintain, or slightly improve, the woman’s level of fitness.

Provided there are no specific obstetric or medical contraindications, fit women can safely maintain the same level of fitness during pregnancy. Pregnant women should not undertake new, vigorous exercise, which could make them too warm, tired or breathless and regular exercisers should reduce the intensity and duration of their training as the pregnancy progresses.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG 2002) states that ‘in the absence of either medical or obstetric complications, 30 min or more of moderate exercise a day on most, if not all, days of the week is recommended for pregnant women’.

All women should be encouraged to exercise at a moderate level to derive the associated health benefits (RCOG 2006). A moderate level is that intensity which can be maintained while able to carry on a conversation. The Borg Scale of Perceived Exertion (Noble et al. 1983), or the Talk Test can be used, preferably at level 3–5 (Table 16.1). This should be used in preference to a heart rate monitor, which is less reliable due to the pregnancy-induced increase in heart rate.

Table 16.1 Borg Scale of Perceived Exertion and Talk Test guidelines

| Borg scale | Level of exertion | Talk test guidelines |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | Nothing at all |

|

| 1 | Very easy | |

| 2 | Easy | |

| 3 | Moderate |

|

| 4 | Somewhat hard | |

| 5 | Hard | |

| 6 |

|

|

| 7 | Very hard | |

| 8 |

|

|

| 9 | ||

| 10 | Maximal |

There are benefits to exercising in the childbearing year. The benefits according to the ACPWH may include:

However, further research on the benefits of exercise in pregnancy is needed and health professionals should remain up to date with current literature.

Most women will fall into one of the following four types of exerciser. Using the Borg Scale of Perceived Exertion is appropriate for all women, whatever their level of fitness or ability.

The non-exerciser These women will dislike exercise and not easily be persuaded of its benefits, especially during pregnancy. They may respond to encouragement to try some basic exercise.

The occasional exerciser These women may recognize the benefit of exercising when pregnant and may wish to increase the level of intensity, duration and regularity. They should be advised to avoid starting a new exercise programme until after the first trimester and should begin simply and gradually, preferably with the supervision of an adequately trained professional to oversee their progress.

The regular exerciser Guidelines for exercise in pregnancy (ACOG 2002) suggest that the woman who exercises regularly should:

The athlete These women are often the most difficult to advise as they are often highly motivated and competitive. They should follow the advice of regular exercisers. A safe level of aerobic exercise for the athlete will depend on the chosen sport and degree of fitness attained (Warren and Shantha 2000). The athlete will inevitably need to lower the intensity and length of her training sessions and they should be aware that the same warnings and contraindications apply as for the regular exerciser.

Advisors of pregnant women athletes regarding safe exercise should remember that research into strenuous activity during pregnancy is limited, so should endeavour to keep updated of new information.

Antenatal exercise

It is best to continue with familiar activities rather than begin new types of exercise and the woman should listen to her body when exercising and stop if she feels uncomfortable, fatigued or unwell.

Basic exercise

Brisk walking during which the Borg Scale/Talk Test is correctly observed is an easy and accessible method of exercising for all.

Common exercise activities

Swimming is excellent exercise if aerobic changes are induced. Pelvic girdle pain can be avoided or reduced by using an alternative leg action during breaststroke so that forced adduction against resistance of the water is prevented. The lumbar spine should remain in the neutral position. The buoyancy of the water offsets the effects of gravity on the body and so tiredness is less likely though muscle strength and flexibility can be maintained or improved. Another effect of immersion in water is that of diuresis. It is sensible to avoid diving during pregnancy.

Exercising in water also raises the plasma beta endorphin levels significantly (McMurray et al 1990) and has a beneficial effect on the respiratory, cardiovascular and musculoskeletal systems and Hartmann and Bung (1999) state that water-based exercise can be highly recommended because of its beneficial effects provided potential dangers and contraindications are observed. Some women find aquanatal classes can fulfil both a social and physical need in a most enjoyable way. The classes should be led by a properly qualified professional following set guidelines (see ACPWH leaflets) and may be found in hospitals or community.

Cycling is a popular form of exercise which allows for good mobility of the lower limbs with the bodyweight supported. It is an easy way to travel, although short distances are preferable and steep hills should be avoided.

Low impact aerobics is an adequate means of maintaining fitness levels. The intensity and duration of exercising may be increased initially to compensate for the high impact aerobic movements but as pregnancy progresses will need to be moderated.

Modified Pilates is a scheme of specially adapted non-aerobic exercises for pregnancy which offer both mental and physical training, targeting the deep postural muscles necessary to develop core stability and postural alignment and working to develop balance, posture, abdominal and back strength. The concentration on TrA and pelvic floor muscle strengthening makes it an ideal preparation for labour and postnatal recovery. A Pilates for Pregnancy video (Jackson 2001) will assist women who cannot get to classes to exercise in their own homes. Many women enjoy Pilates and Yoga but should check the instructor is qualified to teach pregnant women.

Back-care classes give an opportunity to educate and teach good back-care technique for life and can be adapted successfully for the pregnant woman.

Gym-based exercise is also very popular and many women wish to continue their training regimes. Equipment to encourage aerobic activity includes the static bicycle, treadmill or cross-trainer. Good technique is essential when strength training. Pregnant women should use lighter weights than they normally do and use sub-maximal lifts. Varying the exercise and using both upper and lower body muscle groups is good practice. Weights, sets and repetitions should be decreased further as pregnancy progresses (Avery et al 1999). Resistance should be varied according to ability.

Circuit training may be included but rest periods between activities may need to be longer and the intensity of the activity lowered and closely monitored.

Caution should be exercised before trying new types of classes that are introduced from time to time and where possible, seek recommendation of suitability from a physiotherapist.

Energetic and competitive sports activities which include jogging, hiking, rowing, cycling, dancing, skating, cross-country skiing, running and tennis can continue (ACOG 2002, SMA 2002).

Contact sports such as hockey, football or basketball pose a potential threat to the safety of the mother and fetus and should be avoided as should horse riding, skiing, and some racquet sports as they increase the risk of falling.

Special sports such as scuba diving and exertion at altitudes over 6000′ are dangerous.

Contraindications, precautions and warnings

Precautions to exercise in pregnancy

The following conditions may require some caution and it is advisable to seek medical advice before commencing any exercise:

Postnatal exercise

The aim of exercising after the baby is born is gradually to regain and then improve the former level of fitness. Once the baby is born, women should return to exercising as soon as they feel able but this should be a gradual process. Postnatal depression is less likely in women who return to exercising relatively soon after birth but only if the exercise sessions are positive rather than negative experiences (Koltyn & Schultes 1997).

High impact exercise should be avoided for a few months after birth to allow musculoskeletal changes of pregnancy to normalize. In women who experienced pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain, there may be residual associated pelvic muscle imbalance. Increased caution and possible physiotherapy referral is necessary for these women. Athletes may be able to return to their sport more quickly. Pregnancy necessitates a reduction in maximal training but should not have a significant adverse impact on postnatal training regimes (Beilock et al 2001).

Coping skills for labour

Relaxation, breathing techniques, massage and encouragement to move and adopt an upright, or forward leaning, posture during labour will help the woman to cope with the discomfort and pain of contractions.

Relaxation

If feeling threatened, anxious, fearful or in pain, muscle tension increases and the body may unconsciously adopt an extreme posture. This is known as the fight or flight response, preparing the body for action. However, if the cause is not an enemy that can be fought with, or escaped from, the tension persists, becomes exhausting and causes physical changes in heart, lungs and other body systems. Relaxation is concerned with reducing body tension to a minimum and once learned can be used whenever increased tension is a problem. It can be particularly useful during pregnancy and labour and the early postnatal days. The most widely used relaxation technique used in pregnancy and labour is the Mitchell method of physical relaxation.

This technique (Box 16.1) involves a series of instructions and movements, which help the body to move away from the posture, caused by tension and so achieve a position of comfort, ease and relaxation. By following each individual instruction and movement, tension in that part of body will disappear.

Box 16.1 Physiological relaxation technique

For each part of the body where tension manifests itself there is a three-fold instruction:

Lie down comfortably on your side or sit in a chair with back and head supported.

Breathing. To begin the relaxation session take a deep breath in, expanding above the waist and lower ribs, then sigh out easily and continue to breathe gently, keeping the movement fairly low down in the chest.

The shoulders, arms and hands are usually the first areas to respond to stress so begin with these parts.

The teacher moves on to the remainder of the body; the hips, knees, head and face, giving clear, precise instructions which can be found in full in the ACPWH leaflet.

Your body should end up in a position of ease and as relaxed as possible. Breathing is at your normal resting rate.

Relaxation can be adapted as labour progresses by adopting the most comfortable position for you, with easy breathing in the lower part of the chest.

Positions for labour

Early first stage of labour

Research shows that women who use upright positions during the first stage of labour:

A woman in labour should be encouraged to keep mobile and active. If there are no complications, she should try alternative positions of ease as change of position leads to productive uterine contractions (Roberts et al 1983). When discomfort increases, the woman should be encouraged to stay relaxed and concentrate on rhythmical easy breathing during contractions.

Coping with early first stage of labour

The following positions of ease may help during the early stages of labour and can be discussed and practised in the antenatal period:

Pelvic rocking in any of these positions may be helpful.

Deep massage of the lower back or gentle stroking of the abdomen soothes many women and can be taught to the partner at couples’ classes.

Later first stage of labour

As labour progresses, it becomes more difficult to find a comfortable position and frequent changes may be necessary. Many women however, are content to sit back against pillows on the bed at this stage and concentrate on relaxation and breathing. As each contraction builds up, the speed and depth of breathing sometimes alter but mothers must be encouraged to keep it as natural and easy as possible. They may find that ‘sighing out slowly’ (SOS) helps to avoid panic breathing and also relaxes physical tension, especially in the shoulders.

The emotional aspects of the end of the first stage of labour will be explained to couples antenatally and coping strategies need to be discussed. With a premature urge to push, an interrupted outward breath can be introduced (that is, two shorter breaths out followed by a longer breath out). This is often known as ‘pant, pant, blow’ or ‘puff, puff, blow’ breathing and it prevents the diaphragm from fixing with a subsequent increase in intra-abdominal pressure. A change in position will take away some of the urge to push, for example side-lying or prone kneeling with the forehead resting on the hands.

Second stage of labour

A review of research assessing the use of different positions during the second stage of labour showed that women who remained upright or lay on their sides to give birth, were more likely to have a shorter second stage and less likely to have an assisted birth (Gupta & Nikodem 2001).

Midwives can actively encourage women to choose the most comfortable position and to change position as and when they wish. They should acknowledge a preference for being upright in labour and discourage women from lying on their backs (MIDIRS 2003).

Coping with second stage of labour

Positions for second stage will depend on individual choice, method of pain relief and obstetric factors (see Ch. 27).

If there is pain in the pelvic girdle, particularly over the symphysis pubis or sacroiliac joints then undue abduction of the hips (by parting the knees beyond the woman’s pain free range) should be avoided during labour, vaginal examinations and birth. The symphysis pubis joint may be protected from further disruption by limiting hip abduction and maintaining symmetry of hip positions. Prone kneeling or side-lying are the optimum positions for birth (ACPWH PGP leaflet, Fry 1997).

As the contraction starts, the mother is reminded to breathe in and out gently. Only when the urge to push becomes overwhelming should she bear down with the contraction, keeping the pelvic floor relaxed. Breath-holding longer than a few seconds should not be encouraged because of the danger of fetal hypoxia in an already compromised baby (Caldeyro-Barcia 1979).

To prevent pushing while the head is being born, deep panting may be useful.

Breathing control

Respiration is affected by stress and adapted breathing is one of the easiest ways of assisting relaxation. Breathing can be used to increase the depth of relaxation by varying its speed; slower breathing leads to deeper relaxation. Natural rhythmic breathing must not be confused with specific unnatural rates of breathing, which research has proved to be harmful to both mother and fetus (Bush 1992, Caldeyro-Barcia 1979). Women in labour frequently breathe very rapidly at the peak of a contraction but should be encouraged not to do so. Persistent rapid breathing or breath-holding is usually a sign of panic.

Very slow deep breathing can cause hyperventilation, which produces tingling in the fingers and may proceed to carpopedal spasm and even tetany. Rapid shallow breathing or panting is only tracheal and can lead to hypoventilation with subsequent oxygen deprivation. During pregnancy, labour and birth, emphasis should be placed on easy, rhythmic breathing and on avoiding very deep breathing, shallow panting or long periods of breath-holding.

Antenatal and postnatal exercises and advice

Preventing and alleviating the early physical stresses of pregnancy and childbirth, should be taught as a priority. Common consequences of pregnancy and childbirth are the physical problems of pelvic girdle and low back pain or incontinence. The main aim in the postnatal period is to address healthcare needs and give advice and exercises to reduce the risk of future pelvic floor dysfunction or the possibility of long-term back problems, so that the woman may recover normal function free of both pain and symptoms.

Women whose pain or continence problems do not resolve with simple advice and exercises should be referred to a women’s health physiotherapist.

Pain

Some 45% of all pregnant women suffer pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain (PGP) and/or pregnancy-related low back pain (PLBP). Serious pain occurs in 25% of pregnant women and severe disability in 8% of pregnant women (Wu et al 2004).

Pelvic floor dysfunction (PFD) occurs in 52% of all pregnancy-related PGP/PLBP (Pool-Goudzwaard et al 2005).

Pelvic floor dysfunction

Pelvic floor disorders are very common and strongly associated with the female gender, ageing, pregnancy, parity and instrumental birth (MacLennan 2000).

For best compliance with the following advice and exercises, explain, demonstrate, supervise and practice at every opportunity.

Antenatal

Postural awareness and care of the back

Women should be advised that the weight of her baby, her altered centre of gravity and tiredness may alter her posture and place strain on her body, putting her at risk of low back and pelvic girdle pain. Her sustained posture when standing, sitting or lying plus repetitive movements may influence that risk and correction may prevent or reduce pain. Back-care advice should be developed relating to comfortable positions in sitting, standing, lying, general mobility and correct lifting.

Standing

For good standing posture, the centre of the head, shoulders and hips should fall in a line when viewed from the side. Standing tall, with shoulders relaxed, tummy gently drawn in and bottom tucked under, knees straight but not locked, and weight evenly distributed on both feet is advised (Fig. 16.6).

Sitting

The pregnant woman should choose a comfortable chair, which supports both her back and thighs (Fig. 16.7). She should sit well back and if necessary place a small cushion or folded towel behind the lumbar spine for additional comfort. Equal weight should be placed on each of her buttocks to prevent strain on the pelvic ligaments. The seat height should allow the feet to rest on the floor, or a small footstool or cushion may be placed under the feet to raise them slightly. Her workstation should be at the correct height such that she does not need to bend forwards. If relaxing in an easy chair, the head can be supported and the legs elevated slightly on a stool. Legs should not be crossed.

Lying

Sleep is a very valuable commodity during pregnancy and health professionals can advise and help women to find a comfortable position. Lying flat on the back should be discouraged because of the risk of supine hypotension due to pressure from the gravid uterus on the inferior vena cava. However, if she wakes having been lying on her back she should be advised to lie on her side for a few moments before rising slowly. Most women will choose to lie on their side to sleep. Side-lying with pillows under the top forearm and knee is usually a comfortable position, and a small pillow under her waist supporting the increasing weight of her abdomen will help to maintain lumbar spine and pelvic girdle symmetry (Fig. 16.8).

Getting up from lying or rolling over in bed is easiest if she bends her knees, draws in the low abdominal and pelvic floor muscles, then uses her arms to push to roll over or to sit on to the edge of the bed.

Work activities

Women should be encouraged to make sure their seating and workstation is suitable, particularly if sitting for any length of time. Regular changes of task and alteration of positions is beneficial. If the woman’s work involves constant standing she should ensure she sits at regular break times and be very careful if her work involves lifting or great physical effort. Many workplaces offer pregnancy risk assessments to employees.

Lifting and carrying

Lifting heavy or awkward objects should be avoided during pregnancy if at all possible. Twisting or bending while lifting is a particularly high-risk activity. If lifting is unavoidable, the thigh muscles, not those of the back, should take the strain. The abdominal and pelvic floor muscles should be drawn in for support and protection of the back and pelvis before bending the knees, holding the object or toddler close to the body, then lifting with the back straight (Fig. 16.9).

Toddlers should not be carried on one hip, or, at least, advise to alternate the hip. A rucksack carried on the back is much better for the back than a heavy shopping bag.

Pelvic floor exercises

There is evidence that pelvic floor muscle training used during a first pregnancy reduces the prevalence of urinary incontinence at 3 months following birth (Mason et al 2001).

The recommendation for preventive use of physical therapies is that pelvic floor muscle training should be offered to women in their first pregnancy as a preventive strategy for urinary incontinence. However, further studies need to be undertaken to evaluate the role and effectiveness of physical and behavioural therapies and lifestyle modifications in the prevention of urinary incontinence and long-term problems (NICE 2006).

Norwegian studies have shown that antenatal instruction in pelvic floor muscle exercises does reduce the likelihood of incontinence during and after pregnancy. The women in these studies had individual instruction in pelvic floor anatomy and how to contract the pelvic floor muscle correctly. Then they attended a 12-week intensive pelvic floor exercise programme supervised by a physiotherapist and were given a home exercise programme. The pelvic floor muscle strength, measured at 3 months postnatally had improved significantly (Morkved & Bø 2003).

It is impossible to provide this type of intensive women’s health physiotherapy-led programme for all women during their pregnancy in the UK, but it is feasible that the multidisciplinary obstetric team could facilitate a satisfactory level of input to teach the exercises and encourage compliance. Women are regularly seen by their GP, hospital/community midwife or obstetrician and all women should have access to, and an opportunity to attend antenatal classes and receive written information about antenatal care (NICE 2008).

It is the recommendation of the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists that every antenatal patient who is booked in should be asked about urinary and faecal incontinence and be given relevant advice or referral to continence services if symptomatic (RCOG 2006).

There are many opportunities for pelvic floor exercises to be encouraged and for trigger questions relating to urinary symptoms to be asked. The anatomy and function of the pelvic floor muscles should be taught (a model pelvis may help) and the risks of pelvic floor dysfunction explained, especially urinary incontinence in pregnancy and after childbirth (Box 16.2).

Box 16.2 Instructions for teaching the pelvic floor muscle exercise

Abdominal exercises

The deepest layer of muscles within the abdominal corset, TrA is important in postural control, controlling the neutral spine position and giving support to the weight of the growing baby. By its attachment to the aponeurosis, rectus sheath and linea alba, it may help to limit DRAM.

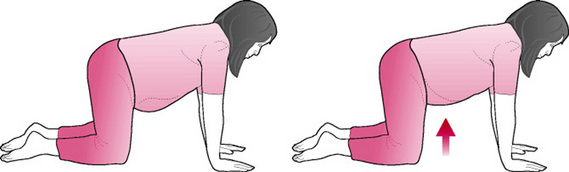

The mother should adopt a pain-free position, with good postural alignment. Sitting, standing, side-lying or four-point kneeling are good positions but she should avoid lying on her back after 16 weeks of pregnancy, because of the risk of supine hypotension. Figure 16.10 illustrates the transversus exercise, and Boxes 16.3 and 16.4 provide instructions for pelvic tilting and the TrA exercise.

Coping with common problems in pregnancy (see also Ch. 14)

Leg cramps

Leg cramps are common and it can disturb sleep. Inadequate fluid intake, inactivity, prolonged sitting or wearing high heeled shoes may make the symptoms worse.

Advice: take a gentle walk, do foot and ankle circling, and gently stretch out the calf muscles. Have a warm bath before going to bed, and drink plenty of liquid.

Swollen ankles and varicose veins

Varicose veins are swollen, twisted, painful veins that have filled with an abnormal collection of blood. Prolonged standing and increased pressure within the abdomen may increase susceptibility to the development of varicose veins or aggravate the condition. Painless swelling of the feet and ankles is also a common problem.

Advice: rest with feet in elevation, take gentle exercise, avoid standing for long periods and consider wearing support tights.

Carpal tunnel syndrome

Fluid retention causing pressure on the median nerve within the carpal tunnel at the wrist may cause swelling, numbness, tingling or pain in the hands and fingers.

Advice: avoid repetitive movements, keep the hands cool and, if not resolving, refer to a women’s health physiotherapist.

Postnatal

Rest

Adequate rest for the new mother is essential immediately after birth. The health professional may be able to suggest positions of ease in side-lying, with pillows under the abdomen and between the knees, or lying on the back with a soft pillow under the knees. If the new mother has learned a relaxation technique, she should use it to help her rest.

Getting in and out of bed

Rolling over and getting out of bed is easiest if she bends her knees, one at a time, supports her abdomen with a hand, especially if she has had a caesarean section draws in the low tummy muscles and rolls knees, hips and shoulders all over as one onto the side.

To get out of bed, push the body up by pressing down onto the mattress and allowing the feet to drop down to the floor. Sit for a few moments before standing by pushing up with both hands and standing tall.

Sitting and feeding

Posture when feeding is important to protect the back. Aim for a pain-free, neutral spine posture and if sitting, use adequate pillows to lift baby to the breast or bottle, so that the mother’s back is supported and shoulders relaxed.

Pelvic floor exercises and pelvic floor care

The pelvic floor muscles have been under strain during pregnancy and stretched during birth and it may be both difficult and painful to contract these muscles postnatally. Mothers should be encouraged to try the exercise as often as possible in order to regain full bladder control, prevent incontinence and prolapse and ensure normal sexual satisfaction for both partners in the future.

Studies have shown that women who had instruction by the physiotherapist on the postnatal ward and had been compliant with the exercises had reduced incidence of stress incontinence up to 1 year postnatally (Morkved & Bo 2003).

Pelvic floor exercise advice

Start exercises as soon after birth as possible, but if a urinary catheter is in place, wait until it is removed.

Try drawing in the muscles in varying positions; if the area is painful, side-lying is probably the most comfortable. If the area is painful and swollen, gentle rhythmical tightening and relaxing of the muscles will ease discomfort and promote healing.

Once the mother is more comfortable she should exercise the muscles as in the antenatal section, aiming to continue with a regular exercise regime for several months.

Other advice

Women should inform the midwife if they have not passed urine within 6 hrs of birth. It is the responsibility of the midwife to ensure local post-birth voiding protocols are adhered to and perinatal continence risk assessments completed, action taken as indicated and that any urinary incontinence is noted.

Empty the bladder regularly in first day or two after birth, but do not get into the habit of going to the toilet ‘just in case’. Do not stop then start the flow of urine. Drink plenty of water for a healthy bladder, especially if breastfeeding.

When having a bowel movement, it may help to support the perineum with a pad or a hand on the abdomen if a caesarean section has been performed.

3rd and 4th degree tears

Faecal incontinence affects approximately 10% of female adults, with anal sphincter laceration during childbirth being the major risk factor, and accountable for 45% of incidence of postnatal faecal incontinence.

Following 3rd or 4th degree tears, 13% of primiparae and 23% of multiparae have on-going symptoms of urgency and/or faecal incontinence 3 months after birth (Sultan 1993).

All 3rd and 4th degree tears should be documented and a local care plan put in place to manage and review these women. A multidisciplinary team approach for these women is essential as pain management, advice regarding hygiene and care should be given postnatally and women should be advised about diet and position of defaecation to protect the anal sphincter. Compliance with the pelvic floor exercise programme is essential.

Faecal incontinence may also be caused by damage to the pelvic and pudendal nerves during vaginal birth and subsequent weakness of the pelvic floor and anal sphincter (Allen et al 1990).

It is a distressing and disabling condition, especially for new mothers but MacArthur et al (1997) found that only 14% of women with new faecal incontinence after childbirth had consulted a doctor and those doing so were unlikely to report incontinence voluntarily as one of their symptoms.

All postnatal women should be encouraged to exercise the pelvic floor and be asked about bladder and bowel function.

Abdominal exercises

The abdominal muscles become stretched and weakened by pregnancy. It is advisable to begin abdominal exercises to regain tone as soon as possible after birth in order that they recover to support the spine, prevent and relieve back pain and help the mother regain her ‘former figure’.

Pelvic tilting as described in the antenatal section helps to locate the neutral spine position and also assists the relief of wind and nausea following caesarean section.

The TrA exercise

It is important to begin by exercising the deepest layer of muscles, the TrA, as described in the antenatal section.

The woman may now practise this exercise lying down with knees bent up and feet comfortably flat on the bed, with just one pillow beneath her head and arms by her side and in neutral spine position. This position is termed crook-lying. She should be advised to progress to exercising the muscle when sitting and standing, aiming for 10, 10 secs holds, three times a day and also to draw in the lower tummy when lifting, or bending forward to dress and change baby. This can be progressed further by trying the above exercise in four-point kneeling if comfortable. Women who have had a caesarean section should wait until this position is comfortable.

Progressing further

If, when trying the following exercise, abdominal doming occurs, the woman should revert to just the TrA exercise. If the doming persists after a few days, this may indicate that the rectus muscle has separated and the linea alba overstretched as in DRAM (Fig. 16.11). Contact should be made with the women’s health physiotherapist who will advise on safe abdominal exercises and back-care.

Knee bends

In crook-lying, draw in the lower tummy, keeping the back still and bend one hip and knee up as far as is comfortable. Hold for 10 secs and slowly lower. Breathe easily throughout. Repeat, with the other leg. If able, repeat another three times for each side. This is a more challenging exercise for the abdominal corset and requires control by the oblique muscles to prevent trunk rotation.

Knee rolling

In crook-lying with lower tummy drawn in, gently lower both knees to the right as far as is comfortable, bring them back to the middle and relax, breathing easily throughout. Draw in the lower tummy and repeat to the other side. Repeat three times to each side.

Head lifts

This is not advisable for anyone who has neck pain.

In crook-lying, take a gentle breath in, then after the breath out, draw in the lower tummy and the pelvic floor muscles and lift head from the pillow, hold for 3 secs, lower and relax. Repeat up to 10 times. Progress by lifting the head and shoulders simultaneously.

Women should be advised to aim to practise abdominal exercises three times a day for at least 3 months after childbirth.

Care of the back after the birth

It may take up to 6 months before the ligaments completely resume their normal functions (Polden & Mantle 1992), so it is vital that new mothers receive advice on back-care in relation to everyday activities.

The mother should sit well supported to feed the baby. To prevent the mother from slouching forward, the baby should rest raised up on pillows. Nappy changing and bathing are best carried out on a surface at waist level or with the mother kneeling at a surface of coffee-table height.

Lifting anything heavier than the baby for the first 6 weeks should be avoided if at all possible but if unavoidable, good advice is:

Baby chairs are heavy and are best carried by holding underneath and close to the body instead of by the carrying handle which puts a strain on one side of the body. Whenever possible, the chair should be carried empty and placed in the position required before the baby is put in it.

Baby slings should be comfortable and not cause an arched back. The weight should be well supported and the mother should use her TrA and pelvic floor muscles to ensure a good posture and prevent backache.

If back or pelvic girdle pain persists postnatally then referral to the women’s health physiotherapist is indicated.

When/what to refer to the physiotherapist

Physiotherapists can advise on, or treat, the following conditions.

Promoting health and fitness

Opportunities for liaising with and sharing good practice with other health professionals to develop both specific and general health care measures should never be missed. Physiotherapists, midwives and health visitors have a duty of care to promote health and fitness to women and this may be possible in a variety of settings.

During pregnancy, labour and the puerperium, midwives and other healthcare professionals have many opportunities to influence parents-to-be, incorporating a sensible approach to exercise within the broader sphere of healthy routines for all family members. Walking, cycling, swimming and other forms of exercise should be encouraged as part of a general lifestyle as well as learning relaxation techniques as appropriate. Specific exercises for strengthening the pelvic floor and abdominal muscles, especially TrA, will have relevance far beyond the months of child bearing. Parents-to-be are an extremely receptive audience so opportunities to develop and promote specific and general healthcare measures should be optimized. Health professionals are well placed to encourage all women and their families to continue exercising for life.

ACOG. Exercise during pregnancy and the post partum period: Committee Opinion. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2002;99:171-173.

Allen RE, Hosker GL, Smith ARB, et al. Pelvic floor damage and childbirth: a neurophysiological study. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1990;97:770-779.

Arena B, Maffulli N. Exercise in pregnancy: how safe is it? Sports Medicine and Arthroscopy Review. 2002;10(1):15-22.

Artal R, O’Toole M, White S. Guidelines of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists for exercises during pregnancy and the postpartum period. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2003;37:6-12.

Ashton-Miller JA, Howard D, Delancey JOL. The functional anatomy of the female pelvic floor and stress continence control system. Scandinavian Journal of Urology and Nephrology. 2001;207:S1-S7. S106–S125

Avery ND, Stocking KD, Tranmer JE, et al. Fetal responses to maternal strength conditioning exercises in late gestation. Canadian Journal of Applied Physiology. 1999;24(4):362-376.

Beilock SL, Feltz DL, Pivarnik JM. Training patterns of athletes during pregnancy and postpartum. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport. 2001;17(1):39-46.

Brown W. The benefits of physical activity during pregnancy. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport. 2002;5(1):37-45.

Bungum TJ, Peaslee DL, Jackson AW, et al. Exercise during pregnancy and type of birth in nulliparae. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic and Neonatal Nursing. 2000;29(3):258-264.

Bush A. Cardiopulmonary effects of pregnancy and labour. Journal of the Association of Chartered Physiotherapists in Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1992;71:3-4.

Caldeyro-Barcia R. The influence of maternal bearing-down efforts during second stage on fetal well-being. Birth and Family Journal. 1979;6:17-22.

DeLancey JOL. Structural support of the urethra as it relates to stress urinary incontinence: the hammock hypothesis. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1994;170(6):1713.

DeLancey JOL, Kearney R, Chou Q, et al. The appearance of levator ani muscle abnormalities in magnetic resonance images after vaginal birth. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2003;101:46-53.

Enkin M, Keirse MJNC, Neilson J, et al. A guide to effective care in pregnancy and childbirth, 3rd edn. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000.

Friedman EH. Neurobiology of infants born to women who exercise regularly throughout pregnancy. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1999;181(4):1038-1039.

Fry D. Symphysis pubis dysfunction guidelines ACPWH. Physiotherapy. 1997;83(1):41-42.

Goodwin A, Astbury J, McMeeken J. Body image and psychological well being in pregnancy. A comparison of exercisers and non-exercisers. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2000;40(4):442-447.

Gupta JK, Nikodem C. Maternal posture in labour. European Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproductive Biology. 2001;92(2):273-277.

Hartmann S, Bung P. Physical exercise during pregnancy – physiological considerations and recommendations (review). Journal of Perinatal Medicine. 1999;27(3):204-215.

Haslam J, Laycock J. Therapeutic management of incontinence and pelvic pain, 2nd edn. London: Springer, 2008.

Hefferman AE. Exercise and pregnancy in primary care. Nurse Practitioner. 2000;25(3):42. 49, 53–56

Horns PN, Ratcliffe LP, Leggett JC, et al. Pregnancy outcomes among active and sedentary primiparous women. Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Neonatal Nursing. 1996;25(1):49-54.

Jackson. Pilates in pregnancy DVD, with Lindsey Jackson. Enhance Wellbeing. 2001. Online. Available lj.enhance@btinternet.com.

Koltyn KF, Schultes SS. Psychological effects of an aerobic exercise session and a rest session following pregnancy. Journal of Sports Medicine and Physical Fitness. 1997;37:287-291.

Kramer MS. Regular aerobic exercise during pregnancy Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Issue 2:CD000180, 2000.

Mason L, Glenn S, Walton I. The relationship between antenatal pelvic floor muscle exercises and post partum stress incontinence. Physiotherapy. 2001;87(12):651-661.

MacArthur C, Bick D, Keighly MR. Faecal incontinence after childbirth. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1997;104:46-50.

Marquez-Sterling S, Perry AC, Kaplan TA, et al. Physical and psychological changes with vigorous exercise in sedentary primigravidae. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 2000;32(1):58-62.

McMurray RG, Berry MJ, Katz VL. The beta-endorphin responses of pregnant women during aerobic exercise in water. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 1990;22(3):298-303.

MacLennan AH, Taylor AW, Wison DH, et al. The prevalence of pelvic floor disorders and their relationship to gender, age, parity and mode of birth. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2000;107(12):1460-1470.

MIDIRS. Positions in labour and birth, 2003. Informed Choice for Professionals, Leaflet 5

Morkved S, Bø K. Pelvic floor muscle training during pregnancy to prevent urinary incontinence: a single-blind randomised controlled trial. Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2003;101(2):313-319.

NICE. NICE Guidelines: antenatal care – routine care for the healthy pregnant woman, CG62. London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2008.

NICE. NICE Guidelines: urinary incontinence, CG40. London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2006.

Noble BJ, Borg GA, Jacobs I, et al. A category-ratio perceived exertion scale: Relationships to blood and muscle lactates and heart rate. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 1983;15(6):523-528.

Ostgaard HC. Lumbar back and posterior pelvic pain in pregnancy. In: Vleeming A, Mooney V, Dorman T, et al, editors. Movement, stability and low back pain. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1997:411-420.

Panjabi M. The stabilizing system of the spine. Part I: function, dysfunction, adaptation, and enhancement. Journal of Spinal Disorders. 1992;5(4):383.

Panjabi M. the stabilizing system of the spine. Part II. Neutral zone and instability hypothesis. Journal of Spinal Disorders. 1992;5(4):390.

Polden M, Mantle J. Physiotherapy in obstetrics and gynaecology. Oxford: Butterworth and Heinemann, 1992.

Pool-Goudzwaard AL, Slieker Ten Hove MCP, Vierhout ME, et al. Relations between pregnancy related low back pain, pelvic floor activity and pelvic floor dysfunction. International Journal of Urogynecology. 2005;16(6):468-474.

RCOG. Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists setting standards to improve women’s health. Standard No. 4, January 2006, 2006.

Reilly ETC, Freeman RM, Waterfield MR, et al. Prevention of postpartum stress incontinence in primigravidae with increased bladder neck mobility: a randomised controlled trial of antenatal pelvic floor exercises. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2002;109(1):68-76.

Riemann MK, Kanstrup Hansen IL. Effects on the fetus of exercise in pregnancy. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine and Science in Sports. 2000;10(1):12-19.

Roberts JE, Mendez-Bauer C, Wodell DA. The effects of maternal position on uterine contractility and efficiency. Birth. 1983;10:243-249.

Sangalli MR, Curtin F, Morabia A, et al. Prevalence of anal incontinence and other anorectal symptoms in women. International Urogynaecology Journal. 2001;12(2):117-121.

SMA. Sports Medicine Australia Statement: the benefits and risks of exercise during pregnancy. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sports. 2002;5:11-19.

Sultan AH. Anal sphincter disruption during vaginal birth. New England Journal of Medicine. 1993;329:1905-1911.

Tetzschner T, Sørensen M, Lose G, et al. Pudendal nerve recovery after a non-instrumented vaginal delivery. International Urogynecology Journal and Pelvic Floor Dysfunction. 1996;7(2):102-104.

Warren MP, Shantha S. The female athlete. Best Practice and Research in Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2000;14(1):37-53.

Wu WH, Meijer OG, Uegaki K, et al. Pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain. Terminology and prevalence. European Spine Journal. 2004;13(7):575-589.

Leaflets produced by the Association of Chartered Physiotherapists in Women’s Health (ACPWH) (www.acpwh.org.uk):