Substance Abuse

Although experimentation with alcohol and other drugs during adolescence is fairly common, the majority of teens do not become high-risk users. National and statewide surveys indicate that although more than half of adolescents will have tried tobacco, alcohol, and marijuana before they are out of their teens, fewer than one adolescent in eight has tried illicit stimulants and inhalants; fewer than 1 in 10 has ever tried “hard” drugs such as hallucinogens, sedatives, or crack cocaine; and a tiny percentage use injection drugs such as heroin. Adolescents at greatest risk are not the majority of high school students who have tried alcohol or marijuana, but rather the estimated 2% to 4% who report daily use of alcohol or marijuana during the past 30 days; the 5% to 10% who used narcotics like oxycodone (OxyContin) in the past year; and the 1% or so who report using illicit drugs such as crystal methamphetamine, heroin, crack cocaine, or 3-4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA, or Ecstasy) at least once in the past month (Johnston, O’Malley, Bachman, et al, 2008).

The etiology of substance abuse is not completely understood. Current research focuses on biopsychosocial risk and protective factors, but some emerging research has begun to explore genetics and physiologic mechanisms. For the majority of adolescents, experimentation with drugs occurs during a period in which they are trying out a variety of behaviors and then discarding them when the fit is not right. There are a number of theories about pathways leading to the abuse of substances. Research has identified risk factors such as the presence of an enzyme (aldehyde dehydrogenase [ALDH]) that makes decomposition of ethanol in the body possible (Patton, 1995), family history of drug abuse and dependence (Baer, Barr, Brookstein, et al, 1998; Kosterman, Hawkins, Guo, et al, 2000), a history of child maltreatment or other traumas affecting the biologic stress response systems (De Bellis, 2002), and genetic inheritance and individual psychopathology (Carlson, Iacono, and McGue, 2002; Angold, Costello, and Erkanli, 1999). However, no single factor explains the cause of adolescent substance abuse. The enormous impact of poverty and ready availability of substances, combined with biogenetic predispositions for abuse, are likely factors to consider in understanding the cause. Although there is much to learn about what leads an adolescent to abuse substances, most experts agree with a diathesis-stress model, which presumes a biologic predisposition accompanied by psychosocial risk factors.

An adolescent abusing alcohol or other drugs often does so as a means of coping with depression, anxiety, restlessness, or chronic feelings of boredom or emptiness (Harrison, Fulkerson, and Beebe, 1997). Because denial is often associated with substance abuse, nurses, other health care professionals, and parents may not be aware of the abuse problem.

Definitions

Considerable misinformation and confusion are related to the terms applied to substance use and substance abuse. The most important differences among these terms are the distinctions between voluntary and involuntary behavior and between culturally defined and physiologically identified events. Drug abuse, misuse, and addiction are all culturally defined terms and are voluntary behaviors. Drug tolerance and physical dependence are involuntary physiologic responses to the pharmacologic characteristics of drugs, such as opioids and alcohol. Consequently, an individual can be “addicted” to a narcotic with or without being physically dependent, and a person may be physically dependent on a narcotic without being addicted (e.g., patients who use opioids to control pain).

The broad term drug abuse, which is often applied to all forms of drug misuse, is confusing and does not necessarily define the problem related to drug use. Many substances are controlled by law and involve severe penalties for any illegal use. Others are sanctioned from a legal, social, and medical standpoint, but their excessive use may cause physical or social problems for the adolescent. Problems concerning drug use are defined as follows:

Legal—The drug being taken is strictly controlled by law and is accompanied by severe penalties for its use or possession.

Social—Use of a substance leads to disruptive or bizarre behavior that alienates the user from the rest of society; this results in a social problem.

Medical—Current or continued use of a substance may adversely affect the adolescent’s physical or mental health.

Individual—This focuses on the role that drug use plays in the individual’s life and factors that contribute to the individual’s need for the drug.

Patterns of Drug Use

Many factors influence the extent to which teenagers use drugs. The type of drug used, mode of administration, duration of use, frequency of use, and single- or multiple-drug use must be considered in determining the severity of the individual drug problem. Most drug use begins with experimentation. The drug may be tried only once, may be used occasionally, or may become an integral part of a drug-centered lifestyle. Identification of the pattern of drug use in an individual facilitates the formulation of an approach to the problem. Patterns have been observed based on dose and frequency of use.

Adolescents who use drugs fall into two broad categories: experimenters and compulsive users. Between these groups on opposite ends of a continuum is a broad range of recreational users, principally of drugs such as marijuana, cocaine, alcohol, and prescription drugs. For many the goal is typically peer acceptance. These users fit more closely with the experimenting, intermittent users. For others the goal is intoxication or the sustained intense effects from using the particular drugs; these users resemble the compulsive users. They may engage in periodic heavy use, or binges. The groups of greatest concern to health care workers are those whose patterns of use involve high doses or mixed drugs with the danger of overdose or other harms that can occur when bingeing, and those compulsive users with the threat of dependence, withdrawal syndromes, and altered lifestyle.

Types of Drugs Abused

Any drug can be abused, and most are potentially harmful to adolescents still going through formative life experiences. Although rarely considered drugs by society, the chemically active substances most commonly used are the xanthines and theobromines contained in chocolate, tea, coffee, colas and energy drinks (of which caffeine is the most common). Ethyl alcohol and nicotine are others that, although recognized as drugs, are sanctioned by society for use by adults. Any of these substances can produce mild to moderate euphoric or stimulant effects and can lead to physical or psychologic dependence.

Many factors determine personal preferences for gratification. Many drugs are not harmful for all teenagers, and some, used intermittently, will probably not produce ill effects or result in dependence. Reactions vary according to the drug used, its purity, the user’s expectations, the route of administration, and the context in which the drug is used. These factors determine to a great extent whether the experience is pleasant or unpleasant. The type of drugs used also varies according to geographic location, socioeconomic status, urban versus suburban areas, and various historical periods.

A drug that is popular with one “generation” of adolescents may not be attractive to another. Changing trends are influenced by the adolescent’s search for new and different experiences, as well as availability, costs, and perceived risks. Since 2000, declines have occurred in teenagers’ use of most drugs, including alcohol, tobacco, marijuana, and drugs that had seen sharp increases between 1998 and 2001, such as MDMA (Johnston, O’Malley, Bachman, et al, 2008). The level of drug use among teens in the United States still creates a number of potential health risks; ongoing concerns include the use of alcohol, marijuana, tobacco, MDMA, inhalants, prescription drugs, and cocaine.

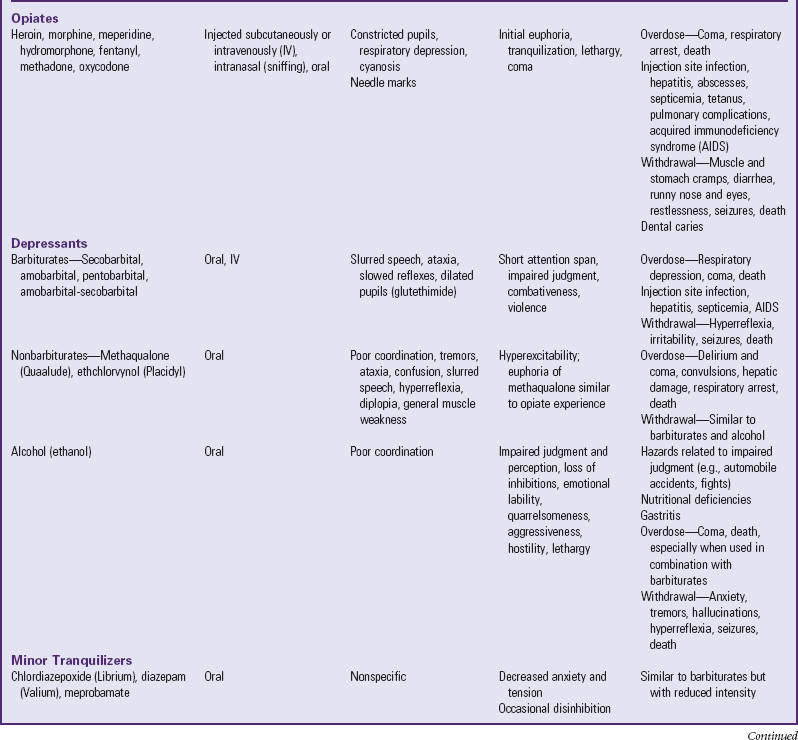

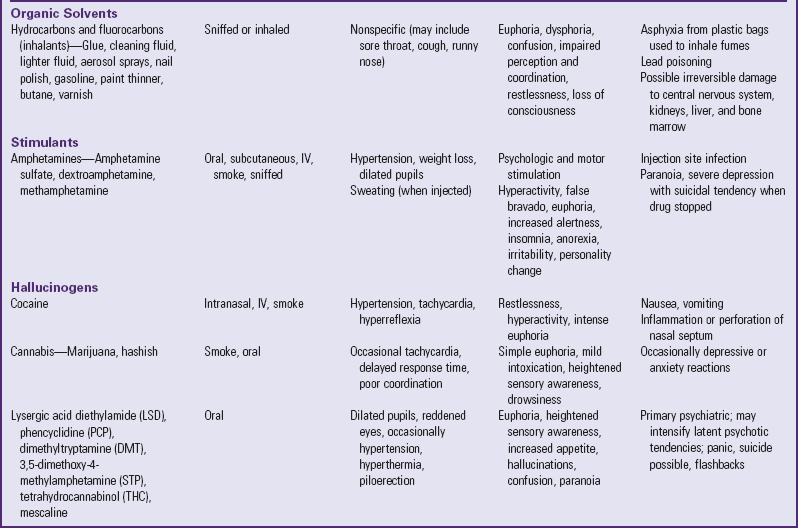

Drugs with mind-altering capacity that are available on the black market and are of medical and legal concern are the hallucinogenic, narcotic, hypnotic, and stimulant drugs. In addition, health care professionals are concerned about the use of various volatile substances such as gasoline, model airplane cement, and organic solvents such as butane. These substances are inhaled by the user to achieve an altered sensation, and the most recent surveillance has indicated only a slight decline in use, after a modest increase in use starting in 2003 (Johnston, O’Malley, Bachman, et al, 2008). More recently, abuse of prescription drugs such as oxycodone and methylphenidate has received added attention. Drugs available on the street are often mixed with other compounds and fillers so that the purity of the drug, its strength, and the nature of the additives are highly variable. Table 21-2 outlines some of the more commonly abused substances and their general manifestations.

Tobacco

![]() Cigarette smoking has continued to decline since the late 1990s, dropping by more than half in the decade between 1996 and 2007 (Johnston, O’Malley, Bachman, et al, 2008). These declines are due in part to increased costs for cigarettes because of added taxes, changes in community attitudes about smoking and laws restricting smoking in public places, and increased antismoking advertising as a result of the government lawsuits against tobacco companies. In 2007, 7.1% of eighth grade teens reported smoking once or more in the past 30 days, whereas 21.6% of twelfth graders did so. Daily smoking is less common, with 4.4% of eighth graders and 15.6% of twelfth graders reporting smoking at least one cigarette daily in the past month. African-American youth are less likely to smoke than Hispanic or Caucasian adolescents.

Cigarette smoking has continued to decline since the late 1990s, dropping by more than half in the decade between 1996 and 2007 (Johnston, O’Malley, Bachman, et al, 2008). These declines are due in part to increased costs for cigarettes because of added taxes, changes in community attitudes about smoking and laws restricting smoking in public places, and increased antismoking advertising as a result of the government lawsuits against tobacco companies. In 2007, 7.1% of eighth grade teens reported smoking once or more in the past 30 days, whereas 21.6% of twelfth graders did so. Daily smoking is less common, with 4.4% of eighth graders and 15.6% of twelfth graders reporting smoking at least one cigarette daily in the past month. African-American youth are less likely to smoke than Hispanic or Caucasian adolescents.

Although the number of adult and adolescent smokers has declined in recent years, cigarette smoking is still considered the chief avoidable cause of death. The hazards of smoking at any age are undisputed. However, a preventive approach to teenage smoking is especially important. Because of its addictive nature, smoking begun in childhood and adolescence can result in a lifetime habit, with increased morbidity and early mortality. Smoking in adolescence has also been related to other risk behaviors for weight management, including vomiting after meals and use of amphetamines (Parkes, Saewyc, Cox, et al, 2008). Smoking has also been associated with marijuana use, multiple sexual partners, and binge drinking (Escobedo, Reddy, and DuRant, 1997).

Etiology

Teenagers begin smoking for a variety of reasons. Factors related to the onset of smoking can be categorized as social, sociodemographic, psychosocial, and biologic. Once smoking behavior is established, smoking itself produces enough reinforcement to sustain the practice without the initial pressure.

Social Factors: Social pressures to smoke include imitation of the smoking behavior and attitudes of parents and other adults. The association of smoking with maturity or mature behavior; pressures from peers who view smoking as the popular thing to do; and the use of smoking as an outlet for school, social, or home pressures are also factors. Other pressures come from advertisements aimed directly at teens, although the United States has limited such advertisements in recent years.

Previous research has indicated some parental influence on tobacco use in children; that is, adolescents who smoke are more likely to have parents who smoke (Institute of Medicine, 1994). Parental disapproval of smoking may influence adolescents not to smoke (Sargent and Dalton, 2001), but only if the parents themselves do not smoke (Chassin, Presson, and Sherman, 2005). Parenting style may also play a role. In the study by Chassin, Presson, and Sherman, teens with parents who were warm and accepting but also regularly monitored their teens’ behavior, with consistent rules and discipline—the authoritarian style of parenting—were significantly less likely to start smoking than teens whose parents were disengaged (low monitoring, but also low levels of acceptance and attention). In their study, general parenting style had more overall influence than parental attitudes and antismoking messages, especially if the parents smoked. This makes sense, since teens will notice the “do as I say, not as I do” discrepancy between parents’ behaviors and their words.

The influence of peers or friends on smoking initiation has been documented in several studies (Bertrand and Abernathy, 1993; Flay, Hu, Siddiqui, et al, 1994). In particular, the effects of friends’ smoking have been found to be greater for females than for males, leading to greater peer pressure for young girls to start smoking (Hu, Flak, Hedeker, et al, 1995).

The mass media have contributed to the initiation of smoking in adolescents. In advertisements smokers are engaged in activities and dressed in clothes suitable for adolescents, and smoking is associated with fun, risk taking, sexual adventure, maturity, and autonomy. The ads also imply an association between smoking and youthful vigor; a slim figure; good looks; and personal, social, and professional acceptance and success. The number of major actors who smoke cigarettes in movies and television shows also appears to influence smoking behavior in teens.

Some uses of the media have been helpful in increasing adolescent exposure to antismoking messages. Mass media antismoking campaigns in general have been effective. However, tobacco companies have funded and developed smoking prevention advertising that has had opposite effects on smoking-related beliefs and intentions of adolescents (Wakefield, Terry-McElrath, Emery, et al, 2006).

Sociodemographic Factors: Sociodemographic factors that relate to levels of smoking include socioeconomic status, gender, sexual orientation, history of trauma, and performance in school. A consistent, negative association has been observed between socioeconomic status and smoking (especially among boys), and there is a positive correlation between low academic goals and performance and smoking. Gay, lesbian, and bisexual adolescents are more likely to smoke than their heterosexual peers (Austin, Ziyadeh, Fisher, et al, 2004), possibly as a way of coping with unique stressors of stigmatization, rejection, and violence from family, school, and community (D’Augelli, 2004). Similarly, youth who report a history of physical or sexual abuse are more likely to smoke (Al Mamun, Alati, O’Callaghan, et al, 2007). Rates of smoking are highest among homeless and street-involved youth, as well as adolescents who did not complete high school. Students who focus on schoolwork and who have high educational goals for themselves are significantly less likely than their peers to develop a long-term smoking habit.

Psychosocial Factors: Although theories explaining the relationship between personality and smoking behavior have been suggested, research has not documented any significant differences between adolescents who smoke and those who do not smoke. Rather than enabling us to discriminate between likely smokers and nonsmokers, personality traits such as anxiety have been shown to predict how much adolescents will smoke once they begin the habit. Although depression does not seem to be related to heavy cigarette smoking in adolescents, current use is a determinant in the development of depressive symptoms (Goodman and Capitman, 2000).

Research has examined the development of different personality characteristics of adolescents at the time of the onset of tobacco use and with continued use. Youthful smokers (seventh grade) have been found to be extroverted and involved with their peers, whereas older smokers are often depressed and withdrawn (Stein, Newcomb, and Bentler, 1996). This research supports the hypothesis that smoking takes on different psychosocial meanings with continued use.

Biologic Factors: Studies have begun to identify the genetic predispositions for tobacco use and to try to explain the complex interplay of genetics, environment, and behavior that can lead to smoking. For example, youth with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) are twice as likely to smoke cigarettes as their peers, to start at younger ages, and to smoke more regularly and in greater amounts (Laucht, Hohm, Esser, et al, 2007). However, the main component of this increased risk is from the influence of substance-using peers, with some small contribution of genetics.

Biologic factors serve both to encourage and to deter further experimentation by would-be smokers. The initial harshness, nausea, and irritation may influence many youngsters not to try smoking again. For others, however, such symptoms are a challenge to overcome.

Smoking has been found to lower endurance by decreasing breathing capacity or ventilatory muscle endurance. Cigarette smoking is also associated with mild airway obstruction and slowed growth of lung function in adolescents. The detrimental effects of smoking on growth of lung function may be more pronounced in adolescent girls. Cigarette smoking showed a dose-response relationship with the development of sleep problems in a group of more than 3000 adolescents (Patten, Choi, Gillin, et al, 2000).

Dependence is a result of nicotine, the primary alkaloid in tobacco. Nicotine exerts both stimulating and sedating effects on the central and peripheral nervous systems and on several organ systems. Attempts to stop smoking are accompanied by severe craving and withdrawal symptoms.

Process of Becoming a Smoker

The process of becoming a smoker involves three stages: initiation (trying the first cigarette), experimental smoking (less than weekly), and regular smoking (at least weekly). Some researchers also recognize a preparation stage in which psychosocial, environmental, and possibly biologic factors prepare some youngsters to be smokers. Regardless of reason, the fact remains that 75% of teenage smokers will smoke regularly as adults (Moolchan, Ernst, and Henningfield, 2000), in part because of the addictive nature of nicotine in the tobacco (Chassin, Presson, and Sherman, 2005).

Smokeless Tobacco

The term smokeless tobacco refers to tobacco products that are placed in the mouth or inhaled through the nose but not ignited (e.g., snuff and chewing tobacco). This substitute for cigarettes continues to pose a hazard to adolescents, although use has declined by about 50% since the peak prevalence in 1995, with only 15.1% of teens in 2007 having tried smokeless tobacco by the twelfth grade (Johnston, O’Malley, Bachman, et al, 2008). Although a much smaller percent reported using smokeless tobacco in the past month (6.6%), nearly half of them reported using it daily (2.8%). More boys (13.4%) than girls (2.3%) in 2007 used smokeless tobacco within the past 30 days, and Caucasian males were far more likely to use smokeless tobacco (18.0%) than African-American males (2.0%) or Hispanic males (6.7%) (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2008). Many children and adolescents believe that smokeless tobacco is a safe alternative to cigarette smoking and is not addictive, and they believe they can stop using it at any time. However, the number of adolescents who identify it as a health risk has increased since the mid-1990s, with nearly half now agreeing it has health risks (Johnston, O’Malley, Bachman, et al, 2008). These products have also been proved to be carcinogenic, and regular use can cause dental problems, foul-smelling breath, and tooth erosion or loss.

Nursing Care Management

Prevention of regular smoking in teenagers is the most effective way to reduce the overall incidence of smoking. A variety of methods have been employed. Posters, charts, displays, statistics, and the use of examples of actual damaged lungs to communicate the hazards of smoking all have their supporters and doubters. Some schools also use films and demonstrations in science classes.

For the most part, smoking-prevention programs that focus on the negative, long-term effects of smoking on health, such as lung cancer and heart disease, have been ineffective. Youth-to-youth programs and those emphasizing the immediate effects are more effective, but primarily in improving the teenagers’ attitudes toward not smoking. Because smoking and smoking-related behaviors are social symbols, antismoking campaigns must address the norms of potential smokers. Anything that ridicules or threatens the social norms of the peer group can be unproductive or counterproductive. Investigators have found that teaching resistance to peer pressure to smoke is effective in early adolescence. Although the effects of these programs may decrease with time, the effects can be enhanced in older adolescents by using a curriculum instead of simply handing out written material to the students (Adelman, Duggan, Hauptman, et al, 2001).

Two areas of focus for antismoking programs are peer-led programs and use of media in smoking prevention (e.g., videotapes and films). Peer-led programs emphasizing the social consequences of smoking have proved most successful. If a significant number of influential peers can “sell” their classmates on the idea that the habit is not popular, the followers will imitate their behavior. Such programs emphasize short-term rather than long-term consequences (e.g., the effects of smoking on personal appearance, such as unattractive stains on teeth and hands and unpleasant odor of breath and clothing, as well as lower sperm counts in young males).

The impact of school-based antismoking programs can be strengthened by expanding these programs to include parents, mass media, youth groups, and community organizations. For example, mass media efforts that involve antismoking radio campaigns have been identified as the most cost-effective mass media intervention. Many public schools have used the American Lung Association’s smoking cessation program Not-on-Tobacco (NOT; www.notontobacco.com) with modest results (Horn, Dino, Kaselkar, et al, 2004).

Smoking bans in schools also accomplish several goals: (1) they discourage students from starting to smoke, (2) they reinforce knowledge of the health hazards of cigarette smoking and exposure to environmental tobacco smoke, and (3) they promote a smoke-free environment as the norm.

Alcohol

Acute or chronic misuse of alcohol (ethanol), a socially accepted depressant, is responsible for many acts of violence, suicide, accidental injury, and death. Ethanol reduces inhibitions against risky behaviors, aggression, and sexual behavior; it slows reflexes and impairs judgment in driving and other activities that require skill to avoid injury. Abrupt withdrawal is accompanied by severe physical and psychologic symptoms, and long-term use leads to slow tissue destruction, especially of the brain and liver cells.

Teenage drinking is not a new phenomenon. Because of its social acceptance, peer pressure, and easy accessibility, alcohol is the drug of choice for many adolescents. It is the most widely accepted drug, can be purchased legally by adults, and is relatively inexpensive. It is often part of a meal (wine, beer), approved by adults throughout the world when used in moderation, and is even promoted as a health benefit under certain circumstances. Young people may not even consider it a drug. Many have been exposed to alcohol all their lives.

Although there are racial, ethnic, and gender differences, the pattern of frequent, heavy drinking among those who will develop this pattern is likely to begin in high school. Drinking increases with age. By age 18 years, 85% of all adolescents have used alcohol. In 2007 the monthly prevalence of alcohol use was 54.9% among high school seniors, with 36.5% of these youths reporting episodic heavy drinking (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2008). The rates of ever using alcohol, as well as daily use, have declined over the past several years, and so has binge drinking (Johnston, O’Malley, Bachman, et al, 2008).

Although the majority of adolescents who experiment with alcohol do not become heavy users, social drinking remains a great concern, primarily because of the troubling rates of morbidity and mortality related to drinking. Alcohol-related motor vehicle accidents are the leading cause of unintentional injury and death among adolescents (Mulye, Park, Nelson, et al, 2009). About one in three adolescents reports being a passenger in a vehicle with a driver who had been drinking, and just over 10% acknowledge drinking and driving.

The most noticeable effects of alcohol occur within the central nervous system and include changes in cognitive and autonomic functions such as judgment, memory, and learning ability. Marked mood changes are characteristic of adolescent drinkers, who are described as hard to live with and unable to make up their minds. They can be identified by the way in which they use alcohol. Adolescent alcoholics often drink alone; cannot predictably control their use of alcohol; and protect their supply, afraid that they will be caught without anything to drink.

Adolescents who misuse alcohol often rely on it as a defense against depression, anxiety, fear, and anger. They become increasingly tolerant and need to drink more to experience the same effects. Some abusers have difficulty remembering things done while intoxicated and often intend to swear off the drug or cut down on its use. Not all these characteristics are observed in the alcoholic, but if several of the signs are evident, individuals should be considered at risk and detoxification therapy should be initiated.

Answers to questions and information about alcohol can be obtained by calling the Alcohol Hotline (800-ALCOHOL). Several support groups such as Al-Anon, Ala-Teen, and Ala-Tot also help children and families who have an alcoholic family member. Information about these groups can be obtained from Alcoholics Anonymous listings in local telephone directories.

Etiology

Social Factors: Parents, siblings, and peers have a significant impact on adolescent alcohol use. Adolescents who develop drinking problems tend to come from families with negative communication patterns, inconsistent parental discipline, marital discord, and an absence of parent-child closeness. Although family genetic influences have been identified for alcoholism and other substance abuse (Krueger, Hicks, Patrick, et al, 2002), parental and older sibling drinking practices and parental attitudes about alcohol also influence adolescent alcohol use, especially during early adolescence (Hoffmann and Su, 1998). Several studies assessing family structure have found a relationship between adolescent substance abuse and the over-involvement of one parent, accompanied by distancing from the other (see Family-Centered Care box).

Although the family environment may provide the kindling for adolescent alcohol abuse, peers provide the spark. An association with substance-using peers is the strongest predictor of an adolescent’s continued use (Hoffmann and Su, 1998). Peer association does not cause adolescent substance abuse, but in most cases adolescents who drink have friends who also drink, and young people whose friends would be upset if they got drunk are significantly less likely to drink or to binge drink (Smith, Stewart, Peled, et al, 2009). The impact of peers on drug use has been demonstrated among African-Americans, Asian Americans, and Hispanics.

Sociodemographic Factors: Frequency of alcohol use is influenced by several sociodemographic factors. Adolescents in different regions of the United States and across the world drink at different levels, often dependent on the general community acceptance of alcohol use. Girls and boys report a similar onset and course of experimentation with alcohol, although boys more often become heavy users. Homeless and street-involved youth report high levels of alcohol use, often starting at a very young age (Smith, Saewyc, Albert, et al, 2007). Gay, lesbian, and bisexual teens are at increased risk for alcohol use and problems associated with drinking (Marshall, Friedman, Stall, et al, 2008). A commitment to education reduces risk; in contrast, school failure is associated with alcohol abuse. School dropouts are at particularly high risk and have been shown to drink more than high school graduates. However, binge drinking is highest among college students.

Psychosocial Factors: Research on personality and alcohol abuse in adolescence has investigated the interplay of complex factors that determine risk for alcohol abuse. Although aggressiveness early in life predicts subsequent alcohol use, only one third of boys with aggressive behavior continue to be aggressive into adulthood (White, Brick, and Hansell, 1993). Children with hyperactivity, particularly when combined with conduct problems, are at risk for abuse of drugs, including alcohol. Personality traits associated with alcohol abuse include excessive and consistent rebelliousness and rejection of social norms.

In his research, Jessor (1991) examined several psychosocial factors and developed the Problem Behavior Theory for understanding adolescent drug and alcohol use. This theory identified several domains of psychosocial variation: the personality system, the perceived environmental system, the social system, and the behavior system. These systems are interrelated and constitute the risk of occurrence of problem behaviors. A common dimension within these systems that distinguishes drug users from nonusers is conventionality versus unconventionality. In reference to the personality system, for example, an adolescent who is disconnected from conventional institutions such as school or religious faith community is at greater risk for involvement with drugs and alcohol. Conversely, adolescents who embrace conventional values such as academic achievement and community involvement are less likely to engage in drug use.

Jessor (1991) also identified protective factors that enable at-risk adolescents to resist pressures to use drugs and alcohol. Protective factors can be defined as those personal attributes and environmental influences that buffer, neutralize, and interact with risk factors to prevent, limit, or reduce drug use. Protective factors do not imply the absence of risk but are viewed as distinctly different from risk factors (Scheier, Newcomb, and Skager, 1994). Protective factors include a caring and supportive family, peer models for conventional behavior, connectedness to school and community organizations, social support in the form of perceptions that adults outside the family care about the youth, and the availability of people to talk to about problems (Resnick, Bearman, Blum, et al, 1997; Smith, Stewart, Peled, et al, 2009). A host of studies since Jessor’s original model have modified and nuanced the list of assets and protective factors that reduce initiation of substance use, identifying protective factors specific to a diverse groups of adolescents (Oman, Vesley, Aspy, et al, 2004).

Biologic Factors: The interplay of personality, environment, and genetic factors influencing alcohol abuse has also come under scrutiny (Krueger, Hicks, Patrick, et al, 2002). Twin studies comparing the concordance of alcoholism in monozygotic and dizygotic twins indicate a significantly higher rate of concordance for alcoholism in monozygotic twins than in dizygotic twins (Morrison, Rogers, and Thomas, 1995). This finding holds true even if the twins were reared separately early in life. Other longitudinal population-based twin studies have explored the link between substance abuse and other externalizing behaviors such as conduct disorder or ADHD and have concluded that genetic inheritance determines about 80% of the likelihood of developing substance abuse in late adolescence and young adulthood, with the remainder of the risk in environmental influences of the family or community (Krueger, Hicks, Patrick, et al, 2002).

ALDH is an enzyme that assists with the breakdown of ethanol in the body. The absence of ALDH significantly reduces the likelihood that alcoholism will develop (Patton, 1995). Other genetic studies have indicated an association between the dopamine D2 receptor gene (DRD2) and alcoholism. This gene may confer susceptibility to at least one form of alcoholism (Blum, Noble, Sheridan, et al, 1990; Patton, 1995). Other studies of brainwave patterns and alcoholism or other substance abuse disorders among adolescents further support the genetic susceptibility findings (Carlson, Iacono, and McGue, 2002).

Research has also documented a relationship between early sexual maturation and alcohol use, smoking, and cannabis use, especially among adolescent girls (Patton and Viner, 2007). This association may be an external manifestation of the emotional reaction that occurs in girls who feel physically different because of early biologic maturation, or it may be due to altered patterns of sensation seeking or affiliations with older peers. However, research shows the link between early puberty and alcohol use may not continue into adulthood, as studies have found no association between early development and higher levels of adult substance use (Patton and Viner, 2007).

Additional Drugs

The majority of adolescents limit their experimentation with drugs to alcohol, tobacco, and marijuana (also called cannabis). A smaller proportion try other drugs that have serious consequences, including cocaine and other amphetamines, inhalants, barbiturates, narcotics, and hallucinogens. Approximately 15% of adolescents report using any illicit substance other than marijuana in the past year (Johnston, O’Malley, Bachman, et al, 2008), and the rates of use for most substances have been declining since the 1980s. Adolescent abuse of inhalants declined through the last half of the 1990s and the first few years of the new century, but in 2003 and 2004 lifetime prevalence of inhalant use increased slightly, one of the few drugs to increase, and then began to decline among eighth and twelfth graders (Johnston, O’Malley, Bachman, et al, 2008). Inhalant abuse is generally a “younger teen” drug, possibly because of its readier accessibility; up to 15.6% of eighth graders reported ever using inhalants in 2007, whereas only 10.5% of twelfth graders did (Johnston, O’Malley, Bachman, et al, 2008). Prescription drugs are another growing concern; in 2007, 2% of eighth graders and nearly 10% of twelfth graders reported using narcotics such as oxycodone and hydrocodone at least once in the past year; 2% to 4% reported using methylphenidate without a prescription. Although crystal methamphetamine (“crystal meth,” “ice”) has received a lot of media attention in the past several years, fewer than 2% of teens in any grade reported using it in the past year, and only 3% had used it by grade 12.

Drug users have developed a specialized terminology or slang for the substances they use. This vocabulary varies in different localities at different times, and new descriptive terms arise spontaneously wherever drugs are part of the environment. This can create challenges for nurses in assessing drug use.

Cocaine

Cocaine is the most potent antifatigue agent known. Although pharmacologically not a narcotic, it is legally categorized as such. Cocaine is available in two forms: (1) water-soluble cocaine hydrochloride administered by insufflation (snorting) and intravenous injection, and (2) a nonsoluble alkaloid (freebase) used primarily for smoking. Crack, or rock, is a purer and more problematic form of the drug; it can be produced cheaply and smoked in either water pipes, mentholated cigarettes, or specialized “crack pipes.” Cocaine taken by injection is associated with the highest levels of dependence, crack smoking has intermediate levels, and intranasal forms of cocaine have the lowest levels of dependence (Gossop, Griffiths, Powis, et al, 1994). Signs of serious use include an imbalance in sensory neurons causing a feeling of insects crawling under the skin; calluses and superficial burns on hands caused by repetitive use of a crack pipe to melt and smoke crack cocaine; and brown-black sputum, shortness of breath, and even pneumonia from the residues of the crack smoke.

Cocaine creates a sense of euphoria, or an indefinable high. It is intense but short acting, with the high lasting 15 to 30 minutes for cocaine and 5 to 10 minutes for crack. Withdrawal does not produce the dramatic symptoms observed during withdrawal from other substances. The effects are those more commonly seen in depression, including a lack of energy and motivation, irritability, appetite changes, psychomotor retardation, and irregular sleep patterns. More serious symptoms include cardiovascular manifestations and seizures. Physical withdrawal is not to be confused with the so-called crash after a cocaine high, which consists of a long period of sleep.

In 2007, 7.2% of high school students reported ever having tried cocaine (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2008). Hispanic students (10.9%) were more likely to report ever using cocaine than Caucasian students (7.4%) or African-American students (1.8%). Around 3% reported using cocaine in the past month. Answers to questions about the health risks of cocaine can be obtained by calling the National Cocaine Hotline (800-COCAINE). It also provides referrals to support groups and treatment centers.

Narcotics

Narcotics include opiates, such as heroin, morphine, oxycodone and hydrocodone, as well as opioids (opiate-like drugs), such as hydromorphone (Dilaudid), fentanyl, meperidine (Demerol), and codeine. The narcotics produce a state of euphoria by removing painful feelings and creating a pleasurable experience of a specific quality and a sense of success accompanied by clouding of consciousness and a dreamlike state. Narcotics can be ingested or injected intravenously.

Physical signs of narcotic abuse include constricted pupils, respiratory depression, and often cyanosis. Needle marks may be visible on the arms or legs of chronic users. Physical withdrawal from opiates is extremely unpleasant unless controlled with supervised tapering doses of the opiate or substitution of methadone.

Perhaps more important are the indirect consequences related to the illegal status of narcotic use and the problems associated with securing the drug—health-compromising and often illegal methods used to meet the high cost of the doses, such as prostitution and drug dealing. Health problems result from self-neglect of physical needs (nutrition, cleanliness, dental care); overdose; contamination; and infection from risky sexual transactions and from shared needles, including human immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis B and C. Although different countries have different philosophic approaches to addressing injection drug use, evidence from Canada and Europe suggests needle-exchange programs and nurse-staffed safe injection sites can reduce the risks of overdose and infectious disease transmission, and may also increase the chance an injection drug user will seek drug treatment (Wood, Tyndall, Montaner, et al, 2006). This approach is called harm reduction, and there are increasing examples of its effectiveness in reducing the consequences of serious drug use.

Central Nervous System Depressants and Stimulants

Central nervous system depressants include a variety of hypnotic drugs that produce physical dependence and withdrawal symptoms on abrupt discontinuation. They create a feeling of relaxation and sleepiness but impair general functioning. Drugs in this category include barbiturates, nonbarbiturates (e.g., methaqualone [Quaalude]), and alcohol. Barbiturates combined with alcohol produce a profound depressant effect.

Barbiturates and other sedatives have also been associated with attempted and successful suicides. Flunitrazepam (Rohypnol), known as the “date rape drug,” is a recent hypnotic drug abused by adolescents. Many women report being raped after unknowingly being given flunitrazepam in a drink. Flunitrazepam is 10 times more powerful than diazepam (Valium). It produces prolonged sedation, a feeling of well-being, and short-term memory loss. The drug is illegally imported into the United States. Recent alterations to the tablets include a dye that makes the drug visible if slipped into a drink. Flunitrazepam use is fairly rare among adolescents, with only about 1% reporting past year use (Johnston, O’Malley, Bachman, et al, 2008). A newer date rape drug, with similar effects, is γ-hydroxybutyric acid, or GHB. It dissolves instantly in water and other drinks and is colorless. Combined with alcohol, it has potent risk for coma, respiratory depression, and amnesia. In 2007 fewer than 1% of twelfth graders reported using GHB in the past year, a rate that has decreased since 2004 (Johnston, O’Malley, Bachman, et al, 2008).

The central nervous system stimulants, amphetamines and cocaine, do not produce strong physical dependence and can be withdrawn without much danger. However, psychologic dependence is strong, and acute intoxication can lead to violent, aggressive behavior or psychotic episodes manifested by paranoia, uncontrollable agitation, and restlessness. When combined with barbiturates, these stimulants have euphoric effects that are particularly addictive.

Methamphetamine can be snorted, injected, swallowed, or smoked and produces a burst of energy along with intense, alternating attacks of boldness and paranoia. It provokes an excitement far more intense than that caused by crack and cocaine. The drug, with the street names crank, meth, ice, and crystal meth, is inexpensive and has a longer period of action than that of cocaine. The drug is readily made from ephedrine and pseudoephedrine found in cold medications and diet pills, and the number of homemade “meth labs” in rural areas has increased significantly over the past several years. Some pharmacies have begun to limit access to over-the-counter medications containing pseudoephedrine, and some pharmaceutical companies have substituted other decongestants for pseudoephedrine in their cold medications. The effects of methamphetamine are more intense than those of cocaine. Instead of the short (few minutes) high achieved with crack, a user can remain “up” for hours on a similar dose of crystal meth. After persistent use, dependence makes the effects much more difficult to achieve, and higher doses are generally needed, which leads to bingeing; overdose can cause seizures, cardiovascular collapse, stroke, myocardial infarction, hyperthermia, and amphetamine psychosis. Because methamphetamine also suppresses appetite, thirst, and sleep, this can lead to malnutrition and dehydration. Like cocaine, the crash that occurs as the drug clears the system can be intense. In 2007, just over 3% of twelfth grade students reported trying methamphetamine or crystal meth, and 1.6% used it in the past year (Johnston, O’Malley, Bachman, et al, 2008).

A specific variant of the methamphetamine that is becoming common in certain groups is MDMA. It can be found as tablets imprinted with logos like butterflies or other pictures, as powder sprinkled on pacifiers or suckers, or as a powder that is snorted or smoked. The euphoria, psychedelic effects, and increased tactile sensitivity associated with MDMA use contribute to its popularity at dance club settings, but it can lead to exhaustion and dehydration after long hours of nonstop dancing. In addition, police laboratory testing of drugs seized in Canada and the United States has found that pills sold as Ecstasy often contain crystal methamphetamine in addition to MDMA. In 2007, 5.8% of high school students reported using Ecstasy at least once in their lifetimes (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2008).

Inhalants

Inhalants include glue “sniffing” and the inhalation of plastic cement, spray paint, and other volatile substances (e.g., gasoline, nitrous oxide, and air “dusters” used to remove dust from computers and camera lenses). These dusters contain chemical solvents, usually a form of Freon, that can cause fatal cardiac arrhythmias. Inhalant abuse is most common in the early teenage years. A recent survey noted that 15.6% of adolescents in eighth grade in the United States had abused inhalants at least once in their lives (Johnston, O’Malley, Bachman, et al, 2008). Young teens are often completely unaware of the inherent dangers of “sniffing” or “huffing.” They breathe the inhalants directly or place them in paper or plastic bags or soda cans from which they rebreathe the fumes, which produces an immediate euphoria and altered consciousness. Although these substances give the teen an inexpensive euphoric or “high” feeling, they are extremely dangerous and can cause rapid loss of consciousness and respiratory arrest. In addition, visual-spatial difficulties, visual scanning problems, language deficiencies, motor instability, memory deficits, and attention and concentration problems may occur.

Hallucinogens

Mind-altering drugs or hallucinogens (psychedelic, psychotomimetic, psychotropic, or illusionogenic) are drugs that produce vivid hallucinations and euphoria. These drugs do not produce physical dependence and therefore can be abruptly withdrawn without ill effect. However, the acute and long-term effects are variable, and in some individuals the dissociative behavior may be unduly protracted. This category includes cannabis (marijuana, hashish), psilocybin mushrooms, and lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD).

In some parts of the United States and Canada, marijuana has replaced tobacco as the second most widely used drug by teens, after alcohol (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2008; Smith, Stewart, Peled, et al, 2009). Nationwide, they appear nearly equal: in 2007, 19.7% of high school students nationwide reported using marijuana once or more in the past 30 days, while 20.0% reported similar use of cigarettes (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2008).

Therapeutic Management

Adolescents experiencing toxic drug effects or withdrawal symptoms are commonly seen in emergency departments. Experienced emergency department personnel are familiar with the management of acute drug toxicosis; the signs, symptoms, and behavior characteristics of a variety of substances; and the differences and similarities among them. When the drug is questionable or unknown, knowledge of these factors facilitates handling of the youngster and implementation of a treatment regimen.

The treatment for drug toxicity or withdrawal varies according to the drug and the method used. Make every effort to determine the type and amount of drug taken, the time it was taken, the mode of administration, and factors related to the onset of presenting symptoms.

It is helpful to know the patient’s pattern of use. For example, if two types of drugs are involved, they may require different treatments. Gastric lavage may be employed when the drug has been ingested recently and the cough reflex is intact but would be of little value when the drug has been administered by the intravenous (“mainlined”) or intranasal (“sniffed”) route. Because the actual content of most street drugs is highly questionable, other pharmaceutical agents are administered with caution, except perhaps the narcotic antagonists in cases of suspected opiate overdose. It is necessary to assess for possible trauma sustained while the patient was under the influence of the drug.

Rehabilitation from illicit drug use may require withdrawing the adolescent from both the environment and the chemical agent. Programs must be suited to the individual and may involve foster home placement or a residential treatment setting, although many adolescents are handled in an ambulatory setting. Programs often include group sessions with other adolescents. Adolescents can also obtain information regarding help from the Center for Substance Abuse Treatment hotline (800-662-HELP).

Nursing Care Management

Nurses in almost every setting are increasingly likely to have contact with adolescents who misuse alcohol and other drugs; nurses are in a position to serve as educators and patient advocates. Nurses can be listeners, confidants, and counselors to troubled teens. They are essential members of health care teams whose efforts are directed toward short- and long-term therapy for adolescents with substance abuse disorders, and in some limited situations, they may provide harm reduction services as part of a needle-exchange program or safer injection facility for injection drug users. Most often, however, nurses encounter adolescents who are under the influence of alcohol or other drugs in acute care settings, such as emergency departments and urgent care clinics.

Observation or a description of the behavior often is more valuable than a report by patients or friends as to the chemical agent taken. For example, aggressive behavior and disorientation are often seen in barbiturate, alcohol, stimulant, or hallucinogen intoxication but not in opiate intoxication. Overdose from barbiturates, inhalants, or opiates can result in respiratory failure and coma. Pinpoint pupils are seen only in opiate toxicity. Nurses must be alert for life-threatening consequences of drug toxicity. Equipment and personnel should be available, or the patient should be transferred to facilities that are prepared to provide supportive measures for physiologic depression and psychogenic phenomena.

Keep stimulation to a minimum for agitated, frightened teens. Treatments or tests not immediately required should be postponed. These teens primarily need psychologic support in a nonthreatening environment and close contact with a caring, understanding person who can stay with them and help them maintain social contact. Intoxicated adolescents may be aggressive, and nurses need to be aware of possible risk for injury. Calm, soothing environments can reduce this response.

School nurses play an essential role because they may be the only health care professionals with an opportunity to identify many adolescents with substance abuse problems who appear anxious, depressed, or angry. Assessment of potential substance abuse problems is an important part of evaluation. By ensuring confidentiality within appropriate limits and in a straightforward manner, nurses enable many adolescents to discuss problems involving substance abuse openly.

Obstetric and nursery personnel encounter drug dependence and withdrawal in newborn infants or in a mother with substance abuse disorders. Affected infants are at risk and require special surveillance for complications of withdrawal. Therefore nurses should be aware of the possibility of drug dependence in mothers who come to the hospital for delivery. (See Chapter 10.)

Long-Term Management

A major factor in the treatment and rehabilitation of young teens with substance abuse disorders is careful assessment in the nonacute stage to determine the function that the drug plays in these teens’ lives. Several standardized instruments can be used to identify and screen for substance abuse. These instruments include the HEADSS interview questions, which assess the topics of home, education, activities, drugs, sex, and suicide; and the CAGE AID questionnaire, which assesses alcohol use and abuse (Ewing, 2008; Norris, 2007). Before they can embark on a rehabilitation program, adolescents need help in identifying the issues that motivated them to use drugs and in recognizing their own role in self-destructive, inappropriate drug-abuse behavior.

The motivation phase of treatment is directed toward exploring the factors that influence drug use. It also involves establishing in the teen a feeling of self-worth and a commitment to self-help. It requires a trusting relationship between the adolescent and the health care team and involves a thorough physical examination and assessment of psychologic, educational, and vocational status. A realistic appraisal of the adolescent’s potential and efforts aimed at short-term goals, along with building self-esteem, lays the groundwork for a successful rehabilitation program.

Rehabilitation begins when teens decide that they can and are willing to change. Rehabilitation involves fostering healthy interdependent relationships with caring and supportive adults and exploring alternate mechanisms for problem solving while simultaneously reducing or eliminating drug use. Persons working with troubled young people must be prepared for recidivism, or the tendency to relapse, and maintain a plan for reentry into the treatment process.

The majority of treatment programs for adolescent substance abusers are based on adult 12-step models such as Alcoholics Anonymous. Research is needed to determine whether applying adult models to adolescents is effective. ToughLove (www.toughlove.com) is one such program. The ToughLove philosophy, first employed by Alcoholics Anonymous and Al-Anon, is based on the conviction that parents have the right and the responsibility to be the policymakers in the family, set limits on their children’s behavior, and take control of the household from out-of-control teenagers. The premise is that allowing teenagers to experience the negative consequences of their behavior will bring them closer to accepting help and changing their behavior. Adolescents are offered the choice of (1) getting treatment for their mental health or drug problem or (2) finding another place to live.

Pieper and Pieper (1992) criticize the ToughLove approach, contending that the uncompromising position adopted by parents is harmful to both parents and child. In contrast, they believe treatment emphasizing self-caretaking is more useful as a long-term approach. Depending on the substance, treatment approaches may include tapered withdrawal or medications to assist with the dependence and cravings. For adolescents with ADHD, who are at higher risk of substance abuse, encouraging appropriate medication adherence may prevent self-medication with illicit substances (Wilens, Faraone, Biederman, et al, 2003). Similarly, youth with a history of sexual abuse and similar traumas are at higher risk for substance abuse disorders. Addressing abuse trauma may be necessary as part of or before effective substance abuse treatment (Saewyc, 2007).

The fact remains that effective approaches to the treatment of adolescent substance abuse have limited evidence at present. Treatments sensitive to the developmental transitions of adolescence and the variety of biopsychosocial factors affecting substance use need to be further developed and rigorously evaluated.

Prevention

Given the difficulty of treating substance abusers, prevention is the most effective policy. In recent years a variety of programs have been applied with promising results. Successful programs for reducing substance abuse risk have promoted parenting skills, social skills among children with ADHD, academic achievement, and skills to resist peer influence. Prevention programs are often provided in the school setting, as a way of reaching most youth; however, not all prevention programs are equally effective. The Drug Abuse Resistance Education (DARE) program, for example, which trains police officers to provide the curriculum in schools, is popular and has been rigorously evaluated, but unfortunately has not been shown to be effective in preventing alcohol and drug use (West and O’Neal, 2004).

Peer pressure has been used effectively in prevention efforts. For example, Students Against Destructive Decisions (SADD) (www.sadd.org; formerly known as Students Against Drunk Driving) is an organization of young people who work to eliminate teenage drunk driving and other destructive behaviors. Techniques used by this group include peer counseling, the development of parental guidelines for teenage parties, and community awareness efforts. Nurses should encourage the formation of a SADD chapter in high schools in their communities.

Nurses can also play an important role in other preventive efforts. Young people need to be educated regarding the appropriate use of substances. Health care professionals associated with adolescents should listen to what they are saying, determine what is bothering them, and try to help meet their needs before they resort to drugs.

Prevention programs carry the implicit assumption that poor outcomes facing children at risk can be forestalled or at least reduced. In the past, prevention research has focused on the identification of risk factors and their relationship to drug use. More recently, research has begun to investigate the protective forces that contribute to resisting drug use, such as family, school, and cultural connectedness. Other studies are testing interventions that foster protective factors and assets as a strategy for preventing or reducing alcohol and other drug use. It is important for nurses to consider the multiple risk and protective factors and their interactions in influencing drug use and abuse. Preventive and clinical interventions should attempt to increase the protective factors as well as reduce the risk factors. Nurses in a variety of settings are in a position to identify emerging risk factors, to refer problems for assessment and management, and to foster those parenting skills and interpersonal skills that may be protective against substance abuse.

Suicide

Suicide is defined as the deliberate act of self-injury with the intent that the injury results in death. Most experts distinguish between suicidal ideation, suicide attempt, and suicide. Suicidal ideation involves a preoccupation with thoughts about committing suicide and may be a precursor to suicide. Although it is not uncommon for adolescents to experience occasional suicidal thoughts, nurses should take expressions of suicidal preoccupation seriously and conduct an assessment for appropriate referral. A suicide attempt is intended to cause injury or death but is unsuccessful. Some acts of self-injury or self-harm may not be direct suicide attempts, although self-harm behaviors may occur along with suicidal thoughts or intent. Some researchers and clinicians prefer to use the term self-harm to refer to these behaviors because it makes no reference to intent and a person’s motive may be too difficult or complex to ascertain. Take all self-harm activity seriously.

A survey of U.S. high school students in 2007 indicated that 9.3% of females and 4.6% of males had attempted suicide in the previous 12 months. However, 19% of females and 10% of males had serious suicidal ideation during the 12 months preceding the survey (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2008). In the United States, the suicide rate for adolescents increased dramatically in the 1970s and 1980s, declined from 1990 to 2002, and increased again from 2003 to 2005, in part due to changes in treatment patterns for depression among adolescents. In 2006 the suicide rate was 7.1 per 100,000 young people ages 10 to 24. Suicide is currently the third leading cause of death for adolescents 10 to 24 years of age (Mulye, Park, Nelson, et al, 2009).

The major tasks of adolescence are (1) developing a coherent sense of personal identity, (2) establishing a clear gender and sexual identity, (3) establishing autonomy from parents, (4) beginning to master the ability to be in intimate relationships, (5) acquiring coping skills, (6) consolidating values, and (7) developing educational or vocational goals. It is likely that the onset of depression and suicide during adolescence is due to cognitive development and the newly developed capacity for self-observation and future orientation. Some young people experience a pervasive sense of despair when they look into the future and are faced with a discrepancy between what they have been led to anticipate and what they are truly able to obtain. Self-hate and hopelessness may result. In part, the despair is a consequence of adolescents’ newly developed cognitive ability to consider the abstract and hypothetical, which may paint a bleak picture of their lives in the future. As adolescents struggle to establish their sense of self, they constantly seek external validation and confirmation of who they are. Introspection becomes a prominent part of this process. Social experiences and peer relationships become more important during the adolescent years, and the increased need to belong and conform leads to an increased vulnerability to depression and suicidal thought. In the context of this intrapersonal and interpersonal searching, self-esteem becomes pivotal, moderating hopelessness and developing a strong sense of self.

Young people also focus on mastering empathy during the teen years. The ability to truly empathize with others creates a new awareness of the suffering of others. The capacity to passionately feel both joy and sorrow is exciting, yet frightening. For some, the pain seems overwhelming. Because they most likely have not lived through intensely painful experiences, they have not developed the means to cope with deep emotions. They may feel alone in experiencing pain and sorrow and unable to recognize or express their need for support. For adolescents who have not had guidance and experience in problem solving and coping with sorrow, suicide may represent a means of escape and seem the only option.

Many of today’s young people have been desensitized to death by constantly viewing it on television, in the movies, and in video games. Suicide may be romanticized and inaccurately portrayed. The frequency of contagion suicides, or copycat suicides, among young people (i.e., an increase in youth suicides after the suicide of one teenager is publicized) may indicate an adolescent perception of suicide as glamorous. Simultaneously, changes in families have insulated teens from other kinds of death experiences. Improvements in health care and geographic mobility in the United States isolate family members from one another, and young people are not as likely to participate in the painful emotional realities of sickness and death among older family members.

Over several decades the increasing youth suicide rate paralleled increasing rates of child poverty, violence, and parental divorce and decreasing parental involvement and support. As adolescents strive for healthy autonomy from their parents and master the skills required for interdependence with others, they begin to question and criticize their parents. They attempt to discover their own identity and discern which qualities of their parents they want to incorporate into their lives. This questioning and criticizing process can generate a sense of guilt, insecurity, fear, and conflict. Even though they may rebel against their parents, young people need to feel needed, wanted, and loved by their families. Studies indicate that young people who believe that their families care about them are less likely to show suicidal behaviors (Resnick, Bearman, Blum, et al, 1997).

The changing roles of young people in society have also had an impact on adolescent suicidality. The period of adolescence is prolonged in the United States, and roles for young people are unclear and difficult to formulate. The earlier onset of puberty and the growing need for higher educational attainment has increased the period of adolescence from 6 years to potentially 14 years or longer. This extended time between childhood and adulthood has created greater role confusion. Today the majority of parents are employed at jobs away from home. Consequently, young people do not have the opportunity to see their parents as vocational role models. The higher percentage of adolescents within the total population and the increased difficulties adolescents have in obtaining jobs and being admitted to college also contribute to a higher youth suicide rate.

Although most people emerge from adolescence with a healthy sense of who they are and where they are headed, the widespread belief that adolescence is a time of turmoil—of storm and stress—has created a sense that hopelessness and despair are a normal part of the second decade of life. This is not so. Most young people do not experience adolescence as a time of despair. Depressive symptoms, acting-out behaviors, and talk of suicide need to be taken seriously. They are not a common phase of adolescence—they are a call for help that requires the response of nurses and other professionals.

Incidence

The incidence of youth suicide varies greatly by gender and racial or ethnic background. In 2006, for every 100,000 young people ages 10 to 24 in the United States, the suicide rates were 11.4 for males and 2.4 for females (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2006). The rates were lower for African-American and Asian-American male adolescents compared with Caucasian adolescents: 7.6 for African-American males, 8.35 for Asian-American males, compared to 12.1 for Caucasian males. However, suicide rates were higher for Asian-American females (2.9) than either African-American females (1.3) or Caucasian females (2.5). Native American–Alaskan Native–Native Hawaiian adolescents have the highest rates of suicide attempts, at 25.4 per 100,000 among males, and 7.9 among females.

Although Native Americans have a high rate of suicide compared with other racial and ethnic groups in the United States, there is great variation among tribes. Tribes with less social integration, less adherence to tribal traditions, and a high degree of individuality generally have higher suicide rates than tribes that are tightly integrated and adhere to traditional values and practices. Family, school, and tribal connectedness has been shown to be a protective factor associated with lower rates of hopelessness and suicidality among high-risk Native American adolescents (Dexheimer-Pharris, Resnick, and Blum, 1997).

Incarcerated youths in public correctional facilities have a higher suicide rate than adolescents in the general population. Minors detained in adult jails are at especially high risk for suicide.

Even though the statistics reveal hopelessness and despair among young people, the true incidence of completed suicides in children and adolescents is not known because of general underreporting. Deaths by suicide often are reported as accidental because of pressures exerted by the family and society to avoid the cultural and religious stigma associated with self-destruction. The high accident rate in this age-group may reflect suicides masked by accidental death or homicide. In the United States the mortality patterns for suicide and homicide among youths follow similar trends. It is possible that these forms of violent death in youths share common antecedents.

The incidence of suicide attempts, as opposed to suicide completions, is even more difficult to measure. There is no national reporting system for suicide attempts, although national surveys of youth in school such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Youth Risk Behavior Survey do ask for self-report of suicide attempts. Although more males than females complete suicide, suicide attempts are far more common in females than in males. In 2007, 9.3% of females compared to 4.6% of males reported they had attempted suicide once or more in the past year (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2008). The major difference between suicide attempts and suicide completions is often whether a lethal weapon is available. Successful suicide is more likely when alcohol and firearms are involved. Thus a higher incidence of youth suicide occurs in societies in which alcohol and lethal weapons are readily available to youths. Firearms were more likely to be present in the homes of suicide completers than in those of youths who attempted suicide or had suicidal ideation (Shain and Committee on Adolescence, 2007).

Factors Associated with Suicide Risk

An effective research methodology that studies the risk factors associated with suicide is psychologic autopsy, which involves data collection from the deceased person’s family, friends, teachers, counselors, spiritual advisers, and educational and health care records. Psychologic autopsies reveal several factors associated with adolescent suicide: depression or other affective disorders, drug and alcohol abuse, family conflict, prior suicide attempt, antisocial or aggressive behavior, a family history of suicidal behavior, and the availability of a firearm (Box 21-10). Another approach is to examine the factors associated with self-reported suicide attempts among youth in population-based school surveys. Although this will not capture the experiences of teens who are homeless or have dropped out of school, the large representative nature of the sample can be useful for understanding risks reported by the teens themselves, which may not have been revealed to friends, family, or others.

Individual Factors

The single most important individual factor associated with an increased risk of suicide is the presence of an active psychiatric disorder (e.g., affective disorders such as depression and bipolar disorder, substance abuse, and conduct disorder). Several studies have documented the relationship between psychiatric illness and suicide. Shaffer, Gould, Fisher, and colleagues (1996) found that more than 90% of the children and adolescents who committed suicide were retrospectively found to meet the criteria for at least one major psychiatric diagnosis. Depression is the predominant affective disorder that represents a major risk for suicide.

Psychiatric illness is also associated with an increased potential for suicidal ideation or suicide attempts. In a random sample of 1285 children and adolescents, Gould, King, Greenwald, and colleagues (1998) noted that the rate of suicide attempts was 22% among children with one psychiatric illness (major depression). For children with two or more psychiatric disorders, the rate of suicide attempts was 18 times higher, and the rate of suicidal ideation was eight times higher than the rate in healthy children.

Comorbidity of an affective disorder and substance abuse also increases the risk for suicide (Jellinek and Snyder, 1998). Alcohol use in particular has been associated with more than 50% of suicides (Shain and Committee on Adolescence, 2007). For some teens, suicide becomes the final pathway for release from their psychiatric and social problems (Jellinek and Snyder, 1998). Childhood and adolescent suicide victims are reported to have higher rates not only of depression but also conduct disorders; bipolar disorders; substance abuse; interpersonal problems with parents; and a family history of depression, substance abuse, and suicidal behavior.

Gay, lesbian, and bisexual adolescents are at particularly high risk for suicide attempts, especially if raised in an environment where they are denied support systems (Russell and Joyner, 2001; Saewyc, Skay, Hynds, et al, 2007). When gay, lesbian, or bisexual young persons grow up in a community and family that do not accept their orientation, they are likely to internalize the homophobia and feel self-hate, which often turns into suicidal feelings. This alienating social context challenges self-esteem. Youths most at risk are those who struggle with sexual orientation, who have not yet disclosed their identity, and who experience high levels of harassment or violence. Parent and family responses when adolescents disclose their orientation (“coming out”) are also important: a recent study found that teens who thought their parents were rejecting (even if the parent did not intend his or her response to be rejecting) were eight times more likely to attempt suicide in later adolescence (Ryan, Huebner, Diaz, et al, 2009). In assessing for level of risk, the youths’ knowledge, feelings, and experience in the area of sexual orientation and identity are important. The amount of accurate knowledge and the level of support youths feel directly affect their risk for depression, substance abuse, and suicidality. By providing care that enhances support systems and nurtures opportunities for the healthy development of self-esteem in gay, lesbian, and bisexual adolescents and their families, nurses can play a significant role in reducing youth suicide rates in the United States.

Additional individual risk factors for suicidal behavior include poor academic progress, a history of being a victim of sexual abuse, learning disabilities, attention deficit disorder, chronic illness, disability, and antisocial behavior (especially assaultive behavior, which when experienced with suicidal feelings, provides a strong risk indicator for suicide potential).

In the context of these major risk factors, adolescents’ maturity, particularly their cognitive development, may determine the likelihood of suicidal behavior. Adolescents who have developed and mastered problem-solving and social skills, have an internal locus of control, and have a positive sense of their future will be less likely to turn to suicide, even when faced with extreme stressors. In contrast, youths who see themselves as totally helpless, as victims of fate, or who are impulsive, unable to tolerate frustration, filled with self-hatred, experiencing excessive guilt, suffering from humiliation, withdrawn and aloof, or aggressive and impulsive will be more likely to take their own life.

Family Factors

Families hold the greatest potential for protecting young people from suicidal behavior. Families who respect individuality, are cohesive and caring, balance discipline with a supportive and understanding relationship, have good systems of communication, and have at least one attentive and caring parent available to the child protect adolescents from suicidal outcomes. In contrast, family risk factors for suicide include:

• A family history of suicidality, substance abuse, or emotional disturbance

• Isolation within an inflexible family system

Nursing interventions should be designed to enhance family cohesiveness (Box 21-11). However, in working with families who have experienced the loss of a child through suicide, nurses should remember that although the risk of suicide is higher in families that are under stress and less cohesive, youth suicide can and does happen in the context of a caring and cohesive family environment.

Social and Environmental Factors

Important social and environmental influences that protect adolescents from suicidal behavior include good peer relationships, regular participation in religious services (unless the religious beliefs or community is rigid and unsupportive, especially for gay, lesbian, or bisexual youth), strong social support within the community or school system, and available options for vocational and educational development. In contrast, factors associated with increased suicide risk include incarceration, social isolation, acute loss of a boyfriend or girlfriend, lack of future options, and the availability of firearms in the home.

Methods

Firearms are the most commonly used instruments in completed suicides among male and female adolescents (Shain and Committee on Adolescence, 2007). For adolescent males the second and third most common means of suicide are hanging and overdose; for adolescent females the second and third most common means are overdose and strangulation (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2006).

Suicide Attempt

The most common method of suicide attempt is overdose or ingestion of a potentially toxic substance, such as drugs. The second most common method of suicide attempt is self-inflicted laceration. It has been suggested that some automobile crashes may actually be suicide attempts rather than accidents; however, unless the teen discloses this intent, there is no clear evidence of intending self-harm, and such crashes are identified and counted as unintentional rather than intentional injuries.

Precipitating Factors

Although suicide is often an impulsive act, it takes place against a backdrop of individual, family, and social risk factors and is often carried out in response to an exacerbation of longstanding stressors or in reaction to an acute precipitating factor. The most common factors precipitating adolescent suicide are a fight with a close friend; the breakup of an important relationship; failure in an important area (e.g., school activities); changing schools or moving; involvement in the legal system; discovery of pregnancy plus family crisis or rejection by boyfriend; and the death of a close friend, relative, or pet.

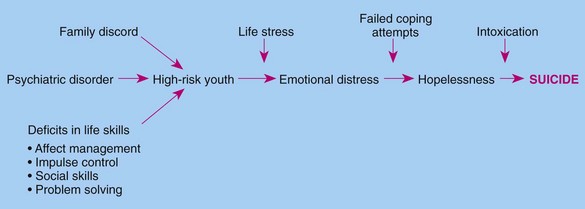

Fig. 21-3 presents a model for understanding the dynamics of the pathway from risk factors to completed suicide. This model incorporates multiple factors related to individual differences, as well as family and social contexts (Box 21-12).

Nursing Care Management

Nurses play a pivotal role in reducing youth suicide. Nurses have the opportunity to provide anticipatory guidance to parents and adolescents. They can teach parents to be supportive and to develop positive communication patterns that help teens feel connected with and loved by their families. To foster healthy development, encourage parents to provide teens with creative outlets and to assist young people in accepting strong emotions—pain, anger, and frustration—as a normal part of the human experience.

Given what is known about youth suicide, nurses should ask parents, especially those of at-risk teenagers, if firearms are available in the house and, if so, recommend their removal. Parents must ensure that their children—especially children who are depressed, have poor problem-solving skills, or use drugs or alcohol—do not have access to firearms. Parents must be educated on the warning signs of suicide (Box 21-13).