Family-Centered End-of-Life Care

Palliative Care in Childhood Terminal Illness

Decision Making at the End of Life

Ethical Considerations in End-of-Life Decision Making

Awareness of Dying in Children with Life-Threatening Illness

Nursing Care of the Child and Family at the End of Life

Management of Pain and Suffering

Parents’ and Siblings’ Need for Education and Support Through the Caregiving Process

Special Decisions at the Time of Dying and Death

http://evolve.elsevier.com/wong/ncic

The Child with Cancer, Ch. 36

Communicating with Families, Ch. 6

Compliance, Ch. 27

Ethical Decision Making, Ch. 1

Family-Centered Care, Ch. 1

Family-Centered Care of the Child with Chronic Illness or Disability, Ch. 22

Family-Centered Home Care, Ch. 25

Human Immunodeficiency Virus Infection and Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome, Ch. 35

Long-Term Sequelae of Treatment, Ch. 36

Neonatal Loss, Ch. 10

Pain Assessment; Pain Management, Ch. 7

Pain in Neonates, Ch. 7

Sudden Infant Death Syndrome, Ch. 13

Palliative Care in Childhood Terminal Illness

In 2007 more than 53,000 children from birth to 19 years of age died in the United States (Heron, Sutton, Xu, et al, 2010). Nearly 70% of 29,241 infant deaths resulted from congenital malformations, low birth weight, sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS), maternal complications, accidents, cord and placental complications, newborn respiratory distress and bacterial sepsis, neonatal hemorrhage, and circulatory system diseases (Heron, Sutton, Xu, et al, 2010). Accidents (unintentional injuries), followed by assault (homicide), cancer, and intentional self-harm (suicide), are the leading causes of death for all children 1 to 19 years of age (Heron, Sutton, Xu, et al, 2010). (See Chapter 1.)

In addition to the children who die each year, approximately another 400,000 children in the United States are living with a life-threatening illness (Calabrese, 2007). The number of children living with chronic, life-limiting illnesses has increased exponentially as advances in technology and pharmacology have led to improved treatments (Palfrey, Tonniges, Green, et al, 2005). These chronic conditions often result in substantial health care needs and increase the possibility of death during childhood (Box 23-1) (Himelstein, Hilden, Boldt, et al, 2004). Although the number of children who die of any one illness is small, those children who will not survive their illness need a significant amount of care. The majority of these children die in a hospital setting, most frequently in an intensive care unit (Feudtner, Silveira, and Christakis, 2002), having been mechanically ventilated (Feudtner, Christakis, Zimmerman, et al, 2002), and often experiencing acute and chronic pain and other distressing symptoms (McCulloch and Collins, 2006; Pritchard, Burghen, Srivastava, et al, 2008; Zhukovsky, Herzog, Kaur, et al, 2009) (see Evidence-Based Practice box).

Fortunately, increasing attention has been given in recent years to the needs of children who have experienced irreversible trauma or who have incurable diseases or disorders. The American Academy of Pediatrics (2000) released a statement on the need to incorporate principles of palliative care in pediatric practice. In addition, a number of national and international specialty groups have published suggested guidelines for the care of children with life-threatening and terminal illnesses (Bowden, Conway-Orgel, Dulzack, et al, 2003; Hazinski, Markenson, Neish, et al, 2004; Masera, Spinetta, Jankovic, et al, 1999; World Health Organization, 1998a; National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization, 2000). Unfortunately, currently health care professionals lack clinical education in the principles of making the transition with children from curative to palliative care or methods of adequately managing the pain and suffering experienced by children and their families during the dying process (Hilden, Emanuel, Fairclough, et al, 2001; Zhukovsky, Herzog, Kaur, et al, 2009). It is clear, however, that as our ability to treat disease, disability, and trauma advances, we must also improve our care of those children who live with the specter of chronic, life-threatening illness and premature death.

Principles of Palliative Care

Palliative care involves an interdisciplinary approach to the management of a child’s life-threatening or life-limiting illness from diagnosis through death when cure may not be possible, and focuses on preventing or relieving the child’s symptoms and support of the child and family (Hubble, Ward-Smith, Christenson, et al, 2008; Johnston, Nagel, Friedman, et al, 2008). The World Health Organization (1998c) defines pediatric palliative care as being the “active total care of the child’s body, mind, and spirit, and also involv[ing] giving support to the family. It begins when illness is diagnosed, and continues regardless of whether or not a child receives treatment directed at the disease.” Palliative care interventions do not serve to hasten death; rather, they provide pain and symptom management, attention to issues faced by the child and family with regard to death and dying, and promotion of optimal functioning and quality of life during the time the child has remaining. The implementation of neonatal and pediatric palliative care consulting services within hospitals has led to enhanced quality of life and end-of-life care for children and their families and support for their care providers (Hubble, Ward-Smith, Christenson, et al, 2008; Jennings, 2005; Pierucci, Kirby, and Leuthner, 2001).

Several principles are the hallmarks of palliative care. The child and family are the unit of care. The death of a child is an extremely stressful event for a family because it is out of the natural order of things. Children represent health and hope, and their death calls into question the understanding of life. An interdisciplinary team of health care professionals consisting of social workers, chaplains, nurses, personal care aides, and physicians skilled in caring for children with life-threatening or life-limiting conditions assists the family by focusing care on the complex interactions between physical, emotional, social, and spiritual issues.

Palliative care seeks to create a therapeutic environment, as homelike as possible, if not in the child’s own home. Through education and support of family members, an atmosphere of open communication is provided regarding the child’s dying process and its impact on all members of the family.

Decision Making at the End of Life

Discussions concerning the possibility that a child’s illness or condition is not curable and that death is an inevitable outcome causes everyone involved a great deal of stress. Physicians, other members of the health care team, and families consider all information regarding the child’s situation and make decisions to which all parties agree and which will have a profound impact on the child and family.

Ethical Considerations in End-of-Life Decision Making

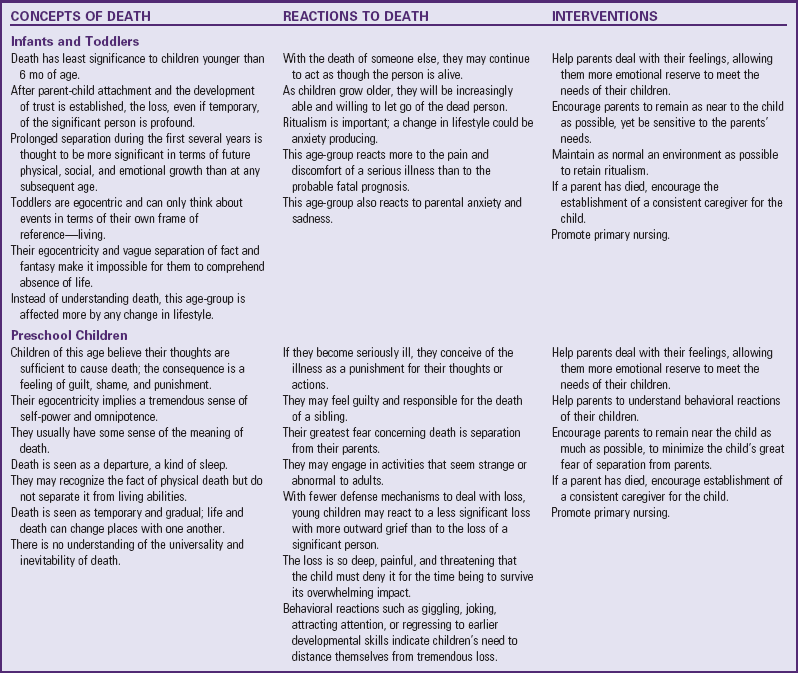

A number of ethical concerns arise when parents and health care professionals are deciding on the best course of care for the dying child (Table 23-1). Many parents and health care providers are concerned that not offering treatment that would cause potential pain and suffering, but might extend life, would be considered euthanasia or assisted suicide. To eliminate such concerns, one must understand the various terms. Euthanasia involves an action carried out by a person other than the patient to end the life of the patient suffering from a terminal condition. This action is based on the belief that the act is “putting the person out of his or her misery.” This action has also been called mercy killing. Assisted suicide occurs when someone provides the patient with the means to end his or her life and the patient uses that means to do so. The important distinction between these two actions is who is actually acting to end the person’s life.

TABLE 23-1

COMMON ETHICAL DILEMMAS IN CARING FOR TERMINALLY ILL CHILDREN

Modified from Hockenberry-Eaton M, Bottomley S, Dahl KL, et al: Essentials of pediatric oncology nursing: a core curriculum, Glenview, Ill, 1998, Association of Pediatric Oncology Nurses.

The American Nurses Association Code for Ethics (2005) does not support the active intent on the part of a nurse to end a person’s life. However, it does permit the nurse to provide interventions to relieve symptoms in the dying patient even when the interventions involve substantial risks of hastening death. When the prognosis for a patient is poor and death is the expected outcome, it is ethically acceptable to withhold or withdraw treatments that may cause pain and suffering and to provide interventions that promote comfort and quality of life. Therefore providing palliative care for patients is the ethically correct choice in such a circumstance.

Physician and Health Care Team Decision Making

Physicians often make decisions about care on the basis of the progression of the disease or amount of trauma, the availability of treatment options that would provide cure from disease or restoration of health, the impact of such treatments on the child, and the child’s overall prognosis (Davis and Eng, 1998). Often the main determinants prompting physicians to discuss end-of-life issues and options for children with critical illnesses are the child’s age, premorbid cognitive condition and functional status, pain or discomfort, probability of survival, and quality of life (Masri, Farrell, Lacroix, et al, 2000). When the physician discusses this information openly with families, a shared decision-making process can occur and decisions can be made regarding do-not-resuscitate (DNR) orders and care that is focused on the comfort of the child and family during the dying process (see Table 23-1). However, uncertainty of the child’s prognosis among health care providers is frequently a barrier to the provision of optimal palliative care (Davies, Sehring, Partridge, et al, 2008; Thompson, Knapp, Madden, et al, 2009). As a result, many families do not always receive the option of shifting the focus of treatment to the child’s comfort and quality of life when cure is unlikely (see Research Focus box).

The current approach by palliative care experts promotes the inclusion of palliative care along the continuum of care from diagnosis through treatment, not merely at the end of life (Field and Behrman, 2004; Himelstein, Hilden, Boldt, et al, 2004; Hubble, Ward-Smith, Christenson, et al, 2008), and sometimes after the child’s birth in the neonatal intensive care unit (Carter, 2004; De Lisle-Porter and Podruchny, 2009).

Family Decision Making

Rarely are families prepared to cope with the numerous decisions that must be made when a child is dying. When the death is unexpected, as in the case of an accident or trauma, the confusion of emergency services and possibly an intensive care setting presents challenges to parents as they are asked to make difficult choices. Determination of parental decision-making preferences, which may be active or independent, collaborative or shared between parents and provider, or passive or authoritarian, can help providers support parents (Higgins and Kayser-Jones, 1996; Hinds, Oakes, Furman, et al, 2001; Pyke-Grimm, Degner, Small, et al, 1999). If the child has experienced a life-threatening illness such as cancer or lived with a chronic illness that has now reached its terminal phase, parents are often unprepared for the reality of their child’s impending death (see Family-Centered Care box).

Earlier acknowledgment by both physicians and parents that children have no realistic chance for cure is associated with earlier implementation of DNR orders, less use of aggressive therapies, and greater provision of palliative care measures (Wolfe, Klar, Grier, et al, 2000). Additional factors found to influence parents’ decisions to limit or withdraw life-sustaining measures include parents’ prior end-of-life decision making for loved ones; observations of pain and suffering of their child and other hospitalized children; various emotions, including guilt and sorrow; and awareness of their child’s desire to forego life-sustaining measures (Sharman, Meert, and Sarnaik, 2005). The use of a pediatric advance directive for older minors may raise awareness of children’s wishes as part of the family decision-making process (Knapp, Huang, Madden, et al, 2009; Zinner, 2009) (see Research Focus box).

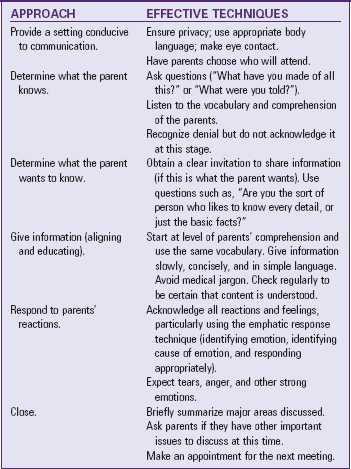

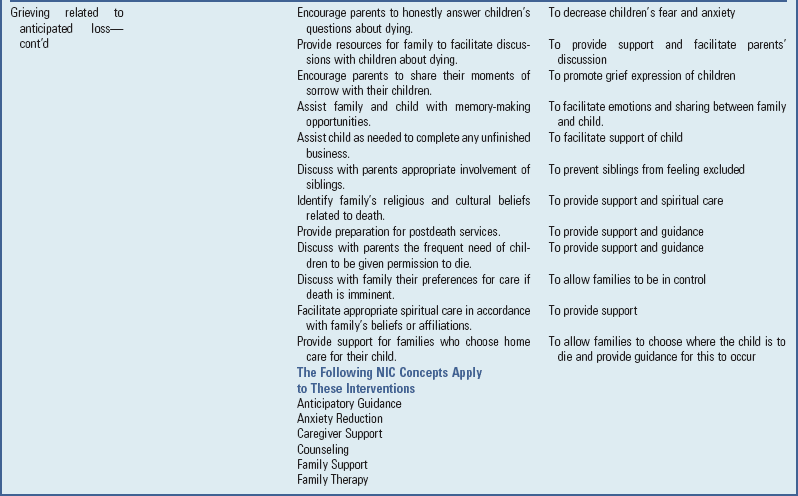

As the group of health professionals who are most involved with families, nurses are in an excellent position to ensure that families know the options available to them (Box 23-2). The nurse’s first responsibility is to explore the family’s wishes. This is best done with the physician, but at times nurses need to initiate the process. When discussing difficult issues, nurses are open to the child’s or family’s indirect comments that communicate uncertainty or concerns about the course of care. Nurses answer questions honestly, and if they do not know the answer, reassure the family that they will arrange for a discussion with the physician. It is important to address any fantasies or misunderstandings by seeking to clarify what the family has heard. Finally, it is important for the nurse to remain neutral and avoid giving personal opinions or experiences. The goal of communication is to facilitate the identification of the family’s wishes, based on their unique values and beliefs (Table 23-2).

Awareness of Dying in Children with Life-Threatening Illness

![]() One of the initial reactions of parents (and some health care professionals) to the discovery of a life-threatening illness is to protect the child from the impact of the diagnosis. Often they do not have the knowledge or energy to help the child (Bluebond-Langner, 1978; Dyregrov, 2004; Kirwin and Hamrin, 2005; Zhukovsky, Herzog, Kaur, et al, 2009). However, it is now widely understood that terminally ill children develop an awareness of the seriousness of their diagnosis, even when protected from the truth (Bluebond-Langner, 1978; Spinetta, 1974). The avoidance of talking openly and honestly with children with life-threatening illnesses and their siblings can lead to fear, guilt, misconceptions, and the pain of grieving alone. Surviving siblings may experience psychiatric sequelae as children and into adulthood (Kirwin and Hamrin, 2005; Schoen, Burgoyne, and Schoen, 2004).

One of the initial reactions of parents (and some health care professionals) to the discovery of a life-threatening illness is to protect the child from the impact of the diagnosis. Often they do not have the knowledge or energy to help the child (Bluebond-Langner, 1978; Dyregrov, 2004; Kirwin and Hamrin, 2005; Zhukovsky, Herzog, Kaur, et al, 2009). However, it is now widely understood that terminally ill children develop an awareness of the seriousness of their diagnosis, even when protected from the truth (Bluebond-Langner, 1978; Spinetta, 1974). The avoidance of talking openly and honestly with children with life-threatening illnesses and their siblings can lead to fear, guilt, misconceptions, and the pain of grieving alone. Surviving siblings may experience psychiatric sequelae as children and into adulthood (Kirwin and Hamrin, 2005; Schoen, Burgoyne, and Schoen, 2004).

Discussing Death with Children

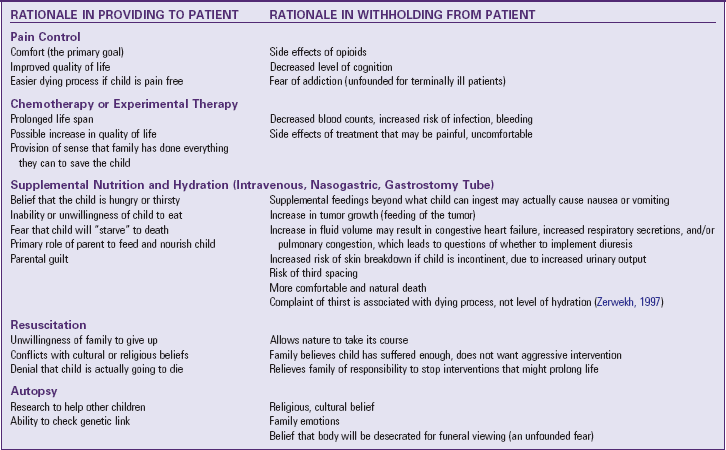

Children need honest and accurate information about their illness, treatments, and prognosis. This information needs to be given in clear, simple language. In most situations this best occurs as a gradual process, characterized by increasingly open dialogue among parents, professionals, and the child (Hockley, 2000; Lee and Johann-Liang, 1999). Providing an atmosphere of open communication early in the course of an illness facilitates answering difficult questions as the child’s condition worsens. Providing appropriate literature about the disease, as well as about the experience of illness and possible death, is also helpful. Exactly how and when to involve children in decisions regarding care during their dying process and death is an individual matter. In general, the nurse should ask parents how they would like their child to be told of the prognosis and how they want to be included in their child’s care. Some parents may request that their child not be told that he or she is dying, even if the child asks. This often places health care providers in a difficult situation. Children, even at a young age, are perceptive. Despite not being told outright that they are dying, they realize that something is seriously wrong and that it involves them. Children deserve to be provided with the truth.

Often, helping parents understand that honesty and shared decision making between them and their child at this time are important for the emotional health of the child and family will encourage parents to allow discussion of dying with their child. The truth provides answers for future questions and fosters trust. It is difficult to encourage children to be honest, confide in others, and openly discuss their fears if parents refuse to do the same.

Honesty is certainly not the easiest solution; the truth may prompt children to ask other distressing questions. The question many parents and health professionals dread the most is, “Am I going to die?” When children have the answer to this question, the next question is, “When?” Children need answers that are straightforward, yet caring. In telling children that a cure is no longer possible, one must also leave room for hope. The hope is redirected from cure to quality of life and comfort.

Adults need to be prepared to assist children in understanding and coping with the emotions of dealing with their own death and to reassure children that it is all right to express their feelings as they choose. If given the opportunity to ask questions, children will tell others how much they want to know. Asking questions such as, “If the disease came back, would you want to know?” or “Do you want others to tell you everything, even if the news is not good?” helps children set the limits of how much truth they can accept and handle. Children need time to process feelings and information so that they can assimilate and ideally accept the inevitable fact of mortality. As the child and family move through the dying process, it is important for the family to share their beliefs regarding noncorporeal continuation and to reassure the child that he or she will not be alone at the time of death, and that the child will always be loved and remembered (Stevens, 1998).

Parents may require professional support and guidance in this process from a nurse, social worker, or child life specialist who has a good relationship with the child and family. Certain principles and guidelines can assist nurses and families in determining how to present facts about possible death and hope to a child in a way that fosters trust, enhances meaningful communication, and offers emotional support (Table 23-3 and Box 23-3). Professionals may also provide information to parents about their child(ren)’s general developmental understanding of and reactions to death and how to explain death in a developmentally appropriate manner and offer to assist parents when speaking with their terminally ill child and siblings.

TABLE 23-3

COMMUNICATING WITH DYING CHILDREN

Modified from Doka KJ: Living with life-threatening illness: a guide for patients, their families, and caregivers, Lexington, Mass, 1993, Lexington Books.

• Encourage parents to approach the discussion of death with a child gently. What is said is important, but how it is said is critical to how a child is able to accept, within their abilities, the reality of death.

• Advise parents to begin the discussion with a child by using a nonthreatening example such as trees and leaves and how long they live.

• Allow the child’s questions to guide the discussion and avoid unnecessary information; speak on the child’s developmental level; provide basic information slowly, directly, and honestly using simple, concrete, age-appropriate words, including “die”; avoid the use of euphemisms (e.g., pass away, lost).

• Clarify misconceptions and let the child know he or she did not cause the illness or death; allow the child to express his or her feelings and accept whatever emotions are expressed by the child; provide warmth and support during the discussion and speak with a calm and reassuring voice.

• Ask the child to repeat what has been discussed to clarify any misunderstandings.

• Encourage family members to discuss the child’s impending death openly and honestly with the child, siblings, and other family members (Ethier, 2008).

The nurse can facilitate ongoing and open communication about death and dying through the use of various resources, including books (e.g., The Fall of Freddie the Leaf by Leo Buscaglia) and movies (e.g., The Velveteen Rabbit by Margery Williams) (Auvrignon, Leverger, and Lasfargues, 2008; Ethier, 2005). Play and art activities (e.g., music, drawing, painting, writing) offer a vehicle for expression of emotions that are often difficult for children to put into words (Rollins and Riccio, 2002).

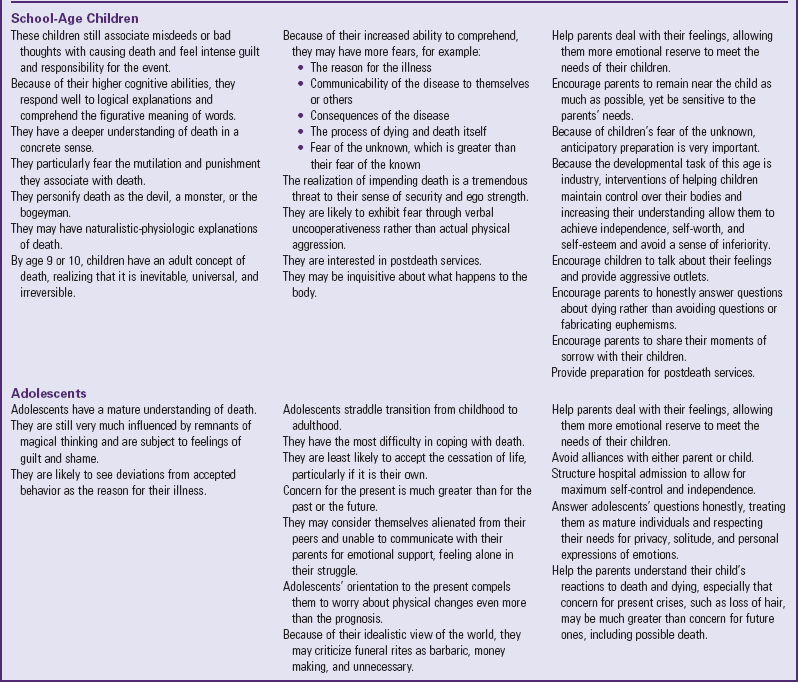

Children’s Understanding of and Reactions to Dying

Studies, although limited, have found a child’s concept of death to be influenced by their age and cognitive development, nationality, religion, life-limiting illness, personal experiences with death, and family members’ explanations and attitudes surrounding death (Silverman, 2000; Slaughter, 2005; Speece and Brent, 1996; Spinetta, 1974). By approximately 7 years of age most children understand the key bioscientific components of death (Box 23-4). Studies have found children ranging in age from 4 to 12 years to have an adultlike understanding of death. However, anyone working with children must be aware of significant developmental variations related to their understanding and fears of death. These variations are discussed in detail on pp. 883-885 (Speece and Brent, 1996). Cultural, national, and religious differences in beliefs about an afterlife have also been found to influence a child’s understanding of death (Speece and Brent, 1996). Sensitive assessment of the child’s developmental understanding of death and the family’s cultural and spiritual beliefs related to dying and death is an important but often overlooked aspect of care (Bull and Gillies, 2007; Feudtner, Haney, and Dimmers, 2003; Heilferty, 2004; Kagawa-Singer, 1998).

Infants and Toddlers

Exactly how preverbal children view death is a mystery, since there is no way of reliably assessing their views of death. On the basis of their cognitive abilities, it is likely that they have no concept of death. The egocentricity of toddlers and their vague separation of fact and fantasy make it impossible for them to comprehend absence of life. Although they may repeat what initially sounds like a correct definition of death, such as, “Grandpa is dead; he went to heaven,” they may expect Grandpa’s return for several months before accommodating themselves to the absence. They can perceive events only in terms of their own frame of reference: living.

Reactions to Dying: Separation from parents and alterations in their routine represent threats to the toddler who is seriously ill and to the well toddler sibling. Behavioral responses may include regression to less independent levels of behavior related to speech, toileting, eating, drinking, crying, clinging, biting, hitting, withdrawal, and physical illness. Toddlers may perceive the seriousness of their condition from the parents’ reactions of anxiety, sadness, depression, or anger. Although young children are unaware of the reason for such emotions, they often find their parents’ behavior disturbing and upsetting. Helping parents deal with their feelings allows them more emotional reserve to meet the needs of their children. Encouraging parents to stay in the hospital as much as possible and to participate in the child’s care promotes the parents’ and child’s adjustment to a serious, potentially fatal illness or injury. Helpful interventions for infants and toddlers include providing the child with physical comfort (e.g., being held or rocked), consistent providers, consistent routines, and familiar objects (e.g., favorite blanket or toy) (Ethier, 2008; Himelstein, Hilden, Boldt, et al, 2004).

Preschool Children

Several characteristics of preschoolers’ cognitive and psychologic development affect their concept of death. Because they are egocentric at this age, they often have a tremendous sense of self-power and omnipotence. Therefore they believe that their thoughts are sufficient to cause events. The consequence of such magical thinking is feelings of guilt, shame, and punishment (Speece and Brent, 1996).

Concept of Death: Children between 3 and 5 years of age have usually heard the word death and have some sense of its meaning. They see death as a departure, possibly as a type of sleep. They may recognize the fact of physical death, but do not separate it from living abilities. The dead person in the coffin still breathes, eats, and sleeps. Death is temporary and reversible; life and death can change places with one another. Because of the immature concept of time, they have no real understanding of the universality and inevitability of death. Words such as forever and everyone have meaning only in the child’s egocentric thinking. Waiting until Christmas may be “forever,” and anybody the child denotes is “everyone.” Children of this age take the literal meaning of words, and euphemisms are avoided. Preschoolers who are told that Grandma has “gone to sleep” may fear going to sleep themselves.

Reactions to Dying: If preschoolers become seriously ill, they may conceive of the illness as punishment for their thoughts or actions. The usual diagnostic and treatment procedures, in combination with enforced hospitalization, can confirm their belief that they are being punished. If their parents do not stay with them during hospitalization or prevent the traumatic procedures, they may believe that the parents are retaliating for previous misdeeds or bad thoughts (Fig. 23-1).

The same principles of magical thinking and omnipotence affect preschoolers when a sibling becomes critically ill or dies. One of the most significant types of death is SIDS. Because it occurs unexpectedly to a healthy infant (who may have been rejected and unwanted by a jealous sibling), preschoolers find no evidence to support a physical cause of death. Indeed, the parents often are unaware of the reason for the fatality and may question any possible cause. If preschoolers are in any way accused or suspected of having harmed the infant, they may feel extremely guilty and responsible for the tragedy. On observing their parents’ acute grief, they may interpret the anger or depression as a rejection of them.

When a child becomes ill, the healthy siblings experience the loss of routine and parental attention. It is natural for them to resent such disruptions and blame the changes on the ill child. However, preschoolers have less ability than older children to understand the reasons for the parents’ prolonged absence from home. Although parents may explain how ill the sibling is, what the hospital is like, and why they must be there, preschoolers see only the special attention and material rewards that the ill sister or brother is receiving. Because they are also unable to differentiate causes for separation of the parents and ill child, they may fear that the parents will never return. If they should learn that the ill child may not get well or come home, they may interpret this to mean that the parents will also never return. Their greatest fear concerning death is separation from parents (Silverman, 2000). Asking repeated questions; complaining about stomachaches, headaches, and other physical symptoms; displaying intensified fears and emotional outbursts; and showing signs of regression are common behavioral responses to death among preschoolers. They may appear indifferent about the death of a sibling, but this is a normal response related to their limited coping abilities. Play provides the preschooler with relief from the feelings of grief, but unknowing caregivers may misunderstand this. Helpful interventions for preschoolers include minimizing separation from parents; clarifying misconceptions of illness and death as punishment; using accurate, simple language repeated as often as the child needs; and providing the opportunity to play (Ethier, 2008; Speece and Brent, 1996).

School-Age Children

Although school-age children have a better understanding of causality, less egocentricity, and an advanced perception of time, they may still associate misdeeds or bad thoughts with causing death and feel intense guilt and responsibility for the event. However, because of their higher cognitive abilities, they respond well to logical explanations and comprehend the figurative meaning of words better than children in younger age-groups. Although they are less likely to interpret explanations in a purely literal sense, they are still prone to self-referenced definitions. For this reason, it is important for adults to clarify the meanings of statements and to repeatedly ask the children what they think.

Concept of Death: Much of the discussion on the preschool child’s understanding of death also relates to the younger school-age child. However, these children have a deeper understanding of death in the concrete sense. According to Nagy (1948), children of this age attempt to ascribe a more comprehensible meaning to the event by personifying death as a devil, God, ghost, or bogeyman. Naturalistic-physiologic explanations of why death occurs and what happens to the dead body may also be a preoccupation in this age-group. Factual explanations, such as, “When you die, your body decays in the ground,” are consistent with their concrete thinking.

By age 7 years, most children have an increasingly adult concept of death. They realize that it is universal, irreversible, and nonfunctional. Some studies suggest that children with cancer gain a more mature, biologic understanding of death at an earlier age than their well peers (Silverman, 2000). Their attitudes toward death are greatly influenced by the reactions and attitudes of others, particularly their parents.

Reactions to Dying: The increased ability of school-age children to comprehend and reason poses additional risks for them. They may fear the reason for the illness, communicability of the disease to themselves or others, consequences of the disease on their functioning and relationships with others, and the process of dying and death itself. They tend to fear the expectation of the event more than its realization. Their fear of the unknown is greater than that of the known. Like preschoolers, their fantasy explanations for the unexpected or the unknown are usually much more frightening and extreme than the actual situation. For this reason, anticipatory preparation is both necessary and effective. These children respond well to explanations of the disease, names of drugs, and so on. The developmental task of this age is industry; thus helping children who may be facing their own death to maintain control over their body—by understanding what is happening to them and participating in what is done to them—allows them to achieve independence, self-worth, and self-esteem and to avoid a sense of inferiority.

The realization of impending death or failure to recover is a tremendous threat to school-age children’s sense of security and ego strength. These children are likely to exhibit their fear more through verbal uncooperativeness. Health care professionals may erroneously interpret this behavior as rude, impolite, insolent, or stubborn. In reality the words are conveying the same meaning as physical attempts to run away or fight off others. This verbal “flight or fight” reaction to stress is a plea for some control and power. Additional behavioral responses for the well sibling may include worrying about the health and safety of other family members and having problems in school. Encouraging children to talk about their feelings, allowing control where possible and appropriate, and providing outlets for aggression through play are means of dealing with this expression of anger and fear.

Adolescents

By the time most children reach adolescence, they have a mature understanding of death. As abstract thinking develops, there is more questioning of death and related topics, such as the religious meaning of afterlife. However, other developmental needs, especially formation of the child’s own identity, make this an exceptionally difficult time for young people to cope with the loss of a loved one or with their own impending death.

Concept of Death: Although adolescents have a mature understanding of death, they tend to think they will not die as a young person. The search for the spiritual meaning of what follows death is typical at this age.

Reactions to Dying: Adolescents may have a great deal of difficulty in coping with death. Although they have reached the level of adult comprehension of the concept of death, they are least likely of all age-groups to accept cessation of life, particularly their own. Developmentally, the rejection of death is understandable because adolescents’ tasks are to establish an identity by finding out who they are, what their purpose is, and where they belong. Any suggestion of being different or of not being is a tremendous threat to this task.

Adolescents strive for group acceptance and independence from parental constraints. As a result, they rely on peer rules and beliefs for personal direction and reject opposing parental demands. However, when faced with the crisis of serious illness, they may consider themselves alienated from peer associations and unable to communicate with their parents for emotional support. Therefore they may feel virtually alone in their struggle. Support groups or other means of networking with adolescents facing death may be useful.

Healthy adolescents must deal with several maturational crises, such as the acceptance of bodily changes and socialization of intensifying sexual impulses. Any threat to either task increases their vulnerability to the stress of coping with such crises. The devastation of a terminal illness and the effects of chemotherapy may be greater concerns than the prospect of dying. Adolescents’ orientation to the present compels them to worry about physical changes even more than the prognosis for future recovery.

Nurses are in a key position in working with terminally ill adolescents. In the hospital setting they spend the greatest amount of time with them. They can structure the hospital admission to allow for maximum self-control and independence while allowing the adolescent the opportunity to get to know the nurse. Answering adolescents’ questions honestly; treating them as mature individuals; and respecting their needs for privacy, solitude, and personal expressions of emotions such as anger, sadness, or fear convey to adolescents the adult’s true concern for their physical and emotional welfare. Nurses can help parents to communicate with adolescents by providing information on typical adolescent responses and coping patterns; acting as role models; avoiding alliances with either parent or child; and allowing parents the opportunity to vent their feelings of frustration, incompetence, or failure in an atmosphere of acceptance and without judgment (see Box 23-3).

Delivery of Palliative Care Services

Once the health care team and family have discussed the likelihood of death as the outcome of a child’s medical condition or illness, it is necessary to determine the child and family’s preference for the location of palliative care. The circumstances of the child’s illness may influence the location in which palliative care is provided. For instance, traumatic injury or acute illness often leads to death in the emergency department or intensive care unit setting. Children with progressive chronic illnesses or disabilities may initially receive palliative care services through a coordination of services between outpatient visits to their primary physician and care provided by a community agency (home health or hospice) in the home. As the illness progresses, the family may cease to come to the clinic or hospital and depend solely on care provided at home by the community agency as directed by the primary physician. Regardless of the circumstances of the illness or the location of care, it is important to focus on interventions that address all aspects of the child’s and family’s comfort. This requires attention to the child’s physical comfort and the social, emotional, and spiritual needs of the child and family. Based on the decision by the child and family regarding their wishes for care, the family has several options from which to choose.

Hospital

Families may choose to remain in the hospital to receive care if the child’s illness or condition is unstable and home care is not an option, or the family is uncomfortable with providing care at home. If a family chooses to remain at the hospital for terminal care, make the setting as homelike as possible. Families can bring familiar items from the child’s room at home. In addition, develop a consistent and coordinated care plan for the child’s and family’s comfort.

Home Care

Some families may prefer to take their child home and receive services from a home care agency. Generally, these services entail periodic nursing visits, medications, equipment, and supplies. The primary physician continues to direct the child’s care (Ferrell and Coyle, 2002). Physicians and families often choose home care because of the traditional view that a child must be considered to have a life expectancy of fewer than 6 months to be referred to hospice care. Fortunately, a number of hospice organizations are expanding their services to children, basing admission on the presence of a life-limiting disease process for which cure is not possible, rather than on the sole criterion of a limited 6-month prognosis. Dussell, Kreicbergs, Hilden, and colleagues (2008) found parents whose children received home care had honest, open, end-of-life communication from the physician. Parents, were more likely to plan the location of their child’s death as the home and to report favorable outcomes. Unfortunately, only a limited number of hospitals and hospices in the United States provide palliative end-of-life care for children (Johnston, Nagel, Friedman, et al, 2008).

Hospice Care

Hospice care is another option for families who wish to take their child home during the final phases of an illness. Hospice is a community health care program that specializes in the care of dying patients by combining the hospice philosophy with the principles of palliative care. Hospice philosophy regards dying as a natural process and views the care of dying patients as including management of the physical, psychologic, social, and spiritual needs of the patient and family. A multidisciplinary group of professionals provide care in the patient’s home or an inpatient facility that follows the hospice philosophy. Hospice care for children was introduced in the 1970s (Martinson, 1993), and a number of community hospice organizations now accept children into their care (Faulkner and Armstrong-Dailey, 1997).* Collaboration between the child’s primary treatment team and the hospice care team is essential to the success of hospice care. Families may continue to see their primary care physicians as they choose.

The goal of hospice care is for children to live life to the fullest without pain, with choices and dignity, in the familiar environment of their homes, and with the support of their families. Hospice care is covered under state Medicaid programs and by most insurance plans. The service provides home nursing visits and visits from social workers, chaplains, and, in some cases, physicians. For children, the hospice concept has most commonly been implemented in the home, which benefits the family in a variety of ways. Children who are dying are allowed the opportunity to remain with those they love and with whom they feel secure. Many children who were thought to be in imminent danger of death have gone home and lived longer than expected. Siblings can feel more involved in the care and often have more positive perceptions of the death. In addition to the care and support provided through the dying process to the child and family, hospice is concerned with the family’s postdeath adjustment, and bereavement care may continue for a year or more.

Parental adaptation may be more favorable, as is shown by their perceptions of how the experience at home affected their marriage, social reorientation, religious beliefs, and views on the meaning of life and death.

If the home is chosen for hospice care, the child may or may not die in the home. One study revealed that 55% of children enrolled in hospice died in the home (Knapp, Shenkman, Marcu, et al, 2009). Reasons for final admission to a hospital vary but may be related to the parents’ or siblings’ wish to have the child die outside the home; exhaustion on the part of the caregivers; and physical problems such as sudden acute pain or respiratory distress.

Location and Participation in Child’s Care

The location of the child’s terminal care and death and the participation of parents in their child’s terminal care influences parental bereavement. Parents whose child died in the home rather than the hospital setting and who participated in caring for their child have consistently reported better bereavement outcomes (e.g., adaptive coping; family cohesion; less anxiety, stress, and depression) than parents whose children died in the hospital setting and/or who were not actively involved in their child’s care (Goodenough, Drew, Higgins, et al, 2004; Lauer, Mulhern, Schell, et al, 1989; Rando, 1983). The grief work of fathers in particular seems to be facilitated when their children die in the home setting. This finding may be related to the greater opportunity for working fathers to provide care to and spend time with their children at home than in the hospital setting. In contrast, a recent study suggests that parental opportunity to plan the location of their child’s death, whether death occurred in the home or in the hospital, may be a more relevant outcome variable than the child’s actual location of death (Dussell, Kreicbergs, Hilden, et al, 2008).

Nursing Care of the Child and Family at the End of Life

Management of Pain and Suffering

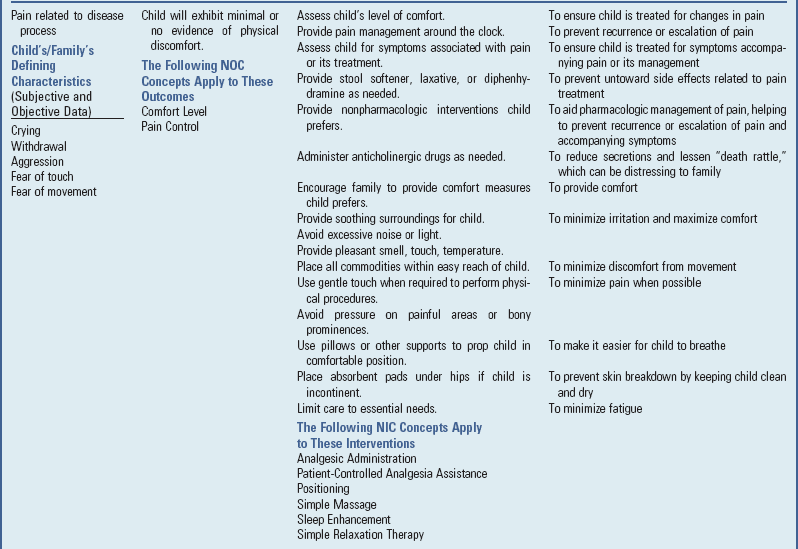

![]() The presence of unrelieved pain and other distressing symptoms in a terminally ill child, unfortunately, are commonly reported (Hendricks-Ferguson, 2008; Pritchard, Burghen, Srivastava, et al, 2008; Zhukovsky, Herzog, Kaur, et al, 2009). Distressing symptoms can have detrimental effects on the child’s quality of life and long-lasting negative effects on the family after the child’s death. Parents have reported that having their child in pain was unendurable and resulted in feelings of helplessness and a sense that they must be present and vigilant to get the necessary pain medications (Ferrell, 1995). Persistent pain also has an impact on the family as a whole. Nurses can alleviate the fear of pain and suffering by providing interventions aimed at treating the pain and symptoms associated with the terminal process in children.

The presence of unrelieved pain and other distressing symptoms in a terminally ill child, unfortunately, are commonly reported (Hendricks-Ferguson, 2008; Pritchard, Burghen, Srivastava, et al, 2008; Zhukovsky, Herzog, Kaur, et al, 2009). Distressing symptoms can have detrimental effects on the child’s quality of life and long-lasting negative effects on the family after the child’s death. Parents have reported that having their child in pain was unendurable and resulted in feelings of helplessness and a sense that they must be present and vigilant to get the necessary pain medications (Ferrell, 1995). Persistent pain also has an impact on the family as a whole. Nurses can alleviate the fear of pain and suffering by providing interventions aimed at treating the pain and symptoms associated with the terminal process in children.

![]() Nursing Care Plan—The Child Who is Terminally Ill or Dying

Nursing Care Plan—The Child Who is Terminally Ill or Dying

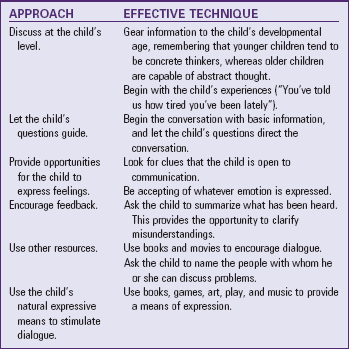

Pain and Symptom Management

When the pain and symptoms experienced by dying children are being managed, it is important to clearly communicate the intent of any interventions proposed. For example, many children with progressive cancer may be given “palliative chemotherapy” or “palliative radiotherapy.” The health care team and family must understand that the goal of these treatments is either to increase comfort by slowing the progression of an incurable tumor (palliative chemotherapy) or to reduce swelling or pressure from a tumor that is causing pain (palliative radiation). The family should understand that these treatments will not ultimately change the outcome of death for the child. This understanding reduces the chance of confusion among family members and health care providers regarding the focus of care and its aim toward palliation. In addition, providers consider the benefit versus risk of any suggested interventions in relation to the child’s current quality of life.

The child’s and family’s views of quality of life, religious and cultural values, and level of acceptance of the terminal prognosis will shape the types of interventions considered as symptoms occur. One family may choose to continue blood-product support if the child is otherwise comfortable and active but has fatigue and shortness of breath related to anemia. Another child and family may forgo transfusions to avoid having to return to the hospital or clinic. The child and family should be aware of potential side effects of any proposed treatments and consequences of choosing not to intervene and are provided with options that are consistent with their values and goals for the child’s comfort. Health care practitioners must respect each individual family’s choice regarding their child’s care.

Nurses should use a holistic approach to symptom management that includes pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic interventions when possible to optimize treatment. For instance, in addition to giving lorazepam for anxiety, instruct the child and family in nonpharmacologic techniques such as distraction or relaxation breathing and encourage them to explore and communicate fears to further alleviate feelings of anxiety.

Carefully consider the route of medication administration used for pain and symptom management. Generally the nurse should use the least traumatic method of administration. Children may present a special challenge for administration of medication depending on their age, level of cooperation, and temperament. If taking medicine becomes a struggle, children and parents may underreport the severity of pain and symptoms to avoid the trauma of administering the medication. Most medications can be administered orally, sublingually, transdermally, or by intravenous or subcutaneous infusion. Compounding pharmacists can be helpful in making medications in a form that is palatable or can be delivered with less distress.

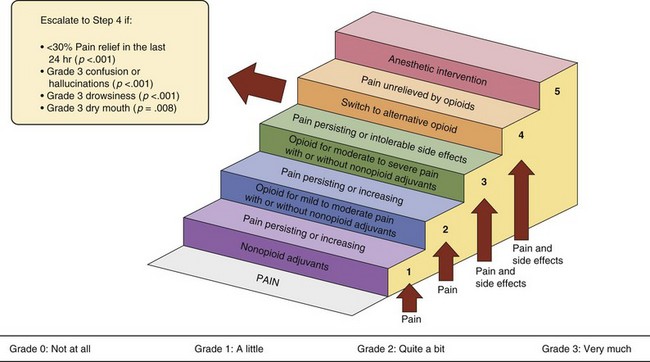

Give pain control for children in the terminal stages of illness or injury the highest priority. Despite ongoing efforts to educate physicians and nurses on pain management strategies in children, studies have reported that children continue to be undermedicated for their pain (Wolfe, Grier, Klar, et al, 2000; Wolfe, Hammel, Edwards, et al, 2008). Nearly all children experience some amount of pain in the terminal phase of their illness. The current standard for treating children’s pain is according to the World Health Organization’s analgesic and side effect stepladder (World Health Organization, 1998b), which takes into account the intolerable side effects of opioids (Riley, Ross, Gretton, et al, 2007) (Fig. 23-2). This approach promotes individualizing the pain interventions to children’s level of reported pain. Children’s pain is assessed frequently, and medications adjusted as necessary. Pain medications are given on a regular schedule, and extra doses for breakthrough pain are available to maintain comfort. Opioid drugs such as morphine are given for severe pain, and the dosage is increased as necessary to maintain optimum pain relief. Techniques such as distraction, relaxation techniques, and guided imagery (Lambert, 1999) are combined with drug therapy to provide the child and family with strategies to control pain (Russell and Smart, 2007). (See Chapter 7 for further discussion of pain assessment and management strategies.)

Fig. 23-2 Overview of proposed five-step World Health Organization analgesic and side effect ladder. (From Riley J, Ross JR, Gretton SK, et al: Proposed five-step World Health Organization analgesic and side effect ladder, Eur J Pain [Suppl S]:23-30, 2007.)

Occasionally children require very high doses of opioids to control pain. This may occur for several reasons. The child on long-term opioid pain management can become tolerant of the drug, so more drug must be given to maintain the same level of pain relief. This is not to be confused with addiction, which is a psychologic dependence on the side effects of opioids. Addiction is not a factor in managing terminal pain in children. Other reasons for increasing dosages of opioids include progression of disease and other physiologic causes of pain. It is important to understand that there is no maximum dosage that can be given to control pain. However, nurses often express concern that administering dosages of opioids that exceed those with which they are familiar will hasten the child’s death. The principle of double effect addresses such concerns (Box 23-5). It provides an ethical standard that supports the use of interventions that have the intention of relieving pain and suffering even though there is a foreseeable possibility that death may be hastened (Siever, 1994). In cases in which the child is terminally ill and in severe pain, using large doses of opioids and sedatives to manage pain is justified when no other treatment options are available that would relieve the pain but make the possibility of death less likely (Fleischman, 1998). (See Chapter 7 for an extensive discussion of pain assessment and management.)

In addition to pain, children experience a variety of other symptoms during their terminal course, either as a result of their disease process or as a side effect of medicines used to maintain their comfort (Box 23-6). The underlying disease and previous treatment history will contribute to the types and severity of symptoms the individual child experiences during the dying process. Nurses caring for children who are receiving palliative care for a terminal condition or illness assess frequently for any symptoms that are causing the child physical distress. Assessment includes information regarding the symptom’s onset, severity, duration, and effect on the child’s quality of life.

These symptoms are consistently managed with appropriate medications or treatments and interventions such as repositioning, relaxation, massage, and other measures to maintain the child’s comfort and quality of life. (For further information on pain and symptom management for children, see the Cancer Pain Management in Children [www.childcancerpain.org] and End-of-Life Care for Children [www.childendoflifecare.org] websites.)

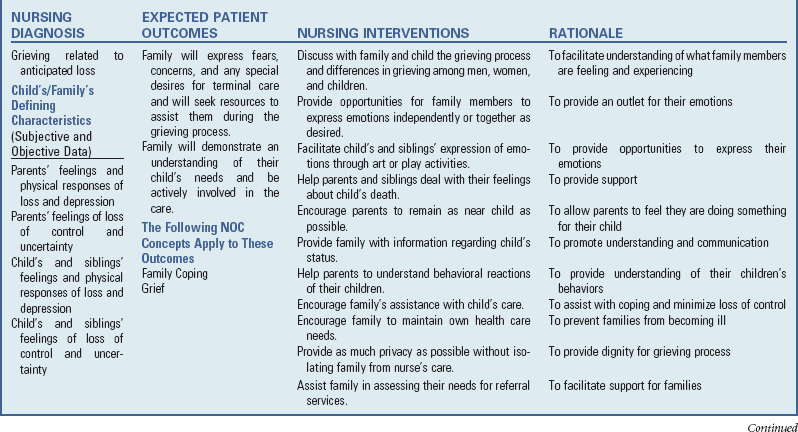

Parents’ and Siblings’ Need for Education and Support Through the Caregiving Process

Often, as the child’s illness worsens, parents and other family members are the primary caregivers while the child is at home. This role can create physical, emotional, and financial strain on the larger family system. Therefore parents and other family members caring for dying children have a number of educational and support needs.

Educational Needs

Family caregivers need comprehensive education about various aspects of the care that they are providing to their child. This preparation can ease feelings of helplessness and anxiety and provide a sense of competence as they move from caring for an ill child to caring for a dying child. This education begins early in the transition from curative to palliative care. Table 23-4 provides some common areas of educational needs of family caregivers and suggestions on how nurses can assist families in meeting these needs. Education about physical care is best provided as the need arises. Instructing parents too early in the signs and symptoms of respiratory distress or the method of stopping a nosebleed can increase the parents’ anxiety.

Emotional Support

Members of the family can be overwhelmed by powerful emotions that can threaten their ability to cope. Anger, guilt, anxiety, and helplessness are normal feelings that many parents experience and often project onto other members of the family or health care team. Nurses assisting these families cannot prevent parents from feeling this way; however, they can assist the family in recognizing the normalcy of these emotions and in identifying ways in which to cope. Encourage families to seek assistance outside of the family circle and to arrange for periods of respite care when available (see Cultural Competence box).

Spiritual and Religious Support

Meeting the spiritual or religious needs of the child and family is as important as teaching caregiving techniques, and the degree to which these needs are met successfully may determine how well the child and family cope with the dying process. It is important for nurses working with dying children and their families to assess the family’s spiritual or religious needs (Heilferty, 2004; National Cancer Institute, 2009), model comfort when discussing the family’s spiritual issues, facilitate the family’s spiritual or religious rituals (e.g., prayer), refrain from disclosing their own beliefs, inform family members of a hospital’s multifaith chapel or quiet area for prayer, note signs of spiritual distress (e.g., “Why my child?”; “Why aren’t my prayers being answered?”), inform family members of the chaplain role, and offer chaplaincy referral (Robinson, Thiel, Backus, et al, 2006). Referral to a hospital chaplain are indicated when a family member requests prayer, sacraments, ritual, devotional materials, or a faith perspective during their process of decision-making; when a family member expresses spiritual or religious objections to the child’s treatment; when a provider notes signs of spiritual distress by a family member; and when a provider observes spiritual or religious solicitation (Robinson, Thiel, Backus, et al, 2006).

Sibling Support

It is important to consider the needs of siblings experiencing the death of a brother or sister (Fig. 23-3). As mentioned earlier, the developmental stage and level of maturity of the siblings will have a strong influence on the feelings and behaviors exhibited as their brother’s or sister’s illness progresses and their care intensifies. Siblings may feel isolated and displaced during the time that a brother or sister is dying (Nolbris and Hellstrom, 2005). Parents devote the majority of their time to the care and comfort of the dying child, which causes siblings to feel left out (Nolbris and Hellstrom, 2005). Siblings may become resentful of their sick brother or sister and begin to feel guilty or ashamed about such feelings (Murray, 1999; Nolbris and Hellstrom, 2005). Nurses can assist the family by helping the parents identify ways to involve the siblings in the caring process and provide honest, developmentally appropriate information to siblings (Giovanola, 2005; Nolbris and Hellstrom, 2005). Encourage parents to spend time with the other children during which the focus is on them. Nurses can assist the parents by helping them identify a trusted friend or family member who can sit with the ill child for a short time.

Caregiver Support

As the care of the dying child becomes the primary focus of the parent, personal and household needs often take on secondary significance. These tasks, however, can become burdensome and increase the family’s stress if not attended to. Nurses can help the family identify ways for friends, community service organizations, and extended family members to assist with tasks such as household chores, shopping, meal preparation, and laundry.

Care at the Time of Death

Few parents have cared for a dying child, and thus parents are not prepared to lead their child through the dying process (Fig. 23-4). Awareness that the child’s death is near allows the parents and family to determine the location and circumstance of the child’s death. This allows the family to create a meaningful death for their child, which improves their ability to cope in the difficult days, weeks, and years after the child has died. Nurses have an important role in helping parents recognize the changes in their child that signal that death may be near (see Nursing Care Guidelines box).

Fig. 23-4 For the dying child there is no greater comfort than the security and closeness of a parent.

Physical Changes

Physical changes occur more often in children dying of prolonged illness or disability and can vary widely among children. Generally, as the child progresses through the dying process, there is an overall decline in the child’s physical condition. This decline may be interspersed with brief spurts of energy or periods of alertness and can cause parents to become exhausted and overwhelmed in “waiting for the inevitable.” Often parents ask “how long” their child has to live. Initially this question may represent the parents’ attempt to determine what special activities or events the family should try to accomplish. As the dying process progresses, this question may reveal a wish to know how long they and their child will have to endure the dying process.

As the child moves closer to his or her actual death, some general physical changes occur (Box 23-7). Initially the child may begin to sleep more. Appetite decreases, and the child begins to take only small bites of favorite foods or sips of fluids. As the child begins to eat and drink less, urinary frequency declines and the urine becomes more concentrated. In the final few days before death, the child most likely becomes less responsive. Breathing may become slow and shallow, with periodic deep sighs. Urinary output may decrease or stop. As the child nears the final hours before death, breathing becomes more irregular, deep, and gasping, with long periods of apnea (Cheyne-Stokes respirations). The skin may have a pale, grayish blue color and may be cool to the touch. The child’s eyes may be slightly open, with a fixed gaze. It is important to prepare the family for these changes and to provide them with caregiving activities that promote a loving presence in the child’s care (Box 23-8). Reassure parents that this is a normal process and that the child is not suffering.

Emotional Changes

As children approach death, they may begin to recall events that were important with their families. They may want to draw pictures or leave messages for important friends and family. Often children begin to reassure their parents and other significant people that they are not afraid and are ready to die.

During the final few days to hours of death, children may experience visions of “angels” or people and talk with them (Ethier, 2005). They may mention that they are not afraid and that someone is waiting for them. Often these visions are of family members or friends who have preceded them in death. In most instances these visions provide a comforting presence and reassurance for the child and family. Not all children will express these types of experiences.

As the child’s death approaches, the family may begin the “death vigil,” which is a natural phenomenon in which family and friends gather at the bedside. Rarely is the child left alone for any length of time. During this time families may read favorite books, recite prayers, light candles, or play music that is special to the child. Spiritual, religious, or family rituals surrounding the time of death are important, and nurses involved in the care of the family at this time are sensitive to such needs (Heilferty, 2004; National Cancer Institute, 2009) (see Nursing Care Plan).

Postmortem Care

The final moments of a child’s life are often extremely stressful as the family waits for the child to die. Families often depend on trusted health care professionals, particularly nurses, to help them recognize the exact moment of the child’s death. Once the nurse has observed that the child is no longer showing signs of life, the child is pronounced dead (registered nurse pronouncement is allowed by the state practice act). Initially the family may show joy and relief that the child is no longer struggling. They may have many varied emotions in the immediate moments after the child’s death, and the nurse must be prepared for a range of reactions. Generally all that is necessary is a supportive presence at this time. In rare instances, particularly in more conflicted families, there may be strong outbursts of anger. It is important for the nurse to be aware of families in which this situation may occur and respond by assuring them that appropriate resources (social worker, chaplain, security personnel) are readily available to ensure that the situation does not escalate.

Once the initial reaction to the moment of death has occurred, the family may move away from the bedside and enter a phase of relaxation. One or both of the parents may stay with the child while others in attendance make brief visits to view the child. Nursing care at this time is to facilitate the parents’ ability to spend time with their child as they wish. Allow the family the time needed to say good-bye.

When the parents are ready, the nurse offers to bathe and dress the body for removal from the home or hospital room. The parents may wish to undertake this task, may participate with the nurse, or may ask the nurse to do the bathing for them. If the death was at home and the body is prepared for removal and the parents are ready, contact the funeral home. Often hospice organizations have arrangements with the medical examiners in their area that allow the body to be directly removed by a funeral director. In some instances it may be necessary for the police to make a report before the release of the child’s body. It is important for the nurse to explain to the parents the requirements of their local area for removal of a body. This allows the parents to be prepared for questions or information that may be required. Hospital deaths require the parents to leave the child, and the body is taken to the morgue. Some parents may ask to go with the body to the morgue, and nurses work within their institutions’ regulations to try to honor such requests if possible.

The final separation of the child’s body from the parents and family is often the most emotional and traumatic time. The nurse should offer support to the parents and ensure that other family members or friends are available in the coming hours to continue to provide support and assistance to the parents and siblings.

Care of the Family Experiencing Unexpected Childhood Death

In cases of long-term, potentially fatal illnesses, families may experience anticipatory grief. Parents mourn the loss of their child long before the death. They are reminded of their child’s uncertain future each time they see the pain the child must endure or experience the sudden loss of hope during a relapse. This prolonged period of anticipatory grief provides families with the opportunity to complete “unfinished business,” such as helping the child and siblings understand and cope with a fatal prognosis. Many families reflect on their changed perspective of time after learning of the diagnosis, particularly their heightened awareness of the value of each day.

In contrast, after sudden, unexpected death, the family is deprived of any of the advantages of anticipatory grief. They have no opportunity to prepare themselves or others for the death, and the initial denial may be very strong. Many families feel great guilt and remorse for not having done something additional or different with the child. For example, they may berate themselves for depriving the child of some desired material object or privilege or, more painfully, for not having prevented the sudden death in some way. “If only I’d been a better parent” is a common feeling at this time. Without proper support, the risk of complicated grief responses may be high (Oliver and Fallat, 1995; Rando, 1993). Mothers experiencing the sudden, unexpected death of their child have reported a more prolonged grief response compared with mothers who anticipated their child’s death (Seecharan, Andresen, Norris, et al, 2004).

Death resulting from accident or trauma or from acute illness in settings such as the emergency department or intensive care unit often requires the active withdrawal of some form of life-supporting intervention, such as a ventilator or bypass machine. These situations often raise difficult ethical issues (Savage, 1997), and parents are often less prepared for the actual moment of death (Box 23-9). Nurses can assist parents by providing detailed information about what will happen as supportive equipment is withdrawn, ensuring that appropriate pain medications are administered to prevent pain during the dying process, and allowing the parents time before the start of the withdrawal to be with and speak to their child. It is important that the nurse attempt to control the environment around the family at this time by providing privacy; asking if they would like to play music; softening lights and monitoring noises; and arranging for any spiritual, religious, or cultural rituals that the family may want performed. After the child’s death, the family is allowed to remain with the body and hold or rock the child if they desire. Once the nurse has removed all tubes and equipment from the body, give parents the option of assisting with the preparation of the body, such as bathing and dressing.

Community-Based Follow-Up

A community health or visiting nurse referral may be helpful after a sudden, unexpected pediatric death. Some families have reported that this was a missing piece in their care (Dent, Condon, Blair, et al, 1996). During several home visits the nurse can answer the families’ questions, provide information about the grief process, assess and support coping mechanisms, and give appropriate referrals to support groups (Box 23-10) (Buckalow and Esposito, 1995).

Families who experience a child’s sudden death may have recurrent memories of both the child and the death experience and may long grieve over missed opportunities. Support and resource groups that may be useful to families include the First Candle (previously SIDS Alliance),* National Sudden and Unexpected Infant/Child Death and Pregnancy Loss Resource Center,† American SIDS Institute,‡ Mothers Against Drunk Driving,§ and National Organization of Parents of Murdered Children, Inc.

Special Decisions at the Time of Dying and Death

Rarely are people prepared to cope with the numerous decisions that must be made when a loved one is dying or dies. When the death is expected, there is the opportunity to make plans in advance, such as where the child should spend the last days or what type of funeral arrangements are desired. When death is unexpected, the shock is sufficient to render the survivors incapable of making even simple decisions. Those in attendance at the death and those caring for the dying child can be instrumental in initiating decisions that may facilitate the grief process. The following is a brief review of selected instances in which nurses can guide parents in making decisions related to the expected or unexpected death.

Right to Die and Do-Not-Resuscitate Orders

One of the benefits of hospice has been the recognition of patients’ right to die as they wish, with emphasis on the quality of life. Unfortunately, this is not always the focus of care, especially in the traditional hospital setting. Many families are not given the option of terminating treatment when cure is unlikely, and staff may be reluctant to raise the question of “no code” or DNR orders (withholding cardiopulmonary resuscitation in response to cardiac arrest).

Guidelines have been established for discontinuing mechanical ventilation and life-support measures for infants whose parents and providers consider care futile (De Lisle-Porter and Podruchny, 2009; Sine, Sumner, Gracy, et al, 2001). Such plans must carefully encompass preplanning, educational, discharge, and postextubation procedures and the needs of the family and health care staff and unit. If parents choose DNR, they must be aware of exactly what will and will not be done for the child and be assured that this does not mean “no care.” For example, the family may wish that oxygen be given to the child for difficult breathing but does not want active resuscitation. Once a decision is made, it must be communicated to all members of the health team, and a written medical order for the use or withholding of lifesaving measures must be included. An order to “slow” or “delay” code is not legal. Because the child’s condition or the family’s wishes may change, review DNR orders regularly. Respect orders even if it is difficult to follow them at the moment of death (Martinson, 1995).

Viewing of the Body

Although most institutions recognize the need for parents to hold and spend time with the dead child, a dilemma may arise when the body is mutilated. Although the memory of the child’s disfigurement can be extremely upsetting and can generate concern regarding how much the child suffered, not seeing the body can leave the parents with imagined ideas of how their child looked that can be worse than the reality and can delay the acceptance of the death. When family members choose to view the body, they need preparation for this upsetting experience. The nurse should inform them about what to expect and why certain parts of the body are covered or bandaged. It is desirable to place the body in a private room, without medical apparatus, and make it as presentable as the situation allows. Some people appreciate the presence of a nurse in the room with them; others desire privacy. Regardless of how badly the body is harmed, parents may want to hold the child. Offer and respect such options. Give family members as much time as they need to say good-bye; for many, viewing the body is a sign of closure—an opportunity to finish their good-byes and leave the hospital.

Organ or Tissue Donation and Autopsy

Many states have legislated a mandatory request for organ or tissue donation when a child dies. For some families this may be a meaningful act—one that benefits another human being despite the loss of their child. Unfortunately, initiating a discussion about tissue donation is often stressful for staff, and there may be confusion regarding whose responsibility this is. In centers in which transplants are performed, a full-time transplant coordinator is usually available to inform the family about organ donation and to take care of details. If such services are not available, the staff determines which members should discuss this topic with the family. Ideally the person who knows the family best, knows when the death is expected, or has the opportunity to spend time with the family when the death is unexpected takes the role. Often nurses are in an optimum position to suggest tissue donation after consultation with the attending physician. When possible, the topic is raised before death occurs. Make the request in a private and quiet area of the hospital. Be simple and direct, with questions such as, “Are you a donor family?” or “Have you ever considered organ donation?”

Written consent from the family is required before donation can proceed. When requests for organ donation are made, health care practitioners must address common misunderstandings families have about brain death and organ donation (Bellali and Papadatou, 2007; Franz, DeJong, Wolfe, et al, 1997). Training of health care professionals regarding sensitive approaches to request organ donation has shown to increase families’ willingness to consent to organ donation (Bellali and Papadatou, 2007; Evanisko, Beasley, Brigham, et al, 1998). Discussion of the option to donate organs is always separate from communication of impending or actual death.

Nurses need to be aware of common questions about organ donation so they can help families make an informed decision. Healthy children who die unexpectedly are excellent candidates for organ donation. Children who have cancer, chronic disease, or infection or who have suffered prolonged cardiac arrest may not be suitable candidates, although this is individually determined. The nurse inquires whether organ donation was discussed with the child or whether the child ever expressed such a wish. Any number of body tissues or organs can be donated (skin, corneas, bone, kidney, heart, liver, pancreas), and their removal does not mutilate or desecrate the body or cause any suffering. The family may have an open casket, and there is no delay in the funeral. There is no cost to the donor family, but organ donation does not eliminate funeral or cremation responsibilities. Most religions permit organ donation as long as the recipient benefits from the transplant, although Orthodox Judaism forbids it.

In cases of unexplained death, violent death, or suspected suicide, autopsy is required by law. In other instances it may be optional, and the nurse should inform parents of this choice. Explain the procedure, as well as forms that require signing. Inform the family that the child can be in an open casket following an autopsy.

Siblings’ Attendance at Funeral Services

One of the most frequent concerns of parents is whether young or school-age children should attend funeral or burial services (see Research Focus box). Sharing moments of deep significance with parents helps children understand the experience and deal with their own feelings, and depriving them of this opportunity may leave children with lifelong regrets (Fig. 23-5). However, a child is never to be forced to attend a postdeath service. Children need preparation for postdeath services (Pearson, 2005). They should be told what to expect, particularly how the deceased person will look if the coffin is open. Ideally a parent explains the details to the child; if the parent’s grief prevents this communication, a significant family member or friend should substitute.

Fig. 23-5 Drawing made by a 7-year-old child whose sister died in a car crash. The drawing shows the boy sad and crying (dots are tears) because he was not allowed to see his dead sibling.

It is often helpful to bring children to the funeral service before many visitors arrive. They are allowed private time to say good-bye but are spared some of the unpredictable emotional reactions of others, which can be distressing to them. Children are allowed to stay as long as they wish, but respecting their need to leave provides maximum control for them over their ability to grieve comfortably (see Family-Centered Care box).

Care of the Grieving Family

No event is more devastating for families than the threatened or actual loss of a child. Families, especially parents, are deprived of the joy and fulfillment of watching a child grow. All family members are affected by the loss, and their needs must be recognized to facilitate their grief process.

In expected death the child and family are generally involved in the plan for interventions both before and after the death. In unexpected death the survivors face the tremendous task of integrating the loss into their lives, with no opportunity for anticipatory grief. In either situation nurses can facilitate the grief process by having a basic understanding of the process; being aware of expected reactions; talking with family members; ascertaining their needs; and supporting their efforts to cope, adapt, and grieve (see Nursing Care Guidelines box). Applying the principles of family-centered care is as important at this time as at any other.

Grief

Grief is a process, not an event, of experiencing physiologic, psychologic, behavioral, social, and spiritual reactions to the loss of a child (Rando, 1993). Grief is highly individualized, encompassing a broad range of manifestations from person to person. It is a natural and expected reaction to loss. It is neither orderly nor predictable. Grieving in any form is necessary for healing to occur. When death is the expected or a possible outcome of a disorder, the child and family members may experience anticipatory grief. Anticipatory grief may be manifested in varying behaviors and intensities and may be characterized by denial, anger, depression, and other psychologic and physical symptoms (Rando, 1986). Anticipatory guidance may assist grieving family members. Health care professionals emphasize that grief reactions such as hearing the dead person’s voice, feeling distant from others, or seeking reassurance that they did everything possible for the lost person are normal, necessary, and expected. These reactions in no way signify poor coping, insanity, or an approaching mental breakdown. On the contrary, such behaviors signify that the survivor is working through the acute grief. They are a necessary part of grief work. Anticipatory guidance regarding the mourning process may be helpful to families so that they can recognize the normalcy of their experiences.

It is important to recognize that some family members may experience “complicated” grief. Complicated grief reactions (those that continue more than a year after the loss) include such symptoms as intense intrusive thoughts, pangs of severe emotion, distressing yearnings, feelings of being excessively alone and empty, unusual sleep disturbance, and maladaptive levels of loss of interest in personal activities (Horowitz, Siegel, Holen, et al, 1997). An unexpected, sudden death is a risk factor for complicated grief (Keesee, Currier, and Neimeyer, 2008). Bereaved persons experiencing such prolonged and complicated grief are referred to an expert in grief and bereavement counseling.

Parental Grief