Behavioral Health Problems of Adolescence

http://evolve.elsevier.com/wong/ncic

Childhood Depression, Ch. 18

Childhood Mortality, Ch. 1

Cocaine Exposure, Ch. 10

Communicating with Children, Ch. 6

Drug-Exposed Infants, Ch. 10

Environmental Tobacco Smoke Exposure, Ch. 32

Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder, Ch. 10

Health Promotion of the Adolescent and Family, Ch. 19

Infants of Mothers Who Smoke, Ch. 10

Nutritional Assessment, Ch. 6

Adolescence is a significant period of transition from childhood to young adulthood. This is the period when the precepts that govern the person’s life in adulthood are established. Adolescents may find it difficult to cope with the inward conflict of becoming independent from parental support and rules yet at the same time meeting expectations imposed by peers and society. This chapter focuses on conditions that adolescents may be facing that have a profound effect on their lives as adults. As health care providers, nurses can have a significant impact in helping adolescents make an effective transition to adulthood.

Obesity

![]() The growth and development that occurs during adolescence can affect youth’s interaction with food, nutrition, and physical activity.

The growth and development that occurs during adolescence can affect youth’s interaction with food, nutrition, and physical activity.

![]() Critical Thinking Exercise—Obesity

Critical Thinking Exercise—Obesity

![]() Few health problems in adolescence are so obvious to others, are so difficult to treat, and have such long-term effects as obesity. It is the most common nutritional disturbance of children and one of the most challenging contemporary health problems at all ages.

Few health problems in adolescence are so obvious to others, are so difficult to treat, and have such long-term effects as obesity. It is the most common nutritional disturbance of children and one of the most challenging contemporary health problems at all ages.

![]() Critical Thinking Case Study—Obesity

Critical Thinking Case Study—Obesity

In a 2001 report the U.S. surgeon general stated that in the year 2000 the total annual cost of obesity in the United States was $117 billion (US Surgeon General, 2001). The direct health costs of childhood overweight can only be estimated, since the major impact is likely to be felt in the next generation (Lobstein, Baur, and Uauy, 2004). However, reports indicate that for the first time in U.S. history, the current generation of children will have a shorter life expectancy than their parents (Olshansky, 2005).

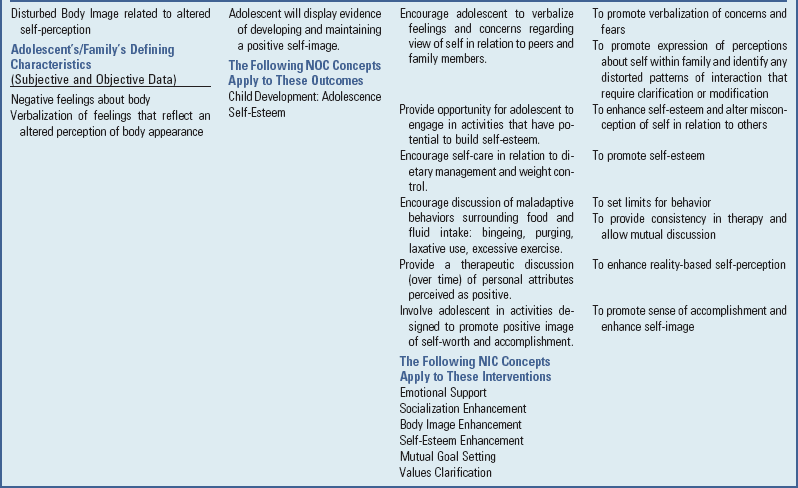

Approximately 12.5 million children are overweight or obese (Ogden, Carroll, and Flegal, 2008). Numerous studies dating back to the early 1960s have documented childhood overweight through comprehensive evaluations of dietary intake, physical activity, and anthropometric measures (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention using the various National Health Examination Surveys [NHANES], I, II, III, and IV) (Ogden, Carroll, and Flegal, 2008; Ogden, Kuczmarski, Flegal, et al, 2002; Ogden, Troiano, Briefel, et al, 1997). In children ages 6 to 11 years the prevalence of childhood overweight remained fairly constant in between 1963 and 1974 at approximately 4% and 5.5%, respectively. However, recent NHANES surveys have seen those numbers steadily climb to reach 17% in both 6- to 11-year-olds and 12- to 19-year-olds (Ogden, Carroll, and Flegal, 2008) (Fig. 21-1). African-American and Hispanic children youth are disproportionately represented by a higher prevalence of overweight and obesity (23.1% and 21.0%, respectively) when compared with non-Hispanic Caucasian children (15.9%) (Ogden, Carroll, and Flegal, 2008). A study of 9464 Native American schoolchildren ages 5 to 18 years found that 39% were overweight, and a further review of tribes across the United States found that 30% to 46% of Native Americans were at risk for overweight (Hardy, Harrell, and Bell, 2004).

Fig. 21-1 Increasing incidence of overweight in children (National Health Examination Survey [NHANES] 1963-2000). Data collected using measured height and weight. The y-axis signifies the percent of obese children, overweight being defined as ≥95th percentile of age- and sex-specific body mass index.

Because adult obesity is associated with increased mortality and morbidity from a variety of complications, both physical and psychologic, adolescent obesity is a serious condition. Overweight children and adolescents are at risk of continuing to be obese as adults, thereby experiencing the health and social consequences of obesity much earlier than children and adolescents of normal weight. Parental obesity increases the risk of overweight by twofold to threefold (Baker, Barlow, Cochran, et al, 2005). The probability that overweight school-age children will become obese adults is estimated at 50%, whereas the likelihood that overweight adolescents will become obese adults is estimated at 70% to 80% (National Institute for Health Care Management Foundation, 2003).

Obesity in childhood and adolescence has been related to elevated blood cholesterol, high blood pressure, asthma and other respiratory tract disorders, orthopedic conditions, cholelithiasis, some types of adult-onset cancer (MacKenzie, 2000), nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (Baker, Barlow, Cochran, et al, 2005; Lavine, 2000; Angulo, 2002), and an increase in type 2 diabetes mellitus (Fagot-Campagna, Narayan, and Imperatore, 2001; Ehtisham, Barrett, and Shaw, 2000; Must and Anderson, 2003).

Overweight refers to the state of weighing more than average for height and body build. Overweight status is defined as an age- and gender-specific body mass index (BMI) between the 85th percentile and the 94th percentile based on the 2000 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Growth Charts for the United States. Obesity is defined as an age- and gender-specific BMI at or above the 95th percentile for children of the same age and sex (US Preventive Services Task Force, 2010). Obesity is an increase in body weight resulting from an excessive accumulation of body fat relative to lean body mass (Barlow and Expert Committee, 2007).

Currently, the BMI measurement is recommended as the most accurate method for screening children and adolescents for obesity by the Expert Committee on Pediatric Obesity (Barlow and Expert Committee, 2007), the US Preventive Services Task Force (2010), and the National Institute for Health Care Management Foundation (2003). (See Appendix B.) The BMI measurement is strongly associated with subcutaneous and total body fat and also with skinfold thickness measurements. It is also highly specific for children with the greatest amount of body fat (MacKenzie, 2000). A subset of children may have a high BMI because of increased muscle mass rather than fat mass (Swallen, Reither, Haas, et al, 2005).

Etiology and Pathophysiology

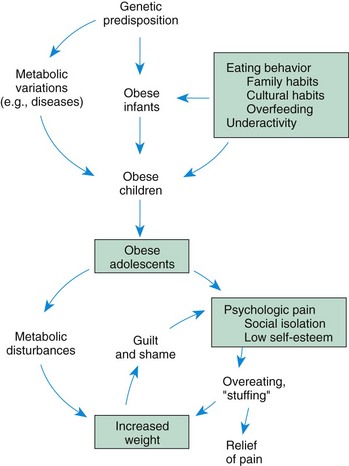

Obesity results from an energy imbalance (i.e., caloric intake that consistently exceeds caloric requirements and expenditure) and may involve a variety of interrelated influences, including metabolic, hypothalamic, hereditary, social, cultural, and psychologic factors. Because the etiology of obesity is multifactorial, the treatment requires multilevel interventions. Fig. 21-2 illustrates an ecological approach to understanding the multitude of risk factors associated with childhood and adolescent obesity. This framework suggests that the dominant factors, such as the availability of fast-food restaurants, may influence food choices of the children and adolescents who live there. An ecological approach helps promote a better understanding of the role that institutional, community, and societal factors play in the development of children’s eating practices and activity levels, thereby taking some of the blame off children for their overweight (Neumark-Sztainer, 2003).

Birth weight does not seem to be a long-term contributing factor in detection and prediction of childhood obesity (Kain, Corvalán, Lera, et al, 2009). There is, however, a high correlation between childhood adiposity and parental adiposity (Li, Kaur, Choi, et al, 2005; Boney, Verma, Tucker, et al, 2005; Bouchard, 2009).

Energy Balance: A balance between energy intake and energy expenditure is a critical factor in regulating body weight. Factors that raise energy intake or decrease energy expenditure by even small amounts can have a long-term impact on the development of overweight and obesity. For example, a positive balance of one serving of a sweetened juice or soft drink (about 120 kcal) per day would produce a 50 kg (110 lb) increase in body mass over a 10-year period (Hill, Wyatt, Reed, et al, 2003).

Genetic Factors: Familial influence is an epidemiologic consideration in regard to a child weight. Twin studies suggest that approximately 35% to 50% of the tendency toward obesity is inherited (Beaty, 2007). Twin studies have also suggested that this tendency is a combination of genetic and environmental factors. Mothers seem to play a greater role in the gestational weight of a child (Jaquet, Swaminathan, Alexander, et al, 2005). When both parents are obese, there is a 60% to 80% increase in the likelihood of the child becoming obese (Koeppen-Schomerus, Wardle, and Plomin, 2001). The specific influences of genes and environment within the developing child is not well defined. The increasing rates of obesity within genetically stable populations suggest that environmental and some perinatal factors (e.g., bottle-feeding) are contributors to the current increases in childhood obesity (National Institute for Health Care Management Foundation, 2003). More research is needed to better understand the influences of family behavior and adolescent overweight.

Diseases: Fewer than 5% of the cases of childhood obesity can be attributed to an underlying disease. Such diseases include hypothyroidism; adrenal hypercorticoidism; hyperinsulinism; and dysfunction or damage to the central nervous system as a result of tumor, injury, infection, or vascular accident. Obesity is a frequent complication of muscular dystrophy, paraplegia, Down syndrome, spina bifida, and other chronic illnesses that limit mobility.

Several congenital syndromes have obesity as a feature, including Laurence-Moon-Biedl, Prader-Willi, and Alström syndromes and pseudohypoparathyroidism. The most common of these is Prader-Willi syndrome, a disorder characterized by hypogonadism; slow intellectual development; short stature; and dysmorphic facial features, including a narrowed bifrontal diameter, almond-shaped eyes, and triangular mouth. These children are hypotonic and hyperphagic. They lack the internal mechanism that regulates satiety and as a result go to great lengths to obtain food.

Molecular, Metabolic, and Endocrine Factors: Regulators of Appetite: A major focus of obesity research has been appetite and its regulation. The expression of appetite is chemically coded in the hypothalamus by distinctive circuitry. Orexigenic substances produce signals that promote eating behaviors, and anorexigenic substances promote the cessation of eating behaviors. Feedback loops between signals have been identified where one signal peptide is able to alter the secretion of another signal peptide. No one signal has been identified as the gatekeeper of appetite. It is apparent that an entire network of signals, including their frequency and amplitude, is responsible for triggering eating behaviors.

This network of appetite signals explains the behavioral observations that appetite and food consumption patterns are dynamic and influenced by biologic, environmental, and psychologic events. Internal cues such as habitual intake, memories of food-related activities, and anticipation of consumption easily modify human eating behaviors. External cues that modify the perception of appetite include food aroma, appearance, anticipation, and the number food choices (Feldman, Friedman, and Sleisenger, 2002).

Researchers have identified a number of hormones and proteins that regulate appetite and weight in animal models. It is likely that these same mechanisms apply to humans. However, the role of hormones and neurotransmitters in determining overweight in humans remains unknown. Only a small number of enzyme abnormalities and metabolic defects have been identified, and these cannot account for the rapid increase in childhood obesity over the past three decades (Baker, Barlow, Cochran, et al, 2005).

There is little evidence to support a relationship between obesity and “low metabolism.” There may be small differences in regulation of dietary intake or metabolic rate between obese and nonobese children that could lead to an energy imbalance and inappropriate weight gain, but these small differences are difficult to accurately quantify. However, research by Leahy, Birch, Fisher, and colleagues (2008) indicated that children can self-regulate intake when presented with high- and low-calorie food choices. Obese children tend to be less active than lean children, but it is uncertain whether inactivity creates the obesity or obesity is responsible for the inactivity. Obesity in adolescents and children can be caused by overeating, low activity levels, or both. Obese adolescents have actually been found to have higher total daily energy expenditure and resting energy expenditure than nonobese adolescents. This would seem to suggest that obese children need to eat more to maintain their higher weight. No differences in basal metabolic rate, sleeping metabolic rate, respiratory quotient, heart rate, or total energy expenditure have been found in normal weight children with or without a familial predisposition to overweight (Baker, Barlow, Cochran, et al, 2005).

Caloric Equilibrium: Sociocultural Factors: The tendency toward obesity occurs whenever environmental conditions are favorable toward excessive caloric intake, such as an abundance of food, limited access to nutrient-dense foods, reduced or minimum physical activity, and snacking combined with excessive screen (computer, television, video games) time. Family and cultural eating patterns, as well as psychologic factors, play an important role. Some families and cultures consider fat to be an indication of good health, a status symbol, or an indication of affluence. It is not uncommon for obese children to have families that emphasize large portion sizes, admonish children for leaving food on their plates, or use food as a reward or punishment. Parents may not have a concept of the amount of food children require and expect them to eat more than they need.

In countries such as the United States and Western Europe, the prevalence of obesity shows a marked difference between upper- and lower-class children, with differences often becoming apparent before 6 years of age. Lower socioeconomic groups have a greater prevalence of obesity, especially in girls. Sociocultural factors also influence physical activity. Results of a recent study indicate that activity and inactivity patterns differ by ethnicity, and minority adolescents (non-Hispanic African-Americans, Hispanics, and Filipinos) engage in less physical activity and more inactivity than their non-Hispanic Caucasian counterparts (Iannotti, Kogan, Janssen, et al, 2009) (see Cultural Competence box).

Community and Institutional Contributors: Some community factors that influence activity patterns include a lack of a built environment (sidewalks, parks, bike paths) or affordable and accessible facilities for low-income youth to be active, thus limiting their opportunities to participate in physical activities. Social policies also contribute to obesity. The increased availability of energy-dense foods, pricing strategies that promote unhealthy food choices, and overzealous food advertising that targets children and adolescents with high-fat and high-sugar foods are some examples.

Institutional factors also influence patterns of obesity and decreased physical activity. Many school policies allow students to leave school for lunch. Vending machines in school often are filled with high-fat and high-calorie foods and soft drinks. Fast-food restaurants are often allowed to advertise to children in schools. Although well-balanced, nutritious school lunches may be available to students, they will often opt for no lunch or one that is of less nutritious choices such as high-fat and high-sugar snacks.

Physical inactivity has also been identified as an important contributing factor in the development and maintenance of childhood overweight. There is little doubt that physical activity has decreased in elementary and secondary schools in the United States. The percentage of high school students who attended physical education classes daily decreased from 42% in 1991 to 25% in 1995 and remained stable at that level until 2007 (30%). In 2007, 40% of ninth grade students but only 24% of twelfth grade students attended physical education class daily (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2008). Consequently, most of a child’s physical activity must occur within the family or outside of school. Decreased physical activity within the family and community is a powerful influence on children, since children model their parents and other adults.

The growing attraction and availability of many sedentary activities, including television, video games, computers, and the Internet, have greatly influenced the amount of exercise that children get. Children ages 8 and over were found in 2005 to consume an average of an additional hour of media content per day compared with 1999. On average one fourth (26%) of their media use time was spent “media multitasking,” or using more than one medium at a time (Roberts, Foehr, and Rideout, 2006). Cross-sectional studies have shown the association between TV use and obesity among children (Robinson, 2006; Neumark-Sztainer, 2003; Gable, Chang, and Krull, 2007).

Other Influences: Psychologic factors also affect eating patterns. Infants experience relief from discomfort through feeding and learn to associate eating with a sense of well-being, security, and the comforting presence of a nurturing person. Eating is soon associated with the feeling of being loved. In addition, the pleasurable oral sensation of sucking provides a connection between emotions and early eating behavior. Many parents use food as a positive reinforcer for desired behaviors. This practice may become a habit, and the child may continue to use food as a reward, a comfort, and a means of dealing with feelings of depression or hostility. Many individuals eat when they are not hungry or in response to stress, boredom, loneliness, sadness, depression, or tiredness. Difficulty in determining feelings of satiety can lead to weight problems and may compound the factor of eating in response to emotional rather than physical hunger cues.

Meta-analyses of observational studies have found that obesity risk at school age was reduced by 15% to 25% with early breast-feeding compared with formula-feeding (Arenz, Ruckerl, Koletzko, et al 2004; Owen, Martin, Whincup, et al, 2005; Harder, Bergmann, Kallischnigg, et al, 2005). In one of these, one month of breast-feeding was associated with a 4% decrease in risk for obesity (Harder, Bergmann, Kallischnigg, et al, 2005). This effect lasted for up to 9 months of breast-feeding and was independent of the definition of overweight and age at follow-up. Researchers have suggested several possible explanations, including a lower insulinemic response compared with bottle-fed infants, lower energy and protein intake, and ability of breast-fed infants to self-regulate their energy intake from both breast milk and solid foods (Heinig, Nommsen, Peerson, et al, 1993).

Frequency of family meals has consistently been shown to be a protective factor for obesity (Utter, Scragg, Schaaf, et al, 2008; Fulkerson, Neumark-Sztainer, Hannan, et al, 2008). Family meals tend to provide access to a variety of nutrient-rich foods, particularly fruits and vegetables. Family meals also create a forum for increased family communication and connectedness, both of which promote healthy weight behaviors.

Leptin is a hormone synthesized by adipocytes. As adipocytes enlarge, leptin secretion increases; it decreases when the person is fasting. Leptin receptors are located in the hypothalamus. However, the true role of the leptin receptor in human obesity remains obscure (Baker, Barlow, Cochran, et al, 2005). The leptin signal may serve as an anorexin by its ability to alter secretion of orexins and anorexins. Obese individuals have appropriately elevated leptin levels, but it is not clear if this is the result of obesity or if this could relate to a pathologic cause of obesity (Feldman, Friedman, and Sleisenger, 2002). Researchers continue to explore the network of appetite signals and their effects on food consumption and weight.

Complications of Obesity

Adults with longstanding obesity are at risk for medical complications that include hypertension, diabetes, coronary heart disease, stroke, fatty liver disease, and colorectal cancer. Although obesity-related complications occur frequently in adults, children and adolescents are experiencing significant health consequences as well. Health care providers, researchers, and government agencies are beginning to discover that children and adolescents are developing these complications sooner rather than later in adult life. Childhood obesity has become an increasingly important medical problem, resulting in hypertension, type 2 diabetes, pulmonary complications (e.g., asthma, sleep apnea), growth acceleration, dyslipidemia, musculoskeletal problems, fatty liver disease, and a potential for psychosocial problems. Diagnostic evaluations of children and adolescents who are at risk for being overweight and children and adolescents who are overweight have expanded to screen for these complications.

Physical Complications of Obesity:

Insulin Resistance and Type 2 Diabetes: Along with obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus is reaching epidemic proportions in children and adolescents. One out of three newly diagnosed type 2 diabetics are adolescents. Inactivity and obesity influence insulin resistance. Insulin resistance syndrome, also known as syndrome X, is characterized by hyperinsulinemia, obesity, hypertension, and dyslipidemia and develops before any of these conditions develops.

Insulin is necessary for the metabolism of fats, proteins, and carbohydrates and must be present for glucose to enter the fat and muscle cells. Insulin facilitates the storage of glucose in the form of glycogen in the liver and muscle cells and further prevents the mobilization of fat from fat cells. The cell membrane has special receptor sites for insulin. Once the receptor site has been established, a chemical reaction results and glucose enters the cell. If the amount of insulin is inadequate, glucose cannot enter the cell. In response to elevated levels of glucose in the body, the pancreas increases the production of insulin, resulting in hyperinsulinemia. Type 2 diabetes develops when the pancreas is no longer able to lower the blood glucose level by hypersecretion of insulin.

Persons with insulin resistance sometimes have decreased high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels, increased serum very low–density lipoprotein cholesterol, increased triglyceride levels, and increased or sometimes decreased low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels (Rao, 2001; Yensel, Preud’Homme, and Curry, 2004; Bremer, Auinger, and Byrd, 2009).

Fatty Liver Disease: Recently, a growing number of children and adolescents have been diagnosed with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), which has been recognized as one of the leading causes of chronic liver disease in the general population. Children account for approximately 2.5% of the population diagnosed with NAFLD, and between 20% and 77% of these children are considered obese (Imhof, Kratzer, Boehm, et al, 2007). NAFLD is liver damage that ranges from steatosis, steatohepatitis, and advanced fibrosis to cirrhosis. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) is a stage within the spectrum of NAFLD. The pathology of NASH is consistent with that seen in alcohol-induced liver injury, but occurs in persons who have not abused alcohol. NAFLD is the most common reason for elevated aminotransferase levels. It has been estimated that about 25% of obese children have elevated serum aminotransferases. The increased prevalence of NAFLD in the pediatric population appears to coincide with the increasing prevalence of obesity.

Although the disease process is not completely understood, some factors contribute to the development of NASH. These include insulin resistance; free-radical damage to fatty acids in the body, leading to inflammation and eventual tissue death and liver fibrosis; and dietary habits that cause blood fats to accumulate in the liver. People with NASH may feel healthy and show no outward signs of liver disease. However, NASH is progressive and can lead to cirrhosis and end-stage liver disease, which may require liver transplantation. Not everyone with elevated liver enzymes has liver damage. It also appears that serum aminotransferase levels are poor predictors of the severity of NAFLD. The only way to distinguish NASH from other forms of fatty liver disease, at this time, is with a liver biopsy (Patton, Sirlin, Behling, et al, 2006).

Pulmonary Complications: Childhood obesity is related to pulmonary complication, including sleep apnea, exercise intolerance, and asthma. Asthma and exercise intolerance can in turn worsen obesity by limiting physical activity and causing further weight gain. Chu, Chen, Wang, and colleagues (2009) examined the relationship between obesity and asthma in a study of more than 170,000 children in middle school. They found that significantly higher weight children had a 1.5 to 2.0 fold increase in the risk of asthma. This difference in obesity between asthmatics and nonasthmatics was significant for both sexes.

Sleep-disordered breathing is another significant problem with severely obese adults and children. Airway obstructions such as enlarged tonsils and adenoids may require assessment and intervention by an ear, nose, and throat specialist. Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) and bilevel positive airway pressure (BiPAP) are used for obese children requiring additional nighttime respiratory support.

Musculoskeletal and Abnormal Growth Acceleration: Obesity has been associated with musculoskeletal problems resulting from increased body weight on the supporting structures of the hips, knees, and feet. Slipped capital femoral epiphysis is the most common hip disorder among young teenagers and occurs when the cartilage plate (epiphysis) at the top of the femur slips out of place. Blount disease, another orthopedic problem, is the overgrowth of the medial aspect of the proximal tibial metaphysis that causes the lower leg to angle inward (tibia vara). The inner part of the tibia, just below the knee, fails to develop normally, resulting in angulation of the bone. The incidence of Blount disease is low. The cause is unknown, but it is thought to be due to the effects of weight on the growth plate. Approximately two thirds of patients with Blount disease are obese (Dietz, 1998), and one study has shown a dose-response relationship between BMI and Blount disease (Pirpiris, Jackson, Farng, et al, 2006).

Obesity is the most common cause of abnormal growth acceleration in childhood. Overweight children tend to be taller with advanced bone age and mature earlier than children who are not overweight. Longitudinal studies of children who became overweight have shown that height accelerates either with or shortly after excessive weight gain (Garn and Clark, 1976). Some data indicate that females with an elevated BMI achieve earlier pubertal milestones than their counterparts with a normal BMI (Rosenfield, Lipton, and Drum, 2009).

Psychologic and Social Complications of Obesity: Studies of the psychologic and social components of obesity have revealed a mixture of findings. Childhood obesity has been associated not only with metabolic health risk, but also with problems in social interactions and relationships. Obese children become targets of early and systematic discrimination. Early studies reported that children at a young age are sensitized to obesity and have begun to incorporate the culture’s preference for thinness.

Dietz (1998) found that in spite of the negative impressions of obesity, overweight young children do not appear to have negative self-image or low self-esteem. However, this differs for adolescents. Obesity status is inversely related to several self-perception factors (Strauss, 2000). Many appear to develop a negative self-image that persists into adulthood. Several researchers have found body dissatisfaction to be associated with lowered self-esteem in some populations (Mirza, Davis, and Yanovski, 2005; Muris, Meesters, van de Blom, et al, 2005).

Janssen, Craig, Boyce, and colleagues (2004) did a study that examined the association between overweight and obesity and bullying in school-aged children. They found that overweight children are more frequently the victims of bullying compared with children of normal weight. Bullying behaviors included name calling, teasing, threats, physical harm, rejection, rumors, and sexual harassment. Because adolescents are extremely reliant on their peers for social support, identity, and self-esteem, they are particularly at risk for the negative consequences of bullying and victimization.

Some studies have found that social problems among obese adolescents are quite prevalent and predictive of both short- and long-term psychologic outcomes. Studies have found that being overweight during adolescence has an effect on high school performance. Overweight adolescents have also been found to have lower household incomes as adults than their normal weight peers (Janssen, Craig, Boyce, et al, 2004).

More studies are needed to better understand the effects of overweight and obesity on the psychologic and social functioning of children and adolescents.

Diagnostic Evaluation

For some time, assessment and treatment of obesity in children consisted of little more than weighing and dietary counseling. With increasing knowledge of the potential health risks of obesity, a more thorough evaluation may be indicated. A careful history is obtained regarding the development of obesity, and a physical examination is performed to differentiate simple obesity from increased fat that results from organic causes. A family history of obesity, diabetes, coronary heart disease, and dyslipidemia should be obtained for all children who are overweight or at risk for overweight. Specific information from the patient and family about the effects of obesity on daily functioning—for example, problems with nighttime breathing and sleep, daytime sleepiness, pain in the joints, ability to keep up with family activities and peers at school—is helpful. The physical examination should focus on identifying comorbid conditions and identifiable causes of obesity. For some, psychologic assessment, by interviews and standardized personality tests, may provide insight into the personality and emotional problems that contribute to obesity and that might interfere with therapy.

It is useful to estimate the degree of obesity to determine the component of body weight that can be modified. All the following methods have been used to assess obesity: BMI, body weight, weight-height ratios, weight-age ratios, hydrostatic weight, dual energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA), skinfold measurements, bioelectrical analysis, computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and neutron activation. Each of these methods has advantages and disadvantages. Hydrostatic, or underwater, weighing provides the most accurate measurement of lean body weight. In hydrostatic weighing, total body density is determined by total submersion in a water-filled tank. However, this method is not practical in clinical settings. Skinfold thickness with special calipers defines obesity as skinfold thickness greater than or equal to the 85th percentile. Human error is a problem with this method; results can vary greatly for health care professionals who do not perform these measurements frequently.

The bioelectrical impedance method determines body fat from measures of impedance of electrical current by way of electrodes attached to the arm and leg. CT is used to estimate subcutaneous and intraabdominal fat deposition. MRI provides clear images of fat deposits compared with tissues containing water and other components. Total-body neutron activation provides an estimation of water and fat, as well as calcium, protein, and other components. These techniques are expensive and are typically used in specialized clinical setting (Gibson, 2005).

BMI is currently considered the best method to assess weight in children and adolescents (Barlow and Expert Committee, 2007). The calculation is based on the individual’s height and weight. In adults, BMI definitions are fixed measures without regard for sex and age. The BMI in children and adolescents varies to accommodate age- and gender-specific changes in growth. The formula for BMI calculation can be found in the footnote on p. 142. BMI measures in children and adolescents are plotted on growth charts that enable heath care professionals to determine BMI-for-age for the patient. (See Appendix B.)

The initial assessment of obese children and adolescents should include screening to evaluate for comorbidities. The history is an important guide to determine the workup. A complete physical examination is important. Some areas to focus on include (1) skin for stretch markings and discolorations (e.g., acanthosis nigricans), (2) joints for swelling and evidence of pain, and (3) airway for evidence of obstruction and enlarged tonsils. Basic laboratory studies include a fasting lipid panel; fasting insulin level; fasting glucose hepatic enzymes, including a γ-glutamyltransferase (GGT); and, in some institutions, hemoglobin A1c. Other studies, such as a polysomnogram (sleep study), metabolic studies, and radiographic evaluations, may be added based on the history and physical examination. These assessments may determine whether the patient needs a referral to specialty services for more focused evaluation and treatment, such as endocrinology (insulin resistance, diabetes), hepatology (elevated liver enzymes, NAFLD), orthopedics (Blount disease), or pulmonary medicine (sleep-disordered breathing, CPAP).

Therapeutic Management

The best approach to the management of obesity is a preventive one. Early recognition and control measures are essential before the child or adolescent reaches an obese state. Health care providers need to educate families about the medical complications of obesity.

Currently, the only treatments recommended for children are diet, exercise, behavior modification, and in some situations pharmacologic agents such as sibutramine and orlistat. The treatment of obesity is difficult. Many approaches do not achieve long-term success. The average individual only loses about 5% to 10% of his or her weight with the current available therapies. Losing weight can have a significant positive effect on many comorbidities, but unfortunately the lost weight is frequently regained in a year or two (Yanovski and Yanovski, 2002). A number of multidisciplinary programs offer interventions combining medical, dietary, exercise, and psychologic support. This therapy is labor intensive and fairly costly.

Researchers continue searching for medications that will successfully treat obesity. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has approved sibutramine, an appetite suppressant, for use in adolescents 16 years old and older for the treatment of obesity (US Preventive Services Task Force, 2010). There are currently no drugs approved for use in overweight or obese children under the age of 12 years. Many medical centers are studying surgical approaches to the management of obesity. Surgical techniques have seen growing use in adults, but their application in children is being cautiously evaluated.

Diet: Diet modification is an essential part of weight-reduction programs. Dietary counseling focuses on improving the nutritional quality of the diet rather than on dietary restriction. Children should avoid fad diets. Most dietitians and nutrition experts recommend a diet with no trans fats, low-saturated fat, moderate total fat (<30%), and nine servings of fruits and vegetables, consistent with MyPlate. Also, promoting high-fiber foods and avoiding highly refined starches and sugars will decrease caloric intake. Many programs recommend using a food diary as a helpful tool to increase awareness of food choices and eating behaviors. The goal is to encourage the individual to make healthier choices in foods selection and discourage using food by habit or to appease boredom. Box 21-1 contains helpful suggestions.

Many dietitians recommend encouraging parents to take charge of family meals to improve their nutritional quality. Getting families to sit down together at the table, away from distractions such as television, makes dinner time more than just eating. Dinner time becomes a time to share the events of the day and build relationships (Baker, Barlow, Cochran, et al, 2005).

Special Diets: In patients with severe obesity, strict diets have been used, such as the protein-sparing modified fast, hypocaloric, ketogenic diet, that are designed to provide enough protein to minimize loss of lean body mass during weight loss. These diets need to be closely monitored and should be used only with multidisciplinary teams that include a physician, nutritionist, and behavior therapist. Generally, the diet consists of 1.5 to 2.5 g of protein per kilogram. The intake of carbohydrates is low enough to induce ketosis. The benefits of the diet are relatively rapid weight loss and anorexia induced by ketosis. Potential complications include protein losses, hypokalemia, hypoglycemia, inadequate calcium intake, and orthostatic hypotension. Potassium and calcium supplements and adequate calorie-free beverages can minimize these complications (Baker, Barlow, Cochran, et al, 2005). It is difficult to sustain these diets over the long term, and the long-term outcomes of using these diets have not been established.

Physical Activity: Regular physical activity is incorporated into all weight-reduction programs. Any form of increased physical activity is beneficial, provided that the activities are age appropriate and enjoyable. Recommendations for physical activity need to consider the patient’s current health status and developmental level. Current recommendations encourage children to be physically active for 60 minutes or more a day. The best choice for exercise is any form that is enjoyable and likely to be sustainable. Aerobic and endurance exercises help oxidize body fats. Light exercises like walking may provide an opportunity for the family to increase time together and increase caloric expenditure. Weight training can increase basal metabolic rate and replace fat mass with muscle mass. However, weight training is not generally recommended for prepubertal children until they have reached physical and skeletal maturity. In prepubertal children increasing outdoor playtime is likely to be beneficial. Many children find exercise videos and treadmills boring and may not continue these activities. Behavioral research supports that individuals are more likely to exercise when they have a choice (Thompson and Wankel, 1980; Martin, Dubbert, Katell, et al, 1984). Individuals can choose from a large variety of physical activities, including team sports and individual sports such as yoga, dance, bike riding, swimming, and karate.

Limiting sedentary behaviors such as television viewing is the most effective way to encourage physical activity (Robinson, 1999, 2001). The American Academy of Pediatrics (2006) recommends limiting television viewing to less than 2 hours a day. Box 21-2 shows more strategies to increase physical activities.

Behavior Modification: Behavior modification approaches to weight loss are based on the observation that obese individuals have abnormal eating practices that can be altered. Attention is focused not on food but on the social and behavioral aspects surrounding food consumption. Successful behavior modification weight programs help adolescents identify and eliminate inappropriate eating habits and include a problem-solving component that enables adolescents to identify problems and determine solutions. Combining behavioral modifications with pharmacologic therapy in children 12 years and older has produced mixed results with regard to total weight loss maintained over a significant period of time (US Preventive Services Task Force, 2010). Reports suggest modest benefits with moderate-to-high behavioral interventions (measured in number of contact hours) in decreasing mean BMI of children and adolescents involved in such programs over a period of 6 to 12 months (Whitlock, O’Connor, Williams, et al, 2010). Programs including family-based behavioral modification, dietary modification, and exercise have been shown to be successful in reducing obesity in some children (American Academy of Pediatrics, 2006). Behavior modification is an important part of multidisciplinary intervention programs.

Drugs: A number of medications have been used in adults with varying results. Currently, multicenter clinical trials are being conducted to evaluate the effects of medications on weight loss in children. To date the only drug approved for use in adolescents is the appetite suppressant sibutramine. Orlistat, a lipase inhibitor, has been approved for use in children 12 years and older. Currently no long-term data are available regarding the benefits of such drugs for obesity management in children and adolescents (US Preventive Services Task Force, 2010). Some drugs have been used to promote weight loss in children with certain conditions such as metformin in obese adolescents with insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia, octreotide for hypothalamic obesity caused by intracranial tumors, growth hormone in children with Prader-Willi syndrome, and leptin for congenital leptin deficiency (Baker, Barlow, Cochran, et al, 2005; Freemark and Bursey, 2001; Myers, Carrel, Whitman, et al, 2000; Farooqi, Jebb, Langmark, et al, 1999).

Surgical Techniques: Surgical techniques (bariatric surgery) that bypass portions of the intestine or occlude a segment of the stomach to produce a marked diet restriction and weight loss are hazardous and cause many metabolic complications. These complications include severe water and electrolyte depletion, persistent diarrhea, vitamin deficiency, internal herniation, and fatty infiltration and degeneration of the liver. In the recent past, these procedures were considered contraindicated for pediatric patients. Surgical intervention for children and adolescents is being reevaluated in the context of the significant increase in the prevalence of obesity and concomitant comorbidities within this population.

Bariatric surgery may be the only practical alternative for increasing numbers of severely overweight adolescents who have failed organized attempts to lose or maintain weight loss through conventional nonoperative approaches and who have serious life-threatening conditions. There are few studies in adults and no information for adolescents that suggest surgical weight loss improves the early mortality of patients with severe obesity. Therefore, in general, bariatric surgery should be reserved for severely obese adolescents with comorbidities after careful consideration. Physicians must define clear, realistic, and restrictive guidelines to apply with younger patients when surgery is considered. Candidates for surgery should be referred to centers that offer a multidisciplinary team experienced in the management of childhood and adolescent obesity. The surgery should be performed by surgeons who have participated in subspecialty training in bariatric medical and surgical care as detailed by the American College of Surgeons and the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery.

It is recommended that a pediatric review process be in place to carefully screen patients. Candidates should undergo complete medical assessments and psychologic evaluations that include the patient and parents. The most important ethical considerations for bariatric surgery in an adolescent are whether (1) the patient’s health is severely compromised by severe obesity, (2) the patient has failed more conservative treatment options, and (3) the patient (adolescent) has the ability to make this decision. Current criteria for bariatric surgery include (1) failed attempt at weight loss for at least 6 months as determined by the primary care physician; (2) attainment of physical maturity (Tanner stage IV); (3) BMI of at least 40 with serious obesity-related comorbidities, or BMI of at least 50 with less severe comorbidities (Box 21-3); (4) demonstrated commitment to comprehensive medical and psychologic evaluations both before and after surgery; (5) agreement to avoid pregnancy for at least 1 year postoperatively; (6) ability and willingness to adhere to nutritional guidelines; (7) ability to give informed consent to surgical treatment; and (8) a supportive family environment (Inge, Krebs, Garcia, et al, 2004).

In addition, recent recommendations state that bariatric surgery should be limited to youth (12 to 18 years old) with a BMI of 40 or more. Surgery is appropriate only for those with severe to moderate degrees of comorbidities, such as diabetes with hemoglobin A1c greater than 9, regardless of therapy. Only the most severe degree of hypertension is an appropriate criterion for this group. Elevated lipids and sleep apnea, regardless of level of treatment, are also appropriate criteria for surgery in adolescents. Chronic joint pain in its most severe state, venous stasis disease, and impaired quality of life are also considered appropriate criteria for this young age-group (Yermilov, McGory, Shekelle, et al, 2009). Laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding surgery was effective in reducing weight by as much as 55% at 1- and 2-year follow-up in 73 obese pediatric patients aged 13 to 17 years (Nadler, Youn, Ren, et al, 2008).

Surgical treatment options for adolescents should be chosen carefully and with the support of the multidisciplinary team, the patient, and the family. More will be learned about outcomes of this approach with time and careful study and evaluations. It is strongly recommended that all patients who have bariatric surgery be monitored throughout their lives. Knowledge about appropriate timing and better surgical and postoperative management of adolescent surgical patients depends on the rigorous collection of high-quality outcome data (Inge, Krebs, Garcia, et al, 2004).

Nursing Care Management

Nurses play a key role in the adherence and maintenance phases of many weight-reduction programs. Nurse practitioners assess, manage, and evaluate the progress of many overweight adolescents. They also play an important role in recognizing potential weight problems and assisting parents and adolescents in preventing obesity.

The presence of obesity may not be obvious from appearance alone. Regular assessment of height and weight and computation of the BMI facilitate early recognition. There are published guidelines for childhood obesity prevention and treatment (Barlow and Expert Committee, 2007). Evaluation includes a height and weight history of the adolescent and family members, eating habits, appetite and hunger patterns, and physical activities. A psychosocial history is also helpful in understanding the impact of obesity on the child’s life. Davis, Gance-Cleveland, Hassink, and colleagues (2007) describe steps to approaching behavior change with youth (Box 21-4).

Before initiating a treatment plan, it is important to be certain that the family is ready for change. Lack of readiness may result in failure, frustration, and reluctance to address the problem in the future. It may be wiser to defer treatment until the family is ready (Box 21-5). The nurse should explore with adolescents the reasons behind the desire to lose weight because motivation to lose weight is the key to success. Adolescents need to take a personal responsibility for dietary habits and physical activity. Teens who are forced by their parents to seek help are seldom motivated, become rebellious, and are unwilling to control their dietary intake.

Nutritional Counseling: Preventing an increase in body fat during growth is a realistic approach. This is often accomplished by adjusting four aspects of eating: (1) reducing the quantity eaten by purchasing, preparing, and serving smaller portions; (2) altering the quality consumed by substituting low-calorie, low-fat foods for high-calorie foods (especially for snacks); (3) eating regular meals and snacks, particularly breakfast; and (4) altering situations by severing associations between eating and other stimuli, such as eating while watching television. Nutrition counseling incorporates health behavior theories to help motivate and maintain behavior change. The most successful changes are those that are attainable, reasonable, and sustainable.

The nurse teaches adolescents and parents how to incorporate favorite foods into their diet and to select satisfying substitutes. To maintain a healthy diet, it is necessary to encourage the consumption of nutrient-dense foods such as fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and low-fat dairy protein products. Calories and fat should be kept to a healthy level without being significantly restricted. To be successful, a dietary program should be nutritionally sound with sufficient satiety value, produce the desired weight loss, and be accompanied by nutrition education and continued support.

Behavior Therapy: Altering eating behavior and eliminating inappropriate eating habits are essential to weight reduction, especially in maintaining long-term weight control. Most behavior modification programs include the following concepts:

• A description of the behavior to be controlled, such as eating habits

• Attempts to modify and control the stimuli that govern eating

• Development of eating techniques designed to control speed of eating

• Positive reinforcement for these modifications through a suitable reward system that does not include food

Box 21-1 includes specific strategies to modify eating habits.

Group Involvement: Commercial groups (e.g., Weight Watchers) or diet workshops are usually directed to adults; a group of other adolescents is often more effective. Teenage groups include summer camps designed for obese young people and conducted by health professionals, school groups organized and led by a school nurse or health professional, and groups associated with special clinics.

These groups are concerned not only with weight loss but also with the development of a positive self-image, social support, and the encouragement of physical activity. Nutrition education, diet planning, and the improvement of social skills are essential components of these groups. Improvement is determined by positive changes in all aspects of behavior.

Family Involvement: There is a definite connection between family environment, interaction, and obesity. The nurse needs to educate parents in the purposes of the therapeutic measures and their role in management. The family needs nutrition education and counseling regarding the reinforcement plan, alterations in the food environment, and ways to maintain proper attitudes. They can support their child in efforts to change eating behaviors, food intake, and physical activity.

Prognosis: Lifelong eating habits and psychologic problems make weight reduction difficult. Weight reduction is more successful in older adolescents who have lean parents, a good academic performance, no affective disorder, and no recent stressful life event (such as parents’ divorce or a death).

Prevention: Reducing adolescent obesity has been identified as a national public health priority by the Institute of Medicine and numerous other expert groups. In 2005 the Institute of Medicine Committee on Prevention of Obesity in Children and Youth (Koplan, Liverman, and Kraak, 2005) developed guidelines for the prevention of childhood obesity. These guidelines suggest federal, state, local community, industry, and media changes that can positively affect childhood obesity in the United States. Weight loss programs do not enjoy the success of therapeutic interventions for other disorders. Gradual accumulation of adipose tissue during childhood establishes a pattern of eating that is difficult to reverse in adolescence. Prevention of obesity should begin in early childhood with the development of healthy eating habits, regular exercise patterns, and a positive relationship between parents and children. Prevention of adolescent obesity is best accomplished by early identification of obesity in the preschool, school-age, and preadolescent periods. Health care professionals should encourage frequent health care visits for children who are overweight or obese and incorporate a dietary history and counseling into each well-infant, well-child, and well-adolescent visit.

Eating Disorders

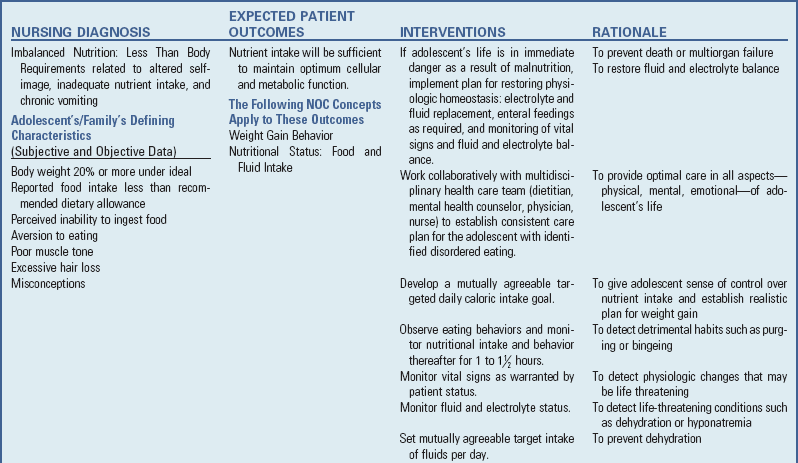

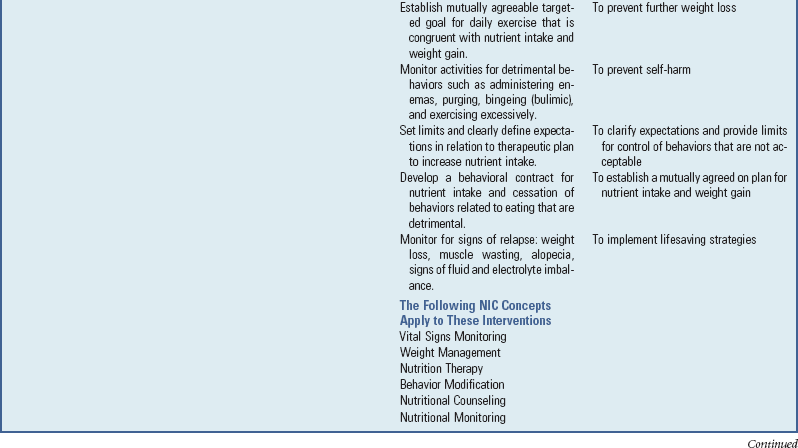

![]() Eating disorders affect an estimated 5 million Americans every year. These psychologic illnesses include anorexia nervosa (AN), bulimia nervosa (BN), binge eating, and variations of these. Eating disorders are characterized by serious disturbances in eating and distortion of the body image that is manifested by restriction of intake or bingeing and an obsessive concern about body shape or body weight. These behaviors have the potential to cause serious health problems resulting from the physiologic sequelae brought on by altered nutritional status and purging. Often there is a significant delay in the diagnosis and treatment that relates to the nature of the illness; however, those with AN have one of the highest mortality rate of all psychiatric illnesses (Marcus, 2007; Neumarker, 1997). Persons with eating disorders frequently hide their symptoms because of a lack of awareness of the effects on their health, the shame of discussing their symptoms with others, and an unwillingness to give up these harmful behaviors (Becker, Grinspoon, Klibanski, et al, 1999).

Eating disorders affect an estimated 5 million Americans every year. These psychologic illnesses include anorexia nervosa (AN), bulimia nervosa (BN), binge eating, and variations of these. Eating disorders are characterized by serious disturbances in eating and distortion of the body image that is manifested by restriction of intake or bingeing and an obsessive concern about body shape or body weight. These behaviors have the potential to cause serious health problems resulting from the physiologic sequelae brought on by altered nutritional status and purging. Often there is a significant delay in the diagnosis and treatment that relates to the nature of the illness; however, those with AN have one of the highest mortality rate of all psychiatric illnesses (Marcus, 2007; Neumarker, 1997). Persons with eating disorders frequently hide their symptoms because of a lack of awareness of the effects on their health, the shame of discussing their symptoms with others, and an unwillingness to give up these harmful behaviors (Becker, Grinspoon, Klibanski, et al, 1999).

![]() Nursing Care Plan—The Adolescent with an Eating Disorder

Nursing Care Plan—The Adolescent with an Eating Disorder

Anorexia Nervosa and Bulimia Nervosa

AN is a complex illness that results in significant morbidity and mortality. It is a disorder with social, psychologic, behavioral, cultural, and physiologic components. AN is characterized by a strong fear of becoming fat, a distorted body image, and progressive weight loss. The disorder is a clinical diagnosis listed in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV-TR) (American Psychiatric Association, 2000) (Box 21-6).

Bulimia refers to an eating disorder somewhat similar to AN. BN is characterized by repeated episodes of binge eating followed by inappropriate compensatory behaviors, such as self-induced vomiting; misuse of laxatives, diuretics, or other medications; fasting; or excessive exercise (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). The binge behavior consists of secretive, frenzied consumption of large amounts of high-calorie (or “forbidden”) foods during a brief time (usually <2 hours). The binge is counteracted by a variety of weight control methods (purging), including self-induced vomiting, diuretic and laxative abuse, and rigorous exercise. These binge-purge cycles are followed by self-deprecating thoughts, a depressed mood, and an awareness that the eating pattern is abnormal (Box 21-7).

Binge eating disorder (BED) is currently recognized as a diagnostic category in need of further study and as a type of eating disorder not otherwise specified (EDNOS). It is characterized by recurrent binge eating (overeating accompanied by loss of control occurring on average at least twice weekly for 6 months) and marked distress in the absence of regular compensatory behaviors (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). Binge episodes may be associated with a cluster of symptoms, including eating rapidly; eating until uncomfortably full; eating large amounts in the absence of hunger; eating in secret due to embarrassment; and feeling disgusted, depressed, or guilty after eating.

Epidemiology

The incidence of AN in adolescent females in the United States has been estimated at 0.5%, and between 1% and 5% of these girls meet the criteria for bulimia (American Academy of Pediatrics, 2003). However, estimates of the prevalence of disordered eating reaches up to 65% of females and 35% of males (Croll, Neumark-Sztainer, Story, et al, 2002). The incidence is approximately 5 to 10 in 100,000 population per year. The incidence in males is one tenth of that of females.

The epidemiology of these eating disorders is difficult to accurately assess because of changes in diagnostic criteria over time and because the methods of detection, primarily self-report, may not be reliable in an illness characterized by denial and secrecy. Most resources report an increase in the incidence of AN and BN over the past 50 years, but the prevalence in the past 20 years is debated. The highest incidence occurs in 15- to 19-year-olds. The onset of the disorder appears to have two peaks: at age 14 and age 18 (Foreman, 2009). BED is reported among 20% to 35% of youth seeking weight loss treatment (Eddy, Celio Doyle, Hoste, et al, 2008). The incidence of AN, in particular, is increasing in emerging economies or non-Western societies (Latzer, Azaiza, and Tzischinsky, 2009; Preti, Girolamo, Vilagut, et al, 2009). Although most people with AN recover completely or partially, about 5% die of the condition and 20% develop a chronic eating disorder (Lock and Fitzpatrick, 2009).

Pathophysiology

No consensus exists on the pathophysiology of AN and BN. It has been shown that AN, BN, and BED patients do not differ from each other in their level of shape and weight concern, but do differ from those without eating disorders (Devlin, Goldfein, and Dobrow, 2003). A combination of genetic, neurochemical, psychodevelopmental, and sociocultural factors appear to cause the disorder (Becker, Grinspoon, Klibanski, et al, 1999; Hudson, Hiripi, Pope, et al, 2007). Dieting appears to be common to the initiation of both AN and BN. Also characteristic is a childhood preoccupation with being thin reinforced by sociocultural and environmental factors supporting the concepts of ideal body shape. Many sports and artistic endeavors that emphasize leanness (e.g., ballet and running) and sports in which the scoring is partly subjective (e.g., skating and gymnastics) have been associated with a higher incidence of eating disorders. The term female athlete triad, characterized by eating disorder, amenorrhea, and osteoporosis, has been applied to young women with restrictive eating disorders and amenorrhea (Rome, Ammerman, Rosen, et al, 2003).

The prominent physiologic changes that occur as a result of weight loss have raised suspicion for a prominent physiologic disturbance as causative factor. Since most of these physiologic disturbances resolve with the normalization of body weight, this argues against their role as a primary cause. The neurotransmitter serotonin affects appetite control, sexual and social behavior, stress responses, and mood and possibly accounts for some of the changes seen in patients with AN. BED is also associated with dopamine in the nucleus accumbens portion of the brain that is programmed for reward and motivation. Neuroimaging studies using MRI and, more recently, positron emission tomography scans have demonstrated subtle changes, but the significance of these changes and their connection to eating disorders are not well understood (Rome, Ammerman, Rosen, et al, 2003; Foreman, 2009; Chial, McAlpine, and Camilleri, 2002; Van den Eynde and Treasure, 2009; Avena, 2009).

Familial transmission is an area that has attracted research attention, but there are no strong empirical data to indicate that one particular family prototype is responsible for the development of an eating disorder. However, many experts have associated the development of an eating disorder with family characteristics such as an adolescent perception of high parental expectations for achievement and appearance, difficulty managing conflict, poor communication styles, enmeshment and occasionally estrangement between family members, devaluation of the mother or the maternal role, marital tension, and mood and anxiety disorders. Families struggling with an eating disorder have been characterized as often having difficulties responding positively to the changing physical and emotional needs of the adolescent. Family stress of any kind may become a significant factor in the development of an eating disorder (Foreman, 2009; Lilenfeld, Kaye, Greeno, et al, 1998; Hudson, Laird, Betensky, et al, 2001; Strober, Freeman, Lampert, et al, 2007).

Results of twin studies suggest that both genetic and environmental factors contribute to the development of AN. A concordance rate for AN appears higher in monozygotic twins compared with dizygotic twins (Chial, McAlpine, and Camilleri, 2002). There also appears to be a higher prevalence of affective disorders and alcoholism in first-degree relatives of patients with eating disorders (Hudson, Laird, Betensky, et al, 2001; Foreman, 2009).

Individuals with eating disorders commonly have psychiatric problems, including affective disorder, anxiety disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and personality disorder. Adult women with eating disorders were found to have higher rates of obsessive-compulsive behavior traits in their childhood. Persons with eating disorders have also been found to have higher reported rates of substance abuse, with alcohol problems being more common in those with BN than AN (Foreman, 2009). It is important to note that many of the clinical findings are directly related to the state of starvation and improve with weight gain.

Research continues in an effort to better understand the etiology and pathogenesis of eating disorders.

Clinical Manifestations

The most obvious manifestation of AN is the severe and profound weight loss induced by self-imposed starvation (see Box 21-6). The adolescents identify with this skeleton-like appearance and do not regard it as abnormal or ugly. Adolescents with AN often eat small amounts of food or play with food on their plates to give the impression that they are eating adequately and not experiencing disturbances in their eating habits. This can lead friends and family to disregard the possibility of AN. The adolescents can display a marked preoccupation with food—preparing meals for others, talking about food, hoarding food. Some become obsessed with fasting and engage in frequent strenuous exercise, self-induced vomiting, or laxative usage to speed up the weight-loss process (Lock and Fitzpatrick, 2009).

These young people tend to withdraw from peer relationships and engage in self-imposed social isolation. They continually strive for perfection, which may be demonstrated in other compulsive behaviors. They are usually overachievers, and their school work is very important to them.

In the wake of the severe weight loss, these girls and young women exhibit physical signs of altered metabolic activity. They develop secondary amenorrhea, bradycardia, lowered body temperature, decreased blood pressure, and cold intolerance. They have dry skin and brittle nails and develop lanugo. The changes are usually reversible with adequate weight gain and improved nutritional status.

Bulimia is more common in older adolescent girls and young women; males with bulimia are less common. BN patients may be of average or slightly above average weight. The diagnosis is confirmed, according to American Psychiatric Association’s DSM-IV-TR (2000) (see Box 21-7), by at least two binge-eating episodes per week for the preceding 3 months. Although persons with bulimia have many issues in common with those who have other eating disorders, impulse control and satiety regulation are important problems in bulimia. Many individuals with bulimia begin with only occasional binges and purges “just for fun,” enjoying the control over their weight while eating amounts of food that would normally produce obesity. As the disease progresses, the frequency of binges increases, the amount of food consumed increases, and they gradually lose control over the binge-purge cycle. The purging provides relief from feelings of guilt resulting from the enormous amounts of food consumed. The family becomes angry, and the individual with bulimia becomes frightened, frustrated, and increasingly guilt ridden, which only increases the symptoms in the self-destructive cycle.

The frequency of bingeing can be anywhere from once per week to seven or eight times per day. Because persons with bulimia usually binge on high-calorie foods, especially sweets, ice cream, and pastries, insulin production is stimulated to cope with the added carbohydrates. When the food is vomited, the unused insulin stimulates hunger and the desire to eat.

Diagnostic Evaluation

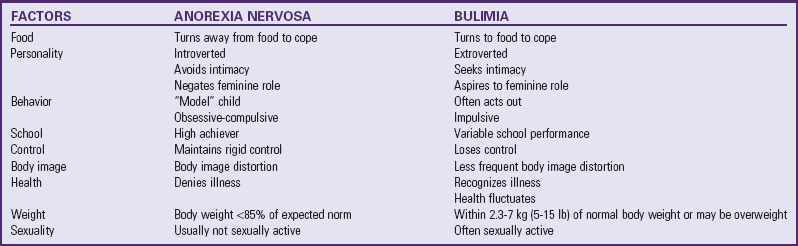

Diagnosis is made on the basis of clinical manifestations and conformity to the criteria established by the American Psychiatric Association (2000) (see Boxes 21-6 and 21-7). The DSM-V will be published in 2012, and these diagnoses criterion will likely change slightly. Table 21-1 lists the differences between AN and BN. A diagnosis of bulimia may first be suspected from the presence of complications.

Screening Tools: All patients in high-risk categories for eating disorders should be screened during routine office visits. The medical history is most important for diagnosing eating disorders, since the physical examination may be normal, especially early in the illness. A number of screening questionnaires are available to assist with the interview. For example, with the Scoff Questionnaire, 1 point is scored for every “yes.” A score of 2 or more indicates a likely case of AN or BN. The questions related to the mnemonic SCOFF are (1) Do you make yourself sick because you feel uncomfortably full? (2) Do you worry that you have lost control over how much you eat? (3) Have you recently lost more than 6.4 kg (14 lb, or one stone) in a 3-month period? (4) Do you believe yourself to be fat when others say that you are too thin? (5) Would you say that food dominates your life? (Morgan, Reid, and Lacey, 1999).

History and Physical Examination: A complete history and physical examination are important to rule out other causes for weight loss. The medical assessment of an eating disorder focuses on the complications of altered nutritional status and purging. A careful history assesses weight changes, dietary patterns, and the frequency and severity of purging and excessive exercise. Purging behaviors include vomiting or other methods such as abuse of laxatives, enemas, diuretics, anorexic drugs, caffeine, or other stimulants. Measure the patient’s weight and height and evaluate it for appropriateness according to standard weight for height, age, and sex determined according to the percentile of his or her expected body weight or BMI.

Particularly important parts of the physical examination are vital sign measurement (heart rate and blood pressure both supine and standing, and body temperature). Hypotension, bradycardia, and hypothermia are often seen in association with extremely low weight. Dry skin, lanugo, acrocyanosis, and breast atrophy are findings that have been associated with AN. Distinctive hand lesions (Russell sign) have also been observed; the backs of the hands are often scarred and cut from repeated abrasion of the skin against the maxillary incisors during self-induced vomiting (Lock and Fitzpatrick, 2009). Other findings include swelling of the parotid and submandibular glands and erosion of the enamel of the anterior teeth because of chronic acid exposure from vomiting.

Prolongation of the QT interval may be detected in some patients. Mitral valve prolapse (MVP) may also develop. An abdominal examination is important to detect intestinal dilation from chronic severe constipation as a result of decreased intestinal motility. Finally, a neurologic examination assesses for other causes of weight loss or vomiting such as evidence of brain tumor.

Laboratory Assessments: The initial laboratory assessment for a patient with an eating disorder should include a complete blood count to evaluate for anemia and other hematologic abnormalities. An erythrocyte sedimentation rate or C-reactive protein may be ordered to detect evidence of inflammation. These levels should be low in an eating disorder. Electrolytes should be measured, along with calcium, magnesium, phosphorus, blood urea nitrogen, and creatinine, if the patient appears to be dehydrated or if purging is suspected. A human chorionic gonadotropin measurement is done to rule out pregnancy in patients with prolonged amenorrhea. A urinalysis to assess the specific gravity helps to detect water loading, since many patients attempt to increase their weight this way. In females with amenorrhea, thyroid function tests and measurement of serum prolactin and follicle-stimulating hormone can help rule out prolactinoma (hormone-secreting pituitary tumor), hyperthyroidism, hypothyroidism, or ovarian failure. A bone density study may be ordered to detect bone loss, which is a complication of AN. Other tests are included based on findings of the physical examination.

Complications of Eating Disorders

Many potential complications can occur as a result of starvation and persistent purging. Some of these are osteoporosis, cardiac impairments, cognitive changes, difficulties in psychologic functioning, gastrointestinal dysfunction (e.g., slowed motility, symptoms of nausea and bloating), endocrinologic changes, electrolyte abnormalities (especially hypokalemia and metabolic alkalosis), dental erosions, enlarged salivary glands, and infertility.

The pathogenesis of osteoporosis is not completely understood but is believed to be associated with estrogen deficiency, inadequate vitamin D and calcium intake, and the nutritional effects on bone loss.

AN has been associated with MVP, possible QT interval prolongation, and heart failure. MVP is a common finding in patients with AN, affecting 32% to 60% of patients compared with 6% to 22% in the general population. This may be because of an increased ability to detect the disorder in patients with intravascular volume depletion consistent with the state of starvation.

The risk of heart failure is greatest in the first 2 weeks of refeeding in patients with an eating disorder. Patients with moderate to severe AN (e.g., >10% below ideal body weight) are at risk for the refeeding syndrome during the first 2 to 3 weeks of treatment. Refeeding syndrome consists of cardiovascular, neurologic, and hematologic complications that occur because of shifts in phosphate from extracellular to intracellular spaces in individuals who have total body phosphorus depletion as a result of malnutrition. Refeeding syndrome can cause cardiac arrest and delirium. The risk is reduced by slower refeeding, replacing phosphorus, and carefully avoiding a high sodium intake. Carefully monitoring serum electrolytes and observing for signs of edema or congestive heart failure are important during refeeding.

Amenorrhea occurs in 90% of women with AN as a result of low levels of follicle-stimulating hormone and luteinizing hormone. Menses is usually restored within 6 months of achieving 90% of the ideal body weight.

Therapeutic Management

The treatment and management of AN involve three major thrusts: (1) reinstitution of normal nutrition or reversal of the severe state of malnutrition, (2) resolution of disturbed patterns of family interaction, and (3) individual psychotherapy to correct deficits and distortions in psychologic functioning. Because of the psychogenic nature of the disorder, the treatment may be long.

Most adolescents with AN are treated on an outpatient basis. However, adolescents who have severe malnutrition, electrolyte disturbances, vital sign abnormalities, or psychiatric disturbances (e.g., severe depression or suicidal ideation) may require hospitalization (Box 21-8). Therapy for the adolescent with AN requires interventions delivered by a multidisciplinary team that includes dietitians, physicians, nurses, counselors, and psychologists or psychiatrists.

Nutrition: The initial goal is to treat the life-threatening malnutrition with strict adherence to dietary requirements, which may necessitate intravenous or tube feeding in severe situations. Dietary interventions are combined with family psychotherapy to improve the underlying psychologic misconception about the weight loss. Weight gain alone cannot be considered a cure for the disease and is an unreliable sign of progress. Relapses are frequent as the person reverts to previous eating patterns when removed from the therapeutic environment.

The dietitian should be experienced in working with children and adolescents and understand how to implement a dietary plan with sufficient calories needed for weight restoration. The plan needs to be firm but flexible. Letting the patient participate in setting up a food plan and teaching food exchanges to patients and parents is important so they can make food choices that will promote weight restoration. The goals of weight restoration are to avoid serious medical complications and restore cognitive functioning to derive the maximum benefit from psychotherapy. Methods that have been used include oral, nasogastric, and intravenous feedings. The least intrusive method for weight restoration should be used, only resorting to nasogastric or intravenous feeds when other strategies have failed. A reasonable goal for weight gain is approximately 1 kg (2 lb) per week. Pushing for more rapid weight gain can result in increasing anxiety or depression and result in bulimia.

Psychotherapy: Psychotherapy is central to the treatment of eating disorders. Patients need to be active participants in the treatment process to better understand the impulses, feelings, and needs that have resulted in their eating disorder. Weight restoration is a primary goal in recovery, since patients obtain only minimum benefit from psychotherapy when their weight is low. They do not process information well and have a decreased ability to concentrate. Weight restoration as an outpatient is accomplished with behavioral contracts negotiated between the therapists and patient. The goal is to increase the patient’s feelings of control and responsibility toward achieving recovery. The contract can stipulate at what weight tube feedings will be implemented. Realistic goals are set with the patient, including rewards for achievement that include special privileges or outings and consequences such as restrictions on exercise or increased consumption of a feared food. For inpatients, the contract for foods might be negotiated as food exchanges or number of calories. One suggested approach begins with 1200 calories and increases by 100-calorie increments each day. Inpatients need to be closely supervised by the nursing staff during the meal and for 1 to  hours after the meal. If the agreed on number of calories is not consumed, there might be a provision for the intake of a nutritional supplement (Mikhail, 2001; Schmidt, 2009).

hours after the meal. If the agreed on number of calories is not consumed, there might be a provision for the intake of a nutritional supplement (Mikhail, 2001; Schmidt, 2009).

Eating disorders are complex and multifaceted. Because patients often deny their illness, they may refuse the treatment efforts of health providers. The treatment plan needs to be developed carefully. Power struggles with patients may escalate the eating disorder symptomatology in that control issues are often central to the development of eating disorders. Implementing less intrusive interventions first and allowing them time to develop is important before applying more restrictive interventions. A contract is helpful to clarify for patients at what point tube feeding may be implemented so they make informed decisions about their actions. The team needs to agree about the treatment philosophy and protocol to avoid sending mixed messages to the patient. It is important to treat eating disorder patients with respect and support preservation of their self-esteem to promote a successful recovery (Mikhail, 2001; Schmidt, 2009).

It is essential that adolescents rely on their own thinking, become more realistic in self-appraisal, and become capable of living as self-directed, competent individuals who enjoy life without manipulating the body and its functions. Psychotherapy focuses on helping the young person resolve the adolescent identity crisis, particularly when it results in a distorted body image.