An Overview of Occupational Therapy for Children

1 Identify and describe best practices as presented by the chapter authors.

2 Define the rationale for and benefit of child- and family-centered interventions.

3 Identify and explain key elements of an occupational profile and performance analysis.

4 Define and describe components of effective intervention.

5 Describe models for inclusive practice.

6 Identify and discuss elements of cross-cultural competence.

7 Define and illustrate evidence-based practice with children.

Occupational therapists develop interventions based on analysis of the child’s behaviors and performance, the occupations in which he or she engages, and the context for those occupations. When evaluating a child’s performance, the therapist determines how performance is influenced by impairment and how the environment supports or constrains performance. The therapist also identifies discrepancies between the child’s performance and activity demands and interprets the meaning and importance of those discrepancies. Analysis of the interrelationships among environments, occupations, and persons, and the goodness-of-fit of these elements is the basis for sound clinical decisions. At the same time that occupational therapists systematically analyze the child’s occupational performance and social participation, they acknowledge that the spirit of the child also determines who he or she is and will become.

This text describes theories, concepts, practice models, and strategies that are used in occupational therapy with children. Its pages present interventions designed to help children and families cope with disability and master occupations that have meaning to them. Although this theoretical and technical information is important to occupational therapy practice with children, it is childhood itself that creates meaning for the practitioner. Childhood is hopeful, joyful, and ever new. The spirit, the playfulness, and the joy of childhood create the context for occupational therapy with children. This chapter describes the primary themes in occupational therapy practice with children that are illustrated throughout the text.

BEST PRACTICES IN OCCUPATIONAL THERAPY FOR CHILDREN

Using the research literature and their own expertise, the book’s authors illustrate the role of occupational therapy with children in specific practice areas and settings. Certain themes flow through many, if not most, of the chapters, suggesting that they are important to occupational therapy for children. These are described and illustrated in this chapter. Three themes relate directly to evaluation and intervention:

Three additional themes more broadly describe the nature of practice and the environments in which occupational therapists work:

Child- and Family-Centered Practice

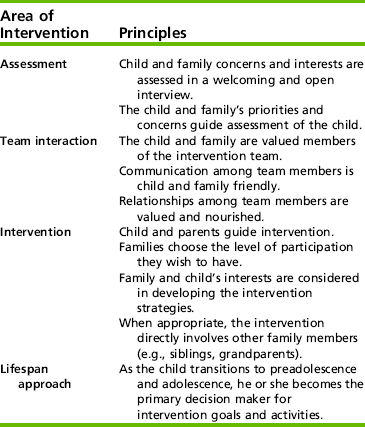

A child is referred to occupational therapy services because he or she has a specific diagnosis (e.g., autism or cerebral palsy) or because he or she exhibits a particular functional problem (e.g., poor fine motor skills or poor attention). Although the diagnosis or problem is the reason for therapy services, the occupational therapist always views the child as a person first. Client-centered intervention has many implications for how the therapist designs intervention. Primary implications of client-centered practice are listed in Table 1-1.

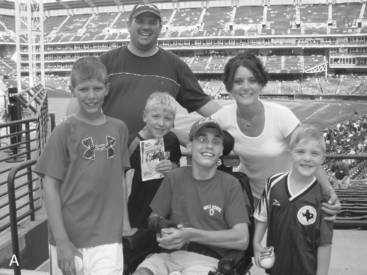

As illustrated in Chapters 7 and 8 and throughout the book, client-centered evaluation involves first identifying concerns and priorities of the child and family. Evaluation also includes learning about the child and family’s interests, frustrations, and preferences. What is important to the child and family frames the goals and activities of the intervention. Further, these interests (Figure 1-1) are assessed throughout the intervention period to ensure that services are meeting child and family priorities. Recent evidence has indicated that, in addition to using adult informants, therapists can invite children to participate more actively in the evaluation process and goal setting if the procedures used are developmentally appropriate.60 Measures have been developed to assess the child’s perspective on his or her ability to participate in desired occupations. The Perceived Efficacy and Goal Setting System (PEGS) is an example of a measure that uses the child as the primary informant.61 The information gathered from measuring children’s thoughts and feelings about their participation in childhood roles can complement results obtained from functional assessments. In addition, occupational therapists may consider gathering information about the child’s life satisfaction. Often the best strategy for gathering information about the child is to interview him or her about play interests, favorite activities, best friends, concerns, and worries, using open-ended questions.

FIGURE 1-1 The family’s unique interests determine their priorities for spending time and resources. Occupational therapy services focus on the child’s ability to participate in valued family activities.

In client-centered intervention, building a relationship with the child and family is a priority for the therapist. This relationship is instrumental to the potential effects of intervention. According to Parham et al., a primary feature of sensory integration intervention is “fostering therapeutic alliance” (p. 219).65 They describe this alliance as one in which the therapist “respects the child’s emotions, conveys positive regard toward the child, seems to connect with the child and creates a climate of trust and emotional safety”65 (see Chapter 11). In a family-centered approach, the therapist is invested in establishing a relationship with the family characterized by open communication, shared decision making, and parental empowerment.7 An equal partnership with the family is desired; at the same time, parents begin to understand that professionals are there to help them and to provide information and resources that support their child’s development.42,90

Trust building between professionals and family members is not easily defined, but it appears to be associated with mutual respect, being positive, and maintaining a nonjudgmental position with a family (see Jaffe, Case-Smith, & Humphry, Chapter 5). Trust building can be particularly challenging with certain families— for example, families whose race, ethnicity, culture, or socioeconomic status may differ from that of the occupational therapist. These families may hold strong beliefs about child rearing, health care, and disabilities that are substantially different from those of the occupational therapist. However, establishing a relationship of mutual respect is essential to the therapeutic process. Understanding the family context and respecting the family’s perspective are critical to determining the priorities for intervention and the outcomes that are most valued.

Jaffe et al. (Chapter 5) also explain that positive relationships with families seem to develop when open and honest communication is established and when parents are encouraged to participate in their child’s program to the extent that they desire. When asked to give advice to therapists, parents stated that they appreciated (1) specific, objective information; (2) flexibility in service delivery; (3) sensitivity and responsiveness to their concerns55; (4) positive, optimistic attitudes16; and (5) technical expertise and skills.7

In Chapter 23, on early intervention services, Meyers, Tauber, and Stephens explain how to collaborate with families. The occupational therapy activities most likely to be implemented by and helpful to the family are those which are most relevant to the family’s lifestyle and routines. When interventions make a family’s daily routine easier or more comfortable, the intervention has meaning and purpose and will likely have a positive effect on child and family.

Comprehensive Evaluation

The chapter authors advocate and illustrate a top-down approach1 to assessment: the occupational therapist begins the evaluation process by gaining an understanding of the child’s level of participation in daily occupations and routines with family, other caregiving adults, and peers. Initially, the therapist surveys multiple sources to acquire a sense of the child’s ability to participate and to form a picture of the child that includes his or her interests and priorities. With this picture in mind, the therapist further assesses specific performance areas and analyzes performance to determine the reasons for the child’s limitations. Table 1-2 lists attributes of occupational therapy evaluation of children.

TABLE 1-2

Description of Comprehensive Evaluation of Children

| Evaluation Component | Description of the Occupational Therapist’s Role | Tools, Informants |

| Occupational profile | Obtains information about the child’s developmental and functional strengths and limitations. Emphasis on child’s participation across environments. | Interview with parents, teachers, and other caregivers. Informal interview and observation. |

| Assessment of performance | Carefully assesses multiple areas of developmental performance and functional behaviors and underlying reasons for limitations. | Standardized evaluations, structured observation, focused questions to parents and caregivers. |

| Analysis of performance | Analyzes underlying reasons for limitations in performance and behavior. | In-depth structured observations, focused standardized evaluations. |

| Environment | Assessment and observation of the environment, focused on supports and constraints of the child’s performance. | Focused observations, interview of teachers and parents. |

Assessing Participation and Analyzing Performance

The child’s occupational profile defines the priority functional and developmental issues that are targeted in the intervention goals. With the priorities identified, the therapist completes a performance analysis to gain insight into the reasons for the child’s performance limitations (e.g., neuromuscular, sensory processing, visual perceptual). This analysis allows the therapist to refine the goals and to design intervention strategies likely to improve functional performance. Stewart (Chapter 7) and Richardson (Chapter 8) describe the use of standardized assessments in analyzing performance. Assessment of multiple performance areas is critical to understanding a functional problem and to developing a focused intervention likely to improve performance. Many of the chapters describe the evaluation process and identify valid tools that help to analyze a child’s performance and behavior.

Ecologic Assessment

Several chapters describe and advocate ecologic assessment—i.e., evaluation in the child’s natural environment. Ecological assessment allows the therapist to consider how the environment influences performance and to design interventions easily implemented in the child’s natural environment. By considering the child’s performance in the context of physical and social demands, ecologic assessment helps to determine the discrepancy between the child’s performance and expected performance (Figure 1-2). Stewart (Chapter 7) explains that an ecologic assessment considers cultural influences, resources, and value systems of the setting. Two examples of standardized ecologic assessments are the School Function Assessment22 and the Sensory Processing Measure.59,66 Both are comprehensive measures of children’s functioning in the context of school and/or home. Figure 1-3 shows an example of an activity observed to complete the School Function Assessment.

FIGURE 1-2 By evaluating the child at home, the therapist gathers information about how the family uses the child’s technology and how the child accesses home environments and participates in activities of daily living.

FIGURE 1-3 Through observation of a writing activity at school, the occupational therapist gains an understanding of the accommodations and supports needed as well as the child’s performance level.

The importance of ecologic assessment for youth preparing to transition into work and community environments is emphasized by Spencer (Chapter 27). To support adolescents preparing for employment, assessment must occur in the community and the worksite. Through in-depth task analysis and performance analysis, the therapist identifies the skills required for the job tasks and the discrepancy between the task requirements and the youth’s performance. If the team seeks to identify the student’s interests and abilities as they relate to future community living, an ecologic assessment would take place in the community and the home. Spencer explains that systematic and careful observation of the student’s performance during daily activities (e.g., home chores, food shopping, banking, using transportation, bill paying) enables therapists to target what skills need to be practiced, what tasks modified, and what environmental adaptations made. Ecologic approaches consider the characteristics of the individual and the physical, social, cultural, and temporal demands the individual faces (Spencer, Chapter 27).

Evaluating Context

Occupational therapists also evaluate the contexts in which the child learns, plays, and interacts. Evaluating performance in multiple contexts (e.g., home, school, daycare, other relevant community settings) allows the therapist to appreciate how different contexts affect the child’s performance and participation.

Contexts important to consider when evaluating children include physical, social, and cultural factors. The physical space available to the child can facilitate or constrain exploration and play. Family is the primary social context for the young child, and peers become important aspects of the social context at preschool and school ages. The occupational therapist evaluates physical and social contextual factors using the following questions:

• Does the environment allow physical access?

• Are materials to promote development available?

• Does the environment provide an optimal amount of supervision?

• Are a variety of spaces and sensory experiences available?

• Is the environment conducive to social interaction?

• Are opportunities for exploration, play, and learning available?

• Is positive adult support available and developmentally appropriate?

The occupational therapist evaluates how the environmental and activity demands facilitate or constrain the child’s performance. An understanding and appreciation of the family’s culture, lifestyle, parenting style, and values have profound influence on the child’s development and form a foundation for intervention planning.

Through comprehensive evaluation, the therapist analyzes the discrepancies between performance, expectations for performance, and activity demands. She or he identifies potential outcomes that fit the child and family’s story. By moving from assessment of participation to analysis of performance and contexts, the therapist gains a solid understanding of the strengths, concerns, and problems of the individuals involved (e.g., child, parent, or caregiver; family members; teachers). The occupational therapist also understands how to interact with the child to build a trusting and a positive relationship.

Effective Interventions

Much of this book describes interventions for children. Occupational therapists improve children’s performance and participation by (1) providing interventions to enhance performance, (2) adapting activities and modifying the environment, and (3) consulting, educating, and advocating. These intervention strategies complement each other and in best practice are applied together to support optimal growth and function in the child.

Providing Interventions to Enhance Performance

This section defines and illustrates the chapter themes that explain how the occupational therapist interacts with, challenges, and supports the child and develops interventions that promote and reinforce the child’s participation. The following elements appear to be core to the therapeutic process. The therapist designs and implements intervention activities with the child that:

1. Optimize the child’s active engagement

2. Provide a just right challenge

3. Establish a therapeutic relationship

4. Provide adequate and appropriate intensity and reinforcement

Optimize Child’s Engagement: Parham and Mailloux (Chapter 11) propose that active participation and tapping the child’s inner drive are key features of the sensory integration intervention. Engagement is essential because the child’s brain responds differently and learns more effectively when he or she is actively involved in a task rather than merely receiving passive stimulation. These authors cite the original work of Ayres, who theorized that children experience a greater degree of sensory integration when actively, rather than passively, participating in an activity (see Chapter 11).3

The child’s engagement in an activity or a social interaction is an essential component of a therapy session. This engagement funnels the child’s energy into the activity, helps him or her sustain full attention, and implies that the child has adopted a goal and purpose that fuels his performance in the activity. Engagement can be difficult to obtain when the child has an autism spectrum disorder. Spitzer suggests that a therapist can engage a child with autism by beginning with his or her immediate interest, even if it appears as meaningless (e.g., spinning a wheel, lining up toy letters, lying upside down on a ball).84 The therapist may begin with the child’s obsessive interest (i.e., trains, letters, or balls) and create a more playful, social interaction using these objects. By engaging in the child’s preferred activity, the therapist can foster and sustain social interaction, at the same time making the activity more playful and purposeful.

In Chapter 9, O’Brien and Williams explain that the child’s engagement in an activity is essential to its therapeutic value in promoting motor control. These authors recommend that the child select and help design the activity to increase his or her engagement in it. The therapist can engage an older child in a task by presenting a problem to be solved. Posing a dilemma in the child’s area of interest can help the child focus on the problem, adopt a potential solution as a goal, and stay engaged until the problem is solved. For example, the therapist can explain to a child with poor balance that the therapy room floor has become steamy hot and the child must jump from one stone (plastic disk) to another to avoid the heat. This same therapy floor may turn into ice, and the child has to skate across the floor on pieces of paper. Children learn and retain motor skills more from intrinsically problem-solving a motor action than from receiving external feedback during an action (such as hand-over-hand assistance).

Whole activities with multiple steps and a meaningful goal (versus repetition of activity components) elicit the child’s full engagement and participation. Repeating a single component (e.g., squeeze the Play-Doh or place pennies in a can) has minimal therapeutic value. Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) studies indicate that more areas of the brain are activated when individuals engage in meaningful whole tasks versus parts of the tasks (O’Brien & Williams, Chapter 9).48 By engaging in an activity with a meaningful goal (e.g., cooking or an art project), children use multiple systems and organize their performance around that goal. This is usually a functional organization that can generalize to other activities. For example, if a game requires that a preschool child attend to a peer, wait for his turn, and correctly place a game piece, the child is developing the joint attention that he or she needs to participate in circle time or a family meal.

Provide a Just Right Challenge: Maximal active involvement generally takes place when therapeutic activities are at just the right level of complexity, where the child not only feels comfortable and nonthreatened but also experiences some challenge that requires effort. An activity that is a child’s “just right” challenge has the following elements: the activity (1) matches the child’s developmental skills and interests, (2) provides a reasonable challenge to current performance level, (3) engages and motivates the child, and (4) can be mastered with the child’s focused effort.

Based on careful analysis of performance and behavior, the occupational therapist selects an activity that matches the child’s strengths and limitations across performance domains. The analysis allows the therapist to individualize the difficulty, the pace, and the supports needed for a child to accomplish a task. Generally, the therapist selects highly adaptable activities that can be modified to raise or lower the difficulty level based on the child’s performance. To promote change in the child, the activity must be challenging and create a degree of stress. Figure 1-4 provides an example of an activity challenging to a child with sensory integration problems. The stress is meant to elicit a higher level of response. The therapist’s and the child’s interactions are like a dance: The therapist poses a problem or challenge to the child, who is then motivated by that challenge and responds. The therapist facilitates or supports the action in order to prompt the child to respond at a higher level. The therapist then gives feedback regarding the action and presents another problem of greater or lesser difficulty, based on the success of the child’s response. Cognitive, sensory, motor, perceptual, or social aspects of the activity may be made easier or more difficult (Case Study 1-1). By precisely assessing the adequacy of the child’s response, the occupational therapist finds the just right challenge.

FIGURE 1-4 A climbing wall activity challenged this child’s motor planning, bilateral coordination, strength, and postural stability.

Parham and Mailloux (Chapter 11) explain that therapy sessions typically begin with activities that the child can engage in comfortably and competently and then move toward increasing challenges. They provide an example of a child with gravitational insecurity (i.e., fear of and aversion to being on unstable surfaces or heights with immature postural balance). Therapy activities begin close to the ground, and the therapist provides close physical support to help the child feel secure. Gradually, in subsequent sessions, the therapist designs activities that require the child to walk on unstable surfaces and to swing with his or her whole body suspended (Figure 1-5). These graded activities pose a just right level of challenge while respecting the child’s need to feel secure and in control. This gradual approach is key to maximizing the child’s active involvement in therapy.

FIGURE 1-5 Applying a sensory integration approach, the therapist gradually introduced the child with gravitational insecurity to unstable surfaces and higher levels of vestibular input.

Meyers, Stephens, and Tauber (Chapter 23) suggest that therapists design and employ play activities that engage and challenge the child across domains (for example, activities that are slightly higher than the child’s development level in motor, cognitive, and social domains). When a task challenges both cognitive and motor skills, the young child becomes fully engaged and the activity has high therapeutic potential for improving the child’s developmental level of performance.

Establish a Therapeutic Relationship: The occupational therapist establishes a relationship with the child that encourages and motivates. The therapist first establishes a relationship of trust (Figure 1-6).9,15,89 The therapist becomes invested in the child’s success and reinforces the importance of the child’s efforts. Although the therapist presents challenges and asks the child to take risks, the therapist also supports and facilitates the performance so that the child succeeds or feels okay when he or she fails. This trust enables the child to feel safe and willing to take risks. The occupational therapist shows interest in the child, makes efforts to enjoy his or her personality, and values his or her preferences and goals. The child’s unique traits and behaviors become the basis for designing activities that will engage the child and provide the just right challenge.

FIGURE 1-6 A hallway conversation helps to establish the therapist’s relationship with the child. (Courtesy of Jayne Shepherd and Sheri Michael.)

To establish a therapeutic relationship, therapists select an activity of interest that motivates the child and gives the child choices.36,84 Fostering a therapeutic relationship involves respecting the child’s emotions, conveying positive regard toward the child, attempting to connect with the child, and creating a climate of trust and emotional safety.65 The therapist encourages positive affect by attending to and imitating the child’s actions and communication attempts, waiting for the child’s response, establishing eye contact, using gentle touch, and making nonevaluative comments. By choosing activities that allow the child to feel important and by grading the activity to match the child’s abilities, the therapist gives the child the opportunity to achieve mastery and a sense of accomplishment. Generally, the intrinsic sense of mastery is a stronger reinforcement to the child than external rewards, such as verbal praise or other contingent reward systems. The occupational therapist vigilantly attends to the child’s performance during an activity to provide precise levels of support that enable the child to succeed. A child’s self-esteem and self-image are influenced by skill achievement and by success in mastering tasks.

The occupational therapist remains highly sensitive to the child’s emerging self-actualization and helps the team and family provide activities and environments that support the child’s sense of self as an efficacious person. Self-actualization, as defined by Fidler and Fidler,31 occurs through successful coping with problems in the everyday environment. It implies more than the ability to respond to others: self-actualization means that the child initiates play activities, investigates problems, and initiates social interactions. A child with a positive sense of self seeks experiences that are challenging, responds to play opportunities, masters developmentally appropriate tasks, and forms and sustains relationships with peers and adults. Vroman (Chapter 4) defines self-esteem, self–image, and self-worth and explains how teenagers’ self-concept influences health and activity. In Chapter 17, Loukas and Dunn discuss the importance of therapeutic relationships for fostering self-determination in adolescents with significant disabilities.

Research evidence suggests that interventions in which the therapist establishes a relationship with the child and emphasizes playful social interaction within the therapy session have positive effects on children’s development.38,97 Studies of the effectiveness of relationship-based interventions have found that they promote communication and play,38 social-emotional function,39,54 and learning.98 The practitioner’s therapeutic relationship with the child appears to be a consistent feature of efficacious interventions.14

Provide Adequate and Appropriate Intensity and Reinforcement: Research evidence cited throughout this book indicates that more intense intervention has greater positive effects on performance. One intervention, constraint-induced movement therapy (CIMT), has been shown to have strong positive effects (Exner, Chapter 10).25 This intervention uses a specific protocol with a specific population of children. In CIMT, the nonaffected hand and arm of children with hemiparesis cerebral palsy is casted, and the child practices specific skills with the affected hand and arm (Figure 1-7). CIMT also provides an intensive dosage of therapy. The “shaping” intervention is provided 6 hours a day for 21 days. The results are unequivocal that the child’s movement and function with the involved upper extremity improve.25,88

FIGURE 1-7 In constraint-induced movement therapy, the child’s less involved arm was casted, and she received intensive therapy to build skills in the involved arm and hand.

Although this dosage of therapy is not typical and may not be practical in most situations, these research findings suggest that intensive services have clear benefit. Schertz and Gordon conclude that intensive interventions that involve repeated practice and progressive challenge can produce positive changes in functional performance.79 O’Brien and Williams (Chapter 9) explain the importance of repeated practice in skill attainment. They note that children learn new skills with frequent practice and various types of practice. Motor learning studies have shown that intense (blocked) practice is helpful when first learning a new skill but that the child also needs variable and random practice to generalize and transfer the newly learned skill to a variety of situations.

Although the research evidence demonstrates more positive effects with intensive intervention, for practical reasons the field has not yet embraced this model for providing therapy services. Constrained by resources and systems limited in capacity to deliver intensive therapy, most occupational therapy episodes have limited intensity and duration. The research evidence has created discussion in the field about what model for service delivery is optimal and how children can access the most efficacious interventions.

Research has also demonstrated that interventions in which the child is rewarded for performing well have positive effects.87,97 Based on a behavioral model, most occupational therapy interventions include reinforcement of the child’s efforts. This reinforcement can range from hugs and praises to more tangible objects, such as a prize or piece of candy. Occupational therapists often embed a natural reinforcement within the activity. For example, the therapist designs a session in which a group of four 12-year-olds with Asperger’s syndrome bake cookies. The natural reinforcement includes eating cookies and enjoying socialization with others during the activity. Positive reinforcement includes both intrinsic (e.g., feeling competent or sense of success) and extrinsic (e.g., adult praise or a treat) feedback. O’Brien and Williams (Chapter 9) explain that feedback can be most effective when it is given on a variable schedule, with the goal that feedback is faded as the skill is mastered. External feedback appears to be effective when it provides specific information to the child about performance and when it immediately follows performance.82 In summary, research evidence supports that children’s performance improves with intense practice of emerging skills and with a system of rewards for higher level performance.

Occupational therapy interventions are not always focused on the child’s performance; at times, the emphasis is on implementing adapted methods or applying assistive technology to increase the child’s participation despite performance problems. The following sections explain how occupational therapists use adaptation, assistive technology, and environmental modification to improve a child’s participation in home, school, and community activities.

Adapting Activities and Modifying the Environment

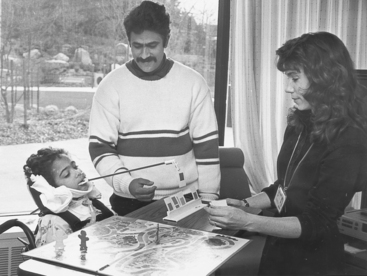

Interventions Using Assistive Technology: Occupational therapists often help children with disabilities participate by adapting activities and applying assistive technology (Figure 1-8). Adapted techniques for play activities may include switch toys, battery-powered toys, enlarged handles on puzzle pieces, or magnetic pieces that can easily fit together. In activities of daily living, adapted techniques can be used to increase independence and reduce caregiver assistance in eating, dressing, or bathing. In Chapter 16, Shepherd offers many examples of adapted techniques to increase a child’s independence in self-care and activities of daily living.

FIGURE 1-8 The occupational therapist designed a mouth stick and game board setup so that the child could play the game with his father.

Technology is pervasive throughout society, and its increasing versatility makes it easily adaptable to an individual child’s needs. Low-technology solutions are often applied to increase the child’s participation in play or to increase a child’s independence in self-care. Examples include built-up handles on utensils, weighted cups, elastic shoelaces, and electric toothbrushes. High-technology solutions are often used to increase mobility or functional communication. Examples are power wheelchairs, augmentative communication devices, and computers.

High technology is becoming increasingly available and typically involves computer processing and switch or keyboard access (e.g., augmentative communication devices) (see Chapter 20). Occupational therapists frequently support the use of assistive technology by identifying the most appropriate device or system and features of the system. They often help families obtain funding to purchase the device, set up or program the system, train others to use it, and monitor its use. They also make themselves available to problem-solve the inevitable technology issues that arise.

The role of assistive technology with children is not simply to compensate for a missing or delayed function; it is also used to promote development in targeted performance areas. Research has demonstrated that increased mobility with the use of a power wheelchair increases social and perceptual skills (see Chapter 21).9,10,13,63 The use of an augmentative communication device can enhance language and social skills and may prevent behavioral problems common in children who have limited means of communicating. Therefore, the occupational therapist selects assistive technology not only to enable the child to participate more fully in functional or social activities but also to enhance the development of skills related to a specific occupational area. For example, to develop preliteracy skills a child who has a physical disability with severe motor impairments can access a computer program that simulates reading a book; to promote computer skills the child can use an expanded keyboard (Figure 1-9). The computer programs used in schools to promote literacy, writing, and math skills with all children are particularly beneficial to children who have learning and physical disabilities. Because schools have invested in universal design and appropriate accommodations for all learners, many students with disabilities can access computer programs that promote their literacy and writing skills. In Chapter 20, Schoonover, Argabrite Grove, and Swinth describe currently available technologies designed to promote children’s functional performance.

Assistive technology solutions continually change as devices become more advanced and more versatile. Although a therapist can extensively train a student to use power mobility, an augmentative communication device, or an adapted computer, the child’s skills with the technology will not generalize into everyday routines unless parents, teachers, and aides are sufficiently comfortable with and knowledgeable about the technology. Because it is important that those adults closest to the child be able to implement the technology and troubleshoot when necessary, the occupational therapist must educate them extensively about how to apply the technology—and remain available to problem-solve the issues that inevitably arise. Often, it is necessary to talk through and model each step in the use of the technology. Strategies for integrating the technology into a classroom or home environment (e.g., discussing the ways the device can be used throughout the day) help to achieve the greatest benefit. All team members need to update their skills routinely so that they have a working knowledge of emerging technology.

One trend observed in school systems is that the occupational therapist often serves as an assistive technology consultant or becomes a member of a district-wide assistive technology team. Assistive technology teams have been formed to provide support and expertise to school staff members in applying assistive technology with students. These teams make recommendations to administrators on equipment to order, train students to use computers and devices, troubleshoot technology failures, determine technology needs, and provide ongoing education to staff and families.

Technologic solutions are described throughout this text and are the focus of Chapters 16, 20, and 21. These chapters offer the following themes on the use of assistive technology:

• Assistive technology should be selected according to the child’s individual abilities (intrinsic variables), expected or desired activities, and environmental supports and constraints (extrinsic variables).

• Techniques and technology should be adaptable and flexible, so that devices can be used across environments and over time as the child develops.

• Technology should be selected with a future goal in mind and a vision of how the individual and environment will change.

• The strategy and technology should be selected in consultation with caregivers, teachers, and other professionals and all adults who support its use.

• Extensive training and follow-up should accompany the use of assistive technology.

In summary, assistive technologies have significantly improved the quality of life for persons with disabilities. Computers, power mobility, augmentative communication devices, and environmental control units make it possible for children to participate in roles previously closed to them.

In addition to assistive technology designed specifically for children with impairments, children with disabilities also have more access to technology through universal access. The concept of universal access, now widespread, refers to the movement to develop devices and design environments that are accessible to everyone. When schools invest in universal access for their learning technology, all students can access any or most of the school’s computers, and adaptations for visual, hearing, motor, or cognitive impairment can be made on all or most of the school’s computers. Universal access means that the system platforms can support software with accessibility options and that a range of keyboards, “mice” (tracking devices), and switches are available for alternative access.

Environmental Modification: To succeed in a specific setting, a child with disabilities often benefits from modifications to the environment. Goals include not only enhancing a child’s participation but also increasing safety (e.g., reducing barriers on the playground) and improving comfort (e.g., improving ease of wheelchair use by reducing the incline of the ramp). Children with physical disabilities may require specific environmental adaptations to increase accessibility or safety. For example, although a school’s bathroom may be accessible to a child in a wheelchair, the therapist may recommend the installation of a handlebar beside the toilet so that the child can safely perform a standing pivot transfer. Desks and table heights may need to be adjusted for a child in a wheelchair.

Environmental adaptations, such as modifying a classroom or a home space to accommodate a specific child with a disability, can be accomplished only through consultation with the adults who manage the environment. High levels of collaboration are needed to create optimal environments for the child to attend and learn at school and at home. Environmental modifications often affect everyone in that space, so they must be appropriate for all children in that environment. The therapist articulates the rationale for the modification and negotiates the changes to be made by considering what is most appropriate for all, including the teacher and other students. Through discussion, the occupational therapist and teacher reach agreement as to what the problems are. With consensus regarding the problems and desired outcomes, often the needed environmental modification logically follows. It is essential that the therapist follow through by evaluating the impact of the modification on the targeted child and others. The Americans with Disabilities Act provides guidelines for improving school and community facility accessibility.

Often the role of the occupational therapist is to recommend adaptations to the sensory environment that accommodate children with sensory processing problems.26 Preschool and elementary school classrooms usually have high levels of auditory and visual input. Classrooms with high noise levels may be overwhelmingly disorganizing to a child who is hypersensitive to auditory stimulation. Young children who need deep pressure or quiet times during the day may need a beanbag chair placed in a pup tent in the corner of the room. The therapist may suggest that a preschool teacher implement a quiet time with lights off to provide a period to calm children. Meyers, Stephens, and Tauber (Chapter 23), Watling (Chapter 14), and Parham and Mailloux (Chapter 11) describe contextual modifications to accommodate a child who has sensory processing problems.

Other environmental modifications can improve children’s arousal and attention. Sitting on movable surfaces (e.g., liquid-filled cushions) can improve a child’s posture and attention to classroom instruction.80 The intent of recommendations regarding the classroom environment is often to maintain a child’s arousal and level of alertness without overstimulating or distracting him or her. Modifications should enhance the child’s performance, make life easier for the parent or teachers, and have a neutral or positive effect on siblings, peers, and others in the environment. Due to the dynamic nature of the child and the environment, adaptations to the environment may require ongoing assessment to evaluate the goodness of fit between the child and the modified environment and determine when adjustments need to be made.

Consulting, Educating, and Advocating

Consultation Services: Services on behalf of children include consultation with and education of teachers, parents, assistants, childcare providers, and any adults who spend a significant amount of time with the child. Through these models of service delivery, the occupational therapist helps to develop solutions that fit into the child’s natural environment and promotes the child’s transfer of new skills into a variety of environments.

In Chapter 11, Parham and Mailloux explain that a first step in consultation is “demystifying” the child’s disorder. By explaining the child’s behaviors as a sensory processing problem to teachers and parents, therapists foster a better understanding of the reasons for the child’s behavior (e.g., constant bouncing in a chair or chewing on a pencil), which gives adults new tools for helping the child change behavior. Reframing the problem for caregivers and teachers enables them to identify new and different solutions to the problem and often makes them more open to the therapist’s intervention recommendations.8 For a situation in which a highly specific, technical activity is needed to elicit a targeted response in the child, teaching others may not be appropriate, and a less complex and less risky strategy should be transferred to the caregivers to implement. To routinely implement a strategy recommended by the therapist, teachers and caregivers need to feel confident that they can apply it successfully.

A major role for school-based occupational therapists is to support teachers in providing optimal instruction to students and helping children succeed in school.35 Therapists accomplish this role by promoting the teacher’s understanding of the physiologic and health-related issues that affect the child’s behavior and helping teachers apply strategies to promote the child’s school-related performance. Therapists also support teachers in adapting instructional activities that enable the child’s participation, and collaborate with teachers to collect data on the child’s performance. This focus suggests that, in the role of consultant, the therapist sees the teacher’s needs as a priority and focuses on supporting his or her effectiveness in the classroom.42 Consultation is most likely to be effective when therapists understand the curriculum, academic expectations, and the classroom environment.

Effective consultation also requires that the teacher or caregiver be able to assimilate and adapt the strategies offered by the therapist and make them work in the classroom or the home. The therapist asks the teacher how he or she learns best and accommodates that learning style.42 Teachers need to be comfortable with suggested interventions, and therapists should offer strategies that fit easily in the classroom routine. The therapist and teacher can work together to determine what interventions will benefit the child and be least intrusive to the other students.

Education and Advocacy: Therapists also function as advocates, educating role players about the need to improve accessibility to recreational, school, or community activities; modify curriculum materials; develop educational materials; and improve attitudes toward disabilities. By participating in curriculum revision or course material selection, therapists can help establish a curriculum with sufficient flexibility to meet the needs of children with disabilities. Often a system problem that negatively affects one child is problematic to others as well. The occupational therapist needs to recognize which system problems can be changed and how these changes can be encouraged. For example, if a child has difficulty reading and writing in the morning, he or she may benefit from physical activity before attempting to focus on deskwork. The occupational therapist cannot change the daily schedule and move recess or physical education to the beginning of the day, but she or he may convince the teacher to begin the first period of the day with warm-up activities. The therapist can advocate for a simplified, continuous stroke handwriting curriculum, which can benefit children with motor-planning problems but also benefits all children beginning to write. Accessible playgrounds can be safer and enable all children, regardless of skill level, to access the equipment.

Ecologic models of child development recognize the powerful influence of home, school, and community environments on child and youth outcomes (Spencer, Chapter 27).51 Occupational therapists should advocate for environments that are both physically accessible and welcoming to children with disabilities. With an extensive background on what elements create a supportive environment, therapists can help to design physical and social environments that facilitate every child’s participation. To change the system on behalf of all children, including those with disabilities, requires communication with stakeholders or persons who are invested in the change. The occupational therapist needs to confidently share the rationale for change, appreciate the views of others invested in the system, and change and negotiate when needed.

A system change is most accepted when the benefits appear high and the costs are low. Can all children benefit? Which children are affected? If administrators and teachers in a childcare center are reluctant to enroll an infant with a disability, the occupational therapist can advocate for accepting the child by explaining specifically the care that the child would need, the resources available, behaviors and issues to expect, and the benefits to other families.

Convincing a school to build an accessible playground is one example of how a focused education effort can create system change. Occupational therapists are frequently involved in designing playgrounds that are accessible to all and promote the development of sensory motor skills. Another example is helping school administrators select computer programs that are accessible to children with disabilities (see Chapter 19). The occupational therapist can serve on the school committee that selects computer software for the curriculum and advocate for software that is easily adaptable for children with physical or sensory disabilities. A third example is helping administrators and teachers select a handwriting curriculum to be used by regular and special education students. The occupational therapist may advocate for a curriculum that emphasizes prewriting skills or one that takes a multisensory approach to teaching handwriting (see Chapter 18). The occupational therapist may also advocate for adding sensory-motor-perceptual activities to an early childhood curriculum. In Chapter 24, Bazyk and Case-Smith describe the role of occupational therapists in promoting positive behavioral supports to improve school mental health outcomes. These examples of system change suggest that occupational therapists become involved in helping educational systems, as well as medical and community systems, enable participation of all children, prevent disability among children at risk, and promote healthy environments where all children can learn and grow.

Occupational Therapy Services That Support Inclusion

Legal mandates and best practice guidelines require that services to children with disabilities be provided in environments with children who do not have disabilities. The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act requires that services to infants and toddlers be provided in “natural environments” and that services to preschool and school-aged children be provided in the “least restrictive environment.” The infant’s natural environment is most often his or her home, but it may include a childcare center or a care provider’s home. The family defines the child’s natural environment. This requirement shifts when the child reaches school age, not in its intent but with recognition that community schools and regular education classrooms are the most natural and least restrictive environments for services to children with disabilities. Inclusion in natural environments or regular education classrooms succeeds only when specific supports and accommodations are provided to children with disabilities. Occupational therapists are often important team members in making inclusion successful for children with disabilities. (This concept is further discussed in Chapters 23 and 24.)

Early Intervention Services in the Child’s Natural Environment

The Division of Early Childhood of the Council for Exceptional Children supports the philosophy of inclusion in natural environments with the following statement: “Inclusion, as a value, supports the right of all children, regardless of their diverse abilities, to participate actively in natural settings within their communities. A natural setting is one in which the child would spend time if he or she had not had a disability” (p. 4).23

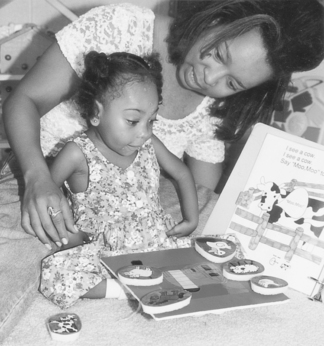

As explained by Meyers, Stephens, and Tauber (Chapter 23), the philosophy of inclusion extends beyond physical inclusion to mean social and emotional inclusion of the child and family.18,92 The implications for occupational therapists are that they provide opportunities for expanded and enriched natural learning with typically developing peers. Natural environments can be any setting that is part of the child and family’s everyday routine where incidental learning experiences occur.27 Therefore, intervention and consultation services can occur in a childcare center, at a grandmother’s house, or in another place that is part of a family’s routine. Social, play, and self-care learning opportunities in these environments are plentiful. Figure 1-10 shows an example of a child’s natural environment in which the therapist could intervene.

FIGURE 1-10 The occupational therapist coaches the child’s mother to facilitate the child’s perceptual motor skills.

When occupational therapy occurs in a natural environment such as the home, the intervention activities are embedded in naturally occurring interactions and situations. In incidental learning opportunities, the therapist challenges the child to try a slightly different approach or to practice an emerging skill during typical activities. The therapist follows the young child’s lead and uses natural consequences, (e.g., a smile or frown, a pat or tickle) to motivate learning. Research has shown that intervention strategies that occur in real-life settings produce greater developmental change than those that take place in more contrived, clinic-based settings.12,27 In addition, generalization of skills and behaviors occurs more readily when the intervention setting is the same as the child’s natural environment(s).44,45

Early intervention therapy services in natural environments require the occupational therapist to be creative, flexible, and spontaneous. The therapist must think through many alternative ways to reach the established goals and then adapt those strategies to whatever situation presents.41 Recognizing and accepting the family’s uniqueness in cultural and child-rearing practices, therapists are able to facilitate the child’s ability to generalize new skills to a variety of settings.

Inclusive Services in Schools

In the school-based services, inclusion refers to integration of the child with disabilities into the regular classroom with support to accomplish the regular curriculum. See Box 1-1 for a list of the desired outcomes of inclusive school environments. In schools with well-designed inclusion, every student’s competence in diversity and tolerance for differences increases. Related service practitioners provide interventions in multiple environments (e.g., within the classroom, on the playground, in the cafeteria, on and off the school bus), emphasizing nonintrusive methods. The therapist’s presence in the classroom benefits the instructional staff members, who observe the occupational therapy intervention. As explained by Bazyk and colleagues (Chapter 24), integrated therapy ensures that the therapist’s focus has high relevance to the performance expected within the classroom. It also increases the likelihood that adaptations and therapeutic techniques will be carried over into classroom activities,100 and it ensures that the occupational therapist’s goals and activities link to the curriculum and the classroom priorities (Figure 1-11).

Flexible Service Delivery Models

Children with disabilities benefit when therapy is provided as both direct and consultative services. Even when consultation is the primary service delivery model for a particular child, frequent one-on-one interaction between the therapist and the child is needed to inform it. Because children constantly change and the environment is dynamic, monitoring the child’s performance through opportunities for direct interaction is necessary. With opportunities to directly interact with the child and experience the classroom environment, the occupational therapist can best support the child’s participation and guide the support of other adults.

In a fluid service delivery model, therapy services increase when naturally occurring events create a need—for example, when the child obtains a new adapted device, has surgery or casting, or even when a new baby brother creates added stress for a family. Similarly, therapy services should be reduced when the child has learned new skills that primarily need to be repeated and practiced in his daily routine or the child has reached a plateau on her therapy-related goals.

Recently developed models for school-based service delivery offer the possibility for greater flexibility.15 Block scheduling68 and the 3-in-1 model2 are two examples of flexible scheduling that allow therapists to move fluidly between direct and consultative services. In block scheduling, therapists spend 2 to 3 hours in the early childhood classroom working with the children with special needs one on one and in small groups, while supporting the teaching staff (Meyers, Stephens, & Tauber, Chapter 23).64 Block scheduling allows therapists to learn about the classroom, develop relationships with the teachers, and understand the curriculum so that they can design interventions that easily integrate into the classroom. By being present in the classroom for an entire morning or afternoon, the therapist can find natural learning opportunities to work on a specific child’s goals. Using the child’s self-selected play activity, the therapist employs strategies that are meaningful to the child, fit into his or her preferred activities, and are likely to be practiced. During the blocked time, the therapist can run small groups (using a coteaching role21), coach the teacher and assistants,76 evaluate the child’s performance, and monitor the child’s participation in classroom activities.

Another approach that allows more flexible services delivery is the 3-and-1 model.2 In this model, the therapist dedicates one week a month to consultation and collaboration with the teacher, providing services on behalf of the child rather than directly to the child. When the Individualized Education Program (IEP) document states that a 3-and-1 therapy model will be used to support the child’s IEP goals, the parents, teacher, and administrators are informed that one quarter of the therapist’s time and effort for that child is dedicated to planning, collaborating, and consulting for him or her. Stating that a 3-and-1 model will be used removes the expectation that the therapist will provide one-on-one services for a set number of minutes each week. It facilitates meeting and planning time and establishes that consultation time is as important to the child’s progress as one-on-one services. For example, the week of indirect service can also be spent creating new materials and adapted devices for the child (e.g., an Intellikeys overlay to use with the curricular theme of the month). Therapists can write “social stories” for the child or program new vocabulary into the child’s augmentative communication device.37

Cross-Cultural Competence

Cross-cultural competence can be defined as “the ability to think, feel, and act in ways that acknowledge, respect, and build upon ethnic, [socio]cultural, and linguistic diversity” (p. 50).52 Cultural competence in health care refers to behaviors and attitudes that enable an individual to function effectively with culturally diverse clients.74 Occupational therapists with cultural competence can respond optimally to all children in all sociocultural contexts. Chan identified its three essential elements: self-awareness, knowledge of information specific to each culture, and interaction skills sensitive to cultural differences.19 The following factors, described in this section, support the importance of cross-cultural competence to occupational therapists:

• Cultural diversity of the United States continues to increase.

• A child’s development of occupations is embedded in the cultural practices of his family and community.

Cultural Diversity in the United States

The diversity and heterogeneity of American families continue to increase each year. In 2006, the number of immigrants totaled 37.5 million. A total of 1,266,264 immigrants became legal permanent residents of the United States, more than double the number in 1987 (601,516). Most of the immigrants were from Mexico (173,753); however, a substantial number were from China and India.56 The Census Bureau projects that, by 2050, one quarter of the population will be of Hispanic descent.56,93

In 2008, the United States was home to 74 million children. Of these, 15.4 million (~21%) were Hispanic and 10.8 million (~15%) were African American.20 Children in minority groups are increasing in number at a much faster rate than increases in the general population. Diversity of ethnicity and race can be viewed as a risk or as a resource to child development.34 Low birthrate, preterm delivery, and infant mortality are higher in African American families, suggesting that these families frequently need early childhood intervention programs. Race can also be a resource; for example, African American families are well supported by their communities and focused on their children (Figure 1-12). Parents often perceive discipline and politeness as positive attributes and instill these in their children.99 Occupational therapists who work with African American and Hispanic families find many positive attributes in their family interactions and parenting styles.

Poverty has a pervasive effect on children’s developmental and health outcomes.20 Despite overall prosperity in the United States, a significant number of children and families live in poverty. In 2008, the number of poor children was over 13 million (18%), and the number of children in extreme poverty was almost 6 million (8%). Families in poverty often have great need for, yet limited access to, health care and educational services. Many families who are served by early intervention and special education systems are of low socioeconomic status. When families lack resources (e.g., transportation, food, shelter), their priorities and concerns orient to these basic needs. Responsive therapists provide resources to assist with these basic needs, making appropriate referrals to community agencies. They also demonstrate understanding of the family’s priorities, which may not include their children’s occupational performance goals.

Influence of Cultural Practices on a Child’s Development of Occupations

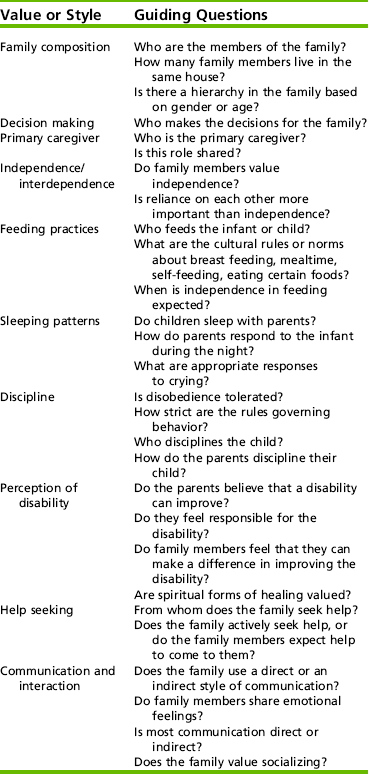

To impact a child’s occupational development, it is critical for the therapist to understand how cultural practices influence skill development. Table 1-3 lists the cultural values that may influence the child’s development of occupations. Goals for independence may not be appropriate at certain ages for children of certain cultures. For example, Middle Eastern families often do not emphasize early independence in self-care; therefore, skills such as self-feeding may not be a family priority until ages well beyond the normative expectations.81 In Hispanic cultures, holding and cuddling are highly valued, even in older children.101 Mothers hold and carry their preschool children. Recommending a wheelchair for a young child may be unacceptable to families who value close physical contact and holding.

TABLE 1-3

Cultural Values and Styles That Influence Children’s Development of Occupations

Adapted from Wayman, K. I., Lynch, E. W., & Hanson, M. J. (1990). Home-based early childhood services: Cultural sensitivity in a family systems approach. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 10, 65-66.

In some cultures (e.g., Polynesian), parents delegate childcare responsibilities to older siblings. Therefore, in established families, siblings care for the infants. Young children in Polynesian cultures tend to rely on their older siblings rather than their parents for structure, assistance, and support. Being responsible for a younger sibling helps the older sibling mature quickly by learning responsibility and problem solving.72 Sibling care may present as a problem when the young child has a disability and needs additional or prolonged care. The literature is replete with examples of the influence of culture on children’s occupations.24,47,72,73 The occupational therapist’s appreciation of the influence of culture on children’s occupations facilitates the development of appropriate priorities and the use of strategies that are congruent with the family’s values and lifestyle.

Because the focus of occupational therapy is to enhance a child’s ability to participate in his or her natural environment and everyday routines, the therapist must appreciate, value, and understand those environments and routines. Recommendations that run counter to a family’s cultural values probably will not be implemented by family members and may be harmful to the professional–family relationships. The home environment and the family members’ interactions help to reveal their cultural values. By asking open-ended questions, therapists can elicit information about the family’s routines, rituals, and traditions to provide an understanding of the cultural context. The culturally competent therapist demonstrates an interest in understanding the family’s culture, an acceptance of diversity, and a willingness to participate in traditions or cultural patterns of the family. In home-based services, cultural competence may mean removing shoes at the home’s entryway, accepting foods when offered, scheduling therapy sessions around holidays, and accommodating language differences. In center-based services, cultural sensitivity remains important, although a family’s cultural values may be more difficult to ascertain outside the home. A culturally competent therapist inquires about family routines, cultural practices, traditions, and priorities; demonstrates a willingness to accommodate to these cultural values; and integrates her or his intervention recommendations into the family’s cultural practices.

The family’s cultural background has a multitude of implications for evaluation and intervention. Cultural values that are important to the occupational therapy perspective include how the family (1) values independent versus interdependent performance; (2) has a sense of time and future versus past orientation; (3) is forward thinking versus lives for the moment; (4) makes decisions that influence family members; (5) defines health, wellness, disability, and illness; and (6) practices customs related to dress, food, traditions, and religion.53 Often these values vary by cultural group; they also vary in individuals within a cultural group, depending on level of acculturation—that is, the degree to which a family has assimilated into the dominant culture.34

Scientific Reasoning and Evidence-Based Practice

With the goal of providing efficacious interventions, occupational therapists and other health care professionals seek and apply practices that have research evidence of effectiveness. In evidence-based practice, occupational therapists emphasize using research evidence to make decisions about interventions. Sackett, Rosenberg, Muir Gray, Haynes, and Richardson defined evidence-based medicine as “the conscientious, explicit, and judicious use of current best evidence in making decisions about the care of individual patients” (p. 71).77 Therefore, evidence-based practice does not mean that intervention is based solely on research findings. However, it does mean that occupational therapists search for and apply the research evidence, along with their own experiences and family priorities, when making intervention decisions.

The body of research literature supporting occupational therapy with children remains limited when compared with other disciplines (e.g., psychology); however, often research studies and clinical trials in other disciplines have relevance to occupational therapy practice. Research evidence is readily available and accessible through Internet sources. A list of links to health care research databases can be found on the Evolve website. The steps in applying evidence-based practice are listed in Box 1-2.

Using evidence is part of the occupational therapist’s scientific reasoning. In scientific reasoning,78 the occupational therapist uses research evidence, science-based knowledge about the diagnosis, and past experience in all steps of the assessment and intervention process. For example, in the case of Rebecca, a 5-year-old with autism, the occupational therapist noted that developmental play-based approaches that incorporate peers have evidence for moderate treatment effects,49,50 and that social interactive strategies46 have been found to be effective. Because Rebecca attends a preschool in which application of these interventions is supported by the team, the occupational therapist decided to use a developmental play-based, interactive approach.

In another example, Aaron, who has arthrogryposis, has limited upper extremity range of motion and difficulty holding utensils or opening packages. He is unable to carry his books during school transitions. Armed with research about arthrogryposis demonstrating that range of motion and strength do not significantly improve over time,85 the therapist selects a compensatory/adaptation approach to increase Aaron’s independence in activities of daily living. In the case of Claire, who has a diagnosis of developmental coordination disorder and poor handwriting, the occupational therapist accessed research by Sullivan, Kantuk, and Burtner.87 Based on this evidence and her past success in using motor learning strategies with children with developmental coordination disorder, the therapist selected a motor learning approach to increase Claire’s handwriting performance. The therapist reasoned that Claire would need 100% feedback about her performance until new skills were learned.87 Because the therapist found making holiday cards to be engaging for other girls Claire’s age, she selected this activity to practice and reinforce correct letter formation.

In searching for research to inform a clinical decision, the occupational therapist weighs the strength or importance of each study. Studies that provide the most important research evidence are meta-analyses or systematic reviews of clinical trials. The findings of these studies generally have good applicability to practice because they combine the findings of studies that have met a rigorous standard established by the authors. Findings from a rigorous randomized clinical trial also provide strong evidence for practice, followed by results from studies using quasi-experimental designs. Cohort studies and descriptive designs can provide information relevant to clinical decision making; however, their findings are not as strong and should be applied with caution. Outcome research can help practitioners establish benchmarks or standards for performance and client programs; however, descriptive outcome studies do not provide strong evidence for the effectiveness of a specific intervention. The parts summarized next describe some of the evidence for specific occupational therapy interventions or models of practice used in occupational therapy. Examples of interventions and models that have growing evidence of positive effects on children and families are presented.

Sensory Integration

The original studies that compared sensory integration intervention with no treatment3,4 demonstrated significant positive effects. These studies used samples of children with learning disabilities and compared sensory integration intervention with a control group. Although the effect sizes in Ayres’ original studies were high, the sample sizes were small.

Recent studies have found that the effects of intervention using a sensory integration approach are equivalent to the effects of alternative treatment approaches. Polatajko, Kaplan, and Wilson analyzed seven randomized clinical trials of sensory integration treatment that used two or more groups and included a comparison or control group.67 All studies were of children with learning disabilities between the ages of 4.8 and 13 years. The outcome variables in seven clinical trials did not provide any statistical evidence that sensory integration intervention improved academic performance. Several of the studies found that sensory and motor performance improved with sensory integration intervention. Most of the findings for children who received sensory integration intervention were similar to the findings for the children who received a perceptual motor intervention. A limitation cited by Polatajko et al. was that sensory integration intervention in a research context is quite different from sensory integration intervention in a clinic, where therapists can individualize each session to the needs of the child.67

A meta-analysis of sensory integration intervention by Vargas and Camilli showed small treatment effects,96 substantiating the earlier findings of Polatajko et al.67 Using a criterion-based selection process, Vargas and Camilli found 14 studies of sensory integration compared with no intervention and 11 of sensory integration compared with an alternative intervention (usually perceptual motor activities).96 Effect sizes were calculated and weighted for sample size. For comparisons of sensory integration with no treatment, the average effect size was .29, which is a low effect size. When sensory integration is compared with an alternative treatment, the effect size was .09, which means that the effects of sensory integration were not significantly different from those of other treatments. The authors reported that the average effect size for earlier studies (before 1982) was higher (.60) than the average effect size for studies after 1982 (.03). The skill areas that improved were psychoeducational and motor performance areas. Although the effects of sensory integration appear to be small, findings of significant improvement in motor performance following sensory integration intervention are consistent.

Recent studies of sensory integration intervention have shown positive effects. In a randomized clinical trial, Miller, Coll, and Schoen examined the effects of occupational therapy using a sensory integration approach on children’s attention, cognitive/social performance, and sensory processing and behavior.57 Children with sensory modulation disorders and co-occurring diagnoses such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and learning disabilities were randomized into three groups, occupational therapy (n=7), activity protocol (n=10), and no treatment (n=7). Children in the occupational therapy group received 10 weeks of two-a-day sensory integration intervention sessions using the protocol developed by these authors.58 Following the 10-week intervention, the children who received occupational therapy sensory integration made gains greater than those in the other two groups in intervention goals (using Goal Attainment Scaling) and on the Cognitive/Social composite of the Leiter International Performance Scale. The occupational therapy group also made gains in sensory processing and child behavior, but these were not statistically significant when compared with the other two groups. It is probable that the gains in sensory processing behaviors would have been significant if a larger sample size had been used. Although this trial provides evidence for sensory integration intervention effects, the strength of the findings is limited by the small sample size.

An important step in enhancing the rigor of sensory integration trials is the development of a fidelity measure65 and a manual of procedures for sensory integration intervention.57,58 Use of standardized intervention protocols will improve the fidelity of sensory integration intervention when administered in future trials and will improve both internal and external validity of the findings. Parham and Mailloux (Chapter 11) further discuss fidelity issues in sensory integration intervention trials.

Sensory Modalities

Application of sensory modalities has also been studied, generally in small samples and with positive results. These studies investigate the application of a specific sensory modality to achieve specific behavioral/performance outcomes in a group of children with the same diagnosis or similar problems. The efficacy of using touch pressure to gain behavioral changes in children with autism or ADHD has been researched.28,30,94 Edelson and his colleagues investigated the efficacy of the Hug Machine, a device that provides touch pressure through the sides of the body. Using a sample of children with autism, participants who received the Hug Machine treatment twice a week were compared with a control group. The participants who used the Hug Machine exhibited a significant reduction in tension and a slight change in anxiety. Physiologic measures were not significantly different between groups.

Two studies have examined the effect of pressure through wearing a weighted vest. Fertel-Daly and colleagues investigated the effects of a weighted vest on five preschool children with pervasive developmental disorders.30 Using an ABA single-subject design, vests were worn for 2 hours per day, 3 days a week, for 5 weeks, with baseline (wearing no vest) data collected before and after the intervention. Attention, number of distractions, and duration of self-stimulation behaviors were measured. All participants demonstrated increased attention and decreased distractibility, and four of five showed decreased self-stimulation behaviors. VandenBerg also examined the effects of a weighted vest on four children diagnosed with ADHD.94 The children demonstrated greater on-task behaviors when wearing the vests. The summary of the studies using small samples found that touch pressure and deep pressure, applied intermittently, can decrease tension and anxiety, improve attention, and increase on-task behavior.

Another study of sensory modalities examined the effects from children sitting on therapy balls on in-seat behavior and legible word productivity.80 Occupational therapists sometimes recommend that students sit on therapy balls in the classroom to give them additional vestibular and proprioceptive input while sitting. The children can bounce to stay attentive and alert and receive additional vestibular/proprioceptive feedback when they shift their weight through the ball’s movement. Using a multiple-baseline single-subject design, all participants (n=3) improved in in-seat behavior and legible word productivity.80 The balls seemed to help in sensory modulation with the participants, and they represent a nonintrusive method to promote academic-related outcomes, staying in one’s seat, and legible word productivity.

Randomized clinical trials of touch-based interventions, such as massage, have shown positive effects on attention and behavior. In two randomized clinical trials, Field and colleagues completed two trials with children with autism.29,32 In each the children were massaged (circular application of deep touch on trunk and extremities 1 to 2 times per day) by either parents or therapists. The children who received the month-long treatment demonstrated decreased aversion to touch, off task behaviors, stereotypical behaviors, and impulsivity. Interventions that involve intensive tactile input applied in systematic ways may reduce impulsive, hyperactive, or nonpurposeful behaviors.